Abstract

Background: Few studies on the risk factors for postoperative continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in a homogeneous population of patients with acute type A aortic dissection (AAAD). This retrospective analysis aimed to investigate the risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality in the patients undergoing AAAD surgery and to discuss the perioperative comorbidities and short-term outcomes.

Methods: The study collected electronic medical records and laboratory data from 432 patients undergoing surgery for AAAD between March 2009 and June 2021. All the patients were divided into CRRT and non-CRRT groups; those in the CRRT group were divided into the survivor and non-survivor groups. The univariable and multivariable analyses were used to identify the independent risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality.

Results: The proportion of requiring CRRT and in-hospital mortality in the patients with CRRT was 14.6 and 46.0%, respectively. Baseline serum creatinine (SCr) [odds ratio (OR), 1.006], cystatin C (OR, 1.438), lung infection (OR, 2.292), second thoracotomy (OR, 5.185), diabetes mellitus (OR, 6.868), AKI stage 2–3 (OR, 22.901) were the independent risk factors for receiving CRRT. In-hospital mortality in the CRRT group (46%) was 4.6 times higher than in the non-CRRT group (10%). In the non-survivor (n = 29) and survivor (n = 34) groups, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III-IV (OR, 10.272, P = 0.019), lactic acidosis (OR, 10.224, P = 0.019) were the independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients receiving CRRT.

Conclusion: There was a high rate of CRRT requirement and high in-hospital mortality after AAAD surgery. The risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality in the patients undergoing AAAD surgery were determined to help identify the high-risk patients and make appropriate clinical decisions. Further randomized controlled studies are urgently needed to establish the risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is one of the most common postoperative complications following cardiac surgery and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (1). There is currently no consensus on the definition of cardiac surgery-associated AKI (CSA-AKI). The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes criteria (KDIGO) represent the current epidemiological and clinical standard for diagnosing AKI, including CSA-AKI (2, 3). Acute type A aortic dissection (AAAD) is the most dramatic emergency in cardiac surgery due to the high in-hospital mortality rate of ~26% (4). Compared with other heart surgeries, the risk of AKI is higher after aortic dissection surgery (5, 6). Between 1999 and 2008, the incidence of AKI and AKI requiring dialysis (AKI-D) after cardiac surgery has increased from 30 and 5% to 47 and 14%, respectively (7). Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is widely used for hemodynamically unstable patients with considerable fluid accumulation (3, 8). However, the mortality of receiving CRRT after AKI is 40–70% (9), and second, the high cost of CRRT and the limited medical resources associated with CRRT impose a heavy social burden (10). Early identification of critically ill patients of high risk for CRRT and in-hospital mortality after cardiac surgery can be beneficial in improving the overall prognosis.

Few studies on the risk factors for postoperative CRRT in a homogeneous population of patients with AAAD. This retrospective analysis was designed to describe the incidence of AKI requiring CRRT in the patients undergoing AAAD surgery, evaluate the demographic and perioperative factors associated with the patients with AKI requiring CRRT, identify the association of CRRT with a duration of mechanical ventilation, in-hospital mortality, and 1-year readmission, and analyze the risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

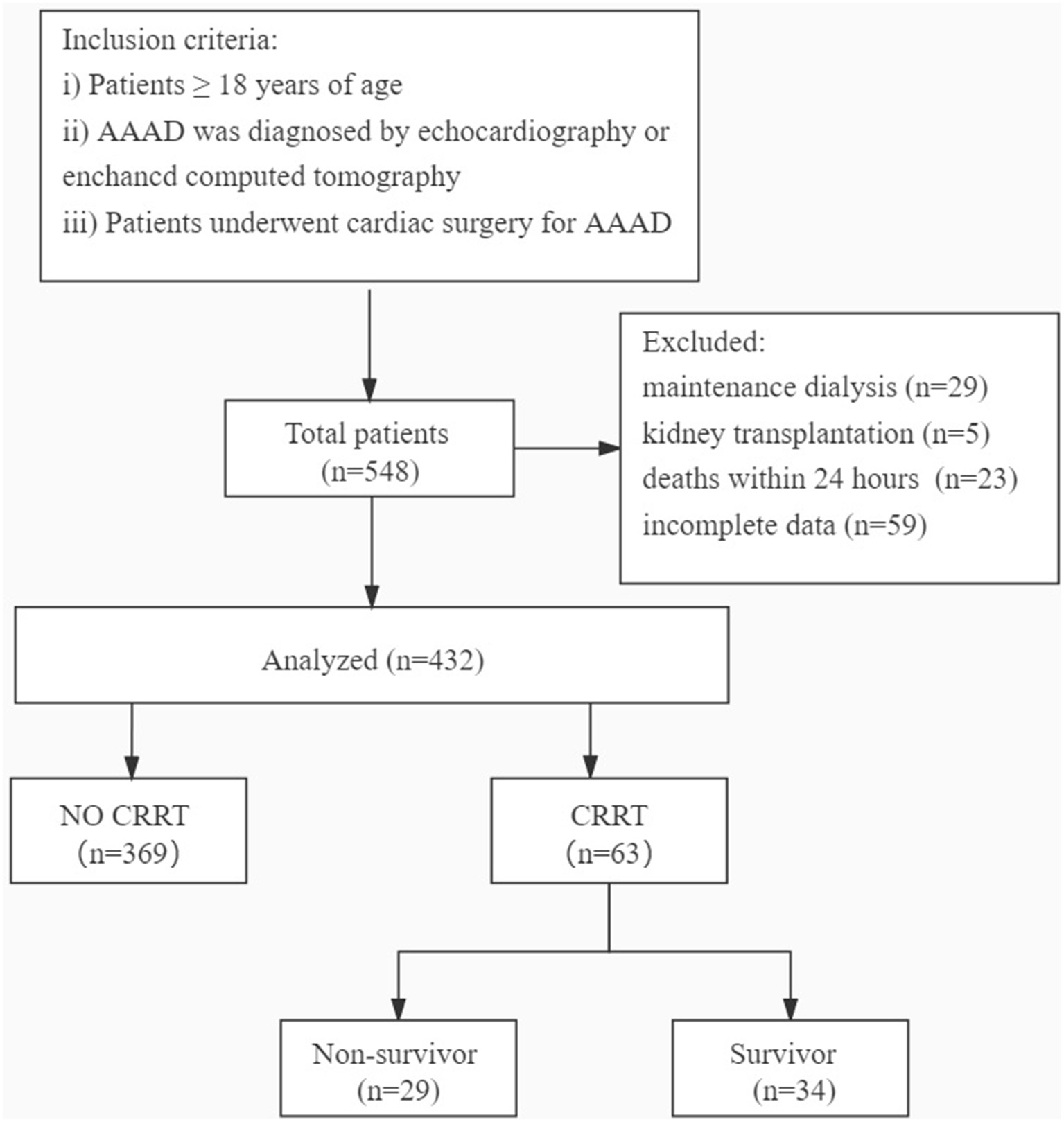

For this study, in Figure 1, we retrospectively collected the electronic medical records and laboratory results of 432 patients aged ≥18 years who underwent cardiac surgery for AAAD diagnosed by echocardiography or enhanced CT at the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Sichuan, China) between March 2009 and June 2021. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) the patients who had received maintenance dialysis within the last month or were on dialysis before surgery (n = 29); (ii) the patients who had received kidney transplantation (n = 5); (iii) the patients who died within 24 h of admission to the hospital (n = 23); and (iv) the patients with incomplete data (n = 59). The present study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Sichuan, China.

Figure 1

Flow diagram of the study.

Data Collection

The data of the patients included in the present study, including the patient characteristics, perioperative factors, laboratory data, postoperative complications or comorbidities, and outcomes, were extracted from the electronic medical records system of our institution. The laboratory data of the CRRT group were obtained prior to the occurrence of AKI.

Measurements and Variable Definitions

Acute kidney injury was defined according to the KDIGO criteria (2) as follows: a serum creatinine (SCr) levels increase of ≥0.3 mg/dl within 48 h, or ≥1.5-fold the baseline level, which is known or hypothesized to have occurred within the prior 7 days, or urine output <0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 consecutive h. AKI severity was staged according to the following criteria (2) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Stage | Serum creatinine | Urine output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5–1.9 times baseline | <0.5 ml/kg/h for 6–12 h |

| Or ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 mmol/l) increase | ||

| 2 | 2.0–2.9 times baseline | <0.5 ml/kg/h for ≥12 h |

| 3 | 3.0 times baseline | <0.3 ml/kg/h for ≥24 hOr anuria for ≥12 h |

| Or increase in serum creatinine to ≥4.0 mg/dl (≥353.6 mmol/l) | ||

| Or initiation of renal replacement therapy or in patients <18 years, decrease in eGFR to <35 ml/min per 1.73 m2 |

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) stages of acute kidney injury (AKI) according to serum creatinine (SCr) levels and urine output.

KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

In this retrospective analysis, the urine output criteria for defining AKI were not used, as 6- and 12-h urine outputs were not reliably recorded, and certain patients were treated with diuretics and CRRT. The decision for CRRT is determined by the assessment of the severity of AKI by the clinician and the comprehensive condition of patients. As some patients with AAAD were referred to our hospital from other hospitals, the lowest SCr level in the 2 days prior to admission was used as the baseline level if data were available; if not, we considered the first SCr available at admission as the baseline value. Drinking is defined as having consumed alcohol at least one time a week in the last year. CKD was defined by past medical history. Preoperative liver insufficiency was defined as a preoperative elevation of >80 U/L of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or (and) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in the patients. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) is a measure to protect the brain by arresting extracorporeal circulation after cooling the brain temperature to 14.1–20°C in aortic arch replacement, for brain preservation. The diagnosis of postoperative acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was based on a history of typical chest pain, diagnostic ECG changes, serum cardiac biomarkers, and abnormalities on echocardiography and coronary angiography. Cerebral ischemia or hemorrhage resulting in complete or incomplete loss of brain function was defined as an acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA).

The patients were divided into the CRRT and non-CRRT groups according to whether they required CRRT or not; the patients in the CRRT group were divided into the survivor and non-survivor groups. The independent risk factors and perioperative complications and short-term outcomes were analyzed.

The primary outcomes were the occurrence of severe AKI, requiring CRRT, and in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes were the duration of mechanical ventilation, hospitalization costs, and 1-year re-admission.

Statistical Analysis

The baseline demographic and clinical data of patients were presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. The categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests. Data distribution normality was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and the non-normally distributed continuous variables were represented as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared accordingly using independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. A stepwise forward binary logistic regression analysis was applied to analyze the risk factors for patients receiving postoperative CRRT and in-hospital mortality. The omnibus tests of model coefficients were used to evaluate the multivariable binary logistic regression model, with P <0.05 indicating that the binary logistic regression model was generally significant. Hosmer and Lemeshow test and −2 log likelihood (−2LL) provided an evaluation of the goodness of fit of the logistic regression model, and P > 0.05 would indicate a good fit. Only those variables found to be statistically significant in the univariable analysis and with a variance inflation factor (VIF) <10 in the linear regression analysis were used in logistic regression analysis.

Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed by the SPSS software package, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 432 patients with AAAD were included in the final sample. The demographic and clinical characteristics and laboratory data of patients hospitalized with AAAD are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| ALL (n = 432) | No CRRT (n = 369) | CRRT (n = 63) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 48.19 ± 10.97 | 47.69 ± 10.59 | 51.10 ± 12.63 | 0.023 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Male | 341 (78.9%) | 285 (77.2%) | 56 (88.9%) | |

| Female | 91 (21.1%) | 84 (22.8%) | 7 (11.1%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 24.85 ± 3.78 | 24.84 ± 3.65 | 24.89 ± 4.53 | 0.916 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 210 (48.6%) | 181 (49.1%) | 29 (46.0%) | 0.658 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 136 (31.5%) | 122 (33.1%) | 14 (22.2%) | 0.087 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 250 (57.9%) | 209 (56.6%) | 41 (65.1%) | 0.210 |

| Poor blood pressure control | 92 (21.3%) | 72 (19.5%) | 20 (31.7%) | 0.028 |

| A left ventricular ejection fraction of <35% | 28 (6.5%) | 22 (6.0%) | 6 (9.5%) | 0.289 |

| Marfan syndrome | 18 (4.2%) | 14 (3.8%) | 4 (6.3%) | 0.348 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 27 (6.3%) | 23 (6.2%) | 4 (6.3%) | 0.972 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 176 (40.7%) | 150 (40.7%) | 26 (41.3%) | 0.926 |

| CKD | 30 (6.9%) | 22 (6.0%) | 8 (12.7%) | 0.052 |

| COPD | 28 (6.5%) | 21 (5.7%) | 7 (11.1%) | 0.106 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (4.6%) | 11 (3.0%) | 9 (14.3%) | 0.000 |

| Chronic liver disease | 22 (5.1%) | 18 (4.9%) | 4 (6.3%) | 0.624 |

| Preoperative factors | ||||

| Hemorrhagic shock, n (%) | 7 (1.6%) | 4 (1.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0.094 |

| Pericardial tamponade, n (%) | 20 (4.6%) | 17 (4.6%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0.957 |

| NYHA class III-IV, n (%) | 111 (25.7%) | 85 (23.0%) | 26 (41.3%) | 0.002 |

| Liver insufficiency, n (%) | 51 (11.8%) | 36 (9.8%) | 15 (23.8%) | 0.001 |

| Renal artery involvement, n (%) | 184 (42.6%) | 154 (41.7%) | 30 (47.6%) | 0.383 |

| Renal malperfusion, n (%) | 103 (23.8%) | 83 (22.5%) | 20 (31.7%) | 0.113 |

| No renal malperfusion, n (%) | 81 (18.8%) | 71 (19.2%) | 10 (15.9%) | 0.527 |

| Lab data (mean ± SD) or median (IQR) | ||||

| Baseline SCr, μmol/L | 82 (65, 104) | 79 (64, 99) | 97 (83, 131) | 0.000 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 6.32 (4.95, 8.60) | 6.15 (4.90, 8.30) | 7.50 (5.76, 11.41) | 0.000 |

| UA, umol/L | 353 (280, 442) | 349 (276, 430) | 405 (301, 480) | 0.047 |

| Cys-C, mg/L | 1.30 (0.92, 2.08) | 1.2 (0.90, 1.73) | 3.11 (1.54, 4.22) | 0.000 |

| ALB, g/L | 37.90 (34.23, 41.10) | 38.10 (34.35, 41.15) | 36.10 (30.90, 40.30) | 0.056 |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | 178 (41.2%) | 142 (38.5%) | 36 (57.1%) | 0.005 |

| Hematuria, n (%) | 123 (28.5%) | 104 (28.2%) | 19 (30.2%) | 0.748 |

Demographics, preoperative factors, and laboratory data of 432 patients.

The continuous variables that follow a normal distribution include age, and BMI which were expressed as mean ± SD. The continuous variables that do not follow a normal distribution were represented as median and IQR. The categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Liver insufficiency was defined as a preoperative elevation of >80 U/L of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or (and) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in patients.

AKI, acute kidney injury; Scr, serum creatinine; SD, standard deviations; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DHCA, Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ALB, albumin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; UA, uric acid; Cys-C, cystatin C; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy. Bold values represented P <0.05.

The mean age of all patients included in the study was 48.19 ± 10.97 years. The median body mass index (BMI) was 24.85 ± 3.78 kg/m2. There were 250 (57.9%) patients with hypertension and 92 (21.3%) with poor blood pressure control. A small number of patients had chronic kidney injury (CKD, 6.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, 6.5%), diabetes (4.6%), chronic liver disease (5.1%), and other comorbidities. The median of baseline SCr level was 82 (65, 104) μmol/L. The median of cystatin C (Cys-C) level was 1.30 (0.92, 2.08) mg/L. According to aortic computed tomography angiography (CTA) findings, 184 patients were diagnosed with renal artery involvement, 103 of which had coexisting renal malperfusion.

Primary and Second Outcomes of Patients With AAAD

Among the recorded patients, 47.9% developed postoperative severe AKI (AKI stages 2–3). The total number of in-hospital mortality and requiring for CRRT was 66 (15.3%) and 63 (14.6%), respectively. In-hospital mortality in the CRRT group (46%) was 4.6 times higher than in the non-CRRT group (10%). Compared with the non-CRRT group, the CRRT group had a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and higher hospitalization costs. No statistical difference was observed in the 1-year readmission rate between the two groups (P = 0.762) (Table 3).

Table 3

| ALL (n = 432) | Non-CRRT (n = 369) | CRRT (n = 63) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interoperative factors | ||||

| Total aortic arch replacement n (%) | 319 (73.8%) | 270 (73.2%) | 49 (77.8%) | 0.442 |

| DHCA n (%) | 105 (24.3%) | 93 (25.2%) | 12 (19.0%) | 0.292 |

| CPB duration ≥180 min n (%) | 387 (89.6%) | 336 (91.1%) | 51 (81.0%) | 0.015 |

| RBC transfusion (units) | 3.0 (1.0, 4.5) | 3.0 (0.0, 4.0) | 3.5 (2.0, 5.5) | 0.150 |

| Postoperative comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| MAP within 2 h after surgery ≤ 65 mmHg | 94 (21.8%) | 67 (18.2%) | 27 (42.9%) | 0.000 |

| Second thoracotomy | 22 (5.1%) | 11 (3.0%) | 11 (17.5%) | 0.000 |

| AMI | 14 (3.2%) | 8 (2.2%) | 6 (9.5%) | 0.002 |

| CVA | 39 (9.0%) | 32 (8.7%) | 7 (11.1%) | 0.532 |

| Lung infection | 132 (30.6%) | 94 (25.5%) | 38 (60.3%) | 0.000 |

| Lactic acidosis | 104 (24.1%) | 79 (21.4%) | 25 (39.7%) | 0.002 |

| ARDS | 65 (15.0%) | 50 (13.6%) | 15 (23.8%) | 0.035 |

| Hepatic failure | 40 (9.3%) | 29 (7.9%) | 11 (17.5%) | 0.015 |

| AKI stage 2–3 | 207 (47.9%) | 146 (39.6%) | 61 (96.8%) | 0.000 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | 4 (2, 6) | 3 (2, 5) | 7 (5, 14) | 0.000 |

| Hospitalization costs, $ | 30410.21 (24734.17, 39734.99) | 29635.79 (24052.40, 36689.51) | 41147.65 (33731.50, 49527.07) | 0.000 |

| 1-year re-admission n (%) | 53 (12.3%) | 46 (12.5%) | 7 (11.1%) | 0.762 |

| In-hospital mortality n (%) | 66 (15.3%) | 37 (10.0%) | 29 (46.0%) | 0.000 |

Interoperative factors, postoperative comorbidities, and outcomes of 432 patients.

The continuous variables and categorical variables were presented as mean ± SD, median and IQR, numbers and percentages, respectively. AKI, acute kidney injury; Scr, serum creatinine; SD, standard deviations; DHCA, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MAP, mean arterial pressure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CVA, acute cerebrovascular accident; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy. Bold values represented P <0.05.

$ Represents United States Dollar (USD).

Risk Factors for Postoperative AKI With CRRT in Patients With AAAD

The multivariable analysis revealed baseline SCr [odds ratio (OR), 1.006; P = 0.011], Cys-C (OR, 1.438; P = 0.001), lung infection (OR, 2.292; P = 0.017), second thoracotomy (OR, 5.185; P = 0.004), diabetes mellitus (OR, 6.868; P = 0.001), AKI stage 2–3 (OR, 22.901; P = 0.000) were the independent risk factors for receiving CRRT (Table 4).

Table 4

| Variables | β | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Baseline SCr | 0.006 | 1.006 | 1.001 | 1.011 | 0.011 |

| Cys-C | 0.364 | 1.438 | 1.167 | 1.774 | 0.001 |

| Lung infection | 0.829 | 2.292 | 1.157 | 4.539 | 0.017 |

| Second thoracotomy | 1.646 | 5.185 | 1.700 | 15.814 | 0.004 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.927 | 6.868 | 2.182 | 21.621 | 0.001 |

| AKI stage 2–3 | 3.131 | 22.901 | 5.220 | 100.466 | 0.000 |

A multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).

Age, gender, poor blood pressure control, diabetes mellitus, NYHA class III–IV, liver insufficiency, baseline SCr, Cys-C, BUN, UA, proteinuria, MAP within 2 h after surgery ≤ 65 mmHg, second thoracotomy, AMI, lung infection, lactic acidosis, ARDS, hepatic failure, AKI stage 2–3 were included to establish a stepwise forward binary logistic regression (Omnibus tests of model coefficients: X2 = 137.693, P = 0.000; Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test: X2 = 6.711, P = 0.568; −2 log likelihood = 221.224). In the linear regression analysis of these variables, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was <10. Therefore, there were no problems of multicollinearity among these independent variables. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were measured through binary logistic regression. The OR of the continuous variable represented that for a single unit increase, the probability of a positive event will increase by approximately OR-1 times.

NYHA, New York Heart Association; PLT, platelet; ALB, albumin; SCr, serum creatinine; Cys-C, cystatin C; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MAP, mean arterial pressure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; AKI, acute kidney injury. Bold values represented P <0.05.

Risk Factors for In-hospital Mortality in Patients With CRRT After Surgery for AAAD

In this study, 63 patients with CRRT were divided into the survivor (34/63, 54.0%) and non-survivor groups (29/63, 46.0%). The characteristics, perioperative factors, laboratory data, and outcomes of the patients with CRRT are shown in Table 5. In the non-survivors and survivors groups, there were statistically significant differences in the history of drinking (41.4 vs. 5.9%), preoperative NYHA class III-IV (75.9 vs. 11.8%), cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) duration ≥ 180 min (93.1 vs. 70.6%), duration of mechanical ventilation (16.5 vs. 10 days), MAP ≤ 65 mmHg within 2 h postoperatively (62.1 vs. 26.5%), hepatic failure (34.5 vs. 2.9%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (37.9 vs. 11.8%), lactic acidosis (62.1 vs. 20.6%), and CVA (20.7 vs. 2.9%).

Table 5

| ALL (n = 63) | Non-survivor (n = 29) | Survivor (n = 34) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 51.10 ± 12.63 | 53.90 ± 12.48 | 48.71 ± 12.45 | 0.104 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.326 | |||

| Male | 56 (88.9%) | 27 (93.1%) | 29 (85.3%) | |

| Female | 7 (11.1%) | 2 (6.9%) | 5 (14.7%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.06 (22.49, 27.17) | 25.06 (22.49, 27.78) | 24.86 (22.91, 26.45) | 0.610 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 29 (46%) | 14 (48.3%) | 15 (44.1%) | 0.741 |

| Drinking | 14 (22.2%) | 12 (41.4%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.001 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 41 (65.1%) | 19 (65.5%) | 22 (64.7%) | 0.946 |

| Poor blood pressure control | 20 (31.7%) | 11 (37.9%) | 9 (26.5%) | 0.330 |

| A left ventricular ejection fraction of <35% | 6 (9.5%) | 5 (17.2%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.054 |

| Marfan syndrome | 4 (6.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0.383 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 4 (6.3%) | 3 (10.3%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.230 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 26 (41.3%) | 8 (27.6%) | 18 (52.9%) | 0.042 |

| CKD | 8 (12.7%) | 2 (6.9%) | 6 (17.6%) | 0.201 |

| COPD | 7 (11.1%) | 4 (13.8%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0.532 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (14.3%) | 6 (20.7%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0.180 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 (6.3%) | 2 (6.9%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.869 |

| Preoperative factors | ||||

| Hemorrhagic shock, n (%) | 3 (4.8%) | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1.000 |

| Pericardial tamponade, n (%) | 3 (4.8%) | 2 (6.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.590 |

| NYHA class III-IV n (%) | 26 (41.3%) | 22 (75.9%) | 4 (11.8%) | 0.000 |

| Liver insufficiency, n (%) | 15 (23.8%) | 10 (34.5%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0.066 |

| Renal artery involvement, n (%) | 30 (42.7%) | 13 (44.8%) | 17 (50.0%) | 0.682 |

| Renal malperfusion, n (%) | 20 (31.7%) | 7 (24.1%) | 13 (38.2%) | 0.231 |

| No renal malperfusion, n (%) | 10 (15.9%) | 6 (20.7%) | 4 (11.8%) | 0.492 |

| Lab data (mean ± SD) or median (IQR) | ||||

| Baseline Scr, μmol/L | 97 (83, 131) | 97 (86, 111) | 98 (72, 160) | 0.720 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 7.5 (5.76, 11.41) | 8.09 (5.92, 10.75) | 7.40 (5.58, 11.70) | 0.901 |

| UA, umol/L | 390.54 ± 129.90 | 380.25 ± 125.79 | 399.31 ± 134.55 | 0.566 |

| Cys-C, mg/L | 3.11 (1.54, 4.22) | 2.95 (1.87, 4.15) | 3.28 (1.09, 4.33) | 0.940 |

| ALB, g/L | 36.10 (30.90, 40.30) | 36.10 (30.70, 40.80) | 36.10 (30.67, 40.23) | 0.730 |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | 36 (57.1%) | 14 (48.3%) | 22 (64.7%) | 0.189 |

| Hematuria, n (%) | 19 (30.2%) | 9 (31.0%) | 10 (29.4%) | 0.889 |

| Interoperative factors | ||||

| Total aortic arch replacement n (%) | 49 (77.8%) | 21 (72.4%) | 28 (82.4%) | 0.344 |

| DHCA n (%) | 12 (19.0%) | 6 (20.7%) | 6 (17.6%) | 0.759 |

| CPB duration ≥180 min n (%) | 51 (81.0%) | 27 (93.1%) | 24 (70.6%) | 0.023 |

| RBC transfusion (units) | 3.5 (3.0, 5.5) | 3.0 (1.8, 5.5) | 3.8 (2.0, 5.6) | 0.527 |

| Postoperative comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| MAP within 2 h after surgery ≤ 65 mmHg | 27 (42.9%) | 18 (62.1%) | 9 (26.5%) | 0.004 |

| Second thoracotomy | 11 (17.5%) | 5 (17.2%) | 6 (17.6%) | 0.966 |

| AMI | 6 (9.5%) | 4 (13.8%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.286 |

| Lung infection | 38 (60.3%) | 21 (72.4%) | 17 (50.0%) | 0.070 |

| Hepatic failure | 11 (17.5%) | 10 (34.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.001 |

| ARDS | 15 (23.8%) | 11 (37.9%) | 4 (11.8%) | 0.015 |

| Lactic acidosis | 25 (39.7%) | 18 (62.1%) | 7 (20.6%) | 0.001 |

| CVA | 7 (11.1%) | 6 (20.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.042 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Hospitalization costs, $ | 41276.87 ± 14961.75 | 42604.69 ± 15729.64 | 40144.32 ± 14414.22 | 0.520 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | 7 (5, 14) | 16.5 (9, 21) | 10 (6, 20) | 0.049 |

Demographics, perioperative factors, and outcomes of 63 patients with CRRT.

The continuous variables that follow a normal distribution include age, uric acid (UA), hospitalization costs were expressed as mean ± SD. The continuous variables that do not follow a normal distribution were represented as median and IQR. The categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Liver insufficiency was defined as a preoperative elevation of >80 U/L of AST or (and) ALT in the patients.

AKI, acute kidney injury; Scr, serum creatinine; SD, standard deviations; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DHCA, Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ALB, albumin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; UA, uric acid; Cys-C, cystatin C; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; DHCA, Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MAP, mean arterial pressure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CVA, acute cerebrovascular accident; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome. Bold values represented P <0.05. $Represents United States Dollar (USD).

In Table 6, the multivariable analysis showed that the independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality in the patients with CRRT included preoperative NYHA class III-IV (OR, 10.272; P = 0.019), lactic acidosis (OR, 10.224; P = 0.019). The patients with two or more predisposing factors including the history of drinking, CPB duration ≥ 180 min, MAP ≤ 65 mmHg within 2 h postoperatively, ARDS, hepatic failure, and acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA), were high-risk patients for in-hospital death in CRRT (OR, 19.816; P = 0.002).

Table 6

| Variables | β | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Lactic acidosis | 2.325 | 10.224 | 1.459 | 71.641 | 0.019 |

| NYHA class III-IV | 2.329 | 10.272 | 1.469 | 71.802 | 0.019 |

| Risk factors ≥ 2 including Drinking CPB duration ≥180 min MAP within 2 h after surgery ≤ 65 mmHg Hepatic failure ARDS CVA |

2.986 | 19.816 | 3.035 | 129.389 | 0.002 |

The multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in the patients with CRRT.

Drinking history, NYHA class III–IV, CPB duration ≥180 min, duration of mechanical ventilation, MAP within 2 h after surgery ≤ 65 mmHg, CVA, lactic acidosis, ARDS, and hepatic failure were included to establish a stepwise forward binary logistic regression (Omnibus tests of model coefficients: X2 = 48.417, P = 0.000; Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test: X2 = 0.640, P = 0.726; −2 log likelihood = 38.522). In the linear regression analysis of these variables, VIF was <10. There were no problems of multicollinearity among these independent variables. The OR and 95% CI were measured through binary logistic regression.

NYHA, New York Heart Association; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MAP, mean arterial pressure; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CVA, acute cerebrovascular accident. Bold values represented P <0.05.

Discussion

This is the first study of independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with CRRT in a homogenous population of patients with AAAD.

In our study with 432 patients, the incidence of severe AKI (AKI stages 2–3), the overall in-hospital mortality, the proportion for requiring CRRT, and in-hospital mortality after CRRT, was 47.9, 15.3, 14.6, and 46.0%, respectively. Our findings revealed that diabetes, SCr, secondary thoracotomy, pulmonary infection, and severe AKI were the independent risk factors for CRRT. Preoperative severe heart failure, postoperative lactic acidosis, and a combination of any three or more risk factors were the independent risk factors for death in the patients with CRRT. The patients in the CRRT group had longer postoperative mechanical ventilation, higher hospitalization costs, and higher in-hospital mortality. This study supports evidence from the previous observations that 11–27% of patients undergoing surgery for aortic dissection required renal replacement therapy (RRT) (11–13) and the mortality for CRRT was between 40 and 70% (9, 14).

In this study, diabetes was found to be considered as an independent risk factor for CRRT that was consistent with the data published by The Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT), who found that diabetes has become the most common initial diagnosis for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) treated with dialysis (15). This is associated with hyperglycemia causing relative ischemia in the kidney, systemic endothelial cell dysfunction (16), podocyte injury (17), and sterile inflammation, leading to kidney injury and deterioration of kidney function (18).

Pulmonary infection was also an independent risk factor for CRRT. Sepsis (19), non-severe pneumonia (20), can give rise to the development and exacerbation of AKI and an increased risk of death due to the inflammatory response and organ crosstalk between lung and kidney (21).

Our findings were in accord with the recent studies indicating that the baseline SCr levels, second thoracotomy were considered as the independent risk factors for CRRT (11, 22, 23). Increased creatinine levels represent impaired kidney function (24). The second thoracotomy is performed when excessive bleeding occurs, which may cause hypovolemia (22). Perioperative hypotension or poor organ perfusion may lead to deterioration of renal function (25, 26).

Several reports have shown that serum cystatin C is a good indicator for identifying early renal impairment and predicting RRT requirements (27–30). Our study confirms that an elevated Cys-C is an independent risk factor for predicting the CRRT. Since serum cystatin C is not affected by diet, etiology of AKI, or urine output, it is a useful and highly diagnostic marker for AKI (27).

A severe and refractory AKI is an indication for CRRT, and early CRRT is recommended for patients with oliguria or fluid overload (31, 32). In our study, we found that AKI stage 2–3 was an independent risk factor for CRRT. CRRT can maintain water, electrolyte, acid-base balance, uremic solute homeostasis to prevent or delay the deterioration of renal function (32). The patients with AKI stage 2–3 had a 1-year survivability rate of 90% if the renal function was restored within 7 days (33, 34). It remains controversial as to the timing of initiation (35), dose, discontinuation (36), quality assessment indicators (37, 38) of RRT in patients with AKI. The clinicians must formulate and select individual treatment plans for their patients (39).

The results of the current study showed that in-hospital mortality in the CRRT group was 4.6 times higher than in the non-CRRT group. It was reported that close to 40% of the patients in the dialysis mortality population died from the causes, such as heart failure, stroke, and myocardial infarction and infection (15), drinking (40), CPB duration (41, 42), hypotension (43), CVA (44), hepatic failure, and ARDS (45). Our findings were coherent with those of the previous studies. The kidney may induce distant organ crosstalk, including lung, heart, liver, or intestine. The prognosis in complicated AKI is poor when distant organ injury occurs (46, 47). Therefore, to reduce dialysis mortality, it is important to treat the distal organ crosstalk caused by AKI rather than focusing on the renal impairment alone (48).

Previous studies had shown that renal malperfusion was an independent risk factor for AKI, 30-day mortality, and poor prognosis in patients with AAAD (5, 49, 50). In our study, there was no significant increase in the incidence of renal malperfusion and renal artery involvement before surgery in the CRRT group and the post-CRRT in-hospital mortality group relative to the other groups. It is probably because that renal malperfusion improved before surgery or because timely treatment after the occurrence of AKI prevented the progression of AKI and thus reduced the usage of CRRT and in-hospital mortality.

Study Limitations

There were certain limitations to the present study: (i) data collected by different people over different periods may be affected by confounding factors, thereby affecting the conclusions; (ii) due to the lack of urine data, the creatinine level was used to define AKI; (iii) our study did not include long-term follow-up and did not clarify long-term outcomes, such as long-term mortality, whether the kidney function recovers after the CRRT or whether the condition progresses to chronic or end-stage renal disease after AAAD.

Conclusions

In the patients with post-operative AAAD, CRRT was in high demand and in-hospital mortality remained high. Diabetes, baseline SCr, Cys-C, lung infection, second thoracotomy, and severe AKI were independent risk factors for CRRT. Severe cardiac failure and lactic acidosis were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with CRRT. The risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing AAAD surgery were determined to help identify the high-risk patients and make appropriate clinical decisions. Further randomized-controlled studies are urgently needed to establish the risk factors for CRRT and in-hospital mortality.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Key R&D Projects [Nos. 2017SZ0113, 2017SZ0144, 2019YFS0282, and 2019YFG0491] and 1·3·5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence–Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University [NO.2020HXFH049], Sichuan, China.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committees of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LY, XC, LJ, and JZ: research idea and study design. XC, LL, and TZ: data acquisition. XC, MF, JY, XW, and SW: statistical analysis. LY, JZ, and LJ: supervision or mentorship. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and participants from the West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Sichuan, China, for providing the clinical data for this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- CSA-AKI

cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury

- AAAD

acute type A aortic dissection

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- AKI-D

AKI incidence requiring dialysis

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- SCr

serum creatinine

- SD

standard deviations

- IQR

interquartile range

- BMI

body mass index

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- DHCA

Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- ALB

albumin

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- UA

uric acid

- Cys-C

cystatin C

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- CVA

acute cerebrovascular accident

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CRRT

continuous renal replacement therapy.

Abbreviations

References

1.

Bove T Monaco F Covello RD Zangrillo A . Acute renal failure and cardiac surgery. HSR Proc Intensive Care Cardiovasc Anesth. (2009) 1:13–21.

2.

Section 2: AKI definition . Kidney Int Suppl (2011). (2012) 2:19–36. 10.1038/kisup.2011.32

3.

Wang Y Bellomo R . Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: risk factors, pathophysiology and treatment. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2017) 13:697–711. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.119

4.

Sansone F Morgante A Ceresa F Salamone G Patanè F . Prognostic implications of acute renal failure after surgery for type A acute aortic dissection. Aorta (Stamford). (2015) 3:91–7. 10.12945/j.aorta.2015.14.022

5.

Ko T Higashitani M Sato A Uemura Y Norimatsu T Mahara K et al . Impact of acute kidney injury on early to long-term outcomes in patients who underwent surgery for type A acute aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol. (2015) 116:463–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.04.043

6.

Hobson CE Yavas S Segal MS Schold JD Tribble CG Layon AJ et al . Acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality after cardiothoracic surgery. Circulation. (2009) 119:2444–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.800011

7.

Lenihan CR Montez-Rath ME Mora Mangano CT Chertow GM Winkelmayer WC . Trends in acute kidney injury, associated use of dialysis, and mortality after cardiac surgery, 1999 to 2008. Ann Thorac Surg. (2013) 95:20–8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.05.131

8.

Truche AS Darmon M Bailly S Clec'h C Dupuis C Misset B et al . Continuous renal replacement therapy versus intermittent hemodialysis in intensive care patients: impact on mortality and renal recovery. Intensive Care Med. (2016) 42:1408–17. 10.1007/s00134-016-4404-6

9.

Nadim MK Forni LG Bihorac A Hobson C Koyner JL Shaw A et al . Cardiac and vascular surgery-associated acute kidney injury: the 20th international consensus conference of the ADQI (Acute Disease Quality Initiative) group. J Am Heart Assoc. (2018) 7:e008834. 10.1161/JAHA.118.008834

10.

Palomba H Castro I Yu L Burdmann EA . The duration of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery increases the risk of long-term chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol. (2017) 30:567–72. 10.1007/s40620-016-0351-0

11.

Roh GU Lee JW Nam SB Lee J Choi JR Shim YH . Incidence and risk factors of acute kidney injury after thoracic aortic surgery for acute dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. (2012) 94:766–71. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.057

12.

Helgason D Helgadottir S Ahlsson A Gunn J Hjortdal V Hansson EC et al . Acute kidney injury after acute repair of type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. (2021) 111:1292–8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.07.019

13.

Rice RD Sandhu HK Leake SS Afifi RO Azizzadeh A Charlton-Ouw KM et al . Is total arch replacement associated with worse outcomes during repair of acute type A aortic dissection?Ann Thorac Surg. (2015) 100:2159–65. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.06.007

14.

Landoni G Zangrillo A Franco A Aletti G Roberti A Calabrò MG et al . Long-term outcome of patients who require renal replacement therapy after cardiac surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2006) 23:17–22. 10.1017/S0265021505001705

15.

Hanafusa N Nakai S Iseki K Tsubakihara Y . Japanese society for dialysis therapy renal data registry-a window through which we can view the details of Japanese dialysis population. Kidney Int Suppl. (2011). (2015) 5:15–22. 10.1038/kisup.2015.5

16.

Goligorsky MS . Vascular endothelium in diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2017) 312:F266–75. 10.1152/ajprenal.00473.2016

17.

Stieger N Worthmann K Teng B Engeli S Das AM Haller H et al . Impact of high glucose and transforming growth factor-β on bioenergetic profiles in podocytes. Metabolism. (2012) 61:1073–86. 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.12.003

18.

Anders HJ Huber TB Isermann B Schiffer M . CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2018) 14:361–77. 10.1038/s41581-018-0001-y

19.

Poston JT Koyner JL . Sepsis associated acute kidney injury. BMJ. (2019) 364:k4891. 10.1136/bmj.k4891

20.

Murugan R Karajala-Subramanyam V Lee M Yende S Kong L Carter M et al . Acute kidney injury in non-severe pneumonia is associated with an increased immune response and lower survival. Kidney Int. (2010) 77:527–35. 10.1038/ki.2009.502

21.

Joannidis M Forni LG Klein SJ Honore PM Kashani K Ostermann M et al . Lung-kidney interactions in critically ill patients: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 21 Workgroup. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:654–72. 10.1007/s00134-019-05869-7

22.

Kowalik MM Lango R Klajbor K Musiał-Swiatkiewicz V Kołaczkowska M Pawlaczyk R et al . Incidence- and mortality-related risk factors of acute kidney injury requiring hemofiltration treatment in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a single-center 6-year experience. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2011) 25:619–24. 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.12.011

23.

Wu HB Ma WG Zhao HL Zheng J Li JR Liu O et al . Risk factors for continuous renal replacement therapy after surgical repair of type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Dis. (2017) 9:1126–32. 10.21037/jtd.2017.03.128

24.

Brown JR Cochran RP Dacey LJ Ross CS Kunzelman KS Dunton RF et al . Perioperative increases in serum creatinine are predictive of increased 90-day mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. (2006) 114(1 Suppl.):I409–13. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000596

25.

Chien TM Wen H Huang JW Hsieh CC Chen HM Chiu CC et al . Significance of preoperative acute kidney injury in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. J Formos Med Assoc. (2019) 118:815–20. 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.09.003

26.

Smischney NJ Shaw AD Stapelfeldt WH Boero IJ Chen Q Stevens M et al . Postoperative hypotension in patients discharged to the intensive care unit after non-cardiac surgery is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Crit Care. (2020) 24:682. 10.1186/s13054-020-03412-5

27.

Herget-Rosenthal S Marggraf G Hüsing J Göring F Pietruck F Janssen O et al . Early detection of acute renal failure by serum cystatin C. Kidney Int. (2004) 66:1115–22. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00861.x

28.

Royakkers AA van Suijlen JD Hofstra LS Kuiper MA Bouman CS Spronk PE et al . Serum cystatin C-A useful endogenous marker of renal function in intensive care unit patients at risk for or with acute renal failure?Curr Med Chem. (2007) 14:2314–7. 10.2174/092986707781696555

29.

Villa P Jiménez M Soriano MC Manzanares J Casasnovas P . Serum cystatin C concentration as a marker of acute renal dysfunction in critically ill patients. Crit Care. (2005) 9:R139–43. 10.1186/cc3044

30.

White C Akbari A Hussain N Dinh L Filler G Lepage N et al . Estimating glomerular filtration rate in kidney transplantation: a comparison between serum creatinine and cystatin C-based methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2005) 16:3763–70. 10.1681/ASN.2005050512

31.

Jentzer JC Bihorac A Brusca SB Del Rio-Pertuz G Kashani K Kazory A et al . Contemporary management of severe acute kidney injury and refractory cardiorenal syndrome: JACC council perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1084–101. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.070

32.

Bagshaw SM Wald R . Strategies for the optimal timing to start renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. (2017) 91:1022–32. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.053

33.

Ronco C Bellomo R Kellum JA . Acute kidney injury. Lancet. (2019) 394:1949–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32563-2

34.

Kellum JA Sileanu FE Bihorac A Hoste EA Chawla LS . Recovery after acute kidney injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 195:784–9110.1164/rccm.201604-0799OC

35.

Clark E Wald R Levin A Bouchard J Adhikari NK Hladunewich M et al . Timing the initiation of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury in Canadian intensive care units: a multicentre observational study. Can J Anaesth. (2012) 59:861–70. 10.1007/s12630-012-9750-4

36.

Gibney N Hoste E Burdmann EA Bunchman T Kher V Viswanathan R et al . Timing of initiation and discontinuation of renal replacement therapy in AKI: unanswered key questions. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2008) 3:876–80. 10.2215/CJN.04871107

37.

Rewa OG Tolwani A Mottes T Juncos LA Ronco C Kashani K et al . Quality of care and safety measures of acute renal replacement therapy: workgroup statements from the 22nd acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) consensus conference. J Crit Care. (2019) 54:52–7. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.07.003

38.

Schiffl H . Discontinuation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury: predictive factors of renal function recovery. Int Urol Nephrol. (2018) 50:1845–51. 10.1007/s11255-018-1947-1

39.

Forni LG Chawla L Ronco C . Precision and improving outcomes in acute kidney injury: personalizing the approach. J Crit Care. (2017) 37:244–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.08.027

40.

Gacouin A Lesouhaitier M Frerou A Painvin B Reizine F Rafi S et al . At-risk drinking is independently associated with acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. (2019) 47:1041–9. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003801

41.

Suen WS Mok CK Chiu SW Cheung KL Lee WT Cheung D et al . Risk factors for development of acute renal failure (ARF) requiring dialysis in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Angiology. (1998) 49:789–800. 10.1177/000331979804900902

42.

Axtell AL Fiedler AG Melnitchouk S D'Alessandro DA Villavicencio MA Jassar AS et al . Correlation of cardiopulmonary bypass duration with acute renal failure after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2019). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.01.072. [Epub ahead of print].

43.

Shawwa K Kompotiatis P Jentzer JC Wiley BM Williams AW Dillon JJ et al . Hypotension within one-hour from starting CRRT is associated with in-hospital mortality. J Crit Care. (2019) 54:7–13. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.07.004

44.

Nadkarni GN Patel AA Konstantinidis I Mahajan A Agarwal SK Kamat S et al . Dialysis requiring acute kidney injury in acute cerebrovascular accident hospitalizations. Stroke. (2015) 46:3226–31. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010985

45.

Mehta RL Bouchard J Soroko SB Ikizler TA Paganini EP Chertow GM et al . Sepsis as a cause and consequence of acute kidney injury: program to improve care in acute renal disease. Intensive Care Med. (2011) 37:241–8. 10.1007/s00134-010-2089-9

46.

Husain-Syed F Rosner MH Ronco C . Distant organ dysfunction in acute kidney injury. Acta Physiol (Oxf). (2020) 228:e13357. 10.1111/apha.13357

47.

Lee SA Cozzi M Bush EL Rabb H . Distant organ dysfunction in acute kidney injury: a review. Am J Kidney Dis. (2018) 72:846–56. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.03.028

48.

Doi K Rabb H . Impact of acute kidney injury on distant organ function: recent findings and potential therapeutic targets. Kidney Int. (2016) 89:555–64. 10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.019

49.

Englberger L Suri RM Li Z Dearani JA Park SJ Sundt TM 3rd et al . Validation of clinical scores predicting severe acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. (2010) 56:623–31. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.017

50.

Zindovic I Gudbjartsson T Ahlsson A Fuglsang S Gunn J Hansson EC et al . Malperfusion in acute type A aortic dissection: an update from the Nordic Consortium for Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2019) 157:1324–1333.e6. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.10.134

Summary

Keywords

acute type A aortic dissection, surgery, acute kidney injury, continuous renal replacement therapy, CRRT, risk factors

Citation

Chen X, Zhou J, Fang M, Yang J, Wang X, Wang S, Li L, Zhu T, Ji L and Yang L (2021) Incidence- and In-hospital Mortality-Related Risk Factors of Acute Kidney Injury Requiring Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Acute Type a Aortic Dissection. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8:749592. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.749592

Received

29 July 2021

Accepted

27 September 2021

Published

23 November 2021

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Hendrik Tevaearai Stahel, Bern University Hospital, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Mohammed Idhrees, SIMS Hospital, India; Filippo Rapetto, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Chen, Zhou, Fang, Yang, Wang, Wang, Li, Zhu, Ji and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lichuan Yang ylcgh@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

This article was submitted to Heart Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.