Abstract

Objectives:

This study aimed to investigate the differences in the characteristics, management, and clinical outcomes of patients with and that of those without coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection who had ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Methods:

Databases including Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase were searched up to July 2021. Observational studies that reported on the characteristics, management, or clinical outcomes and those published as full-text articles were included. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of all included studies.

Results:

A total of 27,742 patients from 13 studies were included in this meta-analysis. Significant delay in symptom onset to first medical contact (SO-to-FMC) time (mean difference = 23.42 min; 95% CI: 5.85–40.99 min; p = 0.009) and door-to-balloon (D2B) time (mean difference = 12.27 min; 95% CI: 5.77–18.78 min; p = 0.0002) was observed in COVID-19 patients. Compared to COVID-19 negative patients, those who are positive patients had significantly higher levels of C-reactive protein, D-dimer, and thrombus grade (p < 0.05) and showed more frequent use of thrombus aspiration and glycoprotein IIbIIIa (Gp2b3a) inhibitor (p < 0.05). COVID-19 positive patients also had higher rates of in-hospital mortality (OR = 5.98, 95% CI: 4.78–7.48, p < 0.0001), cardiogenic shock (OR = 2.75, 95% CI: 2.02–3.76, p < 0.0001), and stent thrombosis (OR = 5.65, 95% CI: 2.41–13.23, p < 0.0001). They were also more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) (OR = 4.26, 95% CI: 2.51–7.22, p < 0.0001) and had a longer length of stay (mean difference = 4.63 days; 95% CI: 2.56–6.69 days; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

This study revealed that COVID-19 infection had an impact on the time of initial medical intervention for patients with STEMI after symptom onset and showed that COVID-19 patients with STEMI were more likely to have thrombosis and had poorer outcomes.

Introduction

An eventual pandemic brought by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) resulted in plenty of deaths and has had a strong impact on the world's healthcare system (1–3). Although the disease is predominantly characterized by respiratory symptoms, including pneumonia, dyspnea, and cough (4), various extrapulmonary features, such as myocardial damage, arrhythmia, thrombotic events, and renal injury have also been observed (5, 6).

A type of heart attack called ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is usually caused by thrombotic occlusion at the site of a ruptured plaque in the coronary artery (7). Although the survival rates of STEMI patients have improved, it is still associated with high morbidity and mortality worldwide with a 1-year mortality rate of up to 10% (8–10). The COVID-19 pandemic may lead to a decrease in the number of STEMI admissions and could have a significant impact on the reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI (11, 12). The tendency of patients with COVID-19 to be predisposed to cardiac arrest and coronary thrombosis due to increased inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, and SARS-CoV-2 invasion of cardiomyocytes has been reported (13–15). Moreover, data regarding the characteristics, management strategies, and clinical outcomes including in-hospital mortality and cardiogenic shock in patients presenting with STEMI concurrent with COVID-19 infection are limited (16). Accordingly, we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the characteristics, management, and clinical outcomes between the COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients concomitant STEMI.

Methods

Literature Search

We performed a literature search using databases including Web of Science (Beijing), PubMed (Bethesda), Cochrane Library (UK), and Embase (Amsterdam) for relevant papers without language limitation on July 31, 2021. The search strategy included a mix of MeSH and free-text terms relevant to the critical concept of “STEMI” and “COVID-19” (Table 1). The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered at PROSPERO under the number CRD42021283880.

Table 1

| Database | Searching key words | |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (1) “ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction”: 9451 | (10) SARS-CoV-2: 106826 |

| (2) “ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction”: 317 | (11) “Coronavirus disease 19”: 1603 | |

| (3) STEMI: 28060 | (12) “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2”: 16865 | |

| (4) “Acute myocardial infarction”: 61630 | (13) “novel coronavirus”: 9766 | |

| (5) AMI: 25165 | (14) “2019 novel coronavirus”: 1550 | |

| (6) “Acute coronary syndromes”: 13188 | (15) #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7: 208085 | |

| (7) ACS: 116546 | (16) #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14: 169136 | |

| (8) “SARSCoV-2 pandemic”: 120 | (17) #15 and #16: 1340 | |

| (9) COVID-19: 168784 | ||

| Web of science | (1) “ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction”: 17531 | (10) SARS-CoV-2: 127748 |

| (2) “ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction”: 1899 | (11) “Coronavirus disease 19”: 3460 | |

| (3) STEMI: 23388 | (12) “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2”: 58794 | |

| (4) “Acute myocardial infarction”: 145384 | (13) “novel coronavirus”: 14678 | |

| (5) AMI: 44201 | (14) “2019 novel coronavirus”: 2224 | |

| (6) “Acute coronary syndromes”: 27560 | (15) #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7: 248982 | |

| (7) ACS: 58425 | (16) #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14: 262441 | |

| (8) “SARSCoV-2 pandemic”: 25 | (17) #15 and #16: 1098 | |

| (9) COVID-19: 248069 | ||

| Cochrane library | (1) “ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction”: 4031 | (10) SARS-CoV-2: 322 |

| (2) “ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction”: 156 | (11) “Coronavirus disease 19”: 43 | |

| (3) STEMI: 3616 | (12) “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2”: 631 | |

| (4) “Acute myocardial infarction”: 9325 | (13) “novel coronavirus”: 497 | |

| (5) AMI: 3603 | (14) “2019 novel coronavirus”: 55 | |

| (6) “Acute coronary syndromes”: 2562 | (15) #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7: 19050 | |

| (7) ACS: 4853 | (16) #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14: 6784 | |

| (8) “SARSCoV-2 pandemic”: 52 | (17) #15 and #16: 31 | |

| (9) COVID-19: 6666 | ||

| Embase | ('acute myocardial infarction':ti,ab,kw OR ami:ti,ab,kw OR 'acute coronary syndromes':ti,ab,kw OR acs:ti,ab,kw OR 'st segment elevation myocardial infarction':ti,ab,kw OR 'st elevated myocardial infarction':ti,ab,kw OR stemi:ti,ab,kw) AND ('sarscov-2 pandemicor COVID-19':ti,ab,kw OR 'sars cov 2':ti,ab,kw OR 'coronavirus disease 19':ti,ab,kw OR 'novel coronavirus':ti,ab, kw OR 'severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2':ti,ab,kw) AND [1-1-1900]/sd NOT [1-8-2021]/sd; result = 233 | |

Search strategy.

Study Selection

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) studies involving STEMI patients; (ii) the exposure group included patients diagnosed with COVID-19 using PCR test or had a high index of clinical suspicion, and the control group included patients without COVID-19; (iii) studies that reported at least one of the following information: characteristics, management strategy, or clinical outcomes; (iv) relevant cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case-control studies. Two independent authors screened the titles and abstracts of all relevant studies and identified whether they met the inclusion criteria by reviewing the full text of each potential study. Any discrepancy was resolved through consensus with a third author.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Relevant data from all included studies were extracted by two authors independently, and any disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third author. The following data were extracted: authors, publication year, country, study design, study subject, sample size, mean age of patients/subjects, sex, comparison period, participant characteristics, management strategies, and clinical outcomes. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), which includes participant selection, comparability, and outcome, was used to assess the quality of the included studies. Likewise, all included studies were rated by two authors independently, and any discrepancy was adjudicated by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

We used Review Manager 5.4 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Cochrane Collaboration, 2020, Denmark) to perform the statistical analysis. If studies only reported median values and interquartile ranges (IQR), means and SDs were calculated according to the Box-Cox method (17). Categorical variables were presented as odds ratios (ORs), including 95% CIs, and continuous variables were presented as the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD), including 95% CI. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and the p-value of the chi-square test. The I2 statistic > 50% indicates significant heterogeneity. The choice between the fixed and random effects models depended on the comparability among the studies. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was interpreted to be statistically significant. The risk of publication bias was evaluated using the funnel plots.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

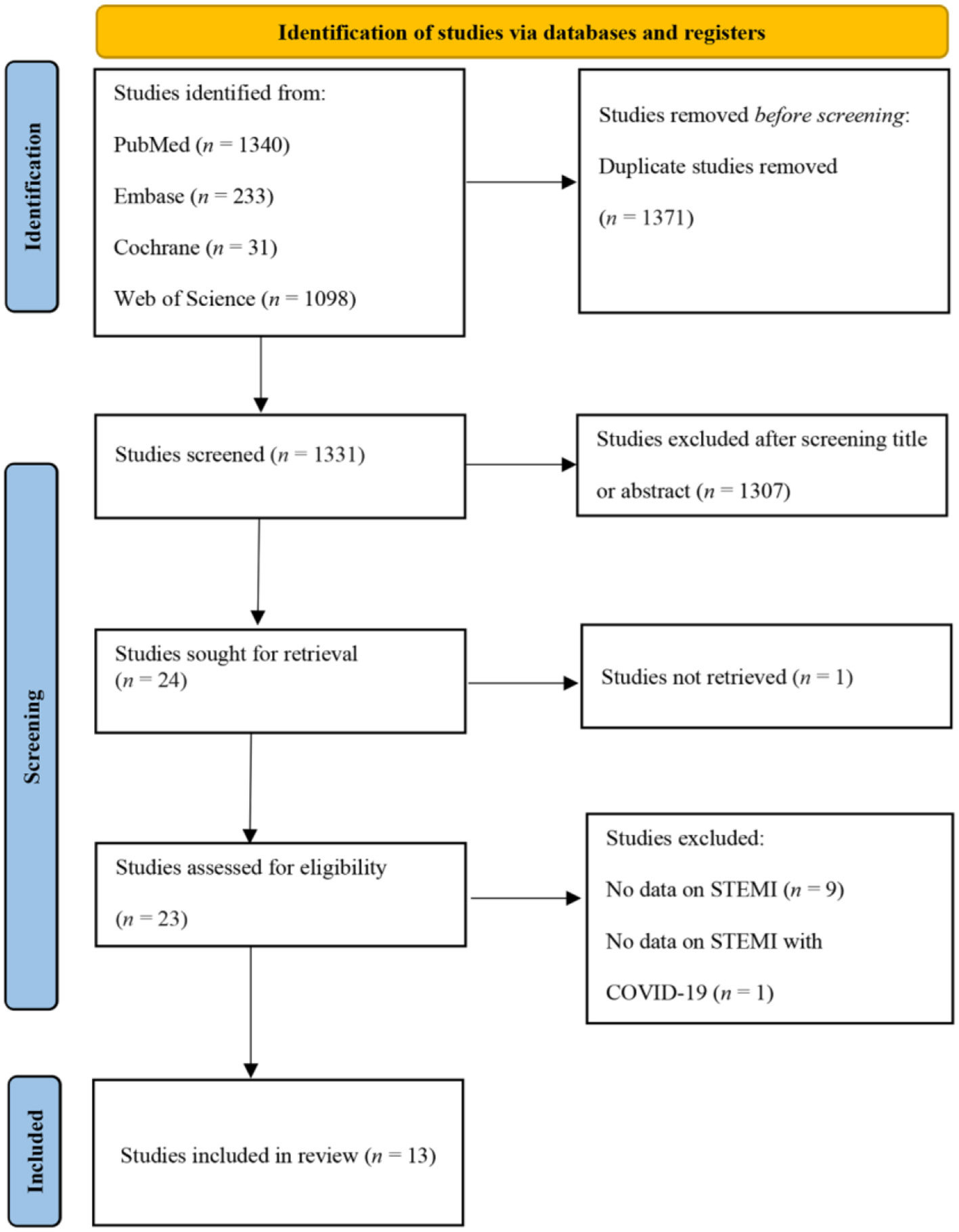

A total of 2,702 articles were retrieved through electronic database searches, of which 1,371 were duplicates. After screening the titles and abstracts, 24 potential articles were assessed for eligibility after a full-text review, and 13 articles (18–30) with a total of 27,742 patients were finally included (Figure 1). A summary of the main characteristics of these 13 studies and the baseline characteristics of all study subjects is presented in Tables 2A,B. One study originated from Poland (19), two each from the United Kingdom (24, 28), France (18, 21), Turkey (20, 30), Italy (25, 26), and Spain (27, 29), and the remaining two studies (22, 23) were international studies. The NOS score for all included studies varied from 5 to 8 points.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2A

| References | Country | Study design | Study group | Participants characteristics | Comparison period | COVID-19 diagnosis approach/time to diagnosis | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popovic et al. (18) | France | Monocentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 11, age 63.6 ± 17.4 years, 63.9% males | 26/2/2020–10/5/2020 | RT-PCR or typical clinical features plus CT results/NA | D2B time, Laboratory values, Primary angioplasty, MINOCA, Stent implantation, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 72, age 62.5 ± 12.6 years, 73.6% males | 26/2/2020–10/5/2020 | |||||

| Siudak et al. (19) | Poland | Multicentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 145, age 63.19 ± 12.55 years, 71.33% males | 13/3/2020–13/5/2020 | Swabs for molecular RT-PCR testing/NA | SO-to-FMC time |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 2276, age 65.43 ± 12.23 years, 67.65% males | 13/3/2020–13/5/2020 | |||||

| Kiris et al. (20) | Turkey | Multicentric cross-sectional study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 65, age 66.8 ± 12.0 years, 68% males | 11/3/2020–15/5/2020 | Nasal/pharyngeal swabs or semptoms plus radiological imaging/NA | SO-to-FMC time, Laboratory values, Primary angioplasty, Thrombus aspiration, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, Baseline thrombus grade, Modified thrombus grade, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality, Bleeding, Stent thrombosis, Cardiogenic shock |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 668, age 60.0 ± 12.3 years, 78% males | 11/3/2020–15/5/2020 | |||||

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | France | Multicentric cross-sectional study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 17, age 63.4 ± 13.2 years, 70% males | 1/4/2020–22/4/2020 | RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal samples/NA | Laboratory values, Primary angioplasty, Thrombus aspiration, MINOCA, Stent implantation, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, In-hospital mortality |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 99, age 63.8 ± 13.9 years, 67% males | 1/4/2020–22/4/2020 | |||||

| Garcia et al. (22) | USA & Canada | Multicentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 230, 71% males | 1/1/2020–6/12/2020 | Comfirmed COVID+ by any commercially available test/NA | D2B time, Primary angioplasty, MINOCA, In-hospital mortality, LOS |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 460, 68% males | 1/2015–12/2019 | |||||

| Kite et al. (23) | Data from 55 international centers | Multicentric corhort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 144, age 63.1 ± 12.6 years, 77.8% males | 1/3/2020–31/7/2020 | RT-PCR or clinical status plus CXR or CT findings/NA | D2B time, Laboratory values, Thrombus aspiration, In-hospital mortality, Bleeding, Cardiogenic shock, LOS |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 24961, age 65.6 ± 13.4 years, 72.2% males | 2018–2019 | |||||

| Little et al. (24) | UK | Multicentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 46, age 61.80 ± 7.95 years, 80.4% males | 1/3/2020–30/4/2020 | RT-PCR on oro/nasopharyngeal throat swabs or typical symptoms plus radiographic appearances and characteristic blood test/NA | D2B time, Laboratory values, Thrombus aspiration, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality, Cardiogenic shock, ICU admission, LOS |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 302, age 64.18 ± 13.41 years, 79.8% males | 1/3/2020–30/4/2020 | |||||

| Marfella et al. (25) | Italy | Multicentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 46, age 56.13 ± 6.21 years, 67.4% males | 2/2020–11/2020 | RT-PCR on nasal/pharyngeal swabs/NA | D2B time, Laboratory values, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, Modified thrombus grade, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality, LOS, ICU admission, Cardiogenic shock |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 130, age 68.43 ± 6.46 years, 66.2% males | 2/2020–11/2020 | |||||

| Pellegrini et al. (26) | Italy | Monocentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 24, age 69.63 ± 11.00 years, 83.3% males | 8/3/2020–20/4/2020 | RT-PCR on nasal swab or endotracheal aspirate/3–6 h | Thrombus aspiration, MINOCA, Stent implantation, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, In-hospital mortality, Cardiogenic shock, Bleeding |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 26, age 64.65 ± 13.04 years, 84.6% males | 8/3/2020–20/4/2020 | |||||

| Rodriguez-Leor et al. (27) | Spain | Multicentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 91, age 64.8 ± 11.8 years, 84.4% males | 14/3/2020–30/4/2020 | PCR assay/NA | SO-to-FMC time, Primary angioplasty, Thrombus aspiration, MINOCA, Stent implantation, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality, Cardiogenic shock, Stent thrombosis, bleeding |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 919, age 62.5 ± 13.1 years, 78.4% males | 14/3/2020–30/4/2020 | |||||

| Choudry et al. (28) | UK | Monocentric cohort study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 39, age 61.7 ± 11.0 years, 84.6% males | 1/3/2020–20/5/2020 | PT-PCR on nasal/ pharyngeal swabs/NA | D2B time, Laboratory values, Primary angioplasty, Thrombus aspiration, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, Baseline thrombus grade, Modified thrombus grade, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality, Stent thrombosis |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 76, age 61.7 ± 12.6 years, 75% males | 1/3/2020–20/5/2020 | |||||

| Blasco et al. (29) | Spain | Monocentric cross-sectional study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 5, age 62 ± 14 years, 80% males | 23/3/2020–11/4/2020 | RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal and throat swab samples/NA | Laboratory values |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 50, age 58 ± 12 years, 88% males | 7/2015–12/2015 | |||||

| Güler et al. (30) | Turkey | Monocentric cross-sectional study | COVID-19 STEMI | n = 62, age 60.2 ± 9.5 years, 66.1% males | 11/3/2020–10/1/2021 | RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs / NA | SO-to-FMC time, D2B time, Laboratory values, Thrombus aspiration, Gp2b3a inhibitor use, Baseline thrombus grade, TIMI status, In-hospital mortality, ICU admission, LOS |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | n = 64, age 63 ± 8 years, 70.3% males | 11/3/2020–10/1/2021 |

Characteristics of included studies.

UK, United Kingdom; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; D2B, door to balloon; MINOCA, myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; SO-to-FMC, symptom onset to first medical contact; LOS, length of stay; ICU, intensive care unit; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; CT, computed tomography; CXR, chest x-ray.

Table 2B

| References | Study group | Total subjects (n) | Age (years) (mean ±SD) | Male (%) | Body mass index (kg/m2) | Diabetes mellitus (%) | Hypertension (%) | Dyslipidemia (%) | Smoking (%) | Multivessel desease (%) | Previous myocardial infarction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popovic et al. (18) | COVID-19 STEMI | 11 | 63.6 ± 17.4 | 63.9 | 25.1 ± 8.1 | 18.2 | 45.5 | 27.3 | 36.4 | 0 | NA |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 72 | 62.5 ± 12.6 | 73.6 | 27.02 ± 4.8 | 19.4 | 43.1 | 38.9 | 55.6 | 12.5 | NA | |

| Siudak et al. (19) | COVID-19 STEMI | 145 | 63.19 ± 12.55 | 71.33 | NA | 14.48 | 46.21 | NA | 37.24 | NA | 12.41 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 2,276 | 65.43 ± 12.23 | 67.65 | NA | 16.86 | 57.55 | NA | 31.08 | NA | 15.94 | |

| Kiris et al. (20) | COVID-19 STEMI | 65 | 66.8 ± 12.0 | 68 | NA | 26 | 48 | NA | 34 | 44 | NA |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 668 | 60.0 ± 12.3 | 78 | NA | 29 | 42 | NA | 33 | 40 | NA | |

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | COVID-19 STEMI | 17 | 63.4 ± 13.2 | 70 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30.7 | NA |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 99 | 63.8 ± 13.9 | 67 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 61.2 | NA | |

| Garcia et al. (22) | COVID-19 STEMI | 230 | 18–55 yrs: 23%; 55–65 yrs: 32%; 66–75 yrs: 28%; >75 yrs: 17% | 71 | 29.3 ± 7.6 | 46 | 73 | 46 | 44 | 0 | 13 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 460 | 18–55 yrs: 26%; 55–65 yrs: 30%; 66–75 yrs: 27%; >75 yrs: 17% | 68 | 29.5 ± 6.4 | 28 | 69 | 60 | 59 | 16 | 24 | |

| Kite et al. (23) | COVID-19 STEMI | 144 | 63.1 ± 12.6 | 77.8 | 27.3 ± 4.5 | 34 | 64.8 | 46 | 31.7 | NA | 16.4 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 24,961 | 65.6 ± 13.4 | 72.2 | 27.8 ± 5.5 | 20.9 | 44.8 | 28.9 | 33.7 | NA | 13 | |

| Little et al. (24) | COVID-19 STEMI | 46 | 61.80 ± 7.95 | 80.4 | NA | 32.6 | 54 | 52.2 | 41.3 | NA | 10.9 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 302 | 64.18 ± 13.41 | 79.8 | NA | 23.5 | 50.7 | 33.1 | 41.7 | NA | 12.6 | |

| Marfella et al. (25) | COVID-19 STEMI | 46 | 56.13 ± 6.21 | 67.4 | 27.09 ± 1.81 | 17.4 | 39.1 | 15.2 | 6.5 | NA | NA |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 130 | 68.43 ± 6.46 | 66.2 | 29.55 ± 1.97 | 29.2 | 55.4 | 23.7 | 29.2 | NA | NA | |

| Pellegrini et al. (26) | COVID-19 STEMI | 24 | 69.63 ± 11.00 | 83.3 | 26.60 ± 3.36 | 41.7 | 70.8 | 62.5 | 29.2 | 45.8 | 29.2 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 26 | 64.65 ± 13.04 | 84.6 | 26.11 ± 3.43 | 15.4 | 53.9 | 65.4 | 38.5 | 28.6 | 19.2 | |

| Rodriguez-Leor et al. (27) | COVID-19 STEMI | 91 | 64.8 ± 11.8 | 84.4 | NA | 23.1 | 51.7 | 48.4 | 18.7 | 37.4 | NA |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 919 | 62.5 ± 13.1 | 78.4 | NA | 20.9 | 53.3 | 46.9 | 45.5 | 37.1 | NA | |

| Choudry et al. (28) | COVID-19 STEMI | 39 | 61.7 ± 11.0 | 84.6 | 26.7 (24.8–30.7) | 46.2 | 71.8 | 61.6 | 61.6 | NA | 15.4 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 76 | 61.7 ± 12.6 | 75 | 26.7 (24.8–30.7) | 46.2 | 42.1 | 36.8 | 46.1 | NA | 3.9 | |

| Blasco et al. (29) | COVID-19 STEMI | 5 | 62 ± 14 | 80 | 28.0 (27.3–30.1) | 0 | 80 | 0 | 40 | NA | NA |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 50 | 58 ± 12 | 88 | 27.6 (24.9–30.3) | 8 | 42 | 52 | 78 | NA | NA | |

| Güler et al. (30) | COVID-19 STEMI | 62 | 60.2 ± 9.5 | 66.1 | NA | 48.4 | 59.7 | 43.5 | 51.6 | NA | 9.7 |

| Non-COVID-19 STEMI | 64 | 63 ± 8 | 70.3 | NA | 54.7 | 57.8 | 34.3 | 56.3 | NA | 28.1 |

Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

Delays

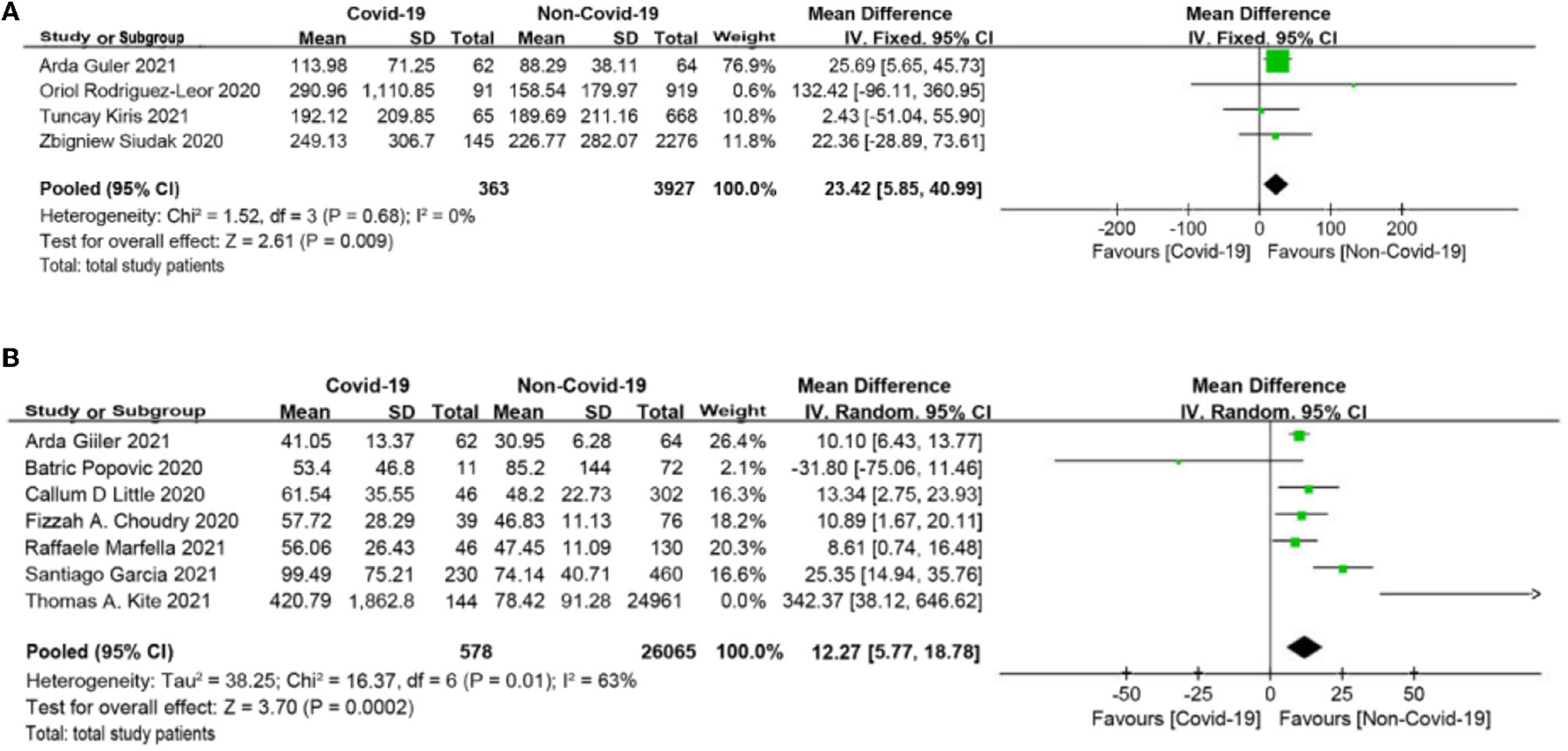

The symptom onset to first medical contact (SO-to-FMC) time among STEMI, which was reported in four studies (19, 20, 27, 30), was significantly different between the COVID-19 group and the non-COVID-19 group (MD = 23.42 min, 95% CI: 5.85 to 40.99 min, p = 0.009; Figure 2A). Furthermore, seven studies (18, 22–25, 28, 30) reported the time from door to balloon (D2B) and found that D2B was significantly longer in the COVID-19 group (MD = 12.27 min, 95% CI: 5.77 to 18.78 min, p = 0.0002; Figure 2B) than in the non-COVID-19 group. 3.3 Laboratory values.

Figure 2

(A) Symptom onset to first medical contact (SO-to-FMC) time forest plot (minutes). (B) Door to balloon (D2B) time forest plot (minutes).

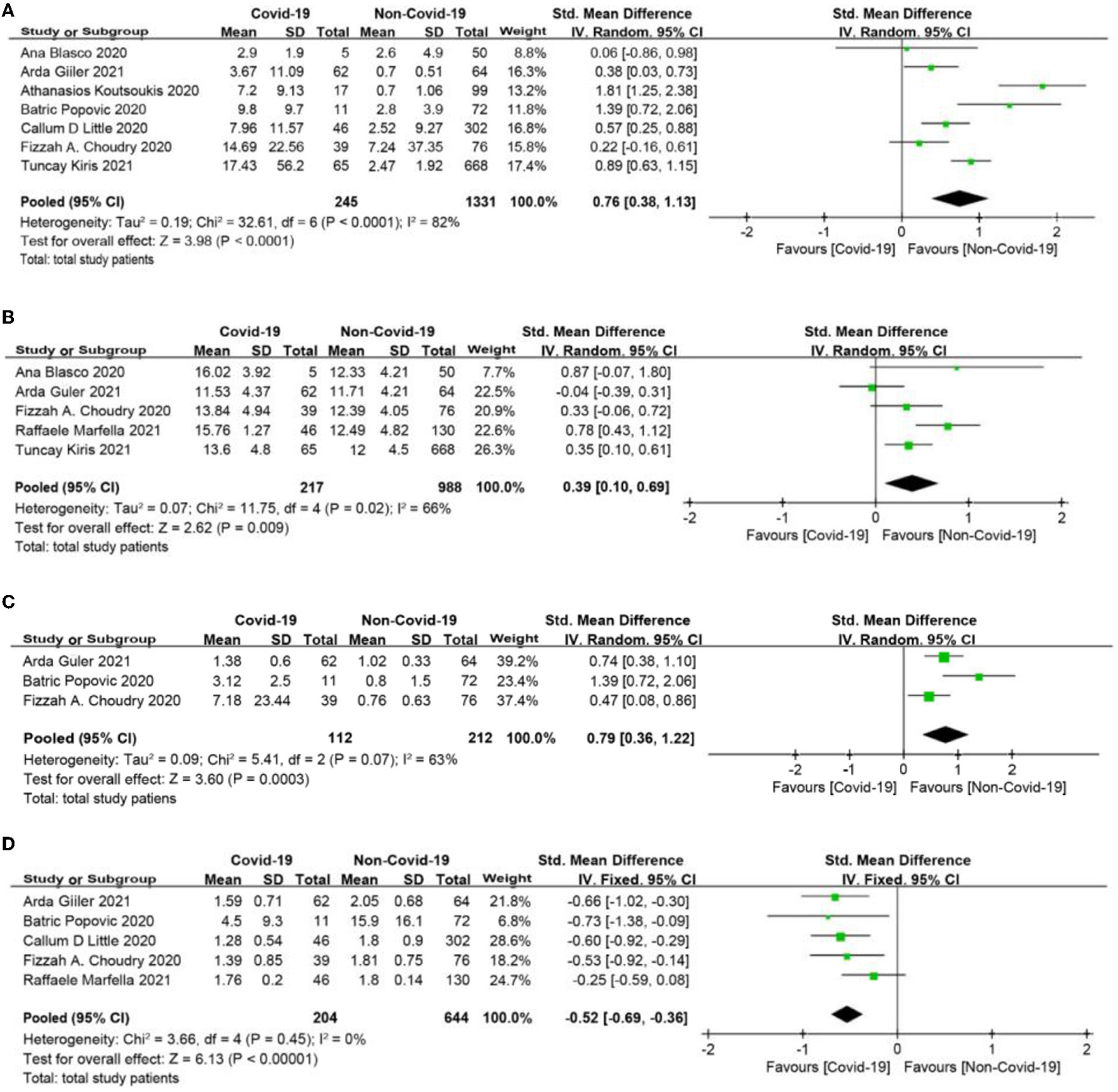

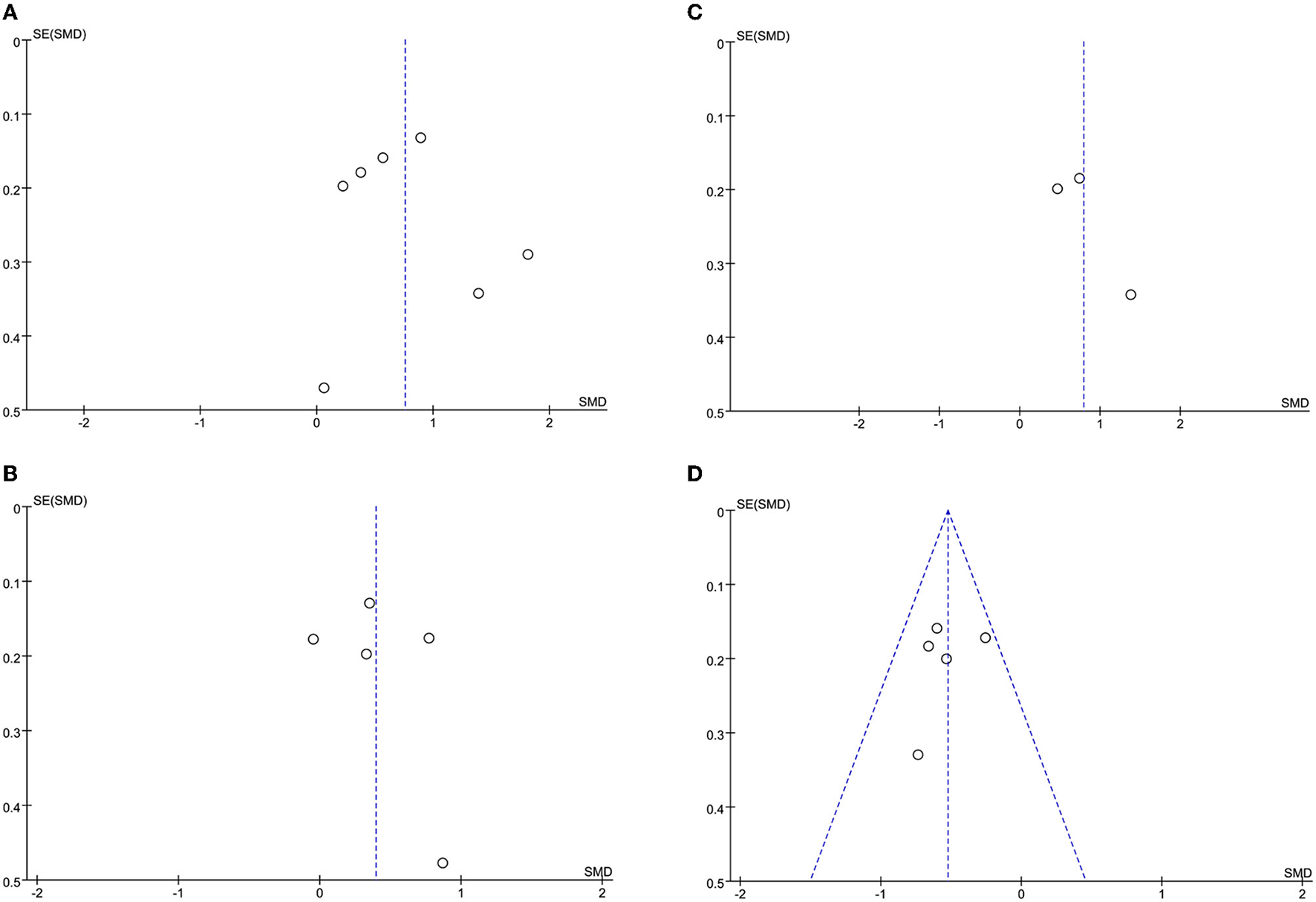

The meta-analysis showed that compared to the non-COVID-19 group, the COVID-19 group had significantly higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell count (WBC), and D-dimer (SMD = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.38 to 1.13, p < 0.0001; SMD = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.1 to 0.69, p = 0.009; SMD = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.36 to 1.22, p = 0.0003, respectively, Figures 3A–C), and had significantly lower level of lymphocyte count (SMD = −0.52, 95% CI: −0.69, −0.36, p < 0.0001, Figure 3D).

Figure 3

(A) C-reactive protein (CRP) forest plot (mg/dl). (B) White blood cell (WBC) forest plot (*109/L). (C) D-dimer forest plot (mg/L). (D) Lymphocyte count forest plot (*109/L).

Management and Procedural Characteristic

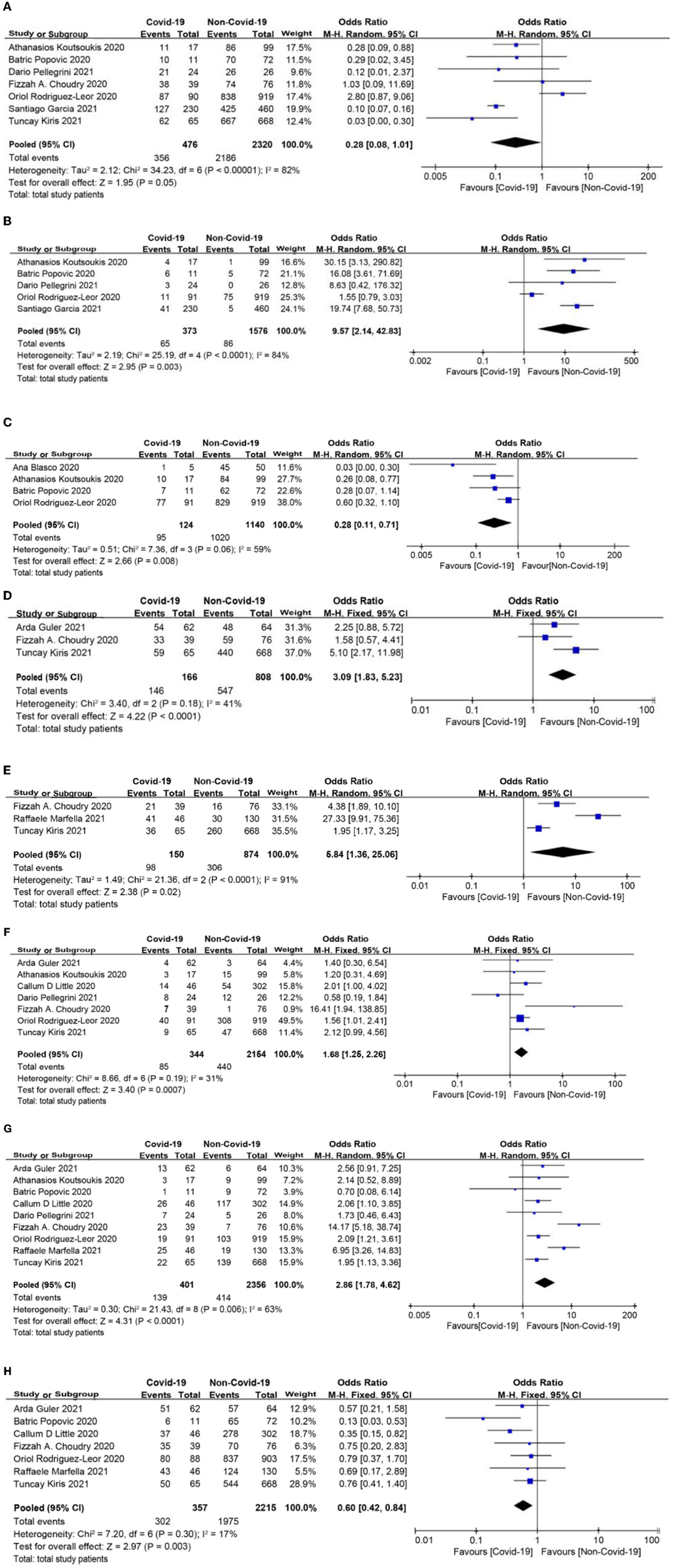

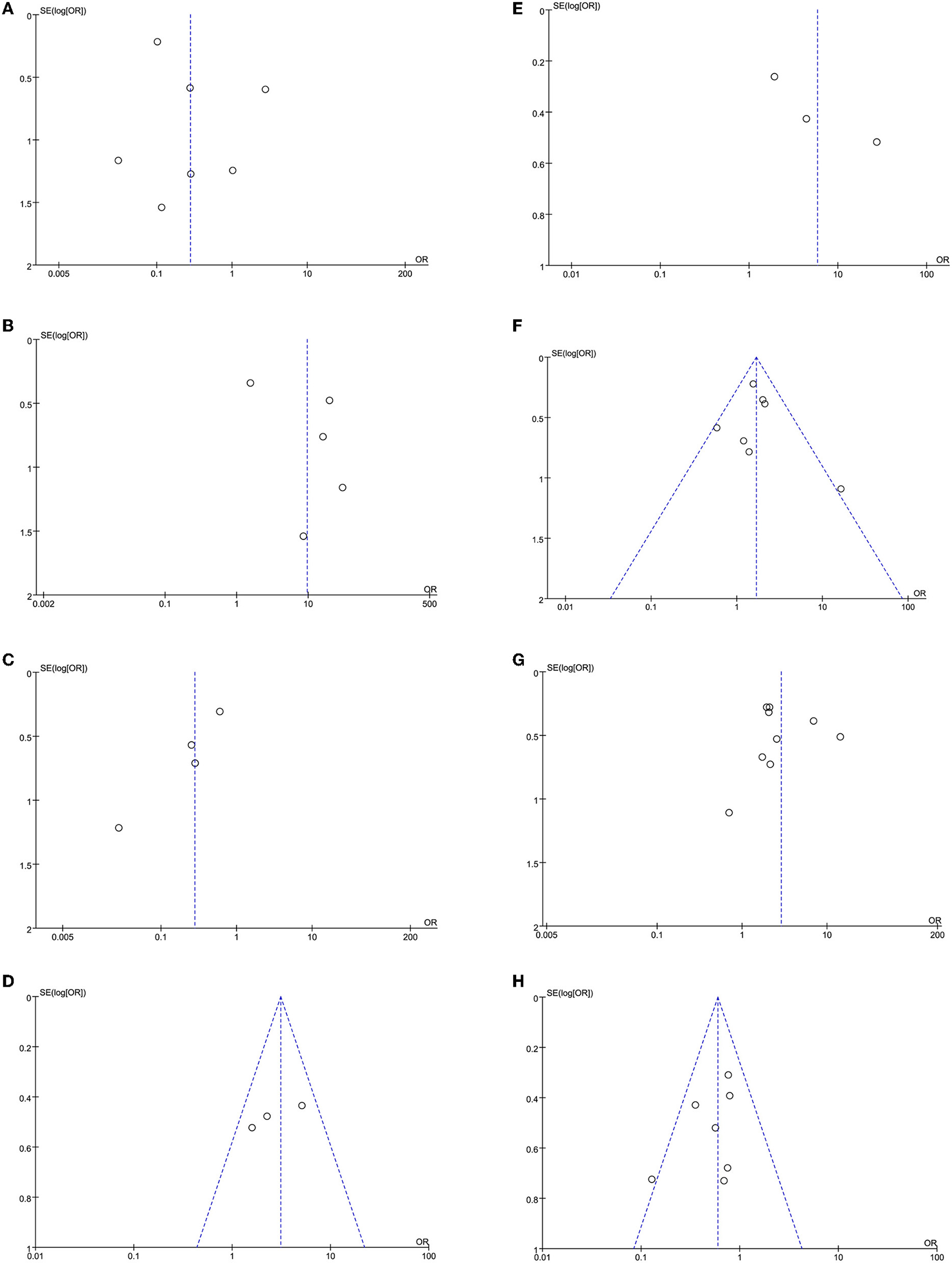

There was no significant difference in the rate of primary angioplasty between the two groups (OR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.08 to 1.01, p = 0.05; Figure 4A). Myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis (MINOCA) was more frequently observed, and the rate of stent implantation was lower in patients with COVID-19 infection (OR = 9.57, 95% CI: 2.14 to 42.83, p = 0.003; OR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.11 to 0.71, p = 0.008, respectively, Figures 4B,C). Baseline thrombus grade > 3 and modified thrombus grade > 3 were significantly higher in the COVID-19 group than in the non-COVID-19 group (OR = 3.09, 95% CI: 1.83 to 5.23, p < 0.0001; OR = 5.84, 95% CI: 1.36 to 25.06, p = 0.02, respectively; Figures 4D,E). Intracoronary thrombus was angiographically identified and scored in 0–5 grades as previously described (31). In patients initially presenting with grade 5, thrombus grade will be reclassified into one of the other categories after flow achievement (32). After reclassification and based on clinical outcomes, the thrombus burden can be divided into 2 categories: low thrombus grade for thrombus < grade 4, and high thrombus grade for thrombus grade 4 (32). Consistent with this, the COVID-19 group showed a higher use of thrombus aspiration and glycoprotein IIbIIIa (Gp2b3a) inhibitor (OR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.25 to 2.26, p = 0.0007; OR = 2.86, 95% CI: 1.78 to 4.62, p < 0.0001, respectively; Figures 4F,G). Moreover, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI)-3 flow post-procedure was less common in the COVID-19 group than in the non-COVID-19 group (OR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.42 to 0.84, p = 0.003, Figure 4H).

Figure 4

(A) Primary angioplasty forest plot. (B) Myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis (MINOCA) forest plot. (C) Stent implantation forest plot. (D) Baseline thrombus grade forest plot. (E) Modified thrombus grade forest plot. (F) Thrombus aspiration forest plot. (G) Glycoprotein IIbIIIa (Gp2b3a) inhibitor use forest plot. (H) Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI)-3 flow forest plot.

In-Hospital Outcomes

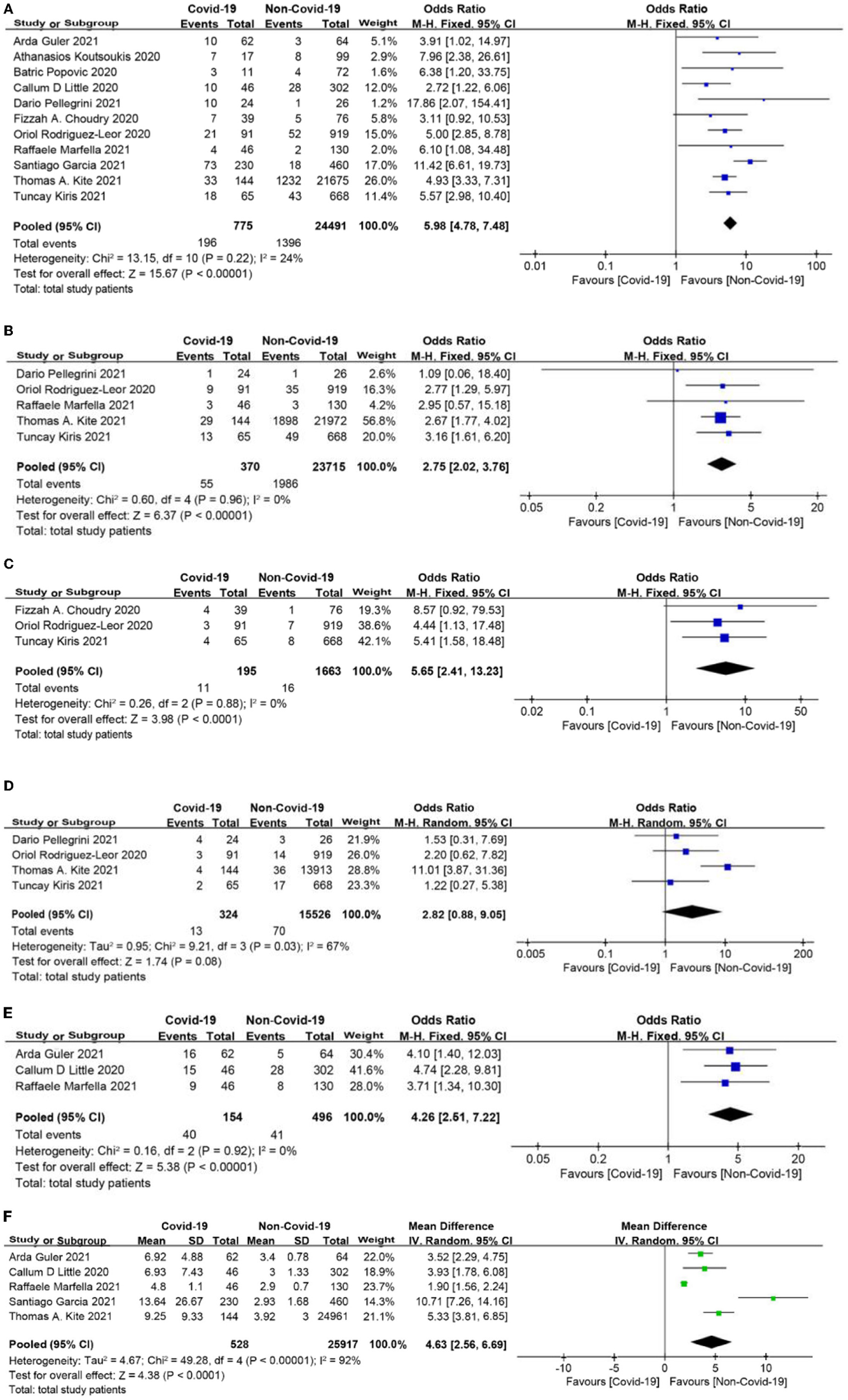

In-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 was significantly higher than that in patients without COVID-19 (OR = 5.98, 95% CI: 4.78 to 7.48, p < 0.0001, Figure 5A). The rates of cardiogenic shock as well as stent thrombosis were also higher in the COVID-19 group than in the non-COVID-19 group (OR = 2.75, 95% CI: 2.02 to 3.76, p < 0.0001; OR = 5.65, 95% CI: 2.41 to 13.23, p < 0.0001, respectively; Figures 5B,C). Although bleeding was more common in STEMI patients with COVID-19, there was no significant difference between the two groups (OR = 2.82, 95% CI: 0.88 to 9.05, p = 0.08, Figure 5D). In addition, patients with COVID-19 were more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and had a longer length of hospital stay (OR = 4.26, 95% CI: 2.51 to 7.22, p < 0.0001; MD = 4.63 days, 95% CI: 2.56 to 6.69 days, p < 0.0001, respectively, Figures 5E,F).

Figure 5

(A) In-hospital mortality forest plot. (B) Cardiogenic shock forest plot. (C) Stent thrombosis forest plot. (D) Bleeding forest plot. (E) Intensive care unit (ICU) admission rate forest plot. (F) Length of stay forest plot (days).

Grade Summary of Findings

The GRADE summary of findings tool was used to evaluate the quality of evidence, and the assessment for each outcome is presented in Table 3. In addition to in-hospital mortality, which moderates the quality of evidence, other outcomes had low or very low quality of evidence because all included studies were observational.

Table 3

| Effects of COVID-19 in STEMI patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patient or population: STEMI Patients Setting: Europe, Asian, North America Intervention: COVID-19 Comparison: Non-COVID-19 |

||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects*(95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Non-COVID-19 | Risk with COVID-19 | |||||

| Symptom-to-FMC time | The mean symptom-to-FMC time was 0 | MD 23.42 higher (5.85 higher to 40.99 higher) | – | 4,290 (4 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| D2B time | The mean D2B time was 0 | MD 12.27 higher (5.77 higher to 18.78 higher) | – | 26,643 (7 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| CRP | – | SMD 0.76 higher (0.38 higher to 1.13 higher) | – | 1,576 (7 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| WBC | – | SMD 0.39 higher (0.1 higher to 0.69 higher) | – | 1,205 (5 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| D–Dimer | – | SMD 0.79 higher (0.36 higher to 1.22 higher) | – | 324 (3 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| Lymphocyte count | – | SMD 0.52 lower (0.69 lower to 0.36 lower) | – | 848 (5 observational studies) | ⊕⊕○○ Low | NA |

| Primary angioplasty | 942 per 1,000 | 820 per 1,000 (566 to 943) | OR 0.28 (0.08 to 1.01) | 2,796 (7 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| MINOCA | 55 per 1,000 | 356 per 1,000 (110 to 712) | OR 9.57 (2.14 to 42.83) | 1,949 (5 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| Stent implantation | 895 per 1,000 | 704 per 1,000 (483 to 858) | OR 0.28 (0.11 to 0.71) | 1,264 (4 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| Baseline thrombus grade > 3 | 677 per 1,000 | 866 per 1,000 (793 to 916) | OR 3.09 (1.83 to 5.23) | 974 (3 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| Modified thrombus grade > 3 | 350 per 1,000 | 759 per 1,000 (423 to 931) | OR 5.84 (1.36 to 25.06) | 1,024 (3 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| Thrombus aspiration | 204 per 1,000 | 301 per 1,000 (243 to 367) | OR 1.68 (1.25 to 2.26) | 2,498 (7 observational studies) | ⊕⊕○○ Low | NA |

| Gp2b3a inhibitor | 176 per 1,000 | 379 per 1,000 (275 to 496) | OR 2.86 (1.78 to 4.62) | 2,757 (9 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| TIMI-3 Flow | 892 per 1,000 | 832 per 1,000 (776 to 874) | OR 0.60 (0.42 to 0.84) | 2,572 (7 observational studies) | ⊕⊕○○ Low | NA |

| In- hospital mortality | 57 per 1,000 | 265 per 1,000 (224 to 311) | OR 5.98 (4.78 to 7.48) | 25,266 (11 observational studies) | ⊕⊕⊕○ Moderate | NA |

| Cardiogenic shock | 84 per 1,000 | 201 per 1,000 (156 to 256) | OR 2.75 (2.02 to 3.76) | 24,085 (5 observational studies) | ⊕⊕○○ Low | NA |

| Stent thrombosis | 10 per 1,000 | 52 per 1,000 (23 to 114) | OR 5.65 (2.41 to 13.23) | 1,858 (3 observational studies) | ⊕⊕○○ Low | NA |

| Bleeding | 5 per 1,000 | 13 per 1,000 (4 to 39) | OR 2.82 (0.88 to 9.05) | 15,850 (4 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| ICU admission | 83 per 1,000 | 277 per 1,000 (184 to 394) | OR 4.26 (2.51 to 7.22) | 650 (3 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

| Length of stay | The mean length of stay was 0 | MD 4.63 higher (2.56 higher to 6.69 higher) | - | 26,445 (5 observational studies) | ⊕○○○ Very low | NA |

GRADE summary of findings.

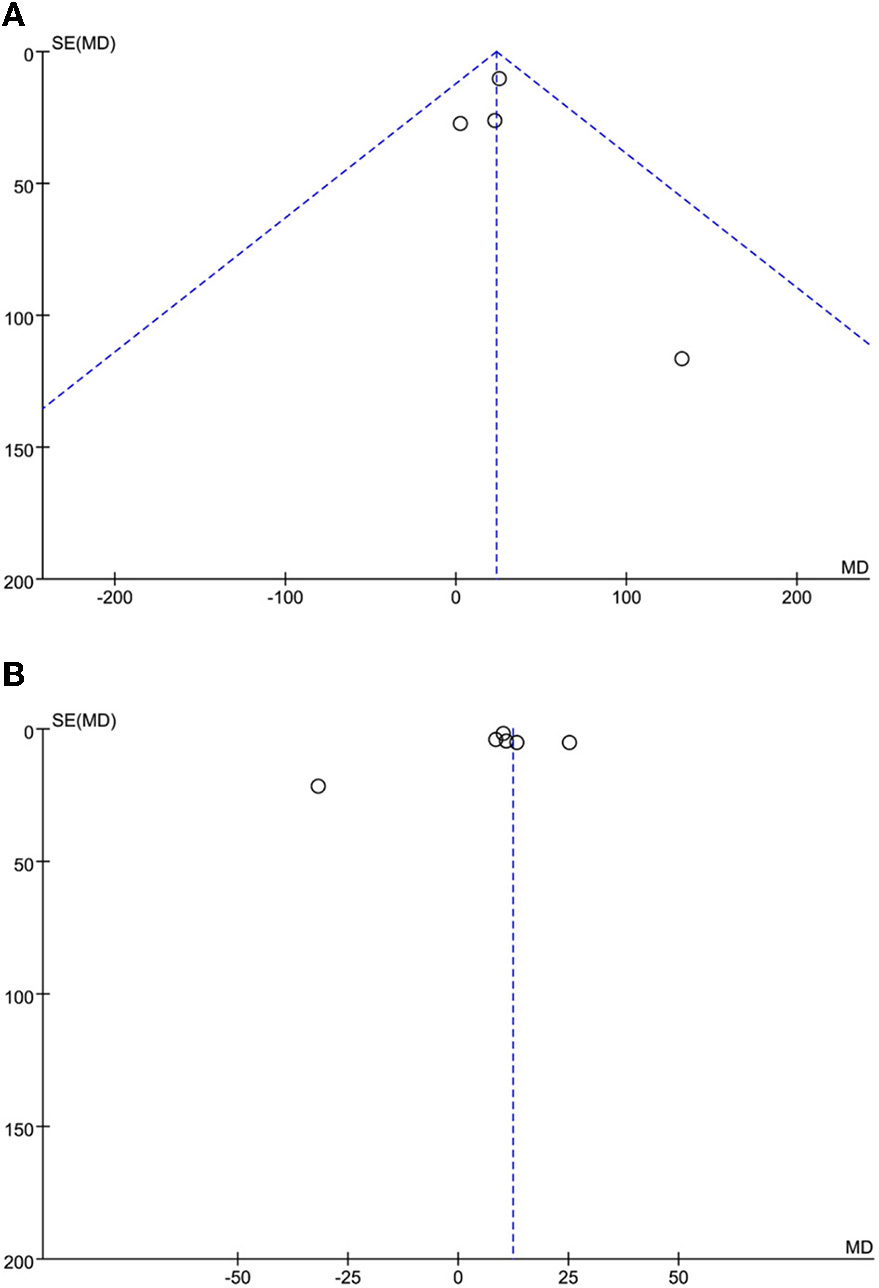

Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

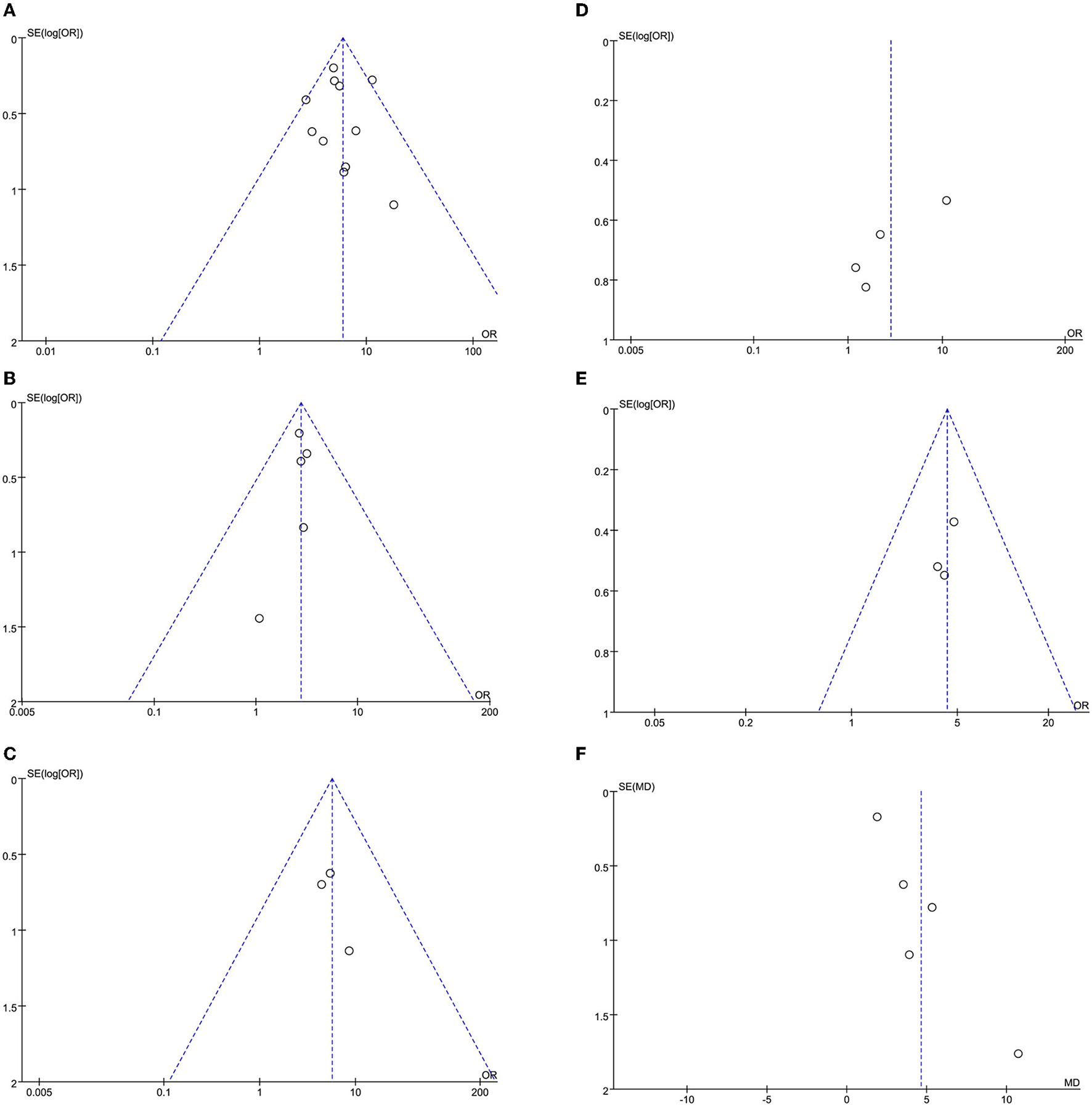

The leave-one-out approach was applied for sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of a single study on outcomes with a high degree of heterogeneity. As shown in Table 4, the overall results were relatively robust and not influenced by a single study, except for primary angioplasty, stent implantation, and modified thrombus grade. An asymmetrical plot was observed in some funnel plots, suggesting that publication bias may exist (Figures 6A–9F).

Table 4

| Study name | Statistics with study excluded | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio or SMD | 95% CI | P-value | |

| D2B time | |||

| Güler et al. (30) | 12.66 | 2.96 to 22.35 | 0.01 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 13.06 | 7.13 to 18.99 | <0.0001 |

| Little et al. (24) | 12.01 | 4.16 to 19.86 | 0.003 |

| Choudry et al. (28) | 12.52 | 4.35 to 20.68 | 0.003 |

| Marfella et al. (25) | 13.1 | 4.66 to 21.54 | 0.002 |

| Garcia et al. (22) | 9.92 | 4.47 to 15.35 | 0.0004 |

| Kite et al. (23) | 12.15 | 6.47 to 17.82 | <0.0001 |

| CRP | |||

| Blasco et al. (29) | 0.82 | 0.43 to 1.21 | <0.0001 |

| Güler et al. (30) | 0.83 | 0.40 to 1.26 | 0.0002 |

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | 0.59 | 0.29 to 0.90 | 0.0001 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 0.67 | 0.28 to 1.06 | 0.0007 |

| Little et al. (24) | 0.8 | 0.33 to 1.26 | 0.0007 |

| Choudry et al. (28) | 0.86 | 0.45 to 1.26 | <0.0001 |

| Kiris et al. (20) | 0.73 | 0.27 to 1.20 | 0.002 |

| WBC | |||

| Blasco et al. (29) | 0.35 | 0.04 to 0.67 | 0.03 |

| Güler et al. (30) | 0.5 | 0.25 to 0.76 | <0.0001 |

| Choudry et al. (28) | 0.42 | 0.04 to 0.81 | 0.03 |

| Marfella et al. (25) | 0.26 | 0.08 to 0.44 | 0.004 |

| Kiris et al. (20) | 0.038 | 0.18 to 0.59 | 0.0002 |

| D-Dimer | |||

| Güler et al. (30) | 0.89 | 0.01 to 1.78 | 0.05 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 0.62 | 0.35 to 0.88 | <0.0001 |

| Choudry et al. (28) | 1.00 | 0.38 to 1.62 | 0.002 |

| Primary Angioplasty | |||

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | 0.27 | 0.05 to 1.43 | 0.12 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 0.28 | 0.07 to 1.15 | 0.08 |

| Pellegrini et al. (26) | 0.31 | 0.01 to 1.24 | 0.10 |

| Choudry et al. (28) | 0.23 | 0.06 to 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Rodriguez-Leor et al. (27) | 0.12 | 0.08 to 0.17 | <0.0001 |

| Garcia et al. (22) | 0.36 | 0.09 to 1.49 | 0.16 |

| Kiris et al. (20) | 0.21 | 0.16 to 0.29 | <0.0001 |

| MINOCA | |||

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | 7.63 | 1.44 to 40.43 | 0.02 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 8.49 | 1.37 to 52.74 | 0.02 |

| Pellegrini et al. (26) | 9.81 | 1.84 to 52.38 | 0.01 |

| Rodriguez-Leor (27) | 18.62 | 8.73 to 39.72 | <0.0001 |

| Garcia et al. (22) | 7.56 | 1.38 to 41.37 | 0.02 |

| Stent Implantation | |||

| Blasco et al. (29) | 0.46 | 0.28 to 0.75 | 0.002 |

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | 0.25 | 0.06 to 1.01 | 0.05 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 0.25 | 0.07 to 0.90 | 0.03 |

| Rodriguez-Leor et al. (27) | 0.20 | 0.09 to 0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Modified Thrombus Grade | |||

| Choudry et al. (28) | 7.03 | 0.52 to 96.03 | 0.14 |

| Marfella et al. (25) | 2.72 | 1.25 to 5.94 | 0.01 |

| Kiris et al. (20) | 10.69 | 1.75 to 65.11 | 0.01 |

| Gp2b3a inhibitor use | |||

| Güler et al. (30) | 2.90 | 1.70 to 4.93 | <0.0001 |

| Koutsoukis et al. (21) | 2.93 | 1.75 to 4.90 | <0.0001 |

| Popovic et al. (18) | 3.03 | 1.87 to 4.93 | <0.0001 |

| Little et al. (24) | 3.02 | 1.72 to 5.30 | 0.0001 |

| Pellegrini et al. (26) | 2.99 | 1.79 to 5.01 | <0.0001 |

| Choudry et al. (28) | 2.37 | 1.81 to 3.11 | <0.0001 |

| Rodriguez-Leor et al. (27) | 2.93 | 2.19 to 3.92 | <0.0001 |

| Marfella et al. (25) | 2.41 | 1.83 to 3.17 | <0.0001 |

| Kiris et al. (20) | 3.01 | 2.25 to 4.03 | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding | |||

| Pellegrini et al. (26) | 3.30 | 0.77 to 14.07 | 0.11 |

| Rodriguez-Leor et al. (27) | 2.95 | 0.55 to 15.73 | 0.21 |

| Kite et al. (23) | 1.62 | 0.71 to 3.73 | 0.25 |

| Kiris et al. (20) | 3.62 | 0.92 to 14.23 | 0.07 |

| Length of Stay | |||

| Güler et al. (30) | 5.11 | 2.17 to 8.06 | 0.0007 |

| Little et al. (24) | 4.84 | 2.41 to 7.27 | <0.0001 |

| Marfella et al. (25) | 5.42 | 3.24 to 7.26 | <0.0001 |

| Garcia et al. (22) | 3.56 | 1.85 to 5.27 | <0.0001 |

| Kite et al. (23) | 4.41 | 2.14 to 6.69 | 0.0001 |

Leave-one-out analysis.

Figure 6

(A) SO-to-FMC time funnel plot. (B) D2B time funnel plot.

Figure 7

(A) CRP funnel plot. (B) WBC funnel plot. (C) D-dimer funnel plot. (D) Lymphocyte count funnel plot.

Figure 8

(A) Primary angioplasty funnel plot. (B) MINOCA funnel plot. (C) Stent implantation funnel plot. (D) Baseline thrombus grade funnel plot. (E) Modified thrombus grade funnel plot. (F) Thrombus aspiration funnel plot. (G) Gp2b3a inhibitor use funnel plot. (H) TIMI-3 flow funnel plot.

Figure 9

(A) In-hospital mortality funnel plot. (B) Cardiogenic shock funnel plot. (C) Stent thrombosis funnel plot. (D) Bleeding funnel plot. (E) ICU admission rate funnel plot. (F) Length of stay funnel plot.

Discussion

Clinical Implications

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the characteristics, management, and clinical outcomes of patients with STEMI presenting with COVID-19 infection and that of those patients without COVID-19 infection. Compared to the non-COVID-19 group, the COVID-19 group had significant delays in SO-to-FMC and D2B times. Among the two groups, laboratory values, such as CRP, WBC, and D-dimer, were elevated in the COVID-19 group, while lymphocyte count was found to be lower compared to the non-COVID-19 group. In addition, STEMI concomitant with COVID-19 infection was characterized by a higher rate of MINOCA, lower rate of stent implantation, and higher thrombus grade, and associated higher use of thrombus aspiration and Gp2b3a inhibitors. Furthermore, we found that the COVID-19 group had an increased rate of in-hospital mortality, cardiogenic shock, stent thrombosis, ICU admission, longer length of hospital stays, and decreased TIMI flow post-procedure.

The COVID-19 pandemic started in late 2019 and has caused severe delays in the treatment of patients with STEMI compared to the pre-COVID-19 era, and this is mostly explained by the limited access to emergency medical services (EMS) and the lack of effective organization of healthcare systems (33, 34). Several studies reported that the time from SO-to-FMC and D2B was longer in STEMI patients with COVID-19 than in those without COVID-19, which may be related to the following factors: a higher rate of respiratory symptoms without chest pain as a clinical manifestation in COVID-19 patients may result in an unclear diagnosis of heart attack and lead to a delay in seeking medical service (35), Furthermore, interventional procedures may be more complex in COVID-19 patients than in non-COVID-19 patients (24).

The reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic remains controversial. The Chinese Cardiac Society and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology recommend thrombolysis as the preferred reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI (36, 37). In contrast, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) still suggested the use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) as the main treatment for all patients with STEMI during the COVID-19 crisis (1, 2). Rashid et al. reported that STEMI patients with COVID-19 were less likely to receive PPCI than STEMI patients without COVID-19 (38). However, in this study, we did not find a significant difference in the rate of primary angioplasty between both groups. Moreover, we found that the COVID-19 group had a lower rate of stent implantation, which may be associated with a higher rate of MINOCA.

Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 may lead to a prothrombotic state and that a high thrombus burden is more common in STEMI patients with COVID-19 (39–42). SARS-CoV-2 causes a systemic inflammatory response, resulting in endothelial and hemostatic activation, which involves the activation of platelets and the coagulation cascade (43). In addition, our study found that the time from SO-to-FMC and D2B was longer in STEMI patients with COVID-19 than in those without COVID-19. The studies of Duman et al. (44) and Ge et al. (45) reported that the delay in SO-to-FMC and D2B would prolong the time for opening infarct-related vessels which may account for a higher thrombus burden. Therefore, in the COVID era, it is of great significance that novel technologies should be developed so as to achieve more efficient thrombus aspiration in patients with very high intra-coronary thrombus burden such as patients with STEMI and coexistent COVID-19 infection (46). Furthermore, strategies to reduce reperfusion delay times such as educating the public about the recognition and diversity of coronary symptoms and optimizing interventional procedures are essential. In keeping with the high thrombus burden, the COVID-19 group had elevated CRP, WBC, and D-dimer levels and a lower lymphocyte count compared to the non-COVID-19 group. High thrombus grade, reduced TIMI flow, high rate of MINOCA, and stent thrombosis may be the result of the intense inflammatory and heightened thrombus burden observed in COVID-19 patients (18, 27, 28, 34). Consistently, the data presented here demonstrated a more aggressive use of thrombus aspiration and a Gp2b3a inhibitor in STEMI patients with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection. The use of a Gp2b3a inhibitor may also increase the risk of bleeding (47), but this study showed no significant difference between the two groups in terms of bleeding.

Hospital-mortality was dramatically higher in STEMI patients who presented with COVID-19 than in those without COVID-19. Longer ischemia time, higher thrombus burden, and increased rate of adverse cardiovascular events, including cardiogenic shock, may also be contributory (48, 49). Current studies (50, 51) have reported that STEMI patients with concomitant COVID-19 have higher ICU admission rates and longer lengths of stay, and the results of this meta-analysis support this finding. An increased ICU admission rate and length of stay may have a significant impact on hospital resources. Taken together, COVID-19 status may have great implications on the characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients with STEMI.

Heterogeneity of Meta-Analysis

In a meta-analysis, heterogeneity may exist while the sample estimates for the population risk were of different magnitudes (52). The I2 statistic means the percentage of total variation across effect size estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. In our study, there are significant and high degrees of heterogeneity for some outcomes. The existing heterogeneity can partly result from different sample sizes, study designs, study times, study scope (nation and region), diagnostic methods, the severity of the disease. We aggregate studies that are different methodologies, but the heterogeneity in the results is still inevitable.

Methodological Considerations

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that summarizes the comparison of clinical information on STEMI patients presenting with vs. those presenting without COVID-19 infection. We included multiple studies that were conducted in Asia, Europe, and North America, so that our findings can provide a broad overview of COVID-19 infection in patients with STEMI. However, our study has several limitations. First, the delay time, laboratory values, and length of stay were reported in terms of median values and IQR in many studies, which have been adjusted to means and SDs using the Box-Cox method. Nevertheless, using this method to calculate SDs may entail inaccuracy and make the SDs greater than the mean in some cases, which is an inherent feature of the method (17). Second, the disparity in study size may affect the weighting of the studies and the pooled effect size, which is innate to meta-analyses (53, 54). Third, a high degree of heterogeneity was observed in some outcomes. Due to inadequate information for the included studies, it is difficult to conduct a subgroup analysis to explain the heterogeneity. We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the reliability of our findings and used the random-effects model when I2 statistics were more than 50%. Fourth, we were unable to compare the rate of thrombosis and elective PCI, and the revascularization rate of patients undergoing primary angioplasty between the two groups due to a lack of sufficient data. Future studies are needed to further investigate these outcomes. Finally, our data were limited to in-hospital outcomes. Long-term follow-up is required to explore the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and poor outcomes in patients with STEMI.

Conclusion

In patients with STEMI, COVID-19 has had a deep impact on their therapeutic management and clinical outcomes. A longer time from SO-to-FMC and D2B was observed in STEMI patients with COVID-19 in our study. Moreover, patients with STEMI who also had COVID-19 had more severe thrombotic events adverse outcomes. Further studies are required to explore the mechanism of coronary thrombus burden and the optimal treatment for patients with STEMI and COVID-19.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

YW, LK, C-WC, SX, and T-HT: conception. YW, LK, C-WC, JX, PY, SX, and T-HT: methodology. YW, LK, JX, PY, and T-HT: analysis. YW, LK, JX, and PY: interpretation and writing. C-WC, SX, and T-HT: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Mahmud E Dauerman HL Welt FGP Messenger JC Rao SV Grines C et al . Management of Acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic: a position statement from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions (SCAI), the American college of cardiology (acc), and the American college of emergency physicians (ACEP). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1375–84. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.039

2.

Reed GW Rossi JE Cannon CP . Acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. (2017) 389:197–210. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30677-8

3.

Gulati A Pomeranz C Qamar Z Thomas S Frisch D George G et al . A comprehensive review of manifestations of novel coronaviruses in the context of deadly COVID-19 global pandemic. Am J Med Sci. (2020) 360:5–34. 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.05.006

4.

Wang D Hu B Hu C Zhu F Liu X Zhang J et al . Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019. Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. (2020) 323:1061–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585

5.

Gupta A Madhavan MV Sehgal K Nair N Mahajan S Sehrawat TS et al . Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1017–32. 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3

6.

Behzad S Aghaghazvini L Radmard AR Gholamrezanezhad A . Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19: Radiologic and clinical overview. Clin Imaging. (2020) 66:35–41. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.05.013

7.

Choudhury T West NE El-Omar M . ST elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Med (Lond). (2016) 16:277–82. 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-3-277

8.

Gale CP Allan V Cattle BA Hall AS West RM Timmis A et al . Trends in hospital treatments, including revascularisation, following acute myocardial infarction, 2003-2010: a multilevel and relative survival analysis for the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). Heart. (2014) 100:582–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304517

9.

Townsend N Wilson L Bhatnagar P Wickramasinghe K Rayner M Nichols M . Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:3232–45. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334

10.

Pedersen F Butrymovich V Kelbæk H Wachtell K Helqvist S Kastrup J et al . Short- and long-term cause of death in patients treated with primary PCI for STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64:2101–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.037

11.

Baumhardt M Dreyhaupt J Winsauer C Stuhler L Thiessen K Stephan T et al . The effect of the lockdown on patients with myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2021) 118:447–53. 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0253

12.

Xiang D Xiang X Zhang W Yi S Zhang J Gu X et al . Management and outcomes of patients with STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1318–24. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.039

13.

Bikdeli B Madhavan MV Jimenez D Chuich T Dreyfus I Driggin E et al . COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75:2950–73. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031

14.

Pérez-Bermejo JA Kang S Rockwood SJ Simoneau CR Joy DA Ramadoss GN et al . SARS-CoV-2 infection of human iPSC-derived cardiac cells predicts novel cytopathic features in hearts of COVID-19 patients. bioRxiv. (2020) 10.1101/2020.08.25.265561

15.

Hayek SS Brenner SK Azam TU Shadid HR Anderson E Berlin H et al . In-hospital cardiac arrest in critically ill patients with covid-19: multicenter cohort study. Bmj. (2020) 371:m3513. 10.1136/bmj.m3513

16.

Bonow RO Fonarow GC O'Gara PT Yancy CW . Association of coronavirus disease (2019). (COVID-19) with myocardial injury and mortality. JAMA Cardiol. (2020) 5:751–3. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1105

17.

McGrath S Zhao XF Steele R Thombs BD Benedetti A Levis B et al . Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from commonly reported quantiles in meta-analysis. Statistic Methods Med Res. (2020) 29:2520–37. 10.1177/0962280219889080

18.

Popovic B Varlot J Metzdorf PA Jeulin H Goehringer F Camenzind E . Changes in characteristics and management among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction due to COVID-19 infection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 97:E319–e26. 10.1002/ccd.29114

19.

Siudak Z Grygier M Wojakowski W Malinowski KP Witkowski A Gasior M et al . Clinical and procedural characteristics of COVID-19 patients treated with percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 96:E568–e75. 10.1002/ccd.29134

20.

Kiris T Avci E Ekin T Akgün DE Tiryaki M Yidirim A et al . Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in Turkey: results from TURSER study (TURKISH St-segment elevation myocardial infarction registry). J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2021) 2021:1–14. 10.1007/s11239-021-02487-3

21.

Koutsoukis A Delmas C Roubille F Bonello L Schurtz G Manzo-Silberman S et al . Acute coronary syndrome in the era of sars-cov-2 infection: a registry of the french group of acute cardiac care. CJC Open. (2021) 3:311–7. 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.11.003

22.

Garcia S Dehghani P Grines C Davidson L Nayak KR Saw J et al . Initial findings from the North American COVID-19 myocardial infarction registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:1994–2003. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.055

23.

Kite TA Ludman PF Gale CP Wu J Caixeta A Mansourati J et al . International prospective registry of acute coronary syndromes in patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:2466–76. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.03.309

24.

Little CD Kotecha T Candilio L Jabbour RJ Collins GB Ahmed A et al . COVID-19 pandemic and STEMI: pathway activation and outcomes from the pan-London heart attack group. Open Heart. (2020) 7:2. 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001432

25.

Marfella R Paolisso P Sardu C Palomba L D'Onofrio N Cesaro A et al . SARS-COV-2 colonizes coronary thrombus and impairs heart microcirculation bed in asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive subjects with acute myocardial infarction. Crit Care. (2021) 25:217. 10.1186/s13054-021-03643-0

26.

Pellegrini D Fiocca L Pescetelli I Canova P Vassileva A Faggi L et al . Effect of respiratory impairment on the outcomes of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Circ J. (2021) 85:1701–7. 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-1166

27.

Rodriguez-Leor O Cid Alvarez AB Pérez de Prado A Rossello X Ojeda S Serrador A et al . In-hospital outcomes of COVID-19 ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. EuroIntervention. (2021) 16:1426–33. 10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00935

28.

Choudry FA Hamshere SM Rathod KS Akhtar MM Archbold RA Guttmann OP et al . High thrombus burden in patients with COVID-19 presenting with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:1168–76. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.022

29.

Blasco A Coronado MJ Hernández-Terciado F Martín P Royuela A Ramil E et al . Assessment of neutrophil extracellular traps in coronary thrombus of a case series of patients with COVID-19 and myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. (2020) 6:1–6. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7308

30.

Güler A Gürbak I Panç C Güner A Ertürk M . Frequency and predictors of no-reflow phenomenon in patients with COVID-19 presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol. (2021) 2021:1–9. 10.1080/00015385.2021.1931638

31.

Gibson CM de Lemos JA Murphy SA Marble SJ McCabe CH Cannon CP et al . Combination therapy with abciximab reduces angiographically evident thrombus in acute myocardial infarction: a TIMI 14 substudy. Circulation. (2001) 103:2550–4. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.21.2550

32.

Sianos G Papafakli MI Daemen J Vaina S van Mieghem CA van Domburg RT et al . Angiographic stent thrombosis after routine use of drug-eluting stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the importance of thrombus burden. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2007) 50:573–83. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.059

33.

Ferlini M Andreassi A Carugo S Cuccia C Bianchini B Castiglioni B et al . Centralization of the ST elevation myocardial infarction care network in the Lombardy region during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 312:24–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.062

34.

Tam CF Cheung KS Lam S Wong A Yung A Sze M et al . Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak on st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2020) 13:e006631. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631

35.

Carugo S Ferlini M Castini D Andreassi A Guagliumi G Metra M et al . Management of acute coronary syndromes during the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy: The “macro-hub” experience. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. (2020) 31:100662. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100662

36.

Han Y Zeng H Jiang H Yang Y Yuan Z Cheng X et al . CSC Expert consensus on principles of clinical management of patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases during the COVID-19 epidemic. Circulation. (2020) 141:e810–e6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047011

37.

Wood DA Sathananthan J Gin K Mansour S Ly HQ Quraishi AU et al . Precautions and procedures for coronary and structural cardiac interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from canadian association of interventional cardiology. Can J Cardiol. (2020) 36:780–3. 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.03.027

38.

Rashid M Wu J Timmis A Curzen N Clarke S Zaman A et al . Outcomes of COVID-19-positive acute coronary syndrome patients: a multisource electronic healthcare records study from England. J Intern Med. (2021) 290:88–100. 10.1111/joim.13246

39.

Fan BE Chong VCL Chan SSW Lim GH Lim KGE Tan GB et al . Hematologic parameters in patients with COVID-19 infection. Am J Hematol. (2020) 95:E131–e4. 10.1002/ajh.25774

40.

Klok FA Kruip M van der Meer NJM Arbous MS Gommers D Kant KM et al . Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. (2020) 191:145–7. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

41.

Beyrouti R Adams ME Benjamin L Cohen H Farmer SF Goh YY et al . Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2020) 91:889–91. 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586

42.

Ruan Q Yang K Wang W Jiang L Song J . Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:846–8. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x

43.

Masi P Hékimian G Lejeune M Chommeloux J Desnos C Pineton De Chambrun M et al . Systemic inflammatory response syndrome is a major contributor to COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: insights from a prospective, single-center cohort study. Circulation. (2020) 142:611–4. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048925

44.

Duman H Çetin M Durakoglugil ME Degirmenci H Hamur H Bostan M et al . Relation of angiographic thrombus burden with severity of coronary artery disease in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Med Sci Monit. (2015) 21:3540–6. 10.12659/MSM.895157

45.

Ge J Li J Dong B Ning X Hou B . Determinants of angiographic thrombus burden and impact of thrombus aspiration on outcome in young patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2019) 93:E269–e76. 10.1002/ccd.27944

46.

Karagiannidis E Papazoglou AS Sofidis G Chatzinikolaou E Keklikoglou K Panteris E et al . Micro-CT-Based quantification of extracted thrombus burden characteristics and association with angiographic outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the QUEST-STEMI study. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:646064. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.646064

47.

Elian D Guetta V . Glycoprotein 2b3a inhibitors for acute coronary syndromes: what the trials tell us. Harefuah. (2003) 142:350–498.

48.

Scholz KH Maier SKG Maier LS Lengenfelder B Jacobshagen C Jung J et al . Impact of treatment delay on mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients presenting with and without haemodynamic instability: results from the German prospective, multicentre FITT-STEMI trial. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39:1065–74. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy004

49.

Singh M Berger PB Ting HH Rihal CS Wilson SH Lennon RJ et al . Influence of coronary thrombus on outcome of percutaneous coronary angioplasty in the current era (the Mayo Clinic experience). Am J Cardiol. (2001) 88:1091–6. 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02040-9

50.

Solano-López J Zamorano JL Pardo Sanz A Amat-Santos I Sarnago F Gutiérrez Ibañes E et al . Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 outbreak. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). (2020) 73:985–93. 10.1016/j.recesp.2020.07.023

51.

Matsushita K Hess S Marchandot B Sato C Truong DP Kim NT et al . Clinical features of patients with acute coronary syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2021) 52:95–104. 10.1007/s11239-020-02340-z

52.

Sedgwick P . Meta-analyses: what is heterogeneity?Bmj-Br Med J. (2015) 15:350. 10.1136/bmj.h1435

53.

Rattka M Dreyhaupt J Winsauer C Stuhler L Baumhardt M Thiessen K et al . Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality of patients with STEMI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. (2020) 20:360. 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318360

54.

Kamarullah W Sabrina AP Rocky MA Gozali DR . Investigating the implications of COVID-19 outbreak on systems of care and outcomes of STEMI patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian Heart J. (2021) 73:404–12. 10.1016/j.ihj.2021.06.009

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, mortality, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI

Citation

Wang Y, Kang L, Chien C-W, Xu J, You P, Xing S and Tung T-H (2022) Comparison of the Characteristics, Management, and Outcomes of STEMI Patients Presenting With vs. Those of Patients Presenting Without COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:831143. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.831143

Received

09 December 2021

Accepted

07 February 2022

Published

14 March 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Nicola Mumoli, ASST Ovest Milanese, Italy

Reviewed by

Antonia Anna Lukito, University of Pelita Harapan, Indonesia; Wenyang Jiang, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, China; Efstratios Karagiannidis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece; Vinod Krishnappa, University of North Carolina Health Southeastern, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Wang, Kang, Chien, Xu, You, Xing and Tung.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao-Hsin Tung ch2876@gmail.comSizhong Xing xsz7220@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

This article was submitted to Cardiovascular Epidemiology and Prevention, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.