- 1Medical University of South Carolina, College of Medicine, Charleston, SC, United States

- 2Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, United States

- 3Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, United States

We report the case of a 10-year-old girl with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia who exhibited transient resistance to propofol. While being treated with calaspargase pegol and dexamethasone during induction chemotherapy, she was found to have milky-appearing serum and bone marrow aspirate as well as markedly elevated triglycerides. Despite previously normal anesthetic responses, the patient required a markedly increased propofol dose (28 mg/kg)—over five times the range of her previous anesthetics (4.5–5.2 mg/kg)—to achieve adequate sedation for her bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Ultimately, normal propofol sensitivity returned after triglyceride normalization. This case highlights chemotherapy-induced hypertriglyceridemia as a reversible cause of anesthetic resistance and emphasizes the importance of considering lipid levels when an unusual response to routine anesthetic administration occurs.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy and is typically treated with a combination of chemotherapeutic agents, including glucocorticoids and asparaginase. In some patients, this regimen has been shown to cause reversible hypertriglyceridemia (1, 2). Patients with ALL undergo repeated lumbar punctures for intrathecal chemotherapy, which often requires sedation in the pediatric age group. At our institution, sedation is often achieved with propofol, a lipophilic drug whose unbound concentration has been shown to decrease in the presence of hypertriglyceridemia due to an increase in lipoprotein binding (3). There has been at least one case of anesthetic complications reported in a pediatric patient undergoing general inhalational anesthesia with concurrent chemotherapy-induced hyperlipidemia (4). The present case describes a previously unreported pattern in a pediatric ALL patient, characterized by a fluctuating response to propofol, coinciding with chemotherapy-induced hypertriglyceridemia and subsequent lipid normalization. At our institution, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval is not required for case reports. Written informed patient consent was obtained via signed institutional Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) documentation. This article adheres to the CARE (case report) guidelines.

Case description

A 10-year-old girl, weighing 34.8 kg, with a history of high-risk B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia presented to the oncology clinic for a planned bone marrow biopsy, aspirate, and lumbar puncture with intrathecal methotrexate at the end of her induction chemotherapy. Her medical history included precocious puberty. Her only scheduled home medication was gabapentin, and she had no known medication allergies. Review of systems was positive for upper and lower extremity proximal muscle weakness and pain that worsened following her most recent visit.

The past surgical history of the patient included tonsillectomy, port-a-cath placement, and bone marrow biopsies/aspirations and lumbar punctures with intrathecal chemotherapy. No previous anesthetic complications were noted by the patient's family or in review of her records. For her previous oncology-related procedures, the patient had tolerated propofol monitored anesthesia care (MAC) without any complications. The first procedure had a duration of 14 min, and a total of 180 mg (5.2 mg/kg) of propofol was administered. The second procedure had a duration of 25 min, and a total of 160 mg (4.5 mg/kg) of propofol was administered.

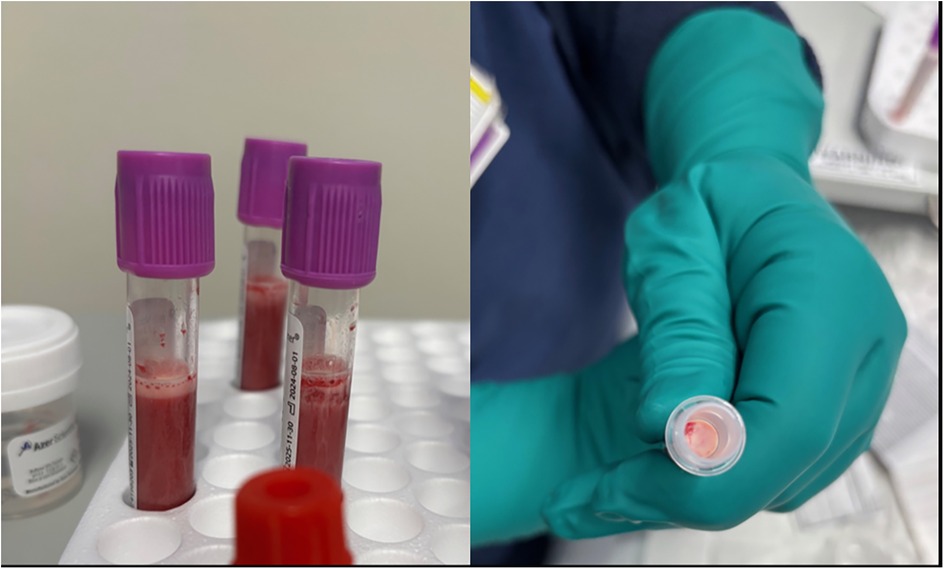

The patient had a port-a-cath that was accessed by the oncology nurse. Upon aspiration of the patient's blood immediately after accessing the port, the nurse noted the blood to have a milky, pink appearance. A lipid panel was obtained and sent to the laboratory at this time due to concern for hyperlipidemia based on the appearance of the blood sample and the known risk of hyperlipidemia with her chemotherapeutic regimen. The results of the lipid panel were not yet reported from the laboratory when the patient arrived at the outpatient procedure suite. At this time, the anesthesia team was unaware of the pending lipid panel or concern for severe hyperlipidemia.

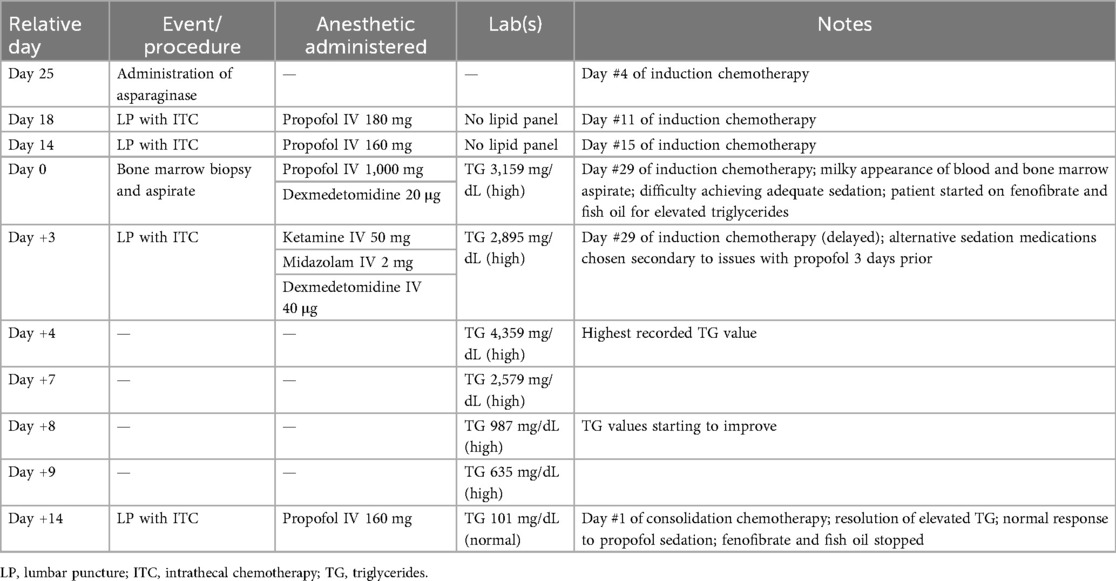

MAC with propofol boluses was planned for this procedure. After routine American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) monitors and a nasal cannula were placed, 180 mg (5 mg/kg) of propofol was injected in divided doses over 3 min via the port-a-cath. The patient did not display any sedation, loss of consciousness, or apnea with this initial propofol administration. Given concern regarding the lack of appropriate response to the propofol administration and despite the port-a-cath having adequate blood return with aspiration, the device was de-accessed and re-accessed by the oncology nurse. A propofol dose of 110 mg (3 mg/kg) was then injected. Again, the patient remained alert and aware without any signs of sedation. The attending anesthesiologist then placed a peripheral IV without difficulty and 210 mg (6 mg/kg) of propofol was administered without any response. A bolus of 8 µg (0.2 µg/kg) of dexmedetomidine was injected followed by 300 mg (8.6 mg/kg) of propofol at which point the patient was asleep, unresponsive, and breathing regularly. The patient received an additional 200 mg (5.4 mg/kg) of propofol and 12 µg (0.3 µg/kg) of dexmedetomidine to complete the procedure. Upon aspiration of the bone marrow by the proceduralist, milky, pink-tinged blood was observed (Figure 1).

The lumbar puncture with intrathecal chemotherapy was deferred to a later date due to the uncertainty of the patient's underlying issue. The patient never became apneic or hypotensive throughout the procedure. A total of 1,000 mg (28 mg/kg) of propofol and 20 µg (0.5 µg/kg) of dexmedetomidine were administered during the encounter. The patient returned to her baseline alert status within 5 min of finishing the procedure.

The patient was hospitalized after her procedure for further monitoring and additional chemotherapy administration. The treating team was concerned about a possible delayed sedative effect or hypotension after the large amount of administered propofol. The patient remained stable with appropriate alertness and normotension in the following 24 h. No complications were noted during this admission.

Her first lipid panel was obtained the evening of her procedure (Day 0 of hypertriglyceridemia diagnosis) and her initial triglyceride value was 3,159 mg/dL. She was started on fish oil and fenofibrate. The trend of her triglycerides in relation to her procedures is outlined in Table 1.

As the lumbar puncture was initially deferred due to her clinical uncertainty, it was completed 3 days later. To avoid administration of large volumes of propofol, and based on the assumption that the hypertriglyceridemia caused the propofol resistance during her prior anesthetic session, she was sedated with 50 mg (1.3 mg/kg) of ketamine, 40 µg (1 µg/kg) of dexmedetomidine, and 2 mg (0.05 mg/kg) of midazolam. The procedure lasted 5 min, and the patient immediately returned to her baseline alert nature at the completion of the procedure. At the time of this procedure her triglyceride level was 2,895 mg/dL. Ultimately, her maximum laboratory values included cholesterol of 861 mg/dL and triglycerides of 4,359 mg/dL.

The patient's triglyceride level normalized 14 days after starting treatment with fenofibrate and fish oil. The patient was scheduled for an additional procedure under anesthesia.

At the time of this procedure, her triglyceride level had normalized to 101 mg/dL. She was subsequently sedated with 160 mg (4.4 mg/kg) of propofol and had an appropriate sedation response to the dose of medication administered.

Discussion

Propofol is a rapid-acting, lipophilic intravenous anesthetic with high lipid solubility. It typically produces sedation at predictable dosages based on weight, and resistance to this drug is typically rare, especially in pediatric patients. This case illustrates transient resistance to propofol in a child diagnosed with ALL, occurring after prior normal responses and resolving after 2 weeks. This suggests a temporary physiological alteration, likely due to hypertriglyceridemia.

Hyperlipidemia, specifically hypertriglyceridemia, is a known side effect in patients treated with asparaginase and glucocorticoids for ALL (1). A similar instance was observed in a 5-year-old boy with ALL who underwent general inhalational anesthesia following chemotherapy with dexamethasone and asparaginase (4). He required twice the typical dose of propofol for sedation and required an inspired concentration of >4% isoflurane to achieve end tidal concentrations of 1.2%–1.5%. The authors observed milky, lipid-rich blood and hypothesized that chemotherapy-induced hyperlipidemia sequestered lipophilic drugs like propofol, reducing their concentrations and CNS availability. Information regarding future anesthetic approaches and hyperlipidemic response for this patient was not provided.

Pegaspargase is a pegylated bacterial L-asparagine amidohydrolase widely used in pediatric ALL protocols due to its prolonged half-life and lower immunogenicity compared to native L-asparaginase. It hydrolyzes extracellular L-asparagine—an amino acid essential for protein synthesis—into aspartate and ammonia. Leukemic lymphoblasts, lacking sufficient asparagine synthetase activity, undergo apoptosis when deprived of this amino acid (5). Notably, our patient received calaspargase pegol, a newer pegylated asparaginase formulation with a longer half-life now commonly being utilized in ALL treatment. Rates of hypertriglyceridemia have been demonstrated to be comparable between the two formulations (6).

Mechanistically, asparaginase inhibits lipoprotein lipase activity and reduces hepatic apolipoprotein synthesis, leading to impaired clearance of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and chylomicrons (7). Simultaneously, concomitant glucocorticoids increase triglyceride synthesis, thus compounding the effect (8). Most hypertriglyceridemia episodes are asymptomatic and transient. However, with severe hypertriglyceridemia, medical interventions have been described, though there is no consensus on optimal management (9). Recurrent hypertriglyceridemia following subsequent asparaginase courses has been documented in case reports. In adults and adolescents, triglyceride elevations often recur—sometimes more rapidly—upon reexposure, though without consistent acute symptoms (5).

The importance of asparaginase in curative pediatric leukemia treatment is well established and prior studies have demonstrated that asparaginase and glucocorticoids may be safely continued under close monitoring, even in the presence of severe but asymptomatic hypertriglyceridemia (10). Management strategies include dietary lipid restriction, pharmacologic interventions, and in extreme cases, insulin, heparin, or plasmapheresis. Dose reductions or discontinuation may be considered only when triglycerides exceed safety thresholds or complications ensue.

Propofol is primarily bound to lipoproteins and albumin in the plasma (3, 11). Thus, the resultant chemotherapy-induced marked increase in circulating lipoproteins, such as VLDL and chylomicrons, provides more binding sites for lipophilic agents like propofol (3, 12). This enhanced lipid binding reduces the amount of unbound propofol available to cross the blood–brain barrier and exert an anesthetic effect (12, 13). As a result, an increased total plasma concentration of propofol is required to achieve adequate free drug levels, which manifests clinically as drug resistance (4, 12). In our patient, severe hypertriglyceridemia likely reduced the fraction of free propofol available through this mechanism, and the return of an expected anesthetic response following lipid normalization further supports this pharmacokinetic relationship.

In 2016, a separate case of propofol resistance was reported in a 38-year-old man with major depressive disorder, severe hypertriglyceridemia, and diabetes undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. He displayed resistance to propofol and methohexital, which was only overcome with the addition of sevoflurane. The authors suggested a “lipid sink” model where excessive circulating lipids absorbed lipophilic drugs, thereby reducing the free drug available to cross the blood–brain barrier (12).

These mechanisms are supported by other clinical studies. In one trial, hyperlipidemic patients were found to have significantly lower unbound propofol concentrations in comparison to healthy controls, demonstrating a positive correlation between serum cholesterol/ triglyceride levels and propofol binding (3). Similarly, another study demonstrated that lipoprotein levels can predict the amount of propofol binding, providing an explanation for individual variability in anesthetic responses (13).

To further highlight the abnormal response our patient exhibited to standard propofol dosing, one study investigated the doses of propofol required to achieve loss of consciousness—measured by loss of eyelash reflex (LOER)—and apnea in children aged 3–18 years (14). It found that the mean propofol dose to achieve LOER was 2.65 mg/kg and the mean propofol dose to achieve apnea was 6.82 mg/kg. The time to apnea was also significantly affected by age and sex, with both older children and girls requiring lower doses to reach the desired endpoint. When comparing the mean dosage needed to achieve LOER in the previous study to this case, our patient received approximately 10 times the standard dose before the same level of sedation was achieved. She also never experienced apnea, which would have been expected to occur at a lower dose based on the prior study results.

While the temporal relationship strongly suggests that hypertriglyceridemia was the driving factor for propofol resistance with our patient, one limitation in this case report is that different anesthetic medications were utilized in the interim while awaiting the normalization of lipid levels. Therefore, it is unclear if there would have been a similar response to propofol if lipid levels were to increase again. It should also be noted that relatively higher doses of these anesthetic medications (ketamine, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam) were required during her Day 3 lumbar puncture, yet she demonstrated a rapid return to baseline, indicating that the pharmacokinetics of these medications may have been altered in the setting of dyslipidemia like propofol. In addition, it is assumed that all other patient factors aside from lipid levels remained constant throughout the timeline.

The association between the patient's altered anesthetic response, her chemotherapy regimen, the milky appearance of her blood and bone marrow aspirates, and her return to baseline propofol requirements collectively supports a transient chemotherapy-induced hyperlipidemic state as the cause. The multiple, consecutive anesthetics administered in this case clearly demonstrate a correlation between hypertriglyceridemia and propofol resistance. The patient demonstrated normal propofol responses at the beginning and end but experienced a temporary abnormal response while in a concurrent hyperlipidemic state. This case highlights the need for increased awareness among anesthesiologists and oncologists regarding the potential for transient hyperlipidemic states and an altered outcome with anesthetics. In such scenarios, alternative drugs or adjunctive agents may be needed to achieve sedation and minimize the potential for drug toxicity.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

BR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AE: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Steinherz PG. Transient, severe hyperlipidemia in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with prednisone and asparaginase. Cancer. (1994) 74(12):3234–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941215)74:12%3C3234::AID-CNCR2820741224%3E3.0.CO;2-1

2. Tozuka M, Yamauchi K, Hidaka H, Nakabayashi T, Okumura N, Katsuyama T. Characterization of hypertriglyceridemia induced by L-asparaginase therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and malignant lymphoma. Ann Clin Lab Sci. (1997) 27(5):351–7.9303174

3. Zamacona MK, Suárez E, García E, Aguirre C, Calvo R. The significance of lipoproteins in serum binding variations of propofol. Anesth Analg. (1998) 87(5):1147–51. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199811000-00032

4. Moore J, Smith JH. A case of resistance to anesthesia secondary to severe hyperlipidemia. Paediatr Anaesth. (2007) 17(12):1223–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02342.x

5. Galindo RJ, Yoon J, Devoe C, Myers AK. PEG-asparaginase induced severe hypertriglyceridemia. Arch Endocrinol Metab. (2016) 60(2):173–7. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000068

6. Kang J, Kanukollu S, Bevinetto A, Corless R, Redner A. Comparing tolerability and toxicity of calaspargase-pegol and pegaspargase in pediatric leukemia patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2025) 47:e305–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000003098

7. Hoogerbrugge N, Jansen H, Hoogerbrugge PM. Transient hyperlipidemia during treatment of ALL with L-asparaginase is related to decreased lipoprotein lipase activity. Leukemia. (1997) 11(8):1377–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400703

8. Finch ER, Smith CA, Yang W, Liu Y, Kornegay NM, Panetta JC, et al. Asparaginase formulation impacts hypertriglyceridemia during therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67(1):e28040. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28040

9. Juluri KR, Siu C, Cassaday RD. Asparaginase in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: current evidence and place in therapy. Blood Lymphat Cancer. (2022) 12:55–79. doi: 10.2147/BLCTT.S342052

10. Bhojwani D, Darbandi R, Pei D, Ramsey LB, Chemaitilly W, Sandlund JT, et al. Severe hypertriglyceridaemia during therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur J Cancer. (2014) 50(15):2685–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.023

11. Schicher M, Polsinger M, Hermetter A, Prassl R, Zimmer A. In vitro release of propofol and binding capacity with regard to plasma constituents. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. (2008) 70(3):882–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.06.018

12. Johnson TJ, Porhomayon J, Nader ND, Eldesouki E, Smith K, Hobika GG. Hyperlipidemia sink for anesthetic agents. J Clin Anesth. (2016) 34:436–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.05.022

13. de la Fuente L, Lukas JC, Vázquez JA, Jauregizar N, Calvo R, Suárez E. ‘In vitro’ binding of propofol to serum lipoproteins in thyroid dysfunction. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2002) 58(9):615–9. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0520-z

Keywords: propofol, leukemia, hypertriglyceridemia, sedation, lipid

Citation: Rovner B, Greenlaw S, Ferrante C, Eason AC, Heine C and McCoy NC (2025) Reversible propofol resistance in a pediatric patient with chemotherapy-induced hypertriglyceridemia: a case report. Front. Anesthesiol. 4:1726004. doi: 10.3389/fanes.2025.1726004

Received: 15 October 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Accepted: 14 November 2025;

Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Rene Buchet, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, FranceReviewed by:

Luis Laranjeira, Ordem dos Médicos, PortugalBilal Kazi, P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre, India

Aspari Mahammad Azeez, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Copyright: © 2025 Rovner, Greenlaw, Ferrante, Eason, Heine and McCoy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole C. McCoy, bWNjb3luQG11c2MuZWR1

Brooke Rovner

Brooke Rovner Sydney Greenlaw2

Sydney Greenlaw2 Christopher Heine

Christopher Heine Nicole C. McCoy

Nicole C. McCoy