- 1Facultad de Economia, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, Mexico

- 2Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades “Alfonso Vélez Pliego”, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, Mexico

This study seeks to contribute to the thesis that China is directing its efforts toward the construction of a set of institutions that are presented as an alternative interstate subsystem to the one that emerged in the second postwar period. In this research, we made progress in locating the main elements from which we prefigure one of the features of that project. This is the strategy that, based on the cooperation scheme implemented by China through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI)1 and the Global Security Initiative (GSI),2 manifests itself in a kind of “early emulation” of the North American hegemonic strategy of the second postwar period. “Emulation” of the United States (US) is synthesized in a double process: first, in the way in which China is currently articulating an institutional framework under the intensification of the present systemic chaos, that is, in a previous or “early” moment with respect to that in which we could consider the clear rise of a new hegemonic power. This framework operates under the logic of a political dialog that allows trade agreements and promotes a development strategy based on structural change. Second, in a similar way to the multilateral consensus that underpinned the US project based on the promotion of “development” from the north to the south and with a fundamental role for cooperation and aid, China today deploys a similar argument promoting the scope of “a community of shared future”3 with its strategic partners and to which more and more states look to join, where the GDI and the GSI are fundamental axes.

Introduction

As of the last quarter of the twentieth century, the global dynamics of capital accumulation have undergone significant change. For varying reasons, the large transnational corporations that organize the global production of commodities found it convenient to migrate numerous manufacturing processes toward the Asia-Pacific region (Amsden, 2001), thus refocusing the global capitalist economy on China and East Asia. Particularly from the beginning of the twenty-first century, China has become one of the states promoting this refocusing the most, also strengthening the Asian regional space which had been driven primarily by Japan since the 1970's. As Panitch and Gindin (2012) highlight, China's “open door” at the beginning of the twenty-first century greatly differs from that of a century ago, given that this time global capital did not enter by force but was rather invited (Panitch and Gindin, 2012, p. 294). This grants the country greater leadership, despite the fact that, as Zhou (2017) rightly highlights, China is the only nation offering international aid when a large part of its population is living in extreme poverty.

To assert this leadership, China is promoting an alternative international cooperation scheme to the so-called traditional one, which seems to emulate the second postwar US scheme, but in a different way with its own specifics4 and at a different timing. This idea emerges from an interpretation of the theoretical and historical perspective of Arrighi (1994) and (Arrighi and Silver, 1999), in which analogies are drawn between the capitalist and territorial agencies that drove the emergence and consolidation of the three hegemonic orders that have existed under the global capitalist economy. These orders are identified by the state that hosted the most competitive economies of the system at their time, namely the United Provinces of the Netherlands at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Great Britain in the nineteenth century, and the United States of America as of the second half of the twentieth century.

Each one of these hegemonic transitions went through moments of “chaos” at the systemic level, a situation in which the order consolidated by the receding hegemonic power is losing its legitimacy and, at the same time, an apparatus of global consensus alternative to the prevailing hegemonic order is being established, led by a new power which will eventually attain global hegemony (Cox, 1981; Arrighi, 1994; Wallerstein, 2011). Thus, the power that is on the rise drives the international community toward a direction that does not only serve its own interests but is also understood by the subordinate groups as serving a broader interest (Arrighi, 1994, p. 30). Therefore, the systemic consensus strategy is immersed in the specific hegemonic structure it tends to undermine. In this sense, the systemic consensus strategy that China has initiated does not opt for a rupture or confrontation with the declining hegemonic structure but emerges from it. In this way, it does not leave traditional multilateralism schemes while creating its own multilateral system that is presented as an alternative option.

In that same theoretical scheme, the power expansions are the result of the systemic reorganization that promotes the expansion by affording the system a division of labor, as well as a broad and profound specialization of functions; the emulation provides individual states the stimulus to mobilize their energy and resources for their own expansion. Insofar as the emulation is to some degree successful, it tends to counteract and, therefore, deflate instead of inflating the power of hegemony by creating competitors and reducing the “singularity” of hegemony (Arrighi and Silver, 1999, p. 27). This framework is useful for explaining how China develops a South-South international cooperation strategy as an “alternative scheme” in a context of systemic chaos, this means, in an anticipated moment with respect to which could be considered the new hegemonic center. This anticipation kept the Asian country active in the traditional cooperation scheme, while this has also served as an inspiration to transform Chinese relations with the world (Cabrera and Lo Brutto, 2022, p. 141).

We are not interested in tracing similarities and parallelisms with the strategies implemented throughout history by powers heading toward global hegemony; they have already been studied extensively.5 This study aimed at highlighting the South–South Cooperation (SSC) scheme that China is developing in the twenty-first century as a strategy of international leadership in its possible path to world hegemony, which can be considered as a process of early emulation of the US strategy in the current context of systemic chaos.

The substantial advance in our proposal refers to examining how China builds an entire interstate institutional infrastructure that can be analyzed analogously to the way in which the United States benefited from the postwar and Bretton Woods institutions as the basis of a new interstate system that provided a solution to a context of systemic chaos. There are specificities that distinguish both processes and here, we deepen the idea that there is an “early emulation” in the Chinese strategy with respect to the North American one that is synthesized in a double process: first, in the way in which China is currently articulating an institutional framework under the intensification of the present systemic chaos, that is, in a previous or “early” moment with respect to that in which we could consider clearly the rise of a new hegemonic power. Second, in a similar way to the multilateral consensus that underpinned the US project based on the promotion of “development” from the north to the south and with a fundamental role for cooperation and aid. China today deploys a similar argument promoting the scope of “a community of shared future” with its strategic partners and to which more and more states look to join, where the Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative are fundamental axes. Moreover, although it might seem to emulate the US strategy of the second half of the twentieth century, the combination of an alternative multilateral architecture with the presence of China in the currently existing one could allow the configuration of a new interstate consensus in the twenty-first century.

The article argues that this alternative political and economic scheme has allowed China to take influence over strategic routes and hubs for the production, distribution, and commercialization of commodities and to strengthen diplomatic relations with several countries. Furthermore, it affords China the possibility to promote the development of strategic spaces involved in the broad spectrum of the Belt and Road Initiative with certain autonomy from the United States, which is paving the way to Chinese hegemony in the current modern system.

To this end, we divide the article into four parts. The first section outlines a theoretical and historical review of the idea of an “early emulation strategy” that China appears to be developing. The second part presents China's South–South cooperation strategy as a new regime that offers an alternative to the traditional system of aid and cooperation. The third section approaches China's strategic cooperation as an early emulation in the context of systemic chaos that opens the possibility of a hegemonic transition from the United States to China in the twenty-first century. The chapter concludes with a section on final considerations.

Early emulation strategy

Arrighi (1994) defined this situation as one of “systemic chaos”: a specific moment in time when a new set of norms and behaviors are created and tend to prevail over an older set of norms without, however, entirely displacing it. This increases the calls to restore order: the old one, the new one, and any kind of order. The state that can satisfy these demands based on a specific symbolic and material project that is presented as the best proposal will become hegemonic; that is, it will assume leadership among those who agree to its initiative within a system of hierarchic interaction with the rest of the states (Arrighi, 1994, p. 32). This suggests the coincidence of systemic chaos with the stage of decline of a hegemonic cycle, in which the receding hegemonic power finds it increasingly difficult to maintain its global geopolitical order and turns to coercive elements to support it; this is what seems to have been happening in the United States during the last quarter of the twentieth century.

At the very moment the German armies surrendered, in May 1945, the world found itself on the verge of structural transformation. The terrible war had left people with a strong will for peace and the hope of a new world order, one based on a different system of state relations. The United States, which had been on the path to consolidation as a world power since the end of the nineteenth century, launched a political and institutional framework for the reconstruction of the global market and the transnational expansion of capital with the dissemination of Fordism and Taylorism as models of industrial production (Arrighi, 1982, p. 57). As had occurred in the previous hegemonic transition of the current modern system, that of the United Provinces of the Netherlands to Great Britain in the eighteenth century, the United States asserted its hegemony following a period in which the increase in interstate competition led to a hegemonic or total (Gilpin, 1988, p. 609–610). However, unlike the process of hegemonic reconfiguration involving the United Provinces and Great Britain, the interwar period and the 1929 recession challenged the interstate order that had been in place since the Peace of Westphalia, paving the way to a new order based on the Charter of the United Nations and the Bretton Woods monetary system.

Hardt and Negri (2000) criticize Arrighi's (1994) cyclical argument, claiming it is impossible to detect a rupture of the system for, if viewed this way, the history of capitalism becomes an eternal return of the same (Hardt and Negri, 2000, p. 239). Arrighi responded to this criticism by saying that his argument is by no means cyclical, that it rather places the periods of intensification of the interimperialist and intercapitalist rivalries, and their respective disruptions of the global market, within a broader historical perspective; and that this is done to understand that the efforts of today's hegemonic power in decline—the United States—to impose its exploitative rule over the world may well become a source of instability and self-destruction as serious as the ones that affected its predecessors (Arrighi, 2002, p. 13).

In this context, the hegemony model seems simple. When a state attains a notably superior agroindustrial productive efficiency, it enters the domain of commercial distribution spheres, gaining control of the financial sectors. However, as soon as a state becomes hegemonic, its decline in these spheres begins and it loses its advantages in the same order as it has gained them (productive, commercial, and financial). Nevertheless, a state ceases to be hegemonic not only because it loses force but also because others acquire it (Wallerstein, 2011, p. 38–39). Thus, the systemic chaos is prolonged until a new power attains hegemony by solving the system's problems and contradictions (Gilpin, 1988, p. 595). In other words, hegemony can be defined as a situation in which a state has the necessary power to impose the essential norms or regimes of the interstate system and the will to see them through (Keohane and Nye, 1977, p. 44). That is why Great Britain's incapacity to maintain a colonial world opened a period of systemic chaos which resulted in two world wars, sealed by a new normative order under the US global leadership (Jackson, 1993, p. 123).

The first of the processes articulated around the idea of an early emulation of the United States' actions, in the context of the twentieth-century hegemonic transition, has to do with the multilateral institutional framework with which its role as world hegemony was consolidated. Today, China has been building a wide-ranging multilateral scheme that is presented as an alternative to the contemporary version of the Western one without confronting it and even being part of it as well. This is posed at a level of analysis that takes up the role of the United States in its capacity to present itself as a leading state agency, without considering the dynamics of operation and interaction with the leading capitalist agencies at that time, an analysis in which we do not carry out in this study but that we consider relevant for the future.

The second process, embedded in the previous one, is associated with the role played by the promotion of “development,” particularly cooperation and aid, as mechanisms for market penetration and political influence on states at an individual and systemic level. For that purpose, it is important to mention that international cooperation, without being the only one to be analyzed but one of great relevance, becomes fundamental for two main reasons: first, because as Buscema (2020) comments, the international development cooperation promoted by the US was crucial in the consolidation of its hegemonic order. International development cooperation was the “field in which a set of instrumental practices of an eminently economic nature is deployed in view of attaining non-negotiable goals of an eminently political nature (world peace and harmony through the sharing of a dynamic of development); or, inversely, an array of actions of a substantially political nature is deployed to attain pre-eminently economic goals (capitalist valuation and accumulation through the global dissemination of the concept and the goal of development, operated through the conjunction, articulation, and harmonization of different subjects and considered as universally coveted)” (Buscema, 2020, p. 42); and, second, because we consider China has emulated the US strategy of international cooperation, albeit at an earlier time—before being considered a hegemonic center—and with some important modifications that are incorporated in The Belt and Road Initiative.

Regarding the first of these processes, it is worth remembering that US hegemony leaned on the signing of the 1941 Atlantic Charter, which brandished the right of the people to democratically elect their rulers and laid the foundations for interstate order based on the rule of law, which was ratified with the signing of the UN Charter, demolishing the British colonial order. Furthermore, academics tend to identify the hegemonic strategy of the US for consensus building with the speech made in 1947 by US President Harry S. Truman and, more specifically, with point IV, which launched the theoretical-institutional framework of what is known today as international development cooperation (Kragelund, 2018, p. 216). At that moment, the efforts were focused to promote development following a logic of stages, involving a distinction between a select group of modern and industrialized countries and a large majority of traditional economies that were considered underdeveloped (Rostow, 1960, p. 5).

The Truman administration also adopted an anti-USSR policy, accusing it of imposing totalitarian governments upon the free world. The tension between the Soviet Union and the US had a profound impact on the global economy. The Truman administration committed to putting US resources at the service of the reconstruction of Europe, not as much with the traditional objective of reinvigorating world commerce—although this continued to be important—but mostly with the more urgent goal of alleviating the social and economic conditions that could foster communism among its European allies (Gaddis, 1972, p. 316–317). To that end, the Marshall Plan promoted the reconstruction and future integration of Europe along with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), uniting member states through the commitment to provide mutual help in the case of military aggressions in Europe; the Organization of American States (OAS) was also signed under the same scheme, guaranteeing mutual assistance in the face of extraregional threats in America. The Truman Doctrine shifted its focal point to Asia in 1950, benefiting the Japanese industry and seeking to increase demand for its industry in the capitalist world.

At the same time, in the 1960's, numerous sovereign states had emerged after the processes of decolonization in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, which were welcomed by the institutions of the UN system (Jackson, 1991, p. 82). These institutions gave an account of a reality created by the victorious forces of World War II but concealed other experiences that deliberately excluded colonial forces, such as the 1955 Bandung Conference, which was held by Asian and African countries alone.

As for the UN framework, various regional commissions were proposed and created within its Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). The process of creating said commissions varies in time: the first two were the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE); both were established in 1947 and were mainly created to support the processes drawn out by the reconstruction plans: the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers (SCAP) for Japan and the European Recovery Program (ERP) for Europe.

From the UNECE sprang the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) in 1948, the precursor of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which was created in 1960 to coordinate the economic and social policies of the member states (Kindleberger, 1977, p. 52–53). Within this organization, the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) did not hesitate to consider the more industrialized countries the “custodians of the governance of Official Development Assistance” (OECD DAC, 2021). These multilateral schemes were so successful that in the decades following the creation of the OECD, the geographical location of its members transcended Europe to include other nations interested in joining.

To sum up, the hegemonic strategy of the US in the difficult postwar context was arguably grounded on proposals involving the states in international regimes and joint projects of liberal traits to counteract the high levels of the divisiveness of the past (Keohane, 1984, p. 9). In fact, Cox (1981) thought that when the world would set out to transition to a new hegemonic period, there would first have to be a multiplicity of state and international organizations equipped with a strong consensus apparatus to restore the international regulating authority that had characterized world hegemonies throughout history (Cox, 1981, p. 141–142).

Against this backdrop, the economic reconstruction and political reintegration of the countries of the South took place through long—and to date unfinished—struggles of national governments, social movements, and other minority groups for equal treatment and equal opportunities, both in cities of the North and in countries of the South. According to Wallerstein (1995), when the formula between universal suffrage and the welfare state failed, it was applied in a way that could be compared to the interstate system of the twentieth century. This liberal formula of international relations based on the self-determination of nations in addition to the economic development of underdeveloped countries was initially successful but ended up stumbling on the inability to create a welfare state at the global level (Wallerstein, 1995, p. 39).

What is observed today with China is that it emulates the United States with respect to the influence it exercises over the existing regional organizations, based on a new model of structural growth which does not attempt to create a global welfare state but does aspire to integrate the regions of the world in China's economic development (Lin and Wang, 2017, p. 7) without the need for homogeneous growth. That is why the Asian giant seems to be attaining world leadership by articulating its ideas of development in multilateral bodies, trade agreements, funding, experiences, and tactical knowledge vis-à-vis its allies. Arguably, the Chinese government has been rebuilding a “new South front,” appealing to and relaunching—some would say instrumentalizing—the discourse of Bandung (Amin, 2013, p. 82). At the same time, it is observed that the Chinese strategy differs from the North American one since its idea of structural development is not based on the construction of a common enemy as the Soviet Union was for the United States; on the contrary, it seems to seek to encompass all regions and countries, regardless of political position.

This can be exemplified in the way in which the Chinese government offers its allies ease of access to funds without imposing the same requirements as the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), that, according to Domínguez (2018), is undoubtedly the most important step in its effort to establish a new international regime of SSC that presents itself as an alternative one. This international SSC regime led by China is grounded on three pillars: financial and political international organizations such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA); a scheme of amplified funding for development promoted by China; and the monitoring and evaluation system (Domínguez, 2018, p. 38). It is precisely that this strategy can be defined as an “early emulation” that allows China to gain consensus before the failure and crisis of multilateralism, through the trust of a minilateralism (Wang, 2014).

Chinese strategy of SSC in the new millennium

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, Chinese aid has amounted to both a conceptual and a practical shift in the overall sphere of international cooperation and, more specifically, of South–South cooperation. This means that China has pursued cooperation with certain countries considered as “developing.” This does not mean that China does not have objective interests in accessing and tapping into natural and energy resources necessary for its booming economy; however, it does not exempt the Chinese government from the responsibility to protect national interests, observe international norms, and maintain strategic credibility vis-a-vis its allies (Yan, 2019, p. 9). Thus, the Chinese leaders considered the establishment of cooperation networks with countries considered strategic as a priority, signing separate agreements and individual commitments with them (Olguín, 2011, p. 589).

The main expression of Chinese leadership in global multilateralism seems to be the BRI, a multilateral agreement for the funding of infrastructure to improve China's connectivity with Europe and Africa, crossing central Asia, and even contemplating Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), a region that was not initially included. This megaproject has already been joined by over 160 countries, most of them emerging or developing.

However, a question raised by this megaproject of worldwide connection is whether it is indeed an initiative or rather a strategy of the Chinese government to consolidate its world hegemony. The difference lies in that an initiative is a unilateral action that requires voluntary and flexible cooperation, in which the interested parties can join or leave at any moment. A strategy, on the other hand, is an action plan that aims to attain specific goals linked to matters of security or trade (Xie, 2015). Oviedo (2019) considers The Belt and Road Initiative to be a strategic initiative; although it is a megaproject that coincides with China's strategic interests, the different states and international and regional organizations wish to actively participate in it.

As Cabrera and Lo Brutto (2022) say, the BRI was established with the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), founded in 2014 with USD 100 billion, the equivalent of half the money owned by the World Bank, and 57 founding members (92 today between regional and no-regional members and 13 between prospective regional and no-regional members),6 receiving investments even by US corporations such as Standard and Poor's, Moody's or the Fitch Group, despite the fact that the US does not intend to join the initiative (Suokas, 2018). As a source of financing, China has assumed the role of the world's largest development bank (Gallagher, 2018), with the AIIB financing only infrastructure projects that do not involve a joint development strategy and, therefore, do not interfere in the politics of the developing countries on the receiving end (Zhu, 2021).

Importantly, China's multilateralist ambitions have particularly prioritized SSC processes, acknowledging the importance of gaining allies to advance its geostrategic interests (Cabrera and Lo Brutto, 2022, p. 141). Despite the fact that China, today's powerful state on the rise, and certain developing countries do not appreciate the strategy of alliances, Xuetong (2016) considers that it is still an effective moral method through which leading countries can gain international support and also establish their authority (Yan, 2019, p. 65).

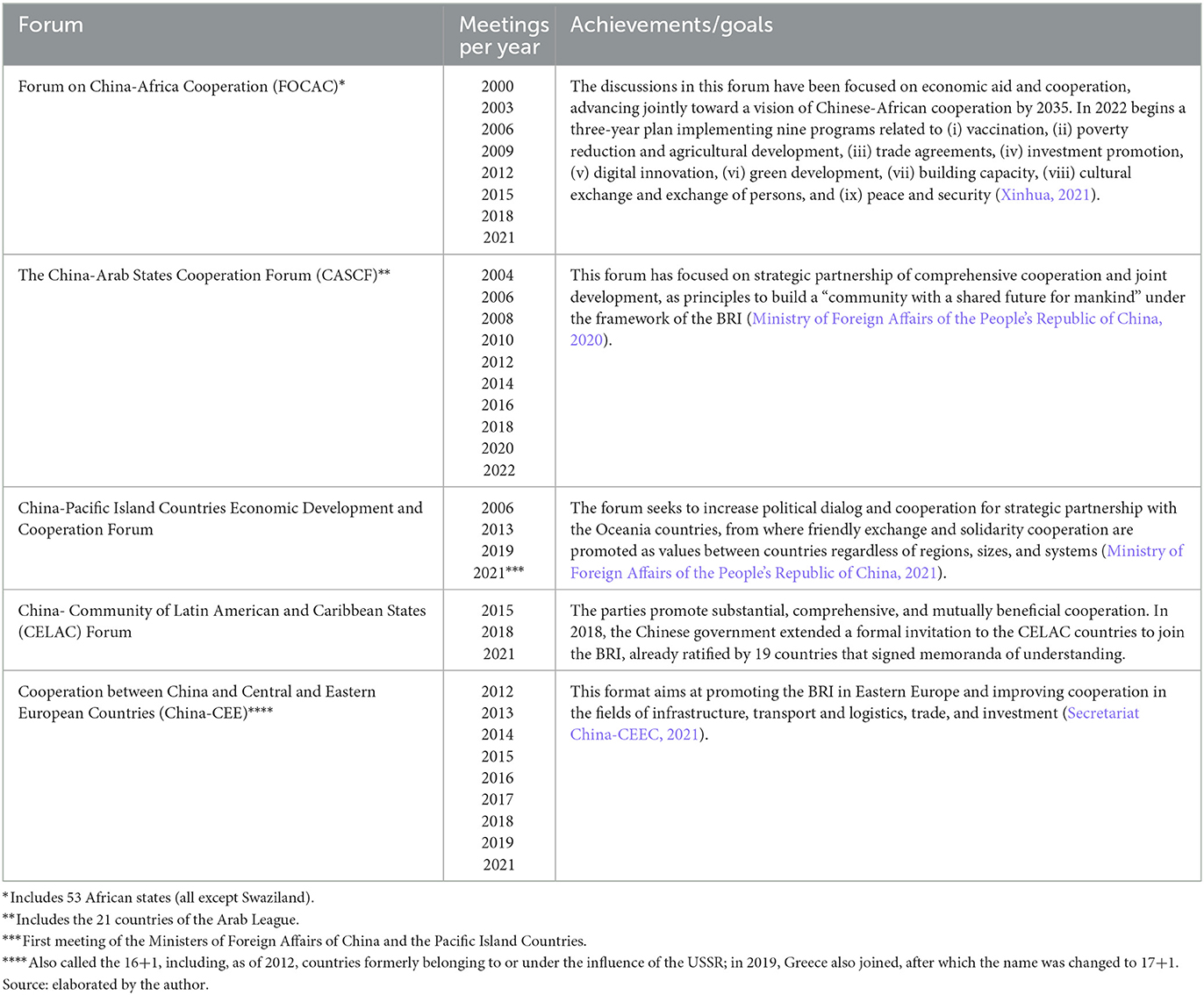

The following table shows the regional cooperation fora that the Chinese government upkeeps as points of global anchorage.

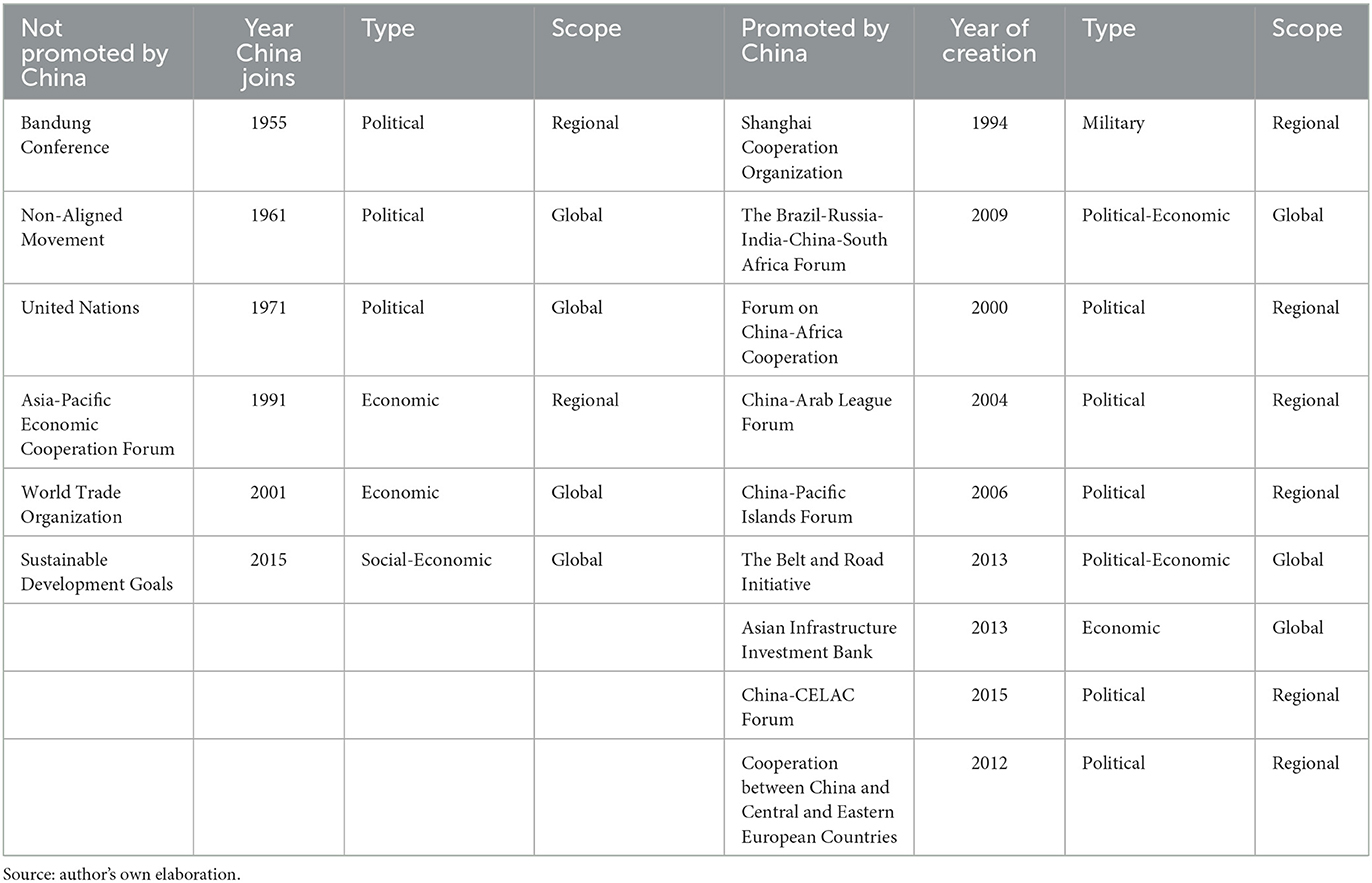

With these cooperation fora, China seems to be changing the world's perception to its favor, trying to balance out international relations, which have been dominated by the power of the US and its Western allies. We consider that this is another of the features of China's “early emulation” toward the construction of a new set of interstate relations, where the promotion of trade, investment in infrastructure, and cooperation for the development of the Asian country with the rest of the world is organized from these regional forums, with the same geographical sense in which the UN economic commissions were organized at the time.

The rupture of this equilibrium in favor of China could lead to a situation of global hegemony similar to the one in the aftermath of World War II led by the US when the status quo of the British colonial order was permanently overturned. In this context and with regard to its relations with Latin America, China has promoted dialog with the CELAC as a means of gaining influence in the LAC region, a platform including 33 countries, deliberately excluding the United States, Canada, and any other extraregional power (Cabrera and Lo Brutto, 2022, p. 150).7 In the European continent, specifically with regard to the traditional geopolitical influence of the EU, US, and Russia in Eastern Europe, the Chinese government holds another forum that also serves as a counterweight, the China-CEE forum. That can be seen on the following table (Table 1).

On the other hand, China significantly counterbalances the influence of Great Britain, the EU, the US, and Japan in Eastern Asia and the Pacific Ocean basin established through The Pacific Island Forum, the region's main integration organization.8 Furthermore, Chinese multilateralism advances in the region thanks to the entrenchment of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade mega-treaty signed by the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand in 2020, which adds up to almost one-third of the world population and 29% of the world's GDP [Channel News Asia (CNA), 2020].

Cabrera and Lo Brutto (2022, p. 151) highlight that China's actions are not only limited to its interaction in those regional fora but have also assumed increasing leadership in the agendas of global endeavors, such as the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set out by the United Nations.9 Furthermore, in 2015, Xi Jinping announced the China-UN Peace and Development Forum,10 given that the Asian country provides the most troops to UN peacekeeping operations, ~2,253 individuals, thus also becoming the permanent member of the Security Council with more blue helmets deployed (United Nations Peacekeeping, 2021).11 Therefore, the Chinese government has built its own multilateralism schemes, without leaving its participation in traditional multilateral organizations, which allows it to establish a set of alliances that project the advancement of new consensuses at the interstate level.

Table 2 shows that China seems to have benefited from its participation in liberal fora and organizations outlined by the US since the mid-twentieth century; that is why China partly maintains a defensive posture vis-à-vis this multilateralism as part of its national interests. In this sense, Chinese multilateralism seems to be also interested in the specialized organizations of Western multilateralism.12

China's strategic cooperation as an early emulation of systemic chaos

China has been gaining more and more prominence in the international scene ever since it redefined its external policy based on low-profile strategies proposed by the government of Deng Xiao Ping (1978–1989). Thus, China has become a champion of free trade and multilateralism at a time when the modern global system is in political and economic crisis and seems to be steering once again toward more protectionist policies that mark the beginning of a process defined as one of deglobalization.

Against this backdrop, President Xi Jinping made it clear that China strongly supports multilateralism. Chinese cooperation represents an alternative to the International Cooperation System. At least this is how President Xi Jinping seemed to express it during his discourse in Davos in January 2017, where he claimed that China sees itself as a leader in the continuation of the integration of the world economy at a moment when the support of the wealthiest countries is in decline (Suman, 2017). For President Xi

“China has not only benefited from economic globalization but also contributed to it. Rapid growth in China has been a sustained, powerful engine for global economic stability and expansion. The inter-connected development of China and a large number of other countries has made the world economy more balanced. China's remarkable achievement in poverty reduction has contributed to more inclusive global growth. And[sic] China's continuous progress in reform and opening-up has lent much momentum to an open world economy” (The State Council Information Office of People's Republic of China, 2017).

This Chinese strategy seems to balance out the important presence of the US in international institutions. In other words, China has been building an alternative institutionality to the prevailing one, which could lead to a new global consensus centered in China and Eastern Asia (Jabbour et al., 2021).

Since 2020, China has become the second largest contributor to the UN, providing 15.254%13 of the total amount the international organization expects to receive for the funding of its 2022 regular budget.14 In 2020, the Chinese government also committed to supporting developing countries with USD 2 billion to launch anti-epidemic value chains and make a vaccine it was developing against the new coronavirus disease that was detected at the end of 2019 (COVID-19) globally accessible; since then, COVID-19 has considerably disrupted the global economy (Xinhua, 2020). With this, China is pursuing the creation of a Sanitary Silk Road that will assert its solidarity vis-à-vis other countries of the world by articulating a multilateral scheme of medical cooperation (Cabrera and Lo Brutto, 2022, p. 159).

The spirit of multilateralism allowed China to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic with international cooperation while conducting an economic and social reactivation (Hu, 2020).15 Furthermore, during the pandemic, China became the world's largest exporter of direct foreign investment with 20.2% of the total volume of world investment, remaining above 10% for 5 consecutive years (Global Times, 2021).

Cabrera and Lo Brutto (2022, p. 152) point out that in contrast, then US President Donald Trump blamed the Chinese government for not revealing the true extent of the epidemic and accused the World Health Organization (WHO) of mismanagement, of covering up the spread of the virus and of offering China preferential treatment. The US government announced it would suspend its economic contribution to the WHO for those reasons, with no regard to the emergency of the pandemic (Mars, 2020). China's stance stands in contrast to the negligence and isolationism of the United States, which has had paralyzing effects on multilateralism and has amounted to some extent to the abandonment of its main allies, such as Western Europe and Japan, who learned to work unsupported; this seems to have led the US to exercise an “absent leadership”16 of sorts (Crivelli and Cejudo, 2021, p. 122).

President Joe Biden is trying to revert this lack of leadership by having the US rejoin the Paris Agreement and promoting new initiatives such as Build Back Better for the World, backed by the G7, as a response to China's Belt and Road Initiative, as well as trying to unite the Western world around the scheme of sanctions against Russia for its war against Ukraine. This outlines the present coexistence of two multilateral schemes: the traditional one led by the US since the mid-twentieth century and an alternative one fostered by China based on promoting regional associations and groups in the twenty-first century.

Another focus of the tensions and expressions of the crisis of Western institutions are financial/monetary networks. An example of the first case can be found around the use of the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) network for international interbank transactions and the Consolidated Highly Integrated Processor (CHIPS) network as the main international clearing house for high-value transactions in dollars: These mechanisms act as a monopoly and constitute a decisive tool of the hegemony of the United States in the global economy (Ramos et al., 2022). In this context, the exclusion of Russia from the traditional interbank system could accelerate its approximation to China, which has been trying to dissociate itself from the US financial hegemony and the CHIPS system of international payments for some time. Furthermore, in October 2015, the Chinese system of interbank payments was launched: the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) which is in the process of expanding. According to the state-backed newspaper Jiefang Daily, CIPS processed ~80 trillion yuan (USD 12.68 trillion) in 2021, a 75% increase from a year ago, in transactions involving financial institutions from 103 countries (Ramos et al., 2022).

In a recent visit to India, Russia's Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov said Russia has developed a system to trade in national currencies of countries such as India and bypass the US dollar (The New Indian Express, 2022). Russia is currently financially isolated, and the Europeans are reducing their dependency on Russian oil and other Russian products as fast as they can. For now, the Central Bank of the Russian Federation is artificially maintaining the value of the ruble by demanding that gas purchases be paid in this currency, thus creating a demand that this currency does not have. However, with the demand for trading in rubles, Russia could be outlining a new economic bloc where the dollar is no longer the reference currency, thus severely severing financial ties with the West and accelerating the fall of the dollar as the currency of value reserve par excellence.

The design of a new monetary/financial system through an association between the Eurasia Economic Union and China which will bypass the US dollar is emerging as a clear alternative to the Washington Consensus that will serve the needs of the Global South.

In any case, China seems to be emulating the strategy of cooperation and assistance adopted by the United States to consolidate its hegemony in the mid-twentieth century. However, the Asian country is deploying an alternative multilateral scheme that allows it to aim at being the focus of the world economy and a leader of the Global South. This results in the construction of new consensuses in the interstate system of the twenty-first century under the principles of a multipolar order unlike the present one. The recent events in Ukraine and, to a lesser extent, Taiwan show that the construction of an interstate system also includes the possibility of war; this was not necessarily contemplated until recently as a characteristic of China's rise to hegemony, which has been considered mostly pacific. To sum up, we suggest this emulation has been one of the nodal points that have led to China being considered a potential new hegemonic leader of the world economy.

Conclusion

It is precisely this characteristic of coexisting with the “currently prevailing” while building “what is new” that characterizes China's strategy in the context of its South–South cooperation with the different countries of the world, defined as an early emulation that helps it gain consensus within a process of “reglobalization” and an increasingly tense context. This reflects how this systemic chaos is heading toward a new global consensus that is centered in China and East Asia. Moreover, although it might seem to emulate the US strategy in the twentieth century, the combination of an alternative, multilateral architecture with China's presence in the currently existing one could allow for the construction of this new interstate consensus in the twenty-first century.

China develops a strategy with specificities that are presented as an “alternative scheme,” at a time in which it cannot yet be considered the hegemonic leader of the world economy, while the US implemented it when there was already clear consensus on its leadership. It is precisely this anticipation of China's possible rise to a new world hegemonic center that has kept the country active in its participation in the traditional scheme which, in some way, has served as a transforming inspiration.

This emulation has been a positive strategy which, along with other mechanisms, has allowed the Asian country to create deeper relations with all national economies and more specifically with the so-called economies of the South. In this sense, the SSC scheme, both in its political and economic connotation, has granted China among other things, diplomatic, politics, and economics. At least the possibility to enter and promote the development of strategic spaces that declare their autonomy with regard to US influence. This is contemplated within the broad spectrum of the BRI, the GDI, and the GSI, and it is a focal point in the consideration of China as a potential new hegemonic leader of the global economy.

Finally, it will be essential for this research to explore the dynamics of capitalist agencies related to the Chinese leadership and its ability for mercantile and financial innovation, to advance the proposal that there is an early emulation of China in systemic chaos. This, emphasizes the elements in which, unlike the leading capitalist agency model of the early twentieth century, it was characterized by assuming the transaction costs of the different moments of the production process and merchandise circulation, innovating with respect to the main capitalist agency during British hegemony by becoming a multi-departmental company with different locations that generated economies of speed rather than size (Arrighi and Silver, 1999). Thus, the next thing will be to locate the specificity with which companies linked to the Chinese state operate, establishing a kind of alliance that potentially allows the latter to become the new world hegemony.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Announced by Xi in the framework of the 76th UN General Assembly in 2021, with the idea of accelerating the implementation of the 2030 Agenda.

2. ^Announced at the Boao Forum of Asia in 2022, proposing the principle of indivisible security in Asia.

3. ^Mentioned by Xi Jinping on the 70th anniversary of the UN in 2015 and integrated into the statutes of the Chinese Communist Party in 2017 and the Constitution in 2018.

4. ^Political dialog, trade agreements, and financing for development.

5. ^The historical correlation of productive capacity and military force that granted the US world hegemony following World War II has been approached through the logic of the rise and fall of the great powers (Kennedy, 1987; Gilpin, 1988), the construction of national interest and the balance of power (Morgenthau, 1952; Waltz, 1979), the hegemonic stability in the world economy (Kindleberger, 1973; Keohane, 1984), the construction of power blocs (Silva, 1976; Cox, 1981), or the changes and recenterings in the dynamics of world capitalism (Braudel, 1992; Arrighi, 1994; Wallerstein, 2011).

6. ^https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/governance/members-of-bank/index.html

7. ^In 2018, the Chinese government even proposed a free trade agreement with the countries of the LAC region, although nothing has been concretized as of yet.

8. ^The Forum began with five founding Dialog Partners (Canada, France, Japan, the UK, and the US). China became the sixth Dialog Partner in 1990. The number of partners has grown progressively since then, and there are currently 21 partners (Pacific Islands Forum, 2021).

9. ^The SDGs are part of China's economic strategy which showed its commitment with the International Union for Conservation of Nature, also organizing the first World Forum on Ecosystem Governance, where over 150 experts from 50 countries looked into the ways of achieving an ecological and sustainable global future (Kolodziejczyk, 2015).

10. ^In 2016, China became the second largest contributor in the costs of upkeeping peace in this organization, making up for almost 15.21% of its total budget between 2019 and 2021, following the US who contributed almost 27.98% of the total cost during that period (United Nations General Assembly, 2020).

11. ^China is a member of the UN Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations since 1988.

12. ^China chairs four of the 17 specialized organizations of the United Nations.

13. ^This represents a net quota of USD 438.197.136.

14. ^The United States and Japan are expected to contribute 22 and 8.033%, respectively (United Nations Secretariat, 2022).

15. ^The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a vaccine cold war of sorts, in which China, the United States, and Russia competed to distribute the medicine (Horowitz and Zissis, 2021).

16. ^Then, US President did not hesitate to withdraw his country from various multilateral fora, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the UN Human Rights Council in 2018, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2020, and the World Trade Organization, from which it will effectively leave in 2021 (Crivelli and Cejudo, 2021, p. 122).

References

Amsden, A. (2001). The Rise of “The Rest”: Challenges to the West from. Late- Economies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Arrighi, G. (1982). “A crisis of hegemony,” in Dynamics of Global Crisis, eds A. Samir, G. Arrighi, A. G. Frank, and I. Wallerstein (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press), 55–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-16853-8_3

Arrighi, G. (1994). The Long Twentieth Century Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. New York, NY: Verso.

Arrighi, G. (2002). Lineages of empire. Historical Material. 3, 3–16. doi: 10.1163/15692060260289699

Arrighi, G., and Silver, B. J. (1999). Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Braudel, F. (1992). Civilization & Capitalism 15th-18th Century, the Perspective of the World, Volume III. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Buscema, C. (2020). “La cooperación internacional: entre caos y el gobierno del mundo,” in Pasado y presente de la cooperación internacional: una perspectiva crítica desde las teorías del sistema mundo, coord, eds S. Caria and I Giunta (Quito: IAEN), 29–58.

Cabrera, A., and Lo Brutto, G. (2022). “China and the road to an alternative interstate consensus,” in G20 Rising Powers in the Changing International Development Landscape, ed E. P. Dal (London: Palgrave-Macmillan), 139–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-07857-6_7

Channel News Asia (CNA). (2020, November 15). Asia-Pacific nations sign world's largest trade pact RCEP. Channel News Asia. Available online at: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/business/rcep-trade-pact-asean-summit-singapore-china-680986 (accessed March 15, 2022).

Cox, R. W. (1981). Social forces, states and world orders: Beyond international relations theory. Millennium. 10, 126–155. doi: 10.1177/03058298810100020501

Crivelli, E., and Cejudo, T. (2021). El liderazgo ausente de los Estados Unidos en el siglo XXI. Revista de Filosofía ?δ?ς/Hodós. 10, 109–127.

Domínguez, R. (2018). Hacia un régimen internacional de Cooperación Sur-Sur: últimos avances sobre el monitoreo y la evaluación. Estado abierto. 2, 49–107. doi: 10.21530/ci.v13n1.2018.737

Gaddis, J. L. (1972). The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941-1947. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Gallagher, K. P. (2018). China's Role As the World's Development Bank Cannot Be Ignored. NPR. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2018/10/11/646421776/opinion-chinas-role-as-the-world-s-development-bank-cannot-be-ignored

Gilpin, R. (1988). The theory of hegemonic war. J. Interdiscipl. Hist. 4, 591–613. doi: 10.2307/204816

Global Times (2021). China Ranks No.1 Globally in Outward FDI for the First Time. Available online at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1235451.shtml (accessed May 2, 2022).

Horowitz, L., and Zissis, C. (2021). Timeline: Tracking Latin America's Road to Vaccination. AS/COA. Available online at: https://www.as-coa.org/articles/timeline-tracking-latin-americas-road-vaccination#chart-progress-of-vaccine-rollout (accessed May 05, 2022).

Hu, L. (2020, February 9). Covid-19, desarrollo y multilateralismo, China ha respondido a la pandemia en paralelo con la reactivación económica y social; y la coop- eración internacional [Covid-19, Development and Multilateralism, China has Responded to the Pandemic in Parallel with Economic and Social Reactiva- tion; and International Cooperation]. Portafolio. Available online at: https://www.portafolio.co/opinion/otros-columnistas-1/covid-19-en-china-multilateralismo-y-desarrollo-embajador-lan-hu-548981

Jabbour, E., Dantas, A., and Vadell, J. (2021). “Da nova economia do projetamento à globalização instituída pela China. Estudos Internacionais 4, 90–105. doi: 10.5752/P.2317-773X.2021v9n4p90-105

Jackson, R. H. (1991). Quasi-States: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, R. H. (1993). “The weight of ideas in decolonization: Normative change in international relations,” in Ideas and Foreign Policy Beliefs, Institution, and Political Change, eds J. Goldstein and R. Keohane (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), 111–138. doi: 10.7591/9781501724992-007

Kennedy, P. (1987). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York, NY: Random House.

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After Hegemony. Cooperation and Discord in World Political Economy. Princeton, NJ: New University Press; Princeton University Press.

Keohane, R. O., and Nye, J. S. Jr. (1977). Power and Interdependence. World Politics in Transition. Boston: Litle Brown.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1973). The World in Depression, 1929-1939. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1977). America in the World Economy. (Headline Series 237). New York, NY: Foreign Policy Association.

Kolodziejczyk, B. (2015). Will China Become a Global Environment Leader? World Economic Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/11/will-china-become-a-global-climate-leader/ (accessed April 15, 2022).

Kragelund, P. (2018). “International cooperation for development,” in The Essential Guide to Critical Development Studies, eds H. Veltmeyer and P. Bowles (New York, NY: Routledge), 215–224. doi: 10.4324/9781315612867-17

Lin, J. Y., and Wang, Y. (2017). Going Beyond Aid, Development, Cooperation for Structural Transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge Press University.

Mars, A. (2020). Trump acusa a la OMS de “encubrir” la propagación del coronavirus y anuncia la congelación de los fondos El País on April 14. Available online at: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2020-04-15/trump-acusa-a-la-oms-de-encubrir-la-expansion-del-coronavirus-y-anuncia-la-congelacion-de-los-fondos.html (accessed April 10, 2022).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China (2020). Foro de Cooperación China-Árabe Celebra Novena Reunión Ministerial [China-Arab Cooperation Forum Holds Ninth Ministerial Meeting]. MFA-China. Available online at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/esp/wjb/zzjg/xybfs/xwlb/202007/t20200707_943937.html (accessed March 15, 2022).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China (2021). Wang Yi Preside Primera Reunión de Ministros de Relaciones Exteriores de China y Países Insulares del Pacífico [Wang Yi Chairs the First Meeting of Foreign Ministers of China and Pacific Island Countries]. MFA-China. Available online at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/esp/wjb/zzjg/bmdyzs/xwlb/202110/t20211022_10413340.html (accessed March 15, 2022).

Morgenthau, H. J. (1952). Another ‘great debate': The National interest of the United States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 46, 961–978. doi: 10.2307/1952108

OECD DAC (2021). Declaration on a New Approach to Align Development Co-operation With the Goals of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. OECD. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/dac-declaration-climate-cop26.htm (accessed March 15, 2022).

Olguín, P. M. (2011). El compromiso de China con el desarrollo del tercer mundo: el caso Angola Estudios de Asia y África. Estudios de Asia y África 3, 589–649.

Oviedo, E. D. (2019). Oportunidades, desafíos e intereses de Argentina. Observatorio de la Política China. Available online at: https://politica-china.org/areas/politicaexterior/oportunidades-desafios-e-intereses-de-argentina-en-obo (accessed March 15, 2022).

Pacific Islands Forum (2021). Forum Dialogue Partner. Pacific Islands Forum. Available online at: https://www.forumsec.org/dialogue-partners/ (accessed March 18, 2022).

Panitch, L., and Gindin, S. (2012). The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire. New York, NY: Verso.

Ramos, L., Vadell, J., and Gontijo, C. (2022). Reordenamiento Global: la guerra de Ucrania, las sanciones a Rusia y las trampas de la “astucia de la naturaleza”. El País. Available online at: https://www.elpaisdigital.com.ar/contenido/reordenamiento-global-la-guerra-de-ucrania-las-sanciones-a-rusia-y-las-trampas-de-la-astucia-de-la-naturaleza/34471 (accessed January 27, 2023).

Rostow, W. W. (1960). The Stages of Economic Growth. A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Secretariat China-CEEC (2021). Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries. China-CEEC.org. Available online at: http://www.china-ceec.org/eng/zdogjhz_1/ (accessed May 02, 2022).

Suman, B. (2017). Engagement in a Time of Turbulence, Global Policy. Available online at: http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/21/07/2017/engagement-time-turbulence (accessed April 10, 2022).

Suokas, J. (2018). AIIB Looks to Attract Private Financing for Projects. Findchina. Available online at: https://findchina.info/aiib-looks-to-attract-private-financing-for-projects (accessed April 18, 2022).

The New Indian Express (2022). Rupee-Ruble System Will Help Bypass “Illegal Sanctions,” Says Lavrov During India Visit. The New Indian Express. Available online at: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2022/apr/01/rupee-ruble-system-will-help-bypass-illegal-sanctions-says-lavrov-during-india-visit-2436805.html (accessed April 20, 2022).

The State Council Information Office of People's Republic of China (2017). Full Text: Xi Jinping's Keynote Speech at the World Economic Forum. China.org.cn. Available online at: http://www.china.org.cn/node_7247529/content_40569136.htm (accessed May 15, 2022).

United Nations General Assembly (2020). Approved Resources for Peacekeeping Operations for the Period From 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021. General Assembly Resolution 49/233. Available online at: https://undocs.org/en/A/C.5/74/18 (accessed May 15, 2022).

United Nations Peacekeeping (2021). Contribution of Uniformed Personnel to UN by Country and Personnel. Type. Report 30/11/2021. Available online at: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/troop-and-police-contributors (accessed April 16 2022).

United Nations Secretariat (2022). Assessment of Member States' Advances to the Working Capital Fund for 2022 and Contributions to the United Nations Regular Budget for 2022. ST/ADM/SER.B/1038. Available online at: https://undocs.org/en/ST/ADM/SER.B/1038 (accessed March 15, 2022).

Wallerstein, I. (2011). The Modern World-System II Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600-1750. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520948587

Wang, H. (2014). From “Taoguang Yanghui” to “Yousuo Zuowei”: China's engagement in financial minilateralism. CIGI Pap. 52, 1–10.

Xie, T. (2015). Is China's ‘Belt and Road' a Strategy? The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2015/12/is-chinas-belt-and-road-a-strategy/ (accessed April 01, 2022).

Xinhua (2020). Full Text: Speech by President Xi Jinping at opening of 73rd World Health Assembly. Xinhuanet. Available online at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-05/18/c_139067018.htm (accessed June 10, 2022).

Xinhua (2021). Full Text: Keynote Speech by Chinese President Xi Jinping at Opening Ceremony of 8th FOCAC Ministerial Conference. FOCAC. Available online at: http://www.focac.org/focacdakar/eng/zxyw_1/202112/t20211202_10461076.htm (accessed June 21, 2022).

Zhou, H. (2017). “China's foreign aid policy and mechanisms,” in China's Foreign Aid. 60 Years in Retrospect, ed Z. Hong (Singapore: Springer), 281–324. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-2128-2_1

Zhu, M. (2021). La condicionalidad de los préstamos del Banco Mundial y del Banco Asiático de Inversión en infraestructura. (Tesis de máster), Universidad de Barcelona, Dipòsit Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/2445/178806 (accessed June 15, 2022).

Keywords: hegemony, hegemonic transition, South-South cooperation, systemic chaos, China

Citation: Cabrera García AC and Lo Brutto G (2023) Role of the China South–South cooperation hegemonic strategy as an “early emulation” in a context of systemic chaos. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1081861. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1081861

Received: 27 October 2022; Accepted: 14 April 2023;

Published: 15 May 2023.

Edited by:

Xing Li, Aalborg University, DenmarkReviewed by:

Tayden Fung Chan, Lingnan University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaMaria Eugenia Giraudo, Durham University, United Kingdom

Bruno Haeming, Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

Copyright © 2023 Cabrera García and Lo Brutto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giuseppe Lo Brutto, Z2l1c2VwcGUubG9icnV0dG9AY29ycmVvLmJ1YXAubXg=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Ada Celsa Cabrera García

Ada Celsa Cabrera García Giuseppe Lo Brutto

Giuseppe Lo Brutto