Abstract

Background:

Neutrophil counts to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHR), a composite marker of inflammation and lipid metabolism, has been considered as a predictor of clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction. However, the predictive value of NHR for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population remains unclear.

Methods:

Our study population comprised 34,335 adults in the United States obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (1999–2014) and were grouped in accordance with tertiles of NHR. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank test were used to investigate the differences of survival among groups. Multivariate Cox regression, restricted cubic spline analysis, and subgroup analysis were applied to explore the relationship of NHR with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Results:

The mean age of the study cohort was 49.6 ± 18.2 years and 48.4% were men. During a median follow-up of 82 months, 4,310 (12.6%) all-cause deaths and 754 (2.2%) cardiovascular deaths occurred. In a fully-adjusted Cox regression model, participants in the highest tertile had 29% higher hazard of all-cause mortality than those in the lowest tertile [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.19–1.41]. For cardiovascular mortality, the continuously increased HR with 95% CIs among participants in the middle and highest tertile were 1.30 (1.06–1.59) and 1.44 (1.17–1.78), respectively. The restricted cubic spline curve indicated that NHR had a non-linear association with all-cause mortality (p for non-linearity < 0.001) and a linear association with cardiovascular mortality (p for non-linearity = 0.553).

Conclusion:

Increased NHR was a strong and independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population.

Introduction

Neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHR) is a composite marker of inflammation and lipid metabolism, which allows simultaneous studies on the separate impact and more insights into the interaction (1). The two hematological parameters are inexpensive, easy to measure, and well-standardized. These features make NHR a promising clinical indicator. NHR is reportedly associated with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (2). However, the effect of NHR on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality has received limited attention.

It is known that chronic inflammation and abnormal lipid metabolism play crucial roles in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis, leading to adverse cardiovascular events and mortality (3). As proinflammatory cells, neutrophils have been recently recognized to participate in the various stages of atherosclerosis, which can aggravate endothelial dysfunction, recruit monocytes into atherosclerotic lesions, activate macrophages, promote foam cell formation, and contribute to plaque destabilization (4). By contrast, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) has been considered as a protective factor against atherosclerosis. The major cardioprotective mechanisms include reverse cholesterol transport, antioxidative properties, and anti-inflammatory effect in the endothelium (5). Previous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that HDL-C is an important predictor for mortality and cardiovascular mortality (6, 7).

Only few retrospective studies have investigated the correlation of NHR and short-term prognosis after intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke (8) and long-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction (1, 9). To our knowledge, there is no study yet on the association between NHR and long-term mortality in the general population. Therefore, we aimed to assess the predictive value of NHR for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among the general adult population of the United States using the clinical data available from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

Study Population

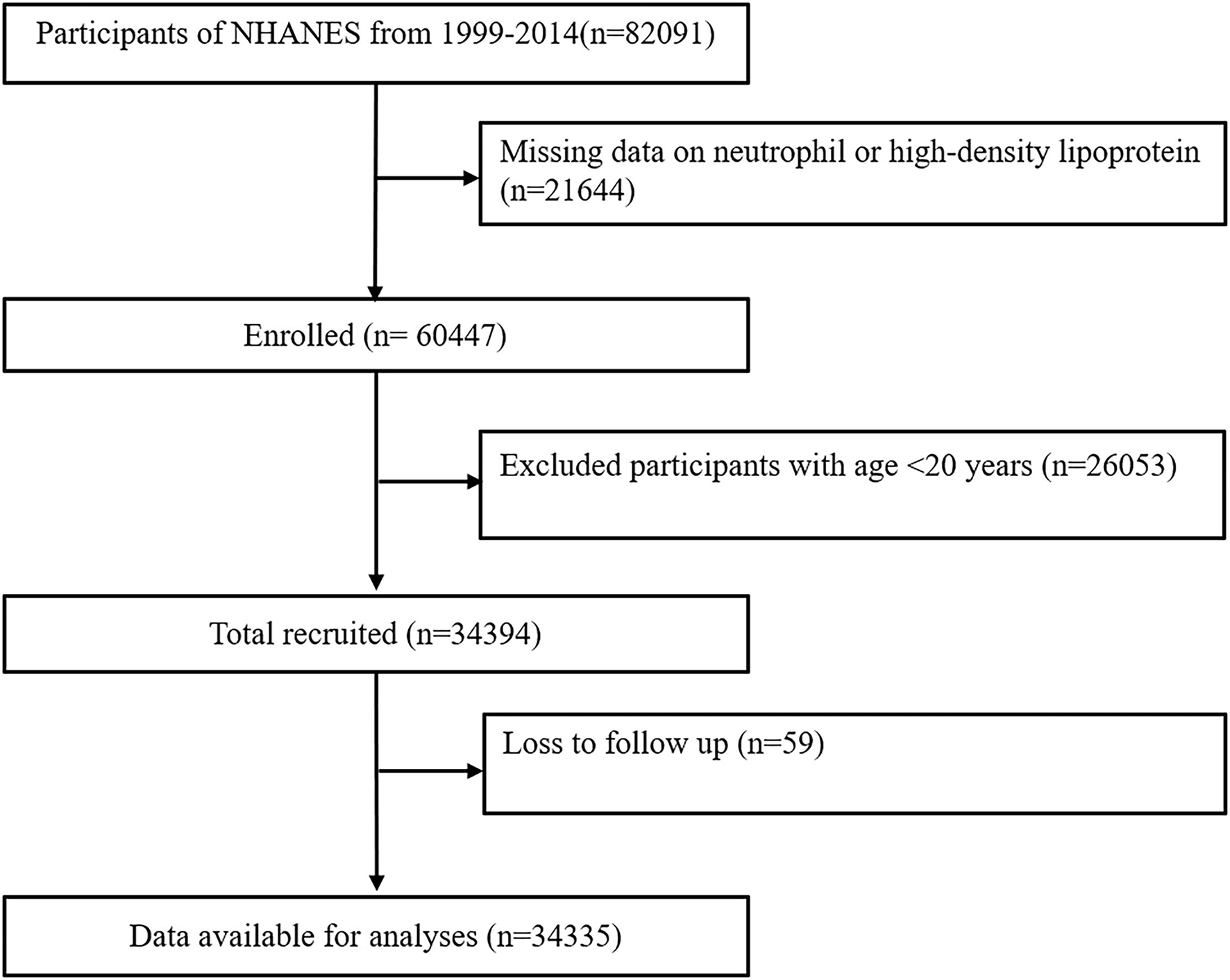

The NHANES is a continuous program conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The sample of the NHANES survey is selected to represent the non-institutionalized civilian population of the United States using a complex, multistage, probability sampling design. The 1999–2014 survey cycles included a total of 82,091 participants. Our study included participants in whom neutrophil count and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol data were available (n = 60,447). After excluding participants aged <18 years (n = 26,053) and those lost to follow-up (n = 59), a total of 34,335 participants were included for further analysis (Figure 1). The survey protocol was approved by the NCHS research ethics review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1

Study flowchart. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Assessment of Exposure

Neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio was calculated as the neutrophil count (103 cells/μl) divided by the HDL-C (mg/dl) value, both of which were acquired from laboratory tests. Blood specimens were collected following established venipuncture protocol and procedures. The UniCel DxH 800 Analyzer was used to measure the neutrophil absolute number. HDL-C was measured on the Roche modular P and Roche Cobas 6000 chemistry analyzers. This study modeled the tertiles of the exposure distribution to assess the potential association between NHR and the target outcomes.

Assessment of Covariates

Demographic information, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education level were collected by questionnaires. Smokers were defined as participants who reported smoking more than 100 cigarettes during their lifetime, and those who consumed at least 12 drinks in the past 12 months were classified as alcohol users (10). Self-reported personal interview data provided the medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters, which was obtained from the body measurements. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were determined as the average values of three consecutive blood pressure readings after resting quietly for 5 min. Albumin and serum creatinine test results were obtained from laboratory tests. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated according to the MDRD formula (11).

Ascertainment of Outcomes

The outcomes of this study were all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Mortality status and underlying cause of death were identified by the NHANES-linked National Death Index record. The definition of cardiovascular mortality was based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (12). The public-use linked mortality file for the 1999–2014 NHANES provided follow-up time from the date of survey participation through December 31, 2015. More detailed information about the linkage methodology and analytic guidelines are available on the NCHS data linkage webpage (13).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described in accordance with the tertiles of NHR (<0.065, 0.065–0.100, and >0.100). Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables were expressed as numbers with percentages. Comparisons between the tertiles of NHR were performed using one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. The differences of survival rates according to NHR tertiles were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank test. Multivariate Cox regression models were built to investigate the independent association of NHR with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Model 1 was a crude model with no confounders. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, race, education status, smoker, and alcohol user. Model 3 was adjusted for all variables in model 2 and other confounders, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, BMI, albumin, eGFR, antihypertensive drugs, and antidiabetic drugs. Restricted cubic spline regression models were used to explore any non-linear relationship of NHR with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. For subgroup analysis, we tested the results stratified by age, sex, and history of diabetes or hypertension from fully-adjusted regression models. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0, R version 3.5.3 and the EmpowerStats software (http://www.empowerstats.com). The value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of 34,335 participants finally included in this study. The average age of this study population was 49.6 ± 18.2 years and 48.4% were men. All baseline confounders had significant differences among NHR tertiles (all p < 0.01), except for SBP, DBP, and cancer. During a median follow-up of 82 months, 4,310 (12.6%) all-cause deaths and 754 (2.2%) cardiovascular deaths occurred.

Table 1

| Total | Neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein ratio (NHR) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile1 | Tertile2 | Tertile3 | |||

| <0.065 | 0.065-0.100 | >0.100 | |||

| Number | 11,439 | 11,266 | 11,630 | ||

| Age, year | 49.6 ± 18.2 | 50.8 ± 18.0 | 49.8 ± 18.3 | 48.2 ± 18.3 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 16,601 (48.4%) | 4,568 (39.9%) | 5,510 (48.9%) | 6,523 (56.1%) | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Mexican American | 6,187 (18.0%) | 1,471 (12.9%) | 2,286 (20.3%) | 2,430 (20.9%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 16,133 (47.0%) | 4,781 (41.8%) | 5,261 (46.7%) | 6,091 (52.4%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6,691 (19.5%) | 3,454 (30.2%) | 1,881 (16.7%) | 1,356 (11.7%) | |

| Other races | 5,324 (15.5%) | 1,733 (15.1%) | 1,838 (16.3%) | 1,753 (15.1%) | |

| Education status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <9th grade | 4,352 (12.7%) | 1,213 (10.6%) | 1,519 (13.5%) | 1,620 (13.9%) | |

| 9–11th grade | 5,411 (15.8%) | 1,651 (14.4%) | 1,676 (14.9%) | 2,084 (17.9%) | |

| High school | 7,957 (23.2%) | 2,420 (21.2%) | 2,602 (23.1%) | 2,935 (25.2%) | |

| College | 9,445 (27.5%) | 3,169 (27.7%) | 3,065 (27.2%) | 3,211 (27.6%) | |

| Graduate | 7,170 (20.9%) | 2,986 (26.1%) | 2,404 (21.3%) | 1,780 (15.3%) | |

| Smoker, n (%) | 15,975 (46.5%) | 4,548 (39.8%) | 5,018 (44.5%) | 6,409 (55.1%) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol user, n (%) | 24,198 (70.5%) | 7,999 (69.9%) | 7,879 (69.9%) | 8,320 (71.5%) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 24,198 (70.5%) | 855 (7.5%) | 1,257 (11.2%) | 1,766 (15.2%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 11,722 (34.1%) | 3,599 (31.5%) | 3,807 (33.8%) | 4,316 (37.1%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 1,093 (3.2%) | 243 (2.1%) | 326 (2.9%) | 524 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 1,450 (4.2%) | 314 (2.7%) | 469 (4.2%) | 667 (5.7%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1,240 (3.6%) | 326 (2.8%) | 390 (3.5%) | 524 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 3,078 (9.0%) | 1,070 (9.4%) | 998 (8.9%) | 1,010 (8.7%) | 0.183 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.8 ± 6.6 | 26.9 ± 5.8 | 28.7 ± 6.2 | 30.7 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 124.6 ± 19.6 | 124.5 ± 20.4 | 124.6 ± 19.5 | 124.6 ± 18.9 | 0.765 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 70.0 ± 13.4 | 70.1 ± 12.9 | 70.0 ± 13.2 | 70.0 ± 14.1 | 0.571 |

| Neutrophil count,103/μl | 4.32 ± 1.81 | 2.92 ± 0.84 | 4.15 ± 0.98 | 5.85 ± 1.95 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 52.54 ± 15.85 | 64.08 ± 16.17 | 51.62 ± 11.75 | 42.08 ± 10.45 | <0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 95.1 ± 32.8 | 92.6 ± 30.4 | 95.6 ± 32.1 | 97.1 ± 35.3 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 8,773 (26.9%) | 2,644 (24.3%) | 2,887 (27.0%) | 3,242 (29.5%) | <0.001 |

| Antidiabetic drugs, n (%) | 3,029 (9.0%) | 638 (5.6%) | 984 (8.9%) | 1,407 (12.3%) | <0.001 |

| Outcomes, n (%) | |||||

| All-cause mortality | 4,310 (12.6%) | 1,262 (11.0%) | 1,372 (12.2%) | 1,676 (14.4%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 754 (2.2%) | 187 (1.6%) | 260 (2.3%) | 307 (2.6%) | <0.001 |

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

BP, blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Values are mean ± SDs or number (%).

Association of NHR With All-Cause Mortality

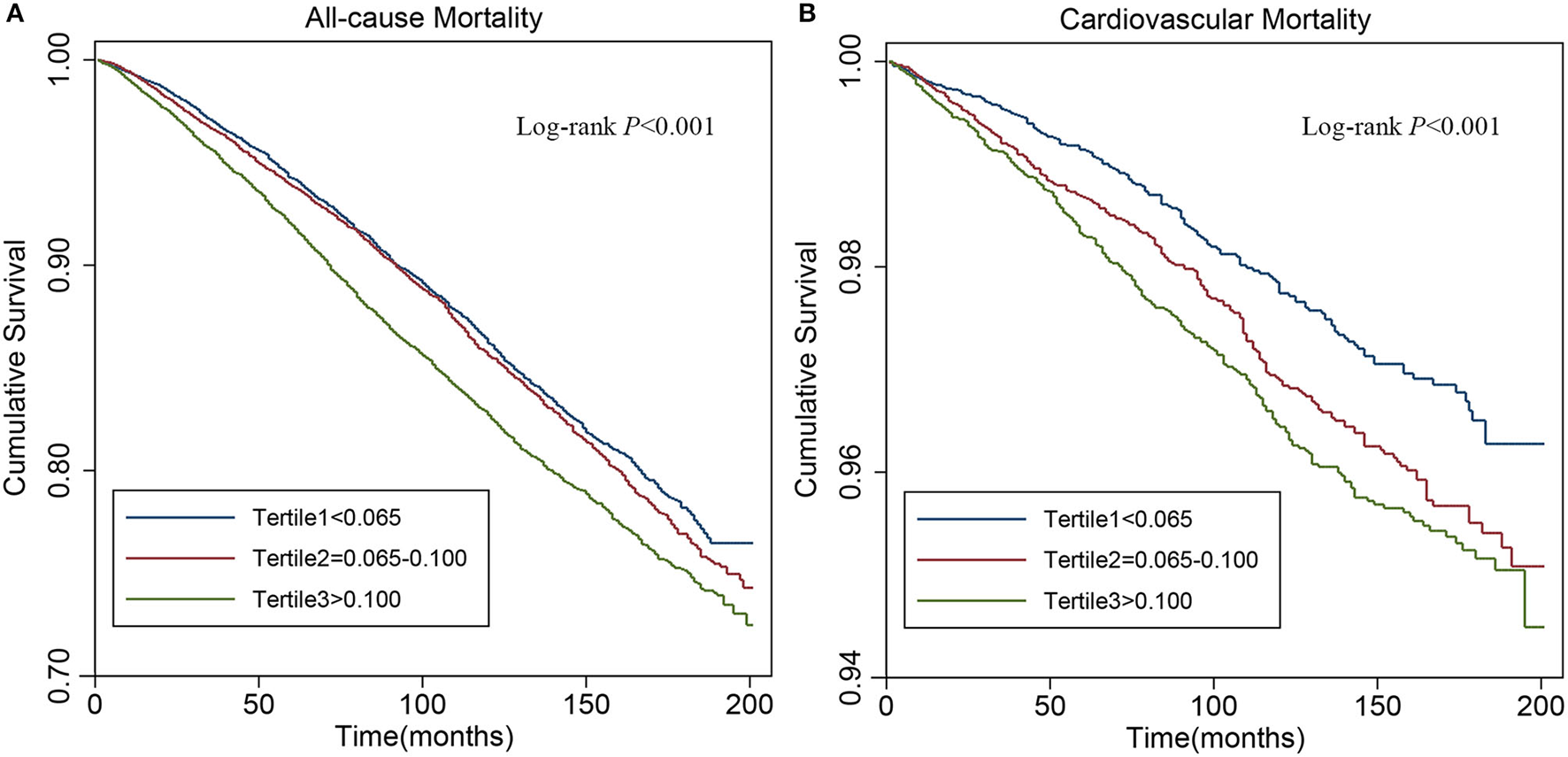

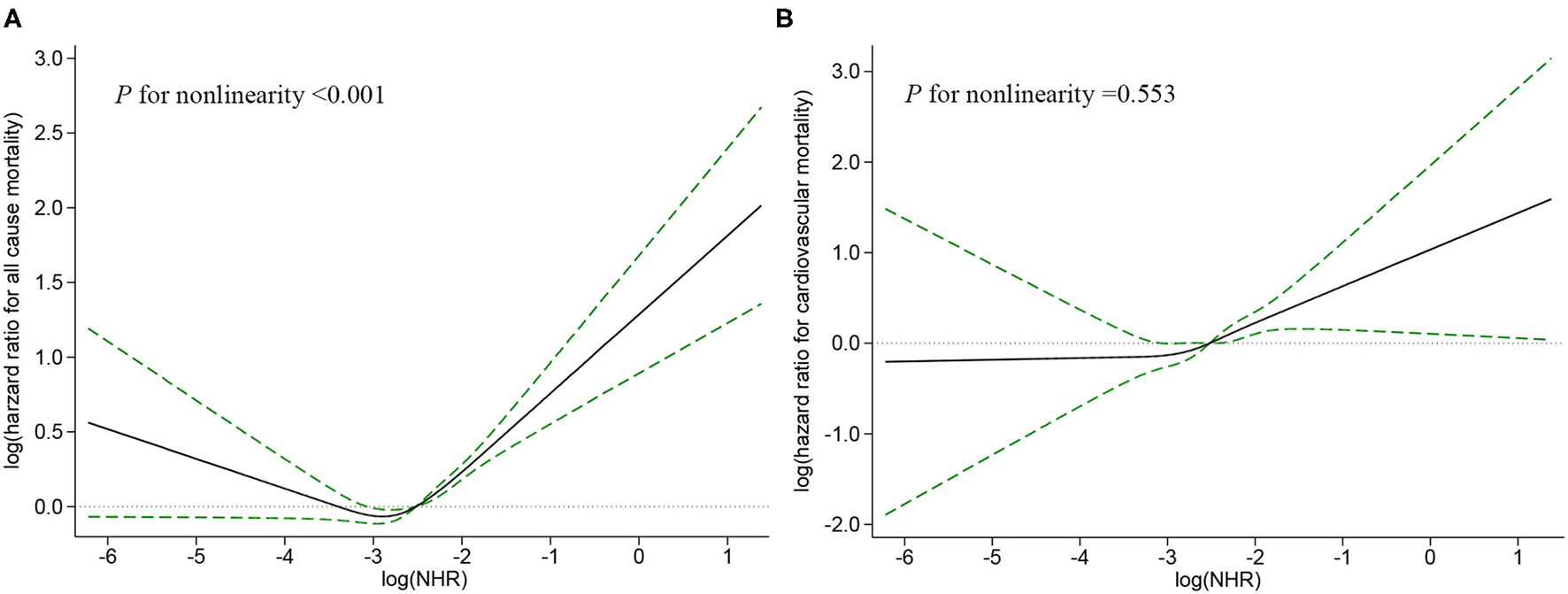

For all-cause mortality, Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed statistically significant differences in survival probabilities among the NHR tertiles (log-rank test, p < 0.001, Figure 2A). In a fully-adjusted Cox regression model (Table 2), participants in the highest tertile had 29% higher risk of death from any cause than those in the lowest tertile [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.19–1.41], while the middle tertile did not differ significantly from the lowest tertile (HR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98–1.16). The association between NHR and all-cause mortality was non-linear and U-shaped according to restricted cubic spline models (Figure 3A), and the test for non-linearity was significant (p < 0.001).

Figure 2

Kaplan–Meier analysis for all-cause (A) and cardiovascular (B) mortality by tertiles of neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHR).

Table 2

| Outcomes | Model 1 | P | Model 2 | P | Model 3 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||

| NHR tertile | ||||||

| Tertile1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Tertile2 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 0.140 | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) | 0.085 | 1.07 (0.98, 1.16) | 0.124 |

| Tertile3 | 1.27 (1.18, 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.31, 1.53) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.19, 1.41) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | ||||||

| NHR tertile | ||||||

| Tertile1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Tertile2 | 1.36 (1.13, 1.64) | 0.001 | 1.39 (1.15, 1.69) | 0.001 | 1.30 (1.06, 1.59) | 0.011 |

| Tertile3 | 1.58 (1.32, 1.89) | <0.001 | 1.80 (1.48, 2.18) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.17, 1.78) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

The multivariate cox regression analysis of NHR with cause-specific mortality.

NHR, neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Model 1: non-adjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, race, education status, smoker, and alcohol user.

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, race, education status, smoker, alcohol user, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, body mass index, albumin, estimated glomerular filtration rate, antihypertensive drugs, and antidiabetic drugs.

Figure 3

Restricted cubic spline plots of associations between NHR with all-cause (A) and cardiovascular (B) mortality in the general population. Analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, education status, smoker, alcohol user, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, body mass index (BMI), albumin, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), antihypertensive drugs, and antidiabetic drugs. The solid line and dashed line represent the log-transformed hazard ratios and corresponding 95% CIs, respectively.

Association of NHR With Cardiovascular Mortality

As shown in the Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Figure 2B), there were significant differences in the occurrence of cardiovascular mortality (log-rank test, p <0.001) among the tertiles of NHR. After fully adjusting for confounders (Table 2), the HR with 95% CIs of cardiovascular mortality for participants in the middle and highest tertile compared with those in the lowest participants were 1.30 (1.06–1.59) and 1.44 (1.17–1.78), respectively. The restricted cubic spline curve indicated that NHR was linearly associated with cardiovascular mortality (p for non-linearity = 0.553, Figure 3B).

Subgroup Analysis

As shown in Table 3, a stratified analysis by age, sex, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, further explored the relationship between NHR and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Except for participants <60 years old and individuals with diabetes mellitus, participants in the highest tertile had a higher hazard for all-cause death than those in the lowest tertile (all p < 0.05). In addition, there were significant interactions between NHR with sex (p for interaction = 0.040) for all-cause mortality that female participants had a stronger association between NHR and all-cause mortality than male participants. Although no significant interactions with NHR for cardiovascular mortality were found, the association between NHR and cardiovascular death was significant among older female people, those with hypertension, and those without diabetes mellitus.

Table 3

| Tertile1 | Tertile2 | Tertile3 | P-t | P-int | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | |||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Age | 0.230 | ||||

| <60 years | Reference | 0.96 (0.80−1.16) | 1.07 (0.89−−1.29) | 0.395 | |

| ≥60 years | Reference | 1.08 (0.99−1.18) | 1.32 (1.20−−1.45)*** | <0.001 | |

| Sex | 0.040 | ||||

| Female | Reference | 1.12 (1.00−1.26)* | 1.45 (1.28−1.64)*** | <0.001 | |

| Male | Reference | 1.01 (0.90−1.13) | 1.18 (1.05−1.32)** | 0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.529 | ||||

| No | Reference | 1.07 (0.98−1.17) | 1.34 (1.22−1.47)*** | <0.001 | |

| Yes | Reference | 1.06 (0.87−1.30) | 1.18 (0.97−1.43) | 0.070 | |

| Hypertension | 0.093 | ||||

| No | Reference | 1.01 (0.90−1.14) | 1.18 (1.05−1.33)* | 0.007 | |

| Yes | Reference | 1.12 (1.00−1.26) | 1.39 (1.24−1.56)*** | <0.001 | |

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||||

| Age | 0.147 | ||||

| <60 years | Reference | 1.74 (0.94−3.23) | 1.49 (0.80−2.80) | 0.326 | |

| ≥60 years | Reference | 1.26 (1.02−1.56)* | 1.42 (1.14−1.77)** | 0.002 | |

| Sex | 0.768 | ||||

| Female | Reference | 1.39 (1.04−1.87)* | 1.78 (1.29−2.45)*** | <0.001 | |

| Male | Reference | 1.27 (0.95−1.68) | 1.31 (0.99−1.74) | 0.085 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.757 | ||||

| No | Reference | 1.34 (1.06−1.68)* | 1.52 (1.20−1.94)*** | 0.001 | |

| Yes | Reference | 1.23 (0.81−1.90) | 1.30 (0.86−1.97) | 0.250 | |

| Hypertension | 0.479 | ||||

| No | Reference | 1.25 (0.91−1.71) | 1.40 (1.01−1.94)* | 0.048 | |

| Yes | Reference | 1.40 (1.07−1.82)* | 1.51 (1.16−1.98)** | 0.004 |

Subgroup analysis for the association between NHR and cause-specific mortality.

NHR, neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. Adjusted for age, sex, race, education status, smoker, alcohol user, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, body mass index, albumin, estimated glomerular filtration rate, antihypertensive drugs, and antidiabetic drugs. p-t, p for trend; p-int, p for interaction.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the predicative value of NHR for long-term clinical outcomes among the general adult population of the United States. Our results revealed that NHR was independently associated with the risk of mortality from all-cause and CVD. Further analyses suggested that NHR had a non-linear association with all-cause mortality that was more profound among female participants and a linear association with cardiovascular mortality, which remained significant in older female people, those with hypertension, and those without diabetes mellitus.

Recently, increasing numbers of studies have focused on the potential risk markers of long-term clinical outcomes, especially the composite predictors of hematological parameters. These markers derived from routine blood tests are affordable and easily available. Compared with single parameters, the ratio of different parameters can provide comprehensive information and have comparable prediction ability (1). For instance, the ratios of neutrophil to lymphocyte (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte (PLR), monocyte to lymphocyte (MLR), monocyte to HDL-C (MHR), lymphocyte to HDL-C (LHR), triglyceride to HDL-C (THR), and LDL-C to HDL-C are well-studied predictors of mortality and specific-cause mortality (14–20).

Although NHR is a relatively novel indicator, previous studies have found that NHR has a better prognostic value than the above indicators (1, 8, 9). It has several strengths. First, poor outcomes have complicated the pathological processes where both inflammatory reaction and abnormal lipid metabolism are involved. Prognostic indicators, such as NLR, PLR, MLR, THR, and LDL-C/HDL-C could only reflect a single contributor at a time. Nevertheless, NHR can not only simultaneously present the inflammatory status and the lipid metabolism but also indicate the interaction between neutrophils and HDL-C. Second, neutrophils account for the major portion of white blood cells. Accordingly, it had better prediction of cardiovascular mortality and long-term mortality than monocytes and lymphocytes (21–23). Third, neutrophils have been considered as the first line of inflammatory response and are involved in the activation of monocytes and lymphocytes (3, 24). These crucial roles of neutrophils allow NHR to offer a better prognostic potential than MHR or LHR.

However, the prognostic ability of NHR with respect to mortality has not been fully explored. As far as we know, only two previous retrospective studies have explored the prognostic importance of NHR for long-term mortality in specific populations (1, 9). The first study evaluated 528 patients (age range: 65–85 years) with acute myocardial infarction and reported that NHR was a latent predictor of all-cause mortality over a median of 679.50 days, which was superior to MHR and LDL-C/HDL-C (1). The second study followed up 554 patients diagnosed with myocardial infarction with at least one total coronary artery occlusion for over a median of 520 days, and found that higher NHR was associated with increasing risk of cardiovascular mortality. In addition, NHR offered better prediction than other ratios, such as PLR, NLR, MHR, THR, LHR, and HDL-C/LDL-C (9). In accordance with these studies, we demonstrated that NHR was a potential prognostic marker of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the general population over a longer follow-up.

Several interpretations can account for the correlation between higher NHR and poorer prognosis. Neutrophils were abundantly identified in the advanced atherosclerotic plaques and its count was positively associated with the histopathologic features of rupture-prone atherosclerotic lesions (25). The preformed granule proteins released from neutrophils, such as myeloperoxidase (MPO) and matrix metalloproteinases, contribute to severe inflammatory function that precede myocardial injury (25, 26). Moreover, the neutrophil activation and consecutive interactions with platelets contribute to atherothrombosis, thereby causing cardiovascular mortality (27). Activated neutrophils can also mediate HDL oxidation and impair cholesterol efflux capacity by possessing oxidant-generating enzymes, such as MPO, NADPH oxidase, and nitric oxide synthase (28). By contrast, HDL-C inhibits neutrophil activation, adhesion, proliferation, and migration, and anti-inflammatory effect was strongly associated with the abundance of lipid rafts (29). In addition, HDL-C can promote the angiogenesis on endothelial cells and inhibit apoptosis on cardiomyocytes to exert cardioprotective effects (30). Previous studies have shown that the higher NHR was associated with severe stroke characterized by higher mortality (8) and more culprit lesions that could cause more myocardial damage and increased cardiovascular mortality (9). Above all, this is explainable that the increased NHR attributed to both the increased neutrophil count and decreased HDL-C level was associated with poorer outcomes.

Our study added a novel insight in that there was a non-linear association between NHR and all-cause mortality, although the underlying mechanism remains unclear. One plausible explanation is that the concentrations of HDL-C were higher among participants with lower NHR in this cohort. In fact, recent epidemiological studies found that HDL-C was related to all-cause mortality in a U-shaped pattern such that both the lower and higher HDL-C concentrations could increase the risk of all-cause mortality (31–33). Huang et al. found that HDL-C had a concentration-related biphasic effect and could lost protective effect at high concentrations (34). Moreover, genetic variants may also play an adverse role in the health status and lead to increased risk of mortality among individuals with high level of HDL-C (35). In addition, we noted that the average age and the prevalence of cancer were higher among those with lower NHR, suggesting perhaps that age and cancer are likely to explain the increased risk of death in this group. Thus, additional investigation is required to confirm the influence of age and cancer on the association between lower NHR and increased risk of all-cause mortality.

Our study has several strengths. First, we provided more evidence than is currently available about the prognostic role of NHR for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population from a large-scale, prospective cohort study. Second, we performed both qualitative and quantitative analyses to explore the relationship between NHR and survival. Last, we showed the shape of the relationship of NHR with long-term outcomes via the restricted cubic spline model for the first time.

Our study has some limitations. First, NHR was only measured at baseline, which might not reflect the time-dependent association of NHR with long-term outcomes. Second, some variables, such as lifestyle factors and medical history were self-reported, which might have caused recall bias. Third, although these results were adjusted for covariates as far as possible, we could not exclude the possible residual confounding effects of unmeasured or non-included variables. Fourth, there were no direct comparisons with other inflammatory indexes, such as C-reactive protein, because of the limited data of the NHANES. Last, our data were derived from the U.S. database, so it may not be generalizable to other regions or populations. Thus, more epidemiologic studies are needed to establish the predictive value of NHR in clinical practice.

Conclusions

In summary, our study indicated that NHR was independently associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population, which supported that NHR might be a potential predictor of long-term clinical outcomes.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Board of National Center for Health Statistics. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MJ contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing-original draft of the manuscript. JS responsible for software and data curation. HZ performed visualization. ML and ZS contributed to validation. WS performed writing–review and editing. XK contributed to conceptualization and supervision. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and reading and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the workforce and participants of the NHANES study for their valuable contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Huang JB Chen YS Ji HY Xie WM Jiang J Ran LS et al . Neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein ratio has a superior prognostic value in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: a comparison study. Lipids Health Dis. (2020) 19:59. 10.1186/s12944-020-01238-2

2.

Chen T Chen H Xiao H Tang H Xiang Z Wang X et al . Comparison of the value of neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and lymphocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio for predicting metabolic syndrome among a population in the southern coast of China. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2020) 13:597–605. 10.2147/DMSO.S238990

3.

Moriya J . Critical roles of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Cardiol. (2019) 73:22–7. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.05.010

4.

Soehnlein O . Multiple roles for neutrophils in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. (2012) 110:875–88. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.257535

5.

Assmann G Gotto AM Jr . HDL cholesterol and protective factors in atherosclerosis. Circulation. (2004) 109:III8–14. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131512.50667.46

6.

Yang Y Han K Park SH Kim MK Yoon KH Lee SH . High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cause-specific mortality: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. J Lipid Atheroscler. (2021) 10:74–87. 10.12997/jla.2021.10.1.74

7.

Navaneethan SD Schold JD Walther CP Arrigain S Jolly SE Virani SS et al . High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and causes of death in chronic kidney disease. J Clin Lipidol. (2018) 12:1061–1071.e1067. 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.03.085

8.

Chen G Yang N Ren J He Y Huang H Hu X et al . Neutrophil counts to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio: a potential predictor of prognosis in acute ischemic stroke patients after intravenous thrombolysis. Neurotox Res. (2020) 38:1001–9. 10.1007/s12640-020-00274-1

9.

Ozgeyik M Ozgeyik MO . Long-term prognosis after treatment of total occluded coronary artery is well predicted by neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein ratio: a comparison study. Kardiologiia. (2021) 61:60–7. 10.18087/cardio.2021.7.n1637

10.

Liao S Wu N Gong D Tang X Yin T Zhang H et al . Association of aldehydes exposure with obesity in adults. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2020) 201:110785. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110785

11.

Levey AS Coresh J Greene T Stevens LA Zhang YL Hendriksen S et al . Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. (2006) 145:247–54. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004

12.

Kim D Konyn P Sandhu KK Dennis BB Cheung AC Ahmed A . Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is associated with increased all-cause mortality in the United States. J Hepatol. (2021). 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.035

13.

National Center for Health Statistics Centers for Disease Control Prevention . The Linkage of National Center for Health Statistics Survey Data to the National Death Index-−2015 Linked Mortality File (LMF): Methodology Overview and Analytic Considerations. (2019). Available online at: www.cdc.gov/nchsdata/datalinkage/LMF2015_Methodology_Analytic_Considerations.pdf (accessed April 11, 2019).

14.

Fest J Ruiter TR Groot Koerkamp B Rizopoulos D Ikram MA van Eijck CHJ et al . The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with mortality in the general population: The Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol. (2019) 34:463–70. 10.1007/s10654-018-0472-y

15.

Chen J Zhong Z Shi D Li J Li B Zhang R et al . Association between monocyte count to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and mortality in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2021) 31:2081–8. 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.03.014

16.

Xiang F Chen R Cao X Shen B Liu Z Tan X et al . Monocyte/lymphocyte ratio as a better predictor of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients: A prospective cohort study. Hemodial Int. (2018) 22:82–92. 10.1111/hdi.12549

17.

Lin T Xia X Yu J Qiu Y Yi C Lin J et al . The predictive study of the relation between elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and mortality in peritoneal dialysis. Lipids Health Dis. (2020) 19:51. 10.1186/s12944-020-01240-8

18.

Chang TI Streja E Soohoo M Kim TW Rhee CM Kovesdy CP et al . Association of serum triglyceride to HDL cholesterol ratio with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2017) 12:591–602. 10.2215/cjn.08730816

19.

Dong G Huang A Liu L . Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and prognosis in STEMI: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. (2021) 51:e13386. 10.1111/eci.13386

20.

Chen H Xiong C Shao X Ning J Gao P Xiao H et al . Lymphocyte To high-density lipoprotein ratio as a new indicator of inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2019) 12:2117–23. 10.2147/DMSO.S219363

21.

o Hartaigh B Bosch JA Thomas GN Lord JM Pilz S Loerbroks A et al . Which leukocyte subsets predict cardiovascular mortality? From the LUdwigshafen RIsk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) Study. Atherosclerosis. (2012) 224:161–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.04.012

22.

Dragu R Huri S Zukermann R Suleiman M Mutlak D Agmon Y et al . Predictive value of white blood cell subtypes for long-term outcome following myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. (2008) 196:405–12. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.022

23.

Horne BD Anderson JL John JM Weaver A Bair TL Jensen KR et al . Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk?J Am Coll Cardiol. (2005) 45:1638–43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.054

24.

Rosales C . Neutrophils at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. J Leukoc Biol. (2020) 108:377–96. 10.1002/JLB.4MIR0220-574RR

25.

Ionita MG van den Borne P Catanzariti LM Moll FL de Vries JP Pasterkamp G et al . High neutrophil numbers in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques are associated with characteristics of rupture-prone lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2010) 30:1842–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209296

26.

Goldmann BU Rudolph V Rudolph TK Holle AK Hillebrandt M Meinertz T et al . Neutrophil activation precedes myocardial injury in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Free Radic Biol Med. (2009) 47:79–83. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.004

27.

Pircher J Engelmann B Massberg S Schulz C . Platelet-neutrophil crosstalk in atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost. (2019) 119:1274–82. 10.1055/s-0039-1692983

28.

Smith CK Vivekanandan-Giri A Tang C Knight JS Mathew A Padilla RL et al . Neutrophil extracellular trap-derived enzymes oxidize high-density lipoprotein: an additional proatherogenic mechanism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2014) 66:2532–44. 10.1002/art.38703

29.

Murphy AJ Woollard KJ Suhartoyo A Stirzaker RA Shaw J Sviridov D et al . Neutrophil activation is attenuated by high-density lipoprotein and apolipoprotein A-I in in vitro and in vivo models of inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2011) 31:1333–41. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226258

30.

Gomaraschi M Calabresi L Franceschini G . Protective Effects of HDL against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Front Pharmacol. (2016) 7:2. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00002

31.

Bowe B Xie Y Xian H Balasubramanian S Zayed MA Al-Aly Z . High density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of all-cause mortality among US veterans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol: CJASN. (2016) 11:1784–93. 10.2215/CJN.00730116

32.

Chen CL Liu XC Liu L Lo K Yu YL Huang JY et al . U-shaped association of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive population. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2020) 13:2013–25. 10.2147/rmhp.S272624

33.

Li ZH Lv YB Zhong WF Gao X Byers Kraus V Zou MC et al . High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2019) 104:3370–8. 10.1210/jc.2018-02511

34.

Huang CY Lin FY Shih CM Au HK Chang YJ Nakagami H et al . Moderate to high concentrations of high-density lipoprotein from healthy subjects paradoxically impair human endothelial progenitor cells and related angiogenesis by activating Rho-associated kinase pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2012) 32:2405–17. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248617

35.

Madsen CM Varbo A Nordestgaard BG . Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality in men and women: two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38:2478–86. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx163

Summary

Keywords

neutrophil, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, NHANES

Citation

Jiang M, Sun J, Zou H, Li M, Su Z, Sun W and Kong X (2022) Prognostic Role of Neutrophil to High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio for All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in the General Population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:807339. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.807339

Received

03 November 2021

Accepted

10 January 2022

Published

08 February 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Saskia C. A. De Jager, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Yi Zhang, Tongji University, China; Saskia Haitjema, University Medical Center Utrecht, Netherlands; Kuibao Li, Capital Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Jiang, Sun, Zou, Li, Su, Sun and Kong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiangqing Kong kongxq@njmu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to General Cardiovascular Medicine, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.