Abstract

Background: The relationship between thyroid function and cardiac disease is complex. Both hypothyroidism and thyrotoxicosis can predispose to ventricular arrhythmia and other major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), so that a U-shaped relationship between thyroid signaling and the incidence of MACE has been postulated. Moreover, recently published data suggest an association between thyroid hormone concentration and the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) even in euthyroid populations with high-normal FT4 levels. In this study, we investigated markers of repolarization in ECGs, as predictors of cardiovascular events, in patients with a spectrum of subclinical and overt thyroid dysfunction.

Methods: Resting ECGs of 100 subjects, 90 patients (LV-EF > 45%) with thyroid disease (60 overt hyperthyroid, 11 overt hypothyroid and 19 L-T4-treated and biochemically euthyroid patients after thyroidectomy or with autoimmune thyroiditis) and 10 healthy volunteers were analyzed for Tp-e interval. The Tp-e interval was measured manually and was correlated to serum concentrations of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (FT3) and thyroxine (FT4).

Results: The Tp-e interval significantly correlated to log-transformed concentrations of TSH (Spearman's rho = 0.30, p < 0.01), FT4 (rho = −0.26, p < 0.05), and FT3 (rho = −0.23, p < 0.05) as well as log-transformed thyroid's secretory capacity (SPINA-GT, rho = −0.33, p < 0.01). Spearman's rho of correlations of JT interval to log-transformed TSH, FT4, FT3, and SPINA-GT were 0.51 (p < 1e−7), −0.45 (p < 1e−5), −0.55 (p < 1e−8), and −0.43 (p < 1e−4), respectively. In minimal multivariable regression models, markers of thyroid homeostasis correlated to heart rate, QT, Tp-e, and JT intervals. Group-wise evaluation in hypothyroid, euthyroid and hyperthyroid subjects revealed similar correlations in all three groups.

Conclusion: We observed significant inverse correlations of Tp-e and JT intervals with FT4 and FT3 over the whole spectrum of thyroid function. Our data suggest a possible mechanism of SCD in hypothyroid state by prolongation of repolarization. We do not observe a U-shaped relationship, so that the mechanism of SCD in patients with high FT4 or hyperthyroidism seems not to be driven by abnormalities in repolarization.

Introduction

The relationship of thyroid disorders and cardiovascular diseases raises growing interest (1–3). Both, hypothyroid or hyperthyroid conditions may lead to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (4). This well-accepted U-shaped relationship between thyroid function and cardiac disease is, however, still not fully clarified (5). As far as we know today, the mechanisms of hypo- or hyperthyroidism leading to cardiac diseases are diverse with effects on cardiac contractility, vasculature and cardiac electrophysiology (6, 7).

In a general population study an association between thyroid hormone levels, even within the respective normal range, and ECG changes has been described (8). Published data suggest an association between thyroid hormone concentrations and the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) even in euthyroid populations with high-normal FT4 concentration (9). Recently, similar relations between thyroid function and the incidence of other endpoints, including malignant arrhythmia and stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo syndrome), have been described (10, 11). However, the electrophysiological mechanisms underlying these observations are poorly understood up to now.

Repolarization abnormalities, especially prolonged repolarization, are assumed to be among the major risk factors for SCD (12, 13). Contradicting observations have been published concerning the effect of thyroid hormone levels especially on the QTc interval (14–18). Whereas, the effect of thyroid hormone disorders on the QTc interval has been extensively studied, very little is known on ventricular repolarization as measured by more specific repolarization markers including Tpeak-to T-end interval (Tp-e) or JT interval. The Tp-e interval has been established and recognized as a correlate of dispersion of ventricular repolarization (19). A prolonged Tp-e interval, and therefore a longer dispersion of ventricular repolarization, may be associated with ventricular tachyarrhythmias (20); similar findings were reported regarding the JT interval (13).

Interestingly, a prolonged Tp-e interval seems independently associated with SCD, even if the QTc is normal (21). Recently, one study showed a prolongation of Tp-e interval in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (22). However, data on patients with overt thyroid disorders and hyperthyroidism have not been published up to now.

In this study, we investigated the Tp-e and JT intervals in ECGs of patients with a spectrum of subclinical and overt thyroid dysfunction and a euthyroid control group to assess pathological repolarization as a potential indicator of SCD.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This study included 90 patients of the NOMOTHETICOS cohort (23) with untreated and treated primary thyroid dysfunction and for comparison 10 healthy volunteers. In all subjects a full thyroid hormone profile and 12-lead ECG measurements were performed.

None of the subjects had a severely impaired left ventricular ejection fraction (LV-EF < 45%) or a left bundle branch block.

Additional inclusion criteria for patients with thyroid disease were

-

Disconnected feedback control due to the following conditions at the time of recruitment:

-

° Overt primary hypothyroidism with TSH level being higher than 10 mIU/l and FT4 concentration below 7 pmol/l (5.4 ng/l) (group 1)

-

° Overt primary hyperthyroidism with TSH level below 0.1 mIU/l and FT4 concentration higher than 18 pmol/l (14 ng/l) (group 3)

-

° All other constellations, if the patient receives substitution therapy with more than 1.75 μg Levothyroxin per kg of body mass (group 2).

-

-

System in equilibrium (requiring no or unchanged substitution dose over the previous 6 weeks before investigation).

Inclusion criterion for healthy volunteers (group 0) were normal thyroid function with ruled out thyroid disease via ultrasound and normal concentrations of antibodies to thyroid peroxidase (TPOAb), thyroglobulin (TgAb), and TSH receptors (TRAb).

Exclusion criteria for all subjects were pituitary or hypothalamic disease, resistance to thyroid hormone, Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, severe illness possibly associated with non-thyroidal illness syndrome (TACITUS), medication influencing pituitary function and pregnancy.

All subjects delivered written informed consent. The study design was approved by the local institutional ethics committee of the Medical Faculty at the Ruhr University of Bochum under the file number 3718-10. The protocol of the NOMOTHETICOS study (UTN U1111-1122-3273) has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (ID NCT01145040) and in the German Clinical Trials Register (ID DRKS00003153).

ECG Measurements

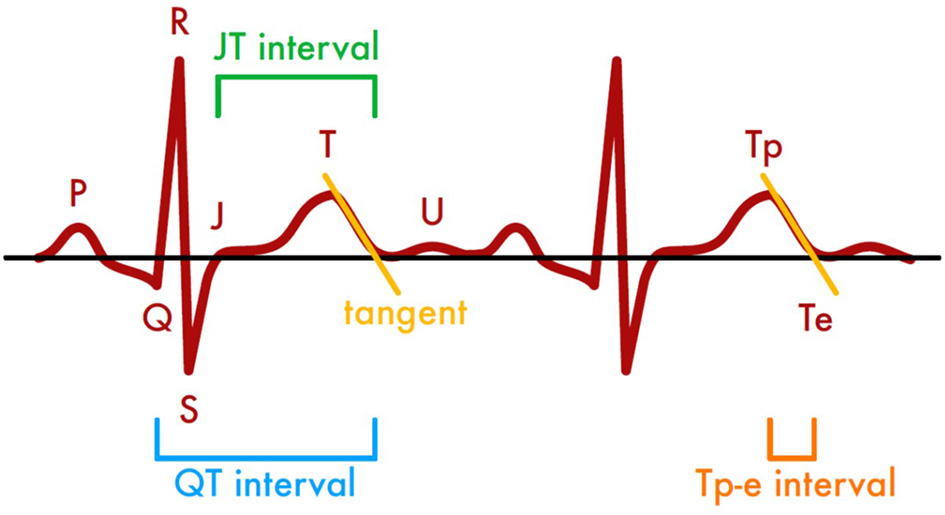

All anonymized ECG recordings were distributed to three independent cardiologists blinded for laboratory results. The QT interval, defined as beginning of Q wave to the end of T wave, the JT interval, defined as the period from the J point (junction between the termination of the QRS complex and the beginning of the ST segment) to the end of the T wave, and Tp-e interval, defined as the distance of T wave peak to the end of T wave, were measured (Figure 1). The end of the T wave was determined by the tangent method (24). All measurements were performed manually and preferentially in lead V5. If a measurement in V5 was not possible the investigators were instructed to select alternatively lead V2–V4 or lead II (25).

Figure 1

Methods of assessing time intervals in ECG recordings based on the tangent method.

Laboratory Measurements

Serum concentrations of TSH, FT4, and FT3 were determined with a fully automated chemiluminescence-based system (DxI800, Beckman-Coulter, Krefeld, NRW, Germany). The intra-assay and inter-assay CVs for these analyses vary with concentrations but are <10% for the range of measurement. Thyroid tissue antibodies (TPOAb, TgAb, and TRAb) were measured with quantitative radioimmunoassays (anti-TPOn, anti-Tgn and TRAKhuman, ThermoFisher, BRAHMS division, Henningsdorf, BB, Germany).

To assess the relative contributions of the pituitary and thyroid gland to the variations in hormone concentrations, Jostel's TSH index (JTI), thyroid's secretory capacity (SPINA-GT), and the sum activity of peripheral deiodinases (SPINA-GD) were calculated from steady-state concentrations of TSH and FT4 and constants for plasma protein binding and kinetics, as recently recommended for thyroid trial design (23, 26).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with custom S scripts written for the environment R 3.6.3 on macOS. Depending on the class of analyzed data and possible direction of causality, distributions were compared with multivariable regression, 2-sample Student's t-test (Gaussian distributed variables), Wilcoxon's rank sum test (non-Gaussian variables) or chi-square test (counts). All four groups were compared with one-way ANOVA and post-hoc pairwise t-test. Alpha error correction for multiple testing was performed with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Continuous variables were tested for normality with quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots of z-transformed values.

To identify parameters that independently correlate to electrophysiological markers we conducted step-wise multivariable regression analysis based on variables that had a significant association to ECG markers in a univariable investigation. For this purpose, an initial maximal model including all possible predictors as suggested by univariable analysis was successively simplified by eliminating non-significant parameters to deliver a final minimal model containing significant predictors only. Thyroid volume and calculated parameters of thyroid homeostasis were not included in multivariable models in order to avoid multicollinearity. Before inclusion in a multivariable model TSH and thyroid hormone concentrations were logarithmically transformed to meet criteria of a normal distribution.

Where not otherwise specified, data are presented as mean value ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for normally distributed continuous data, as median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data or as absolute numbers (percentages) for count data. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

One hundred subjects were included in the analysis, 90 patients with thyroid disease (60 overt hyperthyroid, 11 overt hypothyroid and 19 L-T4-treated and biochemically euthyroid patients after thyroidectomy or with autoimmune thyroiditis) and 10 healthy volunteers for comparison purposes (Table 1). The mean age of the subjects was 52.8 ± 1.60 years, and 69 patients were women.

Table 1

| Group 0 (normal subjects) | Group 1 (hypothyroidism) | Group 2 (full-dose L-T4 substitution therapy) | Group 3 (thyrotoxicosis) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 11 | 19 | 60 |

| Age (years) | 56.3 ± 4.9 | 56.7 ± 4.6 | 45.1 ± 3.0 | 54.0 ± 2.1 |

| Female (%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (54%) | 17 (89%) | 40 (67%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 1.0 | 32.7 ± 3.4†† | 25.1 ± 1.7** | 25.0 ± 0.7** |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (17%) |

| Thyroid disease | ||||

| Acute or subacute thyroiditis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Amiodarone-induced thyroid disease | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Toxic adenoma | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Hashimoto's disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ord's disease | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Graves' disease | 0 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| Graves' disease with Hashimoto component | 0 | 1 | 3 | 20 |

| Schmidt-Carpenter's syndrome | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Marine-Lenhart syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Post-surgical or radiogenic hypothyroidism | 0 | 2 | 11 | 0 |

| Sodium (135–145 mmol/L) | 138.8 ± 0.6 | 139.9 ± 1.0 | 139.6 ± 0.9 | 138.8 ± 0.4 |

| Potassium (3.5–5 mmol/L) | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 |

| Calcium (2.2–2.6 mmol/L) | 2.3 ± 0.0 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1† | 2.4 ± 0.0 |

| Creatinine (71–124 μmol/L) | 75.1 (35.4)† | 97.2 (35.4)††† | 61.9 (8.8)* | 61.9 (26.5)*** |

| HbA1c (4–6%) | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.1 |

| Beta1-selective beta-blocker use | 3 (30%) | 4 (36%) | 5 (26%) | 27 (45%) |

| Unselective beta-blocker use | 0 (0%)††† | 0 (0%)††† | 0 (0%)††† | 21 (35%)***‡‡‡ |

| Cardiac glycoside use | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) |

| Amiodarone use | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (12%) |

| Carbamazepine use | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Methylphenidate use | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Antipsychotic drug use | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (3%) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (3%) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant used | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (3%) |

| Antihistamine use | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Thyroid volume (mL) | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 12.3 ± 3.4†† | 8.4 ± 3.2††† | 27.9 ± 2.1** |

| Levothyroxine dosage (μg/day) | 0 ± 0 | 52.3 ± 23.0 | 88.2 ± 22.7†††‡‡‡ | 8.3 ± 5.3 |

Basic characteristics of study population.

Corrected p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***) compared to group 1 (hypothyroidism). Corrected p < 0.05 (†), < 0.01 (††), < 0.001 (†††) compared to group 3. Corrected p < 0.001 (‡‡‡) compared to group 0. See Supplementary Tables 1–20 for detailed p-values.

Phenotype of Thyroid Homeostasis

As shown in Table 2, TSH and thyroid hormones of subjects in group 0 were in the respective reference ranges. This also applies to calculated parameters for thyroid output (SPINA-GT), total deiodinase activity (SPINA-GD) and Jostel's TSH index and, with the exception of a slightly higher mean TSH concentration, to all markers in group 2. Deiodinase activity was elevated in group 1, representing an activated TSH-T3 feedforward control in the setting of elevated TSH concentrations (Table 2).

Table 2

| Parameter (reference range) | Group 0 (normal subjects) | Group 1 (hypothyroidism) | Group 2 (full-dose L-T4 substitution therapy) | Group 3 (thyrotoxicosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSH (0.35–3.5 mIU/L) | 1.47 (0.91)***†††† | 76.33 (92.48)††††‡‡‡ | 1.41 (3.33)****†††† | 0.03 (0.04)****‡‡‡‡ |

| FT4 (8–18 pmol/L) | 12.2 (3.2)***†††† | 3.9 (2.3)****††††‡‡‡ | 12.9 (3.9)****†††† | 45.0 (22.5)****‡‡‡‡ |

| FT3 (3.5–6.3 pmol/l) | 4.9 (0.6)***†††† | 3.0 (0.8)††††‡‡‡ | 4.7 (1.0)****†††† | 16.1 (13.6)****‡‡‡‡ |

| SPINA-GT (1.4–8.7 pmol/s) | 2.74 (1.24)***†††† | 0.31 (0.18)††††‡‡‡ | N/A | 307.27 (940.48)****‡‡‡‡ |

| SPINA-GD (20–60 nmol/s) | 34.7 (7.1)**** | 62.9 (50.6)††††‡‡‡ | 35.4 (15.9)****†††† | 30.2 (16.2)**** |

| JTI (1.3–4.1) | 2.0 ± 0.2* | 4.9 ± 0.2† | 1.6 ± 0.5** | 2.7 ± 0.4* |

Measured and calculated parameters of thyroid homeostasis in the four groups.

Corrected p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), < 1e−4 (****) compared to group 1. Corrected p < 0.05 (†), < 0.01 (††), < 0.001 (†††), < 1e−4 (††††) compared to group 3. Corrected p < 0.001 (), < 1e−4 () compared to group 0.

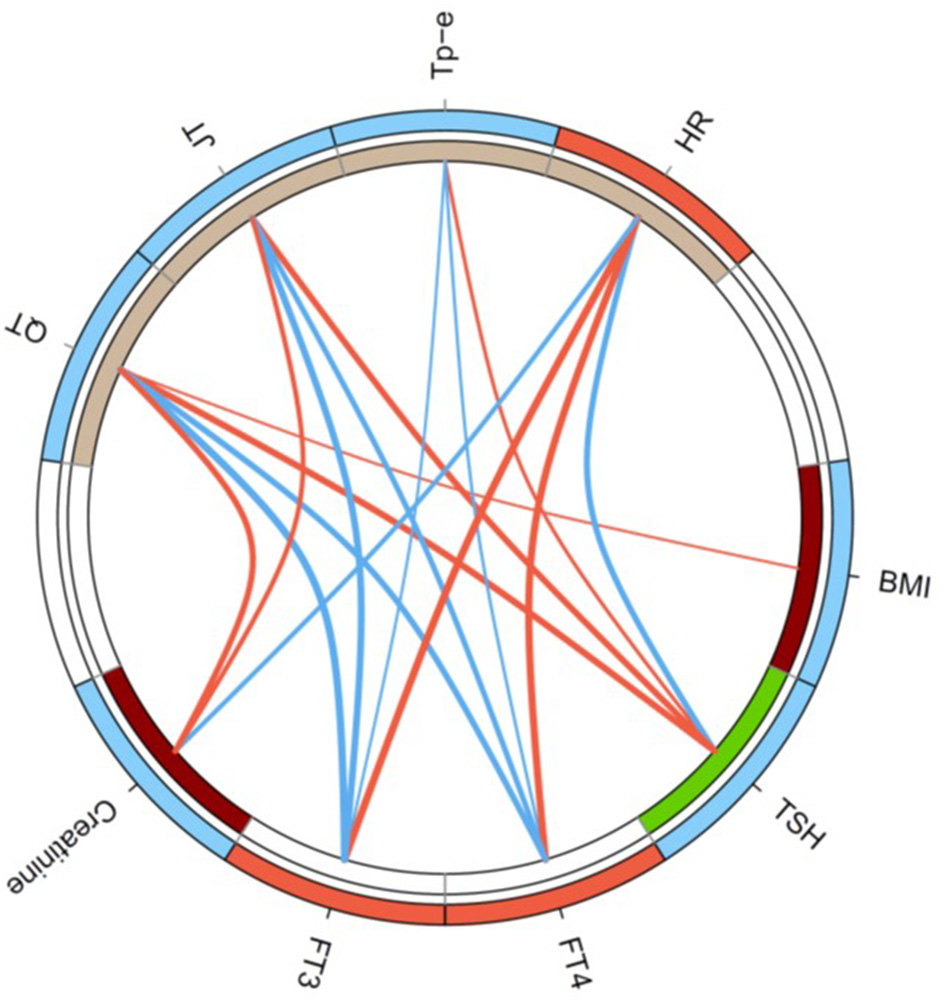

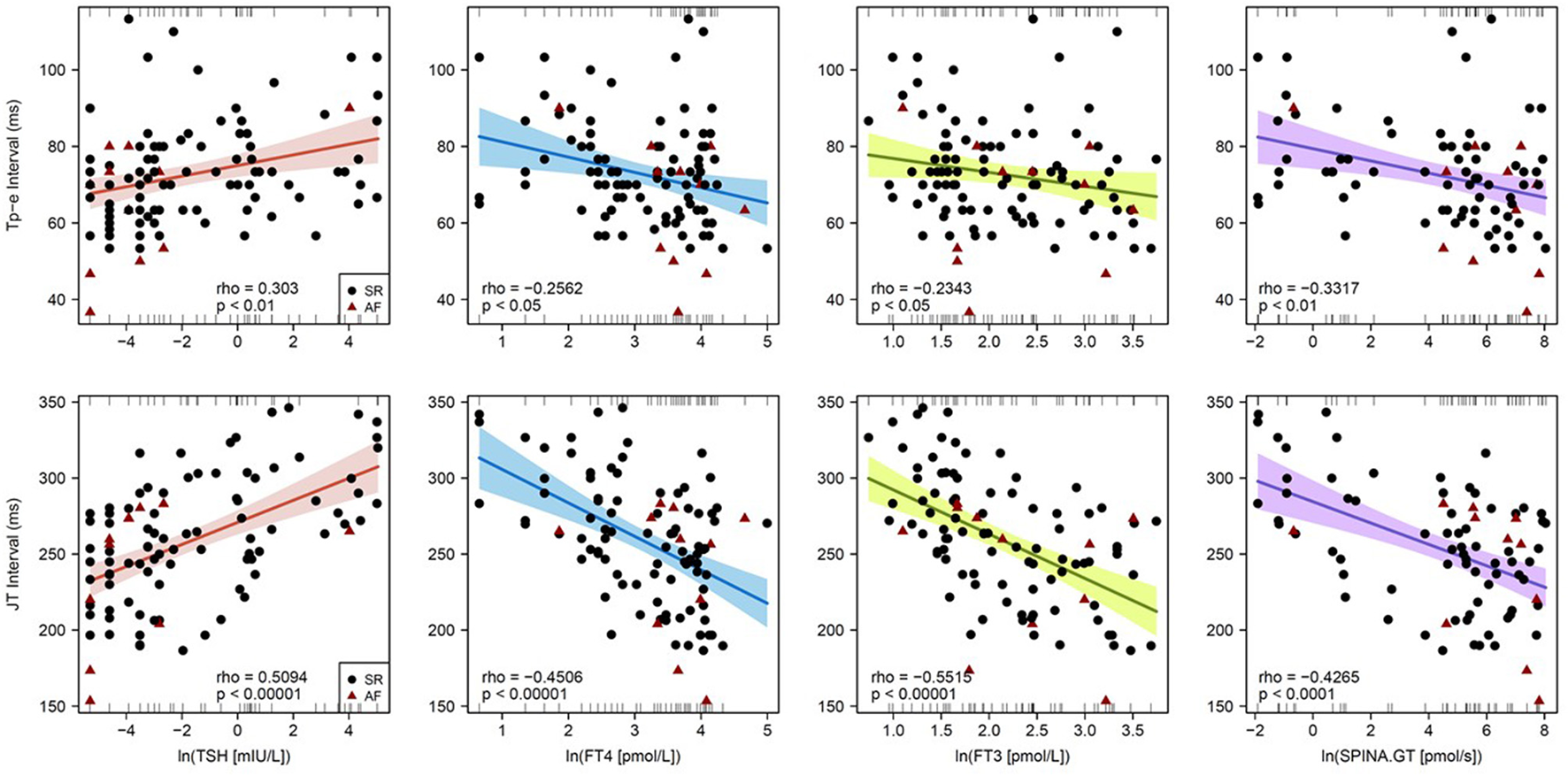

In univariable regression analysis, the correlation of heart rate to clinical and endocrine parameters demonstrated an inverse pattern to that of repolarization markers (Figure 2). In detail, the Tp-e interval significantly correlated to log-transformed concentrations of TSH (Spearman's rho = 0.30, p < 0.01), FT4 (rho = −0.26, p < 0.05), and FT3 (rho = −0.23, p < 0.05) as well as log-transformed thyroid's secretory capacity (SPINA-GT, rho = −0.33, p < 0.01). Spearman's rho of correlations of JT interval to log-transformed TSH, FT4, FT3, and SPINA-GT were 0.51 (p < 1e−7), −0.45 (p < 1e−5), −0.55 (p < 1e−8), and −0.43 (p < 1e−4), respectively (Figure 3). Group-wise evaluation in hypothyroid, euthyroid and hyperthyroid subjects revealed similar correlations in all three groups.

Figure 2

Circular map of the univariable correlation network of ECG markers to clinical and endocrine parameters. Shown are significant correlations (p < 0.05) only, and line thickness indicates the strength of negative (blue) or positive (red) correlation. Colors of circle segments indicate increased (red) or decreased values (blue), respectively, in thyrotoxicosis compared to hypothyroidism (outer ring) and higher (dark red) or lower values (green) in atrial fibrillation (inner ring).

Figure 3

Correlations of Tp-e interval (top) and JT interval (bottom) with endocrine parameters of thyroid homeostasis. Shown are single data points, linear models from Pearson regression with 95% confidence intervals and models of Spearman correlation (in the bottom of each panel).

Consistently with the results of group-wise hormone statistics (Table 2) and regression analysis the heart rate and markers of repolarization were significantly different between the four groups (Table 3). The P wave duration did not differ among the groups. In minimal models of multivariable analysis markers of thyroid homeostasis remained predictors of electrophysiological parameters after adjustment for medication, and they were the only predictors of Tp-e and JT intervals after step-wise reduction (Table 4).

Table 3

| Group 0 (normal subjects) | Group 1 (hypothyroidism) | Group 2 (full-dose L-T4 substitution therapy) | Group 3 (thyrotoxicosis) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (min−1) | 75 ± 5††† | 71 ± 6†††† | 77 ± 3†††† | 100 ± 3**** |

| QT interval (ms) | 362 ± 12*† | 399 ± 9†††† | 368 ± 8*†† | 330 ± 5**** |

| Tp-e interval (ms) | 73 ± 3 | 83 ± 4† | 73 ± 3 | 70 ± 2* |

| JT interval (ms) | 280 ± 13†† | 297 ± 9†††† | 278 ± 8††† | 241 ± 5**** |

| P wave duration (ms) | 94 ± 4 | 96 ± 4 | 92 ± 3 | 93 ± 2 |

Heart rhythm characteristics in the four groups.

Corrected p < 0.05 (*), < 1e4 (****) compared to group 1. Corrected p < 0.05 (†), < 0.01 (††), < 0.001 (†††), < 1e−4 (††††) compared to group 3.

Table 4

| B | SE | Wald | d.f. | p | OR (95% CI) | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (min −1 ) | |||||||

| FT4 (pmol/L)* | 12.92 | 2.06 | 39.2 | 1 | 1.1e−8 | 4.1e5 (7143–2.3e7) | 1.02 |

| Selective | 8.25 | 3.91 | 4.4 | 1 | 0.04 | 3832.8 (1.8–8.2e6) | 1.02 |

| beta-blocker | |||||||

| QT interval (ms) | |||||||

| TSH (mIU/L)* | 4.96 | 1.82 | 7.5 | 1 | 0.008 | 142.5 (4.1–5004.9) | 2.42 |

| FT3 (pmol/L)* | −18.97 | 7.29 | 6.8 | 1 | 0.01 | 5.8e−9 (3.6e−15–9.3e−3) | 2.41 |

| Amiodarone | 34.88 | 13.16 | 7.0 | 1 | 0.009 | 1.4e15 (8900.1–2.2e26) | 1.03 |

| Tp-e interval (ms) | |||||||

| TSH (mIU/L)* | 1.39 | 0.43 | 10.2 | 1 | 0.002 | 4.0 (1.7–9.4) | N/A |

| JT interval (ms) | |||||||

| TSH (mIU/L)* | 4.18 | 1.73 | 5.8 | 1 | 0.02 | 65.4 (2.2–1953) | 2.36 |

| FT3 (pmol/L)* | −16.32 | 6.98 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.02 | 8.1e−8 (9.4e−14–0.07) | 2.36 |

Minimal models of multivariable regression.

Variables were chosen by a priori selection and step-wise model simplification as described in the Methods section. Initial maximal models included BMI, medication (selective and unselective beta blockers, amiodarone, antihistamines) and serum concentrations of TSH, FT4, FT3, calcium, and creatinine. B, Beta coefficient; SE, standard error; Wald, Chi-squared from Wald's test; d.f., degrees of freedom; OR, odds ratio; VIF, variance inflation factor.

Logarithmically transformed to account for asymmetrical distribution.

Discussion

In this study we investigated a potential relationship between thyroid function and several markers of cardiac repolarization. The data reveal a robust association of heart rate and several time constants in the resting ECG, especially of the JT interval, to thyroid function. This connection is stronger than that to other physiological predictors of heart rhythm including BMI, renal function and serum electrolytes. With respect to heart rate and QT interval, biomarkers of thyroid homeostasis remained significant predictors of cardiac electrophysiology in minimal multivariable regression models adjusting for antiarrhythmic medication including selective betablockers and amiodarone. Step-wise model simplification arrived at the elimination of all predictors except TSH and/or FT3 for Tp-e and JT intervals, so that these ECG constants are explained by thyroid function only.

Subjects in group 2 were slightly younger than in the other groups. The difference wasn't significant, however, nor did the age correlate to TSH concentration, thyroid hormone concentration, heart rate, TPE interval or JT interval. We therefore don't expect the results to be distorted by age.

Unlike previous studies our observations extend to overt thyroid abnormalities, too. Our findings indicate a positive correlation of Tp-e and JT intervals to TSH concentration and an inverse correlation to FT4 and FT3 serum concentrations as well as to thyroid's secretory capacity (SPINA-GT).

The correlations on the level of current hormone concentrations are also reflected by consistent associations to diagnostic groups. The Tp-e and JT intervals were elevated in the hypothyroid and reduced in the thyrotoxic group. This also applied to the QT interval, whereas the heart rate showed an inverse association to the functional categories. Heart rate and time intervals were identical in euthyroid subjects (group 0) and patients receiving full-dose substitution therapy with levothyroxine (group 2), rendering them biochemically euthyroid. This observation indicates that the observed effects on ECG parameters are causally mediated by thyroid hormone concentration and not by accompanying effects of thyroid function, including nerval damage or impaired calcium homeostasis in the postoperative state, or autoimmunity.

An overt hypothyroid status results in a prolongation of cardiac repolarization. Overt hypothyroidism is accompanied by an excess of mortality of up to 34% in 5 years as long as the underlying thyroid hormone disorder is untreated or undertreated (27). Whereas, the reason for increased mortality in affected patients was discussed to be caused by comorbidities and frailty (27, 28) a large register-based study observed the mortality to be increased in subjects without comorbidities, too (29). The well-documented effects of thyroid hormones on myocardial physiology may explain the close association of cardiovascular morbidity to hypothyroidism. Overt hypothyroidism is able to induce heart failure via many effects including bradycardia, impaired systolic function, impaired left ventricular diastolic filling or diastolic hypertension (6). Although thyroid hormones have a strong impact on cardiac electrophysiology, the specific effects of overt hypothyroidism on novel repolarization markers have not been extensively studied up to now. Our observations demonstrate that the hypothyroid group, in addition to a decreased heart rate as expected, is hallmarked by significantly prolonged Tp-e and JT intervals, which are established markers for increased mortality risk. Therefore, major adverse cardiovascular endpoints in patients with overt hypothyroidism might as well result from arrhythmic events driven by repolarization abnormalities.

Previous studies arrived at conflicting results regarding the association of cardiac repolarization with thyroid function in the range of high T3 or T4 concentrations. Some reports described prolonged time constants of repolarization in thyrotoxicosis (14, 16, 30), whereas others reported an inverse association of repolarization intervals with thyroid hormones (15, 17). Our results, based on the whole range of thyroid function, including hypothyroid, euthyroid and hyperthyroid subjects, suggest a uniform inverse correlation of repolarization constants, especially the Tp-e and JT intervals, to thyroid hormones.

Cardiac repolarization or ventricular dispersion results from an interplay of ionic potassium currents, which are influenced by beta-adrenergic stimulation, depending particularly on the expression of beta-adrenoreceptors (31, 32). Kang et al. demonstrated potassium channels in human left ventricular tissue to be modulated by beta-adrenoceptors. Beta-adrenergic stimulation led to increased transmural dispersion of repolarization, resulting in elevated arrhythmogenic risk (31). Likewise, imbalances of sympathetic and vagal tone in hyperthyroidism and TSH-suppressive therapy were promotive for increased QT dispersion (33). Interestingly, increased dispersion of the QT interval was also observed in hypothyroidism (34), Akin et al. suggesting a U-shaped relationship between thyroid hormones and certain markers of cardiac electrophysiology.

Of note, thyroid hormones are able to modulate the susceptibility of the heart for catecholamines by stimulating the expression of beta-adrenoceptors in cardiomyocytes, with subsequent positive inotropic and chronotropic effects (35–38). Conversely, intracellular cAMP formed by activated beta-adrenoceptors is able to stimulate the expression of a number of genes including that of type 2 deiodinase (DIO2), which converts T4–T3 and 3,5-T2, i.e., to more active thyroid hormones (39). The resulting latch-like behavior of cardiomyocytes leads to bifurcation, i.e., a radically different response to catecholamines in situations of even slightly elevated thyroid hormone concentration.

Bosch et al. previously described a delay of repolarization in hypothyroidism to be mediated by decreasing potassium channel currents in the ventricular tissue of guinea pig hearts (40). Conversely, thyrotoxicosis is expected to trigger shortened cardiac repolarization. This would be in accordance with our results and prior studies (15, 17, 22).

In addition to the well-recognized thyroid hormones FT4 or FT3 even TSH can affect cardiac repolarization via TSH-receptors (TSHR) on cardiomyocytes by modulating potassium and calcium channel currents (41). Additionally, cAMP formed by TSHR activation may contribute to local hyperdeiodination and activation of the above-mentioned latch-like response.

Therefore, the distinct effects of thyrotropin and thyroid hormones on ventricular dispersion and its interaction with ionic currents via modulation of beta-adrenoceptors seem to be part of a complex scenario. Since both elevated iodothyronine and TSH concentrations are able to contribute to bifurcation, one might assume a U-shaped relationship between thyroid function and certain electrophysiological constants (5, 8). In our observations covering the whole range of thyroid function we didn't obtain, however, any hint for a U-shaped relationship. The increased risk of SCD in patients with high-normal FT4 concentration or thyrotoxicosis seems to be driven by mechanisms different from abnormalities in repolarization. This conclusion is also underscored by the fact that we saw in the thyrotoxic group only a moderate correlation of FT3 concentration to heart rate and the QT interval, but no correlations to other repolarization markers nor any correlations for other functional thyroid parameters (Supplementary Table 21).

Limitations of our approach are in the comparably small sample size and in the fact that subjects were recruited based on routine investigations, so that we were unable to determine non-classical thyroid hormones including 3,5-diiodothyronine (3,5-T2), thyronamines and iodothyroacetates, which may have a strong impact on cardiovascular physiology (42–44). Furthermore, our ECGs were not obtained digitally so that automatic measurements with a higher accuracy than the manual method could not be performed.

Strengths include multivariable modeling including medication, calcium and creatinine concentration, the evaluation of previously under-recognized biomarkers of cardiac electrophysiology and of calculated structure parameters of thyroid homeostasis, the determination of biologically more active free thyroid hormones and the inclusion of subjects from a broad range of thyroid function.

Motivated by previously observed but still poorly understood associations of SCD to within-reference range variations of thyroid hormone concentrations (3, 9–11), our research aimed at unveiling possible relationships between cardiac repolarization and derailed thyroid function. Our observations suggest that pathological repolarization might contribute to increased mortality in hypothyroidism. In thyrotoxicosis, however, the pathophysiology of major adverse cardiovascular end points seems to be mediated by mechanisms beyond repolarization.

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty at the Ruhr University of Bochum under the file number 3718-10.

Author contributions

AA, JD, AM, IA, and IE-B made substantial contributions to the study conception and design and to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AA and JD performed the statistical analysis. FS, PP, DS, GL-M, HB, and MG organized the database. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2021.738517/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Doshi R Dhawan T Rendon C Rodriguez MA Nutakki K Gianopulos J et al . New-onset arrhythmia associated with patients hospitalized for thyroid dysfunction. Heart Lung. (2020) 49:758–62. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.08.023

2.

Fitzgerald SP Bean NG Falhammar H Tuke J . Clinical parameters are more likely to be associated with thyroid hormone levels than with thyrotropin levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. (2020) 30:1695–709. 10.1089/thy.2019.0535

3.

Tribulova N Kurahara LH Hlivak P Hirano K Szeiffova Bacova B . Pro-arrhythmic signaling of thyroid hormones and its relevance in subclinical hyperthyroidism. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:2844. 10.3390/ijms21082844

4.

Gencer B Collet TH Virgini V Bauer DC Gussekloo J Cappola AR et al . Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk of heart failure events: an individual participant data analysis from 6 prospective cohorts. Circulation. (2012) 126:1040–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096024

5.

Kannan L Shaw PA Morley MP Brandimarto J Fang JC Sweitzer NK et al . Thyroid dysfunction in heart failure and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. (2018) 11:e005266. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005266

6.

Biondi B . Mechanisms in endocrinology: heart failure and thyroid dysfunction. Eur J Endocrinol. (2012) 167:609–18. 10.1530/EJE-12-0627

7.

Klein I Danzi S . Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. (2007) 116:1725–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678326

8.

Zhang Y Post WS Cheng A Blasco-Colmenares E Tomaselli GF Guallar E . Thyroid hormones and electrocardiographic parameters: findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e59489. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059489

9.

Chaker L van den Berg ME Niemeijer MN Franco OH Dehghan A Hofman A et al . Thyroid function and sudden cardiac death: a prospective population-based cohort study. Circulation. (2016) 134:713–22. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020789

10.

Müller P Dietrich JW Lin T Bejinariu A Binnebößel S Bergen F et al . Usefulness of serum free thyroxine concentration to predict ventricular arrhythmia risk in euthyroid patients with structural heart disease. Am J Cardiol. (2020) 125:1162–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.01.019

11.

Aweimer A El-Battrawy I Akin I Borggrefe M Mügge A Patsalis PC et al . Abnormal thyroid function is common in takotsubo syndrome and depends on two distinct mechanisms: results of a multicentre observational study. J Intern Med. (2021) 289:675–87. 10.1111/joim.13189

12.

Wellens HJ Schwartz PJ Lindemans FW Buxton AE Goldberger JJ Hohnloser SH et al . Risk stratification for sudden cardiac death: current status and challenges for the future. Eur Heart J. (2014) 35:1642–51. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu176

13.

Narayanan K Chugh SS . The 12-lead electrocardiogram and risk of sudden death: current utility and future prospects. Europace. (2015) 17(Suppl. 2):ii7–13. 10.1093/europace/euv121

14.

Colzani RM Emdin M Conforti F Passino C Scarlattini M Iervasi G . Hyperthyroidism is associated with lengthening of ventricular repolarization. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2001) 55:27–32. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01295.x

15.

Dörr M Ruppert J Robinson DM Kors JA Felix SB Völzke H . The relation of thyroid function and ventricular repolarization: decreased serum thyrotropin levels are associated with short rate-adjusted QT intervals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2006) 91:4938–42. 10.1210/jc.2006-1017

16.

Owecki M Michalak A Nikisch E Sowiński J . Prolonged ventricular repolarization measured by corrected QT interval (QTc) in subclinical hyperthyroidism. Horm Metab Res. (2006) 38:44–7. 10.1055/s-2006-924977

17.

Galetta F Franzoni F Fallahi P Tocchini L Braccini L Santoro G Antonelli A . Changes in heart rate variability and QT dispersion in patients with overt hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. (2008) 158:85–90. 10.1530/EJE-07-0357

18.

Madhukar R Jagadeesh AT Moey MYY Vaglio M Badilini F Leban M et al . Association of thyroid-stimulating hormone with corrected QT interval variation: a prospective cohort study among patients with type 2 diabetes. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. (2021). 10.1016/j.acvd.2021.06.008. [Epub ahead of print].

19.

Kors JA . Ritsema van Eck HJ, van Herpen G. The meaning of the Tp-Te interval and its diagnostic value. J Electrocardiol. (2008) 41:575–80. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2008.07.030

20.

Watanabe N Kobayashi Y Tanno K Miyoshi F Asano T Kawamura M et al . Transmural dispersion of repolarization and ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Electrocardiol. (2004) 37:191–200. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.02.002

21.

Panikkath R Reinier K Uy-Evanado A Teodorescu C Hattenhauer J Mariani R et al . Prolonged Tpeak-to-Tend interval on the resting ECG is associated with increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2011) 4:441–7. 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.960658

22.

Gürdal A Eroglu H Helvaci F Sümerkan MÇ Kasali K Çetin S et al . Evaluation of Tp-e interval, Tp-e/QT ratio and Tp-e/QTc ratio in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. (2017) 8:25–32. 10.1177/2042018816684423

23.

Dietrich JW Landgrafe-Mende G Wiora E Chatzitomaris A Klein HH Midgley JE et al . Calculated parameters of thyroid homeostasis: emerging tools for differential diagnosis and clinical research. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2016) 7:57. 10.3389/fendo.2016.00057

24.

Rosenthal TM Masvidal D Abi Samra FM Bernard ML Khatib S Polin GM et al . Optimal method of measuring the T-peak to T-end interval for risk stratification in primary prevention. Europace. (2017) 20:698–705. 10.1093/europace/euw430

25.

Postema PG Wilde AA . The measurement of the QT interval. Curr Cardiol Rev. (2014) 10:287–9410.2174/1573403X10666140514103612

26.

Hoermann R Midgley JEM Larisch R Dietrich JW . Lessons from randomised clinical trials for triiodothyronine treatment of hypothyroidism: have they achieved their objectives?J Thyroid Res. (2018) 2018:3239197. 10.1155/2018/3239197

27.

Laulund AS Nybo M Brix TH Abrahamsen B Jørgensen HL Hegedüs L . Duration of thyroid dysfunction correlates with all-cause mortality. The OPENTHYRO Register Cohort. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e110437. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110437

28.

Lillevang-Johansen M Abrahamsen B Jørgensen HL Brix TH Hegedüs L . Over- and under-treatment of hypothyroidism is associated with excess mortality: a register-based cohort study. Thyroid. (2018) 28:566–74. 10.1089/thy.2017.0517

29.

Thvilum M Brandt F Almind D Christensen K Hegedüs L Brix TH . Excess mortality in patients diagnosed with hypothyroidism: a nationwide cohort study of singletons and twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2013) 98:1069–75. 10.1210/jc.2012-3375

30.

Lee YS Choi JW Bae EJ Park WI Lee HJ Oh PS . The corrected QT (QTc) prolongation in hyperthyroidism and the association of thyroid hormone with the QTc interval. Korean J Pediatr. (2015) 58:263–6. 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.7.263

31.

Banyasz T Jian Z Horvath B Khabbaz S Izu LT Chen-Izu Y . Beta-adrenergic stimulation reverses the I Kr-I Ks dominant pattern during cardiac action potential. Pflugers Arch. (2014) 466:2067–76. 10.1007/s00424-014-1465-7

32.

Kang C Badiceanu A Brennan JA Gloschat C Qiao Y Trayanova NA et al . β-adrenergic stimulation augments transmural dispersion of repolarization via modulation of delayed rectifier currents IKs and IKr in the human ventricle. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:15922. 10.1038/s41598-017-16218-3

33.

Liu C Lv H Li Q Fu S Tan J Wang C et al . Effect of thyrotropin suppressive therapy on heart rate variability and QT dispersion in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e21190. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021190

34.

Akin A Unal E Yildirim R Ture M Balik H Haspolat YK . Evaluation of QT dispersion and Tp-e interval in children with subclinical hypothyroidism. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2018) 41:372–5. 10.1111/pace.13286

35.

Bahouth SW . Thyroid hormones transcriptionally regulate the beta1-adrenergic receptor gene in cultured ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. (1991) 266:15863–9. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)98488-7

36.

Vassy R Yin YL Perret GY . Acute effect of T3 on beta-Adrenoceptors of CulturedChick Cardiac Myocytes. In: BravermanLEEberOLangstegerW, editors. Heart and Thyroid. Wien: Blackwell-MZV (1994). p. 165–8.

37.

Vassy R Nicolas P Yin YL Perret GY . Nongenomic effect of triiodothyronine on cell surface beta-adrenoceptors in cultured embryonic cardiac myocytes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. (1997) 214:352–8. 10.3181/00379727-214-44103

38.

Canaris GJ Manowitz NR Mayor G Ridgway EC . The colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. (2000) 160:526–34. 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526

39.

Bianco AC Maia AL da Silva WS Christoffolete MA . Adaptive activation of thyroid hormone and energy expenditure. Biosci Rep. (2005) 25:191–208. 10.1007/s10540-005-2885-6

40.

Bosch RF Wang Z Li GR Nattel S . Electrophysiological mechanisms by which hypothyroidism delays repolarization in guinea pig hearts. Am J Physiol. (1999) 277:H211–20. 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.1.H211

41.

Alonso H Fernández-Ruocco J Gallego M Malagueta-Vieira LL Rodríguez-de-Yurre A Medei E et al . Thyroid stimulating hormone directly modulates cardiac electrical activity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2015) 89:280–6. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.10.019

42.

Dietrich JW Müller P Schiedat F Schlömicher M Strauch J Chatzitomaris A et al . Nonthyroidal illness syndrome in cardiac illness involves elevated concentrations of 3,5-diiodothyronine and correlates with atrial remodeling. Eur Thyroid J. (2015) 4:129–37. 10.1159/000381543

43.

Hoermann R Midgley JE Larisch R Dietrich JW . Homeostatic control of the thyroid-pituitary axis: perspectives for diagnosis and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2015) 6:177. 10.3389/fendo.2015.00177

44.

Homuth G Lietzow J Schanze N Golchert J Köhrle J . Endocrine, Metabolic and Pharmacological Effects of Thyronamines (TAM), Thyroacetic Acids (TA) and Thyroid Hormone Metabolites (THM)–evidence from in vitro, cellular, experimental animal and human studies. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. (2020) 128:401–13. 10.1055/a-1139-9200

Summary

Keywords

repolarization, T-peak-to-end interval, JT interval, thyroid hormones, thyroid disorder and heart

Citation

Aweimer A, Schiedat F, Schöne D, Landgrafe-Mende G, Bogossian H, Mügge A, Patsalis PC, Gotzmann M, Akin I, El-Battrawy I and Dietrich JW (2021) Abnormal Cardiac Repolarization in Thyroid Diseases: Results of an Observational Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8:738517. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.738517

Received

08 July 2021

Accepted

12 October 2021

Published

23 November 2021

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Marina Cerrone, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, United States

Reviewed by

Johannes Steinfurt, University Heart Center Freiburg, Germany; Beatrice De Maria, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri (ICS Maugeri), Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Aweimer, Schiedat, Schöne, Landgrafe-Mende, Bogossian, Mügge, Patsalis, Gotzmann, Akin, El-Battrawy and Dietrich.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Assem Aweimer assem.aweimer@rub.de

This article was submitted to Cardiac Rhythmology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.