- Research Unit on Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policies, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Introduction: China is currently ranked second in the world economy, and its political role in the global order has increased in recent decades. As part of one of its modern and emblematic international projects, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the Health Silk Road, which can be considered a branch officially launched in 2017. Driven by some external factors, the most important of which is the COVID-19 pandemic, the Health Silk Road (HSR) and Chinese public health policies have gained accrued relevance, especially in countries of the Global South, which have been the main partners of Chinese cooperation initiatives, not only in health.

Methods: This study is an exploratory exercise that reflects the potential gains resulting from Chinese- Global South cooperation in the health sector by analyzing the perceptions of Brazilian health agents in a contemporary period starting from 2013 to 2023, which is the first 10 years since BRI implementation. We intend to answer the following questions: Does Brazil benefit from health partnerships with China, specifically under the Health Silk Road, despite not having formally joined the BRI? What are the privileged health areas of implementation, and what are the gains? These questions were answered through interviews with Brazilian researchers from public institutions to obtain their perspectives and insights regarding the practical aspects of partnerships.

Results and discussion: The current partnerships established are not directly linked to BRI initiatives. Brazilian health agents are generally unaware of the BRI contours and, consequently, HSR. The model of cooperation identified is based on the theoretical premise that each stakeholder contributes their best assets. New potential research topics were identified from this exploratory research to reflect on the impacts of HSR and Chinese Health Assistance in the Global South. We suggest in-depth research on the influence of the health sovereignty concept on the global health performance of countries from the Global South.

1 Introduction

China is currently ranked second in the world economy, and its political role in the global order has increased in recent decades. One of its more recent and emblematic flagships has been President Xi Jinping's “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), which was launched in 2013. The BRI is a comprehensive and ambitious initiative that focuses on infrastructure development, regional connectivity, and economic cooperation on a global scale and is often perceived as a continuation of the “Going-Out Policy” that was pursued by the Chinese government since 1999 and was aimed at encouraging Chinese firms to invest abroad (Oliveira et al., 2020). According to the same authors (p. 1), the BRI does not constitute a strict top-down imposition from Beijing but is rather a “bundle of intertwined discourses, policies, and projects that sometimes align but that are sometimes contradictory”, depending on the specificities of the projects and places where they are implemented. The five major priorities of the BRI are emphasized in official statements as follows: policy coordination, facility connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds (Jauregui, 2020).

Derived from the BRI, the expression Health Silk Road (HSR) was first used by President Xi Jinping in 2016 during a visit to Uzbekistan and was then made official in 2017 during the Belt and Road Initiative Forum through an official document called the Beijing Communiqué of the Belt and Road Health Cooperation & Health Silk Road (Santiago, 2021). Some months later in the same year, China signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the World Health Organization (WHO), with the objective of enhancing health outcomes in BRI nations (Lancaster et al., 2020). The HSR presents eight major goals (Chow-Bing, 2020): (1) securing political support for health cooperation; (2) construction of mechanisms to control, exchange, and coordinate information regarding infectious diseases; (3) capacity building and long-term human resource training; (4) cooperative framework for public health emergencies; (5) raising awareness for the potential of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM); (6) cooperation over a wide range of issues related to healthcare system and policies, such as health insurance, healthcare reform, and health laws; (7) institutionalization of medical aid to BRI countries; and (8) the development of the potential of healthcare industry, including medical tourism, export of China's medical equipment and pharmaceutical products, and foreign investment in health-related enterprises.

Another Chinese health program is “Healthy China 2030”, a plan established in 2015 that sets the main guidelines for Chinese inner healthcare system reform until 2030 and is based on the premise of “Health for All, All for Health” (Tan et al., 2017). It focuses essentially on promoting healthy lifestyles, optimizing health services, enhancing health protection, building a healthy environment, and developing the Chinese health industry and TCM (Tan et al., 2017). In this policy document, there is a chapter on international health cooperation that states the following:

(…) Using bilateral cooperative mechanisms as the basis, China would innovate on models of [health] cooperation and strengthen people-to-people exchanges with countries on the BRI. China also would strengthen South–South Cooperation, strongly implement China–Africa public health cooperation projects, and continue to send out medical aid teams to developing countries, with particular emphasis on maternal and children healthcare. […] China will fully utilize high-level dialogue mechanisms and include health in the agenda of China's major country diplomacy. China would proactively participate in global health governance, and exercise its influences in the studies, negotiation, and formulation of international standards, norms, and guides, therefore increasing its international influences and institutional discourse power in the health sector (…).

Hence, the HSR is an instrument that helps foster China's role in global health, positioning the country as a proactive and responsible global health actor by engaging in “health-related initiatives, providing financial contributions, technical assistance, and capacity-building support, participating in global health forums, and forging strategic partnerships” (Yuan, 2023, p. 336). This Chinese role in health governance is particularly observable in countries of the Global South, which are the developing countries of Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia, and Oceania. These can be either large economies, such as Brazil, or small economies. Countries, such as China, which have a very high gross domestic product, are still classified as Southern because the rates of social inequality and illiteracy, among others, are still a concern. Indeed, South–South cooperation has been deepening in recent decades and evolving as “a set of practices in pursuit of historical changes through a vision of mutual benefit and solidarity among the disadvantaged of the world system” (Gray and Gills, 2016, p. 557). According to several authors (Harris, 2005; Taylor, 2009; Gills, 2010), this new global order arrangement is based on the assumption that world development can be achieved with new forms and mechanisms of governance and new institutions that are more coherent with the mutual interests of sustainable growth and mutual assistance between countries, distinguishing it from the current order derived from the period of post-Cold War and colonialism mostly dominated by countries of the Global North. This potentially new paradigm of development polarizes opinions in academia, with some scholars defending that this constitutes, in fact, a novelty and a shift in development models conducive to what Girado (2018, p. 114) states as “multilateralism leaded by the Global South, with Chinese characteristics, without Western hegemony”; and other scholars arguing that it is simply a new narrative that—translated into practical terms—will let the current status quo remain, only changing the actors: “old wine in new bottles” (Alden and Vieira, 2005; Gray and Gills, 2016).

As far as China is concerned, regarding the new global order and Global South cooperation, it is a topic that has been widely discussed in the academic and scientific literature recently. Over the past few decades, China has increased its participation in international debates and institutions, evolving from a passive observer to an active player (Johnston, 2008; Johnston and Johnston, 2013; Noesselt, 2022). According to Noesselt (2022, p. 2), “Beijing is concerned with the symbolic recognition of being an equal partner and its right to participate in the official shaping of the international system.” In addition to the long-established international structures, it has been part of recently created regional and multilateral arrangements, such as the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEANs) and Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS), and even creating new institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank, taking part as a rule-maker (Noesselt, 2022).

In terms of global health governance, Latin America and Brazil, in particular, have a long history of participation in health governance (Birn, 2011) that can be traced back to 1881, when the 5th International Sanitary Conference was held in Washington and yellow fever was widely discussed (Herrero and Belardo, 2022). Indeed, yellow fever was, at that time, the main disease affecting Latin America, and it pushed the region to dedicate much effort and attention to international health (Sacchetti and Rovere, 2011; Herrero and Belardo, 2022). Furthermore, in 1902, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) was founded, becoming the world's oldest international public health organization and serving now as the WHO Regional Office for the Americas (Bianculli et al., 2021).

The awareness that health and living conditions are mutually reinforcing has been growing over time, as has the emphasis on the role of social and health policies in addressing poverty and reducing inequalities, especially in Latin America, leading to the increasing recognition of health as a significant factor in international relations and regional policy agendas, particularly in the mentioned geography (Riggirozzi and Tussie, 2012; Herrero, 2017; Herrero et al., 2019). Latin America's history of international cooperation on health has evolved and expanded in the twenty-first century, in part enhanced by center-leftist governments in major parts of these countries that tend to promote new practices and arrangements in the sphere of social policy cooperation, despite this situation being reversed in the case of Brazil with the election of President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 (Bianculli et al., 2021). In the Findings section, the impact of Jair Bolsonaro's mandates on health cooperation will be further discussed.

A shift in international cooperation dynamics, where countries, especially from the Global South, are embracing a more equitable, collaborative, and solidarity-based approach to address their social needs, reflects a desire for greater self-reliance and empowerment, moving away from traditional donor–recipient relationships (Vance et al., 2016; Herrero et al., 2019). As a consequence of this new global order with new emerging actors, it is possible to acknowledge the growing importance of South–South cooperation in the current multilateral world that has driven a “genuine re-balancing in the international development architecture, development financing approaches and actors, and in shifting paradigms of aid, development and partnerships” (Power, 2011, p. 997), as well as in health assistance. Indeed, in recent years, we have been assisting in the burgeoning of South–South cooperation also in health (Birn et al., 2019), defined by the World Health Organization as “the exchange of expertise between actors (governments, organizations and individuals) in [low and middle-income countries—LMICs]. Through this model of cooperation, [these] countries help each other with knowledge, technical assistance, and/or investments” (World Health Organization, 2017). Inserted into foreign aid policy, health assistance is divided into eight main areas of action according to the Chinese State Council deliberation (State Council Office of the PRC, 2014): (i) complete projects, (ii) goods and materials, (iii) technical cooperation, (iv) human resources development cooperation, (v) medical teams, (vi) volunteer programs, (vii) medical teams, and (viii) emergency humanitarian aid and debt relief. Relatively to China–Latin America countries, foreign relations do not follow a linear path, as there is not a homogeneous position toward China, with each country presenting very different levels of trade, diplomatic relations, and other factors (Jauregui, 2020).

Regarding health, it may be noted that there is a lack of thorough research on health cooperation between China and Latin American countries under the BRI framework, unlike with African countries. Such a fact might be explained by the historical background of Chinese aid to Africa in comparison with Latin America, and Africa is the largest recipient of China's Development Assistance for Health (Tambo et al., 2016). This study sets the pace to develop scientific research concerning China–Latin America health cooperation, pointing to some key ideas by using Brazil as a case study and representative country of Latin America and the Global South.

2 Methodological approach

This study used a qualitative methodology based on a literature review for accurate framing of concepts, complemented by content analysis of five semi-structured interviews conducted with senior researchers and coordinators from credited health entities in Brazil and interpretative analyses. The choice of Brazil as a representative case from the Global South is mostly due to the fact that it was easier for us to reach health agents as our institution has scientific protocols with Brazilian entities, namely with Fundação Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz through an international platform for science, technology, and innovation in health.

We decided to conduct semi-structured interviews because one of the objectives of the study was to gather information about health agents' perceptions regarding the topic of Chinese cooperation with Brazil through HSR. For this purpose, we believe that interviews are the most efficient method to apply, as it “(…) allows the researcher to collect open-ended data, to explore participant thoughts, feelings and beliefs about a particular topic and to delve deeply into personal and sometimes sensitive issues” (DeJonckheere and Vaughn, 2019, p. 1). The interviews were based on a script organized in three parts: the first, with four questions focused essentially on the BRI and HSR; the second, with four questions related to global health governance and the perceived role of China and Brazil in the system; and the third, with four questions oriented toward the Sino-Brazilian health partnership.

The choice of Brazil as the case study was based on our intention to study a paradigm example of the Global South. Brazil fills this gap because, besides being from the Global South, it is a member of BRICS and a relevant player in health policy and governance. In turn, Brazilian researchers were chosen to be interviewed because they belong to public entities for mission health promotion and social development and can well illustrate the perceived potential impacts of the HSR and partnerships with China in the health field for the Brazilian population. The selection of these five specific interviewees was based on the following criteria: (i) seniority in research activities; (ii) functions related to public health; and (iii) availability and willingness to participate in the study. All interviews were conducted online using Zoom, with an average duration of 1 h, and were recorded upon interviewee authorization. The verbal content of these recordings was transcribed into naturalized text file transcripts (Bucholtz, 2000; Azevedo et al., 2017) that underwent manual content analysis and were translated into a matrix (partially replicated in the next section) with relevant themes and categories as well as meaning units, according to Bardin's method (Bardin, 2010).

In the following sections, we outline the main findings of the content analyses resulting from the interviews, divided into three main categories: (1) the relevance of the BRI in a broader sense and of the HSR in particular; (2) the role of Brazil and China in global health governance (GHG); and (3) China–Brazil health relations, areas of partnership, and lessons learned.

3 Findings

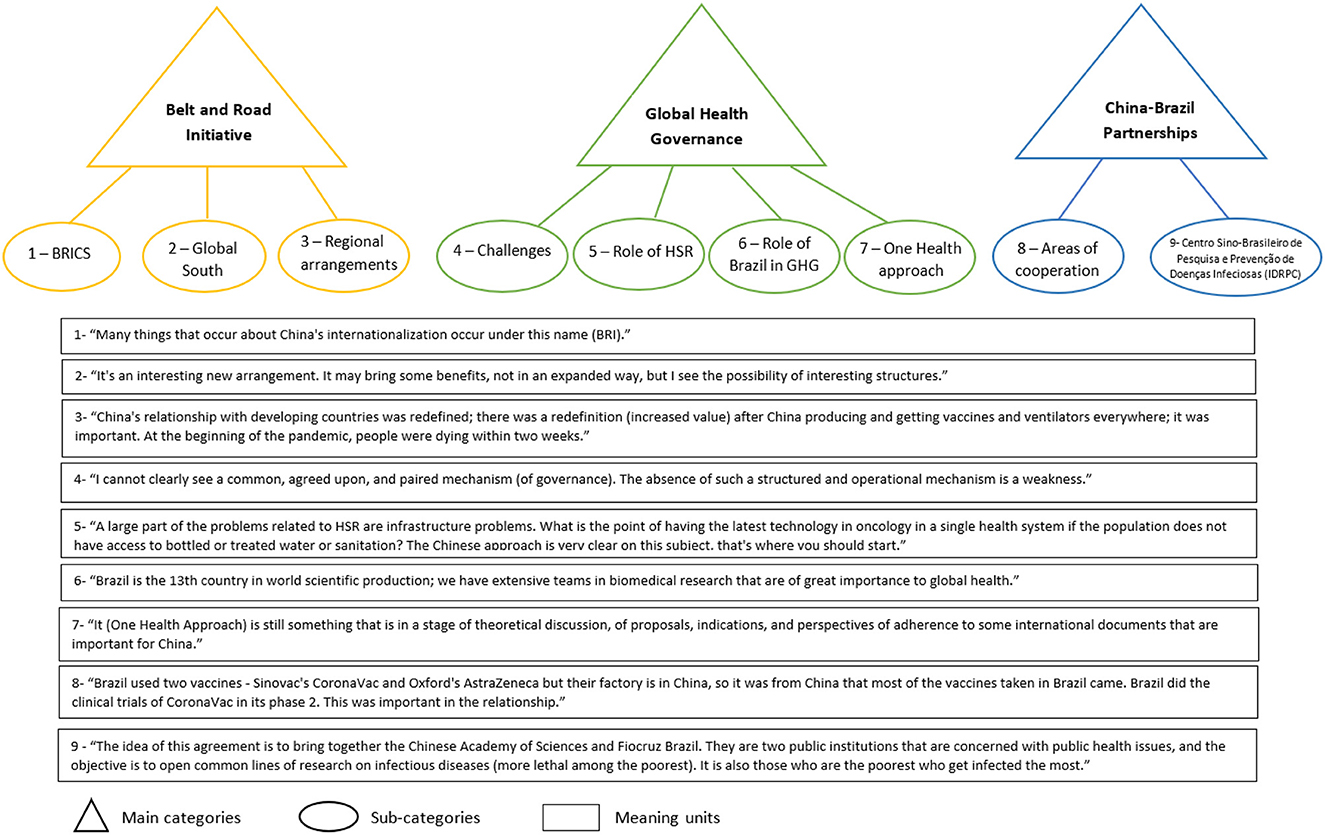

Following the methodological process described above, we gathered all information in an analytical matrix, whose categories and subcategories are visually summarized in Figure 1. We obtained a structured vision from the perspective of Brazilian health researchers and practitioners. The main findings of the interpretative analysis are presented below, with each section corresponding to the three main categories resulting from the content analysis of the interviews.

Figure 1. Resume of main categories and sub-categories and respective meaning units resulting from content analysis of interviews (source: authors' elaboration).

3.1 BRI and HSR

As mentioned in the Introduction, the BRI is a broad Chinese project based essentially on the creation of infrastructure and connectivity in various forms across the five continents and ~150 countries that adhere to it or manifest an intention to adhere to it (McBride et al., 2023). Brazil has not yet formally adhered to it but has shown some intention to do so after the election of President Lula da Silva in October 2022.

Despite the BRI dimension, few researchers are aware of it and have revealed knowledge about the initiative; the same applies to the HSR concept. The interviewees who knew about the BRI stated that it is very ambiguous and unclear for recipient countries to determine whether the projects, programs, or partnerships are carried out under the initiative. Interviewee 1 (Advisor and Head of Communications), who is currently living in China, stressed that “For Chinese government, everything that is being done is implicitly under the BRI umbrella even if it is not mentioned.” All interviewees agreed that it is a project that has a historic connotation (related to Ancient Maritime Silk Roads), and whose main advantage is based on a developmental agenda that has the goal of empowering states to increase their productive capacities, in line with what is suggested in literature.

The developmental component of the BRI is particularly evident in the relationship between China and countries in the Global South, including Brazil, and is aligned with the adopted position in Latin American countries as a whole of following its own development strategy—in the case of health with the so-called Socialist Medicine approach—in order to avoid inequities, partially resulting in the application of neo-liberal principles (Herrero et al., 2019). All interviewees agreed that the existence of regional arrangements, such as the BRICS, is committed to the need to increase their bargaining power and influence in international bodies, and that, because they represent ~40% of the world's population (Acharya et al., 2014), they are also seen as a large consumer group in terms of economy and trade. These kinds of regional arrangements were perceived by all interviewees as a sign of commercial and diplomatic robustness and as beneficial for individual states, despite the proportion of benefits being different for each one. In the case of health, this might be mostly explained by the fact that “the BRICS countries vary greatly in terms of their burdens of disease, health systems, interests in the global pharmaceutical trade, engagement in the international arena and much else” (McKee et al., 2014, p. 452). In addition to these variations, the BRICS countries do not present a direct correlation between wealth and health, as they have improved their economic indicators quite quickly in recent decades. However, as a consequence, they are simultaneously facing a number of challenges that impact health: (i) aging population; (ii) lower levels of fertility; (iii) rapid urbanization and lifestyle changes; and (iv) changes in dietary habits (Kickbusch, 2014).

When asked about the perception of Brazil's positioning in the BRICS, the most emphasized aspect was that Brazil has a strong implemented framework to deal with health and innovation, as there are many public health institutions, such as Instituto Butantan, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz Brazil, Universidade de São Paulo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, and Universidade Federal da Bahia, which work hard to support the Brazilian health system with many inputs (know-how and products). As per Jakovljevic et al. (2017), “Today, this country [Brazil] remains the only high-income one among the BRICS with significantly higher institutional capacities compared to the others.” Thus, it seems better positioned within the BRICS to articulate health policies and communicate them to the WHO, as Brazil has long been present in several spaces of multilateral dialogue on health (Almeida et al., 2023).

During the interviews, one aspect highlighted by some agents was that the COVID-19 pandemic gave new significance to China–Brazil relations. Though China–Brazil relations during this period were quite tense due to Brazilian federal political leadership, the fact that China was the main manufacturer and supplier of ventilators and medical equipment crucial for the survival of many people, including in Brazil, was significant. Furthermore, another crucial fact was that Brazil was one of the countries that benefited immensely from the Chinese manufacturing capacity in vaccine production, as it used two vaccines, CoronaVac from Sinovac (China) and AstraZeneca–Oxford (Great Britain, but produced in China).

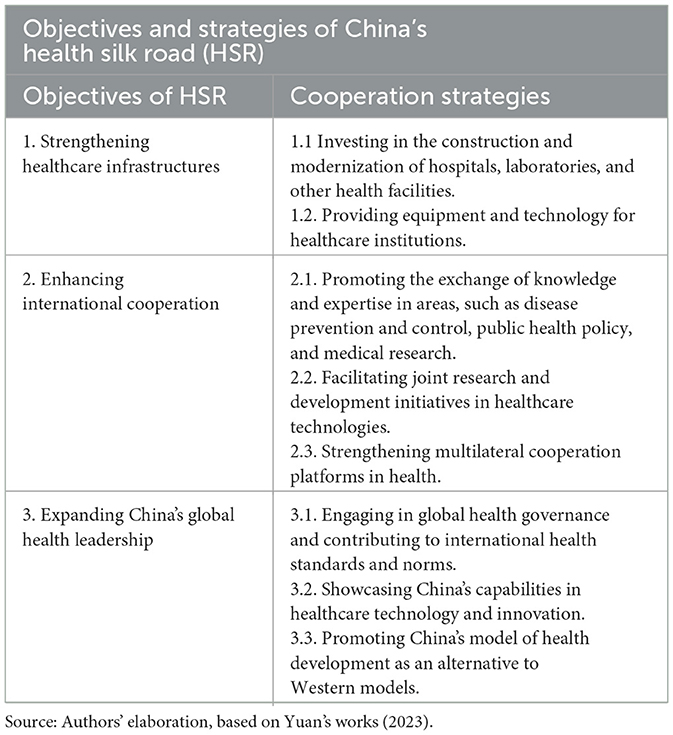

According to Park et al. (2021), despite the COVID-19 pandemic affecting the BRI, it has caused delays in the implementation and execution of projects but not cancelations. This calls for a focus on HSR, which is a branch of the BRI that can be understood as a mechanism to promote health cooperation across the globe (Santiago, 2022; Vadlamannati and Jung, 2023). The main objectives and strategies of the HSR are summarized in Table 1 (Yuan, 2023, p. 337).

Despite the fact that the interviewees revealed an unclear understanding of HSR, after a brief explanation of its context and main purposes, they recognized its important role in international health and its aid in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, citing two examples: (i) Many developing countries could access the COVID-19 vaccine made in China because of China's manufacturing capacity; otherwise, immunization of their populations would have been difficult; (ii) After the opening-up of the Chinese economy in the 80s, China, along with India, produces most of the world's active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), which serve as the foundation for the production of many medicines and drugs available today in the global market.

3.2 Global health governance: respective roles of Brazil and China

Global health governance (GHG) is a relevant issue in today's world. It has been studied in recent decades by several authors from various fields, such as public health, health sciences, international relations, and social sciences. Among the scholars and researchers studying this topic, we would like to emphasize the study developed by Kickbusch and Fidler, according to whom (2010, p. 3), GHG can be understood as: “(…) the use of formal and informal institutions, rules, and processes by states, intergovernmental organizations, and non-state actors to deal with challenges to health that require cross-border collective action to address effectively”. As stated by Kickbusch and Reddy (2015, p. 841), “Today, global health is perceived as fundamental for national and international security, domestic and global economic wellbeing, and economic and social development in less developed countries, is also a major growth sector of the global economy.”

Regarding GHG, as pointed out by the interviewer, all participants agreed with the challenges to the current system, such as the lack of mechanisms for effective information sharing, for the implementation and monitoring of concerted actions, and for a component of continuity in financial and resource investment. When questioned about the potential reasons for the scarcity of mechanisms to deal with the challenges and improve the GHG system as a whole, two factors stand out from interviewees' insights: (i) the lack of political will associated with the fact that certain governments give primacy to their national systems over global ones, raising the question of national health sovereignty that can be further developed in future research, and (ii) the deficiency in the intervention of the WHO as a mediating entity that is supposed to provide tools and space for multilateral arrangements in global health. Another factor contributing to weaker GHG effectiveness, identified from the interviews, was the lack of a paired mechanism of governance. As the number of actors within the GHG system grows, the disparity between them also increases, along with their positions and interests (Fidler, 2010). Hence, there is a pressing need for a common ground of understanding in terms of governance in a broader sense, especially health governance. As reiterated by Jecker (2023, p. 410), “recognizing the prospect of global health partnerships to affect change and enhance global health security is the first step toward realizing healthy lives and communities everywhere”.

Regarding China and Brazil's cooperation, the fact that each has its own governance mechanism is underlined. China has its own governance mechanisms for science, technology, innovation, and health, and Brazil has its own. The absence of a paired, agreed-upon, structured, and operational mechanism is perceived as a handicap in the sense that there are ideas, proposals, plans, and programs, but there is no pragmatic tool to account for this complexity of interaction and for the monitoring of projects so far. In this context, the lack of continuity of government actions was referred to (sometimes justified by the switch of political parties leading the government) and exemplified by the discontinuity of human resource teams working with the Chinese innovation ecosystem.

As far as the role of Brazil in GHG is concerned, the interviewees agreed that it plays an important role for three main reasons (the first one was the most frequently mentioned):

1. Set of accredited health entities already deeply rooted in the international and national systems;

2. International references in terms of the quality of clinical trials (e.g., brazil performed phase 2 clinical trials for the coronavac vaccine).

3. Good functioning of its national health system through the “Sistema Único de Saúde” (SUS), with good indicators in areas, such as immunization, maternal and child healthcare, and other specific programs (anti-tobacco, AIDS, etc.), despite a recent regression from 2016 to 2022 motivated by a political disinvestment in SUS.

Regarding the first point, the most common perception of the health agents in this exploratory study was that Brazil has an important installed capacity that can be observed, namely in its program for resuming industrialization, called “Complexo Económico Industrial da Saúde” (Health Economic Industrial Complex). This program constitutes an important instrument that fosters articulation among health services, industry, pharmacies, biotechnology institutions, and research institutes; that is, a comprehensive ecosystem dedicated to the production of health inputs for the Brazilian ecosystem that can later be applied to broader ones.

Regarding the second point, most participating health agents referred to it during the interviews, either linked or not linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical trials play an important role as they are “(…) fundamental for the development of innovative and increasingly personalized treatments, aligned with the individual needs of each patient” (Peig et al., 2020). The optimistic tone of participants as far as clinical trials in Brazil are concerned contrasts with the existing literature, which indicates that Brazil has been losing importance in this field, falling from 17th to 24th place in rankings for clinical trials in the last decade (Peig et al., 2020). This contrast could be further developed in future studies, as there is a consensus on the potential that Brazil presents in this area, the demographic aspects, namely, a wide population with ethnic diversity, and a robust healthcare ecosystem with good sanitation regulations. Indeed, the quality of clinical trials made in Brazil is well supported by legislation, as several authors, such as Gouy et al. (2018, p. 358), state: “Brazil has a well-established ethical and regulatory environment, aligned with universal norms. It is open to reviews, guidance, and clarification of the standards themselves.”

Concerning point three, all interviewees referred to the SUS during their interviews, whereby the SUS is clearly pointed out as an internal way of organizing the Brazilian health services network that could be a model adapted to other developing countries' specificities as well as China's. As described by the majority of participants, it constitutes a structure of stakeholders that supports a health policy decided at the ministerial levels (Health Ministry together with other ministries) and performs many tasks: (i) care in local health units (a highly capillary system that reaches Brazilian territory almost as a whole), (ii) care in hospitals, (iii) sanitary surveillance, (iv) transplant coordination, (v) blood donation coordination, (vi) warranty of treatments not available in the public system, and (vii) help in complying with the consolidated national immunization plan. Although the SUS is part of the Brazilian internal healthcare system, it is a policy that could potentially be applied to other countries, and its scope of action can be expanded to areas that approach health policies and global health issues.

Finally, about the One Health Approach and the Chinese vision of a “Community of Shared Future for Mankind”, the entire group of interviewees considered that both are very conceptual ideas that are scarcely materialized and applied. However, the common perception from the Brazilian side is that China is committed to the United Nations guidelines in general and to those of Agenda 2030 in particular. Therefore, despite the incipient applicability of the concepts for now, some consider it foremost to show the state's ability to conceptually formulate things, which represents a prerequisite for being a good influencer in policymaking. This leads us to the question of soft power and health diplomacy, in which Brazil and China assume a preponderant role, although Brazil has a more consolidated experience in putting health on the political agenda (both in the domestic and foreign policy agenda), according to the perceptions of the majority of the interviewees, perceptions that are confirmed by the literature. Authors Moore (2022) and Almeida et al. (2023), among many others, emphasize the Brazilian prominence in putting health as a priority in agenda setting, even reinforcing “(…) its constitutional emphasis on health access as a human right” (Moore, 2022, p. 6).

3.3 Overview of China–Brazil health relations

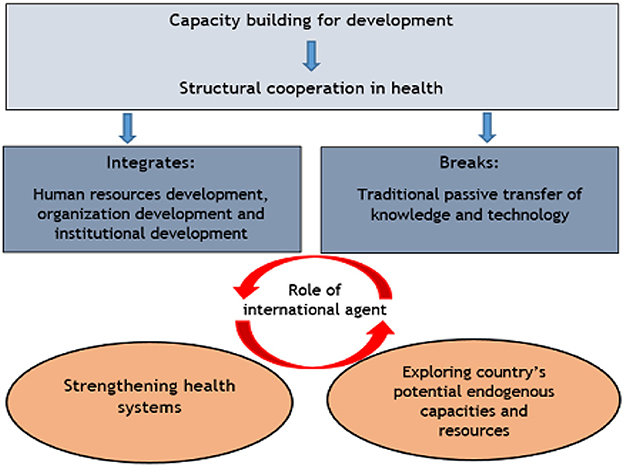

Brazil is a relevant player in the field of health, especially in the global health and health policy arenas. It has been participating in the development of global health by attending a considerable number of international forums and influencing numerous countries, especially in the context of South–South cooperation (Ribeiro and Ventura, 2019; Bianculli et al., 2021). As far as health is concerned, in 2010, Brazil adopted a model called “structuring cooperation for health” represented in Figure 2, which above all consists of breaking the traditional model of unidirectional transfer of knowledge and technology and integrating the human resources development with the organizational and institutional levels of development (Almeida et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Model for structuring cooperation for health (source: Almeida et al., 2010).

Actually, it is part of Brazil's broader foreign policy approach (especially from 2003 to 2010), as it has adopted “a declared ethic of solidarity among developing countries, with an explicit political dimension, which provides a platform for cooperation among countries that want to strengthen their bilateral and multilateral coalitions in order to obtain bargaining power on the global agenda” (Almeida et al., 2023, p. 32). Brazil has been very active in the international health arena, especially by being at the forefront of some health measures that were later adopted by other health systems, including the WHO; for example, the emblematic campaign action against AIDS, universal primary care services, human resources training and allocation, and social determinants of health (SDH) (Almeida et al., 2023). Despite this, since 2018, the commitment to the global health agenda has been affected by a change in Brazil's presidency. Indeed, during the period of Jair Bolsonaro's administration, investments in healthcare and health cooperation were drastically reduced, as pointed out by three of the interviewees (3, 4, 5). When questioned about the relationship between China and Brazil during the pandemic, these three interviewees revealed that it was perceived as almost inexistent: “Bolsonaro's international relations with the other presidents were very complicated. The fight against the pandemic was tough, he didn't believe in science. If there was an attempt by China to help, it was stopped by the government because it wasn't brought to our notice” (Interviewee 3, Head of Laboratory).

Topics such as the social determinants of health and Agenda 2030 for health were discussed during the interviews. China is perceived as very cautious about whatever guidelines come from institutions belonging to the sphere of the United Nations, highlighting the fact that the majority of health problems associated with SDH are problems of a lack of infrastructure or deficiencies. China attributes great importance to this lack of infrastructure, fulfilling these gaps in many developing countries, especially in the African continent, through the development of HSR projects. Interviewee 1 (Advisor and Head of Global Communication on Innovation) even mentioned “(…) it does not matter whether a country has a unique healthcare system or even top R&D in oncology for example, if it has not, at least, a basic sewage system or access to drinkable water or a road that leads to basic health units or hospitals”. In recent decades, China has moved from being an aid recipient to a prominent non-conventional donor of global development aid (Shajalal et al., 2017), not only in its capacity to build health facilities worldwide but also in terms of supplying medical equipment or training medical teams. Specifically, during the COVID-19 pandemic, China's health assistance remained coherent with previous trends in its foreign policy in the current environment of tensions with the West while maintaining a positive stance in the Global South (Cabestan, 2022; Fuchs et al., 2022).

Focusing on the relationship between China and Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic, we observed a duality of positions with some divided opinions among the interviewees. On the one hand, they do not perceive any kind of reinforcement of cooperation with China during or because of the pandemic, and this fact is mostly attributed to the political scenario and, particularly, to the Brazilian presidency at that time. According to most of the interviewees (1, 2, 3, 4), during the leadership of Jair Bolsonaro, it was very tough for Brazilian health institutions to work toward the most effective fight against the virus because the resources were not allocated to science, education, or health. They stated that decision-makers tried to mitigate central and presidential decisions, but, overall, despite the efforts, it always created an environment of discouragement and made the execution of the tasks more difficult. On the other hand, they referred to the fact that most of the Brazilian population was immunized with the Chinese vaccine, as it was the first to be available to them.

The existence of diverse and dispersed cooperative actions between Brazil and China in the health sector, both at the federal and state levels, mainly driven by local or regional institutions in both countries, was another particularity of China–Brazil health cooperation that was revealed during the interview process. However, there is a perception of a lack of articulation between these initiatives, as no observable follow-up actions have been designed or implemented to monitor the effects of such partnerships.

Finally, one question was posed specifically regarding the interviewees' perceptions about the recent signature (April 2023) on an MoU between China and Brazil, particularly Fundação Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz, for the creation of the Centro Sino-Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Prevenção de Doenças Infeciosas (Sino-Brazilian Center for Infectious Disease Research and Prevention). According to one of the interviewees (Interviewee 1, Advisor and Head of Global Communication on Innovation), who was part of the team responsible for the MoU of this joint project, the Center brings closer the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and Fiocruz, which are two public institutions that care about themes of public health. The main goals are as follows:

- The opening of new lines of joint research in the areas of emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases, those that are more lethal among the most vulnerable populations (then, it can expand to other types of diseases or areas such as genomics or food safety).

- The development of technologies for testing and diagnosis (to be cured, people need to know first if they are sick and what pathologies they have).

- The development of medicines and other health-related products that can enter the Sistema Único de Saúde and benefit the Brazilian population.

- The development of Sino-Brazilian vaccines that could become global public goods (more ambitious goals).

Apart from these main targets, other hopes were pointed out during the interview regarding the role they expect the Center to play: (i) enhance the communication process between the agents, (ii) enhance academic cooperation, functioning as a catalyst for joint research projects and staff mobility, and (iii) function as a hub to attract companies operating in the field of technological innovation in health. For the entire set of interviewees, if well-coordinated, this joint project represents an added value for the global health community and for the Brazilian population. Access to processes of technology transfer was the most emphasized topic, namely, access to new biomedical equipment and training on how to operate with it (Chinese health teams reveal great expertise in this) and elements that can strengthen Brazil's health services network and bring important benefits to the Brazilian healthcare system, deriving from such cooperation with China. In fact, all interviewees perceived China as a key player in medical, biomedical, pharmaceutical, and health technology equipment, positioning it as a leader owing to its manufacturing capacity, presence in global supply chains, and cognitive mastery of the mode of operating the devices.

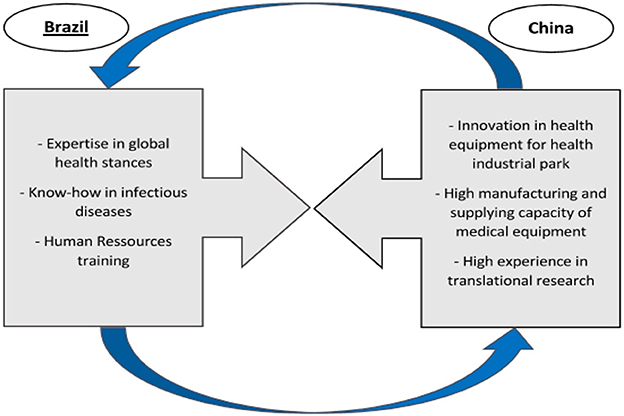

Consequently, when questioned about the main areas of cooperation between China and Brazil, all interviewees responded that the relationship is essentially based on the transference of what each side has to offer (see Figure 3), that is, from the Chinese side, inputs related to technology, innovative medical equipment, and medicines and drugs due to the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that China produces for the entire world (second largest producer after India, 834 API producers in China against only 13 in Brazil in 2023). On the Brazilian side, there is a transference of knowledge and expertise, especially in the field of global health and infectious diseases (containment, treatment, and surveillance).

The same pattern of collaboration between the two was identified in the interviews, that is, a collaborative partnership based on filling an existing gap: Brazil's difficulties in developing translational research, that is, the one that lies between basic research (Phase 1) and final research (Phase 3), for example, the process of transforming a molecule into a drug. This is due to Brazil's lack of innovative technological development and access to equipment, areas in which China is at the forefront, producing high quality and being able to fill this gap. Despite being a commercial partnership, it is highly relevant to both sides owing to its complementary components. In addition to this specific type of cooperation, academic exchanges focusing on specific projects linked, for example, to genomics or telemedicine, can be quite fruitful, as mentioned by interviewees 1, 2, and 3. However, cooperation with China in areas such as health policies and health management was perceived as less beneficial, as the inquired agents did not perceive Chinese teams as experimenting on these specific topics.

Regarding the fields of cooperation, one of the infectious diseases stands out from the others, but all interviewed researchers hope that it can be expanded to other diseases, namely, non-communicable diseases. Another field that was identified as promising was food sciences as a whole but concentrated particularly on topics, such as food safety and food production technology, which are areas identified as potentially benefiting from joint collaborative efforts.

To summarize, the main assumptions deriving from the literature review are corroborated by the insights of health agents, as evidenced by the analysis made from the content of the interviews. We can infer that:

- Despite the dimension of the BRI, outside of the economic, political, and international relations realm, few agents have a deep knowledge of its achievements, and in the health sphere, few joint projects are perceived as being carried under the Health Silk Road scope;

- Brazil and China's cooperation in health is based on an exchange of assets in which each stakeholder contributes with its best ones. It can be largely extended beyond infectious diseases and surveillance topics to areas that are not yet very developed, such as non-communicable diseases, cancer treatment, and telemedicine;

- Latin America and specifically Brazil have a long history of participation in GHG from which China can benefit as well in order not to stand only in a rhetorical plan of “Shared Community for Mankind”, but to have a more proactive role in GHG architecture;

- Lack of political will is the main reason pointed out in the literature for the failure of some mechanisms of health governance, and the example of Bolsonaro's administration in Brazil was frequently mentioned as a real and recent example.

4 Final considerations

This exploratory study aimed to shed light on health cooperation between China and Brazil under the BRI framework, particularly through the HSR. It assesses the perceptions of health researchers from credited public institutions in Brazil, as a representative country of the BRICS and the Global South, in terms of the main areas of partnerships, mutual benefits, patterns of cooperation, health gains for national populations, and the global health community, as well as possible future trends.

To the question, “Does Brazil benefit from health partnerships with China, specifically under the Health Silk Road, despite not having formally joined the BRI” considering that Brazil has not yet formally signed up as a member of the BRI, the current partnerships established are not directly linked to these initiatives. Brazilian health agents are generally unaware of the BRI contours and, consequently, HSR. Hence, we can infer that the logic behind the specific case of Sino-Brazilian joint health projects is not attached to the BRI, contradicting the literature that states that countries aligning with the BRI are more likely to receive Chinese investment (Cabestan, 2022; Fuchs et al., 2022). This constitutes an interesting topic for future research to understand the reasons that might underlie the different perceptions that come from Brazil (e.g., Is Latin America facing a different Chinese approach than African countries?).

To the question, “Which were the privileged health areas of implementation and what are the gains?” we observe that the field of infectious diseases is the most relevant, mostly because of the expertise of both countries in this area and the fact that they both have large populations facing many communicable disease outbreaks (Ebola, Zika, SARS, etc.). The most evident gains are Brazilian access to innovative health-related equipment (genome sequencers, testing kits, etc.) and drugs provided by China. Their cooperation under the BRICS arrangement seems to be perceived by health agents as more potentially fruitful, despite the heterogeneity of BRICS countries in terms of their individual national health system maturity, internal strengths and weaknesses, and disease burden. Within BRICS, China and Brazil are the most cooperative countries in terms of health-related issues.

The model of cooperation identified is based on the theoretical premise that each stakeholder contributes their best assets: from the Chinese side, its production and supply capacity, especially of medical equipment, testing equipment for diagnostics, innovative technologies for the health industrial complex, active pharmaceutical ingredients, drugs, and the ability to develop translational clinical research. On the Brazilian side is its great expertise in global health, being part of many international spaces of debate, and its great knowledge in leading infectious diseases, immunization programs, and clinical trials, as well as expertise that can be passed on to its Chinese counterparts. Thus, they are both actors in health who have common challenges to face but, simultaneously, complementary inputs that can benefit both countries in terms of health gains for their own national populations.

According to the literature review and reinforced by the insights coming from the content analysis of the interviews, the perceived health gains under the BRI and HSR projects tended to be more impressive in low- and middle-income countries, especially via South–South cooperation. Concerted mechanisms of health governance should be established to enhance its performance, effectiveness, and efficacy, and above all, to convert political will into concrete actions with practical results.

New potential research topics were identified from this exploratory research to reflect on the impacts of HSR and Chinese Health Assistance in the Global South. We suggest in-depth research on the influence of the health sovereignty concept on the global health performance of countries from the Global South (not limited to China and Brazil) and research dedicated to understanding what really happens on the ground if Chinese health cooperation is not “strings-attached” (as suggested by Brazilian health agents' insights), in contrast to what is suggested by existing literature and other case studies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request and with the consent of participants in this study.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in the study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

AS developed the conceptualization, research design, empirical study, literature review, the entire compilation of the information gathered, and the scientific writing of the article. CR contributed to the validation of the interview scripts and data treatment, as well as the revision of the drafts, and the final version of this manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a doctoral research grant with reference no. SFRH/BD/151133/2021 from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., in partnership with Macau Scientific and Cultural Center, I.P., in Lisbon, and was supported by the Research Unit on Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policies (UIDB/04058/2020 + UIDP/04058/2020) funded by national funds through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and thank the health researchers who provided their consent for the interviews, which constituted the empirical basis of this study. Without their contributions, it would have been impossible to obtain valuable insights for this study. The authors thank their colleagues and researchers, Carlos Gonçalves and Professor Célia Almeida, whose careful reading enabled improvements to this document. The authors also thank PICTIS - Plataforma Internacional para Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação em Saúde and its laboratories for their collaboration and support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acharya, S., Barber, S. L., Lopez-Acuna, D., Menabde, N., Migliorini, L., Molina, J., et al. (2014). BRICS and global health. Bull. World Health Org. 92, 386–386A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.140889

Alden, C., and Vieira, M. A. (2005). The new diplomacy of the South: South Africa, Brazil, India and trilateralism. Third World Quart. 26, 10771095. doi: 10.1080/01436590500235678

Almeida, C., Pires de Campos, R., Buss, P., Ferreira, J., and Fonseca, L. (2010). A concepção brasileira de cooperação Sul-Sul estruturante em saúde. RECIIS – R. Eletr. de Com. Inf. Inov. Saúde. Rio de Janeiro 4, 25–35. doi: 10.3395/reciis.v4i1.343pt

Almeida, C., Santos Lima, T., and de Campos, R. (2023). Brazil's foreign policy and health (1995–2010): A policy analysis of the Brazilian health diplomacy – from AIDS to ‘Zero Hunger'. Saúde debate 47, 136. doi: 10.1590/0103-1104202313601i

Azevedo, V., Carvalho, M., Costa, F., Mesquita, S., Soares, J., Teixeira, F., et al. (2017). Interview transcription: conceptual issues, practical guidelines, and challenges. Revista de Enfermagem Referência. IV Série. 14, 159–168. doi: 10.12707/RIV17018

Bianculli, A., Hoffmann, A., and Nascimento, B. (2021). Institutional overlap and access to medicines in MERCOSUR and UNASUR (2008–2018). Cooperation before the collapse? Global Public Health. 17, 363–376. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1867879

Birn, A.-E. (2011). Reconceptualización de la salud internacional: perspectivas alentadoras desde América Latina. Rev Panam Salud Publica 30, 101–105.

Birn, A.-E., Muntaner, C., Afzal, Z., and Aguilera, M. (2019). Is there a social justice variant of South-South health cooperation? A scoping and critical literature review. Glob. Health Action12, 1621007. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1621007

Bucholtz, M. (2000). The politics of transcription. J. Pragmat. 32, 1439–1465. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00094-6

Cabestan, J. P. (2022). The COVID-19 health crisis and its impact on China's International Relations. J. Risk Finan. Manag. 15, 123. doi: 10.3390/jrfm15030123

Chow-Bing, N. (2020). Covid-19, Belt and Road Initiative and the Health Silk Road: Implications for Southeast Asia. Jakarta: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) Indonesia Office. Available online at: https://asia.fes.de/news/health-silk-road-pub (accessed June 29, 2023).

DeJonckheere, M., and Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Com. Health. 7, e000057. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

Fidler, D. (2010). The Challenges of Global Health Governance. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations.

Fuchs, A. L., Kaplan, K., Kis-Katos, S. S., Schmidt Turbanisch, F., and Wang, F. (2022). Tracking Chinese Aid through China Customs: Darlings and Orphans After the COVID-19 Outbreak. Kiel Working Paper 2232. Kiel: Kiel Institute for the World one of Economy.

Gills, B. (2010). Going South: capitalist crisis, systemic crisis, civilisational crisis. Third World Quart. 31, 169–184. doi: 10.1080/01436591003711926

Girado, G. (2018). “El despliegue transcontinental de la iniciativa China. El caso latinoamericano” in China, América Latina y la geopolítica de la Nueva Ruta de la Seda, eds S. Vaca Narvaja and Z. Zhan (Remedios de Escalada: UNLa).

Gouy, C., Porto, T., and Penido, C. (2018). Evaluation of clinical trials in Brazil: history and current events. Rev. Bioét. 26, 254. doi: 10.1590/1983-80422018263254

Gray, K., and Gills, B. (2016). South–South cooperation and the rise of the Global South. Third World Quart. 37, 557–574. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1128817

Harris, J. (2005). Emerging Third World powers: China, India and Brazil. Race Class 46, 7–27. doi: 10.1177/0306396805050014

Herrero, M. B. (2017). Moving towards a South-South International Health: debts and challenges in the regional health agenda. Revista Ciencia e Saude Coletiva 22, 2169–2174. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232017227.03072017

Herrero, M. B., and Belardo, M. B. (2022). Salud internacional y salud global: reconfiguraciones de un campo en disputa. Revista Relaciones Internacionales 95, 54–82. doi: 10.15359/ri.95-2.3

Herrero, M. B., Loza, J., and Belardo, M. (2019). Collective health and regional integration in Latin America: An opportunity for building a new international health agenda. Rev. Global Public Health. 14, 835–846. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1572207

Jakovljevic, M., Potapchik, E., Popovich, L., Barik, D., and Getzen, T. E. (2017). Evolving health expenditure landscape of the BRICS nations and projections to 2025. Health Econ. 26, 844–852. doi: 10.1002/hec.3406

Jauregui, J. (2020). Latin American countries in the BRI: challenges and potential implications for economic development. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 10, 348–358.

Jecker, N. (2023). “Global health partnerships and emerging infectious diseasesm” in Handbook of Bioethical Decisions, eds E. Valdés and J. A. Lecaros. Volume I: Decisions at the Bench (Springer Verlag), 397–413.

Johnston, A. I. (2008). Social States: China in International Institutions, 1980-2000. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Johnston, A. I., and Johnston, A. I. (2013). Is China a status quo power? Int. Secur. 27, 5–56. doi: 10.1162/016228803321951081

Kickbusch, I. (2014). BRICS' contributions to the global health agenda. Bull. World Health Org. 92, 463–464. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.127944

Kickbusch, I., and Reddy, K. S. (2015). Global health governance - the next political revolution. Public Health 129, 838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.014

Lancaster, K., Rubin, M., and Hooper, M. R. (2020). Mapping China's Health Silk Road. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations.

McBride, J., Berman, N., and Chatzky, A. (2023). China's Massive Belt and Road Initiative. Council on Foreign Relations. Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed June 29, 2023).

McKee, M., Marten, R., Balabanova, D., Watt, N., Huang, Y., Finch, A. P., et al. (2014). BRICS' role in global health and the promotion of universal health coverage: the debate continues. Bull. World Health Org. 92, 452–453. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.132563

Moore, C. (2022). BRICS and Global Health Diplomacy in the Covid-19 Pandemic: Situating BRICS' diplomacy within the prevailing global health governance context. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 65, 222. doi: 10.1590/0034-7329202200222

Noesselt, N. (2022). Debates on Multilateralism in the Shadow of World Order Controversies – Visions of Global Multilateralism Could Overwrite the Concept of Multipolarity. Frankfurt: Goethe Universitat.

Oliveira, G. L. T., Murton, G., Rippa, A., Harlan, T., and Yang, Y. (2020). China's belt and road initiative: views from the ground. Polit. Geograp. 82, 102225. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102225

Park, A., Tritto, A., and Sejko, D. (2021). The belt and road initiative in ASEAN – overview. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3932776

Peig, D., Fujioka, W., Cardoso, F., and Rebelo, F. (2020). The Importance of Clinical Research to Brazil. São Paulo: Infarma – Associação da Indústria Farmacêutica de Pesquisa.

Power, M. (2011). Angola 2025: The future of the ‘world's richest poor country' as seen through a Chinese rear-view mirror. Antipode 44, 993–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00896.x

Ribeiro, H., and Ventura, D. F. L. (2019). Health diplomacy and global health: Latin American perspectives. Revista de saúde publica 53, 37. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2019053000936

Riggirozzi, P., and Tussie, D. (2012). The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism: The Case of Latin America. Dordrecht: Springer.

Sacchetti, L., and Rovere, M. (2011). La salud pública en las relaciones internacionales. Cañones, mercancías y mosquitos. Editorial El Ágora.

Santiago, A. (2021). A Rota da Seda da Saúde e o seu papel no âmbito da governança global em saúde. Aveiro: Rotas a Oriente – Revista de estudos sino-portugueses.

Santiago, A. (2022). Chinese Health Strategy: A Tool towards Global Governance. Singapore: The Palgrave Handbook of Globalization with Chinese Characteristics, Palgrave Macmillan.

Shajalal, M., Xu, J., Jing, J., King, M., Zhang, J., Wang, P., et al. (2017). China's engagement with development assistance for health in Africa. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2, 24. doi: 10.1186/s41256-017-0045-8

State Council Office of the PRC (2014). China's Foreign Aid 2014. Available online at: http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/ndhf/2014/Document/1375014/1375014_3.htm (accessed June 29, 2023).

Tambo, E., Ugwu, C. E., Guan, Y., Wei, D., and Xiao-Nong, Z. (2016). China-Africa health development initiatives: benefits and implications for shaping innovative and evidence-informed national health policies and programs in Sub-saharan African countries. Int. J. MCH AIDS 5, 119–133. doi: 10.21106/ijma.100

Tan, X., Liu, X., and Shao, H. (2017). Healthy China 2030: a vision for health care. Value Health Reg. Issues.12, 112–114. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.04.001

Taylor, I. (2009). ‘The South Will Rise Again'? New alliances and global governance: the India–Brazil–South Africa Dialogue Forum. Politikon 36, 45–58. doi: 10.1080/02589340903155393

Vadlamannati, K. C., and Jung, Y. (2023). The political economy of vaccine distribution and China's Belt and Road Initiative. Bus. Polit. 25, 67–88. doi: 10.1017/bap.2022.26

Vance, C., Mafla, L., and y Bermudez, B. (2016). La cooperación Sur-Sur en Salud: la experiencia de UNASUR. Línea Sur Revista de Política Exterior 3, 89–102.

World Health Organization (2017). South-South and Triangular Cooperation. WHO. Available online at: https://www.who.int/country-cooperation/what-who-does/south-south/en/ (accessed June 29, 2023).

Keywords: Belt and Road Initiative, Health Silk Road, Global South, health agents, China-Brazil health cooperation

Citation: Santiago A and Rodrigues C (2023) The impact of the Health Silk Road on Global South countries: insights from Brazilian health agents. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1250017. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1250017

Received: 29 June 2023; Accepted: 17 October 2023;

Published: 23 November 2023.

Edited by:

Alvin Camba, University of Denver, United StatesReviewed by:

Cintia Quiliconi, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences Headquarters Ecuador, EcuadorStefanie Kam, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Copyright © 2023 Santiago and Rodrigues. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anabela Rodrigues Santiago, YW5hYmVsYS5zYW50aWFnb0B1YS5wdA==

Anabela Rodrigues Santiago

Anabela Rodrigues Santiago Carlos Rodrigues

Carlos Rodrigues