- Department of Management of Regional Energy Systems, Brandenburg University of Technology (BTU) Cottbus-Senftenberg, Cottbus, Germany

The reduction of energy poverty and the expansion of citizen-led community energy projects are two important issues for a just energy transition in the European Union. While some socio-economic aspects of community energy are well researched, there is a dearth of literature on its potential to include vulnerable households and eventually reduce the risk of energy poverty. Through the lens of energy vulnerability thinking, this paper examines current and future drivers of energy poverty in Germany, as well as factors that may limit or facilitate the inclusion of vulnerable consumers in community energy. It draws on previous studies and on 12 semi-structured interviews conducted in the Summer of 2021 with experts in the fields of energy poverty or community energy. Using a three-tenet conceptualization of energy justice, the article argues that community energy projects can mitigate energy poverty in Germany by providing affordable renewable electricity to vulnerable and energy-poor consumers, as well as by establishing fair procedures that consider various vulnerability contexts. Yet, deep-rooted distributional injustices in housing and social transfer schemes that drive energy poverty are likely to remain. In order to advance energy justice, community energy projects hinge on a collaborative multi-level and multi-actor environment.

Introduction

Global energy systems need to change rapidly in order to limit global warming to the 1.5°C long-term goal of the Paris Agreement. Compared to 2°C pathways, 1.5°C compatible scenarios require more rapid transitions in the first half of the century, including lower energy demand, a faster electrification of energy end-use and a faster decarbonization of energy carriers (Rogelj et al., 2018). The shift of fossil-fueled energy systems to renewable energy sources raises questions of energy justice, i.e., determining how to ensure a fair distribution of benefits and burdens (McCauley et al., 2013; Sovacool and Dworkin, 2015). Burdens may arise from consuming too much energy, including waste, overuse and pollution, and from not having enough energy. The latter materializes in the phenomenon of energy poverty (Jenkins, 2019). There is no common definition of energy poverty in academic research or EU legislation and this paper applies Bouzarovski (2014, p. 277) understanding of energy poverty as “[…] the inability of a household to access socially and materially necessitated levels of energy services in the home.” Considering the accessibility of energy services mentioned in the definition, energy poverty in EU countries mostly concerns the affordability of energy services, rather than their scarcity (Heindl et al., 2017). In 2018, around 16.2 % (equivalent to 82.3 million) of European Union (EU) households spent more than twice the national median share on energy expenditure in income, rendering them more likely to face budgetary pressures (Bouzarovski et al., 2020). With the notion of energy services, Bouzarovski (2014) shifts away the focus from the supply of energy carriers as commodities toward the benefits that these energy carriers produce for citizens (Modi et al., 2005). As Bouzarovski and Petrova (2015) put it, energy services enable citizens to become members of society by participating in specific lifestyles, customs and activities. Therefore, households not only need a materially necessitated amount of energy in the home for wellbeing, but also a socially conditioned amount in order to partake in everyday practices fueled by energy (European Parliament, 2017). In 2018, 7.3 % (or 37.4 million) of EU households reported that they had experienced cold homes (Bouzarovski et al., 2020), which affects their material and social needs and practices.

The close link of energy services and basic needs raises the question whether a separate concept of energy poverty is helpful, or in other words, whether energy poverty is merely one among many consequences of income poverty. Yet, energy poverty researchers emphasize that a set of factors underpins the complex condition of energy poverty that go beyond a lack of income (Boardman, 2010; Moore, 2012; Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015; Heindl et al., 2017). The dynamics of energy poverty drivers will be explained in more detail in Section Energy poverty in the EU and in Germany. For now, it is important to note that not all income-poor households will necessarily be energy-poor (Bouzarovski, 2014) while energy poverty does not stop at a particular income level (Schuessler, 2014). Today's multiple political and economic crises are likely to cause the spiraling of living costs and increased energy poverty rates in the next years: The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused an unprecedented job loss (Anderton et al., 2020), while lockdowns required citizens to stay at home and made electricity and heating even more essential goods (Bouzarovski et al., 2020). At the same time, higher rents and the risk of renoviction, i.e., the eviction of tenants after landlord-led refurbishments of buildings particularly in urban areas (Ärlemalm, 2014; Bouzarovski et al., 2018a), increase the energy poverty risk of tenants living in cities. The extension of the EU carbon market on emissions from the building and road transport sectors may further hit European low- and middle-income households living in urban and rural areas, if not counterbalanced by financing measures or readily available alternatives to fossil fuels (Defard and Thalberg, 2022). In 2021, transport and heating fuels have become part of Germany's national emissions trading system. Starting with a fixed price of 25€ per ton of CO2 equivalent which will increase over time, Bach et al. (2019) find that low-income households will bear a greater burden in relation to net income and become more energy vulnerable, if no appropriate support mechanisms are introduced [see Schumacher et al. (2021) or Henger and Stockhausen (2022) for policy measures to disburden energy-poor households]. More recently, high inflation rates and Russia's war of aggression in Ukraine have brought about sharply rising food, fuel and energy prices. In view of potential gas supply bottlenecks due to Russia's war in Ukraine, energy poverty levels can potentially increase among low and lower-middle income households in the next years (Henger and Stockhausen, 2022), since Germany uses imported natural gas both for heating and electricity (Çam et al., 2022).

In order to live up to the catchphrase of leaving no citizen behind (European Commission, 2019), EU energy markets, electricity systems and energy practices need to transform in ways that actively disburden vulnerable households and protect them from energy poverty. One possible path toward more just energy systems is the decentral and participatory provision of renewable energy as practiced in community energy projects. In the EU Clean Energy for All Europeans Package (CEP) that was adopted between 2018 and 2019, EU legislation includes provisions for self-consumption and community energy for the first time. According to the European Commission, “[…] this democratization of energy will alleviate energy poverty and protect vulnerable citizens” (European Commission, 2019, p. 12). Much of previous research on social and economic benefits of community energy projects has focused on their impact on renewables growth (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020; Verde and Rossetto, 2021), public acceptance (Fast, 2013; De Luca et al., 2020; Maleki-Dizaji et al., 2020) or regional economic development (Callaghan and Williams, 2014; Kunze and Becker, 2014; Gancheva et al., 2018). To date, there is little empirical research on the potential of renewable electricity-producing community energy projects to protect and benefit vulnerable consumers and alleviate energy poverty, particularly in the German energy policy context. Martiskainen et al. (2018) focus on Energy Cafés (community-led initiatives providing energy advice) in the UK. Łapniewska (2019) investigates gender equality in European electricity cooperatives without explicitly addressing energy poverty. Campos and Marín-González (2020) as well as Caramizaru and Uihlein (2020) find that only a minority of community energy projects in Europe explicitly aims to tackle energy poverty [see Saintier (2017) for similar findings in the UK]. Regarding barriers to the inclusion of vulnerable consumers in community energy projects, high membership fees (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020) and limited savings/assets (Saunders et al., 2012; Hanke and Lowitzsch, 2020) are commonly mentioned. Potential benefits are found in reduced electricity bills for members of community energy projects (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020), although the functioning of burden-sharing mechanisms needs further research. Saunders et al. (2012) find that energy-poor households in the UK can benefit from additional income generated by feed-in tariffs with the help of innovative financing mechanisms. Besides, micro-donations and solidarity funds of energy communities can benefit vulnerable consumers (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020). In Greece, 2 % of the profits made by energy communities have to be distributed to energy poverty activities by law (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020). Moreover, a supportive network with local institutions is considered a success factor to include vulnerable households and cater to individual preferences (Saunders et al., 2012; Hanke and Lowitzsch, 2020). In this context, Hanke and Lowitzsch (2020, p. 13) highlight “[…] the vast diversity of vulnerability contexts which is likely to render one-size-fits-all approaches ineffective”.

This paper attempts to add empirical knowledge from Germany to the diverse vulnerability contexts increasing the risk of energy poverty as well as to the opportunities of community-based energy initiatives to support vulnerable consumers (van der Horst, 2008; Walker, 2008; Saunders et al., 2012; Martiskainen et al., 2018; Hanke and Lowitzsch, 2020).

While focusing on the German policy context, the paper's broader purpose is to cast a critical eye on the EU's vision of ‘consumers at the heart of the energy transition’ (European Commission, 2019, p. 12). With the help of a three-tenet approach to energy justice, this paper investigates the question: How should community energy projects be set up and regulated to prevent the (re-)production of injustices for vulnerable households suffering energy poverty? Regarding the method employed, 12 semi-structured interviews with experts in the fields of energy poverty or community energy were conducted in order to gain knowledge on limiting and facilitating factors for the inclusion of vulnerable consumers in community energy. Interview findings are also used to update the existing body of knowledge on current and future driving forces of energy poverty in Germany.

The paper is structured as follows: Section Literature review of key concepts outlines the current state of research in the energy poverty and community energy nexus in the European Union as well as in Germany. It also introduces the concept of energy justice as a theoretical framework to discuss the results of the research later on. Section Data and methods presents the method employed and briefly discusses the research design. The subsequent Section Results presents findings of the interviews, followed by discussion and policy implications in Section Discussion. Finally, Section Conclusion summarizes the outcome of the research and presents questions and topics awaiting further exploration.

Literature review of key concepts

Energy poverty in the EU and in Germany

Cooking, cooling, heating, lighting, washing, communication or mobility are essential for people's health and their participation in society (Modi et al., 2005; Haas et al., 2008). Various studies have shown that living in insufficiently heated or cooled homes has detrimental impacts on respiratory, circulatory and cardiovascular systems, as well as on wellbeing (Liddell and Morris, 2010; Liddell and Guiney, 2015; Bouzarovski et al., 2020). These are just some of many manifestations of energy poverty, a subject of increasing scientific and policy relevance in the EU. The Clean Energy for All Europeans Package (CEP) adopted between 2018 and 2019 contains clear energy poverty mitigation objectives in its eight legislative acts (Bouzarovski et al., 2020). For instance, the Directive (EU) 2019/944 on common rules for the internal market for electricity obliges EU Member States to define the concept of ‘[…] vulnerable customers which may refer to energy poverty' (European Parliament, 2017, Article 28) and asks them to introduce adequate frameworks to tackle energy poverty including measurement and monitoring of the number of households in energy poverty, as well as policy measures. Moreover, the Governance Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 requires all Member States to assess the number of households in energy poverty and to implement adequate policies and measures, if data suggest significant levels of energy poverty (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2018a).

Since the focus of this paper is the analysis of current and future drivers of energy poverty in Germany and how community energy projects could address them, the paper will only briefly introduce current national energy poverty estimates based on the (qualified) Ten-Percent-Rule. It should be noted that there are numerous consensual and expenditure-based indicators to measure energy poverty levels which are ideally analyzed in combination to approach the multi-faceted phenomenon of energy poverty (Schuessler, 2014; Tirado Herrero, 2017; Thema and Vondung, 2020). According to the Ten-Percent-Rule introduced by Boardman (1991), a household is energy poor if it cannot have adequate energy services for <10 % of income. In order to avoid false positive results, i.e., to exclude wealthier households that have high energy consumption levels but no income problems, the Ten-Percent-Rule can be modified with relative income caps (Schuessler, 2014). In line with this, Henger and Stockhausen (2022) introduce two income caps that should represent low-income households at risk of poverty as well as lower-middle income households. In the EU, the at-risk-of-poverty threshold is set at an income of less than 60 % of the net median income. In May 2022, 10.4 % of German households with an income below 60 % of the net median income spent more than 10 % on household energy expenses, rising from around 8 % in 2018. If lower-middle income households were to be included (their income is considered <80% of the national average), energy poverty levels rise up to 16.8 % compared with approximately 12 % in 2018. This illustrates how the risk of energy poverty rises for this group that is not considered to be poor in terms of income. It is important to note that the data does not account for government aid packages that may protect households from falling into energy poverty.

Regarding adequate policy action against energy poverty, Germany lacks both a specific energy poverty strategy and an official definition of the term. The federal government views energy poverty within overall poverty and affordability contexts (Deutscher Bundestag, 2019; Bouzarovski et al., 2020). In the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) submitted to the EU Commission, the German government states that vulnerable citizens are entitled to protection covering a humane minimum subsistence level, while social laws and policies are designed in a way that always covers entire subsistence needs. As further energy poverty mitigation measures, the German government mentions multiple initiatives at the local level, such as the Caritas Electricity Savings Check which provides energy audits and energy efficient appliances [see European Commission (2020), pp. 45–46 for an overview of initiatives]. Moreover, the German government writes that electricity and gas market policies include consumer protection measures to prevent disconnection for non-payments (Bouzarovski et al., 2020; Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs Energy, 2020). Fortunately, the number of gas and electricity cuts have indeed decreased between 2017 and 2020 (Bundesnetzagentur, 2022), and new consumer protection policies on energy markets have been introduced since 2020, including a three-months-moratorium on households energy cuts during the pandemic. Electricity and gas cuts decreased by around 20 % in 2020 (ibid.). However, there were still 230.000 electricity cuts and around 24.000 gas cuts registered for 2020 and energy poverty levels according to the Ten-Percent-Rule suggest deficits in the existing policy framework.

Turning to drivers of energy poverty as main focus of this paper, research in the EU has been influenced by the seminal works of Boardman (1991, 2010) who considers low household income, high expenditure on energy, and poor housing efficiency as main causes for energy poverty. While there is no common EU definition of energy poverty [see European Parliament (2017) for the pros and cons], official EU legislation equally refers to the three variables as main causes of energy poverty in Europe (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2019, Recital 59). Tews (2014) and Bleckmann et al. (2016) consider these three factors as main causes for energy poverty in Germany.

More recent academic scholarship (Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015; Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015; Bouzarovski et al., 2018b; Meyer et al., 2018) and EU policy work (Energy Poverty Advisory Hub, 2022) approaches energy poverty from an energy vulnerability perspective, a framework developed by Bouzarovski et al. (2014). This amplified lens to analyze energy poverty will also be applied in this paper. Energy vulnerability thinking understands energy poverty as a more dynamic, fluid state and focuses on the propensity to become energy-poor: A change in housing, social, political or economic circumstances can both push a household into energy poverty or enable it to exit the condition (Bouzarovski et al., 2014, 2018b; Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015). Going beyond what is explicitly mentioned in triadic notions of energy poverty, the concept includes energy needs and social practices as risk factors for energy poverty. For instance, people with special energy requirements (such as infants, people with certain disabilities, people with immune disorders) or citizens who spend a greater portion of their day at home (such as unemployed or retired people) have a higher energy demand (Bouzarovski et al., 2014). The energy vulnerability framework also sees (the lack of) flexibility, i.e., the capacity to adapt to adequate infrastructure, as a risk factor. For instance, tenants are more restricted in their ability to influence energy efficiency retrofits (Powells and Fell, 2019) and may be impacted by power asymmetries in tenancy relationships, particularly in the social housing sector (Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015).

In the German research context, Grossmann (2017) and Kahlheber (2017) highlight that energy poverty is often related to income, age, physical and mental health, nationality, language skills and education. In line with energy vulnerability thinking, Grossmann (2017) uses an intersectional approach to analyze the overlapping determinants of energy poverty, supporting the findings of Kahlheber (2017) who argues that the above mentioned determinants do not only have a causal and cumulative impact but can also recursively condition and intensify existing problems in discriminatory systems like the energy and housing market. Moreover, Bleckmann et al. (2016) and Kahlheber (2017) mention the practices of German energy providers as a structural driver of energy poverty. For instance, most disconnections from the grid are accompanied by additional fees (Bleckmann et al., 2016) while many providers do not allow to pay in installments and some breach contractual ancillary obligations, such as the timing of invoicing (Kahlheber, 2017). The impact of energy providers' practices on energy poverty raises the question if community energy initiatives as alternative energy providers can become relevant actors in the fight against energy poverty.

Community energy in the EU and in Germany

As written in the Clean Energy Package (CEP), the EU advocates a decentralized energy transition and promotes citizens' active participation in the provision of energy (European Commission, 2019). Accordingly, EU citizens are given the right to join citizen-led RES projects, as well as to individually and collectively self-consume energy (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2018b). In this paper, the diversity of collective actors and business models in RES self-consumption (Campos et al., 2020; Horstink et al., 2021) will be subsumed under the widely used term community energy. Bauwens et al. (2016, p. 136) define community energy as ‘[…] formal or informal citizen-led initiatives which propose collaborative solutions on a local basis to facilitate the development of sustainable energy technologies.' In line with RED II provisions (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2018c), this paper considers citizens, local small and mid-size enterprises and public authorities including municipalities as potential members of community energy projects. While the community energy sphere encompasses a range of energy-related activities, the focus of this paper will be the generation, consumption and sale of energy from renewable sources. The potential of individual self-consumption schemes will not be analyzed as a viable option for vulnerable and energy-poor households due to high barriers regarding finances, time, know-how and a certain willingness to take investment risks (Hanke and Lowitzsch, 2020).

The EU obliges Member States to implement an enabling framework for both renewables self-consumers (Article 21) and renewable energy communities (Article 22).1 Moreover, Member States are required to ensure that the participation in renewable energy communities (RECs) is accessible to all consumers, including those in low-income or vulnerable households (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2018b). However, Campos et al. (2020, p. 2) remark that ‘[…] despite its call for inclusiveness, the RED II does not provide explicit guidelines and measures to ensure that RECs are accessible to low-income households.'

In Germany, citizen participation in energy markets has a long history dating back to the first half of the 20th century (Vansintjan, 2015). The introduction of feed-in tariffs in the year 2000 as part of the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) encouraged citizens to invest in local renewable energy in Germany. Solar Photovoltaic (PV) or wind are the most commonly used technologies for community energy in Germany (Kahla, 2018). Energy communities in Germany are predominantly organized as cooperatives, but other legal forms exist, including private limited liability companies, limited liability partnerships, municipal utilities and local distribution companies (co-)owned by municipalities (Kahla, 2018; Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020).

In recent years, the number of large, purely commercial projects set up by project developers and incumbent energy companies no longer effectively controlled by citizens is on the rise (Horstink et al., 2020; Meister et al., 2020). Recasts of the EEG from 2014 onwards foresee the gradual phase-out of feed-in tariffs as well as mandatory direct marketing and tender procedures, which challenge small-scale community energy projects (Meister et al., 2020). Survey data on 883 currently operating energy cooperatives in Germany show that the vast majority of members are natural persons (DGRV, 2020). Municipalities, public institutions and local companies take part as shareholders (DGRV, 2020). Meister et al. (2020) finds that 60 % of renewable energy cooperatives in Germany had municipalities as members and shareholders. Since municipal financial activities are strictly regulated in Germany which may potentially limit financial support (Meister et al., 2020), municipalities can alternatively support energy cooperatives with faster approval processes, as well as with the purchase of energy at cost-covering prices. Furthermore, municipalities often provide (roof) space for PV to cooperatives (Meister et al., 2020). Acquiring suitable roof space is perceived as a major barrier by energy cooperatives, since many of the suitable areas for PV are no longer available (Brummer, 2018; Meister et al., 2020).

Regarding the social structure of energy cooperatives in Germany, Yildiz et al. (2015) found that in 2015, the vast majority were men (80 %) while 51 % of members were university graduates. Higher income groups were largely overrepresented in energy cooperatives: more than 70 % had an individual monthly gross income over 2,500€, around 11 % had a monthly income of <1,500 €, while 2 % of members reported to have no income (Yildiz et al., 2015). Radtke and Ohlhorst (2021) similarly found that community energy initiatives in Germany lack of diversity and representativeness, consisting mainly of affluent men with university degrees. Brummer (2018) found that energy cooperatives in Germany are highly dependent on voluntary work, since the small size of many German energy cooperatives does not make sufficient profits to cover high organizational costs and to spend money on professional consultants. Hence, time resources play a key role besides financial resources. In 2017, a potentially more equitable collective self-consumption scheme was introduced in Germany: With the so-called landlord-to-tenant-electricity model (“Mieterstrom”), the landlord produces electricity from PV plants on the roof and sells it to tenants located in the same multi-occupancy building who participate in the scheme. If surplus electricity is fed into the grid, tenants receive some remuneration (Campos et al., 2020). However, due to several regulatory burdens, the ecological and socio-economic potential of the “Mieterstrom” model remains vastly unused until today (Campos et al., 2020; Umpfenbach and Faber, 2021). Hence, community energy projects seem to benefit only a privileged section of society (Radtke and Ohlhorst, 2021), rendering ownership and participation in the energy transition more exclusionary for marginalized groups (Tarhan, 2022). Moreover, additional costs of the feed-in tariff system to incentivize investment in renewable energy sources are shared among all energy consumers including those who experienced energy poverty. Heindl et al. (2014) and Frondel et al. (2015) find that the German feed-in tariff system has disproportionately burdened low-income households [see also Szulecki et al. (2015)]. As a consequence, in order to prevent the exacerbation of existing inequalities between and within communities (Tarhan, 2022) and to foster energy justice, community energy projects need to attract a more diverse range of members, particularly from marginalized groups.

Energy justice as theoretical framework

In order to answer the question how community energy projects should be set up and regulated to prevent the (re-)production of injustices for vulnerable households suffering energy poverty, the normative framework of energy justice with an emphasis on the benefits and burdens of consumers will be applied (McCauley et al., 2013; Sovacool, 2014; Sareen and Haarstad, 2018). Energy justice is grounded in theories of social and environmental justice (Walker and Day, 2012) and has been applied to discuss both energy poverty (Walker and Day, 2012) and community energy (Jenkins, 2019), however as unrelated topics. This paper focuses on a three-pronged conceptualization of energy justice (McCauley et al., 2013) consisting of (1) distributional justice, (2) justice as recognition and (3) procedural justice.

Most importantly, the phenomenon of energy poverty is typically underpinned by distributional inequalities in terms of income, housing and technology as well as energy prices (Boardman, 2010; Walker and Day, 2012). Distributional justice is a key concern for energy poverty activists engaging in better access to essential energy services and a healthy and energy efficient indoor environment for vulnerable consumers (Walker and Day, 2012). In the context of community energy projects, energy justice implies the equitable distribution of benefits between developers and communities on the one hand, and within communities on the other hand. This presupposes the access to membership in community energy. Secondly, the notion of justice as recognition puts the spotlight on who is socially and institutionally marginalized in ways that drive unjust provisions and distributions of goods (Young, 1990; Honneth, 1995; Fraser, 1999; Schlosberg, 2007). Energy poverty can be considered as the “[…] lack of recognition of the needs of certain groups, and, more fundamentally, as a lack of equal respect accorded to their wellbeing” (Walker and Day, 2012, p. 71). However, the act of acknowledging distinctiveness and special needs is unlikely to sufficiently remedy existing material inequalities (Fraser, 1999). What is more, framing vulnerability merely alongside socio-demographics excludes housing and socio-technical configurations (e.g., how the provision of energy is organized) as important risk factors for energy poverty. Yet, recognition-informed approaches serve as valuable starting point for making injustices visible (Walker and Day, 2012) and for recognizing multiple barriers to participation, such as economic capacities and cultural values (Jenkins, 2019). At the same time, the process of recognition comes with the risk of misrecognition, i.e., a distortion of people's views often based on stereotypes (Jenkins, 2019). In the context of community energy, vulnerable households may be stereotyped as incapable of sound economic decision-making or as being generally disinterested (Jenkins, 2019). Becoming aware of bias that may lead to exclusion is vital for more inclusive community energy projects. As a third dimension, procedural justice thinking helps identifying strategies for remediation of present injustices (Jenkins, 2019). There are three widely recognized constituents of justice in procedural terms:

• access to information,

• access to and meaningful participation in decision-making as well as

• access to legal processes for challenging decision-making processes of public and private entities (Walker and Day, 2012).

In order to let all members or consumers of community energy projects engage in a meaningful way, different levels of prior knowledge need to be taken into consideration, especially when more complex technical and administrative issues are involved (Jenkins, 2019). To influence decision-making processes of public and private entities, it is important to place energy poverty on the agenda of social policy makers as well as energy efficiency policy makers on different levels and sectors of governance (Walker and Day, 2012).

Data and methods

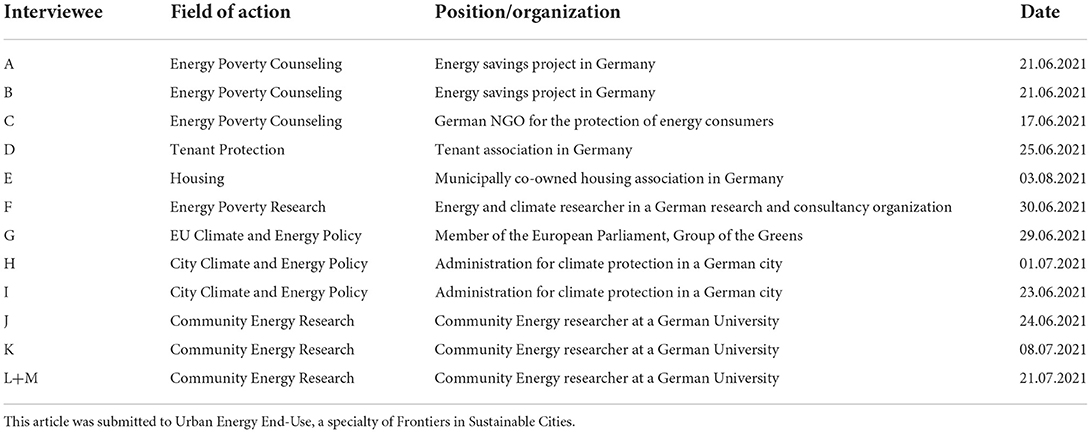

This paper aims to contribute to the discussion on how to steer the decentralized and citizen-led production of renewable energy in community energy projects such that it mitigates energy poverty and helps create fairer energy systems for vulnerable consumers. Due to a lack of best practices in Germany, the aim of my research was to explore the subjective viewpoints of practitioners that may engage as intermediaries, consultants or representatives of vulnerable groups in setting up more equitable community energy projects. The study adopts a qualitative, exploratory approach with semi-structured expert interviews. The research data were obtained through 12 individual in-depth interviews conducted in Summer 2021. To recruit interview participants, I conducted an online desk research to find practitioners from Germany working in diverse fields related to energy poverty or community energy. In the end, I contacted 17 practitioners and was able to secure semi-structured interviews with 12 of them. For viewpoints on energy-related vulnerability contexts in Germany, one energy poverty researcher as well as four practitioners who offer support to households with an increased propensity to experience energy poverty were interviewed. The latter four interviewees work in the fields of consumer protection, the protection of tenants and the social services. In the context of community energy, two interviewees research community energy in Germany from a social science perspective. Another interview was held with social science researchers of a pilot project for low-cost PV systems at the neighborhood level. Moreover, an interview with a representative of a municipal housing association was conducted to explore opportunities of community energy in multi-occupancy buildings. Furthermore, three interviewees work in climate and energy policymaking–two of them at the municipal level, one at EU level. For a list of the interviewees with information on their fields of action (Table 1).

The interviews with open-ended questions lasted on average 1 hour. Each interview was conducted online due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews were recorded with the permission of the interviewees, and later transcribed and translated from German into English. Afterwards, recurrent themes were identified and analyzed in more depth. The open-ended nature of the semi-structured interviews allowed to capture varying perceptions as well as individual concerns of the interviewees working in different environments (Saintier, 2017; Ahlin, 2019).

Results

This section complements existing literature on energy poverty in Germany as outlined in Section Energy poverty in the EU and in Germany with findings from expert interviews on current and potential future drivers of energy poverty. Then, interviewee findings regarding the potential of community energy projects to include energy vulnerable households in Germany are presented, expanding the small body of literature on this topic.

Before outlining drivers of energy poverty in Germany that emerged as common patterns from the interviews, it should be noted that interviewees B and G disagree with the term energy poverty in the case of Germany, as they consider income poverty to be the problem at hand. Interviewee B states that the term is inappropriate as German households can theoretically access plenty of different energy carriers. As mentioned in Section Energy poverty in the EU and in Germany, energy poverty is not necessarily a problem of resource scarcity in industrialized countries. Interviewee G remarks that the term energy poverty is misleading since the predicament rather rests on unjust social policy procedures than on energy policy issues. As the following in-depth analysis of all semi-structured expert interviews indicates, energy poverty is influenced by a multitude of factors that go beyond social policies.

Inabilities to pay electricity and heating costs

The interviewees working directly with energy-poor households agree that in Germany, energy poverty is predominantly experienced by households with a low income, most of them receiving social transfers such as subsistence income support, unemployment benefits or housing benefits. At the same time, the interviewees remark that the social protection system in Germany is relatively advanced in its ability to prevent and mitigate energy poverty compared to other EU countries. This seemingly paradoxical situation can be explained by the structural shortfall of energy-related social transfers. Interviewees A, B, C and F perceive the current allowance for electricity as insufficient to cover a household's energy needs. They consider a nationally standardized allowance of around 38 € per month (for a single household) to be disproportionately low in light of high electricity prices in Germany. Interviewee B notes that the underfunding is particularly problematic for households with children and single parent households. The interviewees agree that allowance amounts should be regularly updated, considering the continuously rising electricity prices. This is ever more important in light of ongoing digitalization and electrification processes, as interviewee D remarks. To date, the standardized allowance has not increased in spite of inflation and the current energy price hikes.

Another problem is that energy poor households receiving social transfers usually have to pay for the more expensive regional default supplier for base and replacement supply (“Grundversorger”). Interviewees A and C remark that more cost-efficient energy tariffs are often not accessible for energy-poor households. For instance, interviewee A explains that energy suppliers often deny grid usage because of previous defaults of payment, while other households are uninformed about more cost-efficient tariffs.

In contrast to the small allowance for electricity, heating costs are usually fully covered by the local job centers or social security offices, unless they are considered inappropriate. The local institutions use different monitoring systems to review whether heating costs are appropriate. However, following the case law of the Federal Social Court of Germany, interviewee B explains that the majority refers to the German national “Heizspiegel” (Heating Survey): The survey provides reference values for heating consumption rates that are considered low, medium, high or too high–the value too high represents the limit up to which costs are covered. Reference values hold for district heating, as well as gas and oil heating. Interviewees A and B state that this regulation is sufficient to meet the energy needs of most households with a central heating system. This is important as heating costs are normally included in the warm rent, hence being in arrear with heating bills increases the termination risk for the flat, as interviewee D notes. While the more extensive heating allowance can pre-empt this risk, low-income households who do not receive social transfers remain at risk to have their gas cut off or receive a termination of their apartment contract. This is particularly alarming for households whose income is just above the threshold to receive income support, as well as for households that meet the eligibility requirements but do not apply for unemployment benefits or housing benefits, as interviewee F remarks. Interviewee A reports that during the COVID-19 pandemic, employees who earned less due to short-time work turned more frequently to the counseling service providing advice on energy savings to cope with the notice of power cuts. For decentral heating systems that are often powered with electricity, interviewees A and B report that high electricity costs cause bills that exceed the maximum value, subsequently requiring a detailed statement explaining why a household's energy consumption is unusually high. The interviewees mention that the nationally standardized allowance for decentralized hot water supply powered by electric heating technologies is too low. Interviewee A comments that this additional social transfer lasts for “[…] taking a shower for 1 min a day”, viewing it as “[…] one of the greatest legal injustices in this area”. Furthermore, based on their experience with local job centers or social security offices, interviewees A and B report that since all devices run on one electric meter, those responsible for the individual examination of high energy consumption have difficulties differentiating between electricity for heating and electricity for other household purposes. Accordingly, they report that households mostly turn to their counseling services for payment problems related to electric heating. Interviewee A comments that the individual assessments are often to the disadvantage of the households:

“It feels a little like they [the local job centers and social security offices] treat this [the coverage of heating costs] like pocket money and not like a government transfer to ensure a minimum subsistence level. The offices can still learn a lot in this regard, including how to comply with the case law”.

The interviewee proposes to offer more energy counseling services and to create a position for an ombudsperson in the local social security offices who is obliged to observe neutrality.

Although high electricity prices may cause financial bottlenecks, at the time of interviewing, none of the interviewees advocates lower electricity prices to help energy-poor households. Considering a lower electricity tax to reduce overall electricity prices, interviewee B criticizes that this would not only disburden low-income households, but also make electricity cheaper for middle- and high-income households as well as industry actors—possibly to a higher extent. To prevent energy-inefficient consumption, interviewees B and F disapprove a social tariff for low-income households as it lacks an ecological steering impact. Interviewee B refers to a policy paper by the welfare organization Caritas (2020) that recommends a climate bonus in the form of a uniform per capita refund of the carbon price. A uniform climate bonus would benefit low-income households to a larger extent in proportion to income, whereas the carbon price renders fossil-fueled energy services relatively more expensive for low-income households relative to income. Interviewees E and F use the term climate bonus in the context of energy efficiency retrofits of buildings—a topic that emerges as a problem area in most interviews and will be explored in more detail below. In general, affordability issues should be treated as ever more pressing in light of the significant price increases.

Energy inefficient buildings and retrofits

The energy performance of residential buildings can impact the risk of energy poverty in different ways. Interviewees A, G and I note that individual energy-saving behavior can only lower energy bills to a limited extent if tenants live in a building with poor energy performance. A common criticism of interviewees A, B, D, F, G, and I is the perceived unwillingness of housing owners to invest in energy efficiency measures. Since investments are contingent on expected profits, the problem often described as landlord-tenant dilemma is particularly prevalent in the case of low-income households, thereby potentially increasing the energy poverty risk. In this regard, interviewee A comments:

“Our energy consultants are trained to inform landlords about public funding, but the people renting to our clients often do not want to become active. They rather leave it at that, receiving the job center's rent payment any way”.

Interviewee A reports that energy-poor households usually live in buildings with poor energy performance due to more affordable gross cold rents. Interviewee B working in a similar project states that some households benefit from living in refurbished social housing, while others have to live in poorly maintained buildings. In this context, interviewees A and I note that both the available social housing units and the funding of new social housing in Germany is declining. Interviewee E, a representative of a municipal housing association criticizes that the coverage of housing costs for low-income households does not evolve on par with rising rents:

“This means, these people, this group is left behind in terms of housing innovations. This also means, that they normally live in buildings that are technically, hence energetically, in a poorer condition. This means in turn, that we have to exclude these buildings from renovation for the time being, because otherwise the tenants could no longer afford their rent. Municipal laws shall be considerably adjusted. Or funding is needed, for instance in the form of a climate bonus for the costs of housing or the like”.

Regarding the climate bonus mentioned in the quote above, interviewee F highlights a state-level policy in Berlin that enables households who receive the unemployment benefit “Hartz IV” to (continue to) live in energy efficient buildings. The Senate of Berlin introduced a climate bonus (31€ for a single household per month) to increase the reference value for gross cold rent. In agreement, interviewees A, B, D, E, F and G are concerned about current national regulations on energy efficiency retrofits of buildings in Germany that cause disproportionate burdens for tenants and may eventually lead to their eviction. Interviewees D, E, F, G and I agree that public funding is key to cushioning high modernization costs for tenants. However, interviewees D and G do not view public funding as a sufficient incentive and demand more commitment from landlords. Due to the shortage of rental stock and spiraling rental prices in German cities, housing owners do not hinge on a good energy-efficiency performance to rent out an apartment. Interviewee A adds:

“In only one case in 12 years were we able to make someone change their night storage heater into a central gas heating–and we did so only because they planned to do it anyway. If the timing is good, change is possible. But if a landlord does not become active on their own part, or if they think it is unnecessary to become active, nothing is going to happen. We can create more and more counseling services and some sort of incentives, but I don't think this will change things. This is a really difficult issue”.

Social and cultural factors

Based on their experiences in energy poverty counseling, interviewees A, B and C report that education on energy-saving behavior is an important part of their work, as well as information on consumer rights and the equipment with energy efficient appliances. In this context, language barriers and diverse cultural practices require tailored counseling and information services. Interviewee A states that due to unawareness on how to read a meter, consumers may report incorrect consumption data, eventually causing additional payments. To make information more transparent and accessible to non-native German speakers, interviewee A and their team of energy consultants successfully pass on consumer feedback to the local energy provider. Interviewees A, B and C remark that high energy bills are just one of multiple problems that households have to cope with. Interviewee B states:

“From my perspective as energy saver, I may think that energy is the greatest problem. But the greatest problem may be a depression, a stress disorder, domestic violence, exhausting childcare, illnesses, or an unsecure residency status. There are so many issues more urgent than energy. Energy only becomes an issue if the notice of a power cut arrives, or the power is cut off already”.

In a similar manner, interviewee C adds that the struggles of energy-poor households become visible only in cases of urgent payment problems or energy cuts, although circumstances of vulnerability can exist before and after. Interviewee A remarks that psychosocial care plays a key role in supporting energy-poor households. To cater to the households' needs, Interviewee A and their energy counseling team have established a network of multiple counseling services they can approach.

Challenges and opportunities of vulnerable consumers' inclusion in community energy

Before outlining factors that may facilitate and restrict vulnerable consumers' inclusion in community energy, it is worth noting that several interviewees highlighted the current adverse situation for community energy in Germany. Half of the interviewees (interviewees B, I, E, G, J, K) note that the initially favorable framework no longer exists and community energy projects in Germany are being rendered increasingly unprofitable. Interviewee K mentions that EU state aid guidelines enforce a shift from feed-in tariff models to tendering schemes, making local community energy projects fear unequal conditions of competition. Interviewee J who is a leading expert on community energy in Germany reports that new initiatives are rarely founded, and the standard business model of small- and mid-sized community energy projects–the installation of PV rooftop plants on public property–has outlived its usefulness. Interviewee J concludes that community energy projects are required to tap into new, more diverse business models.

Direct investments as entry barriers

One of the main topics highlighted by the interviewees were financial entry barriers for vulnerable consumers. The requirement of a minimum investment for members of most community energy projects was a point of concern for six interviewees (interviewees B, C, E, I, J and K). For instance, Interviewee B comments:

“How does the funding work? Someone needs to have money and invest money. […] Low-income households do not have money. Seriously, they do not have any money that they could invest. […] The moment they are supposed to invest, to become a shareholder in such a project, someone else needs to fund it. Will the municipality do this? It can install PV plants on its own rooftops”.

Interviewees C and I agree that it is unrealistic for low-income households to participate as normal shareholders. While Interviewee J remarks that it is theoretically possible for low-income households to invest in community energy shares, with minimum investments for current energy cooperatives starting at 50 € (and may go up to 5,000 € for some citizen wind park projects), the returns on investments will be accordingly low in times of reduced feed-in tariffs. Interviewee K notes that community wind energy projects seem out of reach for low-income households. Moreover, the financial participation with equity always comes with investment risks. In this regard, Interviewee J mentions a potential lack of financial literacy among citizens in Germany in general and among low-income households in particular, assuming a relatively strong correlation between income and education levels. Following this line of thought, Interviewee J is skeptical whether households receiving social transfers should be called on to financially participate in community energy in the first place. Interviewee I adds that community energy projects are normally based on long-term assets, which means that in case of a private financial bottleneck, it is not possible to withdraw from the contract.

Affordability of energy products and services

In spite of high barriers of shareholdership, interviewee J notes that vulnerable and energy-poor households may benefit from consuming affordable energy products and services that community projects offer. As interviewees F and J state, community energy projects usually have lower expectations of return and collective values beyond profitability that provide fertile ground for social business models. Considering locally generated energy products, interviewee C notes that energy-poor households in Germany are usually tenants, therefore they cannot let their rooftops on the lease. Interviewee C perceives the tenant electricity model (“Mieterstrom”) that is part of the German Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) as a potentially supportive scheme, since existing legislation requires tenant electricity tariffs to not exceed the local default supplier tariff. Yet, interviewee B criticizes that average savings from self-consumption are disproportionately low in comparison to payment problems in cases of energy poverty:

“Energy poverty will not be affected [by landlord-to-tenant-electricity]. We are dealing with different scales. With landlord-to-tenant-electricity, people save round about 200 € per year, depending on the load curves. The problem of energy poverty amounts to 1,000 € and more annually”.

What is more, interviewee B remarks that energy generated by a PV rooftop system will not affect heating bills, if heating systems are powered with oil or gas. On the part of the housing owner, interviewees I and J agree that landlord-to-tenant-electricity models tend to be very complicated and come with minimal expected returns. Interviewee G, who has initiated one of the first landlord-to-tenant-electricity models in Germany, notes that the project could have never been realized without the support of a local distribution grid operator, experienced community energy projects and only after tedious exchange of letters with the customs office to allow for the exemption from electricity tax. Interviewee I reports in a similar manner that “[…] realizing a landlord-to-tenant-electricity plant is a bit like graduating from University. The average person would not do this”. Accordingly, interviewee D and J reports that most landlord-to-tenant-electricity sites in Berlin involve experienced third parties and contracting measures, especially when they cover several buildings.

Interviewee J considers different options of energy services that energy communities could provide: Financial returns can be partially used for social projects in cooperation with local social services. Interviewee J reports that some community energy projects in Germany engage in funding activities, however presumably with a focus on local environmental initiatives. Moreover, members of community energy projects could offer energy efficiency advice to vulnerable consumers either within their community or beyond. However, interviewee J notes that the acquisition of clients is complicated and requires intermediaries with local knowledge, while counseling activities are time-consuming and usually not profitable. Interviewee J concludes that these constellations are unlikely to become a widely adopted business model, therefore expecting them to run as pilot projects that both hinge on high levels of commitment of individual members as well as sufficient funding. Another innovative business model for vulnerable consumers are PV balcony plants to lower household electricity bills. This may be an option if rooftops are not suitable for landlord-to-tenant-electricity models and there is a sunny balcony available. Interviewees L and M, who work in a publicly-funded pilot project, report that a small PV balcony plant cost around 400 €, thereby being significantly more affordable compared to PV rooftop plants. Collective orders can lower costs further, and neighborhood networks may spark new sustainability initiatives.

Accessibility of locally sourced electricity

Although municipal actors increasingly invest in community energy, interviewees E, H and I point out that PV-generated electricity on rooftops may not be (sufficiently) passed on to final consumers in general, and vulnerable consumers in particular. This may be the case for both residential and non-residential buildings. Interviewee E, who is a representative of a municipal housing association, states that the company plans to invest between 50 and 65 million Euros in PV rooftop systems. Electricity generated by PV rooftop plants on multi-occupancy buildings will be mainly used for utilities including common-area electricity and working current for heating systems. It is unclear how much surplus energy will remain and whether this will be used to supply households with electricity. According to interviewee E, the housing association will either set up landlord-to-tenant-electricity models or feed into the public grid depending on the revenue outlook. As part of their decarbonization strategy, the association also plans to replace fossil-fueled heating technologies with large-scale electric heat pumps. According to Interviewee E, heat pumps will be installed in new buildings and existing buildings with extensive retrofitting measures:

“We have 18,000 apartments in this city, around 1,700 of them are in the–as we call it–low-price segment. This means they are at the tail end of energy efficiency retrofits or a change of heating technology, until the financing of investments is settled. As part of our climate change strategy, we prioritize buildings with a certain leeway in rents due to a stronger economic performance of our clients–we have relatively good knowledge on this–or buildings where affordability is guaranteed with current funding programs”.

Regarding the latter, Interviewee E refers to a pilot project where almost 600 apartments in multi-occupancy buildings were extensively retrofitted, once long-term funding was secured from the state North Rhine-Westphalia, and the local job center paid higher gross cold rents in the spirit of a climate bonus mentioned in Section Direct investments as entry barriers. Interviewee H and I, both working in the climate protection administration at city level, give examples of how rooftops are used for purposes other than supplying electricity directly to households. The two large cities they are working for have established the practice of leasing rooftops on municipally-owned buildings to independently run local energy cooperatives or other commercial actors. However, interviewee I remarks that this business model is no longer profitable. For the next years, their city plans to equip all suitable rooftops of the around 1,900 municipally-owned properties with PV rooftop plants to cover the city administration's electricity needs. Since the city owns energy intensive properties such as retirement homes, hospitals, swimming pools or a waste incineration plant, <50 % of the city administration's total electricity needs can be covered by means of self-consumption according to interviewee I. What is more, interviewee I points out that the city of Nuremberg currently has to build smaller plants to avoid the situation of producing more energy than is self-consumable and potentially having to pay high network charges. In this regard, interviewees G, I and J advocate the removal of bureaucratic barriers such that energy sharing between small-scale community energy projects is facilitated.

Managing a diverse network of members and intermediaries

The new legal form of RECs promises a diverse composition of community members, such as local government actors and citizens of different socio-economic backgrounds (see Section Energy justice as theoretical framework). Interviewees A, E and J remark it will be challenging to inform different groups of society about community energy projects and convince people and institutions to get involved. According to interviewee J, the average community energy project currently does not reach low-income households; yet local heat networks in rural areas are more diverse. Interviewee A speaks about experiences with a pilot project that featured a smart meter and a corresponding software, in which only households considered as “fit” were selected as participants:

“We provided very intense support and counseling. In fact, it really was a one-on-one counseling over a longer period of time, until we made the project run by itself. I think this is a big challenge with these kinds of systems. Maybe it will work, if you try out pilot projects in neighborhoods where different groups of society live. It may work out this way, but I think it needs a lot of time and a good strategy, otherwise it may backfire”.

The activation of a sufficient number of members is key in business models like landlord-to-tenant-electricity in order to be cost efficient, as interviewees E and J point out. At the same time, interviewees C, E and I remark that membership must not be enforced and interviewee C remarks that landlord-to-tenant agreements should be kept separately from landlord-to-tenant-electricity offers to avoid putting pressure on tenants to participate.

Interviewees J, L and M further mention the gender imbalance in community energy projects. Interviewees L and M report in their joint interview that the technical aspects of decentralized energy systems may discourage less tech-savvy consumers, while the topic of sustainability may be more encouraging. New approaches are important for a more diverse membership. In this regard, interviewee E reflects that alternative framing is not only needed to increase the attractiveness of community energy projects, but also of social transfers:

“I basically think that housing benefits need a campaign for a better reputation. It should no longer be called housing benefit, but climate benefit. This makes it more attractive and conveys the feeling of taking part in climate protection, instead of suggesting indigence”.

On a similar note, interviewee A perceives energy poverty as an issue of shame that is difficult to address publicly. While interviewees A, B and C agree that it is important to raise awareness among citizens and policymakers, it is crucial that the complex issue of energy poverty is not misrepresented, for instance by reproducing stereotypes of the uneducated consumer wasting energy as interviewee A remarks.

Considering the management of members, interviewees A, C and G report that it is important for local energy providers to establish fair and transparent procedures in case of payment problems and debt. Interviewee C states that it is important to give consumers a reasonable period (more than 4 weeks) for the settlement of the payment in arrears. Additionally, interviewees A and C report that it helps energy-poor households to pay in small installments. If the community energy project contracts an external operator, contracts need to be set up such that affordable prices are guaranteed to customers, as interviewee C points out. Based on experiences gathered in the energy poverty project, Interviewee A states that a triangular constellation consisting of an energy provider, the local social security office or job center and an energy counseling project with social workers and energy efficiency expertise works most effectively to cater to energy poor households' needs. In line with this, interviewee J highlights that debt advice and other energy poverty related activities require professional training. Community energy projects often run by volunteers are usually not capable of providing adequate social support to vulnerable consumers.

Considering the activation of public actors, interviewee J remarks that Germany has a long and diverse history of municipalities' involvement in local energy cooperatives. Hence, interviewee J does not expect that the transposition of EU legislation on RECs into German law will significantly alter the current municipal support for community energy projects. While the German EEG allows for the participation of non-natural persons as shareholders in community energy projects, interviewees C and J state that local specifics of municipal tax law (“Kommunalabgabenrecht”) may effectively prevent municipalities from becoming members or shareholders of energy communities. Recasts in the respective levels of law (municipal, state, federal) may spark municipalities' financial engagement.

Moreover, interviewee J considers that a transposition of EU legislation on RECs into German law, including the requirement to provide an enabling framework, can have a political signaling effect to increase the participation of municipalities and local SMEs. Interviewees C, H, I and J agree that profitability will fundamentally determine municipal involvement in community energy projects, although expected returns may be of less importance for municipalities compared to other private investors such as listed housing companies, as interviewee C notes. In line with this, interviewee H, who is in the process of establishing a renewable energy community pilot project in cooperation with the city administration, reports that the pilot project is calculated on a break-even level with the potential for economies of scale. Besides this, interviewee H reflects on the complicated process of setting up an innovative community energy project: feasibility studies for both technical and economic aspects are needed, contracts have to be set up, council bodies must examine the project and governance issues need to be settled. Above all, legal uncertainties due to the delayed transposition into national law remain. In this regard, interviewee G who works in the European Parliament laments that the EU Commission hardly monitored and supported Member States in the transposition process.

Discussion

In the following, interview and literature review findings will be discussed from an energy justice perspective (see Section Energy justice as theoretical framework). According to the triumvirate conception of energy justice (McCauley et al., 2013), energy communities could theoretically help reduce energy poverty in at least three different ways: by improving distributional justice, by recognizing vulnerabilities and make needs more visible and by providing solutions for practices that vulnerable consumers struggle with on the energy market.

Distributional justice

Interview findings coincide with results from the literature review that the struggle of energy-poor households to afford adequate energy services is, inter alia, related to low income, high energy prices and energy inefficient housing. In this regard, the triad of energy poverty factors that was originally identified by Boardman (2010) is an important point of departure for community energy actors. Considering the income situation of energy-poor households, it currently seems unrealistic that community energy can provide an additional source of income. The increasingly unprofitable market conditions have bogged down the once successful movement of community energy in Germany, making financial investments less attractive. Moreover, the situation of energy-poor households typically does not allow for investing risk capital due to a lack of equity or savings available. It would require a detailed review of investment prospects in community energy to better assess whether (micro-)investments are a viable option for reducing energy poverty. This should also include research on social welfare provisions in Germany on the accumulation of assets and the access to loans, since they may thwart the financial participation of households receiving social transfers. Moreover, the viability of financial inclusion measures like on-bill financing and repayment programs (Burke and Stephens, 2017) in community energy could be investigated.

Besides, vulnerable and energy-poor households could benefit as customers from more affordable energy tariffs provided by community energy projects. The literature review and interview statements indicate that high electricity costs are a main driver of energy-related payment difficulties. An opinion shared by the interviewees and confirmed in the literature is that the fixed allowance for electricity as a part of social transfers is too low to cover rising electricity costs, particularly for single parents [see also (Verbraucherzentrale NRW e.V., 2018)]. Since electricity generated by PV rooftop plants is likely to remain the main community energy product in many German cities (Reusswig et al., 2014), affordable electricity prices would be an effective way to disburden vulnerable and energy-poor households. At the moment, introducing low-cost tariffs for vulnerable and energy-poor consumers whilst ensuring cost-efficiency appears to be difficult since the funding scheme for renewable energy projects shifted from fixed feed-in tariffs to tenders which is challenging for small-scale community energy actors (Lowitzsch and Hanke, 2019). One promising way to make community electricity more affordable is energy sharing. In accordance with recent EU legislation on RECs, interviewees advocate energy sharing between several small-scale community energy projects (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2018b).

Interview findings suggest that savings for vulnerable customers are likely to vary considerably–depending not only on the prospect of a favorable policy framework including energy sharing, but also on the specific business model chosen and the technological set-up of the heating system. A detailed analysis of different community energy business models and energy carriers is needed to account for factors with an impact on distributional effects–potentially including fixed operating costs, the amount of tradable surplus energy or the amount of household energy provided. In this regard, interview findings indicate that local housing providers or the local public administration–both potential members of RECs–have their own ambitious decarbonization targets to fulfill and may budget future PV rooftop panels for their own purposes. It depends on the particular set-up of the energy community whether locally sourced renewable electricity is at all accessible to vulnerable and energy-poor households. If PV rooftop panels are used as the default community energy technology in urban areas, households connected to gas and oil-fueled heating systems profit to a lesser extent than households with (sometimes energy inefficient) electric heating systems. This is even more problematic in view of a rising carbon price for heating fuels, particularly for vulnerable consumers who are not eligible for social transfers. It will be primarily the task of climate, energy and social policymakers to create support measures for vulnerable consumers with an increased risk of energy poverty. This will be also important in the context of building renovation plans: findings from the literature and the interviews suggest that it requires the commitment of housing owners and policymakers, rather than the engagement of community energy projects to help vulnerable households and fight renoviction, i.e., eviction after renovation. Regarding high energy prices, interviewees promote alternative, possibly complementary policy measures such as climate bonuses, subsidies for energy efficient appliances or energy efficiency counseling. These cost- and time-intensive measures are typically provided by social welfare institutions, and it is unlikely that they become the main business activity of community energy projects.

Justice as recognition

The EU's firm integration of energy poverty in an enabling framework for RECs as outlined in the REDII can be considered a positive step to raise awareness of energy justice. However, the directive does not provide further guidance on how Member States or community energy projects should achieve this. To date, the German government did not transpose relevant provisions, e.g., on energy sharing, into national law, hence missing the deadline by which transposition should have been achieved. Moreover, there is still no official national definition of the term energy poverty and there is a lack of a German term for “energy vulnerability”. Clarifying the terms may create more visibility and raise awareness among policymakers and community energy actors.

Since this paper only features the insights of experts in the field of energy poverty and community energy, the research questions was approached from the privileged perspectives of others while actors with actual material knowledge (McIntosh and Morse, 2015) were not included. For future research, it would be insightful to interview vulnerable and energy-poor households in Germany on their perceptions of community energy projects. While interview findings indicate that financial incentives are key for participation, there is no first-hand knowledge on the diverse motivations of vulnerable and energy-poor households to join a community energy project. The importance of financial returns, besides ecological motivations, is also found by Radtke and Ohlhorst's (2021) study of members' motivation in German community energy projects. However, their sample consists mainly of higher income groups with lower risks to experience energy poverty. Furthermore, in-depth interviews with members of community energy projects about practices of project organizers to include vulnerable and energy-poor households in Germany would be helpful to reflect on barriers for energy vulnerable households and to think about best practices for more inclusive community energy projects. Further research is needed to assess how adequate, non-discriminatory framings of various energy vulnerability contexts can look like in practice. Local energy communities could only play an important role in enriching the debate on diverse vulnerability contexts of energy consumers in different urban and rural areas, if marginalized groups are included in membership and ownership structures of community energy projects and policy design processes (Tarhan, 2022).

Procedural justice

Interview and literature review findings coincide that practices of energy providers can exacerbate the risk of energy poverty. Community energy projects have various opportunities to care for their members and customers in ways that reduce (the risk of) energy poverty. First and foremost, vulnerable and energy-poor households must have the possibility to become a member. Energy-poor households with previous defaults of payment must not be excluded, instead they could be informed about support measures such as energy efficiency counseling. Moreover, energy communities can design special offers such as new customer bonuses to lower or remove entry barriers for participation. However, the promotion of financial incentive may collide with discriminatory policies: the case law of the Federal Social Court of Germany (2020) foresees that new customer bonuses for supplier switching are counted as income, resulting in a decrease of the overall unemployment benefit “Hartz IV”. This illustrates that debates on procedural justice for vulnerable energy consumers must be brought forward to policymakers.

To establish just procedures in energy communities' customer management, it may be helpful to join forces with local energy counseling services who have gathered a lot of knowledge on consumer-friendly practices. This includes information material in different languages, installment payments and a transparent, easier-to-read bill both for consumers and local social security offices or job centers. Community energy projects can build on these insights from local intermediaries and develop further feedback mechanisms to increase participation of vulnerable households in decision-making. Improved access to information in electricity bills is also one of many new consumer protection rules for the EU's electricity market (European Parliament Council of the European Union, 2019). Future research could focus on the potential of EU consumer protection measures to reduce energy poverty.

Lastly, community energy projects should consider how to establish fair dunning procedures, particularly in times of high inflation and multiple crises. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, several Member States including Germany introduced bans on disconnection (Bouzarovski et al., 2020). For the first time, German municipal energy providers agreed not to cut off defaulting customers for a period of 3 months (Verbraucherzentrale, 2021). However, the measure expired in June 2020, and deferred bills had to be paid immediately afterwards in a one-off sum (Verbraucherzentrale, 2021). Consumer protection experts may support community energy projects in establishing better support frameworks. Yet, it will be difficult to find solutions that also ensure economic efficiency of community energy providers. Policy changes play a key role to improve overall economic conditions for community energy.

Conclusion

The literature review has shown that energy poverty and community energy are two key topics for a just energy transition in the EU and in Germany. For one, community energy projects play a crucial role in boosting the local deployment of renewable energy sources, contributing to the much-needed decarbonization of energy services. At the same time, energy policy measures to achieve said decarbonization may increase the risk of energy poverty, as illustrated by rising carbon prices on home-heating fuels or expensive energy efficiency retrofits. Therefore, it is important that the change from centralized to more decentralized and participative systems of energy provision places the smallest possible burden on vulnerable households and ideally creates benefits for them.

Guided by a three-tenet conceptualization of energy justice, the analysis shows that community energy projects can mitigate energy poverty in Germany by providing low-cost renewable electricity to vulnerable and energy-poor consumers, and by establishing fair procedures that take the various vulnerability contexts of consumers adequately into account. However, structural changes in social and housing policies are required to effectively tackle drivers of energy policy. An example is the incapacity of vulnerable households to access affordable energy-efficient housing, particularly in German cities. The interview findings highlight that the social potential of community energy hinges on a collaborative multi-level and multi-actor environment. First, it depends on a more favorable policy framework for community energy, such as the opportunity of energy sharing. At the moment, the unprofitable economic conditions for community energy in Germany hardly allow for innovative, cost-effective business activities that could offer targeted support to vulnerable households. While the EU's commitment to an enabling framework for energy communities, as envisioned in the REDII, can be considered a positive first step, EU state aid rules increasingly replace the tested funding instrument of feed-in tariffs. Further analysis should be conducted on how community energy projects in Germany and in other EU Member States fare under the new conditions of competition, and which policy instruments support them.

The findings emphasize that close coordination between local actors is essential. These actors include but are not limited to individual landlords, housing companies, local social services and administrations, and of course vulnerable households and community energy projects that are willing to get involved. Future research can explore the motivations of said actors, ideally accounting for diverse vulnerability contexts of energy consumers in selected urban and rural areas. Research may help produce relevant insights for policymakers in the social, energy and climate policy spheres. In the context of the climate crisis, energy poverty mitigation measures must not only effectively secure adequate energy services, but also have an ecological steering effect. In this regard, there is a need for further research to investigate social and ecological benefits of instruments such as social tariffs, climate bonuses, energy efficiency counseling and subsidies for energy efficient appliances.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions