- 1 SensorLab, Chemistry Department, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

- 2 Molecular Sciences and Biochemistry, Biotechnology Department, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

Biochar, a carbon-rich substance produced through biomass pyrolysis, has attracted considerable interest due to its wide-ranging applications, including in electrochemical sensing and biosensing. Their distinctive physicochemical characteristics, such as a large surface area, adjustable porosity, plentiful functional groups and outstanding electrical conductivity, render it a promising choice for electrode materials and sensor systems. The integration of biochar into composite materials alongside metals, metal oxides, polymers and nanomaterials has further augmented its electrochemical capabilities, leading to enhancements in sensitivity, selectivity and stability in sensing applications. This review offers an extensive summary of recent developments in biochar-based electrochemical sensors and biosensors, concentrating on their design, functionalization techniques and use in detecting biomolecules, environmental contaminants and electroactive species. We explore the fundamental mechanisms that drive biochar’s electrochemical behavior and underscore the collaborative effects between biochar and various composite materials in boosting sensor efficiency. Furthermore, we delve into the challenges and future prospects of biochar-based sensing technologies, highlighting their potential for creating sustainable and cost-effective analytical tools.

1 Introduction

Despite growing interest in sustainable and low-cost materials for sensor development, there is a significant gap in the consolidated scientific understanding and application of nanobiochar in electrochemical sensing technologies. While a limited number of studies have demonstrated its promising physicochemical properties such as high surface area, electrical conductivity and surface functionalization potential the broader scope, mechanisms and innovations in nanobiochar-based electrochemical sensors and biosensors remain underexplored and underreported in literature. This review aims to address this technological and knowledge gap by systematically analysing and compiling current advancements, challenges and opportunities in the use of nanobiochar for sensing applications, ultimately guiding future research and application in this emerging field.

The first studies of biochar were reported in 1999 and extensive research on the material started in 2010 which advanced to a reactivity study stage in 2014 (Wu L. et al., 2019). A range of biomass feedstocks or organic waste can be thermochemically converted to produce biochar. Because the properties of biochar vary based on the biomass feedstock material, synthesis technique, temperature, and other pre-or post-processing parameters, researchers are interested in a broad range of applications (Kalus et al., 2019). The long-term sustainability of biomass as an effective substitute for non-renewable carbon sources depends on the development of scalable and ecologically friendly biomass conversion technologies. (Natasha et al., 2022; Hilbert and Soentgen, 2020). One recent field of research that potentially offers direction for this work is green chemistry (Zimmerman et al., 2020).

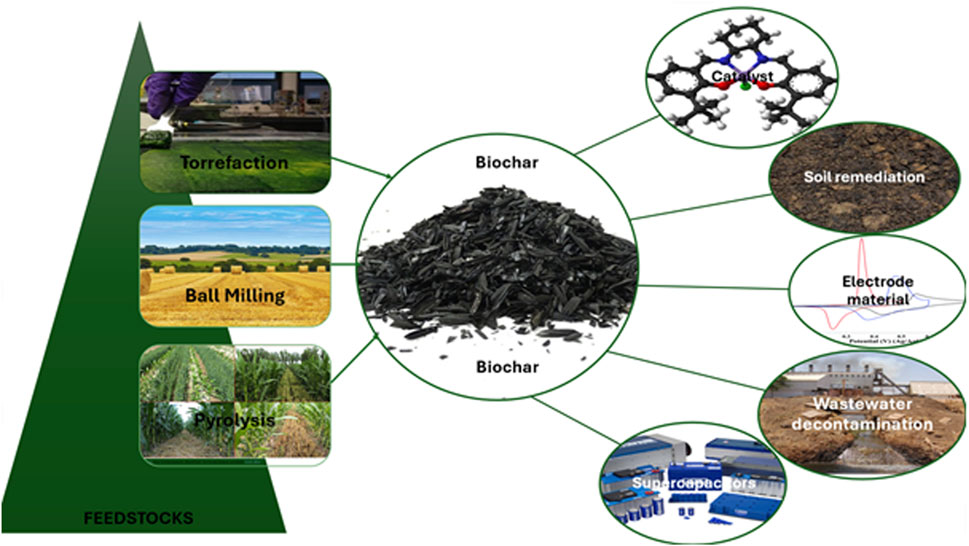

Green chemistry encourages lower energy waste, consumption and solvent use, all of which result in cost savings in biomass treatment operations (Anastas and Kirchhoff, 2002). Although there are numerous biochar green approaches described in the literature, such as ball milling, torrefaction, microwave pyrolysis and conventional pyrolysis, the correct classification is still lacking (Kataya et al., 2023; Velusamy et al., 2021). Following the synthesis of biochar, it is common practice to employ a top-down method, which deconstructs the macrostructure to the nanoscale thus producing nanobiochar with particle sizes less than 100 nm (Gaudino et al., 2019). In a nutshell, nanobiochar is a nanoscale biochar material with enhanced surface area, chemical and physical characteristics. Some of the special qualities of nanobiochar that make it suitable for a range of applications include their functional groups, high cation exchange capacity, wide surface area, high porosity and stability (Salaria et al., 2024; Liu J. et al., 2023). Nanobiochar have attracted a lot of attention for its agronomical and environmental benefits in agroecosystems due to its ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while generating a variety of co-benefits. (Li and Imran, 2024). These materials can also serve as precursors for the synthesis of electrode materials and catalysts for sensors and microbial fuel cells (Rahman and Bakri, 2024).

Even though there are few studies exhibiting this fact, there are however several appealing properties of nanobiochar for the development and the improvement of nanobiochar-based electrochemical sensors (Yan et al., 2014; Chausali et al., 2021). In the last 10 years several review articles have been published to better explain the findings of previous studies and to carry out more intricate research on nanobiochar (Bhandari et al., 2023). For example, Khare (2021) discovered that the inherent characteristics of nanobiochar may be easily modified and used as a foundation for the production of a wide range of functional materials that are presently employed in many applications. These include their role in energy storage, their use as adsorbents, as catalysts and in sensor construction. This is because of their high active loading and fast mass transfer fluxes. Furthermore, research conducted by Verma N. et al. (2023) summarized multifunctional nanobiochar paper-based electrochemical sensors that can be used for detecting contaminants in freshwater, the ocean and other environmental matrices. Also, Chausali et al. (2021) reviewed a paper on an immunosensing device based on biochar which was designed by attaching anti-microcystin-LR (anti-MC-LR) antibodies to highly conductive and dispersible nanobiochar particles on filter paper using a technique known as dipping-drying in order to detect MCLR toxins in water. Nanobiochar sensor research holds promise for high-value uses in developing fields like analyte-focused electrochemistry and in the production of electrochemical biosensors.

Existing literature on electrochemical sensors and biosensors predominantly focuses on the use of conventional carbon-based nanomaterials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes and activated carbon (Udomkun et al., 2024). While these materials offer excellent electrochemical performance, their production is often energy-intensive, costly and environmentally taxing (Liu W. et al., 2019). In contrast, nanobiochar a sustainable, low-cost and eco-friendly alternative derived from biomass waste has only recently gained attention, with limited yet promising studies demonstrating its viability for sensor development (Bressi, 2023; Raza et al., 2024). Most current reviews (Li M. et al., 2022) either focus broadly on biochar for environmental remediation or touch only briefly on its electrochemical potential, without providing a comprehensive synthesis of its role as a nanostructured sensing material. Additionally, few sources delve into the functionalisation, fabrication strategies and performance optimisation of nanobiochar-based sensors (de Jesus et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2023). This review contributes a novel perspective by specifically targeting nanobiochar-based electrochemical and biosensor applications, offering a systematic evaluation of its unique material properties, sensing capabilities, and advantages over traditional materials (Kumar and Krishnamoorti, 2010). The review further identifies critical research gaps, discusses scalability and environmental sustainability, and proposes future research directions making it a timely and significant contribution to the development of green sensor technologies in environmental monitoring, biomedical diagnostics and food safety (Alsaiari et al., 2023).

2 Fabrication of nanobiochar

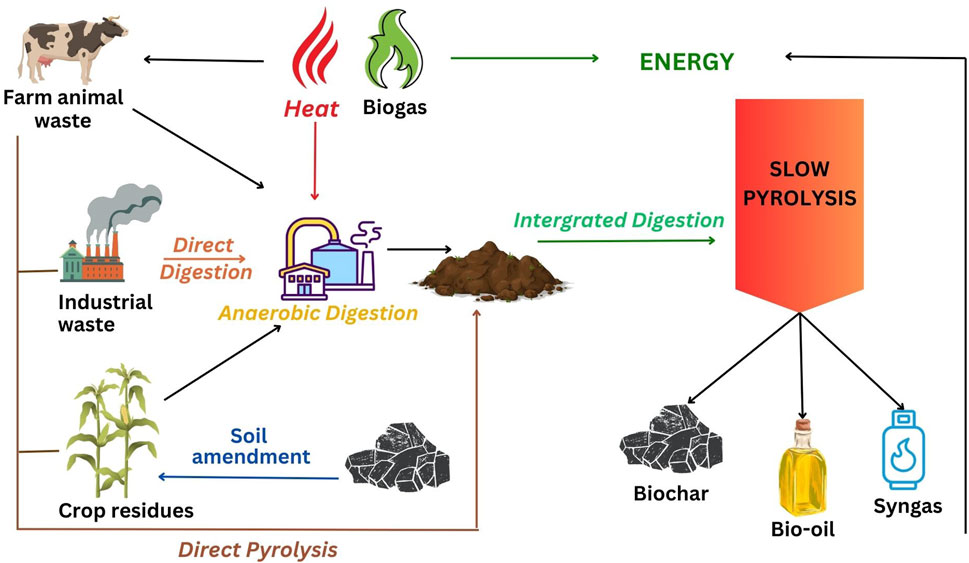

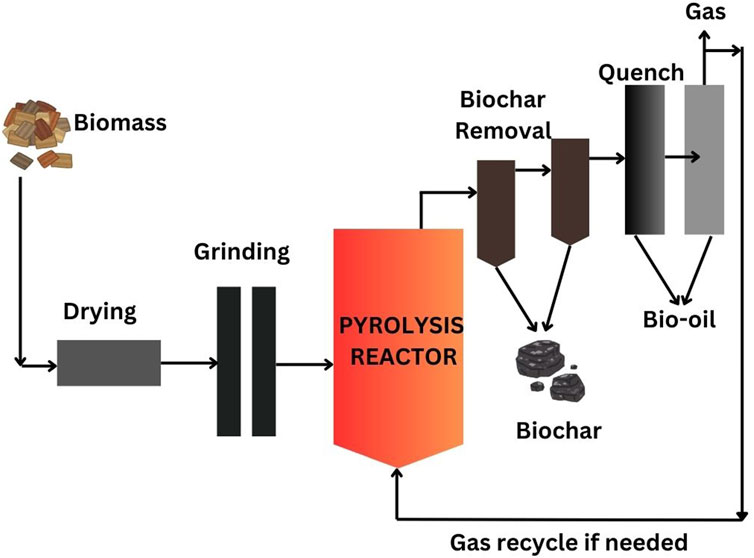

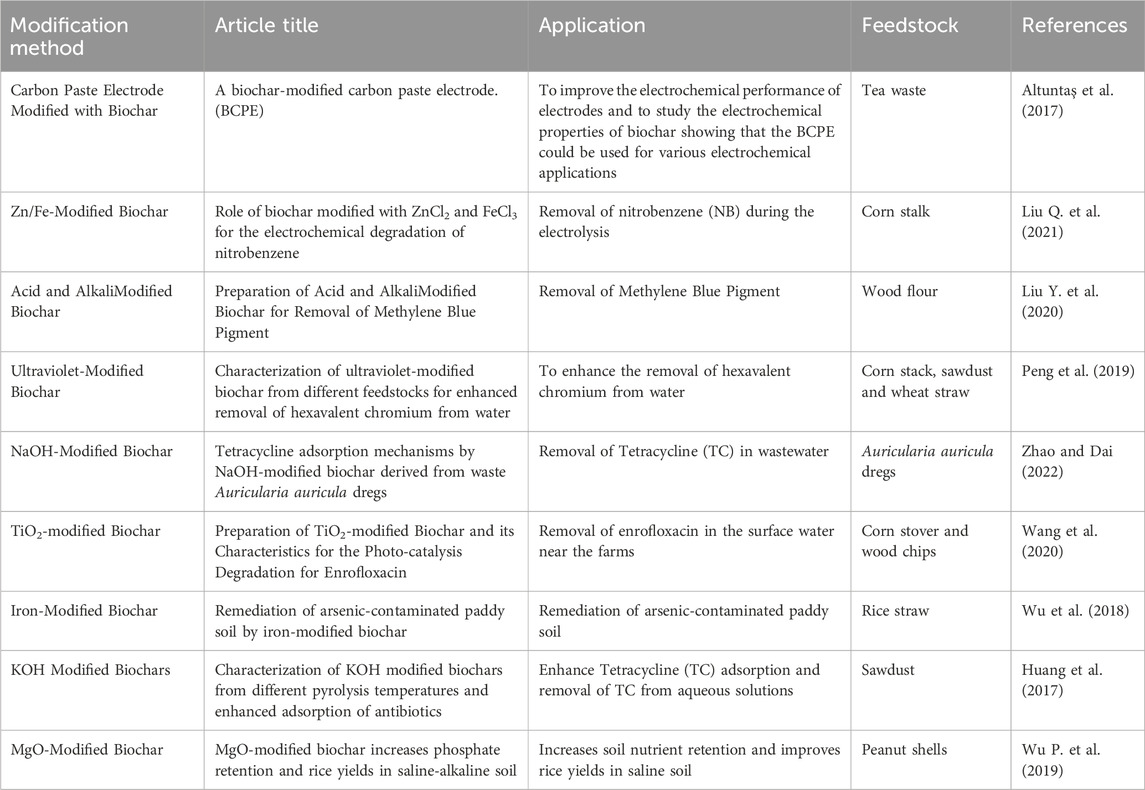

Nanobiochar are sophisticated nanostructured substances, initially fabricated from solid residue of biomass that have been thermally broken down at temperatures between 350 °C and 600 °C (Nosratabad et al., 2024). Because of its amorphous atomic structure, biochar has a porous matrix with many exposed surfaces and pores. It is made from lignocellulosic biomass, which includes animal waste, stable waste, wood and agricultural wastes employing a range of thermochemical processes, including ball milling, torrefaction, flash and microwave pyrolysis, slow, fast pyrolysis and more (Yu et al., 2024). Additionally, lignocellulosic materials have also shown to be able to create more biochar than municipal waste (Emenike et al., 2024) and can be modified chemically and physically to improve its efficacy for a range of purposes (Wang and Wang 2019).

Biochar reduces emission of greenhouse gases, improves sensor sensitivity and selectivity and increases porosity content and capacity (Zhang and Dai, 2022). The availability of inexpensive feedstock materials makes it possible to produce biochar for a wide scale of sensing applications (Levchenko et al., 2022). New materials with improved sensing capabilities may be created by fusing biochar technology with new developments like biotechnology and nanotechnology (Spanu et al., 2020). The particle sizes of the produced biochar vary from hundreds of micrometers to several centimeters, depending on the technique used. The characteristics of biochar can be improved by reducing their particle size to the nanoscale area (Sarma et al., 2024). For particles smaller than 100 nm, a larger surface to volume ratio increases surface energy and consequently, their biological effectiveness (He et al., 2010). Using the various methods depicted in Figure 1, nanobiochar may be produced from regular biochar using simple techniques often considered as green synthesis techniques or methods.

Currently, green synthesis techniques and energy-saving nanotechnology strategies are used for most nanobiochar production and research (Ashfaq et al., 2024). According to Habib et al. (2023), the proposed method satisfies half of the 12 green chemistry metrics principles, namely,; waste prevention, high atom economy, avoiding hazardous chemical processes, using fewer toxic solvents and auxiliaries, employing renewable sources and product biodegradability. The high input energy, expensive precursors and intricate procedures needed in existing nanomaterial manufacturing methods must thus be compensated for by low-cost and environmentally friendly technologies (Baig et al., 2021; Levchenko et al., 2022). However, it is crucial to discuss various biochar development techniques and its modification (Figure 2), since biochar production is the original step before discussing the modification of biochar into nanobiochar.

2.1 Green approaches for the production of biochar

2.1.1 Torrefaction

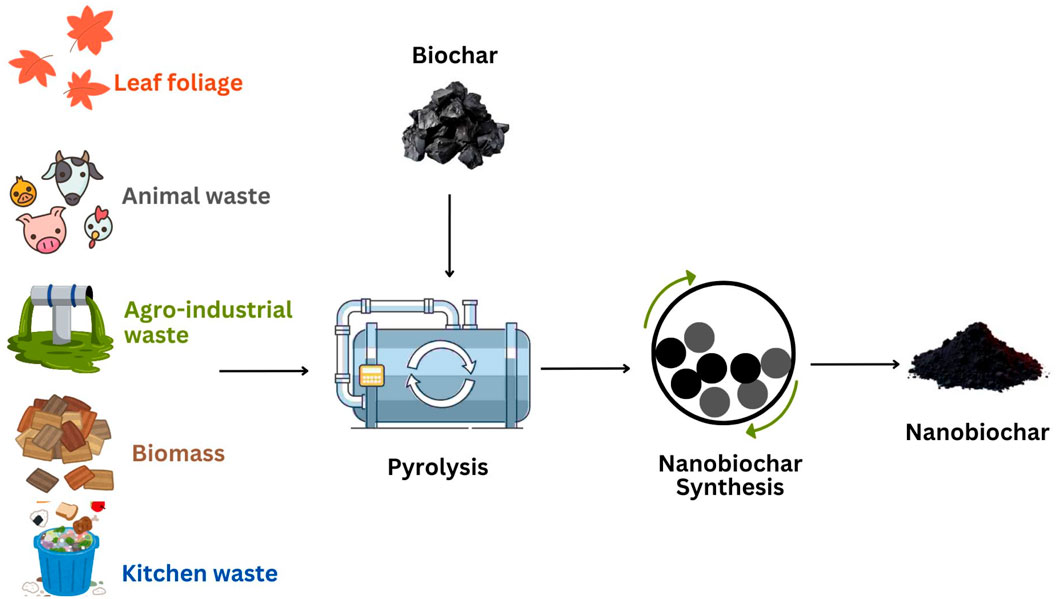

Torrefaction is the process of gradually heating biomass in an inert or oxygen-deficient environment to temperatures between 200 °C and 300 °C (Yang et al., 2024) at atmospheric pressure (Quirino et al., 2023). Biochar is yielded by this process since biomass partially decomposes, producing non-condensable and condensable gases (Figure 3). The end result is a solid carbon-rich substance known as biochar, biocarbon or torrefaction biomass (Onyenwoke, 2024). The torrefaction process is influenced by a number of variables, including air pressure, moisture content, feedstock adaptability, residence time, reactor environment, heating rate and reaction temperature (Ivanovski et al., 2023). Biomass is usually pre-dried to a moisture content of 10% before torrefaction (Thengane et al., 2022). Furthermore, the particle size of the feedstock affects the kinetics and the residence time for a given heating rate and the reaction processes (Medic et al., 2012).

Figure 3. Illustration of the torrefaction process of the biochar production; where Qo is the initial heat input and QT is the total heat requirement.

The torrefaction is a practical technique for improving biomass’s qualities that are comparable to those of solid coal by raising the calorific value of biochar. Because it improves raw biomass’s chemical, physical and biological characteristics, it has certain benefits over other pre-treatment techniques and improves its performance in co-firing, gasification and combustion (Mpungu et al., 2024). Torrefied wood and volatiles, which tend to be more stable and carbon-rich solid products, may be produced by means of this process as the hemicellulose part of wood breaks out down (Ong et al., 2021). Several studies, including that by Sun et al. (2023) demonstrated that the torrefaction technology is an effective method for creating high quality torrefied wood pellets as compared to raw controlled pellets. Some studies on the torrefaction of forest and agricultural residues use thermogravimetric, calorific, proximate fibre, elemental scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis to study the torrefaction of the agricultural wastes, namely,; rice husk, sawdust and coffee residue. They then examined how torrefaction affected the structure and characteristics of biomass (Olugbade and Ojo, 2020). Biochar and solid fuels produced from biomass are improved in quality through the torrefaction process achieved under dry or wet conditions (Sarker et al., 2021). Biochar properties derived from biomass via torrefaction can be used to build biochar-based devices used in various approaches, such as supercapacitors, electrochemical sensors, fuel cells, biosensors, and batteries (Saravanan and Kumar 2022).

2.1.2 Ball milling

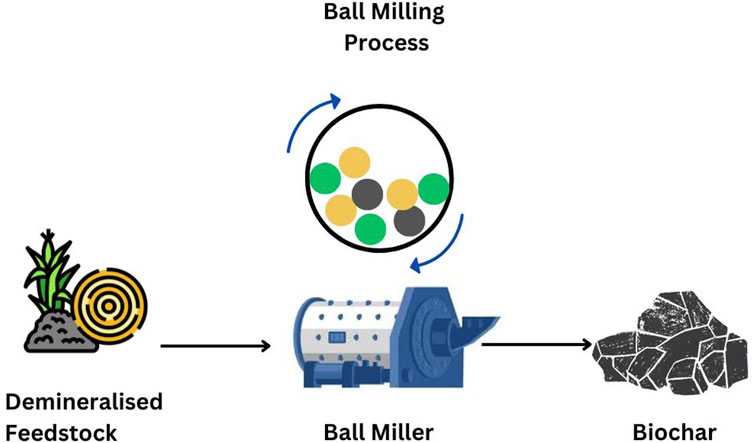

Ball milling (Figure 4) is the traditional method for isolating representative lignin in biomass cell walls (Yang F. et al., 2021). Different ball milling times are used on gramineous material (bamboo residues), sawdust (hardwood) and larch sawdust (softwood) (Ebringerová et al., 2005). In addition to producing particles as fine as 10 microns, this technique has the advantage of running continuously forming biochar typically between 1 and 6 h (Etafa et al., 2025).

Biochar formed from biomass and biochar-nanoparticle composites benefit from the ball milling method’s improved physicochemical characteristics which enhances its sorption capabilities (Amusat et al., 2023). Because of the synergistic benefits of biochar and nanoparticles, biochar-based nanomaterials may efficiently adsorb heavy metals, dyes and emerging organic contaminants in water and wastewater (Damahe et al., 2024). Multifunctional and highly effective procedures based on nanotechnology are required to remove a variety of compounds, the majority of which are persistent and have the ability to bioaccumulate as the concern for environmental pollutants becomes more prevalent (Bhatt et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the electrochemical catalytic activity of ball-milled biochar has not been well investigated. This information is important because the pore network and surface area of electrode materials are important factors in increasing their catalytic activity (Wang et al., 2024). Because of their superior surface qualities, ball-milled biochar may be utilised as the perfect electrode materials for energy applications (Raj et al., 2024).

A good example of these properties is illustrated in a research study conducted by Ambaye et al. (2023) involving the electrochemical characteristics of ball-milled biochar on glassy carbon electrodes. This study revealed improvements in physicochemical characteristics, including a greater surface area, a plentiful pore system and more functional groups that contain oxygen. There was approximately a 2.05-fold increase in the surface area observed with a pore volume increase by approximately 2.39-fold (Lyu et al., 2019). According to this study, ball-milled biochar was labelled as potential carbon materials for inexpensive and high-efficiency electrodes.

2.1.3 Pyrolysis

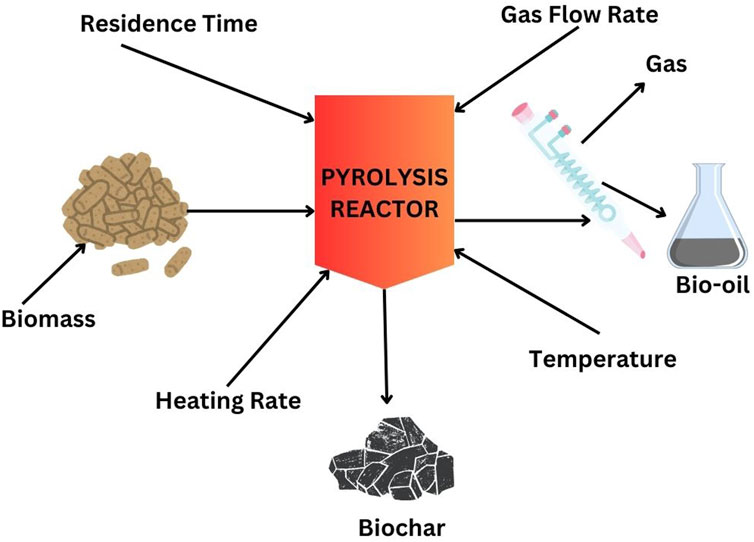

One process that contributes to the production of charcoal is pyrolysis, which is the incomplete burning of wood a type of charcoal also known as biochar (Bayar et al., 2024). Under low pressure (10–50 kPa) and moderate temperature (300 °C–1000 °C) pyrolysis, a thermochemical decomposition process, can transform a variety of organic waste materials into stable, high-energy liquid products (bio-oil), chemical derivatives (gas) and valuable residual solids (biochar) (Adeoye et al., 2023). In contrast to conventional recycling and recovery techniques which simply remove potentially valuable items for re-use, this process converts hydrocarbon waste materials into value-added products (Al-Salem et al., 2010). Only recently has moderate-temperature pyrolysis become a practical method, with various research entities across the world already transforming plants, agricultural residue, and other types of municipal waste (Ufitikirezi et al., 2024). Without the presence of oxygen or other oxidants, the process involves the thermal breakdown of a solid (or liquid) into smaller volatile molecules. During this treatment process, materials are heated to extremely high temperatures, and in the absence oxygen, they split into distinct molecules by physical and chemical processes (Mouneir and El-Shamy, 2023). The most essential point to remember is that the pyrolysis process alters the material being pyrolyzed, thus the final product and original reactant have different chemical compositions (Morgan and Kandiyoti, 2014).

In contrast, extreme pyrolysis occurring at temperatures often reaching between 1200 °C and 1600 °C and pressures above 5 MPa (50 bar) results in carbonization, which is the production of carbon as a residue. Pyrolysis does not need the use of water, oxygen or any other reagents, as opposed to other high-temperature reactions like hydrolysis and combustion (Liu G. et al., 2023). Yet, every pyrolysis system experiences some degree of oxidation since an oxygen-free environment is not always achievable. It is also believed that pyrolysis is the initial step in other related processes, such as gasification and combustion (Al-Haj Ibrahim., 2020). An organic molecule can also undergo pyrolysis to produce a solid residue that is high in carbon as well as a number of volatile chemicals (Chen J. et al., 2024). One method for making use of renewable resources is pyrolysis (Ho and Show, 2015). A wide range of feedstocks may be processed with the use of this straightforward, inexpensive method (Yana et al., 2022). Pyrolysis reduces greenhouse gas emissions and landfill trash. By generating energy from home sources, it can lessen the nation’s need on foreign energy supplies (Ali et al., 2024). The pyrolysis method is less costly than landfill disposal for waste management since building a pyrolysis power plant is an easy procedure (Hung et al., 2023). Depending on the volume of garbage produced in various areas, it may provide low-income people with new employment opportunities, which may improve public health by reducing waste (Khan et al., 2022). Furthermore, biochar pyrolysis can occur through a variety of methods with varied operating parameters in temperature, namely, microwave pyrolysis, flash pyrolysis, vacuum pyrolysis and conventional pyrolysis (Vuppaladadiyam et al., 2022). Each process will be discussed at length in the below sections.

2.1.3.1 Microwave pyrolysis

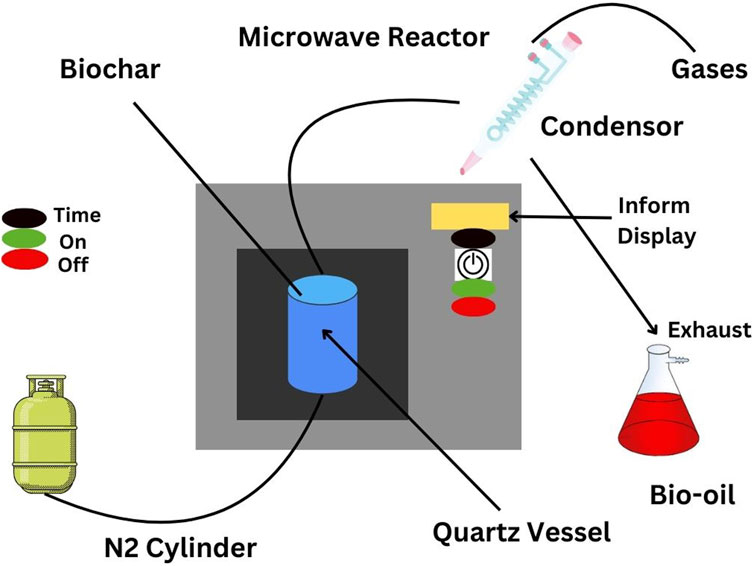

Microwave pyrolysis (Figure 5) is the term used for electromagnetic radiation with frequencies between 0.3 and 300 GHz and wavelengths that range from as long as 1 m to as short as 1 mm (Li et al., 2016). This microwave-based technology is an alternative heating method that has been successfully used in biomass pyrolysis for the production of biochar and biofuel in the past due to its rapid, accurate, volumetric and efficient heating (Singh A. et al., 2024; Usman and Cheng, 2024).

The reaction parameters have an impact on the properties and yields of the biochar produced by microwave-assisted pyrolysis of organic waste, such as the temperature at which the reaction occurs, the microwave absorbent, the microwave power and other factors (Ren et al., 2022). Even though microwave pyrolysis of small batch size feedstocks has been extensively studied, there is a growing need to understand the intricacies of the parameters employed in a pilot-scale microwave pyrolysis process (Rasaq et al., 2024). According to earlier studies, raising the microwave power the reaction temperature (300 °C–800 °C for biochar production and 500 °C–900 °C for bio-oil and syngas production) decreases the production of biochar while encouraging the development of porous structures (Lin et al., 2022). Optimizing the production and quality of biochar is greatly influenced by reactor designs, operating parameters and feedstock properties. Higher heating values increase biochar yield while increasing microwave absorbent load. Decreasing it provides a comprehensive practical analysis of microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass and its biochar properties, including biochar properties, product distribution, biochar yield and microwave absorbers (Ke et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024).

Kuo et al. (2023) investigated the effect of heating duration and the microwave power on the production of biochar from rice husk, an agricultural waste, using microwave pyrolysis. The results revealed that the microwave power, as well as the combination of heating duration and microwave power, had a beneficial influence on the maximum biochar output. Rice husk microwave pyrolysis yielded high-quality biochar, which could be used as soil amendment nutrient captive mediums, in sensor development and as energy sources (Potnuri et al., 2023). Because of its distinct energy transfer method, quick and even molecular heating, fast and precise heating, and simplicity of control with great energy economy; microwave technology has become more and more popular in recent years. As a result, some researchers recommend microwave pyrolysis over traditional pyrolysis (Zhang et al., 2024; Lee, 2024). Unfortunately, the literature has limited studies on the use of microwave pyrolysis for biomass conversion and its use in the development of sensor technology.

2.1.3.2 Vacuum pyrolysis

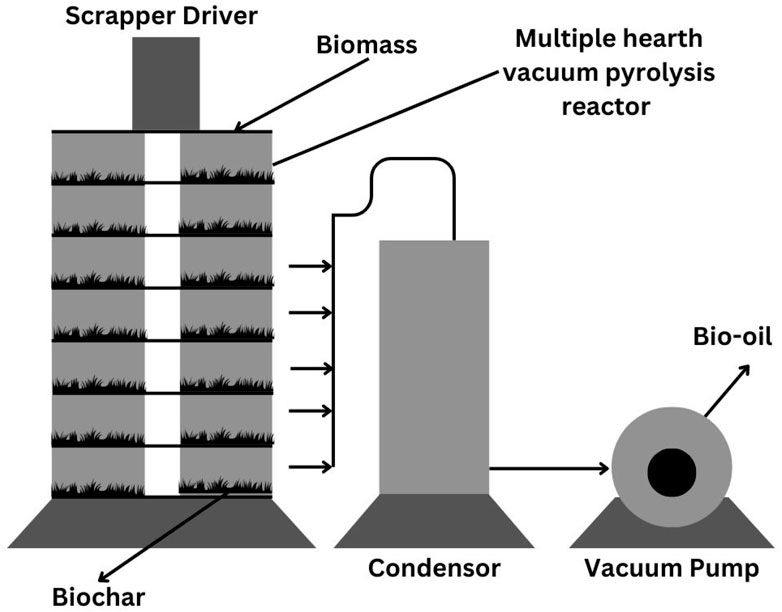

Vacuum pyrolysis (Figure 6) is the thermal decomposition of a feedstock without oxygen and under low pressure, with the major products being biochar, bio-oil, water, and non-condensable gases (Sahoo et al., 2021). The produced biochar contains a large amount of energy and may be used as a fuel. The bio-oil also contains a large number of chemical compounds that may be isolated and marketed as high-value chemicals. Furthermore, vacuum pyrolysis; which operates similarly to atmosphere pyrolysis requires a quick rate of heating with a very small biomass feed size. It should be carried out in an airless environment at significantly lower atmospheric pressures to produce biofuels (Divyangkumar et al., 2024). As a result, vacuum pyrolysis allows for the production of biochar without having to deal with the issue of biochar burning due to its small particle size, which often makes biochar difficult to handle (Potnuri et al., 2023). A higher carbon output, a surface that is more sensitive to oxidants, and a shorter residence time for volatile chemicals that might obstruct pores during their secondary charring reaction, are some advantages of vacuum pyrolysis. Therefore, it is expected that vacuum pyrolysis produced biochar would have a more open pore structures and be better feedstock for the synthesis of activated carbon (Mishra D. et al., 2023).

Additionally, the physicochemical characteristics of vacuum prepared biochar, especially for use as electrodes in electrochemical energy storage processes, has not been extensively studied (Senthil and Lee, 2021). Nonetheless, using vacuum pyrolysis, Zhang et al. (2024) investigated a wood biochar electrode developed from cotton rosewood, resulting in a special hierarchically porous structure. By contrasting wood biochar with nitrogen atmospheric pyrolysis biochar, the study aimed to comprehend how vacuum circumstances affect the physicochemical characteristics of wood biochar. Finally, the electrodes' electrochemical performance of the vacuum pyrolysis synthesised biochar was evaluated (Abad et al., 2023). In this study the biochar electrodes showed stable redox behavior, making them reliable for long-term applications in sensing and energy storage. Furthermore, due to a higher degree of graphitization, vacuum pyrolyzed biochar electrodes exhibited lower charge transfer resistance and enhanced electrical conductivity compared to the use of biochar produced under atmospheric conditions.

2.1.3.3 Conventional pyrolysis

Conventional pyrolysis (Figure 7) generates more charcoal than liquid and gaseous products by exposing biomass to high (500 °C–800 °C) or low (300 °C–500 °C) temperatures in the absence of an oxidizing agent (Uddin et al., 2018). Depending on the operating circumstances, there are three subclasses of the pyrolysis process, namely, slow pyrolysis, rapid pyrolysis and flash pyrolysis (Elorf et al., 2021). The dominant method at the moment is fast or flash pyrolysis, which occurs at extreme temperatures with a very short residence period which thus has an impact on the makeup of their goods.

Heating, bond-splitting, and conversion are the steps involved in the conventional pyrolysis reaction (Dadi et al., 2023). The heating of the feedstock or substrate is the main factor that causes bond-splitting, which eventually leads to chemical conversion. During heating, the feedstock or substrate is exposed to high temperatures without oxygen (Magaji et al., 2024). The kind of material or feedstock determines the heating temperature since various materials breakdown at different temperatures. Although heating temperatures for some materials, such as olive waste, can range from 150 °C to 1050 °C, however pyrolysis needs at least 300 °C (Elorf et al., 2021). In the second step, bond-splitting or bond-breaking in the pyrolysis process initiates chemical reactions. Under the influence of heat, the new simpler compounds are created as the substrate’s complex molecules and compounds start to break down and degrade (Dadi et al., 2023). Polymers are converted to monomers at this point, and the majority of the substrate’s volatile components are made accessible (Catenacci et al., 2022). Chemical conversion is the last stage of pyrolysis because it produces significant by-products with a broad range of industrial functions. The substrate compounds' chemical bonds keep breaking during conversion, resulting in relatively small molecules (Zheng et al., 2023) which can react to produce new compounds.

2.1.3.3.1 Slow pyrolysis

For thousands of years, charcoal has been produced via slow pyrolysis, a traditional pyrolysis technique that maintains a moderate heating rate (Rodrigues et al., 2023). When in comparison to gaseous and liquid products, the biochar output from slow pyrolysis is the greatest, making it a method that is both energy-efficient and robust (Kim et al., 2019). This process is commonly used for small-scale or farm-based biochar manufacturing. An optimal temperature, a modest heating rate (0.1 °C–10 °C min-1) and a lengthy residence period (a few minutes to hours) that ranges from temperatures of 300 °C–700 °C; are all characteristics of slow pyrolysis that remove vapours throughout the process of heating (Amonette et al., 2023). As expected, the main product is biochar with a moderate heating rate that lessens the thermal cracking process in lignin biomasses and lignocellulosic materials (Tripathi et al., 2016). The temperature and the rate of heating have a significant impact on the quality of biochar. If the heating rate is less than 10 °C min-1, then the structure of the biomass changes and its chemical bonds are disrupted. This results in a more rigid matrix that prevents the formation of volatile materials. According to a study by Wang et al. (2022), the volatile matter of biochar drops from 25.2% to 11.6% at a heating rate of 10 °C min-1 whilst (Afshar and Mofatteh, 2024) claims that slow pyrolysis is a dependable and energy-efficient technique. During slow pyrolysis, the highest amount of biochar is produced in comparison to gaseous and liquid products (Figure 8).

2.1.3.3.2 Fast pyrolysis

Fast pyrolysis (Figure 9) produces various reaction circumstances that result in different intended products than slow pyrolysis (Amenaghawon et al., 2021). Fast pyrolysis produces pyrolysis vapour and biochar by quickly heating biomass from 600 °C to 1000 °C in an oxygen-free atmosphere. To maximize the production of bio-oil, it uses rapid heating rates from 10 to 10,000 C min–1 and has a short residence time of 0.5–5 s (Sharma M. et al., 2024). When biochar is a by-product, the method yields around 60% bio-oil (Figure 9) in a matter of seconds. High pyrolysis temperatures and heating rates enhance the emission of volatile gaseous materials while decreasing the output of biochar. The pyrolysis vapour generated is quickly extracted via the pyrolysis reactor once the biomass is heated quickly (Vuppaladadiyam et al., 2023). The quantity of carbon deposition can be decreased, thus decreasing the synthesis of biochar, because the residence duration of these pyrolysis vapours in the high-temperature zone is shorter (Al-Rumaihi, et al., 2022). Since thermally unstable biomass components may be transformed into a liquid product before they form unwanted coal, quick pyrolysis yields a greater liquid product (Sharma R. et al., 2024). Product dispersion is therefore greatly influenced by heat and mass transport mechanisms, phase transition phenomena, and the kinetics of chemical reactions (Liu R. et al., 2020). The ideal pilot-scale reactors for the procedure are fluidized bed reactors because of their high heating rates, quick devolatilization, and ease of operation. Other reactors used for this purpose include entrained flow reactors, rotating cone reactors, and circulating fluidized bed reactors (Iannello et al., 2022).

2.1.3.3.3 Flash pyrolysis

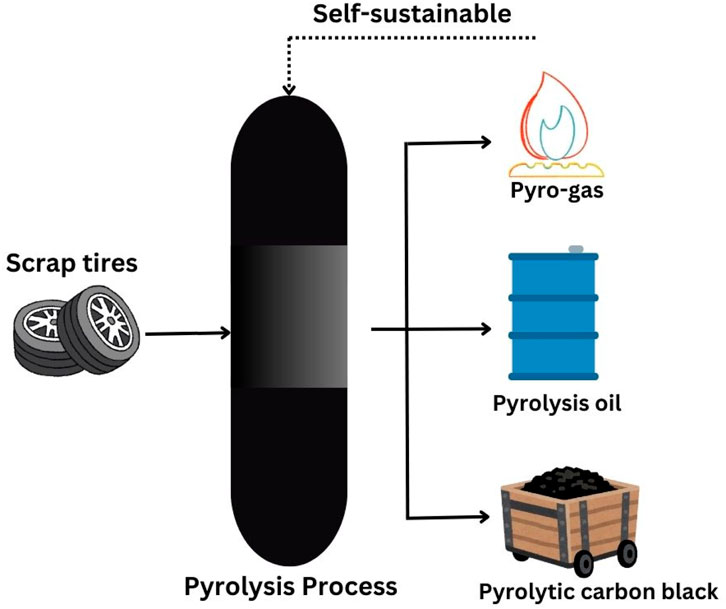

Flash pyrolysis is an improved version of fast pyrolysis in which biomass degrades fast often in less than a minute, and at temperatures above 1000 C and heating rates surpassing 1000 °C sec-1 (Amenaghawon et al., 2021). Figure 10 provides an illustration of this process in which the pyrolysis of car tire scrap is used as an example. Combining high temperature, a short vapour residence time, and a rapid heating rate results in a high bio-oil production however, it reduces biochar generation in the process (Pelagalli et al., 2024). Although flash pyrolysis is performed in twin-screw mixing reactors and fluidised bed reactors, its industrial use is restricted due to the reactor’s high operating temperatures and extremely quick heating rates (Ighalo et al., 2022).

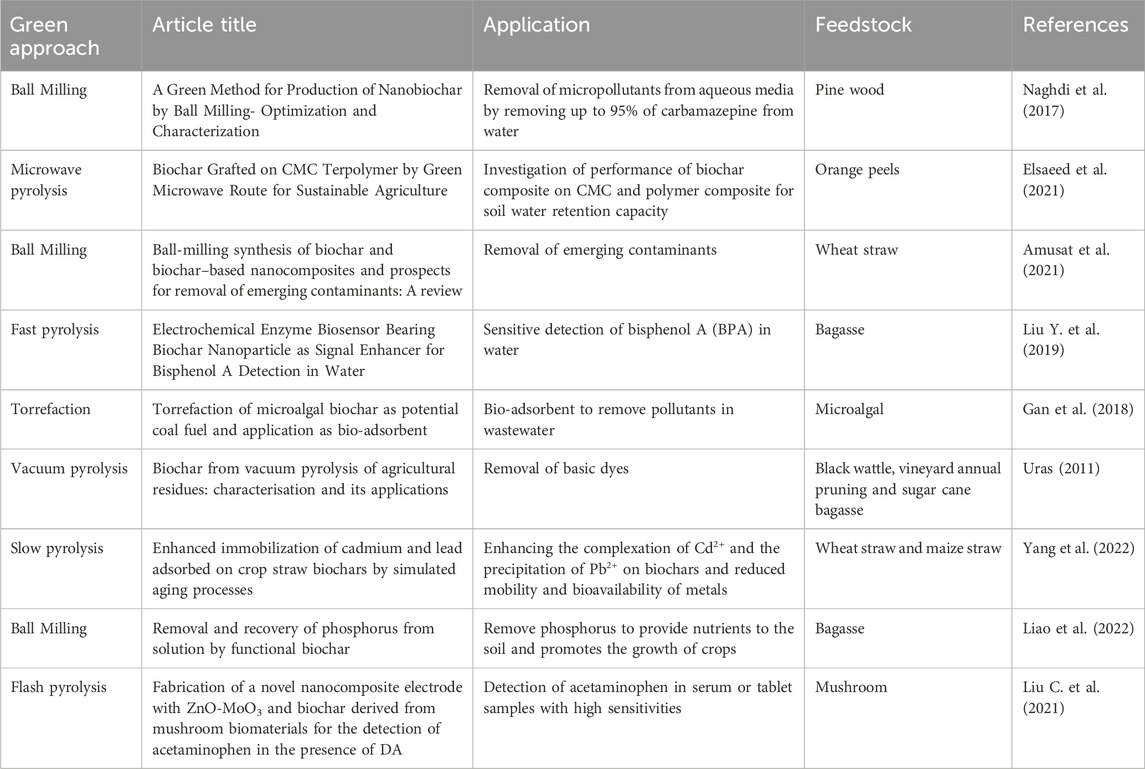

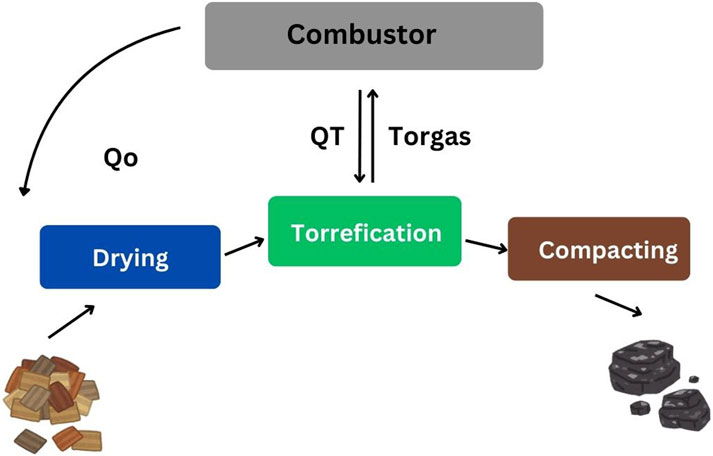

The main distinctions among the three pyrolysis techniques discussed above is an illustration of how these processes have been utilized to develop green or bio-friendly biochar for various applications as illustrated in Table 1. The fixed carbon percentage of biochar produced by slow pyrolysis ranges from 30% to 98.1% while (Chormare et al., 2023) for certain feedstocks, such as wheat straw, pine woodchip and green waste, there are notable variations in the range. This is most likely due to variations in the feedstock’s operating temperature and carbon concentration. Fast pyrolysis biochar has a fixed carbon concentration of about 44.07% and yields 12 - 15 weight percent of char, charcoal, biochar or bio-coal. Because data is scarce for flash/fast pyrolysis, the average fixed carbon content value is utilized (Kumari et al., 2024).

One measure of a biochar’s resistance is its fixed carbon content. Higher fixed carbon content biochar is more stable and resistant to microbial breakdown, which extends its lifespan (Leng et al., 2019). Biochar with a high fixed carbon content not only increases the percentage of biochar but also helps sequester carbon. A large amount of tar is produced by biomass with a high cellulose and hemicellulose content. A high concentration of lignin promotes the development of carbonization and biochar. Compared to lignocellulosic biomass, lignin-based biomass has a higher fixed carbon content ranging from 45.36% to 94.0% (Seow et al., 2022). For biochar with a high fixed carbon content, lignin-based biomass should ideally be pyrolyzed slowly. However, more research is still required to determine how temperature, heating rate, and feedstock content impact the surface area and functionality of biochar.

2.2 Modification of biochar methods

As more improved biochar with a variety of properties continue to be developed, the curiosity of the scientific communities continues to pique. This is due to its widespread usage in pollution management and its environmental and economic benefits (Ramanayaka et al., 2020; Sharma M. et al., 2024). A study by Wang and Wang (2019) further confirmed this fact as it discovered that changing the characteristics of biochar can increase its applications. The modification of biochar is the process of employing physical and chemical methods to activate the original biochar in order to get the desired outcome (Panwar and Pawar, 2020). The properties of biochar are affected by the kind of activator, soaking time, activation period, and activation temperature (Velusamy et al., 2021). Either before or after pyrolysis, or both, the biochar is altered. Post-pyrolysis, alterations are more prevalent and entail treating biochar after it has been created, whereas pre-pyrolysis changes include treating the biochar feedstock (Vijayaraghavan, 2019).

Depending on the modification method, modified biochar is separated into two categories, namely,; smart biochar and designed engineering biochar. These are referred to biochar materials that have been modified or specifically created to enhance their properties for certain applications, often targeting agricultural needs. Three stages are involved in the modification process of the biochar that is; before the final product is received, during the heating process, and during the feedstock preparation (Vijayaraghavan, 2019). Numerous modification strategies may be used to change the surface properties of biochar, such as increasing the specific pore volume, surface area and the amount of oxygen-containing functional groups. In regard to electrochemical capacity, modified biochar performs better than untreated biochar when it is saturated with mineral sorbents, treated with chemicals or gases, or magnetized (Kumar et al., 2022).

Although chemical and physical activation of biochar are typically carried out after pyrolysis, successful outcomes have been seen when chemical activation is carried out prior to pyrolysis (Chen Y. et al., 2024). In order to produce sorbents for the remediation of dirty water, the modification approach that has attracted the greatest scientific attention is the process of embedding different components into the structure of biochar, either before or after pyrolysis (Ambika et al., 2022). Enhancing the effectiveness of biochar’s ability to identify pollutants in water is the fundamental objective of all these modification techniques, which frequently include altering physical or chemical properties like surface functionality and surface area (Joshi et al., 2023).

2.2.1 Chemical modification

Innovative biochar with enhanced chemical characteristics has been utilised in various applications thus, attracting significant research interest by a growing number of scientists (Panahi et al., 2020). Examples are research studies by Rawat et al. (2023) and Nguyen et al. (2024) who provided comprehensive overviews of chemical modifications and applications of biochar, notably the use of modified biochar as favorable electrochemical materials and catalysts. Table 2 lists the chemical modification techniques for biochar, based on the chemical characteristics such as pore volume, oxygen-containing functional group contents, increasing surface area, and synergistic effects which make them suitable as sensing material (Chen J. et al., 2024).

Chemical oxidation, steam coating, CO2 activation, and impregnation with natural and manufactured nanomaterials, are some of the methods used during chemical modification of biochar (Panahi et al., 2020; Saravanan et al., 2021). In addition to improving active site availability, hydrophobicity, aromaticity, complexation, chemisorption, electrostatic attraction, and π-π interactions, chemical modifications also increase surface functional groups and cation exchange capacity Qiu., 2022).

By combining biochar with Fe, Mg, or Al for two to 12 hours when an electric current is present, the chemical treatment may change the functional groups on the pore surface, thus improving certain chemical characteristics or adsorption (Zhang et al., 2020). Modern, easy, and time-efficient techniques for making modified biochar involve an electric field (Gupta et al., 2023) in a procedure called electro-modification which gives the biochar a larger surface area while introducing chemicals into it. Strong oxidants can be produced chemically or electrochemically using aluminum electrodes in acidic pH, such as aluminum ions or hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite ions (Zoroufchi Benis, 2023). Jung et al. (2015) used an electrochemical method based on an aluminum electrode to produce electro-modified biochar utilising a dried brown marine microalga called Laminaria japonica, as the feedstock (Gabhane et al., 2020) When compared to previously documented modification methods, the best option for creating modified biochar would be electro-modification as it offers several benefits, including time savings, ease of usage, and simultaneous improvements to the biochar’s surface area and crystalline structure (Gupta et al., 2023). As such, some researchers were able to successfully observe the benefits of this method. Rathee et al. (2024) used an electrochemical technique based on aluminum electrodes to successfully create modified biochar from marine macroalgae. Two of the unique characteristics of the electro-modified biochar were its increased surface area and the presence of nano-sized crystalline boehmite on its surface. The marine macroalgae were utilised as inexpensive, secure and harmless products with free amino and hydroxyl groups with chelating and crosslinking properties (Thambiliyagodage et al., 2023). Chitosan is another interesting compound often used in electrochemical studies. The benefits of chitosan include biocompatibility, nontoxicity, antibacterial activity and adsorptive capacity which finds potential applications in biotechnology, bio (sensor) development, biomedicine and cosmetics (Azmana et al., 2021).

The aforementioned physicochemical alterations of chitosan-modified biochar are also described in terms of surface shape, electromagnetism, specific surface area, pore characteristics, and surface functional groups. The electrochemistry of chitosan-modified biochar (CMB) is still misunderstood and unexplored by researchers (Sutar et al., 2023). Various biochar modifications based on the above analyses propose that the surface area can be increased by using electro modifications which uses electric current to enhance the biochar’s surface area, this is while chitosan modifications alter the structure of biochar making it (Gęca et al., 2023) more basic and less hydrophilic (Gao et al., 2022).

Recently shrinking biochar to the nano scale to create “nanobiochar” (Figure 11) using ball milling has taken an upsurge among researchers, resulting in products with increased surface functional groups, surface-active sites, high surface areas and high porosity (Verma N. et al., 2023). The high porosity provides an interconnected network of pores, allowing for efficient ion and electron transport, making it particularly useful for applications such as energy storage (supercapacitors, batteries), catalysis and sensor development. Nanobiochar have shown to possess important applications in the detection of contaminants such as Lead (Pb), Cadmium (Cd), Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), bacterial pathogens and viruses. This has prompted an appeal for more research to be conducted due to the increased popularity seen with the modification of biochar (Joshi et al., 2023).

2.2.2 Physical modification

Physical modification is far better suited to applications in real life since it is easier to implement on a wide scale. The application of traditional biochar requires further enhancements; so, biochar has to be physically altered to acquire new surface characteristics and structures (Kumar N. et al., 2024). Materials may be reduced to the nanoscale via ball milling while maintaining their crystal structure. Mechanical grinding is performed in ball milling by triggering particles to collide and agglomerate, reducing particle size (Akhil et al., 2021; Amusat et al., 2021; Murtaza et al., 2024) to produce nanobiochar.

Nanobiochar are classified into three categories based on the nanomaterials employed to develop them, namely,; carbonaceous nanobiochar, magnetic nanobiochar composites and metal/metal oxide nanobiochar composites. Different synthesis techniques are used to create these composites, but all synthesis techniques share two treatment steps, the post-treatment and the pre-treatment of biomass (Chaubey et al., 2024; Goswami et al., 2022). Nanobiochar can be produced using both the top-down and bottom-up methods. The top-down approach shrinks the bulk material to the nanoscale, whereas the bottom-up approach builds the material up from the atomic scale (Borane et al., 2024). For instance, Chaubey et al. (2024) produced nanobiochar by using a high-speed centrifuge to grind macrobiochar which necessitates a sifting and a crushing machine (Ramanayaka et al., 2020). The nanobiochar was extracted and recovered from the supernatant after the resulting biochar colloids had been suspended in water. Additionally, in another study, researchers broke down biochar on a smaller scale using a disc mill rather than a ball mill (Shafiq et al., 2023).

Another method for producing nanobiochar is double-disc milling, however due to its large operating expenses, its application is less widespread. Because of attrition and shear stress, ball milling generates more nanobiochar with superior size and shape homogeneity than the widely used double disc mill technique (Saraugi and Routray, 2024). Additionally, nanobiochar may also be directly produced by flash heating graphitic nanosheets. In flash heating process biochar is usually physically dispersed using an ultrasonic vibrator, and then sonicated to generate nanosize particles (Chausali et al., 2021). Kumar P. et al. (2024) demonstrated an additional approach for generating nanobiochar in which bulk biochar was produced using bovine dung and soybean straw as feedstock. It was then digested in a high-pressure hydrothermal reactor with intense nitric acid and sulfuric acid to produce nanobiochar.

Nanobiochar performs better than bulk biochar in terms of physicochemical characteristics, since they have a large and stable specific surface area, a unique nanostructure and strong catalytic activities (Tiwari et al., 2022). In a study by Ganguly and Das (2024) ethanol was used to suspend powdered biochar. The mixture was then dried out and then centrifugation was used to recover the nanofraction. In a similar procedure nanobiochar where produced using peanut shell waste in a study by Mathabatha et al. (2023). They were fully defined by a number of important properties such as high porosity with superior superficial functional groups.

Size screening is another method for creating nanobiochar which entailed centrifuging biochar suspensions generated with double-distilled water and spinning them for 3 minutes at 5000 rpm. After passing through a 200 nm filter membrane, the supernatant containing nanobiochar is then oven dried (Udomkun et al., 2024). In another study conducted under nitrogen protection conducted by Kwikima et al. (2023), pyrolyzed sugarcane waste was ground to create biochar which was then pulverized for 4 hours. Even though numerous research studies have demonstrated various nanobiochar fabrication procedures, ball milling is the only physical modification method which has potential for high-value applications in emerging research fields including biocatalysis and electrochemical bio (sensing) (Song et al., 2022). Compared to pure biochar with low electrical conductivity and subpar catalytic performance, ball-milled nanobiochar has demonstrated significant electrochemical qualities such as carbon electrode materials for energy applications (Lyu et al., 2019). Recent studies have shown that a graphitic structure, with plenty of pores, a high interior surface area, and many oxygen-containing functional groups all assist to transport electrons, which lowers interface resistance (Verma and Singh, 2023). Its promise for further study and as a sensing material as shown by the fact that high temperature nanobiochar demonstrate the greatest electrocatalytic performance while costing hundreds of thousands less than platinum electrodes (Ferlazzo et al., 2023).

Before proceeding with retargeted real-world implementations, a thorough understanding of current nanobiochar research is necessary, including preparation, unique properties, and targeted applications. Table 2 provides a list of various biochar chemical modification methods along with specified applications.

3 Nanobiochar based composites and their synthesis

Nanobiochar based composites are made by impregnating nanobiochar with metal oxides, metal nanoparticles or carbonaceous materials to change the surface properties of the nanobiochar. Often used nanomaterials include the following; graphene oxide nanomaterials, graphene sheets, carbon nanotubes, chitosan, ZnS nanocrystals, graphitic C3N4, and quantum dots (Rajput and Minkina, 2024). During composite development, the nanobiochar mainly acts as a scaffold with a large surface area for the substance being deposited. Composites differ from chemical activation in that they create completely new functional groups on surfaces that were not previously present on the surface of the feedstock or charcoal (Xia et al., 2023).

Composites are often materials made up of many nanoscale components contained in a matrix of ceramic, metal, or polymer (Omanović-Mikličanin et al., 2020). Creating synergistic effects between different materials, including electrical compatibility, conductivity or catalytic activity are their main objectives (Mourdikoudis et al., 2021). Additionally, other physical and chemical techniques have been created for the fabrication of composites, including sonochemical and laser ablation, microwave irradiation, thermal decomposition, and electrochemical methods however, these methods have similar drawbacks, including high energy requirements, the use of toxic chemicals, and high operational costs (Theerthagiri et al., 2022).

Because of these constraints, there has been great interest in using green synthesis to develop composites (Gupta et al., 2023). The literature claims that green procedures involving capping agents and reducing agents such as enzymes, plant extracts, natural polymers, microbes, and sugars, have been employed as novel substitutes during composite synthesis (Ahmed et al., 2022). The use of more stable materials, one-step procedures, economic effectiveness, environmental friendliness, and energy efficiency are the main advantages of employing green technologies (Mahmood et al., 2024). For example, Salazar et al. (2019) used tea extract to reduce both Ag+ cations and graphene oxide sheets in a single green process to produce a reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite (rGox/AgNPs) enhanced by silver nanoparticles for H2O2 sensing applications. On the other hand, Jebril et al. (2021) proposed a green electrochemical bisphenol A (BPA) sensor based on a sonogel-carbon electrode modified with gold sononanoparticles (AuSNPs) and carbon black (CB).

3.1 Metal/metal oxides nanobiochar composites

Nanobiochar metal/metal oxide composites are primarily produced through three steps, namely,; the bioaccumulation for target element fortification, salt pre-treatment of biomass and after pyrolysis, the nanometal oxides are inserted (Moulick et al., 2025). The first and second steps rely on metal impregnation of the biomass prior to pyrolysis while the third step introduces metal/metal oxide nanometal directly into the pyrolyzed nanobiochar (Mishra R. et al., 2023).

Metal-based oxides, quantum dots, and nanoparticles (such as nanogold, nanosilver, etc.) are common names for metal materials (Nasr-Esfahani and Ensafi, 2022). Because of their distinct surface crystal planes, high surface atom density, and surface relaxation between layers, metal oxide and metal nanoparticles have been reported for exhibiting unique reactivities and enhanced chemical activities (Leybo et al., 2024). Since the development of green chemical methods for the synthesis of metal materials s in recent years, most researchers are now interested in learning more about the potential mechanisms of metal material formation as well as the mechanisms of bio-reduction and metal ion application (Huston et al., 2021). Thus, green chemistry has been researched to find a method of manufacturing well-characterized metal materials which are less harmful to humans and the environment. Using living organisms to develop metal nanomaterial is one of the most sophisticated methods as they seem to be the most suitable media (Iravani, 2011). Compared to prokaryotic bacterial cells and eukaryotic fungus, plants create nanomaterials/nanoparticles faster and in a wider range of sizes and shapes (Bahrulolum et al., 2021) are more stable and with low toxicity. Examples where plants have been utilized include a study by Ivanišević (2023) where silver nanoparticles were synthesized with an aqueous extract of Salvia leriifolia as a reducing and stabilizing agent. The nanoparticles were utilised for antibacterial activity testing and as catalysts in the electrochemical detection of nitrite. Patel et al. (2023) synthesized silver (AgNPs), gold (AuNPs), and gold-silver bimetallic (Au-AgNPs) nanoparticles from medicinal plants including Syzygium cumini, Plumbago zeylanica, and Barleria prionitis. The nanoparticles were then tested against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis in an effort to eradicate the bacteria. By creating AgNPs using Achyranthes aspera L. extracts and shielding them with chitosan, Ton-That et al. (2025) proposed that they might be utilized in sensor development to extract and identify thiocyanate ions from contaminated water.

Yasin et al. (2024) found that coupling nanobiochar with metal-based nanomaterial enhanced surface interaction and constructed stable nanocomposites. Zhang et al. (2024) discovered that coating the surface of nanobiochar with functional nanoparticles improved its broad spectrum of pollutant detection capabilities. Additionally, in a similar study, nanobiochar was employed in the development of dissolved organic carbon with different molecular weights, carboxyl contents, and aromaticity (Udomkun et al., 2024). Conversely, nanobiochar can destabilize nanomaterials by promoting attractive surface contacts by lowering the pH of solutions. Furthermore, a study by Walcarius (2017) discovered that charge transfer between the π*continuum of glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) and the conduction bands of metal-based nanomaterials, drive the attractive surface contacts. An adjacent packing of nanoparticles on the outer walls of GCE was the outcome of this electron density transfer from the nanoparticles to the surfaces of GCE (Ramachandran et al., 2024). The transmission of charge between GCE’s polyaromatic surfaces, nanobiochar and nanoparticles in aqueous media then exhibits some desirable characteristics for the development of electrochemical sensors, including high surface area and high electrochemical catalytic properties that increase the sensitivity of detection (Cancelliere et al., 2022).

3.2 Nanostructured biochar composites for sensing applications

Recently, a number of techniques for creating carbon-based nanomaterials with enhanced performance for a range of uses have been established (Uskoković, 2021). It is believed that these nanomaterials are appropriate and are promising in reducing various hazardous substances (Torrinha et al., 2020). These materials' exceptional qualities, as well as their potential for eco-friendly synthesis techniques and industrial production of carbon nanostructured materials, make them undeniably essential. As such, they have drawn the attention of numerous scientific and technological researchers in recent years (Choudhary et al., 2024). The majority of carbonaceous-based composites are now made by chemical processes, but in order to evaluate the effects of these nanomaterials, nanotechnology has begun to focus on the materials directly produced by green synthesis approaches (Mamidi et al., 2022). This is based on the incredible success that these smart nanomaterials have since their objectives present a wide range of research opportunities that can improve synthetic control at lower temperatures and increase economic and environmental efficiencies. (Choudhary et al., 2024).

The recent use of a few carbon-based nanomaterials, such as reduced graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, graphene and carbon nanotube composites have been used to construct electrochemical sensors (Wu et al., 2022). The reported studies illustrated that using carbon materials as platforms for the construction of electrochemical devices is feasible (Elbehiry et al., 2022; Raju et al., 2023; Cetinkaya et al., 2024). These materials have large surface areas (typically in the range of 200–2,700 m2/g) and rapid electron transfer properties. Nonetheless, given the disposable nature of carbon-based sensing devices, developing very cost-effective and repeatable sensors is critical. By modifying the pyrolysis conditions during preparation, carbonaceous nanobiochar composites have recently shown to have high electrochemical characteristics and the potential to be employed in electrode manufacture. Thus, would be beneficial and pertinent to conduct studies on the potential use of biochar in the production of advanced electrochemical sensors, considering the cheap cost and simplicity of synthesis of nanobiochar (Xia et al., 2023).

3.3 Magnetic nanobiochar composites

Given their special properties, such as superparamagnetic behaviour, resulting from the effect of thermal energy, magnetic nanomaterials have drawn the interest of scholars in the last few decades (Rubel and Hossain, 2022). When functionalized with analyte-specific proteins and when exposed to an external magnetic field, magnetic nanoparticles can respond enabling the magnetic separation of analytes for subsequent detection (Kakkar et al., 2024). The final use of nanoparticles determines their particle magnetism which is based on their size and chemical makeup. Metallic iron, cobalt, iron oxides, nickel, and other multielement compounds are among the materials used to make magnetic particles (Nisticò, 2021). Particularly interesting are iron-based nanoparticles (e.g., FeO, Fe3O4, -Fe2O3) due to their apparent biocompatibility and cheaper manufacturing cost. The three main types of magnetic signal detection techniques are T2 relaxation nuclear magnetic resonance, magnetoresistance, and hydrodynamic property studies (Kumar N. et al., 2024; Rezaei et al., 2024).

In order to improve parameters like specific surface area, catalytic degradation capacity, pore-size distribution, active site availability, pore volume, ease of separation along with high efficiency in detection and removal; magnetic materialshave recently been combined with nanobiochar to create magnetic-based composite materials; a new class of multifunctional materials (Sher et al., 2024). Consequently, magnetic nanobiochar composites offer a broad range of environmental applications and the ability to remediate a variety of waste materials (Chausali et al., 2021). There are two methods for creating magnetic nanobiochar composites; co-precipitating iron oxides (chemically) onto biochar or pre-treating biomass with iron ions (Xia et al., 2023). To assure magnetism induction and the availability of active sites for iron oxide for pollution removal, these approaches might cover the surface of the biochar with nanosized magnetic iron oxide, such as Fe3O4, CoFe2O4 and c-Fe2O3. The magnetic feature of biochar makes it easier to separate it from solutions and enhance its ability to sense (Nisticò, 2021).

Some researchers such as Jenie et al. (2020) synthesized and characterized magnetic nanobiochar by pyrolyzing and carbonizing oil palm empty fruit bunches. Magnetic nanobiochar samples with excellent physical, chemical and magnetic properties were created at 500 °C, which is the ideal carbonization temperature. Additionally, Elbasiouny et al. (2023) created a magnetic nanobiochar composite that has outstanding magnetic separation capabilities as it was loaded with nano γ-Fe2O3 particles. The magnetic nanobiochar composite was used to detect bisphenol A in simulated wastewater, and the results illustrated that the isotherms and detecting kinetics agreed with the Langmuir model and the pseudo-second-order kinetics model, respectively. As much as this is a novel topic, a few researchers are slowly growing this field particularly the use of magnetic nanobiochar composites in sensor development for the detection of human and environmentally harmful substances.

3.4 Development of nanobiochar based composites sensors

Biochar has shown promise in electrochemical applications, particularly in energy storage and conversion devices such as supercapacitors and fuel cells (Ahuja et al., 2024). The material’s high conductivity, coupled with its tunable porosity, makes it an excellent alternative to traditional carbon-based electrode materials (Zhang L. et al., 2021). Recent studies have demonstrated the modification of biochar with metal nanoparticles or conductive polymers to enhance its electrochemical properties, thereby improving charge transfer efficiency and stability in electrochemical systems (Liu H. et al., 2023). Researchers have attempted to develop novel methods to foster non-toxic nanobiochar based composites as sensing platform in electrochemical devices (Feliz Florian et al., 2024). They have created various sensors that find extensive use in a variety of studies due to their benefit of speed, sensitivity and selectivity in multiple analyte detection (Li Y. et al., 2022). Additionally, researchers have also focused on developing nanostructured nanobiochar electrodes with exciting morphological and electrochemical properties such as electrical conductivity, surface rugosity and reactive functional groups (Saraugi and Routray, 2024). The properties of biochar enable competitive analytical performance and adaptability in the manufacturing, customization, and analytical applications of nanobiochar-based sensors (Bressi, 2023).

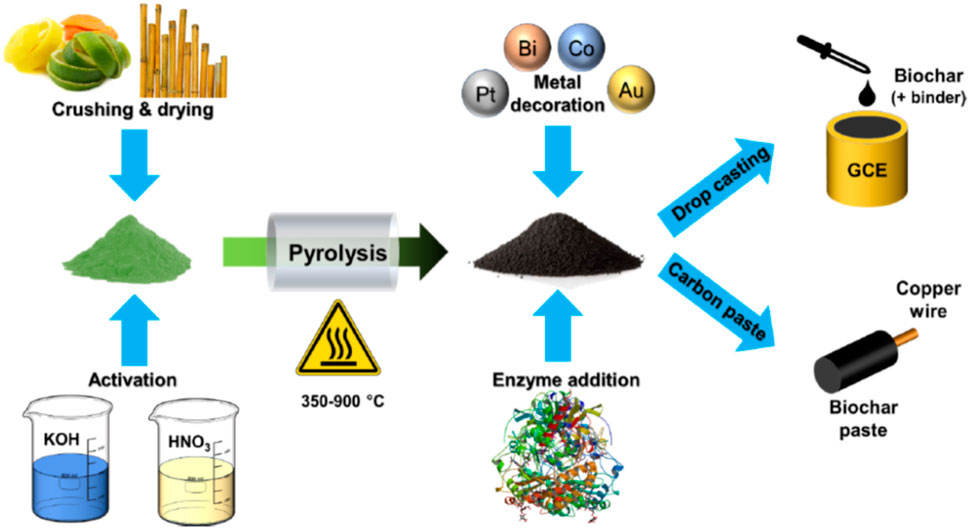

Electrochemical platforms developed from nanobiochar are often created through a straightforward process one of which involves pre-treating fresh biomass pyrolysis with activating species, thus modifying the surface of the biochar with catalytic species (e.g., enzymes or metal oxides), and then immobilizing biochar on the conductive surface (Figure 12) (Kumar et al., 2023).

Figure 12. Diagram showing the main procedures for creating nanobiochar electrodes. Reprinted from Elsevier with copyright permission (2020) (Spanu et al., 2020).

As an added benefit, the high specific surface area and the porous structure of nanobiochar make it a perfect platform for loading nanoscale catalysts (Khare, 2021). Therefore, it is common to see tailoring with nanomaterials like metals, metal oxide nanoparticles, or enzymes as the final step prior to electrode construction (Bhandari et al., 2023). In order to produce selective biosensors, Mota et al. (2023) found that metal/metal oxide combined with nanobiochar may be readily changed using enzymes. In this instance, a biocatalytic effect is responsible for the coupling agent’s increased sensitivity and selectivity; the bioreceptor (enzyme) identifies the analyte and catalyses a process that leads to analyte consumption. Using ball milling biochar with ion-imprinted polymer cavities possessing rich oxygenic functional groups and excellent conductivity, Mao et al. (2022) created a new electrochemical sensor. Nanosized ball milling biochar was produced via rigorous ball milling and high temperature pyrolysis. The synergistic effect of rigorous ball milling followed by high-temperature pyrolysis resulted in a nanobiochar with superior electrochemical properties, adsorption capacity, and structural stability.

On the other hand, He et al. (2020) developed a sensitive and reusable electrochemical biosensor for bisphenol A detection by immobilizing tyrosinase (TYR) enzymes on highly conductive magnetic nanobiochar nanoparticles with carboxyl active platforms. The newly created nano-sized biochar nanoparticles from biomass demonstrated remarkable electrochemical activity after functionalization with carboxylic functional groups and magnetic nanoparticles. These nanoparticles were then used for multi-layered TYR immobilization using covalent attachment, cross-linking, and precipitation techniques. The bisphenol A detecting device was readily created by magnetically connecting the biocatalyst of multi-layered TYR with carboxylic functional groups and magnetic nanoparticles to a glassy carbon electrode. The sensor’s exceptional qualities, such as its high conductivity, stability and biocatalytic activity greatly improved the bisphenol A detection signal. This study clearly demonstrated the support presented by the presence of nanobiochar.

In another study, Bhattacharya et al. (2024) created a portable, inexpensive, and sensitive paper-type nanobiochar electrochemical immunosensor which was used to detect microcystin-LR (MCLR) toxins in water. To produce the paper immunosensor, the highly conductive and dispersible nanobiochar particle (nBC) and anti-MCLR antibody were dipped and dried on filter paper. The nBC-paper immunosensor used amperometry to precisely measure the presence of MCLR. The immunosensor was used to detect ambient water with good recovery after the investigation successfully established its high selectivity, repeatability, and storage durability. The successful development of a broadly accessible and reasonably priced paper electrochemical immunosensing system based on nanobiochar has significant implications for the creation of extremely economical electrochemical devices. Thus, the incorporation of biochar in electrochemical systems and biosensor technologies represents a rapidly evolving field with numerous real-world applications. From energy storage to medical diagnostics and environmental monitoring, biochar’s unique physicochemical properties are being leveraged to create innovative, cost-effective, and sustainable solutions for global challenges. Emerging trends include the advancements in biochar modification strategies, including doping with heteroatoms (e.g., nitrogen, sulfur) and hybridization with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes), are expected to further expand its applicability in electrochemical systems and biosensing technologies (Xu et al., 2024). Additionally, the development of biodegradable and sustainable biochar-based sensors aligns with the growing emphasis on green chemistry and circular economy principles.

4 Application of nanobiochar based composites sensors

The concentration ranges established by regulations and guidelines for toxicity reasons makes determining water contaminants a challenging topic for analytical chemists (Sohrabi et al., 2021). To satisfy these objectives, a variety of analytical techniques are available. To find contaminants in water samples, it is advised to use photometric techniques, atomic absorption spectroscope, flame or graphite furnace inductively coupled plasma emission or mass spectrometry, total reflection X-Ray fluorimetry and anodic stripping voltammetry (Salunke and Shirale, 2021; Canciu et al., 2021). Although these techniques offer broad linear ranges and strong detection limits, they require the use of costly analytical equipment in laboratories (GadelHak et al., 2023). A sample’s pre-treatment, transportation and collection all need time and might lead to mistakes. Therefore, it is imperative to develop point of analysis technologies in order to overcome and remedy the increasing human and environmental harmful pollutants in our societies.

Thus, the performance of several sensor stations working together may identify the presence of colchicines, aldicarb, nicotine and glyphosate in water samples, according to a study of cutting-edge monitoring technologies done by Zulkifli et al. (2018). Lambrou et al. (2014) also created a different, less expensive sensor network that uses a large number of electrochemical optical sensors to detect Escherichia coli (E. coli) and arsenic in a real-time distribution system. In its design, the system included six different types of water quality parameter sensors which could detect temperature, turbidity, conductivity, pH, and water flow simultaneously while low concentration hazardous chemicals polluted the water distribution system.

This development of sensors has divided researchers due to the use of several methodologies used in measuring water quality. This is due to the fact that it was discovered that contaminants could theoretically be present at any point along the water distribution system (Batina and Krtalić, 2024). To determine water quality, researchers decided to employ as many sensors as a possible placement strategy rather than a single sensor. However, the method for sensor placement detecting water contaminants is relatively complicated, so the platform used to build a sensor must be carefully considered (López-Ramírez and Aragón-Zavala, 2023). Even though sensor placement is one of the most researched topics, acquiring a “perfect sensor” that produces an instantaneous reaction when any concentration of pollutants reaches it, is regarded as unclear and near impossible thus, scientists face a difficult path ahead of them (Kishore et al., 2024). Additionally, sensors empowered by nanomaterials are currently created for sensing applications that need flexibility, multiplex functionality and high efficiency (Yao et al., 2020). Numerous nanosensors possess the inherent capacity to accomplish these goals; yet they need to be further refined into instruments that are easy to use and operate, and able to identify analytes in previously unreachable locations (Singh N. et al., 2024). Al Harby’s research also discusses the unrealized potential for widespread and possibly low-cost use of nanotechnology-enabled sensors to detect chemicals, microorganisms, and other analytes in drinking water (Al Harby et al., 2022).

Point-of-use (POU) water delivery systems are therefore strongly advised due to their economical and energy-efficient techniques of storing, treating, and monitoring water quality. The spectrum of new pathogens and pollutants, especially those found in trace amounts, has proven difficult for current POU systems to handle (Raghavendra, 2024). In order to detect and remove pollutants and provide clean water on demand, flexible POU systems are needed, since contaminant species and concentrations vary from one location to another (Abioye et al., 2024). Because of their high activity and selectivity for chemical substrates, biosensors are one of the technologies that might be employed to develop sensitive and rapid water purification processes (Chadha et al., 2022). The employment of nano-supported enzymes in sophisticated POU systems is now possible because of the development of several biosensors that enhance the stability and activity of sensor materials while also increasing their utility (Pour et al., 2023). Different kinds of electrochemical biosensors have recently been identified in literature based on the experimental approach utilized to identify contaminations. For example, Sá et al. (2020) used disposable flexible screen-printed electrodes to create a simple and affordable electrochemical sensor for identifying BPA, catechol, and hydroquinone in water samples. When combined with electroanalytical performance, carbon surface properties showed enhanced conductivity and sensitivity.

Sciuto et al. (2021) suggested a novel portable biosensor for measuring the concentrations of trivalent arsenic (As (III)) and bivalent mercury (Hg (II)) in water. The technology employs two sophisticated sensing modules; a full cell based on modified metal nanomaterials for the detection of E. coli and an electrochemically miniaturized silicon device with three microelectrodes with a portable reading mechanism. Gao et al. (2016) effectively developed a p-benzoquinone driven whole-cell electrochemical biosensor for multi-pollutant toxicological investigation by co-immobilizing Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis, Gram-negative E. coli, and fungus Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Phenol (3,5-dichlorophenol), insecticides (Ametryn, Acephate), and heavy metal ions (Cu2+, Cd2+) were found both alone and in combination. Consequently, the results demonstrated that a whole-cell electrochemical biosensor based on a mixed microbial consortium was most likely to reflect the joint biotoxicity of numerous contaminants observed in actual wastewater, and that ecological risk assessment must consider the combined effects of toxicants. The above examples are a clear indication that there is great need to utilise nanobiochar in the development of water detection bio (sensors) to create more eco-friendly devices. Recent studies have explored the integration of biochar with nanomaterials and electrochemical sensors to enhance bacterial detection sensitivity. Functionalized biochar, modified with metal nanoparticles or conductive polymers, has been used to capture and identify pathogenic bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella (Zhang P. et al., 2021). The ability of biochar to adsorb bacterial cells facilitates the detection process by improving signal response in biosensors (Liu C. et al., 2020). Moreover, biochar-based platforms have been investigated for their role in water quality monitoring. The immobilization of biochar in microfluidic devices and biosensors allows for real-time detection of bacterial contamination in drinking water and wastewater (Wang et al., 2022). The sustainability and cost-effectiveness of biochar further enhance its potential as an alternative to conventional bacterial detection techniques. Bacteria such as E.coli, Mycobacterium avium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, monocytogenes and viruses such as Norovirus, Hepatitis A and several other parasites in drinking water can result in severe water-borne diseases ranging from diarrhea to cancer (Ramírez-Castillo et al., 2015). Although there are other bacteria responsible for water poisoning, recently E. coli has shown to be severe with strains capable of causing urinary tract infections, stomach cramps, anaemia, and even damage to the intestinal lining (Peng et al., 2024). The presence of E. coli in water has been shown by researchers to be an indicator of sewage or animal waste pollution containing numerous pathogenic organisms (Nawab et al., 2022).

Water quality testing based on the detection of E. coli, is still considered to be the most significant indicator of faecal contamination. When the viable cell counts of E. coli vary between 10 and 100 CFU (colony forming units, or viable cells) per millilitre, the water is deemed to be of intermediate risk by the World Health Organization (WHO). When there are 100–1000 E. coli cells per millilitre, the water is considered unsafe for human consumption (World Health Organization, 2006). The South African National Standards (SANS) for drinking water state that if no live E. coli cells are detected, the water is safe (SABS, 2011). According to SANS, the most popular techniques for evaluating the microbiological quality of water in South Africa are membrane filtration and colony counts. Similarly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using species-specific DNA primers and immunoassays (ELISA) are the most widely used techniques for verifying E. coli (Maas et al., 2017). The Technical Research Centre (TRC) of Finland acknowledged the need for decentralized water supply monitoring and control in 2006 and encouraged further research into the development and application of wireless, biosensors, nanosensors and microbiological sensors for monitoring water quality (Mieta, 2017). Many analytes, such as unculturable microbes, small-to-highly soluble organics and antibiotic resistance genes are challenging to detect with present techniques. Thus, nanobiochar handheld devices are essential in creating extremely precise sensors that can identify bacterial contamination in a matter of seconds and track the intensity rise in real time (Mosaka et al., 2023).

The same amount of attention is also required with regards to heavy metals. The heavy metals most closely linked to adverse human health outcomes include mercury (Hg) arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb) (Balali-Mood et al., 2021). Heavy metals are widely used in high-tech applications as well as in electronics, machinery and common place items due to their diverse chemical characteristics (Gautam et al., 2014). As a result, they can enter human and animal food chains via several anthropogenic causes as well as natural geochemical weathering of rocks and soil. Mining wastes, municipal wastewater, landfill leaches, industrial wastewaters and urban runoff, particularly from the electronic, electroplating and metal-finishing industries are also causes of contamination (Verma R. et al., 2023). With the increased generation of metals from technological operations, waste management has become a critical issue (Dutta et al., 2023). Heavy metal contamination in water and soil is a critical environmental issue due to their toxicity and persistence in ecosystem destruction. The detection of heavy metals is achieved using conventional detection methods, such as atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) are highly sensitive but often expensive, time-consuming and require skilled operators (Liu J. et al., 2023). Biochar-based sensors have emerged as cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternatives for detecting heavy metals, offering high adsorption capacity, surface functionalization, and integration with electrochemical and optical detection techniques (Wang et al., 2024).

Electrochemical sensors utilising biochar composites have demonstrated rapid and sensitive detection of metals such as lead (Pb2+), mercury (Hg2+), and cadmium (Cd2+). Modified biochar electrodes enhance electron transfer and facilitate real-time monitoring of heavy metal concentrations. For instance, studies have shown that biochar-carbon nanotube (BC-CNT) composite electrodes significantly improve detection limits for Pb2+ and Cd2+ achieving levels as low as parts per billion (ppb) (Yang G. et al., 2021). Recent advancements have also focused on optical and fluorescence-based sensors. Functionalized biochar doped with quantum dots or metal nanoparticles has been employed for colorimetric and fluorometric detection of heavy metals. A study by Li Y. et al. (2022) demonstrated a biochar-based sensor incorporating gold nanoparticles, which exhibited a color change in the presence of Hg2+ enabling a visual detection without sophisticated instruments. Biochar-based sensors have been successfully applied in field monitoring of heavy metal contamination in drinking water, industrial effluents and agricultural soils. Their low-cost production, high stability and eco-friendly nature make them suitable for large-scale deployment in resource-limited areas. Additionally, the integration of biochar sensors with portable and smartphone-based devices has enhanced real-time data collection and analysis for on-site monitoring (Zhang and Dai, 2022). Based on toxicity information and scientific research, the WHO and the South African Water Quality Directive have both suggested standards and recommendations for heavy metals in drinking water. Screening for these heavy metals in drinking water and at the source of wastewater a is essential due to their severe toxicity (Sable et al., 2024; Elkhatat et al., 2021). To effectively enforce rules, identifying and stopping the harmful impact of these pollutants on the environment and human health, more portable and affordable analytical testing tools such as nanobiochar bio (sensors) are required (Koel and Kaljurand, 2019).

5 Critical research gaps in biochar-based sensing technologies