- Department of Management in the Built Environment (MBE), Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands

For young adults on the Amsterdam housing market the accessibility of housing has been decreasing for years, due to soaring house prices and rents, the shrinkage and residualization of the social rental sector, and the precarization of the labor market. Consequently, many young people struggle to secure an affordable and adequate dwelling and are stuck in insecure and chaotic housing pathways. Current housing policies in Amsterdam are struggling to effectively respond to these challenges. In an effort to better understand and address the specific housing problems of young people, the Municipality of Amsterdam, housing association Lieven de Key, resident organization !Woon, Delft University of Technology and a group of local young people have started a co-creation process within the framework of the H2020 UPLIFT project. The goal of this co-creation process is to unravel the real-life experiences of young people and to co-create new or improved policy initiatives with them. This paper examines the results of said policy co-creation process in order to evaluate its methodology as well as its impact on the participating actors - young people in particular - and on the policymaking approach. We analyze the benefits and limits of this type of participatory practice in addressing housing issues and try to draw conclusions on its applicability in a larger context.

1. Introduction

Current youth policies are often created top-down and insufficiently take into account the real needs and strategies of the target group. Or, to put it in Habermasian terms, there is a significant gap between the system world of institutions and professionals, and the life world of the young people themselves. This paper shows that by directly involving young people in the policy-making process, this gap can be bridged, and sustainable youth policies that genuinely reflect the voice and needs of young people can potentially be created.

Our contribution is a spin-off of the H2020 UPLIFT project1. UPLIFT focuses on inequality and vulnerability, with a special emphasis on the younger generations. Within the project, inequality is mapped and drivers of inequality are identified. Moreover, solutions for increasing the life chances and opportunities of young people (aged between 16 and 29) are sought for. For the latter purpose, co-creation trajectories with young people have been started in four European cities: Amsterdam, Tallinn, Sfântu Gheorghe, and Barakaldo.

This paper will analyze how this process has worked out in the city of Amsterdam. As Section 2 will show, this city is suffering from a serious housing crisis that particularly affects young adults. To some extent, this crisis is caused by non-local factors (international economy, national policies) that cannot be influenced directly by local stakeholders such as the municipality and the local housing associations. Nevertheless, these stakeholders can certainly make an impact, since they are responsible for local agreements in the field of housing production (how many and what types of houses are built?), housing allocation (who is entitled to what type of housing?), and information provision. By involving the target group of young people in the formulation of local youth housing policies and initiatives, the participating local stakeholders hope to come to more effective housing policy responses that are rooted in the real experiences of young people and tailored to the local context. In the longer run, the ambition is to come to a new format for policy creation that is based on durable collaboration between policy makers on the one hand, and policy recipients on the other hand.

This paper will analyze the benefits and limits of this type of participatory practice and assess its potential for a more generalized application. More specifically, we address the following research questions:

1. What institutional arrangements are necessary in order to come to a successful co-creation process with young people?

2. How to set up a balanced and inclusive Youth Board that represents the voice of young people during the co-creation process?

3. How can the co-creation process be structured and moderated, and what is needed to make this process as successful as possible?

4. What is the (expected) impact and follow-up of the co-creation process and what can be done to optimize this impact and the chances of implementation of the outcomes of the co-creation process?

The paper starts with a brief literature review (Section 2), which outlines the housing market situation in Amsterdam, as well as the theoretical principles behind the co-creation process. Section 3 outlines the general research approach, in which we distinguish four different phases. Section 4 contains a deeper description of, and reflection on, what has happened in each of these phases. In Section 5, we summarize our main findings and we formulate a number of critical conditions for carrying out a successful co-creation process.

2. Literature review

Section 2.1 provides a brief description of the housing market and housing policy context in the city of Amsterdam. This Section is based on Gentili and Hoekstra (2022), in which more extensive information on this topic is provided. Section 2.2 briefly introduces the theoretical insights that underpin the co-creation process. Also here, we refer to other UPLIFT deliverables (Hoekstra and Gentili, 2021).

2.1. Housing market and housing policy context in Amsterdam

2.1.1. The Amsterdam housing market

Recently, the concept of a global urban affordability crisis has gained momentum in academic housing research. As a result of megatrends such as financialization, urbanization, gentrification and neo-liberalization, urban housing has become less affordable and accessible in big cities across the world (Wetzstein, 2017; Haffner and Hulse, 2021). This has resulted in increasing inequality: between deprived and gentrified areas, between home owners and tenants, and between younger and older generations.

The above trends are also very visible in the housing market of Amsterdam. This capital city, traditionally known for its large share of social rental dwellings, has experienced a trend of commodification and financialization. Due to its central position, good facilities and strong economic base, Amsterdam has become very popular among both house seekers and investors (Gentili and Hoekstra, 2022). This has resulted in a large shortage of dwellings and serious housing affordability and accessibility problems, particularly for starters on the housing market (Hochstenbach and Boterman, 2015; Lennartz et al., 2016; Jonkman, 2019; Boelhouwer, 2020).

In the last quarter of 2022, prices in the private rental sector (€25/month per square meter) and the private home ownership sector (€7200 per square meter) were too high for a large majority of young house seekers. Theoretically, the social rental sector could offer an alternative for young adults with a lower to middle income. However, Amsterdam's social rental sector has shrunk considerably in recent years (Kadi and Musterd, 2015) and waiting times have grown to a staggering 13 years (Hochstenbach, 2019). This reflects the general residualisation process that has characterized the Dutch social rental sector since 2010 (Hoekstra, 2017). Furthermore, temporary rental contracts (mostly 2 or 5 years) have been allowed since 2016 in both the private and the social rental sector, thereby seriously reducing the security of households that do manage to find a rental dwelling (Huisman, 2020).

The above problems have several negative consequences, such as a delayed emancipation and a prolonged co-residence of young adults with their parents, high housing costs for those who do reach residential independence and an increased reliance on intergenerational transfers to access homeownership (Lennartz et al., 2016; Arundel and Doling, 2017). Access to homeownership has become a requisite for economic security in later life that sets apart those who can rely on family wealth to better their position from those who cannot (Lennartz et al., 2016; Arundel, 2017). The latter group is often trapped in chaotic and insecure housing pathways (Hochstenbach and Boterman, 2015). They are forced to look for alternative housing options (expensive private rent, home sharing, squatting, living on a camping) or leave the city altogether. The housing problem in Amsterdam is so dire that it also affects the choices that young people make in the field of education, labor market and personal relations. For example, it is increasingly common for young people to delay the end of their studies in order to be able to remain longer in their student accommodation (Gentili and Hoekstra, 2023).

Last but not least, it should be noted that the Amsterdam housing market developments also have a clear spatial component. Due to gentrification, the central city neighborhoods (within the so-called ring road) are increasingly becoming the domain of higher income groups, whereas poorer households (especially those with a migration background) are pushed outside and end up in more peripheral parts of the larger metropolitan area. The accessibility of jobs or education centers from these areas is considerably lower than from Amsterdam itself, while commuting costs are much higher (Gentili and Hoekstra, 2022).

2.1.2. Local policy responses

Dutch national housing policies are not well tailored to combat the inequality on the Amsterdam housing market, and the local housing policies of the city itself are more focused on protecting vulnerable groups. For example, the municipal government applies the 40-40-20 rule for new housing developments. This rule implies that in new housing projects, 40% of the dwellings should be social rent, 40% should be affordable private rent (monthly rent between €763 and €1068) or affordable home ownership (below €325.000)2, and only 20% may have full market prices. Furthermore, in order to temper the negative impact of buy-to-let investments, a so-called self-residence obligation has been introduced in 2022. This obligation states that dwellings with a cadastral value of less than €512.000 may only be sold to people that will not rent out the dwelling in the four years after the sale. Finally, the municipality of Amsterdam has the ambition to give young adults a stronger voice in the housing policy making process. That is one of the reasons why they have decided to participate in the co-creation process that is the topic of this paper.

2.2. Theoretical background of the co-creation process

The UPLIFT co-creation process follows an approach that is called reflexive policy-making. The UPLIFT conceptualization of reflexive policy making connects four different theoretical/methodological approaches: the capability approach, participatory action research, policy-co-creation and reflexivity (see Hoekstra and Gentili, 2020 and 2021 for more information). It has the following features:

• A strong focus on the enhancement of the capabilities of the young people involved in the co-creation endeavor. In order to achieve this, much emphasis is put on capacity building and empowerment;

• A bottom-up co-creation process in which the young people involved have real agency and a sense of ownership, taking into account the principles of participatory action research;

• A strong commitment of the institutional stakeholders to take the input of the young people seriously, reflecting a strong spirit of policy co-creation;

• A continuous dialectical process between young people, institutional stakeholders and academics in order to come to continuous process and content evaluation, following principles of reflexivity.

In short, we have intended to generate an interactive and iterative process in which young people, institutional stakeholders and research practitioners critically assess current housing policy interventions and co-create alternative housing policy options. Compared to more traditional policy co-creation approaches, our approach is more bottom-up, more reflexive and pays more attention to empowerment and knowledge creation for the participants. A crucial role in the co-creation process is reserved for the so-called Youth Board. The Youth Board is a diverse and representative group of young people that is structurally involved in the process of reflexive policy-making.

3. Approach

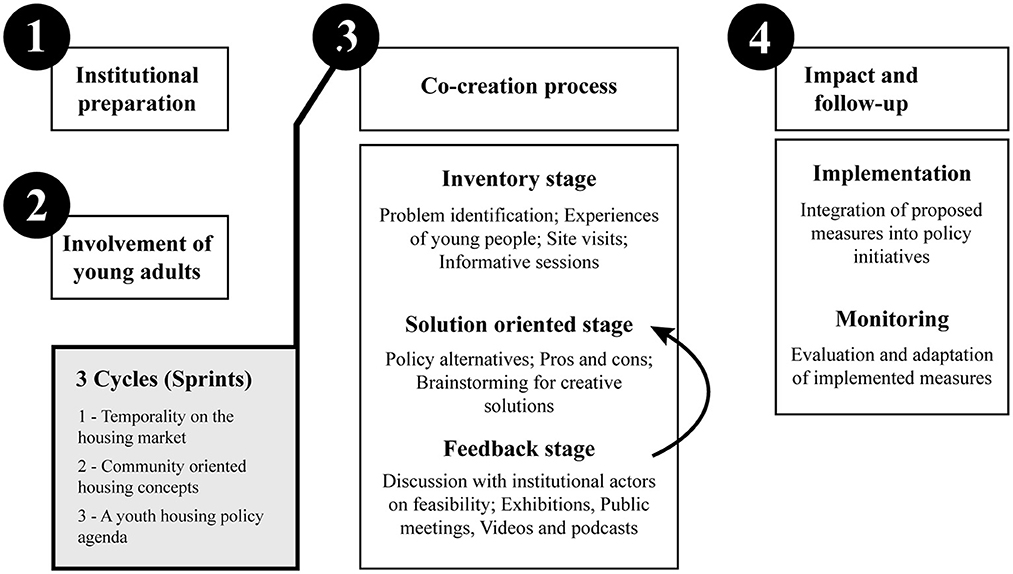

Based on the theoretical notions discussed in Section 2.2, a general methodology for structuring and shaping the co-creation process has been developed by Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) (see Hoekstra and Gentili, 2020, 2021 for more information). Important elements in this approach are the structural and inclusive involvement of a representative group of young people (the so-called Youth Board), a strong commitment of the participating policymakers and implementers, the use of focus groups and other group activities in order to stimulate engagement and creativity, and regular feedback loops between the young people and the policy makers that receive their input. In the methodology, four main steps can be distinguished (see also Figure 1).

1. Preparation of the co-creation process: Institutional arrangements

In this step, the institutional and academic stakeholder network that organizes the co-creation process is set up. The objectives and the focus of the process are determined and the stakeholders involved make agreements on how they will collaborate.

2. Involving young adults in an inclusive manner: The youth board

In the UPLIFT co-creation process, the young people are represented by a so-called Youth Board. In the second step of the co-creation process, decisions with regard to the recruitment, the size and the composition of the Youth Board are taken.

3. Running and moderating the actual co-creation process

Step 3 of our approach - the actual co-creation process - is divided into three stages: an inventory stage, a solution-oriented stage and a feedback stage. For each of these stages, decisions need to be taken with regard to the type and focus of the organized meetings. Furthermore, strategies to keep the Youth Board members engaged and committed, and make the co-creation process as inclusive as possible need to be developed.

4. Assessing the impact and follow-up of the co-creation process

The co-creation process is intended to have an impact at different levels. First of all, it is our aim to empower the participating young people. Second, we intend to change the mind-set of the institutions that are receiving the policy advice of these young people. Third, we strive for a co-creation process that results in a reflexive policy agenda that has the potential to be implemented in practice. And last but not least, we will make an effort to ensure that the collaborative structures that were developed within the framework of UPLIFT will continue after the project funding has ended.

4. Description and evaluation of the co-creation process

This Section describes, analyzes and evaluates the four steps in the Amsterdam co-creation process that were introduced in Section 3. Based on our own impressions as well as on the bilateral inputs that we have received from the institutional stakeholders and young people involved, we reflect on the strong points of the co-creation process as well as on the challenges/pitfalls that we have encountered. This reflection can be seen as an updated version of chapter 4 of Gentili and Hoekstra (2022), in which an interim analysis and evaluation of the first 2 years of the Amsterdam co-creation process was provided. For each of the four steps of the co-creation process, we first describe what has actually happened and then we put forward our reflection and evaluation.

4.1. Preparation of the co-creation process: Institutional arrangements

4.1.1. Involving relevant stakeholders

The original UPLIFT partners for the co-creation process in Amsterdam were housing association Lieven de Key and Delft University of Technology. However, soon after UPLIFT had started, the municipality of Amsterdam also decided to join, because the objectives of UPLIFT clearly matched with their own ambitions of giving young people a stronger voice in housing policy development. The collaboration with the municipality of Amsterdam allowed us to extend the scope and budget for the co-creation project, and it has also enhanced the potential impact of the co-creation activities.

When drafting the action plan for the co-creation activities in the first half of 2020, the three initiators of the co-creation process quickly realized that they lacked the necessary connections to the target group of young people. Therefore, it was decided to involve a so-called gate keeper organization, and !WOON, an NGO that advices on the rights of tenants and home owners in and around Amsterdam, was invited to take up this role. !WOON agreed to collaborate and became responsible for the recruitment of young people (with the aim of setting up a Youth Board, see also Section 4.2) and the day-to-day management of the co-creation process. Since !WOON has a strong network among local professionals and policy-makers, their involvement also increases the potential to defend the right to housing for young people in Amsterdam.

4.1.2. Drafting an action plan and setting goals

In the first 6 months of the UPLIFT project, the stakeholders involved set up an elaborate action plan with specific goals, a clear scope and focus and a rather detailed time planning. In terms of content, the action plan distinguished between three separate co-creation cycles, also called sprints. Each sprint consisted of an inventory stage, a solution oriented stage and a feedback stage. In three consecutive sprints, the following three topics were planned to be covered:

1. Temporality on the housing market;

2. Community oriented housing concepts;

3. A youth housing policy agenda.

Essentially, these cycles, or sprints, can be seen as equal iterations of co-creation, each time with a different focus. Collectively, we refer to them as the co-creation process.

4.1.3. Reflection and evaluation

Setting up a solid and fruitful collaboration between stakeholders is a time intensive and potentially complicated process. Honest discussions among stakeholders about objectives, roles, resources and capacity are necessary, and trust needs to grow between the people involved. In this regard, it is important that the roles and objectives of the different stakeholders are as clear as possible since the onset of the process. Consequently, it is advisable to agree on the scope, the focus and the expected outcomes of the co-creation before the process actually starts. Written agreements and plans, such as a clear action plan that is agreed upon early on, could be helpful in getting clarity this respect.

Notwithstanding the above, it is impossible to plan the whole process upfront, and flexibility and anticipation remain important. In order to retain this flexibility, a local co-creation team with representatives from the municipality of Amsterdam, housing association Lieven de Key, !WOON and TU Delft was established. This team met on a regular basis (once every week or once every 2 weeks) in order to discuss the progress of the co-creation process, plan ahead, and adapt to unforeseen circumstances. During these meetings, minutes were taken and action points were identified.

4.2. Involving young adults in an inclusive manner: The youth board

4.2.1. Setting up a Youth Board

The UPLIFT project started in January 2020 and the first half year was dedicated to building the stakeholder network and drafting the local action plan. Only in the second part of 2020 the actual formation of the Youth Board took place. Through their networks and by making use of a social media and online advertising strategy !WOON started to recruit young people that were interested to participate in the UPLIFT co-creation activities. Some of these young people were directly contacted by !WOON, whereas other were found through gatekeeper organizations in the field of social work or youth work, or through the networks of young people that had already been recruited (snowball sampling). When recruiting the Youth Board members !WOON strived for diversification in terms of age, gender, ethnic background, and housing situation.

In each of the three thematic sprints, a Youth Board of around 8 people was structurally involved in the co-creation process, which implies that they attended the majority of the meetings that were organized. Some of these Youth Board members participated in more than one sprint, thereby guaranteeing a degree of continuity. However !WOON also recruited several young people that did not have the time or interest to become Youth Board members, and that more incidentally participated in the co-creation sessions.

!WOON was responsible for managing and moderating the co-creation sessions, thereby intending to give the young people ownership of the process. This was not easy because due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the related restrictions, the Youth Board members could not meet in person during the first thematic sprint. However, they successfully collaborated in the many online activities that were organized and gradually started to form a community.

For the second and third sprint of the co-creation process, new Youth Board members were recruited by !WOON in order to compensate for attrition and bring new energy into the process. This time, recruitment not only took place through social media and networking, but also through participation in introductory events at schools for vocational and higher education.

4.2.2. Reflection and evaluation

The goal of the Youth Board is to articulate the voice of the target group of young people. To be able to optimally fulfill this role, it is essential that principles of diversity are respected in the composition of the Youth Board (e.g., gender balance, ethnic representation). In relation to this, it is of crucial importance to be sensitive to differences within the target group of young people, for example with regard to gender and ethnic background, and to assess how such differences could influence both the process and the outcomes of the co-creation project. Youngsters with various backgrounds should have equal opportunities to participate and have their voice heard.

Moreover, the policy initiatives that will result from the co-creation process, need to take into account that youngsters with different genders and/or ethnic backgrounds may experience different problems, and may therefore also need different solutions. This was evident for example during Sprint 2, when discussions about a communal housing concept highlighted a difference in the perception of shared spaces between young women and young men. How to increase the (feeling of) safety of shared spaces became part of the discussions only after the input of the female Youth Board members.

When recruiting new Youth Board members, !WOON has purposively looked for youngsters that would contribute to the diversity within the Youth Board composition. However, despite efforts, it turned out to be difficult to reach the same rate of participation for the lower educated young people as for the higher educated young people. In hindsight, it would perhaps have been better if we would have developed a specific recruitment strategy aimed at reaching the former group. One the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that the housing crisis in Amsterdam affect youngsters from all education levels. Indeed, as far as housing is concerned, virtually all Youth Board members are in a vulnerable position, despite the fact that not all have experienced, or still experience, vulnerabilities in other domains. Thus, overall, we contend that the Youth Board offers a good representation of the young adults that experience housing problems in the Amsterdam housing market.

4.3. Running and moderating the actual co-creation process

As has already been indicated in Section 4.1, the actual co-creation process consisted of three so-called sprints, that each dealt with a different topic. In this Section, these sprints are described and reflected upon in terms of both methodology and content.

4.3.1. Sprint 1: Temporality in housing

This thematic sprint started in October 2020, when the recruitment phase of the Youth Board had been completed. The starting point for this sprint was the observation that temporality on the housing market had become more important in recent years. Indeed, since the change of the rental laws in 2016, temporary rental contracts (usually for 2 years in the private rental sector or 5 years in the social rental sector) have become the norm for many young people in Amsterdam. The pros and cons of this development, for both tenants and prospective house seekers, have been extensively discussed throughout this sprint. Furthermore, ample attention has been given to the house seeking process in general, and the information and resources that are needed to successfully navigate on the Amsterdam housing market, in particular.

The process started with an inventory stage (see also Figure 1). In this stage, the Youth Board members have participated in various capacity building activities, such as webinars and mini internships, that were specifically organized for them by professionals from Lieven de Key, TU Delft, !WOON, and the municipality of Amsterdam. The goal of these activities was to familiarize the Youth Board members with the housing situation in Amsterdam, the housing actors and housing policies at the local level, and the topic of temporary housing.

In the inventory phase, the Youth Board members also reached out to other young people in their network in precarious housing situations, so that they would get a good insight into the various real life experiences with regard to temporality. At the end of the inventory stage, it was concluded that temporality and temporary housing contracts negatively affect the sense of security (see also Huisman, 2020). Young people feel they cannot really settle down, and are constantly worried about what happens when their rental contract ends. Furthermore, it was observed that the available information regarding housing opportunities and housing rights for young people is scattered and incomplete.

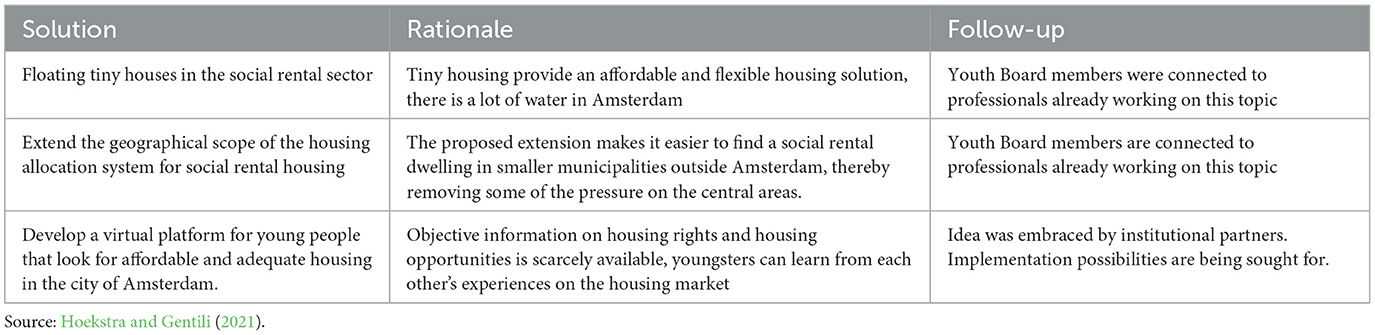

The inventory stage was followed by a solution oriented phase in which the Youth Board has developed policy solutions that aim to improve the position of vulnerable young people on the Amsterdam housing market. Because this sprint took place during the run-up to the national elections, the Youth Board also wanted to influence the national debate regarding youth housing. That is the reason why the Youth Board members have recorded a number of videos in which they showed what they would do if they would become the new minister of housing. While the policy suggestions for the national level remained rather general, the solutions that were developed for the local level contained more detail. These solutions, that were prepared in smaller groups, started from the conviction that a structural reform of the housing system (such as the abolishment of temporary rental contracts) is not feasible in the short run. However, also within the framework of the current system, small changes may make a considerable difference. Taking this into account, three local policy solutions were proposed (see Table 1).

In May 2021, the Youth Board presented its policy solutions to representatives from housing association Lieven de Key, the municipality of Amsterdam, !WOON and TU Delft in two separate meetings (one with professionals and one with executives). There was a large appreciation for the creativity of the Youth Board and the soundness of their ideas. However, it appeared that two of the three proposed policy solutions were already considered in another context. The third proposed solution – a virtual platform for young house seekers – was further developed by a subgroup of the Youth Board, after which a search for implementation possibilities started (see Section 4.4 for the current state of affairs).

4.3.2. Sprint 2: Developing a new communal housing concept

This co-creation sprint commenced in September 2021 with a kick-off meeting at which both the Youth Board and the local UPLIFT partners were present. At this evening event, there was a general discussion on vulnerability, after which the proposed focus of the second co-creation was explained in more detail by representatives from housing association Lieven de Key. The idea for this sprint is that the young people develop a new inclusive communal youth housing concept that has the potential to be implemented by said housing association. The potential location for this housing concept is an inner city location next to an existing housing complex of Lieven de Key, where currently a bike shed is located. Since this sprint not only has elements of co-creation but also of co-design, the architectural firm INBO was asked to moderate the co-creation sessions in collaboration with !WOON.

Two inventory sessions followed after the kick-off meeting. In the first of these two sessions, the Youth Board members visited two already existing communal housing concepts of housing association Lieven de Key. They looked at the design and the functionalities and talked with the community manager about the process of community building. In the second inventory session, the Youth Board members reflected on the pros and cons of existing communal housing complexes. Based on this reflection, they formulated a set of requirements for what they would see as a successful and inclusive communal housing concept.

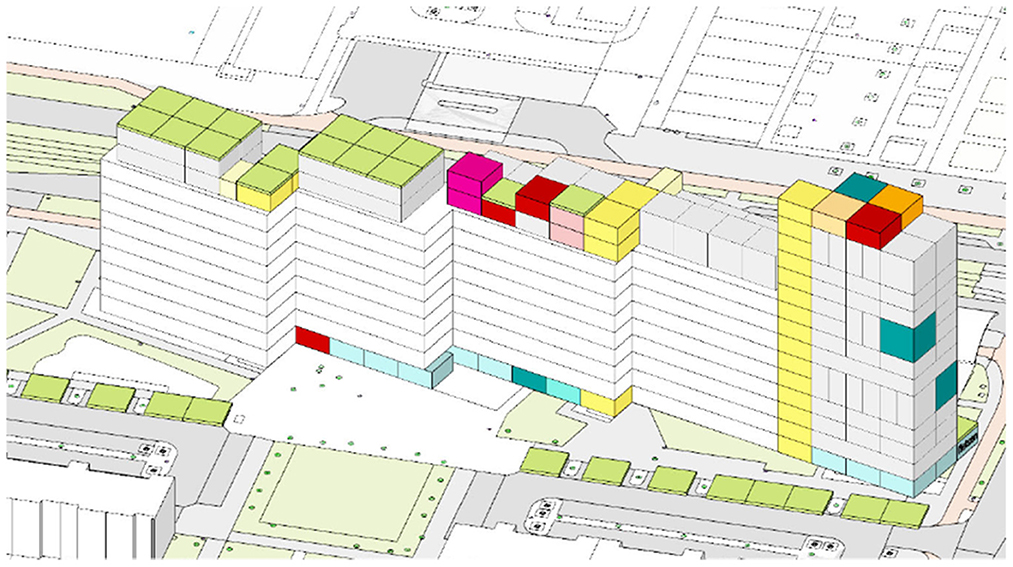

In the two solution oriented sessions that followed, this set of requirements was further developed and specified, based on an exploration of the location and an assessment of some relevant reference projects. Specific attention was paid to the desired community processes and the “house rules” within the prospective complex, as well as to the possibilities for including vulnerable groups. This process led to a more specified set of requirements (a so-called functional brief) that was translated into three different scale models, composed of blocks that represent different functions within the building (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. An example of one of the scale models. Source: INBO and the Amsterdam Youth Board (2022).

All scale models involved a transformation of the existing housing complex (adding extra layers with dwellings and communal facilities), whereas two of three scale models also planned to construct new dwellings and communal facilities in the place of the bike shed. Moreover, they all plan several communal facilities in the new building: roof garden, laundry rooms, co-working spaces, a restaurant, sport facilities, rooms for occasional visitors and multi-functional spaces. The idea is that these facilities are not only accessible to the young people that are going to live in the housing complex, but also for the residents in the neighborhood. Dwellings that are suitable for housing disabled people are planned in the plinth of the housing complex, whereas greenery and facilities for urban farming should appear in its direct neighborhood.

In a final feedback session, the proposed communal housing concept was presented to, and discussed with, professionals from Lieven de Key and the Municipality. The professionals appreciated the inclusiveness, the comprehensiveness and the creativity of the proposal. However, they also raised some critical questions with regard to the costs involved and the degree of innovation. Initially, the Youth Board was taken by surprise by this somewhat unexpected criticism. However, already during as well as immediately after the feedback session, ideas were developed to make the housing concept more financially feasible, for example by self-management and/or renting out communal spaces to non-residents. The final result of this sprint was a booklet by INBO and the Youth Board that was presented to housing association Lieven de Key (INBO and the Amsterdam Youth Board, 2022).

4.3.3. Sprint 3: Developing a new housing policy agenda for the municipality of Amsterdam

The third co-creation sprint has run from February 2022 to December 2022. The aim of this sprint was to give input to the youth housing policies of the municipality of Amsterdam. The sprint started with a kick-off meeting in which the scope of the co-creation process (local housing policies that are relevant for young people) was defined. After that, barriers on the housing market from the perspective of the “life world” of young people have been made visible, and priorities toward solving these barriers have been set (two inventory sessions were dedicated to this). Subsequently, possible policy solutions for removing these barriers were explored and developed in two solution oriented sessions, followed by a reality check in which the proposed solutions have been presented to, and discussed with, relevant stakeholders.

During the whole co-creation process, policy-makers from the municipality were available through a so-called hotline, so that they could answer questions and provide information regarding the local housing market and local housing policies. After the reality check, the Youth Board prepared a manifesto for the municipality of Amsterdam (Youth Board Amsterdam UPLIFT, 2022). This manifesto contains a number of recommendations for the local government, as well as an underpinning of these recommendations:

• Provide support to youngsters with a temporary rental contract that (almost) ends and that have nowhere to go on the housing market;

• Facilitate house sharing among young people;

• Support young people that want to start a housing cooperative or a co-housing initiative;

• Build more large scale youth housing complexes at the edges of the city. Make sure that these complexes have sufficient facilities (supermarkets, cafes) and a good 24 h public transport connection to the city center;

• Counter empty buildings with a good registration system and a clear regulation. Start a project that invites people to develop creative and innovative solutions for empty buildings;

• Inform young people about the complicated Amsterdam housing market by sending them an information package once they turn 16 or 18;

• Lobby toward the national government for the reform of national policies that hamper the housing opportunities of young people (seven specific recommendations were done with regard to this topic)

• Continue the youth panel so that young people get a permanent voice in the housing policy development process in the city of Amsterdam.

On December 12, 2022, the manifesto was presented to, and discussed with the alderman of housing of the city of Amsterdam (see Figure 3). The alderman indicated that he will attempt to include the suggestions of the Youth Board into the new housing vision that the city is currently developing. This vision will be established in a bottom-up way, with a lot of participation of local residents and housing professionals3.

4.3.4. Reflection and evaluation

Looking back on the three co-creation sprints with the Youth Board, a number of observations can be made.

First of all, we observe that there is a clear connection between the scope of the co-creation process (what are the topics that are dealt with?), the expected outcomes (fully developed new concepts or more general recommendations?), and the need for capacity building/community forming on the one hand, and the time that is required to successfully complete the process on the other. In our first sprint, the scope of the co-creation process was fairly broad (temporary housing) and we had 9 preparatory and inventory meetings (out of 17 meetings in total), also because there was a real need to invest in capacity building and community forming within the Youth Board. The second sprint on the other hand followed a much more compact process, and contained only 6 sessions. This could be achieved because the scope of this sprint was rather narrow (the development of an inclusive communal housing concept for young people) and the expected outcomes (set of requirements and scale models) were clearly defined upfront. Moreover, because the Youth Board was already established (even though some new members joined), less time needed to be dedicated to community forming. The third sprint had a similar number of meetings as the second sprint, even though the topic to be addressed was much broader. However, compared to the first and second sprint, the expected outcomes of this sprint were more general (policy recommendations rather than fully developed concepts).

Although the time-intensity of the co-creation process may differ, capacity building in the inventory phase seems to be of crucial importance for achieving fruitful outcomes. In order to be able to formulate policy solutions that can bridge the gap between the “life world” of young people, and the “system world” of professionals, policy-makers and institutions, it is important that the young people get some insight into the functioning of this system world (i.e., the policy and institutional context of the problem at hand). Webinars, excursions and mini internships can play an important role in this respect. At the other side of the gap, and in a similar vein, policy-makers and professionals need to change their mind-set and become more receptive to the opinions and ideas of the young people.

A third important point for reflection is how to raise young people's creativity and keep them engaged. In our view, the key for achieving high levels of engagement is to incorporate group work and make discussions interactive. Within the group work, it is important that every participant gets the possibility to express their opinion and actively contribute. This can for example be done by pairing people up in small groups or tandems and using live polling platforms as a starting point for discussion. Furthermore, a good moderation of the group sessions is crucial. It is important to observe the group dynamics during the meetings and make sure that very vocal or dominant participants do not take over the conversation. Particularly, sessions in which young people are mixed with institutional stakeholders may be threatening for the former and require a good preparation and management of expectations for both groups.

Fourth, it should be realized that even though the Youth Board has a balanced composition (in terms of gender and ethnic background, see also Section 4.2), this does not automatically guarantee equal processes and solutions. Therefore, in the interactions during the meetings, the moderators have tried to be sensitive to potential differences between people of different genders and ethnic backgrounds in terms of attitude, tone of voice, and participation in discussions. They have strived for a setting and atmosphere in which everyone feels safe and free to express its opinion.

Fifth, it is crucial to make the meetings and the general circumstances of the co-creation process attractive for the target group. Therefore, we provided food (“pizza sessions”) and refreshments and occasions for social engagement during the Youth Board meetings. Furthermore, the municipality of Amsterdam decided to pay a so-called volunteer fee to the most active Youth Board members, as a compensation for the large amount of time that they have invested. Last but not least, three active Youth Board members were invited to participate (with all costs covered) in the UPLIFT consortium meeting in Barakaldo that took place in the autumn of 2022.

4.4. Impact on young people, institutional stakeholders, and policy implementation

The co-creation process had different objectives depending on the type of participants. For young people, the process was meant to provide the opportunity to gain knowledge of the housing context and policy process; to be taken seriously and be able to safely express their opinions; to influence local decisions about housing and to feel empowered – that is, to feel like they can make an active contribution to the institutional life of their city. For institutional partners, the aim was to increase their knowledge and understanding of youth housing problems and to create a channel of communication with a group that has specific needs and is not well represented in the current policy-making processes. Overall, we wanted UPLIFT to provide the opportunity for institutional actors to think together with young people, in order to develop policy solutions more attuned to their needs and to show that co-creation can be a sustainable and useful method for policy development.

In order to know if and to what extent these objectives had been achieved, we developed a survey that was distributed to all the people who participated in the co-creation process, in a slightly different version for the Youth Board and the institutional stakeholders. We asked questions with regard to four aspects: the overall success of the co-creation, the quality of the process, the value of co-creation, and the future of the Youth Board. The aim of the survey – together with the observations made during the process and the outcomes of the co-creation – was to assess the impact of the co-creation process as a whole on the Youth Board members, the institutional stakeholders, and the policy implementation possibilities. Overall, 16 people responded to the questionnaire, 7 from the Youth Board and 9 from the institutional partners (the Municipality, Lieven de Key, !Woon and INBO).

4.4.1. Impact on the young people

Overall, the Youth Board members rated the co-creation rather positively – with a score of 3.71 on a scale from 1 to 5 – and most of them reported enjoying taking part in the co-creation activities – with a score of 4.29 on a scale from 1 to 5.

With regard to the quality of the process, young people were particularly happy with the moderation work done by !Woon in all the sprints, as it provided a safe space for them to freely express their opinions. The number of sessions for each sprint was considered sufficient, and for the most part Youth Board members thought there was enough time for discussion in each meeting. Moreover, they felt that the time and effort the co-creation required of them was appropriate.

In relation to the added value of the co-creation process – whether it led to useful and constructive results in terms of content – the Youth Board overwhelmingly agreed that the topics that were being discussed were relevant to the young people of Amsterdam. When asked if they thought the proposed policy solutions were realistic, Youth Board members were very positive, while there was more disagreement about their level of innovation. This is in line with our observations with regard to Sprint 2, where the proposed housing concept was not as innovative as the institutional partners were expecting, but focused very much on the practical needs of communal living.

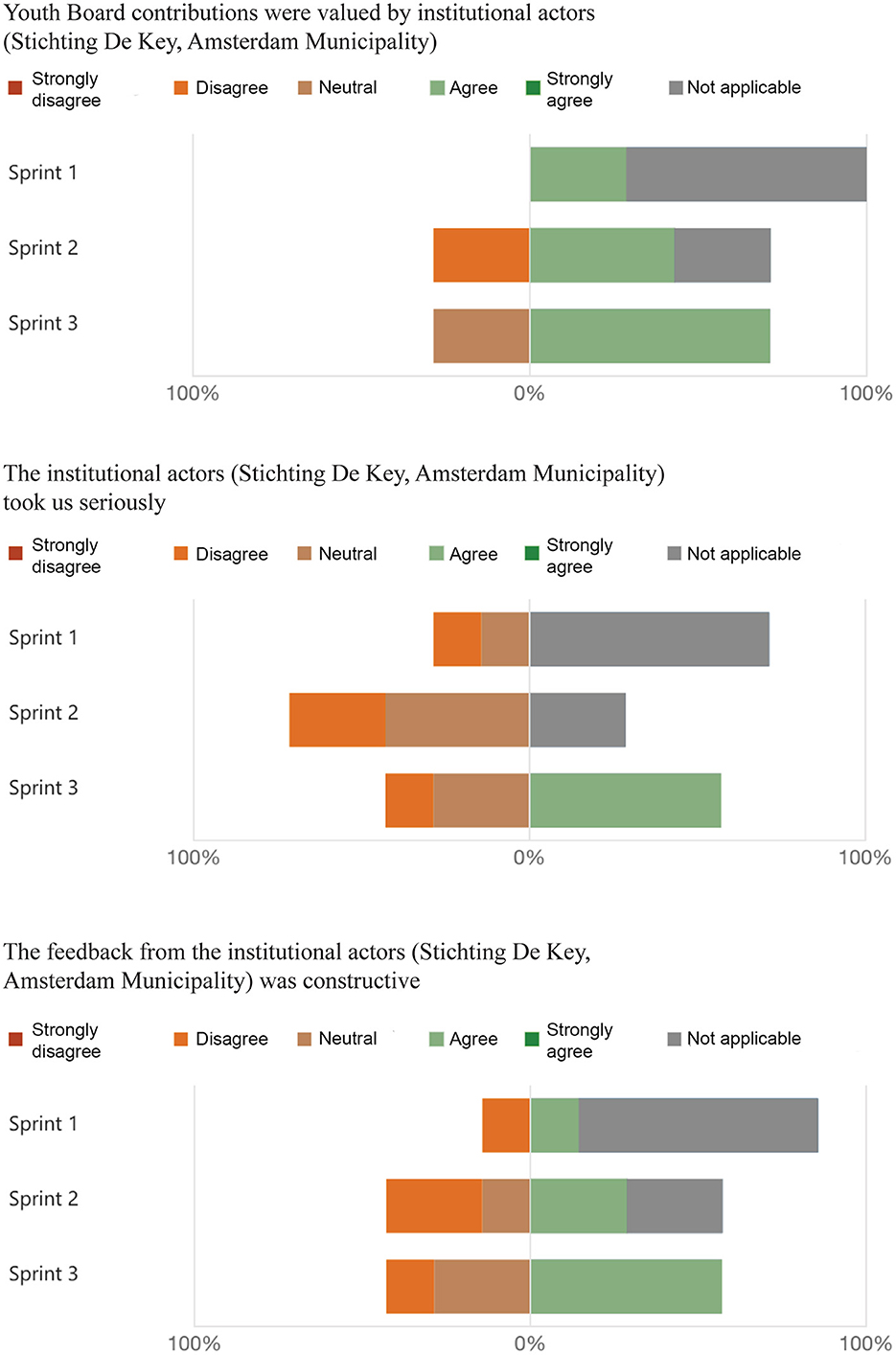

The most interesting results came from the questions related to the communication and relationship with the institutional stakeholders (see Figure 4). There were some mixed feelings among the Youth Board members about how their ideas and proposals were received by the Municipality and Lieven de Key, and there was definitely some dissatisfaction because young people did not perceive that they were being taken seriously enough. Similarly, there were mixed feelings about whether the feedback that Lieven de Key and the Municipality provided to the Youth Board's ideas and proposals was constructive or not.

When asked about whether they thought that their proposals will be in some way integrated in the policies of Lieven de Key and the Municipality, the response of the Youth Board members was not very hopeful, but not negative either: judging by the majority of neutral answers, they are suspending their judgement for the time being. Indeed, it seems that they do not fully trust that implementation will take place, but after seeing the commitment of the institutional actors during the whole process, they are not completely sure that it will not happen either.

As testament to the value they placed in the co-creation process as a whole, young people overwhelmingly agreed that a Youth Board should be a permanent feature of the housing policymaking process in Amsterdam, and also that every Dutch municipality should have its own Youth Board.

With regard to participation and empowerment, most of the Youth Board members felt that the co-creation process they participated in should have continued for a longer period of time and confirmed that they would take part in a co-creation process again. But the most positive result is that all the Youth Board members reported feeling empowered by participating, and that UPLIFT contributed to their growth as both citizens and individuals.

In order to better understand what the Youth Board members considered the most valuable results of the co-creation experience, we specifically asked them what they gained from participating. The highest score was for network possibilities, together with feeling useful and heard, the second place was for knowledge of both the housing market and the policymaking process, followed by personal growth. Contact with other young people was ranked the lowest.

Overall, in terms of the objectives that we set in the beginning for young people participating in the co-creation process, we can be quite satisfied with the results of the survey with regard to the empowerment of the Youth Board members, the quality of the process and the value that young people attach to the co-creation process as a whole. What needs more work is the relationship between the Youth Board and the institutional stakeholders.

4.4.2. Impact on the institutional partners

For the institutional actors – Lieven de Key, the Municipality, !Woon and INBO (although we differentiated the questions between the policymakers and the moderators) – the overall appreciation for the co-creation process is 3.9 on a 5 point scale. Moreover, they rated their interaction with each other, and with TU Delft, also at 3.9 on a scale from 1 to 5. Similarly to the young people, also the policymakers were happy with !Woon's organization and moderation.

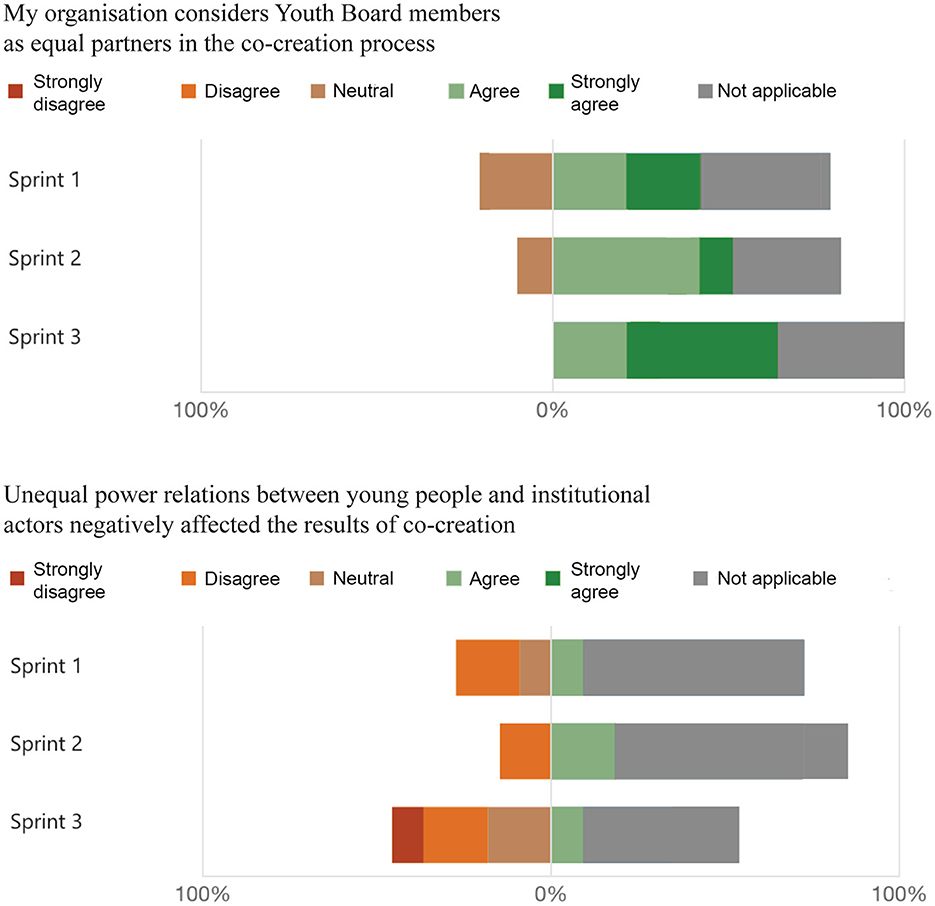

In order to assess the quality of the co-creation process we provided some statements and asked institutional actors to what extent they agreed with them. All institutional participants overwhelmingly recognized that Youth Board members were involved and proactive, and also that they were aware of the limitations – both in terms of rules that come from different administrative levels and in terms of financing – that constrain policy action and the co-creation process in particular.

Youth Board members were mostly considered as equal partners by the policymaker actors – which contrasts a little with what young people reported about being taken seriously and their contributions being valued. Similarly, policymakers did not think that the inevitably unequal power relations affected the process in a negative way, while moderators were more sensitive to the impact of the imbalance of power (see Figure 5).

With regard to the added value of the co-creation process for their organization, all institutional actors recognized that for most of the sprints – particularly the first and the third, which are more generic and less “project-based” – the co-creation generated new insights on existing issues for their organization. Similarly, the knowledge that was generated in all three sprints was considered useful by all the institutional actors. This was evident also by discussions with stakeholders (both policymakers and moderators): they gained insight on specific aspects and specific problems of which they were not aware and they were able to expand their understanding. An example of this would be the Municipality learning about the weight of service charges of large private rental buildings on the housing costs of young people. This is something which was not on the radar of the Municipality, but that is now being looked into.

Also in line with what young people reported, the proposed actions/solutions were not always considered very innovative, although they were considered reasonably realistic – this could signal that innovation is not a value per se and that young people can provide valuable policy input even without necessarily thinking “out of the box”.

With regard to the possibility to integrate the Youth Board's ideas into future policy initiatives, the response was mixed, as there is much insecurity about what could happen in the future despite the good intentions. Moreover, the policymaker partners highlighted a need for more attention to the financial feasibility aspect for all the proposed ideas.

In terms of institutional participation, it can be said that Lieven de Key, !Woon and the Municipality would also like to continue the process, just like the Youth Board, and this is a very positive outcome, together with the fact that they would also do it again, and, even more importantly, that there is overall support within the participating organizations to use co-creation as a way of working for the future. The creation of a permanent Youth Board as a body to work together with institutions on youth policy issues is also supported. However, it is necessary to think about the time and money commitment required to take part in such co-creation efforts.

Judging by these results, the specific objectives of increasing institutional understanding of youth housing problems and creating a channel of communication with underrepresented young people have been achieved. However, the quality of the communication and relationship could be improved, also in view of increasing efforts toward the implementation of the suggested measures.

4.4.3. Impact on policy implementation

Section 4.3 has shown that all three sprints in the Amsterdam co-creation process have resulted in some clear new concepts and policy suggestions. From Sprint 1, the proposal to establish a virtual housing platform for young people was the idea that showed most potential. As a follow-up to this sprint, representatives of the Youth Board and !WOON have been in contact with representatives from the municipality to see if they could integrate the platform idea into plans that are currently being developed for the Amsterdam South East area. Unfortunately, these talks have been unsuccessful, as there seems to be too much divergence between the vision of the Youth Board and the vision of the municipality. Nevertheless, the awareness of the importance of clear and objective information provision for young people has clearly been raised among local housing makers. Therefore, together with the Youth Board, the local co-creation team will continue to look for possibilities to put the platform idea into practice. For this purpose, the umbrella organization of Amsterdam housing associations will be approached in the beginning of 2023.

Sprint 2 resulted in a proposal for an inclusive communal youth housing concept for housing association Lieven de Key. The executives of Lieven de Key are positive about this concept and intend to implement it into their housing redevelopment plans for the Amsterdam West area. Furthermore, specific elements of the proposal will be incorporated in other communal youth housing complexes that Lieven de Key is currently developing.

The policy impact of Sprint 3 will only become visible in 2023, when the new housing vision of the municipality of Amsterdam will be presented.

4.4.4. Toward a permanent Youth Board?

The survey results show that there is a strong support for continuation of the Amsterdam Youth Board after the UPLIFT funding has ended. Taking this into account, !WOON has recently decided that they will continue with the Youth Board. Ideas for a fourth co-creation sprint, which should focus on collaborative housing, are currently being developed by the moderators from !WOON. It is not yet clear what role the municipality, housing association Lieven de Key and TU Delft will have with regard to the planned continuation of the Youth Board.

5. Discussion and recommendations

5.1. Discussion

The main takeaway from this co-creation experience is that the importance of this form of participation seems to be very clear to young people – not talking ABOUT young people but WITH young people about the issues that concern them. Similarly, the institutional actors also appreciated the value of the knowledge produced during the process, and the increased understanding of youth housing issues. In our view, the overall impact of the UPLIFT experiment was clearly successful in terms of changing the attitudes of both groups. However, the results also show clear pathways to improve the quality of co-creation processes in terms of communication between young people and policymakers, and in terms of building relations of trust based on a clear management of expectations.

At the preparatory stage, it is crucial to discuss with policymakers about expectations management and communication with young people. Not only it needs to be clear what young people should expect from the institutional partners, but also – and perhaps more importantly for the long term sustainability of co-creation processes – the other way round. The reasons behind participation in such processes for young people are about feeling heard and trying to come to a solution for their housing problems, not to satisfy a need for innovative ideas on the part of local institutions. Clarifying this from the beginning helps to build a relationship based on trust and not on extraction, which is the foundation for a successful and equal collaboration. With regard to this, we also noticed a difference in perception between the two groups, where the limits of action were clearer to the institutional actors, so they overall evaluated the interaction as more equal and useful than the young people did.

With regard to communication, there was again a difference in perception, where the policymakers thought they were treating young people as equals, while Youth Board members did not always think that they were being taken seriously. This also boils down to honest disclosure of expectations on both parts and to appropriate and effective communication styles, especially with regard to giving feedback to people in a weaker power position. Training for the professionals involved may be a good solution for this, but the main role needs to be played by moderators during the interactions – by explaining reasons and motivations of both sides, by using clear language and by stimulating discussion on important issues.

Finally, institutional stakeholders highlighted a serious issue, which is that it would be tremendously important to reach more marginalized young people – those that are by definition less likely to take part in such an initiative – in order to widen the input and be able to take into consideration also their interests, which are often even less visible than those of educated young people.

Overall, the impact that the Youth Board had on the empowerment of young people and the attitude and mind-set of the institutional stakeholders is quite satisfactory, whereas the impact in terms of policy implementation is less impressive so far. In our perception, timing plays an important role here. While the Youth Board managed to develop new housing concepts and/or recommendations in less than half year, decision-making about the implementation of these proposals, let alone the implementation itself, may take years. For example, Lieven de Key is currently preparing the decision-making for the new housing developments in Amsterdam West, of which the new communal housing concept that was developed by the Youth Board could potentially be part. However, it will take at least a few more years before the actual realization of these developments will take place.

Furthermore, it is unlikely that all the input of the Youth Board will be adopted by the institutional stakeholders without further modification. When deciding about the implementation of this input, the interests of the young people will probably be traded off against other interests, such as the housing opportunities of other target groups and financial interests. Indeed, when he received the manifesto of the Amsterdam Youth Board, the alderman for housing already indicated that measures to improve the housing situation for young people in Amsterdam should not come at the expense of the housing opportunities for other target groups. Youth Board members seemed to be aware of this ambivalence with regard to their input, as there is a sort of suspended judgement on their part about how useful this process was in terms of future policy implementation.

In our view, the above nuances definitely do not imply that the Amsterdam Youth Board has no added value in the process of housing policy development. On the contrary; while many vested interests (homeowners, social rental tenants, students) have already organized themselves in interest groups that participate in housing policy decision making, young people (particularly the ones that are not studying and/or don't have a higher education) are so far underrepresented in this decision-making process. By expressing the needs, aspirations and interests of the former group, the Youth Board has the potential to fill this gap. We are very pleased that this potential is also recognized by the local stakeholders and that the Youth Board will continue in the future.

5.2. Recommendations

This paper has provided a comprehensive description of, and reflection on, the co-creation process with young people that was carried out in Amsterdam within the framework of the UPLIFT project. This process took place within the context of a genuine housing crisis (see Section 2.1) and was based on elements of the Capability Approach, Participatory Action Research, Policy Co-creation and Reflexivity (see Section 2.2).

Within the policy co-creation process, four main steps have been distinguished (see also Section 3). For each of these steps, we have first described what has actually happened in the Amsterdam co-creation process, after which we have critically reflected on this (Section 4). Based on these critical reflections, we are able to outline some critical conditions/recommendations for a successful co-creation process (see Figure 6). Even though these conditions are based on one particular case, with a very specific context, we hypothesize that most of them will have a more general applicability.

In order to further test this hypothesis, and assess the context-specificity of co-creation processes with young people, the UPLIFT methodology of reflexive policy making with young people takes place in four different European cities (Amsterdam, Tallinn, Sfântu Gheorghe and Barakaldo), as has already been mentioned in the introduction. In the first half of 2023, evaluation reports from all this four cities will become available, which will allow us to further specify and extend our list with critical conditions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of TU Delft. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JH and MG are jointly responsible for the conception and design of the study and jointly performed the analysis of its results. JH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with important contributions from MG. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870898 (UPLIFT). The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to Hanna Smit and Jon Buijs from !Woon for the tremendous work they did with recruitment, moderation and organization of the whole co-creation process; Myrthe Baaij, Sabien Asselbergs and Barend Wind from Lieven de Key, Maarten Lauwers, Valerie Witte, Pieter Vermeulen, Niels ten Cate and all the other people from the Municipality of Amsterdam for their commitment and work in the organization of the process; and finally to the Youth Board members for their time, commitment and knowledge. This research would not have been possible without their fundamental contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared research group [UPLIFT] with JH and MG at the time of review.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2023.1130163/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

2. ^Prices refer to 2022.

References

Arundel, R. (2017). Equity inequity: housing wealth inequality, inter and intra-generational divergences, and the rise of private landlordism. Housing Theor. Soc. 34, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2017.1284154

Arundel, R., and Doling, J. (2017). The end of mass homeownership? Changes in labour markets and housing tenure opportunities across Europe. J. Housing Built Environ. 32, 649–672. doi: 10.1007/s10901-017-9551-8

Boelhouwer, P. (2020). The housing market in The Netherlands as a driver for social inequalities: proposals for reform. Int. J. Housing Policy 20, 447–456. doi: 10.1080/19491247.2019.1663056

Gentili, M., and Hoekstra, J. (2022). Urban Report Amsterdam, The Netherlands. UPLIFT. Available online at: https://uplift-youth.eu/research-policy/official-deliverables. (accessed February 16, 2023).

Gentili, M., and Hoekstra, J. (2023). Case Study Report. Amsterdam Functional Urban Area. UPLIFT. Available online at: https://uplift-youth.eu/research-policy/official-deliverables (accessed February 16, 2023).

Haffner, M. E., and Hulse, K. (2021). A fresh look at contemporary perspectives on urban housing affordability. Int. J. Urban Sci. 25, 59–79. doi: 10.1080/12265934.2019.1687320

Hochstenbach, C. (2019). “Kansen en ongelijkheid op de Amsterdamse woningmarkt [Chances and Inequality on the Amsterdam housing market]” in Gelijke kansen in de stad [Equal opportunities in the city], eds H. Van de Werfhorst and E. Van Hest (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press).

Hochstenbach, C., and Boterman, W. R. (2015). Navigating the field of housing: Housing pathways of young people in Amsterdam. J. Housing Built Environ. 30, 257–274. doi: 10.1007/s10901-014-9405-6

Hoekstra, J. (2017). Reregulation and residualization in dutch social housing: a critical evaluation of new policies. Critic. Hous. Anal. 4, 31–39. doi: 10.13060/23362839.2017.4.1.322

Hoekstra, J., and Gentili, M. (2020). Action Plans on the Co-Creation Process: A Theoretical and Methodological Framework. UPLIFT. Available online at: https://uplift-youth.eu/research-policy/official-deliverables (accessed February 16, 2023).

Hoekstra, J., and Gentili, M. (2021). Updated Action Plans for the Co-Creation Process: Looking Back and Looking Forward. UPLIFT. Available online at: https://uplift-youth.eu/research-policy/official-deliverables (accessed February 16, 2023).

Huisman, C. (2020). Insecure Tenure. The Precarisation of Rental Housing in the Netherlands. [Thesis fully internal (DIV), University of Groningen]. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. doi: 10.33612/diss.120310041

INBO and the Amsterdam Youth Board (2022). Ons Dorp. Inclusief Woonconcept voor jongeren in Amsterdam Nieuw-West [Our village. Inclusive Housing Conceot for Young Adults in Amsterdan Nieuw-West], Amsterdam.

Jonkman, A. R. (2019). Distributive justice of housing in Amsterdam. University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research. Available online at: https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=a54e3430-a55e-47a0-9b57-efb43c219420

Kadi, J., and Musterd, S. (2015). Housing for the poor in a neo-liberalising just city: still affordable, but increasingly inaccessible. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Soc. Geog. 106, 246–262. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12101

Lennartz, C., Arundel, R., and Ronald, R. (2016). Younger adults and homeownership in europe through the global financial crisis. Population Space Place 22, 823–835. doi: 10.1002/psp.1961

Wetzstein, S. (2017). The global urban housing affordability crisis, urban. Studies 54, 3159–3177. doi: 10.1177/0042098017711649

Keywords: policy co-creation, Amsterdam (Netherlands), housing, inequality, young adults

Citation: Hoekstra J and Gentili M (2023) Housing policies by young people, not for young people. Experiences from a co-creation project in Amsterdam. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:1130163. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1130163

Received: 22 December 2022; Accepted: 08 February 2023;

Published: 27 February 2023.

Edited by:

Éva Gerőházi, Metropolitan Research Institute, HungaryReviewed by:

Lorenzo De Vidovich, University of Trieste, ItalyJucu Sebastian, West University of Timişoara, Romania

Copyright © 2023 Hoekstra and Gentili. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martina Gentili,  bS5nZW50aWxpQHR1ZGVsZnQubmw=

bS5nZW50aWxpQHR1ZGVsZnQubmw=

Joris Hoekstra

Joris Hoekstra Martina Gentili

Martina Gentili