- 1Department of Regional Planning, Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg, Cottbus, Germany

- 2Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

This article compares one emerging and three established regional development agencies in rural regions in Germany as examples of collaborative governance for socially innovative regional development. We ask, firstly, how an emergent collaborative regional governance network can be institutionalized in the long term based on participatory mechanisms on several levels as well as between actors with different goals and values. Secondly, how an organizationally thin, rural context influences the governance network in steering the social innovation promotion and what kind of development for whom do different governance networks mobilize. Research was conducted as a qualitative comparative case study with semi-structured expert interviews. The findings highlight that the institutionalization of collaborative governance is supported by funding and policies from upper scales and the model of regional development agency enhances the learning of collaborative governance between public institutions. However, the goal and beneficiaries of the development are mainly the classic economic actors, whereas transformative grassroots movements enhancing social innovation are largely ignored by public-driven collaborative governance.

1. Introduction

Public institutions are facing the challenge of providing reliable services that respond and adapt to wicked global problems in increasingly diverse and complex societies (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015, p. 6–9). Collaborative governance has been suggested as one solution to enhance the ability of public policy to address persistent and boundary-crossing challenges while remaining efficient and legitimate. The concept of collaborative governance refers to the process where “relevant and affected actors in networks and partnerships […] exchange and pool resources and constructively manage their different interests, ideas and perceptions in the pursuit of joint solutions to common problems” (Sørensen and Torfing, 2021, p. 1590). Governance generally refers to various modes of coordinating social relationships (Jessop, 2020, p. 245). Collaboration between different actors can be interpreted as one of these modes, especially when it comes to the self-governing of societal actors or co-governing between the state and societal actors (Kooiman, 1999). The emergence of collaborative governance has been widely studied in the context of regional development since the 1990s. Regionalization processes (Benz and Fürst, 2003), the rescaling of the state (Brenner, 2004), the emergence of metropolitan regions as action arenas for collaborative governance (Blatter, 2005; Salet et al., 2005), the transformation of regional economies and emergence of managerial approaches in the field of rural and urban development (Buchholz, 2006; Elbe, 2007), or new collaborative constellations of renewable energy production (Klagge and Brocke, 2012; Gailing and Röhring, 2016) are examples of this perspective.

Studying regional development from the perspective of collaborative governance means analyzing collective actors (such as organizations or networks of stakeholders) and both their modes of coordination and institutional frameworks. New public-private constellations, such as regional development agencies (RDAs), have emerged numerously and received wide attention in the literature (Webb and Collis, 2000; Thurmann, 2010; Bellini et al., 2012). The RDAs actively shape the future visions for the regions and the means to realize them. But their success is also related to the material trajectories of regional disparities that the new governance efforts build upon, implying that particularly rural and peripheral regions may face special challenges in supporting collaborative governance (Gailing and Röhring, 2016; Castro-Arce and Vanclay, 2020). Thus, approaching collaborative governance from a perspective that takes specific regional aspects, such as spatial inequalities, power constellations or the key role of social innovation (SI), into consideration may help people to understand better to what kind of transformation new collaborative governance formations actually contribute. We refer to SIs as new social practices, services and ways of organizing that contribute to sustainable and inclusive development and societal transformation by tackling regional and societal challenges (Moulaert et al., 2013, p. 15–16; Hölsgens et al., 2018).

Compared to growing urban agglomeration areas, peripheral regions are socioeconomically and politically disadvantaged and relatively sparsely populated. Their governance constellations have been typically analyzed in the regional development literature as “institutionally thin” or “organizationally thin,” referring to the lack and ineffectiveness of interacting organizations and informal institutions that promote (economic) development (Isaksen and Trippl, 2014; Beer and Lester, 2015; Flåten et al., 2015). However, this concept has received major criticism as it has been empirically explained with a very narrow set of organizations, usually business support organizations, and often conflating them with informal institutions (Gibbs et al., 2001; Zukauskaite et al., 2017). Furthermore, it tends to overly emphasize the importance of the physical closeness between diverse and qualified knowledge producers for innovativeness (Lang et al., 2019, p. 20–23). Studies focusing on economically prosperous regions often assume a direct causal connection between the presence of knowledge organizations and economic development, ignoring both the role of other types of connections across space and the sustaining role of “traditional” organizations, such as state power, civil society and local small enterprises (Macleod and Goodwin, 1999; Gibbs et al., 2001). Finally, the studies also seldom question for whom and what kind of aims the institutional thickness is beneficial. As Macleod and Goodwin state, “[t]he relations between [the institutions] reflect broader conditions of power and control; quite simply, some institutions are more equal than others when it comes to building and deploying policy agendas” (1999, p. 514).

Therefore, in this research, collaborative governance and specifically the concept of SI is applied to observe and define more clearly what institutional thickness might mean in practice in the development of collaborative regional governance institutions in peripheral regions in the long term. The normative definition of SI in our research does not pay attention to the outcome of the development efforts primarily in economic terms but rather in their contribution to more holistic and sustainable development. Recent literature is increasingly questioning the norm of linear economic development and growing urban metropolises as the optimal model of regional development generally (Syssner, 2016, p. 56–58; Brückner, 2017; Dax and Fischer, 2018; Jones et al., 2018). Instead, studies encourage diverse development visions and practices oriented toward a qualitative and resilient improvement of the living conditions within global ecological boundaries. They do not simply demonize shrinking as the negative opposite of metropolitan growth or attempt to simulate the solutions and patterns of the centers, but recognize and build upon the specific strengths and context-specific solutions in the regions (Dax and Fischer, 2018). These approaches of growth-independent development are also in line with understanding “regions as a resource” and with the concept of an “open region” (Schmidt et al., 2018), which is open to new solutions, services and ways of organization as well as experiences from other regions. Dehne (2019) interprets such an “open region” as an arena for empowerment and enabling practices to create new or adapted solutions for the regional economy, which is largely shaped by local and regional actors as well as by their collaborative networks.

We discuss the steering and promotion of SIs through a collaborative governance constellation as an empirical example of such means for alternative development in periphery. In order to observe the impact of the SI promotion on the growth-independent economic development perspectives, the empirical field of SI promotion relates to the development of regional value chains. Based on the comparative research of peripheral regions in Germany, this paper examines how an emergent collaborative regional governance network for SI promotion can be institutionalized in the long term based on participatory mechanisms on several levels and between actors with different goals and values. Institutionalizing collaborative governance refers to the process of establishing collective actors (such as organizations or networks of stakeholders) by means of co-governing in a multi-actor-perspective. We, therefore, analyze how an organizationally thin, rural context influences the governance constellation in steering the SI promotion and what kind of development for whom do different governance networks mobilize within the context of an innovation discourse. Finally, we want to draw lessons from the case studies for other “organizationally thin” regions. The theoretical framework will be presented and conceptualized in detail in the following section. Subsection three describes in detail the data selection process and the research methodology. The subsequent section outlines, firstly, the emergence and steering of a case study network on whose development the authors have been participating during the last three years. Secondly, we will reflect on learnings from other, comparative case study regions in the German rural regions of Rhineland-Palatinate, Schleswig-Holstein and North Rhine-Westphalia. Finally, we reflect on what kind of development and innovativeness the networks have achieved and whether they have succeeded in fostering the transformative promise of the SI discourse.

2. Institutionalizing social innovations at the regional scale

In the field of political science, collaborative governance and innovations have mostly been discussed as a result of policy learning and in the context of the governance mechanisms of regional development (Benz, 2021; Heinelt et al., 2021). In this regard, SIs have been particularly discussed as a means to reform the public governance and service provision system so that it can better incorporate the needs of the diverse stakeholders in service provision, respond to complex societal problems and empower actors normally excluded from the decision-making processes (Pradel Miquel et al., 2013, p. 155; Teasdale et al., 2021).

The promotion of SI has been also studied in the context of rural development. Here the research focuses on the change of mundane practices of the collaboration and revalorizing of value chains based on the local resources and capacities at hand, such as small-scale agriculture, civic engagement and quality of life (Domanski et al., 2020; Pel et al., 2020). This potential is commonly overlooked in the classical economic development strategies due to the prioritization of expert-led technological innovation (Bock, 2012; Domanski et al., 2020). Therefore, SI might be a suitable focus of development, especially for organizationally thin rural areas that simply lack the preconditions of “catching up” with the technological and industrial competitiveness of the metropolitan or industrialized rural areas. Furthermore, fostering SIs relies on the potential of slow, incremental and unforeseeable transformation processes, which are, according to Isaksen and Trippl (2014), typical development paths for rural areas. However, such incremental innovativeness is typically seen in the economic development literature as a threat of economic stagnation (Isaksen and Trippl, 2014) instead of an opportunity to locally negotiate and adapt the transformation so that it can actually improve the region's wellbeing in a spatially and situationally suitable way (Moulaert and Sekia, 2003; Jones et al., 2018). As Dax and Fischer summarize:

“A local supply for goods and services by re-inventing local value chains can provide a chance to disconnect from the global economy, at least temporarily. Thus, rural areas can take on new significance by providing the relevant resources for experimental and pilot actions like a special focus on local products in public procurement, regional currencies, barter economies, food co-ops, etc.” (2018, p. 308)

Currently, however, such promising characteristics of shrinking regions are typically overlooked as they do not fit into the normative understanding of a global hub of knowledge production (Syssner, 2016).

Thus, from the perspective of rural and local development, SIs have usually been studied as bottom-up, self-organized initiatives whose “empowerment is often implicitly or explicitly related to the extent to which innovations and ‘niches' can survive, thrive and possibly even replace existing institutions or ‘regimes”' (Avelino et al., 2020, p. 956). Here, the focus is on the self-governance of the SI networks rather than the public governance framework. Pel et al. (2020) and Galego et al. (2022), for example, have extensively summarized and typologized the emerging governance capacities of self-organized networks. However, apart from a few, progressive metropolitan cases (e.g., Kim, 2022), the majority of the studies remain silent on the relationship of grassroots networks to existing public institutions. Hölsgens et al. (2018, p. 3) state that “because of the focus on “green” niche-innovators, transition-scholars have paid less attention to existing regimes and incumbent actors, and often conceptualized the regimes merely as ‘barriers to be overcome.”' At the same time, the political science research on governance of SIs tends to ignore the spatial and geographic context of the governance, especially from the perspective of peripheral regions. Therefore, our contribution aims to fill these gaps by discussing the long-term institutionalization process of collaborative governance constellations in peripheral regions from the perspectives of both publicly-led governance efforts as well as grassroots networks.

Economic resources and young civic networks that commonly drive transformative initiatives are limited in the peripheries, and, thus, public and political support for their stabilization is especially necessary (Salemink et al., 2017; Kovanen, 2020). Nevertheless, this support is often inadequate in practice, as are the local public sector's lack of resources and competence for supporting (socially) innovative activities. The example of the evaluation of the “Regionale” program in Cologne in 2010 has shown that a successful development infrastructure should emerge as a collaborative effort between public administrations on broader scales, academia and diverse local actors, so that the local administration is not left alone with the responsibility (Kuss et al., 2010).

Collaborative governance constellations envision a possible intermediary development agent. The participation of different kinds of actors within a governance network may serve as an impetus to refigure the governance structures themselves and, thus, deepen the degree of transformation of institutions (Kim, 2022). Under the notion of metagovernance (Jessop, 2020), collaborative governance may enhance the capacity of questioning and rethinking of norms, values and working mechanisms of the governance structure. A participatory governance network built upon collaboration implies a stronger inclusion of those who are concerned and affected by its potential steering processes and outputs (Schmitter, 2002, p. 56; Heinelt, 2010; Ulrich, 2021, p. 69), such as citizens, civil society organizations, economic local and academic partners and municipalities. The actors require different ways and practices of participation in regional governance and can be actively or passively involved. Emerson and Nabatchi (2015, pp.41–49) have identified the following drivers of starting a collaborative governance network:

- Uncertainty about the correct solution to a complex problem.

- Recognition of the interdependency of the actors in finding the solution.

- Consequential incentive, such as a political mandate or targeted funding, to work together.

- Initiating leadership.

Several studies have also highlighted some tensions and challenges in the collaboration between grassroots initiatives and public institutions (Joutsenvirta, 2016; Salemink et al., 2017). Lang et al. (2019) explain that the classic innovation discourse focuses overly on a supposed benefit of physical closeness for innovativeness and, thus, tends to ignore other forms of closeness and distance, such as cognitive and value-based. These forms of closeness may, for example, link rural grassroots actors to like-minded cross-regional civic networks, but distance them from public institutions within the same region. Thus, it is relevant to question how diverse actors in emerging collaborative networks deal with their competing and contradictory aims and visions. According to Huxham et al. (2000), collaborative governance is typically complex, ambiguous and very resource-intensive. Committing to a minimum joint aim is a lengthy process, which requires patient and empathetic communication to overcome conflicts and tensions in the process. Increasing the accountability of a collaborative governance institution usually implies broadening the participation, but this, again, may overly complicate and slow down the decision-making processes and, thus, reduce the legitimacy (Cristofoli et al., 2022; Dupuy and Defacqz, 2022).

Therefore, in this article we compare different structures and approaches for regional SI promotion which are based on collaboration with bottom-up and regional governance actors to different extents. Studying different successful examples of collaborative governance in rural regions may help to advance the conceptualizations on what aspects in rural structures and institutions precisely, other than the mere close physical presence of institutions in knowledge-based industry, actually contribute to progressive development in peripheral regions. Additionally, concerning the tensions between grassroots innovations and established institutions mentioned above, there is a need to question what kind of development and for whom the networks generate while institutionalizing and to what extent the ambition of reaching a broad alliance for holistic, sustainable transformation has or has not been realized. Establishing a participative and proactive governance constellation is often stated as a success in itself (Kuss et al., 2010; Füg and Ibert, 2019), therefore, it is also important to pay attention to the actual contents and compromises that such an achievement might imply.

3. Materials and methods

Our study arose out of a research and innovation network in a peripheral region in North-Eastern Germany funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research from 2019 till 2025. The authors of the article accompanied the network's strategy development and analyzed the region's innovation environment and governance. The network is called “Region 4.0” and functions as the first empirical case of a collaborative governance constellation within this article. The original aim of the funding for the network had been to foster a transition in structurally weak regions toward sustainable livelihoods.

The research is applied as a qualitative comparative case study. This approach helps to explain outcomes by identifying similar patterns across different contexts and question phenomena that are considered universal within their context (Lang, 2018). The data collection resulted in two phases with different focuses. In the first phase, from November 2019 till the end of 2020, 25 actors within the “Region 4.0” from politics, administration, planning, civil society, and stakeholder networks were interviewed. The data was collected with semi-structured expert interviews. The interviews investigated the actors' estimations of the region's innovation environment and the progress of the network itself. However, the core team of the network was not interviewed because another researcher team was responsible for the internal evaluation and because the authors of this article were themselves members of the core team. However, the reflections on the institutionalization process of the “Region 4.0” have been incorporated into the analysis based on another publication (Nagy et al., 2023).

In the second phase, between 2021 and 2022, a qualitative comparative case study was conducted in other regions in Germany to learn from already successfully institutionalized collaborative governance networks for regional development. Three regions with an exemplary governance network were identified and analyzed for the study according to following general criteria:

Most similar design:

1. The case regions are rural and peripheral regions (classification according to Thünen-Landatlas, 2022).

2. Ideally manifest a similar economic structure to “Region 4.0.”

Different in outcome:

1. There is an established, innovative and independent regional development agency that is taken here as an operationalization of the concept of collaborative governance.

2. The region is known for (socially) innovative development trajectories.

Based on the criteria mentioned above, the following comparative case studies have been chosen for comparison to the “Region 4.0”: Rhineland-Palatinate, Western Schleswig-Holstein and South Westphalia.

We conducted an average of five semi-structured expert interviews in each region in addition to the interviews in the initial region. We have also analyzed the major strategic plans and evaluation documents of the regional agencies. The interviewed stakeholders were chosen as follows: The first set of the interviews covered the internal perspective of the agencies. We interviewed the coordinator of each agency and one or two representatives of the founding members (State Ministry and the University of Kaiserslautern in Rhineland-Palatinate and representatives of the member municipalities in Western Schleswig-Holstein and in South Westphalia). We also interviewed the key funders or economic development partners (Ministry of Finance and Chamber of Commerce in Schleswig-Holstein, State Ministry representative for the REGIONALE-program in South Westphalia). The aim was to gain insights into how the participatory governance network for regional development was established. Secondly, we interviewed experts from other collective actors, such as associations and regional networks, who have been driving forward socially innovative developments in the region independently of the agency. The aim of these interviews was to reflect the agency's role in the region from an external perspective in order to understand its success and limitations. The interview structure included questions on the emergence process and main founding stakeholders of the agencies, the estimation on the role of the agency in the regional development, good practices and challenges in cooperation, existing collaborative relations and goals of development work as well as on the estimation of the influence of the regional characteristics to the work of the agency. In order to conduct the final analysis, the five most representative interviews from the total of 25 interviews from the initial investigative region were included in order to ensure a comparison between the initial and the three comparative regions. The final data set consisted of 21 interviews.

The interviews were analyzed relying on a coding method combining deductive and inductive thematic coding (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006; Guest et al., 2012). According to the deductive coding, the first set of codes was developed based on the theory and research questions in order to focus the analysis on the main comparative aspects. Secondly, all material was coded under the “first-level theoretical codes” that remained the same during the coding process, but subcodes were added and adjusted inductively as they emerged from the material. After the initial case was completely coded for the first time, the authors compared their coding procedure and systematized the coding process for the further interviews. If a researcher was uncertain about the appropriate code, only first-level codes were used.

4. Results

We analyze each case study as follows: the regional context, the emergence and structure of the regional development agency, the successes and challenges of the agency and its relationship to further innovative developments in the region.

4.1. The “Region 4.0”: North-East Brandenburg (Barnim-Uckermark)

The “Region 4.0” encompasses the districts of Barnim and Uckermark in the north-eastern part of the state of Brandenburg, located between the metropoles of Szczecin and Berlin. It can be characterized as a natural and touristic area, and it is rural and peripheral both in socioeconomic and geographical terms (Thünen-Landatlas, 2022). Due to the lack of industries, except for the towns of Schwedt and Eberswalde (R402), the regional economic structure is dominated by small enterprises (R401, R405). The exodus of adolescents from the region's urban and local centers since German reunification has enhanced peripheralization (R402). Only in recent years, however, has the demographic development consolidated near the urban centers bordering Berlin, along train lines (R402) and around Szczecin thanks to the in-migration from Poland (Regionale Planungsgemeinschaft Uckermark-Barnim, 2019; R402). Nature tourism and agriculture are major economic activities in the region, and social and ecological entrepreneurship is fairly common compared to the rest of Brandenburg (Jahnke and Spiri, 2021; Thünen-Landatlas, 2022).

The promotion of economic development and innovation has traditionally been conducted at the level of the municipalities and the two districts: While economic development falls into the responsibility of the business development agencies of the municipalities, towns and districts, rural development is conducted within the LEADER regions, which are congruent with territorial district demarcations (Schäfer et al., 2021; Büchner and Franzke, 2022). Cross-district cooperation between Barnim and Uckermark has been conducted in a few other fields, such as regional planning (R401).

The research and development (R&D) network “Region 4.0” emerged, as mentioned previously, through the funding program from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The founding actors within the network were academic institutions and a business development agency. The innovation strategy and project ideas were developed via participatory workshops in collaboration with diverse local actors across the districts during the first years. The strategic goal of the network was defined as the promotion of a participatory economy based on a regional identity via SIs. Thus, in comparison with the other agencies, SI, ethical goals and embedding them into the actual needs of the local residents and producers were at the center of the strategy. The fields of action of the alliance were defined as agriculture and nutrition, infrastructure and public services, and nature-based tourism. The coordination of the new network was assumed by an innovation management team from a regional university, whose task was to initiate and synergize different R&D projects and institutionalize an SI promotion agency beyond the initial three-year funding period.

The interviewees who were engaged in setting up the network considered its early co-creation processes and participatory strategy development in 2019 and the cross-border approach across territorial boundaries as successful (R401, R403). The funding and strategy processes were considered to be unique in their approach of combining actors across sectors, from central towns and rural villages. Long-term effects are somewhat uncertain as the network is still in a rather early stage of its development. The reflection on the basis of the development work of the authors confirm, however, that local enterprises, such as public canteens, meat producers or a local bus company, have found a perspective for new, sustainable value chains or a multifunctional usage of public buses through the projects of the network. Finally, a perspective for the institutionalization of the whole network is emerging through collaboration with the regional university, a local municipality and two activists (self-employed), who continue running the network within a planned advisory center for sustainable regional economies (Nagy et al., 2023).

The main challenges of institutionalizing the network has been in rooting the academia-led network in the regional institutions. Firstly, this was manifested in the critique by the interviewees on the strong research-focus of the funding that did not meet the expectations of the regional institutions, such as public administration and LEADER groups (R401, R403). The two interviewees who were initially mostly engaged were strongly disappointed that their ideas were eventually “too practical” to be funded as an R&D project. Secondly, the local authorities continued to focus and invest on their own, parallel innovation support structures without considering the “Region 4.0” network as a joint representative of all innovation efforts in the region. The district of Uckermark ran a regional budget of its own with the funding program “improvement of the regional economic structure” (GRW; R401, R402), which also gave the founding impulse for the “Regional Cooperation Westcoast” (see below). But other than in Westcoast, the GRW funding in Uckermark was implemented within one district only. Thus, the regional public institutions seem to consider themselves and their own districts as the main agents of the development instead of attempting to collaborate across the borders (R402). No motivation by the district to continue financing for cross-regional initiatives beyond project funding emerged either for the district's own innovation support (regional budget within the GRW) or for “Region 4.0” (R401). This was enhanced by the strong industrial focus of the economic development organization to the extent that they did not see enough value in collaborating with the nonindustrial regions, which make up the majority of their geographic neighbors (R402). Finally, inter-municipal planning that has been a starting point for the collaboration in Westcoast and South Westphalia is also underdeveloped in the industrial city of Schwedt (R402), and the good experiences of the collaboration within the Berlin metropolitan region have not yet been adequately spread to this city in the north of “Region 4.0” (R404).

In addition to “Region 4.0,” other socially innovative developments are taking place in the region. One example is the Network Future Places (Netzwerk “Zukunftsorte“), to which one of the new, local managers of “Region 4.0” also belongs. These places are developed mostly by freelancers and creative workers from Berlin increasingly moving to Brandenburg and creating new spaces for collaborative working and living. They are becoming visible to the public and networking with each other through the Network Future Places:

“There are people in several places who are involved locally, who have either been there for a long time or who have just moved there. […]. And they are often really hard to find. But I think there are such places in almost every village or district. And making them visible and networking them is the big task. And we as the Network of Future Places want to support the establishment of such future places, because, of course, they have big hurdles and problems, where all places actually have their own experiences, but share them too little, because there is simply no format and no forum for it. And that's what we want to offer. […] Looking to the north. There are, of course, an incredible number of places that are emerging.

To summarize, “Region 4.0” succeeded in generating its strategy-building process as a momentum of collaborative governance for SI promotion, from which some concrete, sustainable solutions for providing livelihoods and infrastructures have emerged. However, the momentum has not yet been enough in the first few years to convince especially the institutionalized public and economic actors of the relevance of this focus on social and ecological rather than technologically driven development. This relates partly to their disappointment of the public and economic actors in the initial funding system. The successive institutionalization of the network through local practitioners may help to close this gap between research and local institutions and engage further bottom-up networks, such as the “Network Future Places,” so far operating separately.

4.2. Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate is a federal state in Germany with a comparatively small-scale structure (RLP1). It has only a few major towns, while most of the people live in small towns and the 2,300 municipalities, and commute to the cities to work (RLP1). The leadership in the municipalities is typically based on voluntary commitment, which, according to the leader of the agency (RLP1), generally enhances the local voluntary engagement in the rural areas. The towns are, however, relatively wealthy (RLP1) and the region has an average socioeconomic standard (Thünen-Landatlas, 2022). The districts at the western border of the federal state especially benefit from their good connections to the highly developed metropolitan region of Rhine-Neckar (RLP3).

The “Development Agency Rhineland-Palatinate” (Entwicklungsagentur Rheinland-Pfalz) is a long-term institution established by the Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry of the Interior and for Sport and the Technical University of Kaiserslautern in 2003. The initiative to create the agency came from the federal state and its aim was to apply a scientific approach toward regional development and to find a new partner within the ministry to support the municipalities (RLP3). It can, therefore, be considered as an academic-political collaboration, and its members work in academia, administration, regional and local politics, and formal spatial planning. In addition, the agency collaborates with partners from private business and civil society (RLP1) and with neighboring districts, such as the ones in the federal state of Saarland. The development agency deals with the effects of societal, technological or economic transition in municipalities and aims at developing innovative and practical solutions for municipalities collaboratively. The Development Agency Rhineland-Palatinate has been institutionalized by the federal state with a stable base funding in the long term after some years of provisional and short-term funding (RLP1).

Its initial founding idea was to find an institution that could deal with the conversion of former military grounds for a new purpose (RLP1) and who could also gather and rely on experiences and best practices from other regions (RLP1). After these first tasks, new areas of responsibilities for the agency emerged, such as the promotion of regional development, digitalization and co-working in rural areas (RLP1, RLP2). One innovative program “Village Office” (Dorfbüro) emerged out of an encounter between the agency and a local mayor interested in experimenting with rural co-working (RLP2). Due to the fact that a large number of residents in Rhineland-Palatinate commute from villages to work in the cities, there is plenty of potential interest in rural co-working spaces (RLP1). The model became successful, therefore, the Ministry of the Interior and for Sport institutionalized the experiment by providing the agency with funding for further rural co-working spaces (RLP1, RLP2). The Village Office funding program can be grasped as an SI as the model diffused to other regions in Germany and some districts in Luxembourg and Belgium (RLP1, RLP2).

The first challenge identified by the actors themselves considers the strong power position of the founding ministry over the agency in its starting phase. According to one interviewee, the agency was in the beginning not actually able to implement the military land use conversion objectively, based on scientific information and evaluation, as planned. Instead, the coordinating ministry practically organized the investment agreements on the land based on private networks, thus, avoiding real delegation (RLP3). Secondly, due to the predominantly volunteer-based leadership, administration in small municipalities is often lacking resources and professionals to foster innovative development, and focuses, instead, on the most necessary tasks (RLP1).

In addition to the agency, there are also other attempts to institutionalize innovative rural development in a cross-actor and -regional manner. A regional agency was started by local politicians and institutions within the federal funding program “Land(auf)Schwung” in the district of Neunkirchen in the neighboring federal state of Saarland in 2018, in an attempt to consolidate project-based rural development. The regional agency was coordinated and run by an academic partner from Rhineland-Palatinate, the Institute for Applied Material Flow Management (IfaS) from the university campus in Birkenfeld (RLP3). The contents and projects of the agency were attuned to socially innovative regional development, such as small-scale and locally owned renewable energy production, local circular economy solutions based on the recycling of materials, and local identity as a “welcoming region,” also signaling global responsibility (RLP4). However, toward the end of the program, the political will to secure the long-term funding could not be guaranteed and the agency was not institutionalized. No responsible level for cross-cutting development issues existed and the district has no legitimacy to delegate any budget for regional development (RLP4). Even though a similar program was run in the district across the border in Rheinland-Pfalz, the districts could not overcome the history of diverging political leadership trajectories and economic structures, and not enough common interest to cooperate was found. Additionally, funding regulations would not have allowed cooperation across agencies and boundaries of the region (RLP4).

In summary, the agency in Rheinland-Pfalz has been founded and institutionalized as “an extended arm” of the ministry (RLP4), but by time it has managed to develop its own profile with some specific, successful projects for the targeted needs of the municipalities. However, perhaps because the themes of collaborative governance arise strongly from the pragmatic needs of the municipalities, they neither address grassroots networks with radical and holistic sustainability agendas nor does the agency follow such agenda in its own projects. Another attempt of a university-led development program whose projects were more strongly working toward a social innovation ecosystem, did not manage to convince the public institutions of its relevance.

4.3. Western Schleswig-Holstein

The region of Western Schleswig-Holstein refers to the districts of Nordfriesland, Dithmarschen, Pinneberg and Steinburg on the north-western coast of Germany. The three southern districts of the region already belong to the Hamburg metropolitan region. The south-western part of the region has a relative abundance of research and higher education institutions and hidden champions (Projektgesellschaft Norderelbe, 2019, p. 38), as well as a relatively large number of employees in knowledge-based industries (Thünen-Landatlas, 2022). The northern parts, in turn, are strongly agricultural and have respectively fewer knowledge-based industries and no research organizations. Renewable energy production both industrially on regional level and through locally owned energy cooperatives has become a major economic field (WK5, WK7), bringing remarkable revenues to the rural and peripheral areas (WK7).

“Regional Cooperation Westcoast” (Regionale Kooperation Westküste) was initiated as a collaboration between the four districts and two regional economic development organizations. Similar to Rhineland-Palatinate, the founding impulse came from the federal ministry but, in the case of Westcoast, in the form of a federal development plan, which envisioned a development axis cross-cutting the four districts. Three of the four districts had already been working together in the metropolitan region of Hamburg and founded a joint project development company. Thanks to the active funding and initiative of the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, a new cooperation was now extended to the northernmost district on the coast, and the existing project development company formed the organizational basis for the new agency (WK1, WK3, Projektgesellschaft Norderelbe, 2019). The district administrations and economic development institutions designed a regional development strategy to be implemented by the agency. Funding was guaranteed through the GRW, a joint funding program with the state and the federal government, which has reached its final funding period on the West Coast at the end of 2022. The funding provides the agency with a regional budget for innovative projects of public institutions.

At first, the cooperation focused strongly on lobbying for mobility projects and a new motorway to be built, which was planned as a cross-cutting mobility corridor as a part of the development axis (WK1, WK3). However, according to the representative of one of the founding districts (WK2), the building of the motorway received increasing criticism, especially from the leading green party in the state government, which encouraged the districts to broaden their topics of collaboration. Thus, building the value chain for renewable energy, including the development of the storing and marketing of the municipal decentralized energy produced already and of the related electro-mobility infrastructure, emerged as the common focus and, finally, as a successful profile of the whole region (WK3, WK4, WK5).

All internal partners interviewed evaluated the cooperation as functional and successful (WK1, WK2, WK3, WK4). The interviewees claimed that an independent agency supports the transparency and knowledge flow between the partners and reduces negotiations about coordinating structures for new initiatives, thus, making inter-municipal collaboration smooth and efficient (WK3). It also ensures resources for coordination and networking, which the districts alone are usually not ready to provide (WK3). Finally, it allows the districts to forward their specific interests together under joint goals (WK4). This is highlighted by the citation below from the interview with one of the partner districts:

Every regional planner has participated in a cooperation between the districts, where one of the partners has decided “Ok, I will take the lead.” It has always been shown that it doesn't work that way; when one district leads, there are partial interests, staff changes, the topic loses interest and after a couple of years, nobody cares two hoots. That's why we decided that we needed a central project coordination that pushes things forward when needed, organizes meetings, etc. (WK2)

Thanks to the cooperation, a new R&D collaboration and a strong regional image across the public and private sector around renewable energy production and infrastructure has emerged (WK1, WK3). Projects that either implement cross-border infrastructure (e.g., a quick e-car loading station network) or assist the districts to reasonably plan the use of common, limited resources (e.g., an inter-municipal industrial area monitoring tool) were named successful according to many.

However, the collaboration remains to be mostly driven by the southern districts, and the commitment of the northernmost district with the strongest geographical differences to the southern parts was not seen as intensive as it could be (WK2). Furthermore, the collaboration remains focused on “soft” topics in which competition and conflicts are unlikely (WK2). The praised industrial area monitoring tool, for example, functions as a source for information, but no binding negotiations or agreements about land use between the districts have been met on this basis.

We don't conduct regional planning, only prepare it. […] If it's clear at the beginning that it's difficult to find a consensus, we would rather leave it be, and work with other topics […] yes, we have made a forecast, including regional differences, on where the industries should settle down in the future, but we haven't spoken about any recommendations […]. On the other hand, I would say we dodge the responsibility and avoid difficult topics. (WK2)

Finally, ensuring a future perspective for the cooperation requires the financial commitment of the districts. According to the representative from the state ministry, the elected politicians may, at times, find the results too abstract to support the further funding of the agency (WK4).

Other than in the “Region 4.0,” the “Regional Cooperation Westcoast” remains mainly unattached from SI promotions, such as the development of local basic services, village-based and citizen initiatives, and regional agriculture. The agency considers that local sustainable development should be initiated mostly at the municipal level, whereas their focus lies on inter-municipal collaboration and projects on a larger scale. Sustainability, as such, is one of the cross-cutting themes especially brought forward by the northernmost district of Nordfriesland (WK1). The agency might, however, support the spreading of local SIs across the member districts by, for example, bringing climate change managers of the municipalities and the public procurement officials together. Apart from the agency, there are, indeed, several local social innovative initiatives and networks, such as the partly volunteer-run village-based e-car-share model (“Dörpsmobil”), which has spread from one municipality all over the state in collaboration with LEADER groups and state ministries. Another self-organized network of local tourism and agricultural enterprises (“Feinheimisch”) is developing a marketing platform and value chain between local producers and tourism enterprises. These examples are actually much closer to the SI projects driven by “Region 4.0,” for example, but in western Schleswig-Holstein, they are not considered as relevant for cross-border regional development; neither of these actors are aware of “Regional Kooperation Westcoast” nor consider it as a possible partner. Thus, it can be summarized that changing and learning new practices of inter-municipal collaboration seem to be fairly advanced in western Schleswig-Holstein, fostering post-fossil transformation via technology- and capital-driven large-scale developments. The RDA in question does not object to holistic SI development on the local scale, but does not actively support it either.

4.4. South Westphalia

South Westphalia, the “industrial region in nature” (SWF2), consists of five districts in the rural, southern part of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Thanks to the more than 150 world market-leading companies mostly in the automotive industry, South Westphalia counts as one of the three strongest industrial regions in Germany and as a rural area with one of the highest gross domestic products in the country (Thünen-Landatlas, 2022). It lacks major cities but is adjacent to the metropolitan region of Cologne. The population of the region is generally shrinking, but the pace has slowed down, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Thünen-Landatlas, 2022; SWF2).

The founding of the “South Westphalia Agency” (Südwestfalen Agentur) was strongly driven by a collaboration between five neighboring districts on a joint tourism marketing strategy (SWF2). When the “Regionale” program of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia was announced, the districts applied, received funding and founded a new agency as a limited liability company to implement the program. Whereas the GRW funding used by Uckermark and Westcoast is available for all states in Germany, the “Regionale” is developed and managed only in North Rhine-Westphalia. Other than in GRW projects, not only districts but any organization, such as enterprises and associations, can plan and apply for projects. No specific budget is available, but those projects that pass three high-threshold application rounds will receive a commitment for funding from the existing budgets of the respective ministries (SWF3, SWF4). The districts of the “South Westphalia Agency” also founded a regional marketing association, “Economy for South Westphalia,” as one shareholder of the agency beside to the districts. Meanwhile, over 300 enterprises of the region are members of the association, thus, providing funding for the agency and its regional marketing activities.

Because of the fact that the “Regionale” had already been implemented six times before the one in South Westphalia, there are means to compare which regional collaborations are successful and on which basis. One success factor that applies to South Westphalia is the sound establishment of the agency as a long-term institution with tasks reaching beyond the “Regionale” program (SWF1, SWF2). This ensures continuous financial commitment of the districts and the funding generated from the companies via regional marketing. Furthermore, all participants interviewed knew and praised the agency as a networker and representative in and for the region. Other than in Westcoast, this was also confirmed by those external actors who otherwise did not consider the agency and its program as a driver for their own initiatives (SWF4, SWF5). Furthermore, the core partners of the agency confirmed (SWF1, SWF2, SWF3) that the actors in the new structures need to recognize and collaborate with existing institutions, such as economic development organizations, in order to avoid considering the new “Regionale” as concurrent. Such a program supports cross-border learning not only at a regional level but even in the ministries, because many successful projects do not clearly fit under one specific resort, but require collaboration across the ministries for designing suitable funding. Finally, due to the longer experience with collaborative regional development, a representative of the state ministry recognizes that difficult topics are not avoided in the same sense as was claimed in Westcoast.

The claim that “Regionale” only enters into positive cooperation and shies away from conflictual issues must be countered by the fact that this is only a learning process. We see an increasing diversity in the topics discussed, also those that are very hands-on. For example, the topic of resource use. […] Regional planning tends to do this on a two-dimensional level of defining areas […] but in the question of implementation, how ow to deal with floods in the existing built areas,regional planning simply has no instruments. That is much easier in a “Regionale” program […] to learn together and also agree upon rules together. (SWF3)

Going through the funding may be a complicated and lengthy process for the project managers, because they need to convince sometimes several different ministries that the project is worthwhile not only at a regional level but from the perspective of the whole federal state (SWF3). However, the partners did not identify any major challenges in the establishment process of the agency.

The “South Westphalia Agency” has its strongest focus on economic development, regional marketing and youth as potential employees in the region. Especially through its project “Utopia Südwestfalen” co-organized by several youth organizations, the agency is in dialogue with broader themes and civic groups such as “Fridays for Future.” Therefore, it is also more active in its public outreach in comparison to Westcoast (WK1). Nevertheless, the “Regionale” program is not necessarily suitable for developing local SIs or challenging existing administrative structures from outside the institutions. The latter process is driven in the state-wide campaign of “Regional Movement” (“Regionalbewegung”), for example, who attempt to design a political framework for building up regional agricultural value chains. The “South Westphalia Agency” supports the initiative and helps them in networking but does not fund or drive it forward. According to the representative, the agency does not do the same “political” work as civic movements do (WK5). Additionally, the discourse of all participants of the agency was strongly focused on supporting the region's strong industry, and the question of its adaptation to the current global challenges of a diminishing resource base and risks of global delivery chains were not addressed prominently. Therefore, in this case as well, the establishing and functioning of the agency in the long term can be seen as a successful example of collaborative regional governance. However, similar to Westcoast, the topics of possible consent brought up by public and economic actors remain mostly within the classic economic paradigm and largely ignorant of bottom-up, socially innovative, grassroots networks. However, perhaps due to the stronger participatory spirit of the “Regionale” program compared to the GRW that was used in Westcoast, initial collaboration and mutual recognition between the agency and bottom-up actors exist already.

5. Discussion

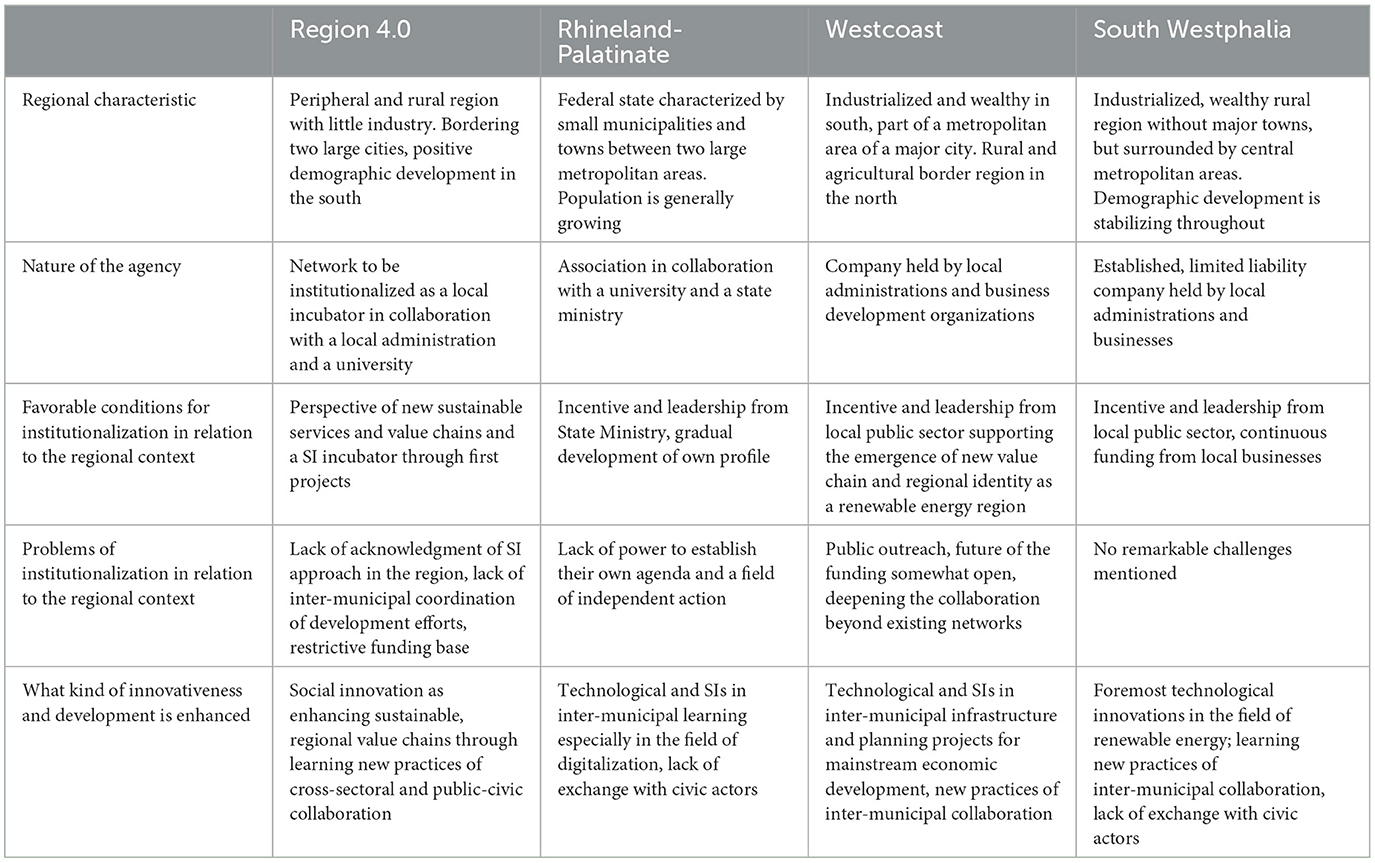

In the following, we discuss the results, firstly, concerning the institutionalization of the RDAs and, secondly, regarding their relationship to SI ecosystems and the type of development they pursue. We finish by reflecting on the results from the perspective of “organizationally thin” regions. At first, the main results are summarized in the Table 1.

The “drivers” and “system contexts” identified by Emerson and Nabatchi (2015) help to explain a major part of the emergence and institutionalization of the cases. However, the study sheds light on the specialties of collaborative governance emerging as a regional concern, and especially on the possible mutual exclusion or support in the interactions between public-initiated collaborative governance and grassroots-based SI networks. In summary, we can conclude that our results underline the advantages that enhancing socially innovative collaborative governance constellations bear for structurally weak regions. They also explicate the ways in which the successes of publicly-initiated collaborative governance constellations are embedded in path-dependencies of the regions' growing economies and in the mainstream development discourses.

5.1. Conditions of institutionalization in relation to regional context

Firstly, uncertainty was most prominent in Rhineland-Palatinate and in “Region 4.0,” where societal transformations with uncertain outcomes and responsibilities, such as the conversion of former military lands and ecological transformation of value chains and infrastructures, require a multi-actor approach. In the cases of South Westphalia and Westcoast, however, recognizing the interdependencies between the parties was mentioned much more as a mobilizer and supporter of the institutionalization of collaboration. Regional collaboration was recognized in both regions as a lobby power, which helps to convey the existing strengths and relevance of the regions to upper scales of state power and a campaign for common interests, such as the planned highway in Westcoast. Even though multi-scalar challenges are also mentioned in these regions as ideas for new projects, the success-story of a collaboration as “the DNA of the region” run through the interviews and communication material in South Westphalia (Südwestfalen Agentur GmbH, 2016; Ministerium für Heimat, Kommunales, Bau und Gleichstellung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2021). Perhaps in South Westphalia, this relates, on the one hand, to the fact that the “Regionale” funding and the agency are already institutionalized and acknowledged as a successful solution, wiping out the uncertainties that most likely were stronger at the beginning. On the other hand, it may also relate to a self-confidence in the communication of an industrially and economically strong region, which succeeds in externalizing the majority of the risks of its production to other regions.

However, it was important for a successful institutionalization to limit the extent of joint themes to those that were easily agreeable for all. The founding of an independent agency has been acting as a minimal common nominator for the partners in all cases to drive joint themes, while leaving plenty of space to keep other topics for themselves. The creation and promotion of new regional identities based on the collaborative regional constellations that did not exist before, has been one means to positively sustain interdependency and joint motivation in South Westphalia and Western Schleswig-Holstein, despite the disparities that the identities bridge.

Secondly, consequential incentives from the federal state and national level have clearly supported the emergence and stabilization of the three RDAs compared. Buchholz (2006, p. 9) has identified these incentives as central in the founding of other collaborative regional governance institutions in Germany as well. In all cases established, both funding and new policy collaboration instruments on the federal state level enhanced the institutionalization and broadening of the previous collaborations. However, the municipalities only in South Westphalia, where the initiating leadership came from the municipalities themselves and not from the federal state, are committed to continue the funding of the agency regardless of the support from the state. The agency in Rhineland-Palatinate was both initiated and continues to be funded via the founding ministry. The Westcoast still needs to finally convince the municipalities of its relevance. Nevertheless, the economic wealth of the local companies and the districts themselves provides the economic basis for the agencies especially in South Westphalia but also in Western Schleswig-Holstein (see Table 1 for a summary).

“Region 4.0” can profit neither from a similar enterprise base nor from well-off communal and state-level budgets and has, so far, been reliant on a relatively low funding budget limited to the two years remaining. This status goes together with the initiating leadership that, in this case, came from universities and individual local companies who have had challenges in convincing the institutionalized public actors of their long-term relevance for the whole region.

Finally, one aspect of the system context according to Emerson and Nabatchi (2015, p. 41), which affects the emergence and institutionalization of collaborative governance, is of special relevance here. The existing networks of cross-regional collaboration of the founding members seem to create a power relationship that persists even when the agencies institutionalize. The founding of the agencies in all cases helped to find a common ground beyond these regional disparities, but have not completely removed them. The informal institutions in Western Schleswig-Holstein and South Westphalia that preceded the agencies have continued to carry and define the formalized collaboration, so that in Westcoast, the district that is the last member in the collaboration and whose nonindustrialized economic structure differs the strongest from the rest, is also clearly less active in collaboration. Alternatively, the strongest founding initiative in Rhineland-Palatinate came from the federal ministry, and the newly created agency was, in reality, not used for democratizing the decision of the use of previous military lands, as was the plan, because the knowledge of and decisions regarding the investment plans remained intransparent on the hands of one minister.

Following the analysis framework on power relations in collaborative governance by Purdy (2012), the founding members in the established collaborative governance constellations seem powerful in all aspects: they have access to financial resources to sustain collaboration, they hold formal power to design the collaboration framework and discursive legitimacy to define the aims and legitimate participants. The alternative and grassroots networks, to which the “Region 4.0.” somewhat counts, do not actively challenge this but rather establish their own, parallel institutions. In the light of the latest large-scale developments, this perhaps turns out to be a more fruitful choice for the “Region 4.0” than confronting the existing institutions and thereby risking future collaboration. On the course of the war against Ukraine the regional, oil-based industry in North-Eastern Brandenburg now faces a major pressure to rapidly decarbonize, which all of a sudden elevates the legitimacy of the “Region 4.0” greatly and respectively questions the discursive position of the fossil industry so far.

Therefore, in the case of collaborative regional development, founding an independent agency not driven by individual communities as an administrative task was considered elementary. It not only increases the efficiency, continuity and legitimacy of the collaboration but may provide a more neutral platform beyond individual districts and organizations for gradually diversifying the participation networks and overcoming established power relationships.

5.2. What kind of development for whom?

The results show barely any convergence between bottom-up SI ecosystems and collaborative regional governance. The model of the “regional development agency” is used for public-driven inter-municipal collaboration and, although it is framed by the actors themselves as the neutral representative of the region, its central focus lies on classical economic development. The actors claim that they are promoting social innovativeness in their collaboration, but here the discourse has rather been adapted to the economic agenda of the institutions instead of the institutions changing their approach while applying SI discourse (see Table 1). Thus, the main actors for whom the development is done are the local enterprises in competitive industries, employers and employees.

In parallel, there are networks of small and medium-sized enterprises and civic activists in all regions driving transformative local SIs (Bock, 2012; Galego et al., 2022), which support more-than-capitalist production and engagement and partly also challenge the public sector to change their regulations in favor of local, ecologically and socially sustainable production. The examples show that publicly driven efforts of collaborative governance seem to remain true to their development trajectories oriented toward the hegemonic and growth-oriented models instead of recognizing the value of alternative production already taking place in peripheries (Rover et al., 2016). Due to the partly antagonistic roles of civil society as the critique of institutionalized power, and public institutions as the arenas of deliberative solutions, it is perhaps also necessary that both kinds of initiatives and networks exist in parallel, with their complementary roles and ways of work.

However, mutual benefit and learning may increase if public collaborative governance actors are ready to provide spaces and support for more informal and critical actors. The strong orientation of the network of the “Region 4.0,” for example, regarding the small-scale, local and nonindustrial producers has given the entrepreneurs in these sectors the first opportunity to access R&D funding with close support from the universities.

Regarding the public bodies, the major benefit from collaborative governance networks is to find a neutral forum in which to learn to overcome competition mentality. It seems, at least in South Westphalia and Western Schleswig-Holstein, that even though the inter-municipal collaboration starts from “easy” topics, in time, more conflictual themes, especially the common use of shared land and limited resources, are also taken up. However, as the majority of the success examples still represent the soft topics, where mutual benefit is easy to identify, it remains open, how fast this learning process actually incorporates the necessity to agree upon the reduction of harmful industry and traffic. So far, lobbying for one's own region's industry and accessibility, regardless of its ecological footprint, has been more central in each agency's agenda.

5.3. Lessons learnt for “organizationally thin” regions

The empiric study also supports the notion of Zukauskaite et al. (2017) that the creation of new organizations does not explain the region's innovativeness if informal institutions of collaboration are not developed as well. In the case of Rhineland-Palatinate, it took the first ten years of the agency until it had strengthened its own networks and developed a topic in which it was able to independently build up and spread new solutions. Similarly, the same impulse (GRW funding) in two different regions has helped to create a lasting knowledge-exchange organization and informal institutions only in Western Schleswig-Holstein, where it stemmed from already existing informal collaboration. Furthermore, even though universities are among the central knowledge organizations in all regions (Pugh et al., 2016), their presence is not necessarily good per se but depends on whether mutual interests for knowledge-exchange are found. In “Region 4.0,” the authors' reflection of their development of the network confirm, that the only regional university as the main initiator of the network is not really acknowledged as an adequate knowledge partner by the economic development organizations. That relates to the university's focus on local sustainable economies, whereas the economic development partners prioritize a knowledge-transfer with a technological and industrial focus.

Furthermore, the results highlight the limitations of the classical economic understanding of “organizational thinness,” especially in rural and peripheral regions. All public-founded regional innovation agencies focused on supporting technological and scientific knowledge-exchange and world-market leading companies, thus, blending out numerous other civic and professional networks, which might help to spread knowledge and create collaboration between locally-based small and medium-sized enterprises and activists on new and sustainable livelihood models. These collaborations, such as the “Feinheimisch” network, “Dörpsmobil” model, and “Regionalbewegung,” do not manifest as a radical innovation of a major industry throughout the whole region, but rather as streams of parallel and incremental changes in the primary, public, service and local manufacturing sectors. The driving nodes of these networks are nationally and internationally highly connected, bypassing the organizational thinness of their region with their own grassroots institutions. The institutionalization of the network “Region 4.0” builds on such collaborations as well, working in parallel to instead in collaboration with the public industrial development efforts. Based on their reflection on the development work of “Region 4.0” the authors can confirm, that the narrow definition of organizational thinness, especially in the economic geographic literature, does not grasp the diversity of the economic and innovative potential in the region. Therefore, the common definition of organizational thinness can be seen as an example of capitalocentrism, where all economic activities working beyond the growth norm are ignored or considered marginal and irrelevant (Gibson-Graham, 2006). Actually, such more-than-capitalist economies strongly enhance the knowledge-exchange and help to diversify local livelihoods with the fraction of investments and ecological footprint that the construction of typical knowledge-organizations, such as science parks, usually does. However, mutual recognition and opportunities for enhancing both grassroots-based and publicly driven transformation were sprouting in all empiric cases.

Therefore, managerial implications based on the lessons learnt would be to

- Strengthen the role of universities in organizationally thin regions, especially with regard to the often-neglected aspect of promoting SIs,

- Supporting small and medium-sized enterprises as well as civil society actors and grassroots institutions and to

- Overcome an exclusive focus on technological and capital-intensive solutions in favor of small-scale collaborative forms of support for SIs.

Due to the fact that we only undertook four regional case studies the empirical significance remains limited. Further research would be required to illuminate in greater detail the aspects of collaborative regional governance for SI promotion in institutionally thin regions. It would be especially fruitful to conduct some future research in different nation states in order to compare them with our results from the German cases. Another desideratum concerns the aspect of power; this would require discussing our findings in light of the literature on power issues in collaborative governance (Purdy, 2012; Ran and Qi, 2018).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request, without undue reservation and excluding the data that cannot be sufficiently anonymized.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The research was funded by the project WIR!—Regionalisierung 4.0—Verbundprojekt: Weiterentwicklung der Innovationsstrategie; TP2: Innovationsumfeld und Governance (grant no. 03WIR0803C) of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the interviewees for their time and valuable information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Avelino, F., Dumitru, A., Cipolla, C., Kunze, I., and Wittmayer, J. (2020). Translocal empowerment in transformative social innovation networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 28, 955–977. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1578339

Beer, A., and Lester, L. (2015). Institutional thickness and institutional effectiveness: developing regional indices for policy and practice in Australia. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2, 205–228. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2015.1013150

Bellini, N., Danson, M., and Halkier, H., (eds) (2012). Regional Development Agencies: The Next Generation? Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203107027

Benz, A. (2021). Policy Change and Innovation in Multilevel Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.4337/9781788119177

Benz, A., and Fürst, D. (2003). “Region – ≫Regional Governance≪ – Regionalentwicklung,” in Regionen Erfolgreich Steuern: Regional Governance – von der Kommunalen zur Regionalen Strategie, eds B. Adamaschek, and M. Pröhl (Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann-Stiftung), 11–66.

Blatter, J. (2005). Metropolitan Governance in Deutschland: normative, utilitaristische, kommunikative und dramaturgische Steuerungsansätze. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 11, 119–155. doi: 10.1002/j.1662-6370.2005.tb00050.x

Bock, B. (2012). Social innovation and sustainability; how to disentangle the buzzword and its application in the field of agriculture and rural development. Stud. Agric. Econ. 114, 57–63. doi: 10.7896/j.1209

Brenner, N. (2004). New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. (Oxford New York: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199270057.001.0001

Buchholz, F. (2006). Kooperative Regionalentwicklung durch Regionalmanagement? Eine Analyse am Beispiel der Regionen Chemnitz-Zwickau, Magdeburg und Braunschweig. Berlin: IÖW.

Büchner, C., and Franzke, J. (2022). “Der landkreis barnim in der bundesrepublik”, in Festschrift für Dr. Christiane Büchner in Würdigung ihres Wirkens am Kommunalwissenschaftlichen Institut (1994–2022), ed J. Frankzke (Potsdam: KWI Schriften), 87–123.

Castro-Arce, K., and Vanclay, F. (2020). Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: an analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J. Rural Stud. 74, 45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.11.010

Cristofoli, D., Douglas, S., Torfing, J., and Trivellato, B. (2022). Having it all: can collaborative governance be both legitimate and accountable? Public Manag. Rev. 24, 704–728. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2021.1960736

Dax, T., and Fischer, M. (2018). An alternative policy approach to rural development in regions facing population decline. Eur. Plan. Stud. 26, 297–315. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1361596

Dehne, P. (2019). Perspektivwechsel in der regionalpolitik: daseinsvorsorge als gesellschaftliche Aufgabe. Wirtschaftsdienst 99, 56–64. doi: 10.1007/s10273-019-2433-9

Domanski, D., Howaldt, J., and Kaletka, C. (2020). A comprehensive concept of social innovation and its implications for the local context – on the growing importance of social innovation ecosystems and infrastructures. Eur. Plan. Stud. 28, 454–474. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1639397

Dupuy, C., and Defacqz, S. (2022). Citizens and the legitimacy outcomes of collaborative governance an administrative burden perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 24, 752–772. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2021.2000254

Elbe, S. (ed). (2007). Begleitforschung “Regionen Aktiv”: Synthesebericht und Handlungsempfehlungen. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen. doi: 10.17875/gup2007-260

Emerson, K., and Nabatchi, T. (2015). Collaborative Governance Regimes. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Fereday, J., and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 5, 80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107

Flåten, B.-T., Isaksen, A., and Karlsen, J. (2015). Competitive firms in thin regions in Norway: the importance of workplace learning. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 69, 102–111. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2015.1016875

Füg, F., and Ibert, O. (2019). Assembling social innovations in emergent professional communities. The case of learning region policies in Germany. Eur. Plan. Stud. 28, 541–562. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1639402

Gailing, L., and Röhring, A. (2016). Is it all about collaborative governance? Alternative ways of understanding the success of energy regions. Util. Policy 41, 237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2016.02.009

Galego, D., Moulaert, F., Brans, M., and Santinha, G. (2022). Social innovation & governance: a scoping review. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 35, 265–290. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2021.1879630

Gibbs, D. G., Jonas, A. E. G., Reimer, S., and Spooner, D. J. (2001). Governance, institutional capacity and partnerships in local economic development: theoretical issues and empirical evidence from the Humber Sub-region. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 26, 103–119. doi: 10.1111/1475-5661.00008

Guest, G., MacQueen, K., and Namey, E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781483384436

Heinelt, H. (2010). Governing Modern Societies: Towards Participatory Governance. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203856680

Heinelt, H., Egner, B., and Hlepas, N.-K. (2021). The Politics of Local Innovation. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003084006

Hölsgens, R., Lübke, S., and Hasselkuß, M. (2018). Social innovations in the German energy transition: an attempt to use the heuristics of the multi-level perspective of transitions to analyze the diffusion process of social innovations. Energy Sustain. Soc. 8, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13705-018-0150-7

Huxham, C., Vangen, S., and Eden, C. (2000). The challenge of collaborative governance. Public Manag. Int. J. Res. Theory. 2, 337–358. doi: 10.1080/14719030000000021

Isaksen, A., and Trippl, M. (2014). Regional Industrial Path Development in Different Regional Innovation Systems: A Conceptual Analysis. Papers in Innovation Studies 2014/17. Lund: Lund University, CIRCLE - Centre for Innovation Research. Availble onine at: https://www.lunduniversity.lu.se/lup/publication/cae32681-41dc-4e66-a64d-204098f502d8 (accessed March 10, 2023).

Jahnke, T., and Spiri, N. (2021). Marktorientierte Sozialunternehmen in Brandenburg. Darstellung der Existierenden Unternehmenslandschaft und Feststellung Vorhandener und Fehlender Gründungsvoraussetzungen. Potsdam: Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Energie des Landes Brandenburg.

Jessop, B. (2020). “The state: government and governance”, in Handbook of Local and Regional Development, eds A. Pike, A. Rodríguez-Pose, and J. Tomaney (London: Routledge), 239–248.

Jones, R., Moisio, S., Weckroth, M., Woods, M., Luukkonen, J., Meyer, F., and Miggelbrink, J. (2018). “Re-conceptualising territorial cohesion through the prism of spatial justice: critical perspectives on academic and policy discourses,” in Regional and Local Development in Times of Polarisation, eds T. Lang, and F. Görmar (New York/Berlin: Springer), 97–119. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-1190-1_5

Joutsenvirta, M. (2016). A practice approach to the institutionalization of economic degrowth. Ecol. Econ. 128, 23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.04.006

Kim, S. (2022). A participatory local governance approach to social innovation: a case study of Seongbuk-gu, South Korea. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 40, 201–220. doi: 10.1177/23996544211005784

Klagge, B., and Brocke, T. (2012). Decentralized electricity generation from renewable sources as a chance for local economic development: a qualitative study of two pioneer regions in Germany. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/2192-0567-2-5

Kooiman, J. (1999). Social-political governance. Public Manag. 1, 67–92. doi: 10.1080/14719037800000005