- 1Research Center for Diversity and Inclusion, The Institute for Diversity and Inclusion, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan

- 2Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan

- 3School of Economics and Management, Kochi University of Technology, Kochi, Japan

- 4Research Institute for Future Design, Kochi University of Technology, Kochi, Japan

- 5Department of Behavioral Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan

- 6Center for Experimental Research in Social Sciences, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan

Communication is crucial to resolving conflicts such as social dilemmas. Previous literature concurs that communication among all group members increases cooperation. However, gathering all the members is often difficult. Hence, the effect of communication among some group members needs to be examined. The current study addressed this notion in a public goods experiment framework measuring the social value orientation of individuals. We conducted a six-person public goods game 20 times with members fixed. Between the 10th and 11th periods, we implemented different communication tactics: communication among all members, communication among three members selected randomly, or no communication (control). We observed that communication among some members increased the cooperation rate compared to no communication; however, the effect was weaker when compared with communication among all the members. Furthermore, partial communication increased the cooperation rate of prosocial individuals regardless of whether to join the communication process themselves. Proself individuals, on the contrary, cooperated as long as they communicated. Non-communicating members did not decrease their perception of goal-sharing and reciprocity compared to communicating members. These observations affirm that communication among some members is beneficial, even if assembling all the members is not always feasible.

1 Introduction

Social conflicts have been commonly resolved by coordinating stakeholders' interests via communication. A social dilemma is one such conflict existing between the short-term personal benefits of non-cooperation and the long-term social benefits of cooperation (Dawes, 1980). Numerous laboratory experiments on social dilemmas revealed that communication facilitates cooperation (Ledyard, 1994; Ostrom, 1990).1 Meta-analyses also supported communication's effectiveness (Balliet, 2010; Sally, 1995; Zelmer, 2003).

In most of the previous literature, all group members simultaneously join the communication process. However, gathering all of them is often difficult; hence, only some members gather to discuss all the members' issues. Does partial communication still enhance cooperative behavior? Specifically, how does partial communication impact members who know that communication proceeds in their group but do not participate in it themselves? After communication, non-communicating members may cooperate more, expecting cooperation from the communicating members. Conversely, they may cooperate less, feeling that other members do not expect them to cooperate. We take voluntary contributions to public goods provision as a social dilemma and compare in the laboratory the degree of contribution according to the proportion of members included in the communication (zero, half, or all). Based on previous literature on the effectiveness of communication in promoting cooperation, we hypothesize that the contribution amount is proportional to the proportion of communicating members in a group.

When laboratory experiments focus on partial interactions in social dilemma games, participants are connected in two ways. First, the game structure connects each participant's payoffs with only her neighbors. Rezaei et al. (2024) estimated each participant's social preferences from their decision data to explain the group outcomes of the local public goods game (Bramoullé and Kranton, 2007). Polzer et al. (2001) used the nested social dilemma game (Wit and Kerr, 2002), in which participants choose how much to contribute to their personal, subgroup, and collective accounts. In the helping game (Erkut and Reuben, 2023), participants can choose which members they provide benefits to.

Second, a communication opportunity is provided before playing a game, but each member can communicate with only some other members. Our experiment belongs to this category. In the public goods experiments by Braver and Wilson (1986) and Kinukawa et al. (2000), every member can communicate with someone else, but not all the members get together. Erkut and Reuben (2023) also compare various communication networks. Pronin and Woon (2023) prepare a one-by-one private chat opportunity before all members communicate through a public chat and vote on the proposals for each member's contribution to a public good provision. In the studies by Schmitt et al. (2000: common-pool problem), Polzer et al. (2001), and Abbink et al. (2018: three-person dilemma), some group members are excluded from communication, and who are excluded is predetermined (i.e., outsiders, subgroups, partners and a lone person), whereas our experiment determines it by lot immediately before communication. The result of Polzer et al. (2001) is consistent with ours: the collective contributions with subgroup communication were more outstanding than those with no communication but smaller than those with full-group communication. However, our result from the public goods framework does not rely on subgroup accounts. Abbink et al. (2018) had a similar interest to us: to what extent excluded participants would contribute. In their game, any pair of members can exploit the third member. Hence, allowing two members to communicate privately induces the excluded member to anticipate exploitation and reduces her motivation to contribute. In our public goods experiment, participants cannot exploit any particular person; however, some excluded participants still reduced their contributions.2

Pruitt and Kimmel (1977) review previous experimental studies using repeated prisoners' dilemma games, advocating that sharing common goals and expecting mutual cooperation lead to actual cooperation. This is because players can behave reciprocally toward the other's past behavior in repeated games. Therefore, in our multi-period experiment, we also regard sharing common goals and perceiving reciprocity as the possible intermediaries between communication and cooperation and examine their significance. People refer to common goals through communication, and in turn, communication leads to forming shared goals with others (McClung et al., 2017; Kanngiesser et al., 2024; Wyman et al., 2013; Duguid et al., 2014). However, members who do not join communication have no direct means of sharing a common goal with other members. Hence, we hypothesize that non-communicating members share a common goal to a lower degree than communicating members, and their intention to act reciprocally would also be reduced.

Furthermore, individual preferences may raise different expectations for other members' behaviors. Based on the previous literature's assumption that individuals systematically differ in their interpersonal preferences, we measure each individual's social value orientation (SVO: Messick and McClintock, 1968; Van Lange, 1999; Van Lange et al., 2007) as per the approach of Eek and Gärling (2006) and analyze the communication-cooperation relationship according to the type of SVO. Bogaert et al. (2008) built upon Pruitt and Kimmel (1977), claiming that different SVOs exert varying influences on cooperative goals and expectations of reciprocity. Aksoy and Weesie (2012) revealed that proselfs perceive others as self-interested, whereas prosocials predict others as both self-interested and altruistic. Prosocials are more reciprocal (Van Lange, 1999; Pletzer et al., 2018) and possess better theory of mind skills, as well as the ability to adopt another person's point of view (Declerck and Bogaert, 2008). Comprehending these findings, prosocials who do not communicate may anticipate the cooperative behavior of communicating members, potentially prompting them to reciprocate. We hypothesize that prosocials share a common goal, intend to act reciprocally, and contribute more than proselfs, both when they participate in communication and when they do not. If this is true, the decline in contributions would not be severe when non-communicating members are prosocials.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

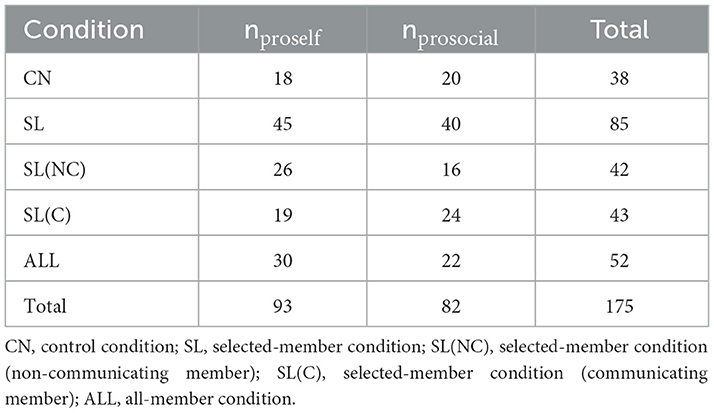

A priori power analysis (G*Power; Faul et al., 2007, 2009) with an effect size of f = 0.3 from previous research determined a minimum sample size of 96 participants (significance level α = 0.05, power = 0.8). To account for the potential uneven SVO distribution across conditions, we recruited participants to ensure at least 12 per cell. Altogether, 186 students at Kochi University of Technology and Hokkaido University participated in our experiment in exchange for a monetary reward. We excluded 11 participants from the analyses (10 showed inconsistency in SVO responses and one failed to complete the post-questionnaire), leaving 175 participants (99 males, 75 females, one preferred not to answer; aged 18–26; Mage = 20.15, SDage = 1.41).3 Table 1 shows the participant distribution by SVO and condition. The SVO classification is described in Section 2.2. This research was approved by the research ethics committees of Kochi University of Technology (35-C1) and Hokkaido University (H28-7, R6-30).

2.2 Procedure and design

In each session, participants were randomly and anonymously assigned to six-person groups to participate in a public goods game for 20 periods. They were informed that they belonged to a six-person group, but their group members were not initially disclosed. Group composition remained the same throughout the 20 periods.

Each session was randomly assigned to one of the three conditions of communication: all members, selected members, and no communication (control). In sessions with communication, a 5-min face-to-face communication opportunity was provided between the 10th and 11th periods. All group members could communicate under the all-member condition. Under the selected-member condition, an experimenter drew a lot publicly to determine three of the six members who joined the communication procedure immediately before the communication initiation. Participants who joined the communication moved to other rooms group by group, whereas the others stayed at their computer terminals. Members who joined the communication found that they belonged to the same group. After communication, they returned to their computer terminals to play the 11th period. The control condition provided no opportunity for communication but did include a 5-min break.

Note that in the communication conditions, participants entered a shared social environment where they met face-to-face, whereas this was not the case in the control condition. Therefore, comparisons between control and communication conditions reflect the combined effect of communication and being in a social environment.

Each session lasted approximately 60 to 90 min. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants drew lots to determine their computer terminals, which were separated by partitions. They could not see the other participants' computer screens but could see their heads and were aware of their presence. During the experiment, the participants were not allowed to talk to each other without the experimenter's permission. All decisions were made via computer software z-Tree (Fischbacher, 2007). At the beginning of each session, written instructions were distributed and read aloud, explaining the experiment's procedure, the game's rules, and payoffs. After providing the instructions, the experimenter answered the questions from the participants individually. Then, the first of the 20 periods of the public goods game began.

Periods were independent of each other. Although the outcomes of the current period were shown on each participant's computer screen, no results were carried over to the next period. At the beginning of each period, each group member received 10 coins. They decided simultaneously and independently how many coins to allocate to option A (i.e., private-good consumption) and option B (i.e., public-good provision) on their computer screens (i.e., from 0 to 10 coins for option A). Each member earned 10 points for each coin allocated to option A, while each member's points earned from option B were the sum of coins contributed by all members to option B, multiplied by four per coin. Participants knew that this payoff structure was common knowledge among all group members. Each participant's computer screen displayed his or her decision, the sum of coins allocated to option B by all group members, and his or her earnings.

Participants earned 0.5 yen (approximately $0.0035 if $1 = 140 yen) per point, and they received monetary rewards (mean = 1,895 yen [$13.54]; maximum = 3,177 yen [$22.69]; and minimum = 960 yen [$6.86]) at the end of the experiment. Additionally, due to a change in the legal minimum hourly wage, some experiments were conducted with an additional 700 yen show-up fee. Participants were informed of this fee after completing the experiment.

After the 20th period, all participants completed a questionnaire that included items classifying their SVO and measuring the degrees of goal sharing and reciprocity perceived in the public goods game. We utilized the SVO items as per the process defined by Eek and Gärling (2006). Each participant determined how to allocate hypothetical resources between himself or herself and another supposedly unknown person. Overall, 12 allocation tasks with four alternatives each were provided. Each alternative was characterized such that it (1) maximizes his or her outcome (individualist), (2) maximizes the difference in outcome between himself or herself and another person (competitor), (3) achieves equality between them (equalitarian), or (4) maximizes their joint outcome (utilitarian). A participant was classified into one of the four types if he or she chose one type of alternative at least eight times during the 12 tasks. Participants were classified as 90 individualists, 3 competitors, 52 equalitarians, and 30 utilitarians. Furthermore, 10 participants were not valid for either type of SVO. Individualists and competitors were aggregated as proselfs, while equalitarians and utilitarians were classified as prosocials (Van Kleef and Van Lange, 2008).

The degrees of sharing a common goal and perceiving reciprocity were gauged on a seven-point scale, from 1 (I do not agree at all) to 7 (I agree very strongly), with the following items.4 We calculated Cronbach's alpha coefficient between these items to confirm that there were no problems in treating them as a unified scale. For sharing a common goal, three items were prepared: “my goal is to increase the profits of the whole group,” “everyone in my group is trying to increase the profits of the whole group,” and “all my group members know that each member is targeting the profits of the whole group” (α = 0.70). For reciprocity, six items were prepared: “if I allocate coins to B, other members would (should) also allocate coins to B,” “if other members allocate coins to B, I would (should) also allocate coins to B,” “I felt like I had to allocate many coins to B,” and “I did not think about the other members” (reversed item) (α = 0.80).

3 Result

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS University Edition. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for testing the hypotheses.

3.1 SVO classification of participants by condition

The SVO distribution did not differ significantly across conditions with and without dividing the selected-member condition participants into two groups, those who communicated and those who did not, χ2s > 0.94, ps > 0.31, Cramer's V = 0.07 and V = 0.14, respectively.

3.2 Cooperation rate

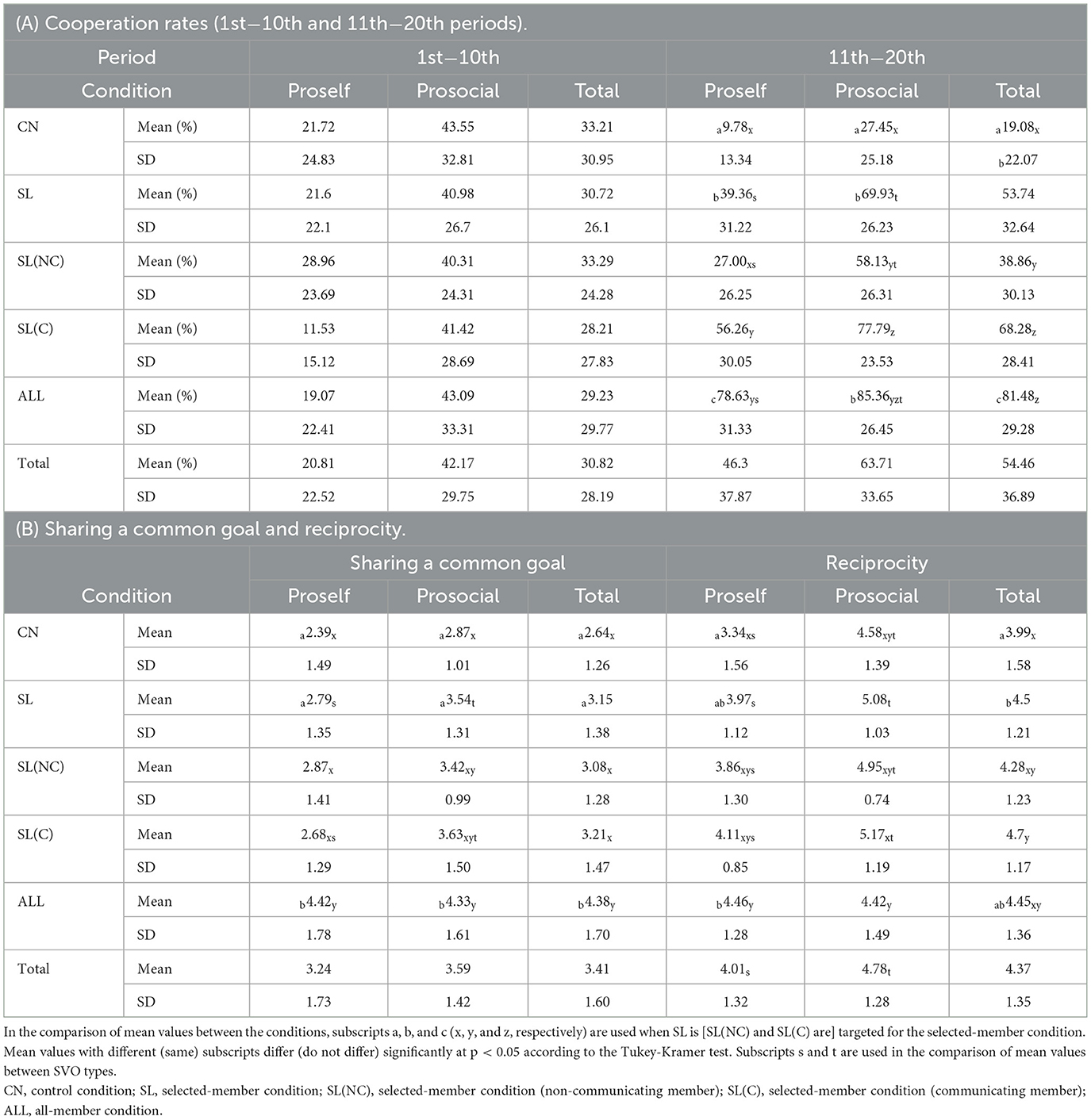

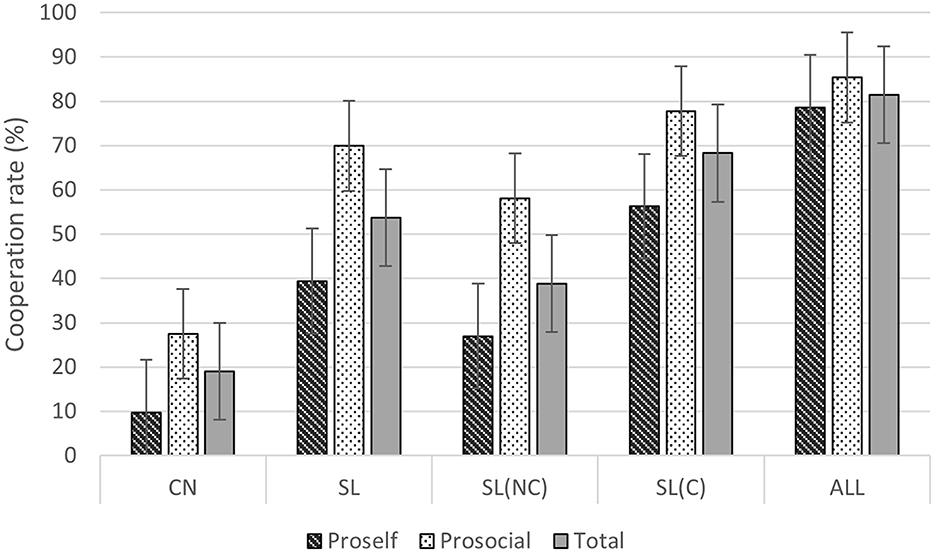

We employed a linear mixed model to compare the average contribution to the public good provision from the 11th to the 20th period across the conditions and SVOs (see Table 2A; Figure 1). The model integrated fixed effects for the condition, SVO, and period. The average contribution from the 1st to the 10th period served as a covariate. Besides, random effects for each session's participants and groups were incorporated. We obtained a significant main effect of the condition, F(2, 235.1) = 12.54, p < 0.01. According to the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test, the cooperation rate was highest in the all-member condition, followed by the selected-member condition and the control condition (|ts| > 3.76, ps < 0.01).

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of cooperation rates (%) (A) and sharing a common goal and reciprocity (B).

Figure 1. Bar chart of cooperation rates for periods 11-20 across different conditions: CN (no communication); SL (selected-member communication, aggregated); SL (NC) non-communicating subgroup within SL; SL (C) communicating subgroup within SL; and ALL (all-member communication). Each condition shows three bars for Proself, Prosocial, and Total (Proself + Prosocial combined). Bars display mean percentages with standard-error whiskers. Cooperation increases from CN to ALL, with Prosocial generally higher than Proself. X-axis lists conditions; Y-axis shows cooperation rate (percent).

The linear mixed model did not report any significant main effect of SVO or period, nor an interaction effect between the condition and SVO, Fs < 1.44, ps > 0.23. Still, the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison post hoc test revealed significant differences between the conditions for each SVO type. As for the proselfs, the cooperation rate was highest in the all-member condition, followed by the selected-member condition and the control condition (|ts| > 3.10, ps < 0.01). With regards to the prosocials, the cooperation rate in the selected-member condition was significantly higher than in the control condition, t(56.72) = −5.22, p < 0.01, but did not differ from the all-member condition, t(61.88) = −1.73, p = 0.52. In addition, the cooperation rates in the control condition and the all-member condition did not differ significantly between SVOs. However, in the selected-member condition, the cooperation rate of prosocials exceeded that of proselfs.

3.3 The effect of joining communication

We divided the selected-member condition participants into two groups, those who communicated and those who did not, and conducted the same analysis described in Section 3.2. In principle, the findings remained the same. The main effect of the condition was significant, F(3, 361.9) = 17.22, p < 0.01. According to the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test, the cooperation rate in the control condition was significantly lower compared to the other conditions. Furthermore, the cooperation rate of non-communicating members in the selected-member condition was significantly lower than those of communicating members in the selected-member condition and the all-member condition (|ts| > 3.08, p < 0.01). No significant difference was found between communicating members in the selected-member condition and the all-member condition, t(48.66) = −1.66, p = 0.35. We found neither the main effect of SVO, nor the interaction effect between the condition and SVO, Fs < 2.36, ps > 0.12.

As for the proselfs, the cooperation rate of non-communicating members in the selected-member condition did not differ significantly from that in the control condition, t(53.88) = −1.72, p = 0.68. It was lower than those of communicating members in the selected-member condition and in the all-member condition |ts| > 4.25, p < 0.01. As for the prosocials, the cooperation rate in the control condition was the lowest, |ts| > 3.67, p < 0.05. Additionally, non-communicating members cooperated less than communicating members in the selected-member condition, t(160.9) = −3.27, p < 0.05. However, the cooperation rate in the all-member condition did not differ significantly from those of non-communicating or communicating members in the selected-member condition, |ts| < 3.11, p > 0.05. These findings confirm that even if some members are not permitted to join the communication, non-communicating proselfs do not become less cooperative, while non-communicating prosocials become more cooperative than in the no-communication scenario.

3.4 Psychological factors behind the cooperative behaviors

We performed a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the scores of items related to goal sharing, reciprocity, and the other psychological factors introduced in Footnote 4, with the condition and SVO as the independent variables, to examine participants' perceptions of the experimental situation and the difference in their cooperation rate between the conditions (see Table 2B).

3.4.1 Sharing a common goal

The condition's main effect was significant for sharing a common goal, with and without the division of the selected-member condition participants into two groups: those who communicated and those who did not (Fs > 12.14, ps < 0.01). Participants in the all-member condition shared a goal to a greater extent than in the other conditions (|ts| > 4.01, ps < 0.01). The SVO's main effect was significant only when the selected-member condition participants were divided into the two groups (F = 4.43, p < 0.05). Namely, the prosocials exhibited a stronger sense of shared goals than the proselfs.

The interaction effect of the condition and SVO was not significant (Fs < 1.36, ps > 0.26). However, multiple comparisons revealed that both the proselfs and the prosocials in the all-member condition recognized sharing a common goal more strongly than in the control and selected-member conditions. When prosocials communicated in the selected-member condition, their recognition of goal sharing was higher than that of proselfs and did not differ from their recognition in the all-member condition. These outcomes suggest that the higher degree of sharing a common goal resulted in the highest cooperation rate in the all-member condition.

3.4.2 Reciprocity

As for reciprocity, the condition's main effect was not significant (|Fs| < 2.72, ps > 0.07), whereas SVO's main effect was significant (|Fs| > 14.44, ps < 0.01), with and without dividing the selected-member condition participants into the two groups. Notably, the proselfs were less likely to perceive reciprocity than the prosocials. The interaction effect of the condition and SVO was significant, F(2, 168) = 4.00, p < 0.05: the proselfs were less likely to perceive reciprocity than the prosocials in the control and selected-member conditions (|ts| > 3.00, ps < 0.01). Moreover, multiple comparisons revealed that participants in the selected-member condition were more likely to perceive reciprocal relations among group members than in the control condition, particularly those who communicated (|ts| > 2.29, ps < 0.05). Although the interaction effect was not significant when we divided the selected-member condition participants into two groups, F(3, 166) = 2.53, p = 0.06, multiple comparisons revealed that the proselfs in the all-member condition perceived reciprocity more strongly than in the control condition (t = −2.97, p < 0.01) and that the communicating prosocials in the selected-member condition perceived reciprocity more strongly than in the all-member condition (t = 2.00, p < 0.05).

A crucial finding was that non-communicating members did not decrease the perception of goal sharing and reciprocity compared with communicating members, which affirms the effectiveness of having communication among only some members. Considering only the effects of the conditions, goal-sharing perception was high in the all-member condition, whereas reciprocity perception was high in the selected-member condition. Therefore, the psychological effects that increased the cooperation rate may differ between these conditions.

3.4.3 Mediation analysis and moderated mediation analysis

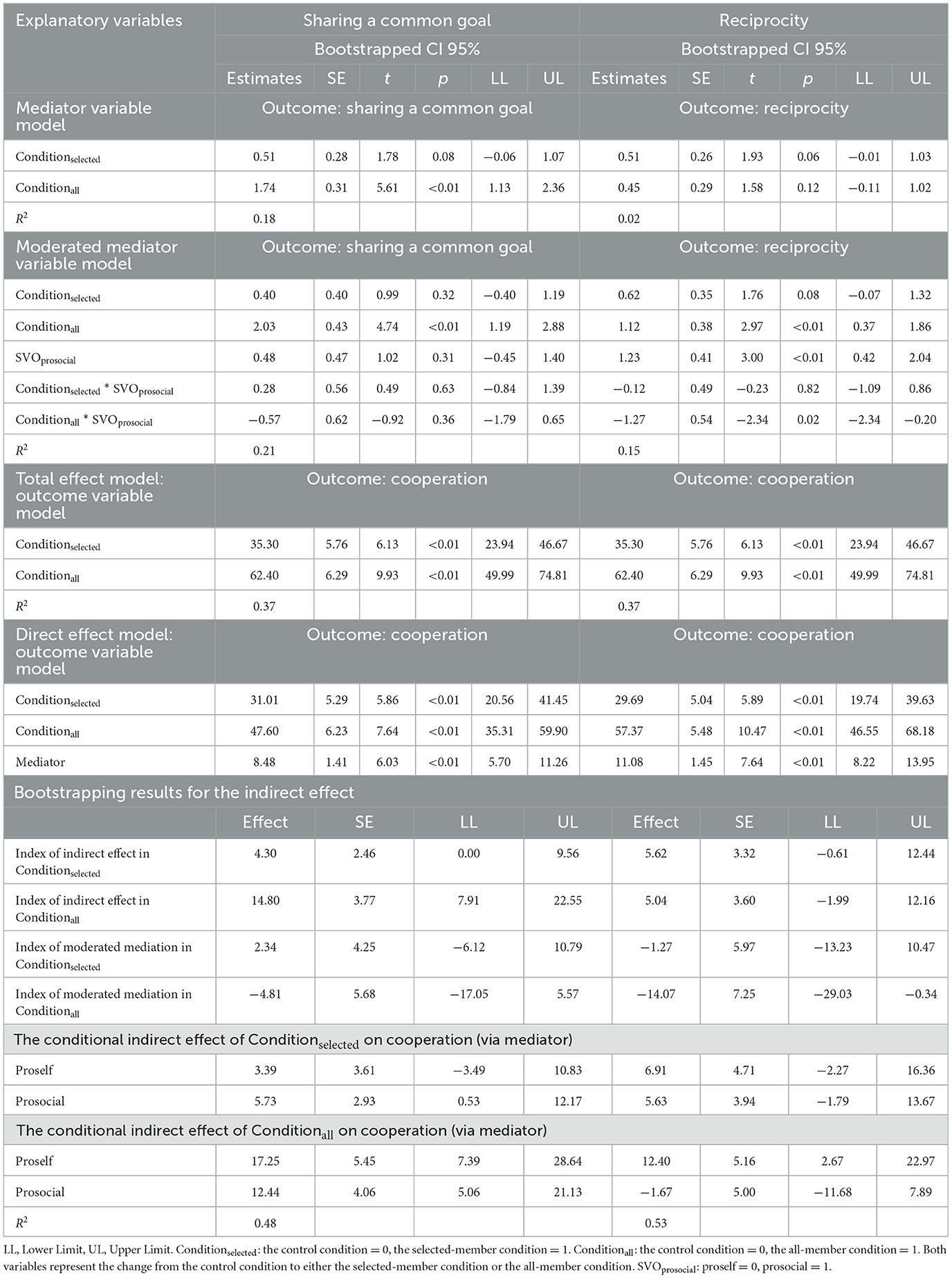

We conducted the mediation analysis using PROCESS model 4 (Hayes, 2013; Hayes and Preacher, 2014) with condition as the independent variable, average cooperation rate (periods 11–20) as the dependent variable, and goal sharing or reciprocity as the potential mediators. Indirect effects were estimated via bootstrapping (10,000 samples, 95% CI) following Preacher and Hayes (2004) (see Table 3).

Table 3. The mediation and moderated mediation effects of sharing a common goal and reciprocity on cooperation.

3.4.3.1 Sharing a common goal as a mediator

Regarding sharing a common goal, the direct effect of the condition on the cooperation rate was significant [the selected member condition B = 31.01, SE = 5.29, t = 5.86, p < 0.01, 95% CI (20.56, 41.45); the all-member condition B = 47.60, SE = 6.23, t = 7.64, p < 0.01, 95% CI (35.31, 59.90)], based on linear regression t-tests, and this relationship was significantly mediated by sharing a common goal in both the selected-member condition [indirect effect B = 4.30, SE = 2.46, 95% CI (0.00, 9.56)] and the all-member condition [indirect effect B = 14.80, SE = 3.77, 95% CI (7.91, 22.55)], indicating that the confidence interval did not include zero. In both conditions, it was demonstrated that communication enabled group members to share common goals and promoted cooperative behavior.

3.4.3.2 Reciprocity as a mediator

Regarding reciprocity, the direct effect of the condition on the cooperation rate was significant in both the selected-member condition [direct effect B = 29.69, SE = 5.04, t = 5.89, p < 0.01, 95% CI (19.74, 39.63)] and the all-member condition [direct effect B = 57.37, SE = 5.48, t = 10.47, p < 0.01, 95% CI (46.55, 68.18)]. Yet, the indirect effect via reciprocity was not significant in either condition [the selected-member condition B = 5.62, SE = 3.32, 95% CI (−0.61, 12.44); the all-member condition B = 5.04, SE = 3.60, 95% CI (−1.99, 12.16)].

Although reciprocity did not mediate the relationship between the condition and cooperation by itself, its mediation might be moderated by SVO, as the degree of reciprocity differed significantly between the SVO types. Thus, we conducted a linear moderated mediation analysis (Hayes, 2015). Regarding the all-member condition, we obtained a statistically significant interaction effect with SVO on reciprocity [B = −1.27, SE = 0.54, t = −2.34, p < 0.05, 95% CI (−2.34, −0.20)] and for the index of moderated mediation [index = −14.07, SE = 7.25, CI (−29.03, −0.34)]. Specifically, for proselfs, communicating with all group members increased cooperation rates through prompted perceptions of reciprocity [B = 12.40, SE = 5.16, CI (2.67, 22.97)], whereas this indirect effect was not significant for prosocials [B = −1.67, SE = 5.00, CI (−11.68, 7.89)]. In the selected-member condition, the interaction effect with SVO on reciprocity was not statistically significant [B = −0.12, SE = 0.49, t = −0.23, p = 0.82, 95% CI (−1.09, 0.86)].

3.4.4 Other psychological factors

We analyzed the other psychological factors introduced in Footnote 4. Whether or not to communicate, participants perceived to a large degree that talking with each other would enable mutual understanding (average of 4.91 on a 7-point scale). Nonetheless, they expected only to some degree that other group members would contribute to providing public goods (3.49 on average). They also expected, to a small degree, that the contribution would be equal among group members (2.57 on average). Participants did not fear a bad reputation for not contributing (2.77 on average).

Two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in the fairness of group members' allocation according to the SVO types (F = 3.94, p < 0.05) and the fear of a bad reputation between conditions (Fs > 5.61, ps < 0.01). Complete results are provided in the Supplementary materials; the following is the key findings. First, proselfs were less likely to perceive group members as equally cooperative than prosocials (t = −1.98, p < 0.05). Second, communication may cause participants to be concerned about their own reputation (|ts| > 2.37, ps < 0.05), especially for proselfs (|ts| > 2.05, ps < 0.05).

4 Discussion

This study examined the effect of communication among some group members on cooperation in a laboratory experiment concerning the provision of public goods. We showed that partial communication still enhances cooperation compared to no communication, although not as much as when all group members communicate. Moreover, even when some participants could not join the communication, they became more cooperative than when there was no communication. This tendency was clear for the prosocials. The proselfs were more sensitive about their participation in the communication process. When not participating in communication, the proselfs were less cooperative than when they joined. Nonetheless, their perception of goal sharing and reciprocity did not decrease compared to when communicated. These observations affirm that communication among some members is beneficial, even if assembling all the members is not always feasible.

Although we have revealed the positive effect of partial communication on cooperation, our experiment did not include any treatment that identified the conditions under which those who do not participate in communication would cooperate. Further analyses are required to identify the psychological processes by which partial communication elicits cooperation, involving social-environmental cues. Cues to likely future interaction embedded in shared social environments can foster cooperation (Gervais et al., 2013). Thus, prosocial participants might have become more cooperative when others communicated, even without joining the discussion themselves, as knowing others communicated could be a social-environmental cue. However, this possibility was not directly examined in this study. Another explanation for why communication increases cooperation is the norm generation (Kerr et al., 1997), especially social norms of promise-keeping (Bicchieri, 2002). Understanding interdependent relationships and sharing a common goal between agents generate social norms that allow achievements through collaborations (Tomasello, 2009). Future research should investigate further how communication generates social norms, its impact on psychological factors, and which aspects of communication are essential for cooperation.

Social scientists have sought viable solutions to social dilemmas, supporting that communication is one way to ensure cooperation. Generally, previous literature regarding communication, as well as our experiment, presumed a small-scale group. However, the scale of issues we are currently facing, such as climate change, has expanded to such an extent that it transcends group boundaries. Future research should investigate the impact of increasing the number of group members on cooperation when communication is limited.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Kochi University of Technology and Hokkaido University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Topic-Setting Program to Advance Cutting-Edge Humanities and Social Sciences Research (Responding to Real Society), Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Number 15654768), JSPS KAKEN (Grant Number 3K2234303).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Research Institute for Future Design, Kochi University of Technology, and the Center for Experimental Research in Social Sciences, Hokkaido University for providing experiment facilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frbhe.2025.1495995/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Such laboratory studies of relatively early ages include Deutsch (1958), Bixenstine et al. (1966), Caldwell (1976), Brechner (1977), Dawes et al. (1977), Edney and Harper (1978), Isaac and Walker (1988), Orbell et al. (1988), Ostrom and Walker (1991), and Kerr et al. (1997).

2. ^The effect of pre-play communication has also been studied in three-player coalition formation or bargaining games (e.g., Baron et al., 2017; Bolton et al., 2003). However, since there is no stage for contributing to the whole group's benefits, dividing resources among group members is the focus.

3. ^Based on Banerjee (2020), we have above 80% power to detect experimental effects, except for two specific comparisons regarding sharing a common goal: (1) between prosocials in the selected-member and the all-member conditions, and (2) between communicating proselfs and prosocials in the selected-member condition.

4. ^In the main text, we focus on sharing a common goal and perceiving reciprocity. The other items include the following: for the expectation of cooperation (two items), “other members will allocate coins to B” and “only some of group members will allocate coins to B” (reversed item) (α = 0.39); for fairness of group members' allocation (two items), “everyone in my group will allocate coins to B to the same extent” and “some members in my group will not allocate many coins to B” (reversed item) (α = 0.52); for fear of bad reputation (six items), “if I do not allocate coins to B, other members would think of me as a bad member (would resent me),” “I felt like allocating coins to A was a bad thing,” “I do not want the other members to think badly of me,” “I am worried about what the other members will think of me,” and “someone will know that I have made this choice” (α = 0.84); for effectiveness of discussion (two items), “if I talk with other members, we will be able to understand each other” and “nothing will change even if I talk with other members” (reversed item) (α = 0.76). We summarize the results regarding these items in Section 3.4.4.

References

Abbink, K., Dong, L., and Huang, L. (2018). “Talking behind your back: asymmetric communication in a three-person dilemma,” in CeDEx Discussion Paper 2018-11 [Nottingham: The University of Nottingham; Centre for Decision Research and Experimental Economics (CeDEx)]. Available online at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/200430/1/1032727179.pdf (Accessed October, 29 2025).

Aksoy, O., and Weesie, J. (2012). Beliefs about the social orientations of others: a parametric test of the triangle, false consensus, and cone hypotheses. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.009

Balliet, D. (2010). Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analytic review. J. Confl. Resolut. 54, 39–57. doi: 10.1177/0022002709352443

Banerjee, S. (2020). Sample sizes in experimental games. Res. Econ. 74, 221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.rie.2020.07.002

Baron, D. P., Bowen, T. R., and Nunnari, S. (2017). Durable coalitions and communication: public versus private negotiations. J. Public Econ. 156, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.09.002

Bicchieri, C. (2002). Covenants without swords: group identity, norms, and communication in social dilemmas. Ration. Soc. 14, 192–228. doi: 10.1177/1043463102014002003

Bixenstine, V. E., Levitt, C. A., and Wilson, K. V. (1966). Collaboration among six persons in a prisoner's dilemma game. J. Confl. Resolut. 10, 488–496. doi: 10.1177/002200276601000407

Bogaert, S., Boone, C., and Declerck, C. (2008). Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: a review and conceptual model. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 453–480. doi: 10.1348/014466607X244970

Bolton, G. E., Chatterjee, K., and McGinn, K. L. (2003). How communication links influence coalition bargaining: a laboratory investigation. Manag. Sci. 49, 583–598. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.49.5.583.15148

Bramoullé, Y., and Kranton, R. (2007). Public goods in networks. J. Econ. Theory 135, 478–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jet.2006.06.006

Braver, S. L., and Wilson, L. A. (1986). Choices in social dilemmas: effects of communication within subgroups. J. Confl. Resolut. 30, 51–62. doi: 10.1177/0022002786030001004

Brechner, K. C. (1977). An experimental analysis of social traps. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 13, 552–564. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(77)90054-3

Caldwell, M. D. (1976). Communication and sex effects in a five-person Prisoner's Dilemma Game. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 33, 273–280. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.33.3.273

Dawes, R. M. (1980). Social dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 31, 169–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.001125

Dawes, R. M., McTavish, J., and Shaklee, H. (1977). Behavior, communication, and assumptions about other people's behavior in a commons dilemma situation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 35, 1–11. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.1.1

Declerck, C. H., and Bogaert, S. (2008). Social value orientation: related to empathy and the ability to read the mind in the eyes. J. Soc. Psychol. 148, 711–726. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.148.6.711-726

Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. J. Confl. Resolut. 2, 265–279. doi: 10.1177/002200275800200401

Duguid, S., Wyman, E., Bullinger, A. F., Herfurth-Majstorovic, K., and Tomasello, M. (2014). Coordination strategies of chimpanzees and human children in a Stag Hunt game. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 281:20141973. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1973

Edney, J. J., and Harper, C. S. (1978). The effects of information in a resource management problem: a social trap analog. Hum. Ecol. 6, 387–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00889416

Eek, D., and Gärling, T. (2006). Prosocials prefer equal outcomes to maximizing joint outcomes. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 321–337. doi: 10.1348/014466605X52290

Erkut, H., and Reuben, E. (2023). Social networks and organizational helping behavior: experimental evidence from the helping game. Discussion paper SP II 2023-203, WZB Berlin Social Science Center. Available online at: https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2023/ii23-203.pdf (Accessed October 28, 2025).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., and Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 10, 171–178. doi: 10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4

Gervais, M. M., Kline, M., Ludmer, M., George, R., and Manson, J. H. (2013). The strategy of psychopathy: primary psychopathic traits predict defection on low-value relationships. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280:20122773. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2773

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav. Res. 50, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Hayes, A. F., and Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 67, 451–470. doi: 10.1111/bmsp.12028

Isaac, R. M., and Walker, J. M. (1988). Communication and free-riding behavior: the voluntary contribution mechanism. Econ. Inq. 26, 585–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1988.tb01519.x

Kanngiesser, P., Sunderarajan, J., Hafenbrädl, S., and Woike, J. K. (2024). Children sustain cooperation in a threshold public-goods game even when seeing others' outcomes. Psychol. Sci. 35, 1094–1107. doi: 10.1177/0956797624126785

Kerr, N. L., Garst, J., Lewandowski, D. A., and Harris, S. E. (1997). That still, small voice: commitment to cooperate as an internalized versus a social norm. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 23, 1300–1311. doi: 10.1177/01461672972312007

Kinukawa, S., Saijo, T., and Une, M. (2000). Partial communication in a voluntary-contribution-mechanism experiment. Pac. Econ. Rev. 5, 411–428. doi: 10.1111/1468-0106.00113

Ledyard, J. O. (1994). “Public goods: a survey of experimental research,” in The Handbook of Experimental Economics, eds. J. H. Kagel and A. E. Roth (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 111–194.

McClung, J. S., Placì, S., Bangerter, A., Clément, F., and Bshary, R. (2017). The language of cooperation: shared intentionality drives variation in helping as a function of group membership. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 284:20171682. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1682

Messick, D. M., and McClintock, C. G. (1968). Motivational bases of choice in experimental games. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 4, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(68)90046-2

Orbell, J. M., Van de Kragt, A. J., and Dawes, R. M. (1988). Explaining discussion-induced cooperation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 811–819. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.811

Ostrom, E., and Walker, J. (1991). “Communication in a commons: cooperation without external enforcement,” in Laboratory Research in Political Economy, ed. T. R. Palfrey (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press), 287–322.

Pletzer, J. L., Balliet, D., Joireman, J., Kuhlman, D. M., Voelpel, S. C., and Van Lange, P. A. M. (2018). Social value orientation, expectations, and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pers. 32, 62–83. doi: 10.1002/per.2139

Polzer, J. T., Milton, L. P., and Gruenfeld, D. H. (2001). Asymmetric subgroup communication in nested social dilemmas. Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 02-007. Available online at: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=12505 (Accessed October 23, 2025).

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36, 717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553

Pronin, K., and Woon, J. (2023). Does allowing private communication lead to less prosocial collective choice? Soc. Choice Welf. 60, 625–645. doi: 10.1007/s00355-022-01430-6

Pruitt, D. G., and Kimmel, M. J. (1977). Twenty years of experimental gaming: critique, synthesis, and suggestions for the future. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 28, 363–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.28.020177.002051

Rezaei, S., Rosenkranz, S., Weitzel, U., and Westbrock, B. (2024). Social preferences on networks. J. Public Econ. 234:105113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2024.105113

Sally, D. (1995). Conversation and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analysis of experiments from 1958 to 1992. Ration. Soc. 7, 58–92. doi: 10.1177/1043463195007001004

Schmitt, P., Swope, K., and Walker, J. (2000). Collective action with incomplete commitment: experimental evidence. South. Econ. J. 66, 829–854. doi: 10.1002/j.2325-8012.2000.tb00299.x

Van Kleef, G. A., and Van Lange, P. A. M. (2008). What other's disappointment may do to selfish people: emotion and social value orientation in a negotiation context. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 1084–1095. doi: 10.1177/0146167208318402

Van Lange, P. A. M. (1999). The pursuit of joint outcomes and equality in outcomes: an integrative model of social value orientation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 337–349. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.337

Van Lange, P. A. M., Bekkers, R., Schuyt, T. N. M., and Van Vugt, M. V. (2007). From games to giving: social value orientation predicts donations to noble causes. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 29, 375–384. doi: 10.1080/01973530701665223

Wit, A. P., and Kerr, N. L. (2002). “Me versus just us versus us all” categorization and cooperation in nested social dilemmas. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 616–637. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.616

Wyman, E., Rakoczy, H., and Tomasello, M. (2013). Non-verbal communication enables children's coordination in a ‘Stag Hunt' game. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 10, 597–610. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2012.726469

Keywords: common goal, communication, cooperation, public goods game, selected member, social dilemma, social value orientation

Citation: Kitakaji Y, Hizen Y and Ohnuma S (2025) Communication among selected members improves cooperation in a social dilemma. Front. Behav. Econ. 4:1495995. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2025.1495995

Received: 13 September 2024; Accepted: 14 October 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Emin Karagözoğlu, Bilkent University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Subrato Banerjee, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, IndiaHande Erkut, Social Science Research Center Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Kitakaji, Hizen and Ohnuma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yoko Kitakaji, a2l0YWthamlAaGlyb3NoaW1hLXUuYWMuanA=

Yoko Kitakaji

Yoko Kitakaji Yoichi Hizen

Yoichi Hizen Susumu Ohnuma

Susumu Ohnuma