- 1Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine at Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

- 2Office of Academic and Student Affairs, College of Veterinary Medicine at Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

Introduction: As an assignment in an introductory course to the profession, we asked first year veterinary students in their initial (fall) semester to identify words that they would use to describe themselves now and how they want to be described in the future as veterinarians.

Methods: Using a Qualtrics survey instrument, students were asked to record five descriptive words in response to each of the following prompts: “How would you describe yourself?”, “How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?”, and “How would you like your future clients to describe you?” Students’ responses were collected beginning in fall of 2017 (Class of 2021) through fall of 2024 (Class of 2028). Word choices were collated and ranked based on the number of times an individual word was recorded.

Results: While there was some variability from year to year, the five most common word choices for the prompt “How would you describe yourself?” were: “Hard-working”, “Kind”, “Caring”, “Compassionate”, and “Determined”. The five most common word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?” were: “Hard-working”, “Compassionate”, “Knowledgeable”, “Caring”, and “Reliable”. The five most common word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?” were: “Compassionate,” “Knowledgeable”, “Caring”, “Kind”, and “Empathetic”. The recorded rank for the most common descriptive word changed slightly over the study time to the prompts “how would you describe yourself” and the “how would you want your colleagues to describe you”, but not the “how would you want your clients to describe you” prompt.

Discussion: These collective student responses provide insight into the origin of their veterinary “identity” as they enter the veterinary curriculum to become veterinarian professionals.

Introduction

How veterinary students become practicing veterinary professionals is a multifaceted, dynamic, and complex process involving the development of both technical and non-technical skills. In many ways, however, the process remains enigmatic. In addition to the classic skill development process, there is a transition in thinking about the profession and how one identifies within the profession. A component of this development is the formation of a professional “self,” “brand,” or a professional “identity” (2, 4, 17, 44, 48, 49, 62). As a professional “identity” does not always have one standard definition; this concept is often articulated in broad constructs based on what professionals do (actions and behaviors); the possession of certain knowledge and skills; a set of values, beliefs, and ethics; a social identity; and a group identity (17). A professional identity has elements of a professional “self-concept” and is a process of identification of “self” within the profession. A professional identity is formed as an individual internalizes the characteristics, norms, and values of the profession (12). This involves a process of students defining who they are in the profession and occurs in established communities such as universities and hospitals (19). This sense of belonging as a professional can lead to important outcomes such as job satisfaction, improved patient safety, decreased stress, and improved retention and recruitment of practitioners (11, 48, 63, 66). In the educational setting, developing a professional identity may result in students trying harder, increasing student success, and increased student retention (11, 63, 66). A professional identity can be formed through numerous explicit and implicit experiences. Therefore, every experience a veterinary student has with a veterinarian or the veterinary profession influences this identity. Developing professionals evolve their professional identity through education and experiences, which influence who they become as veterinary professionals. This includes important aspects of the actions, behaviors, and communication dynamics between themselves and others, such as colleagues and clients.

How one aspires to be described as a professional may serve as a motivation for individual skill development and influence future employability (1, 7, 22, 26, 39) and may also influence similar aligned constructs, such as professional and personal “branding” (5, 20). Unique words one chooses to describe themselves concurrently provide others an opportunity to gather insight about the individual’s thought process, self-awareness, self-concept, and aspirational personal goals (15, 21, 24, 27, 34, 43, 64).

In this study, we examined a stage in the development of the veterinary professional “identity” at the early formal educational process by engaging first-year veterinary students to describe themselves now and how they envision themselves being described as future veterinarians. We provided this educational opportunity to support developing their views on their professional “identity.” Our goal in codifying this information was to improve our understanding of how students at the beginning of their veterinary training view themselves prior to subsequent influences provided in the curriculum and allied veterinary career experiences.

To gain insight into our students related to their professional “identity,” we asked first-year veterinary students to provide self-descriptive word choices for themselves today and as a future veterinarian. We asked first-semester veterinary students to choose single words to describe themselves now and how they would like to be described as future veterinarians from both a colleague’s and a client’s perspective. For the assignment, veterinary students were asked to record five single descriptive word choices based on three prompts:

“How would you describe yourself?”

“How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?”

“How would you like your future clients to describe you?”

We were most interested in empirically determining (1) the unique word choices students use to describe themselves personally at the beginning of their veterinary education, (2) how they envision being described professionally in the future, and (3) if the most common descriptors were preserved or evolved over the study time. The hypothesis for comparison is that the most common student word choices would not change over the study time, even as new generations of students enter the veterinary curriculum.

Materials and methods

This study was submitted for the Iowa State University Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB 23–381) review and deemed exempt. In collecting this data, first-year veterinary students at Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine were asked to record five descriptive words to three posed questions. For each cohort (year), student responses were collected during the fall of their first year during the month of September, which was approximately, depending on the year, the third to fourth week of their veterinary curriculum. As such, the year presented in analyses refers to the respective cohort’s initial year in the veterinary curriculum and the year that the data was obtained. The data were collected as a course assignment during a core introductory course to the veterinary career. This course is colloquially entitled “Careers and Career Success,” in which students are introduced to various aspects of veterinary career options and are provided self-reflective assignments relative to aspects of the veterinary profession and their future success therein. Pilot data were collected from first-year students entering the curriculum in 2016 to refine the final study questions and determine compliance in completing the assignment.

Prior to presenting the questions posed, we provided no explicit word choice examples so that students had individual intellectual freedom to choose descriptive words in an unbiased manner. Questions were open-ended, allowing for unstructured “stream of consciousness” or “natural” answers relative to the word choices recorded. Words were recorded into a text entry box format. The students were instructed that there was no “right/wrong or correct/incorrect” answer to the questions posed to allow for spontaneous responses. Class credit for the assignment was earned by completion of the assignment only and not based on the content of the answer. Students were provided seven calendar days once the assignment was available to complete the assignment.

For the assignment, students were provided with a Qualtrics1 survey instrument and asked to record five single descriptive words in a text entry box for each of the following prompts:

Question 1. “How would you describe yourself?”

Question 2. “How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?”

Question 3. “How would you like your future clients to describe you?”

The questions were asked sequentially in the order shown here. The students were asked these same three questions in the same format annually from the fall of 2017 through the fall of 2024.

Analysis

Considering the subjective nature of the responses and that these data were from a unique single US institution, we employed descriptive statistical methodologies for this evaluation. These encompassed quantitative measures, such as counts, averages, and percentages. We did not match individually identifiable information with the responses, except that the student’s name was recorded with the assignment to provide them with credit for completion of the assignment. For this analysis, the student’s name was subsequently removed from the data set prior to collective aggregation. For each year and each of the questions, all descriptive words were grouped together into one cohort data set, as we did not ask the students to rank or prioritize the relative rank of any individual descriptor compared with the others. From each grouped dataset, we sub-grouped the same word or word stem together and then counted the absolute number of instances that an individual word was recorded by the student cohort/year. When the equivalent noun was used instead of the adjective (i.e., “compassion” vs. “compassionate”), we converted the noun form to the adjective form for counting. The sum of the unique individual words recorded was divided by the number of students who completed the assignment to determine the percentage of the total students who recorded that individual unique word per year as one of their five descriptors. Finally, the 10 most common word choices (based on the number of occurrences of a unique individual word in the complete dataset) were ranked for each cohort year from the most frequently recorded to the least frequently recorded ones.

Results

As this was a required class assignment, there was no dropout rate, as all students in each class completed the survey. The number of students who completed the assignment varied per year based on class size (between 130 and 151 per year). In total, there were 1,098 individual student responses for this analysis.

Student general demographics

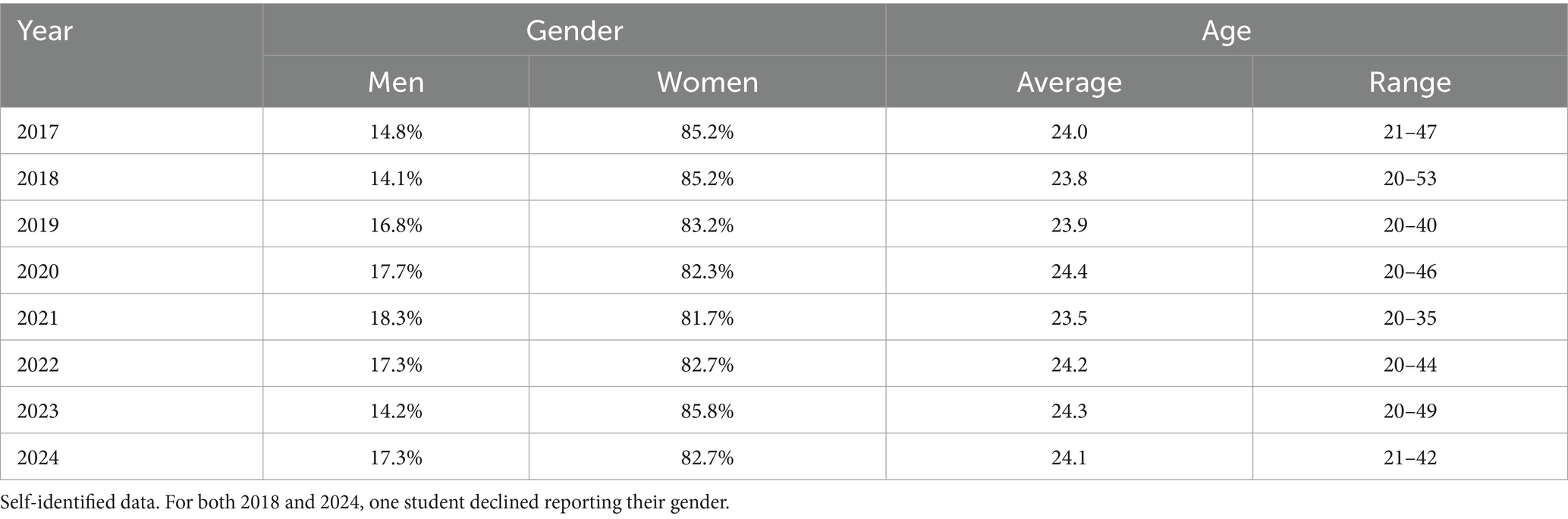

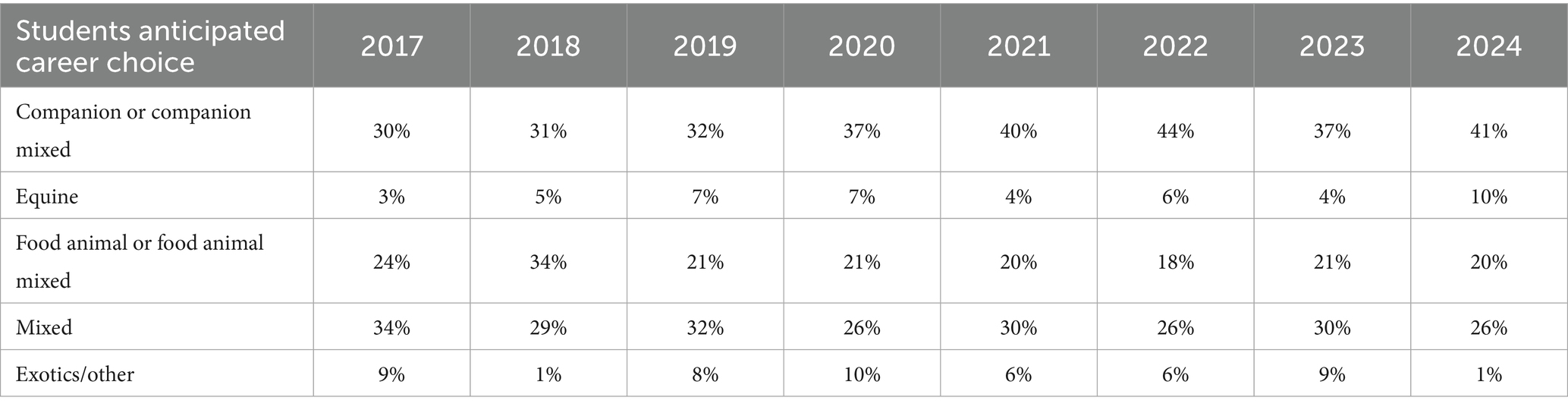

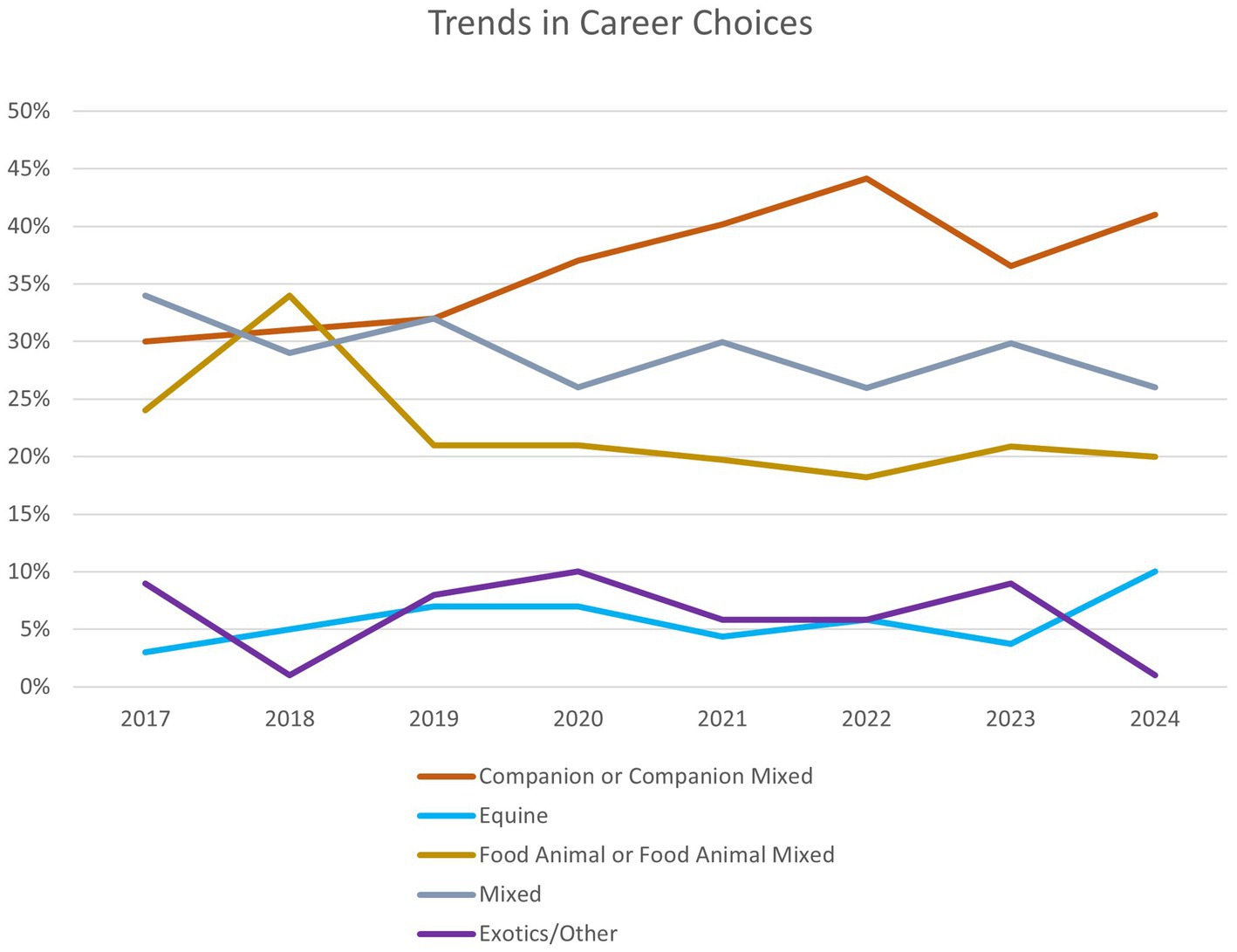

We did not match individual student demographics or other individually identifiable information with the responses, as the student’s name was removed from the dataset prior to analysis. We did not, therefore, correlate any unique identifiable student information and any individual response. For general context relative to the characteristics of each cohort, we present the age and gender distributions for each of the classes within our sample, as self-reported in admissions data collected at the time of matriculation into the first semester of the veterinary curriculum (Table 1). Gender distribution did not greatly vary across the years, with most students in each of the classes identifying as female (81.7–85.8%, depending on the class year). The average age of students was consistent across the classes as well (23.5–24.4 years of age). Given that we did not identify individual answers by gender and age across the classes, we did not include these variables as covariates within our analyses. In a separate class assignment, students were asked about their planned practice species (Table 2; Figure 1). This information was similarly not directly linked to the word choice data in this study. Therefore, we did not correlative species of interest and word choices recorded and provide this here for the general context of the population of students.

Unique word choices

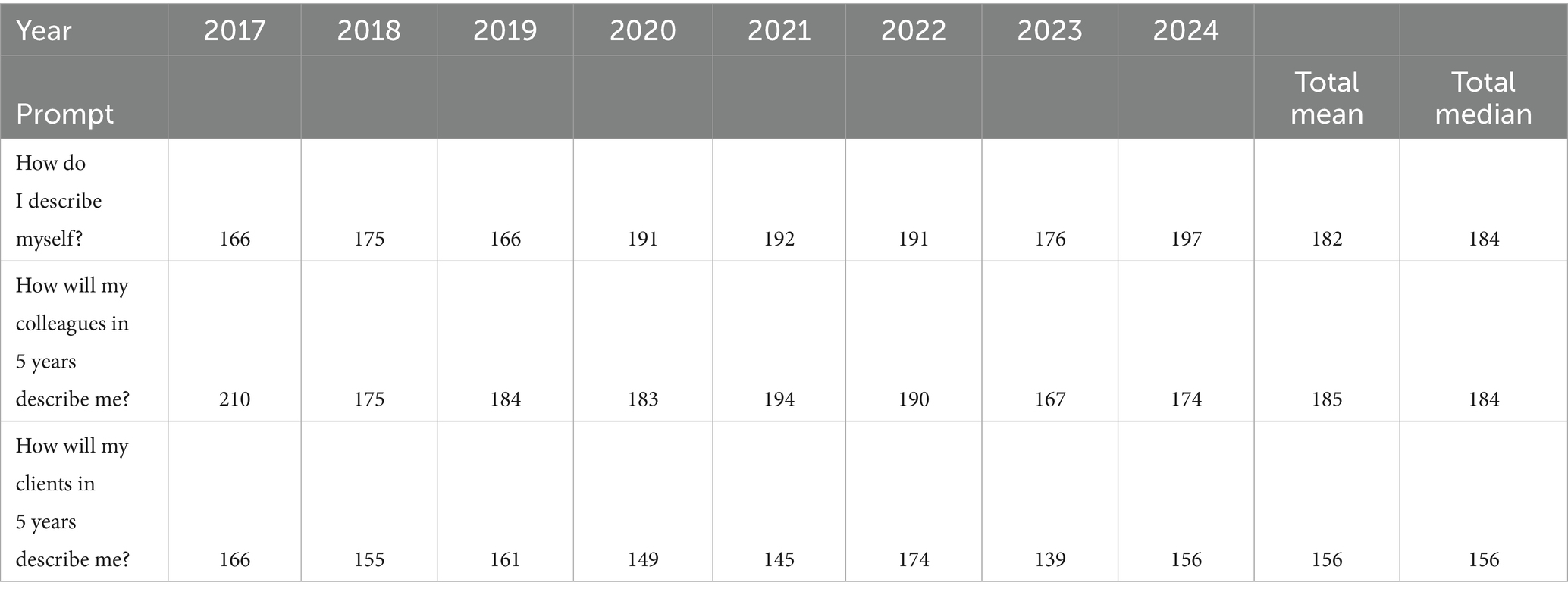

Students in each class were recorded between 139 and up to 210 unique words as descriptors for each of the three prompts (Table 3). No student recorded the same word more than once in any of their responses. For all years combined, students chose an average of 182, 185, and 156 unique words with a median of 184, 184, and 156 unique words to answer each of three questions (Question one, Question two, and Question three, respectively). For the questions “How would you describe yourself?” (Question one) and “How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?” (Question two), students recorded approximately the same number of unique words (median of 184), whereas for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?” (Question three), students recorded fewer unique words (with a median of 156 words—approximately 15% less unique word choices compared with the other questions responses).

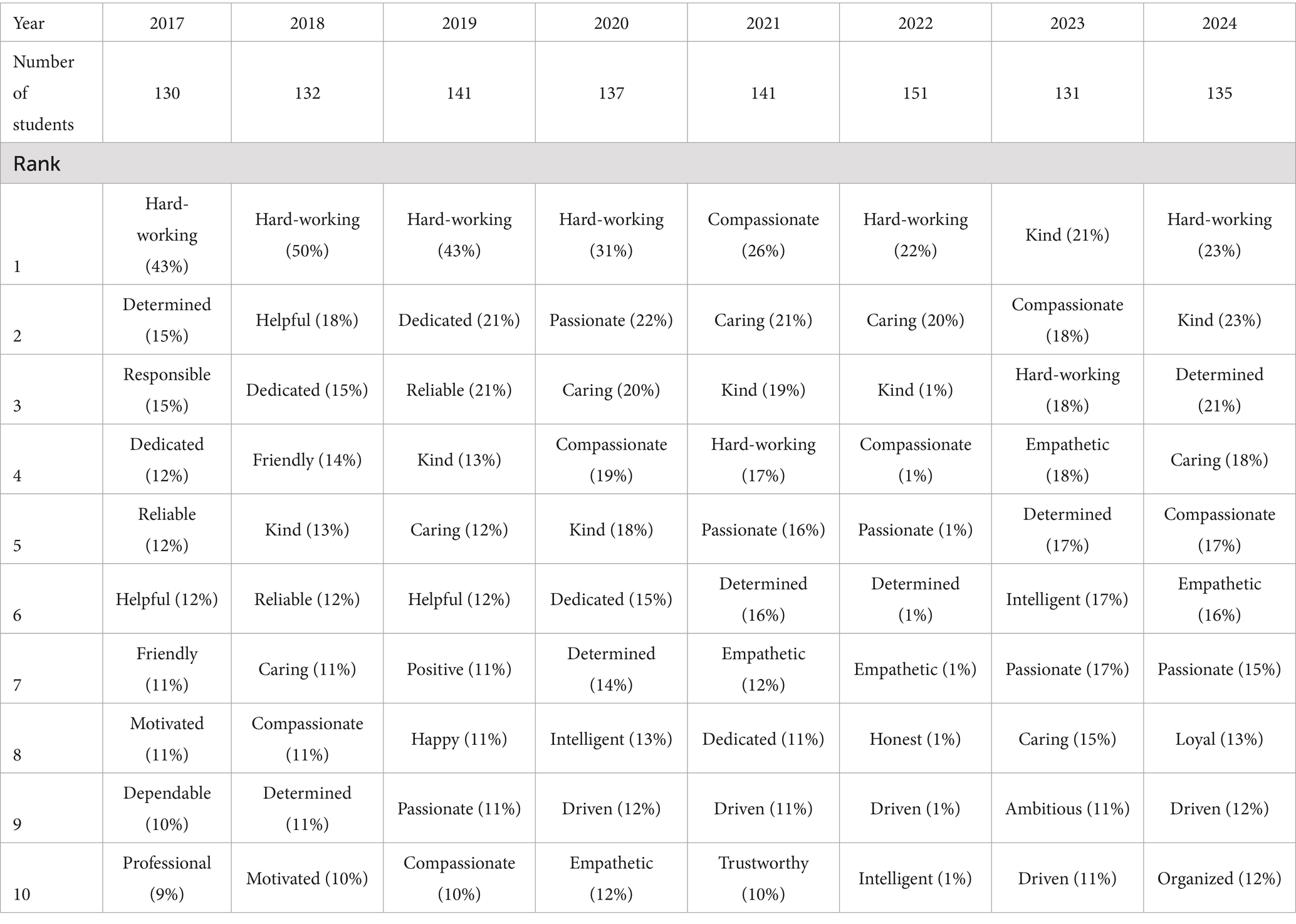

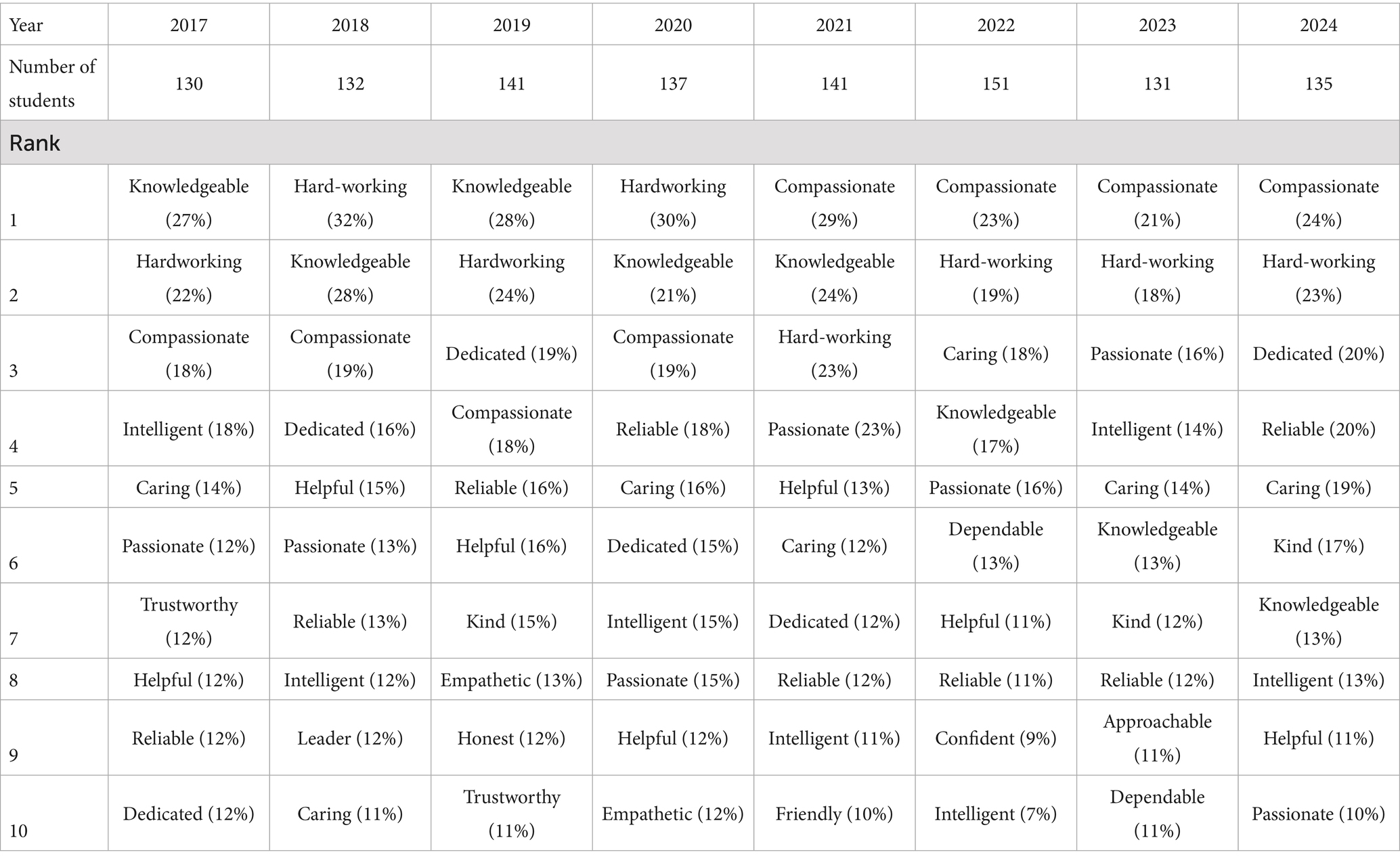

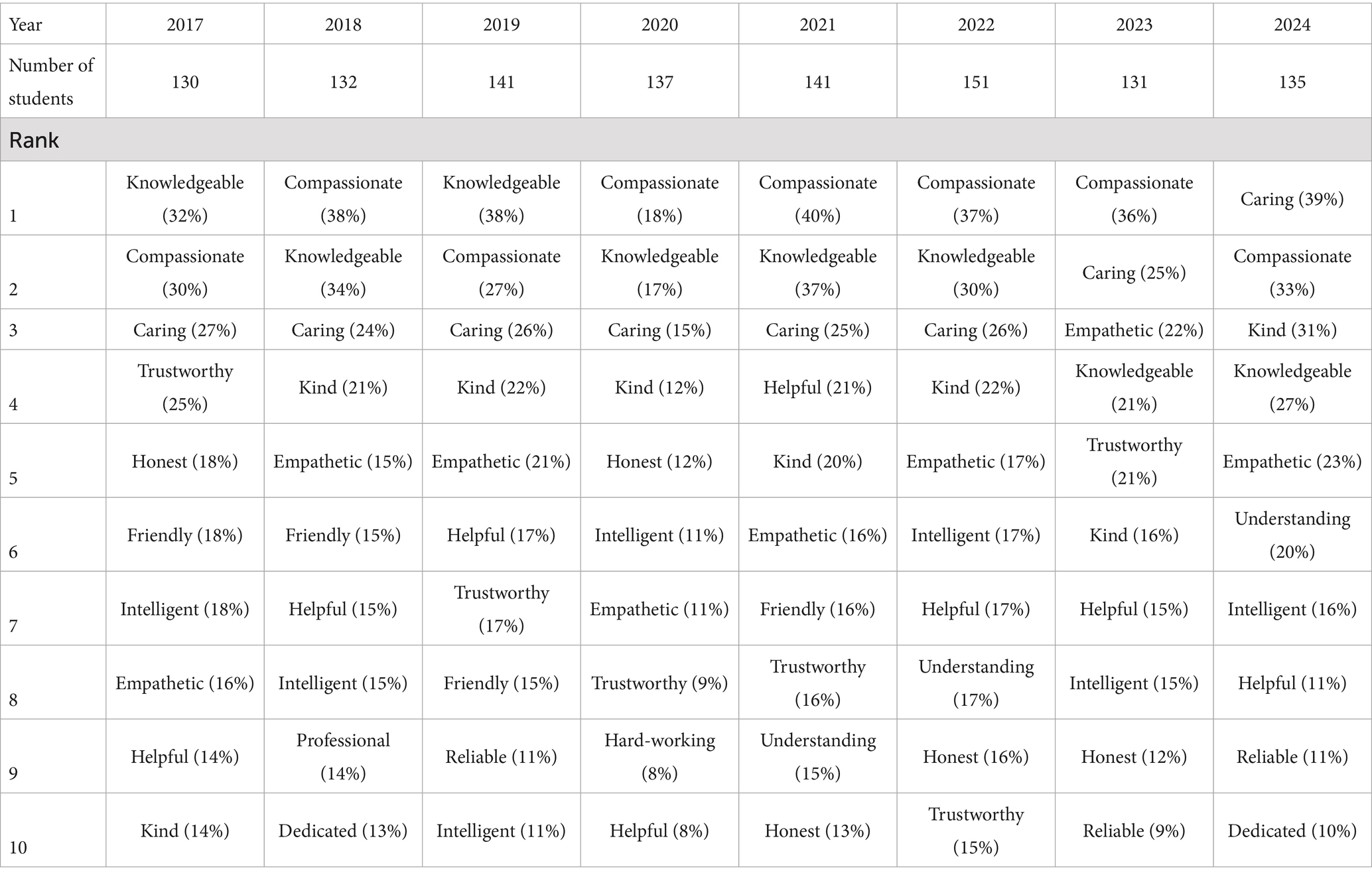

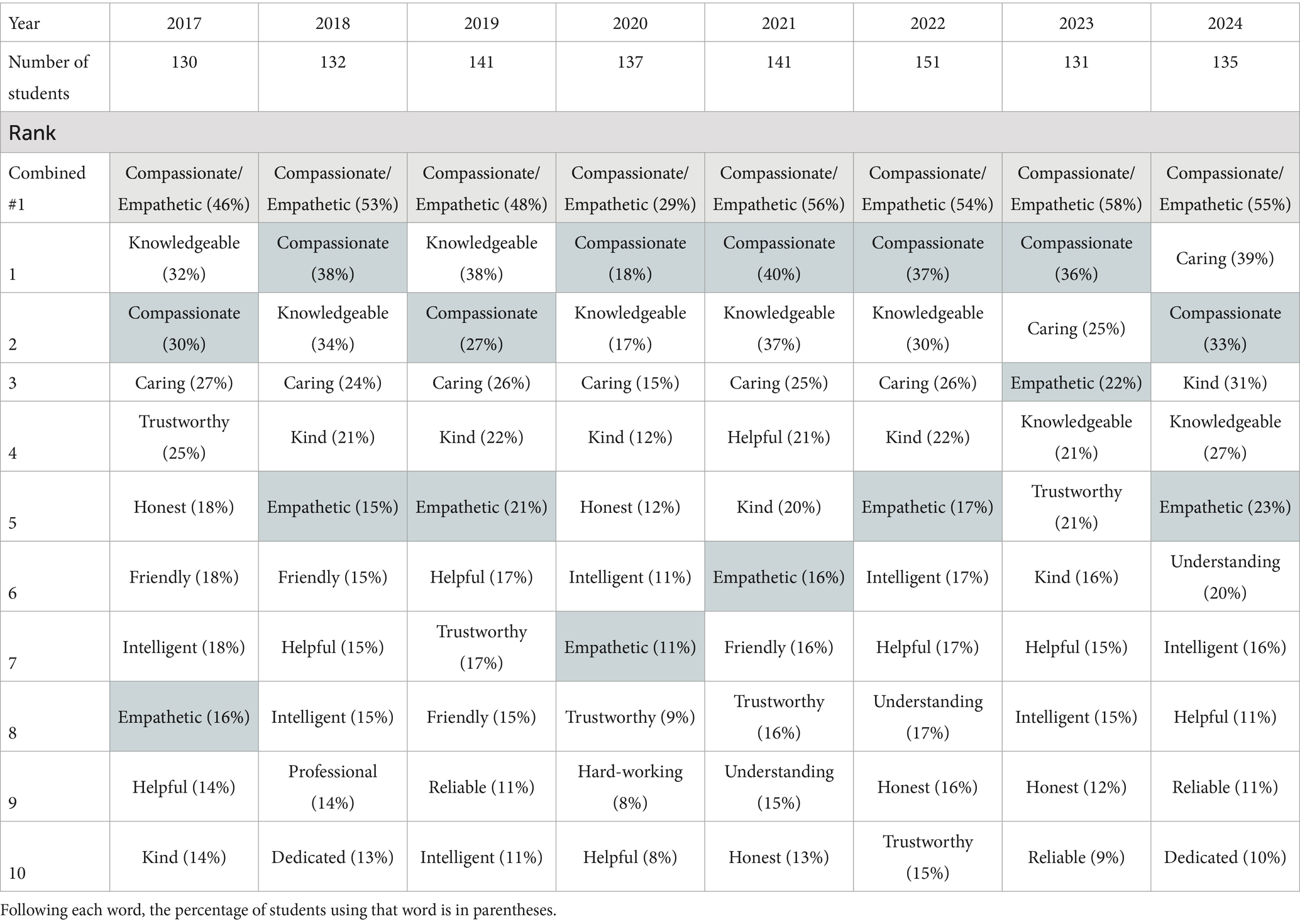

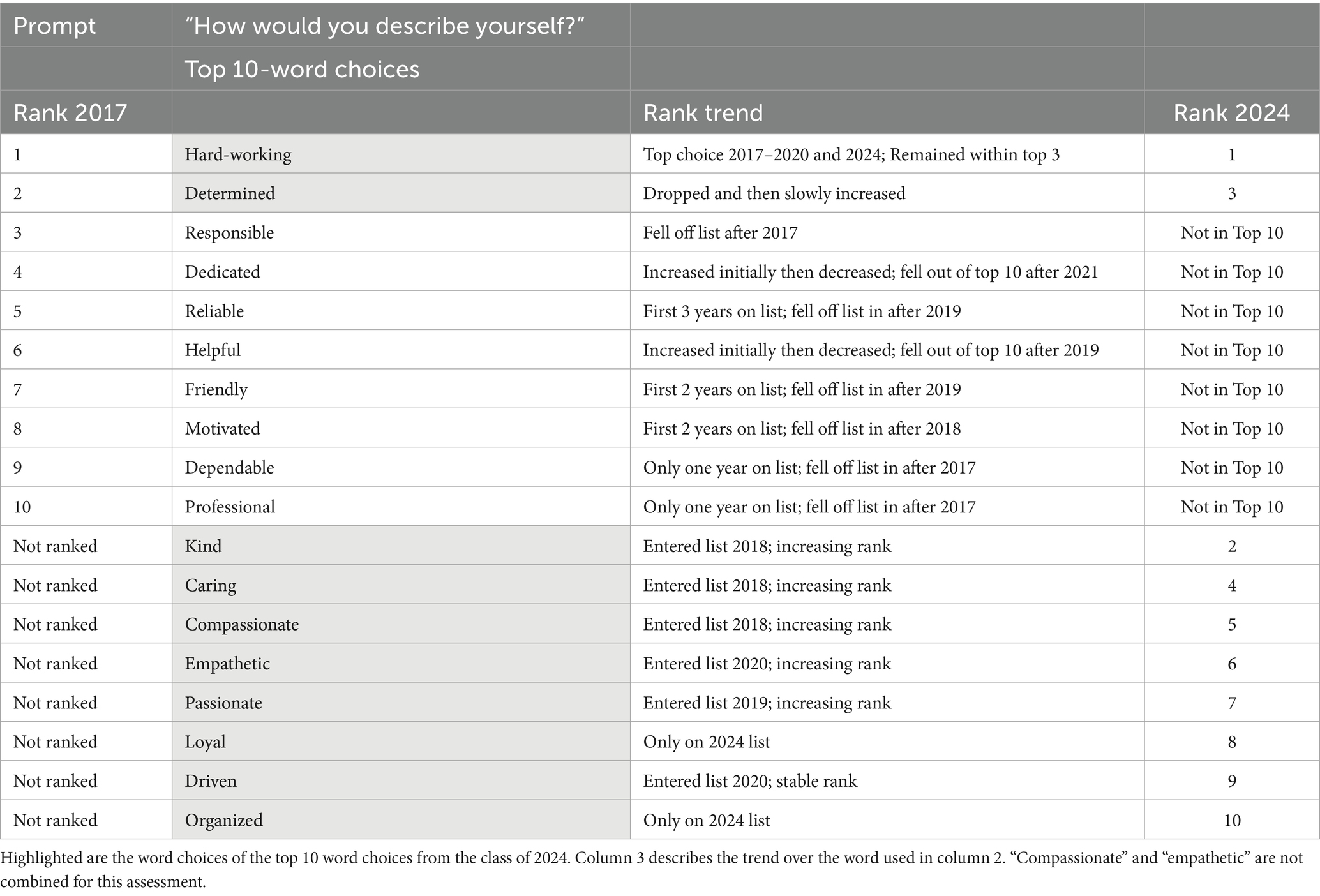

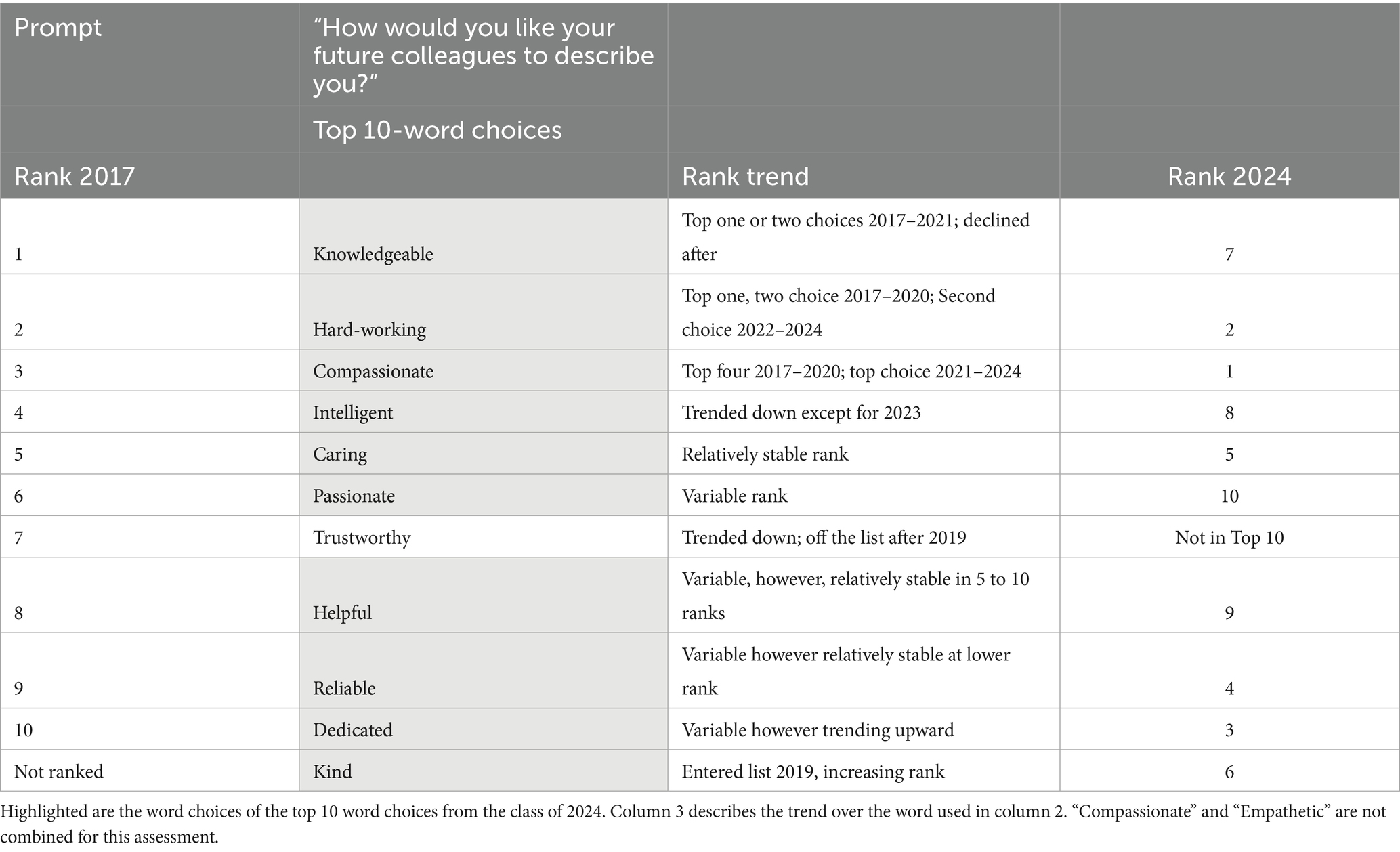

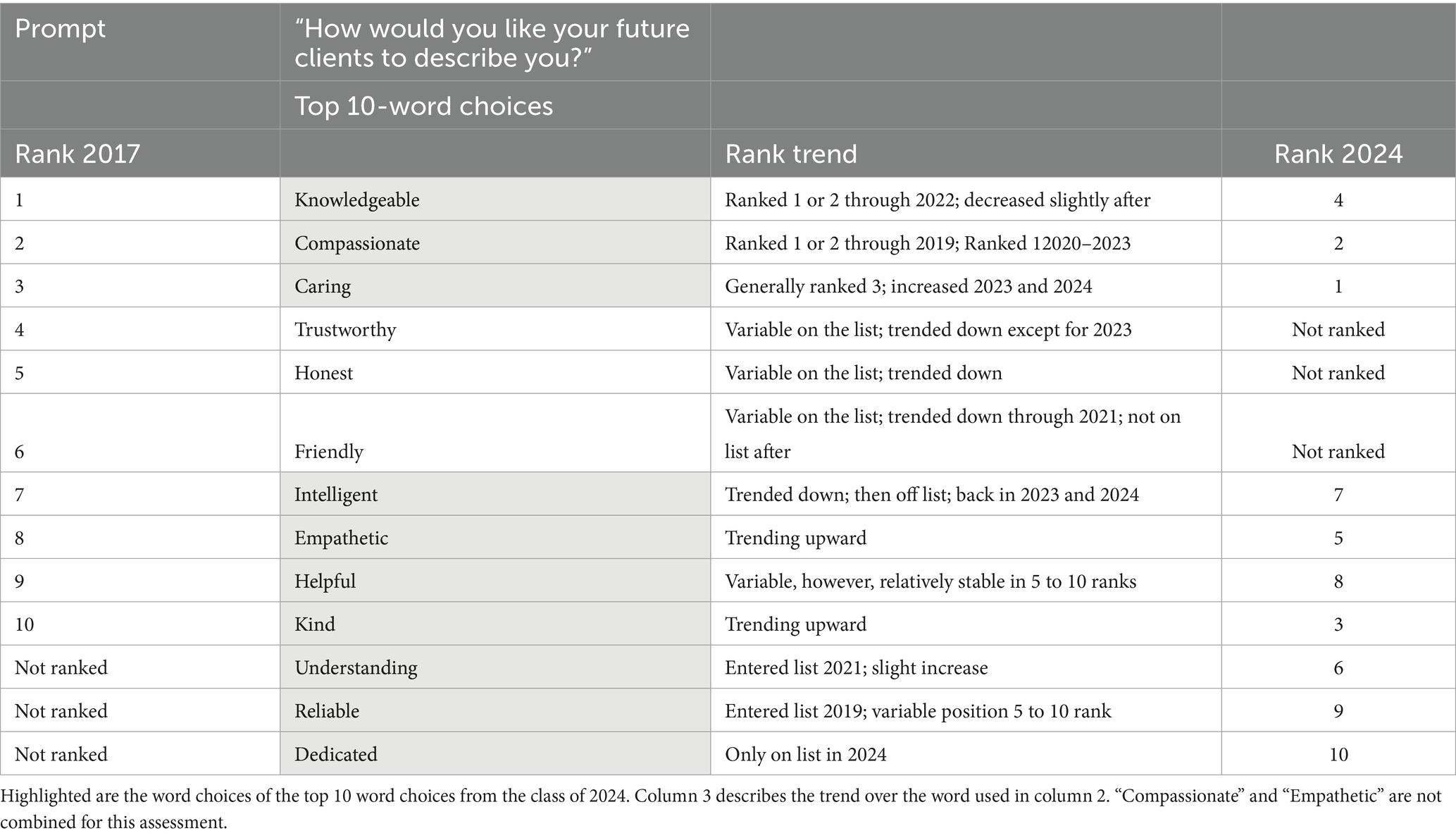

The top 10 word choices based on absolute counts relative to how many students recorded that unique word for each of the prompts/student cohort are shown in Tables 4–6. Combining all years, the 10 most common words used to describe themselves based on the prompt “How would you describe yourself?,” beginning with most commonly recorded, were “Hard-working,” “Kind,” “Caring,” “Compassionate,” “Determined,” “Dedicated,” “Passionate,” “Empathetic,” “Helpful,” and “Reliable.” The most common 10 words used to describe themselves based on the prompt “How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?,” beginning with most recorded, were “Hard-working,” “Compassionate,” “Knowledgeable,” “Caring,” “Reliable,” “Passionate,” “Dedicated,” “Helpful,” “Intelligent,” and “Kind.” The most common 10 words used to describe themselves based on the prompt ““How would you like your future clients to describe you?,” beginning with most recorded, were “Compassionate,” “Knowledgeable,” “Caring,” “Kind,” “Empathetic” “Helpful,” “Intelligent,” “Trustworthy,” “Friendly,” and “Honest.” Following the initial analysis, the number of responses for the word “Compassionate” was combined with number of responses for the word “Empathetic” as these word choices are often used interchangeably by individuals to describe the same “caring” concept. The combination of these word choices was the most recorded overall word choice in all years in the two future-self questions (i.e., envisioned descriptions by colleagues and clients) over this study period (Table 7).

Table 4. Most common word choices (ranked) for the prompt “How would you describe yourself?” following each word, the percentage of students using that word is in parentheses.

Table 5. Most common word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future veterinary colleagues to describe you?” following each word, the percentage of students using that word is in parentheses.

Table 6. Most common word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?” following each word, the percentage of students using that word is in parentheses.

Table 7. Most common ranked word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?” when “compassionate” is combined with “empathetic” (highlighted when ranked as individual word choices).

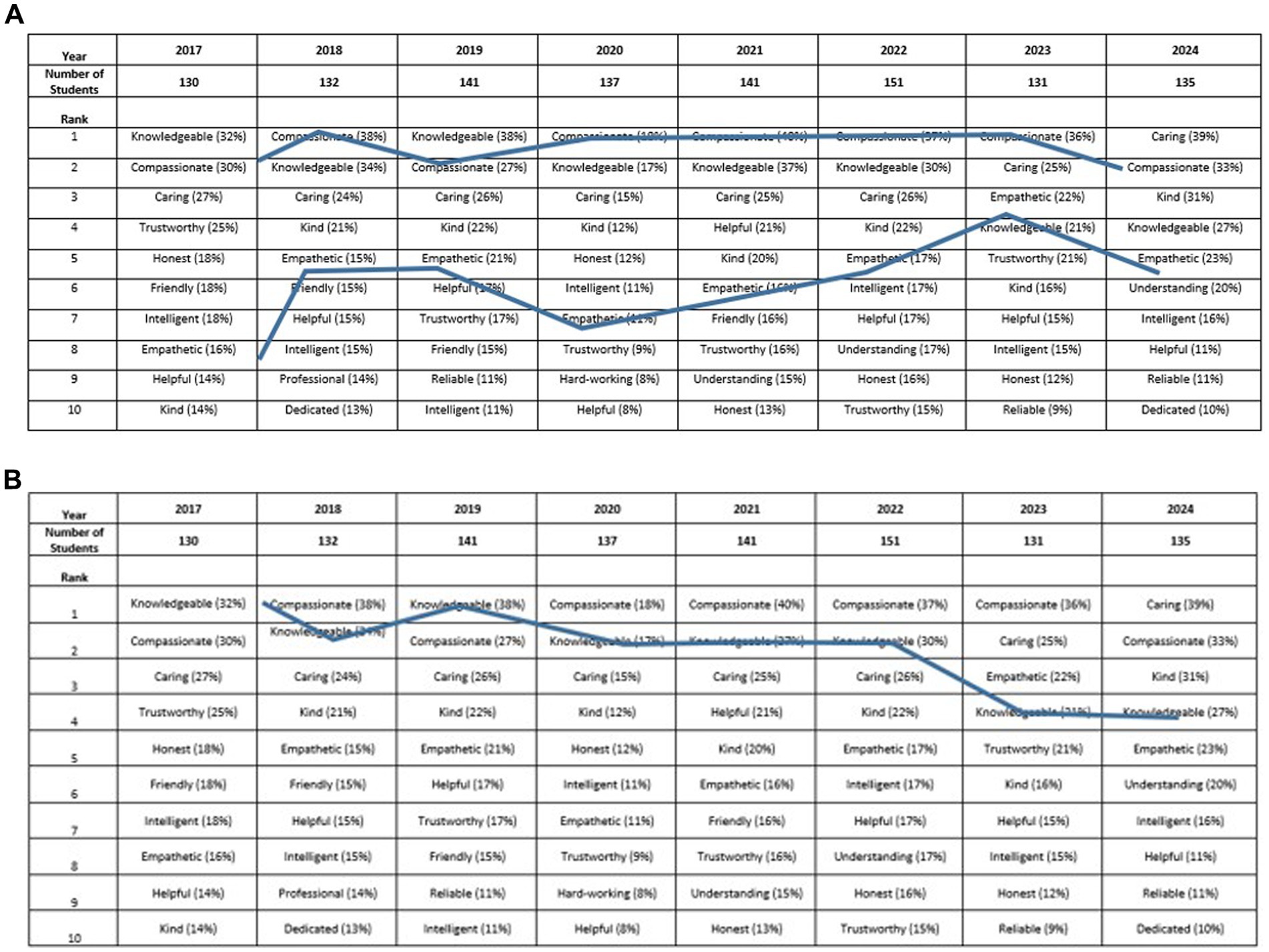

Interestingly, students most often described themselves as “hard-working” from 2017 to 2019. From 2020–2024, however, there was a shift in self-description word choices to “Compassionate” and “Empathetic” as the most common descriptors recorded. When prompted about how they wanted to be described by their future veterinary colleagues, students from 2017 and 2018 most commonly used the words “Knowledgeable” or “Hard-working.” Again, there was a comparable shift in 2019 from these descriptors to recording the words “Compassionate” and/or “Empathetic” as the most common descriptor (Tables 8–10; Figure 2A). In general, students consistently wanted clients to describe them as veterinarians, as “Compassionate,” and/or “Empathetic,” and this was preserved throughout the years (Table 6). “Knowledgeable” was also a common word choice throughout the years; however, it was trending slightly downward in recent years compared with “Compassionate,” “Empathetic,” “Kind,” and or “Caring” (Figure 2B).

Table 8. Trends in word choices for the prompt “How would you describe yourself?” column 1 is the rank from the class of 2017, while column 4 is the rank of the same word by the class of 2024.

Table 9. Trends in word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future colleagues to describe you?” column 1 is the rank from the class of 2017, while column 4 is the rank of the same word by the class of 2024.

Table 10. Trends in word choices for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?” column 1 is the rank from the class of 2017, while column 4 is the rank of the same word by the class of 2024.

Figure 2. (A) Word trends for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?”—“Compassionate” and “Empathetic”. The percentages are the number of students that recorded this word as one of their five descriptors. “Compassionate” and “Empathetic” are not combined for this assessment. (B) Word trends for the prompt “How would you like your future clients to describe you?”—“Knowledgeable”. The percentages are the number of students who recorded this word as one of their five descriptors. “Compassionate” and “Empathetic” are not combined for this assessment.

Discussion

In this assignment, first-year students self-reflected on their current and future selves in the process of conceptualizing a future “professional self.” We often find student responses such as these useful in developing various follow-up educational activities and discussions. We chose to collect these data from first-year veterinary students as the concept of professional “identity” was a subsequent class discussion (the next class week following completion of the assignment), and the grouped student responses were used to frame that subsequent class discussion.

In summarizing these responses, we decided to present this information with descriptive statistics given the self-reflective nature of the assignment and as this was a unique cohort from only one institution from one country. Clearly, as important factors such as environment and culture may influence any student’s response, each institution will likely need to collect similar data to contextualize the results for that institution’s curriculum development. Our process offers one potential mechanism for the collection of this information and a base of comparison.

As the students were free to choose any potential word choice to answer these self-reflective questions, the words they recorded are inherently interesting to us as educators in our individual institution and contribute to our understanding of students’ self-view both now and in the future. Overall, students recorded a range of descriptors compared with a finite or uniform group of self-descriptive word choices. As individuals normally vary in self-reflective word choices, this diversity in word choices was not unexpected (15). It is notable, however, that relatively fewer unique word choices were recorded when asked how the students wanted to be described by future clients. This prompts several questions: Could these results indicate that students generally have more limited and/or universal views of their identity goals relative to future client expectations as compared to self or future colleagues? Or is this an inherent bias because of the question sequencing, given that the question relative to future client views was the third of the series and, therefore, the students defaulted to word choices that they had already recorded in prior questions (i.e., an availability bias)? Or do students believe that clients have inherently standardized expectations for them as veterinarians, and therefore, the students implicitly understand these client expectations and just articulate them? As we did not investigate further with the students in this assignment about why they chose the words that they did, we could not answer these questions definitively with the data available from this exercise. These questions, however, do provide opportunities for further student discussion during future curricular activities.

Fundamentally, individuals should be, but also may not be, the most appropriate assessors of their own skills and attributes when asked to perform various self-assessments (6, 10, 13, 14, 18, 28, 40, 45, 46, 51, 53, 57, 58, 65). When the performance criteria are objective and measurable, individuals are usually more accurate in rating their own skills relative to these benchmarks. When the assessments are less quantifiable and/or theoretical, such as “competence,” individuals are less accurate in their self-assessments relative to an external objective standard. For this study, we were not intending to determine if these students are, in fact, what they say they are or will be. More so, we were interested in what they were thinking about themselves now and in the future as veterinary professionals.

Relative to self and future colleague descriptors, there was an interesting shift from the initial student cohorts (e.g., 2017 and 2018) from words “Hard-working” and “Knowledgeable” to later cohorts’ words of “Compassionate,” “Empathetic,” and “Caring.” As each student cohort was relatively early in the veterinary curriculum and had not been explicitly exposed to concepts of “Compassion” and “Empathy” within our curriculum at this point, it seems reasonable to conclude that these frames of reference developed prior to entering the veterinary curriculum or potentially within the first weeks of their educational activities. As professional identity is a dynamic process, it is likely that some influence on student word choices was the result of previous veterinary-related experiences prior to entering the curriculum.

Within the limitations inherent in this unique dataset, there are clear themes that emerged from these results that prompt educational consideration. As might be expected, students chose descriptors such as “Hard-working,” “Knowledgeable,” “Compassionate,” and “Empathetic” as both current and future descriptors. In a medical context, it seems intuitively reasonable, at least for clinically focused individuals, to desire to be described as “Caring” for others.

The words “Compassionate” and “Empathetic” were subsequently combined for an independent analysis, given that individuals frequently use these words interchangeably and without a common agreement on the difference in meaning. While “Compassionate” and “Empathetic” were often chosen as a descriptor, when combined, “Compassionate” and “Empathetic” were the top-ranked words recorded by 46 to 58% of students (depending on the year) when answering the question about how they want to be described by future clients. The fall 2020 cohort was the one outliner with just under 30% of students recording one or the other of these terms. Data from other studies of veterinary and client surveys have identified the influence of similar word choices on both professional stereotypes and on client expectations for veterinary behavior (3, 8, 47, 67). In one study (67), on evaluating reasons for potential litigation against veterinarians, clients noted “Compassion” and “Empathy,” or lack thereof, as important in their decision-making process to pursue litigation. This fact emphasizes the importance of projecting a professional “identity,” such as “Compassionate,” and most importantly, to be intentional in doing so, given the impact of these professional identities on self and others.

It deserves equal consideration that collectively 40% of students did not record either “Compassionate” or “Empathetic” as a current or future descriptor. Does this suggest that being or viewed as being “Compassionate” and/or “Empathetic” is not an identity goal of some students? Or did these students assume these descriptors were inherent as a professional expectation and choose other words instead? Do students with certain future career tracks, for example, not view these descriptors as necessary professional “identities”? While we did not independently correlate word choice with career choice in this analysis, at our institution, first-year veterinary students’ future career interests trended upward in the companion animal and or companion animal mixed focus during the study period. This prompts future analysis, for example, related to the influence of choice of career focus and the necessity to be viewed as “Compassionate” or “Empathetic.” Additionally, are we choosing, either explicitly or implicitly, for certain professional “identities through our admission processes? Are individuals with these behavioral characteristics inherently choosing the veterinary profession because of preconceived professional stereotypes prior to veterinary college? These questions may be answerable in the future through the analysis of our admission evaluations and other selection criteria for accepting students into the veterinary curriculum.

Our results do potentially create a dilemma for educators in developing curriculum to enhance compassion and empathy as a competency (9, 23, 29–33, 35–38, 41, 50, 52, 54–56, 59, 60). While many students would likely engage in developing this type of skill development, should all students, even if not their individual professional priority, be exposed to educational activities such as compassion training? Similarly, whether developing compassion is or should be an educational outcome or competency of the veterinary curriculum? Our bias, certainly for clinically focused individuals, is that the development of “compassion” as a foundational clinical skill is imperative for medical professionals and contributes positively to future success in direct patient/client interactions, as well as the global reputation of the veterinary profession.

Finally, there is another important question for consideration: Does compassion develop organically during the veterinary educational process? Data from some human medical settings suggests “no” or not necessarily (41). In some environments, especially as students develop more medical knowledge, their development of “Compassion” may, in fact, decrease (41). This dynamic may be a contributing factor to compassion fatigue and other negative perceptions of the profession.

If the development of compassion is a competency outcome goal, then there is evidence that incorporation of specific exercises to develop compassion as a skill can be helpful (9, 23, 29–33, 35–38, 41, 50, 52, 54–56, 59, 60). As an example, training in a compassion meditation has been shown to result in actual alterations in brain structure as an outcome (32, 33). In our curriculum, we have both explicit and implicit opportunities for students to develop knowledge and skills in being “compassionate.” As an example, students are explicitly asked in our curriculum to explore the meaning of the words “Compassion” and “Empathy” in both the first year “Careers” class and in the third year “Communication” class. These are core curriculum classes that are components of a series of courses primarily to develop the “non-technical” skills of veterinary students. In the “Communication” course, students have four interactions with simulated clients, and these clients’ evaluation rubric includes an assessment of whether the student was “Compassionate.” Following the simulated client interaction, the students are provided direct feedback as to whether the client felt that they were, in fact, “Compassionate” toward them and their animal. Additionally, students in the first year become Fear-Free certified as implicitly fostering a compassionate viewpoint of animal handling (16). While not always explicit, role modeling by faculty and staff in how to demonstrate compassion is likely the most important influence on the students’ future behaviors in this competency. This facet of implicit education is dependent on the individual faculty and staff member and is, therefore, an uncontrolled variable. We should, however, ask the important question: Are we role modeling compassionate behaviors in both the formal and “hidden” curriculum? (3, 25, 42, 61). Based on the results of our analysis and the common themes that emerged, it seems reasonable that we should be explicit in teaching “Compassion” as a clinical skill in clinically-focused individuals and to consistently role model that behavior in teaching laboratories, preceptors, and other educational activities external to the veterinary college and in clinical practices that we use for student education.

In conclusion, as veterinary educators and as future veterinary colleagues as well as potential clients, it seems critically important that we recognize and understand both the preserved as well as the changing perspectives of students relative to a range of aspects of the veterinary career to maintain contemporary in our curriculum and professional delivery, and equally to understand what is important to the modern veterinary student. Hopefully, the characteristics and outcome behaviors we instill in our students align with their future “identity” for our profession as these students enter the workforce as veterinary professionals.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Iowa State University Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB 23-381) review and deemed exempt. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because this study was deemed exempt due to the retrospective analysis and that the participants were not identified in the analysis.

Author contributions

RB: Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Data curation. JC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AM: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1. Aboujaoude, EN. (2023). Attitude over skills: why mindset matters more than skills in hiring. Linkedin. Available online at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/attitude-over-skills-why-mindset-matters-more-than-njeim-aboujaoude-dxk4e/

2. Adams, K, Hean, S, Sturgis, P, and Clark, JM. Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learn Health Soc Care. (2006) 5:55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-6861.2006.00119.x

3. Agathou, S, Stratis, A, Routh, J, and Paramasivam, S. Professional stereotypes among specialties and fields of work within the veterinary community. Vet Rec. (2022) 191:e1486. doi: 10.1002/vetr.1486

4. Ahmad Gholami, A, Abedi, S, and Asemani, O. Development and establishment of professional identity during academic education; a qualitative study on the lived experiences of pharmacy students. J Educ Res Rev. (2924) 12:46–54. doi: 10.33495/jerr_v12i3.23.139

5. Alex Osei Bonsu, AO, and Koryoe Anim-Wright, K. Personal branding: a systematic literature review. Int J Market Stud. (2024) 16:30–8. doi: 10.5539/ijms.v16n1p30

6. Andrade, HL. A critical review of research on student self-assessment. Front Educ. (2019) 4:87. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00087

7. Brower, T. (2023). Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tracybrower/2023/09/28/how-to-describe-yourself-in-an-interview-words-to-use-with-examples/

8. Brown, FN, and Jones, JV. Client experiences with veterinary professionals: a narrative inquiry study. N Z Vet J. (2025) 73:165–77. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2024.2433583

9. Burack, JH, Irby, DM, Carlin, JD, Root, RK, and Larson, EB. Attending physicians’s responses to problematic behaviors. Teach Compas Resp. (1999) 14:49–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00280.x

10. Chung, CK, and Pennebaker, JW. Revealing dimensions of thinking in open-ended self-descriptions: an automated meaning extraction method for natural language. J Res Pers. (2008) 42:96–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.006

11. Crigger, N, and Godfrey, N. From the inside out: a new approach to teaching professional identity formation and professional ethics. J Prof Nurs. (2014) 30:376–82. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.03.004

12. Cruess, RL, Cruess, SR, Boudreau, JD, Snell, L, and Steinert, Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. (2014) 89:1446–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

13. Davis, DD, Mazmanian, PE, Fordia, M, Harrison, RV, Thorpe, KE, and Perrier, L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence. JAVMA. (2006) 296:1094–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094

14. Dishon, N, Oldmeadow, JA, Critchley, C, and Kaufman, J. The effect of trait self-awareness, self reflection, and perceptions of choice meaningful ness on indicators of social identity within a decision-making context. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:2034. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02034

15. Fast, LA, and Funder, DC. Personality as manifest in word use: correlations with self-report, acquaintance report. Behavior. (2008) 94:334–46. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.334

16. Fear Free. (2025). Available online at: https://fearfreepets.com/fear-free-certification-overview/

17. Fitzgerald, A. Professional identity: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. (2020) 55:447–72. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12450

18. Gabbard, T, and Romenelli, F. The accuracy of health professions students’ self-assessments compared to objective measures of competence. Am J Pharma Educ. (2021) 85:8405–280. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8405

19. Goldie, J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. (2012) 34:e641–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159x.2012.687476

20. Gorbatov, S, Khapova, SN, and Lysova, EI. Get noticed to get ahead:the impact of personal branding on career success. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:2662. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02662

21. Heffernan, P. (2018) The psychology of words: revealing more than you realize. 2/8/18 10:00 AM. Available online at: https://www.marketing-partners.com/conversations2/the-psychology-of-words-revealing-more-than-you-realize

22. Heine, A. (2024). Available online at: https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/interviewing/interview-question-how-would-you-describe-yourself

23. Hess-Holden, CL, Jackson, DL, Morse, DT, and Monaghan, CL. Understanding non-technical competencies: compassion and communication among fourth-year veterinarians-in-training. JVMA. (2019) 46:506–17. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0917-131rl

24. Hirsh, JB, and Petterson, JB. Personality and language use in self-narratives. J Res Person. (2009) 43:524–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.01.006

25. Hunze, AJ, and Seals, C. Exploring fourth-year students’ perceptions of the hidden curriculum of a doctor of veterinary medicine program through written reflections. Educ Health Prof. (2020) 3:121–8. doi: 10.4103/EHP.EHP_23_20

26. Indeed Editorial Team. (2025). Available online at: https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/skills-employers-look-for

27. Jain, V. (2020). Attitude vs skills – what will you choose? Linkedin. Available online at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/attitude-vs-skills-what-you-choose-vinay-jain/

28. Karpen, SC. The social psychology of biased self-assessment. Am J Pharma Educ. (2018) 82:441–8. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6299

29. Kelm, Z, Womer, J, Walter, JK, and Feudtner, C. (2014) Intervention to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ, 14: Available online at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/14/219

30. Kemper, KJ, and Shaltout, HA. Non-verbal communication of compassion:measuring psychophysiologic effects. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2011) 11:132. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-132

31. Kim, SS, Kaplowitz, S, and Johnston, MV. The effect of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. (2004) 27:237–51. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037

32. Klimecki, OM, Leiberg, S, Lamm, C, and Singer, T. Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cereb Cortex. (2013) 23:1552–61. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs142

33. Klimecki, OM, Leiberg, RM, and Singer, T. Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. SCAN. (2019) 9:873–9. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst060

34. Knowledge at Wharton Staff. (2018) How what you say reveals more than you think. Available online at: https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/say-reveals-think/

35. Konrath, SH, O’brien, EH, and Hsing, C. Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: a meta-analysis. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. (2011) 15:180–98. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377395

36. Lederhouse, C. (2023) Lessons in ‘compassionomics’ prioritizing empathy is a valuable approach for human, animal medicine. Available online at: https://www.avma.org/news/lessons-compassionomics

37. Little, P, White, P, Kelly, J, Everitt, H, and Mercer, S. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention targeting predominantly non-verbal communications in general practice consultations. British J Gen Pract. (2015) 65:e351–6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15x685237

38. McArthur, M, Mansfield, C, Matthew, S, Zaki, S, Brand, C, Andrews, J, et al. Resilience in veterinary students and the predictive role of mindfulness and self-compassion. JVME. (2017) 44:106–15. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0116-027R1

39. MentorCruise Staff. (2023). Available online at: https://mentorcruise.com/blog/best-answers-career-aspirations-questions-and-how

40. Neubauer, AC, and Hofer, G. Self-estimates of abilities are a better reflection of individuals’ personality traits than their abilities and are also strong predictors of professional interests. Personal Individ Differ. (2021) 169:109850. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.109850

41. Neumann, M, Edelhauser, F, Tauschel, D, Fischer, MR, Wirtz, M, Woopen, C, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. (2011) 86:996–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

42. Order, CA, and May, SA. The hidden curriculum of veterinary education: mediators and moderators of its effects. J Vet Med Educ. (2017) 44:542–51. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0416-082

43. Pennebaker, JW, Mehl, MR, and Niederhoffer, KG. Psychological aspects of natural language use: our words, our selves. 2003. Annu Rev Psychol. (2003) 54:547–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041

44. Porter, J, and Wilton, A. Professional identity of allied health staff. J Allied Health. (2019) 25:348–73. doi: 10.1080/10447310902864951

45. Pronin, E, and Hazel, L. Humans’ Bias blind spot and its societal significance. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. (2023) 32:402–9. doi: 10.1177/09637214231178745

46. Pronin, E, Lin, DY, and Ross, L. The bias blind spot: perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. (2002) 28:369–81. doi: 10.1177/0146167202286008

47. Pyatt, AZ, Walley, K, Wright, G, and Bleach, E. Co-produced Care in Veterinary Services: a qualitative study of UK stakeholders’ perspectives. Vet Sci. (2020) 7:149. doi: 10.3390/vetsci7040149

48. Rasmussen, P, Henderson, A, Andrew, N, and Conroy, T. Factors influencing registered nurses' perceptions of their professional identity: an integrative literature review. J Contin Educ Nurs. (2018) 49:225–32. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20180417-08

49. Reissner, S, and Armitage-Chan, E. Manifestations of professional identity work: an integrative review of research in professional identity formation. Stud High Educ. (2024) 49:2707–22. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2024.2322093

50. Riess, H, Kelley, JM, Bailey, RW, Dunn, EJ, and Phillips, M. Empathy training for resident physicians: a randomized controlled trial of a neuroscience-informed curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1280–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2063-z

51. Ross, JA. The reliability, validity, and utility of self-assessment. Pract Assess Res Eval. (2006) 11:10. doi: 10.7275/9wph-vv65

52. Satterfield, JM, and Hughes, E. Emotion skills training for medical students: a systematic review. Med Educ. (2007) 41:935–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02835.x

53. Showers, CJ, Ditzfeld, CP, and Zeigler-Hill, V. Self-concept structure and the quality of self-knowledge. J Pers. (2015) 83:535–51. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12130

54. Sinclair, S, Norris, JM, McConnell, SJ, Chochinov, HM, Hack, TF, Hagen, NA, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BCM Palliat Care. (2016) 15, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0

55. Sulzer, SH, Feinstein, NW, and Wendland, C. Assessing empathy development in medical education: a systematic review. Med Educ. (2016) 50:300–10. doi: 10.1111/medu.12806

56. Trzeciak, S, Roberts, BW, and Mazzarelli, AJ. Compassionomics: hypothesis and experimental approach. Med Hypoth. (2017) 107:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.08.015

57. Visapää, L. Self-description in everyday interaction: generalizations about oneself as accounts of behavior. Discourse Stud. (2021) 23:339–64. doi: 10.1177/14614456211009044

58. Weizhi, JL, Zhang, M, Wang, P, Liu, Y, and Ma, S. Know yourself: physical and psychological self-awareness with lifelog. Front Digit Health. (2021) 3:676824. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.676824

59. Weng, HY, Fox, AS, Shackman, AJ, Stodola, DE, Caldwell, JZK, Olson, MC, et al. Compassion training alters altruism and neural response to suffering. Psychol Sci. (2013) 24:1171–80. doi: 10.1177/09567976124469537

60. Weng, H, Hung, C, Liu, Y, Cheng, Y, Yen, C, Chang, C, et al. Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction, and patient satisfaction. Med Educ. (2011) 45:835–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03985.x

61. Whitcomb, TL. Raising awareness of the hidden curriculum in veterinary medical education: a review and call for research. J Vet Med Educ. (2014) 41:344–9. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0314-032R1

62. Wilson, I, Cowin, LS, Johnson, M, and Young, H. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. (2013) 25:369–73. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827968

63. Worthington, M, Salamonson, Y, Weaver, R, and Cleary, M. Predictive validity of the Macleod Clark professional identity scale for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. (2013) 33:187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.01.012

64. Yarkoni, T. Personality in 100,000 words: a large-scale analysis of personality and word use among bloggers. J Res Pers. (2010) 44:363–363, 373. doi: 10.1016/j./jrp.2010.04.001

65. Yeom, D, Stead, KS, Tan, YT, and McPherson, GE. How accurate are self-evaluations of singing ability? Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2023) 1530:87–95. doi: 10.1111/nyas.15081

66. Zarshenas, L, Sharif, F, Molazem, Z, Khayyer, M, Zare, N, and Ebadi, A. Professional socialization in nursing: a qualitative content analysis. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. (2014) 19:432–8. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25183987/

Keywords: veterinary student perspectives, descriptive words, professional identity, self-reflection, word choices

Citation: Bagley RS, Carnevale J and Mindthoff A (2025) Developing a veterinary professional “identity”: first year veterinary students’ perspectives on how they describe themselves now and as future veterinarians: 2017–2024. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1614449. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1614449

Edited by:

Marcos Perez-Lopez, University of Extremadura, SpainReviewed by:

Kirsty Hughes, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomJoaquín Jiménez Fragoso, Universidad de Extremadura, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Bagley, Carnevale and Mindthoff. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rodney S. Bagley, cnNiYWdsZXlAaWFzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Rodney S. Bagley

Rodney S. Bagley Joyce Carnevale

Joyce Carnevale Amelia Mindthoff

Amelia Mindthoff