- 1Department of Sport Science and Sport, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany

- 2Institute of Sport Sciences, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Introduction: While there are several approaches to collect basic information on physical activity (PA) promotion policies, some governments require more in-depth overviews on the situation in their country. In Germany, the Federal Ministry of Health expressed its interest in collecting detailed data on target group specific PA promotion, as relevant competences are distributed across a wide range of political levels and sectors. This study describes the development of a policy brief on physical activity promotion for children and adolescents in Germany. In particular, it addresses two major gaps in the current literature by systematically assessing good practice examples and “routine practices,” i.e., PA promotion activities already taking place on large scale and regular basis.

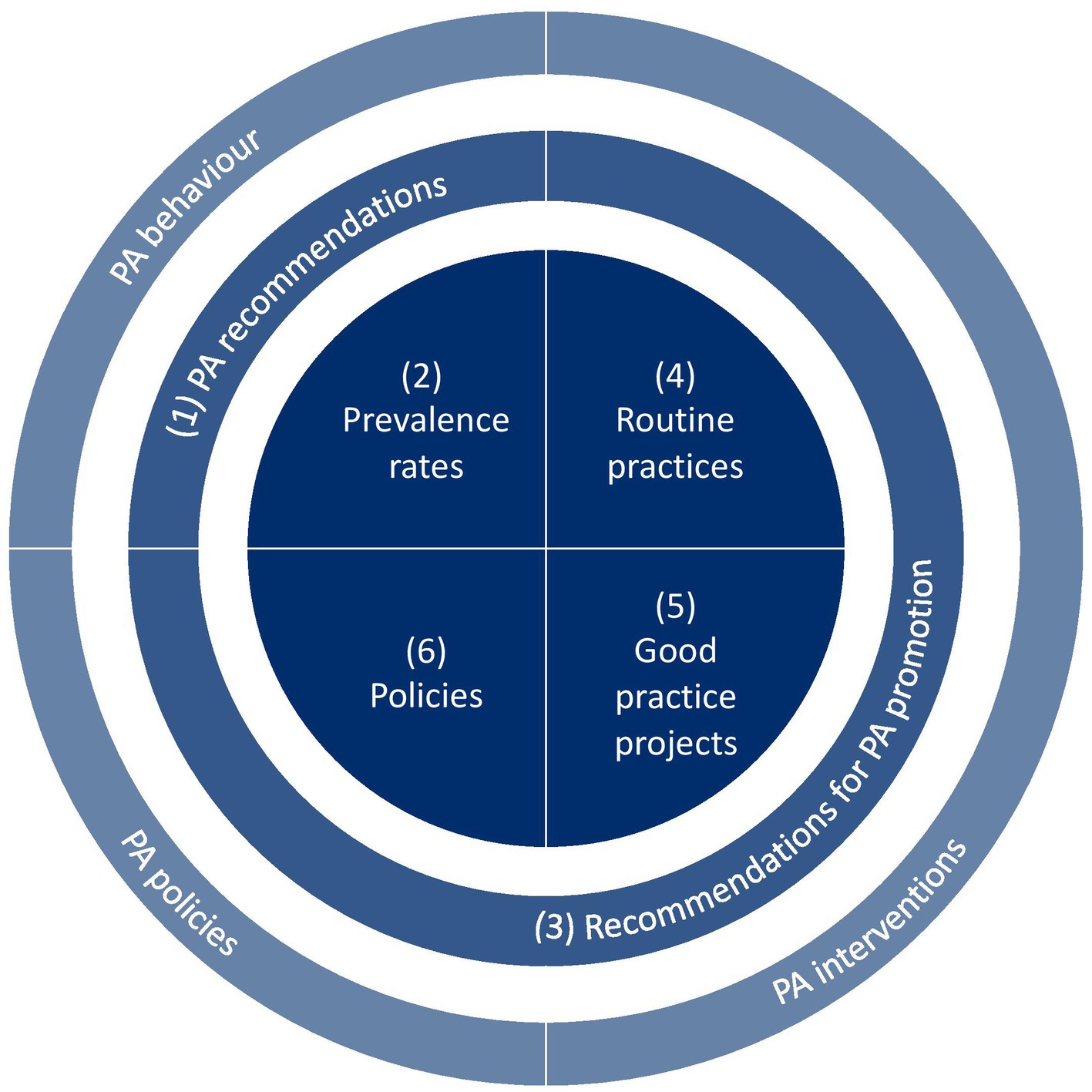

Materials and methods: Based on relevant national and international guidelines, the TARGET:PA tool was co-produced by researchers and ministry officials. It includes (1) PA recommendations, (2) national prevalence rates, (3) recommendations for PA promotion, and data on national (4) routine practices, (5) good practice projects and (6) policies. Data were collected for children and adolescents in Germany using desk research, semi-structured interviews and secondary data analysis.

Results: A policy brief and scientific background document were developed. Results showed that 46% of the 4–5-year-olds fulfil WHO recommendations but only 15% of the 11–17-year-olds, and that girls are less active than boys. Currently, in Germany no valid data are available on the PA behaviour of children under the age of three. An overview of routine practices for PA promotion for children and adolescents was compiled, and experts were asked to critically assess their effectiveness, reach and durability. Overall, 339 target group specific projects for PA promotion were found, with 22 classified as examples of good practice. National PA policies for children and adolescents were identified across different sectors and settings.

Conclusion: The study provides a comprehensive overview of the current status of PA promotion for children and adolescents in Germany. The co-production of the policy brief was a strength of the study, as it allowed researchers to take the needs of ministry officials into account, and as it supported the immediate uptake of results in the policymaking process. Future studies should test the applicability of the TARGET:PA tool to different target groups and countries.

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is a key determinant for the health of children and adolescents, with a positive influence on cardiovascular health, motor fitness, and body weight (1, 2). In addition, regular PA supports physical and mental development (3) and academic performance (4). As an active lifestyle at a young age shapes PA behaviour later in life, promoting PA in children and adolescents is also an investment in the future health of the population (5, 6).

However, while there is sufficient evidence of the health effects of PA, 81% of adolescents aged 11–17 years do not meet the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) for 60 min of moderate- to high-intensity PA per day (7, 8). For this reason, promoting PA within this target group is of outstanding importance, and the effectiveness of respective interventions and policies has been shown in the scientific literature (9–11). Furthermore, international policy documents such as WHO’s Global Action Plan for Physical Activity include specific recommendations for promoting PA among children and adolescents to guide national policy development (12).

To inform the development and review of target group-specific policies to promote PA for children and adolescents, an in-depth analysis of the current status of PA promotion within a country is an important step. For this reason, the German Federal Ministry of Health initiated a data collection exercise including prevalence rates of children and adolescents, target group-specific routine practices, projects, and policies for PA promotion. An important reason for developing this policy brief were consistently high levels of physical inactivity among children and adolescents in Germany, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic due to the closure of day care centers, schools and sport facilities for extended periods of time (13). In addition, children and adolescents are an important target group in the update of the National Action Plan “IN FORM - Germany’s Initiative for Healthy Nutrition and More Physical Activity” (14, 15).

Compared to previous initiatives to monitor PA behaviour and PA promotion practices (16–18), the policy brief addresses two major knowledge gaps: First, rather than following established practice by identifying good practice projects based on expert assessment, it employed an objective and systematic process to ensure the selection of high-quality projects that could be proposed for future scale-up. Second, “routine practices” tend to be a blind spot of current monitoring initiatives, i.e., PA promotion activities taking place on large scale and regular basis. The study at hand systematically assessed such routine practices in Germany, as they are particularly relevant to policymakers due to their high reach and potential public health impact (19).

This manuscript aims to describe the current status of PA promotion for children and adolescents in Germany. It also reflects on the first application of the newly developed data collection tool (TARGET:PA tool; see reference 19) and discusses the added value of this study compared to other attempts to monitor PA behaviour, routine practices, and policies at the national level.

Materials and methods

Data were collected from March to August 2021 using the newly developed TARGET:PA tool that is based on the typology of three types of scientific evidence: PA behaviour, PA interventions, and PA policies (20). In addition, the tool is aligned with two groups of recommendations: PA recommendations that are targeted at individuals (recommended nature, duration, intensity, and volume of PA) and recommendations for PA promotion that target governments and stakeholders (interventions and policies for PA promotion) (21). The tool includes six elements (1): PA recommendations (2), prevalence rates (3), recommendations for PA promotion (4), practices that take place on a routine basis, e.g., due to legal regulations, funding mechanisms or the initiative of organisations (5), evidence-based projects that have proven their efficacy, and (6) policies (Figure 1).

PA recommendations

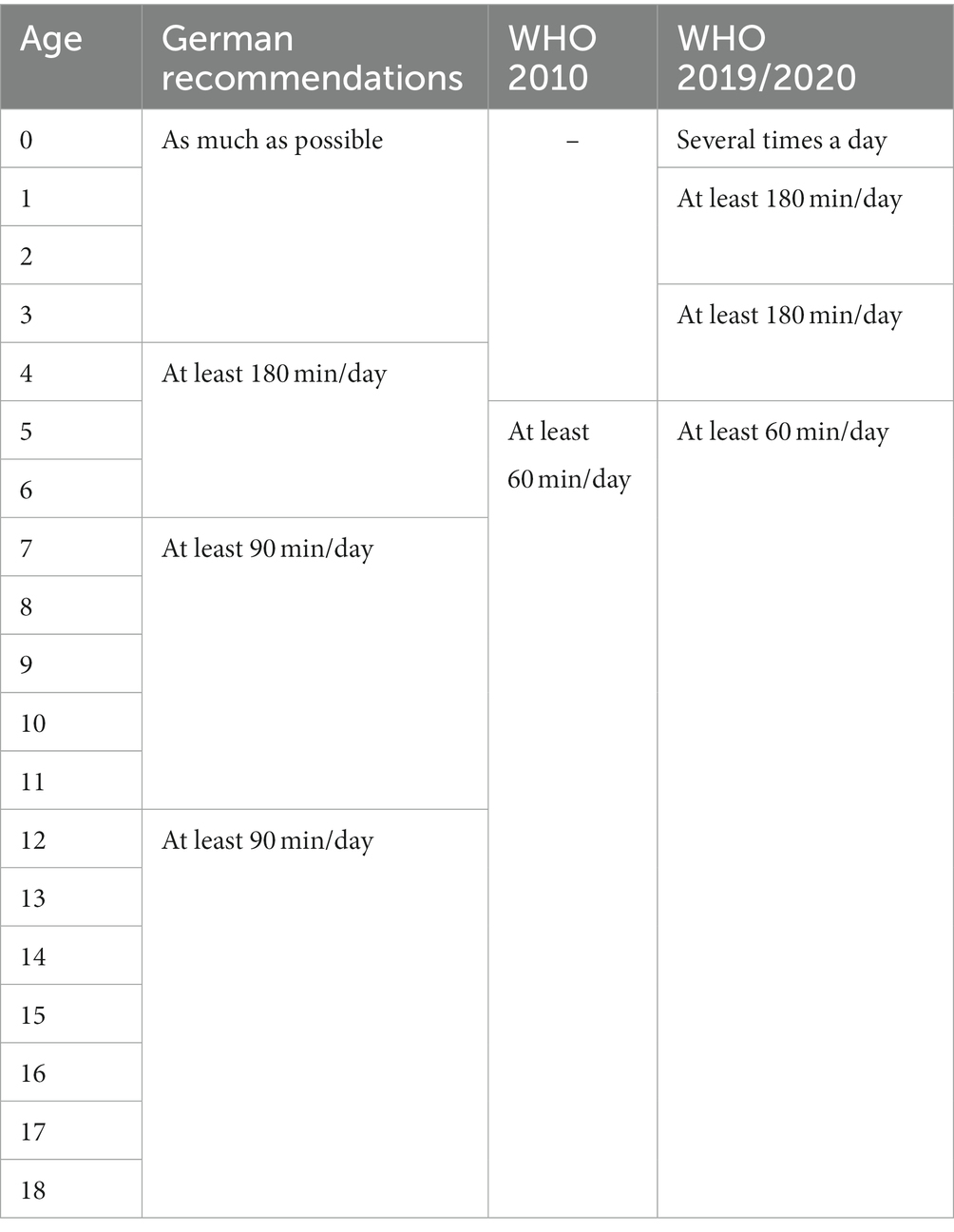

A comparison and synthesis of Germany’s National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion (22) with WHO’s Guidelines on PA and Sedentary Behaviour (8) and WHO’s Guidelines for Children under 5 years of age (23) was performed. WHO’s previous PA guidelines were also included in this comparison (24), as these recommendations were used as a threshold in several studies of prevalence rates (section 2).

Prevalence rates

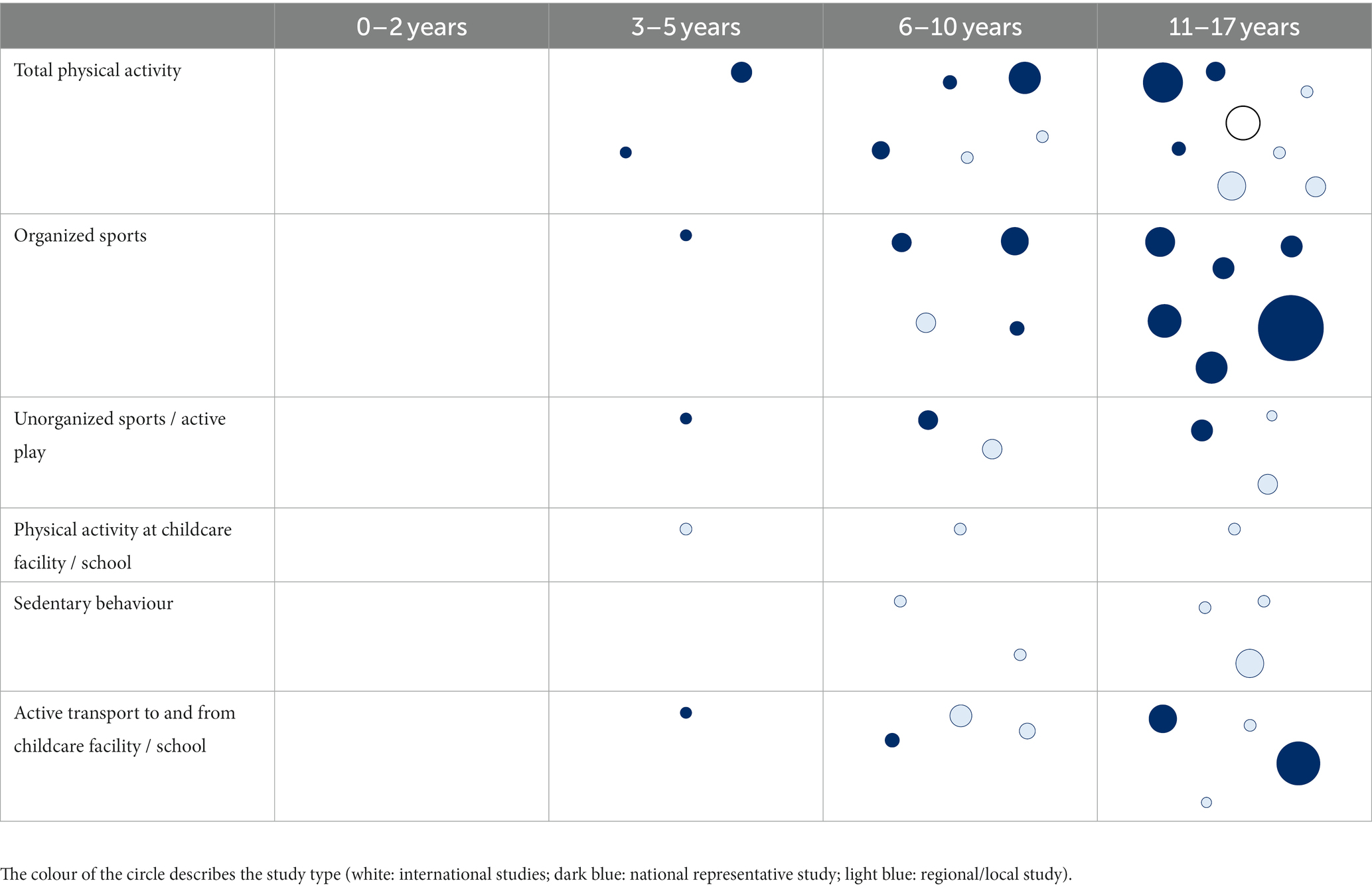

Data on PA prevalence rates of children and adolescents in Germany were collected in a four-step process. First, relevant studies that were collected in three scientific databases (Web of Science, Pubmed, Scopus) were received from the German Active Healthy Kids Network. In addition, a systematic search was conducted to double-check and complement the results. Next, researchers sorted the studies by age (0–2 years, 3–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–17 years) and type of PA behaviour (total PA, organised sports, unorganised sport/active play, PA at a childcare facility/school, sedentary behaviour, active transport). Data on the adherence to PA recommendations were extracted for different age groups; gender-specific differences, socio-economic inequalities, and the changes of PA behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic were also analysed. In addition, data on the sample size were extracted for each study (per age group / PA behaviour) and a bubble chart was created to visualize differences in data availability.

Recommendations for PA promotion

A synthesis of recommendations for PA promotion was performed based on five national, European, and global documents: (1) Germany’s National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion (22), (2) WHO’s Global Action Plan for PA (12), (3) PA Strategy for the WHO European Region 2016–2025 (25), (4) Council Recommendation on promoting Health-Enhancing PA across sectors (26), and (5) the International Society for PA and Health’ Eight Investments that work for PA (27).

To structure the synthesis, categories were developed based on the sectors/settings targeted by the recommendations. These categories were also used to structure the data on routine practices, projects, and policies (see section 4–6).

Routine practices

To identify routine practices, semi-structured expert interviews were conducted. In order to identify experts, the research team created a comprehensive list of 46 individuals with a high expertise in research and practice, covering all categories with recommendations for PA promotion (see section 3). The suitability of the experts was rated on a five-point scale, and for each category the individual with the highest rating was contacted. Six expert interviews were conducted (one expert per category, if possible). These expert interviews took place between April and June 2021 and lasted approximately 45 to 60 min. Experts were asked to identify practices that take place on a routine basis, e.g., due to legal regulations, funding mechanisms or the initiative of organisations (‘routine practices’). For each routine practice, experts were asked to assess the reach, durability, and effectiveness. After each interview, key results were extracted and summarized.

Good practice projects

To identify evidence-based projects that have proven their efficacy, a systematic search was conducted in national project databases. Databases were identified via a study related to the development of Germany’s National Recommendations for PA and PA promotion (28). Five out of eight databases were still available and included projects targeting children and adolescents (29–33). In a subsequent search for relevant databases, no additional databases were identified.

In order to assess these projects, established quality criteria for the conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation of interventions were applied (34). These quality criteria were structured according to the RE-AIM framework (35); afterwards, their number was reduced based on (a) the measurability of each criterion, (b) the relevance of the criterion for the study, and (c) a combination of related criteria. The following combined quality criteria were identified as being of particular relevance for assessing the identified projects:

• Effectiveness: The project has a theoretical foundation, its outcomes were evaluated, and ideally a cost/benefit ratio was determined.

• Reach: The target group was identified, and the target group reach was evaluated.

• Maintenance: The maintenance of the project is prepared, e.g., by the empowerment of stakeholders, the capacity building of organizations and the structural embeddedness of the project.

Good practice projects were selected and assessed in a four-step process. First, projects were sorted into the previously developed categories (see section 3). Second, data were extracted from project databases. Third, projects were selected as examples of good practice when evidence of their effectiveness was identified (inclusion criterion). Fourth, projects were assessed and described based on the three criteria of effectiveness (project outcome), reach (number of children and adolescents or number of facilities), and maintenance (duration of the project). For assessing and describing the projects, additional sources such as project reports, scientific publications, and project websites were used.

Policies

Data on policies for PA promotion for children and adolescents were collected via WHO’s Health Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA) Policy Audit Tools (PAT) (36). These data were obtained from a study within the Policy Evaluation Network (17). As the HEPA PAT is not a target group-specific tool, the results were analysed for policies targeting children and adolescents using (1) a content analysis of HEPA PAT policy documents was conducted to identify links to PA promotion for children and adolescents; additional data were added based on information collected by the WHO Regional Office for Europe as part of the EU HEPA Monitoring Framework (37) and (2) relevant organisations for PA promotion for children and adolescents were identified based on desk research and the results of a study on relevant actors and structures for PA promotion in Germany (38). All results were structured based on the categories developed in section 3.

Results

PA recommendations

National and international recommendations for children and adolescents differ slightly with regards to the recommended levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (8, 22–24) (Table 1).

Prevalence rates

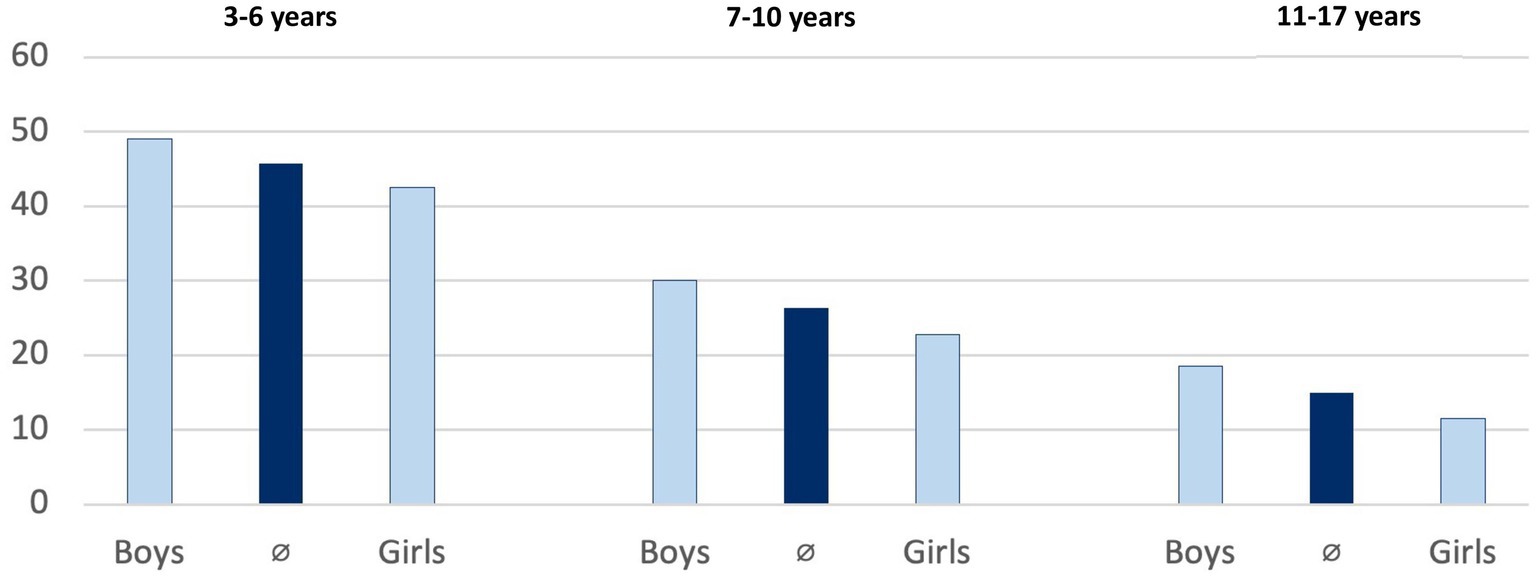

The representative “German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents” (KiGGS) showed that 46 percent of 3- to 6-year-olds met the WHO recommendations in 2014–17, but only 15 percent of 11- to 17-year-olds [(39), Figure 2]. The study showed that girls are less active than boys in all age groups, particularly in adolescence. An additional secondary data analysis of included studies confirmed clear gender differences, showed that the PA behaviour of children and adolescents in Germany depends on the socioeconomic status of their parents, and indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic and containment measures had a negative impact on PA levels of children and adolescents (40).

Most data are available for adolescents aged 11 to 17 years, compared to younger age groups. Currently, there is no data available on the PA behaviour of 0- to 2-year-olds in Germany, and data for children aged 3 to 5 years is limited. Most studies collected data on overall PA levels or the participation in organized sports. Data availability on active transport, active play, PA at childcare facilities or schools, and sedentary behaviour is limited (Table 2).

Table 2. Data availability on PA prevalence rates of children and adolescents in Germany (size of the circle is proportional to the sample size of the study).

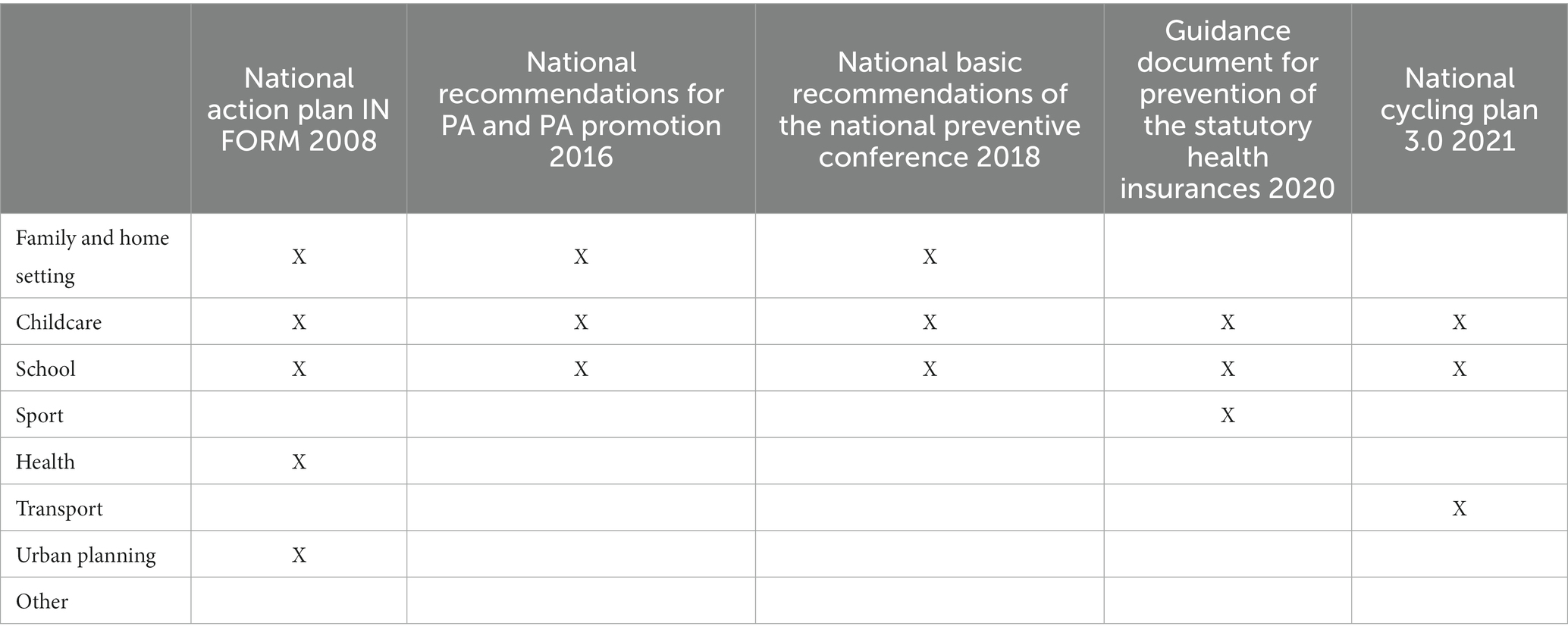

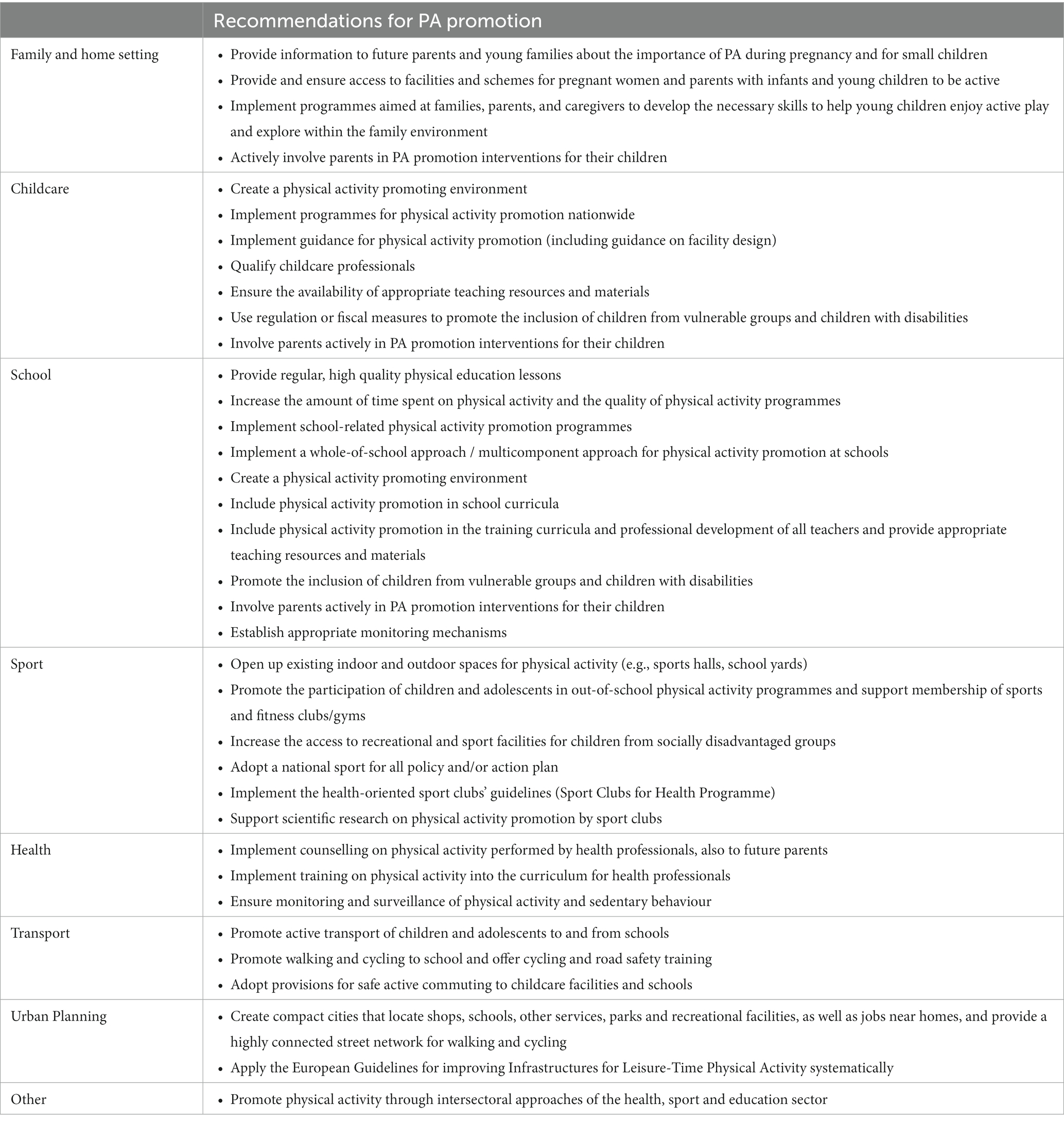

Recommendations for PA promotion

Recommendations for PA promotion exist for the following settings and sectors (1): family and home (2), childcare (3), school (4), sport (5), health (6), transport (7), urban planning, and (8) other (12, 22, 25–27). Most recommendations focus on the school and childcare setting. Some of the recommendations for other settings and sectors are directly targeting children and adolescents (e.g., promotion of active transport to and from schools), while others are relevant for all age groups (e.g., creating compact cities; Table 3).

Table 3. Synopsis of national and international recommendations for PA promotion for children and adolescents.

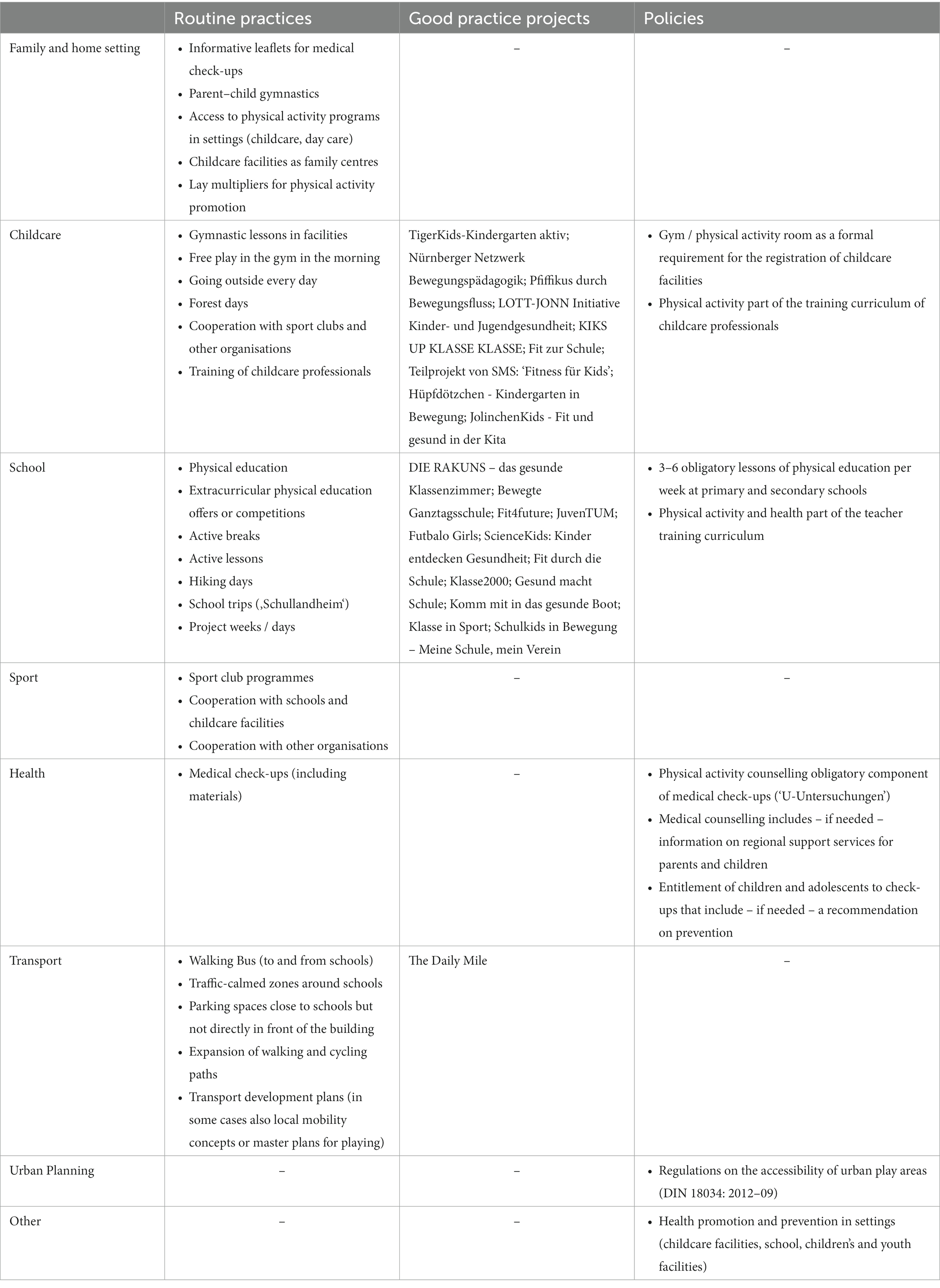

Routine practices

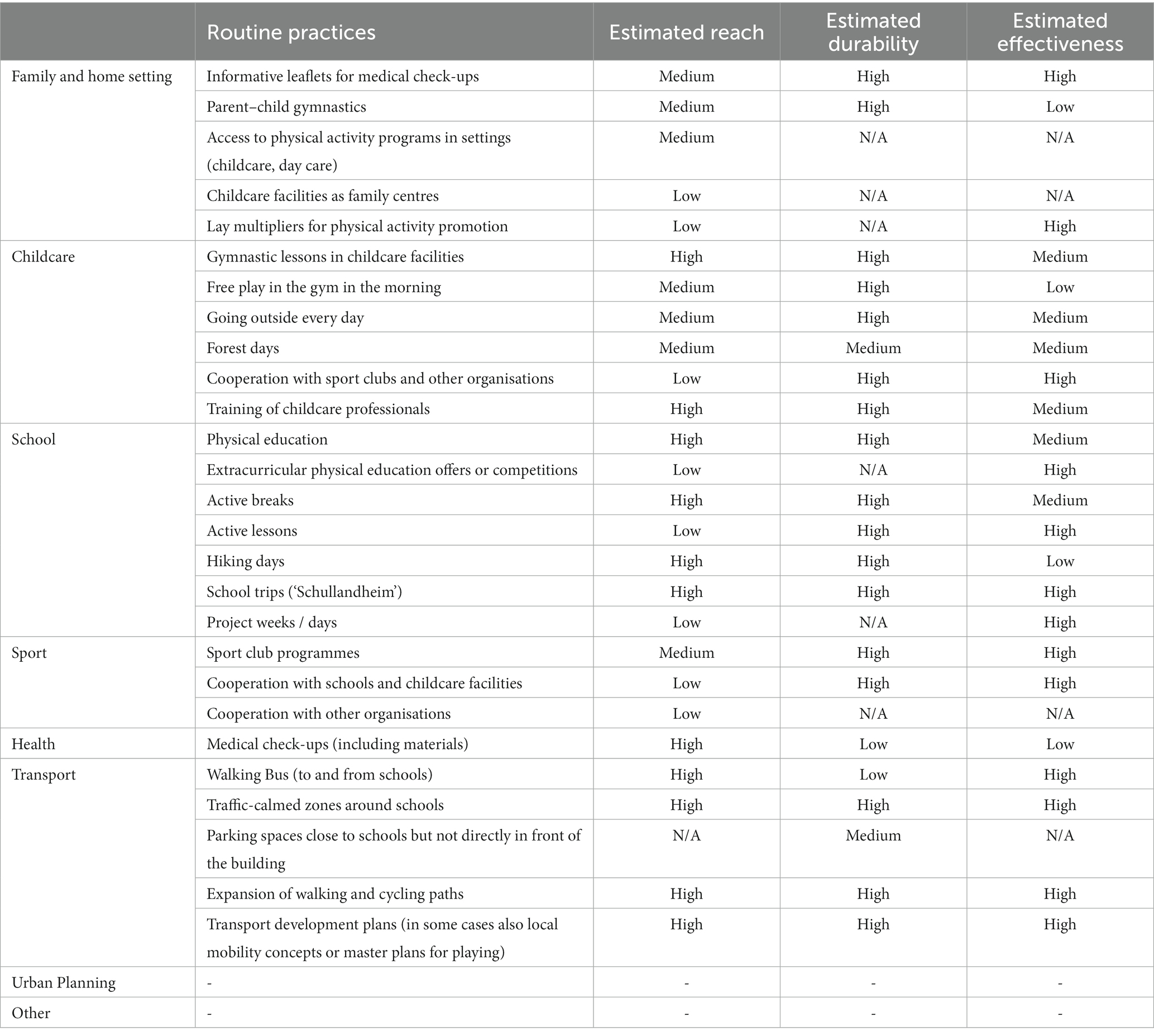

Routine practices for PA promotion for children and adolescents that take place on a regular basis were identified for most of the categories identified in section 3, except urban planning and other (Table 4).

Table 4. Routine practices, good practice projects, and policies for physical activity promotion for children and adolescents in Germany.

In total, 27 routine practices were identified. According to the interviewed experts, the durability of the majority of routine practices was considered to be high (63.0%). However, for less than half of the practices, only the effectiveness (48.1%) and reach (40.7%) were considered to be high. Examples for routine practices with a high reach, durability, and effectiveness were identified in the school sector (school trips) and education sector (traffic-calmed zones around schools, expansion of walking and cycling paths, and transport development plans; Table 5).

Table 5. Assessment of routine practices for physical activity promotion for children and adolescents in Germany.

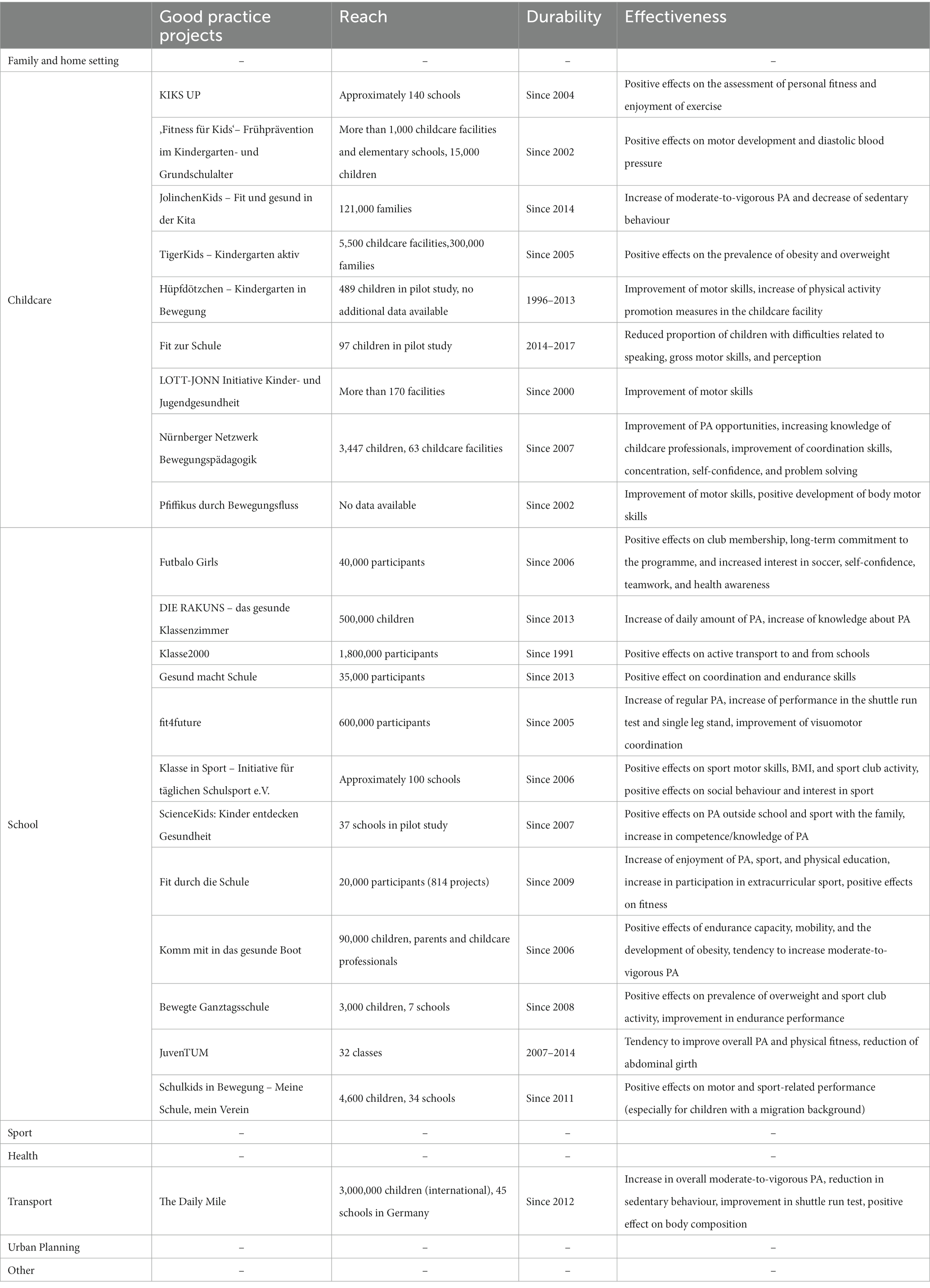

Good practice projects

The database search resulted in 339 projects on PA promotion for children and adolescents. After excluding duplicates and irrelevant projects, the 155 remaining projects were sorted into the eight categories. The majority of projects (65%) took place in childcare facilities or schools. Twenty-two projects met the inclusion criteria and were classified as good practice projects due to their proven effectiveness and a promising reach and/or duration (Table 3).

The included projects differed with regards to the proven effects, e.g., increase of daily amount of PA (DIE RAKUNS), reduced prevalence of obesity and overweight (TigerKids), or improvement of motor skills (LOTT-JONN). One project reached more than 1,000,000 children in Germany (Klasse2000), four projects between 100,000 and 999,999 participants (JolinchenKids, TigerKids, DIE RAKUNS, fit4future), and five projects between 10,000 and 99,999 participants (Fitness für Kids, Futbalo Girls, Gesund macht Schule, Fit durch die Schule, Komm mit in das gesunde Boot). The remaining 12 projects reached either less than 10,000 children and adolescents (e.g., in pilot studies) or only provided information on the number of classes, schools, or childcare facilities that were reached. One project has been running since the 1990s (Klasse 2000), 13 projects since the 2000s, and five projects since the 2010s. Three projects have already been completed (Hüpfdötzchen, Fit zur Schule, JuvenTUM; Table 6).

Table 6. Assessment of good practice projects for physical activity promotion for children and adolescents in Germany.

Policies

Specific regulations to promote PA for children and adolescents exist in different settings and sectors (see examples in Table 3). Additionally, at the level of the federal states, a regular monitoring of physical education lessons takes place and different PA promotion programmes are in place (e.g., “active school,” “walking bus”). Furthermore, the education sector invites representatives of the sport and health sector to participate in the development of the physical education curriculum. In the urban planning sector, single programmes such as “Social City” (Soziale Stadt) or “Experimental Housing and Urban Development” (Experimenteller Stadt- und Wohnungsbau) are linked to health promotion.

Besides these very specific regulations, a number of key policy documents for PA promotion include policies for children and adolescents, especially for the childcare and school setting (Table 7).

Discussion

This study used the new TARGET:PA tool to provide a comprehensive overview of the current status of PA promotion for children and adolescents in Germany. Results showed that 46% of the 3- to 6-year-olds and 15% of the 11- to 17-year-olds fulfil WHO recommendations, and that girls are less active than boys. Currently, no valid data are available on the PA behaviour of 0- to 2-year-olds in Germany. An overview of routine practices for PA promotion for children and adolescents was compiled, and experts were asked to critically assess their effectiveness, reach, and durability. Overall, 339 target group specific projects for PA promotion were found, with 22 classified as good practice projects. National PA policies for children and adolescents were identified across different sectors and settings.

An innovative aspect of this study is the identification of gaps in data availability. Besides the lack of valid data on the PA prevalence rates of 0- to 2-year-olds, data on the PA behaviour of 3- to 5-year-olds were also limited. The analysis also showed that the studies with the largest sample sizes were conducted among the oldest age group (11- to 17-year-olds), indicating that data availability improves for higher aged children and adolescents. These age differences in data availability might be caused by methodological difficulties related to the measurement of PA in infants and young children. While data on participation in organized sports were collected in several surveys, data availability on active transport and PA behaviour at school – outside physical education lessons – is limited. There are also limited studies and inconclusive data on the influence of the parents‘socioeconomic status and migration background on the PA behaviour of their children as well as on gender-dependent social gradients.

Another novel aspect in this study is the integrated analysis of recommendations for PA promotion, routine practices, good practice projects, and policies. The analysis of these elements was based on eight categories that were derived from national and international recommendations for PA promotion. A strong focus on the childcare and school setting was identified – especially for projects (21 out of 22 good practice projects targeted one of these two settings) but also for recommendations and policies. The inclusion of routine practices is a unique focus of this study; data on this aspect have hardly been collected previously in the field of PA promotion, as research usually focuses either on identifying good practice projects (e.g., reference 28) or on monitoring policies for PA promotion (e.g., reference 41). However, this aspect is especially relevant as the reach of routine practices is often much higher than the reach of single projects. In contrast, in many cases the effectiveness of routine practices for PA promotion has not been investigated, while the selected good practice projects have proven their effectiveness. This calls for analysis of the effectiveness of routine practices and raises the question of how routine practices can be modified to increase their public health impact.

This study of PA promotion for children and adolescents in Germany was the first application of the newly developed TARGET:PA tool (19). Based on this study, researchers and ministry officials co-produced a policy brief (42) and a scientific background document (40). Both documents were published by the Federal Ministry of Health in the context of a national Physical Activity Summit in December 2022 that focused on promoting sports and PA, especially among children and adolescents – as this target group was particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to the closure of sport facilities and the cancellation of physical education lessons (43). In the context of this summit, the Federal Ministry set up a Round Table on PA and Health with key stakeholders from different sectors that aimed to agree on specific measures for target group-specific PA promotion. The above-mentioned policy brief was an important basis for this Round Table and was also utilized as the first in a series of brief updates to the German National Recommendations for PA and PA promotion conducted under the auspices of the Federal Ministry of Health. As such it had an immediate impact on the political debate of key stakeholders.

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. First, the study was conducted on an ad hoc basis, i.e., based on an urgent request from the Ministry of Health and not planned in advance. In order to inform policymaking within and outside the Federal Ministry of Health in a timely manner, data collection was based on a rapid but systematic process. However, if time was not limited, the methodology could have been adjusted to collect more data on specific aspects such as routine practices and/or to analyse data more in-depth. Second, the identification of experts for the semi-structured interviews was difficult for sectors that are relevant for PA promotion but might not necessarily perceive this as one of their key tasks (e.g., urban planning). For this reason, the overview of routine practices might not be complete. However, due to the limited body of evidence on this aspect, this is still a step forward and could be a starting point for future research. Third, the relevant settings for PA promotion were analysed separately and intersectoral initiatives for PA promotion were not identified systematically. Fourth, with regards to the identification of good practice projects, it must be noted that existing databases do not provide a complete overview about all projects for PA promotion. In some cases, project databases seemed to be outdated (i.e., no new projects have been added in recent years) and did not provide access to further information (i.e., websites, project reports). The incentive for a database entry was unclear in many databases and the provided information was very heterogenous. Lastly, data collection on PA promoting policies was based on tools that do not collect target group specific information, such as WHO’s HEPA PAT and the EU/WHO HEPA Monitoring Framework, and is limited to national level policies. Additional target group specific surveys and research focusing on the subnational level could help to identify additional policies relevant for PA promotion of children and adolescents in Germany.

The following key conclusions for policymaking in Germany can be drawn from this study:

• PA recommendations: Existing national and international recommendations for children and adolescents vary due to their different years of origin and the advancing scientific evidence. National recommendations should be updated in regular intervals, e.g., every 5 years.

• Prevalence rates: Efforts for PA promotion for children and adolescents need to be increased, as a decreasing proportion meet current PA recommendations as they get older. The needs of girls should be given special consideration. In addition to the continuous monitoring of PA behaviour in children and adolescents from (pre-)school age, an initial data collection is needed for children under 3 years of age.

• Recommendations for PA promotion: National and international recommendations for PA promotion should be implemented systematically.

• Routine practices: The reach and effectiveness of routine practices for PA promotion among children and adolescents should be increased and monitored on a regular basis.

• Good practice projects: The nationwide dissemination of good practice projects in the school, childcare facilities, and transport settings should be examined. As no good practice project was identified for other settings, future studies should investigate the effectiveness of projects in these settings.

• Policy: A systematic monitoring of policies for PA promotion in Germany should be implemented across the different levels of government (national level, federal states, and municipalities). In addition, the networking of relevant organizations needs to be facilitated across political levels and sectors to strengthen structures for PA promotion in Germany.

Conclusion

From a more general perspective, the study was the first implementation of the TARGET:PA tool and provided a comprehensive overview of the current status of PA promotion for children and adolescents in Germany. Furthermore, the study confirmed the added value of the tool for monitoring activities in the field of PA promotion, and it closed a research gap by systematically assessing good practice examples as well as routine practices. The co-production of the policy brief and the scientific background document was a strength of the study, as it allowed researchers to take the needs of ministry officials into account at each stage of the process. This supported the immediate uptake of the results in the policymaking process coordinated by the Federal Ministry of Health, e.g., for the establishment of a national and intersectoral Round Table on PA and Health. The TARGET:PA tool is designed to be applicable to other target groups and in other countries; however, future studies need to test whether the tool needs to be modified when applied in another context.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to study conceptualization and design. FB, KA-O, and AR analysed data related to PA recommendations and prevalence rates. SM and PG analysed recommendations for PA promotion and policies. KA-O, SM, EG, and WG analysed routine practices. IM analysed good practice projects. PG and SM coordinated data collection and analysis, KP and AR supervised the study. SM wrote the original manuscript draft. KA-O, PG, and AT provided feedback on early drafts. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of a project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (ZVI1-2521WHO001). The ministry was neither involved in writing this manuscript nor in the decision to submit the article for publication. In addition, we acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg within the funding program “Open Access Publication Funding”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Janssen, I, and LeBlanc, A. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2010) 7:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40

2. Poitras, VJ, Gray, CE, Borghese, M, Carson, S, Chaput, JP, Janssen, I, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2016) 41:S197–239. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0663

3. Bidzan-Bluma, I, and Lipowska, M. Physical activity and cognitive functioning of children: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040800

4. Barbosa, A, Whiting, S, Simmonds, P, Scotini Moreno, R, Mendes, R, and Breda, J. Physical activity and academic achievement: an umbrella review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165972

5. Pongiglione, B, Kern, ML, Carpentieri, JD, Schwartz, HA, Gupta, N, and Goodman, A. Do children’s expectations about future physical activity predict their physical activity in adulthood? Int J Epidemiol. (2020) 49:1749–58. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa131

6. Telama, R, Yang, X, Leskinen, E, Kankaanpaa, A, Hirvensalo, M, Tammelin, T, et al. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2014) 46:955–62. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000181

7. Guthold, R, Stevens, GA, Riley, LM, and Bull, FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet child and adolescent. Health. (2020) 4:23–35. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2

9. Gelius, P, Messing, S, Goodwin, L, Schow, D, and Abu-Omar, K. What are effective policies for promoting physical activity? A systematic review of reviews. Prev Med Rep. (2020) 18:101095. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101095

10. Messing, S, Rütten, A, Abu-Omar, K, Ungerer-Röhrich, U, Goodwin, L, Burlacu, I, et al. How can physical activity be promoted among children and adolescents? A systematic review of reviews across settings. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:55. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00055

11. Woods, CB, Volf, K, Kelly, L, Casey, B, Gelius, P, Messing, S, et al. The evidence for the impact of policy on physical activity outcomes within the school setting: a systematic review. Journal of sport and health. Science. (2021) 10:263–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2021.01.006

12. WHO (2018). Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: More active people for a healthier world. Geneva.

13. Schmidt, SCE, Burchartz, A, Kolb, S, Niessner, C, Oriwol, D, Hanssen-Doose, A, et al. (2021). Zur Situation der körperlich-sportlichen Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen während der COVID-19 Pandemie in Deutschland: Die Motorik-Modul Studie (MoMo). KIT Scientific Working Papers.

15. Bundesministerium für Ernährung Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz, Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2008). IN FORM. Deutschlands Initiative für gesunde Ernährung und mehr Bewegung. Nationaler Aktionsplan zur Prävention von Fehlernährung, Bewegungsmangel, Übergewicht und damit zusammenhängenden Krankheiten.

16. Demetriou, Y, Hebestreit, A, Reimers, AK, Schlund, A, Niessner, C, Schmidt, S, et al. Results from Germany’s 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J Phys Act Health. (2018) 15:S363–5. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0538

17. Messing, S, Forberger, S, Woods, C, Abu-Omar, K, and Gelius, P. Politik zur Bewegungsförderung in Deutschland. Eine Analyse anhand eines Policy-Audit-Tools der Weltgesundheitsorganisation. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. (2021) 65:107–15. doi: 10.1007/s00103-021-03403-z

18. European Commission (2021). WHO regional Office for Europe. Germany physical activity factsheet 2021. Available at: https://sport.ec.europa.eu/document/germany-physical-activity-factsheet-2021 (Accessed May 03, 2023).

19. Gelius, P, Messing, S, Abu-Omar, K, Tcymbal, A, Beck, F, Geidl, W, et al. (n.d.). Target group specific policy monitoring for physical activity promotion – The TARGET:PA tool. In preparation.

20. Rütten, A, Schow, D, Breda, J, Galea, G, Kahlmeier, S, Oppert, J-M, et al. Three types of scientific evidence to inform physical activity policy: results from a comparative scoping review. Int J Public Health. (2016) 61:553–63. doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0807-y

21. Leone, L, and Pesce, C. From delivery to adoption of physical activity guidelines: realist synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101193

22. Rütten, A, and Pfeifer, K. National recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion. Erlangen: FAU University Press (2016).

23. WHO (2019). Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. Geneva.

26. Council of the European Union (2013). Council recommendation on promoting health-enhancing physical activity across sectors. Brüssel.

27. ISPAH (2020). Eight investments that work for physical activity. Available at: https://www.ispah.org/resources/key-resources/8-investments/ (Accessed May 03, 2023).

28. Henn, A, Karger, C, Wöhlken, K, Meier, D, Ungerer-Röhrich, U, Graf, C, et al. Identifikation von Beispielen guter Praxis der Bewegungs förderung – Methoden, Fallstricke und ausgewählte Ergebnisse. Das Gesundheitswesen. (2017) 79:S66–72. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123697

29. Bayerisches Zentrum für Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung (2021). Gesundes Aufwachsen in der Familie, in Kindertageseinrichtungen, in sonstigen Einrichtungen der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe und in der Schule.

32. IN FORM (2021). Projekte. Available at: https://www.in-form.de/netzwerk/projekte/ (Accessed May 03, 2023).

33. Landesinstitut für Gesundheit und Arbeit des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen (2021). Projektdatenbank.

34. Messing, S, and Rütten, A. Qualitätskriterien für die Konzipierung, Implementierung und Evaluation von Interventionen zur Bewegungsförderung: Ergebnisse eines State-of-the-Art Reviews. Das Gesundheitswesen. (2017) 79:S60–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123378

35. Glasgow, RE, Harden, SM, Gaglio, B, Rabin, B, Smith, ML, Porter, GC, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

36. Bull, FC, Milton, K, and Kahlmeier, S. (2015). Health-enhancing physical activity (HEPA) policy audit tool (PAT). Version 2. In: WHO Europe,. Copenhagen.

37. WHO (2021). Physical activity factsheets for the European Union member states in the WHO European region. Copenhagen 2021.

38. Wäsche, H, Peters, S, Appelles, L, and Woll, A. Bewegungsförderung in Deutschland: Akteure, Strukturen und Netzwerkentwicklung. Bewegungstherapie Gesundheitssport. (2018) 34:257–73. doi: 10.1055/a-0739-9857

39. Finger, JD, Varnaccia, G, Borrmann, A, Lange, C, and Mensink, GBM. Körperliche Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland - Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle2 und Trends. J Health Monitor. (2018) 3:24–31.

40. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2022). Bestandsaufnahme zur Bewegungsförderung bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland (Langversion). Available at: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/publikationen.html (Accessed May 03, 2023).

41. Messing, S, Tcymbal, A, Abu-Omar, K, and Gelius, P. (2023). Research- vs. government-driven physical activity policy monitoring: a systematic review across different levels of government. Research Square. Preprint.

42. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2022). Bestandsaufnahme zur Bewegungsförderung bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland (Kurzversion). Available at: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/publikationen.html (Accessed May 03, 2023).

Keywords: physical activity promotion, policy brief, policy consultation, children, adolescents, recommendations, projects, policy

Citation: Messing S, Gelius P, Abu-Omar K, Marzi I, Beck F, Geidl W, Grüne E, Tcymbal A, Reimers AK and Pfeifer K (2023) Developing a policy brief on physical activity promotion for children and adolescents. Front. Public Health. 11:1215746. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1215746

Edited by:

Chakema Carmack, University of Houston, United StatesReviewed by:

Dana Badau, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureş, RomaniaBirute Strukcinskiene, Klaipėda University, Lithuania

Copyright © 2023 Messing, Gelius, Abu-Omar, Marzi, Beck, Geidl, Grüne, Tcymbal, Reimers and Pfeifer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sven Messing, sven.messing@fau.de

Sven Messing

Sven Messing Peter Gelius

Peter Gelius Karim Abu-Omar

Karim Abu-Omar Isabel Marzi

Isabel Marzi Franziska Beck

Franziska Beck Wolfgang Geidl

Wolfgang Geidl Eva Grüne

Eva Grüne Antonina Tcymbal

Antonina Tcymbal Anne Kerstin Reimers

Anne Kerstin Reimers Klaus Pfeifer

Klaus Pfeifer