- 1School of Environmental Design and Rural Development, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Geography Planning and Environment, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 3Independent Researcher, Winnipeg, MN, Canada

- 4Independent Researcher, Toronto, ON, Canada

Climate policies and plans can lead to disproportionate impacts and benefits across different kinds of communities, serving to reinforce, and even exacerbate existing structural inequities and injustices. This is the case in Canada where, we argue, climate policy and planning is reproducing settler-colonial relations, violating Indigenous rights, and systematically excluding Indigenous Peoples from policy making. We conducted a critical policy analysis on two climate plans in Canada: the Pan Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (Pan-Canadian Framework), a federal government-led, top-down plan for reducing emissions; and the Québec ZéN (zero émissions nette, or net-zero emissions) Roadmap, a province-wide, bottom-up energy transition plan developed by civil society and environmental groups in Quebec. Our analysis found that, despite aspirational references to Indigenous Peoples and their inclusion, both the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap failed to uphold the right to self-determination and to free, prior, and informed consent, conflicting with commitments to reconciliation and a “Nation-to-Nation” relationship. Recognizing these limitations, we identify six components for an Indigenous-led climate policy agenda. These not including clear calls to action that climate policy must: prioritize the land and emphasize the need to rebalance our relationships with Mother Earth; position Indigenous Nations as Nations with the inherent right to self-determination; prioritize Indigenous knowledge systems; and advance climate-solutions that are interconnected, interdependent, and multi-dimensional. While this supports the emerging literature on Indigenous-led climate solutions, we stress that these calls offer a starting point, but additional work led by Indigenous Peoples and Nations is required to breathe life into a true Indigenous-led climate policy.

Introduction

“In the introduction [to the ZéN Roadmap], they say ‘Indigenous people have warned us against this for centuries and environmentalists too'Ȇ Indigenous people haven't just been warning, they have been living it for decades. It is impacted their wellbeing, their health… we've surpassed this dangerous threshold in northern Canada. The way its painted in this Roadmap, it is like ‘oh in the possible distant future'. No, this is concrete. It's actually happening. It's actually taking place now” (E#6).

There is mounting support that Indigenous knowledge systems are key to combating the climate crisis (IPCC, 2014). Indeed, Indigenous Peoples have been sounding the “climate” alarm bells for several decades. Drawing on their Elders and knowledge keepers, as well as their reciprocal relationship with the natural world, Indigenous Peoples have been consistently raising their voices based on changing species migrations, water levels, and weather patterns, and, when necessary, putting their bodies and spirits on the line in the face of unrelenting extraction (Gedicks, 1994, 2001; Green and Raygorodetsky, 2010; Temper et al., 2020). Scientific evidence is now catching up: we are facing an obvious and rapidly accelerating global climate crisis. Global temperatures have increased by more than 1.1°C since the late-nineteenth century due to human influences on the climate system [Haustein et al., 2017; see also Environmental Change Institute (2013)]; at the current rate of warming, we could exceed 1.5°C in a little more than a decade, and 2°C by mid-century. A report released in April 2019 by Environment and Climate Change Canada, shows Canada is warming at twice the global rate, with the Canadian Arctic in particular warming at more than three times the global rate (Bush and Lemmen, 2019).

In light of this existential threat, a growing number of governments—federal, territorial, provincial, and municipal—are declaring climate emergencies, proposing new policies, and plans. The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (“Pan-Canadian Framework” or “PCF”) is one such plan: a beam of “sunny ways” creeping into Canadian climate policy following the election of a majority Justin Trudeau government. This period came to a grinding halt in 2018 when a federal House of Commons climate emergency declaration was immediately—coincidentally or serendipitously—followed by an announcement of the (re)approval of the Trans Mountain pipeline (a pipeline to transport bitumen oil from the Alberta tar sands to the British Columbia coast for export). Furthermore, it became evident that despite the policies contained with the Pan-Canadian Framework, Canada was at minimum 77 megatons from meeting its 2030 greenhouse gas target1—a target that was “highly insufficient” from the beginning, and “not remotely in line with the international community's goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C” (MacNeil, 2019, p. 156).

According to the 2019 United Nations Emission Gap report, emissions across the globe continue to rise at a pace that is inconsistent with a stable climate and current emissions pledges are not sufficient to limit warming to less than 3°C by 2100, let alone achieving the target temperature range of 1.5 to well-below 2°C of the Paris Agreement. As a result, severe climate impacts are being felt across the globe: wildfires, floods, droughts, and massive storms are already devastating lives, communities and ecosystems (Ripple et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2020). These impacts are only set to increase as global temperatures continue to rise, disproportionately impacting Indigenous Peoples given the unique climate risks as a result of how colonialism, in conjunction with capitalism, has shaped where they live, their socio-economic conditions, and how they exercise their relationships with Mother Earth (Whyte, 2017, 2018b). Clearly, it is “…therefore simply not rational for Indigenous [P]eoples to rely on these global, national, and regional economic and political frameworks for climate justice and a sustainable future” (McGregor et al., 2020, p. 36).

In lieu of this inaction, Indigenous Peoples have led, and continue to lead environmental and climate justice movements across the world (Gedicks, 1994, 2001; Gobby, 2020; Temper et al., 2020). For hundreds of years, they have generated and defended their relations and forms of social organization based on mutuality and reciprocity (Simpson, 2011; Coulthard, 2014). Recently, this has included advancing their own climate emergency declarations—declarations that emphasize the multidimensional, interconnected, and interrelated nature of climate solutions and that privilege the resurgence of Indigenous Peoples' sustainable self-determination. One such example is the Vuntut Gwitch'in First Nation (VGFN), in Old Crow, Yukon. Their declaration, entitled “Yeendoo Diinehdoo Ji' heezrit Nits'oo Ts' o' Nan He' aa,” translates into “After Our Time, How Will the World Be?” This declared that “climate change constitutes a state of emergency for our lands, waters, animals, and peoples.”

Indigenous climate policies, driven by fierce love for lands and waters and bolstered by inherent, treaty, constitutional, and international rights, emphasize the connection between colonialism and capitalism to understand, acknowledge and “challenge the unequal social and environmental relations in which carbon emissions are embedded” (Chatterton et al., 2013, p. 7). Scholars (Cameron, 2012; McGregor, 2018b) argue that those who fail to apply this analysis will be unable to understand the depth and scope of effects on Indigenous Peoples, and thus continue to fail. Indeed, the ongoing failure to address the climate crisis stems from a pervasive focus on the symptoms of the problem, rather than the root causes driving the crisis (Abson et al., 2017; Temper et al., 2018).

This study seeks to explore how climate policy can be more just, inclusive to Indigenous rights and knowledge systems, and more effective. We do this by analyzing two settler-developed climate plans in Canada—the Pan-Canadian Framework, a federal climate plan and the ZéN Roadmap, a provincial level, civil society led plan. More specifically, we ask whether these plans are: (a) in alignment or conflict with the governments' commitments to reconciliation and Nation to Nation relationships; (b) violating or respecting inherent, treaty, constitutional, and international Indigenous rights, and (c) centering or ignoring and erasing Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and approaches to climate mitigation and adaptation. Couched with an Indigenous Research Paradigm (IRP), we use a novel critical policy analysis based in sustainable self-determination, key-informant interviews, and our participant involvement in the development of the two policies (described in section Materials and Methods) to explore the inclusion, or more aptly exclusion of Indigenous Peoples and their rights, knowledge, and approaches, to climate action.

Our analysis found that, despite multiple references to Indigenous Peoples, both the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap failed to include Indigenous Nations and communities at the policy-making table. We argue that this exclusion constitutes a violation of Indigenous rights to self-determination and to free, prior and informed consent. In the case of the Pan-Canadian Framework, it is also in conflict with the federal government's commitments to reconciliation and advancing a Nation-to-Nation relationship. Further, the plans propose certain climate solutions—such as hydro-electric development and natural gas—that can disproportionately impact Indigenous Peoples. In these and other ways, we found that the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap ignore Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and approaches to climate mitigation and adaptation.

Based on these findings, we propose some key principles for Indigenous-led climate policy agenda going forward. These include clear calls to action that climate policy must: prioritize the land and emphasize the need to rebalance our relationships with Mother Earth; position Indigenous Nations not as stakeholders, but as Nations with the inherent right to self-determination; prioritize Indigenous knowledge systems; and advance climate-solutions that are interconnected, interdependent, and multi-dimensional. Through this, we hope to contribute to the growing amount of literature that supports the development of Indigenous-led climate solutions, which can, when done correctly, “generate well-being and Indigenous-determined futures in the face of dramatic environmental and climatic change” (McGregor et al., 2020, p. 37). To begin, we discuss the origins of the two climate policies and then introduce our methods. This is followed by our results and discussion.

Description of the Cases

Compared to Indigenous land defense, which has been ongoing since European contact, settler-led environmentalism is relatively new in Quebec and Canada (Hill, 2010; Simpson, 2017). To fully understand the implications of this new history, we chose to focus on two climate policies, one top-down led by the federal government, and the other bottom-up led by the civil society movement in Quebec, Canada. In this section, we provide an overview of both plans.

Overview of the Pan-Canadian Framework

Canada's current efforts to reduce GHG emissions and take action on climate change is encapsulated in the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change.2 The plan was released in 2016 at a First Minister's Meeting by the federal government—led by Justin Trudeau, eight provinces excluding Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and three territories. Touted as an important collaborative document, the Pan-Canadian Framework refers to itself as a “collective plan to grow our economy while reducing emissions and building resilience to adapt to a changing climate” (n.p.). The plan is intended to help meet Canada's emissions reduction target of 30% reduction in GHG emissions below 2005 levels by 2030—a target left over from the previous government led by Stephen Harper.

The plan, directed by the Vancouver Declaration, sought to capitalize on the momentum generated by the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement. It was developed by four working groups composed of federal, provincial, and territorial representatives: Pricing Carbon Pollution; Mitigation; Adaptation and Climate Resilience; and Clean Technology, Innovations, and Jobs. The Working Groups held roundtables and a multi-day stakeholder engagement event, processes which included national Indigenous organizations, stakeholders such as non-government organizations, think tanks, and industry associations including Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. These four groups laid the groundwork for the four pillars of the Pan-Canadian Framework: Pricing Carbon Pollution; Complementary Actions to Reduce Emissions; Adaptation and Climate Resilience; and Clean Technology, Innovations, and Jobs. Since the launch of the plan, the Federal Government has been issuing periodic status reports of the progress in implementing the plan, beginning in 2017 and most recently in 2019. During the course of writing this, the federal government introduced a “strengthened climate plan,” entitled A Healthy Environment and A Healthy Economy.

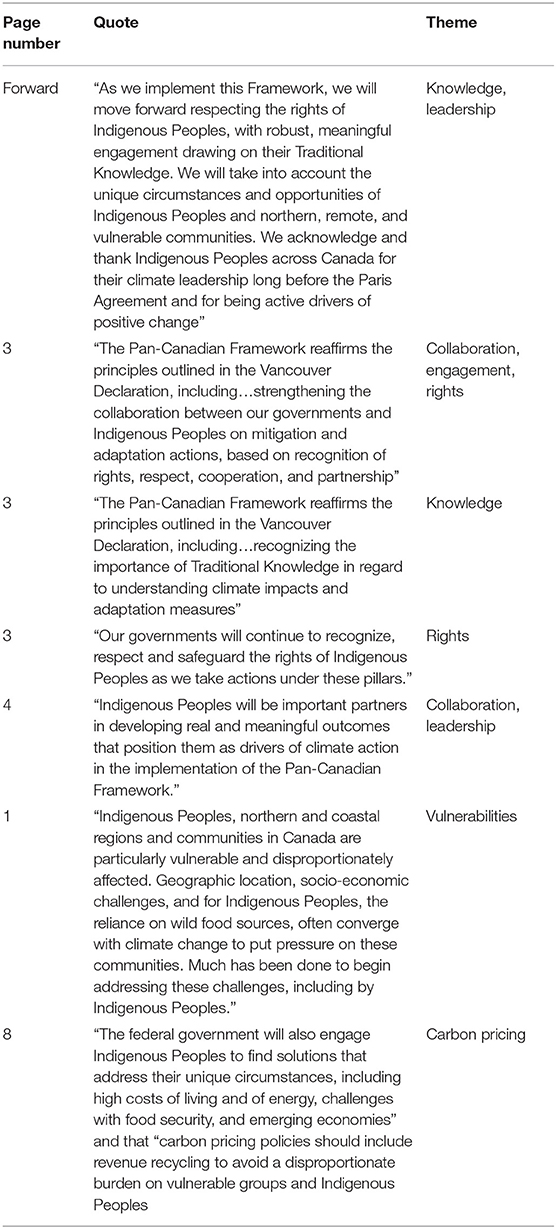

Table 1, presented below, provides a few examples of 83-times that “Indigenous” is referenced in the 78-page Pan-Canadian Framework (Lee, 2016).

Overview of the ZéN Roadmap

The Roadmap is a province-wide, bottom-up energy transition plan developed by civil society and environmental groups in Quebec to reach net zero emissions. It was led by with Le Front commun pour la transition énergétique3 (FTCE), a network of over 70 environmental organizations, unions, and community groups united toward a justice-based energy transition in Quebec.

The ZéN Roadmap lays out concrete steps “towards a Québec that will be carbon neutral, more resilient and more just” (p. 3). The first section of the document focused on building resilient communities, by reclaiming “our living environments and the means to protect the ecosystems on which we depend” (p. 5). The second section offers a political framework for guiding the transition which includes (a) call for the coherence and accountability of governments, (b) a fair transition whereby no one is left behind, (c) a focus from the start on human rights, and (d) immediate and extraordinary efforts to finance the transition. The final section lays out the plan for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, offering actions that work across sectors—around the themes of economy and consumption, energy, and land use planning and biodiversity. This section also offers actions specific to sectors including transportation, industries, buildings, agriculture, and waste.

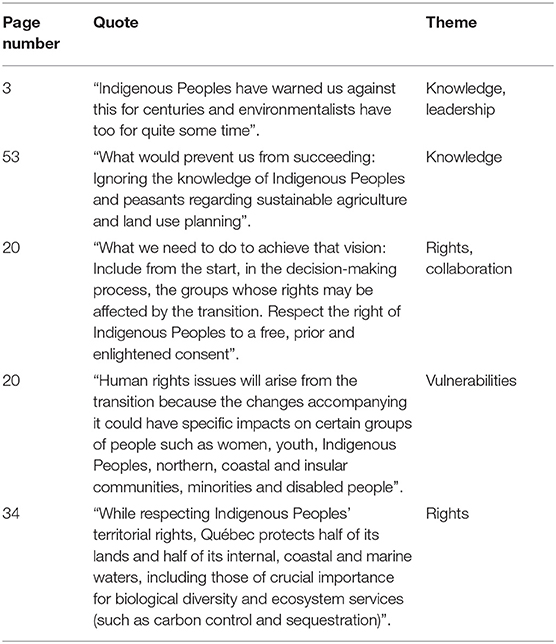

Table 2, provides a few examples of 15-times that the word “Indigenous” is referenced in the 64-page ZéN Roadmap.

Materials and Methods

“Some people need scientific data to understand that we should take action on climate change, and that's fine. Except that for us Indigenous people, it's something that's natural in us, respect for the land” (E#4).

To appropriately consider the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples within these two climate plans, we will base our analysis under the broad parameters of an IRP (Kuokkanen, 2000; Wilson, 2008). An IRP aims to empower Indigenous Peoples to drive research, shape ethical protocols, and define culturally relevant and accountable methodologies (Wilson, 2008; Kovach, 2010; Smith, 2012). It also seeks to decolonize the academy through the re-centering of research by, instead of on, Indigenous Peoples (Nakata et al., 2012; Smith, 2012). Following the recommendation of Nicoll (2004), we do this by refocusing the analytical and evaluative lens on “the innumerable ways in which white sovereignty circumscribes and mitigates the exercise of Indigenous sovereignty” (p. 19). By focusing on “being in” Indigenous sovereignty and considering the perspectives of Indigenous Peoples meaningfully, we challenge the dominant assumptions underlying colonial systems of climate “solutions” (Neville and Coulthard, 2019) and work to advance Indigenous climate futures in policy and practice. Through this, we work to simultaneously unsettle settler colonial present (Weiss, 2018).

To do this, we use sustainable self-determination as a critical conceptual lens to assess how each climate plan—the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap—considers Indigenous Peoples and their rights (Reed et al., 2020). Sustainable self-determination, a concept advanced by Cherokee scholar Jeff Corntassel, refers to both an individual and community-driven process that ensures “…indigenous livelihoods, food security, community governance, relationships to homelands and the natural world, and ceremonial life can be practiced today locally and regionally, thus enabling the transmission of these traditions and practices to future generations” (Corntassel, 2008, p. 156). An important component of such an approach is to de-center the state, and refocus the discussion on the cultural, social, and political mobilization of Indigenous Peoples (Corntassel, 2012). This approach aligns well with the Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA) Framework introduced by Hankivsky (2012) and Hankivsky and Jordan-Zachery (2019). This seeks to critique and develop policy in such ways as to contribute to transforming the inequitable relations of power that maintain inequality, as well as the complex contexts and root causes of the social problems that the given policies aim to address (Wiebe, 2019). We do this by focusing on different components of Indigenous self-determination, mainly inherent, Treaty, and constitutionally protected rights (Borrows, 2002; Mills, 2016); Indigenous Knowledge systems (McGregor, 2004, 2018a); and Indigenous participation (Littlechild, 2014).

Methods

We developed a critical policy analysis framework, based on the concept of sustainable self-determination to examine the various dimensions of each climate plan. This included considering the inherent, Treaty, and constitutionally protected nature of Indigenous rights, drawing on the section 35 of the Canadian Constitution and minimum standards affirmed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). To build on this rights framework, we considered the recommendations stemming from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), and Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls4. These recommendations offer important insights for understanding the root causes driving the climate crisis and the disproportionate impacts facing Indigenous Peoples.

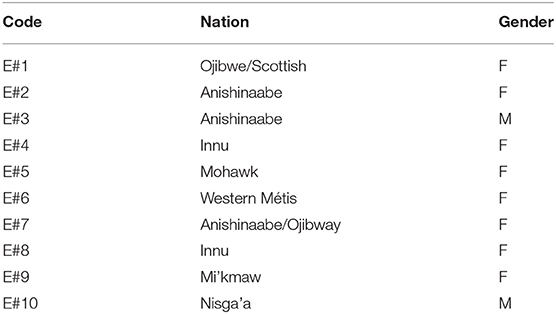

To learn more about the development of each policy document, including who was and was not invited to that policy-making table, we engaged in key-informant interviews and strategic partnerships with Indigenous-led organizations. For the Pan-Canadian Framework, we conducted a series of short telephone interviews with federal public servants involved in its creation. Based on their direction, we have kept each response anonymous. Future research, in partnership with Indigenous Climate Action, will be conducted with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people from across the country to develop Indigenous-led climate policy and plans. For the ZéN Roadmap, we also conducted a series of in-depth interviews with Indigenous Peoples living in and outside Quebec. These Experts came from different Indigenous nations and brought different experiences and knowledge related to climate change, policy, and planning. In advance of the interview, each individual was asked to read the ZéN Roadmap (version 1.0) and provide feedback, critical commentary, and recommendations through an interview with one co-author (JG), which was recorded and transcribed. All Experts were compensated for their time, and recommendations were then shared with the FCTE who wove the critiques and recommendations into the final, 2.0 version of the ZéN Roadmap which was released to the public in mid-November 2020. Direct quotes from these Experts are included below and cited as (E#), to indicate which Expert is being quoted. A table of all Expert interviews are provided in the Table 3 below provides a list of all Experts interviewed.

Beyond reflections on the literature and key-informant interviews, direct observation and engagement in the establishment of each climate plan also served to enrich our findings. In particular, one co-author (GR) participated in the design, negotiation, and implementation of the Pan-Canadian Framework, from 2016 to the present, working to advance First Nations rights, knowledge, and governance as a representative of a National Indigenous Organization. Another co-author (JG) was involved with the FCTE's process by gathering feedback from Indigenous people on the ZéN Roadmap and based on the feedback, revising it and drafting the 2.0 version. This process involved many meetings and negotiations.

Results/Discussion

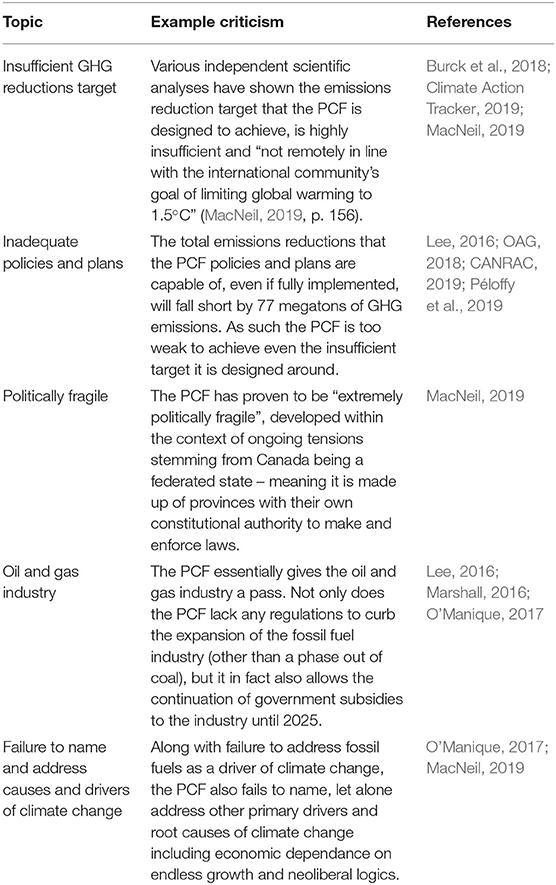

The Pan-Canadian Framework and ZéN Roadmap add to the unrelenting number of pledges, declarations, and policies promising ambitious greenhouse gas emission reductions. Like many of these, both exhibit, in different ways, a fundamental flaw in the current neoliberal approach to climate policy: no amount of “tweaking” of the current system will get us to an equitable and abundant model of prosperity for all of humankind (Klein, 2014). Too often do governments, businesses, and non-government organizations pour time, resources, and advocacy into this model of “tweaking,” where: “…[t]hey seek to escape the consequences of what [they] are doing, without changing what [they] are doing.” (Rodriguez Acha, 2019, p. 252). Many criticisms based on this line of thinking already exist for the Pan-Canadian Framework (see Table 4 presented below), however there has not been a systematic analysis from the perspective of Indigenous People, their rights, knowledge and approaches to climate action.

Table 4, presented below, provides an overview of existing critiques of the PCF.

In this section, we seek to advance these perspectives by drawing on our interviews and experience to ask whether each policy is: (a) in alignment or conflict with the governments' commitments to reconciliation and Nation to Nation relationships; (b) violating or respecting inherent, treaty, constitutional and international Indigenous rights; and (c) centering or ignoring Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and approaches to climate mitigation and adaptation. Based on this exploration, we close with a discussion of what an agenda for Indigenous-led climate policy would look like.

Do the Plans Align or Conflict With Commitments to Advance Reconciliation and “Nation-to-Nation” Relationships?

Since 2015, the Trudeau government has campaigned on a proposed “new” relationship with Indigenous Peoples. He regularly stated that: “[n]o relationship is more important to Canada than the relationship with Indigenous Peoples. Our Government is working together with Indigenous Peoples to build a nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, government-to-government relationship – one based on respect, partnership, and recognition of rights” (Office of the PMO, 2017).5

In both plans, there are limited references to the approach that was taken to engage Indigenous Nations on a “Nation-to-Nation” relationship. The Pan-Canadian Framework called for “robust engagement” with Indigenous Peoples on one hand, but on the other refused to include Indigenous representatives on the four working groups mandated to develop the plan's four pillars. Far from sematic, this removed Indigenous Peoples from the decision table and instead identified them as one of many groups to consult with. In doing this, Indigenous Peoples were positioned as stakeholders—a position that minimizes their ability to exercise their own self-determination and afford them little opportunity to participate as self-governing Nations (Alfred and Corntassel, 2005; Von der Porten et al., 2015).

For the ZéN Roadmap, the organizing group was not able to reach Indigenous Peoples in Quebec and instead continued to draft the entire report themselves. Once the report was drafted, they then asked a co-author (JG) to conduct a consultation with Indigenous Peoples. Unfortunately, this is a common trend in the mainstream environmental organizing as described by one Expert: “This methodology of ‘we're having a project and we have in the back of our minds that it needs to be inclusive … but we don't really know how to do it. We haven't built those relationships prior. So now we're still moving forward with the project because we're on a timeline … oh and we need to Indigenize the document now that it's already produced'. This is kind of backward. There needs to be an explicit commitment because otherwise there's always the excuse” (E#9).

Much of the wording regarding Indigenous Peoples in the two plans are aspirational, with words such as “should,” “the need for,” “will find solutions,” but no wording is included that commits to any of these, or no indication that these efforts have been commenced thus far. One such example is the usage of the phrase “unique circumstances” in the Pan-Canadian Framework to refer to the multiple and urgent crises facing Indigenous Peoples across Canada. Through choice of language, this reduces these crises to “unique circumstances” while falsely promoting a peaceful and respectful relationship. This diminishes and negates ongoing Indigenous claims for justice, furthering division and distrust between Indigenous Peoples and the state—a state that continues to place Indigenous Peoples systemically and actively in a vulnerable position through ongoing colonial relations, land dispossession and failure to take meaningful action on climate change (O'Manique, 2017).

Do the Plans Violate or Respect Inherent, Treaty, Constitutional, and International Indigenous Rights?

“[It's not] truly showcasing Indigenous world views and knowledge. It's more. like making sure it's there because now it's not politically acceptable anymore to not have it there. People are mindful to make sure that its mentioned and that's already a first step. But that doesn't mean that the education to fully understand about what it means to actually respect [Indigenous rights]” (E#9).

Indigenous rights are mentioned six times in the Pan-Canadian Framework. One of these references includes the UNDRIP, including the right to “free, prior and informed consent” (FPIC), which Canada signed on to as a “full supporter without qualification6” in 2016, the same year the PCF was released. Despite the mention of UNDRIP, other affirmations of Indigenous rights, such as inherent, treaty, and constitutional rights were not mentioned at all.

In the ZéN Roadmap, there was limited reference to the UNDRIP: a fact highlighted by one Expert: “Naming all human rights declarations - civil, political,… but they don't mention UNDRIP until much later. And they just throw it in there. UNDRIP should be included in the first paragraph. It's fundamental to protecting our country against climate change.” They go on to provide an example of its importance: “… when deciding whether to accept or reject industrial infrastructure projects. This has been done for decades - the disregard of human rights has given them the ability to create climate change. Because it's only because they disrespected human rights that they were able to impose that massive infrastructure'” (E#6). Free, prior, and informed consent was repeatedly highlighted by all Indigenous Experts as an important guide for interactions between local, provincial, territorial, and national governments and Indigenous Peoples.

Pushing this one step further, neither plan discussed the right to self-determination: a right that is affirmed in the UN Declaration and provides Indigenous Peoples with the ability to “…freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development” (United Nations, 2007, p. 4). This is not entirely surprising, as for many states, there is fear that the advancement of Indigenous Peoples' self-determination corresponds to a loss of sovereignty or territorial integrity (Lightfoot and MacDonald, 2017). An Expert made this connection quite clear to climate: “Indigenous sovereignty is really at the heart of this issue. The right to “protect the land” should be enshrined in the philosophy of this transition. Water is life. Water is sacred. The land is sacred” (E#7). Expanding this further, a co-author (JG) in the meetings to revise the ZéN Roadmap observed significant resistance from within the FTCE—in particular the Industry unions and Quebec nationalists—to acknowledge Indigenous Peoples' right to self-determination.

At its core, both plans reference Indigenous rights repeatedly, but Indigenous rights appear to have had no influence on the actual policies and plans developed. An Expert captured this in her intervention: “A lot of the time, there is no inclusion for First Nations when it comes to [decision-making about] things that are being extracted from land and waters” (E#2). Such an approach aligns well with the “politics of recognition” introduced by Dene scholar, Coulthard (2014), used by Canada and the provinces to “…reproduce the very configurations of colonial power that Indigenous peoples' demands for recognition have historically sought to transcend” (p. 52). Asch et al. (2018) further this consideration: “…[r]ecognition can be a Trojan horse-like gift: state action often operates to overpower or deflect Indigenous resurgence” (p. 5). One Expert put it quite eloquently: “In my opinion the way this is structured we're absolutely not reframing relationship with indigenous people and its not a decolonized exercise. Not only in the methodology that was put in place but definitely as well in the content that is presented” (E#9). During the ZéN Roadmap process, an Expert echoed this observation: “Indigenous rights are ‘acknowledged' rather than integrated into the functioning of law and society. There is a missed opportunity here to discuss land rights specifically, as well as jurisdiction” (E#10).

Do the Plans Center or Ignore Indigenous Perspectives, Knowledge, and Approaches to Climate Mitigation and Adaptation?

“Some people need scientific data to understand that we should take action on climate change, and that's fine. Except that for us Indigenous people, it's something that's natural in us, respect for the land” (E#4).

While both plans acknowledge the role of Indigenous Peoples in addressing climate change, neither included Indigenous Peoples in the design of the climate plan. For instance, the ZéN Roadmap only engaged Indigenous Peoples after the first version of the report was completed. The result of this oversight is that the plans reflect a western, reductionist worldview, whereby elements of the plan are not holistically integrated into others, but instead framed in isolation from each other. The Pan-Canadian Framework, for example, seems to break up the climate problem into four “pillars,” overlooking how these pillars are interconnected to one another.

This approach aligns with the explanation of Behn and Bakker (2019), where the solutions to climate and environmental problems are rendered technical, attempting to de-politicize the issue and focus on the technological arrangements required to solve them. For Indigenous Peoples, it is the opposite, as one Expert highlighted that there is “too much disconnection between points … We talk about resilient communities but we're separating that from education and social dialogue … having these separate spheres. We need to break the sphere and we need to realize the interconnectivity of everything” (E#6). Behn and Bakker (2019) call this interconnectivity, “rendering sacred” as a way to discuss how relationships with land are perceived and acted upon.

As a result, it is clear that there was no critical interrogation of the limitations of settler ways of knowing and unwillingness to look to other ways of knowing, reproducing epistemological violence (Dugassa, 2008). As one Expert told us: “I think the whole narrative would have been different with knowledge keepers involved, really passing on how they engage with the land and how they honour that relationship” (E#9). Indeed, this cursory consideration of Indigenous knowledge often minimizes Indigenous values and concerns to be framed in terms of what can be “conveniently appropriated” from Indigenous knowledge (Littlechild, 2014). This reductionist approach simplifies the conceptualization of Indigenous knowledge to “data” to try to fit within existing hierarchical and colonial structures (Nadasdy, 2010).

Among other actions, the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN do this by framing the climate problem as exclusively about reducing greenhouse gas emissions, rather than addressing the root causes of the crisis. An Expert spoke to this oversight in climate policy more generally: “There's a common tendency for climate related conversations to do the same thing that they've always done - which is like either focus on mitigation, focus on adaptation without providing some form of intersectional lens on those two broad categories. This kind of misses the point of how we're thinking about climate as a multiplier of these existing realities and vulnerabilities.” They go on to discuss how climate policies needs to “…remove that separation of climate action and people's everyday lives. and so, thinking about how do we address all of these intersecting vulnerabilities and structural factors that many people face but other folks capitalize on” (E#3).

Another Expert echoed this sentiment by calling out the language contained with the Framework: “…the framework and the narrative and the language is still very western7#x02026; still us and the land as separate and not that we're actually part of that system, that we're related to the land” (E#9)” Clearly, although both the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap reference Indigenous knowledge and perspectives to addressing the climate crisis, neither of them actually incorporate these perspectives meaningfully. The result is that both plans ignore Indigenous leadership, knowledge systems, and perspectives in their approaches to climate mitigation and adaptation.

Toward an Agenda for Indigenous-Led Climate Policy

Our analysis shows that, despite references to Indigenous Peoples, both the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap conflict with their commitments to reconciliation and the advancement of a Nation-to-Nation relationship; disrespects, and in some cases violates, the inherent, Treaty, and constitutionally-protected rights of Indigenous Peoples; and largely ignores Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and approaches to climate mitigation and adaptation. While this not entirely surprising, given the Government's tendency to: “…introduce half-measures as a cover for the uninterrupted extraction and transportation of gas, coal, and oil” (Foran et al., 2019, p. 223), it does confirm that little meaningful progress has been made to address colonialism, reduce the disproportionate climate impacts on Indigenous Nations, and advance Indigenous-led solutions (Cameron, 2012; Maldonado et al., 2013). A similar lack of progress has occurred in the United States, as Indigenous scholars and allies document in the Indigenous-led chapter of the National Climate Assessment (Maldonado et al., 2013; Bennett et al., 2014).

In this light, it is clear that the only way to address the simultaneous three “c”s driving catastrophic climate change—capitalism, colonization, and (de)carbonization—is for Indigenous Nations to “…take matters into their own hands” (Ladner and Dick, 2008, p. 89). One expert called for a deep questioning and deconstruction of the “capitalist concept of property” as a necessary part of effective climate plans and policy (E#8). Another expert made clear that “to [address the climate crisis] we need to change the system at its base, political, capitalist, corporations, banks, all of them… Its not just the government…. the government has little control over corporations. Quit asking the government, he has no power, he's just a puppet on a string” (E#1) Indeed, Hayden King and Shiri Pasternak highlight this eventuality: “we also have to acknowledge that solutions might have to be realized outside of state processes. In fact, they may be more conducive to asserting alternative futures for life on this planet” (Pasternak et al., 2019, p. 12). To do this, we return to our Experts to begin outlining an Indigenous-led climate agenda that seeks to dismantle settler colonialism, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy simultaneously (Whyte, 2018a). Such lessons could be applied for informing climate policy more broadly, especially as international organizations such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, increasingly recognize the role of Indigenous Peoples and their ways of knowing in climate discourse (IPCC, 2018).

Climate Policy Must Prioritize the Land and Emphasize the Need to Rebalance our Relationships With Mother Earth

The restoration of balance to the relationships between humans and nature, as well as between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown are intimately linked to another (Borrows, 2017). In a climate context, these connections are rarely discussed, which in Indigenous thought is preposterous. Truly transformative climate action can only be attained when “…they are based on the gift-reciprocity relationship of interdependency and mutual aid learning from Mother Earth” (Tully, 2017: p. 116). One expert pointed this out clearly: “I don't think we can trust government to truly protect the land. Ever. This ties into the idea of teaching and re-education of people. If people accept a philosophy of the land and waters being sacred and understand the beauty and importance of the natural world, they become protectors. I think this is what you mean when you say, “our relationship with the ecosystems where we live must be revisited in depth” (E#7). The restoration of balance is central to advancing Indigenous climate futures.

Indigenous Nations Must Be Positioned as Nations That Have an Inherent Right to Self-Determination

Throughout the analysis of the two climate plans, it was evident that governments, civil society, and industry associations were unwilling to acknowledge the true role of Indigenous Nations in the founding of Canada. Several Experts highlighted this role quite clearly: “Personally, I see Indigenous Nations as sovereign. And as equivalent to the provincial and federal jurisdictions. So just recognizing that sovereignty. And when they say we want [an energy transition], let the Indigenous Nations decide. We have councils. There are governing bodies. They should have a seat at the table. That would help. That's decolonial. Create and leave room for new perceptions and new people to sit at the table. And not fight them” (E#6). Another called on the inclusion of wording that explicitly recognizes the role of renewing historic agreements and treaties made with First Nations, recognizing that:“the first treaties [provided guidance] of how to be mindful, of how we use to land, in order to think about the next seven generations for example” (E#2). Decolonial climate policy requires the exercise of self-determination by Indigenous Nations.

Indigenous Nations, Peoples, and Representative Organizations Must Be Positioned as Leaders With Direct Decision-Making

While there was acknowledgment of the role of Indigenous Peoples climate leadership, it was not meaningfully incorporated in the design of climate solutions. This is a missed opportunity, as one Expert spoke to this quite clearly, highlighting that Indigenous Peoples have had “…thousands of years about adaptations and thousands of years of knowledge [about the land]. Just acknowledgement that… and perhaps that the colonial project attempted to erode that. And that the resiliency [of Indigenous communities] as a reflection of being able to survive despite colonization” (E#3). This includes those that continue to stand up in resistance against the capitalist mode of production and the logics of domination that maintain the structure of settler colonialism (Wolfe, 2006). Land and water protectors must be not only compensated for their contribution, but also should be considered as actively contributing to Canada's climate mitigation aspirations. While this is out of the scope for this paper, a future paper exploring this concept—the contributions of land protectors to mitigation—is much needed.

Prioritize Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Make Space for the Equal Consideration of Diverse Knowledge Systems

While not completely in the scope of this paper, it was clear that there is a deep ontological disjuncture between mainstream climate solutions and those that would be advanced by Indigenous Peoples. Indeed, one Expert pointed this out clearly: “I think the whole narrative would have been different with knowledge keepers involved, really passing on how they engage with the land and how they honour that relationship” (E#9). Not only is this central to working with Indigenous Peoples, but it is also important when within an IRP. Frameworks for the ethical treatment of Indigenous knowledge systems are well-known—Two-Eyed Seeing, Walking on Two Legs, Ethical Space, among many others—and must be integrated into climate policy moving forward.

Reflect the Diversity of Indigenous Nations

In the two climate policies, there was zero discussion of the diversity of Indigenous Nations, creating the impression of a homogenous reality across Turtle Island. This aligned with what one Expert pointed out: “I feel like indigenous people are just kind of thrown in there … they're not necessarily all at the same.… Some Indigenous communities are doing very well. To just kind of homogenize all of them into one big clump and say you are all disenfranchised. It's not really representative of the reality” (E#6). Continuing this train of thought, another Expert highlighted the importance of recognizing the role of urban Indigenous Peoples, who: “…[are] over 60% of indigenous people are not living in their communities or are extremely mobile, they still hold the level the knowledge. They should still be recognized and acknowledged” (E#9). Extending this one step further, several Experts spoke to the importance of uplifting the voices of those structurally oppressed groups that must be involved in the development of climate solutions. One example to address this was proposed to highlight the root cause of the climate crisis: “…say patriarchy, capitalism, colonization have created and imposed certain policies [that are driving these inequities] … But there are a lot of very strong racialized communities. Climate migrants and refugees are very strong …” (E#6).

Advance Climate-Solutions That Are Interconnected, Interdependent, and Multi-Dimensional to Simultaneously Advance Decarbonization and Decolonization

Many of the solutions proposed by the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap completely disregard the interconnectedness between proposed policies presented in different sections of the Plans. One clear example in the ZéN Roadmap is the proposal to eliminate single use plastic. This proposal wholly ignores the realities that many Indigenous Peoples still lack clean drinking water. Solutions must seek to address these systemic inequalities, and the ongoing legacy of settler colonization. One Expert proposed this approach instead: “‘We're going to eliminate plastic bottles, but first, we're going to make sure that everybody has drinking water and access to services and then they don't need to use plastic bottles'. There should be a proposed action to make sure that [all communities] have the essential services necessary to have that fair transition. Not just Indigenous communities but also other vulnerable communities like low-income communities and communities of color that are disproportionately not receiving the same services as others” (E#6). Another example highlighted the tendency to overlook the disproportionate impact of large-scale hydroelectric and natural gas development on Indigenous Peoples and their territories, notably in Quebec: “…vast areas were flooded, people were displaced, wildlife was impacted, and the land upon which they relied, and their ways of life were permanently altered. This is an ‘out of sight, out of mind' consequence in Quebec's claim to green energy” (E#5).

Conclusion

Drawing on a novel critical policy analysis based in sustainable self-determination, key-informant interviews, and our participant involvement, we critically analyzed two settler-developed climate policies—the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN Roadmap, a civil society-led plan in Quebec, Canada. Each conflicted with the aspirations of reconciliation, disrespected inherent, treaty, constitutional and international Indigenous rights, and largely ignored Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and approaches to climate mitigation and adaptation. In light of this failure—and the growing failure of mainstream climate policy to address the climate crisis—we drew on our Experts to propose six potential components of an Indigenous-led climate agenda. Lessons from this Indigenous-led climate agenda can support the aspirations of Indigenous Peoples across Turtle Island, as well as around the world, as they increasingly reassert their role in climate action.

We stress that this is only a starting point, and deep and meaningful engagement with Indigenous Peoples and Nations is required to breathe life into these components in a way that reflects each Nations' individual history, culture, jurisdiction and legal systems. These considerations are central to the development of Indigenous climate futures that not only support, but advance the flourishing of future generations (Wildcat, 2010; Whyte, 2017). An approach that is particularly relevant as Canada contemplates the implementation of its “strengthened” climate plan. Taking a page for Leanne Simpson, in doing this, we recognize that it is not enough to hypothesize futures without concrete action instead our futures are “…entirely dependent upon what we collectively do now as diverse Indigenous nations, with our Ancestors and those yet unborn” (Simpson, 2017, p. 246, emphasis added).

Data Availability Statement

Due to respecting research ethics protocols and respecting confidentiality agreements with Experts interviewed, raw data will not be made available by authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Dr. Richard DeMont, Chair, University Human Research Ethics Committee, Concordia University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JG conducted interviews with experts. JG, GR, RS, and RI conducted policy analysis on the PCF. HM provided expertise on climate science. GR and RS provided expertise on Indigenous Knowledge and Indigenous approaches to climate policy. The writing of the article was led by GR and JG. RI and HM provided editing support. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

GR was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada and the University of Guelph through an Indigenous Graduate Scholarship. JG was supported by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to also acknowledge the invaluable insight of the 10 Indigenous Experts consulted. They have enriched and shaped this analysis immeasurably.

Footnotes

1. ^https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/br4_final_en.pdf, page 27.

2. ^http://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/eccc/En4-294-2016-eng.pdf

3. ^https://www.pourlatransitionenergetique.org/qui-sommes-nous/

4. ^https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/

5. ^https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/statements/2017/06/21/statement-prime-minister-canada-national-aboriginal-day

References

Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., et al. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46, 30–39. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Alfred, T., and Corntassel, J. (2005). Being indigenous: resurgences against contemporary colonialism. Govern. Oppos. 40, 597–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2005.00166.x

Asch, M., Borrows, J., and Tully, J., (eds.). (2018). Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. doi: 10.3138/9781487519926

Behn, C., and Bakker, K. (2019). Rendering technical, rendering sacred: the politics of hydroelectric development on British Columbia's Saaghii Naachii/Peace River. Glob. Environ. Polit. 19, 98–119. doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00518

Bennett, T. M. B., Maynard, N. G., Cochran, P., Gough, R., Lynn, K., Maldonado, J., et al. (2014). “Ch. 12: Indigenous peoples, lands, and resources,” Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, eds J. M. Melillo, T. C. Richmond, and G. W. Yohe (Washington, DC: U.S. Global Change Research Program), 297–317 doi: 10.7930/J09G5JR1

Borrows, J. (2002). Recovering Canada: The Resurgence of Indigenous Law. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Borrows, J. (2017). “Earth-bound: Indigenous resurgence and environmental reconciliation,” in Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings, eds M. Asch, J. Borrows, and J. Tully (University of Toronto Press), 49–82.

Burck, J., Marten, F., Höhne, N., and Hmaidan, W. (2018). G20 Edition: Climate Change Performance Index 2017. Germanwatch eV. Available online at: https://germanwatch.org/en/14016 (accessed October 22, 2020).

Bush, E., and Lemmen, D. S., (eds.). (2019). Cana-da's Changing Climate Report. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, 444. Available online at: https://changingclimate.ca/CCCR2019/

Cameron, E. S. (2012). Securing Indigenous politics: a critique of the vulnerability and adaptation approach to the human dimensions of climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Glob. Environ. Change. 22, 103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.11.004

CANRAC (2019). Getting Real About Canada's Climate Plan. Available online at: https://climateactionnetwork.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CAN-RAC_ClimatePlanExpectations_EN-1.pdf (accessed January 25, 2020).

Chatterton, P., Featherstone, D., and Routledge, P. (2013). Articulating climate justice in copenhagen: antagonism, the commons, and solidarity. Antipode 45, 602–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01025.x

Climate Action Tracker (2019). Climate Action Tracker, Canada. Available online at: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/canada/ (accessed July 11, 2020).

Corntassel, J. (2008). Toward sustainable self-determination: rethinking the contemporary indigenous-rights discourse. Alternatives 33, 105–132. doi: 10.1177/030437540803300106

Corntassel, J. (2012). Re-envisioning resurgence: indigenous pathways to decolonization and sustainable self-determination. Decolon. Indigen. Educ. Soc. 1, 86–101. Available online at: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18627/15550 (accessed July 22, 2021).

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. doi: 10.5749/minnesota/9780816679645.001.0001

Dugassa, B. F. (2008). Indigenous Knowledge, Colonialism and Epistemological Violence: The Experience of the Oromo People under Abyssinian Colonial Rule. Ph.D. dissertation. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

Environmental Change Institute (2013). Human-Induced Warming: +1.1687753°C. Available online at: http://globalwarmingindex.org (accessed November 10, 2020).

Foran, J., Grosse, C., and Hornick, B. (2019). “Frontlines, intersections and creativity: the growth of the North American Climate justice movement,” in Climate Futures: Re-Imagining Global Climate Justice, eds K. K. Bhavnani, J. Foran, P. A. Kurian, and D. Munshi (London: Zed Books Ltd.) p. 222–245.

Gedicks, A. (1994). The New Resource Wars: Native and Environmental Struggles Against Multinational Corporations. Montreal, QC: Black Rose Books Ltd.

Gedicks, A. (2001). Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Gobby, J. (2020). More Powerful Together: Conversations with Climate Activists and Indigenous Land Defenders. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Press.

Green, D., and Raygorodetsky, G. (2010). Indigenous knowledge of a changing climate. Clim. Change 100, 239–242. doi: 10.1007/s10584-010-9804-y

Hankivsky, O., (ed.). (2012). An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework. Vancouver: BC: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University.

Hankivsky, O., and Jordan-Zachery, J. S., (eds.). (2019). The Palgrave Handbook of Intersectionality in Public Policy. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-98473-5

Haustein, K., Allen, M. R., Forster, P. M., Otto, F. E. L., Mitchell, D. M., Matthews, H. D., et al. (2017). A real-time global warming index. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14828-5

IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf (accessed on March 24, 2019).

IPCC (2018). 2018: Summary for Policymakers. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/ (accessed on April 11, 2020).

Klein, N. (2014). This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Kovach, M. (2010). Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Kuokkanen, R. (2000). Towards an “Indigenous paradigm” from a Sami perspective. Can. J. Native Stud. 20, 411–436. Available online at: http://www3.brandonu.ca/cjns/20.2/cjnsv20no1_pg411-436.pdf (accessed July 22, 2021).

Ladner, K. L., and Dick, C. (2008). Out of the fires of hell: globalization as a solution to Globalization—an indigenist perspective. Canad. J. Law Soc. 23, 63–91. doi: 10.1017/S0829320100009583

Lee, M. (2016). A Critical Guide to the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. Available online at: https://www.policynote.ca/a-critical-guide-to-the-pan-canadian-framework-on-clean-growth-and-climate-change/ (accessed July 5, 2020).

Lightfoot, S. R., and MacDonald, D. (2017). Treaty relations between indigenous peoples: Advancing global understandings of self-determination. New Divers. 19, 25–39. Available online at: http://newdiversities.mmg.mpg.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2017_19-02_NewDiversities-1.pdf#page=27 (accessed July 22, 2021).

Littlechild, D. B. (2014). Transformation and re-formation: First Nations and water in Canada. Master of Laws Dissertation, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC. Available online at: https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/bitstream/handle/1828/5826/Littlechild_Danika_LLM_2014.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (accessed September 13, 2020).

MacNeil, R. (2019). Thirty Years of Failure: Understanding Canadian Climate Policy. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

Maldonado, J. K., Shearer, C., Bronen, R., Peterson, K., and Lazrus, H. (2013). “The impact of climate change on tribal communities in the US: displacement, relocation, and human rights,” in Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples in the United States, eds J. Koppel Maldonado, B. Colombi, and R. Pandya (Cham: Springer), 93–106. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05266-3_8

Marshall, D. (2016). The Pan-Canadian Climate Framework: Historic and Insufficient. Available online at: https://environmentaldefence.ca/2016/12/15/pan-canadian-climate-framework-historic-insufficient/ (accessed June 29, 2020).

McGregor, D. (2004). Coming full circle: indigenous knowledge, environment, and our future. Am. Ind. Quar. 28, 385–410. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2004.0101

McGregor, D. (2018a). Indigenous environmental justice, knowledge, and law. Kalfou 5:279. doi: 10.15367/kf.v5i2.213

McGregor, D. (2018b). Mino-mnaamodzawin: achieving indigenous environmental justice in Canada. Environ. Soc. 9, 7–24. doi: 10.3167/ares.2018.090102

McGregor, D., Sritharan, M., and Whitaker, S. (2020). Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 43,35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.007

Mills, A. (2016). The lifeworlds of law: on revitalizing Indigenous legal orders today. McGill Law J. 61, 847–884. doi: 10.7202/1038490ar

Nadasdy, P. (2010). “Adaptive co-management and the gospel of resilience,” in Adaptive Co-management: Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-Level Governance, eds D. Armitage, F. Berkes, and N. Doubleday (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press), 208–227.

Nakata, M., Nakata, V., Keech, S., and Bolt, R. (2012). Decolonial goals and pedagogies for indigenous studies. Decolon. Indig. Educ. Soc. 1, 120–140. Available online at: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18628 (accessed July 22, 2021).

Neville, K. J., and Coulthard, G. (2019). Transformative water relations: indigenous interventions in global political economies. Glob. Environ. Polit. 19, 1–15 doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00514

Nicoll, F. (2004). “Reconciliation in and out of perspective: white knowing, seeing, curating and being at home in and against Indigenous sovereignty” in Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, ed A. Moreton-Robinson. (Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press), 17–31.

OAG (2018). Perspectives on Climate Change Action in Canada - A Collaborative Report from Auditors General - March 2018. Avaialble online at: https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_otp_201803_e_42883.html#ex2%C2%A0 (accessed June 20, 2020).

Office of the PMO (2017). Statement by the Prime Minister of Canada on National Aboriginal Day. Avaialble online at: https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/statements/2017/06/21/statement-prime-minister-canada-national-aboriginal-day (accessed August 1, 2020).

O'Manique, C. (2017). The Fallacies of Clean Growth: Neoliberal Climate Governance Discourse in Canada. Avaialble online at: https://www.corporatemapping.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CMP_Fallacies-Clean-Growth_June2017.pdf (accessed June 21, 2020).

Pasternak, S., King, H., and Yesno, R. (2019). Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper. Toronto, ON: Yellowhead Institute.

Péloffy, K., Thomas, S., Marshall, D., and Abreu, C. (2019). Setting Expectations for Robust Equivalency Agreements in Canada. Available online at: https://climateactionnetwork.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/CAN-Rac-Equivalency-Paper-2019-web.pdf (accessed June 19, 2020).

Peters, G. P., Andrew, R. M., Canadell, J. G., Friedlingstein, P., Jackson, R. B., Korsbakken, J. I., et al. (2020). Carbon dioxide emissions continue to grow amidst slowly emerging climate policies. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 3–6. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0659-6

Reed, G., Brunet, N. B., and Natcher, D. M. (2020). Can Indigenous community-based monitoring act as a tool for sustainable self-determination? Extract. Indus. Soc. 7, 1283–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2020.04.006

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Galetti, M., Newsome, T. M., Alamagir, M., Crist, E., et al. (2017). World scientists' warning to humanity: a second notice. BioScience 67, 1026–1028. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix125

Rodriguez Acha, M. (2019). “Climate justice must be anti-patriarchal, or it will not be systemic,” in Climate Futures: Reimagining Global Climate Justice, eds K. K. Bhavnani, J. Foran, P. A., Kurian, and D. Munshi (London, UK: Zed Books Ltd.), 246–252.

Simpson, L. B. (2011). Dancing on Our Turtle's Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence. Winnipeg, MB: Arbeiter Ring Pub.

Simpson, L. B. (2017). As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. doi: 10.5749/j.ctt1pwt77c

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies : Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Zed Books Ltd.

Temper, L., Avila, S., Del Bene, D., Gobby, J., Kosoy, N., Le Billon, P., et al. (2020). Movements shaping climate futures: a systematic mapping of protests against fossil fuel and low-carbon energy projects. Environ. Res. Lett. 15:123004. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/abc197

Temper, L.M, Walter, I., Rodriguez Kothari, A., and Turhan, E. (2018). A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: resistances, movements, and alternatives. Sustain. Sci. 13, 747–764. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0543-8

Tully, J. (2017). “Reconciliation here on earth,” in Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings, eds M. Asch, J. Borrows, and J. Tully (University of Toronto Press), 83–132.

United Nations (2007). United NationsDeclaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed June 19, 2020).

Von der Porten, S., de Loë, R., and Plummer, R. (2015). Collaborative environmental governance and indigenous peoples: recommendations for practice. Environ. Pract. 17, 134–144. doi: 10.1017/S146604661500006X

Weiss, J. (2018). Shaping the Future on Haida Gwaii: Life Beyond Settler Colonialism. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Whyte, K. P. (2017). Indigenous climate change studies: indigenizing futures, decolonizing the anthropocene. Engl. Lang. Notes 55, 153–162. doi: 10.1215/00138282-55.1-2.153

Whyte, K. P. (2018a). Indigenous science (fiction) for the Anthropocene: ancestral dystopias and fantasies of climate change crises. Environ. Plann. E Nat. Space. 1, 224–242. doi: 10.1177/2514848618777621

Whyte, K. P. (2018b). “Is it colonial déjà vu? Indigenous peoples and climate injustice,” in Humanities for the Environment: Integrating Knowledges, Forging New Constellations of Practice, eds J. Adamson, M. Davis, and H. Hsinya (Abington, UK: Routledge), 88–104.

Wiebe, S. M. (2019). Sensing policy: engaging affected communities at the intersections of environmental justice and decolonial futures. Polit Groups Ident. 8, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2019.1629315

Wildcat, D. R. (2010). Red Alert!: Saving the Planet with Indigenous knowledge. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Keywords: climate policy and planning, indigenous self-determination, settler colonialism, Canada, decolonization

Citation: Reed G, Gobby J, Sinclair R, Ivey R and Matthews HD (2021) Indigenizing Climate Policy in Canada: A Critical Examination of the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN RoadMap. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:644675. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.644675

Received: 21 December 2020; Accepted: 12 July 2021;

Published: 12 August 2021.

Edited by:

Edgar Liu, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Joshua Cousins, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, United StatesNeil Simcock, Liverpool John Moores University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Reed, Gobby, Sinclair, Ivey and Matthews. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jen Gobby, amVuZ29iYnlAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Graeme Reed

Graeme Reed Jen Gobby

Jen Gobby Rebecca Sinclair3

Rebecca Sinclair3 H. Damon Matthews

H. Damon Matthews