- Faculty of Social Sciences, Economics, and Business Administration, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

This article analyzes the global development of democracy since the 1990s. The theoretical introduction is followed by a descriptive analysis of several indices of political support based on survey results for 89 countries that participated at least twice in the World Values Survey (WVS) or the European Values Study (EVS). The analysis focuses on emancipative value orientations measured by Welzel's Choice Index and several indicators of political support. The scores of these indicators are broken down by five regime types and seven world regions. The results confirm that the global decline of democratic quality since the mid-2000s has not been as dramatic as the pessimistic analyses of Freedom House and the V-Dem project have claimed. It has primarily taken place in a limited number of populous countries on which these publications have focused. When countries are treated equally, the quality of democracy has remained remarkably stable since the early 1990s. Emancipative values are globally on the rise, but their increase has been considerably higher in the established democracies. This supports the skeptical argument that they cannot be considered as the major cause of the third wave of democratization. The descriptive analysis is complemented by regression analyses for confidence in regime institutions and support for democracy as dependent variables. The evaluation of democratic regime performance is the strongest predictor of confidence in regime institutions. An intrinsic conception of democracy and the importance assigned to living in a democracy have the strongest influence on support for democracy. Emancipative value orientations have a minor influence on political support even in consolidated democracies. Finally, the analysis does not confirm the suspected relationship between the different levels of political support. Easton's theory of political support assumed that they mutually influence each other via a generalization of experiences or an overflow of values. Instead, it seems that confidence in regime institutions and support for democracy follow different cognitive logics.

1 Introduction

The following analysis has been inspired by my long-term association with a comparative project on democratization and democratic consolidation under the leadership of Van Beek (2022). It starts out from the assumption that the concept of legitimacy is applicable to all types of regimes regardless of their specific character. Wiesner and Harfst's (2022) decision to include the realization of fundamental democratic principles in the concept would unnecessarily diminish its analytical scope. This would be appropriate only for studies dealing exclusively with democratic countries whose legitimacy claims are based on their democratic credentials (e.g., Lipset, 1960, Chapters II and III; Kriesi, 2013). Otherwise, it would preclude comparisons of legitimacy across different regime types.

In his seminal work on “The Ruling Class” of 1939, Mosca (1980) emphasized that the stability of regimes depends on the ability of their elites to gain and sustain legitimacy. He argued that legitimacy primarily depends on the elites' ability to devise and find acceptance for a legitimizing narrative, a “political formula.” This implies that “ruling classes do not justify their power exclusively by de facto possession of it but try to find a moral and legal basis for it, representing it as the logical and necessary consequence of doctrines and beliefs that are generally recognized and accepted” (1980, p. 70).

Empirical legitimacy research assumes that citizens are the “ultimate arbiters of legitimacy” (Kriesi, 2013, p. 614). Most studies have used the terms legitimacy and political support interchangeably by using Easton's concept of political support for assessing the degree of political legitimacy. Easton considers political support as constituting a “reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed” (1975, p. 444). It is based on citizen evaluations of the political system's performance and value orientations as measures of legitimacy.

2 Value orientations, political support, and democracy

Studies on the impact of socioeconomic structure, cultural traditions, and value orientations on the development of democracy have a long tradition in the social sciences. Classic modernization theory (e.g., Lipset, 1960; Vanhanen, 2003) assumes that industrialization fostered the spread of democracy because it implied a diversification of occupational structures and an increasing division of labor, thereby undermining traditional hierarchies of authority and liberating people from the restraints imposed by the customs and norms prevailing in traditional societies.

Inglehart's (1971, 1977) theory of value change has complemented this macro-theoretical approach by providing a micro-level explanation. He argued that the economic growth enabled by industrialization improved the living conditions in industrial societies and fostered a gradual change in individual value priorities from materialist to postmaterialist values. These postmaterialist values have in turn increased demands on the political system to provide more political participation rights for ordinary citizens. Over time, Inglehart – later in cooperation with Christian Welzel – continued to develop these ideas into a comprehensive theory of human development. The theory holds that the rise of emancipative values constitutes a major driver of democratization around the globe (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Welzel, 2013; Inglehart, 2018).

Welzel (2021) has repeatedly claimed that the global rise of emancipative value orientations undermines the legitimacy of non-democratic regimes and will inevitably result in ever more democratic transitions because they produce regime-vs.-culture “mismatches” in authoritarian regimes (Welzel et al., 2019). Therefore, “a growing gap between regime and culture will unavoidably reshape the context that political actors must navigate.” An emancipatory cultural context makes countries “ripe for the rise of counterelites, regime-challenging alliances, and popular movements that seek to bring the regime more into line with the underlying, freedom-valuing culture” (2021, p. 133). Authoritarian leaders “can only slow but not stop the emancipative effects of modernization” (ibid., p. 133, 134).

This claim has been increasingly challenged in recent years. The annual reports of Freedom House (2023) and of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute have called it into question by documenting a steady decline of liberal democracy over the past two decades. V-Dem's 2023 report even shows that democracy has declined to its 1986 level, implying that 72% of the world's population now live in autocracies (V-Dem Institute, 2023a).1

In response to an article by Welzel (2021) entitled “Why the Future is Democratic,” Foa et al. (2022, p. 149, 150) emphasized the inherently conditional nature of human history. They argued in particular that most of the rise of emancipative values over the past decade “has occurred in countries that are already democratic.” Moreover, they criticized Welzel's basic expectation as implausible: “Why should changing attitudes regarding abortion, divorce or gender rights predict democratic transitions?” Finally, they disputed that Welzel's index of emancipative values forms “a coherent and culture-invariant array of convictions that are of core significance to democracy itself.”

It is obvious that Welzel's empirical results, while suggestive, are insufficient proof of political causality. They are based on macro-level correlations and fail to take into account the complexity of regime changes that are necessarily characterized by a high degree of political volatility and country-specific constellations of individual and collective actors with conflicting political interests. These actors are motivated not only by their value orientations, but also by their perception of changes in the domestic and international balance of power, their ability to strike bargains with other actors, and their choice of strategies and tactics. Therefore, it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict which actors will eventually prevail.

Moreover, history has regularly disproved monocausal theories assuming a linear development of certain sociopolitical trends because they tend to underestimate the complexity of modern societies and in particular the resilience of traditional ways of life. The late Ronald Inglehart acknowledged this by discussing the emergence of a cultural backlash among political traditionalists in the liberal democracies (Inglehart, 2018, Chapter 9; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Right-wing populist movements and parties in established democracies have nurtured such resentments against the so-called new politics by criticizing changing gender roles, the introduction of homosexual marriage, policies of fighting climate change, and the immigration of refugees and economic migrants. This is frequently combined with a scathing criticism of the Western model of democracy for not being capable of coping with major political problems because decision-making processes are too cumbersome and time-consuming. Such movements are not necessarily anti-democratic, but they contribute to delegitimating liberal democracy.

Over the last years, autocratic regimes, in particular China and Russia, have not only tightened their grip on their own societies but have been engaged in anti-democratic propaganda (Walker, 2022; Walker and Ludwig, 2022).2 Therefore, liberal democracy has come under attack from several sides which opens up the question whether this has had an impact on its reputation.

The following analysis has a more modest purpose. It will take up the doubts raised by Foa et al. (2022) about the causal impact of emancipative value orientations on democratizations and study the relationship between political value orientations and various indicators of political support in a broad spectrum of countries with different regimes.

Social scientists have frequently assumed that democracies enjoy more political support than autocracies. This expectation is primarily based on the statistical association between socioeconomic development and democracy. Lipset (1960) assumed that democracies which are capable of producing political stability, economic growth, and increasing standards of living, will be able to gain and sustain political legitimacy (Ch. 2). A recent comparative analysis by Acemoglu et al. (2019, p. 96/7) confirms this assumption and argues that this is due to “many complementarities between democratic institutions and proximate causes of economic development.” It is an open question, however, whether the better economic performance of liberal democracies is honored by its citizens with a higher level of political support.

Lipset (1960) further argued that both the economic and political performance of democracy are important for generating political legitimacy. A lack of economic development as well as a recession will reduce standards of living. Citizens and economic enterprises who have to pay bribes for receiving government services will feel subjected to bureaucratic arbitrariness. Finally, a lack of governmental stability will impair the legitimacy of a regime. Due to unreliable support by their own party or their coalition partners, parliamentary governments under the permanent threat of a vote of non-confidence are unable to pursue the policies they promised voters in the election. All of these factors are important for the legitimacy of both democratic and non-democratic regimes.

In Easton's theory, different types and levels of political support are supposed to mutually influence each other. A good economic and political performance may engender support through a generalization of experiences. Vice versa, a broad consensus on basic regime values may stabilize a regime that has to cope with a crisis through an overflow of values (Easton, 1975; Fuchs, 2007; Mauk, 2020, p. 28, 112). The latter implies that value change may contribute to a spread of democratic value orientations and improve the consolidation chances of young democracies even where citizens lack personal experience with democracy. Therefore, widespread support for democracy among both elites and citizens may constitute a precious resource facilitating democratization and accelerating democratic consolidation.

Over the past two decades, three major global crises, the economic and financial crisis of 2008, increasing international migration due to (civil) wars, and the Corona pandemic have seriously impaired the economic development and political stability in many countries, especially of the Global South. They have been responsible for the surge and electoral success of authoritarian political parties and populist leaders denouncing democracy as failing to fulfill its promise of improving the lives of ordinary people.

At the same time, the spectacular economic success of China seems to suggest that economic development does not necessarily presuppose a western-style liberal democracy. The validity of this assumption is disputed by Acemoglu et al. (2019, p. 472, 473) however, who argue that such economic success of autocratically governed countries is usually short-lived and not sustainable unless it is accompanied by a “balance between the state and the market” and “new ways in which society is empowered to monitor and control the state and the elites.”

Recent developments in China, Russia, and Turkey confirm their argument: An initial opening of opportunities for private enterprises and a political liberalization helped achieving amazing levels of economic growth. They seemed to prove that economic growth does not necessarily require a democratic system of government and contributed to increase the legitimacy of their governments. After a couple of years, however, once the political leaders started realizing that citizens and private enterprises used their newly won economic and political liberties to challenge their autocratic rule, they reintroduced new restrictions on economic and political freedoms which increasingly threatened to end the economic upswing. Initially, citizens may fail to realize the gradual economic downturn and the return of repressive policies. Therefore, the belief in the autocratic regime's ability to secure continued economic growth and legitimacy can be retained for some time. Once citizens realize that they have been fooled, it may already be too late to oppose a further autocratization.

These considerations call for a longitudinal analysis for ascertaining whether support for emancipative values and democracy have increased globally as the theory of value change posits or whether the recent wave of autocratization observed by V-Dem and Freedom House has led to their stagnation or even reversal.

3 Data base and operationalization of indicators

3.1 The integrated values surveys (IVS) 1981–2022

The data analysis is based on the data of the Integrated Values Surveys (IVS). The IVS combines the trend files of the seven waves of the World Values Survey and the six waves of the European Values Study for the period 1981–2022.3 Both are replicative surveys including a large number of identical questions. Merging the two data files increases the global coverage of countries. It provides the best available data base for a comparative and longitudinal analysis of political support.

The combined data file was slightly modified for the analysis. Because one major purpose of the analysis is to study changes over time, countries that participated only once in the surveys were excluded. Those that participated in just two waves were included only if they had participated in at least one of the last two survey waves. A small number of respondents below the minimum age of 18 were excluded for the sake of comparability. With the exception of Hong Kong, non-sovereign territories and small countries were excluded: Andorra, Luxembourg, Macau, Northern Ireland, and Puerto Rico. These exclusions reduced the overall number of countries from 116 to 89 and the number of respondents from 647,188 to 607,506.4

To ease the legibility and interpretation of the scores included in the tables and figures, all original scores were rescaled to a range from 0 to 1. An equilibrated weight was applied for the statistical analysis. It corrects for deviations from the actual sociodemographic composition of the population within each country and standardizes the number of respondents per country and wave to 1,000. Therefore, all countries have the same numerical weight regardless of their population size. The results reflect the diversity of the countries rather than their share of the world population.

3.2 Emancipative value orientations

The theory of value change posits that value change is a crucial factor in driving democratization. Welzel's (2013) Index of Emancipative Values (EVI) is the centerpiece of his theory of human development. It is a combination of four sub-dimensions: “Autonomy,” “Equality,” “Choice,” and “Voice.” The index has been criticized by methodologists for showing low construct validity.5 Sokolov (2018) found sufficient construct validity across different cultural zones only for the two sub-dimensions choice and equality. The Choice Index is based on three items that measure the acceptance of divorce, abortion, and homosexuality. The Gender Equality Index is based on three items measuring the degree to which unequal treatment of women in education, jobs, and politics was rejected. An analysis of the reliability of the EVI's sub-dimensions for the latest survey wave confirmed Sokolov's results. Since the Choice Index with a reliability coefficient of α = 0.85 receives lower scores and is more demanding than support for gender equality (α = 0.74), it will be used as a proxy for assessing emancipative value orientations.

3.3 Indicators of political support

The operationalization of political support relies on the reformulation of Easton's theory of political support by Fuchs (2007), Fuchs and Klingemann (2009), and Klingemann (2018). It distinguishes between specific and diffuse support, depending on whether support is based on the performance of the current government or on the generalized experience with the functioning of the political system. It also distinguishes three objects of support that represent three levels of generality: Process, structure, and values. Evaluations of political authorities are based on perceptions of the effectiveness and trustworthiness of the current government and measure specific support at the process level. Support for regime institutions is based on the generalized experience with their long-term performance and measures support for the structural level. Support for the political values expressed in the regime's constitutional design and its claim to legitimacy is furthest removed from the performance of the current government and least susceptible to sudden changes. Unfortunately, the IVS surveys have not regularly asked for an evaluation of political authorities. Therefore, specific political support could not be included in the analysis.

Two questions can be used as indicators of support for the structural level of the regime. The first is confidence in regime institutions. It can be interpreted as a generalized assessment of the regime's political performance (Klingemann, 1999, p. 46–54). The index Support for Regime Institutions is similar to Mauk's (2020, p. 78–81) index of political support that combines confidence in government, parliament, the police, and the armed forces. Confidence in the military was replaced by confidence in the public administration, however, because most citizens have more regular contact with the latter. Additionally, confidence in the judicial system (the courts) was included because it is a crucial institution protecting citizen rights. Confidence in these five institutions has a high degree of scalability with a reliability score of Cronbach's α of 0.85. A principal component analysis confirmed the unidimensionality of these evaluations. The first component has an Eigenvalue of 3.15 and explains 62.9% of the total variance. The index was calculated as mean score of the five variables. Its correlation with Mauk's index is r = 0.80, so both indices tap the same aspect of political support.

Another indicator of support for the political system is the evaluation of the democratic quality of the regime. This is assessed with the question “How democratically is this country being governed today?” Since democracy enjoys broad support around the globe and because today even autocracies pretend to be democracies, this question produces meaningful answers even in autocratic countries (Brunkert, 2022). Rather than providing realistic assessments of the actual democratic quality of the regime, the answers can be interpreted as indicating how well the political system fulfills the respondents' expectations regarding individual freedoms and participation rights. The correlation coefficient of this variable with confidence in regime institutions is r = 0.39, so both indicators measure different but related aspects of satisfaction with the regime. Mauk (2020, Chapter 5) assumed confidence in regime institutions to be the more general measure of regime support and included the evaluation of democratic regime performance as an independent variable in her explanatory model. This decision seems justified and was applied here, too.

Two survey questions asked for an evaluation of democracy. The first required independent ratings of three different regime types: Autocracy, military regime, and democracy. The second asked for the importance attributed to living in a democracy. Surveys have regularly shown that democracy tends to receive uniformly positive ratings. These high scores do not necessarily indicate a strong commitment to a democratic system of government, however, especially in countries where people have never lived under democratic conditions. At the same time, in many countries autocratic regimes receive fairly high ratings, too. Therefore, several authors argued that it is necessary to consider not only how people evaluate democracy but also how they evaluate autocracy (Fuchs, 2007, p. 167–169; Diamond, 2008, p. 33).

A commitment to democracy presupposes that respondents are aware of the difference between a democratic and an autocratic regime. Therefore, an index Support for Democracy was constructed by subtracting the higher of the two scores provided for the two non-democratic regime types from the score of democracy. The index has a high discriminatory power and shows consistent and plausible statistical associations with other indicators.

3.4 Intrinsic conception of democracy

Almond and Verba (1989) first introduced the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental support for democracy. They argued that support that is primarily based on a good economic performance of the own country constitutes a shaky basis of loyalty. “In particular, there appears to be a need for a balanced affective orientation to politics; or rather, there must be a balance between instrumental and affective orientations” (1989, p. 354). Empirical studies have supported the relevance of an intrinsic conception as important for the consolidation and stability of democracy (e.g., Bratton and Mattes, 2001, p. 437; Chapman et al., 2024, p. 12, 13).

In survey waves 5 to 7, the IVS surveys have included a question with a list of several regime characteristics, asking whether the respondents considered each of them as an essential characteristic of democracy on a 10-point scale. The Index Intrinsic Conception of Democracy is an additive index based on the mean score of three intrinsic characteristics:

• People choose their leaders in free elections.

• Civil rights protect people from state oppression.

• Women have the same rights as men.

In the last survey wave in which the 89 countries participated (wave 7 or 6), 14.0% of the respondents have a score below 0.50 on this index, 59.2% one from 0.50 to 0.98, and 26.8% a score of 1. This confirms that the great majority of respondents associate these three intrinsic characteristics with democracy.

3.5 Macro characteristics as independent variables

Since value orientations and political support can be supposed to vary by regime type and region, three macro variables were included in the analysis. The regime variable is based on V-Dem's classification (Lührmann et al., 2018) that distinguishes four regime types: Closed autocracy, electoral autocracy, electoral democracy, and liberal democracy. V-Dem's Codebook lists the following criteria (V-Dem Institute, 2023b, p. 287):

• 7 Closed Autocracies do not hold multiparty elections for the chief executive or the legislature. The IVS includes two traditional monarchies (Morocco and Jordan), one military regime (Thailand), and three one-party systems (China, Hong Kong, Vietnam), and Libya.

• 26 Electoral Autocracies do hold elections for the chief executive and the legislature which are not free and fair, however. Examples are Russia, Turkey, and Iran.

• 26 Electoral democracies do hold de-facto free and fair multiparty elections and grant the institutional safeguards of a polyarchy.

• 21 Liberal Democracies, finally, fulfill all criteria of an electoral democracy. Additionally, the regime is based on the rule of law, provides constitutional constraints on the executive, and guarantees ample personal liberties.

Since a previous analysis (Hoffmann-Lange and Berg-Schlosser, 2022) had revealed that the group of consolidated liberal democracies differed considerably from those that democratized only during the third wave of democratization, the group of liberal democracies was further subdivided into those that had already been liberal democracies in 1980 and those that democratized after 1980. This year was chosen because it marks the beginning of the series of IVS surveys which started in 1981.6

V-Dem's definition of six politico-geographic world regions was slightly modified as well. South and South-East Asia on the one hand and East Asia on the other hand are treated as separate regions because their religious and political traditions differ considerably (see also Inglehart and Welzel, 2005, p. 72–76) Therefore, the analysis will distinguish seven regions:

• 23 Western European democracies (including Greece and Cyprus) and other English-Speaking countries (Canada, USA, Australia and New Zealand). This country group differs by only a few countries from the group of consolidated liberal democracies.7

• 5 East Asian countries with a confucian tradition: China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

• 9 South(-east) Asian countries: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

• 25 post-communist countries in Europe and central Asia, including Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Serbia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, as well as some post-communist EU member states.

• 11 Latin American and Caribbean countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico.

• 6 Sub-Saharan African countries, including Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, and Zimbabwe.

• 10 MENA countries: Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey.

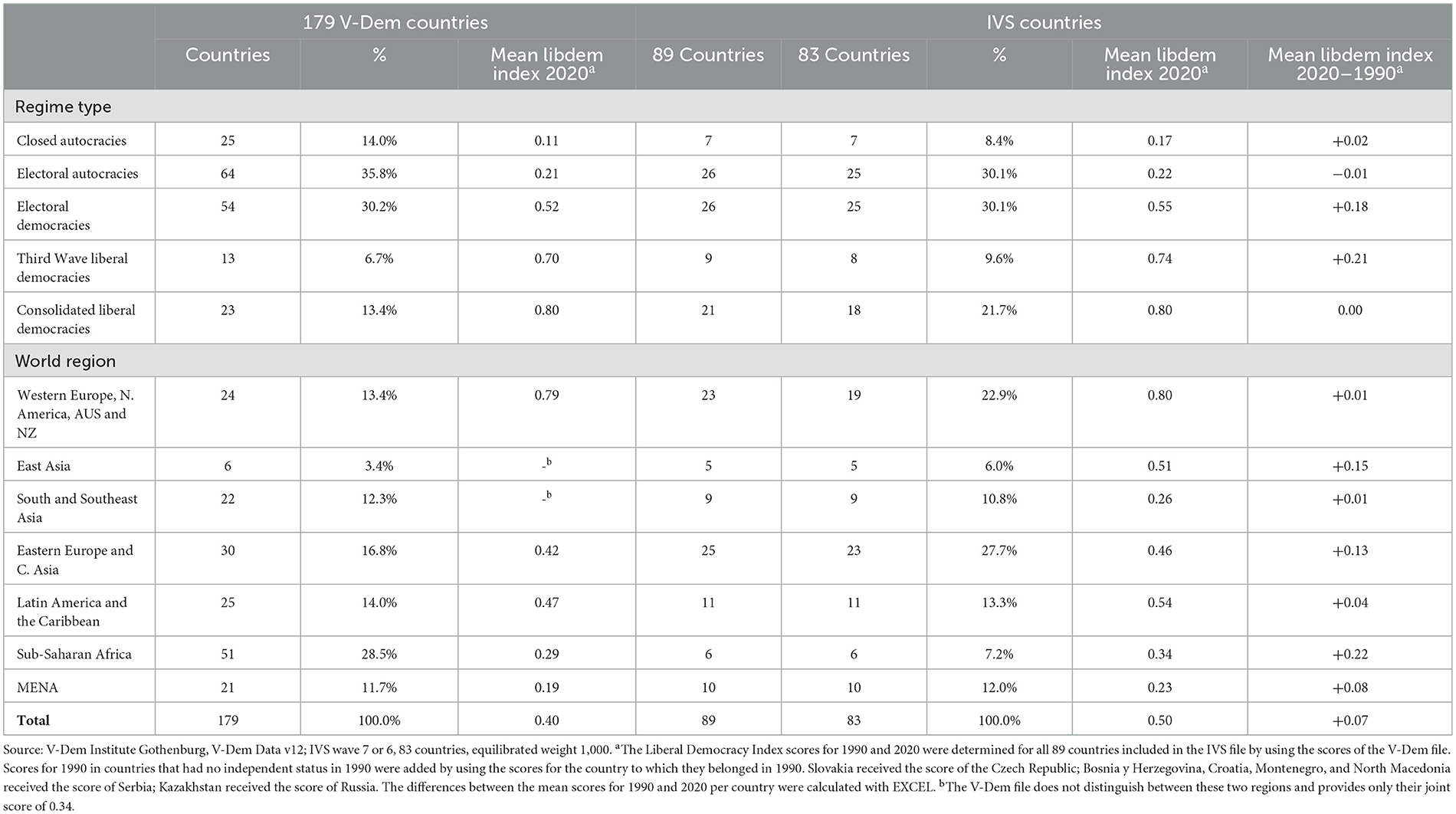

Table 1 includes the number of countries in 2020 for the different regime types and regions included in the V-Dem data base of 179 countries and in the IVS sample of 89 countries. It shows that closed autocracies are severely underrepresented in the sample, while most consolidated liberal democracies have regularly participated.8 The coverage of regions is unsatisfactory for Sub-Saharan Africa, South(-East) Asia (including the Pacific countries), and the MENA region.

In addition to the regime types and regions, the table also includes the mean scores for V-Dem's Liberal Democracy Index.9 The index measures the degree to which a regime fulfills the criteria of liberal democracy. It has a range from 0 to 1. The scores for the different regime types and regions are mostly higher in the IVS sample than in the V-Dem data base.

The differences between the index scores for 2020 and 1990 within the different regime types and regions indicate a remarkable stability over the thirty-year period. The closed and electoral autocracies have retained their low scores, while the electoral democracies and younger liberal democracies have increased their average scores by 0.18 and 0.21. The consolidated liberal democracies have more or less maintained their outlier status with a score far above the mean.

Among the regions, East Asia has improved its score which is primarily due to the democratization of Taiwan and South Korea, while China's score has remained very low with 0.04. The post-communist region shows an increase of 0.13 which is primarily due to the former eastern European members of the Soviet bloc that democratized around 1990. Russia, Belarus, and most of the central Asian countries remained electoral autocracies instead. The considerable increase observed in the six Sub-Saharan African countries in the IVS data is probably unrealistic since they are not representative for the subcontinent.

The data indicate that the steep decline in democratic quality that occurred in a number of large countries after 2007 – for instance in Russia, India, and Turkey – has been compensated by rising scores in other countries (Hoffmann-Lange and Berg-Schlosser, 2022, p. 95–99). Therefore, the country-based approach indicates a higher level of democratic stability than the population-weighted analysis by the V-Dem Institute.

Since socio-economically developed countries are more likely to provide a favorable basis for the development of demands for democracy, the Human Development Index (HDI) the United Nations Development Program is taken into account as a third macro-level indicator. It is a composite index combining three factors: Life expectancy, mean years of schooling in the adult population and GDP per capita. The country scores for 2020 were added to the IVS file.10 The inclusion of the HDI allows to determine whether socioeconomic development has an independent influence on political support.

4 Descriptive analysis of changes in political support in countries with different regime types and located in different world regions

4.1 Political support by regime type and world region

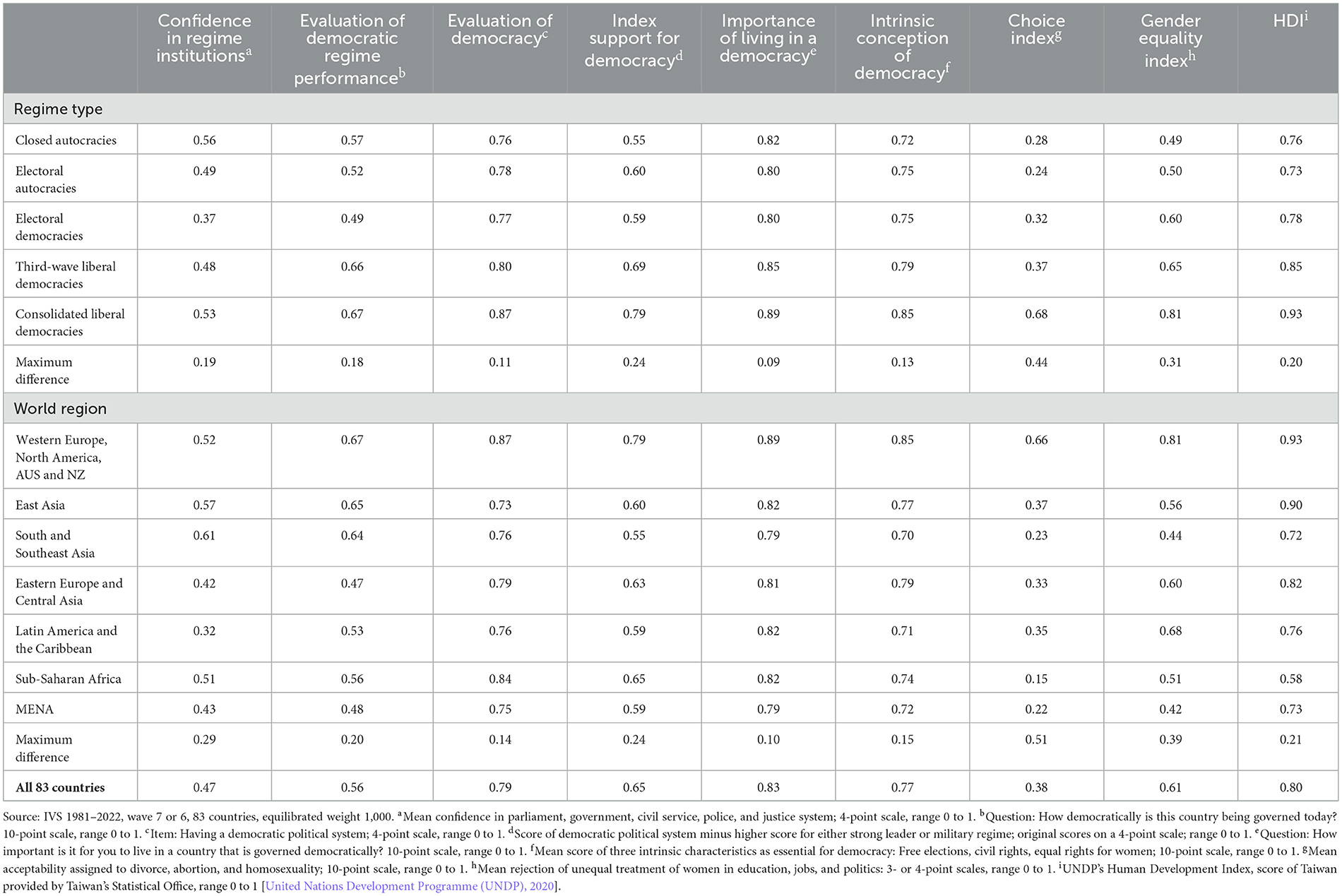

Table 2 provides the mean scores for the different indicators of political support for the latest survey wave by regime type and region. The overall score for confidence in regime institutions of 0.47 lies slightly below the arithmetic mid-point of the scale. The scores for the different regime types suggest a curvilinear relationship with the quality of democracy. They are lowest in electoral democracies and highest both in closed autocracies and liberal democracies. It cannot be excluded, however, that the scores for confidence in regime institutions are unrealistically high in autocratic regimes because respondents are afraid of reprisals if they publicly admit their dislike of the regime. The differences between regions may be influenced by the experiences with regime performance and by a cultural tradition of deference to political authorities. The maximum difference between regions (0.29) is even larger than that for regime types (0.19).

Table 2. Indicators of regime support and emancipative value orientations by regime type and world region for the latest survey wave (mean scores).

The evaluation of democracy, the importance assigned to living in a democracy, and an intrinsic conception of democracy reach ratings above 0.70. The scores confirm that the term “democracy” enjoys high popularity across the globe. People value democracy primarily for its intrinsic qualities, which includes individual freedom, the right to vote, and protection from arbitrary rule.

The scores of the index Support for Democracy measure a preference for democracy compared to non-democratic alternatives and are therefore lower. This is not surprising since democracy is a political order in which a broad variety of actors with conflicting interests participate in political decision-making. It involves time-consuming bargaining before political decisions can be reached which is not appreciated by everyone. Therefore, many respondents express at least some sympathy for authoritarian forms of political decision-making.

The choice index achieves the lowest scores and shows again larger differences between regions than between regime types. The items of the choice index measure acceptance of behaviors that traditionally used to be considered as offensive and which are still illegal in many countries. The scores confirm that they remain controversial even in consolidated liberal democracies. Gender equality is less controversial and receives higher scores than the choice index, although equal rights for women are still elusive in many countries. The regional differences found for these emancipative value orientations are probably due to the more traditional living conditions and the lower HDI scores in the three regions with the lowest scores for emancipative values.

4.2 Trends in emancipative values and political support

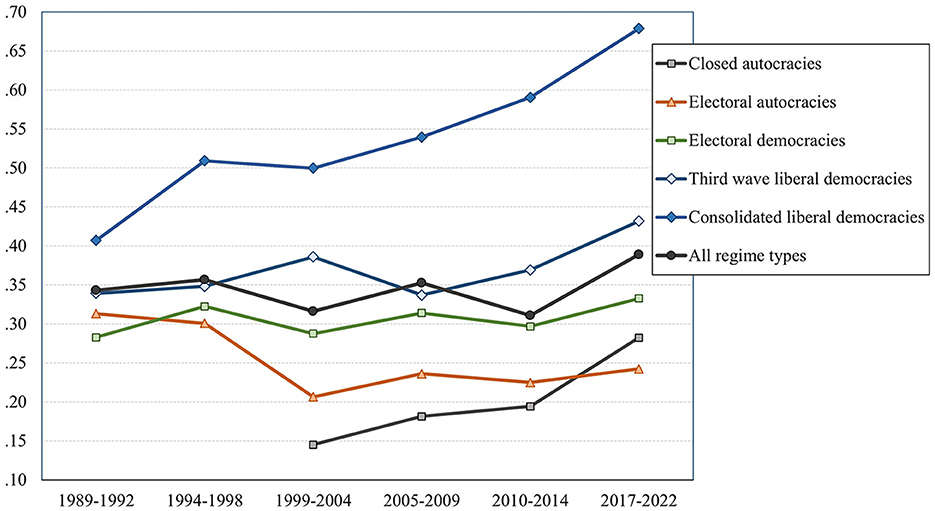

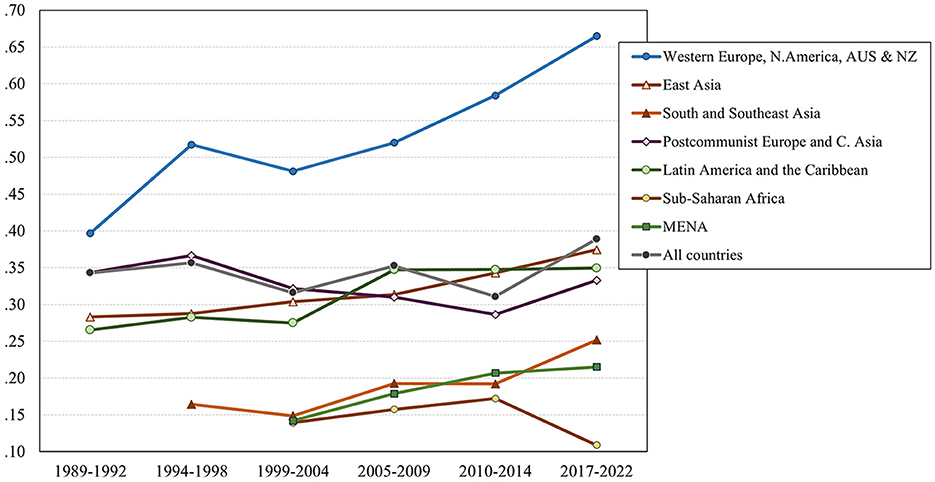

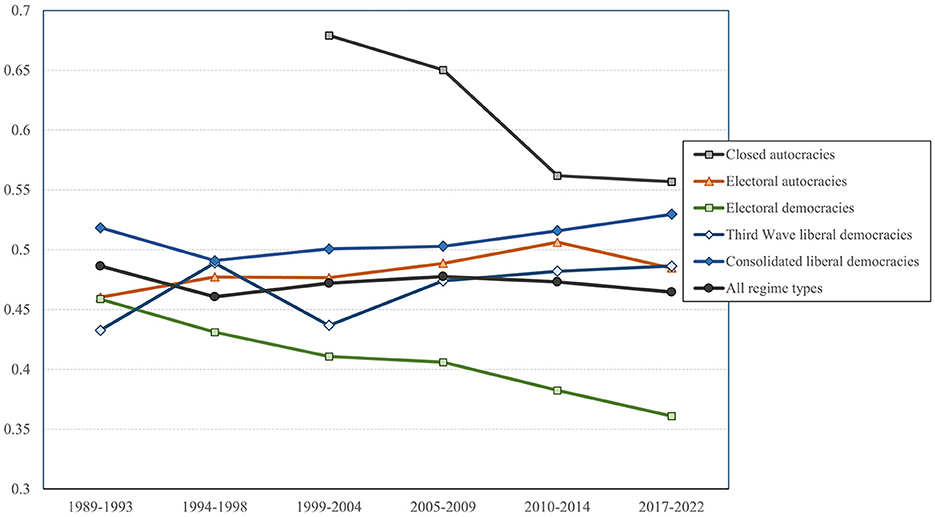

Figures 1–6 visualize trends in the mean scores for the Choice Index, the index Confidence in Regime Institutions, and the index Support for Democracy by regime type and region. The lines have to be interpretated with caution because the country composition of the surveys changed between the different waves. Countries were assigned to the regime type of their last participation in the IVS. The results are primarily instructive for identifying trends over the entire period. Scores for regime types and regions are included only if at least three countries participated per country group and wave. It is inevitable that these figures conceal sometimes considerable differences between individual countries within each country group. Readers interested in more detailed information can find information on 20 countries that participated in at least three survey waves in Appendix Figures 1–12.

Figure 1. Support for free choice of lifestyle by regime type 2020. Source: IVS 1981–2022, 89 countries, equilibrated weight.

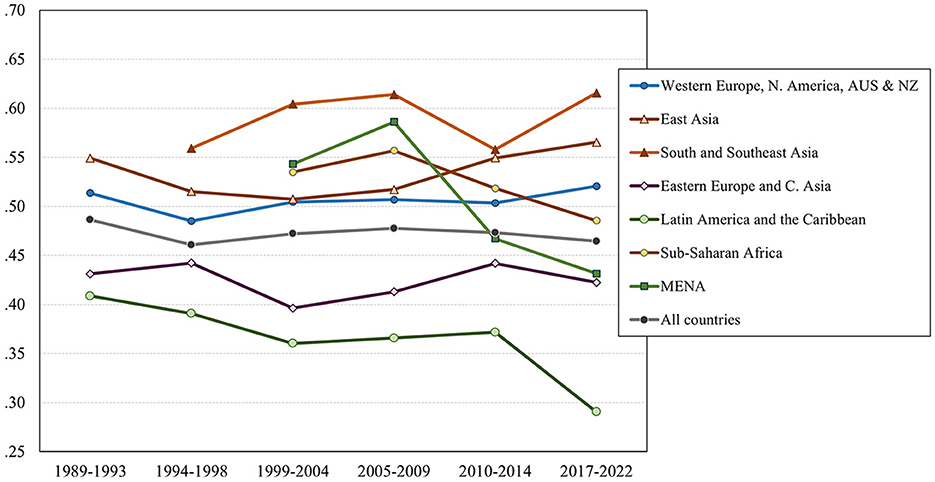

Figure 2. Support for free choice of lifestyle by region. Source: IVS 1981–2022, 89 countries, equilibrated weight.

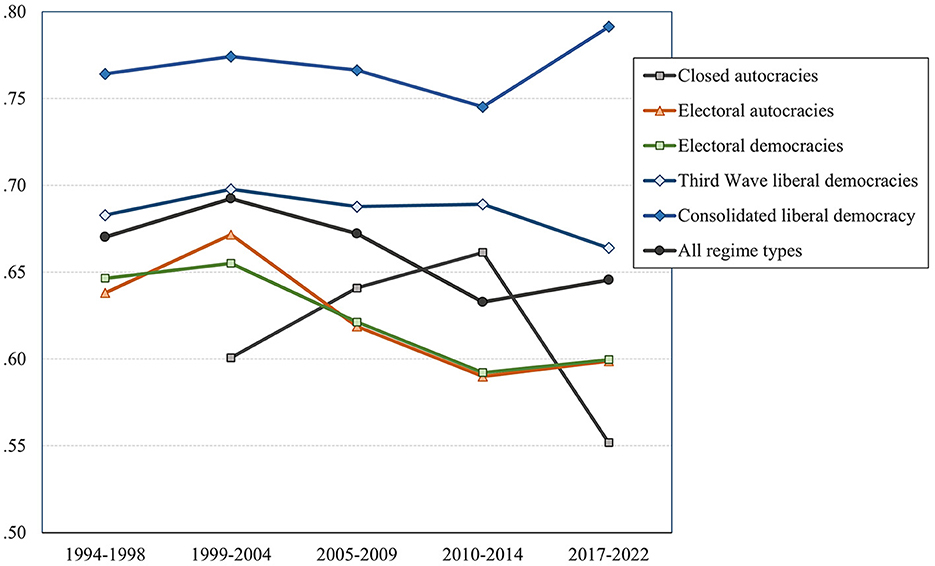

Figure 3. The development of confidence in regime institutions by regime type 2020. Source: IVS 1981–2022, 89 countries, equilibrated weight.

Figure 4. Confidence in regime institutions by region. Source: IVS 1981–2022, 89 countries, equilibrated weight.

Figure 5. The development of support for democracy by regime type 2020. Source: IVS 1981–2022, 89 countries, equilibrated weight.

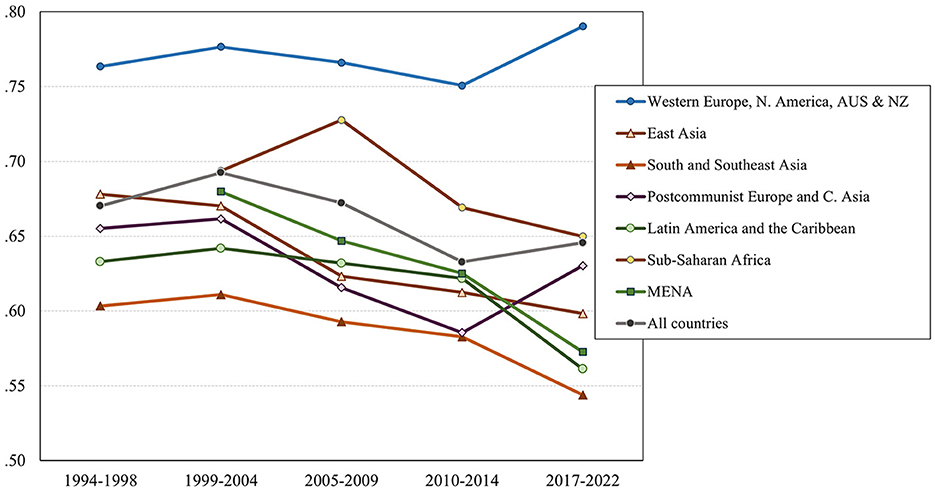

Figure 6. The development of support for democracy by world region. Source: IVS 1981–2022, 89 countries, equilibrated weight.

The main message of Figure 1 is the disproportional rise in support for emancipative values in the consolidated democracies. This confirms the argument by Foa et al. (2022) that most of the increase in emancipative values over the last decades has occurred within this group of countries. Disregarding the small difference between closed and electoral autocracies, the rank order of regime types conforms to their rank on the liberal democracy index. It indicates that the provision of individual liberties tends to foster tolerance of different lifestyles.

Figure 2 confirms that not only regime type, but also regional cultural traditions influence the development of emancipative value orientations. Three different groups of regions can be distinguished. The western countries show the highest scores. The gap between them and the other regions has considerably increased over time. Their trend is nearly identical with the one for the consolidated liberal democracies in Figure 1. East Asia, Latin America, and the post-communist region achieve scores between 0.3 and 0.4, while the more traditional regions show the lowest levels of tolerance.

In Figure 3, the line for confidence in regime institutions in the closed autocracies stands out by showing a steep drop from a very high score of 0.68 in wave 4 to 0.56 in wave 6. The electoral democracies show a continuous decline from 0.46 to 0.32. The scores of the other regime types have been more or less stable. Figure 4 shows considerable differences between regions as well as some variation over time. Only a more differentiated analysis can show whether these results are due to systematic differences between regime types and regions or whether they are primarily due to country-specific effects reflecting changes in the economic or political performance of the individual countries.

Figure 5 indicates that support for democracy has slightly decreased over the last three decades. Again, the consolidated liberal democracies confirm their exceptional status by even showing a slight growth from 0.76 to 0.79. The other liberal democracies achieve the second-highest level of 0.66 in the latest wave but show no increase of their scores since the mid-1990s. Within this group, only the scores of Spain (0.72 to 0.79) and Estonia (0.68 to 0.77) have increased, while the scores have declined in South Korea (0.69 to 0.51) and Taiwan (0.63 to 0.56), as can be seen in Figure 9 of the Appendix. The scores of Cyprus and Uruguay have remained stable at 0.70. Ghana and Trinidad and Tobago which only participated in the last two survey waves have scores above 0.70.

The other regime types show a slight initial increase, followed by conspicuous declines in electoral democracies and autocracies. The latter was especially dramatic in the closed autocracies where support fell between wave 6 and wave 7 from 0.66 to 0.55. Recoding support for democracy into five categories (preference for an autocratic system, indifference, medium to high support for democracy) confirms this impression. In the latest wave, the differences between autocracies and electoral democracies are negligible: 17.4% of their citizens preferred an autocratic system, 37.8% were indifferent, 20.4% expressed a light preference and only 24.5% a strong preference for democracy. This contrasts with the results for the consolidated democracies where the shares in the two lowest categories were only 5.0% and 14.3%, while 38.1% of the respondents achieved a score of 1.

Figure 6 finally shows a downward trajectory in five of the seven regions, some fluctuation in the post-communist countries and a slight increase only in the western democracies. These data do not confirm the optimistic assumption that support for democracy is globally increasing. Instead, the subjective evaluations reflect the overall stagnation found for V-Dem's liberal democracy index for the period since 1990.

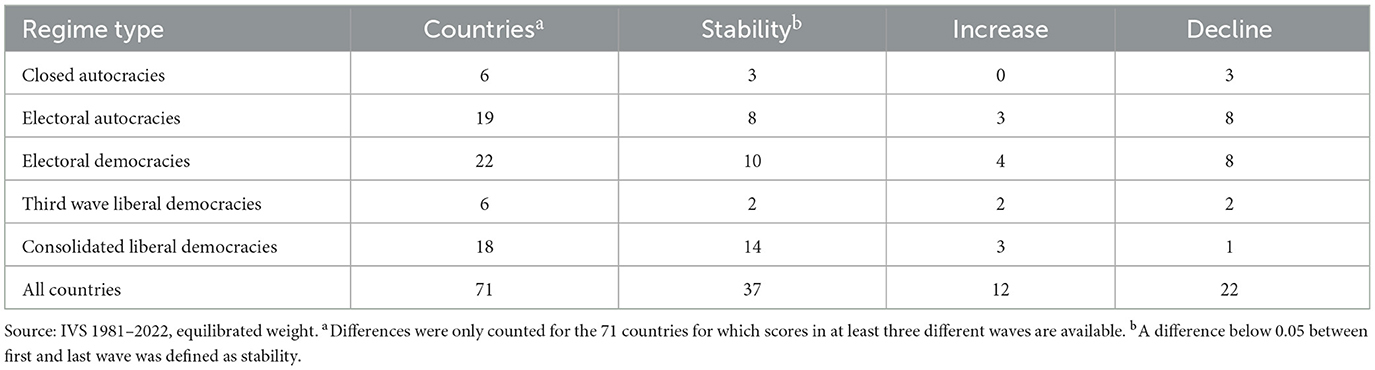

Table 3 provides additional information on the temporal dynamics of support for democracy within the different regime types. In about half of the 71 countries for which the scores for at least three the waves are available, the deviations from the country mean are smaller than 0.05. Overall, declines have been more frequent than increases. The most dramatic declines occurred in Iraq (−0.32), Morocco (−0.23), and Montenegro (−0.33).11 The scores for the consolidated liberal democracies show the highest stability. The United States are the only country in this group with a decline of −0.10.

These results are theoretically important because they indicate that support for democracy is not necessarily a stable value orientation as the theory of political support implies (Easton, 1975, p. 445). This is the case only in the consolidated liberal democracies. In autocracies and electoral democracies, the number of countries with changes exceeds the ones with stable scores.

The large number of changes in support for democracy may be due to the current political turbulences that make it more difficult for people to develop a stable regime orientation. One must not forget, after all, that Easton's theory was developed for consolidated democracies in the politically quiet decades after World War II. The IVS data show that his theoretical expectations still hold true for this group of countries but cannot be generalized to other regime types.

5 Determinants of confidence in regime institutions and support for democracy

Multiple regression analysis was used for determining the influence of micro-level and macro-level factors on confidence in regime institutions and support for democracy. The theory of political support assumes that the different levels of support mutually reinforce each other through a generalization of experiences and an overflow of values. Therefore, support for democracy was included in the models for confidence in regime institutions as independent variable. Vice versa, confidence in regime institutions was included in the regression models for explaining support of democracy.

Because the theory of political support was developed for studying democratic regimes, little is known about the impact of regime type on political support. Therefore, a dummy variable for the consolidated liberal democracies was included because emancipative value orientations have disproportionately increased in this group of countries. The effect of region was taken into account by including a dummy variable “traditional regions” which encompasses the three regions with the lowest HDI levels, the lowest scores on V-Dem's liberal democracy index, and the lowest scores for the choice index: South-(East) Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the MENA countries. Finally, a dummy variable for the Human Development Index (HDI) was included to determine whether a high level of socioeconomic development has an additional effect on political support.12

All 83 countries that participated in survey waves 7 or 6 were included in the analysis.13 This was necessary for including the dummy variable for consolidated liberal democracies in the regression models. For controlling whether the regression coefficients for the micro-level variables are influenced by the different regime contexts, separate analyses were performed for the five different regime types.

Because of the large number of 140,671 respondents, all regression coefficients included in Tables 4 and 5 are significant at the 0.001 level. Effects with a β coefficient of <0.10 will not be considered as having a substantial effect, however, even though they are statistically significant.

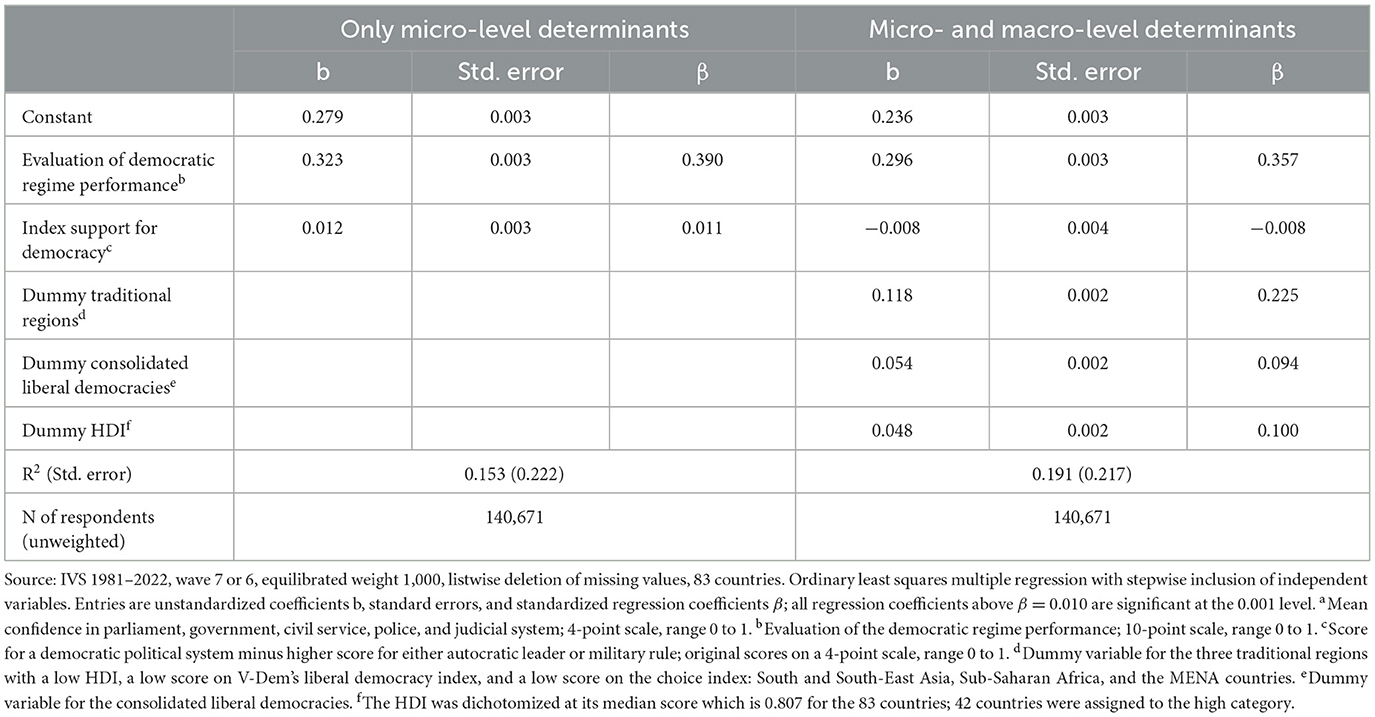

5.1 Confidence in regime institutions

Confidence in regime institutions is an important component of political support because it may help new democracies to achieve legitimacy by proving their political and economic effectiveness. The first regression model in the left-hand panel of Table 4 includes only the two micro-level predictors. Theoretically, it is expected to depend primarily on the evaluation of the regime's political performance. The second independent variable is support for democracy which shows whether an overflow of values plays a role for confidence in regime institutions. The choice and the gender equality indices as indicators of emancipative value orientations were not included because their bivariate correlations with the dependent variable were close to zero.

The results confirm a strong influence of the respondents' rating of the democratic performance of their regime. It is important to keep in mind that this is a subjective evaluation and does not imply that citizens in the countries with higher scores also enjoy more democratic rights. Support for democracy exerts no substantial effect on confidence in regime institutions. Moreover, the overall explanatory power of the model with only individual-level predictors is very low. The inclusion of the three macro-level predictors increases the explanatory power of the model slightly, from 15.4% to 19.1%. It indicates that all three macro indicators increase confidence in regime institutions, even though the β coefficient for the consolidated liberal democracies is slightly below the threshold of 0.10.

The regression coefficients confirm the impression of a curvilinear relationship suggested by Figures 3 and 4. Confidence in regime institutions is higher in the consolidated liberal democracies, in the traditional regions, and in the countries with a higher HDI. The relatively low explanatory power of both models in Table 4 finally suggests that country-specific factors are obviously more important for this dimension of regime support.

Separate analyses for the five regime types confirm that the perceived democratic regime performance is the most important predictor of confidence in regime institutions. The results of these analyses are included in Appendix Table 3. The considerably lower explanatory power of the models both in electoral democracies and Third Wave liberal democracies suggests that these two regime types tend to be less stable politically. Overall, the results confirm Mauk's (2020, chapter 5) conclusion that confidence in regime institutions primarily depends on the political and economic performance of the country while it does not differ systematically between democracies and autocracies.14

5.2 Support for democracy

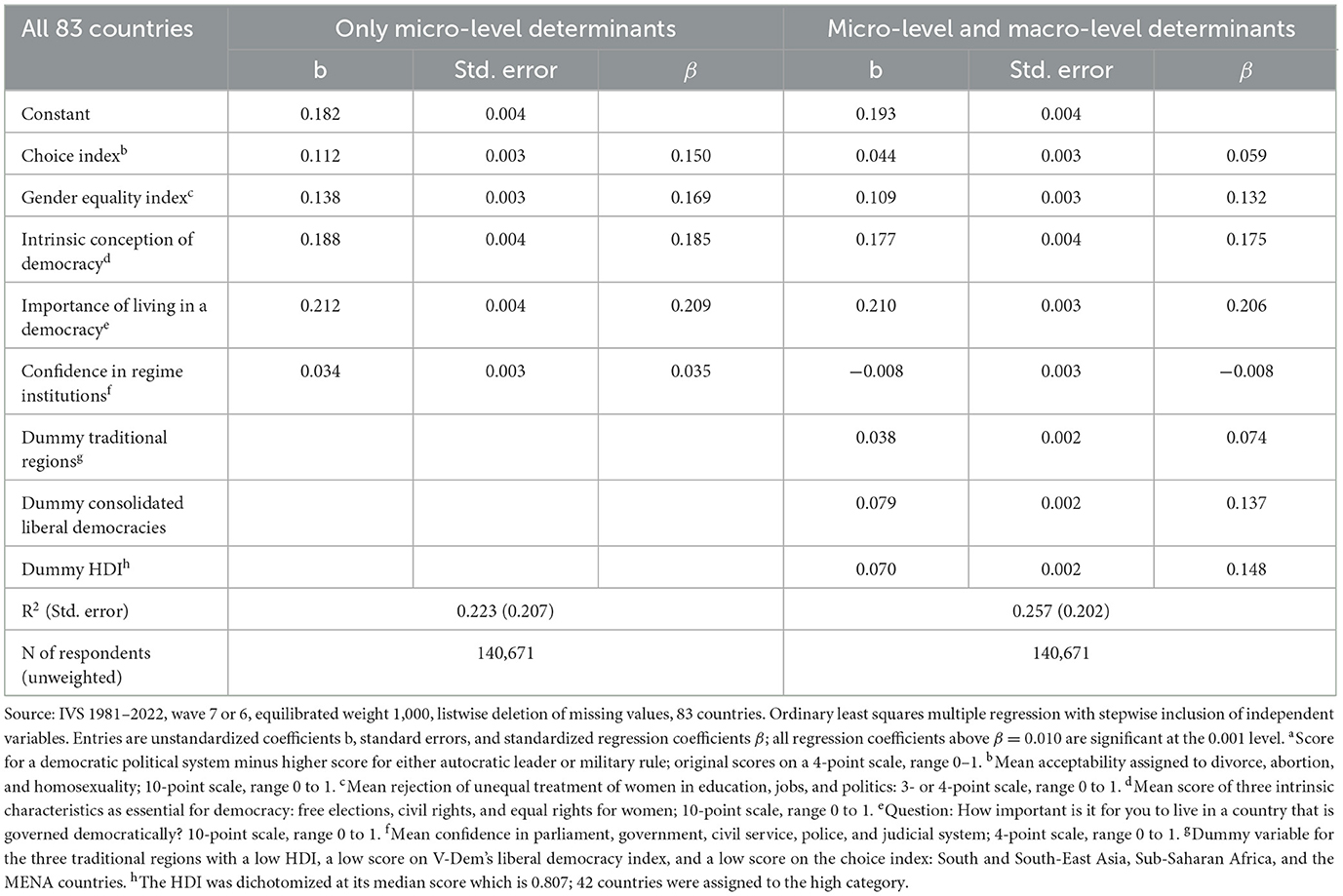

The theory of value change assumes that emancipative value orientations are conducive to increasing a commitment to support civil liberties and political participation rights for citizens. Unfortunately, only two of the four dimensions included in Welzel's Index of Emancipative Values are adequately covered in the IVS, choice and gender equality. They were included as independent variables in the analysis. The reliability and validity of Welzel's autonomy and voice indices were insufficient and thus precluded the inclusion of these indices. These two aspects are partly covered by the index intrinsic conception of democracy. It measures the cognitive understanding of fundamental democratic principles whose theoretical importance has been demonstrated by previous studies. In addition to these three value orientations, the importance assigned to living in a democracy and confidence in regime institutions are included as micro-level indicators in the regression models.

The results for all 83 countries are presented in Table 5. The left-hand panel shows the effects of the five micro-level indicators. Four of the five micro-level variables have a sizeable effect on support for democracy. The importance of living in a democracy and an intrinsic conception of democracy exert the strongest effects.15 The β coefficient for confidence in regime institutions is below 0.10 and cannot be considered as a relevant influence factor. The overall explanatory power of the model is 22.3%, a good deal higher than the one found in the regression analysis for confidence in regime institutions.

Adding the three macro indicators slightly increases the explanatory power to 25.7%. Both the HDI and the dummy for the consolidated liberal democracies have a sizeable effect, while the regression coefficient for the traditional regions is below β = 0.10. The effects of the two strongest micro-level predictors do not change much. The effect strength of the choice index, however, declines from β = 0.150 to β = 0.059, and that of gender equality is lower as well. This reduction is probably due to the considerably lower support for emancipative values in the traditional regions and in the countries with a lower HDI.

As before, separate analyses were performed for the five regime types to test whether they confirm the results of the combined analysis. They can be found in Appendix Table 4 and confirm that the importance of living in a democracy and an intrinsic conception of democracy have the strongest impact on support for democracy. The regression coefficients for choice and gender equality are considerably higher in electoral and Third Wave democracies than in autocracies and consolidated liberal democracies. It can be suspected that these issues are more controversial and therefore more closely associated with regime preference in these two mixed regime types.

6 Conclusions

Starting out with the question of democratic decline vs. resilience, this analysis studied the global development of democracy. It relied on the exceptionally broad data base of the Integrated Values Surveys (IVS), a series of replicative representative surveys including 89 countries that participated in at least two of the altogether seven survey waves, covering a period of more than 30 years. Recent studies on the global development of democracy have come to contradictory conclusions. The publications by Freedom House, the Varieties of Democracy project, and many other authors have discerned a global trend of democratic backsliding since the mid-2000s. Based on his longitudinal studies on value change, Welzel perceives an ongoing rise of emancipative value orientations instead, even in regions and countries without democratic tradition. He expects that this will inevitably lead to a further spread of democracy.

The IVS data support neither of these scenarios. For the period since the mid-1990s, they do show a considerable increase of emancipative value orientations only in the liberal democracies, but not in other parts of the globe. On the other hand, the data also show that the decline of democracy has not been as dramatic as the Freedom House and V-Dem studies claim. The number of countries that have become more autocratic has been limited to a small number of large and populous countries, especially China, Russia, India, and Indonesia. Since these countries have never been paragons of liberal democracy in the first place, ignoring a parallel democratic progress in many smaller countries is unnecessarily pessimistic.

Confidence in regime institutions shows a good deal of fluctuation over time in both autocracies and democracies, without any discernable trend. It is highest in closed autocracies and consolidated liberal democracies, and lowest in electoral democracies. This supports the assumption that countries in which the power structure matches legitimacy claims have higher confidence scores than those in which the power structure falls behind the regime's promises. The evaluation of (democratic) regime performance turned out to have the strongest influence on confidence in regime institutions. This suggests that citizens appreciate it when their regime delivers what they expect from it. The standards which citizens apply differ however. Higher scores do not necessarily imply that a regime actually observes higher democratic standards.

The index support for democracy measures a preference for democracy compared to a non-democratic regime. Over the last decades, it has been consistently high in most of the consolidated liberal democracies. At the same time, it has been considerably lower in other parts of the world and has slightly declined overall. In some countries it has even declined dramatically. An intrinsic conception of democracy and a high importance assigned to living in a democracy are the strongest micro-level predictors.

A central assumption of the theory of political support is not supported by the data. The two central indicators of political support, confidence in regime institutions and support for democracy are statistically unrelated (r = 0.051) thus indicating that they follow different cognitive logics. The perception of the democratic quality of the country's regime is instead moderately related to the importance attributed to living in a democracy (r = 0.186), an intrinsic conception of democracy (r = 0.131), and support for democracy (r = 0.101). This suggests that confidence in regime institutions measures specific support rather than support for the structural level of the regime. In retrospect, reversing the model and treating the evaluation of the regime's democratic performance as a measure of support for the regime's structure as dependent variable would have produced a better fit with Easton's theory.

Overall, the analysis showed that it is insufficient to base predictions about the future of democracy primarily on developments in the established democracies and to look for signs that the others will follow their lead. Instead, it seems necessary to obtain more systematic knowledge about the factors influencing political legitimacy. Our current theories of legitimacy focus too much on the dichotomy between democracies and autocracies and place much emphasis on participatory democracy as a source of legitimacy. Thereby, they do not adequately take into account that for most citizens effective governance is more important than ample political participation rights.

The latter has been abundantly demonstrated by the literature on stealth democracy in consolidated democracies. Many citizens show an aversion to political conflict and limited interest in public affairs. “The goal in stealth democracy is for decisions to be made efficiently, objectively, and without commotion and disagreements. As such, procedures that do not register on people's radar screens are preferred to the noisy and divisive procedures typically associated with governments” (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002, p. 143). In a recent study, Bloeser et al. confirmed that the majority of the American citizens show a preference for what the authors denote as expedient governance. This was measured by agreement with three items: That government would be run better if decisions were left to independent experts, that compromise involves selling out one's political principles, and that elected officials would help the country more if they would stop talking and just take action (Bloeser et al., 2024, p. 120). The study found that such support was even higher among respondents who preferred leaders who bend the rules and attack their rivals. “Support for expedient governance is highest, in fact, among citizens who have a high degree of support for protective leadership and who express discomfort with political disagreement” (Bloeser et al., 2024, p. 123). This confirms the importance of determining the impact of good governance on political legitimacy.

The analysis also shows that it is not sufficient to study political legitimacy only in democratic countries. Comparative studies including countries with different regime types provide a broader perspective on what citizens expect from their regimes and what determines their perceptions. They require survey data that do not only cover value orientations but also regime perceptions and evaluations for the different levels of political support: Political authorities, regime institutions, and regime principles. Since representative surveys are difficult to conduct in highly autocratic countries, case studies can help filling the knowledge gap and provide more differentiated insights into the determinants of political legitimacy.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These datasets can be found here: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSEVStrend.jsp.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the World Values Survey Association and the European Values Study Group (EVS Foundation). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

UH-L: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Financial support for the publication of this article by the University of Bamberg is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1323464/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^V-Dem is using the term autocratic regimes for all types of non-democratic regimes, even though it is obvious that not all of them are autocratic in the sense that they are governed by a single all-powerful autocrat. Non-democratic regimes may also be governed by a ruling body, for instance the Politburo of a ruling party. Since the following analysis is based on V-Dem's slightly modified classification of regimes, the term autocracy will be used for all types of non-democratic systems (Coppedge et al., 2022, p. 287).

2. ^In Europe, populist parties have been particularly successful in the post-communist EU member countries because their citizens who feel overburdened by pressures to cope with an increasing stream of new EU regulations which they consider as overbearing (cf. Ilonszky and Vajda, 2021; Van Beek, 2022; Miscoiu, 2023).

3. ^Information on the two data files and instructions on how to merge them can be found on: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSEVStrend.jsp (European Values Study, 2017; Haerpfer et al., 2022).

4. ^The first wave of surveys (1981-1984) included only 23 of the 89 countries, most of which were western democracies. The number of countries increased to 42 already in wave 2 (1989–1993), including eleven post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Participation continued to rise over the next waves to 76 countries in the seventh wave. 11 of the 89 countries participated in two waves, 16 in three, 24 in four, 16 in five, 14 in six, and 8 in all seven.

5. ^Alemán and Woods (2016), Sokolov (2018), and Meuleman et al. (2023) tested the construct validity of Welzel's EVI with WVS data and found it to be rather low. They contended that its scores can be meaningfully compared only among advanced post-industrial democracies. Welzel and Inglehart (2016) as well as Welzel et al. (2019) refuted these arguments by claiming that their macro-level explanations do not require an inter-cultural invariance of meaning. This implies, as Sokolov remarked in response, that the EVI index is supposed to measure an ideal type and that the results of their analysis primarily indicate the degree to which the results for the different countries confirm the theory of value change.

6. ^Huntington (1991) chose the 1974 carnation revolution in Portugal as starting point of the third wave of democratization. Since it usually takes new democracies considerable time to reach the status of liberal democracy, Portugal is the only third-wave democracy that had achieved it already by 1980. Therefore, it is included in the group of consolidated democracies.

7. ^Japan is the only non-Western consolidated liberal democracy. Conversely, three western European Third Wave democracies, Cyprus, Malta, and Spain, do not belong to this group.

8. ^Two regime types include less than ten countries: The seven closed autocracies are China, Hong Kong, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Thailand, and Vietnam. The nine Third Wave liberal democracies are Cyprus, Estonia, Ghana, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, Trinidad and Tobago, and finally Uruguay.

9. ^The V-Dem file includes countries only after they achieved political sovereignty. Therefore, six of the 89 countries have no liberal democracy score for 1990. This was solved by adding the scores of the country to which these countries belonged in 1990. Kazakhstan received the score of Russia (0.093). Likewise, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, (North) Macedonia, and Montenegro received the score of Serbia (0.153). Slovakia, finally, received the score of the Czech Republic (0.609).

10. ^Since Taiwan is not a member of the UN, the score provided by Taiwan's Statistical Bureau for 2021 was included which is calculated by using the UN's procedure.

11. ^Appendix Table 1 shows the shares for all five regime types. Table 2 provides all scores in support for democracy for the 18 countries with a difference of 0.10 or more between the first and the last survey wave in which for which scores are available.

12. ^It divides the 83 countries at their median score. The scores range from 0.498 for Ethiopia to 0.959 for Norway. The median score is 0.807, assigning 41 countries to the low and 42 to the high category.

13. ^Because the country composition in the different waves is not constant and very few countries participated in all waves, the data are not suited for a longitudinal analysis. Therefore, cross-sectional regression analyses were performed for the 83 countries that participated in survey waves 7 or 6.

14. ^Mauk's indicator of political performance was based on a question on how safe respondents felt in their neighborhood. Unfortunately, this question was not asked in 33 of the 83 countries of wave 7 which precluded the inclusion of this indicator in the analysis.

15. ^In their statistically sophisticated analysis of the relationship between different conceptions of democracy and support for democracy, Chapman et al. (2024) came to similar conclusions.

References

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., and Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. J. Polit. Econ. 127, 47–100. doi: 10.1086/700936

Alemán, J., and Woods, D. (2016). Value orientations from the world values survey: How comparable are they cross-nationally?. Comp. Polit. Stu. 49, 1039–1067. doi: 10.1177/0010414015600458

Bloeser, A. J., Williams, T., Crawford, C., and Harward, B. M. (2024). Are stealth democrats really committed to democracy? Process preferences revisited. Perspect. Polit. 22, 116–130. doi: 10.1017/S1537592722003206

Bratton, M., and Mattes, R. (2001). Support for democracy in Africa: intrinsic or instrumental? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 31, 447–474. doi: 10.1017/S0007123401000175

Brunkert, L. J. (2022). Overselling democracy-claiming legitimacy! The link between democratic pretention, notions of democracy and citizens' evaluations of regimes' democraticness. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:880709. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.880709

Chapman, H. S., Hanson, M. C., Dzutsati, V., and DeBell, P. (2024). Under the veil of democracy: what do people mean when they say they support democracy?. Persp. Poli. 22, 97–115. doi: 10.1017/S1537592722004157

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., et al. (2022). V-Dem Codebook v12. Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

European Values Study (2017). EVS Trend File 1981–2017. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7503 Data file Version 3.0.0. doi: 10.4232/1.14021

Foa, R. S., Mounk, Y., and Klassen, A. (2022). Why the future cannot be predicted. J. Dem. 33, 147–155. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0010

Freedom House (2023). Freedom in the World 2023: Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

Fuchs, D. (2007). “The political culture paradigm,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, eds R. J. Dalton and K. Hans-Dieter (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 161–184.

Fuchs, D., and Klingemann, H.-D. (2009). “David Easton: the theory of the political system,” in Masters of Political Science, eds D. Campus and G. Pasquino (Colchester: ECPR Press), 63–83.

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., and Diez-Medrano, J. (2022). World Values Survey Trend File (1981-2022) Cross-National Data-Set. Madrid: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. doi: 10.14281/18241.23

Hibbing, J. R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth Democracy: Americans' Beliefs About How Government Should Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoffmann-Lange, U., and Berg-Schlosser, D. (2022). “Macro- and micro-level analyses,” in Democracy Under Pressure. Resilience or Retreat?, ed U. van Beek (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 89–140.

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century. Norman, OA: University of Oklahoma Press.

Ilonszky, G., and Vajda, A. (2021). How far can Populist Governments Go? The Impact of the populist government on the Hungarian Parliament. Parliam. Affairs 74, 770–785. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsab007

Inglehart, R. (1971). The silent revolution in europe: intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 65, 991–1071. doi: 10.2307/1953494

Inglehart, R. (1977). The Silent Revolution. Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R. F., and Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klingemann, H. D. (1999). “Mapping political support in the 1990s: a global analysis,” in Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Governance, ed P. Norris (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 31–56.

Klingemann, H. D. (2018). The impact of the global economic crisis on patterns of support for democracy in Germany. Historical Soc. Res. 43, 203–234. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26544256

Kriesi, H. (2013). Democratic legitimacy: Is there a legitimacy crisis in contemporary polities? Politische Vierteljahresschrift 54, 609–638. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2013-4-609

Lührmann, A., Tannenberg, M., and Lindberg, S. I. (2018). Regimes of the world (RoW): opening new avenues for the comparative study of political regimes. Polit. Gov. 6, 60–77. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214

Mauk, M. (2020). Citizen Support for Democratic and Autocratic Regimes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meuleman, B., Żółtak, T., Pokropek, A., Davidov, E., Muthén, B., Oberski, D. L., et al. (2023). Why measurement invariance is important in comparative research. A response to Welzel et al. (2021). Sociol. Methods Res. 52, 1401–1419. doi: 10.1177/00491241221091755

Miscoiu, S. (2023). “De l'euroscepticisme léger à l'anti-européanisme radical: la crise des réfugiés de 2015 dans les débats politiques des pays de L'Europe central et orientale,” in Transcultural Europe in the Global World, eds A. Benucci, S. Contarini, G. Condeio, G. Dos Santos, J. Manuel Esteves. Paris: Presse Universitaires de Paris Nanterre, 285–312.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sokolov, B. (2018). The index of emancipative values: measurement model misspecifications. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 395–408. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000624

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2020). Global Human Development Indicators. Available online at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries (accessed March 8, 2020).

Van Beek, U. (2022). “Back to the future: the rise of nationalist populism,” in Democracy Under Pressure. Resilience or Retreat?, ed U. van Beek (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 63–85.

V-Dem Institute (2023a). Democracy Report 2023: Defiance in the Face of Autocratization. Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute. Available online at: https://www.v-dem.net/publications/democracy-reports/

V-Dem Institute (2023b). Codebook v13-March 2023. Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute. doi: 10.23696/vdemds23

Walker, C. (2022). Rising to the sharp power challenge. J. Dem. 13, 119–132. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0051

Walker, C., and Ludwig, J. (2022). A Full Spectrum Response to Sharp Power: The Vulnerabilities and Strengths of Open Societies. Washington, DC: L National Endowment for Democracy.

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Welzel, C., Brunkert, L., Inglehart, R. F., and Kruse, S. (2019). Measurement equivalence? A tale of false obsessions and a cure. World Values Res. 11, 54–84. Available online at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSPublicationsPapers.jsp

Welzel, C., and Inglehart, R. F. (2016). Misconceptions of measurement equivalence: time for a paradigm shift. Comp. Polit. Stu. 49, 1068–1094. doi: 10.1177/0010414016628275

Keywords: political support, confidence in institutions, support for democracy, liberal democracies, autocracies, value orientations

Citation: Hoffmann-Lange U (2024) The global development of value orientations, political support and democracy since the 1990s. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1323464. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1323464

Received: 17 October 2023; Accepted: 25 March 2024;

Published: 10 May 2024.

Edited by:

Peter Schmidt, University of Giessen, GermanyReviewed by:

Sergiu Miscoiu, Babes´-Bolyai University, RomaniaEdnaldo Ribeiro, State University of Maringá, Brazil

Copyright © 2024 Hoffmann-Lange. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ursula Hoffmann-Lange, dXJzdWxhLmhvZmZtYW5uLWxhbmdlQHVuaS1iYW1iZXJnLmRl

Ursula Hoffmann-Lange

Ursula Hoffmann-Lange