- 1Institute of Geography and Center for Regional Economic Development (CRED), University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 2Independent Researcher, Istanbul, Turkey

This paper explores the governance of a state-led urban renewal project in a politically contested area in the aftermath of a major armed conflict. Building on the ethnocratic regime theory, we explore the governance of the urban renewal process in the historic district of Suriçi by focusing on the political, spatial, and governmental underpinnings of displacement and dispossession in the context of the unresolved “Kurdish Question” of Turkey. We argue that this exclusionary and state-led urban renewal project is shaped around the ethnocratic state interests with limited real estate returns that aims to sanitize and dehistoricize the historic core of Diyarbakir given its political and socioeconomic significance for the Kurdish Movement. The rhetorical formation of a “renewed” historic core epitomizes the racialized governance that intensifies the race-class realities sitting at the center of the decades-old ethnic conflict in Turkey. The central government authority's use of gentrification in practice illustrates the ethnocratic regime's spatial, political, and economic repercussions for the Kurdish population as the country's largest ethnic minority. Suriçi‘s redevelopment illustrates that ethnocratic regime practices coexist with a democratic façade and militarization activates an ethnocratic urban regime. Our findings contribute to the literature on space and power by illustrating the incompleteness and paradoxical elements of settler-colonial urbanism.

Introduction

After the political peace negotiations between the Turkish state and the Kurdish Movement to resolve the decades-long warfare collapsed in 2015, the armed conflict escalated in several urban areas in Turkey's Kurdish region (eastern and southeastern Turkey), where two-thirds of the Kurdish population live (Yegen et al., 2016). More than 5.7 thousand people were killed [International Crisis Group, (2022)], and half a million people were displaced due to the clashes ongoing since July 2015 (Çiçek, 2018). Focusing on the case of Suriçi in Diyarbakir, we explore the racialized governance of the post-conflict reconstruction of the Kurdish towns destroyed by urban warfare in 2015.

Urban renewal, as a state-led gentrification agenda, has been a ubiquitous urban strategy that both central government and municipal authorities have pursued since the early 2000s in many cities across Turkey (Candan and Kolluoglu, 2008; Kuyucu and Ünsal, 2010; Karaman, 2013; Ay, 2019; Yardimci, 2020; Ay and Penpecioglu, 2022; Kuyucu, 2022). A determining characteristic of this nationwide urban redevelopment agenda is the market-based logic of neighborhood-scale demolition and reconstruction often in the form of public-private partnerships as a quintessential case of neoliberal urban restructuring in cities (Lovering and Türkmen, 2011; Demirtas-Milz, 2013; Lelandais, 2014; Unsal, 2015). Also in Diyarbakir, the local municipal authorities partnered with the central government bodies to pursue a similar urban renewal agenda to transform two neighborhoods in the southwest of Suriçi—Alipaşa and Lalebey—between 2004 and 2009 (Yüksel, 2011; Genç, 2021). Although the urban redevelopment with a strong commodification and rehabilitation rhetoric was once attempted in the historic core of Suriçi, we argue that the Turkish state-led reconstruction of Suriçi in the aftermath of the urban warfare is not simply a product of neoliberal governmentality. Although the pre-conflict redevelopment attempts were a part of an overarching neoliberal urban policy agenda to gentrify the historical center as a tourist attraction site and space of consumption, the post-conflict redevelopment transforms the Suriçi district into a “gray space” both politically and economically that is characterized by the centralist state's efforts to subdue the local Kurdish identity in the targeted neighborhoods.

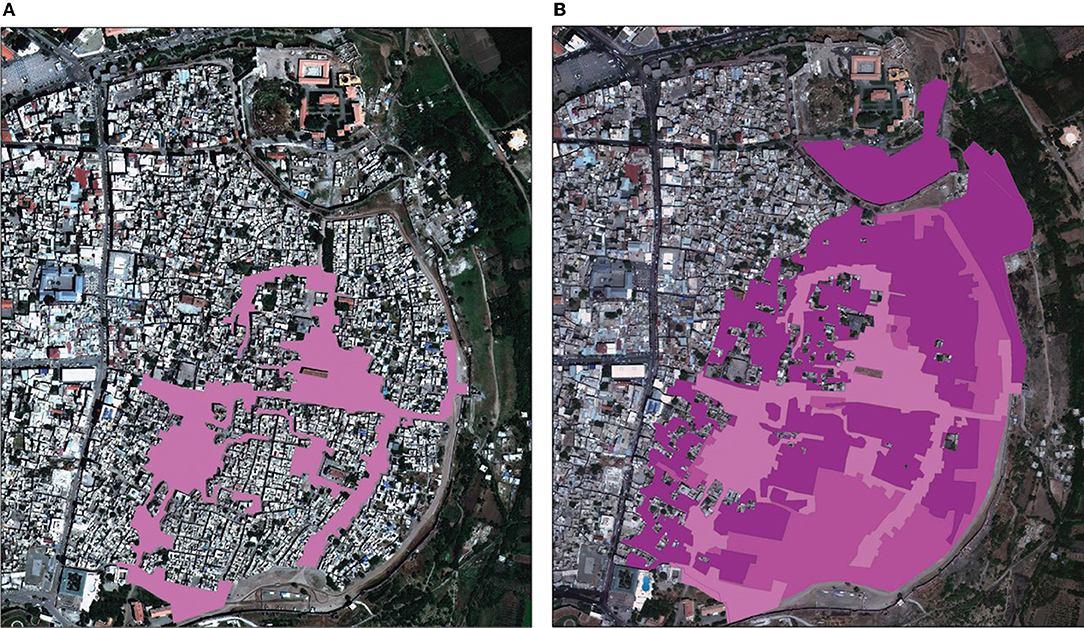

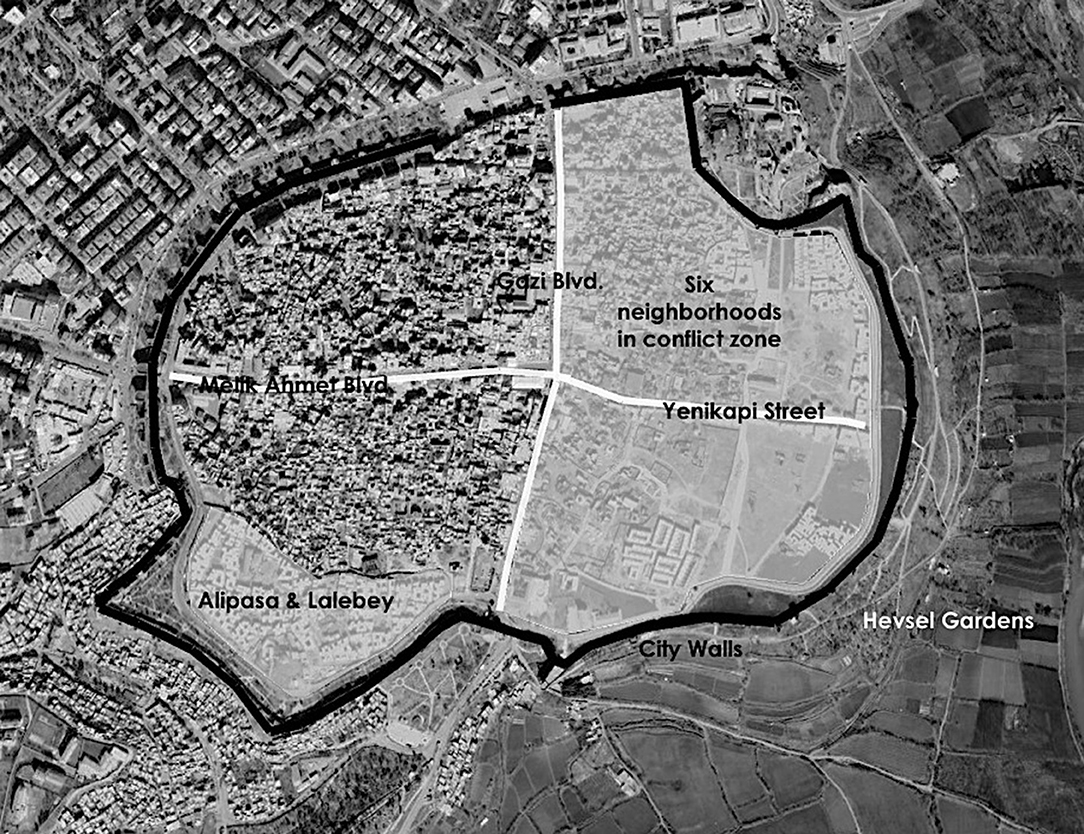

Our case study area, Suriçi, is the historic core of the city of Diyarbakir, the de facto capital of Turkey's Kurdish region. Due to its cultural and historic significance, the Suriçi city walls and the Hevsel Gardens located to the east of the Suriçi district have been on the World Heritage List of UNESCO since 2015 (Figure 1). Primarily, the district has been home to the urban poor and those that were forcibly displaced from rural villages in the 1990s, when the conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurdish Movement climaxed. In 2015, Suriçi became the epicenter of the months-long armed conflict that erupted in the aftermath of the end of peace negotiations between the state and the Kurdish armed resistance. The urban warfare continued for months until the Ministry of Interior Affairs officially announced the end of the military operations on March 9, 2016 (Deutsche Welle Türkçe, 2016). The Turkish state promised to reconstruct the district based on the national urban renewal legislation, and this was followed by a wholesale expropriation of the privately owned land in all 15 neighborhoods of the Suriçi area based on “national defense” claims included in the Expropriation Law.1 Mass demolition of buildings targeted even those neighborhoods unaffected by the armed conflict, turning the majority of eastern and southern Suriçi into an empty field to be rebuilt from scratch. The Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (MEU) operated a large-scale “urban transformation project” directed from Ankara, the capital city of Turkey, without any involvement of local political and civil actors or the residents of Suriçi. This urban renewal project involved complete demolition and partial reconstruction of eight neighborhoods2 in the Suriçi district leaving more than 20,000 inhabitants displaced and dispossessed together with an uncertain future (TMMOB, 2017). The post-conflict urban redevelopment in Suriçi illustrates a fundamental departure from several other cases of state-led urban renewal projects across Turkey given the decades-long ethnic conflict in the region. In other words, the governance of the urban renewal in Suriçi provides a strong empirical case to explore the hegemony of the ethnonational state apparatus in planning, which requires a clear departure from the neoliberal urbanization paradigm that is built on the entrepreneurial state rather than the ethnocratic state.

Figure 1. Suriçi area with City Walls, Hevsel Gardens, main roads and demolished area. Maps data: Google Earth, ©2022 Maxar Technologies.

We take the case of post-conflict reconstruction of the Suriçi district to explore the racialized governance of urban redevelopment as a process of “gray spacing” (Yiftachel, 2009a). We build on critical urban theories on urban colonialism to explain how the remaking of the space overlaps with displaceability and ethnocratic regime structures as a racialized governance practice. We hypothesize that the state-sponsored capital investment directed to the redevelopment of the Suriçi district reflects a process of “gray spacing” under the monopolistic Turkish state order, which marginally keeps its democratic facade as an open ethnocracy. We use the concept of “ethnocracy” as a theoretical framework to explain how ethnonational dominance becomes a mode of governance in the (re)making of the urban space under the hegemonic power of an authoritarian state. Based on qualitative data collected via in-depth interviews with local civil actors; official planning and administrative documents, news articles from local and national media, and secondary data gathered from NGO reports, we analyze the political and economic reverberations of the post-conflict redevelopment in Suriçi by focusing on the governmental underpinnings of displacement and dispossession. We argue that this exclusionary urban renewal process serves the ethnocratic state interests with ambiguous real estate returns, which is an ongoing negotiation process shaped at the intersection of class and ethnic divides. The rhetorical formation of a “renewed” historic core epitomizes the racialized governance that intensifies the race-class realities sitting at the center of the century-old ethnic conflict in Turkey. The central government's use of gentrification in practice illustrates the ethnocratic regime's spatial, political, and economic repercussions for the Kurdish population as the country's largest ethnic minority as a strong case of racialized urban regimes.

In the next section, we develop our theoretical framework to spatialize the ethnonational conflicts together with its implications for urban governance of reconstruction and redevelopment. In section Gray Spacing in Destructed Kurdish Cities: The Case of Suriçi, Diyarbakir, we provide a brief background on the conflict over the contested land of Kurdish region in Turkey. Section Discussion introduces our case study area, the Suriçi district in the city of Diyarbakir, together with our main findings. In section Conclusion, we discuss our findings in light of the ethnocratic regime theory and the gray spacing concept to illustrate the sociopolitical instability of the urban ethnocracy agenda in Suriçi and the paradoxes of the gray spacing practice in the area. We conclude by highlighting our conceptual and empirical contributions for a better understanding of the contradictions of racialized urban economies and directions for future research.

Theoretical Framework

Political geography and political economy jointly shape ethnic relations and politics in contested territories. Ethnic and cultural divisions do not necessarily dissolve with economic development or industrialization often because of an institutionalized cultural division of labor that drives oppression and exploitation based on racial and ethnic divides prevails (Hechter, 1977). The concept of “internal colonialism” is developed to explain these persisting uneven development patterns within a nation-state, which lead to regional economic and political inequalities based on identity-based divides, such as ethnicity, race, religion, and gender (Casanova, 1965; Hechter, 1977). At the height of the civil rights movement in the US, for instance, Martin Luther King Jr. referred to slums as “little more than a domestic colony which leaves inhabitants dominated politically, exploited economically, segregated and humiliated at every turn” (cited by Kurt, 2019). Unlike neocolonialism, the oppression and domination of the “other” are not based on the foreigners vs. natives dichotomy but happen between legally equal citizens of the same nation with formally equal status. Pinderhughes (2011) also uses the internal colonialism theory to explain “the oppression of African Americans living in US ghettos” and defines internal colonialism as “a geographically-based pattern of subordination of a differentiated population located within the dominant power or country” (236). Geographically anchored structural inequalities within a national border based on economic and political power between the dominant group and the internal colony are thus a defining characteristic of internal colonies.

Building on this earlier scholarship on internal colonialism, Yiftachel studies the formation of power that facilitates appropriation and domination of the Israeli state “to Judaize and de-Arabize land and development” (Yiftachel, 2009a, p. 254). In his efforts to characterize the ethnic relations in contested land, Yiftachel (2006) has developed the concept of “ethnocratic regime” to define the state apparatus appropriated by a dominant ethnonational group that aims to advance its own ethnicized political, economic, and territorial agenda over space, resources, and power structures against others (Yiftachel, 2012, p. 96; Goodman and Anderson, 2016). A spatialized interpretation of ethnocracy is, therefore, a particular regime type that uses a thin layer of often distorted practices, which structurally facilitate (explicitly or implicitly) the mechanisms of ethnic control and expansion over contested lands. The conflict in ethnocratic regimes focuses on the nexus of space, ethnicity, and power. Ethnicization constitutes the main force shaping ethnocratic regimes as the most powerful and dynamic factor in shaping space, wealth, and political power. The ethnocratic regime is not completely hegemonic, as the contested land becomes the space for resistance of the indigenous groups to the ethnicization project for their right to self-determination (Yiftachel, 2012). Control and expansion are essential components of a political-geographical project targeting a contested territory. The ethnocratic regime approach also stresses the reciprocity of material, cultural, and political forces and builds on this reciprocity to deconstruct dominant categories, discourses, and historical accounts. The goal of the ethnocratic regime theory is thus not to provide a destructive critique but to rebuild a just and sustainable polity (Yiftachel, 2006, p. 6).

Increasing ethno-populist agendas and practices is a global phenomenon that certainly goes beyond the context of the Israel-Palestine relations, which is the empirical basis that Oren Yiftachel used to develop the theoretical foundations of ethnocratic regimes. Goodman and Anderson (2016) point out that a better understanding of how the dynamics of ethnocracy work has become even more critical with the prominence of political leaders and movements gaining momentum from India to the USA, from Russia to Hungary with open discrimination against ethnic others, and scapegoating of immigrants even in many liberal democracies. Therefore, there have been efforts to develop ethnocratic regime theory further based on empirical research on other national contexts (Kastrissianakis, 2016; Ramesh, 2016; Yacobi, 2016). As a part of that effort, Anderson (2016) defines ethnocracy more broadly, as “government or rule by an ethnic group or ethos specified by religion, language, race or other criteria.”

Most ethnocracies display some formal features of a democratic system of governance. Domination of the numerically ethnic majority is embedded within the electoral parliamentary framework, while the ethnocratic regime promotes the expansion of the dominant group in a contested land and dominates power structures (Yiftachel, 2012). This paradoxical coexistence of democratic governance features and expansionist domination is a defining element of ethnocratic regimes and at the core of its theoretical novelty lies the difference between the regime features and regime structures. Ethnocratic regime structures are the practices of pursuing expansion and control, while the ethnocratic regime features involve adopting a self-representation of a democratic system that tends to work on a surface level (Yiftachel, 2006). Regime structures and features are dichotomous in ethnocracies, revealing the complex pattern of non-democratic practices and norms operating beneath the seemingly democratic framework (Azgin, 2012).

In this approach, six main regime structures characterize the workings of (open) ethnocracies as the basis of ethnocratic regimes. Ethnocratic state and the elites grouped around it daily reproduce the hegemony of the ethnocratic regime using the “hegemonic barriers imposed on public discourse and political discussion” (Yiftachel, 2006, p. 36). The six bases of ethnocratic regime structures (ERS) are as follows:

ERS 1: Demographic control by controlling migration and citizenship to alter ethnic composition that is determined with affiliation with the dominant ethnic nation.

ERS 2: Land and settlement control through ownership, use, development of land with planning and settlement policies to extend the ethnonational control over its territory.

ERS 3: Armed force and securitization of land to maintain oppressive ethnonational control via the military, the police representing the entire state.

ERS 4: Capital flow that privileges the dominant ethnoclasses while being represented as free, neutral, competitive to keep it beyond challenge.

ERS 5: Constitutional law to depoliticize and legitimize patterns of ethnic control, which are often placed outside the realm of legitimately contested issues.

ERS 6: Public space is reformulated around a set of cultural and religious ethnonational symbols, narratives, and practices to reinforce dominant ethnonational groups to silence, degrade, or ridicule contesting cultures.

These regime structures become the public policy instruments of the ethnocratic regime as spheres of control to ensure domination over the contested land under the seemingly democratic facade on a superficial level (Yiftachel, 2006, p. 36–37).

Regional geopolitics shaped the ruling of ethnocratic regimes with ongoing ethnonational conflict over contested land manifesting itself also at the urban level (Fregonese, 2012). The struggle for establishing control over strategic urban sites serves as an instrument to perform sovereignty and power, where the urban is not a coincidental scene for war but the destruction of cities with war has a particular spatiality and function as a strategic object of violence (Campbell et al., 2007). Post-conflict reconstruction of cities in the context of identity-based tensions is also used strategically to solidify authoritarianism and engineer demographic change in urban settlements (Almanasfi, 2019). Resettlement of the communities displaced by war often coincides with the deprivation of marginal and vulnerable groups as the regime in power prioritizes upgrading and order that serve developers' and investors' interests (Sawalha, 2020). Exploring the causality between sovereignty and the built environment in cities provides insights for understanding how conflict over power and control shapes and transforms urban life in between the conditions of war and peace, the civil and the military (Graham, 2004; Davis and Libertun de Duren, 2011). In absence of a national boundary, which is the conventional spatial interpretation of sovereignty, the boundary between the everyday experiences of war and peace, civil and military becomes less prominent. This brings us to the concept of “gray spacing” as an ethnocratic regime practice constituted by different elements of the ethnocratic regime structures.

“Gray Spacing” as an Ethnocratic Regime Practice

Ethnocratic regimes are often structurally unstable as they suffer from long-term conflict and crisis. Ethnocracy centers' regime mechanisms explaining both patterns of ethnic dominance and chronic instability. Azgin (2012, p. 44) suggests that “ethnocratic regimes manage to maintain a firm and complex control system over minorities [but] their hegemonic stability is not sustainable in the long run.” This structural instability can be resolved through democratization, partition, or regime devolution into consociational arrangements. However, the institutionalization of structural discrimination is also possible. This structural instability of ethnocratic regimes largely stems from the backlash from the indigenous groups that are under the pressure of dominant regime structures. Gray spacing alludes to the spatial representation of this structural instability, which is a process of developing spaces and settlements “positioned between the ‘lightness' of legality/approval/safety and the ‘darkness' of eviction/destruction/death” (Yiftachel, 2009a, p. 250).

Gray spaces increasingly characterize contemporary urbanism, probably more so in the Global South, as they involve some forms of informality; remaining outside the official city plans and the legitimate authority of the state (Yiftachel, 2009a,b). Gray spaces are neither eradicated nor incorporated into the urban socio-spatial dynamics and are rather tolerated (Yiftachel, 2015). This ambiguity in their status—vilified while tolerated—puts “gray spaces in a state of ‘permanent temporariness'; concurrently tolerated and condemned, perpetually waiting ‘to be corrected”' (Yiftachel, 2009a, p. 251; emphasis added). Importantly, because a part of the population-based on their ethnicity, class, etc.—is debarred from not only services but also the power that urban citizenship ideally grants, gray spacing helps produce novel colonial relations (Yiftachel, 2009a, 2015).

It is important to note that gray spaces can be created both from below by the marginalized and from above by privileged groups (Yiftachel, 2009a,b, 2015). Therefore, the communities subject to the “gray spacing” of the state are not necessarily passive and powerless victims as the recipients of the ethnocratic regime's urban policy. As Yiftachel (2009a) observes, “power relations are heavily skewed in favor of the state, developers, or middle classes. Yet the invisible population of [gray spaces] is indeed an important actor in shaping cities and regions” (250). Accordingly, the marginalized groups can also use gray spaces to mobilize and self-organize as a practice of resistance to the hegemonic power.

The ethnocratic regime's use of gray spacing as an urban policy inevitably leads to paradoxical outcomes: although the central power uses gray spacing as a method of control, domination, and therefore political stability; gray spaces are by construction destabilized due to the ethnocratic regime's own oppressive policies. In other words, the democratic facade of an ethnocratic urban regime feature is in continuous conflict with the oppressive regime structures, which destabilizes the gray spaces politically and economically as areas prone to conflict as well as negotiation between legality/approval/safety and eviction/destruction/death. In this article, we explore a case where gray spacing is used as an ethnocratic regime practice in post-conflict urban redevelopment, while targeted groups of residents face dispossession, displacement, and deepening socioeconomic inequalities as their living space and livelihoods become the target to demonstrate the ethnocratic regime's authority (Yiftachel, 2020). Building on this theoretical framework, the next section presents a brief historical background on the ethnonational conflict between the state and the Kurdish population in Turkey.

The Contested Land of Kurdish Region in Turkey

The Kurdish population constitutes 15–18 percent of Turkey's population, corresponding to 12–15 million people (Yegen et al., 2016). Despite decades of internal migration to the central and western cities, the Kurdish population is still geographically concentrated in eastern and southeastern Turkey, which is socioeconomically the least developed region of the country. As Turkey's largest ethnic minority, the Kurdish population's collective, cultural, and political rights have been a source of conflict since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey. The First World War had left the Kurdish population in the Middle East divided by national borders of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria while Turkey's nation-building process leaned on a dominant Turkish-Muslim identity and perceived any other identity—including the Kurds—as a threat to its national sovereignty. This long history of the Turkish state's treatment of its Kurdish citizens as a potential threat was responded with several Kurdish uprisings. The latest uprising was fueled by the PKK—the armed wing of the Kurdish Movement—and the armed conflict has been ongoing since 1984 at an uneven pace.

While the Kurdish Question was initially conceptualized as a problem of underdevelopment around the 1960s, later interpretations identified elements of colonial domination (Güneş and Zeydanlioglu, 2013; Duruiz, 2020). Examining the official discourse of the Turkish state on “Kurdishness” and the “Kurdish Question,” for instance, Yegen (1996) highlights consistent negligence and even denial of the fact that the Kurds exist until the end of the 1980s, which was continued as the exclusion of Kurdish identity as an official discourse until early 2000s. According to Yeğen (2015), the Turkish state's approach to the Kurdish Question from its foundation in 1923 until the end of the 1990s is an amalgamation of assimilation, repression, and containment. The PKK's ideological program also perceived the Kurdish region as a colony of the four countries (Yadirgi, 2017) and argued that it was an inter-state colony (Özcan, 2012). Although the PKK had parallels with other leftist Kurdish movements of the time in terms of perceiving the region as a colony, it differed from them as it favored militarization and armed insurgency (Yadirgi, 2017).

Recent scholarship on Turkey's Kurdish Question also argues that Kurdistan's colonization goes back to the early years of the Republic of Turkey as “the newly established state of Turkey practiced a de facto politics of colonization vis-a-vis the territory that had become ‘the south-east' on its map” (Gambetti and Jongerden, 2011, p. 376). The fact that Kurdish-majority regions were ruled under the state of emergency for the majority of the modern history of Turkey supports these claims (Gambetti and Jongerden, 2011). Similarly, Kurt (2019) demonstrates that the Kurdish region of Turkey features several characteristics of an internal colony being under an enduring “state of exception.” Since the early 1990s, which marks the escalation of the armed conflict between the Kurdish guerilla and the Turkish state's armed forces, decade-long martial law rules have continued in the region. Under special administration of “state of emergency governors” appointed by the central government, forced displacements and disappearances of political prisoners and assassination of notable political figures took place, constituting the basis of unresolved collective trauma. Moreover, the uneven regional development of the Kurdish-majority regions compared to the rest of the country reinforces the socioeconomic divides as notable elements of ethnonational domination of the Kurdish population in southeast Turkey and undemocratic state control over this contested land.

Peace Negotiations and Steps Toward Democratization

Turkey's reception of the candidacy status for accession to the European Union in 1999 made way for the beginning of a period of democratic reforms for the Kurdish population's de facto equal citizenship and measures for recognition of their cultural identity (Yeğen, 2015). A series of reforms began to be launched after Turkey was officially recognized as a candidate for European Union membership in 1999, and these reforms speeded up after AKP (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, Justice and Development Party) rose to power in 2002 (Zeydanlioglu, 2013). For example, abolishing the ban on teaching, publishing, and broadcasting in the Kurdish language were steps that generated hopes for a democratic resolution of the ethnonational conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurdish Movement. Another important reform regarding democratization of the highly militarized Kurdish Question was ending the two-decades-long “state of emergency” in the southeast region that ended the de jure “state of exception” under the governorship of the region by state-of-emergency governors with judicial and administrative powers greater than the governors in the rest of the country. The political climate eventually led to a negotiation process between the Turkish state officials and the political representatives of the Kurdish Movement in 2009–2015 to resolve Turkey's decades-old Kurdish Question (Yeğen, 2015). The peace negotiations ostensibly aimed to achieve the final disarmament of the PKK and democratic recognition of the Kurdish population's cultural and political rights in Turkey.

However, the AKP government, representing the Turkish state, unilaterally abandoned the ongoing peace talks with the Kurdish Movement in Spring 2015 (see Güneş and Lowe, 2015; Ercan, 2019). A series of national factors have played a role in bringing this outcome3 (Yeğen, 2015), together with international factors shaped around the changes in regional dynamics in the Kurdistan region due to the Syrian civil war that was considered as a major national security threat by the Turkish state. The abrupt termination of the peace process in 2015 did not only mark the end of a decade of democratization steps (mostly in the form of symbolic political gestures to recognize equal citizenship of the Kurdish citizens) and prevailing hopes for a peaceful resolution of the long-lasting armed conflict. It also marked the beginning of a violent period of armed conflict in 2015 mostly taking place in the form of urban warfare in major Kurdish cities.

Urban Warfare in Major Kurdish Cities and Towns and Nationwide Climate of Fear

The reemergence of armed conflict between Kurdish militants and Turkish state security forces in Kurdish cities starting from the Summer 2015, shortly after the termination of the peace process, triggered a violent process of mass destruction of these cities and displacement of close to half a million Kurdish civilians from their homes and livelihoods (Yeginsu, 2015; Çiçek, 2018). Although the armed conflict largely took place in Kurdish-majority urban areas including the old city of Suriçi (Diyarbakir), Cizre (Sirnak), Nusaybin (Mardin), and Yüksekova (Hakkari); the violence targeting civilians expanded to other major cities in Turkey as well, escalating a nationwide political climate of fear and terror. Finally, the failed coup attempt in July 2016 paved the way for the ruling AKP government to declare a two-year-long “state of emergency” and target all lines of political opposition and dissent, including the Kurdish Movement. Hundreds of pro-Kurdish party HDP's politicians, members of parliament, municipal council members, and mayors, including the party leaders were detained in this process based on terror-related charges, either for supporting the Kurdish militants during the urban warfare or the Kurdish armed forces fighting in Syrian civil war across the border. Furthermore, the political representation of the pro-Kurdish constituency became a direct target at the local level (see Halklarin Demokratik Partisi, 2019). Overall, the ruling party of the Turkish state has dismissed more than 150 democratically elected mayors based on terrorism-related charges and replaced them with state-appointed trustees accountable only upwardly to the central government of Turkey (Tepe and Alemdaroglu, 2021), see also (see Halklarin Demokratik Partisi, 2019).

Gray Spacing in Destructed Kurdish Cities: The Case of Suriçi, Diyarbakir

Background on the Contested Land of Suriçi District

Suriçi district of Diyarbakir is both theoretically and empirically a powerful case to explore the spatial repercussions of a broken peace process followed by destructive urban warfare in the context of ethnonational conflict in contested land. Suriçi4 is a historical district in Diyarbakir, which is the de facto center of Turkey's Kurdish region. Suriçi has been home to various ethnic groups including Kurds, Arabs, Armenians, and Turks, and has a history going back to seven thousand years (UNESCO, (n.d.); Soyukaya, 2017). More than one-third of the residents in Suriçi were non-Muslim prior to the Armenian Genocide in 1915 (Bakan, 2020). Alongside the internal displacements of the Kurdish population particularly in the 1980s and 1990s, Suriçi eventually became a major destination for the Kurdish population marking the most recent demographic composition of the historical district (Bakan, 2020).

Low-rise buildings and historic monuments reflect the district's unique urban and architectural style. Revealing its historical significance and archeological value, Suriçi contained 595 registered cultural monuments before the armed conflict in 2015–2016 (Soyukaya, 2017). Given its historical importance as a heritage site, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism declared Suriçi as “Urban Conservation Area” in 1988, which mandated the Diyarbakir Municipality to develop a Conservation Plan as a legally binding agreement between the local and central governments to monitor the urban development in the historic district starting from 1990 (Kejanli and Dinçer, 2011). Later, the Diyarbakir Walls that surrounds the Suriçi district, and the Hevsel Gardens adjacent to the eastern half of the city walls, were added to the UNESCO's World Cultural Heritage list in 2015. UNESCO's recognition of the historical significance of the area implied the protection of the whole Suriçi district as it was classified as the “buffer zone” for the heritage site and the monuments, as a requirement for the continuation of the World Heritage status.

Suriçi consists of 15 neighborhoods, and it was home to over 50,000 people prior to the armed conflict-induced displacement in 2015 (Soyukaya, 2017). The households living in the district mostly consisted of extended families living together in low-rise semi-informally5 developed buildings, most of them with an inner yard, situated along both sides of narrow streets (see DITAM, 2018). These low-rise residential buildings were mostly located closer to the city walls, and further away from the two major roads crossing Suriçi in north-south (Gazi Boulevard) and east-west (Melik Ahmet Boulevard and Yenikapi Street) directions (TMMOB, 2017). There were mainly mid-rise (four to six-story) buildings along these main roads crossing through the district. The population density increased with the construction of these higher buildings starting from the 1990s and onwards that accommodated the wave of internally displaced rural Kurdish population due to the armed conflict between the Turkish state and Kurdish armed forces (Amnesty International, 2016). These mid-rise buildings along the main roads mostly are for mixed-use, combining residential function with commercial use. While the commercial units in inner parts of Suriçi were mainly small shops–often operated by Suriçi residents–that provide a variety of essential goods and services to meet the needs of its largely low-income residents, commercial units along the main roads served a broader income group (Interview 5).

As the cost of living was exceptionally lower in Suriçi compared to the rest of central Diyarbakir, Suriçi was home to a significant portion of the city's impoverished, and those unemployed or marginally employed under precarious conditions.6 Not only the lower housing and utility expenses but also the communal life and solidarity among its residents socioeconomically sustained the communities in Suriçi before the destruction. As a destination for many households who were forcibly displaced in the 1990s,7 a politicized mindset was prevalent among the Suriçi residents (Bakan, 2020). As a close-knit community, the residents of Suriçi mostly relied on each other socially and economically, and these relations have been so present that “neighborhood” (i.e., the state of having/being neighbors) is among the top things that come to a resident's mind when asked about Suriçi (Kaya Taşdelen, 2020). These relations of solidarity were found to reinforce their political organization as well (Bakan, 2020). A former resident of Suriçi, who lived in one of the neighborhoods in the conflict zone, reflects on the political profile of Suriçi and its residents:

“Think of the significance of Diyarbakir [for Kurdish Movement]; Suriçi had a further significance. Families who settled down in Suriçi in the 1990s knew that Suriçi was a political symbol. When there was a rally in Istasyon [a main square in Diyarbakir], people of Suriçi would organize spontaneously and join the rally as a big group– a cortege of their own. The state also knew that.” (Interview 2).

The pre-destruction organized political power of Suriçi residents was not only reflected in their everyday resistance to the ethnocratic state regime in defense of the political recognition of their Kurdish identity, but also in their capacity to resist developmentalist interventions to transform their living spaces. In 2009, Diyarbakir Metropolitan Municipality and Sur District Municipality, which were both ruled by the pro-Kurdish party at the time, collaborated with the central government, Diyarbakir Governorate, and the Mass Housing Administration (TOKI), and initiated an urban renewal project to demolish and rebuild the two neighborhoods in the southwest edge of Suriçi—Alipaşa and Lalebey. The redevelopment project involved the relocation of 1,276 households to a mass housing project, Çölgüzeli, at the outskirts of the city away from their livelihoods in Suriçi (TMMOB, 2017). The roughly shared vision of the pro-Kurdish municipalities8 and the central government for the area was to redevelop these neighborhoods as sanitized secure tourist attractions and foster economic growth (Genç, 2021). However, the municipalities had to step out of the deal due to a strong backlash from their local constituency, namely the residents of Suriçi (Taş, 2022). Former Suriçi residents interpret the municipality's earlier efforts for urban renewal as a reflection of the power struggle between the pro-Kurdish party and the Turkish state over the city space of Suriçi. “Both sides wanted to leave their mark on the space because it was a unique location with its protected character” (Interviews 2), and the Kurdish Movement wanted to turn Suriçi into a symbol of success for their local government tradition (Interviews 1 and 6).

As reflected in the pro-Kurdish municipality's efforts to transform and redevelop the informally developed neighborhoods in Suriçi, the armed conflict between the Kurdish and Turkish forces demonstrates the “power struggle” to control the district as a symbolic victory against the opponent. The socio-spatial characteristics of Suriçi largely explain why the conflict was concentrated there, but not elsewhere in Diyarbakir. Bakan (2020) proposes four reasons for Suriçi becoming a center of armed conflict. First, the old houses (which were home to multiple families), the narrow streets, and the dead-ends of Suriçi helped the residents develop a close type of bonding. These elements of the urban fabric also made Suriçi both a place that is hard for the intrusion of armed forces and a place where one can more easily defend herself from the attacks. Second, the trust-based, communal, and solidarity-based relations among the district's residents helped them both survive the harsh economic conditions they live in and unite against the threats of the Turkish state. These relations have a political dimension as the population shares a common ideology shaped by ethnic discrimination they commonly experience. Third, the sense of belonging to a place with a rich history, placed in multiculturalism, and mutual grievances based on a traumatic conflict-ridden past and poverty, made Suriçi dwellers form a common identity. Lastly, Suriçi was already relatively autonomous from the interventions of the Turkish state institutions due to its physical landscape. The city walls encircling the district create the opportunity to organize politically without much state interference, but also the institutions of the Kurdish Movement established in Suriçi helped its residents resolve their problems—such as disputes between families—by merely relying on these, rather than those of the Turkish state.

Two Phases of Destruction: Heavy Arms and Excavators

The conflict in Suriçi lasted 103 days, the first curfew was announced in September 2015 marking the beginning of the clashes, and the military operations ended in March 2016 officially announced by the state. One hundred and eighty-four people, including civilians, died in Suriçi, which is among the highest casualties recorded during the urban warfare that erupted in Kurdish-majority towns in the same period [International Crisis Group, (2022)], and more than 20,000 people were displaced (TMMOB, 2017). Although the clashes ended in March 2016, six neighborhoods of eastern Suriçi where the armed conflict concentrated remained closed to the public with an official curfew,9 and the Turkish state initiated destruction at unprecedented levels. Indeed, an interviewee interprets this demolition as revengeful (Interview 4).

Following the end of the operations, the Turkish state expropriated 82% of the Suriçi district based on the Immediate Expropriation Decree approved by the Council of Ministers based on national security claims (Official Gazette, 2016). Because the state already expropriated the majority of the remaining 18% as a part of the previous planning attempt for urban renewal in the two neighborhoods in the southwest, almost the entire Suriçi district became state property with the immediate expropriation (Soyukaya, 2017). The expropriation marks the beginning of the second phase of the destruction in Suriçi in the aftermath of the armed clash between the Turkish security forces and Kurdish militants. Soyukaya (2017, p. 11) argues, that the irreversible damage to the built environment in Suriçi was inflicted once the armed conflict was over, which she calls the second stage of destruction (Figure 2). This second stage of destruction also involved excavations damaging the archeological remains buried underground, which has been the main reason for the official city plans and the Urban Conservation Plan permitted constructions of only up to two-story buildings to protect the archeological heritage of the Suriçi area. In the aftermath of the conflict, the destruction also extended beyond the immediate conflict zone of six neighborhoods and spread to the southwest of Suriçi, which remained outside the conflict zone during the operations (TMMOB, 2017; DITAM, 2018).10

“If we look at the maps from Google Earth to compare the condition of the area when the armed conflict ended in March 2016 and when the excavation work continued until June 2020 in the aftermath of the conflict, it is not just removing debris. We can speak of two different processes of destruction: the one with the armed conflict and the one by the excavation work itself under the name of clearance of debris. There was no consideration to protect registered historic buildings or heritage sites.” (Interview 1)

Even before the mass-expropriation of the Suriçi district, the Prime Minister of Turkey at the time, Davutoglu, revealed the state's agenda for a massive redevelopment in the Suriçi area as a part of “a new securitization planning” (Sözcü, 2016). The official state rhetoric for redevelopment justified the redevelopment agenda with the underdevelopment of the built environment and informality arising since the rapid population growth in the 1990s. There was also an official promise to “rebuild the Sur of Diyarbakir in such a way that it will become a place that everyone wants to see its architectural heritage, just like Toledo of Spain” (Sözcü, 2016), referring to the reconstruction of Toledo in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War (Smith, 2022, p. 401). The state's reconstruction strategy resonates with the urban renewal agenda put forward back in 2009, long before the armed conflict, that Genç (2021) formulates as the attempts for “securitization through marketization”. However, this promise to redevelop Suriçi to revitalize it as a tourist attraction site reverted to a securitization project with a revision in the Urban Conservation Plan to legitimize the development of six police stations and transform the narrow streets into wider roads to connect these new six security checkpoints (Interview 3).

According to field reports by the Diyarbakir office of the Turkish Chamber of Engineers and Architects (TMMOB, 2017), less than one-fifth of the total surface area of the six neighborhoods where armed conflict was concentrated (10.7 hectares of 75.3 hectares) was demolished as of May 2016 while this figure rose to 46.3 hectares as of July 2017. Three thousand five hundred and sixty-nine buildings (the majority of which are low-rise) of 4,985 buildings in these neighborhoods, which is ~72% of the building stock in the area, were demolished. Eighty-seven registered historic heritage buildings and 247 buildings that were found worthy of registration were entirely demolished. The main public authority leading these demolitions in the aftermath of the conflict was the Diyarbakir Police Department as public security forces operating under the Ministry of Internal Affairs (TMMOB, 2017).

The destruction of these neighborhoods had implications on many levels. First, the “historic” centrality of the district was greatly damaged by the demolition (partly or entirely) of registered historic monuments. The excavators did not only destruct the visible terrestrial history of Suriçi but also the infrastructure construction damaged the archeological layers under the earth (Interviews 4 and 5). The urban fabric was effaced from the surface of Diyarbakir–e.g., 93% of Fatihpaşa and 95% of Hasirli neighborhoods were demolished (TMMOB, 2017). A resident of Diyarbakir and also an environmental activist reflects on the post-conflict destruction process pursued under the name of urban renewal, illustrating the trauma that dispossessed residents of Suriçi experienced:

“I will never forget how people were attached to their homes, how people needed their homes, the way they perceived their homes (…) When others talk about urban renewal or demolitions, I wish they could understand what it means for a person to knock down his/her own house. I witnessed many people knocking down their own homes because they did not accept that someone else would come and demolish them. They had built their homes themselves with their own hands, their attachment was unique.” (Interview 4)

The post-conflict destruction by the excavators and construction vehicles targeted a rich collective memory and community history in Suriçi. The scale of destruction rendered the district unrecognizable, completely unfamiliar to its former residents. An Urban Planner who grew up in Diyarbakir tells us about the experience of entering the Suriçi area for the first time, 4 years after the end of the armed conflict, as a part of a technical team to report the condition of the built environment in the area, escorted by security forces:

“It was terrible. On an empty land, there was nothing to take as a reference point to tell where we were standing in the area. As if we were standing on an ordinary field, not a World Heritage site… Today Suriçi has become such a space without any grounds left to tell your story. You are self-estranged, alienated from your culture. And I really wonder: How will this place be spoken of in forty years from now?” (Interview 1)

However, it is not easy to destroy collective memory, even though it was systematically targeted in the post-conflict destruction in Suriçi. What remains from the community narratives continues to challenge and haunt the ethnocratic state's efforts to construct an official ethnocratic narrative and representation of Suriçi. This anxiety of being pushed out of homes and livelihoods combines with the unresolved trauma of the armed conflict, evacuation, and alienation of the people of Suriçi. A mukhtar (headman) draws on the parallels between the experiences of the Kurdish people of Suriçi and the forced displacement of the Armenian residents of Suriçi over a century ago:

“I will never forget the incidents that took place in Sur because it all happened before my eyes. I tell what happened to my child, my child tells hers, this will continue. We will be just like the Armenians that left here in 1915 incidents [referring to the Armenian Genocide] and visit once a year to see what they left behind. We will keep remembering Sur but at the cost of a moral collapse.” (Interview 7)

Planning Process as an Act of Gray Spacing

In the aftermath of the immediate expropriation decree, the central government bodies represented by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, TOKI, and Heritage Conservation Board of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism together with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Governorate of Diyarbakir have been managing the post-conflict redevelopment process. The complete expropriation of private property in the Suriçi district illustrates the state's efforts to create a legal basis by legitimizing the dispossession via law while creating room for physical and social destruction with long-lasting evictions as an outcome. This centralization of post-conflict redevelopment planning demonstrates the broader trend of annihilation of democratically elected municipal governments in the contested Kurdish cities and towns since 2015, not only by appointment of trustees to the municipal offices but also by practically obliterating the local government bodies by replacing them with the central government authority. Moreover, the role of the centrally appointed trustees has been ambiguous, as the state often bypasses these bodies during the decision-making processes. For instance, interview 1 illustrates the workings of the gray spacing as an urban planning practice through the ethnocratic regime structures of centralized power with such an extreme example:

“Even the most basic permitting to operate a high-end restaurant close to the conflict zone is not issued by the Sur municipality; the Ministry has issued permits somehow through some bureaucratic arrangements to enable commercial activities in the area. It is very interesting that although there are already centrally appointed trustees in municipal offices, the decisions are still made by the central government.” (Interview 1)

The gray spacing in the process of redevelopment planning also opens room for manipulation in the cost of redevelopment. Central government bodies (TOKI and Ministry of Environment and Urbanization) invite a selected group of developers to the closed tender procedure, which are inevitably from a small pool of companies that have political ties with the ruling party. The bids from contractors are therefore uncompetitive, which implicitly functions as a transfer of public funds to private developers higher than the market price of the service delivered. The lack of transparency in the planning process also characterizes the development and construction processes (Interview 3). Big developers that win the tender for construction works subcontracted with small developers to cut their costs, and these contractors transfer the work even to smaller contractors often from the region that further cuts down the costs. This “contractors of the contractors” business model allowed by the centrally governed redevelopment lengthens the construction process as well as reduces the quality of final work as there is no mechanism to monitor this basic cost-cutting scheme to guarantee a decent quality of the outcome (Interview 3). Therefore, the mechanisms of keeping the developers accountable weaken as the officials lose track of who does what on the redevelopment site (Interview 5). Therefore, public funds are allocated to big private developers in absence of transparency while these developers increase their profit margins further by cutting down their costs via subcontracting.

A wholesale mass expropriation of the Suriçi area facilitates this process of inefficient and unaccountable spending of public funds on contractual agreements between the state and developers, and between bigger and smaller developers. The law article the state used for expropriation of the private property in Suriçi legitimizes “an immediate expropriation” when it is essential for national defense, which is inconsistent with the fact that the expropriation came after the end of the armed conflict and the official declaration that the district was cleared from the security threats. Interestingly, the Council of Ministers had already designated the whole Suriçi area as a “risky area” based on Law No. 6306 for Redevelopment of Areas under Disaster Risk in 2012 (Official Gazette, 2012). This legislation also provides a legal basis for immediate expropriation of private property for redevelopment in the public interest based on the same Expropriation Law No. 2942 (Article 3). However, the state apparently chose to expropriate the private land in Suriçi based on security concerns in national (defense) interest (Article 27). The state's preference for securitization over development as the basis for expropriation has both political and practical consequences. Practically speaking, it provides a faster bureaucratic process by circumventing formalities in compensation and court-rulings, and politically this decision reveals the state's perception of the area as an ongoing security threat to its national sovereignty.

Displaced and dispossessed property owners in Suriçi were given three options in the aftermath of expropriation: (1) receive monetary compensation for the house, (2) compensation counted as the down payment for a housing unit in Suriçi, or (3) compensation counted as down payment for a unit in one of the social housing projects at the outskirts of the city.11 At the time the rightful owners in Suriçi received these three options in 2017, there was a significant mismatch between the compensation/down payment offered to the property owners in Suriçi and the projected selling price for new units to be built in Suriçi. This implied an unbearable financial burden in the form of long-term debt and uncertainty for those preferring replacement units in Suriçi (Interview 2). The uncertainty was not only financial but also due to the mismatch between the number of housing units demolished in Suriçi and news units rebuilt in Suriçi. Only 506 residences were planned on the site of demolished neighborhoods of Suriçi (Diyarbakir Governorate, 2021), whereas 4,996 households were displaced (Amnesty International, 2016, p. 18). Therefore, the vast majority of the displaced Suriçi inhabitants effectively did not have any chances of returning to their neighborhoods even if they had the financial means, which was already highly unlikely for the vast majority of Suriçi residents.

According to official figures, about 3,000 rightful owners were paid compensation while 2,369 owners demanded a relocation unit in social housing outside the city center (Yilmaz, 2021). Only 302 rightful owners signed an agreement to buy a house in Suriçi, which were distributed in 2021 based on a lottery (Interview 2, Tigris Haber, 2021). Although many residents of Suriçi had a collectively shared desire to go back to Suriçi as early as they could, the lengthy process of waiting for years, changing terms of the compensation schemes, and the destruction of the “character of Suriçi” to a large extent diminished this political dedication to go back (Interview 2). “Many people ended up seeking their individual private returns to their small plots after all this. At least they don't want all this pain to be endured for nothing,” Interviewee 2 states. Therefore, the process of demographic change in Suriçi facilitated via expropriation, real estate speculation, and exclusionary redevelopment planning is ongoing while keeping the marginalized residents of Suriçi outside their neighborhoods and livelihoods.

Post-conflict redevelopment and the destruction of the registered historic monuments in Suriçi have particular importance as a settlement surrounded by the ancient city walls recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and classified as a Buffer Zone itself. The international recognition of the Suriçi area reveals another level of planning as an act of gray spacing. The grassroots initiative carried out with participatory efforts of the local civil society led to the UNESCO recognition in 2015, which essentially depends on the development of the Suriçi area in line with the updated Urban Conservation Plan approved also by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization in 2012. However, the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization dictated a plan revision in December 2016 without following formal procedures, while the post-conflict demolitions and destruction were already ongoing, to provide a legitimate basis for six new police stations and new major roads connecting those checkpoints (Interviews 1,3, and 5).

“Illegal actions were taken in Suriçi. It is not only about the violation of human rights, urban renewal legislation, or property rights. Demolitions have abolished the Urban Conservation Plan of 2012 with the revisions in 2016. However, they [the state] did not share any of these plan revisions with UNESCO, but they had to. (...) Under normal circumstances, this is completely illegal. This is a crime.” (Interview 5)

The local civil society organizations, activists, and professional chambers initially tried to reach UNESCO with their reports about the ongoing destruction in Suriçi through official bureaucratic channels to make UNESCO aware of the irreversible damage to historic heritage in Suriçi. However, local civil society representatives came to realize that their reports were blocked within the bureaucratic pipeline. Later on, the local activists tried to reach UNESCO officials circumventing the bureaucratic hierarchies with success (Interview 5). However, as an organization within the United Nations, UNESCO keeps the central states accountable as their official correspondence. The local efforts eventually managed to direct UNESCO's attention to the destruction of Suriçi, and Interviewee 5 thinks UNESCO's involvement in the Suriçi area marginally played a role in keeping the city walls intact and pressured state officials to remain accountable to the international organization. Yet, their efforts failed in preventing the damage to Suriçi's cultural and historic heritage mostly due to the blind spots in UNESCO'S institutional design that does not have any formal mechanisms to include the local civil society or local governments, which has detrimental consequences for destruction perpetrated by the states themselves (Interview 1).

Current Condition of the “Renewed” Suriçi

Six years after the official declaration of the end of the armed conflict in Suriçi, the current urban fabric consists of housing units developed under the name of “urban renewal” with no resemblance to Suriçi's unique architectural heritage (TMMOB, 2017). For instance, instead of using basalt bricks as the characteristic construction material of demolished homes as aesthetic and climatic requirements given the extreme dry-hot weather of Diyarbakir, the newly built units are only covered with a thin layer of basalt stone to aesthetically mimic an original basalt house (TMMOB, 2017). The inner yards, which were one of the most important components of the houses of Suriçi to serve the extended families' communal lifestyles while keeping the family privacy, are shrunk to basic pathways also lacking the essential elements including the ornamental pools, friezes, and trees for cooling down affect to the living spaces (Interviews 1, 3, and 5; TMMOB, 2020). This lack of consideration of local needs for essential design elements is also attributed to the centralized planning executed by professionals neglecting the realities on the ground (Interviews 1, 3, and 5). The uniformity and the misrepresentation of the architectural style of traditional Diyarbakir homes are often criticized by the locals as “prison-like structures” referring to the lack of character, small windows, inner yards that are connected, and uniformity of the buildings (Interviews 1, 2, 3, and 5; Yeni Yaşam, 2020; Tigris Haber, 2021).

“Houses and streets of Suriçi were organically developed over centuries. Now, the redeveloped streets and buildings are too uniform, and they lack any clues to help you find your way through those labyrinth-like constructions. All buildings are identical in shape and colors; doors, windows, pavements… You can easily get lost.” (Interview 3)

After complete neglect of local actors from the post-conflict redevelopment planning until 2018, the state officials reached out to the Diyarbakir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DTSO) to consult their opinion and support to facilitate tourism-oriented development in the area. DTSO's proposal was to manage the commercial units on Yenikapi Street, one of the recently widened streets in the immediate conflict zone in the east of the Suriçi district, based on an open-air shopping mall model (Interviews 1 and 9). The shopping mall proposal involved ownership remaining at the state, as these parcels are already expropriated and therefore property of the state, and businesses entering as tenants rather than making real estate investments to the economically and socially struggling Suriçi area (Interview 9). The central government approved DTSO's proposal for the use of commercial space, yet the proposal to support local businesses as tenants was not favored. In February 2022, the central government conducted an open and “competitive” public auction to rent 52 shops, open to only those admitted by the auction commission operating under the central government (Tigris Haber, 2022a,b). Local civil society organizations and representatives have criticized this top-down, non-transparent, and exclusive distribution of the new commercial units questioning the direct beneficiaries of this wealth transfer facilitated via immediate expropriation in absence of the former rightful owners who have no legal means to challenge this decision-making process (Tigris Haber, 2022c).

A question that inevitably arises in each interview we conducted on Suriçi, concerns its future: for whom is this new Suriçi? A synthesis of the answers collected in interviews consists of three layers. Firstly, the unresolved collective trauma that people of Suriçi have been exposed to since 2015 with death, forced evictions, dispossession, alienation, and expropriation are a barrier that keeps people of Suriçi away from the district. With the loss of social meaning and obliteration of the social fabric in Suriçi, former residents would not be able to reconstruct their belonging to Suriçi (Interviews 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6). Secondly, with the real estate speculation reflected in the high sale prices of the newly built units, the lower/ lower-middle income residents of Suriçi would not have the financial capacity to retain in the area, which appears as a financial barrier for them to go back (Interviews 3, 7, 8). Even for a very small group of former residents of Suriçi who were able to buy back a unit in Suriçi, the only economically viable option is to seek commercial use from their property to pay back the debt that arises as a cost of redevelopment (Interviews 5, 6, 9). Thirdly, the most recent developments reveal that the state is using its power as the “property owner” to bring in capital and businesses from outside the Kurdish region by imposing closed auctions and opening the real estate market of Suriçi to the national capital. These three factors together imply a fundamental use change from predominantly residential to predominantly commercial space in Suriçi and property transfer from locals to national capital favored by the ruling party of the central government:

“The state was not primarily seeking economic rent in Suriçi. The biggest return of the state from its involvement in redevelopment in Suriçi is abolishing that space of solidarity and it is achieved” (Interview 2).

Discussion

The ethnocratic regime theory provides a useful framework to identify different dimensions of the Turkish state's practices in terms of transforming and reconstructing the district of Suriçi in the post-conflict phase. The state officials' consistent emphasis on securitization and control of Suriçi reveals the state's interest and priority for planning in the district to rule out the threats associated with the residents of Suriçi. As our interviews reveal, the two phases of destruction in Suriçi, one with the armed conflict and the other with the excavation and construction work, illustrate the complexity of the “conflict” in the contested lands of Kurdish cities in Turkey. Therefore, our empirical work focuses particularly on what happened in the Suriçi district after the state officials declared the end of armed clashes in the area. Using the concepts of ethnocratic regime theory, we observe a constant interplay between the regime features and the regime structures as the state seeks a source of legitimacy for the agenda pursued with the destruction and reconstruction in Suriçi. We discuss our findings in light of the six ethnocratic regime structures (ERS) as our analytical framework.

The state officially declares the end of armed conflict, and the “clearance” of the area to reinforce its sovereignty while keeping the curfews in place to avoid the return of the residents and the public eye to the district. The residents were only allowed to return to their homes with police escorts to grab their personal belongings that they could carry themselves, not household equipment and heavy items such as furniture. The presence of security forces for prolonged periods even though the armed clashes were over, represents the state's continuous use of armed forces for securitization and surveillance as the ethnocratic regime structure 3 (ERS 3) predicts. The curfew that officially went on in the conflict zone for more than 4 years has served as a legitimation mechanism to keep the residents out of their neighborhoods for an extended period as a means for demographic control (ERS 1). And, the state's mass expropriation in Suriçi, even in the areas outside the immediate conflict zone, provided the legal basis for the already ongoing mass-demolition of the built environment. Therefore, expropriation functions as an act of control of the land through ownership and legitimization mechanism for cleansing the urban fabric to open up space for developments to facilitate the ethnonational control in the district (ERS 2). While these regime structures continued to transform the Suriçi district rapidly, the state used the constitutional law selectively to depoliticize and legitimize its control over the contested land (ERS 5). The state's decision to demolish rather than renovate the destroyed built environment implies a direct intervention to reformulate the public space and the public culture (ERS 6), which is the most visible outcome of the racialized governance of the post-conflict redevelopment of the Suriçi district. The redistribution of the newly built commercial units as rentals to businesses with an auction that was closed to the locals and former property owners completes the loop of ethnocratic regime practices by demonstrating the capital flow that privileges the dominant ethnonational classes while being presented as a competitive market-based to keep it beyond questioning (ERS 5).

Our findings suggest that there is a chronological order that the state pursues the regime structures to serve the ethnocratic regime's legitimacy concerns while keeping its seemingly democratic facade in place. The state uses its monopoly over “legitimate violence” as a justification mechanism for spatially planning the long-term presence of the police and security checkpoints at several points in the district. The Chamber of Architects and Engineers criticizes this practice as “transforming planning instruments into a securitization mechanism,” which coincides with the Prime Minister's official declaration of the state's new securitization planning concept not just for the Suriçi district but also for the other contested Kurdish majority cities in the region. Therefore, securitization to maintain oppressive ethnonational control plays out as a prerequisite for an opening room for the other ethnocratic regime structures. In the case of Suriçi, mass expropriation of land enhances the state control over the demographics of Suriçi, the capital flow via commercial activities and real estate, and ultimately the construction of a new identity for the public space in Suriçi. The economic development potential of the district as a commercial and tourist attraction site builds on the spatial interventions that strip the area off its residential function for the lower-income groups.

Theoretical insights of gray spacing predict that the communities that are subjected to gray spacing are not necessarily powerless victims, and they can also use the gray spaces to mobilize and self-organize (Yiftachel, 2009a,b). In the case of Suriçi, we have not encountered much of this bottom-up resistance or efforts to reinterpret the gray spacing imposed by the ethnocratic urban regime along the planning process. Interviews reveal that the political motivation of many residents to return to Suriçi once the armed clashes weakened over time as the social and economic costs of displacement people incurred dominated their political claims and attachment to Suriçi. However, we find the efforts put forward by the civil society organizations and professional chambers still relevant and important in this regard, with potential future implications. Particularly, the local efforts to report to UNESCO about the post-conflict destruction of the areas under protection via circumventing the official bureaucratic channels is an act of resistance to the gray spacing of the ethnocratic state. Moreover, it alludes to a major institutional weakness of UNESCO that it takes only the states as official correspondents and not having an official room for dialogue with the local civil society. This becomes crucial to protect World Heritage Sites when the sovereign states threaten the conservation and preservation of the cultural heritage. Our interviewees were largely disappointed with how little they, as the locals, were able to do to stop the destruction. Although they have practically failed in stopping the destruction, the record keeping and reporting from the field constitutes an invaluable resource for a future democratic resolution endeavor of the conflicts that arise during the state-led planning in the post-conflict planning in Suriçi. An important direction for future research on understanding the local community responses to the gray spacing in Suriçi will provide insights about how marginalized communities reproduce their spaces as an act of resistance to the ethnocratic state's agenda of control and dominance.

We focus in this paper on the governance of the post-conflict redevelopment in Suriçi, however the pre-conflict background of disputes on urban renewal in the district constitutes an important dimension to interpret our findings. The pro-Kurdish municipalities (district and metropolitan) stepped out from their partnership with the central government to conduct the redevelopment projects in 2009 due to the political pressure and backlash of the local constituency and the local civil society (Taş, 2022, TMMOB, 2017). However, this deal revealed important overlaps between how pro-Kurdish municipalities and the Turkish state shared a vision for a sanitized Suriçi. When the pro-Kurdish party gained power in municipal politics in 1999, their policy priorities were mostly pro-poor and focused on improving their access to basic urban services. However, this pro-poor municipal policy agenda gradually shifted toward local economic development projects and rebranding Suriçi as a touristic center and a site for consumption, of which urban renewal became a central element (Jongerden, 2022). Jongerden (2022, p. 380) formulates this shift in the pro-Kurdish party's approach to municipal politics transformed “from poverty as a problem, to the poor as a problem.” Both district and metropolitan municipalities embracing this vision of restructuring the historical district as a commercial site manifested “the Kurdish movement's attempts to transform socio-culturally significant sites in tandem with decolonizing politics resonated with neoliberal urban development” (Genç, 2021, 1963). The state-led post-conflict redevelopment in the southwest of Suriçi (Lalebey and Alipaşa Neighborhoods) partially built on this previous urban renewal attempt's legal and planning blueprints that were also once supported by the pro-Kurdish municipalities.

We interpret our findings as an indicator of the ethnocratic state's divergence from the neoliberal motives for marketization. Genç (2021) argues that the urban renewal attempt of the local and central governments' alliance as the forerunner of the destruction/reconstruction in post-2015. The Turkish state had pursued a strategy of “securitization through marketization” in 2009, as Genç (2021) formulates it, which he also claims as the foundation of the post-conflict redevelopment process. Also, Taş (2022) maintains that the state has been utilizing the neoliberal urban transformation projects in the post-conflict period to securitize the contested land and defeat the political resistance in these areas. While we agree that the post-conflict urban renewal in Suriçi has an economic dimension to it, we maintain that the emphasis on securitization has surpassed the neoliberal marketization objectives over time. We argue that the state's decision for mass expropriation of the private property in Suriçi does not prioritize the current or future economic value, but it is an intervention to dispossess the locals to rule out their claims to their land, livelihood, and political community. The lengthy reconstruction process also suggest that the state did not act under time pressure to reap economic returns to the expropriated land. The state's interpretation of property as a tool to secure its sovereignty demonstrates a critical departure from a neoliberal interpretation of property as a means to wealth and economic privilege (see Fawaz, 2014). Therefore, securitization has come at the expense of a neoliberal agenda for marketization in the post-conflict redevelopment directed by the state's ethnonational priorities of domination and control.

Primarily, post-conflict redevelopment that started with mass-demolition destroying the historic heritage and the characteristic urban fabric of Suriçi diminished the economic potential of the newly built real estate in the area. Indeed, the locals interpret the lack of political commitment to resolve the conflicts around property ownership and the protracted process of construction as a purposeful strategy of the state mainly to discourage the former Suriçi residents' return (Interview 2). Second, there is uncertainty concerning the habitability of newly built residences. While prohibitively high prices imply that the Suriçi residents are not welcomed to return to the district given the general lower-income status, the unsold units may remain vacant and on the market until a demand emerges. However, Diyarbakir already has quite well-established affluent districts—such as Kayapinar— that are already appealing to upper and upper-middle-income residents in the city. Moreover, the newly built luxury residences in these eight neighborhoods (six in the immediate conflict zone and two in the formerly designated renewal areas in the southwest of Suriçi) contrast significantly with the socioeconomic profile in the rest of Suriçi, which is still stigmatized with poverty and criminality. The same argument goes for the families that still agreed to purchase a house in the district despite all obstructions. Given their socio-economic status, it is unlikely that they will be able to pay their debt to the Turkish state. In this case, it is likely that the property owners will seek for use changes from residential to commercial, such as hotels, given the architectural design of the buildings that is suitable for use for this purpose as suggested by several interviewees. This raises another dimension of uncertainty concerning whether Diyarbakir has a market demand for tourist accommodation given the political instability in the region. Therefore, the governance of post-conflict redevelopment has led to a crumbling real estate market characterized by uncertainty in various directions, which we interpret as a marketization not being an explicit policy goal for the ethnocratic regime that has characterized the redevelopment planning and outcomes.

Conclusion

In this article, we analyze the racialized governance of large-scale urban renewal planning in the aftermath of urban warfare. We draw on ethnocratic regime theory to characterize political geography and the political economy of the Kurdish Question in Turkey by focusing on the post-conflict redevelopment planning in Suriçi, Diyarbakir as our empirical basis. Ethnocratic regime theory allows us to illustrate the state's reliance on both formal and informal mechanisms to pursue its ethnonational goals by transforming the space. With the background on the contested land of Kurdish region in Turkey, we aim to demonstrate the underpinnings of the ethnonational conflict that materialize in the destruction and the redevelopment of the Suriçi district. Moreover, by using the concept of “gray spacing” we elaborate on the consequences of the ethnocratic regime structures on the ground, both as a planning practice and a characterization of the urban lives and livelihoods of the targeted ethnonational groups.

As the ethnocratic regime theory predicts, our findings also suggest a structural instability for the hegemonic dominance of the ethnocratic regime due to the backlash from the indigenous groups. In the case of Suriçi, we see the process of destabilization of the central state's own power with the economic failure of the ethnocratic regime's place-making attempts. Exacerbated by the complete negligence of the local culture, historical heritage, and political voice, the state has not succeeded in replacing the symbolic significance of Suriçi with the state's hegemonic power. Uncertainty in the local economy of Suriçi regarding the real estate investment and commercial activities explains the lack of market formation in the district while the state remains the dominant economic actor and landowner. Although the dominance of the state authority in decision-making is still prevalent, Suriçi continues to be a contested land. Epitomized by the local civil society's commitment to demand the state's accountability for the destruction, there is also an organized local efforts to revitalize local solidarity networks for the affected population.

This paper on the governance of Suriçi's post-conflict redevelopment presents an extreme case of state dominance in place-making while illustrating the shortcomings of its hegemonic power. The weaponization of planning instruments and construction in the destruction of Suriçi portray alternative, yet common ways that the state uses its monopoly over “legitimate violence.” A better understanding of how geographically based patterns of subordination anchored in racial and ethnic divides shapes cities show directions for future research on how targeted communities respond as they challenge and resist dominance.

Interviews

Interview 1, Urban Planner, NGO, September 2021.

Interview 2, University Student, Resident from Sur, September 2021.

Interview 3, Architect, Turkish Chamber of Engineers and Architects (Diyarbakir Office), October 2021.

Interview 4, Environmental activist, Diyarbakir resident, December 2021.

Interview 5, Archeologist, Diyarbakir resident, October 2021.