- The Multidisciplinary Department, Western Galilee College, Acre, Israel

Introduction: This study presents a comprehensive set of measurements for assessing legislative backsliding and authoritarian populist rhetoric.

Methods: I demonstrate the use of these measures by comparing the discussions involved in passing three Basic Laws in Israel. One was enacted in the 20th Knesset term, whereas the other two were passed during the current 25th Knesset that began in 2022.

Results and discussion: The findings indicate more legislative backsliding in the 25th Knesset than in the 20th Knesset. The quality of the deliberative process was poorer, there was less respect for informal institutions, and there was more use of formal procedures to change previous behavioral norms during the 25th Knesset. In addition, the use of authoritarian populist rhetoric increased during this Knesset term and was used to justify and legitimize legislative backsliding.

Introduction

Since the start of the twenty-first century, there has been an increase in the number of populist leaders heading democracies. These leaders often use populist rhetoric to persuade voters that they alone represent the authentic voice of the people. During this same period, Western democracies also experienced democratic backsliding, which involved legislative backsliding. Scholars have argued that in democracies, populist leaders threaten the functioning of parliaments. Thus, it is essential to explore the role of populism as a factor in legislative backsliding. To do so, I present a theoretical framework for examining legislative backsliding and a theoretical framework for authoritarian populist rhetoric. I then posit the research hypotheses I tested by comparing the discussions around three Israeli Basic Laws.

Literature review

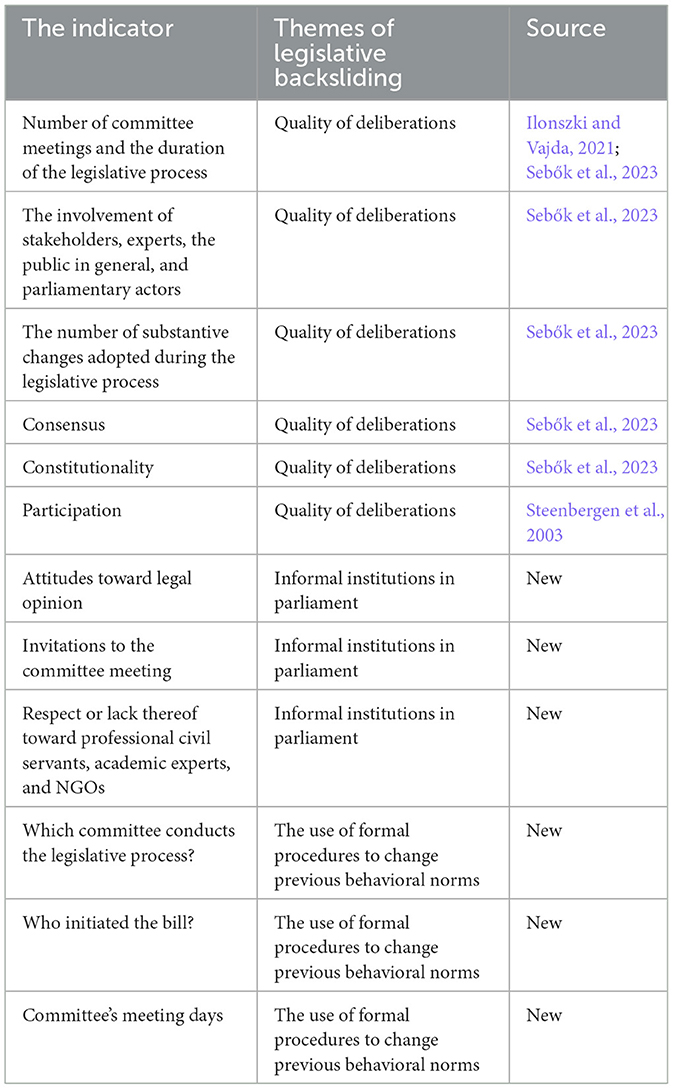

Legislative backsliding

As a phenomenon affecting many people, democratic backsliding has attracted the attention of political scientists in the last two decades (e.g., Waldner and Lust, 2018; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2019). Two recent studies maintained that a critical part in understanding and measuring democratic backsliding is legislative backsliding (Ilonszki and Vajda, 2021; Sebők et al., 2023). They proposed several indicators for measuring legislative backsliding, such as the duration of the legislative process; the involvement of stakeholders, experts, the public in general, and parliamentary actors; the number of substantive changes adopted during the legislative process; the number of committee meetings; and constitutional court decisions regarding the proposed law. Ilonszki and Vajda (2021) found that, in the Hungarian parliament, the legislative process, measured as the number of days from a bill's submission to a final vote, has become shorter since 2010. In addition, by evaluating the dynamics of the legislative process, they found that speed played a significant role in pursuing legal and institutional reform during the 2010–2014 legislative period. Similarly, Sebők et al. (2023) identified several indicators of poor-quality legislation.

Building on this research, I propose adding several more indicators of legislative backsliding: the quality of the deliberations in representative assemblies, the informal institutions in these assemblies, and the use of formal procedures to change previous behavior. With regard to the quality of the deliberations in representative assemblies (Steenbergen et al., 2003), many studies have analyzed the legislative process, including the ability to set an agenda (e.g., Strøm, 2015; Volden and Wiseman, 2018; Wegmann, 2022). However, the deliberative components of the legislative process have attracted less research attention (Schäfer, 2017; Jaramillo and Steiner, 2019). Thus, I emphasize its importance by adding it to assessments of the legislative process. Steenbergen et al. (2003) proposed several indicators for measuring the quality of deliberations. One is participation, which refers to the speaker's ability to participate freely in a debate. Steenbergen et al. (2003) suggested measuring how often a speaker is interrupted, defining such instances as when “a speaker explicitly states that he/she is disturbed by an interruption” (p. 27).

Second, the informal institutions in parliament are an essential part of the legislative process. In recent years, there has been an increase in studies regarding informal institutions in parliament, which are defined as unwritten norms and practices that, along with the formal institutions, shape the political behavior of legislators (e.g., Chappell and Waylen, 2013; Norton, 2019). Chappell and Waylen (2013) indicated that informal institutions include customary elements, traditions, moral values, religious beliefs, and norms of behavior. They are “hidden and embedded in the everyday practices disguised as standard and taken-for-granted” (p. 605). To assess these informal institutions, I will measure three indicators: attitudes toward legal opinions, invitations to committee meetings, and the respect or lack thereof paid to professional civil servants, academic experts, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Legal advisors hold an official professional position in parliament. For example, in the Israeli parliament (the Knesset), one of the legal advisors' duties is to “advise the Knesset and its committees on all matters relating to legislative procedures and work to ensure their integrity” (the Knesset Law Article 17b2).1 Some of the Knesset's legal advisors serve on one committee and others on several other committees. Thus, the committee chair works with the legal advisor daily. While as an elected official, the former is motivated to advance their political agenda, the legal advisor is a professional obligated to the law.

It is an informal behavioral norm to respect professional civil servants, legal advisors, and guests invited to the committee meetings to present their professional opinions regarding the law. It is also an informal behavioral norm to send an invitation to the committee meetings to the legislators a week before the meeting. I would consider displays of a lack of respect toward the legal advisors and professional civil servants, as well as invitations to the legislators to attend the committee meetings sent less than a week before the meeting, as signs of legislative backsliding.

The third indicator I propose adding is formal procedures to change previous behavioral norms. The rules of procedure define the formal regulations that enable legislators to fulfill their roles (Sieberer et al., 2016; Schobess, 2022). Informal behavioral norms are an essential part of legislators' daily life. However, using the formal rules to change or abolish existing informal behavioral norms. I argue that such efforts are part of legislative backsliding. For example, deciding which committee holds hearings about proposed legislation can affect legislative outcomes. In Israel, Basic Laws, which function in place of a constitution, are considered in the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee. However, the Knesset committee can decide to establish a special committee and give it the authority to consider new Basic Laws. This behavior is sporadic. Thus, I propose adding an indicator about which committee considers proposed laws.

Another indicator is who initiated the bill? According to the rules of procedure, the government, a committee, or private individuals can propose bills. The legislative process of private bills is longer, but does not require a legal opinion. In contrast, the legislative process of bills proposed by a committee or the government is shorter but requires a legal opinion.

The last indicator I propose using formal procedures to change previous behavioral norms is the committee's meeting days. According to the rules of procedure, the Israeli parliament, floor works 3 days, from Monday to Wednesday. It has been the norm that committee meetings were held on the same days before the beginning of the floor meeting. On rare occasions, such as when creating the budget, the committee works on Sundays and Thursdays.

Thus, I propose a measure of legislative backsliding that uses 12 indicators. Several of them were used in previous studies, and the rest are innovations of this study (see Table 1). Together, they will help us measure legislative backsliding more comprehensively.

I will use these indicators to test my three hypotheses:

H1: The quality of the deliberative process was better during the 20th Knesset. During the 25th Knesset, the quality has declined.

H2: The informal institutional aspects were respected and implemented more during the 20th Knesset. During the 25th Knesset, there has been a decline in these practices.

H3: Using formal procedures to change previous behavioral norms were more common during the 25th Knesset than the 20th Knesset.

Authoritarian populist rhetoric

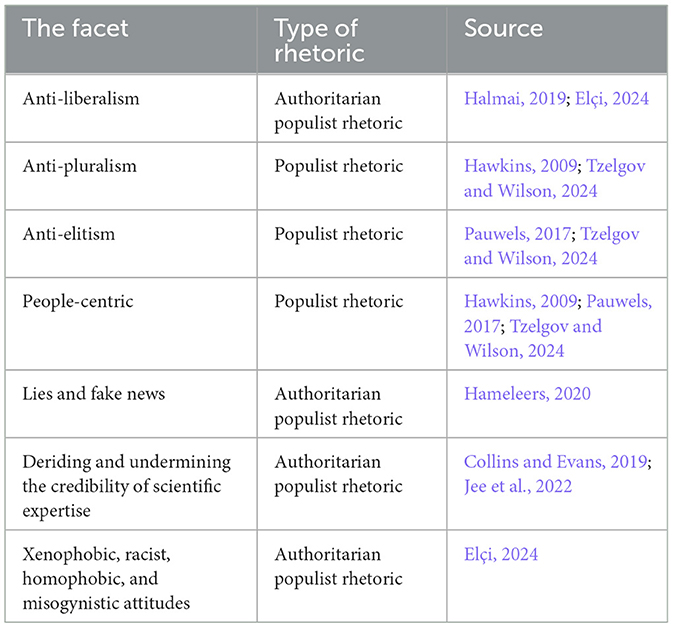

Recent research into populism has led to three dominant definitions of this multifaceted phenomenon: the ideational approach to populism (Hawkins, 2009; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018; Norris and Inglehart, 2019), populism as a strategy (Weyland, 2017), and populism as rhetoric (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Analyzing the many facets of populist rhetoric reveals that the most dominant facet is speech that is people-centric, evident in the emphasis in speeches on the will of the majority, the people's sovereignty, and the people instead of the elite as the only legitimate source of power (Hawkins, 2009; Pauwels, 2017; Tzelgov and Wilson, 2024). An additional facet is anti-pluralism, a stance that creates a distinction between “us” and “them”. It is explicitly aimed at the evil minority that is or was recently in charge and subverted the system for its own interests and against those of the good majority or the people (Hawkins, 2009; Tzelgov and Wilson, 2024). Another facet is anti-elitism, which targets elites such as the media, the judiciary, academia, and other “elite institutions” (Pauwels, 2017; Tzelgov and Wilson, 2024). Even though populism is a multifaceted phenomenon, most previous studies have used just some of these facets in assessing it.

Scholars have differentiated between populism and authoritarianism, arguing that not all populist leaders pose threats to liberal constitutional democracies. It is the authoritarian type of populism that rejects liberalism as a precondition for democracy and does not follow the traditional idea of liberal democratic constitutionalism that poses a threat (Halmai, 2019; Elçi, 2024). Elçi (2024) argued that authoritarian populism is incompatible with the institutions of liberal democracy, such as the rule of law, checks and balances, and minority rights. When populist leaders come to power holding majorities, they weaken or undermine these institutions in the name of the people's sovereignty. Authoritarian populists are intolerant of the groups that pose a threat to their authenticity. They have strong xenophobic, racist, homophobic, and misogynistic attitudes (Elçi, 2024). Authoritarian populists use lies, create “fake news”, and spread disinformation (Hameleers, 2020). Furthermore, authoritarian populist leaders undermine the credibility of scientific expertise, which can threaten their ability to spread lies or misinformation (Collins and Evans, 2019). Previous studies indicated that the erosion of a shared understanding of facts and the credibility of scientific expertise can undermine the deliberative component of democracy (Jee et al., 2022).

Thus, I propose adding several facets to the existing indications of populist rhetoric as people-centric, anti-pluralist, and anti-elitist: the debasement of both political opponents and scientific expertise, lies and fake news, anti-liberalism, which means fighting against the institutions of liberal democracy such as the rule of law, checks and balances, and minority rights, and xenophobic, racist, homophobic, and misogynistic attitudes (Table 2).

I will use these facets to test two more hypotheses:

H4: The debates during the legislative process during the 20th Knesset have fewer facets of authoritarian populist rhetoric than those from the 25th Knesset.

H5: Authoritarian populist rhetoric has been used to justify and legitimize legislative backsliding.

I will examine my five hypotheses by comparing the 20th Knesset term (2015–2020) and the 25th Knesset term (from 2022 till present). I argue that Israel is a good case study for measuring legislative backsliding and authoritarian populist rhetoric for three reasons. First, Israel is a democracy without a constitution, with a weak parliament and a strong executive. One of its weaknesses is due to the ease with which the Basic Laws can be amended. As of 2024, Israel had 13 Basic Laws2 and no constitution in the near future. To amend the Basic Laws, a simple majority of those who are present and vote is required for seven of them, and an absolute majority, meaning more than 60 of the 120 members of the Knesset, is needed to change six of them. Thus, it is relatively easy for any government to change the Basic Laws for its own reasons. Second, previous studies have indicated that Israel has been experiencing democratic backsliding in the last two decades, which was intensified by the regime coup led by the 37th government headed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (Oren, 2023; Akirav, 2024a). Third, scholars have noted that Prime Minister Netanyahu has used populist rhetoric against the Arab citizens of Israel (Keren, 2021; Filc and Pardo, 2023), the media, the judiciary, and other “elite institutions” (Kremnitzer and Shany, 2020; Oren and Waxman, 2022). Keren (2021) argued that the election of 2015 marked the turning point in the use of authoritarian populist rhetoric in Israel.

Materials and methods

To address the five hypotheses of this study, I analyzed 54 protocols, utilizing three Basic Laws. One law was enacted during the 20th Knesset, while two others were amended during the 25th Knesset. In the following section, I will elaborate on the analysis process and discuss the content of each of the Basic Laws selected for this study.

Fourteen Basic Laws were enacted and amended during the 20th Knesset. One was the new Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People, and the rest were amendments to Basic Law: Government, Basic Law: The Knesset, Basic Law: The Budget, Basic Law: The State Economy, and Basic Law: Jerusalem, the Capital of Israel. Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People (henceforth Basic Law: Israel) was the most controversial and attracted much public attention. Thus, I chose to analyze its legislative process.

As of December 2024, six Basic Laws have been amended during the 25th Knesset—Basic Law: Government, Basic Law: The State Economy, Basic Law: The Knesset, and Basic Law: The Judiciary. For the 25th Knesset, I chose to analyze the amendment to Basic Law: The Judiciary abolishing the reasonableness clause (henceforth Basic Law: Judiciary) and the amendment to Basic Law: Government regarding what happens if the prime minister is incapacitated (henceforth Basic Law: Government). I chose these two Basic Laws for two reasons. First, both make significant changes in the checks and balances of the Israeli regime, giving the executive branch more power by reducing the power of the judicial and legislative branches. Second, both were controversial, and many civil protests were held during their legislative process. In addition, the Supreme Court reviewed the three Basic Laws based on petitions filed by NGOs, Members of the Knesset (MKs), political parties, and private citizens.

I also analyzed 54 protocols: 27 meetings (24 in the committee and 3 on the floor) for Basic Law: Israel, 16 meetings (14 in the committee and 2 on the floor) for Basic Law: The Judiciary, and 11 meetings (8 in the committee and 3 on the floor) for Basic Law: Government. The protocols were analyzed in several steps. First, I read all of the protocols. Then, I marked the sentences that represented facets of authoritarian populist rhetoric and the indicators of legislative backsliding.3 My goal was to capture the dynamics and the nature of the discourse during the meetings. Therefore, I did not quantify the text into frequencies as previous studies did. In addition, I conducted several in-depth interviews with experts who participated in the committee meetings regarding these three Basic Laws. The interviews provided a more comprehensive picture of the dynamics of the legislative process and the use of authoritarian populist rhetoric.

Before analyzing the legislative process and the use of authoritarian populist rhetoric in discussions about the three Basic Laws, it is essential to understand each bill's background and context.

Basic law: Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people

During the 18th Knesset (2009–2013), and the 19th Knesset (2013–2015), right-wing MKs proposed similar versions of this bill. Thus, one could argue that the debate regarding the proposal started a few years before the beginning of the legislative process during the 20th Knesset.

However, none of these proposals resulted in a law because the government consisted of center and/or left-wing parties that moderated the right-wing initiatives. The 20th Knesset was the first one comprised of only right-wing parties. The one possible exception was the Kulanu party, which described itself as a centrist political party, even though its founder was a previous member of the right-wing Likud party.

The Arab society in Israel demonstrated against the law, arguing that it had a direct effect on the principle4 of equality, essentially making them second-class citizens. Most Arabs did not participate in the limited number of demonstrations. However, the Arab community that felt most betrayed by the law was the Druze. Since the founding of the State of Israel, they have allied themselves with Israel to the extent that, unlike Muslim and Christian Arabs, the Druze are drafted into the Israeli Army.5 Prime Minister Netanyahu met with the leaders of the Druze community and promised to create a special plan for the Druze community that would ensure Israel's obligation to them.6 However, he would not change the Basic Law as they demanded.

Basic law: government (amendment no. 12, Prime Minister's incapacitation)

There was no previous attempt to amend Basic Law: Government. The coalition chair led several right-wing MKs to propose the amendment in January 2023–April 2023 during the 37th government. They did so out of fear that the Attorney General would declare Prime Minister Netanyahu incapable of serving if he were found guilty at trial.7 During March–April 2023 President Herzog proposed a compromise that he called “the people's directive”8 and asked representatives from the opposition and coalition to sit together and discuss his proposal. Just 7 min after he presented the compromise, the coalition rejected it, arguing it was biased.9

Basic law: the judiciary (amendment no. 5, abolishment of the reasonableness clause)

The regime's coup proposed many anti-democratic laws,10 including a change to Basic Law: The Judiciary, which proposed abolishing the reasonableness clause. There had been no previous attempt to amend this Basic Law this way. The Constitution, Law and Justice Committee headed by MK Simcha Rotman, an extreme right-wing MK, proposed the amendment during the second stage of the regime coup (April 2023–July 2023) after an unsuccessful attempt to amend Basic Law: The Judiciary about the composition of the committee to select judges (Akirav, 2024b).

During the first stage of the regime coup, there were large demonstrations against the proposals, increasing from 120,00 on January 21, 2023 to over 500,000 on March 18, 2023 and 650,000 on March 23.11 During the second stage of the regime coup, the protests increased even though no organization was in charge.12 Akirav (2024a) indicated that the civic protests were huge, non-violent demonstrations that continued nonstop for several months and received news coverage worldwide. People who had never protested joined the demonstrations, attracting participants from all segments of Israeli society.

A review of the attempts to alter these Basic Laws illustrates the process of democratic backsliding in Israel. When the government was comprised of mainly right-wing parties, as in the 25th Knesset, it was easier to try to pass legislation that would change the position of institutions and the checks and balances in the democratic system than it was even during the 20th Knesset.

Results and discussion

Legislative backsliding

In the theoretical framework, I presented 12 indicators within three themes for measuring legislative backsliding. I used all three Basic Laws as mini case studies to analyze each one of the indicators.

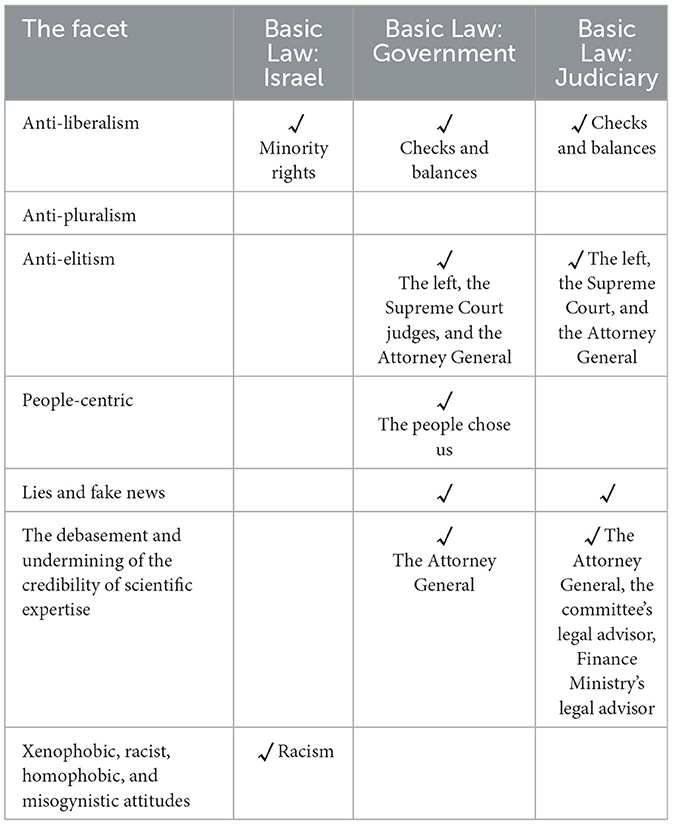

Table 3a depicts the existence or absence of the 12 indicators in each of the Basic Laws. As the table indicates, during discussions about enacting Basic Law: Israel, most of the indicators were evident, demonstrating the quality of the legislative process. In contrast, most of the indicators were absent in the discussions about changes to both Basic Laws—Basic Law: Government and Basic Law: The Judiciary.

Number of committee meetings and the duration of the legislative process

The number of committee meetings and the duration of the legislative process can also serve as indicators of the quality of the legislative process. The optimal situation is one in which many committee meetings last over a long period from the first meeting until the enactment of the law. The amount of time devoted to discussions about the proposed law can indicate whether there was enough time to listen to the MKs and their political attitudes toward the law, listen and learn from various experts about the main issues in the law, debate reservations about the proposed law, and listen to the general public.

The worst situation is one in which there are few committee meetings over a short period from the first meeting until the enactment of the law. This combination can indicate that there was not enough time to engage in the necessary activities described above. Basic Law: Israel had the best combination (24 committee meetings over 435 days), whereas Basic Law: Government (8 committee meetings within 20 days) and Basic Law: The Judiciary (14 committee meetings within 16 days) had the worst combination.

One of the people I interviewed indicated that the length of time between the committee meetings during discussions about Basis Law: Israel gave the participants enough time to understand the main arguments of the debate and prepare for the next committee meeting. In contrast, those who want to push a proposal forward seek to shorten the period for considering it, degrading the quality of the legislative process. Thus, during one of the committee meetings regarding Basic Law: The Judiciary, one of the opposition MKs chastised the chair of the committee, saying:

You want, as the chairman, to shorten the processes of the obligation to submit a bill and a debate on the floor before the preliminary hearing, which is a deliberative stage. You also declared that you intend to bring the bill to a first reading for a vote in the committee at the beginning of next week, and you say—indeed, there are substantial issues—but, we will discuss them after the first reading.13

Opposition MKs continued complaining about the intensity of the committee meetings that lasted day after day for long hours at every meeting. One complained: “There is a very fast legislative process here. This does not meet the standards of a proper process. I ask the legal advisor of both the committee and the Knesset to look at the data I presented to you yesterday on the number of meetings and the duration of the discussions, and to re-examine your position”.14 Another MK asked the committee chair to postpone the committee meeting for a few days because of a military operation, but the committee chair refused. Before voting for the committee's first hearing, an opposition MK argued, “There is a process here of trampling on the Knesset's regulations. You know how incomplete and inappropriate this debate is. I expect you (the legal advisor) to make a clear statement. Any vote (first hearing) today on this law is a complete disgrace to the Knesset”.15

The very short duration of the legislative process for Basic Law: Government did not allow for extensive discussions regarding the purpose of the amendment. Indeed, most of the discussions were mainly about procedures. They did not deal with the possibility that opposition members would fail to cooperate with the coalition even if the prime minister were incapacitated. At the end of July 2023, Prime Minister Netanyahu had a medical procedure that made him incapable of being in office for a few hours. The government decided that the justice minister should replace Netanyahu during the medical procedure. Based on the amendment, this decision needed the approval of two-thirds of the Knesset committee, meaning the opposition's cooperation to pass it. However, the Knesset committee first met 2 days after the medical procedure. The opposition MKs stated that the government was operating without authority16 and refused to approve the government's decision. Hence, the Knesset committee chair decided to postpone the discussion to Sunday to develop a better procedure for dealing with the inability of the prime minister to serve.17 Thus, in practice, Israel did not have a functioning prime minister during this period.

The involvement of stakeholders, experts, the public in general, and parliamentary actors

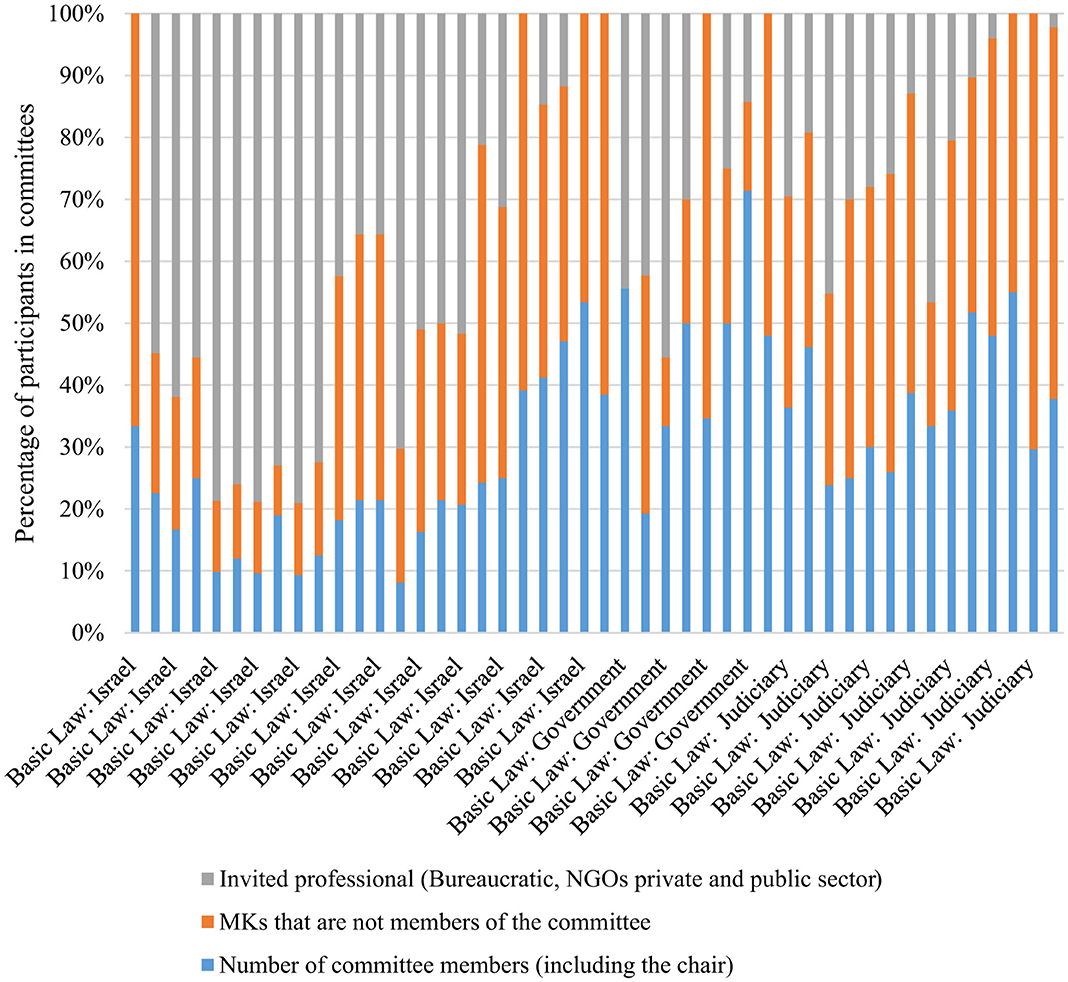

The composition of the participants in the committee meetings is an additional indicator of the quality of the legislative process. Including professional experts, interest groups, and representatives from the public sector and academia can enrich the deliberative component of the legislative process. However, MKs can come to a committee meeting just for the vote and be absent during the entire discussion, or come just for a few minutes to register as a participant in the committee's protocol and then leave.

Figure 1 illustrates the mixture of guests, committee members, and MKs who attended discussions about the three Basic Laws. The discussions about Basic Law: Israel included more invited guests than those about the other two Basic Laws.

Among the guests were experts from NGOs and academia, other stakeholders, and representatives from grassroots organizations. Note that several NGOs participated in almost every meeting. These NGOs have the time and the resources to write and present professional opinions for the debates. During the committee meeting regarding Basic Law: The Judiciary, the guests presented cases in which the reasonableness clause helped them receive justice, because the government's decision violated their civil and human rights. Their main argument was that it is essential to keep the reasonableness clause. Otherwise, they would be unprotected from arbitrary government decisions.18

The number of substantive changes adopted during the legislative process

Substantive changes can indicate that both sides have listened to each other, deliberated, and compromised. Several substantive changes were made to Basic Law: Israel. In contrast, Basic Law: Government had only one change, and Basic Law: The Judiciary had none. This lack of changes to the original law suggests legislative backsliding.

Several substantive changes were adopted during the discussions about Basic Law: Israel. First, the committee decided to exclude Article 1(c), which the Attorney General referred to as “interpretative supremacy”, because, in practice, it could override any other law, including the Basic Laws. As such, it had the potential to violate human and civil rights. Second, the committee restated the purpose of the law. In the proposal it said: “This Basic Law aims to protect Israel's status as the nation-state of the Jewish people, in order to anchor in a Basic Law the values of the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state in the spirit of the principles contained in the Declaration of Independence of Israel”.19 However, the enacted law ended after the word “state”, omitting the section about the spirit of the Declaration of Independence and the word “democratic”, which promised equality for minorities in Israel. Third, the discussions also resulted in the omission of the article ensuring the preservation of people's heritage: “Every resident of Israel, regardless of religion or nationality, is entitled to work to preserve his culture, heritage, language, and identity”. Fourth, as a result of the discussions, the proposed article about protecting holy places was also omitted: “The holy places will be protected from desecration and any other harm and from anything that may harm the freedom of access of members of religions to the sacred places or their feelings towards those places”.

All of these four changes affect the human and civil rights of the Arab citizens of Israel. Previous studies have analyzed the consequences of the law for the civil and human rights of Arab society in Israel (e.g., Wattad, 2021; Roznai and Cohen, 2023). They indicated that it represented a significant legislative effort to target the Arab minority in Israel. The law also encouraged the friend-enemy discourse and strengthened anti-democratic trends in Israel. Studies have also argued that the law aligned with the views of the Israeli populist movement.

The Israel Democracy Institute prepared a report that presented its professional analysis of the proposed bill.20 In addition to the consequences of the law noted above, the report indicated that Article 1321 limited the ability of the court to find an answer within the existing system and determined that the court would rely on Hebrew law. This article was excluded from the final version of the law. Thus, we can say that the four substantive changes adopted during the legislative process worked against the Arab minority in Israel. In contrast, the fifth substantive change helped keep the judiciary's decisions within the legal system.

There was just one substantive change that was adopted during the legislative process of Basic Law: Government—the exclusion of Article b1(3): “The court, including the Supreme Court sitting as a High Court of Justice, shall not discuss a petition to declare the Prime Minister incapacitated or to confirm it. Any such decision or order of the court shall be without authority and shall be of no validity”. This article tried to override the court's authority to discuss the issue of whether the prime minister was incapacitated. During one of the committee meetings, the committee chair indicated, “The Attorney General argued that this article makes the law unconstitutional … and the opposition members presented similar argument we decided after discussion to remove this article”.22 Additional, but not substantive changes, included more details regarding the options and procedures when declaring the prime minister incapacitated.

No substantive changes were adopted during the legislative process of passing Basic Law: The Judiciary. Thus, the bill that was proposed was essentially the same as the law that was passed. One of my interviewees indicated that even though the professional experts presented a situation in which the reasonableness clause was needed (for example, during a caretaker government) and the committee chair agreed with its logic, he did not agree to change the proposed amendment. Furthermore, the committee's legal advisor suggested several compromises as solutions. Other professional experts, including a former Justice Minister who was a law professor,23 proposed additional mechanisms to keep the reasonableness clause but to moderate it.24 However, none of the suggestions was accepted. After the first hearing on the floor, the committee chair said:

The bill passed on first reading. We had a long and comprehensive debate on it. As we hear ideas and suggestions during the discussions here to improve the bill or clarify the intent, it is better. Of course, we will take them. But the essence is, 64 Knesset members voted in favor of it yesterday. Therefore, we are moving towards the second and third readings.25

The indicator of substantive change can signify whether the deliberative component was present in the legislative process. Steenbergen et al. (2003) stated that if there is no attempt at compromise, reconciliation, or consensus building, the deliberative component does not exist. They described such a situation as constrictive politics. If there are alternative or mediating proposals, the deliberative component does exist. However, the content of the substantive changes is an additional indication of the quality of the deliberative element. In our cases, if the content of the substantive changes ensured the civil and human rights of minorities and the essence of democratic principles, and maintained the system of checks and balances, the deliberative component had quality. In contrast, the deliberative component was flawed if the changes harmed these values.

Some might argue that the discussions about Basic Law: Israel were long enough to allow various groups to present their views. However, I maintain that the deliberative component of it was flawed because the essential changes hurt the civil rights of the minority. Given that the discussions for the two other Basic Laws were very short and resulted in no or almost no substantive changes, I contend that here, too, the deliberative component was flawed.

Consensus

Sebők et al. (2023) defined consensus as joint proposals of government and opposition MPs. One method of measuring consensus is the number of joint proposals and the number of accepted opposition proposals. Brandeis Institute published a working paper in 202426 comparing the patterns of legislation of the 25th Knesset to previous Knesset terms. It indicated that over time, there had been a moderate increase in the number of private bills initiated by coalition and opposition MKs, meeting Sebők et al.'s (2023) definition of consensus. However, this pattern changed during the 25th Knesset, leading to a significant decline in the cooperation between coalition and opposition MKs. All three Basic Laws were initiated only by MKs from the coalition. Thus, no consensus existed.

Constitutionality

NGOs, MKs, political parties, and private citizens filed petitions with the Supreme Court against each of the three Basic Laws. However, each received a different Supreme Court decision.

About Basic Law: Israel, 11 out of the 15 Supreme Court judges participated in the discussion. Ten of the 11 voted against the petitions, claiming there was no reason to abolish the Basic Law, which was intended to “anchor the state's identity as Jewish, without detracting from its democratic identity”. One of my interviewees indicated that the long duration of the legislative process, with experts presenting their professional opinions and MKs presenting their political views, resulted in a compromise version of the law. This compromise enabled the Supreme Court to interpret the law based on previous Supreme Court decisions and in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. The only judge who voted to abolish the Basic Law was Judge George Karra, himself an Israeli Arab, who argued: “The law's disregard for Arabs and Druze intensifies the violation of the principle of equality”.27

The Supreme Court published its decisions about the two other Basic Laws in January 2024. The two decisions relied on another decision of the Supreme Court published on the same day, maintaining that the court had the right to abolish Basic Laws and intervene in exceptional and extreme cases in which the Knesset had exceeded its authority. Twelve of the 15 Supreme Court judges approved this decision.28 Thus, the Supreme Court decided that the amendment to Basic Law: Government regarding the prime minister's inability to fulfill their position would be in effect starting only in the next Knesset term, because it was aimed at a particular individual, which constituted an abuse of the Knesset's authority.29 In addition, for the first time since Israel's establishment, the Supreme Court invalidated the Basic Law that abolished the reasonableness clause for its decisions.30 One of my interviewees argued that the amendment of Basic Law: Government was a poor solution for dealing with the prime minister's being incapacitated. He maintained that a better solution needed to be found because the amendment was still on the books and would be used in the 26th Knesset.

Participation

During the legislative process of Basic Law: Israel, there were no explicit interruptions as Steenbergen et al. (2003) defined them. However, there were several instances in which the committee chair ordered the removal of opposition MKs from the debate because of non-stop interruptions of the discussion.31 During the floor hearing, there were several times when the Speaker asked MKs to stop interrupting, or he would order their removal from the floor.32

During the legislative process of Basic Law: Government again, there were no explicit interruptions as Steenbergen et al. (2003) defined them. However, during one of the committee meetings, the committee chair interrupted an opposition MK's talk during the debate. She noted: “You interrupted me; you should protect my right to talk, not interrupt”.33

The appearance of this indicator was dramatically different during the legislative process of Basic Law: The Judiciary. The committee chair told MKs that they were interrupting him and if they continued, he would ask to remove them from the meeting.34 One of the opposition MKs said to the committee chair: “Look how many MKs you removed from the committee”.35 On several occasions, opposition MKs noted that other MKs were interrupting them, making it difficult for them to hear the discussions, understand what they were voting for,36 and participate.37 During one of the committee meetings, the chair complained that the MKs interrupted him and other MKs because the chair did not recognize them and gave them the right to talk.38 One of my interviewees contended that the committee chair had created a sham deliberation process. While everyone had time to present their opinion, MKs and professionals as well, the chair limited the ability to ask questions, deliberate, and obtain answers. For example, when opposition MKs tried to ask the professional guests questions about the opinions they presented, the committee chair called them to order. Thus, one of the opposition MKs asked why a practical question was an interruption39?

Attitudes toward legal opinions

During the legislative process of Basic Law: Israel, civil servants from the Justice Ministry participated in the committee meetings, as did the Attorney General's deputy, the Knesset's legal advisor, and the committee's legal advisor. They received time during the meetings to present their legal opinions and answer questions that coalition and opposition MKs raised. One of my interviewees, who was a legal advisor and attended the meetings, indicated that the legal opinions were respected. MKs listened to the professional opinions and asked questions to clarify the legal implications and meanings of the legal opinions. My interviewee also noted that they had enough time to prepare their legal opinions because of the long duration of the legislative process.

The story of the 25th Knesset was different. During the first meeting of the legislative process of Basic Law: Government, opposition MKs asked for the legal opinion of the committee's legal advisor, which is a basic norm in any legislative process. The committee legal advisor answered, “The tight schedule required us to hold the debate and present the legal opinion at the same time”.40 During the debates, the Attorney General's deputy presented the legal opinion regarding the proposed legislation, indicating, “You created normative black holes in the bill. The lack of judiciary overview of government decisions creates essential obstacles including significant violations of the rule of law”.41

In another committee meeting, the Attorney General's deputy indicated:

During the discussions that took place in the committee in the last two weeks, significant changes occurred in the proposal … At the same time, and today's discussion also shows that all the changes that have been made are not enough to cure the essential difficulties inherent in the arrangement. In particular, what bothers us is the concern that the bill is intended to change the existing legal situation in preparation for a specific, pending judicial proceeding, in which the petitioners are requesting that the court declare that the Prime Minister is unable to fulfill his duties due to the criminal proceeding being conducted against him.42

He went on to say, “The proposal is significantly personal… this raises concerns about the abuse of the Knesset's constituent authority”.43 The committee did not accept this professional opinion and passed the amendment.

Similarly, during the legislative process of Basic Law: The Judiciary, the legal advisor presented his professional opinion regarding the law, but the committee chair did not accept it. For example, the committee's legal advisor indicated, “Our concern is that the removal of the entire echelon from the reasonableness clause could leave important areas of government activity without effective oversight by the court, when the other causes do not provide a sufficient response”.44 The committee chair interrupted the legal advisor several times when the legal advisor tried to explain the court's authority.45 The committee chair also interrupted the Attorney General's deputy when he read the Supreme Court decision whose content the committee members were arguing about. Then the Attorney General's deputy asked to present the professional opinion he had prepared, but the committee chair interrupted him again.

In another committee meeting the Attorney General deputy said, “What is at stake is giving the government, the Prime Minister, his ministers, and other elected officials—and only them—the permission to make arbitrary decisions, that is, decisions that ignore relevant facts and considerations or that give extremely exaggerated weight to the importance of negligible considerations”. He continued his legal opinion and argued that, “The purpose of the proposal is to create a normative black hole. This means that it will create a serious breach in the basic values of Israeli democracy—the correctness of the administrator's activities, the purity of the public service, the fairness of the government in its relations with the individual, and the rule of law”.46 He also offered a compromise: “Our proposal is to provide an exception for any decision that directly affects an individual, whether it is what is called in the literature an individual's right or what is called an individual's interest”.47 In another committee meeting the committee's legal advisor presented facts about the frequent use of the reasonableness clause. However, the committee chair continued, arguing, “the Supreme Court is not able to limit itself ”,48 which is the opposite conclusion from the facts that the legal advisor presented.

During the committee meetings, opposition MKs asked several times about inviting the legal advisors of the ministries to learn about the law's potential effects. The committee chair noted, “Opposition members requested that the Finance Ministry's legal advisor be invited to the committee, and the committee director invited him. I thought otherwise.”49 The Finance Ministry's legal advisor emphasized:

I have been in the Ministry of Finance for 21 years in various positions in the Legal Bureau. I have been invited by various committees in the Knesset on a wide range of matters to hear my legal advice. In some there was a government position, in some there was no government position. There is no government position on this specific matter. There has never been a discussion in the government about this proposal and its implications for government ministries. In light of the committee's request, which requested to hear the implications of the proposed amendment on a number of government ministries, including the Ministry of Finance, I found it appropriate to respond to the request and I will address it from professional position as legal advisor.50

The Attorney General's deputy indicated, “The vast majority of experts who appeared before the committee insisted that the proposed bill was too broad and sweeping. In fact, it is the most extreme proposal possible to address the reasonableness issue.”51

All the legal opinions were against the proposed amendments in Basic Law: Government and Basic Law: The Judiciary, but the coalition MKs, headed by the committees' chairs, ignored them.

Invitations to the committee meeting

The committee's secretariat usually sends an invitation to the committee members with the agenda for the meeting at least a week before the meeting. It is an informal norm. However, to invite a civil servant, minister, or anyone who is part of the executive branch to the meeting, the invitation must be sent at least a week before the meeting (Rules of Procedure, Chapter Seven, Article 123(f)).52 The purpose of inviting professional experts is to enrich the committee debates and hear several points of view. Several NGOs regularly participate as experts in committee debates, while experts from academia or other organizations (whether in the private or public sector) participate less frequently.

During the legislative process of Basic Law: Israel, committee meetings were scheduled with intervals of a week or two, sometimes even more, depending on the agenda of the meeting. Thus, there was enough time for experts and civil servants to prepare their professional opinions. One of my interviewees indicated that, based on the arguments raised in the committee meetings, they were able to prepare more precise documents for the next meeting, because they had enough time.

The story of the 25th Knesset was different. During the first meeting of the legislative process for Basic Law: Government, one of the opposition MKs told the committee chair: “The invitation was sent yesterday; it is from today to tomorrow; it doesn't work like that”.53 This short notice challenged the ability of experts to attend the meeting and to prepare their professional opinions. During the first committee meeting of the legislative process for Basic Law: The Judiciary, one of the opposition MKs asked about the schedule of the committee meetings, but did not receive an answer from the committee chair.

Respect or lack thereof for professional civil servants, academic experts, and NGOs

I previously indicated that it is an informal behavioral norm to respect professional civil servants, legal advisors, and guests invited to the committee meetings to present their professional opinions regarding the law. This respect is part of the quality of the deliberative component of the legislative process. This norm of respect existed during the legislative process of Basic Law: Israel. The professional guests received the time they needed to present their professional opinions. MKs asked questions to clarify these professional opinions, and the discussions were respectful. However, this norm changed during the legislative process of Basic Law: Government, and even more so during the legislative process of Basic Law: The Judiciary.

Several times during the legislative process of Basic Law: Government, the committee chair accused the Attorney General of operating against the government. In one of the committee meetings, the deputy advisor of the Attorney General who participated in that meeting answered: “She's practical, she's professional and she's a jurist.”54 We can see that the disrespect was based on the authoritarian populist rhetoric of debasement.

The committee meetings about Basic Law: The Judiciary were especially rushed. Many professionals invited to the discussions did not have enough time to present their professional opinions fully. The committee chair, who interrupted one of them several times, asking him to conclude his presentation. Thus, after shortening the presentation, he said, “I have much more to say and I hope that in the following meetings I will be allowed to present them.”55 During one of the committee meetings, 6 out of 12 guests invited to the meeting did not receive the right or the time to talk. Thus, in the following meeting, one of the opposition MKs indicated that not all organizations with position papers had received an opportunity to present them. The committee chair argued that such was not the case.56 In another committee meeting, an opposition MK indicated that the Attorney General's deputy was sitting outside the committee room, and it was unacceptable to start the committee meeting without him.57

In one of the committee meetings, one of the guests, a law professor, indicated,

I think this is a law that is at best carelessly drafted, at worst deliberately drafted in a cover-up … the purpose of this law is very simple: to allow the government, and in some cases ministers as well, immunity from judicial review of appointments. This law is intended to legalize the appointment of MK Deri as a minister. This law is intended to allow the government to fire the Attorney General and other gatekeepers in a way that will allow it to operate free from restrictions.58

The disrespect for professional guests was also evident when the committee chair replied to the examples the Finance Ministry's legal advisor presented, saying: “Most of the examples you gave are theoretical and unfounded. Completely unfounded”. One of the opposition MKs replied that the chair was demonstrating contempt for the legal professional and its advice.59 In the following meeting, the Finance Ministry's legal advisor said: “The allegations of the politicization of my position are unacceptable and it would be better if they were not made”.60

Which committee hosts the legislative process?

Based on the rules of procedure, Basic Laws are enacted and amended in the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee (Part H, Chapter 1, Article 100(6)). However, only Basic Law: The Judiciary was amended in this committee. In contrast, a joint committee of the Knesset Committee and the Committee on the Constitution, Law and Justice was created to discuss Basic Law: Israel. Similarly, a special committee was established based on Article 108 in the rules of procedure to discuss Basic Law: Government. Establishing a special committee to amend Basic Laws is rare. Indeed, since the first Knesset, it has happened only twice in the 25th Knesset. The second special committee was established on December 14, 2022. Before the formation of the government, a special committee was established to amend Basic Law: Government regarding an additional minister in a ministry and the competence of ministers. No previous governments had held hearings about Basic Laws in any committee other than the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee. Circumventing this committee by holding the hearings in a different committee was a formal procedure that the government used to change previous norms in the Knesset. Indeed, during one of the special committee meetings to amend Basic Law: Government, one of the opposition MKs indicated, “All this debate supposed to be in the Constitution, Law and Justice committee.”61

Who initiated the bill?

Private member bills have significantly fewer requirements than government bills in terms of their impact assessments. The government proposed none of the three Basic Laws. Two were private members' bills (Basic Law: Israel and Basic Law: Government). Basic Law: The Judiciary was proposed by the chair of the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee. Based on the rules of procedure, the legislative process of private bills involves more stages. In addition, private bills do not have to receive a legal opinion, as government bills must.

During the committee meeting of the special committee for Basic Law: Government, one of the opposition MKs indicated, “If you (the coalition) wanted to legislate for the greater good, you should propose a government bill, not a private bill”.62

During one of the committee meetings of Basic Law: The Judiciary, one of the opposition MKs addressed the committee chair and said:

You are making very unusual use of the tool of bills on behalf of the committee. Because this tool has been used very limitedly in the past. A bill is brought here; we do not discuss the question of whether it is appropriate to have a bill from the committee. Is this an issue on which the committee wants to act together as a committee or is this a proposal that should be a government or private proposal? The chairman of the committee chooses to bypass the procedures for a government proposal or a private proposal, with the deliberate intention of carrying out a legislative blitz here.63

The opposition MK argued that since the committee initiated the bill, he wanted to receive all documents before the first hearing. He asked the legal advisor to insist that there would be no first hearing before having all of the facts regarding the bill. He concluded by saying, “Your detours to promote your rather delusional and extreme private legislation by taking advantage of your seat in the committee's chair are sabotaging the Knesset's rules”.64 During another committee meeting, one of the opposition MKs argued, “You don't propose a government bill just to avoid hearing the opinions of government ministers and professional bodies who probably oppose it”.65 Finally, another opposition MK noted repeatedly: “This is not a proposal from the committee by definition. This is a government proposal… They are deceiving the Knesset.”66

Committee's meeting days

The rules of procedure define the days on which the Knesset works: Monday to Wednesday. There is no similar article for the committee meeting days. However, the informal norm is that committee meetings are held during the Knesset's work days. In special cases, such as discussing the budget, committee meetings are held on Sundays and Thursdays.

When discussing Basic Law: Israel, 22 out of 24 (91%) committee meetings were held on Monday to Wednesday, and just 9% were on Thursday and Sunday. Thus, the committee chair, a coalition MK, respected the informal norm that committee meetings are usually held during the floor days.

The story of the 25th Knesset was different. When discussing Basic Law: Government and Basic Law: The Judiciary, 62.5 and 21%, respectively, of the committee meetings were held on Sundays and Thursdays. This high percentage infuriated one of the opposition MKs, who said: “Don't play dumb and don't tell the public that the Knesset works on Thursdays. You know very well that it's not true”.67 After consulting the committee's legal advisor, the committee's chair replied: “We checked the rules of procedures and we didn't find any article about Sunday and Thursday, which means that we can meet during these days”.68 Then the committee's legal advisor clarified, “It is true that there is no article about the days of committee meeting but for the record it is important to say that the norm was to meet on Sunday and/or Thursday in urgent cases only.”69

It was not just the changes in the informal norms regarding the days of the committee meetings. There were also changes to the hours of the meetings. During the discussions about Basic Law: Israel and Basic Law: Government, the meetings lasted between one and a half and 3.5 h. However, the meetings about Basic Law: The Judiciary lasted 6–7 h. One of the committee meetings started at 5:00 p.m. and ended after midnight. Another committee meeting started at 2:20 a.m. and ended at 11:50 a.m. The opposition MKs complained about the long hours of the committee meetings.70 Marathon meetings are rare and are used mainly during the debate regarding the budget.

Thus, the data about the 12 indicators support my three hypotheses about legislative backsliding. The quality of the deliberative process was better during the 20th Knesset, whereas during the 25th Knesset, the quality declined (H1). The informal institutional aspects were respected and implemented more during the 20th Knesset than during the 25th Knesset (H2). Finally, the 25th Knesset made more extensive use of formal procedures to change previous behavioral norms than the 20th Knesset did (H3). Therefore, I maintain that the Israeli parliament, which is considered a weak parliament controlled by the executive, is experiencing legislative backsliding in its 25th term, which has weakened it even more.

Authoritarian populist rhetoric

In the theoretical framework, I indicated that authoritarian populist rhetoric has seven facets: anti-liberalism, anti-pluralism, anti-elitism, people-centrism, the use of lies, fake news, and disinformation, and the debasement and undermining of the credibility of scientific expertise. Furthermore, such rhetoric expresses strong xenophobic, racist, homophobic, and misogynistic attitudes. I used these factors to assess legislative backsliding, which was evident in discussions about the three Basic Laws.

Table 3b depicts the main facets of the authoritarian populist rhetoric used in discussions about passing these Basic Laws. It is very clear that the talks about Basic Law: Israel contained only two facets out of the seven. In contrast, the discussions about Basic Law: Government and Basic Law: The Judiciary contained almost all of the facets of authoritarian populist rhetoric.

Anti-liberalism

Anti-liberalism appeared in all three Basic Laws, but with a different emphasis. In Basic Law: Israel, it was evident in the implications for the Arab citizens of Israel. For example, one of the Arab MKs asked: “Is this (Israel) our homeland? Our state?”71 Another Arab MK noted: “The Arab population is not part of this law … It makes us second class citizens.”72 During the first hearing on the floor, one of the Arab MKs tore up the paper on which the proposed law was written.73 After the bill was passed, the Arab MKs tore up the law and were removed from the floor by the Speaker.74

In both Basic Law: Government and Basic Law: The Judiciary, anti-liberalism was evident in the changes in the system of checks and balances. For example, one of the opposition MKs claimed, “The government seeks to eliminate the checks and balances that limit its activities”.75 “The way you have been behaving over the past six months is an example of there being no separation of powers. Only the government has control—not the Knesset and the courts.”76

Anti-elitism

Anti-elitism was not evident in Basic Law: Israel, but appeared frequently in the two other Basic Laws. The elite groups included the Supreme Court, the left, and senior officials. For example, when the committee chair presented Basic Law: Government during the preliminary hearing on the floor, he argued that it was for: “All the unelected people trying to stage a coup here under the guise of the slogan ‘rule of law'”.77 During one of the committee meetings the committee chair indicated, “We will not, under any circumstances, allow a coup here of any senior official”.78 This rhetoric was more explicit during the discussions about Basic Law: The Judiciary. For example, one of the coalition MKs claimed, “All government officials are left-wing. Left, left, left. All government officials, all senior positions are filled by leftists”.79 Another coalition MK argued, “There is nothing more anti-democratic than the authority given to a judge by the pretext of reasonableness; a capricious power, without any subordination to any law. There is no law, there is only a judge”.80 During the first hearing on the floor the coalition chair claimed, “A group arose here that decided that they were the state, the masters of the land—their army, our livelihoods, their academia, their business sector, their healthcare system, everything”81 and “The left in Israel decided to overthrow the government in Israel by framing the prime minister”.82

People-centric

Basic Law: Israel did not contain people-centric rhetoric, but it was pretty evident in the two other Basic Laws. For example, during the preliminary hearing on the floor when the committee chair presented Basic Law: Government, he argued, “They are unable to accept the results of the elections; they cannot come to terms with the idea that the majority of the people do not think like them, that what the people choose does not actually align with the elite”.83 He also said: “The people and their representatives appoint the Prime Minister and only the people and their representatives”.84 The main reiterated message was that “we have the people behind us. The people chose us”.85 Similar rhetoric was used during the Basic Law: The Judiciary discussions. For example, “Reasonable? The public will monitor it, determine it in the elections. If a government has made unreasonable decisions, the public will replace it … The rule of the people, not the rule of a single person, not the rule of a judge.”86

Lies and fake news

Here again, lies and fake news were not featured in Basic Law: Israel, but they appeared frequently in the two other Basic Laws. For example, some claimed that “he was framed”87 or “Protest organizers offer 250 shekels to anyone who brings the car and drives slowly”.88 During one of the committee meetings discussing Basic Law: The Judiciary, one of the opposition MKs indicated, “We are angry because the committee chair present fake facts and doesn't want to hear the true facts”.89 Another MK claimed that the reasonableness clause was not partisan and asked people to stop repeating this lie. In contrast, another MK continued arguing that the reasonableness clause served just one political wing.90 During one of the committee meetings, MKs presented untrue examples, which caused arguments between opposition and coalition MKs.91 For example, one of the arguments was about the number of times the Supreme Court had abolished laws based on the reasonableness clause. The committee chair argued: “If the Supreme Court hadn't abolished so many laws”,92 so the committee MKs asked him how many laws the Supreme Court had abolished. He replied: “First, it doesn't matter, second too many”.93 The committee advisor indicated that in the last 10 years, the Supreme Court had invalidated 200 petitions, or 20 a year. Only 25% were based on the reasonableness clause, which means 2.5 per year.94 When one of the opposition MKs told the committee chair, “You said that it is a fact that there are too many Supreme Court decisions using the reasonableness clause”, the committee chair replied, “I made no factual claim”.95

Another lie the coalition MKs repeated was about the small number of people participating in the demonstrations. One noted, “except for a few, the public stays away from these demonstrations”.96 An opposition MK replied that there were masses of Israeli citizens in the demonstration, but the coalition MK continued saying that the public did not attend the demonstrations.97 In the first hearing on the floor, the coalition chair repeated the same lie: “those 10,000 fat people who go out to block roads”.98 During the legislative process, opposition MKs gave several examples of facts instead of the lies the coalition MKs presented.99

The debasement and undermining of the credibility of scientific expertise

Finally, once again, this facet did not appear during the discussions about Basic Law: Israel, whereas it seemed frequently with regard to the two other Basic Laws. For example, during the discussions about Basic Law: Government, the committee chair disparaged the Attorney General and undermined her authority. For instance, he said: “So keep trying, with your legal advisor, your political advisor Gali Baharav Miyara,”100 “I speak out against her, she thinks she's the sheriff of the state”,101 and “Could it be that she is not a legal advisor at all but a political advisor for you?”102 During the discussions about Basic Law: The Judiciary, the committee chair used the debasement strategy in two ways. First, he did not invite legal advisors from leading government ministries to present their legal opinions, even though opposition MKs asked him to do so several times. Second, when experts and legal advisors presented their professional opinions, the chair accused them of being political and constantly interrupted them. For example, one of the opposition MKs indicated, “You did not invite legal advisors from leading government ministries. The legislative blitz was accompanied by parliamentary bullying, the serial expulsion of Knesset members, their silencing, the silencing of legal advisors, and experts from academia and civil society”.103 During one of the committee meetings, the committee chair interrupted the committee's legal advisor several times when the latter continued pointing to the lack of definition of reasonableness.104 In the first hearing on the floor, the coalition chair said: “Who turned this group of anarchists into the masters of the country? Who supports public disorder, roadblocks, violence against police officers, and destruction of property? Who if not the Attorney General?”105

Xenophobic, racist, homophobic, and misogynistic attitudes

This facet was evident in the discussions about Basic Law: Israel, but not those involving the two other Basic Laws. Opposition MKs (mainly Arab MKs) used the phrases “Racist government” and “apartheid”106 many times during the debates on the floor and in the committee.

Thus, the data about the seven indicators support my two hypotheses about legislative backsliding. The debates during the 20th Knesset had fewer facets of authoritarian populist rhetoric than those from the 25th Knesset (H4). In addition, authoritarian populist rhetoric has been used to justify and legitimize legislative backsliding (H5).

Conclusion

This study presents a novel approach that includes new methods for measuring legislative backsliding and authoritarian populist rhetoric.

Based on these comprehensive new measurements, I was able to test my hypotheses and confirmed that authoritarian populist rhetoric has been used to justify and legitimize legislative backsliding in Israel. It is important to note that Israel is not the only Western democracy that has experienced leadership by an authoritarian populist leader. Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States (from January 2025) are headed by authoritarian populist leaders. Thus, scholars should ask whether these countries are experiencing similar legislative backsliding. Second, there might be additional factors that explain legislative backsliding or the use of authoritarian populist rhetoric. For example, affective polarization or critical events such as pandemics, wars, or waves of migrants entering a country can affect both variables. Future studies should use the measurements to look for similar patterns in Western democracies and include more variables that can explain legislative backsliding.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

All the participants initially provided verbal informed consent and retrospectively provided written informed consent.

Author contributions

OA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/law00/72263.htm

2. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/en/activity/pages/basiclaws.aspx

3. ^The indicators and facets are in Tables 1, 2.

4. ^https://www.inss.org.il/he/publication/the-arab-society-in-israel-and-the-nation-state-law/

5. ^https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politi/2018-08-04/ty-article/0000017f-e8ae-df5f-a17f-fbfe3fea0000

6. ^https://www.kan.org.il/content/kan-news/politic/242343/

7. ^https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/hji4bzt2s

8. ^https://www.mitve-haam.org/

9. ^https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/rynhsqye3

10. ^For more details about the anti-democratic laws see the analysis of the Political Scientists Forum for Israeli Democracy. https://www.psfidemocracy.org/

11. ^The numbers come from news reports and reports from the leaders of the protests.

12. ^Several forums consisting of professors of law, economics and political science, reserve soldiers, and NGOs supporting civil and human rights joined forces to oppose the reform.

13. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207600 p. 43.

14. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207872 p. 42.

15. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207919 p. 6.

16. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/activity/committees/knesset/news/pages/25.7-%d7%a0%d7%91%d7%a6%d7%a8%d7%95%d7%aa.aspx

17. ^https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/skgnd8pq3

18. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207602

19. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Legislation/Laws/Pages/LawBill.aspx?t=lawsuggestionssearch&lawitemid=565913

20. ^https://brandeis.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%99%D7%A8-%D7%9E%D7%97%D7%A7%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%A5-%D7%97%D7%A7%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%94.pdf

21. ^“If the court sees a legal question that requires a decision, and does not find an answer to it in existing legislation, by settled law or by means of clear inference, it will decide it in light of the principles of freedom, justice, fairness, and peace of Israel's heritage.”

22. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Committees/BasicGov/Pages/CommitteeAgenda.aspx?tab=3&ItemID=2203355 p. 20.

23. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207602 p. 107–108.

24. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207919 p. 45 and https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651 p. 91.

25. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651 p. 54.

26. ^https://brandeis.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%99%D7%A8-%D7%9E%D7%97%D7%A7%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%A5-%D7%97%D7%A7%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%94.pdf

27. ^https://news.walla.co.il/item/3446900

28. ^https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/sjngl00eoa

29. ^https://www.israelhayom.co.il/news/law/article/15033342

30. ^https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/by211zveo6

31. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2073485 p. 9.

32. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2016214/2884199

33. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202842

34. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651

35. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p. 76.

36. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208910

37. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p. 21.

38. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207600 p. 21–23.

39. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207919 p. 33, 35.

40. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202655

41. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202655

42. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2203525 p. 35.

43. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2203525 p. 36.

44. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p. 90.

45. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p. 129.

46. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207600 p. 10.

47. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207602 p. 45.

48. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207872 p. 42.

49. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651 p. 97.

50. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651 p. 99.

51. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208806 p. 33.

52. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Documents/RulesOfProcedure.pdf

53. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202655

54. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202655

55. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207602 p. 105.

56. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207919 p. 3.

57. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207919 p. 3–4.

58. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207919 p. 57.

59. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651 p. 105.

60. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208841 p. 66.

61. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Committees/BasicGov/Pages/CommitteeAgenda.aspx?tab=3&ItemID=2203355 p. 19.

62. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202655

63. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207600 p. 42.

64. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207600 p. 43.

65. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207602 p. 12.

66. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207872~p.5.

67. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202842

68. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202842

69. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202842

70. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208841 p. 93.

71. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2073485p. p. 20.

72. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2067907/2976233 p. 134.

73. ^https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-4960163,00.html

74. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2073133/3010704 p. 1288. https://www.inn.co.il/news/378297

75. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2208049/3807353 p. 309.

76. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2208651 p. 38.

77. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2201940/2200478 p. 118.

78. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2203525 p. 39.

79. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p.40.

80. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2208049/3807353 p. 300.

81. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2208049/3807353 p. 326.

82. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2208049/3807353 p. 342.

83. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2201940/2200478 p. 118.

84. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202655 p. 2.

85. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2202526/3327337 p. 110.

86. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2208049/3807353 p. 347.

87. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/apps/smartprotocol/session/2201940/2200478 p. 124.

https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202702 p. 8.

88. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2202842 p.5.

89. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p. 124.

90. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207577 p. 29.

91. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207602, for example, p. 98–99.

92. ^https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/committees/Pages/AllCommitteesAgenda.aspx?Tab=3&ItemID=2207872 p. 32.