- 1Doxy.me Research, Doxy.me Inc., Charleston, SC, United States

- 2Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, United States

- 3College of Nursing and Department of Biomedical Informatics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 4Biomedical Informatics Center, Public Health and Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, United States

There is growing need for better mental health care. It is now possible to combine convenient telehealth with engaging virtual reality towards new opportunities for personalized mental health. The goal of this study was to understand mental health clients’ perspectives on telehealth-based virtual reality therapy. We qualitatively analyzed 17, individual semi-structured interviews of mental health clients about experiences and reactions to exposure therapy over conventional telehealth, virtual reality in general, and telehealth-based virtual reality for mental healthcare. Clients were generally younger adults (M = 29.7 years), female (52.9%, 9/17), non-Hispanic White (88.2%, 15/17), and with varied income (M = $35,671; SD = $30,074; unemployed to $100,000). Clients enjoyed how telehealth made exposure therapy more accessible and comfortable, but could feel unmotivated due to lack of in-person accountability and presence. While none used VR for therapy, most tried VR with positive perceptions of it. All but one client believed telehealth-based VR exposure therapy would be useful, easy, and comfortable. However, many clients were unsure VR would feel realistic. Clients proposed tele-VR for art therapy, avatar-based therapy, and immersive games to build rapport with their therapist. Clients felt tele-VR should address specific needs, and their primary concerns were costs and insurance coverage of VR services. Overall, clients expressed excitement that VR can enhance engagement and personalization of telehealth, if costs are minimized and VR is simple to use. These results provide insights into client needs and suggest key directions to explore immersive telehealth solutions.

1 Introduction

Each year, nearly 1 in 4 American adults suffer from a mental health disorder, (NIMH, 2023) causing 5% of premature mortality and $5 trillion USD in healthcare costs (Arias et al., 2022; Vigo et al., 2022). Burdens are especially high for anxiety disorders (Piao et al., 2022) for which stigma can cause avoidance of care, worsening symptoms, and preventable deterioration of quality of life (Dubreucq et al., 2021). Telehealth-based mental healthcare (TMH) using email, text, chat, phone, and video calls has proven to be effective as in-person care with greater convenience and accessibility, (Batastini et al., 2021; Snoswell et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2022; Connolly et al., 2024) and scales favorably with healthcare costs and environmental impacts (Zhao et al., 2020; Naslund et al., 2022; Peña et al., 2024). These benefits made TMH constitute 70% of all telehealth visits (Jain, 2024). However, some clients and therapists feel conventional TMH (e.g., email, phone, or video call) can limit communication, (Lipschitz et al., 2023) interfering with therapeutic alliance and outcomes (Lopez et al., 2019). There is a need to improve TMH to meet or exceed the experience of in-person care.

Virtual reality (VR) is appealing for mental healthcare due to its unique immersion, engagement, and controllability (Hilty et al., 2020). VR has been effective for serious mental health conditions including anxiety, (Oing and Prescott, 2018) social and specific phobia, (Freitas et al., 2021) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Deng et al., 2019). To date, VR services have required clients to travel to their therapist’s office or use VR at home with the indirect or asynchronous presence of a therapist (Boeldt et al., 2019; Wray and Emery, 2022). VR-based mental healthcare may be more accessible, convenient, and effective if delivered via telehealth, (Navas-Medrano et al., 2023; Jallah et al., 2024; Amestoy Alonso et al., 2024) allowing therapists and clients to interact synchronously in a shared VR experience over the internet. To date, little but promising research has been conducted on the development and implementation of telehealth-based VR therapy (tele-VR) (Matsangidou et al., 2022; Deighan et al., 2023; Cikajlo et al., 2017; Pedram et al., 2020).

Direct involvement of end-users is critical to ensure development of effective healthcare solutions (Göttgens and Oertelt-Prigione, 2021). We previously interviewed practicing TMH therapists who were excited at the potential for tele-VR to make telehealth more interactive and personalized, and concerned over costs and clinical fit of VR for specific therapies (Ong et al., 2024a). Client preferences are especially important as their receptivity to therapy and VR are influenced heavily by personalized experiences (Pardini et al., 2022; Segawa et al., 2019; Lindner, 2021; Antoniou et al., 2024). The primary purpose of this study was to understand mental health clients’ needs, wants, and concerns about using tele-VR for exposure therapy and other forms of immersive TMH. The secondary goal of this study was to compare clients’ qualitative tele-VRET preferences with those of therapists from our previous research (Ong et al., 2024a; Ong et al., 2024b).

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

We conducted a qualitative study of U.S. mental health clients’ perspectives on using tele-VR for immersive therapy, using semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis. We specifically examined the perspectives of mental health clients who had previously received exposure therapy via telehealth, in order to compare participants lived experiences with the emerging potential for tele-VR. The Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida approved the study procedures as exempt human subjects research (IRB003548).

2.2 Participants and recruitment

Between February and April 2023, we invited participants via therapist referral, flyers, and Research Match if they (NIMH, 2023) were adults (18 years or older), (Arias et al., 2022) spoke English fluently, (Vigo et al., 2022) had previously received exposure therapy over telehealth, and (Piao et al., 2022) resided in the U.S. We compensated participants with a $75 eGift card upon completion of the interview. Participant recruitment continued until thematic saturation was achieved and additional interviews yielded no newer findings (Weller et al., 2018).

2.3 Procedures

Each participant joined the first author in a 1-h online video call using a secure version of Google Meet. The researcher used a five-part semi-structured interview guide from a previous study of therapists, (Ong et al., 2024a) modified to emphasize the client’s perspective. The guide included sections for (NIMH, 2023) informed consent and demographics; (Arias et al., 2022) TMH for exposure therapy; (Vigo et al., 2022) experiences with VR; (Piao et al., 2022) a 1 min and 35 s video depicting tele-VRET (i.e., therapist and client meeting in a video call, transitioning to tele-VR, then conducting exposure therapy over tele-VR; Figure 1); and (Dubreucq et al., 2021) impressions, concerns, and wants for tele-VRET specifically and tele-VR generally (Supplementary Material). We emphasized that compensation was for completion of the interview only and their genuine opinions were important for this research.

Figure 1. Screenshots from the tele-VR demonstration video. Therapist and client exploring digital multimedia (left) and manipulating a 3D spider in VR (right).

2.4 Data analysis

The first author led the thematic analysis using an approach from our previous study with therapists, (Ong et al., 2024a) modified for the client perspective. Clients’ perceptions of tele-VR features, overall benefits, and implementation concerns were emphasized particularly in analysis to compare with those of therapists from our previous studies. (30,35) Analysis of transcripts was conducted in MAXQDA 2022 to identify emergent themes related to exposure therapy over TMH, experiences with VR, and perspectives on tele-VRET. The researcher used meaningful phrases as the coding unit to explore repetitions, similarities and differences, cutting and sorting, and metacoding to identify and organize themes (Nowell et al., 2017; Bernard et al., 2016; Braun et al., 2012; Braun and Clarke, 2019). Emergent themes were organized by code frequency. Codes were consolidated into recurring higher-level themes and operationalized definitions across two iterations, upon which the second author reviewed the codebook. Discrepancies between the first and second authors’ interpretations of the codebook were resolved through discussion until consensus to ensure consistency and accuracy in the qualitative method (Campbell et al., 2013; Raskind et al., 2019).

3 Results

3.1 Participants

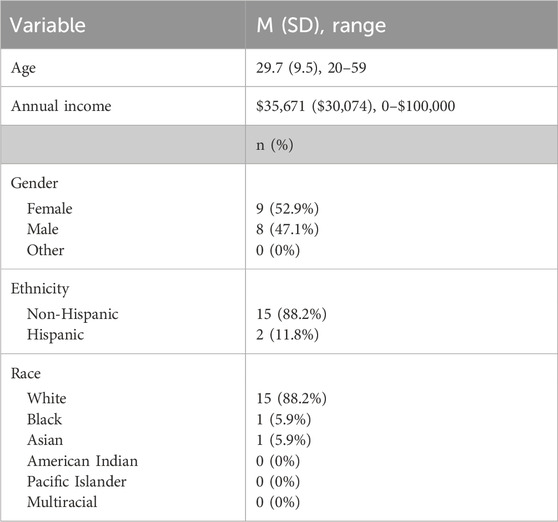

The 17 clients were generally younger adults (M = 29.7 years, SD = 9.5, range 20–59), mostly females (52.9%, 9/17), mostly non-Hispanic White (88.2%, 15/17), and with varied annual incomes (M = $35,671; SD = $30,074; range unemployed to $100,000) (Table 1).

3.2 Exposure therapy over TMH

Clients described ways telehealth facilitated exposure therapy, and some ways telehealth could make therapy feel incomplete. All clients (100%, 17/17) reported experiencing TMH in the form of video calls.

Most clients (64.7%, 11/17) stated TMH made exposure therapy easier to access, especially clients with few local specialists and clients who preferred to speak with their therapist while doing exposures in their daily life. Some clients (29.4%, 5/17) felt TMH made exposure therapy less stressful as they could engage with their feared situations from home, and their therapist seemed more efficient with telehealth.

A few clients (17.6%, 3/17) felt less engaged with exposure therapy over TMH due to a weaker sense of accountability. A few clients (17.6%, 3/17) encountered exposure-specific technical concerns such as unintuitive interfaces and perceptions of weak internet security. A few clients (11.8%, 2/17) also felt exposure therapy over TMH made it harder to build rapport with their remote therapist due to difficulty perceiving body language and nonverbal communication.

3.3 Prior experience with VR

All clients (100%, 17/17) defined VR as feeling immersed in another world through head-mounted displays. Most clients (9/17) had tried VR video games like Rec Room (https://recroom.com) and Beat Saber (https://beatsaber.com). Some clients (29.4%, 5/17) experienced VR at their friends’ houses. Some clients (29.4%, 5/17) tried VR at a university library or computer lab. Two clients (11.8%, 2/17) personally owned VR for gaming. Four clients (23.5%, 4/17) had never tried VR. No clients used VR for mental healthcare, but some (35.3%, 6/17) heard about VR for exposure therapy on TV or news articles.

Most clients (76.5%, 13/17) had positive perceptions of VR as useful, fun, and improving over time. Some clients (35.3%, 6/17) had neutral perceptions of VR as helpful under certain conditions. Some clients (35.3%, 6/17) had negative perceptions of VR, believing it was clunky, nauseating, or potentially harmful.

3.4 Perceptions of Tele-VRET

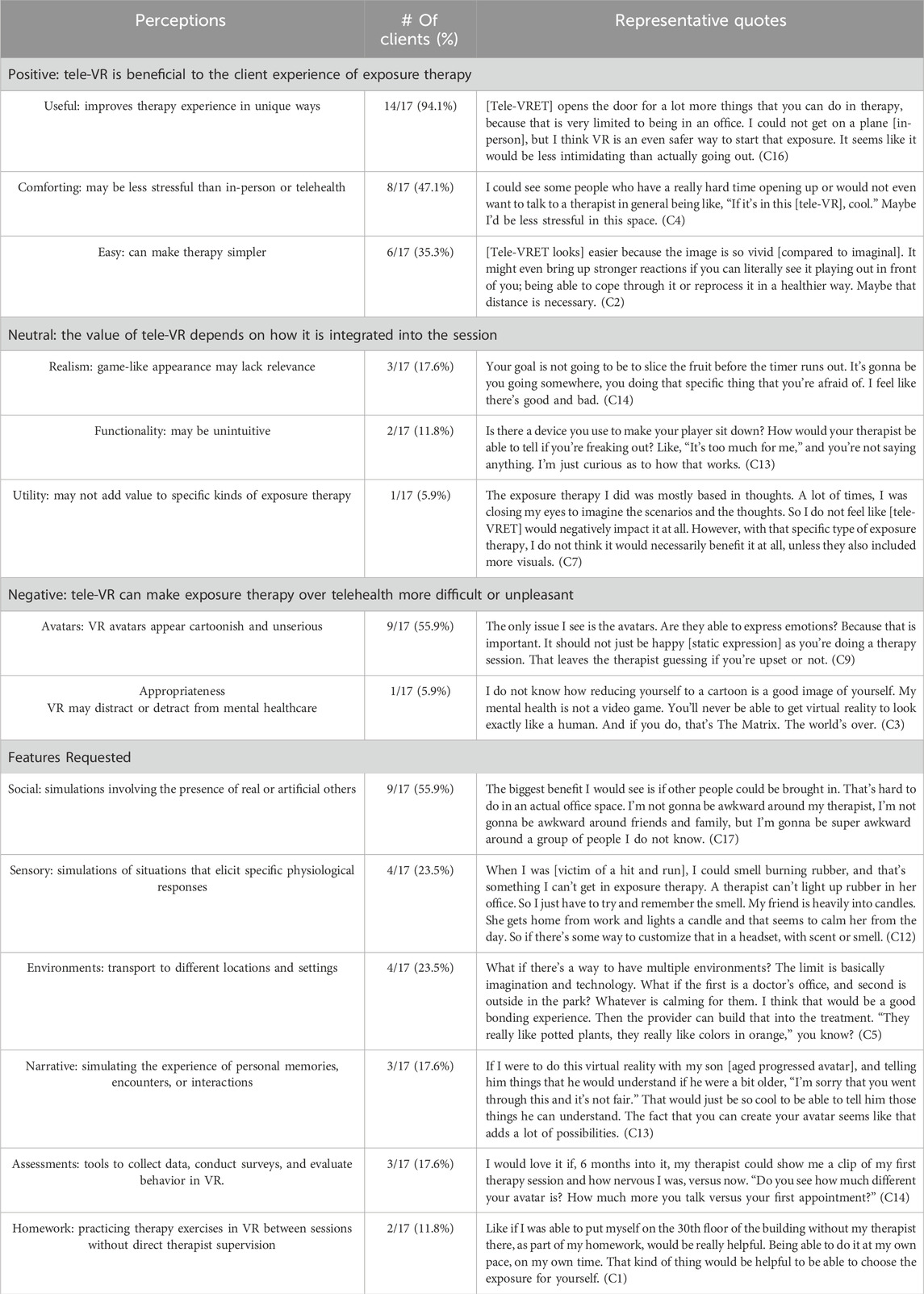

We asked clients about their reactions to the tele-VRET video, relevance to their TMH experience, and tele-VR for mental healthcare (Table 2).

All but one client (94.1%, 16/17) expressed positive perceptions of tele-VRET. Many clients (82.3%, 14/17) perceived tele-VRET as useful to share media, review clinical progress, travel to different environments, and interact with phobias safely. About half of clients (47.1%, 8/17) thought tele-VRET would be more comfortable than conventional TMH as VR could allow therapy to be more personalized and approachable. Some clients (35.3%, 6/17) believed tele-VRET would have been easier than conventional TMH or in-person, as tele-VRET may lessen pre-session stress.

Some clients (35.3%, 6/17) had neutral perceptions of tele-VRET. A few clients (17.6%, 3/17) were uncertain if tele-VRET would feel realistic. A few clients (11.8%, 2/17) were unclear about how tele-VRET functions. One client (5.9%, 1/17) was unsure if tele-VRET would add utility to imaginal exposure therapy.

More than half of clients (58.8%, 10/17) also described negative perceptions of tele-VRET, mostly due to unrealistic aesthetics or avatars. More than half (55.9%, 9/17) also stated tele-VRET avatars felt cartoonish and may not capture facial expressions and body language. One client (5.9%, 1/17) expressed that tele-VRET felt inappropriate for mental health and may be an existential threat to society.

3.5 Requested features for tele-VRET

When asked to discuss how tele-VRET could enhance care, clients described specific phobic stimuli and scenario simulations, data collection and assessment from within the VR experience, and VR experiences to complete on their own.

Many clients (55.9%, 9/17) requested social situations related to bullying, family, work, or tasks outside the home such as grocery shopping. Some clients (23.5%, 4/17) requested sensory experiences to smell flowers bloom or feel the rain on your skin. Some clients (23.5%, 4/17) requested different environments such as parks, stores, specific streets, or locations generated from photos. A few clients (17.6%, 3/17) requested highly specific narrative experiences to simulate past or future events with the ability to conclude peacefully.

A few clients (17.6%, 3/17) requested assessments within tele-VRET to complete data forms, track clinical progress, and view immersive recordings of previous sessions.

Two clients (11.8%, 2/17) requested to engage in VRET alone on their own time (e.g., homework).

3.6 Tele-VR beyond exposure therapy

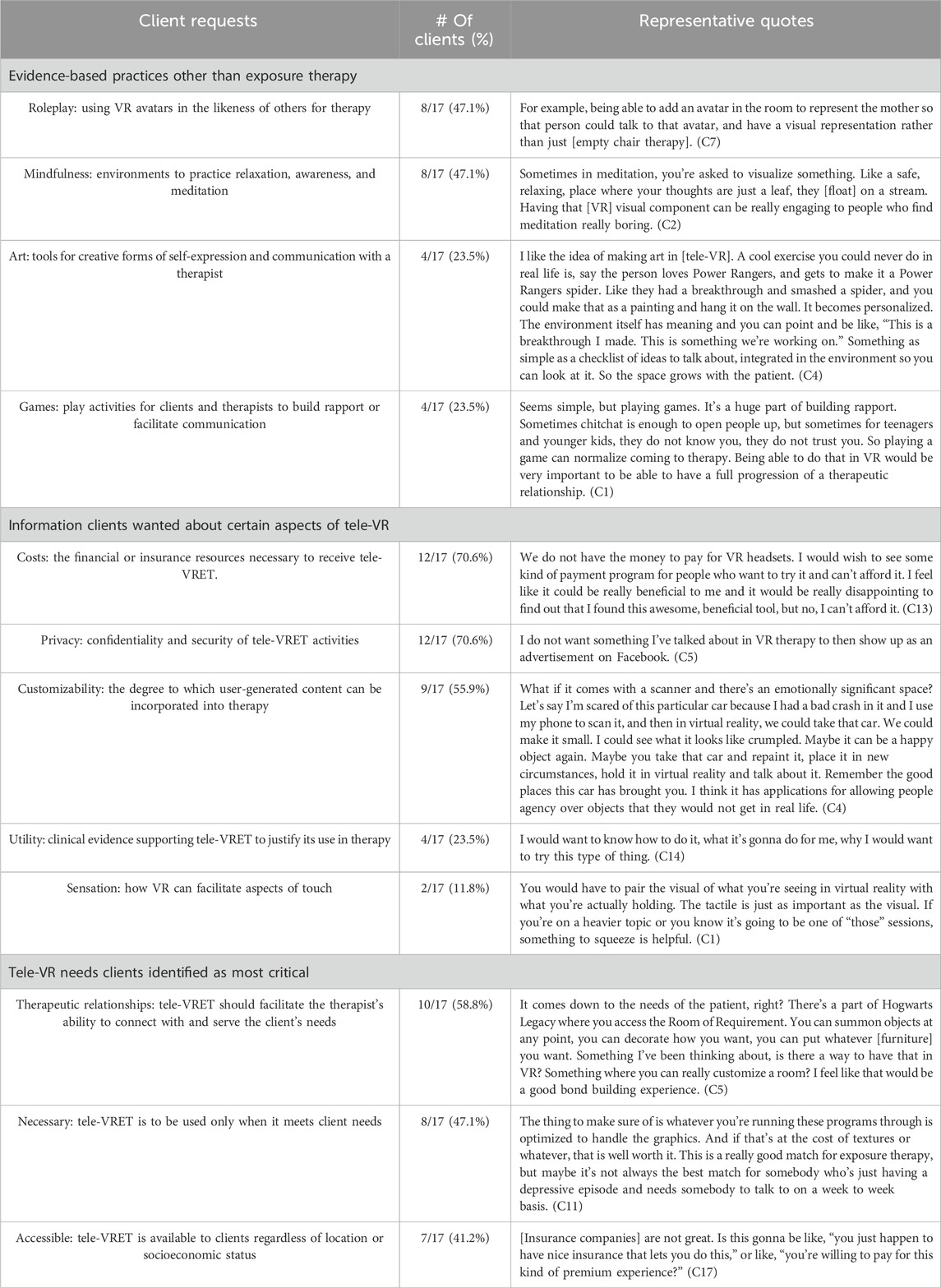

Clients requested a variety of tele-VR uses other than exposure therapy, information on how tele-VR would work, and opportunities to customize client experiences (Table 3).

3.6.1 Other tele-VR therapies

Some clients (47.1%, 8/17) requested tele-VR for avatar-based roleplay related to play, drama, and family therapy. Some clients (47.1%, 8/17) wanted tele-VR for mindfulness and biofeedback for guided meditations. Some clients (23.5%, 4/17) described tele-VR for art therapies for creating immersive visualizations with a therapist. Some clients (23.5%, 4/17) wanted to play tele-VR games to build rapport with their therapist.

3.6.2 Requested information

Most clients (70.6%, 12/17) were wary of costs associated with tele-VR such as headsets and app subscriptions. These costs seemed difficult to justify without assistance from health insurance, subsidies, or payment plans. Most clients (70.6%, 12/17) were curious about privacy while using tele-VR. Skepticism about confidentiality and uncertainty about safety may reduce confidence in the therapeutic process. Most clients (55.9%, 9/17) wanted to know about the depth of customization for tele-VR. Examples included converting photos into 3D environments or objects, VR avatars that look like other people, and VR recordings of previous sessions. Some clients (23.5%, 4/17) wanted to know about the clinical utility of tele-VR, specifically if the benefits of tele-VR were worth the effort required. A few clients (11.8%, 2/17) were curious about sensations in tele-VR for texture, weight, temperature, body contact, smell, and being in nature.

3.6.3 Critical needs for tele-VR

Most clients (58.8%, 10/17) emphasized tele-VR should facilitate therapeutic relationships by improving interaction with their therapist with minimal interference. Some clients (47.1%, 8/17) described how tele-VR should be simple and essential to support the stressful nature of mental health care. Some clients (41.2%, 7/17) said tele-VR would need to be accessible in order to consider it for therapy, especially in the context of costs of the equipment and relevant software.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

We explored client perspectives by interviewing 17 adults about their exposure therapy over TMH, VR experience, reactions to a video depicting tele-VRET, and wants from tele-VR generally. Clients said exposure therapy over TMH was accessible, but could feel less engaging. Clients had mostly positive reactions to tele-VRET, believing its immersion and interactivity could make exposure therapy easier, more comfortable, and more personalized. They proposed other helpful tele-VR practices like art therapy, empty chair therapy, and immersive games to build rapport with therapists. While exciting, clients felt tele-VR should serve specific needs and were concerned whether VR would be affordable and covered by their insurance. Overall, clients described ways VR may enhance engagement and personalization of TMH, if cost and complexity are minimized. These findings can expand the understanding of immersive telehealth in several ways.

4.2 Comparison with previous research

Client perspectives broadly agreed with prior studies of therapists’ perceptions of tele-VR (Ong et al., 2024a; Ong et al., 2024b). Therapists and clients were excited about how VR could enhance presence and interactivity in TMH, as well as customizable client experiences, tele-VRET for social and specific phobia, and for clients to engage asynchronously (i.e., homework). Clients’ and therapists’ largest concerns were costs and clinical evidence, and also believed unrealistic avatars could limit communication and immersion. Collectively, it seems therapists and clients may be likely to try tele-VR if it is affordable and relevant for a client’s specific needs. Both parties want to know tele-VR is clinically validated and will add to the healing experience with minimal, predictable risks.

In these studies, client and therapist perspectives diverged on several topics. Therapists rated customizable avatars as one of their least important tele-VR features (Ong et al., 2024b). Yet, in this study, clients strongly favored customizable avatars for themselves, therapists, and simulated assistants. This signals the need for research exploring how therapists and clients can utilize VR avatars for therapy, including avatars in the likeness of others (van Minnen et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2023). Therapists and clients agreed on factors for implementing tele-VR: affordability, insurance coverage, and accessibility. However, therapists rated enhanced presence as low priority while clients described it as a major appeal of tele-VR. Therapists may overestimate clients’ trust and comfort, which can negatively impact clinical outcomes (Bar-Kalifa et al., 2016; Moshe-Cohen et al., 2024). Hands-on user studies will be important to understand how therapists and their clients utilize tele-VR in practice.

VR may make therapy more approachable for those who avoid mental health because of stigma and poor expectations of individualized care (Dubreucq et al., 2021; SAMHSA, 2020). Here, clients reported tele-VR may provide a comforting sense of anonymity with avatars instead of their real self, while letting them feel immersed in a clinical space from home. Studies should evaluate how VR adds to conventional TMH experiences and outcomes, with emphasis on signals of success such as likelihood to seek care, therapeutic alliance, and satisfaction (Humbert et al., 2023; Benbow and Anderson, 2019). It will also be valuable to study predictors of clinical outcomes and how they may interrelate with features of tele-VR: therapeutic alliance, (Baier et al., 2020) presence and immersion in VR, (Slater et al., 2022) and therapeutic presence (Aafjes-Van Doorn et al., 2024). These results also provide qualitative ways therapists might use VR to personalize TMH: avatars that look like others relevant to a client’s treatment, (van Minnen et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2024; van Gelder et al., 2022) spontaneous but anonymous interactions in public spaces, (Dilgul et al., 2021; Fajnerova et al., 2024) using VR to visit real-world places, (Kostakos et al., 2019) and narrative VR in which a client could simulate outcomes different than those of prior experiences (Georgieva and Georgiev, 2019; Mao et al., 2023). These options should be explored to understand the economic and clinical feasibility of personalized tele-VR and its effect on client outcomes.

Clients were skeptical about tele-VR reliability, security, and privacy. One client expressed bleak expectations for tele-VR to disrupt face-to-face relations. Addressing these concerns will require transparency across academia, clinical care, and industry. While research suggests side effects of VR are minor, temporary, and preventable, (Simón-Vicente et al., 2024) these risks must be addressed nonetheless. Some clients reported dissociation after using VR, (Mondellini et al., 2021; Taveira et al., 2022) therapists have expressed concern about potential VR addiction, (Ong et al., 2024a; Kaimara et al., 2022) and leading VR companies have questionable reputations for user privacy (Cross, 2024; Tukur et al., 2023). Delphi studies and consensus statements by representative organizations may facilitate commitment to healthcare operations and privacy standards (Abbas et al., 2024).

4.3 Limitations and future directions

These results should be interpreted with several limitations. First, these findings were the result of qualitative analysis, which may be subject to bias. However, themes and definitions identified in the current study align with those in similar studies with clients and therapists (Dilgul et al., 2021; Bruno et al., 2022; Vincent et al., 2021). Future research should validate these findings quantitatively. Second, we recruited mental health clients who had received exposure therapy over telehealth. While this strategy may have resulted in biased client perceptions (i.e., positive opinions having undergone therapy before), their discussions of tele-VR aligned with those in similar research. In a survey of 184 clients with a range of anxiety-related conditions, only 60% had received exposure therapy but 90% were willing to try VRET because it seemed safe, effective, private, and customizable (Levy et al., 2023). To maximize generality, future research should examine the perspectives of clients who had received other therapies over telehealth and in-person. Third, clients in this study sample had never used VR for therapy. While clients discussed tele-VR speculatively, their pros, cons, and uses of tele-VR matched those described by expert VR clinicians, educators, and developers (Abbas et al., 2024; Cushnan et al., 2024). It will be important to understand the perspectives of clients who have completed tele-VR as part of formal treatment to evaluate first-hand insights. Lastly, while we achieved thematic saturation, the sampling approach does not support generalization to all mental health clients. Qualitative input should be sought from participants in future studies of telehealth-based VR therapy.

5 Conclusion

Clients who received exposure therapy over TMH had mostly positive preconceptions about VR, thought tele-VRET could add meaningfully to the client experience, and requested a wide range of specific features and functions for tele-VR to enhance the capabilities of TMH. Despite questions about logistics and costs, and doubts about perceived realism, clients were generally enthusiastic about how the immersion of VR and accessibility of TMH could combine to enhance mental healthcare experiences.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TO: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Project administration. JI: Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. HS: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JB: Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. MC: Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. BW: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis. BB: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R43MH129065.

Conflict of interest

Authors TO, JI, HS, JB, MC, BW, and BB were employed by Doxy.me Inc.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary materials

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2025.1595326/full#supplementary-material

References

Aafjes-Van Doorn, K., Békés, V., Luo, X., and Hopwood, C. J. (2024). Therapists’ perception of the working alliance, real relationship and therapeutic presence in in-person therapy versus tele-therapy. Psychother. Res. 34 (5), 574–588. doi:10.1080/10503307.2023.2193299

Abbas, J. R., Gantwerker, E., Volk, M., Payton, T., McGrath, B. A., Tolley, N., et al. (2024). Describing, evaluating, and exploring barriers to adoption of virtual reality: an international modified Delphi consensus study involving clinicians, educators, and industry professionals. J. Med. Ext. Real. 1 (1), 202–214. doi:10.1089/jmxr.2024.0022

Amestoy Alonso, B., Donegan, T., Calvis, I., Swidrak, J., Rodriguez, E., Vargas-Reverón, C. L., et al. (2024). Focus groups in the metaverse: shared virtual spaces for patients, clinicians, and researchers. Front. Virtual Real 5. doi:10.3389/frvir.2024.1432282

Antoniou, P. E., Varella, A., Pickering, J. D., Chatzimallis, C., Moumtzi, V., and Bamidis, P. D. (2024). Thematic analysis of stakeholder perceptions for co-creative healthcare XR resource design and development; traversing a minefield of opportunities. Front. Digital Health 6, 1341349. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2024.1341349

Arias, D., Saxena, S., and Verguet, S. (2022). Quantifying the global burden of mental disorders and their economic value. EClinicalMedicine 54, 101675. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101675

Baier, A. L., Kline, A. C., and Feeny, N. C. (2020). Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: a systematic review and evaluation of research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 82, 101921. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101921

Bar-Kalifa, E., Atzil-Slonim, D., Rafaeli, E., Peri, T., Rubel, J., and Lutz, W. (2016). Therapist-client agreement in assessments of clients’ functioning. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 84 (12), 1127–1134. doi:10.1037/ccp0000157

Batastini, A. B., Paprzycki, P., Jones, A. C. T., and MacLean, N. (2021). Are videoconferenced mental and behavioral health services just as good as in-person? A meta-analysis of a fast-growing practice. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 83, 101944. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101944

Benbow, A. A., and Anderson, P. L. (2019). A meta-analytic examination of attrition in virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 61, 18–26. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.06.006

Bernard, H. R., Wutich, A., and Ryan, G.W. (2016). Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Available online at: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/analyzing-qualitative-data/book240717

Boeldt, D., McMahon, E., McFaul, M., and Greenleaf, W. (2019). Using virtual reality exposure therapy to enhance treatment of anxiety disorders: identifying areas of clinical adoption and potential obstacles. Front. Psychiatry 10, 773. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00773

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis,” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology, vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Longet al. (Washington: American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport, Exerc. Health 11 (4), 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Bruno, R. R., Wolff, G., Wernly, B., Masyuk, M., Piayda, K., Leaver, S., et al. (2022). Virtual and augmented reality in critical care medicine: the patient’s, clinician's, and researcher's perspective. Crit. Care 26 (1), 326. doi:10.1186/s13054-022-04202-x

Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., and Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 42 (3), 294–320. doi:10.1177/0049124113500475

Chen, J-C., Liao, C-Y., Chen, M-H., Yu, T. H., Lu, Y. J., Wang, Y. C., et al. (2024). “Using virtual reality technologies to cope with grief and emotional resilience of absent loved ones,” in Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Medical and Health Informatics ACM, New York, NY, United States, September 09 2024, 73–77. doi:10.1145/3673971.3674018

Cikajlo, I., Cizman Staba, U., Vrhovac, S., Larkin, F., and Roddy, M. (2017). A cloud-based virtual reality app for a novel telemindfulness service: rationale, design and feasibility evaluation. JMIR Res. Protoc. 6 (6), e108. doi:10.2196/resprot.6849

Connolly, S. L., Ferris, S. D., Azario, R. P., and Miller, C. J. (2024). Patient and provider attitudes toward video and phone telemental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. (New York) 31 (4), 488–503. doi:10.1037/cps0000226

Cross, R. J. (2024). Meta quest virtual reality headsets can put your personal data at risk. Available online at: https://pirg.org/articles/meta-quest-virtual-reality-headsets-can-put-your-personal-data-at-risk/(Accessed November 11, 2024).

Cushnan, J., McCafferty, P., and Best, P. (2024). Clinicians’ perspectives of immersive tools in clinical mental health settings: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24 (1), 1091. doi:10.1186/s12913-024-11481-3

Deighan, M. T., Ayobi, A., and O’Kane, A. A. (2023). “Social virtual reality as a mental health tool: how people use VRChat to support social connectedness and wellbeing,” in Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems ACM, New York, NY, United States, April 19 2023, 1–13. doi:10.1145/3544548.3581103

Deng, W., Hu, D., Xu, S., Liu, X., Zhao, J., Chen, Q., et al. (2019). The efficacy of virtual reality exposure therapy for PTSD symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 257, 698–709. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.086

Dilgul, M., Hickling, L. M., Antonie, D., Priebe, S., and Bird, V. J. (2021). Virtual reality group therapy for the treatment of depression: a qualitative study on stakeholder perspectives. Front. Virtual Real. 1, 42. doi:10.3389/frvir.2020.609545

Dubreucq, J., Plasse, J., and Franck, N. (2021). Self-stigma in serious mental illness: a systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophr. Bull. 47 (5), 1261–1287. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa181

Fajnerova, I., Hejtmánek, L., Sedlák, M., Jablonská, M., Francová, A., and Stopková, P. (2024). The journey from nonimmersive to immersive multiuser applications in mental health care: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 26 (1), e60441. doi:10.2196/60441

Freitas, J. R. S., Velosa, V. H. S., Abreu, L. T. N., Jardim, R. L., Santos, J. A. V., Peres, B., et al. (2021). Virtual reality exposure treatment in phobias: a systematic review. Psychiatr. Q. 92 (4), 1685–1710. doi:10.1007/s11126-021-09935-6

Georgieva, I., and Georgiev, G. V. (2019). Reconstructing personal stories in virtual reality as a mechanism to recover the self. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (1), 26. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010026

Göttgens, I., and Oertelt-Prigione, S. (2021). The application of human-centered design approaches in health research and innovation: a narrative review of current practices. JMIR MHealth UHealth 9 (12), e28102. doi:10.2196/28102

Hilty, D. M., Randhawa, K., Maheu, M. M., McKean, A. J. S., Pantera, R., Mishkind, M. C., et al. (2020). A review of telepresence, virtual reality, and augmented reality applied to clinical care. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 5 (2), 178–205. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00126-x

Humbert, A., Kohls, E., Baldofski, S., Epple, C., and Rummel-Kluge, C. (2023). Acceptability, feasibility, and user satisfaction of a virtual reality relaxation intervention in a psychiatric outpatient setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1271702. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1271702

Jain, S. (2024). Trends shaping the health economy. Trilliant Health. Available online at: https://www.trillianthealth.com/market-research/reports/2024-health-economy-trends.

Jallah, J. K., Kanyal, D., Lalwani, L., Flahn, S. T. L., and Dweh, T. J. (2024). Navigating tomorrow’s healthcare: exploring the future of healthcare navigation with VR, AR, and emerging technologies: a comprehensive review. Multidiscip. Rev. 8 (5), 2025140. doi:10.31893/multirev.2025140

Kaimara, P., Oikonomou, A., and Deliyannis, I. (2022). Could virtual reality applications pose real risks to children and adolescents? A systematic review of ethical issues and concerns. Virtual Real 26 (2), 697–735. doi:10.1007/s10055-021-00563-w

Kostakos, P., Alavesa, P., Oppenlaender, J., and Hosio, S. (2019). “VR ethnography: a pilot study on the use of virtual reality “go-along” interviews in Google street view,” in Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia ACM, New York, NY, USA, November 26 2019, 1–5. doi:10.1145/3365610.3368422

Levy, A. N., Nittas, V., and Wray, T. B. (2023). Patient perceptions of in vivo versus virtual reality exposures for the treatment of anxiety disorders: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Form. Res. 7, e47443. doi:10.2196/47443

Lin, T., Heckman, T. G., and Anderson, T. (2022). The efficacy of synchronous teletherapy versus in-person therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Psychol. (New York) 29 (2), 167–178. doi:10.1037/cps0000056

Lindner, P. (2021). Better, virtually: the past, present, and future of virtual reality cognitive behavior therapy. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 14 (1), 23–46. doi:10.1007/s41811-020-00090-7

Lipschitz, J. M., Connolly, S. L., Van Boxtel, R., Potter, J. R., Nixon, N., and Bidargaddi, N. (2023). Provider perspectives on telemental health implementation: lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic and paths forward. Psychol. Serv. 20 (Suppl. 2), 11–19. doi:10.1037/ser0000625

Lopez, A., Schwenk, S., Schneck, C. D., Griffin, R. J., and Mishkind, M. C. (2019). Technology-based mental health treatment and the impact on the therapeutic alliance. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21 (8), 76. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1055-7

Mao, Q., Zhao, Z., Yu, L., Zhao, Y., and Wang, H. (2023). The effects of virtual reality–based reminiscence therapies for older adults with cognitive impairment: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 26 (1), e53348. doi:10.2196/53348

Matsangidou, M., Otkhmezuri, B., Ang, C. S., Avraamides, M., Riva, G., Gaggioli, A., et al. (2022). Now i can see me designing a multi-user virtual reality remote psychotherapy for body weight and shape concerns. Human–Computer Interact. 37 (4), 314–340. doi:10.1080/07370024.2020.1788945

Mondellini, M., Mottura, S., Guida, M., and Antonietti, A. (2021). Influences of a virtual reality experience on dissociation, mindfulness, and self-efficacy. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 24 (11), 767–771. doi:10.1089/cyber.2020.0223

Moshe-Cohen, R., Kivity, Y., Huppert, J. D., Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, K., et al. (2024). Agreement in patient-therapist alliance ratings and its relation to dropout and outcome in a large sample of cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Psychother. Res. 34 (1), 28–40. doi:10.1080/10503307.2022.2124131

Naslund, J. A., Mitchell, L. M., Joshi, U., Nagda, D., and Lu, C. (2022). Economic evaluation and costs of telepsychiatry programmes: a systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 28 (5), 311–330. doi:10.1177/1357633X20938919

Navas-Medrano, S., Soler-Dominguez, J. L., and Pons, P. (2023). Mixed Reality for a collective and adaptive mental health metaverse. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1272783. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1272783

NIMH (2023). Mental illness. Available online at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness (Accessed February 14, 2024).

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 16 (1), 1609406917733847. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

Oing, T., and Prescott, J. (2018). Implementations of virtual reality for anxiety-related disorders: systematic review. JMIR Serious Games 6 (4), e10965. doi:10.2196/10965

Ong, T., Barrera, J. F., Sunkara, C., Soni, H., Ivanova, J., Cummins, M. R., et al. (2024b). Mental health providers are inexperienced but interested in telehealth-based virtual reality therapy: survey study. Front. Virtual Real 5, 1332874. doi:10.3389/frvir.2024.1332874

Ong, T., Ivanova, J., Soni, H., Wilczewski, H., Barrera, J., Cummins, M., et al. (2024a). Therapist perspectives on telehealth-based virtual reality exposure therapy. Virtual Real 28 (2), 73. doi:10.1007/s10055-024-00956-7

Pardini, S., Gabrielli, S., Dianti, M., Novara, C., Zucco, G., Mich, O., et al. (2022). The role of personalization in the user experience, preferences and engagement with virtual reality environments for relaxation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (12), 7237. doi:10.3390/ijerph19127237

Pedram, S., Palmisano, S., Perez, P., Mursic, R., and Farrelly, M. (2020). Examining the potential of virtual reality to deliver remote rehabilitation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 105 (106223), 106223. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.106223

Peña, M. T., Lindsay, J. A., Li, R., Deshmukh, A. A., Swint, J. M., and Morgan, R. O. (2024). Telemental health use is associated with lower health care spending among Medicare beneficiaries with major depression. Med. Care 62 (3), 132–139. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001952

Piao, J., Huang, Y., Han, C., Li, Y., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., et al. (2022). Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 31 (11), 1827–1845. doi:10.1007/s00787-022-02040-4

Raskind, I. G., Shelton, R. C., Comeau, D. L., Cooper, H. L. F., Griffith, D. M., and Kegler, M. C. (2019). A review of qualitative data analysis practices in health education and health behavior research. Health Educ. Behav. 46 (1), 32–39. doi:10.1177/1090198118795019

Russell, B. H., Wutich, A., and Ryan, G. W. (2016). Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. SAGE Publications.

SAMHSA (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 national survey on drug use and health. Subst. Abuse Ment. Health Serv. Adm. Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR102121.htm.

Segawa, T., Baudry, T., Bourla, A., Blanc, J. V., Peretti, C. S., Mouchabac, S., et al. (2019). Virtual reality (VR) in assessment and treatment of addictive disorders: a systematic review. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1409. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.01409

Simón-Vicente, L., Rodríguez-Cano, S., Delgado-Benito, V., Ausín-Villaverde, V., and Cubo Delgado, E. (2024). Cybersickness. A systematic literature review of adverse effects related to virtual reality. Neurol. Engl. Ed. 39 (8), 701–709. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2022.04.007

Slater, M., Banakou, D., Beacco, A., Gallego, J., Macia-Varela, F., and Oliva, R. (2022). A separate reality: an update on Place Illusion and Plausibility in virtual reality. Front. Virtual Real 3. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.914392

Snoswell, C. L., Chelberg, G., De Guzman, K. R., Haydon, H. M., Thomas, E. E., Caffery, L. J., et al. (2023). The clinical effectiveness of telehealth: a systematic review of meta-analyses from 2010 to 2019. J. Telemed. Telecare 29 (9), 669–684. doi:10.1177/1357633X211022907

Taveira, M. C., de Sá, J., and da Rosa, M. G. (2022). Virtual reality-induced dissociative symptoms: a retrospective study. Games Health 11 (4), 262–267. doi:10.1089/g4h.2022.0009

Thompson, A., Calissano, C., Treasure, J., Ball, H., Montague, A., Ward, T., et al. (2023). A case series to test the acceptability, feasibility and preliminary efficacy of AVATAR therapy in anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 11 (1), 181. doi:10.1186/s40337-023-00900-1

Tukur, M., Schneider, J., Househ, M., Dokoro, A. H., Ismail, U. I., Dawaki, M., et al. (2023). The metaverse digital environments: a scoping review of the challenges, privacy and security issues. Front. Big Data 6, 1301812. doi:10.3389/fdata.2023.1301812

van Gelder, J.-L., Cornet, L. J. M., Zwalua, N. P., Mertens, E. C. A., and van der Schalk, J. (2022). Interaction with the future self in virtual reality reduces self-defeating behavior in a sample of convicted offenders. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 2254. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-06305-5

van Minnen, A., Ter Heide, F. J. J., Koolstra, T., de Jongh, A., Karaoglu, S., and Gevers, T. (2022). Initial development of perpetrator confrontation using deepfake technology in victims with sexual violence-related PTSD and moral injury. Front. Psychiatry 13, 882957. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.882957

Vigo, D., Jones, L., Atun, R., and Thornicroft, G. (2022). The true global disease burden of mental illness: still elusive. Lancet Psychiatry 9 (2), 98–100. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00002-5

Vincent, C., Eberts, M., Naik, T., Gulick, V., and O’Hayer, C. V. (2021). Provider experiences of virtual reality in clinical treatment. PLoS One 16 (10), e0259364. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259364

Weller, S. C., Vickers, B., Bernard, H. R., Blackburn, A. M., Borgatti, S., Gravlee, C. C., et al. (2018). Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PLoS One 13 (6), e0198606. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198606

Wray, T. B., and Emery, N. N. (2022). Feasibility, appropriateness, and willingness to use virtual reality as an adjunct to counseling among addictions counselors. Subst. Use Misuse 57 (9), 1470–1477. doi:10.1080/10826084.2022.2092148

Keywords: virtual reality, exposure therapy, telemental health (TMH), tele-VR, immersive telehealth, mental health patients

Citation: Ong T, Ivanova J, Soni H, Barrera J, Cummins M, Welch BM and Bunnell BE (2025) Mental health clients’ perspectives on telehealth-based virtual reality therapy. Front. Virtual Real. 6:1595326. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2025.1595326

Received: 17 March 2025; Accepted: 30 April 2025;

Published: 30 May 2025.

Edited by:

Gerrit Meixner, Heilbronn University, GermanyReviewed by:

Patricia Pons, Instituto Tecnológico de Informática (ITI), SpainJulia Elisabeth Diemer, kbo Inn Salzach Klinikum, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Ong, Ivanova, Soni, Barrera, Cummins, Welch and Bunnell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Triton Ong, dHJpdG9uLm9uZ0Bkb3h5Lm1l

†ORCID: Triton Ong, orcid.org/0000-0002-2512-2026; Julia Ivanova, orcid.org/0000-0002-5852-200X; Hiral Soni, orcid.org/0000-0002-2054-3737; Janelle Barrera, orcid.org/0000-0002-1010-6365; Mollie Cummins, orcid.org/0000-0001-7078-8479; Brandon M. Welch, orcid.org/0000-0002-2214-9282; Brian E. Bunnell, orcid.org/0000-0002-4964-0688

Triton Ong

Triton Ong Julia Ivanova

Julia Ivanova Hiral Soni

Hiral Soni Janelle Barrera

Janelle Barrera Mollie Cummins1,3†

Mollie Cummins1,3† Brian E. Bunnell

Brian E. Bunnell