- 1Department of Law, Universidade Portucalense Infante Dom Henrique, Porto, Portugal

- 2CEI-Iscte; GOVCOPP - University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Introduction: The financial architecture underpinning the BRICS has undergone significant evolution, reflecting broader changes in global economic governance. As a coalition of major emerging economies, the BRICS have sought to develop alternative financial mechanisms that enhance economic cooperation, reduce dependence on Western-dominated institutions, and promote a multipolar global financial order. This study explores the structural dynamics of these financial arrangements, analyzing their evolution, operational structures, and implications for global financial governance. A key component of this architecture is the New Development Bank (NDB), created to finance infrastructure and sustainable development projects within the BRICS countries and beyond. The NDB, together with other mechanisms such as the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), represents a strategic effort to provide alternative sources of financing while mitigating external financial vulnerabilities.

Methods: This research, based on the analysis of official policy documents, aims to answer the following research questions: To what extent does the financial architecture developed by the BRICS, particularly through the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, represent a counterinstitutionalization strategy in relation to global financial governance? Can the patterns of action and cooperation promoted by the BRICS through their financial mechanisms be interpreted as evidence of the Chinese revisionist vision embodied by the BRICS?

Results and discussion: Our first hypothesis is that it is possible to state that the BRICS constitute a challenge to international financial governance based on the counter-institutionalization strategy. In this way, the BRICS do not seek to replace the established global governance system, but rather to change it, generating adaptations. The second hypothesis, in turn, is that the BRICS appear to have incorporated the Chinese vision of global governance, by configuring themselves as a revisionist group and not a “full reformist” group, which means that the strategies of contesting the status quo seek to complement existing institutions and norms and not to replace them. By examining the evolution and structural dynamics of these financial arrangements, this study contributes to a broader understanding of the role of emerging economies in reshaping the global financial order.

Introduction

The BRICS1 have emerged as a significant bloc in the global economic landscape, challenging the traditional Western-dominated financial order. Central to this discussion is the extent of the BRICS’ structural power and their capacity to reshape international institutions (Duggan et al., 2022) – essentially, their ability to redefine the “rules of the game,” which encompass both formal and informal constraints on global interactions (North, 1990: 3). Since its formalization in the late 2000s, the group has sought to develop an alternative financial architecture to reduce dependence on existing institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. This effort has materialized through the establishment of financial mechanisms designed to enhance economic resilience, foster regional development, and promote monetary cooperation among member states.

Indeed, the formation of BRICS emerged in response to the shifting dynamics of global power, particularly the relative decline of Western dominance and the rise of emerging economies. Some authors like Nayyar (2016) highlight that the economic significance of BRICS lies in their combined demographic weight, natural resources, and rapidly growing economies. By the early 21st century, these nations collectively accounted for a substantial share of global GDP, trade, and foreign direct investment (FDI), positioning them as one of the key players in the global economy. This economic influence provided the foundation for the creation of financial mechanisms aimed at reducing dependency on traditional Western-dominated institutions like the IMF and the World Bank (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Duggan et al., 2022).

The theoretical underpinnings of BRICS’ financial architecture stem from the broader discourse on economic multipolarity and South–South cooperation. The group’s financial initiatives align with dependency theory and neo-structuralist economic thought, which advocate for greater autonomy of developing economies from Bretton Woods institutions (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Ferreira, 2022). Since the first formal BRICS summit in 2009, member states have taken concerted steps to institutionalize financial collaboration.

Although some authors have questioned the robustness and cohesion of the group as a united economic or political entity, considering its domestic and regional disparities (Kingah and Quiliconi, 2016), there is no doubt, as we will see in this work, that the BRICS have deepened and increased their institutionalization and role in global governance.

A pivotal moment in the evolution of BRICS’ financial architecture was the establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB), also referred to as the BRICS Development Bank (BDB), in 2014. The NDB was proposed to mobilize resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in emerging economies, addressing a critical shortfall in global infrastructure investment. With an initial subscribed capital of $50 billion, equally contributed by each BRICS member, the NDB reflects the bloc’s commitment to fostering South–South cooperation and reducing reliance on traditional multilateral development banks (Chin, 2014). The creation of the NDB was driven by the failure of existing institutions to meet infrastructure investment commitments. Since its inception, the NDB has evolved to expand its scope and membership. The NDB, for instance, has financed projects beyond BRICS countries, extending to other developing economies, thus reinforcing its role as a global lender (Arnold, 2024). The institution’s emphasis on local currency financing aims to reduce exposure to currency volatility and dependence on the U. S. dollar, a crucial aspect of BRICS’ de-dollarization strategy (Arnold, 2024).

The NDB emerged at a time when traditional banks that had financed development since the mid-20th century were losing legitimacy, due to practices involving excessive conditionalities for granting credit, power structures concentrated in developed countries, slow approval processes, and an inability to adapt to the economic protagonism of emerging countries (Molinari and Patrucchi, 2020).

The historical trajectory of BRICS financial institutions will be described in this paper, as well as the obstacles that need to be overcome. Indeed, despite the emergence of alternative funding mechanisms challenges the dominance of Western-led institutions and provides developing nations with additional financing options, structural challenges remain – including internal economic disparities among BRICS members, governance complexities, and geopolitical tensions – that could hinder deeper financial integration (Nach and Ncwadi, 2024).

This article examines the historical evolution of the BRICS financial architecture, tracing its foundational milestones, assessing its structural dynamics, and evaluating its implications for the global financial system. Based on the analysis of official policy documents, this research aims to answer the following research questions: To what extent does the financial architecture developed by the BRICS, particularly through the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, represent a counterinstitutionalization strategy in relation to global financial governance? Can the patterns of action and cooperation promoted by the BRICS through their financial mechanisms be interpreted as evidence of the Chinese revisionist vision embodied by the BRICS? Our first hypothesis is that it is possible to state that the BRICS constitute a challenge to international financial governance based on the counter-institutionalization strategy. In this way, the BRICS do not seek to replace the established global governance system, but rather to change it, generating adaptations. The second hypothesis, in turn, is that the BRICS appear to have incorporated the Chinese vision of global governance, by configuring themselves as a revisionist group and not a “full reformist” group, which means that the strategies of contesting the status quo seek to complement existing institutions and norms and not to replace them.

Methodological approach

This study adopts a qualitative and analytical research design, grounded in documentary analysis and an extensive review of the scholarly literature. The primary sources include official BRICS communiqués, summit declarations, and institutional reports, complemented by a systematic examination of recent academic debates on global governance and the international financial architecture.

The methodology is interpretative in nature, aiming not merely to describe institutional developments, but to critically assess the historical trajectory of the BRICS’ financial initiatives and their broader political significance. Particular attention is devoted to the establishment and evolution of the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), both considered emblematic of the bloc’s attempt to reshape existing financial governance structures.

By triangulating documentary evidence with theoretical insights from the literature, the study seeks to uncover patterns of continuity and change in the BRICS’ strategies, assessing whether they reflect reformist, revisionist, or counter-institutional tendencies. This approach enables a nuanced understanding of how the BRICS’ initiatives contribute to the reconfiguration of the global financial order, not as isolated innovations, but as part of a broader contestation of the status quo and its institutions.

Theoretical conceptual approaches, building a framework for analysis

There is no single theoretical-conceptual way of thinking about global governance. Historically, authors have defended different views on governance and its mechanisms of action (Rosenau and Czempiel, 1992; Pollack and Shaffer, 2010; Wessel, 2016). Understanding, first of all, the concept of governance and, equally, its foundations is essential for us to understand whether or not there are possible challenges and reorganizations in the governance currently in force.

For some scholars, international governance has as its central mechanisms international standards that function as standards. Therefore, different types of standards would require different institutional arrangements, which may be public, private, or mixed, depending on the nature of the problem being solved (Abbott and Sindal, 2001). In this sense, it is possible to affirm that the simple existence of standards, however technical or economic they may be, can configure the existence of governance. Furthermore, governance can occur at different levels and forms, depending on the interests at stake and the legitimacy of the institutions, and must reflect not only efficiency but also normative values (Abbott and Sindal, 2001).

Michael Zurn (2018) elaborates “a theory of global governance where the core of the argument is that world politics has developed a normative and institutional structure that contains hierarchies and power inequalities, and thus endogenously produces contestation, resistance, and distributional struggles” (p. 8). According to Zurn (2018), it is necessary to review the apparently unbreakable elective affinity between institutionalism and a cooperative reading of world politics. Furthermore, any theory of world politics needs to take into account that, in parallel with the decline of some mechanisms of global governance, there has been a greater deepening of others. This means that a theory of global governance applicable today must allow for the understanding of the complex parallelism of decline and deepening in global governance.

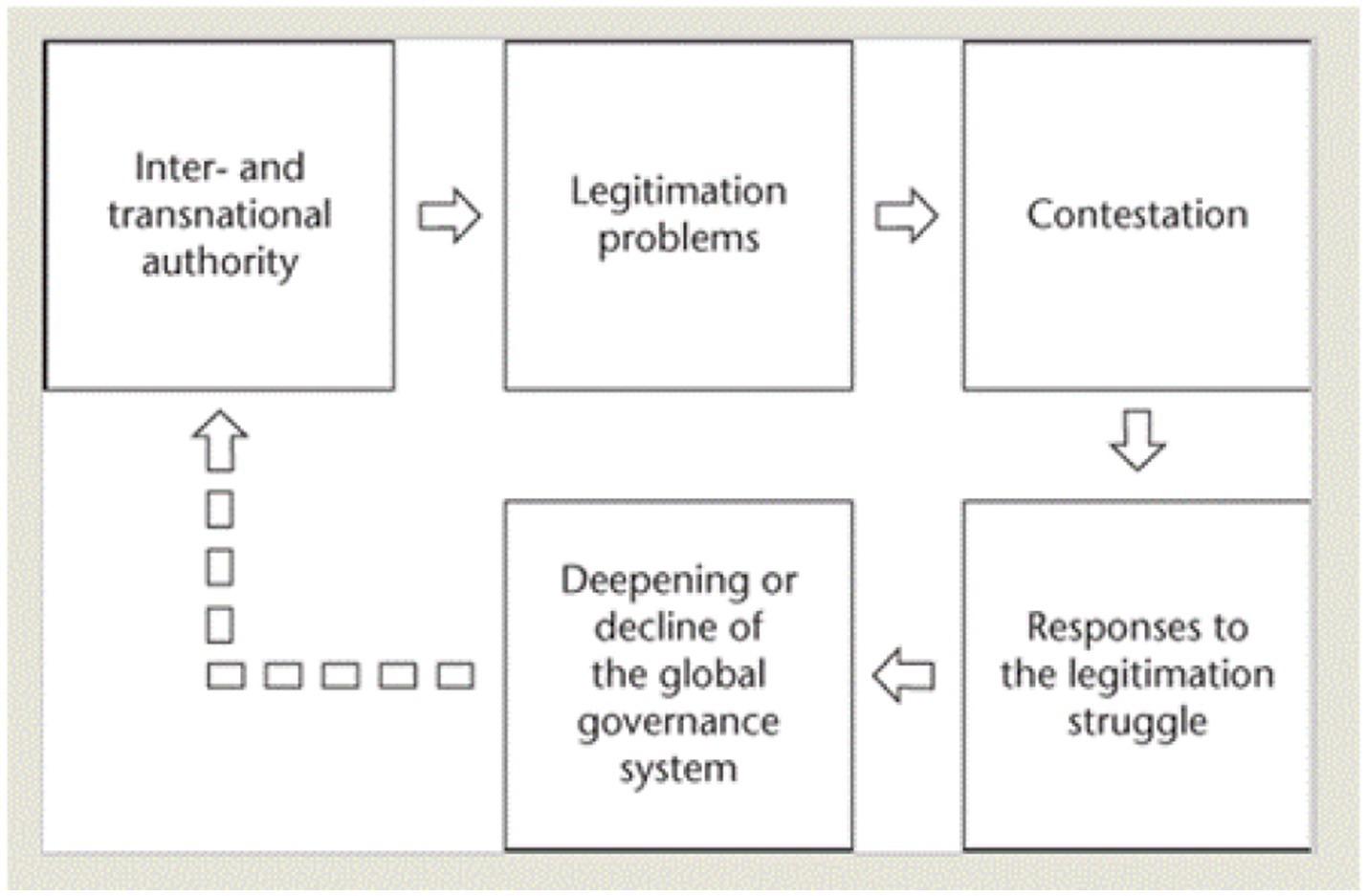

This dynamic between decline and deepening in global governance would derive from the idea that there is an “authority-legitimation link,” according to which international institutions with authority would require legitimation. When we have inter- and transnational institutions that exercise authority but are unable to draw on sufficient stocks of legitimacy, there tends to be growing resistance to these institutions. This “authority-legitimation link” is essential for understanding the challenge to the global governance system, as can be seen in Figure 1 (Zurn, 2018).

Figure 1. The causal model (Zurn, 2018).

This challenge can take many forms. In the case of state challenge, this occurs when certain states demand changes or the deconstruction of international authorities. Thus, we can say that while states recognize inter- or transnational authorities, they also challenge them. On the other hand, this response is not necessarily the withdrawal of existing institutions, but rather the creation of new institutions that better align with their current interests, with the aim of influencing or replacing old institutions, which can be called “counter-institutionalization” (Zurn, 2018).

Counter-institutionalization can lead to different results: fragmentation and, eventually, decline in global governance, or it can also create room for decisions that can, in some cases, deepen this governance, with new strategies to legitimize existing institutions. As Zurn (2018) states, state contestation is often generated by incompatibilities between the procedural rules of international institutions and the distribution of power among States, which means that an international institution that presents institutionalized inequality will tend to be contested by disadvantaged States whenever they experience an increase in relative power in the international system.

Counter-institutionalization has proven to be the preferred strategy of emerging powers and has led to the promotion of institutional adaptation. It is important to emphasize that, contrary to what some may think, counter-institutionalization does not seek to replace the established global governance system, but rather to change it (Zurn, 2018).

“Contestation by state actors takes place when states demand change in or the dismantling of international authorities. While states have, to a significant extent, driven the rise of international authority by delegating it to international institutions, they have done it in a reflexive manner. As a consequence, states simultaneously recognize and challenge inter- and transnational authorities. The established powers often contest the very same international institutions they have created the first time the institutions produce decisions they dislike. But their response is not—as conventional cooperation theory in the anarchy paradigm would have it—to deviate and exit. Rather, they set up new institutions closer to their current interests in order to influence or replace the old ones.” (Zurn, 2018, p. 11).

In reality, emerging states desire a greater voice in existing institutions, not a withdrawal from them. At the same time, these countries suspect that current international institutions act as instruments of Western domination, thus reinforcing the asymmetry of international power. Therefore, they create new institutions more aligned with their own interests. In short, counterinstitutionalization is a form of systemic change within the global governance system, utilizing international institutions against other international institutions, without resulting in a complete rejection of the system. As Zurn (2018) argues, counterinstitutionalization by emerging powers can lead to impasses and some fragmentation, but it can also promote institutional change within traditional institutions.

The literature on International Relations has also sought to understand how and why international institutions respond in different ways to unilateral challenges made by their member states, ranging from non-compliance with rules to attempts to renegotiate the rules of the game or even withdrawal (Walter and Plotcke-Scherly, 2025). From this perspective, international institutions face a strategic dilemma when responding to these unilateral challenges. The decision between accommodating or not accommodating the interests and/or proposals of the contesting state involves a difficult balance between two risks: (1) the risk of losing cooperation gains, with possible ruptures in international cooperation, if the institution chooses not to accommodate (e.g., Brexit); (2) risk of political contagion, with the encouragement of other States to postulate new challenges, if the institution chooses accommodation (Walter and Plotcke-Scherly, 2025).

When costs are considered significant, the institution faces an accommodation dilemma, which will be reflected in the types of institutional responses: (1) strong accommodation, when almost all of the challenger’s demands are met; (2) weak accommodation, when there are limited concessions; (3) neutral/passive response, when the result is accepted without relevant changes; (4) weak non-accommodation, when most of the demands are refused, but some flexibility remains; (5) strong non-accommodation, when there is a harsh response, without concessions and punishments are carried out (Walter and Plotcke-Scherly, 2025).

“Non-Western” theoretical-conceptual views have also gained ground in a field historically dominated by International Relations theories from the USA and Europe (Keohane, 2009). According to Pedro Steenhagen (2025), the challenge to international governance promoted by China has proven to be revisionist and not “full reformist,” which means that strategies to challenge the status quo seek to complement existing institutions and norms and not replace them. The Chinese approach can be argued to be “Janus-faced,” as it works within the existing framework to expand its influence while simultaneously creating parallel structures that can offer alternative or complementary pathways for global financial and economic governance (Méndez, 2024). Thus, China has moved away from the Bretton Woods development approach to favor its own “infrastructure first” paradigm and has supported reforms that shift the focus of MDBs toward infrastructure development, away from loans conditional on sociopolitical reforms or economic liberalization, which it believes burdens less developed countries2. This Chinese vision appears to be quite influential and decisive in the creation and operation of the New Development Bank, as we will see below.

Global governance and the global financial architecture

Global governance has been under pressure in many ways in the 21st century. Environmental, social and structural changes within global governance are necessary to deal with the imperative transition to a more sustainable future (Lopez-Claros et al., 2020). In the economic field, the growing risk of a global financial collapse also poses challenges to global governance, since there is currently no reliable and depoliticized mechanism for dealing with financial crises.

Since the Bretton Woods Agreement, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Regional Development Banks (RDBs) have been an attractive source of financing for developing countries, which has led to their proliferation in both number and size. They were designed to establish global economic rules for development, offering access to “soft” financing (on more favourable terms) through an organizational model based on cooperation. The original mandate of MDBs sought to strengthen the voice and participation of sovereign states to promote international financial stability and cooperation as global public goods, with a countercyclical function. However, the prioritization of market financing, driven by the preferences of non-borrowing countries that avoid large capitalization efforts, has significantly weakened the countercyclical development mandate of MDBs. This makes them more vulnerable to the preferences of a small group of countries (Molinari and Patrucchi, 2020).

In other words, the decision of the IMF whether or not to grant a loan is not the result of a transparent set of internationally agreed rules, but rather of the political will of the largest shareholders, namely the United States, which tends to support countries considered strategic allies (Lopez-Claros et al., 2020). In contrast to the one-country-one-vote system adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have adopted a weighted voting system. Even with the update of voting quotas, the recent galloping growth of economies such as China and India has created a gap between the relative weight occupied by these countries in the global economy and their voting quota within the decision-making processes at the IMF (Lopez-Claros et al., 2020). This new reality has created substantial political friction between emerging countries and traditional economies, especially after the 2008 crisis, when China increased its financial contributions to the International Monetary Fund without any political counterpart.

Eric Helleiner (2014) argues that, contrary to what many expected, the 2008 global financial crisis did not lead to a profound transformation in global financial governance. Despite the severity of the crisis, comparable to that of the 1930s, and the great expectations of change in the international financial system, what occurred in the following five years was a reaffirmation of the current order. The fact is that the reforms maintained the status quo rather than promoting significant changes.

Expectations of transformation focused on four major areas: (1) the creation of the G20 as a global leadership forum; (2) the possible erosion of the role of the dollar as an international reserve currency; (3) the review of financial regulatory standards, supposedly excessively pro-market before the crisis; (4) the establishment of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) as a new “fourth pillar” of global economic governance, alongside the IMF, World Bank and WTO (Helleiner, 2014).

Despite the supposed advances, these innovations gradually proved to be more symbolic than substantive. As far as the G20 is concerned, it did not prove to be very effective in managing the crisis. On the contrary, the most effective crisis management actions, such as the huge dollar liquidity swaps carried out by the US Federal Reserve (Fed), were taken unilaterally or bilaterally, without the direct involvement of the G20. The coordinated fiscal stimulus measures were also not the result of true international coordination, but rather domestic responses similar to a common shock (Helleiner, 2014).

At that time, too, contrary to expectations, the dollar’s hegemony was reinforced, since the dollar appreciated during the financial panic. Monetary diversification initiatives, such as the promotion of the Chinese renminbi or the expansion of the use of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), faced political resistance and were unsuccessful (Helleiner, 2014). To a large extent, the maintenance of the current order was due to the power and political choices of states, especially the United States. The structural capacity of the United States—its currency, its markets, its geopolitical role—gave it decisive influence, even without coordinated action (Helleiner, 2014).

Despite this outcome, the post-2008 financial crisis, with the decline in private credit and the retraction of European banks, intensified the need for new sources of financing (Chin, 2014; Molinari and Patrucchi, 2020). It is estimated that, at the time, developing countries needed between US$1 and 1.5 trillion annually in infrastructure investments, but only about US$800 billion had actually been invested, as the World Bank and regional banks had been significantly reducing infrastructure financing, prioritizing social sectors. The initiative to create the New Development Bank thus emerged amid dissatisfaction with international financial institutions (World Bank, IMF, regional banks), particularly regarding the underrepresentation of emerging countries and resistance to reforms, and the failure of the G20 powers to fulfill infrastructure financing commitments (Chin, 2014).

On the other hand, some authors, such as Petry and Nölke (2024), argue that the outbreak of the war in Ukraine has intensified changes in the global financial system. While the West has imposed sanctions on countries such as Russia and China, emerging markets have moved to evade these sanctions, leading to increased non-Western financial cooperation. For Petry and Nölke (2024), the BRICS have created alternative financial spaces that provide them with a greater degree of autonomy from the liberal global financial order led by the United States and that are part of a broader challenge promoted by the bloc.

Indeed, the global financial order as we know it from the 1980’s onwards is characterized by a few core elements: (a) liberal ideas that promote free cross-border capital flows and the prioritization of private profit, (b) institutions that favor light public regulation and strong international bodies to facilitate global financial integration, and (c) a power structure heavily influenced by the U. S. and the U. K., with significant roles played by Wall Street, the City of London, the U. S. dollar, and Anglo-American financial entities (Petry and Nölke, 2024). This arrangement fosters highly integrated and liquid financial structures, which are considered optimal for free markets and capital flows, and is maintained by a powerful core while limiting the control of individual states over financial activities. However, according to the same authors, this liberal global financial order is facing challenges, primarily from the increasing prominence of emerging market economies, especially the BRICS nations. These emerging economies are not only growing in economic power but also increasing their influence in global financial markets, which suggests a shift in the global financial architecture. This contestation is occurring across various levels, including domestic financial systems, transnational financial flows, and the push for reforms in international financial institutions (Petry and Nölke, 2024).

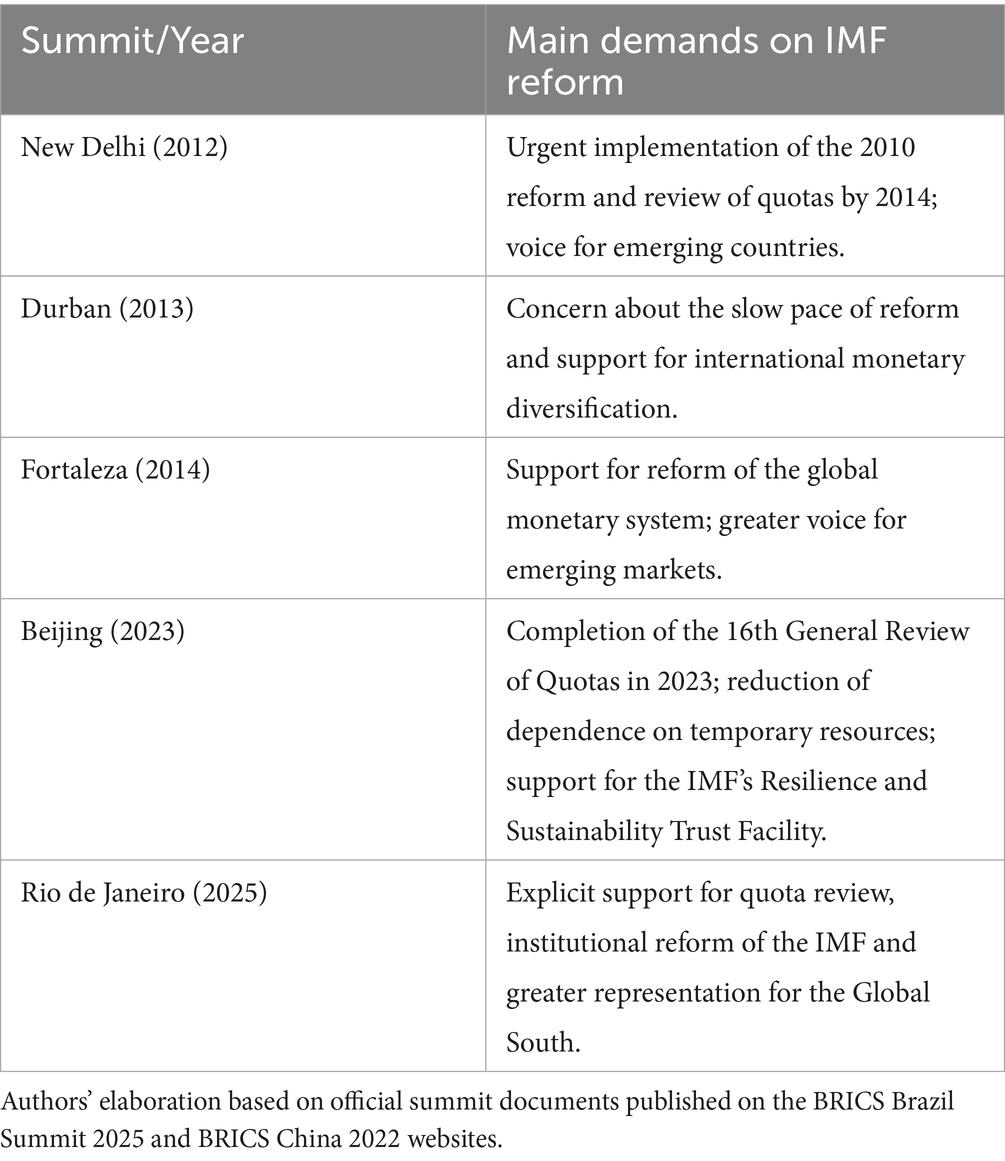

This increase in the relative power and influence of developing countries and emerging markets (DCEMs) has been reflected in new (and more assertive) recent joint positions adopted by the BRICS, such as those arising from the 17th BRICS summit, held in early July 2025 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. For the first time, BRICS finance ministers issued a unified position demanding reforms of the IMF’s quota system. We highlight here some points from the document “BRICS Leaders’ Declaration — Rio de Janeiro, July 6, 2025“: (1) Demand for an inclusive, merit-based selection process that would increase regional diversity and the representation of DCMs in the leadership of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group (WBG); (2) Request that the IMF Executive Board fulfill the mandate established by the Board of Governors to urgently develop approaches for realigning quotas, including through a new quota formula; (3) Affirmation that quota realignment in the IMF should not occur at the expense of developing countries, but should reflect the relative positions of countries in the global economy and increase the quotas of EMDPs (BRASIL, 2025; BRICS Summit, 2025).

It’s important to note that the demand for reforms to the International Monetary Fund has been discussed at other BRICS meetings. Table 1 shows the main milestones in the development of this topic within the BRICS over the past 15 years.

The New Development Bank and BRICS’ Impact on the Current International Financial Order: a New Paradigm of Complementarity and Innovation.

In response to a system historically dominated by Western powers, particularly concerning the Bretton Woods institutions, the BRICS nations have sought to construct institutional and political alternatives for a more multipolar, equitable, and representative global financial order that reflects the shifting distribution of global economic power (Ferragamo, 2024; EPRS, 2013). This initiative is not merely an opposition, but rather a force of complementarity and diversification to the existing model, contributing to more inclusive global governance (Steenhagen, 2025; Ferragamo, 2024; Nayyar, 2016).

A key instrument in this agenda is the New Development Bank (NDB), established in 2014 during the 6th BRICS Summit in Fortaleza, Brazil (Batista, 2016; Cooper, 2017). Headquartered in Shanghai, the NDB aims to finance infrastructure and sustainable development projects not only among its member states but also in developing countries more broadly (Latino, 2017). Its governance structure is founded on principles of equity, with each founding country possessing equal shareholding and voting rights, which significantly distinguishes it from the governance model of the IMF and the World Bank (Acioly da Silva, 2019), pointing towards a new governance model.

The governance structure of the NDB was designed with specific features to differentiate it from traditional international financial institutions (BRICS, 2018). Voting power is proportional to the subscribed capital shares, which means that all founding members initially have equal voting power (NDB, 2014). Decisions are generally made by a simple majority, with a “qualified majority” (two-thirds of total voting power) and a “special majority” (consent of four founding members) required for key issues, such as the admission of new members or capital increases. These regulations were designed to prevent any member from acting as a veto or blocking power (Freitas, 2025), promoting more balanced and collaborative governance.

The NDB is distinguished by its operational approach, characterized by more flexible criteria and greater sensitivity to the needs of countries in the Global South (Freitas, 2025; Acioly da Silva, 2019). It prioritizes projects with positive social and environmental impact while respecting national sovereignty. Since its inception, the bank has approved over US$50 billion in financing, spanning sectors such as renewable energy, transportation, water supply, and urban infrastructure (NDB, 2024a, 2024b). Furthermore, its recent expansion to include new members, such as Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2025), indicates the institution’s transformative potential as a global alternative and complementary financing platform.

The NDB primarily concentrates its operations on infrastructure and sustainable development projects (NDB, 2020). Its strategic focus encompasses sustainable infrastructure sectors such as renewable energy (solar and wind), energy efficiency, wastewater treatment, and sustainable water management (NDB, 2020). Environmental considerations are prominently embedded in its Constitutive Agreement, positioning the NDB as a “green bank” from its inception, approaching environmental factors as a central opportunity rather than a constraint. In practice, the bank’s initial portfolio has emphasized renewable energy initiatives (NDB, 2020).

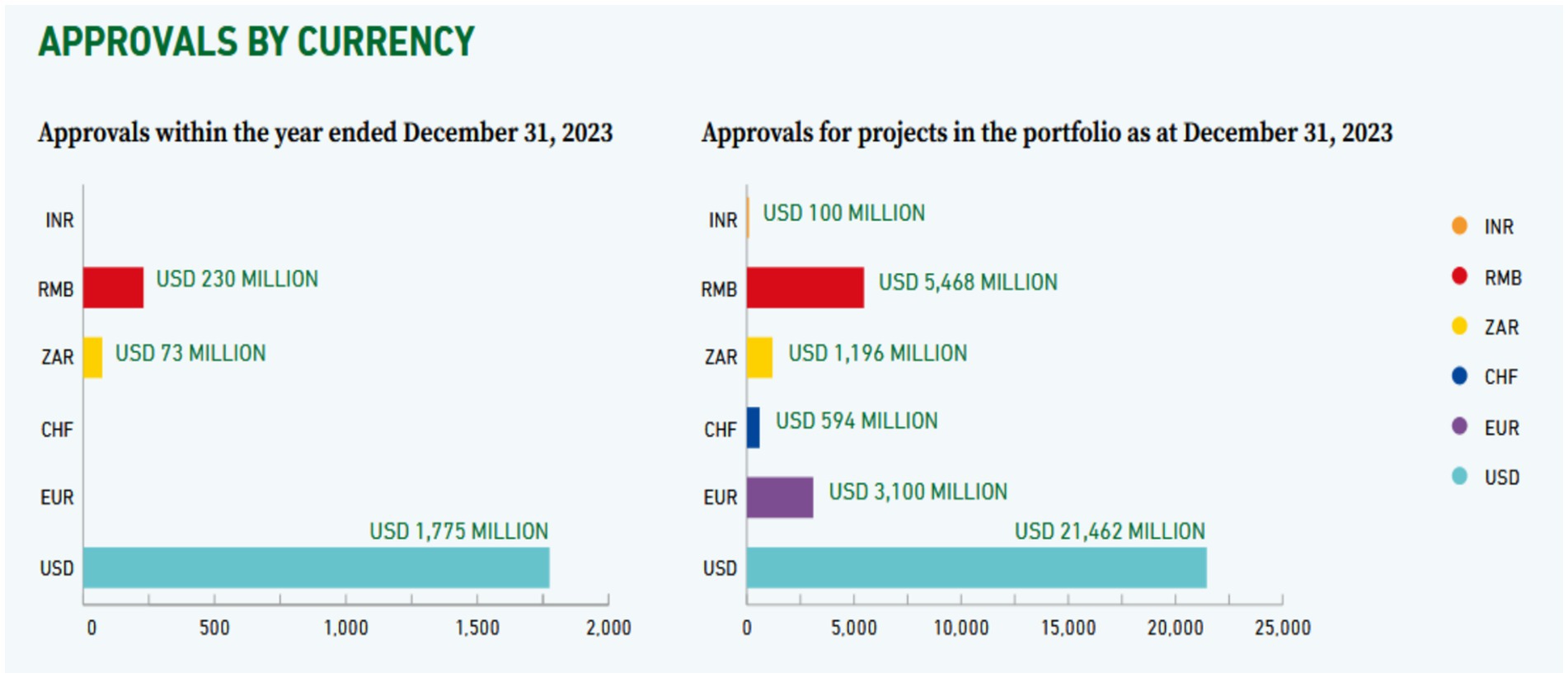

A distinctive feature of the NDB is its policy of financing projects in local currencies, aiming to mitigate exchange rate risks associated with U. S. dollar-denominated loans (Liu and Papa, 2022). This approach reinforces the use of BRICS national currencies (Brazilian real, Russian ruble, Indian rupee, Chinese renminbi, and South African rand) in international transactions, thereby supporting the diversification of foreign exchange reserves (Petry and Nölke, 2024). The first bond issued by the NDB was denominated in renminbi. The bank’s emphasis on local currency financing represents a deliberate and strategic move toward currency diversification and, potentially, the future adoption of a common currency within the bloc – directly linking development finance to the broader de-dollarisation agenda (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Liu and Papa, 2022), which demonstrates an innovative step in the global financial architecture.

In comparison to traditional multilateral development banks, NDB seeks to operate with greater agility, aiming for a project timeline of approximately six months from identification to approval – a pace that has been achieved in most of its initial projects (NDB, 2024; World Economic Forum, 2015). This stands in contrast to the “heavy structure” and “bureaucratized procedures” of the World Bank. Notably, the NDB was the first multilateral development bank to both approve projects and issue its inaugural bond within its first year of operation (NDB, 2024). The bank aims to maintain a focused mandate, concentrating specifically on infrastructure and sustainable development, in contrast to the broader scope of activities undertaken by the World Bank (Braga et al., 2022). The NDB’s emphasis on speed and targeted financing constitutes a constructive critique of the perceived inefficiencies and expansive mandates of traditional multilateral development banks. This operational distinction is intended to provide a more agile and responsive alternative for developing countries (Braga et al., 2022).

Beyond comparisons with the Bretton Woods institutions, the NDB also resembles and diverges from other Southern-led MDBs, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF). Like the NDB, the AIIB emphasizes infrastructure financing, streamlined approval processes, and respect for national sovereignty. However, the AIIB has expanded membership rapidly beyond Asia, integrating advanced economies and adopting governance features that partly align with traditional MDB standards, suggesting a hybrid model (Creutz, 2023; Wang, 2019). The CAF, meanwhile, has decades of experience in Latin America and is praised for regional embeddedness and pragmatic lending but operates with less emphasis on challenging global financial norms. Compared with these, the NDB stands out for its explicit counter-institutionalization strategy, its commitment to local currency financing, and its positioning as a political as well as financial instrument of South–South cooperation. Moreover, as Molinari and Patrucchi (2020) stress, the NDB’s more “rupturist” design contrasts with the AIIB’s hybrid nature, highlighting the diversity of Southern MDB strategies. This comparative lens underscores both the innovative promise and the enduring limits of the NDB as part of a wider ecosystem of Southern MDBs.

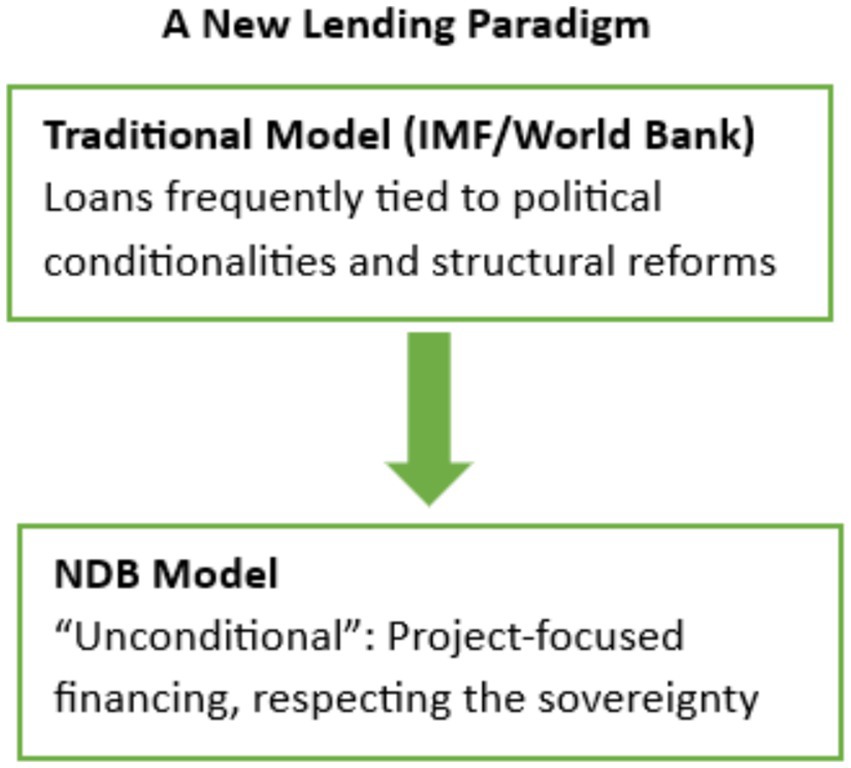

The NDB’s approach to conditionalities differs significantly from those practiced by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Cooper, 2017), as illustrated by Figure 2. The NDB explicitly states that it will not impose conditionalities nor tie project approvals and disbursements to changes in the policies or strategies of borrowing countries. This stance stands in sharp contrast to the practices of the World Bank and the IMF, both of which are known for imposing policy requirements that borrowing countries must fulfil to access loans, often influencing their economic and sectoral strategies. The BRICS countries reject such conditionalities as a form of paternalistic interference in the internal affairs of recipient states (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Garcia and Bond, 2021), representing a significant departure from liberal norms and an affirmation of national sovereignty.

Figure 2. A new lending paradigm: traditional model (IMF/World Bank) vs. NDB model (authors’ elaboration).

The NDB is committed to respecting national sovereignty and assessing projects within the framework of the borrowing countries’ domestic policies and legal systems. This is consistent with the BRICS’ broader emphasis on national sovereignty as an alternative to economic liberalism, particularly in opposition to what they perceive as intrusive financial practices (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Garcia and Bond, 2021). The NDB’s “no-strings-attached” lending policy – marked by the explicit rejection of political conditionalities – constitutes a cornerstone of its alternative “state-capitalist” model, directly appealing to developing countries dissatisfied with the interventionist governance of traditional international financial institutions (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Duggan et al., 2022). In doing so, the NDB positions itself as a defender of national policy space and autonomy.

Despite its innovative approach, the NDB faces several significant challenges in its aspiration to reshape the international financial system, stemming primarily from its governance structure, capital constraints, and the need to adhere to international banking standards (Duggan et al., 2022). Its initial capital and lending capacity are limited, representing a major obstacle to making a substantial contribution to the estimated US$1 trillion annual infrastructure financing demand (Petry and Nölke, 2024). The equal voting power and share subscription structure restrict the possibility of expanding the bank’s capital through the considerable national reserves of BRICS countries (particularly China) or through new member states (Hofman and Srinivas, 2024). Unless these constraints are lifted, the NDB will have to rely on refinancing via bond issuance in international capital markets. Access to low-cost capital depends on the NDB achieving a high credit rating. In turn, such a rating requires the bank to expand its loan portfolio while limiting exposure to least developed countries and high-risk lending (Sithole et al., 2023). If the NDB prioritizes rapid expansion of lending capacity at the expense of a strong credit rating, the concessional component of its loans would be reduced, thus weakening its financial attractiveness to least developed countries (Sithole et al., 2023; NDB, 2017). This inherent tension between the NDB’s aspiration to serve as an alternative source of finance for the Global South and the practical need to comply with the imperatives of global financial markets (e.g., credit ratings) creates a fundamental operational dilemma (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Duggan et al., 2022). However, it suggests that the NDB is navigating a complex path to fully realize its “alternative” paradigm while attracting capital from traditional financial markets, rather than necessarily compromising its foundational principles (Duggan et al., 2022; Sithole et al., 2023; Duggan et al., 2021).

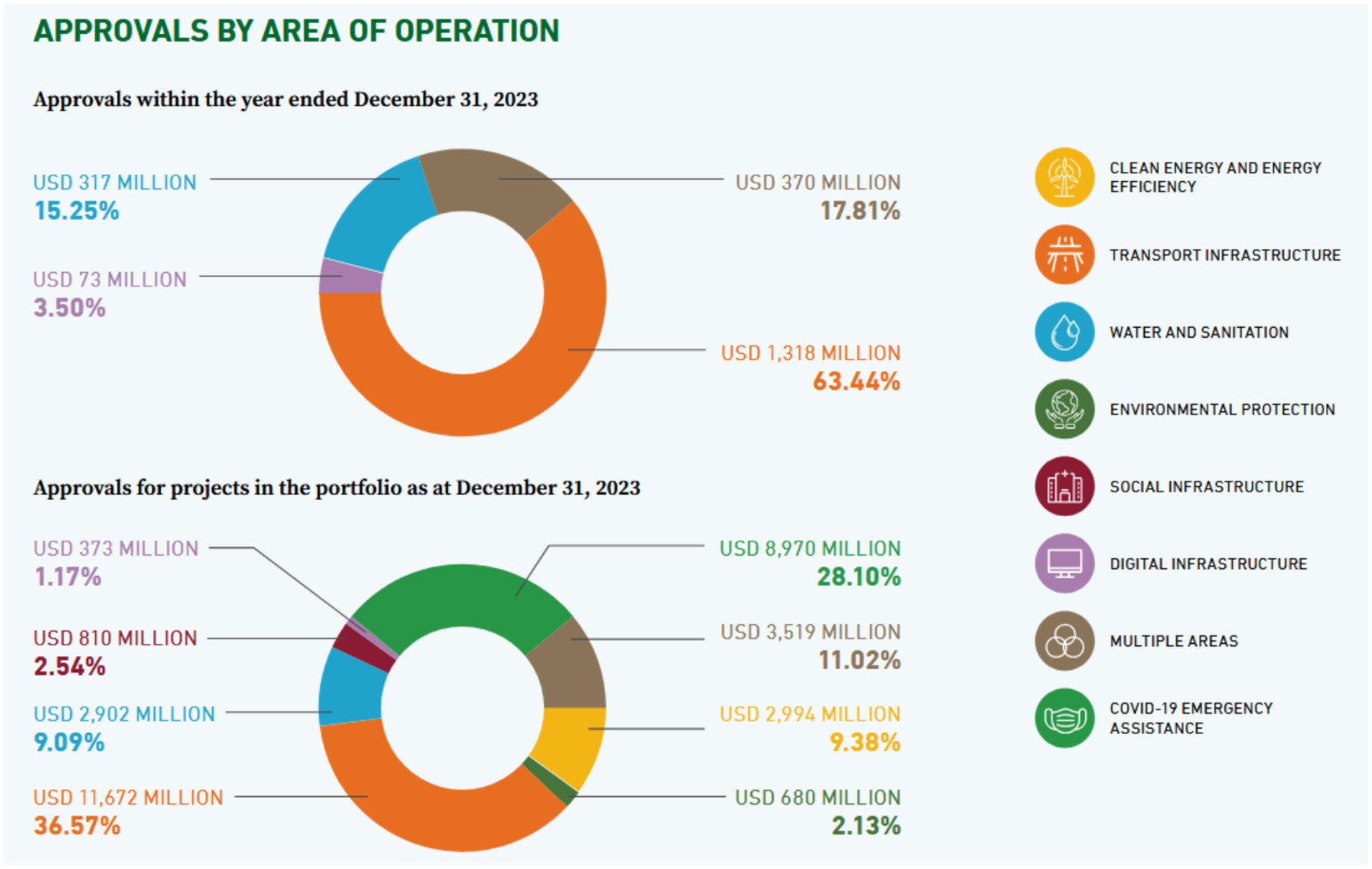

Despite the BRICS’ collective rejection of the “Washington Consensus” and neoliberal development paradigms, the NDB will likely be required to conform to international banking standards, especially in its early years (Petry and Nölke, 2024). This includes adherence to “prudential conditionality,” which ensures that loans are used for their intended purposes and are repayable (Petry and Nölke, 2024). Failure to meet these standards risks damaging the bank’s market rating, which is crucial for its capital-raising ability. As a result, borrowing countries may still face bureaucratic procedures comparable to those imposed by the World Bank system (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Duggan et al., 2021). Furthermore, although the NDB aims to provide loans free from political or “value-based” conditionalities, this approach may present a unique challenge in aligning with established development agendas (Duggan et al., 2021). Projects funded by BRICS countries have already been observed to present challenges similar to traditional donor shortcomings, particularly by emphasizing large greenfield investments that may suffer from maintenance issues and lack “pro-poor” impact (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Nayyar, 2016), as it can be confirmed by data on Figure 3. Macroeconomic risks also persist, such as capital flow transaction costs, disadvantages for local firms due to “aid with strings attached,” and the potential for debt distress in recipient countries (Petry and Nölke, 2024). If the NDB neglects institutional development, the long-term sustainability of its infrastructure engagement could be jeopardized. The NDB’s rejection of “value-based” conditionalities – while aligning with the sovereignty preferences of borrower countries – entails the need for robust internal mechanisms to ensure strong development outcomes (Duggan et al., 2021). This highlights a critical balance between respecting national sovereignty and ensuring robust development outcomes.

Figure 3. NDB approvals by area of cooperation for the year 2023 (Source: 2023 NDB Annual Report, 2024).

All in all, important gaps persist between the NDB’s rhetoric and its actual practices. While the institution promotes itself as a flexible, sovereignty-respecting, and pro-South lender, its operations sometimes mirror the very procedures it sought to escape, as per Figures 3, 4, gathered from the NDB Annual Report of 2023, where we can observe that the transport infrastructure still occupies the first place in terms of types of investments (at the expense of social infrastructures or water and sanitation, for example) and the main currency used for the loans is still the American dollar (NDB, 2024a, 2024b).

As Molinari and Patrucchi (2020) observe, these tensions reflect a broader dilemma of new MDBs: balancing legitimacy through representation with dependence on global financial resources. This rhetoric–practice gap reveals the tensions inherent in simultaneously seeking legitimacy in global financial markets and constructing a counter-hegemonic development model.

Monetary and financial subsystem: changing the scenario for diversification

The BRICS are actively engaged in reducing their dependence on the US dollar, a process known as de-dollarisation. This initiative aims to mitigate vulnerability to dollar-induced economic shocks, changes in US monetary policy, and challenge the unipolar concentration of economic power (Arnold, 2024; Liu and Papa, 2022). This move should be seen as a diversification strategy rather than a direct confrontational challenge to the existing system.

The proposal to create a common currency among the BRICS countries has been considered a response to the dollar’s hegemony in the international financial system. Among the currency models under discussion are the creation of a unit of account, similar to the old European ECU, the creation of a digital currency (CBDC) leveraging blockchain and interconnected platforms, and a commodity-backed currency, advocated especially by Russia and China. Each model presents technical challenges (system interoperability), legal challenges (compatibility with WTO/IMF rules), and political challenges (defining governance and power distribution) (Moch, 2025).

The creation of a single currency would have the impact of reducing demand for the dollar, increasing US financing costs, and potentially weakening Western financial centers. Furthermore, it would grant the BRICS countries greater autonomy in trade and investment. However, it would encounter fundamental problems, such as economic diversity within the BRICS. BRICS countries have very different inflation rates, fiscal policies, and exchange-rate regimes and managing a shared unit of account requires some harmonization, which is politically sensitive. Unlike the Eurozone, the BRICS have no common central bank, no fiscal union, and limited financial integration. Finally, for a unit of account to work, it needs international recognition. Without broad trust from global markets, it could be underused. And both the US and Europe are expected to offer geopolitical resistance to this new currency. In this way, the common unit risks being “symbolic” without infrastructure (Moch, 2025).

One of the BRICS’ main strategies has been to enter into currency swap agreements to facilitate trade and investment between member countries using their local currencies, avoiding the need for dollar-denominated transactions (Arnold, 2024; Petry and Nölke, 2024). There is a growing trend among the BRICS countries to use local currencies for trade settlements. Trade between China and Russia reached US$147 billion in 2021, with yuan-ruble trade accounting for 25% of transactions (Arnold, 2024). In the second quarter of 2023, the renminbi (RMB) accounted for 49% of China’s bilateral trade, surpassing the dollar for the first time (Petry and Nölke). Russia’s de-dollarisation efforts have significantly reduced the dollar’s share of its trade and financial flows since 2013 (Arnold, 2024; Petry and Nölke, 2024). India and Brazil are also exploring opportunities to settle trade in their respective currencies (Arnold, 2024; Petry and Nölke, 2024). These developments illustrate a gradual, yet significant, shift towards a more diversified and multipolar monetary system.

Despite such developments, as already highlighted before in this paper and illustrated in Figure 4, there is still a high dependency on the American dollar, turning the de-dollarisation a slow- path procedure. Another significant limitation in the growing use of local currencies in international trade is the persistence of imbalances and technical barriers that emerge when partners have asymmetrical needs and different levels of internationalization of their currencies. The example of Russian-Indian trade is illustrative: despite attempts to settle transactions in rupees and rubles after Western sanctions, a lack of convertibility and the accumulation of trade surpluses on the Russian side created practical obstacles, leading Moscow to increasingly request settlement in Chinese renminbi (RMB) (Greene, 2023). This situation highlights the structural vulnerabilities of relying exclusively on local currencies in bilateral arrangements, since one partner may find itself with large reserves of an illiquid currency that cannot be easily used for imports or reinvestment.

These shortcomings have broader implications for initiatives that promote South–South cooperation and alternatives to dollar-based settlements. While currency diversification can reduce exposure to the US dollar, it also introduces challenges of exchange rate volatility, limited liquidity, and the absence of deep financial markets to support widespread adoption (Taylor, 2025). As the Indian case demonstrates, even major emerging economies may face constraints when their currencies are not fully convertible, which ultimately reinforces the attractiveness of the RMB as a regional or global settlement currency. Nevertheless, this dynamic also creates new asymmetries, since RMB use strengthens China’s relative position while limiting the autonomy of smaller partners.

Regarding central banks and monetary policy, a notable degree of state influence is observable in BRICS central banks, presenting an alternative to the traditional liberal ideal of fully independent central banks. BRICS central banks often exhibit significant state influence and broader mandates that extend beyond mere inflation targeting (Clarida, 2022). For instance, China’s central bank is closely integrated with the government, with mandates encompassing economic growth, employment, and financial stability. India’s central bank also operates with a degree of government oversight and a multifaceted mandate. While formally independent, Russia’s central bank has shown increasing policy alignment, particularly after 2022. Brazil’s central bank recently gained independence, though its autonomy remains a subject of ongoing dialogue with the current government (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Garriga and Rodriguez, 2023). South Africa’s central bank, while independent, maintains a broader inflation target and actively manages foreign exchange reserves. This diverse but generally more integrated approach to central banking within BRICS highlights a preference for national policy space and strategic alignment, which can be seen as a complementary model of monetary governance aimed at comprehensive economic stability and growth (Freitas, 2025).

The development of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) represents another significant area of focus and innovation for the BRICS nations. They are increasingly committed to advancing CBDCs as a strategic means to enhance financial resilience, diversify away from Western-controlled global payment infrastructures (such as SWIFT), mitigate reliance on the US dollar, and facilitate stronger state oversight and capital controls (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Kuehnlenz et al., 2023). India, Russia, and China have already launched CBDC pilot projects, while Brazil is actively working on Proofs of Concept. China is notably proactive in facilitating the cross-border use of non-Western CBDCs (e.g., the mBridge project). The BRICS’ momentum in CBDCs is a direct technological and strategic response to the perceived vulnerabilities and concentrated power of the Western-dominated global payment system (SWIFT) and dollar hegemony (Freitas, 2025; Petry and Nölke, 2024). In both the 2024 summit in Russia and the 2025 summit in Brazil, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov highlighted the prospect of creating a transaction hub within the NDB that could serve as a platform for cross-border payments. Framed as a de facto alternative to SWIFT, this proposal seeks to institutionalize a payment infrastructure that reduces the bloc’s exposure to Western sanctions and strengthens financial autonomy among its members (NDB, 2025; Moch, 2025).

The international mobility of capital is an area where BRICS’ approach offers a distinctive perspective. While the liberal global financial order has traditionally advocated for the complete abolition of capital controls, BRICS countries maintain varying degrees of restrictions, reflecting a pragmatic emphasis on national stability and policy autonomy. South Africa, India, and China largely maintain closed capital accounts, while Brazil and Russia, after periods of liberalization, have reverted to more managed regimes. Russia, in particular, re-implemented stringent exchange controls following recent geopolitical events. BRICS nations also partially resist pressures from Anglo-American index providers (such as MSCI) that significantly influence financial flows (Petry and Nölke, 2024). India, for example, has strategically resisted MSCI pressure to maintain control over its domestic capital markets. China strictly regulates foreign investors, utilizing a controlled opening to promote the internationalization of the RMB. It is notable that the IMF has substantially revised its strong stance on capital controls since 2012, partly due to the collective resistance and vocal critiques from BRICS countries (Petry and Nölke, 2024). BRICS have leveraged their growing influence within the IMF (e.g., through appointments and a unified voice) to shape this policy shift (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2025). The varied yet persistent use of capital controls by BRICS and their collective influence on the IMF’s stance on capital mobility represent a significant evolution in the understanding of capital flows, prioritizing national policy space and stability over full financial integration, rather than outright rejection of global financial norms (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2025; Petry and Nölke, 2024).

Regarding Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), India, China, and Russia maintain some of the most regulated FDI regimes globally. They selectively open their economies to foreign investment to protect strategic sectors, limit foreign ownership, and facilitate technology transfer, demonstrating a strategic and managed approach to integration. Brazil and South Africa, conversely, have more liberalized regimes. Unlike Western FDI, state-led outbound FDI from BRICS (mainly China and Russia) is often guided by strategic and political objectives, aiming for control of target companies and alignment with national development strategies. This offers a distinct model of international investment compared to Western portfolio investment, which primarily seeks profit maximization. The BRICS’ nuanced approach to the liberal FDI regime is substantial, manifesting in domestic FDI restrictions, the strategic nature of state-led outbound FDI, and a critical stance towards investment arbitration panels often perceived as favouring Western investors. This represents a recalibration of global FDI norms, emphasizing national development priorities (Petry and Nölke, 2024).

Concerning ownership and corporate governance, BRICS countries present an alternative to the liberal financial order by maintaining a significant degree of state ownership in listed companies and by shaping the influence and ownership of foreign institutional investors. State influence also extends through opaque investment structures and socio-economic ties between political and business elites. The transnationalization of BRICS state capital, primarily from China and Russia, focuses on majority stakes, indicating a long-term strategy for control of target enterprises, rather than short-term portfolio investments (Babic et al., 2020). While international regulation of Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) exists (Santiago Principles), its effectiveness is limited, allowing BRICS SWFs to operate with a degree of opaqueness, which challenges certain aspects of the liberal global financial order by promoting alternative governance models (Chijioke-Oforji, 2019).

In the realm of commercial banks and banking regulations, BRICS countries constructively engage with and at times diverge from the liberal order through strong state involvement in domestic banking systems, distinct transnational lending patterns, and efforts to reform international banking regulations (Petry and Nölke, 2024; Papa et al., 2023). Foreign bank participation in BRICS is significantly lower than in Western economies, underscoring a desire to maintain national control over credit allocation. BRICS banks, particularly Chinese ones, have emerged as major global lenders, focusing on lending to developing countries. This fills a gap left by Western banks and offers an alternative that shields borrowers from the volatility and pressures of global financial markets, creating a more diversified lending landscape (Schapiro, 2024). While BRICS formally support the Basel Accords, their implementation is often selective and aligned with domestic priorities. There is also strong BRICS opposition to the dominant role of Western credit rating agencies and a proposal to create a BRICS credit rating agency, signalling a desire for greater autonomy and alternative assessment frameworks (Schapiro, 2024).

Regarding financial markets and their regulation, BRICS countries are shaping the global landscape through their governance and ownership of these markets, as well as their approach to controlling trading activities. Stock exchanges in China are fully state-owned, while in Russia and India, state-owned institutions are the largest shareholders. Foreign ownership in exchanges is restricted within BRICS, and competition from other trading platforms is limited or prohibited, concentrating trading activity on centralized exchanges. In the derivatives market, BRICS favour regulated exchange-traded markets over over-the-counter (OTC) markets, with India, Brazil, and China among the largest exchange-traded derivatives markets globally (Petry and Nölke, 2024). Profit-driven market practices, such as High-Frequency Trading (HFT), are restricted or heavily regulated in China and India to prioritize strategic, long-term considerations over speculative activity. At the international level, BRICS have gained influence in financial market governance bodies such as the FSB and IOSCO, as well as in industry associations, which allows them to proactively influence discussions and regulations (Petry and Nölke, 2024). This collective engagement contributes to a more multifaceted and inclusive global financial governance structure, where diverse national approaches are increasingly acknowledged.

Final considerations

The analysis developed throughout this study highlights the attempt of a renewed financial architecture, centred on the BRICS bloc, as a fundamental catalyst for the reconfiguration of the global financial order. The formation and evolution of mechanisms, such as the New Development Bank (NDB), are not mere additions to the international financial landscape; in fact, they represent a tangible manifestation of a concerted effort to mitigate dependence on hegemonic institutions and to infuse principles of multipolarity and equity into global economic governance.

The NDB, in particular, is distinguished by its innovative governance structure, characterised by equal voting among its founding members, a fundamental departure from the asymmetrical power arrangements prevalent in the Bretton Woods institutions. This parity is not just symbolic; it translates into operational flexibility and greater sensitivity to the development priorities of the economies of the Global South, which is manifested in the absence of political conditionalities and the exploitation of financing in local currencies. The latter strategy, in particular, not only addresses the exchange rate risks inherent in loans denominated in traditional reserve currencies, but also pushes forward the de-dollarisation agenda, redefining the dynamics of monetary power in the global system. By positioning itself as having a ‘new lending paradigm’, the NDB offers an alternative that intrinsically respects national sovereignty and the contextual specificities of borrowing countries.

However, despite its transformative impetus and distinctive strengths, the capacity of the BRICS financial architecture to reshape the global financial order is not without its constraints. The size of its financial capacity, although growing, remains below that of traditional institutions, limiting its scale of intervention. In addition, the intrinsic complexities of coordinating policies between nations with divergent national interests and economic models, as well as the geopolitical tensions inherent in a rapidly changing global scenario, are persistent challenges that could dampen its potential for consolidation and expansion.

A pragmatic example of such challenges is the operationalization of the NDB hub for payments that would mark a significant evolution of the NDB’s role, extending beyond development finance into the realm of financial intermediation and payment systems. If successful, this initiative could consolidate ongoing de-dollarisation efforts and accelerate the diversification of global payment channels. At the same time, it raises critical questions regarding governance, interoperability with existing systems, and the capacity of BRICS to build the necessary technological and regulatory frameworks. From an analytical standpoint, the proposal reflects the broader counter-institutionalization strategy pursued by BRICS: not the outright replacement of global infrastructures, but the creation of parallel mechanisms capable of reshaping incentives and gradually eroding the centrality of Western-led systems.

The challenge to the US-led liberal order that BRICS embodies is not necessarily a total rejection of the status quo, but rather a reformist movement. It seeks an institutional adaptation that reflects the emergence of new powers, advocating more inclusive and representative global governance, without necessarily dismantling the pillars of the existing system. In this sense, the creation of alternative financial spaces by the BRICS, rather than a mere duplication of functions, acts as a crucial mechanism for the strategic autonomy of its members and for promoting a more widespread balance of power, with new and different paradigms of governance.

To summarize, this study shows that the evolution of the BRICS financial architecture, with the NDB as its main vector, is progressively redefining the contours of global financial governance. By offering a distinct development and financing model that favours equity, sovereignty and monetary diversification, BRICS not only mitigates systemic financial vulnerabilities for its members, but also paves the way for a multipolar order. Its continued success and ability to deepen its influence will depend on overcoming internal structural challenges and its ability to navigate a complex geopolitical environment, consolidating its position as an indispensable actor in the quest for a more robust, equitable and representative international financial system.

Looking ahead, several scenarios may shape the trajectory of the NDB and the BRICS financial architecture more broadly. In an optimistic scenario, the bank’s expansion of membership and capital base enables it to consolidate as a leading Southern-led MDB, strengthening multipolarity in global finance. A more pessimistic scenario envisions stagnation, where capital limitations, governance frictions, and geopolitical tensions prevent the NDB from scaling up its role beyond a symbolic alternative. A third, hybrid path would see the NDB converge toward partial alignment with existing MDB practices, balancing its sovereignty-based discourse with pragmatic adaptation to global financial standards. Each of these futures carries strategic implications for global governance: the first would accelerate institutional pluralism and the erosion of Western dominance, the second would preserve the status quo, and the third would reinforce a hybrid order of cooperation and contestation.

Ultimately, the NDB and the BRICS financial mechanisms are at a crossroads. Their ability to generate systemic transformation will depend not only on internal reforms and capital accumulation but also on their strategic positioning within the contested field of global governance. The choices made in the coming years will determine whether BRICS financial architecture becomes a cornerstone of a multipolar order or remains a complementary, yet constrained, addition to the established system.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. AS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the UIDB/04112/2020 Program Contract, funded by national funds through the FCT, I.P.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. For the suggestion of the relevant topics to be addressed within the main theme.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The idea of creating BRICS as a political arrangement emerged in 2006, during the first official meeting between the Foreign Ministers of the four countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China), during the UN General Assembly. The first summit of heads of state was decreed in 2009, in Russia. South Africa was officially invited to join the group in 2010. Since 2024, the group has been expanding and reconfiguring itself as BRICS+, with Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates having already been incorporated (BRICS, 2025a, 2025b).

2. ^China also led the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which began its activities in 2016 (Méndez, 2024).

References

Abbott, K. W., and Sindal, D. (2001). International 'standards' and international governance. J. Eur. Public Policy 8, 345–370. doi: 10.1080/13501760110056013

Acioly da Silva, L. (2019). BRICS joint financial architecture: The new development Bank, discussion paper, no. 243. Brasília: Institute for Applied Economic Research.

Arnold, T. D. (2024). De-dollarization and global sovereignty: BRICS’ quest for a new financial paradigm. Hum. Geogr. 18, 78–83. doi: 10.1177/19427786241266896

Babic, M., Garcia-Bernardo, J., and Heemskerk, E. M. (2020). The rise of transnational state capital: state-led foreign investment in the 21st century. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 27, 433–475. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1665084

Batista, P. N. (2016). Brics - Novo Banco de Desenvolvimento. Estud. Av. 30, 179–184. doi: 10.1590/s0103-40142016.30880013

Braga, J. P., De Conti, B., and Magacho, G. (2022). The New Development Bank (ndb) as a mission-oriented institution for just ecological transitions: a case study approach to BRICS sustainable infrastructure investment. Revista Tempo do Mundo. (29) pp. 139–164. doi: 10.38116/rtm29art5

BRASIL (2025). BRICS Leaders' Declaration 2025. Available online at: https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/canais_atendimento/imprensa/notas-a-imprensa/declaracao-de-lideres-do-brics-2014-rio-de-janeiro-06-de-julho-de-2025?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed January 6, 2025).

BRICS (2025a). BRICS Previous Summits. Available online at: https://brics.br/en/about-the-brics/brics-previous-summits?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed September 4, 2025).

BRICS (2025b). IV BRICS Summit Delhi Declaration. Available online at: https://brics2022.mfa.gov.cn/eng/hywj/ODS/202207/t20220705_10715631.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed September 4, 2025).

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2025). BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and Aspirants. Washington, D.C: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Chijioke-Oforji, C. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of sovereign wealth fund governance and regulation through the Santiago principles and the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds. Unpublished Doctoral thesis.

Chin, G. T. (2014). The BRICS-led development bank: purpose and politics beyond the G20. Glob. Policy 5, 366–373. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12167

Clarida, R. H. (2022). Perspectives on global monetary policy coordination, cooperation, and correlation. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve. doi: 10.1016/j.jimonfin.2022.102749

Cooper, A. F. (2017). The BRICS’ new development bank: shifting from material leverage to innovative capacity. Glob. Policy 8, 275–284. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12458

Creutz, K. (2023). Multilateral development banks as agents of connectivity: the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Asian infrastructure investment Bank (AIIB). East Asia 22, 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s12140-023-09408-6

Duggan, N., Bas, H., Marek, R., and Ekaterina, A. (2021). Unfinished business: the BRICS, global governance, and challenges for south-south cooperation in a post Western world. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 43:211. doi: 10.1177/01925121211052211

Duggan, N., Ladines Azalia, J. C., and Rewizorski, M. (2022). The structural power of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) in multilateral development finance: a case study of the new development Bank. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 43, 495–511. doi: 10.1177/01925121211048297

EPRS (2013). The BRICS Bank and Reserve Arrangement: towards a new global financial framework? Ixelles: European Parliament.

Ferragamo, M. (2024). What is the BRICS group and why is it expanding? Washington, D.C: Council on Foreign Relations.

Ferreira, F. H. G. (2022). The analysis of inequality in the Bretton woods institutions. Glob. Perspect. 3:981. doi: 10.1525/gp.2022.39981

Freitas, M. (2025). BRICS: A New Framework for New South Inclusiveness. Rabat: Policy Center for the New South.

Garcia, A., and Bond, P. (2021). BRICS from above, coming from below. The Routledge handbook of transformative global studies. London: Routledge, 165–180.

Garriga, A. C., and Rodriguez, C. M. (2023). Central bank independence and inflation volatility in developing countries. Econ. Anal. Policy 78, 1320–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2023.05.008

Greene, R. (2023). The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts and the Renminbi’s Role. New York, NY: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Helleiner, E. (2014). The status quo Crisis_ global financial governance after the 2008. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hofman, B., and Srinivas, P. S. (2024). New development bank’s role in the global financial architecture. Glob. Policy 15, 451–457. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.13389

Keohane, R. (2009). The old IPE and the new. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 16, 34–46. doi: 10.1080/09692290802524059

Kingah, S., and Quiliconi, C. (Eds.) (2016). Global and regional leadership of BRICS countries. New York, NY: Springer, 1–12.

Kuehnlenz, S., Orsi, B., and Kaltenbrunner, A. (2023). Central bank digital currencies and the international payment system: the demise of the US dollar? Res. Int. Bus. Finance 64:101834:101834. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101834

Latino, A. (2017). “The new development bank: another BRICS in the wall?” in Accountability, transparency and democracy in the functioning of Bretton woods institutions. ed. E. Sciso (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 47–69.

Liu, Z., and Papa, M. (2022). Can BRICS De-dollarize the global financial system? Elements in the Economics of Emerging Markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lopez-Claros, A., Dahl, A. L., and Groff, M. (2020). Global governance and the emergence of global institutions for the 21st century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Méndez, Á. (2024). Reforming multilateral financial institutions: perspectives from India and China on development finance in the Global South, 57–73.

Moch, E. (2025). The introduction of a BRICS currency and its impact on the international financial architecture. Int. J. Financ. Account. 4, 103–119. doi: 10.37284/ijfa.4.1.3053

Molinari, A., and Patrucchi, L. (2020). Multilateral development banks: counter-cyclical mandate and financial constraints. Contexto Int. 42, 597–619. doi: 10.1590/s0102-8529.2019420300004

Nach, M., and Ncwadi, R. (2024). BRICS economic integration: prospects and challenges. S. Afr. J. Int. Aff. 31, 151–166. doi: 10.1080/10220461.2024.2380676

Nayyar, D. (2016). BRICS, developing countries and global governance. Third World Q. 37, 575–591. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1116365

NDB (2020). New Development Bank Sustainable Financing Policy Framework governing the issuances of green/social/sustainability debt instruments. Shanghai: New Development Bank.

NDB (2024b). Annual Report 2023: Financing for Sustainable Development. Shanghai: New Development Bank.

NDB. (2025). Address by H.E. Mr. Anton Siluanov, governor for Russia, minister of finance of the Russian Federation. Available online at: https://www.ndb.int/news/address-by-h-e-mr-anton-siluanov-governor-for-russia-minister-of-finance-of-the-russian-federation/ (Accessed July 4, 2024).

North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Papa, M., Han, Z., and O’Donnell, F. (2023). The dynamics of informal institutions and counter-hegemony: introducing a BRICS convergence index. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 29, 960–989. doi: 10.1177/13540661231183352

Petry, J., and Nölke, A. (2024). BRICS and the global financial order: Liberalism contested? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pollack, M. A., and Shaffer, G. (2010). “Introduction: Transatlantic governance in historical and theoretical perspective” in Transatlantic governance in the global economy. eds. M. A. Pollack and G. C. Shaffer (Minnesota, MN: Rowman & Littlefield), 10–25.

Rosenau, J. N., and Czempiel, E.-O. (1992). Governance without government: Order and change in world politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schapiro, M. G. (2024). Prudential developmentalism: explaining the combination of the developmental state and Basel rules in Brazilian banking regulation. Regul. Gov. 18, 439–459. doi: 10.1111/rego.12389

Sithole, M., Sweetness,, and Hlongwane, N. (2023). The role of the New Development Bank on Economic growth and Development in the BRICS states. MPRA Paper 119958. Munich: University Library of Munich.

Steenhagen, P. (2025). The role of China in a world under transformation: A non-Western approach to global governance. Global and Regional Governance in a Multi-Centric World. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, M. (2025). Challenging dollar dominance? The geopolitical dimensions of renminbi (RMB) internationalisation. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 258. doi: 10.1177/18681026251342258

Walter, S., and Plotcke-Scherly, N. (2025). Responding to unilateral challenges to international institutions. Int. Stud. Q. 69:sqaf022. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqaf022

Wang, H. (2019). The New Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: China’s Ambiguous Approach to Global Financial Governance. Dev. Change. 50, 221–244. doi: 10.1111/dech.12473

Wessel, R. A. (2016). The European Union in international organisations and global governance: recent developments. Yearb. Eur. Law. 35, 727–731. doi: 10.1093/yel/yew011

World Economic Forum (2015). What is ‘new’ about the new development Bank? London: World Economic Forum.

Keywords: BRICS, New Development Bank, financial order, de-dollarisation, governance

Citation: de Castro SKV and Santiago AR (2025) The evolution of financial architecture supporting the BRICS: reshaping the global financial order? Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1657108. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1657108

Edited by:

Carlos Leone, Open University, PortugalReviewed by:

Cintia Quiliconi, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences Headquarters Ecuador, EcuadorDusan Prorokovic, Institut za Medunarodnu Politiku I Privredu, Serbia

Copyright © 2025 de Castro and Santiago. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anabela Rodrigues Santiago, YW5hYmVsYS5zYW50aWFnb0B1YS5wdA==

Suhayla Khalil Viana de Castro

Suhayla Khalil Viana de Castro Anabela Rodrigues Santiago

Anabela Rodrigues Santiago