- 1Clinical Department for Small Animals and Horses, Division of Small Animal Internal Medicine, Univesity of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Austria

- 2Instituto de Investigaciones en Salud (INISA), Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica

- 3Small Animal Internal Medicine, Clinic for Small Animals, Veterinärmedizinische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria

- 4Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Jose, Costa Rica

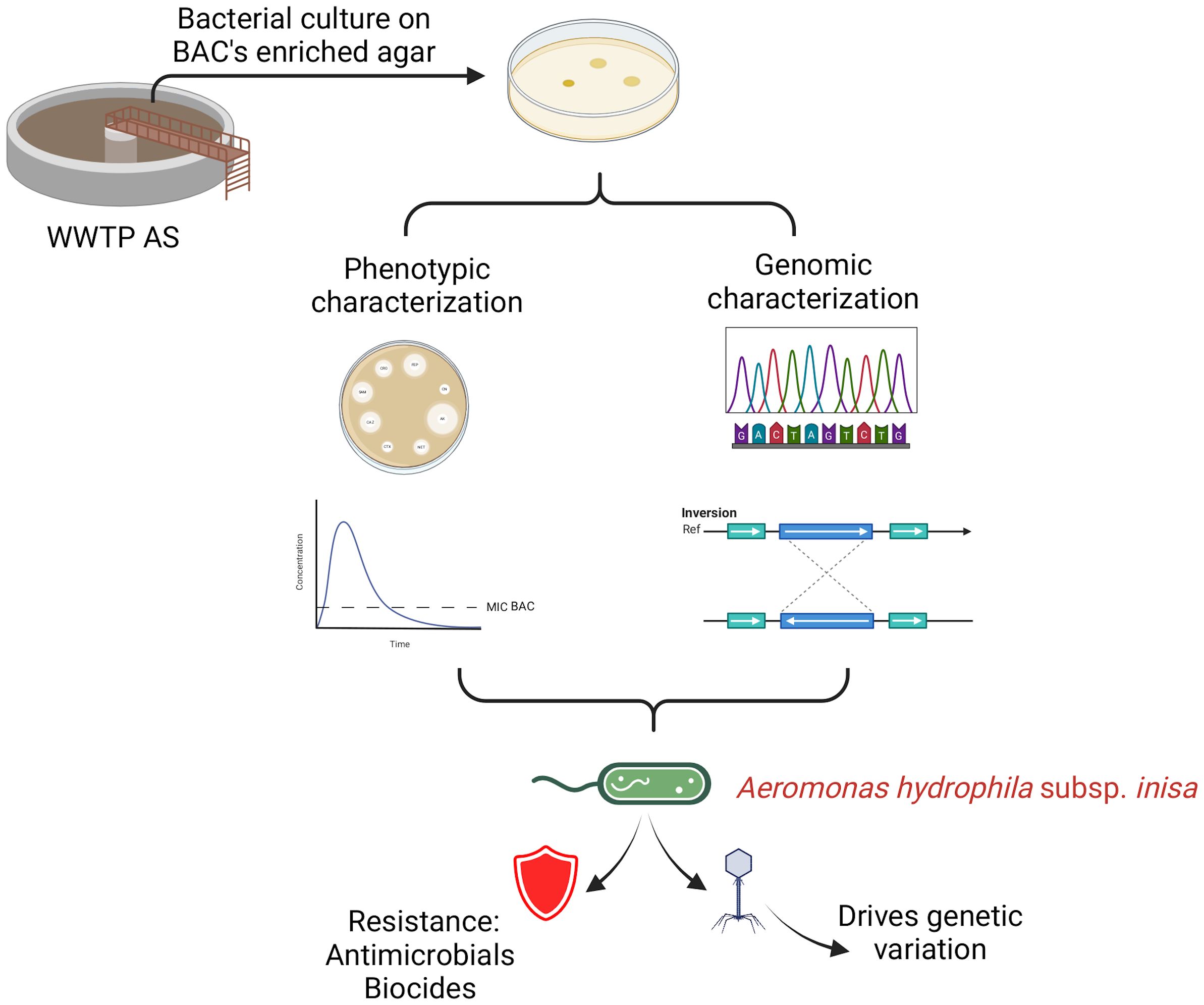

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) serve as hotspots for the proliferation and evolution of specialized microorganisms. Among these, Aeromonas hydrophila stands out as a bacterium capable of colonizing diverse aquatic ecosystems. Its resistance to disinfectants, such as benzalkonium chloride (BAC), is particularly concerning in wastewater treatment systems, where such traits can be propagated. Here, we present a genomic characterization of three isolates belonging to a newly identified subspecies, A. hydrophila subsp. inisa, based on comprehensive genomic analyses. These isolates exhibited higher levels of BAC resistance compared to the reference strain ATCC 7966/DSM 3017 (EC50–27 mg/L vs. 24 mg/L) and contained several prophage sequences integrated into their genomes. These prophages were associated with genetic rearrangements, which may underline phenotypic changes, such as increased antimicrobial resistance. Notably, A. hydrophila subsp. inisa 10 exhibited greater genetic rearrangements and resistance to multiple antibiotics, traits not observed in the other isolates. This study provides the first description of a phage-associated A. hydrophila subspecies isolated from a wastewater system in Central America, underscoring the role of bacteriophages in driving bacterial evolution, speciation, and adaptation to highly polluted environments, such as WWTPs.

1 Introduction

Emerging contaminants are frequently detected at elevated concentrations in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Many of these contaminants exhibit high affinity for treatment by-products, such as sludge, where they accumulate at concentrations ranging from micrograms to milligrams per liter (μg/L to mg/L) (Alderton et al., 2021). Activated sludge in WWTPs functions as a bioreactor, facilitating the assembly and transfer of genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance (Gillings and Stokes, 2012) and exerting selective pressure due to the simultaneous presence of several antimicrobial compounds, including antibiotics, heavy metals, biocides, and pharmaceuticals (Chukwu et al., 2023).

Benzalkonium chloride (BAC), a widely used quaternary ammonium compound, is one such biocide commonly employed in domestic and industrial settings (Mohapatra et al., 2023). Its extensive use has raised concerns about its role in promoting antimicrobial resistance, as it exerts selective pressure on microbial communities in wastewater environments, leading to changes in taxonomic composition and antimicrobial resistance or tolerance profiles (Tandukar et al., 2013; Chacón et al., 2021; Chacon et al., 2023).

Among the microorganisms that persist and adapt under such selective pressures, Aeromonas hydrophila, a Gram-negative bacillus, stands out as a relevant model due to its ability to colonize diverse aquatic ecosystems and contaminated environments, including WWTP. Its presence in polluted environments, particularly wastewater, has been linked to the development of resistance to biocides and antimicrobial agents (Igbinosa and Okoh, 2012; Fernández-Bravo and Figueras, 2020; Govender et al., 2021).

Pangenome analyses of the Aeromonas genus have revealed that A. hydrophila exhibits a relatively low core-genome:pan-genome ratio (0.38), consistent with a highly variable and diverse genome compared to other Aeromonas species (Ghatak et al., 2016). This genomic variability suggests that A. hydrophila possesses greater pathogenic potential and antimicrobial resistance, highlighting its importance as a model organism for studying resistance mechanisms (Ghatak et al., 2016), more specifically in environmental samples.

WWTPs, under selective pressure from biocides, heavy metals, and antibiotics, may drive the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant bacterial strains with genomic plasticity. In this context, this study aimed to characterize BAC-tolerant A. hydrophila isolates obtained from activated sludge and to explore the genomic and phage-associated features potentially underlying their antimicrobial resistance profile and adaptive evolution. Our results show resistance to multiple antibiotics and genomic rearrangements, including prophage integrations, suggesting adaptive evolution. This study underscores WWTPs as reservoirs and accelerators of microbial adaptation, emphasizing the need to understand these mechanisms to tackle antimicrobial resistance in polluted environments.

2 Methodology

2.1 Bacteria isolation and antimicrobial resistance profile

Aeromonas hydrophila isolates (INISA09, INISA10, and INISA16) were obtained from BAC-exposed activated sludge collected in the Costa Rican Central Valley (9°55′14″N, 84°14′34″W). As described by Chacón et al. (Chacón et al., 2021), activated sludge samples were aerated and enriched with 10 mg/L of BAC for 96h at 20°C under aerobic conditions. The isolates were recovered on trypticase soy agar (TSA; Oxoid®, United States) supplemented with 25 mg/L of BAC.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed following the recommendations of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 2024). The antibiotic resistance profile was evaluated by the disk diffusion method using antibiotic disks (Oxoid®, United States) and Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid®, United States). The antibiotics tested included aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, meropenem, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, ceftazidime, and cefepime. Inhibition zone diameters were measured in millimeters after 18 ± 2h of incubation at 35 ± 1°C.

2.2 Half-maximal effective concentration at BAC

A bacterial inoculum of 106 colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/ml) was prepared to determine the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50). The inoculum density was standardized using a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard, corresponding to approximately 1 × 108 CFU/ml, and subsequently adjusted by dilution to reach 106 CFU/ml. The EC50 was determined using a modified version of the broth microdilution method described by Andrews (Andrews, 2001). It was defined as the lowest concentration of BAC that inhibited 50% of visible growth in the liquid culture. The BAC (Fluka® Analytical, Germany) concentrations tested ranged from 1 μg/ml to 128.0 μg/ml. Seven replicates were performed for each concentration. Additionally, one well was used as a blank for BAC + LB medium turbidity, seven wells served as growth controls (without BAC), and seven wells were used to control for LB medium turbidity. Absorbance values were measured at 620 nm using a spectrophotometer Multiskan Ex (Thermo, USA) after 24h of incubation. The absorbance data were then analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2019) version 4.4.1 and the drc package to estimate the EC50 for each bacterial strain (Ritz and Streibig, 2022).

2.3 Phylogenomics and comparative genomics analysis

DNA extraction was conducted with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq platform provided by Novogene (Hong Kong, China). Sequencing data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) under BioProject PRJNA1183447.

We processed raw sequencing data using fastp (Chen et al., 2018) with default parameters. The resulting high-quality Illumina reads were assembled with SPAdes v3.15.4 (Bankevich et al., 2012) using k-mer values of 21, 33, 55, and 77. Contigs shorter than 1000 bp were removed, and assembly statistics (genome size, N50, L50, among others) were generated using Quast v5.3 (Mikheenko et al., 2023). The completeness and contamination of assembled genomes were assessed with CheckM2 (Parks et al., 2015).

To identify related species to our isolates, we initially used the Type Strain Taxonomy Server (TYGS) (Meier-Kolthoff and Göker, 2019) for whole-genome comparisons based on digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH). However, due to the low dDDH values observed for our Aeromonas genomes, we employed an in-house pipeline to conduct further genomic analysis. The GenFlow pipeline (https://github.com/braddmg/GenFlow) download reference genomes from the NCBI database, extracts and concatenates nucleotide sequences of all Single Copy Core Genes (SCCGs) shared across genomes, and applies a geometric and functional index threshold of 0.8, an mcl value of 10, and a minbit heuristic value of 0.5. The concatenated SCCGs are aligned, and a phylogenomic tree is generated using FastTree (21) with the General Time Reversible (GTR) model and 1000 bootstrap resampling. The full protocol is available in protocols.io (Mendoza, 2024).

For reference genome selection, we included two genomes from each previously reported Aeromonas species, prioritizing type strains whenever available (Fernández-Bravo and Figueras, 2020), resulting in a total of 31 species (Fernández-Bravo and Figueras, 2020). In cases where only a single genome was available for certain species, that genome was selected. Additionally, we included various strains and subspecies of Aeromonas hydrophila to clarify the relationship between our isolates and this species. The genome of Escherichia coli K12 MG1655 was used as an outgroup (Supplementary File, Table 1).

We aligned and scaffolded the assembled contigs of each isolate against the type strain A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 using the Reverse Complement and Concatenate Contigs in Order (ReCCO) method (Nishimura et al., 2024). The resulting alignment was visualized with the Python package pyGenomeViz (Shimoyama, 2024), utilizing progressive Mauve for alignment. Finally, we annotated the aligned genomes with Prokka (Cantalapiedra et al., 2021) using default parameters (e-value threshold of 10−6) (Supplementary File, Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5).

2.4 Antibiotic resistance, biocide resistance, plasmid, and phage annotation

To identify antibiotic and biocide resistance genes, we used the ABRicate v1.0.1 (Seemann, 2020) tool with the AMRFinder NCBI database updated on 2024-10-29 (Feldgarden et al., 2019) and the BacMet v2.0 (Pal et al., 2014) database, selecting genes with at least 90% identity and coverage. For phage-related sequence identification, we uploaded the genome sequences to the PHASTEST web portal (Arndt et al., 2019). Additionally, we extracted the phage regions of each genome based on the start and end coordinates identified by PHASTEST using Bedtools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) and subsequently uploaded them to the PhageScope web portal for further annotation and visualization (Wang et al., 2024). Finally, Mob-suite was employed for plasmid identification with default parameters (Robertson and Nash, 2018).

3 Results

We identified three strains of A. hydrophila and classified them as a new subspecies denominated inisa. The genomes of these strains exhibited high completeness (100%) and low contamination (0.34%) according to CheckM2. The genome size was 4.71 Mb for inisa09 and 4.78 Mb for inisa10 and inisa16, with N50 values ranging from 29 to 32 and L50 values from 4 to 7 (Table 1). These strains exhibited higher resistance to BAC and other antibiotics compared to the ATCC 7966/DSM 3017 reference strain. Despite their similar genome size (4.74–4.78 mb) and GC content (61.25%–61.32%), inisa strains show genetic rearrangements potentially associated with prophage insertions absent in the reference strain. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization values for all strains fell below the 70% threshold proposed for species delimitation compared to the reference strain (Table 1). The Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) for all isolates was 96.4% when compared to the reference strain, which is within the 95%–96% threshold commonly used for species delineation.

Table 1. Genomic and phenotypic characteristics of Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa isolates and reference strain ATCC 7966.

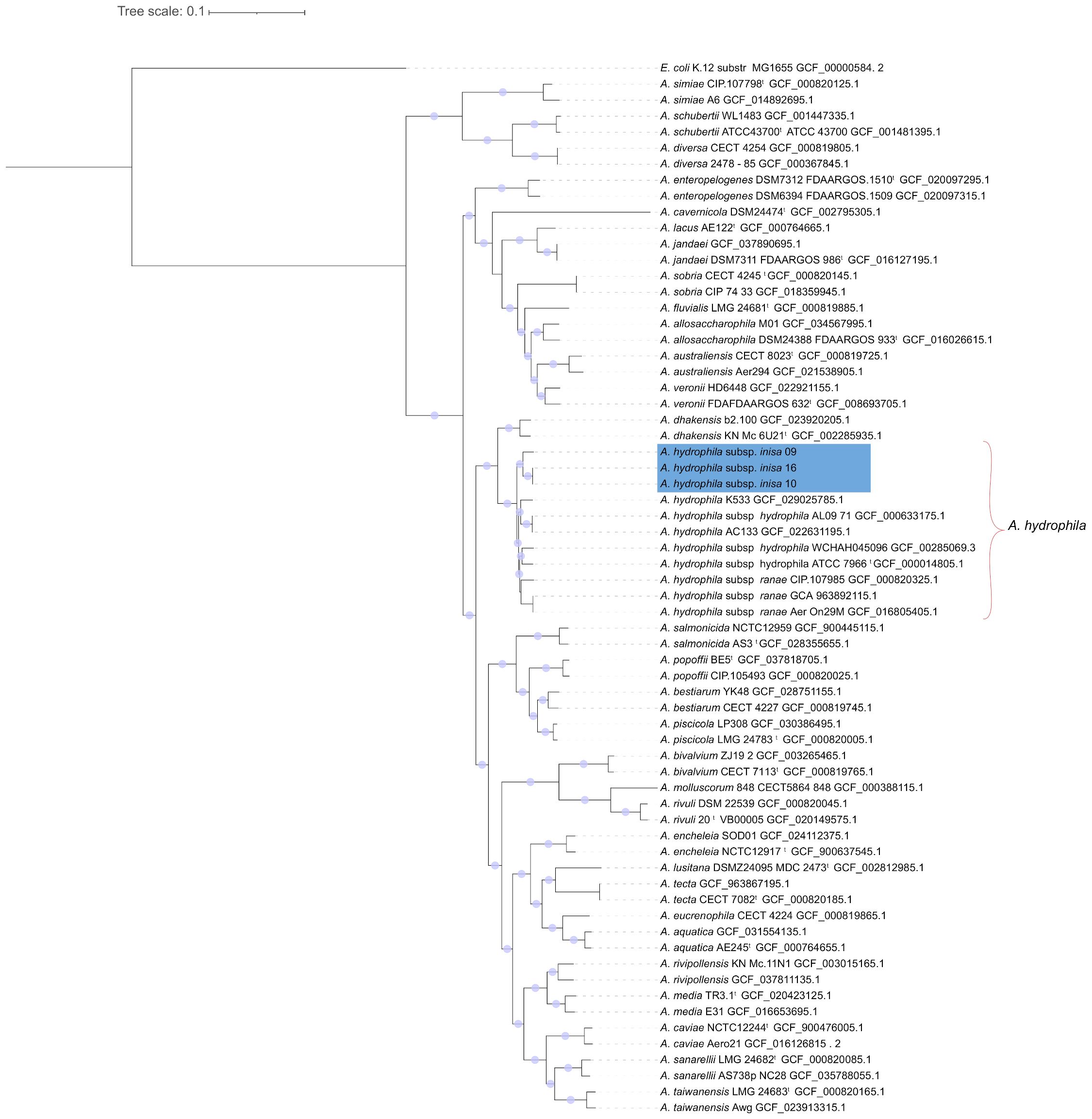

The EUCAST ECOFF 2024 does not include any isolates with inhibition zones as small as the one observed, supporting its classification as resistant (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), 2024). Phylogenomic analysis revealed that these isolates share a recent common ancestor with other A. hydrophila strains (Figure 1) but form a different subclade, separate from the recognized subspecies A. hydrophila subsp. ranae and A. hydrophila subsp. hydrophila, with strong bootstrap support (100%). Based on these genomic distinctions, we propose that inisa09, inisa10, and inisa16 represent a new subspecies of Aeromonas hydrophila, hereby referred to as Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa.

Figure 1. Phylogenomic tree of Aeromonas species. The tree was constructed using 611 single-copy core genes shared across all genomes and with the genome of Escherichia coli K12 MG1655 as outgroup. Bootstrap values of 100% are represented as circular shapes at the nodes. Aeromonas hydrophila genomes are highlighted with a red bracket and Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa genomes are marked in a blue.

The three isolates of Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa presented genomic rearrangements in comparison with the type strain (Figure 2). Although most of the genome appears stable, multiple translocation and inversion events were observed, especially in the region spanning 2 Mb to 3 Mb in the three isolates relative to the A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 reference genome. Notably, A. hydrophila subsp. inisa10 exhibited the most extensive alteration, characterized by a complete inversion spanning 2.3–2.87 Mb (~11.9% of the genome). This region contains 480 CDS, representing ~11.1% of all annotated CDS (Supplementary File, Table 4). Additionally, strains inisa10 and inisa16 exhibited insertions of three phage regions associated with phages ArgO145, ST15, and SfIV. According to PHASTEST, ST15 and SfIV were classified as intact, with scores of 150 and 100, respectively (out of 150), indicating that most predicted phage CDS are present. In contrast, ArgO145 received a score of 90 and was classified as questionable. In strain inisa09, a fourth phage region associated with Salmonella phage 118970 was identified and classified as intact with a score of 150. All detected phages belong to the Caudoviricetes class. The recovered structure of these phages can be seen in Figure 3. We did not find any prophage sequence in the genome of reference strain A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 using PHASTEST (Figure 2), which is consistent with previous reports (Awan et al., 2018). In addition, none of the analyzed strains showed evidence of plasmids according to MOB-suite.

Figure 2. Genomic alignment map of three Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa genomes against the reference genome of the type strain Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. hydrophila ATCC 7966. Gray lines indicate conserved genomic regions across all genomes, while red lines and downward-pointing bars indicate inverted regions. The regions containing the phage sequences are highlighted delimitated with asterisks (*).

Figure 3. Recovered phage structures identified in the Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa genomes. The figure shows the phage regions associated with ArgO145, ST15, SfIV, and Salmonella phage 118970 as predicted by PHASTEST web portal (Arndt et al., 2019).

We identified three ARG families across all analyzed genomes, each represented by multiple gene variants (Table 1). These genes included variants of blaOXA, cep, and imi genes, which are associated with resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics (Table 1). However, the antimicrobial susceptibility tests revealed that only the inisa10 exhibited intermediate resistance to aztreonam and a markedly reduced inhibition zone to meropenem, consistent with a potential resistance phenotype, although no specific EUCAST cutoff value is available for this observation (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), 2024). Additionally, the inisa10 strain showed resistance to ciprofloxacin, while inisa09 presented an intermediate resistance phenotype to this antibiotic. We also identified genes annotated as potentially associated with biocide-related resistance, most of which encode membrane-related proteins, including ompD, gadC, and fpvA (Table 1).

4 Discussion

In this study, we propose a new subspecies of Aeromonas hydrophila based on the genomic characterization of three strains, together with their antibiotic and BAC resistance phenotypes. Genomic comparisons revealed dDDH values slightly below the established 70% threshold for species delimitation. However, since these genomes are draft assemblies generated exclusively from Illumina short reads, and the values fall very close to the cutoff (between 69% and 70%), we consider a cautious taxonomic interpretation appropriate. Following the recommendations of Meier-Kolthoff et al (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2014), who suggested a dDDH threshold of 79%–80% as the most robust boundary for subspecies delineation across E. coli and more than 100 other bacterial genera, our isolates are best classified as a potential new subspecies of A. hydrophila.

Similarly, the isolates share 96.4% of ANI with the type strain (30). However, Awan et al. (Awan et al., 2018). reported that different A. hydrophila strains can exhibit ANI values below 97% when compared to the type strain, demonstrating that this species shows considerable genomic diversity. A key limitation of relying solely on ANI and dDDH for species delimitation is that these measures are primarily based on comparisons to the type strain, which may not adequately represent the full genomic variability and sublineages present within a species. Indeed, genome pairs with intermediate ANI values (e.g., 85%–95%) are commonly found within well-recognized species, indicating that nominal thresholds may not be universally applicable across all bacterial lineages (Jain et al., 2018; Parks et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2021). Additionally, the phylogenomic tree shows that the three isolates form a distinct branch, strongly supported by bootstrap analysis. Taken together, we suggest the classification of these isolates as a subspecies of A. hydrophila.

A. hydrophila subsp. inisa10 displayed resistance to the highest number of antibiotics, while inisa16, despite sharing 100% ANI with isolate 10, was susceptible to all antibiotics tested. Both isolates contain the same ARG variants (Table 1), with others from the same families also present in inisa09 and the type strain. Interestingly, genomic comparisons revealed that isolate inisa10 harbors a complete inversion spanning 2.3 Mb to 2.87 Mb, while inisa16 and inisa09 only exhibit partial inversions in the flanking regions (Figure 2). These prophage-mediated rearrangements, which are key drivers of genomic reorganization (Darmon and Leach, 2014), contain genes encoding multidrug transporters such as mdtL2, norM2, mdlB, and yheI (Supplementary File, Table 6), which have been previously associated with multidrug resistance (Sulavik et al., 2001; Fehlner-Gardiner and Valvano, 2002; Li et al., 2023). These findings suggest that such genomic rearrangements, possibly facilitated by prophages, could influence the expression or regulation of antimicrobial resistance genes, potentially enhancing phenotypic resistance under selective pressures.

While most phage-associated genes were either uncharacterized or linked to phage structure, several genes were annotated as encoding proteins capable of affecting DNA structure and promoting genomic rearrangements, such as endo- and exonucleases (Darmon and Leach, 2014), as well as resolvases (Sharples, 2001; Kobryn and Chaconas, 2014). According to the gene classification summarized in Supplementary File, Tables 6 and 7, structural proteins accounted for 18%–38% of the predicted ORFs, while 35%–48% were annotated as hypothetical or unknown. The remaining genes (17–47%) were associated with regulatory or host-related functions, highlighting differences in functional annotation depth among the four phages analyzed. Specifically, we identified an exonuclease C-terminal domain protein in phage SfIV, as well as a 3′ exoribonuclease RNase, an HNH endonuclease, and Holliday junction resolvases in both phage SfIV and Salmonella phage 118970 (Figure 3). Notably, phage exonucleases have been reported to play a critical role in bacterial DNA recombination (37), highlighting the significance of prophages in bacterial genome remodeling (Menouni et al., 2015). Similarly, resolvases are known to induce genomic rearrangements through recombination events and are frequently observed in phage sequences (Kobryn and Chaconas, 2014). Recent reviews further emphasize the underestimated ecological and functional roles of phages in complex biological systems, where they not only mediate horizontal gene transfer but also drive microbial community dynamics, metabolic adaptability, and evolutionary processes within wastewater environments (Huang et al., 2025).

The persistence of BAC-tolerant A. hydrophila in WWTPs poses potential public health concerns, as it may reduce the efficacy of quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) commonly used in domestic, hospital, and food industry settings. Comparable cases of A. hydrophila with low susceptibility or metabolic adaptation to BAC are scarce (Patrauchan and Oriel, 2003; Stratev and Vashin, 2014), highlighting the importance of including this aquatic bacterial model to better understand the development of tolerance and adaptive responses to biocides in aquatic ecosystems. The presence of prophage sequences in these isolates suggests a possible role of phages in mediating genome rearrangements and, potentially, the horizontal transfer of resistance determinants. In addition to prophages, other mobile genetic elements, including plasmids, transposons, insertion sequences, and integrons, have been shown to mediate the dissemination of antimicrobial, metal, and biocide resistance genes under selective pressure in aquatic and wastewater environments (Mohapatra et al., 2023). These observations emphasize the need for continued surveillance of QAC tolerance and mobile genetic elements in wastewater environments, where adaptive mechanisms may compromise biocide efficacy and facilitate the dissemination of resistance genes, underscoring the relevance of integrative monitoring approaches that link microbial ecology, public health, and biocide use practices.

Nevertheless, additional experiments are required to define the role of these prophages in driving adaptive traits such as antibiotic and biocide resistance and in promoting bacterial speciation. For example, in the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii, infection by phage φAbp1 downregulates virulence genes and upregulates drug-resistance genes, based on RNA-seq and RT-qPCR validation, showing that phages can alter host resistance profiles (https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00068-19). Future work should isolate the different A. hydrophila phages infect the phage-free reference strain A. hydrophila ATCC 7966, and test for genome rearrangements (using long-read sequencing) and changes in drug-resistance expression using transcriptomic and RT-qPCR assays.

Although this work was based on a limited number of isolates, it provides valuable genomic and phenotypic evidence of phage-associated variability in A. hydrophila. The isolates originated from a single WWTP, which restricts the geographic extrapolation of the results. While genomic and phenotypic observations were consistent with increased tolerance, additional molecular assays would be required to confirm the specific contribution of prophage-associated genes to the observed tolerance and resistance traits. Future studies should include isolates from multiple wastewater systems and integrate transcriptomic or proteomic analyses to clarify the mechanisms underlying these adaptive responses. Ultimately, these findings underscore the importance of studying prophage and genome rearrangement dynamics in understanding bacterial evolution, antimicrobial resistance, and adaptation in polluted environments.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA1183447.

Author contributions

LC: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Funding acquisition. BM-G: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. AR-R: Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization. KR-J: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Project B7255, funded by the Vicerrectoría de Inves gación of the Universidad de Costa Rica.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the clarity and readability of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbrio.2025.1709187/full#supplementary-material

References

Alderton I., Palmer B. R., Heinemann J. A., Pattis I., Weaver L., Gutiérrez-Ginés M. J., et al. (2021). The role of emerging organic contaminants in the development of antimicrobial resistance. Emerg. Contam 7, 160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.emcon.2021.07.001

Andrews J. M. (2001). Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 48, 5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5

Arndt D., Marcu A., Liang Y., and Wishart D. S. (2019). PHAST, PHASTER and PHASTEST: Tools for finding prophage in bacterial genomes. Brief Bioinform. 20, 1560–1567. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx121

Awan F., Dong Y., Liu J., Wang N., Mushtaq M. H., Lu C., et al. (2018). Comparative genome analysis provides deep insights into Aeromonas hydrophila taxonomy and virulence-related factors. BMC Genomics 19, 712. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5100-4

Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021

Cantalapiedra C. P., Hernández-Plaza A., Letunic I., Bork P., and Huerta-Cepas J. (2021). eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab293

Chacón L., Arias-Andres M., Mena F., Rivera L., Hernández L., Achi R., et al. (2021). Short-term exposure to benzalkonium chloride in bacteria from activated sludge alters the community diversity and the antibiotic resistance profile. J. Water Health 19, 895–906. doi: 10.2166/wh.2021.171

Chacon L., Rojas-Jimenez K., and Arias-Andres M. (2023). Bacterial communities in residential wastewater treatment plants are physiologically adapted to high concentrations of quaternary ammonium compounds. Clean (Weinh) 51, 2300056. doi: 10.1002/clen.202300056

Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., and Gu J. (2018). fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Chukwu K. B., Abafe O. A., Amoako D. G., Essack S. Y., and Abia A. L. K. (2023). Antibiotic, heavy metal, and biocide concentrations in a wastewater treatment plant and its receiving water body exceed PNEC limits: potential for antimicrobial resistance selective pressure. Antibiotics 12, 1166. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12071166

Darmon E. and Leach D. R. F. (2014). Bacterial genome instability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 78, 1–39. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00035-13

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (2024). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Available online at: https://mic.eucast.org/search/?search%5Bmethod%5D=diff&search%5Bantibiotic%5D=-1&search%5Bspecies%5D=31&search%5Bdisk_content%5D=4&search%5Blimit%5D=50 (Accessed November 11, 2024).

Fehlner-Gardiner C. C. and Valvano M. A. (2002). Cloning and characterization of the Burkholderia Vietnamiensis norM gene encoding a multi-drug efflux protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215, 279–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11403.x

Feldgarden M., Brover V., Haft D. H., Prasad A. B., Slotta D. J., Tolstoy I., et al. (2019). Validating the AMRFinder tool and resistance gene database by using antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations in a collection of isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00483-19

Fernández-Bravo A. and Figueras M. J. (2020). An update on the genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, epidemiology, and pathogenicity. Microorganisms 8, 129. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8010129

Ghatak S., Blom J., Das S., Sanjukta R., Puro K., Mawlong M., et al. (2016). Pan-genome analysis of Aeromonas hydrophila, Aeromonas veronii and Aeromonas caviae indicates phylogenomic diversity and greater pathogenic potential for Aeromonas hydrophila. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 109, 945–956. doi: 10.1007/s10482-016-0693-6

Gillings M. R. and Stokes H. W. (2012). Are humans increasing bacterial evolvability? Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.02.006

Govender R., Amoah I. D., Adegoke A. A., Singh G., Kumari S., Swalaha F. M., et al. (2021). Identification, antibiotic resistance, and virulence profiling of Aeromonas and Pseudomonas species from wastewater and surface water. Environ. Monit Assess. 193, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10661-021-09046-6

Huang W., Wang F., Su Y., Huang H., and Luo J. (2025). Underestimated roles of phages in biological wastewater treatment systems: Recent advances and challenges. J. Hazard Mater 495, 139007. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.139007

Igbinosa I. H. and Okoh A. I. (2012). Antibiotic susceptibility profile of Aeromonas species isolated from wastewater treatment plant. Sci. World J. 2012, 1–6. doi: 10.1100/2012/764563

Jain C., Rodriguez-R L. M., Phillippy A. M., Konstantinidis K. T., and Aluru S. (2018). High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9

Kobryn K. and Chaconas G. (2014). Hairpin telomere resolvases. Microbiol. Spectr. 2. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0023-2014

Li X., Shang B., Zhang X., Zhang H., Li Z., Shen X., et al. (2023). Complete genome sequence data of multidrug-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila Ah27 isolated from intussusception channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Gene Rep. 33, 101807. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2023.101807

Meier-Kolthoff J. P. and Göker M. (2019). TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 10, 2182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10210-3

Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Hahnke R. L., Petersen J., Scheuner C., Michael V., Fiebig A., et al. (2014). Complete genome sequence of DSM 30083T, the type strain (U5/41T) of Escherichia coli, and a proposal for delineating subspecies in microbial taxonomy. Stand Genomic Sci. 9, 2. doi: 10.1186/1944-3277-9-2

Mendoza B. (2024). GenFlow: A bioinformatic workflow for phyloGenomic analysis v1. doi: 10.17504/protocols.io.14egn6kepl5d/v1

Menouni R., Hutinet G., Petit M.-A., and Ansaldi M. (2015). Bacterial genome remodeling through bacteriophage recombination. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 362, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnu022

Mikheenko A., Saveliev V., Hirsch P., and Gurevich A. (2023). WebQUAST: online evaluation of genome assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W601–W606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad406

Mohapatra S., Yutao L., Goh S. G., Ng C., Luhua Y., Tran N. H., et al. (2023). Quaternary ammonium compounds of emerging concern: Classification, occurrence, fate, toxicity and antimicrobial resistance. J. Hazard Mater 445, 130393. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.130393

Murray C. S., Gao Y., and Wu M. (2021). Re-evaluating the evidence for a universal genetic boundary among microbial species. Nat. Commun. 12, 4059. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24128-2

Nishimura Y., Yamada K., Okazaki Y., and Ogata H. (2024). DiGAlign: versatile and interactive visualization of sequence alignment for comparative genomics. Microbes Environ. 39, ME23061. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME23061

Pal C., Bengtsson-Palme J., Rensing C., Kristiansson E., and Larsson D. G. J. (2014). BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D737–D743. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1252

Parks D. H., ChuvoChina M., Chaumeil P.-A., Rinke C., Mussig A. J., and Hugenholtz P. (2020). A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0501-8

Parks D. H., Imelfort M., Skennerton C. T., Hugenholtz P., and Tyson G. W. (2015). CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114

Patrauchan M. A. and Oriel P. J. (2003). Degradation of benzyldimethylalkylammonium chloride by Aeromonas hydrophila sp. K. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94, 266–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01829.x

Quinlan A. R. and Hall I. M. (2010). BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033

R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available online at: https://www.r-project.org/ (Accessed November 11, 2024).

Ritz C. and Streibig J. C. (2022). Package’drc. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/drc/drc.pdf (Accessed October 30, 2025).

Robertson J. and Nash J. H. E. (2018). MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom 4. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000206

Seemann T. (2020). ABRRicate. Available online at: https://github.com/tseemann/abricate/blob/master/README.md (Accessed October 30, 2025).

Sharples G. J. (2001). The X philes: structure-specific endonucleases that resolve Holliday junctions. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 823–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02284.x

Shimoyama Y. (2024). pyGenomeViz: A genome visualization python package for comparative genomics. Available online at: https://github.com/moshi4/pyGenomeViz (Accessed October 30, 2025).

Stratev D. and Vashin I. (2014). Aeromonas hydrophila sensitivity to disinfectants. J. Fishscicom 8, 324–330. doi: 10.3153/jfscom.201439

Sulavik M. C., Houseweart C., Cramer C., Jiwani N., Murgolo N., Greene J., et al. (2001). Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1126–1136. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1126-1136.2001

Tandukar M., Oh S., Tezel U., Konstantinidis K. T., and Pavlostathis S. G. (2013). Long-term exposure to benzalkonium chloride disinfectants results in change of microbial community structure and increased antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 9730–9738. doi: 10.1021/es401507k

The European Committe on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (2024). Beakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 14.0. Available online at: https://www.eucast.org/ (Accessed November 30, 2025).

Keywords: bacteriophages, biocides resistance, wastewater, Costa Rica, bacterial evolution

Citation: Chacon L, Mendoza-Guido B, Rodríguez-Rojas A and Rojas-Jimenez K (2025) Novel Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. inisa with potential phage-mediated tolerance to benzalkonium chloride. Front. Bacteriol. 4:1709187. doi: 10.3389/fbrio.2025.1709187

Received: 19 September 2025; Accepted: 03 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Selvankumar Thangaswamy, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), IndiaReviewed by:

Neelesh Kumar, Rani Lakshmi Bai Central Agricultural University, IndiaFarheen Akhtar, University of Michigan, United States

Copyright © 2025 Chacon, Mendoza-Guido, Rodríguez-Rojas and Rojas-Jimenez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luz Chacon, bHV6LmNoYWNvbkB1Y3IuYWMuY3I=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡ORCID: Luz Chacon, orcid.org/0000-0003-2506-0619

Bradd Mendoza-Guido, orcid.org/0009-0005-3214-4599

Alexandro Rodríguez-Rojas, orcid.org/0000-0002-4119-8127

Keilor Rojas-Jimenez, orcid.org/0000-0003-4261-0010

Luz Chacon

Luz Chacon Bradd Mendoza-Guido

Bradd Mendoza-Guido Alexandro Rodríguez-Rojas

Alexandro Rodríguez-Rojas Keilor Rojas-Jimenez

Keilor Rojas-Jimenez