- Department of Urbanism, Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands

The 2008 economic crisis has opened the door to new strategies for managing urban resources. In fact, the interest in urban commons (UC) has (re)surfaced both within and outside academia. While literature accounting for existing experiences is growing; UC as a practice begs for further systematization concerning the needed negotiation between institutional recognition and informal self-organization. This is particularly true for temporary urbanism, a strategy for the social repurposing of temporarily unused buildings, whose precarious nature has been deemed to represent just a fixing to the neoliberal logic. In this regard, a non-institutional perspective can help shed light on citymaking as a composite practice in which both institutional and non-institutional actors not only coexist but presuppose each other. In this paper, we explore this issue by focusing on two non-profit organizations working in the Rotterdam and Brussels's housing market: Stad in de Maak and Communa. Through in-depth interviews with the founders and core members of these organizations, as well as with participants to their projects, we show how SidM and Communa operate as intermediaries in the housing sector, filling the gaps left by the market and public actors. Most importantly, our research questions the extent to which the enacting of commoning practices by these organizations can become a pillar of citymaking, configuring an iterative disclosure and (collective) reclosure of urban resources. Evidence shows that, while enacting temporary urbanism differently, both organizations strive for social cooperative ownership of spaces for consolidating their presence in the cities.

Introduction

The 2008 economic downturn brought with itself a huge housing crisis worldwide. With many construction companies going bankrupt and millions of people unable to pay their mortgages and evicted from their homes, the crisis left many city buildings vacant and in need of maintenance as well as many people seeking accommodation. Entrepreneurial and collaborative (Czischke et al., 2012; Lang et al., 2020) forms of housing have taken the opportunity to renegotiate urban social relations by treating urban resources as a common capital.

It is within such a scenario that the interest in the commons as a concept (Ostrom, 1990) and in urban commons (UC) as a practice (Borch and Kornberger, 2015; Anastasopoulos, 2020) has (re)surfaced both within (De Angelis, 2007; Feinberg et al., 2021) and outside academia (Comune di Bologna Urban Data Center, 2014; Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2019). Over the last decade several theoretical and practice-based studies have been dedicated to UC (Borch and Kornberger, 2015; Huron, 2015; Dellenbaugh-Losse et al., 2020), as repurposing practices of unused urban resources. Still, the topic warrants further systematization (Dellenbaugh et al., 2015; O'Neil et al., 2021), especially with respect to the difficulty to consolidate UC as a robust alternative to market- and/or state-led approaches (Feinberg et al., 2021) to the managing of the housing sector and of urban land use, more in general.

The present article aims to tackle this issue by focusing on two non-profit organizations, respectively operating in Rotterdam and Brussels: Stad in de Maak (2022, henceforth SidM) and Communa (2022). These organizations defend and enact a socially innovative alternative to both commercial vacancy management and squatting, through the creation and sharing of common resources. As such, they can be said to act as (non-institutional) intermediary actors in the housing market, providing a link between communities, municipal authorities, and (social) housing corporations. More specifically, these organizations resort to temporary urbanism interventions with the aim to repurpose urban spaces by and for the community, whenever these are left unused. The non-institutional nature of these organizations derives from the fact that they cut through established public and private actors and normative frameworks by creating liminal spaces for intervention that, while being legal, are not (yet) fully recognized or regulated. Practice and experimentation are then key enablers for their projects.

Our objective is to explore how SidM and Communa operate with local communities, not only compensating for the gaps left by the market and institutional public actors, but also consolidating their practices and presence in the city, opening up spaces for a stable non-institutional “disclosure of the commons.” To do so, we relied on a mixed methodology combining an analysis of the documents that the organizations have produced with in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted with both the founders of SidM and Communa, as well as with some of the participants animating their projects. In this latter respect, the research also becomes autoethnographic (Ellis, 2004) to the extent that two authors of the article have been involved in two projects launched by SidM.

The article is structured as follows: Section Urban Commons and Temporary Urbanism explores literature on UC, temporary urbanism and the open questions these practices raise; Section Method outlines the method we followed for the research; Section Stad in the Maak and Communa: introduces SidM and Communa, notably their principles and goals; Section Interviews discusses and connects official documents to the interviews we conducted; Section Extrapolating (Non)Institutional Commoning Dynamics synthesize the findings, extrapolating (non)institutional dynamics from the two case studies and providing remarks on the barriers and enablers to the systemization of UC projects; Section Limitations and Further Research acknowledges limitations of the present study and advances possible further research lines.

Urban Commons And Temporary Urbanism

Contrary to supposed tragedies (Hardin, 2009), Ostrom's (Ostrom, 1990, 2010; Brinkley, 2019) fieldwork-based research on common-pool resources (CPR) - that is resources such as fisheries or forests characterized by non-excludability and rivalry - shows that local communities can enact effective self-management practices of CPR, against and beyond market- and state-led approaches, provided that formal and informal principles and roles are designed and abided to. Literature (Bangratz and Förster, 2021; De Nictolis and Iaione, 2021) shows that legal-institutional support is crucial for the consolidation and thriving of UC projects, especially in their initial stages. In fact, the needed interlacing of institutional support and legal recognition together with informal, self-organized practices is known as the “commons paradox” (Feinberg et al., 2021), which is often at the basis of the difficulty to replicate commons projects in different contexts.

Within an urban setting, this calls for a fine-grained investigation of the mechanisms that make possible the negotiation of the commons paradox by a diverse pool of actors–both institutional and non-institutional–who can attune and respond to the ever-changing needs of citizens and communities. In this respect, temporary urbanism can be regarded as a privileged lens for looking into this issue in that it positions itself as a disruptive strategy, different from commercial vacancy management and squatting, which enacts a reiterated repurposing of urban resources. On the table, however, remains the issue of the extent to which such a strategy can become a systemic approach to citymaking.

An Institutional Perspective

Formally speaking, UC are based on three main principles (Foster and Iaione, 2019): (1) collective governance (i.e., multiple stakeholders involved); (2) an enabling state (i.e., the role of municipality in leading and facilitating new legal and policy framework toward cooperation), (3) social pooling (i.e., values, goods, and services are generated collaboratively and recirculated into the system). On the wave of Ostrom's work, these principles set the frame for an institutional approach to UC, whereby the practice of commoning is well-regulated and formalized (Comune di Bologna Urban Data Center, 2014).

Along the same line, Iaione (2016) claims that the entire city should be considered as a commons (i.e., a “co-city”), that is, “a commons-based, cognitive, collaborative city […] co-produced and co-managed by five actors: social innovators, public authorities, businesses, civil society organizations, and knowledge institutions through an institutionalized public-private partnership of people and communities.” Iaione's idea has the merit to disentangle how the (co)city comes to life as a multilayered process, identifying the relevant actors that take part in its making.

However, as De Lange (2019) notes, such an idea risks delivering a “totalizing oversimplification that loses sight of a more fine-grained, differentiated, or nested form of the commons.” An institutional perspective, indeed, tends to “normalize” UC as a way (by public actors) to “carefully choose the local actors (citizens, movements) to raise the land value with almost zero costs” (De Biase and Mattiucci, 2020). Hence, from this perspective, UC projects are reduced to the latest disguising of neoliberalism in an urban setting. This is particularly true for temporary urbanism: while initially heralded as a “magic” practice combining urban planners' agendas and communities' need for alternative ways for (re)making the city (Urban Catalyst, 2007; Bishop and Williams, 2012), temporary urbanism has been criticized for putting forward “an imaginary of fluid and ephemeral urban connectivity” (Ferreri, 2015) which does little to challenge the neoliberal imperative.

And yet, there is room for a non-institutional perspective to account for the multifaceted process of citymaking and the diversity of its actors. As Stavrides (2010) argues, the urban commons has the potential, as an economically just and socially driven process, to establish threshold spaces of rupture and openness, in opposition as well as within the enclosure perpetrated by capitalism. It remains to see how these threshold spaces can be consolidated despite and beyond the temporariness intrinsic to temporary urbanism.

Temporary Urban Commoning

There is an argument to be made in favor both of citymaking as an endeavor animated by (non)institutional actors and of temporary urban interventions as a systemic disrupting practice.

On the one hand, Cazacu et al. (2020) rightly contend that it is the entire system to benefit from the synergy between formal and informal agents and processes: it is not only a matter of complementarity, but one that creates a new dynamic in/of the city. In a similar vein, Borch and Kornberger (2015) note that UC defines, at once, a particular property regime and a socio-political attitude toward the use of urban resources. This means that one positive way to conceive and enact UC projects lies in fostering a system that encourages citymaking as an iterative open process.

On the other hand, against the aligning of temporary urbanism to the neoliberal imperative, a non-institutional perspective on UC can shed light on the effective impossibility of reducing citymaking to a format; rather, citymaking can be best regarded as a “heteroglossic” process, that is, on Bakhtin's (2010) wave, a process informed by and informing a diversity of instances and agendas that not only coexist but presuppose each other. “Iterative,” “open” and “heteroglossic” become, then, key terms begging for further exploration also including non-institutional actors and practices.

By now the commons has come to identify a system consisting of a resource, its users, the institutions binding them, and the associated mechanism processes (Feinberg et al., 2021). This characterization contains the idea that the commons exists to the extent there is a commoning practice (De Angelis 2007) that conceives and manages the resource as a commons. Going past the institutional approach requires, then, processes of commons' disclosure, as a practice that can be ignited from different entry points, as well as different actors, none of which having a privileged position over others.

From this standpoint, we explore how two non-institutional intermediaries - SidM and Communa - resort to temporary urban strategies for the disclosure and reappropriation of vacant buildings as a possible systemic commoning practice that contributes to citymaking with and beyond the market and institutional public actors. Hence, the article tackles the following Research Questions:

RQ1: What's the role of intermediary actors in the citymaking process?

RQ2: How can intermediary actors consolidate commoning practices beyond the temporariness of their interventions?

Methods

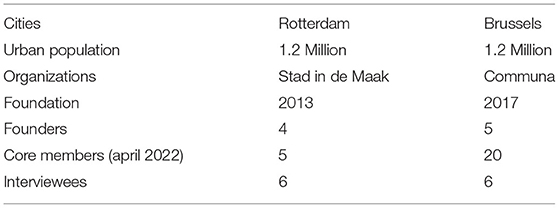

The choice of the two case studies - SidM and Communa (see Table 1 below)–was dictated by contingent and methodological factors. As for SidM, contingent factors have to do with the fact that all three authors of the article are currently based in Rotterdam. This facilitated the contact with the founders of SidM: in fact, two of the authors of the article have been and/or are currently involved in temporary urban projects promoted by SidM, notably Pension Almonde and Vlaardingen Commons. Concerning Communa, after having considered similar organizations to SidM in the Netherlands, we opted for a case study in a different country because we wanted to make the comparison as relevant as possible on a wider scale, being aware that replicability is one of the major limits to the consolidation of UC projects. Hence, Communa was chosen as a suitable case study because: (1) Belgium is a neighboring country to the Netherlands, favoring on-field trips (two); (2) two of the authors already had some contacts with founders of Communa and participants to some of their projects, making the arrangement of the interviews easier.

About methodological factors, we deemed SidM and Communa as two comparable case studies because, despite their difference in size (SidM counts five core members, Communa 20), they share the same aims and they were born at around the same time (2013 and 2017). Moreover, the Netherlands and Belgium share similar population sizes (the Netherlands: 16.5 million; Belgium 11.5 million) and this also applies to the population in the urban areas where SidM and Communa operate, with both Rotterdam (Wikipedia, 2022a) and Brussels (Wikipedia, 2022b) counting ~1.2 million people.

For our research, we relied on a mixed methodology, combining (1) an analysis of the documents that the two organizations have produced, especially on their official websites (Communa, 2022; Stad in de Maak, 2022) and social media channels; (2) in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted with both the core members of SidM and Communa, as well as with some participants animating their projects. In total we conducted 12 interviews, either online or in person: six concerning SidM (two founders, and four participants, including two authors of this article) and six concerning Communa (two core members and four participants). The interviewees were reached out through snowball sampling, starting from either known contacts among the founding members of both SidM and Communa, or known participants to the projects; (3) action-driven autoethnography (Ellis, 2004) by two authors of the article who are/have been involved in two projects launched by SidM. So, their involvement in the research enacted an observed/observer entanglement which was recursively reflected upon by situating the collection of the data from the perspective of the third author of the article.

When analyzing official documents and conducting the interviews, we followed four main thematic threads (a detailed list of the questions can be found in Appendix): (1) history and basic functioning/evolution of the two case studies; (2) structure of the organizations, (internal) decisional processes and (external) relations with other actors/stakeholders; (3) modalities of (self)organization of the participants to SidM and Communa's projects and potential strategies of formalization of their practices; (4) barriers encountered by the organizations and the participants, and possible identified solutions. It was especially the discursive comparison between the official documents and the interviews to highlight the most interesting tensions concerning the way of doing urban commoning by both organizations and how they think of/present themselves. Even though interviewees' first language was not English, all were fluent in English and agreed to have the interviews conducted in English. This favored the homogeneity of the data and their comparison.

On a methodological meta-level, it is worth stressing that the writing of this article was accomplished collaboratively through the sharing of all documents (from the initial abstract to the recordings and the fieldwork notes) as well as by pooling ideas for the systematization of the findings and the procedural steps to follow via the organization of regular online and in- person meetings at “The Space” a community-led working space in Rotterdam also organized as a communal space by two of the authors.

Stad In The Maak And Communa

SidM

SidM was founded in Rotterdam at the end of 2013, as a non-profit organization, by four members: architect Piet Vollaard, artist Erik Jutten, architects and artists Ana DŽokić and Marc Neelen, who work between Belgrade and Rotterdam. Since 2017, artist Daan den Houter has joined the group. Next to them, a heterogeneous pool of a dozen among practitioners and, more or less stable, volunteers has formed.

As the 2008 financial crisis turned into an economic recession, the housing market in Rotterdam was hit hard, with the value of housing companies plummeting and leaving behind a growing number of vacant buildings (“toxic assets”). After a brief recovery in the 2 years 2010–2011, the recession “double-dipped” in 2012 and 2013. It is at this point in time that the four founders of SidM decided to take action, as Vollaard (2020) reminds in an article he authored: “We all felt that the time for reflection was over, and that this was a time to act, to do something real (...) An urban activist ‘do-and-learn-tank’ (...) counteracting neo-liberalist exclusion and speculation and establishing our right to the city.” In the interview, Vollaard recollected the origins of SidM from their headquarter, as follows:

This opportunity came along [i.e., the property in Pieter de Raadstraat 35–37]: a property bought by a social housing corporation just before the crisis hit for too much money, of course [...] They didn't know what to do with it except board it up for 10 years [...] So, we asked “What does it cost you to board it up for 10 years?” Because you have to pay taxes, you have to pay insurance, you have to pay for some upkeep… So, this was 60.000 euros. So we said, “Okay, give us 60.000 euros and we take care of the building for 10 years, you do not have to worry about it anymore, and at least it's not boarded up, which is bad for the street and the value of the property.”

In fact, SidM originated at the nexus of two pressing issues: on the one hand, the repurposing of vacant buildings for local social functions and affordable housing; on the other hand, the active empowerment of urban communities in local (self)organized citymaking. On this point, Vollaard stressed the spiritual and practical links between SidM and the squat movement: “in a sense we are a anti-squat company with a social orientation, not for profit, but we do the same. We keep buildings unsquatted… At the same time we have sort of a squatter ethics and aesthetics.” In fact, the guiding principles listed on SidM's website are: (1) take the property off the market; (2) convert into affordable housing and workspace; (3) collective ownership, collective use; (4) commons free of rent; (5) economical, social and ecological sustainability; (6) democratically organized; (7) for the large part self-organized; (8) on our own terms, on our own strength. Through the interviews discussed in the following section, we will see how these principles play out in the different projects, not without internal tensions.

Since the beginning of 2014, SidM took over from Havensteder–a social housing company operating under the housing policy of the municipality of Rotterdam–seven vacant properties. The pact between SidM and Havensteder is that buildings owned by the company, which are expected to undergo renovation or demolition, can be lent over to SidM to become sites of space-commoning projects. The pact, then, usually implies 2–10-year free-rent leases, in exchange for sparing the owner the costs of repairing, maintaining, and securing the vacant buildings. In turn, SidM applies a sweat-equity logic and a lean approach to the (self) refurbishment of spaces (often through waste materials), with temporary occupants investing time and energy in exchange for affordable rents. These spaces are often facilitated on a project-basis, including through non-monetary exchanges or discounted rate in social cases.

As of April 2022, SidM has launched and pooled communities around two main projects (beyond the building that currently hosts the organization), within which several common projects and facilities have originated: Pension Almonde (December 2019-April 2021); Vlaardingen Commons (March 2022-ongoing). One of the authors of the article was actively involved in Pension Almond; a second author is currently part of the Vlaardingen Commons.

The Pension Almonde consisted of an entire row of houses (52 living units in total) in Almondestraat, north of Rotterdam, expected to be demolished in 2022 (at the time of writing, all buildings are still boarded). The houses of the entire street were originally sold by the City of Rotterdam to Havensteder for redevelopment, due to the worsening conditions of the foundations and the façades.

The stepping in of SidM allowed the Pension Almonde project to emerge. The idea was to provide temporary low-budget accommodations for so-called “urban nomads” (definition by SidM) and working spaces where artists could develop their projects. Accommodations and working spaces occupied the upper floors, while the ground floor units were turned into communal areas collectively managed by the occupants. Here, it was possible for anyone to make use of the set-up facilities, such as a laundry, a library, a kitchen. In the words of Botha (2019), the communal areas represented a sort of “open platform” where to organize initiatives and workshops.

The Vlaardingen Commons project was initiated in Spring 2022. Vlaardingen is a small town-residential area west of Rotterdam. SidM considers the ongoing project to be subsequent to the Pension Almonde experiment. In this case, the renovation of three adjacent streets is involved. The founding logic remains the same, i.e., to offer affordable housing to urban nomads as well as to foster socially sustainable forms of cohabitation, engaging with the local community. Part of the Vlaardingen's project is to take down the fences separating all the houses' gardens with the aim to create a unique green space co-designed by the people living in those three streets. At present, community members are managing a shared vegetable garden, a forge to blacksmith, a laundry space, a workshop, a second-hand shop, a library and a recently opened hostel. The project is expected to last at least a couple of years, in the first place.

Communa

Communa is a non-profit organization founded in 2017 in Brussels. The founding group now counts four people (including Maxime Zait, whom we interviewed), three of which have a background in law, while one is an engineer. At present, the group of stable collaborators has around 20 people, who cover a variety of tasks and activities based on each one's expertise (e.g., communication, development, technical support, partnership, finance). Zaït recounted the origin of Communa by clarifying what distinguishes the organization from the squatting movement:

We ended up discovering the squat movement and then all these empty places. But squatters break the door, they get in, and then they negotiate a contract. And then we got the idea: but if they managed to negotiate a contract, then why do they need to break the door? And eventually we understood that it's possible to do it without breaking the door. [...] At some point, one owner said, “okay, I let you use my building for free for a few months.” And we opened a crazy community there.

This approach resonates with Vollaard's words reported above about SidM's roots. More generally, the main goal of Communa is to enact temporary urban interventions by occupying and repurposing temporarily vacant properties across the Brussels region, which at present hosts more than 6 million square meters of empty buildings (Communa, 2022). Similarly, to SidM, Communa aims to promote projects that help people seeking affordable housing and urban activists looking for affordable working spaces to meet their needs. Since 2017, Communa has fostered an “ecosystem” (Communa, 2022) of 18 projects, of which nine are currently active. The participants we interviewed were from both concluded and ongoing projects, such as the now terminated project “La Buissonnière,” a former school in Saint-Gilles where the classrooms were transformed into community housing, associations offices and artist's studios; “Le Tri Postal,” a place for community activities, cultural events and circular economy, just closed in March 2022, “La Serre,” an ongoing multifunctional barn hosting cultural programming, unsold food processing activities, repair workshops and a large share co-working space for artists; and “Maxima” a group of buildings in the neighborhood of forest, which currently hosts events, sport activities for the local community (such as a boxing training space) a medialab, spaces for artisans and artists, and accommodations for women (Communa, 2022).

More broadly, as stated on the organization's website, Communa's (2022) broader mission is to favor the emergence of socially-relevant projects and to do so (1) in a participatory way, that is, by pooling local communities and enticing their self-organization and (2) by developing a circular economy that can be sustainable in the long run and beneficial to the whole city.

Communa articulates its role through diverse facets: in the words of Zaït, “it's super diverse. [...] Our role is one of facilitator, one of social innovator, one of activists.” Informing these multifacetedness are six principles: (1) affordability (of spaces); (2) mutualization (i.e., synergic connection among projects); (3) durability (i.e., consolidation of projects in the mid-long term); (4) federation (i.e., creating a network with similar organizations); (5) spreading (i.e., empowerment of communities through know-how support and the reaching out to institutional actors to strengthen the organization); (6) “positive” institutionalization (or “associationism”). We will unpack these principles through the interviews, in the following section.

Interviews

A good entry point for the analysis of the interviews is represented by the lists of principles that both SidM and Communa have set for themselves. From these, it will be easier to chart out the discourses and practices of both organizers and participants in terms of roles, operations, enablers and barriers encountered in their projects. In fact, the linking of principles to interviews and autoethnographic action research will bring to light some inevitable tensions: it is the unpacking of these tensions that can promote viable paths for the existence of intermediary actors enacting commons projects in the urban fabric, as well as their reworking of market and public actors' courses of action.

SidM

The first three principles of SidM can be grouped together, insofar as they define three core features of the organization's raison d'être: (1) take the property off the market; (2) convert into affordable housing and workspace; (3) promote collective ownership and collective use. Beyond the idea of occupying and revitalizing vacant buildings through temporary occupation lies the principle (and bigger political stake) to tackle and redress the speculation to which properties are subjected in Rotterdam and, more largely, in the Netherlands. On this point, Vollaard was very clear in the course of the interview: “The problem here is that our social housing stock has been sold to investors, mainly foreign investors, who, as soon as they get the chance, move the rent up way beyond what can be called social.”

The commodification of the social in “social housing” is what, in the end, makes properties unaffordable for low-income groups. This is the starting point of SidM's (long-term) mission to take properties off the market and turn them into cooperative housing. This shift would allow to control the living/working spaces through collective ownership, eventually preventing speculation from the single individual: as Jutten specified “when we talk about buying, it is not for us to own it, but for the users to have the owners' rights, so that even them can't sell it anymore.” On this point, De Lange and De Waal (2019) conceptualize ownership as both the degree to which city dwellers feel a sense of responsibility for shared issues and the capacity to take action for these matters. In this regard, then, ownership entails empowerment within a constantly renegotiated social process rather than a state of affairs legally bound once and for all.

The way in which SidM is attempting to concretize its mission is by promoting temporary UC projects, which tend to vary in terms of duration, size, and governance: “Each project and each place is new,” Vollaard acknowledged, “in the sense that it has its own characteristics. As an architect, I'm very site specific and contextual.” Apart from that, there are some basic criteria, consolidated over the years, that can be singled out and grouped under principles 4, 5, 6, and 7: (4) commons free of rent; (5) economical, social and ecological sustainability; (6) spaces democratically organized; (7) spaces for the large part self-organized. To unpack these principles, it is worth taking a longitudinal perspective over SidM's projects, from its birth with the occupation of the building in Pieter de Raadstraat 35–37, to Pension Almonde and Vlaardingen Commons.

To begin with–principle 4–there is the idea that in each project around ? of the space shall be allocated as a common space, open to all, and collectively organized. This rule of thumb has come about somewhat as a necessity when the core members of SidM first took over the building in Pieter de Raadstraat 35–37: “Mark and Ana and me,” Vollaard recollected, “were already thinking about common spaces, shared spaces, etc. We could not, even if we wanted to, refurbish them as living spaces but we didn't want to either. We got it for free, at least we could share it with everybody.” A microbrewery and a launderette were the first projects to be launched, with the idea of open space to become central in any SidM's commoning practice.

On the other hand, the higher floors–around 70% of the building–are turned into living or working spaces to be rented out at low affordable prices, which in turn constitute the cashflow for running the whole project in a financially self-sufficient way: “we decided [that] for the basic running of things we shouldn't have any subsidy. It should pay for itself,” Jutten said, to which Vollaard added that “each of these properties must be financially autonomous on their own terms.” This ties more directly to the economic sustainability of each project (principle 5). In fact, what constitutes “affordable rent” is context-specific and bargained on a project-by-project basis: for SidM it fluctuates between 100 and 300 euros (bills included), depending on duration, availability of spaces within the building(s), conditions of the building(s). Most importantly from a social perspective, these spaces are refurbished by the occupants themselves in a lean way, i.e., on a on-need basis and by using wasted materials. According to one of the participants of Pension Almonde, it was the presence of the common spaces that enabled people to come together, talk, and organize collective activities: “because those spaces were open not only to the community but also to external citizens, it always attracted interesting people. Nice projects originated from that (i.e., no-waste dinner or the sauna's construction).” While there is little doubt that these housing projects are economically self-sufficient and socially relevant–the alternative being devalued empty properties–the way in which spaces are refurbished turns out to be problematic from an environmental perspective. Resorting to waste materials works often just as a “fix”, but does not really improve the footprint that the building–usually in need of infrastructural renovation–has on the environment. This is acknowledged by Vollaard and Jutten themselves who noted that:

Right from the beginning, out of necessity, we have reused materials. We are very circular in that sense. (...) What we cannot do is, say, increase or decrease our energy consumption because we need money to invest. If we have these spaces on a temporary basis we can never have a return in our investment in such a short period.

At stake, clearly, is not a matter of will but of possibility to be environmentally sustainable. From this passage emerges, more broadly, that the intrinsic temporariness of SidM's projects impairs long-term planning and sustainable practices. On a smaller scale, temporariness also shapes the organization and governance of Pension Almonde and Vlaardingen Commons, which pertain more strictly to principles 6 and 7.

Pension Almonde is an experience that lasted roughly 16 months. Despite the fact that the project evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic, at a time of extreme need, the organizers and participants knew from the beginning of its limited lifespan. Volont (2020) writes that, with the fading away of the economic crisis, at each new occupation SidM “witnessed how its allotted timespans declined to 5, 4, 3 years, even up to two.” Vollaard and Jutten explained how the chance to occupy the 52 properties in Almondestraat came about, as well as their concerns about the feasibility of the project:

Havensteder said, well, you know, 5 years ago we had a problem [economic crisis] and you were a solution, but the problem is gone. [...] We now have the problem of, let's say, when we do urban renewal, we have this sort of transition period before we can demolish and build anew... we don't want to board buildings up, so are you willing to manage such a period for an entire street? [...] Should we do this? It is a way too short period to build a community in the street… but on the other hand we always said that what we are doing here… can only have significance if it can be scaled up or replicated by others. This was a chance.

These words underline two separate yet complementary issues. On the one hand, SidM adapts to the changing situation, operating as a sort of filler of the (economic-institutional) gaps left by both the market and the public sector. In this sense, its activities might be considered as subservient to the continuation of the neoliberal paradigm. On the other hand, however, one can also see in this adaptive strategy SidM's strength as an organization with a social purpose, in that it has the ability to leverage upon the evolving scenario, by bargaining the projects' timespan with their replicability and scalability (with Pension Almonde being a bigger project then the one in Pieter de Raadstraat 35–37, but likely shorter than Vlaardingen Commons). As soon as the negotiation was over and the first people were moving in the flats of Pension Almonde, SidM took a role of enabler, giving space to the inhabitants to self-organize and use the spaces available in the way they felt most appropriate.

Beyond that, the temporariness of the project inevitably had a reflection in the way the whole experience in Almondestraat was set up, from the recruitment of occupants, to the financial bookkeeping, and its social governance. Again, the comparison with the experience in Pieter de Raadstraat 35–37 frames the issue at stake:

Here [Pieter de Raandstraat 35–37], the common uses came out organically. [...] There [Pension Almonde], we, let's say, injected these kinds of things. [...] It was such a short time that all the financial administration behind all the sociocratic setup, we helped them plan and budget their roles and then we based the administration on that.

To speak of “injection” reveals the extent to which the project's temporariness begged for a streamlining of both its governance and the commoning practice, relying on already-acquired expertise and a network of practitioners and activists. As stated by one interviewee, who took part in Pension Almonde: “because SidM is offering not only housing spaces but also knowledge and an initial structure on which the community can build upon, it has helped these communities to take shape and organize despite their temporary existence. Temporariness becomes simply a frame in which people operate.”

The above passage by Vollaard, however, also reveals the organizational model SidM adheres to and strives to enact. Sociocracy implies, on the one hand, the distribution of human resources to autonomous tasks, based on each one's competencies and skills; on the other hand, a consent-based decisional process (through non-objection) involving the whole community. So, while it is true that Pension Almonde's temporary nature required a “pull” from the top, once launched the project was able to stand on its feet. As one interviewee specified: “streamlining is never static. If one of the governance practices is not adhering to the community, SidM leaves space to the community to experiment or adopt new practices.” This is the case of the initial decision-making structure organized in circles in Pension Almonde, transformed in a later stage in a community assembly operating according to sociocratic principles.”

It is the intention of the organizers to further elaborate the sociocratic model in the progressing Vlaardingen Commons experiment, especially promoting a higher degree of self-organization for the participants. This is possible because, on the one hand, some people who animated Pension Almonde moved to Vlaardingen Commons, thus bringing with them expertise and know-how which can be put to the service of the new experience. On the other hand, since the project in Vlaardingen is expected to last longer, it will likely have more time-related room for the development of self-organizing practices.

From here, we arrive to discuss the last principle of SidM: “on our own terms, on our own strength.” This principle can be read in three different ways. Concerning the self-organization of the projects, this principle reasserts (the strive for) self-sufficiency, especially socio-economical. In this respect, it is worth noting that Vollaard, while stressing the need for each project to be autonomous, also pointed to the interconnectedness among all projects, coining the slogan “autonomous on your own, but part of a larger sharing community.” This recalls the idea of “mutualisation” that is also a core principle of Communa, as it will be discussed below.

Secondly, concerning the role of SidM as an intermediary actor between the occupants and the buildings' owner, the principle implies a statuary–albeit minimal–relation between SidM and the occupants. This means that SidM, as an intermediary actor, is endowed with the drafting and abiding to of rental agreements, also on a temporary basis. It remains contentious if these agreements constitute a “commons fix” (De Angelis, 2013) prefiguration that constraints or enables the emergence of the commoning practice. For instance, in the case of Vlaardingen Commons the contracts represent an enabler of commoning practices (i.e., by defining all the backyard gardens of the flats as a common space) as well as a constraint for the people already living in those houses, who found themselves having to accept the commonzing of their backyard and the participation (active or passive) in the community. Nonetheless, it is quite safe to suggest that, insofar as such agreements enable by framing, they represent at least a preliminary condition for this kind of temporary interventions.

Thirdly, the last principle bears a political taintness, which pertains more strictly to the relation between SidM and other (institutional) public and private actors. To claim the willingness to act “on our own terms, on our own strength” entails a strive for operational autonomy within the housing market which goes against those actors responsible for the speculation and enclosure of urban spaces. On this, SidM's founders have quite a radical position:

Vollaard: We think these objects, this real estate is ours. It's us, the people. What they are doing… What the municipality does is dealing with it as if it were their own assets…so they sell it to us, our property is sold to us against market prices. That is really idiotic.

Jutten: …and because we cannot buy it, they sell it to the market… but the market doesn't make a better city or cheaper city.

Vollaard: The right-wing parties here say “Rotterdam is a poor city, too many poor people, so what we're going to do is to invite people with money here.” But hey, that's totally the other way around. You have to deal with your own people, so deal with the poor, create more cheap housing. [Instead] Our minister for housing 10 years ago went to foreign real estate markets to promote the sale of Dutch social housing.

Here we come full circle with the discussion introduced at the beginning about the attempt to cooperatively own buildings in order to have a long-lasting impact on citymaking. While SidM has been trying to bid for empty buildings that might guarantee to walk such a path, so far it has not been successful. The reason has to do in part with the prohibitive selling costs of these properties, which often end up in the hands of anti-squat companies with more financial leveraging power. Discussions are ongoing within SidM on how to take over these anti-squat contracts, especially from the municipality, as a way to scale up without necessarily getting institutionalized. At the core, however, the issue remains political in the strict sense of the term: in times of crisis “we were the solution for the institutions and the government, but we are now the problem, always. We are too activistic [sic],” Jutten argued. At the same time, as Vollaard noted, “to deal with the city council is often a waste of time for us… it leads nowhere, so we better save time and energy.”

Overall, the recovery of the housing market from the economic crisis has left less room nowadays for SidM to intervene in the citymaking process. While SdiM's adaptation from long-term to short-term temporary projects has proven effective, the move toward cooperative housing, alongside a decentralization of its action to peripheral areas, currently constitute the two main strategies to achieve the durability, scalability (and possibly sustainability) of their projects. But for this to happen, a stronger economic backing alongside a wider network of activists–that is, a socio-financial critical mass–seem necessary.

Communa

The six principles that guide the actions of Communa are each worth discussing as they represent a magnifying lens for understanding the way of the organization to conceive and enact temporary urbanism in Brussels.

The first principle is straightforward: non-profit social housing. This aligns to SidM's idea of sparing properties from speculation and repurposing empty buildings with a social orientation in mind and based on economic self-sufficiency. On this point Zaït clarified “it's not that our initiatives cannot do business… Some are like business, but no-profit oriented.” Even though the principle remains the same as SidM's, the resorting to an economic vocabulary (a common thread in Zaït's interview) taints Communa's vision with a more entrepreneurial ethos. This can also be highlighted in the way of launching and maintaining their projects: while SidM makes affordable housing and the creation of a commoning practice two pillars of their approach (the ? commons ? housing “rule”), Communa adopts a more diversified approach, whereby some buildings are fully destined to housing and others not at all, depending on the features of each building and the necessities of the community that gathers around it. This is well-exemplified by the Buissonnière, one of the earliest buildings occupied by Communa in Brussels's neighborhood of Saint-Gilles, which has now been taken over by the owner for renovation. The project lasted 4 years in total (2018–2021), hosting overall more than 50 initiatives, but it was most active between 2018 and 2019. The building–an old school–was meant to become an open space for the local community, but its configuration consisting of different rooms led to reconceive the project as a space for hosting temporary accommodations in the upper floors and working spaces for artists and cultural associations on the ground floor. One participant, part of a cultural association, explained the process of “recruitment” concerning the Buissonnière: “we answered a call for projects released by Communa, we were selected, and given a space to share with another association.” Another participant, instead, was involved in the Buissonnière directly by Communa on a pro bono basis, due to the fact that the commoning spaces were expected to be taken over by the owner of the building shortly after. In this sense, the role of Communa becomes one of stewardship and facilitation of projects' premises, in different regards.

Firstly, the organization provides the financial frame: “When we start,” Zaït said, “we make a business [plan], we calculate the costs for the whole building. And then we share it with the occupants and let them decide together [how to spread the costs].” This resonates with SidM's approach, especially in the case of Pension Almonde, where the organization “injected” financial-legal expertise into the emerging project. However, while for SidM such decision was driven by the limited timespan of the Pension, with Communa it is more a modus operandi by-default, that is, a preliminary condition to entice the self-organization of the community. Moreover, considering the lending pro bono of a space to a participant, such a way of operating seems to be amendable based on circumstances. “We don't stipulate rents, we have temporary use agreements,” one of Communa's core members specified. “but we cannot depend only on that. (...) Another major source of income is funding: municipal, regional and European, and then we rely on donations.”

With the financial frame also comes the legal frame and here again the parallelism between SidM and Communa fits to a certain extent. Communa, similarly to SidM, acts as a trusted intermediary between the building's owner and the occupants, thus agreeing on temporary rental conditions; and yet, the space for the emergence of self-organized commoning practices is here subjected to an enframing approach. Epitomizing are Zaït's words, who said: “there is a community in each building where they take decisions, [but] they don't decide about everything. It's not auto-gestion, it's not fully self-managed.” Beyond what can and cannot be done, the interesting point to signal is the shift from the idea of (lean) self-organization of the community and by the community to one of (controlled) self-management, which entails both ongoing external supervision and the (discursive) treating of commoning as a semi-entrepreneurial activity. Interviewed participants further unpacked this issue, presenting partially diverging views. On the one hand, two participants speaking of the project at Tri Postal said that “the idea behind Communa is vaguely communitarian, but on fundamental issues, either practical or relational, they are strict: it's ‘either you do as we say or you go.”' In a building like Tri Postal (whose experience ended in March 2022 at the time of our interviews), which consists of a 1320 square-meter open ground floor space owned by Belge railway company SNCB next to Brussels South Station, this approach has led to some tensions (and security issues), since the space was first reclaimed by the local community and then managed by Communa, which organized there various events alongside the hosted associations. On the other hand, a participant involved in Maxima mentioned the need for more coordination among the various initiatives hosted in the building and the conjoint “moderation” by Communa in the structuring of such coordination. So, Communa finds a thin line to walk for its activity, being required to balance openness toward participants' voices and the need for a more structured presence in loco to synthetize these same voices.

Secondly, Communa also provides help to the infrastructuring of the occupied buildings. This marks a substantial difference with SidM: what is at stake is no longer a do-it-yourself approach to the refurbishment of spaces, but a loosely planned renovation. To do this, occupants can count on Communa's “technical team” whose function is to provide assistance (regulatory and in the recuperation of wasted materials), as well as a workforce coming from social services dedicated to reinsert disadvantaged people in society. While the goal is always to be as socio-economically sustainable as possible, once again this signals a streamlining of the commoning practice that inscribes itself into an entrepreneurial logic. Practical daily issues, however, remain on the table: one interviewee said that the coordination across all participants for guaranteeing the maintenance of common spaces is an enduring difficulty, signaling that the commoning as a practice would require “2–3 years to build.”

The second principle is “mutualisation,” which means the idea of stimulating synergies among the various projects in the occupied buildings administered to Communa. We have seen this also in SidM: mutualisation can be seen as a way to scale wide, by transferring knowledge, expertise, material support as well as social networks, while maintaining the independence in each project's premises. It is a whole ecosystem that is being fostered and in this process timely proactiveness and mutual help play a crucial role. On this point, however, interviewed participants have a more nuanced first-hand opinion. One participant, for instance, specified that, “although the spirit is collaborative and gives participants the opportunity to reach out to others […] Communa is more an auto-celebratory exercise than an ecosystem…” These words pair with the entrepreneurial ethos surrounding Communa which tends to carve for itself a branded niche as a managerial housing intermediary, more than a commoning enabler. Another participant from Maxima–an ongoing community-centered project hosting various initiatives since 2019 for the people of the neighborhood of Forest, after the company Axime left the 6,000 square meter building vacant in 2017–acknowledged that the commoning as a mutualized practice remains more of a wish than a reality, due to a certain distance of Communa from what happens in the buildings: “despite they [Communa] make a huge effort… it's all messy… I really believe that the best people to manage these spaces are people who already work in a social environment, who deal with social diversity and are directly involved with the commune.” The importance of the “human factor” and its correct management was also stressed by one core member of Communa: “we had a burnout in the team… we could add more people if we had more money… Dealing with people is the most difficult thing and it requires care.” So, while Communa strives for a controlled supervision of how the buildings are commonized, this does not directly translate into either smooth self-management or networked coordination.

The third principle is “durability” and might be regarded as a form of scaling through (time). Durability has to do with Communa's effort to find avenues for keeping all the various projects going, which also implies to remain in control of the occupied buildings. The chosen path is very similar to what SidM has been trying to achieve, notably cooperative housing/ownership:

We created a cooperative called Fair Ground Brussels with ten other organizations from the region to be able to buy out our buildings and to remain [there]… So we managed to raise two millions and we bought already three places… Basically our technique was to work with bigger organizations than us. They know how to do the job…We are like the little fish, you know, stuck on the shark, for the moment.

Over the last 2 years, Communa has been able to collaborate with partner organizations, including Brussels's Community Land Trust, to enact a cooperative housing process that has eventually put the organization in control of three buildings. This achievement represents both a scaling through as much as a scaling wide and up to the extent to which–as Zaït explained–Communa entered into a wider network of similar and bigger actors.

This leads to discussing principles five and six: “spreadability” and “institutionalization.” At the core of spreadability lies the idea to disseminate Communa's projects and its modus operandi in two complementary ways: via training and the reaching of varied audiences. Concerning training, we return to the role of the organization as a facilitator of temporary urbanism: “We're not only directly managing buildings, but I will also help other people to do it through bottom up training. Young organizations want to get it. Boom. We train them. We give them the starter toolkit.” It is interesting to note how Zaït considers as “bottom-up” a process of knowledge transfer which basically sees Communa as the active enabler and the communities as recipients of know-how and toolkits; on the other hand, “top-down” are those disseminating initiatives that involve “conferences, academics, but also working with the state or the region… Push the practice for them, expertise wise, I mean.” On this point, a core member further specified that consultancy is one cash-in avenue, among others, to sustain the organization: “we sell our work, our expertise to public authorities outside of Brussels, which have issues with vacant places.” Here it is not difficult to detect a professionalization of the role of Communa, which goes hand in hand with the entrepreneurial logic highlighted above. In fact over its 5 years of existence Communa has gone from being a small non-profit, totally voluntarily-based organization to a professional one with 20 workers: “we have started to professionalize Communa through the business school in Brussels,” Zaït noted, “it works and we're about to reach the break-even.” This is confirmed by a participant from Maxima who claimed that “they are really growing now” leading to both a consolidation of the organization and an operationalisation of its principles.

The pragmatic ethos surrounding Communa finds a reflection in how the organization manages its decisional process. If, on the one hand, the board of 20 members resorts to a consent-based sociocratic approach when it comes to strategic decisions concerning the course of action of the organization, on the other hand, it adopts an advisory model for running weekly affairs. This means that an horizontal advisory process is established among the board members, but some verticality is being implemented when it comes to tactical choices, although the autonomy among the tasks is maintained. “It's challenging, because it requires a lot of care for each other…but it is also a development process (...) and it's fun, playful [insouciant in French],” one of Communa's core members noted. This revisitation of the sociocratic approach is due to Communa's growth, which has required exploring more effective ways to make decisions: “if we want to be able to scale,” Zaït summarized, “to go from social innovation, to public policy, then we need to be good. (…) We're not fighting against efficiency… we're fighting against the efficiency of destroying the planet by gathering more capital.” Although being born out of the squat movement, Communa has embraced a rationalization of temporary urbanism; this shift is seen by the members as a means toward the realization of Communa's broader mission as a social actor in social cooperative housing. In this regard, when speaking of Toestand, a Flemish similar initiative working in Brussels, one core member stressed that “they managed to remain activists in an anti-capitalist style (...) and the power structure is in the hands of the volunteers… but when the public authorities think of temporary use, they think of us rather than Toestand… This is probably because we are more organized.”

In this sense, spreadability, professionalization, and institutionalization are three interlaced principles, and concerning the latter Communa's members are aware to walk a thin line. Brussels is a composite urban dimension: there are state authorities, regional authorities, municipal authorities, as well as para-public stakeholders, private actors and non-institutional actors. This varied composition entices and demands, to an organization like Communa, the reaching out toward alike actors to avoid the risk of being either co-opted by the market or buried by bureaucracy. And yet, the relations with public authorities is not a smooth one: “they see the potential in what we do… but many of them are always trying to make it more commercial… it's still like a bit tense,” Zaït acknowledged. The third way to go between the market and the state is illustrated in a report by Vanwelde (2018) accessible on Communa's website, titled: “L'occupation temporaire sera-t-elle associationniste?” (“Will temporary occupation become associationist?”) In here, it is discussed the possibility of a “positive institutionalization” that, while recognizing and legitimizing de facto and de iure the social role and function of organizations like Communa, creates a flexible legal framework for their experimentation. Notably, this means “a frame that accommodates the specificities of social organizations, in order to foster a perspective not only “associative” but “associationist,” that is, carrying a “project of democratization of society led through collective actions, free and voluntary, and striving for equality.” In order words, at stake is the legitimization of temporary urbanism as an instituted practice with/in and through today's actors and boundaries. It is in this sense that the words by one core member can be interpreted, when asked about Communa's future: “the idea would be to own an entire neighborhood as a coop. (...) It's a matter of time and learning.” This echoes with the idea of open and heteroglossic citymaking: to do so, the quoted paper openly calls for “the recognition of a right to experimentation” which entails the softening and loosing of existing legal barriers for actors with a recognized associationist function.”

Overall, it emerges more clearly that Communa has grown well-beyond its primordial raison d'être as a collective enacting temporary urban interventions, to become a “wanna-be institutional actor” which both diversifies its roles when involved in the citymaking process–steward, facilitator, enabler–and claims a voice for itself and associationism in the redefinition of the legal rules impacting urban commons projects.

Extrapolating (Non)Institutional Commoning Dynamics

In the article we explored the role of two non-institutional actors involved in temporary urbanism interventions in Rotterdam and Brussels and how they manage to enact commoning practices that contribute to citymaking.

The interviews that we conducted with founders and core members of SidM and Communa, as well as with participants to their projects, showed that these non-profit organizations can help negotiate and fill the gaps between the market, public actors and social housing companies, when it comes to connecting locals' needs for accommodations and social spaces with the provision of vacant properties that especially the economic crisis has brought with itself. SidM and Communa do so by opening up spaces for non-institutionalized initiatives which facilitate the disclosure and social-oriented reappropriation of empty properties, regardless of the temporariness of these projects. Their actions then configure the (temporary) repurposing of urban resources via mechanisms that cut through the market, as well as institutionalized actors.

Beyond this general frame, SidM and Communa have different ways of enacting their intermediary role and carving for themselves a niche in the citymaking process. In terms of internal governance, SidM depends upon the decisions of its founders; Communa, instead, has grown (and will likely grow) to include a consistent number of core members beyond the founders, thus leading to a more complex structure that demands a revisitation of sociocratic decisional processes.

Concerning the organization of the projects, SidM appears to work as a trigger/assistant for the launch and upkeep of each project, with the future goal to leave increasing autonomy to the communities. Communa, on the other hand, has a more diversified role: it works, at once, as a provider/facilitator/consultant for its spaces and projects, organizing activities and offering training also to institutional actors.

From the interviews, it emerged that for both organizations time is a crucial factor for the empowerment of participants: the more an experience lasts, the easier it is for it to become fully autonomous in the unfolding of commoning practices. In this respect, it is safe to say that both organizations create socio-economic value in the short/mid-term. By contrast, the more temporarily a project is, the more it needs support in terms of knowledge and resources from the organizations.

To be different in the two organizations is the underpinning business model: SidM has a return mainly from rents; Communa has diversified its sources of support, from donations, to grants, as well as a cashflow coming from communal activities. This also means that the projects of these organizations tend to bifurcate as either temporary or transitional, to the extent to which the introduced practice can or cannot prefigure further commoning. Whilst the legal recognition of social temporary use of vacant spaces can outright set up the practice as transformative, any seized space embeds a form of innovation capital for those involved. The moment such spaces stop being an arena for social change in an urban context, little difference remains from traditional, institutionalized forms of social housing.

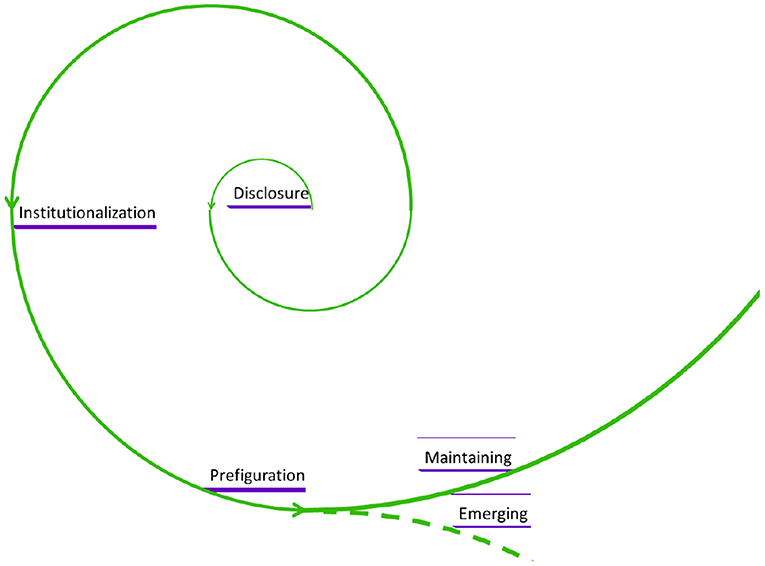

From a commoning perspective, both organizations have sought an active role in enlarging or replicating the practice of intermediation for the sake of both social use and community building, allowing for others to negotiate their own terms. Within such a frame, both organizations prefigure ways for communities to emerge, either through the facilitation of a sharing agreement or by making space available for communal use. Room for autonomy is in this way disclosed to commoners; most importantly, commoning as a practice does not set any privileged point of entry to any actor. Paradoxically, however, the formalization of such enabling procedures can itself become a form of (collective) enclosure. The iterative process of reconfiguration of the urban commons is then imperative. Past the necessary access points for decision-making, the commons needs to be disclosed, yet again; past the commoners of yesterday, the city needs to be shared, again and again. This is what makes citymaking an iterative and open process. When it comes to the limited replicability of urban commons initiatives denounced in existing literature, then, it is the legal frameworks that (dis)enable the commoning as a practice that should be the focus of attention, not much its specific instantiations. How to make and keep citymaking open through continuous practice? This is how the call by various Belgian social actors to the right to experimentation shall be interpreted. Similarly, the (supposed) co-optation of temporary urban interventions by the neoliberal imperative can be more constructively read through the lens of heteroglossic power relations between normative and non-normative citymaking practices and actors, all of which presuppose each other and yet don't have, at present, equal recognition. In this sense, we propose a generative cycle of disclosure that reconsiders further forms of commoning, as depicted in Figure 1.

As soon as an urban resource is disclosed, it begs for cooperation among both institutional and non-institutional actors for the prefiguration of commoning. This can then lead to forms of emerging self-organization or more canonized practices, regardless of the kind of intervention enacted, but it is crucial that all actors are warranted equal recognition and space for action. It is from here onwards that a re-disclosure and de-institutionalization is needed: as Jacobs noted (1969, p. 90), the development of the city is “a messy, time- and energy-consuming business of trial and error and failure.” In this messiness, institutional actors cannot do without non-institutional ones, and vice-versa. Past the idea of an enabling state as one of the three pillars of urban commons, it is the co-presence of different actors, all as enablers of commoning projects, that must gain prominence. For non-institutional actors, then, at stake is the challenge of finding recognition and legitimization even beyond any institutionalization.

Crucially, in order for both SidM and Communa to become a structural pillar of the citymaking process, within and beyond the temporariness of their interventions, they need to consolidate their practices both internally and externally. This entails especially (1) the fostering of a robust network of collaborators; (2) the success in collectively owning buildings. Concerning the first point, our research showed that SidM adopts a rather radical approach because its founders consider the dialogue with institutional actors as a very perilous path; as for Communa, despite (or maybe because of) having grown rapidly, both founders and participants remarked the need for a wider community aggregating around the organization to stabilize its projects.

The second point is shared by both organizations but while, so far, Communa has managed to successfully bid for buildings by cooperating with other similar and bigger actors, SidM has still to find its way through. This might also have to do with the fact that the availability of vacant buildings in Rotterdam has diminished sensibly in the last few years, pushing the organization to experiment in the outskirts of the city.

Limitations And Further Research

We are aware of the limitations of this research, especially concerning the scope of the comparative analysis. Further research could follow three complementary paths. First, research could provide a longitudinal exploration of the evolution of the organizations under exam and their projects, highlighting if/how the principles guiding SidM and Communa have changed over time and, alongside, how the commoning practices have been differently enacted. Second, research could strive to expand the cohort of compared cases, including, for instance (as mentioned by one interviewee), the non-profit organization Toestand, involved in temporary urbanism interventions in Brussels and whose operating logic seems closer to that of SidM. Third, research could look back at the concluded projects of these organizations for delivering an assessment of their socio-economic impact on the local communities involved in the mid-long term.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ajuntament de Barcelona (2019). Available online at: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/en/digital-transformation/city-data-commons (accessed April 30, 2022).

Anastasopoulos, N.. (2020). “Commoning the urban”, in The Handbook of Peer Production, eds M. O'Neil, C. Pentzold, and S. Toupin, (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons), 268–281. doi: 10.1002/9781119537151.ch20

Bangratz, M., and Förster, A. (2021). Local data and global ideas: citymaking in times of digital transformation. PND. doi: 10.18154/RWTH-2021-10411

Botha, L.. (2019). Basic space: establishing a diverse economy of urban living (MA thesis). Sheffield: Faculty of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

Brinkley, C.. (2019). ‘Hardin's imagined tragedy is pig shit: a call for planning to recenter the commons. Plan. Theory 19, 127–144. doi: 10.1177/1473095218820460

Cazacu, S., Hansen, N. B., and Schouten, B. (2020). Empowerment approaches in digital civics. Proc. OzChi 20, 692–699. doi: 10.1145/3441000.3441069

Communa (2022). Communa: faciliter l'urbanisme temporaire à finalité sociale. Available online at: https://communa.be/"> (accessed April 30, 2022).

Comune di Bologna Urban Data Center (2014). Collaborare a Bologna. Available online at: http://www.comune.bologna.it/collaborarebologna/collaborare/"> (accessed April 30, 2022).

Czischke, D., Gruis, V., and Mullins, D. (2012). Conceptualising social enterprise in housing organisations. Housing Stud. 27, 418–437. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2012.677017

De Angelis, M.. (2007). Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

De Angelis, M.. (2013). Does capital need a commons fix? Ephemera Theory Polit. Organiz. 13, 603–615. Available online at: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/contribution/does-capital-need-commons-fix (accessed June 22, 2022).

De Biase, A., and Mattiucci, C. (2020). After temporary: a generic and standardized temporariness. Lo Squaderno 55, 4–6. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/43539524/Lo_Squaderno_55_After_Temporary (accessed June 22, 2022).

De Lange, M.. (2019). “The right to the datafied city: interfacing the urban data commons,” in The Right to the Smart City, eds P. Cardullo, C. Di Feliciantonio, and R. Kitchin (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited) 71–84. doi: 10.1108/978-1-78769-139-120191005

De Lange, M., and De Waal, M. (2019). The Hackable City: Digital Media and Collaborative City-Making in the Network Society. Singapore: Springer.

De Nictolis, E., and Iaione, C. (2021). “The city as a commons reloaded: from the urban commons to co-cities empirical evidence on the Bologna regulation,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Commons Research Innovation, eds S. Foster, and C. Swiney (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 124–137.

Dellenbaugh, M., Kip, M., Bieniok, M., Schwegmann, M., and Müller, A. (2015). Urban Commons: Moving Beyond State and Market. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag.

Dellenbaugh-Losse, M., Zimmermann, N. E., and de Vries, N. (2020). The Urban Commons Cookbook: Strategies and Insights for Creating and Maintaining Urban Commons. Available online at: http://urbancommonscookbook.com/#:~:text=The%20core%20of%20The%20Urban ,they%20employed%20to%20surmount%20them (accessed April 30, 2022).

Ellis, C.. (2004). The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel About Autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Feinberg, A., Ghorbani, A., and Herder, P. (2021). Diversity and challenges of the urban commons: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Commons 15, 1–20. doi: 10.5334/ijc.1033

Ferreri, M.. (2015). The seductions of temporary urbanism. Ephemera 15, 181–191. Available online at: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/contribution/seductions-temporary-urbanism (accessed June 22, 2022).

Foster, S. R., and Iaione, C. (2019). “Ostrom in the city: design principles and practices for the urban commons,” in Routledge Handbook of the Study of the Commons, eds B. Hudson, J. Rosenbloom, and D. Cole (London: Routledge), 235–255.

Hardin, G.. (2009). The tragedy of the commons. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 1, 243–253. doi: 10.1080/19390450903037302

Huron, A.. (2015). Working with strangers in saturated space: reclaiming and maintaining the urban commons. Antipode 47, 963–979. doi: 10.1111/anti.12141

Iaione, C.. (2016). The CO-city: sharing, collaborating, cooperating, and commoning in the city. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 75, 415–455. doi: 10.1111/ajes.12145

Lang, R., Carriou, C., and Czischke, D. (2020). Collaborative housing research (1990–2017): a systematic review and thematic analysis of the field. Housing Theory Soc. 37, 10–39. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2018.1536077

O'Neil, M., Pentzold, C., and Toupin, S. (2021). The Handbook of Peer Production. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Ostrom, E.. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E.. (2010). Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 641–672. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.3.641

Stad in de Maak (2022). City in the Making: New Urbanity/Unconventional Resurrection Management. Available online at: https://www.stadindemaak.nl/en/">https://www.stadindemaak.nl/en/ (accessed April 30, 2022).

Urban Catalyst (2007). Urban Pioneers. Temporary Use and Urban Development in Berlin. Berlin: Jovis Verlag.

Vanwelde, M.. (2018). Loccupation temporaire sera-t-elle associationniste? Available online at: https://saw-b.be/wp-content/uploads/sites/39/2020/05/a1808_l_occupation_temporaire_sera-t-elle_associationniste.pdf (accessed April 30, 2022).

Vollaard, P.. (2020). Out There a Change was Going to Come, Architectuul. Available online at: https://blog.architectuul.com/post/655574528366362624/out-there-a-change-was-going-to-come/amp (accessed April 30, 2022).

Volont, L.-H.. (2020). Shapeshifting: the cultural production of common space. (PhD thesis). Antwerp: Faculty of Social Sciences, Antwerp University.

Wikipedia (2022a). Rotterdam. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotterdam (accessed April 30, 2022).

Wikipedia (2022b). Brussels. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brussels (accessed April 30, 2022).

Appendix

Questions to organizations' members

1. How was the organization born? How has it developed? What were/are its objectives?

2. Who/how many are the people involved (e.g., socio-demographically speaking, as well as in terms of expertise composition, and/or the presence of stable members and other periodical participants)?

3. Is the organization economically sustainable? If so, how is this achieved?

4. How does politics (e.g., presence or lack of political support) impact on the organization activities?

5. What kind of public-private synergies have been developed? How are the relations with other actors/organizations established and maintained?

6. Has the organization received institutional backing since its inception or at any point during its life? If so, how/in which form? From whom/which organization? If no, why not (e.g., was a conscious decision)?

7. How do you involve/link to the local community (e.g., neighborhood; interested people from across the whole city; etc.)

8. What makes the organization different from/similar to others? Are you in contact with other similar initiatives.

9. How is the organization internally organized (e.g., specific roles of the members, working groups, horizontal/vertical decisional processes, etc.)? How are potential barriers tackled?

10. How does the organization identify the urban interventions to accomplish?

Questions to initiatives' participants

1. How was the initiative born? How has it developed? What were/are its objectives?

2. When have you joined the inVitiative? What was/is your role?

3. Who/how many are the people involved (e.g., socio-demographically speaking, as well as in terms of expertise composition)?

4. Is the initiative economically sustainable? If so, how is this achieved? How does the initiative organize its budget?

5. Does the initiative have any institutional support? If yes, how? By whom? If not, why?

6. How is the initiative internally organized (e.g., specific roles for the participants, working groups, horizontal/vertical decisional processes, etc.)? What are the main organizational barriers? How are they tackled?

7. How does the initiative address/embed social and cultural issues (e.g., how does the initiative identify the urban interventions to accomplish; is there some sort of participative pooling of ideas, or set of priorities/principles)?

8. How does the initiative share the knowledge created internally and externally (if this happens)?

9. Is the initiative replicable? Is there such ambition? If so, where and how? If not, why?

10. What makes the initiative different from/similar to others? Are you in contact with similar initiatives in the city/country and/or internationally.

Keywords: urban commons, temporary urbanism, non-institutional actors, social housing, real estate market, Rotterdam, Brussels

Citation: Calzati S, Santos F and Casarola G (2022) On the (Non)Institutional Disclosure of Urban Commons: Evidence, Practices and Challenges From the Netherlands and Belgium. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:934604. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.934604