- 1Scientific Council of Cardiology, Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations, Baghdad, Iraq

- 2Baghdad Heart Center, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq

Background: Over the last years, there was no established cardio-oncology service in Iraq and no firm data about the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among patients with cancer. As an initial step, we decided to conduct a national cardio-oncology online survey for cardiologists, oncologists, and their residents which would help us to understand the expected prevalence, problems, and readiness for collaboration between the two specialties.

Objectives: For evaluating the current national practice in the cardiology and oncology specialty fields and to identify the hidden gaps associated with the development or worsening of CVD among patients with cancer.

Methods: An online survey including 19-question for cardiologists/cardiology residents (CCRs) and 30-question for oncologists/oncology residents (OORs) about cardio-oncology service was sent to them including all Iraqi cities using Google document form during December 2020.

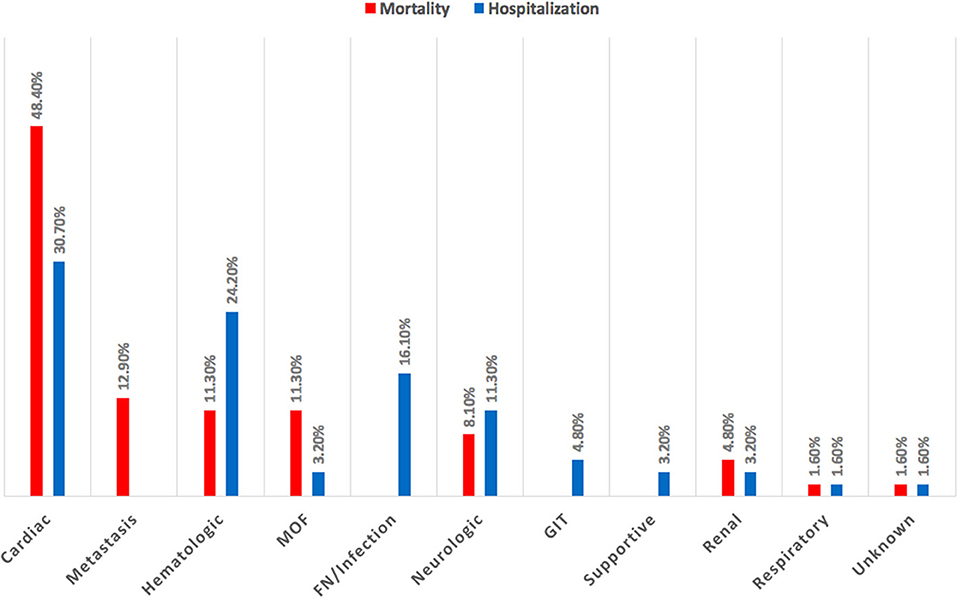

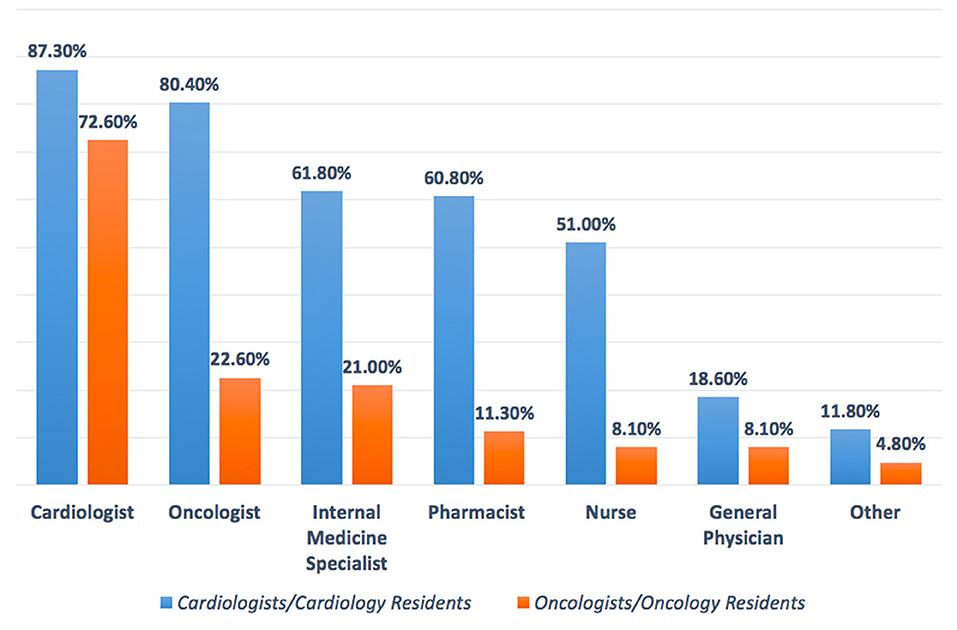

Results: The total number of responses was 164, mainly 62.2% from CCRs while 37.8% from OORs. Hypertension was the main baseline risk factor (71%). A 77.5% of CCRs prescribe cardiovascular drugs vs. 35.5% by OORs. About 76.5% of CCRs and 79% of OORs are facing difficulties in the management of patients with cancer with established CVD. CVD was the leading cause of both hospitalization (30.7%) and mortality (48.4%). About 62.8% of CCRs and 64.5% of OORs have an interest to work in cardio-oncology service.

Conclusion: Based on the perception of cardiologists and oncologists, CVD is the main cause of hospitalization and mortality among patients with cancer. High interest among CCRs and OORs to work in cardio-oncology service. Positive initiatives are available to take the action plan in this emerging field.

Introduction

Cardio-oncology is an emerging specialty and service with a team-based approach that includes cardiologists, oncologists, and hematologists working collaboratively for optimizing cardiovascular risk stratification, prevention, and treatment for all patients with cancer and survivors to guide best practice by bridging the gaps in knowledge and needs including supporting patients with cancer to improve continuing of their cancer therapies without interruption by the cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1–4). First cardio-oncology service emerged in 2010 (1, 4), therefore, such essential service was not available worldwide including Iraq. A descriptive study in the United Kingdom including data over 5-year activity from cardio-oncology service reported that baseline CVD and myocardial toxicity are higher than that was documented in previous studies (5). This is why continuing national and international research in the cardio-oncology field is of high importance for a better understanding of the current practice and optimization of cardio-oncology services. In 2019, the Iraqi Cardio-Oncology Program was founded by a senior consultant cardiologist and his mentee the cardiology clinical pharmacist to support the initiation of cardio-oncology services and as an initial step for evaluating the current national practice and uncovering the hidden gaps associated with the development or worsening of CVD especially during a very critical time of COVID-19 era, therefore, it was decided to conduct an online survey. An online survey has several advantages, including low costs, real-time access, not time-consuming, and respondents may be more willing to participate and had documented the need to improve the care of patients (2, 6).

Methods

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Department of Continuing Medical Education at the Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations.

Study Design

An online survey link including 19 questions for cardiologists/cardiology residents (CCRs) and 30 questions for oncologists/oncology residents (OORs) about cardio-oncology service was sent to participants who are working in cardiology and oncology sites in all 18 Iraqi cities using Google document form in December 2020. The link was shared with the participants by sending a message on WhatsApp or Viber applications for responding to the survey voluntarily. The message was sent either individually or by sharing it on WhatsApp or Viber groups for cardiologists, oncologists, and their residents.

Survey Questionnaires

Questions were divided into three categories: (1) about demographics of participants, (2) questions about current practice, and (3) questions about their opinions about cardio-oncology service. Some of the questions in categories two and three were directed only to oncologists [for OORs] related to baseline patients' characteristics and referral. One question was directed only to cardiologists (for CCRs). Other questions were directed to both cardiologists and oncologists. The single choice answer was used, including the “other” option to add unavailable suitable answers of the participants. Multiple choice answers were used for the cardio-oncology team question. Age was typed by the participants. Collected data were filled in excel for double check and analyzed in excel using numbers, percentages, average, and SD for the continuous variables.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Excel for Mac, Version 15.13.3.

Results

Demographics of Participants

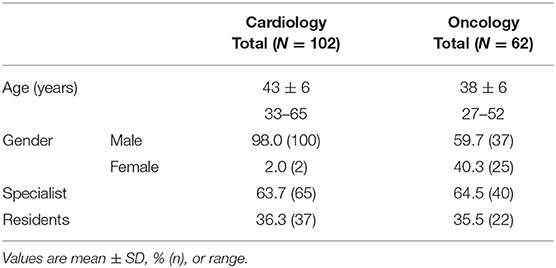

Most of the responders were male and specialists; cardiologists and oncologists, with age younger than 66 years old. Results are available in Table 1.

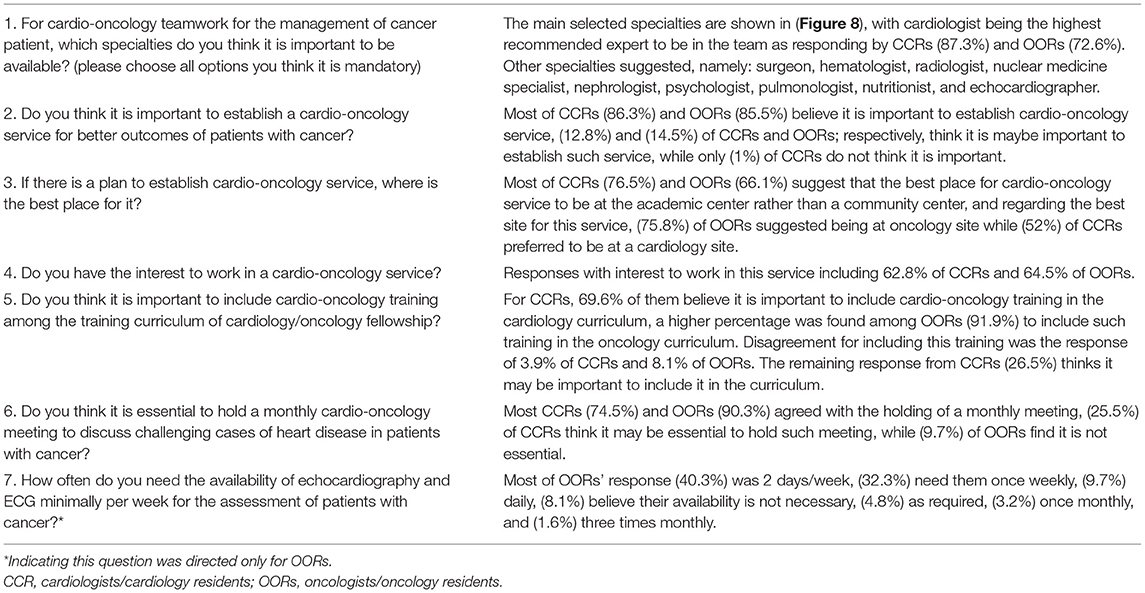

Questions About Current Practice Regarding Cardio-Oncology Patients

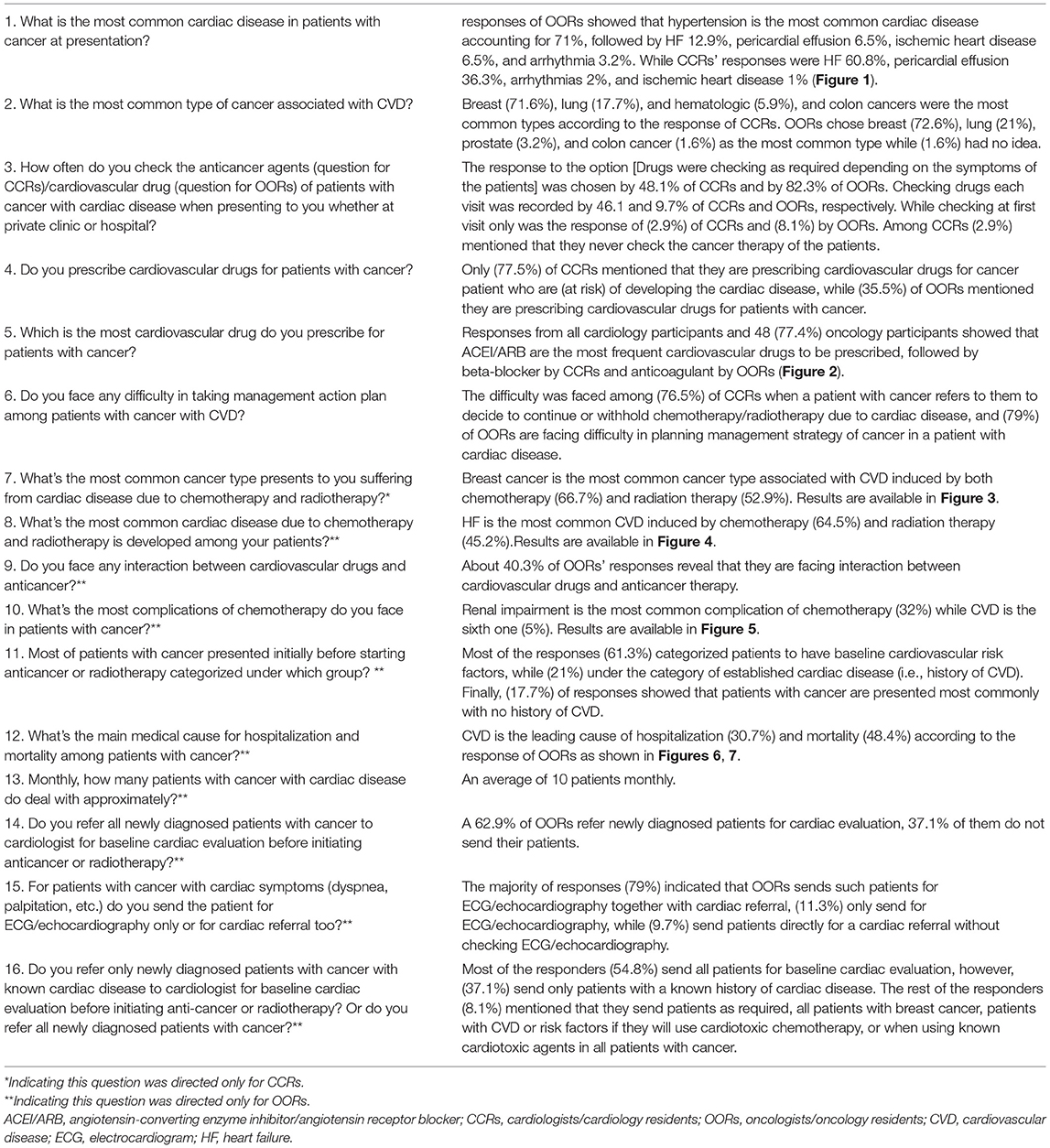

Hypertension (HTN) is the most common baseline CVD among patients with cancer according to the OOR experiences (71%), while heart failure (HF) was the most common one as a result of the CCR responses (60.3%). The results of these questions are available in (Table 2 and Figures 1–7).

Figure 1. Most common baseline cardiovascular disease among patients with cancer. Prevalence of baseline cardiovascular disease, hypertension is the most common risk factor according to responses of the oncologists/oncology residents. HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; IHD, ischemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

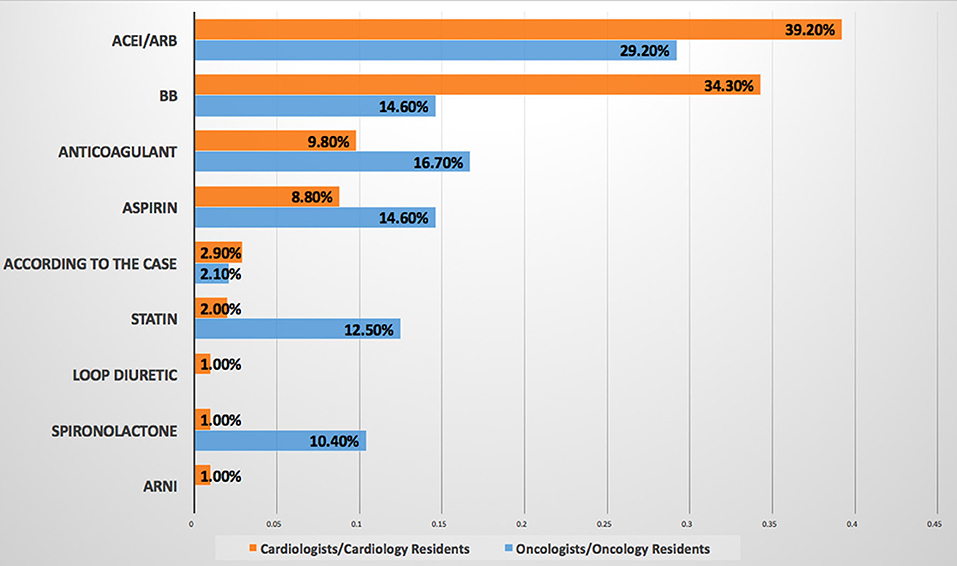

Figure 2. Most commonly prescribed cardiovascular drug for patients with cancer. ACEI/ARB are the most commonly prescribed cardiovascular drug for patients with cancer by both cardiologists/cardiology residents and oncologists/oncology residents. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor.

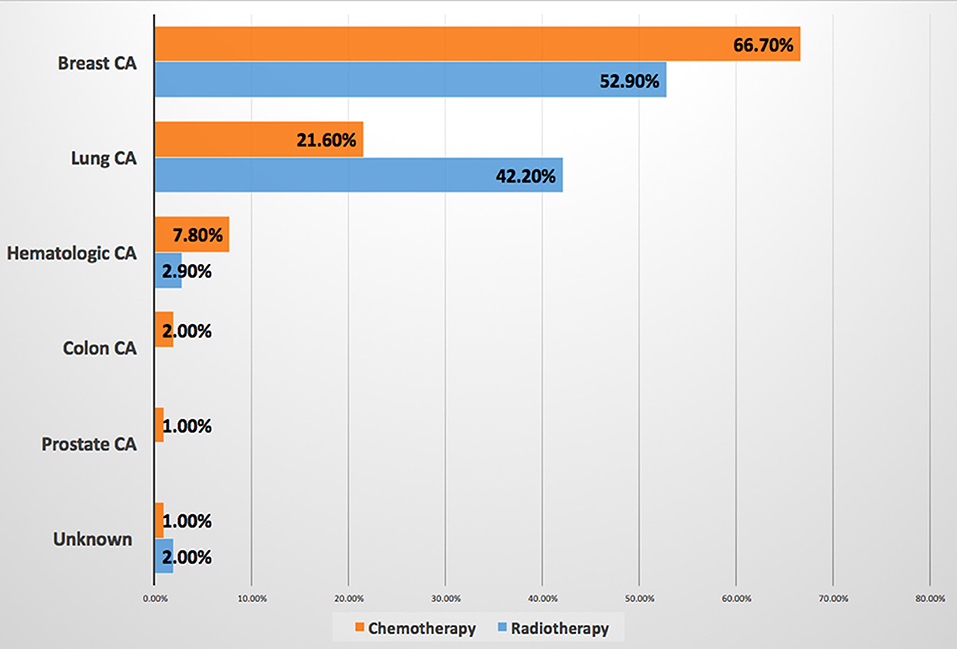

Figure 3. Most cancer types associated with cancer therapy-induced cardiovascular disease. Breast cancer is the most common malignancy associated with CVD induced by both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. CA, cancer; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

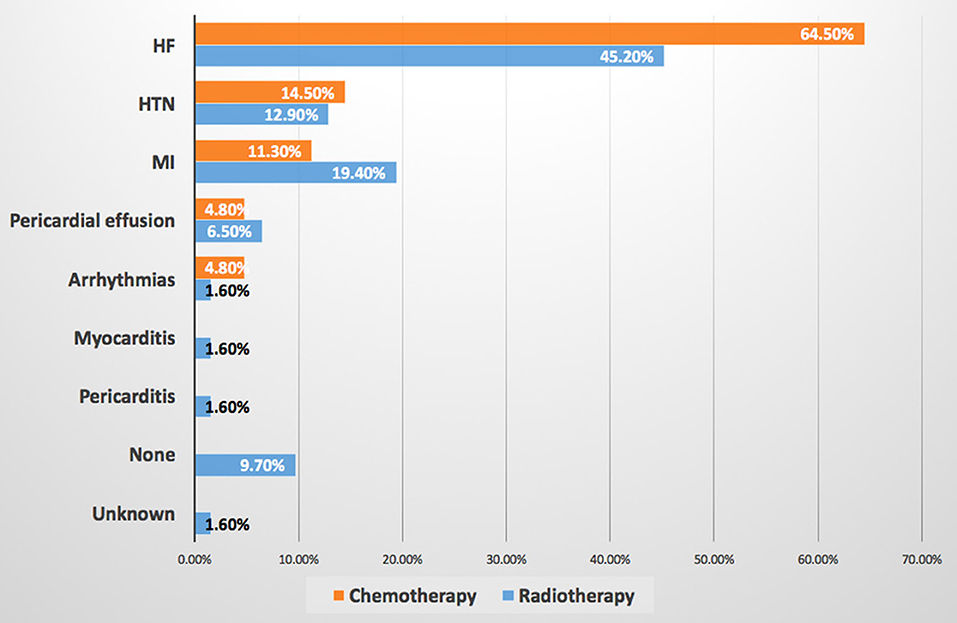

Figure 4. Most common cardiovascular disease induced by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. HF is the most common CVD induced by both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction.

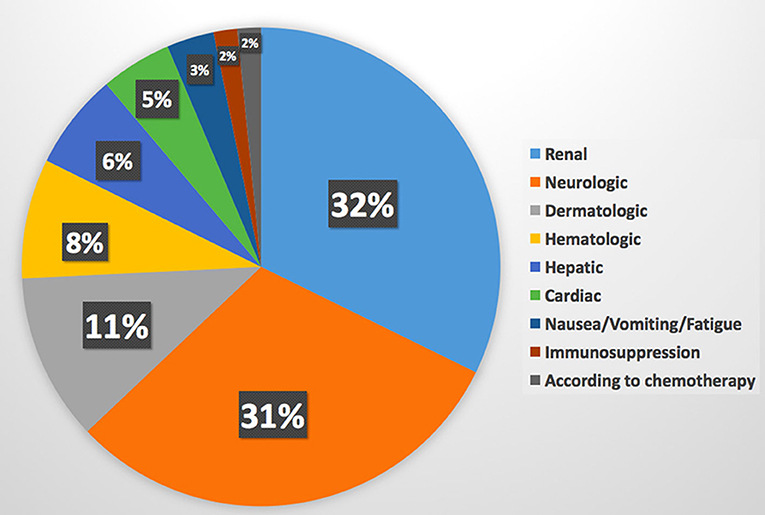

Figure 5. Most common complications of chemotherapy. Cardiovascular disease is the sixth complication of chemotherapy.

Figure 6. Main medical cause for hospitalization and mortality among patients with cancer. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of hospitalization and mortality among patients with cancer. GIT, gastrointestinal tract; MOF, multi-organ failure.

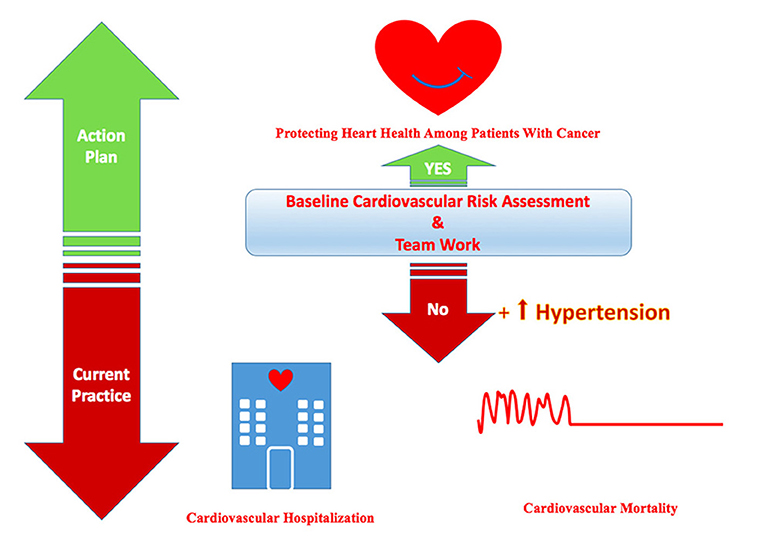

Figure 7. Central illustration showing the current practice and the required action plan to protect heart health among patients with cancer. Hypertension is the most common baseline cardiovascular risk factor among cancer patients according to the current practice which can be the leading cause of cardiovascular hospitalization and mortality. The action plan is required to protect the heart health of cardio-oncology patients by baseline cardiovascular risk assessment and teamwork.

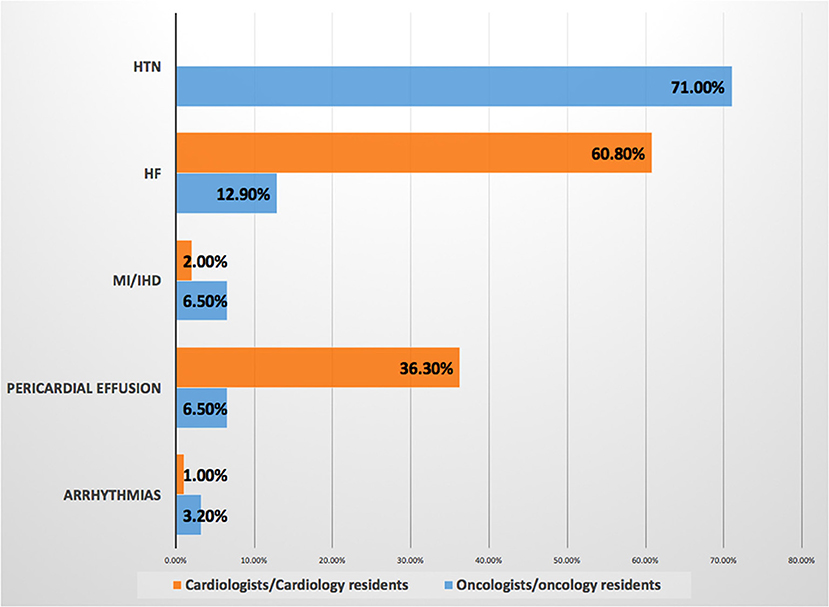

Questions About Their Opinions About Cardio-Oncology Service

The majority of CCRs (86.3%) and OORs (85.5%) believe that the establishment of cardio-oncology services will improve the outcomes of patients. The details are available in (Table 3 and Figure 8).

Figure 8. Suggest cardio-oncology team members. Cardiologists, oncologists, internal medicine specialists, and pharmacists are the main specialists in the cardio-oncology team. Oncologists/oncology residents tend to focus mainly on cardiologists as a member of the cardio-oncology team.

Discussion and Conclusion

This survey showed that HTN was the most common preexisting CVD among patients with cancer according to the response of about two-third of OORs, while none of the CCRs mentioned it as a baseline CVD, at the same time OORs reported prescribing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) mainly for patients with cancer, this may indicate that they are treating HTN in such patients without referring to cardiologists. Published evidence documented that HTN is the most common baseline comorbid disease among patients with cancer with the prevalence of 38–42% before initiation of cancer therapy, however, after initiation of cancer therapy the incidence of de novo or worsening HTN ranging between 17 and 80% (6–9). It is known that CVD and cancer are sharing the same risk factors and preventive strategies, and pre-existing CVD in newly diagnosed patients with cancer may attribute to increasing morbidity and mortality, however, limited studies focus light on the prevalence of pretreatment cardiovascular risk factors (10, 11). A recently published JACC perspective can be considered as a roadmap to improve education and training in the field of cardio-oncology to prevent CVD among patients with cancer rather than direct treatment (12). Regarding the most common CVD induced by chemotherapy and radiation therapy, both the CCRs and OORs reported HF as the first complication, then CCRs reported HTN as the second cardiac complication followed by myocardial infarction, while OORs reported the second complication is myocardial infarction followed by HTN, therefore, both the CCRs and OORs confirm that HTN incidence is among the first top three complications of cancer therapy. HF is a known complication of cancer and radiation therapies particularly in breast cancer, in addition, chest radiation accelerates atherosclerosis and cardiomyopathies (2, 13–15). Systemic HTN can be associated with both chemotherapies and immunologic therapies thus further increasing the burden of cardiovascular toxicities, it was estimated that novel cancer therapy can induce HTN by 24% (7–13). Moreover, resistant HTN and hypertensive crisis are associated with surgery or radiotherapy involving the head or neck (8). Therefore, treatment of HTN is one of the cornerstones for reducing the major cardiovascular events such as HF and end-stage renal failure in addition to overall mortality (7). The most common cardiovascular drug prescribed was ACEI/ARB as reported by both CCRs and OORs followed by anticoagulant and aspirin prescribed by OORs and beta-blockers prescribed by CCRs, this may be interpreted by the OORs use of ACEI/ARB for treating HTN among patients with cancer as a first-line drug as mentioned above. While ACEI/ARN and BB explain that CCRs prescribe them for patients with cancer who are (at risk) of CVD and patients with HF. In UK-based cardio-oncology service, it was also documented that beta-blockers and ACEI/ARB were the most prescribed drug for the referred cardio-oncology patients (6). Beta-blockers are considered cardioprotective drugs among patients with cancer for their beneficial effect in CVD and for the growing evidence regarding their role in breast cancer as it is associated with a significantly lower rate of metastasis particularly with propranolol, significantly reducing HF incidence during anthracyclines therapy with or without trastuzumab, and reducing of cancer-specific mortality rate among patients with prostate cancer whether using cardioselective or noncardioselective beta-blockers (16). Most of the CCRs and OORs reported that the main cancer type associated with CVD related to chemotherapy and radiation therapy are breast cancer and lung cancer, therefore, focusing attention on these two types of cancer particularly baseline risk factors assessment is important to prevent CVD complications. Current evidence also reported breast cancer as the first type of malignancies associated with CVD and the cause of referral (6, 14). More than two-third of OORs reported facing drug-drug interactions, despite this, they are checking for drug-drug interaction only when it is required depending on symptoms as reported by more than two-third of OORs and by about half of CCRs, i.e., checking after the interactions were taking place and this will increase the incidence of drug-drug interactions. Documented harmful drug-drug interactions among patients with cancer who are receiving oral cancer therapy are very common reaching 46% including 15% major and 83% moderate harmful interactions, 14% of interactions including cancer therapy and QT interactions (17). According to the OORs response of survey, CVD is the sixth complication of chemotherapy, however, the majority of the response of OORs regarding the main cause of hospitalization and mortality among cardio-oncology patients is CVD, this may be explained by uncontrolled baseline CV risk factors and underestimating of evaluation drug-drug interactions which may increase CVD or risks which exacerbate CVD leading to hospitalization and mortality. Evidence showed that cardiovascular hospitalization is the main cause of prostate cancer and the third cause of noncancer hospitalization among patients with cancer in general and noncancer mortality is highest among patients with colorectal, bladder, kidney, endometrium, breast, prostate, and testis cancers with heart disease being the most common cause (18, 19). Other findings in this study reported more than two-third of CCRs and OORs are facing difficulties while taking management action plans among cardio-oncology patients which necessitates teamwork and availability of guidelines and protocols for the management of cardio-oncology patients. Most CCRs and OORs agreed that the cardio-oncology team should include cardiologists, however, most CCRs believe that the team should include also oncologists, internal medicine specialists, and pharmacists, in addition to other specialties, however, the minority of OORs tend to include other specialties among the cardio-oncology team. It is known that cardiologists have an important role in the prevention of cardiovascular complications among patients with cancer through a comprehensive evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors and physical examination before initiation of cancer therapy (20), however, other specialties are also essential to be included among the cardio-oncology team for better outcomes, for example, the availability of pharmacists to prevent or minimize harmful drug-drug interactions which commonly occur (17). The proposed typical cardio-oncology team includes cardiologists, oncologists, hematologists, general practitioners, pharmacists, nurses, cardiac surgeons, radiologists, clinical laboratory specialists, palliative care team, psychologists, social workers, and data managers, depending on hospital size and organization (20). The current survey discovered several encouraging and strength points for the initiation of cardio-oncology services in Iraq including more than one-half of both CCRs and OORs have the interest to work in cardio-oncology service, most of the CCRs and OORs believe in the importance of holding a monthly cardio-oncology meeting to discuss together challenging cardio-oncology cases, and two-third of CCRs want to include cardio-oncology training in cardiology curriculum and almost all OORs wish to include such training in the oncology curriculum, all these points are promising for the near future improvement in the standard of cardiac services for patients with cancer to achieve the mission of our cardio-oncology program by protecting heart health among cardio-oncology patients.

This study depended on an online survey reflecting the expert opinions, therefore, the real prevalence of baseline cardiovascular risk factors and other results among patients with cancer need to be documented by clinical researchers and registries.

In conclusion, according to the survey-based data depending on the perception of cardiologists and oncologists, CVD is the leading cause of hospitalization and mortality among cardio-oncology patients, despite that CVD may be considered as the sixth rank complications among cancer therapy. There are essential needs to focus on the baseline CV risk stratification among patients with cancer to prevent CVD or CVD worsening by emphasizing on teamwork. There is an increasing interest among cardiologists, oncologists, and their residents in cardio-oncology teamwork and cardio-oncology training. It is time to take the action plan to change the current real practice to bridge the gap in the cardio-oncology service and to support clinical researches and registries in this field.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

HF and IY contributed equally in study design, writing, review, and approve for publication. IY performed the statistical analysis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all participants in Iraq who responded to this survey.

References

1. Larsen CM, Mulvagh SL. Cardio-oncology: what you need to know now for clinical practice and echocardiography. Echo Res Pract. (2017) 4:R33–41. doi: 10.1530/ERP-17-0013

2. Barac A, Murtagh G, Carver JR, Chen MH, Freeman AM, Freeman AM, et al. Cardiovascular health of patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a roadmap to the next level. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 65:2739–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.059

3. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Muñoz DR, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Aboyans V, et al. ESC position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC committee for practice guidelines. Eur Heart J. (2016). 37:2768–801. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211

4. Lyon AR, Dent S, Stanway S, Earl H, Brezden-Masley C, Cohen-Solal A, et al. Baseline cardiovascular risk assessment in cancer patients scheduled to receive cardiotoxic cancer therapies: a position statement and new risk assessment tools from the cardio-oncology study group of the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology in collaboration with the international cardio-oncology society. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22:1945–60. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1920

5. Pareek N, Cevallos J, Moliner P, Shah M, Tan LL, Chambers V, et al. Activity and outcomes of a cardio-oncology service in the United Kingdom-a five-year experience. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20:1721–31. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1292

6. Safdar N, Abbo LM, Knobloch MJ, Seo SK. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: survey and qualitative research. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2016) 37:1272–7. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.171

7. Chung R, Tyebally S, Chen D, Kapil V, Walker JM, Addison D, et al. Hypertensive cardiotoxicity in cancer treatment-systematic analysis of adjunct, conventional chemotherapy, and novel therapies-epidemiology, incidence, and pathophysiology. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:3346. doi: 10.3390/jcm9103346

9. Davis MK, Rajala JL, Tyldesley S, Pickles T, Virani SA. The prevalence of cardiac risk factors in men with localized prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy in British Columbia, Canada. J Oncol. (2015) 2015:820403. doi: 10.1155/2015/820403

10. Coviello JS. Cardiovascular and cancer risk: the role of cardio-oncology. J Adv Pract Oncol. (2018) 9:160–76. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2018.9.2.3

11. Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A, Konety SH. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation. (2016) 133:1104–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020406

12. Alvarez-Cardona JA, Ray J, Carver J, Zaha V, Cheng R, Yang E, et al. Cardio-oncology education and training: JACC council perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2267–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.079

13. Brown SA. Preventive cardio-oncology: the time has come. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 6:187. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00187

14. Jairam V, Lee V, Park HS, Thomas CR Jr, Melnick ER, Gross CP, et al. Treatment-related complications of systemic therapy and radiotherapy. JAMA Oncol. (2019) 5:1028–35. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0086

15. Narayan V, Ky B. Common cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: epidemiology, risk prediction, and prevention. Annu Rev Med. (2018) 69:97–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041316-090622

16. Peixoto R, Pereira ML, Oliveira M. Beta-Blockers and Cancer: Where Are We? Pharmaceuticals. (2020) 13:105. doi: 10.3390/ph13060105

17. van Leeuwen RW, Brundel DH, Neef C, van Gelder T, Mathijssen RH, Burger DM, et al. Prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions in cancer patients treated with oral anticancer drugs. Br J Cancer. (2013) 108:1071–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.48

18. Whitney RL, Bell JF, Tancredi DJ, Romano PS, Bold RJ, Wun T, et al. Unplanned hospitalization among individuals with cancer in the year after diagnosis. J Oncol Pract. (2019) 15:e20–9. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00254

19. Zaorsky NG, Churilla TM, Egleston BL, Fisher SG, Ridge JA, Horwitz EM, et al. Causes of death among cancer patients. Ann Oncol. (2017) 28:400–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw604

Keywords: breast cancer, heart failure, hypertension, risk factor, hospitalization, mortality, online survey

Citation: Farhan HA and Yaseen IF (2021) Perceptions of the Cardiologists and Oncologists: Initial Step for Establishing Cardio-Oncology Service. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8:704029. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.704029

Received: 01 May 2021; Accepted: 22 October 2021;

Published: 24 November 2021.

Edited by:

Nicola Maurea, Istituto Nazionale Tumori Fondazione G. Pascale (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Chiara Lestuzzi, Santa Maria degli Angeli Hospital Pordenone, ItalyMohammed Alomar, University of South Florida, United States

Hadi Skouri, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Lebanon

Copyright © 2021 Farhan and Yaseen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Israa Fadhil Yaseen, cGhhcm0xOGlAeWFob28uY29t

Hasan Ali Farhan

Hasan Ali Farhan Israa Fadhil Yaseen

Israa Fadhil Yaseen