- Department of Political Science and IR, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Introduction: Although there is a considerable amount of work on the effect of catastrophes on elections, we still do not have much work on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on them. This article focuses on the case of the Madrilenian regional election of 2021, looking for the causes of the improvement of the ruling party's results, the Popular Party (PP), which went from having 22.23% of the vote share in 2019 to 44.76% in 2021, and more concretely to the role that COVID-19 had on this. This election is especially interesting for this matter because the main issue was the question of how to manage the pandemic: The right-wing parties (and mainly the PP) criticized the restrictions imposed by the central government, led by the socialist Pedro Sánchez, while the left-wing parties defended them.

Methods: The article runs separate analyses at the aggregate and individual levels. At the aggregate level, it uses municipal and district-level data with electoral and socio-demographic variables; at the individual level, it uses a post-electoral survey.

Results: There was a higher improvement in PP's results in areas with higher increase in the turnout rate, and both individual and aggregate-level data show that this improvement was also led by upper-class and young voters. However, there is no significant association with the cumulated cases of COVID-19 in the area.

Discussion: The article contributes to the understanding of the 2021 Madrilenian regional election, showing that, despite the politicization of the pandemic, there was no relationship between how hardly were the areas hit by the pandemic and the outcome of the election at the aggregated-level.

1. Introduction

The Madrid regional election held on 4 May 2021 was a victory for the Popular Party (PP) and her candidate Isabel Díaz Ayuso, president of the region, who obtained 44.76% of the votes, improving her 2019 result by more than 22 points, allowing her to form a government with a comfortable absolute majority thanks to the parliamentary support of Vox. Overall, the right-wing bloc improved its result by seven points compared to 2019.

This improvement contradicts common assumptions of retrospective economic voting, which can be summarized by the principle that, when the economy worsens, the ruling party loses votes in the elections (Costa Lobo and Lewis-Beck, 2017; Stewart and Clarke, 2017). Therefore, this election offers an interesting case study in which basic assumptions of economic voting are challenged.

The article analyzes the causes of such success, claiming that it was not due to inter-bloc transfer (from left-wing to right-wing parties) but to the recovery in 2021 of voters who voted for Ciudadanos in 2019, as well as a successful mobilization of previously abstentionist voters by the PP.

This mobilization was possible due to the high popularity of PP's candidate, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, as well as to the main issue during the campaign: the way to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and the dilemma between prioritizing the population's health and preserving economic activity, a framework that benefited the PP, who stood against the restrictions to fight the pandemic. A total of 43% of PP voters declared the main reason why they voted for the PP was its candidate, and 32% voted for its position during the pandemic (García Lupato, 2021, p. 166).

I run separate aggregate- and individual-level data to make a simple analysis of the factors that led to the improvement of PP's results compared to 2019. Individual-level data shows that the major change that made the PP improve its results was the collapse of Ciudadanos, its competitor on the center-right spectrum. Other elements that contributed to its victory were the mobilization of previously abstentionist voters, as well as young people, and citizens less politicized and interested in politics. However, at the aggregate level there was no significant relationship between how hardly an area had been hit by the pandemic and the evolution of PP's results in 2021 compared to 2019.

The article is structured as follows: First, the theoretical framework is presented; then, the context in which the election took place is detailed, the expectations are exposed, the data and method are explained, and the results are presented, on the aggregate level and on the individual level. The article ends with a discussion.

2. Theoretical framework

Retrospective economic models argue that the state of the economy influences elections' results: When the economy does well, the ruling party tends to be rewarded, and when it gets worse the ruling party tends to be punished. Therefore, retrospective voting plays a fundamental role in democratic accountability and allows replacing bad political leaders.

Since Fiorina's (1981) seminal work, many studies have assessed the effect of the economy on elections. This literature confirms the basic assumptions of such models (Duch and Stevenson, 2006; Healy and Malhotra, 2013). In times of economic crisis, it has been observed that retrospective voting plays an even stronger role, more concretely regarding its punishment function (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck, 2014; Costa Lobo and Pannico, 2020).

Along the same line, the Great Recession in Europe provided a good example of punishment to the incumbent, especially in those countries more affected by the economic crisis (Bosco and Verney, 2012; Kriesi, 2012). In the case of Spain, this mechanism also took place, with a strong punishment to the ruling socialist party in the 2011 local, regional, and general elections (Barreiro and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2012; Martín and Urquizu-Sancho, 2012). However, the crisis also affected the PP and led to the breakdown of the two-party system, with the emergence of challenging parties on both left-wing—Podemos—and right-wing spectrum—Ciudadanos (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). The reasons for this were not only economic but also due to the political context and the crisis of representation that appeared in Spain during the 2008 crisis (Bosch and Durán, 2017).

However, retrospective voting models have certain limits, like those imposed by the attribution of responsibility (Peffley, 1984). Indeed, to punish the ruling party for poor performance, voters must first blame it for the state of the economy. But this is not always an easy task, due to reasons such as external economic shocks that can affect the economy beyond the government's control, a blurred responsibility due to various levels of government (Anderson, 2008), or a reduced room to maneuver due to international engagements, such as those imposed by the European Union (Hobolt and Tilley, 2014). Well-informed voters understand that under economic constraints, their government has less room to maneuver and, therefore, economic voting is attenuated (Costa Lobo and Pannico, 2020).

While Fiorina's (1981) claims that voters do not evaluate the government based on a detailed examination of the adopted policies, some studies have analyzed the relationship between retrospective voting and policy, showing that on certain occasions there is a relationship between the punishment or the reward to the ruling party depending on concrete adopted policies (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck, 2013; Healy and Malhotra, 2013, p. 297–99).

In the case of countries with several levels of government, blame attribution can become more complicated due to the vertical separation of powers. Indeed, literature has shown that the effect of the economic performance on voting for the incumbent is significantly reduced when economic and fiscal policy is decentralized, more concretely when subcentral governments generate more of their income from their source tax revenues and can set themselves both the base and rates of taxation (Anderson, 2006, p. 445).

In Spain, subcentral tax revenue represents 24.6% of total tax revenue, and regions have 94.4% discretion on rates and reliefs, which is higher than countries like Austria or Belgium, and even Germany for the discretion on rates and reliefs (OECD, 2020). Regarding regional economic voting, while it has been proven to exist, it is lower than in the national elections (Lago Peñas and Lago Peñas, 2011). However, it is stronger in the regions that got access sooner to the economic autonomy, while in those that accessed later, regional voting is used to hold accountable the central government, not the regional one. This helps to understand the bad results that the Socialist Party got in the 2011 local and regional elections (Barreiro and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2012; Martín and Urquizu-Sancho, 2012). Madrid belongs to the last category (León and Orriols, 2016).

Therefore, regional elections can be “second-order elections” that are disputed based on national issues (Reif and Schmitt, 1980), for example, by using them to punish the central government, as has been proven to be the case in Spain with the case of Catalonia (Bosch, 2016). It could also be the case with the 2021 Madrilenian regional election, used as a plebiscite on national issues, and more concretely with the way to deal with the pandemic.

Literature about the effect of natural disasters on electoral outcomes shows that their effect on support for the incumbent in elections hold in the days following the disaster depends on the incumbent's response to such disaster: When the incumbent responds to the crisis by making declarations and offering compensation to those affected by the events, its vote share increases (Healy and Malhotra, 2010; Masiero and Santarossa, 2021).

Going to the electoral consequences of the pandemic of COVID-19, the first one was the difficulty to hold elections at the beginning of the virus spread, when many countries declared lockdown to contain the expansion of the virus, which forced to postpone many of them (Landman and Splendore, 2020), as it happened in Spain with the Galician and Basque regional elections (Santana et al., 2021). As for the elections that did take place, while there is not an overall change in turnout in the elections held during the pandemic, there was a decrease in those places where the number of deaths was higher (Santana et al., 2020; Fernandez-Navia et al., 2021) and individual perception about the risk of catching COVID-19 decreased propensity to participate in the elections (Chirwa et al., 2022).

Focusing more concretely on the effect of COVID-19 on electoral outcomes, it has been shown that in the US, it contributed to the victory of Joe Biden against incumbent Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election (Baccini et al., 2021). The case of the US is contradictory with other evidence that shows that in Western Europe, a “rally around the flag” process was observed, with increases in institutional and interpersonal trust (Bordandini et al., 2020; Bol et al., 2021; Esaiasson et al., 2021; Schraff, 2021; Gustavsson and Taghizadeh, 2023).

3. The context

3.1. The national context

The 2021 Madrilenian election took place in an exceptional context of economic crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused 12,470 deaths in 2020 in Madrid and 16,198 by the election day,1 and the measures adopted to fight its spread, which caused a drop of 9.8% in the regional GDP in 2020.2 Most of the campaign was focused on the dilemma between prioritizing the economy and public health.

The spread of COVID-19 in Spain led the central government to adopt extremely restrictive measures, with a national lockdown from 15 March to 21 April, after which a period of “de-escalation” started during which the restrictions were progressively lowered in the provinces with fewer cases. Due to Madrid having more COVID-19 cases than other regions, the de-escalation process was slower there. In Madrid, the de-escalation process ended on 21 June, which coincided with the central government losing its special powers following the end of the State of Alarm. The restrictions produced a great impact on the economy: in the first trimester of 2020, Spain's GDP contracted by 5.2%, the greatest contraction in Spanish history (Hernández de Cos, 2020).

The first elections being held during the pandemic in Spain were the regional elections of Galicia, Basque Country (July 2020), and Catalonia (February 2021). The first two elections were significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Originally scheduled for April, the elections had to be postponed due to the national lockdown imposed by the central government.

In the case of Galicia and the Basque Country, there was a drop in turnout: 4.7 points in Galicia and 9.2 in the Basque Country. Moreover, both incumbents (PP and Basque Nationalist Party) slightly increased their vote share. In those regions, Ciudadanos had no deputies in the Parliament, but in Galicia, it lost votes, and in the Basque Country, it went in coalition with the PP, but still, the sum of their vote share went from 12.19% in the previous election to 6.77%.

In Catalonia, the results were different: There was a strong decrease in turnout (27.8 points), and the incumbent lost some vote share (0.9 points). However, these results cannot be compared to those of Galicia and the Basque Country, since the 2017 Catalan regional election was an exceptional one. Indeed, it took place shortly after the central government, led by PP's prime minister Mariano Rajoy, suspended Catalonia's regional autonomy after the illegal independence referendum held on 1 October. The election was, therefore, extremely polarized, leading to the higher participation ever in a regional election in Catalonia. Moreover, the incumbent party, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), had not won the 2017 election but remained in third place, behind Ciudadanos and JUNTSxCAT, forming a coalition with the latter, and became the major partner in September 2020, when the regional president was disqualified by the courts, and vice president Pere Aragonès, from ERC, automatically became the president.

In the election held in February 2021, JUNTSxCAT (which runs under a new name, JxCat) went down to the third position, while ERC reached the second place, behind the Socialist Party, but with very small differences: The former lost 1.58 points and the latter 0.09. Ciudadanos also suffered great losses in this region, dropping from 25.37 to 5.58%.

After Madrid, there have been two more regional elections in Spain: Castille and León (February 2023) and Andalusia (June 2023). Castille and León, like Madrid, had an anticipated election called by its regional president, from the PP. In those elections, Ciudadanos also plummeted, going from 11 seats and being the minor coalition partner to only one seat, but the PP did not benefit from it, its results remaining almost the same, while Vox multiplied by three of its votes and was able to impose a coalition government on the PP (Ormiere, 2022).

In Andalusia, the PP came out very much reinforced, going from 20.75 to 43.11% and winning an absolute majority that allowed it to remain in office without Vox's support; meanwhile, Ciudadanos went from being the minor partner to disappear from the Assembly after losing 15 points in their vote share. In both regions, participation was lower than in the previous election (7 and 0.4 points, respectively).

Therefore, in all regional elections held between 2020 and 2021, there are some common patterns: improvement of incumbents' results (except in Castille and León), descent in participation, and reconfiguration of the right-wing bloc, with the disappearance of Ciudadanos and the consolidation of Vox (Ormiere, 2022).

As we will see, the 2021 Madrilenian regional election is different from the previous elections held in Spain since the outbreak of the pandemic. Indeed, only in Madrid and Andalusia, the incumbent improved its results that much, but Madrid was the only region where such a great increase in participation was observed, and where the campaign was focused on how to manage the pandemic. Therefore, Madrid is an exceptional case that contributes to understanding the impact of COVID-19 on elections and how citizens reacted to the restrictions.

3.2. The regional context

In September 2020, new restrictive measures were adopted by the Autonomous Community of Madrid following an order from the central government.3 At this point, certain regions ruled by the conservative Popular Party (PP), such as Galicia, Andalusia, or Madrid, had already started to show some discontent with the restrictions imposed by the central government, Madrid being the most belligerent.

However, while accepting the restrictive measures, Madrid's regional government filed an appeal in court, arguing that these restrictions were a limitation of fundamental rights and could not be made without the State of Alarm. The appeal was accepted on 8 October, and the central government responded the next day by declaring a new State of Alarm.

At this point, Madrid's PP started an aggressive rhetoric opposing the central government and the restrictions. In this framework, right-wing parties, and mostly the candidate of the PP, regional president Isabel Díaz Ayuso, positioned themselves as the defenders of the economy and Madrilenians' interest against the restrictions imposed by the central government, led by the socialist Pedro Sánchez, which goes in line with findings that right-wing parties were more inclined to keep economic activity vs. containing the pandemic (Rovny et al., 2022). This opposition was summarized by the tweet Isabel Díaz Ayuso posted when she dissolved the Assembly and called for an election, in which she appealed to choose between “socialism or freedom”. After 5 days, when Unidas Podemos' leader and vice president of the central government Pablo Iglesias announced he would be the candidate for his party, she made a similar tweet, this time writing “communism or freedom”.

In this context, the hotel and catering industry was especially symbolic, a sector hard hit by the capacity restrictions during the pandemic, and which, after the lockdown, was authorized to expand its terrace spaces, to compensate for the loss of customers indoors due to the capacity restrictions (Pérez et al., 2021). During the campaign, Isabel Díaz Ayuso presented herself as the defender of the bars, which became a symbol of the freedom she advocated in the face of restrictions.

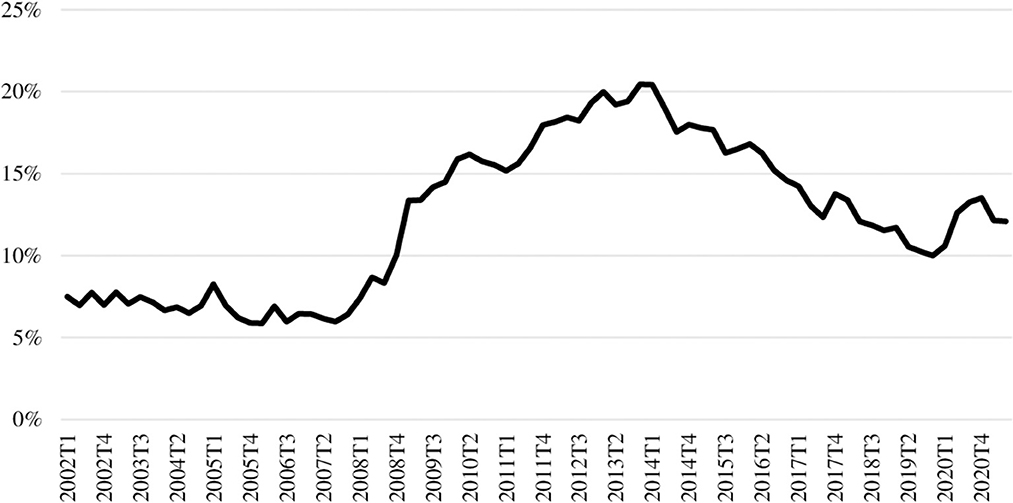

It is important to outline that, despite the magnitude of the economic shock over the GDP, regional unemployment did not rise as much as it had done during the 2008 crisis, during which it surpassed 20% at a certain point. As Figure 1 shows, while unemployment increased during the second quarter and remained higher than in 2019, it was only three points higher and started going down in the first quarter of 2021. The key to this difference compared to the 2008 crisis can be found in the government's response through furlough schemes (ERTEs by their Spanish acronym) that allowed to strongly mitigate the impact of the crisis on workers' income (Arce, 2021).

The Regional Assembly was dissolved, and a regional election was called on 10 March. That day it was announced that in Murcia, Ciudadanos was breaking up their coalition agreement with the local and regional PP after achieving a deal with the Socialist Party (PSOE) to form a new government both at the local and the regional level. At the time, Madrid was also ruled by a coalition between PP (major partner) and Ciudadanos (minor partner) in which there were strong tensions between both parties. When the news from Murcia came out, Ayuso declared she did not trust her coalition partner anymore, and that same day she dismissed Ciudadanos' autonomic counselors of her government, dissolved the Regional Assembly, and called for an election on 4 May.

Ciudadanos was a political party that started as a regional Catalan party in 2006, opposed to Catalan nationalism, and became a national party in 2014 when it obtained two seats in the European Parliament election (Rodríguez Teruel and Barrio, 2016). Following Podemos, it emerged in the Spanish political arena as a new party defying PP and PSOE's historical dominance, entering the parliament in 2015 and becoming the third party in the April 2019 general election. However, after the later election, its national leader, Albert Rivera, refused to support the incumbent president, the socialist Pedro Sánchez, to form a new government, and after the regional and local election of May 2019, he decided that his party would not support the Socialist Party in any region or major city, therefore, reaching agreements to give most of the regional and local power to the Popular Party. The inability of the parties to reach any agreement to choose a president led to its dissolution, and a new general election was held in November 2019, during which Ciudadanos plummeted, going from 15.86 to 6.8%. Albert Rivera resigned shortly after, and the party started a progressive decline in surveys; by May 2021, the average score they were getting in national polls was <5%, and at the regional level in Madrid, most of the surveys were giving them either a score slightly above 5% (minimum required to enter the regional Assembly) or less.

The main contenders in the 2021 Madrilenian regional election were the five big national-level parties and a regional party. The national-level ones were the Popular Party (PP), led by regional president Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the Socialist Party (PSOE), led by Ángel Gabilondo, Ciudadanos (Cs), led by Edmundo Bal, Vox, led by Rocío Monasterio, and Unidas Podemos (UP, a name they gave themselves after the alliance of Podemos with Izquierda Unida, the former Communist Party), led by Pablo Iglesias. Finally, Más Madrid was a regional party created from a split of UP in 2019, and in 2021, their candidate was Mónica García who despite being unknown at the time, gained visibility during the campaign.

The campaign took place in a tense and polarized atmosphere, with a clear division between the right- (PP, Ciudadanos, and Vox) and the left-wing blocs (PSOE, MM, and UP). On 23 April, UP's leader, Pablo Iglesias, received death threats, including bullets mailed to his home; the next day, during a debate with the other candidates (except Isabel Díaz Ayuso), Vox's candidate, Rocío Monasterio, refused to explicitly condemn such threats, which lead Pablo Iglesias to leave the debate, shortly followed by the other left-wing candidates. The increase of the affective polarization in Spanish politics in the last years also added more tension to the context of the election (Miller, 2020; Orriols, 2021).

The campaign was also national-oriented, with Isabel Díaz Ayuso focusing most of her rhetoric against central government president, Pedro Sánchez. This aspect of the campaign was increased by the fact that such a relevant figure in Spanish politics, Podemos' leader Pablo Iglesias, left the vice presidency to run as UP's candidate.

The popularity of Isabel Díaz Ayuso was an important element in her victory: After the election, 31% of the people who voted for the PP declared having done it because of the candidate; the second most important element was the position she held regarding the pandemic (15%).4

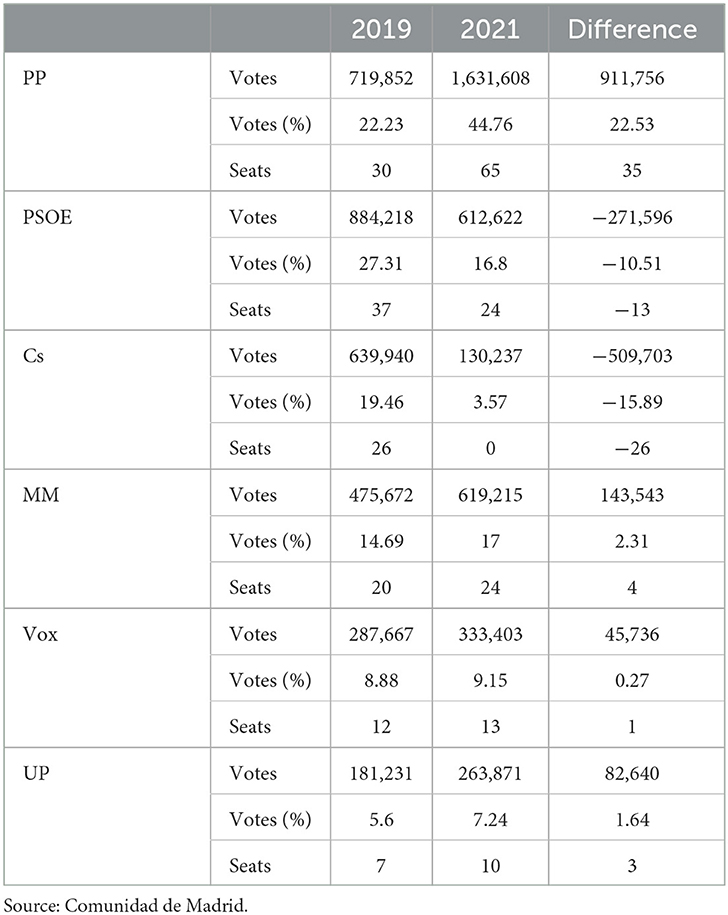

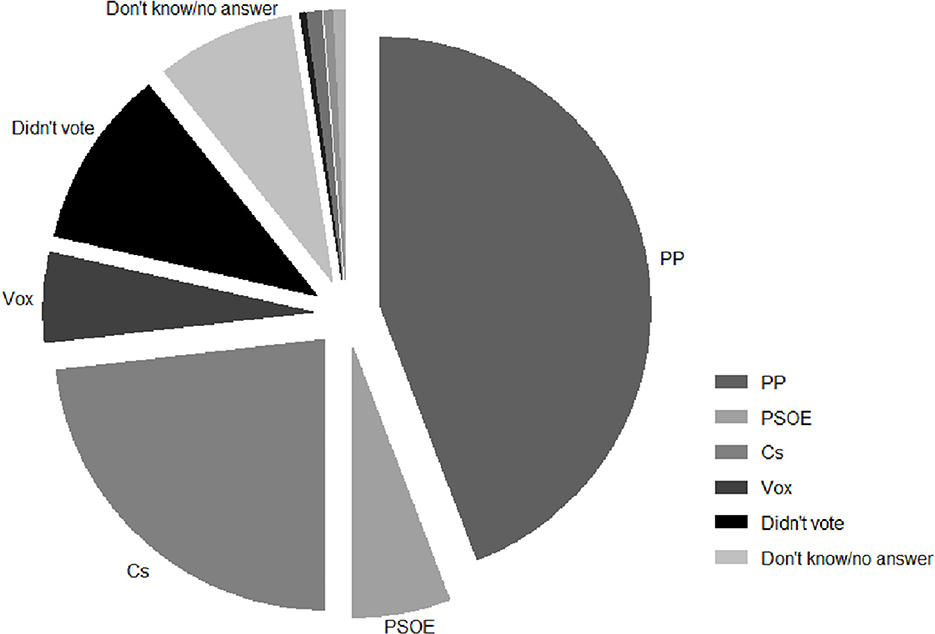

In the election, the PP improved its results by 35 seats compared to 2019, becoming again the first force and obtaining together with Vox a comfortable absolute majority. In parallel, Ciudadanos saw its votes plummet, going from having 26 seats and being the junior government partner to not obtaining representation due to the legal requirement of getting at least 5% to obtain seats. Meanwhile, the PSOE went from being the first force (with 37 seats) to being the third in the number of votes, being surpassed by 6,593 votes by Más Madrid, although they tied in the number of seats, both with 24 (MM obtained 20 in 2019). As for Unidas Podemos, it improved its results by 3 seats, obtaining 10. Table 1 presents the detailed results of the election.

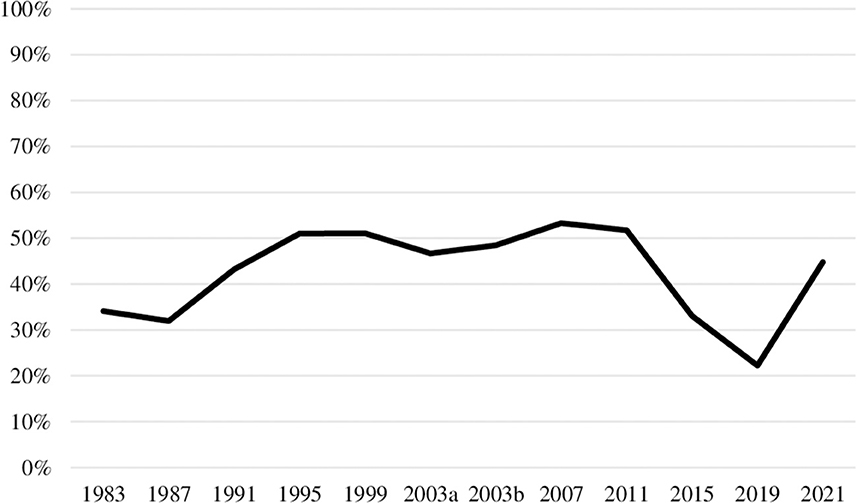

It is important to notice that the improvement of the PP compared to the 2019 regional election is not an extraordinary result, considering the historically good results of the PP in the Madrilenian regional elections, as Figure 2 shows. Rather, the poor performance of the PP in the elections of 2015 and 2019 was the exception. However, it is still interesting to explain how in only 2 years the ruling party made such a strong recovery in the middle of a health and economic crisis. While an important factor was the collapse of the center-right party, Ciudadanos, 66.1% of their 2019 voters changed their vote for the PP (García Lupato, 2021, p. 164), however, this is not enough to explain PP's increase, since the drop of votes of Ciudadanos was approximately 500,000 voters, while PP's obtained more than 900,000 new votes.

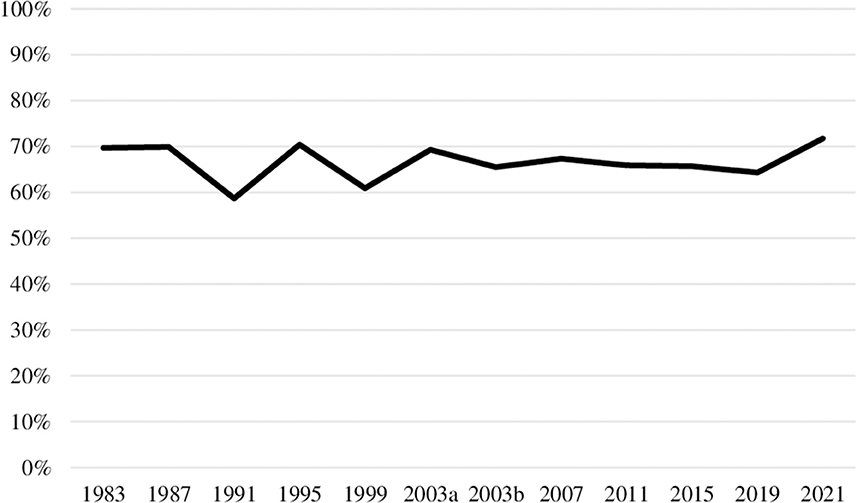

The election also showed a notable increase in turnout compared to previous regional elections, as Figure 3 shows. In general, 23.6% of the formerly abstentionist voters chose to vote for the PP, as well as 34.7% of those who were under 18 in 2019 (García Lupato, 2021, p. 164), which can help to explain PP's increase beyond the drop of Ciudadanos. In fact, as Figure 4 shows, the main source of new votes for the PP came, after Ciudadanos, from people who in 2019 abstained or did not remember what they had voted in that election.

An important aspect of the PP's result was that, for the first time, it was the most-voted party in all the 21 districts of the city of Madrid and 176 of 178 municipalities, winning even in the Southern municipalities called the “red belt” for their historic left-wing vote. While this could lead us to believe that there was high inter-bloc volatility, it is important to clarify that when we observe the results obtained by each bloc, municipalities, where the left-wing bloc won in 2019, kept a very high left-wing vote share, despite the increase of the PP. A plausible explanation for the increase of the PP even without great inter-bloc volatility is the strong increase in participation experienced by those zones in the regional election (Andrino et al., 2021).

Regarding volatility, since 2015 there has been a realignment, with a progressive increase in the right-wing bloc vote share and a decrease for the left-wing one, inter-bloc volatility in 2021 was lower than in the 2015 and 2019 regional elections, and most people who changed their vote did it inside their ideological bloc, showing a strong pattern of intra-bloc volatility (García Lupato, 2021, p. 163–64).

Summing up, the Madrilenian 2021 election provides a case in which the incumbent comes out strongly reinforced during an economic crisis, which can be explained by three elements:

The first is the fact that the economic crisis was due to an external shock, the irruption of COVID-19, a new disease against which there were no previous protocols or vaccines. Therefore, voters might have not blamed the regional government for the situation.

The second is that, supposing that voters would blame a political actor, this could also be the central government, which had taken the lead in the fight against the pandemic. Citizens could have chosen to blame it instead of the regional government, even more considering the latter's rhetoric against the former.

The third reason can be found in the way in which Isabel Díaz Ayuso decided to cope with the coronavirus, opting for fewer restrictions than other autonomous communities to prioritize economic activity. Many electors could have appreciated this and, therefore, chosen to support the regional PP.

4. Expectations

I claim that this election is a case of policy-based retrospective voting, in which electors that chose to vote for the PP did it due to its decision to preserve economic activity despite the pandemic. Citizens were mainly worried about the economic consequences of the pandemic, for which they were not holding responsible the regional government and, therefore, chose to vote for the party that promised to prioritize the economy. Therefore, I expect that in the zones in which the economic consequences were more severe (that is, those with the lower income), the increase of PP's vote share was greater:

E1: In low-income zones, the increase in PP's vote share was greater.

E2: In zones more severely affected by COVID-19, the increase in PP's vote share was greater.

The reason for those expectations is the focus of the campaign, around the issue of “economy vs. health”. In such a situation, low-income voters, fearing the economic consequences of the restrictions, would have preferred to vote for the candidate who was explicitly against the restrictions, as well as citizens living in zones more affected by COVID-19 and that had, therefore, already experienced restrictions and local lockdowns also wished to avoid new restrictions, hence the increased vote for the PP.

E3: The effect of COVID-19 on the increase in PP's vote share was greater in low-income areas.

The fact that the effect of COVID-19 could be greater in low-income zones is because those areas were especially vulnerable to the drop in economic activity, and, therefore, they had a greater incentive than richer zones to be afraid of new restrictions.

Moreover, considering the strongly polarized context in which the election took place, I argue that the success of the PP was not due to inter-bloc volatility, but rather to the mobilization of previously abstentionist voters and the absorption of former Ciudadanos' supporters (García Lupato, 2021, p. 164). Therefore:

E4: In zones where participation increased more, the increase in PP's vote share was greater.

E5: In zones with the higher Ciudadanos' drop, the increase in PP's vote share was greater.

E6: The effect of the variation in participation over the increase in PP's vote share was greater in low-income areas.

This expectation replicates E3, expecting again that low-income zones, fearing more the effect of new restrictions, voted more for the candidate who opposed such measures, and that, therefore, an increase in mobilization had a higher effect over PP's change in vote share than in the wealthiest ones.

Going to the individual patterns of voting, I also expect a correlation between economic need and change of vote switch toward the PP:

E7: Among those who did not vote for the PP in 2019, lower-class ones had a higher propensity to vote for the PP in 2021.

Considering that voting habits are acquired through age (Dinas, 2014), and young people have less established vote patterns:

E8: Among those who did not vote for the PP in 2019, young people had a higher propensity to vote for the PP in 2021.

Finally, and in line with retrospective economic voting, I expect the assessments of the situation to play a role in the decision to vote or not for the incumbent:

E9: Among those who did not vote for the PP in 2019, those who made positive assessments of the situation in the Autonomous Community of Madrid had a higher propensity to vote for the PP in 2021.

5. Data and methods

Two different analyses are run separately: first, with aggregate-level data and then with individual-level data.

The aggregate-level data will examine voting patterns at the level of the municipalities (178) and Madrid city districts (21). The dependent variable is the variation in PP's vote share between 2019 and 2021.

To explain it, I run a linear regression model using independent variables related to the sociodemographic characteristics of the areas and the incidence of COVID-19 over them, and two variables regarding other electoral outcomes.

Regarding the characteristics of the municipalities and districts, I use the average net income per person per year (in euros), the total cumulated cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 inhabitants since the start of measurement (counted the same day of the election), and the relative weight of each age group in that area; an interaction term will be added between the average net income and the incidence of COVID-19.

For the variables related to the other electoral outcomes, I use the change in turnout between 2019 and 2021 and the difference in Ciudadanos' results between 2019 and 2021. Again, an interaction term is added between the change in turnout and the incidence of COVID-19.

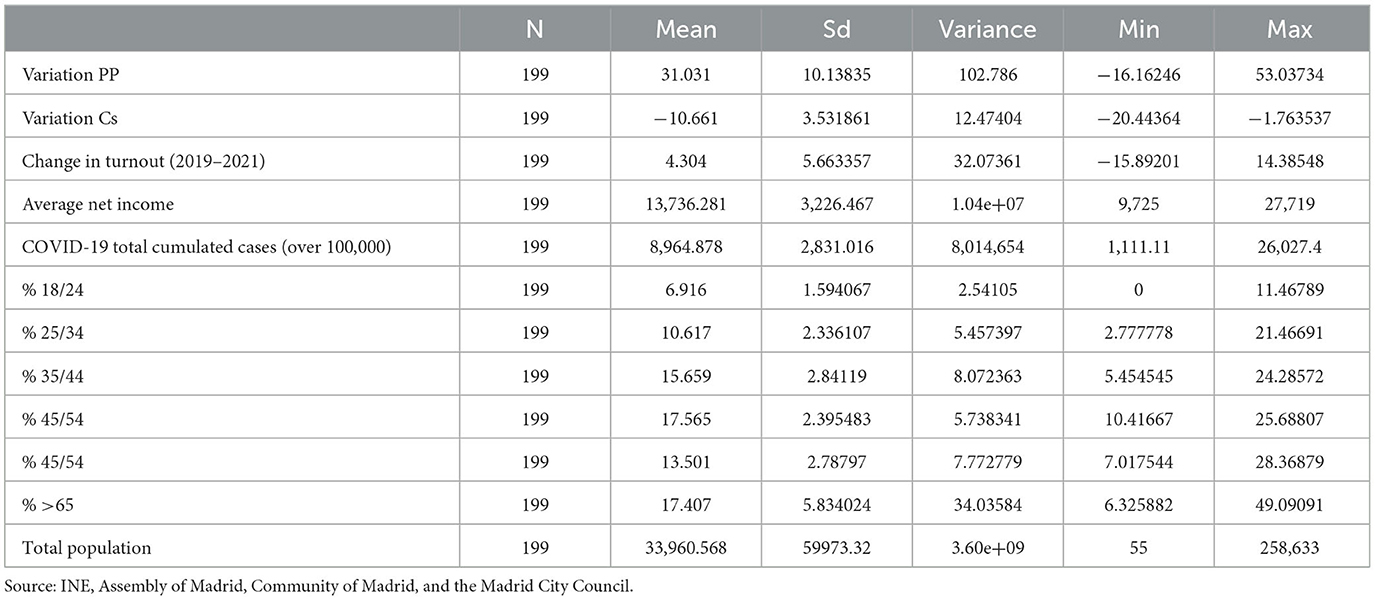

Data for the average net income and the weight of each age group come from the National Statistics Institute (INE, data of 2020, the last available); data about COVID-19 incidence come from the Autonomous Community of Madrid; and electoral results come from Madrid's Regional Assembly. Table 2 shows descriptive data for the abovementioned variables.

When using the variables of average net income, COVID-19 cumulated cases, and population of the district or municipality in the models, these will be divided by 1,000, since, as shown in Table 2, all of them have very large scales that might produce very small coefficients; even if such coefficients will produce a large cumulated effect due to the dimension of the scale, dividing them by 1,000 will facilitate the interpretation of the models.

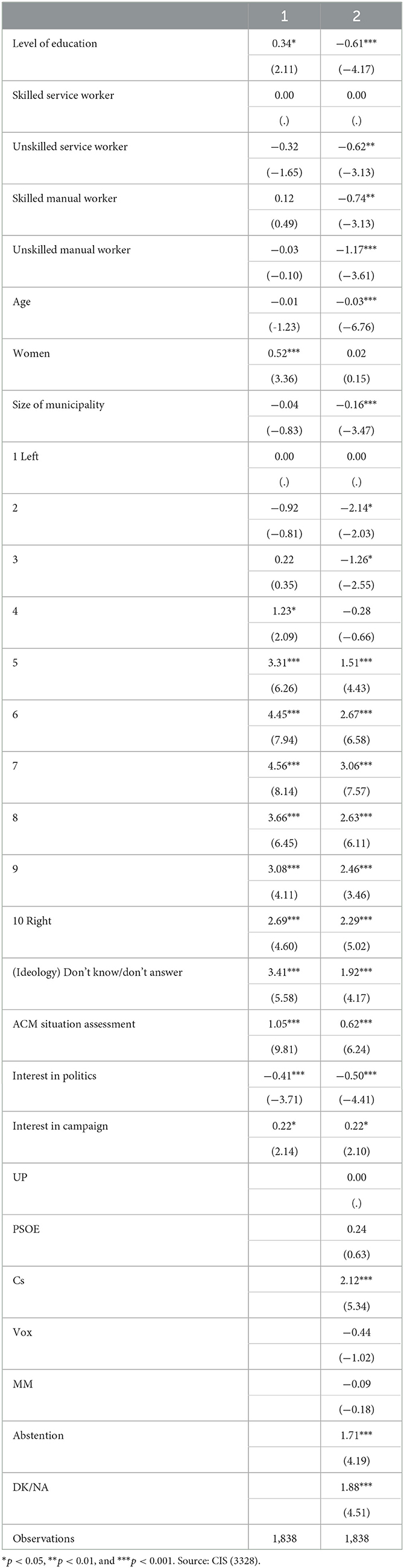

Going to the individual level, I will use the post-electoral survey made by the Center for Sociological Research (CIS) for the 2021 election (study 3,328). The dependent variable is having voted for the PP vs. having voted for another party in 2021, but the analysis is run only with those individuals who did not vote for the PP in the 2019 regional election, excluding those who did not have the right to vote, do not remember, or do not say who they voted for, the goal being to understand which factors led individuals to switch vote toward the PP. This way, the variable allows us to understand the factors that made individuals change their vote between 2019 and 2021 in favor of the incumbent. These conditions leave us with 1,838 observations, with which I run a logistic regression model.

To operationalize the concept of “lower class,” I use the education level and the occupation of the person who contributes the most income to the household of the respondent, following a 4-category scheme (skilled service sector worker, unskilled service sector worker, skilled manual worker, and unskilled manual worker).5 I also add to the model respondent's age, gender, the size of the municipality where he/she lived, the assessment of the general situation of the Community of Madrid (5-point scale), the ideology as a categorical variable (originally measured in a 10-point scale ranging from 1 to 10, but people who do not place themselves on the scale, either because they declare “Don't know” or do not answer the question, will also be analyzed, therefore, having 11 categories), the interest in politics (4-point scale), and the interest in the campaign (4-point scale).6

No questions were included in the survey regarding the impact of COVID-19 on respondents' personal lives, either if they suffered themselves or a close family member or friend. Therefore, we cannot evaluate the impact of coronavirus on vote choice in this election at the individual level.

To better explain the improvement of the PP results, I run a second model in which I add vote choice at the 2019 regional election to understand which voters were keener to switch their vote toward the PP in 2021. I use as a baseline having voted for Unidas Podemos in 2019 and analyze the propensity to vote for the PP in 2021 of the interviewees who voted in that election for PSOE, Cs, Vox, MM, abstainers, and those who do not know who they voted for or do not answer the question. I choose UP as the reference category since it is the party most ideologically distant from the PP.7

It is not possible to combine the individual- with the aggregate-level analysis since the CIS does not publish any geographical detail about the interviewees, such as the municipality in which they live, to keep anonymity. Therefore, it is not possible to associate interviewees with any geographical group (which would allow running multilevel models) or to associate them with any contextual data, analyzing the effect of the COVID-19 context on individual vote choice.

6. Results

6.1. Aggregate-level analysis

Table 3 shows aggregate-level results. To better interpret them, we must remember that both income and COVID-19 cumulated cases have been divided by 1,000, and, therefore, the coefficient must be interpreted as the impact over the dependent variable of adding 1,000€ to the average net annual income, or 1,000 cases to the cumulated incidence, over 100,000. The same happens with the population. Table 2 shows their minimum and maximum values, as well as other descriptive statistics.

When considering all these results, we must be cautious and remember they have been obtained with aggregate-level data. Therefore, while they are quite useful to observe correlations and supporting hypotheses, we cannot fully confirm them, since that could imply an ecological fallacy.

The net average income per person shows a significant and positive relationship with the improvement of PP's result, which contradicts E1. Indeed, this result shows that the PP improved its results in the wealthiest areas: 0.50 points for each extra 1,000€ average income per year in the area, on average.

There is no significant relationship between the impact of COVID-19 and PP's improvement. Therefore, E2 is not confirmed, and we cannot argue that in the areas where the pandemic had a greater impact people voted more for the party that was promising the end of the restrictions.

Regarding E3, and following the previous paragraph, the relationship between COVID-19 and the evolution of PP's results doesn't change depending on the average income of the area, since the interaction between both variable is not significant. Therefore, we must also reject E3.

By contrast, the results support E4: an increase of 1 point in participation in the 2021 election compared to 2019 is associated with an increase of 1.02 in PP's results, which gives support to the theory that Ayuso benefited from the higher mobilization.

E5 is not supported by the evidence: there is no significant relationship between the evolution of Ciudadanos' results in 2021 compared to 2019 and the evolution of PP's results.8

The fact that at the aggregate-level, the drop in Ciudadanos' results doesn't have any significant relationship with the evolution of PP's result is not necessarily a contradiction with what Figure 4 and previous literature show (García Lupato, 2021). Indeed, it is important to keep in mind that Table 3 shows aggregate-level data, and therefore does not allow us to know in detail what the individuals who voted Ciudadanos in 2019 decided to vote in 2021.

Finally, E6 is dismissed: The effect of the increase in participation over PP's vote share was not greater in low-income zones than in high-income ones, since the interaction between these two variables is not significant, which again dismisses the idea that low-income areas responded more to the context.

Going to the other variables of the model, a higher concentration of young people from 18 to 24 years old was associated with a higher increase in PP's results. While drawing conclusions from this could lead to an ecological fallacy, results with individual-level data in Table 4 will confirm this result, which supports the idea that young people, some of whom were socialized to politics under the pandemic, might have supported more Ayuso, who became very popular under the pandemic, but also that the age group less affected by the health consequences of the pandemic, and more hardly hit by the economic shock derived from them, might have supported the candidate who promised the end of restrictions. A higher concentration of any other age group is not significantly associated with any variation in PP's results.

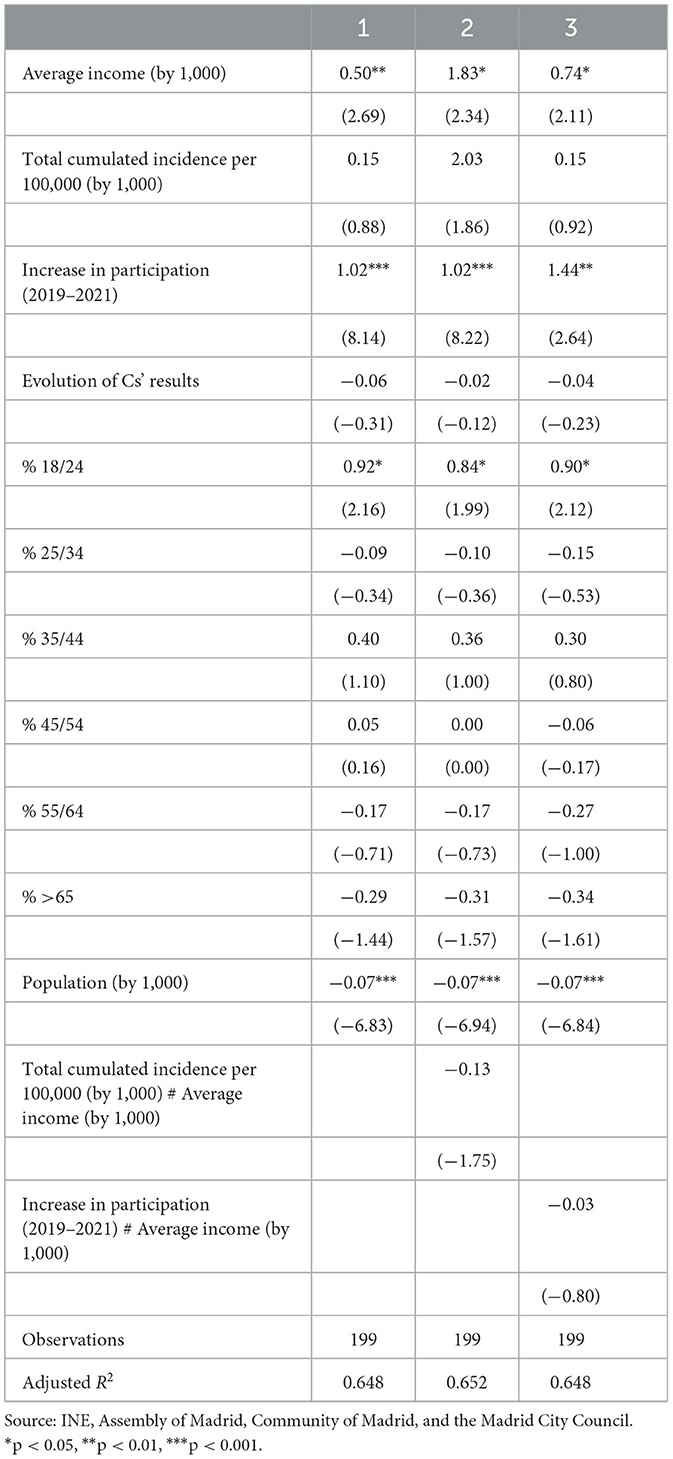

Table 4. Logistic regression models to explain vote choice for the PP in 2021 among those who did not vote for it in 2019.

There is no significant relationship between the relative weight of the other age groups and the evolution of PP's results.

Finally, the increase of PP's result was significantly lower in the more populated areas, even if the coefficient is very low: 0.07 less for every extra 1,000 inhabitants.

6.2. Individual-level analysis

Table 4 shows the results of the logistic regression models where the dependent variable is vote choice for the PP vs. another party in 2021. Remember that the analysis has been run only with those individuals who did not vote for the PP in 2019 and had the right to vote in that election, therefore analyzing the factors that led individuals to change their vote in favor of the incumbent. The first column contains a first basic model that does not consider vote choice in 2019, whereas the second column shows the result for a model with such variable, using having voted for UP in 2019 as the reference category.

Starting with E7, the role of social class remains unclear. While in the first model, education level produces a positive significant impact on switching votes toward the PP in 2021, in the second model, the one containing also individuals' vote choice in 2019, the coefficient becomes negative while increasing its significance. Regarding occupation, in the first model, it is not significant, but in the second one, it is, the result being coherent with the education, therefore, opposing E6, since all occupations have a lower propensity than the skilled service workers to vote for the PP, the coefficient being lower as occupations indicate lower social class. Therefore, it was not lower-class citizens who contributed to the improvement of PP's results, but rather higher-class ones.

Following E8, the results go in line with the expectation: among those people who did not vote for the PP in 2019, young people had a higher propensity to vote for the PP in 2021, as the second model shows. This confirms the expectation that young people, because their attitudes are not crystallized and they have not acquired stable voting patterns yet, are more willing to switch their support depending on the context; the result is congruent with the aggregate-level model.

Finally, E9 is supported: Making a positive assessment of the situation in the Autonomous Community of Madrid increases the propensity to vote for the PP in 2021, which goes in line with retrospective economic voting.

Regarding the other variables, women appear to have a higher propensity to switch their vote toward the PP, but this effect disappears when we introduce vote choice from 2019. The size of the municipality is significant in the second model, with people living in less populated municipalities having more chances to vote for the PP in 2021, which is coherent with the results of the aggregate-level model.

As regards the role of ideology, the coefficients of this variable become less significant after vote choice in 2019 is introduced, but remain significant, showing that left-wing citizens had a lower propensity to switch their vote toward the PP, while those placing themselves on the 5 and beyond had a higher propensity, as well as those that when they were asked their ideology did not know or did not answer. While the coefficients of those who were placing themselves on the scale show an expected result (either those placing themselves on the left or the right), the fact that those who did not place themselves on the scale also had a higher propensity to switch their votes toward the PP gives support to the idea that Ayuso was able to benefit from a great mobilization of citizens less politicized.

Regarding the two variables operationalizing interest, while overall interest in politics significantly decreased the propensity to vote for the PP in 2021 among those who did not vote for it in 2019, being interested in the campaign significantly increased the propensity to vote for it.

Finally, examining the propensity to vote for the PP in 2021 depending on vote choice at the 2019 regional election also confirms the previous story. Taking as the reference category those who voted for Unidas Podemos (because it is the party most ideologically distant from the PP), those who voted for Ciudadanos had the strongest propensity to switch their vote toward the PP, followed by those who did not know or did not answer, and those who abstained, with the other options not being significant. Once again, this gives support to the idea that the improvement of PP's results was due to the absorption of Ciudadanos' voters and the mobilization of previously abstentionist voters, people neither politicized nor interested in politics.

When comparing the aggregate-level model of Table 3 with the individual one from Table 4, both come to the same conclusion regarding the relationship between PP's improvement and both age (young people contributed to PP's victory). Regarding the socioeconomic position, both the income at the aggregate-level and the occupation at the individual one show that the PP improved its results among upper-class citizens, while the education level at the individual level of analysis provides unclear results. Regarding the role of previous Ciudadanos' voters in 2019, the individual-level evidence shows that such voters had a high propensity to switch to the PP in 2021, but at the aggregate-level, such pattern doesn't exist. Meanwhile, both aggregate- and individual-level evidence show that previous abstentionists, as well as people living in small municipalities, contributed to the improvement of the PP in 2021.

Moreover, this article gives some support to the idea that the impact of COVID-19 on citizens' personal lives increased their propensity to vote for the PP, therefore being a case of policy-based retrospective voting. This is supported by the fact that many PP voters said the main reason for voting for that party was how it dealt with the pandemic. However, the absence of questions about the impact of the pandemic on respondents' personal lives prevents us from fully confirming this idea if we want to avoid the ecological fallacy.

7. Discussion

At the 2021 Madrilenian regional election, the PP recovered from the bad result of the 2019 election, regaining the electoral support it used to gather in previous elections. By contrast, the third party, Ciudadanos, disappeared from the regional assembly, the PSOE went down, being surpassed by Más Madrid, and Unidas Podemos slightly improved its result, keeping its presence in the regional assembly.

The PP's recovery is mainly explained by the absorption of its main rival, the center-right party Ciudadanos (most of its voters coming from the PP in the first place), most of the latter going to the former, and to a lesser extent due to the mobilization of previously abstentionist voters. Other elements also contributed, such as the increase in support coming from young people, from those living in larger areas, and from those that were not interested in politics or politicized.

Regarding the literature on the effects of COVID-19 on elections, this article does not allow to draw any conclusion about the effects of the latter over the former. Indeed, the aggregate-level analysis doesn't show any significant relationship between the electoral results and the impact of the pandemic. However, individual-level data accounting for the impact of COVID-19 on respondents' personal lives would be needed to fully assess the impact of the pandemic on the 2021 Madrilenian election.

The election is also a case of second-order election used to punish the central government, either for its way of managing the pandemic or for the economic performance (or both), as previous regional elections in Spain have been proved to be used for such purpose (Bosch, 2016; León and Orriols, 2016).

Overall, the 2021 Madrilenian regional election followed the same pattern that the right-wing block is experiencing in Spain since 2019 in most regional elections: the collapse of Ciudadanos, most of its voters going to the PP, and the change toward a party system with two right-wing parties, the old mainstream PP and the radical right Vox. In this restructuring of the right-wing bloc, no evidence of great inter-bloc volatility has been found in the case of the 2021 Madrid regional election.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The author holds a FPU contract funded by the Spanish Ministry of Universities.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Juan Rodríguez Teruel and Oscar Barberà for their very useful and detailed comments and the participants of the workshop Party politics in Southern Europe after the COVID-19 pandemic of the XVI Congress of the AECPA, organized by Fabio García Lupato. Moreover, the article benefited greatly from the comments of two reviewers and the suggestions of the editor, XRV.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Carlos III Health Institute, Incidencias acumuladas y curvas epidémicas.

2. ^National Statistics Institute (INE), Contabilidad regional de España.

3. ^Movement between certain Basic Health Areas was prohibited except for reasons related to work, study, to manage formalities or to assist elderly or dependent persons, the capacity of all establishments open to the public was reduced to 50%, which had to close before 10pm, and the size of the meetings between individuals not living together was limited from ten to six people.

4. ^CIS, study 3328.

5. ^The CIS did not include any question about income in the survey.

6. ^The CIS did not include any question about candidates' evaluations in the survey.

7. ^While it would be interesting to run an analysis separating interviewees depending on which party they voted for in 2019, this would leave us with an insufficient number of cases (less than 500 per group).

8. ^It should be considered that this coefficient has been obtained from relative values and aggregate data. This implies that, having the PP more votes than Ciudadanos in most of the observations, the coefficient of the evolution of Ciudadanos' over PP's evolution does not mean that the increase of the PP is exclusively driven by changes in the vote choice of former Ciudadanos' supporters (which would not be possible in most cases, since the PP got more votes than Ciudadanos in 2019).

References

Anderson, C. D. (2006). Economic Voting and Multilevel Governance: A Comparative Individual-Level Analysis. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 449–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00194.x

Anderson, C. D. (2008). Economic Voting, Multilevel Governance and Information in Canada. Canad. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 329–354. doi: 10.1017/S0008423908080414

Andrino, B., Daniele, G., Kiko, L., Fernando, P., and Luis, S. P. (2021). El mapa con los resultados de las elecciones en Madrid por municipios y distritos: el auge de la derecha, la erosión del cinturón rojo y otras claves electorales. EL PAÍS.

Arce, Ó. (2021). Economic and Financial Developments in Spain over the COVID-19 Crisis. London: The European Economics and Financial Centre.

Baccini, L., Abel, B., and Stephen, W. (2021). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the 2020 US Presidential Election. J. Popul. Econ. 34, 739–767. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00820-3

Barreiro, B., and Sánchez-Cuenca, I. (2012). In the Whirlwind of the Economic Crisis: Local and Regional Elections in Spain, May 2011′. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 17, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2011.643616

Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., and Loewen, P. J. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: some good news for democracy? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 497–505. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12401

Bordandini, P., Santana, A., and Lobera, J. (2020). La fiducia nelle istituzioni ai tempi del COVID-19′. Polis 35, 203–13. doi: 10.1424/97365

Bosch, A. (2016). Types of economic voting in regional elections: the 2012 catalan election as a motivating case. J. Elect. Public Opinion Part. 26, 115–134. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2015.1119153

Bosch, A., and Durán, I. M. (2017). How does economic crisis impel emerging parties on the road to elections? The case of the Spanish podemos and ciudadanos. Party Polit. 25, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/1354068817710223

Bosco, A., and Verney, S. (2012). Electoral Epidemic: The Political Cost of Economic Crisis in Southern Europe, 2010–11′. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 17, 129–154. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2012.747272

Chirwa, G. C., Dulani, B., Sithole, L., Chunga, J. J., Alfonso, W., and Tengatenga, J. (2022). Malawi at the crossroads: does the fear of contracting COVID-19 affect the propensity to vote? Eur. J. Develop. Res. 34, 409–431. doi: 10.1057/s41287-020-00353-1

Costa Lobo, M., and Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2017). “The Economic Vote: Ordinary vs. Extraordinary Times,” in The SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behaviour, eds. K. Arzheimer, J. Evans, and M. S. Lewis-Beck (London: SAGE) 606–39.

Costa Lobo, M., and Pannico, R. (2020). Increased Economic Salience or Blurring of Responsibility? Economic Voting during the Great Recession. Elect. Stud. 65:102141. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102141

Dassonneville, R., and Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2013). Economic policy voting and incumbency: unemployment in western Europe. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 1, 53–66. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2013.9

Dassonneville, R., and Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2014). Macroeconomics, economic crisis and electoral outcomes: a national European pool. Acta Politica 49, 372–394. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.12

Dinas, E. (2014). Does choice bring loyalty? Electoral participation and the development of party identification. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 58, 449–465. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12044

Duch, R. M., and Stevenson, R. (2006). Assessing the magnitude of the economic vote over time and across nations. Elect. Stud. 25, 528–547. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.06.016

Esaiasson, P., Sohlberg, J., Ghersetti, M., and Johansson, B. (2021). How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: evidence from “the Swedish Experiment”. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 748–760. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12419

Fernandez-Navia, T., Polo-Muro, E., and Tercero-Lucas, D. (2021). Too afraid to vote? The effects of COVID-19 on voting behaviour. Eur. J. Political Econ. 69, 102012. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102012

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

García Lupato, F. (2021). The 2021 Regional Election in Madrid. A New Step in The Reconfiguration of the Spanish Party System? Pôle Sud. 55, 153–170. doi: 10.3917/psud.055.0153

Gustavsson, G., and Taghizadeh, J. L. (2023). Rallying around the Unwaved Flag: National Identity and Swedens Controversial Covid Strategy. West Eur. Polit. 23, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2023.2186027

Healy, A., and Malhotra, N. (2010). Random events, economic losses, and retrospective voting: implications for democratic competence. Quart. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 193–208. doi: 10.1561/100.00009057

Healy, A., and Malhotra, N. (2013). Retrospective voting reconsidered. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 16, 285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-032211-212920

Hernández de Cos, P. (2020). El Impacto Del COVID-19 En La Economía Española. Presented at the Consejo general de economistas, Madrid.

Hobolt, S. B., and Tilley, J. (2014). Whos in Charge? How Voters Attribute Responsibility in the European Union. Compar. Polit. Stud. 47, 795–819. doi: 10.1177/0010414013488549

Kriesi, H. (2012). The political consequences of the financial and economic crisis in europe: electoral punishment and popular protest. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 18, 518–522. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12006

Lago Peñas, I., and Lago Peñas, S. (2011). Descentralizacion y Control Electoral de los Gobiernos en España. 1a ed. Barcelona: Institut dEstudis Autonòmics.

Landman, T., and Splendore, L. D. G. (2020). Pandemic democracy: elections and COVID-19′. J. Risk Res. 23, 1060–66. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1765003

León, S., and Orriols, L. (2016). Asymmetric Federalism and Economic Voting. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 847–865. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12148

Martín, I., and Urquizu-Sancho, I. (2012). The 2011 General Election in Spain: The Collapse of the Socialist Party. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 17, 347–363. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2012.708983

Masiero, G., and Santarossa, M. (2021). Natural disasters and electoral outcomes. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 67, 101983. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2020.101983

Miller, L. (2020). Polarización En España: Más Divididos Por Ideología e Identidad Que Por Políticas Públicas. Madrid: Esade.

Ormiere, L. (2022). Les élections autonomiques de février 2022 en Castille-et-León: recomposition des droites, fragmentation accrue et affirmation de la ≪ España vaciada. Pôle Sud. 57, 99–115. doi: 10.3917/psud.057.0099

Orriols, L. (2021). La polarización afectiva en España: bloques ideológicos enfrentados. Center for Economic Policy - EsadeEcPol. Available online at: https://www.esade.edu/ecpol/es/publicaciones/polarizacion-afectiva/ (accessed August 1, 2022).

Orriols, L., and Cordero, G. (2016). The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21, 469–492. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454

Peffley, M. (1984). The voter as juror: attributing responsibility for economic conditions. Polit. Behav. 6, 275–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00989621

Pérez, V., Aybar, C., and Pavía, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and changes in social habits. restaurant terraces, a booming space in cities. the case of Madrid. Mathematics 9, 2133. doi: 10.3390/math9172133

Reif, K., and Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections - a conceptual framework for the analysis of european election results. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 8, 3–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

Rodríguez Teruel, J., and Barrio, A. (2016). Going national: ciudadanos from catalonia to Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21, 587–607. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2015.1119646

Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., et al. (2022). Contesting COVID: the ideological bases of partisan responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 61, 1155–1164. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12510

Santana, A., Esquer, C. F., and Caamaño, J. R. (2021). “Los procesos electorales en el mundo durante el covid-19,” in Anuario de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid 3, 15–32.

Santana, A., Rama, J., and Bértoa, F. C. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic and voter turnout: addressing the impact of COVID-19 on electoral participation. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/3d4ny

Schraff, D. (2021). Political trust during the COVID-19 pandemic: rally around the flag or lockdown effects? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 1007–1017. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12425

Keywords: COVID-19, incumbent, retrospective voting, vote swift, mobilization, regional economic voting

Citation: Coulbois J (2023) The 2021 Madrilenian regional election: how can the incumbent improve its results in times of crisis? Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1170294. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1170294

Received: 20 February 2023; Accepted: 03 May 2023;

Published: 31 May 2023.

Edited by:

Xavier Romero Vidal, University of Cambridge, United KingdomReviewed by:

Agusti Bosch, Autonomous University of Barcelona, SpainPablo Simón, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Coulbois. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jaime Coulbois, amFpbWUuY291bGJvaXNAdWFtLmVz

Jaime Coulbois

Jaime Coulbois