Abstract

Background:

A subset of patients require a tracheostomy as respiratory support in a severe state after cardiac surgery. There are limited data to assess the predictors for requiring postoperative tracheostomy (POT) in cardiac surgical patients.

Methods:

The records of adult patients who underwent cardiac surgery from 2016 to 2019 at our institution were reviewed. Univariable analysis was used to assess the possible risk factors for POT. Then multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors. A predictive scoring model was established with predictor assigned scores derived from each regression coefficient divided by the smallest one. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test were used to evaluate the discrimination and calibration of the risk score, respectively.

Results:

A total of 5,323 cardiac surgical patients were included, with 128 (2.4%) patients treated with tracheostomy after cardiac surgery. Patients with POT had a higher frequency of readmission to the intensive care unit (ICU), longer stay, and higher mortality (p < 0.001). Mixed valve surgery and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), aortic surgery, renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary edema, age >60 years, and emergent surgery were independent predictors. A 9-point risk score was generated based on the multivariable model, showing good discrimination [the concordance index (c-index): 0.837] and was well-calibrated.

Conclusions:

We established and verified a predictive scoring model for POT in patients who underwent cardiac surgery. The scoring model was conducive to risk stratification and may provide meaningful information for clinical decision-making.

Introduction

Respiratory pulmonary complications are common after cardiac surgery, such as pneumonia and acute respiratory failure, which are associated with an increase in morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilization (1–3). Postoperative respiratory failure has been previously reported with an incidence of 9.1–15.9% in patients who underwent cardiac surgery (3, 4), and patients with severe respiratory failure after cardiac surgery require tracheostomies. Tracheostomy is generally regarded as a marker of serious postoperative outcomes, and two-thirds of the deaths occur in patients who underwent tracheostomy after cardiac surgery (5).

Despite most critically ill patients with respiratory failure tolerating short-term tracheal intubation well with few complications, longer mechanical ventilation is related to adverse outcomes, and tracheostomy as a common critical care procedure is used for these patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilatory support (6). Renal failure, aortic procedures, and hemodynamic instability have been revealed to predict the occurrence of respiratory failure after cardiac surgery (4). Moreover, risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation in patients who underwent cardiac surgery have been identified, such as age more than 65 years, emergency surgery, and left ventricular ejection fraction of 30% or less (7). However, not all the patients who need prolonged mechanical ventilation are tracheostomized. Predictor assessment of tracheostomy among cardiac surgical patients in the early stage is limited, and a predictive model for tracheostomy is still in urgent need.

In this study, we mainly aimed to identify independent predictors for postoperative tracheostomy (POT) in patients who underwent cardiac surgery and to develop and validate a predictive scoring model. The model may be useful for risk identification and decision-making in perioperative management.

Methods

Ethical Statement

Ethical approval was given by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IORG No. IORG0003571). The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient informed consent was waived.

Study Population

This was a retrospective study performed in a tertiary medical center that included adult patients who underwent cardiac surgery between January 2016 and December 2019. We involved all cardiac surgical patients with the exception of those who had immunosuppression, immunodeficiency, organ transplantation, intraoperative death, discharge or death within 48 h after surgery, and incomplete medical records.

Baseline Characteristics

All clinical data of this study population were extracted from the electronic medical-record system of our institution. The demographic variables that were assessed in this study were gender, age, height, weight, body mass index, smoking history, and drinking history. Preoperative comorbidity variables that were evaluated in the study were hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary edema, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), past history of cardiac surgery, past history of general history, renal insufficiency, gastrointestinal tract disease, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary artery hypertension, pericardial effusion, left ventricular ejection fraction, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III–IV, diameter of the left atrium, diameter of the left ventricle, diameter of the right atrium, and diameter of the right ventricle. Laboratory variables in our analysis contained serum creatinine, serum albumin, serum globulin, platelet count, white blood cell count, red blood cell count, and hemoglobin. The different surgical types that were analyzed included isolated valve surgery, isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), mixed valve surgery and CABG, aortic surgery, other types, and emergent surgery.

Postoperative variables included readmission to the intensive care unit (ICU), the length of ICU stay and hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was tracheostomy after cardiac surgery. All the tracheostomies were performed by the percutaneous route. The indications for tracheostomy in this study included prolonged mechanical ventilation, one or more failed trails of extubation, repeated intubation, predicted difficult reintubation, bypass of upper airway obstruction, and the need for tracheal access to remove thick pulmonary secretions (8). The secondary endpoints were readmission to ICU, in-hospital mortality, and the lengths of ICU and hospital stay.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (version 24, Armonk, NY, USA). Normally distributed continuous variables were shown as means ± SDs, while non-normally distributed continuous variables as medians and inter-quartile ranges. Categorical variables were expressed as counts with percentages. Data with normal distribution were analyzed by Student's t-test, while data with non-normal distribution were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were analyzed by χ2 tests or Fisher's exact test.

Univariable analysis was conducted to assess the possible risk factors for POT among all the collected variables. Those factors associated with tracheostomy after cardiac surgery (exploratory p < 0.10) were introduced into the multivariable logistic regression analysis, which was used to identify independent risk factors for POT. Then, the significant continuous variables were dichotomized according to the Youden index or the cutoff values reported previously, and multivariable logistic analysis was performed again. In this multivariable model, the independent predictors were assigned with scores, which were rounded up integers, derived from each regression coefficient divided by the smallest one. The scores of all the predictors were summed to generate a total risk score for one person, and risk subgroups of predicting POT were constructed based on the composite risk score.

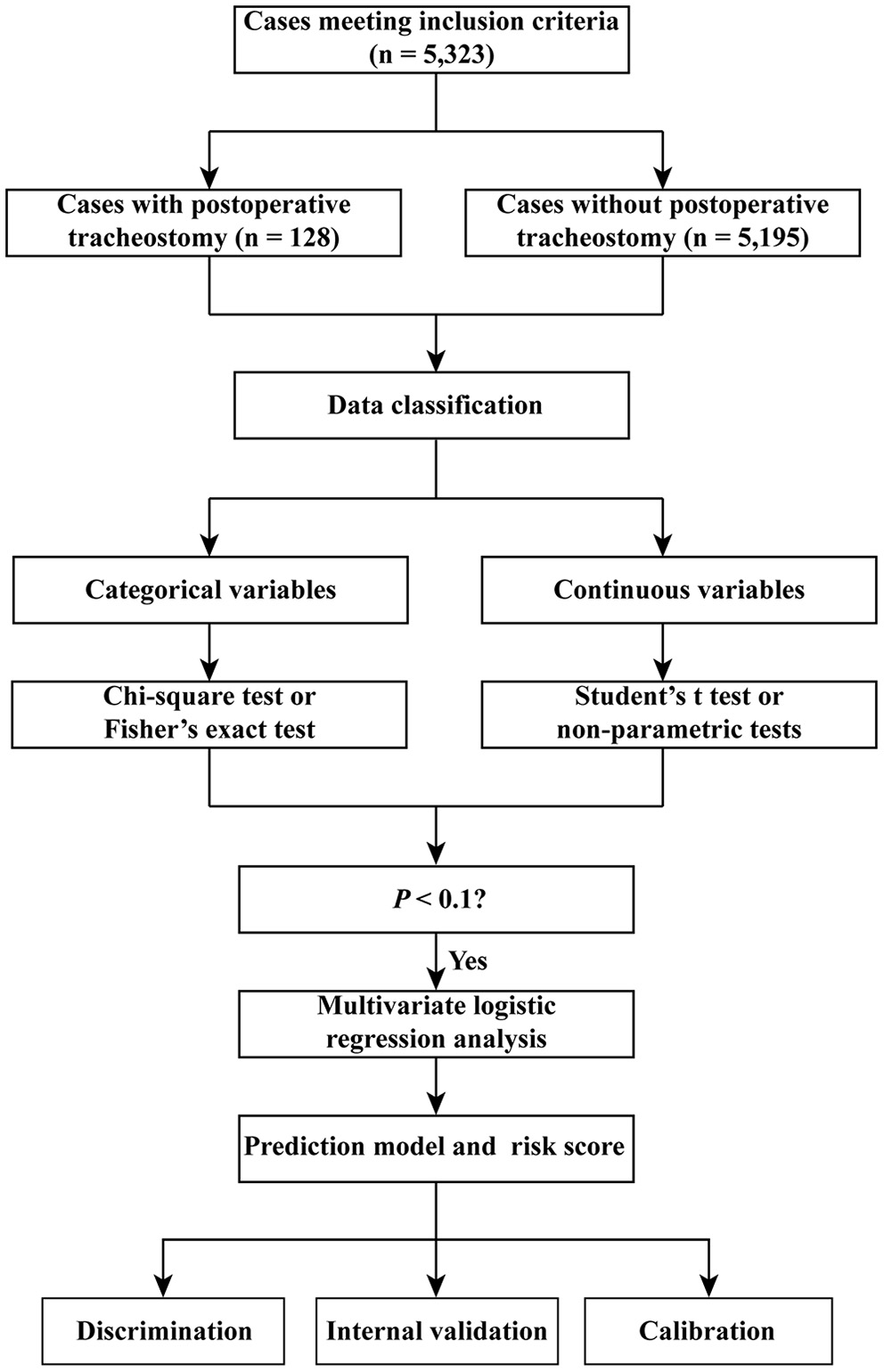

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) or the concordance index (c-index) was used to evaluate the discrimination of the risk score. The AUCs of the three models were compared: the first model with continuous variables, the second model with the dichotomy of the continuous variables, and the third model with risk scores. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was conducted to assess the calibration of the model. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The flow chart of the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Flow chart of the study.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 5,323 patients who underwent cardiac surgery were included in this study for analysis. The average age was 51 years; 51.4% of the patients were men (Table 1). The average body mass index was 23.4 kg/m2; more than 20% of the patients had a drinking or smoking history. The most common underlying conditions were peripheral vascular disease (42.4%), followed by cerebrovascular disease (34.0%), hypertension (30.1%), past history of general history (28.1%), and pulmonary artery hypertension (26.1%). A minority of patients had preoperative pulmonary edema (4.8%) and past history of cardiac surgery (7.1%). The most commonly performed surgical type was isolated valve surgery (54.4%). The proportion of isolated CABG, mixed valve surgery and CABG, and emergent surgery were around 10%. Intraoperative variables are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Without POT n = 5,195 (%) | With POT n = 128 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 2,907 (56.0) | 94 (73.4) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 51.03 ± 12.90 | 56.95 ± 12.04 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 164.95 ± 8.03 | 165.97 ± 8.51 | 0.084 |

| Weight (kg) | 63.76 ± 11.97 | 67.65 ± 14.64 | 0.006 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.32 ± 3.37 | 24.42 ± 4.20 | 0.008 |

| Smoking history | 1,489 (28.7) | 59 (46.1) | <0.001 |

| Drinking history | 1,117 (21.5) | 37 (28.9) | 0.045 |

| Underlying conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 1,529 (29.4) | 75 (58.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 417 (8.0) | 21 (16.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 536 (10.3) | 21 (16.4) | 0.026 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1,750 (33.7) | 62 (48.4) | 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2,208 (42.5) | 50 (39.1) | 0.437 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 896 (17.2) | 16 (12.5) | 0.159 |

| Renal insufficiency | 471 (9.1) | 53 (41.4) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract disease | 434 (8.4) | 13 (10.2) | 0.468 |

| Pulmonary edema | 242 (4.7) | 11 (8.6) | 0.039 |

| Past history of cardiac surgery | 363 (7.0) | 13 (10.2) | 0.167 |

| Past history of general history | 1,464 (28.2) | 33 (25.8) | 0.551 |

| NYHA class III–IV | 852 (16.4) | 24 (18.8) | 0.479 |

| Pulmonary artery hypertension | 1,370 (26.4) | 20 (15.6) | 0.006 |

| Pericardial effusion | 732 (14.1) | 24 (18.8) | 0.136 |

| Diameter of the left atrium (cm) | 4.2 (3.6, 5.0) | 4.0 (3.6, 4.8) | 0.222 |

| Diameter of the left ventricle (cm) | 5.0 (4.5, 5.7) | 4.9 (4.5, 5.6) | 0.359 |

| Diameter of the right atrium (cm) | 3.8 (3.5, 4.4) | 3.8 (3.5, 4.4) | 0.940 |

| Diameter of the right ventricle (cm) | 3.6 (3.3, 4.0) | 3.6 (3.4, 4.1) | 0.316 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 62 (58, 66) | 62 (59, 65) | 0.236 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 5.78 (4.78, 7.10) | 7.48 (5.47, 11.11) | <0.001 |

| Red blood cell count (×1012/L) | 4.28 (3.92, 4.64) | 4.18 (3.74, 4.65) | 0.076 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 129 (118, 140) | 127 (114, 141) | 0.340 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 180 (145, 221) | 156 (120, 197) | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 40.5 (38.0, 42.7) | 39.0 (36.2, 41.4) | <0.001 |

| Serum globulin (g/L) | 24.4 (21.7, 27.2) | 25.3 (21.9, 28.5) | 0.081 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 71.7 (60.8, 85.0) | 82.3 (69.4, 114.0) | <0.001 |

| Surgical types | <0.001 | ||

| Isolated valve surgery | 2,871 (55.3) | 26 (20.3) | |

| Isolated coronary artery bypass grafting | 576 (11.1) | 15 (11.7) | |

| Mixed valve surgery and coronary artery bypass grafting | 463 (8.9) | 18 (14.1) | |

| Aortic surgery | 840 (16.2) | 64 (50.0) | |

| Other types | 445 (8.5) | 5 (3.9) | |

| Emergent surgery | 437 (8.4) | 55 (43.0) | <0.001 |

Univariable analysis of possible risk factors for POT after cardiac surgery.

POT, postoperative tracheostomy.

Derivation of the Risk Score Model

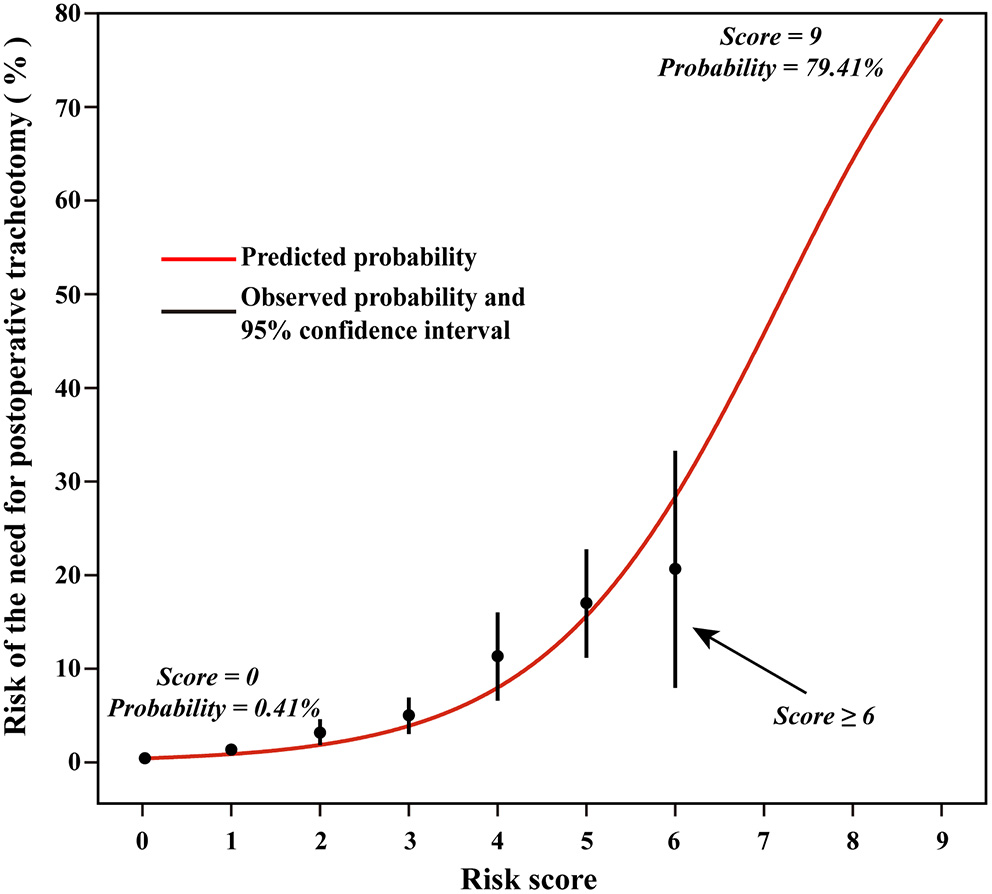

There were 128 (2.4%) patients treated with tracheostomy after cardiac surgery. The possible risk factors in univariable analysis were entered into multivariable regression analysis, such as surgical types, renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, COPD, pulmonary edema, age, and emergent surgery (Table 2). Significant factors in the first multivariable model were mixed valve and CABG surgery, aortic surgery, renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, COPD, pulmonary edema, older age, and emergent surgery. After dichotomizing the variables, we obtained the second multivariable model, among which the age >60 years was an independent predictor (Table 3). Predictors were assigned 1 or 2 points according to their regression coefficients in the second model, and thus, the third model with risk score was derived (Table 3). There were overall 9 points of the risk score and the predicted probabilities of POT based on the risk score are presented in Figure 2.

Table 2

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical types | 0.022 | ||

| Isolated valve surgery | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Isolated coronary artery bypass grafting | 1.857 (0.922–3.743) | 0.083 | 0.619 |

| Mixed valve surgery and coronary artery bypass grafting | 2.446 (1.302–4.597) | 0.005 | 0.895 |

| Aortic surgery | 2.685 (1.254–5.749) | 0.011 | 0.988 |

| Other types | 2.240 (0.839–5.983) | 0.108 | 0.807 |

| Renal insufficiency | 3.386 (2.277–5.034) | <0.001 | 1.220 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.089 (1.222–3.571) | 0.007 | 0.737 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.644 (1.554–4.499) | <0.001 | 0.972 |

| Pulmonary edema | 2.853 (1.438–5.660) | 0.003 | 1.048 |

| Age (years) | 1.043 (1.024–1.062) | <0.001 | 0.042 |

| Emergent surgery | 5.244 (2.503–10.987) | <0.001 | 1.657 |

| Constant | 0.001 | <0.001 | −7.483 |

Multivariable analysis of independent risk factors for POT after cardiac surgery, without dichotomy of the continuous variables.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; POT, postoperative tracheostomy.

Table 3

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Coefficient | Point value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical types | 0.019 | |||

| Isolated valve surgery | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 |

| Isolated coronary artery bypass grafting | 1.978 (0.976–4.010) | 0.058 | 0.682 | 0 |

| Mixed valve surgery and coronary artery bypass grafting | 2.673 (1.421–5.026) | 0.002 | 0.983 | 1 |

| Aortic surgery | 2.523 (1.176–5.416) | 0.018 | 0.926 | 1 |

| Other types | 1.859 (0.700–4.936) | 0.213 | 0.620 | 0 |

| Renal insufficiency | 3.352 (2.247–5.000) | <0.001 | 1.210 | 2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.210 (1.286–3.799) | 0.004 | 0.793 | 1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.740 (1.608–4.669) | <0.001 | 1.008 | 1 |

| Pulmonary edema | 2.864 (1.443–5.686) | 0.003 | 1.052 | 1 |

| Emergent surgery | 5.315 (2.525–11.186) | <0.001 | 1.671 | 2 |

| Age >60 years | 2.136 (1.441–3.167) | <0.001 | 0.759 | 1 |

| Constant | 0.004 | <0.001 | −5.481 |

Multivariable analysis of independent risk factors for POT after cardiac surgery, with dichotomy of the continuous variables.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; POT, postoperative tracheostomy.

Figure 2

Predicted rates of the need for postoperative tracheostomy based on the risk score model.

Validation and Assessment of the Risk Score Model

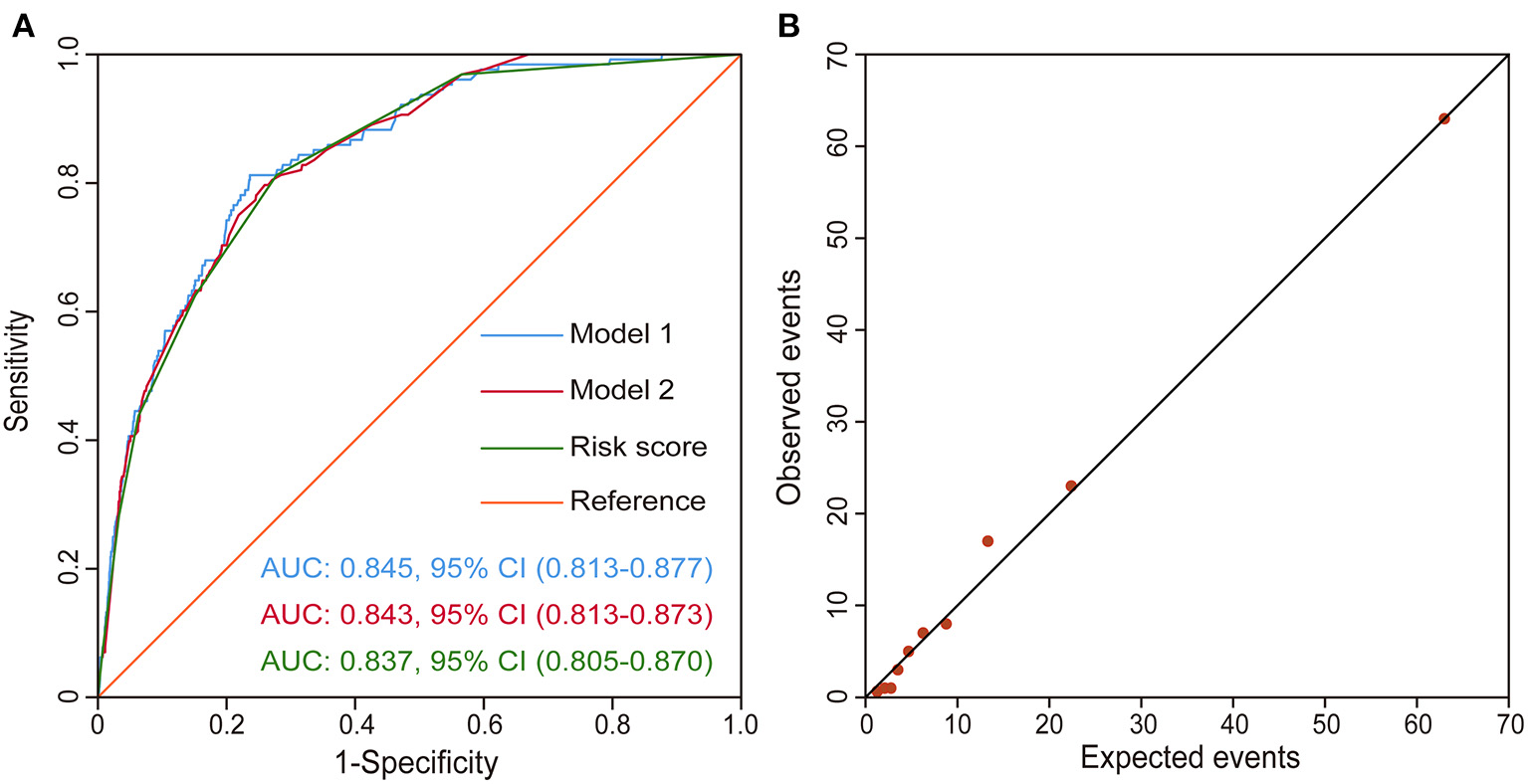

The discriminatory performance of each model was assessed by the AUC. The AUC of the first multivariable model was 0.845 (95% CI, 0.813–0.877), indicating very good discriminatory ability. Similarly, the second multivariable model had an AUC of 0.843 (95% CI, 0.813–0.873). Comparing the predictive abilities of these two models, we found that there was no significant difference (p = 0.945), which meant that it was appropriate to dichotomize continuous variables as the dichotomy did not significantly reduce the predictive ability of the model. The AUC of the third model, the risk score model, was 0.837 (95% CI, 0.805–0.870), also showing robust predictive performance. There appeared no significant difference in the predictive ability after comparing those three ROC curves pair by pair (p > 0.5) indicated that the predictive ability was not significantly reduced after the latter two model processing, which was reasonable and was more conducive to clinical application. The three ROC curves are presented in Figure 3A. The model showed good calibration by both visual inspection and goodness-of-fit test (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 4.270, p = 0832; Figure 3B).

Figure 3

Validation of the risk score model. (A) ROC curves drawn using the risk score model, Model 1, and Model 2 in the derivation set. Model 1 is the first model with continuous variables and Model 2 is the second model with a dichotomy of the continuous variables. (B) Observed vs. expected events by predicted risk category. The correlation between observed and predicted events is 0.99. CI, confidence interval; ROC curve, receiver operating characteristic curve.

Risk Stratification

Based on the calculated composite risk score, three risk intervals were identified as low-risk, medium-risk, and high-risk groups. Patients with scores ≤ 3 as a low-risk group constituted 92.8% of the total study population, having a rate of 1.5% to require POT. Patients with scores 4–5 as a medium-risk group constituted 6.4% of the total study population, having a rate of 14.0% to require POT. While, patients with scores ≥6 as a high-risk group constituted 0.8% of the total study population, having a rate of 19.5% to require POT.

Outcomes

The whole mortality of the study population was 3.1%, and the patients with POT had significantly higher mortality than patients without POT (46.9 vs. 2.1%, p < 0.001; Table 4). Similarly, higher frequency of readmission to ICU, longer ICU, and hospital stay were observed in patients with POT.

Table 4

| Variables |

All patients

n = 5,323 (%) |

Without POT

n = 5,195 (%) |

With POT

n = 128 (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission to ICU | 207 (3.9) | 163 (3.1) | 44 (34.4) | <0.001 |

| ICU stay (days) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 22 (18, 31) | <0.001 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 15 (11, 19) | 14 (11, 19) | 34 (24, 47) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 167 (3.1) | 107 (2.1) | 60 (46.9) | <0.001 |

Postoperative variables in patients with and without POT after cardiac surgery.

ICU, intensive care unit; POT, postoperative tracheostomy.

Discussion

Tracheostomy may improve comfort and reduce the need for sedation and analgesia in patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU compared with translaryngeal airway access and can also provide more favorable conditions for the weaning of mechanical ventilation (9). In our study population who underwent cardiac surgery, the overall incidence of POT was 2.4%, which was within the range of the results in previous studies (10, 11). However, from our results, the cardiac surgical patients treated with POT were more likely to encounter readmission to ICU, experience a longer ICU and hospital stay, and have a higher mortality rate. The mortality of patients who underwent tracheostomy in this study could reach 46.9%, in line with reported in-hospital mortality 36–49% before (5, 12). The survival after the development of prolonged mechanical ventilation is interactively affected by factors, such as age, preoperative pulmonary dysfunction, and chronic renal insufficiency, and the implementation of tracheostomy appears to be a sign for patients less likely to wean from mechanical ventilation (5, 13). In light of these findings, early identification of high-risk patients who require tracheostomy warranted investigations, and a targeted strategy implemented to improve clinical outcomes was needed.

In the current study, we found that preoperative risk factors, such as mixed valve and CABG surgery, aortic surgery, renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, COPD, pulmonary edema, older age, and emergent surgery were independently related to POT in patients who underwent cardiac surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first study with a large sample size to identify preoperative predictors for POT after cardiac surgery. A scoring model to predict the probability of POT was further constructed and was validated with good predictive performance, which might early and accurately select the patients who would develop into a severe condition needing POT treatment.

Emergent surgery and pre-existing renal insufficiency were two strong predictors with a higher score in our scoring model. In cardiac surgical patients, emergent surgery was identified as an independent risk factor for the development of ventilatory dependency by Murthy et al. and about 26% of those experiencing ventilatory dependency underwent tracheostomy (13). Beverly et al. also identified that emergency surgery and chronic kidney disease were associated with a high incidence of reintubation after cardiac surgery (14). Patients with chronic kidney disease appeared to have attenuated cardiopulmonary adaptations, which might reflect the affected respiratory muscle strength (15). In addition, kidney disease-related exercise intolerance could lead to increased frailty and worsened quality of life, while the frailty among patients who received mechanical ventilation was related to the need for tracheostomy (16, 17). Moreover, frailty and sarcopenia often co-occur in patients with older age, and sarcopenia can result in impaired ability to take deep breaths and clear secretions (17). Our study showed that older patients who underwent cardiac surgery were at greater risk of developing severe respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy. Similarly, another study has confirmed that age at least 70 years was an independent predictor of POT after aortic aneurysm repair surgery (18).

This study showed that aortic surgery was an independent risk factor to predict the occurrence of POT in our model. A significant relationship between aortic surgery and ventilatory dependency has been found in a previous study (13). Filsoufi et al. also observed that the highest incidence of respiratory failure was following aortic procedures and combined valve/CABG surgery (4). Of course, combined valve/CABG surgery was another surgical predictor of POT from our results. This factor has been demonstrated to be correlated to postoperative respiratory failure, and diabetes mellitus also has a correlation with respiratory failure (3). A study of the population eligible for CABG surgery indicated that patients with diabetes were more likely to have lower vital capacity parameters than those without diabetes (19). Moreover, patients with diabetes had a higher risk of having pulmonary complications, such as postoperative longer duration of ventilation and higher frequency of reintubation, and that the respiratory function was impaired in the course of the diabetic disease might explain it (20).

The presence of COPD in patients with cardiac surgery in our study was independently associated with the application of tracheostomy. COPD increased the risk of respiratory complications after cardiopulmonary bypass and was found to be related to extubation failure after cardiac surgery (21, 22). Preoperative disease processes, such as COPD, pulmonary hypertension, and severe left ventricular dysfunction, were surrogate factors for insufficient cardiopulmonary reserve, which increased the possibility of early postoperative extubation failure and prolonged mechanical ventilation (22). Pulmonary edema was also a factor causing respiratory insufficiency, and preoperative pulmonary edema was an independent predictor for POT in cardiac surgical patients. Hornik et al. showed cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass procedure could also cause inflammation and lung ischemia-reperfusion injury, leading to permeability pulmonary edema (23). Interestingly, a study of a virus-infected population found that pulmonary edema could independently predict the tracheostomy requirement (24).

The score model built based on the variables described above could assess the risk of POT for the cardiac surgical population. The endpoint of our study was treated with POT or no tracheostomy in patients who underwent cardiac surgery. However, many studies mainly focused on the timing of tracheostomy. The effect of early tracheostomy or prolonged intubation with possible late tracheostomy on the outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients has been a matter of debate. Trouillet et al. conducted a randomized trial and suggested that early tracheostomy provided no benefit in altering important clinical outcomes (25). While, Devarajan et al. indicated that early tracheostomy was associated with improved prognosis (26), and the differences in study results might be caused by different timing definitions of prolonged mechanical ventilation or tracheostomy. Overall, however, the outcomes of the cardiac surgical population with POT treatment were worse than those without POT. Therefore, our preoperative score prediction model was still meaningful for the management of cardiac surgical patients.

For the identified high-risk population at an early stage, early intervention may reduce the risk of requiring tracheostomy. Morimoto et al. suggested that prophylactic administration of sivelestat at the beginning of cardiopulmonary bypass could lead to better postoperative pulmonary function, thereby shortening the extubation time and decreasing the need for POT (27). A randomized controlled trial found that the cardiac surgical patients mechanically ventilated with a reduced tidal volume had reduced requirement for postoperative reintubation (28). In addition, the cardiopulmonary bypass has long been considered as a factor to produce diffuse lung injury, and the strategies, such as off-pump CABG use, heparin-coated circuits, and intraoperative ultrafiltration, could minimize this effect (29). However, for the low-risk patients, although there is also the possibility of failing to remove intubation early, our model may assist clinicians in making decisions, and perhaps these patients can avoid unnecessary additional invasive procedures, such as tracheostomy. Our scoring model may also provide meaningful information for the clinician to explain the illness condition to patients and their families.

Some limitations were however present. First, our study was a retrospective single-center design with a possible sample bias. Furthermore, due to different practices for tracheostomy support or families of patients differing in willingness to agree to additional surgery after cardiac surgery, our results and risk score model might not be generalizable to other centers. Second, our study results have not been externally validated, and the scoring model we constructed should be prospectively validated on cardiac surgical patient groups of other institutions. Third, although the tracheostomy was performed when estimated need for prolonged mechanical ventilation in our study population, there was no specific standard for tracheostomy. There might be some patients who should be treated with tracheostomy before death but did not actually undergo tracheostomy, and the subjective consideration to perform the tracheostomy or not was also an important limitation.

Conclusion

In this study, the requirement of tracheostomy after cardiac surgery was indicative of a high-risk set with a significant postoperative burden. Our study identified significant predictors for POT in patients who underwent cardiac surgery and established a 9-point risk score to predict the need for POT. The model had good predictive performance and the three created risk intervals can be used for risk stratification, which may help surgeons to prevent the development into a severe state requiring POT in clinical practice.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81800413, 82060092, and 81801586); Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (No. 2020CFB791), and Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China (No. 2020D01C181).

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IORG No. IORG0003571). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DW, YD, and SW participated in study design and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. DW, YS, SL, and HW contributed to data curation and analysis. XH, AZ, LW, and XD contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2021.799605/full#supplementary-material

- AUC

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CI

confidence interval

- ICU

intensive care unit

- POT

postoperative tracheostomy

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic.

Abbreviations

References

1.

Lukannek C Shaefi S Platzbecker K Raub D Santer P Nabel S et al . The development and validation of the Score for the Prediction of Postoperative Respiratory Complications (SPORC-2) to predict the requirement for early postoperative tracheal re-intubation: a hospital registry study. Anaesthesia. (2019) 74:1165–74. 10.1111/anae.14742

2.

Hortal J Muñoz P Cuerpo G Litvan H Rosseel PM Bouza E . Ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients undergoing major heart surgery: an incidence study in Europe. Crit Care. (2009) 13:R80. 10.1186/cc7896

3.

Thanavaro J Taylor J Vitt L Guignon MS Thanavaro S . Predictors and outcomes of postoperative respiratory failure after cardiac surgery. J Eval Clin Pract. (2020) 26:1490–7. 10.1111/jep.13334

4.

Filsoufi F Rahmanian PB Castillo JG Chikwe J Adams DH . Predictors and early and late outcomes of respiratory failure in contemporary cardiac surgery. Chest. (2008) 133:713–21. 10.1378/chest.07-1028

5.

Walts PA Murthy SC Arroliga AC Yared JP Rajeswaran J Rice TW et al . Tracheostomy after cardiovascular surgery: an assessment of long-term outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2006) 131:830–7. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.09.038

6.

Rana S Pendem S Pogodzinski MS Hubmayr RD Gajic O . Tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Mayo Clin Proc. (2005) 80:1632–8. 10.4065/80.12.1632

7.

Cislaghi F Condemi AM Corona A . Predictors of prolonged mechanical ventilation in a cohort of 5123 cardiac surgical patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2009) 26:396–403. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283232c69

8.

Mallick A Bodenham AR . Tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2010) 27:676–82. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833b1ba0

9.

Litton E Law T Stamp N . Tracheostomy in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2019) 33:91–2. 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.07.014

10.

Affronti A Casali F Eusebi P Todisco C Volpi F Beato V et al . Early versus late tracheostomy in cardiac surgical patients: a 12-year single center experience. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2019) 33:82–90. 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.05.041

11.

Ben-Avi R Ben-Nun A Levin S Simansky D Zeitlin N Sternik L et al . Tracheostomy after cardiac surgery: timing of tracheostomy as a risk factor for mortality. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2014) 28:493–6. 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.10.031

12.

Ballotta A Kandil H Generali T Menicanti L Pelissero G Ranucci M . Tracheostomy after cardiac operations: in-hospital and long-term survival. Ann Thorac Surg. (2011) 92:528–33. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.02.002

13.

Murthy SC Arroliga AC Walts PA Feng J Yared JP Lytle BW et al . Ventilatory dependency after cardiovascular surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2007) 134:484–90. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.03.006

14.

Beverly A Brovman EY Malapero RJ Lekowski RW Urman RD . Unplanned reintubation following cardiac surgery: incidence, timing, risk factors, and outcomes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2016) 30:1523–9. 10.1053/j.jvca.2016.05.033

15.

Kirkman DL Ramick MG Muth BJ Stock JM Townsend RR Edwards DG . A randomized trial of aerobic exercise in chronic kidney disease: evidence for blunted cardiopulmonary adaptations. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. (2020) 2020:101469. 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.101469

16.

Kirkman DL Bohmke N Carbone S Garten RS Rodriguez-Miguelez P Franco RL et al . Exercise intolerance in kidney diseases: physiological contributors and therapeutic strategies. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2021) 320:F161–f73. 10.1152/ajprenal.00437.2020

17.

Fernando SM McIsaac DI Rochwerg B Bagshaw SM Muscedere J Munshi L et al . Frailty and invasive mechanical ventilation: association with outcomes, extubation failure, and tracheostomy. Intensive Care Med. (2019) 45:1742–52. 10.1007/s00134-019-05795-8

18.

Songdechakraiwut T Aftab M Chatterjee S Green SY Price MD Preventza O et al . Tracheostomy after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. (2019) 108:778–84. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.02.063

19.

Szylińska A Listewnik M Ciosek Z Ptak M Mikołajczyk A Pawlukowska W et al . The relationship between diabetes mellitus and respiratory function in patients eligible for coronary artery bypass grafting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:907. 10.3390/ijerph15050907

20.

Lauruschkat AH Arnrich B Albert AA Walter JA Amann B Rosendahl UP et al . Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pulmonary complications after coronary bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2008) 135:1047–53. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.066

21.

de Prost N El-Karak C Avila M Ichinose F Vidal Melo MF . Changes in cysteinyl leukotrienes during and after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2011) 141:1496–502.e3. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.01.035

22.

Rady MY Ryan T . Perioperative predictors of extubation failure and the effect on clinical outcome after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. (1999) 27:340–7. 10.1097/00003246-199902000-00041

23.

Hornik C Meliones J . Pulmonary edema and hypoxic respiratory failure. Pediatric Crit Care Med. (2016) 17(8 Suppl 1):S178–81. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000823

24.

Tsou YA Cheng YK Chung HK Yeh YC Lin CD Tsai MH et al . Upper aerodigestive tract sequelae in severe enterovirus 71 infection: predictors and outcome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2008) 72:41–7. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.09.008

25.

Trouillet JL Luyt CE Guiguet M Ouattara A Vaissier E Makri R et al . Early percutaneous tracheotomy versus prolonged intubation of mechanically ventilated patients after cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 154:373–83. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-6-201103150-00002

26.

Devarajan J Vydyanathan A Xu M Murthy SM McCurry KR Sessler DI et al . Early tracheostomy is associated with improved outcomes in patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery. J Am College Surgeons. (2012) 214:1008–16.e4. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.03.005

27.

Morimoto N Morimoto K Morimoto Y Takahashi H Asano M Matsumori M et al . Sivelestat attenuates postoperative pulmonary dysfunction after total arch replacement under deep hypothermia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2008) 34:798–804. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.010

28.

Sundar S Novack V Jervis K Bender SP Lerner A Panzica P et al . Influence of low tidal volume ventilation on time to extubation in cardiac surgical patients. Anesthesiology. (2011) 114:1102–10. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318215e254

29.

García-Delgado M Navarrete-Sánchez I Colmenero M . Preventing and managing perioperative pulmonary complications following cardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. (2014) 27:146–52. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000059

Summary

Keywords

tracheostomy, cardiac surgery, risk factors, prediction model, risk score

Citation

Wang D, Wang S, Du Y, Song Y, Le S, Wang H, Zhang A, Huang X, Wu L and Du X (2022) A Predictive Scoring Model for Postoperative Tracheostomy in Patients Who Underwent Cardiac Surgery. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8:799605. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.799605

Received

21 October 2021

Accepted

28 December 2021

Published

28 January 2022

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Sandro Gelsomino, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Maruti Haranal, National Heart Institute, Malaysia; Bailing Li, Changhai Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Wang, Wang, Du, Song, Le, Wang, Zhang, Huang, Wu and Du.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaofan Huang dr_xfhuang@hust.edu.cnXinling Du xinlingdu@hust.edu.cnLong Wu wulong@hust.edu.cnAnchen Zhang 644720889@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Heart Surgery, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.