Abstract

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been a global pandemic since early 2020. Understanding the relationship between various systemic disease and COVID-19 through disease ontology (DO) analysis, an approach based on disease similarity studies, has found that COVID-19 is most strongly associated with atherosclerosis. The study provides new insights for the common pathogenesis of COVID-19 and atherosclerosis by looking for common transcriptional features. Two datasets (GSE152418 and GSE100927) were downloaded from GEO database to search for common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and shared pathways. A total of 34 DEGs were identified. Among them, ten hub genes with high degrees of connectivity were picked out, namely C1QA, C1QB, C1QC, CD163, SIGLEC1, APOE, MS4A4A, VSIG4, CCR1 and STAB1. This study suggests the critical role played by Complement and coagulation cascades in COVID-19 and atherosclerosis. Our findings underscore the importance of C1q in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and atherosclerosis. Activation of the complement system can lead to endothelial dysfunction. The DEGs identified in this study provide new biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets for the prevention of atherosclerosis.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been a global pandemic since early 2020. According to the WHO, until March 9, 2022, the number of confirmed cases worldwide was 448,313,293, including 6,011,482 deaths (1). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a global effort is in progress to develop a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccination can help control SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks by preventing infection, reducing disease severity, and blocking transmission (2). COVID-19 is typically characterized by upper respiratory symptoms, including fever, cough, and fatigue, and it is often accompanied by pulmonary infection (3). In addition to typical symptoms, some patients have serious cardiovascular damage, or even the first symptoms. (4) Except for the traditional established risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as age, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, viral infection has been supposed to be a potential implication in atherosclerosis (5). SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2 to gain intracellular entry, leading to endothelial dysfunction (6). SARS-CoV-2 also promotes the accumulation of perivascular adipose tissue (7). These may exacerbate the underlying pathology of cardiovascular disease, leading to accelerated progression of atherosclerosis.

The purpose of this study was to explore the pathophysiological association between SARS-CoV-2 and atherosclerosis, and to better understand the underlying mechanisms, so as to facilitate early detection and prevention of atherosclerosis. Two gene expression datasets (GSE152418 and GSE100927) were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. We used bioinformatics and enrichment analysis to determine the common DEGs and their functions for COVID-19 and atherosclerosis. In addition, protein protein interaction (PPI) networks were established to reveal hub genes. These data can better understand the potential link between the two diseases and provide evidence for therapeutic targets.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

The GSE152418 and GSE100927 gene expression profile were obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) [Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Homo sapiens)] platform was used for the GSE152418 dataset where samples were got from seventeen COVID-19 patients, and seventeen healthy people. On the contrary, for the GSE100927 dataset, GPL17077 [Agilent-039494 SurePrint G3 Human GE v2 8x60K Microarray 039381 (Probe Name version)] platform was adopted where samples were collected from sixty-nine atherosclerotic patients and thirty-five control subjects (Table 1).

Table 1

| Disease name | Dataset ID | Subjects | GEO platform | Number of samples(control/disease) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | GSE152418 | Peripheral blood mononuclear cell | GPL24676 | 17/17 |

| Atherosclerosis | GSE100927 | Carotid, femoral and infra-popliteal arteries | GPL17077 | 35/69 |

Basic information of the two microarray databases derived from the GEO database.

GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; COVID-19, Coron a Virus Disease 2019.

Disease ontology (DO) analysis

Firstly, the “edgeR” package was applied to screen Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) from the GSE152418 dataset and a adjusted P less than 0.05, and |log2 Fold change (FC)| more than or equal to 1 was set as a cut-off point for selecting DEGs. The “DOSE” (8). and “ClusterProfiler” (9). packages were then used for DO analysis to study the disease mechanism by looking for disease correlation. DO analysis is a method based on the study of disease similarity, and it plays a vital role in understanding the pathogenesis of complex diseases, the early prevention and diagnosis of major diseases, new drug development, and drug safety evaluation.

Acquisition of common genes

The LIMMA package was used to detect the DEGs between atherosclerotic patients and healthy control from the GSE100927 dataset, and the adjusted P-value and |log2FC| were calculated. Genes that met the cutoff criteria, adjusted P < 0.05 and |log2FC| more than or equal to 1.0, were considered as DEGs. Then the common genes of the GSE152418 and GSE100927 sets were identified by using the Venn diagram webtool (bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

Enrichment analysis of common genes

To further analyze biological processes of common DEGs, GO annotation analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were carried out through the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery [DAVID (2021 Update), https://david.ncifcrf.gov/]. P-Value < 0.05 was used as the enrichment screening condition.

Construction PPI network and selection hub genes

The PPI network was predicted using Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, version 11.5, http://string-db.org/) online database. The PPI pairs were extracted with a interaction score more than or equal to 0.15, and then the PPI network was visualized by Cytoscape software (www.cytoscape.org/). Here, we used Degree to evaluate and select hub genes.

Results

DO analysis

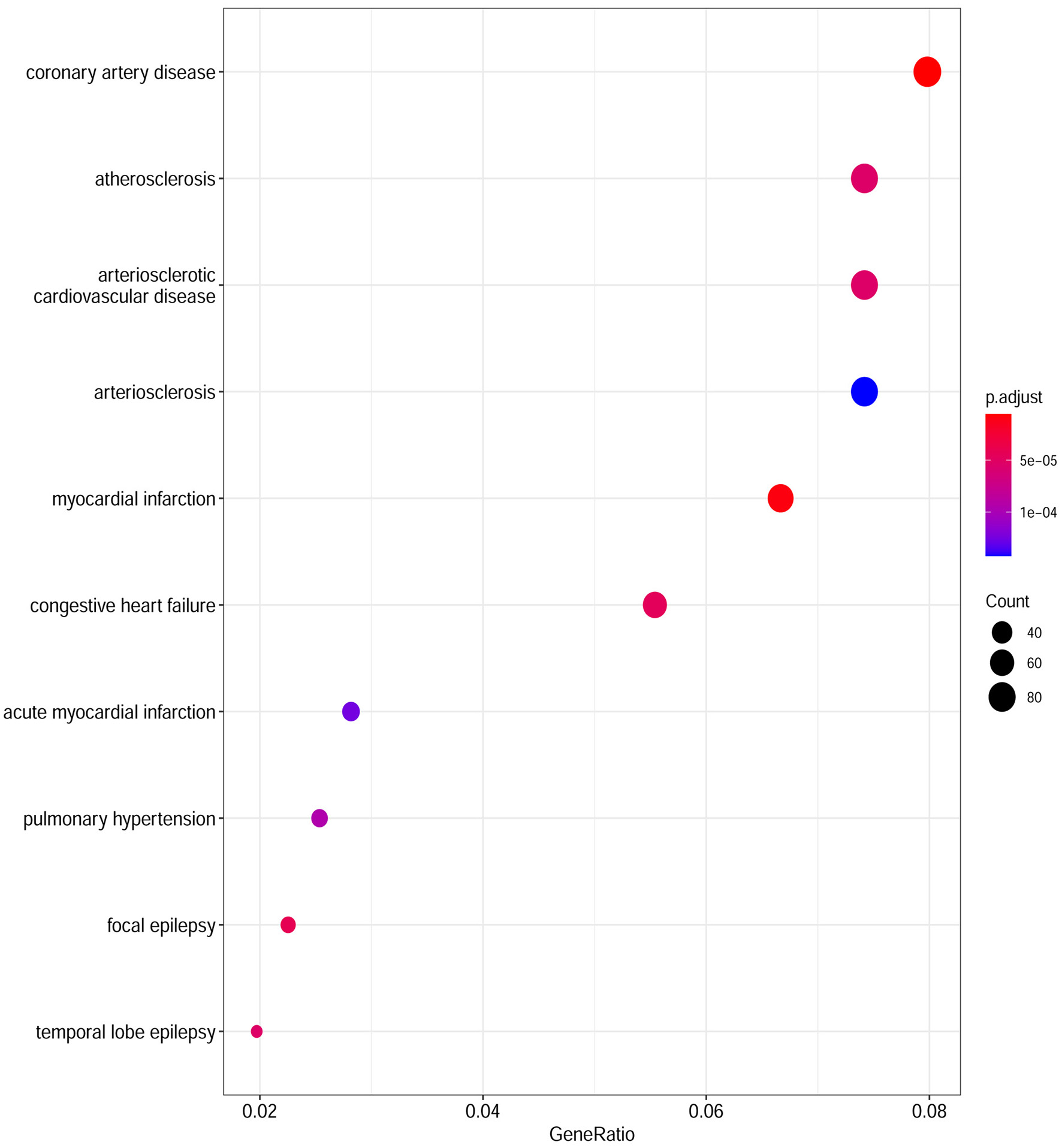

Based on the cut-off criteria of adjusted P < 0.05 and |log2FC| more than or equal to 1, a total of 2080 DEGs were identified from GSE152418, including 1905 upregulated genes and 175 downregulated genes. p.adjust < 0.05 and gene counts more than or equal to 20 were used as the DO screening condition. Figure 1 shows the top ten most significantly enriched diseases, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, arteriosclerosis, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary hypertension, focal epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy. The enrichment results of other diseases by DO analysis are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1

Disease Ontology (DO) analysis of the DEGs from the GSE152418 dataset. The size of the circle represents the number of genes involved, and the abscissa represents the frequency of the genes involved in the term total genes.

Table 2

| DO ID | Description | Count | P-Value | P-Adjust |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOID:3393 | Coronary artery disease | 85 | 6.97E−09 | 5.83E−06 |

| DOID:5844 | Myocardial infarction | 71 | 2.17E−08 | 9.07E−06 |

| DOID:2234 | Focal epilepsy | 24 | 1.52E−07 | 4.24E−05 |

| DOID:6000 | Congestive heart failure | 59 | 2.20E−07 | 4.59E−05 |

| DOID:3328 | Temporal lobe epilepsy | 21 | 3.18E−07 | 5.32E−05 |

| DOID:1936 | Atherosclerosis | 79 | 3.97E−07 | 5.38E−05 |

| DOID:2348 | Arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease | 79 | 4.50E−07 | 5.38E−05 |

| DOID:6432 | Pulmonary hypertension | 27 | 9.09E−07 | 9.50E−05 |

| DOID:9408 | Acute myocardial infarction | 30 | 1.34E−06 | 0.000124898 |

| DOID:2349 | Arteriosclerosis | 79 | 1.70E−06 | 0.000142212 |

| DOID:5679 | Retinal disease | 77 | 7.92E−06 | 0.000601666 |

| DOID:1168 | Familial hyperlipidemia | 26 | 1.20E−05 | 0.000834386 |

| DOID:3146 | Lipid metabolism disorder | 28 | 1.34E−05 | 0.00085861 |

| DOID:1793 | Pancreatic cancer | 69 | 1.94E−05 | 0.00115929 |

| DOID:850 | Lung disease | 98 | 2.75E−05 | 0.001532539 |

| DOID:4450 | Renal cell carcinoma | 72 | 3.34E−05 | 0.001746893 |

| DOID:8466 | Retinal degeneration | 58 | 3.98E−05 | 0.001958846 |

| DOID:6364 | Migraine | 23 | 4.23E−05 | 0.00196426 |

| DOID:3324 | Mood disorder | 45 | 5.17E−05 | 0.00227529 |

| DOID:0080000 | Muscular disease | 82 | 5.54E−05 | 0.002316532 |

| DOID:263 | Kidney cancer | 86 | 8.04E−05 | 0.003053437 |

| DOID:3459 | Breast carcinoma | 77 | 9.26E−05 | 0.003364892 |

| DOID:0060037 | Developmental disorder of mental health | 75 | 0.000113602 | 0.003794572 |

| DOID:1826 | Epilepsy syndrome | 46 | 0.000118977 | 0.003794572 |

| DOID:4451 | Renal carcinoma | 76 | 0.000122552 | 0.003794572 |

| DOID:1686 | Glaucoma | 29 | 0.00014554 | 0.004217764 |

| DOID:2355 | Anemia | 53 | 0.0001587 | 0.004416723 |

| DOID:2742 | Auditory system disease | 27 | 0.000187263 | 0.00470284 |

| DOID:936 | Brain disease | 87 | 0.000192221 | 0.00470284 |

| DOID:15 | Reproductive system disease | 76 | 0.000205883 | 0.00470284 |

| DOID:120 | Female reproductive organ cancer | 87 | 0.000207772 | 0.00470284 |

| DOID:74 | Hematopoietic system disease | 90 | 0.00020814 | 0.00470284 |

| DOID:3996 | Urinary system cancer | 94 | 0.000217288 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:4074 | Pancreas adenocarcinoma | 38 | 0.000234928 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:0060040 | Pervasive developmental disorder | 45 | 0.000239673 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:0060116 | Sensory system cancer | 34 | 0.000241385 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:2174 | Ocular cancer | 34 | 0.000241385 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:0060041 | Autism spectrum disorder | 43 | 0.000254915 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:12849 | Autistic disorder | 43 | 0.000254915 | 0.00473576 |

| DOID:18 | Urinary system disease | 90 | 0.000280864 | 0.005097229 |

| DOID:3083 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 48 | 0.000286567 | 0.005097229 |

| DOID:423 | Myopathy | 77 | 0.00033099 | 0.005647089 |

| DOID:66 | Muscle tissue disease | 77 | 0.00033099 | 0.005647089 |

| DOID:374 | Nutrition disease | 67 | 0.000399054 | 0.006672186 |

| DOID:0050700 | Cardiomyopathy | 35 | 0.000449318 | 0.007240401 |

| DOID:6713 | Cerebrovascular disease | 29 | 0.000459021 | 0.007240401 |

| DOID:654 | Overnutrition | 64 | 0.000496562 | 0.007574304 |

| DOID:4905 | Pancreatic carcinoma | 50 | 0.000498309 | 0.007574304 |

| DOID:557 | Kidney disease | 86 | 0.000522392 | 0.007798559 |

| DOID:4645 | Retinal cancer | 29 | 0.000620866 | 0.008650729 |

| DOID:9970 | Obesity | 62 | 0.000663498 | 0.008946528 |

| DOID:1115 | Sarcoma | 42 | 0.000711231 | 0.009147531 |

| DOID:229 | Female reproductive system disease | 42 | 0.000711231 | 0.009147531 |

| DOID:2320 | Obstructive lung disease | 61 | 0.000734442 | 0.009302929 |

| DOID:10534 | Stomach cancer | 55 | 0.000950468 | 0.011515815 |

| DOID:768 | Retinoblastoma | 28 | 0.001033977 | 0.012138426 |

| DOID:771 | Retinal cell cancer | 28 | 0.001033977 | 0.012138426 |

| DOID:3312 | Bipolar disorder | 35 | 0.001091638 | 0.012501503 |

| DOID:9352 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 45 | 0.001110794 | 0.012548966 |

| DOID:5041 | Esophageal cancer | 33 | 0.001158125 | 0.012909231 |

| DOID:3770 | Pulmonary fibrosis | 29 | 0.001261354 | 0.013519123 |

| DOID:403 | Mouth disease | 40 | 0.001484673 | 0.015136423 |

| DOID:26 | Pancreas disease | 37 | 0.001605415 | 0.015977706 |

| DOID:633 | Myositis | 21 | 0.001648237 | 0.016210895 |

| DOID:0060085 | Organ system benign neoplasm | 52 | 0.00167946 | 0.01632591 |

| DOID:4607 | Biliary tract cancer | 38 | 0.001807765 | 0.017371169 |

| DOID:0060084 | Cell type benign neoplasm | 85 | 0.002061029 | 0.019359779 |

| DOID:657 | Adenoma | 64 | 0.002109774 | 0.019597453 |

| DOID:1074 | Kidney failure | 34 | 0.002145424 | 0.019709612 |

| DOID:48 | Male reproductive system disease | 30 | 0.002200606 | 0.019996808 |

| DOID:865 | Vasculitis | 28 | 0.002325529 | 0.020904752 |

| DOID:8398 | Osteoarthritis | 39 | 0.002473537 | 0.021998689 |

| DOID:0060100 | Musculoskeletal system cancer | 79 | 0.002508247 | 0.022023954 |

| DOID:299 | Adenocarcinoma | 34 | 0.002676763 | 0.022177269 |

| DOID:5223 | Infertility | 42 | 0.002695257 | 0.022177269 |

| DOID:3082 | Interstitial lung disease | 36 | 0.00271993 | 0.022177269 |

| DOID:1575 | Rheumatic disease | 39 | 0.002732367 | 0.022177269 |

| DOID:418 | Systemic scleroderma | 39 | 0.002732367 | 0.022177269 |

| DOID:419 | Scleroderma | 39 | 0.002732367 | 0.022177269 |

| DOID:2394 | Ovarian cancer | 59 | 0.002780859 | 0.022331756 |

| DOID:201 | Connective tissue cancer | 68 | 0.002894952 | 0.022331756 |

| DOID:10952 | Nephritis | 32 | 0.002911676 | 0.022331756 |

| DOID:3620 | Central nervous system cancer | 28 | 0.002988188 | 0.022505631 |

| DOID:0080015 | Physical disorder | 30 | 0.003147388 | 0.023285098 |

| DOID:4960 | Bone marrow cancer | 61 | 0.003537522 | 0.025494557 |

| DOID:0070004 | Myeloma | 60 | 0.003905917 | 0.026264796 |

| DOID:2621 | Autonomic nervous system neoplasm | 68 | 0.004049339 | 0.026264796 |

| DOID:769 | Neuroblastoma | 68 | 0.004049339 | 0.026264796 |

| DOID:1091 | Tooth disease | 34 | 0.004084239 | 0.026264796 |

| DOID:10825 | Essential hypertension | 27 | 0.004708132 | 0.028812356 |

| DOID:289 | Endometriosis | 21 | 0.00483272 | 0.029276479 |

| DOID:854 | Collagen disease | 40 | 0.005216331 | 0.03128014 |

| DOID:1107 | Esophageal carcinoma | 27 | 0.005290025 | 0.031364972 |

| DOID:0050737 | Autosomal recessive disease | 61 | 0.005365584 | 0.031588932 |

| DOID:0060036 | Intrinsic cardiomyopathy | 29 | 0.00544447 | 0.03160817 |

| DOID:127 | Leiomyoma | 22 | 0.005828457 | 0.032922905 |

| DOID:37 | Skin disease | 63 | 0.00656053 | 0.035847078 |

| DOID:1192 | Peripheral nervous system neoplasm | 70 | 0.006679809 | 0.036261818 |

| DOID:552 | Pneumonia | 24 | 0.007057917 | 0.037823198 |

| DOID:4766 | Embryoma | 63 | 0.007450764 | 0.039423029 |

| DOID:3388 | Periodontal disease | 29 | 0.008300314 | 0.04322301 |

| DOID:16 | Integumentary system disease | 69 | 0.008758512 | 0.044109131 |

| DOID:0060038 | Specific developmental disorder | 42 | 0.009006264 | 0.044816886 |

| DOID:12930 | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 21 | 0.009380129 | 0.04640111 |

| DOID:230 | Lateral sclerosis | 24 | 0.009987727 | 0.047987012 |

Significantly enriched DO terms of DEGs.

DEG, Differentially Expressed Gene; DO, Disease Ontology; ID, Identity Document.

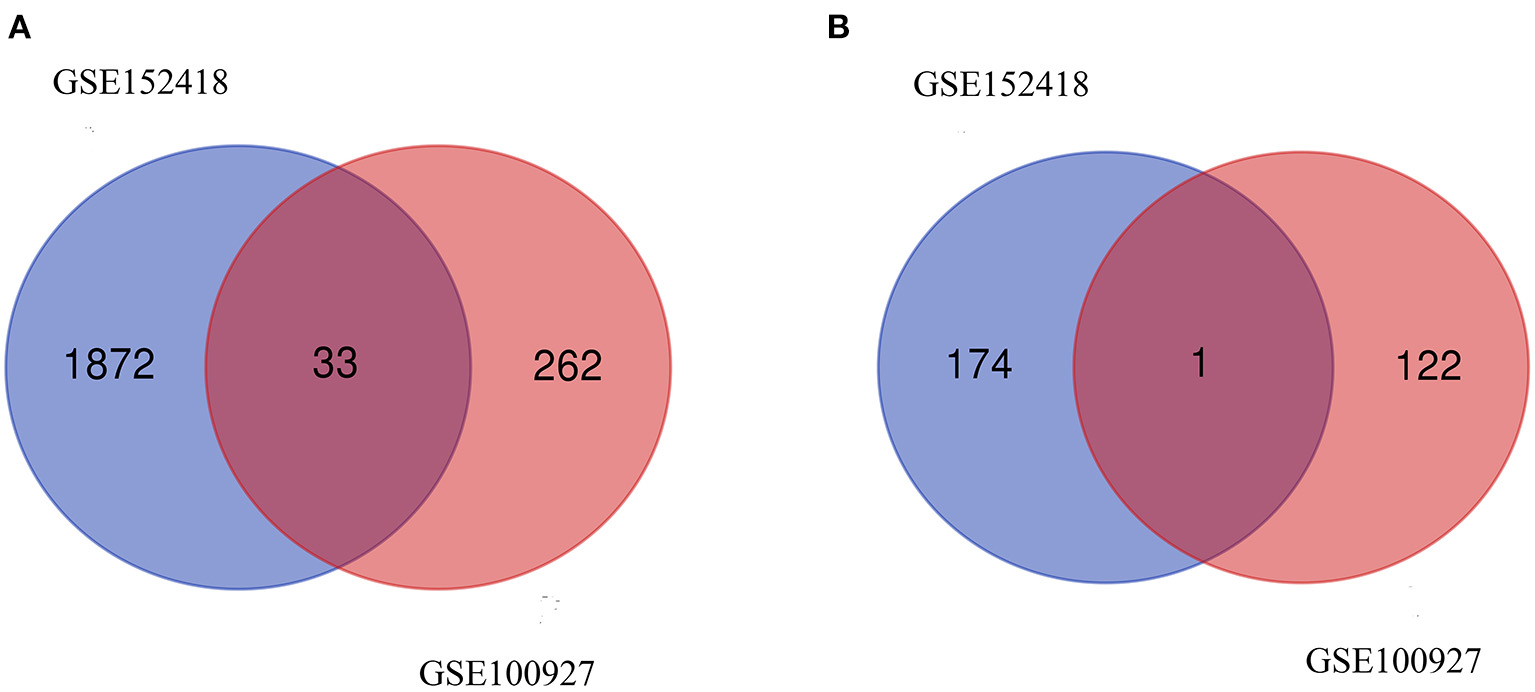

Identification of common DEGs

From GSE100927, 418 DEGs including 295 upregulated genes and 123 downregulated genes were identified. We analyzed the intersection of the DEG profiles using Venn (Figure 2). Ultimately, 34 DEGs were significantly differentially expressed in two datasets, of which 33 were significantly upregulated genes and 1 was downregulated gene.

Figure 2

Venn diagram. (A) Upregulated common DEGs of the GSE152418 and GSE100927 datasets. (B) Downregulated common DEGs of the GSE152418 and GSE100927 datasets.

Gene ontology and pathway enrichment analysis

GO and KEGG pathway analyses for DEGs were performed using the DAVID. The biological processes of DEGs were primarily associated with synapse disassembly, complement activation and innate immune response. For the cell component, the DEGs were enriched in extracellular region, blood microparticle, hemoglobin complex, collagen trimer, and so on. Molecular functions analysis showed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in oxygen transporter activity, oxygen binding, scavenger receptor activity, voltagE–gated potassium channel activity involved in atrial cardiac muscle cell action potential repolarization, phosphatidylcholinE–sterol O-acyltransferase activator activity, haptoglobin binding, organic acid binding and heme binding (Table 3). In addition, the KEGG pathway analysis showed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in Complement and coagulation cascades, Pertussis, Coronavirus disease—COVID-19, Staphylococcus aureus infection, Chagas disease, Systemic lupus erythematosus and Alcoholic liver disease (Table 4).

Table 3

| GO ID | Description | Count | P-Value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological process | ||||

| GO:0098883 | Synapse disassembly | 3 | 6.04E−05 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| GO:0006958 | Complement activation, classical pathway | 5 | 8.67E−05 | C1QB, C1QA, IGLL5, IGLL1, C1QC |

| GO:0045087 | Innate immune response | 7 | 2.32E−04 | C1QB, C1QA, IGLL5, VNN1, IGLL1, C1QC, OASL |

| GO:0006898 | Receptor-mediated endocytosis | 4 | 0.001825851 | CD163, STAB1, HBA2, APOE |

| GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 5 | 0.002915761 | CCR1, VNN1, STAB1, SPP1, SIGLEC1 |

| GO:0098869 | Cellular oxidant detoxification | 3 | 0.00591978 | HBA2, HBD, APOE |

| GO:0042159 | Lipoprotein catabolic process | 2 | 0.007472267 | APOE, CTSD |

| GO:0098914 | Membrane repolarization during atrial cardiac muscle cell action potential | 2 | 0.007472267 | KCNJ5, KCNA5 |

| GO:0006956 | Complement activation | 3 | 0.008884327 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| GO:0034447 | Very-low-density lipoprotein particle clearance | 2 | 0.008960238 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0034382 | Chylomicron remnant clearance | 2 | 0.010446055 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0030449 | Regulation of complement activation | 3 | 0.012175792 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| GO:0010873 | Positive regulation of cholesterol esterification | 2 | 0.013411239 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0033700 | Phospholipid efflux | 2 | 0.017842935 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0044267 | Cellular protein metabolic process | 3 | 0.021136392 | MMP1, SPP1, APOE |

| GO:0015671 | Oxygen transport | 2 | 0.022255408 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0015909 | Long-chain fatty acid transport | 2 | 0.025186416 | FABP5, APOE |

| GO:0034375 | High-density lipoprotein particle remodeling | 2 | 0.026648738 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0042157 | Lipoprotein metabolic process | 2 | 0.032476871 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0033344 | Cholesterol efflux | 2 | 0.036825845 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0045671 | Negative regulation of osteoclast differentiation | 2 | 0.039714668 | MAFB, LILRB4 |

| GO:0032703 | Negative regulation of interleukin-2 production | 2 | 0.041155941 | VSIG4, LILRB4 |

| GO:0042744 | Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | 2 | 0.041155941 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 2 | 0.042595125 | AQP9, KCNA5 |

| GO:0007267 | Cell-cell signaling | 3 | 0.045927718 | CCR1, C1QA, STAB1 |

| GO:0042742 | Defense response to bacterium | 3 | 0.046288292 | IGLL5, IGLL1, STAB1 |

| Cellular component | ||||

| GO:0005576 | Extracellular region | 17 | 2.40E−08 | C1QB, C1QA, CD163, CD163L1, MMP1, HBA2, VNN1, FNDC1, FABP5, IGLL1, APOC1, SPP1, PLBD1, SIGLEC1, APOE, CTSD, C1QC |

| GO:0072562 | Blood microparticle | 5 | 7.68E−05 | C1QB, HBA2, HBD, APOE, C1QC |

| GO:0005833 | Hemoglobin complex | 3 | 2.19E−04 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0005581 | Collagen trimer | 4 | 4.28E−04 | C1QB, C1QA, MMP1, C1QC |

| GO:0009897 | External side of plasma membrane | 6 | 6.43E−04 | CCR1, KCNJ5, IGLL5, CD163, CD163L1, IGLL1 |

| GO:0005602 | Complement component C1 complex | 2 | 0.003171533 | C1QB, C1QA |

| GO:0098794 | Postsynapse | 3 | 0.012921039 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| GO:0031838 | Haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex | 2 | 0.017323254 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0042627 | Chylomicron | 2 | 0.021997095 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0071682 | Endocytic vesicle lumen | 2 | 0.028195396 | HBA2, APOE |

| GO:0016021 | Integral component of membrane | 15 | 0.028427769 | PTCRA, CCR1, KCNJ5, CD163, CD163L1, AQP9, KCNA5, HBD, LILRB4, MS4A4A, VNN1, SLCO2B1, STAB1, SIGLEC1, VSIG4 |

| GO:0034361 | Very-low-density lipoprotein particle | 2 | 0.03281913 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0045202 | Synapse | 4 | 0.041387143 | C1QB, C1QA, FABP5, C1QC |

| GO:0034364 | High-density lipoprotein particle | 2 | 0.042002749 | APOC1, APOE |

| Molecular function | ||||

| GO:0005344 | Oxygen transporter activity | 3 | 3.12E−04 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0019825 | Oxygen binding | 3 | 0.001605913 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0005044 | Scavenger receptor activity | 3 | 0.002957949 | CD163, CD163L1, STAB1 |

| GO:0086089 | Voltage–gated potassium channel activity involved in atrial cardiac muscle cell action potential repolarization | 2 | 0.006590464 | KCNJ5, KCNA5 |

| GO:0060228 | Phosphatidylcholine–sterol O-acyltransferase activator activity | 2 | 0.009869914 | APOC1, APOE |

| GO:0031720 | Haptoglobin binding | 2 | 0.016397412 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0043177 | Organic acid binding | 2 | 0.018022768 | HBA2, HBD |

| GO:0020037 | Heme binding | 3 | 0.025666884 | HBA2, HBD |

Significantly enriched GO terms of DEGs.

DEG, Differentially Expressed Gene; GO, Gene Ontology; ID, Identity Document.

Table 4

| KEGG ID | Description | Count | P-Value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 4 | 0.001112855 | C1QB, C1QA, VSIG4, C1QC |

| hsa05133 | Pertussis | 3 | 0.014757214 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| hsa05171 | Coronavirus disease—COVID-19 | 4 | 0.018374812 | C1QB, C1QA, MMP1, C1QC |

| hsa05150 | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 3 | 0.022928086 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| hsa05142 | Chagas disease | 3 | 0.02567277 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| hsa05322 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3 | 0.043532485 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

| hsa04936 | Alcoholic liver disease | 3 | 0.047059029 | C1QB, C1QA, C1QC |

Significantly enriched KEGG terms of DEGs.

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ID, Identity Document; DEG, Differentially Expressed Gene.

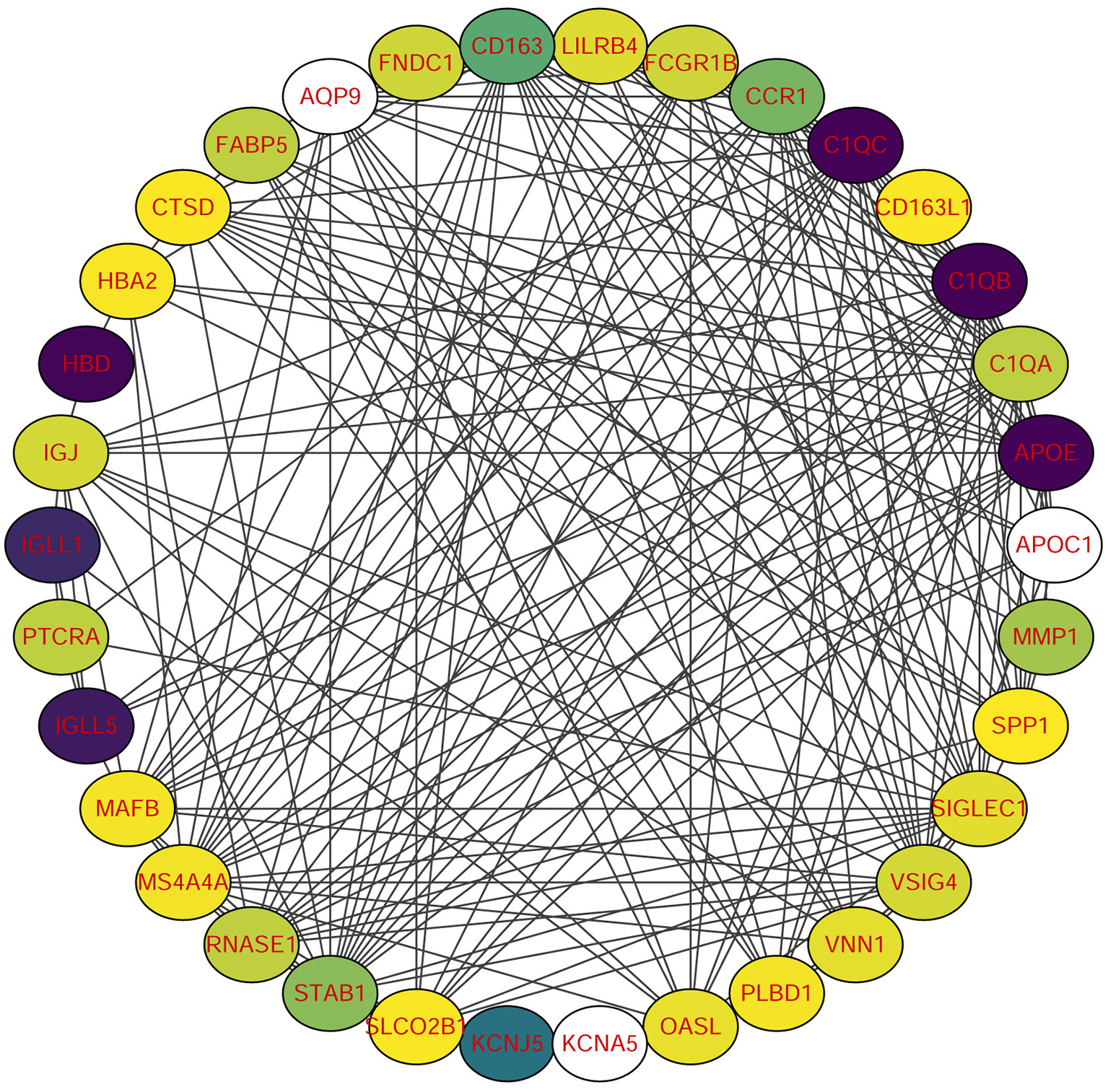

PPI network construction and hub gene identification

Using STRING tools, we predicted protein interactions among DEGs. The PPI network presented in Figure 3 consists of 34 nodes and 209 edges. Based on the PPI network, we identified 10 genes with the highest connectivity degree (Table 5). The results showed that C1QA was the most outstanding gene with connectivity degree = 24, followed by C1QB (degree = 23), C1QC (degree = 22), CD163 (degree = 22), SIGLEC1 (degree = 21), APOE (degree = 19), MS4A4A (degree = 19), VSIG4 (degree = 18), CCR1 (degree = 18), STAB1 (degree = 18).

Figure 3

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of common DEGs among SRAS-CoV-2 and atherosclerosis. In the figure, the circle nodes represent DEGs and edges represent interactions between nodes.

Table 5

| Gene symbol | Gene description | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| C1QA | Complement C1q A chain | 24 |

| C1QB | Complement C1q B chain | 23 |

| C1QC | Complement C1q C chain | 22 |

| CD163 | CD163 molecule | 22 |

| SIGLEC1 | Sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 1 | 21 |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E | 19 |

| MS4A4A | Membrane spanning 4-domains A4A | 19 |

| VSIG4 | V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 4 | 18 |

| CCR1 | C-C motif chemokine receptor 1 | 18 |

| STAB1 | Stabilin 1 | 18 |

Top ten hub genes with higher degree of connectivity.

Discussion

Some diseases, thought to be unrelated, share the same biological processes (10). We conducted the DO analysis on the GSE152418 dataset to find the similarity between diseases and COVID-19, and found that COVID-19 was most significantly associated with atherosclerosis among various diseases. Our results suggest that COVID-19 will lead to faster atherosclerosis. Then, we took the intersection of two datasets, GSE152418 and GSE100927, to identify common genes between COVID-19 and atherosclerosis. After obtaining 34 common genes, the GO, pathway, PPI networks were further analyzed.

GO enrichment analysis showed that C1QA, C1QB, C1QC were significantly enriched in synapse disassembly, complement activation, and innate immune response. Complement 1q (C1q) is composed of six subunits, which form a molecule containing 18 polypeptide chains, while C1qA, C1qB, and C1qC genes encode three types of polypeptide chains, A, B, and C of the subunit of C1q, respectively (11). C1q is an important recognition molecule to initiate the classical pathway involved in the complement activation and function, playing a major role in the connection between innate and specific immunity. (12, 13). After identifying the complement binding site on the antibody Fc segment of the IgM or IgG immune complex, the complement cascade will be activated to clear the antigen-antibody complexes (14). Complement proteins specifically locate apoptotic, immature or weak developing synapses in the central nervous system (15). The number of those apoptotic markers in the synapse is equal to the localization of C1q, which promotes synaptic pruning (16). A study found that of 281 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, 21.1% had dementia and 8.9% had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (17). Moreover, high activation of C1q leads to a large number of synaptic loss which is associated with the development of Alzheimer's disease (18). Then, does the activation of complement system C1q cause cognitive impairment in COVID-19 patients?

KEGG enrichment analysis is the best way to reflect the changes of pathways in organisms. Those results indicate that complement and coagulation cascades change most significantly in atherosclerosis and COVID-19. Macor et al. found positive lung C1q staining which suggests that the classical pathway is important for complement activation which may be triggered by IgG, antibodies widely distributed in patients' lungs (19). In atherosclerosis plaques, C1q activates the classical complement pathway by recognizing oxidized low-density lipoprotein auto-antibodies or directly binding modified lipoprotein and cholesterol crystal (20). Endothelial dysfunction, an important mechanism for the formation and development of atherosclerosis, can be caused by the activation of the complement system can lead to (20). Gao et al. demonstrated that subsequent endothelial dysfunction persisted in COVID-19 survivors even 327 days after diagnosis (6). The activated fragments generated after the activation of the complement system may be closely related to the coagulation and fibrinolytic system and inflammation in COVID-19 patients, so additional studies on the changes in the number of fragments and tissue distribution are needed.

The 10 hub genes selected by PPI were C1QA, C1QB, C1QC, CD163, SIGLEC1, APOE, MS4A4A, VSIG4, CCR1, and STAB1. The C1QA, C1QB, and C1QC genes had the highest degree in the PPI networks. Then v-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 4 (VSIG4) is the receptor of complement component 3 fragments C3b and iC3b, which activates macrophage immunity through C3b/iC3b binding (21). VSIG4 may be involved in lung injury through induction of phagocytosis (22). VSIG4 activate macrophages, through induction of chemokines, promote the migration of inflammatory cells to the lesion area, and participate in the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis (23). Increased expressions of C1QA, C1QB, C1QC, and VSIG4 all relate to enhanced complement system. CD163, a scavenger receptor, is a major component of inflammation and the immune response. Among plasmacytoid dendritic cells, type I interferon is induced with the appearance of CD163+ SIGLEC1+ macrophages with increased angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) levels (24). Macrophages are highly enriched in the lungs of macaques at peak viremia and harbor the SARS-CoV-2 virus while also expressing an interferon-driven innate antiviral gene signature (25). CD163(+) macrophages promote angiogenesis, vascular permeability and inflammation in atherosclerosis via the CD163/HIF1α/VEGF-A pathway. The increased expression of CD163 was revealed in ruptured coronary plaques (26). There are three APOE isoforms, namely APOE epsilon2 (APOE2), APOE epsilon3 (APOE3) and APOE epsilon4 (APOE4) located on chromosome 19q13.2 (27). APOE can function as an endogenous, concentration-dependent pulmonary danger signal that primes and activates the NLPR3 inflammasome in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid macrophages from asthmatic subjects to secrete IL-1β (28). A recent study in the UK Biobank Cohort, APOE4 has been shown to associate with increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality (29). APOE is a therapeutic target for statins that inhibit inflammation in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Statins possess antiviral, immunomodulatory, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory properties, which may improve short- and long-term outcomes in COVID-19 patients.

STAB1 encodes an unusual type of multifunctional scavenger receptor that causes increased lipid uptake and transient lipid depletion in virus-infected areas and is associated with poor prognosis for COVID-19 (30). STAB1 expression may contribute to foam cell formation, monocyte adhesion/migration, and regulation of inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions (31). Lectins such as sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 1 (SIGLEC1/CD169) mediate the attachment of viruses to Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (32). SIGLEC1 expression is induced on APCs upon IFN-α or LPS exposure and increased in myeloid cells of COVID-19 patients (33) Inhibition of Siglec-1 prevents monocytes from adhering to vascular endothelial cells in the early stage of atherosclerosis, and reduces lipid phagocytosis and chemokine secretion of macrophages, alleviating the inflammatory response of established fat streaking lesions (34). CCR1 is critical mediators of monocyte/macrophage polarization and tissue infiltration, which are pathogenic hallmarks of severe COVID-19 (35). The use of monocyte CCR1 in arterial recruitment is due in part to activated chemokines of platelet deposition, which is important in the early stages of atherosclerosis (36). MS4A4A is a novel M2 macrophage cell surface marker, which is essential for dectin-1-dependent activation of NK cell-mediated anti-metastatic properties (37). Silva-Gomes et al. found MS4A4A was expressed by MΦs or alveolar MΦs in COVID-19 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (38).

Through DO analysis, we also found several neurological disorders associated with COVID-19, such as focal epilepsy, temporal lobe epilepsy, migraine, epilepsy syndrome, neuroblastoma, and lateral sclerosis. There have been a large number of reported cases of these conditions, with a seizure prevalence ranging from 0 to 26% in COVID-19 patients (39, 40). Moreover, seizures may be related to cerebrovascular disease and central nervous system infection. Vascular endothelial injury leads to hypercoagulability and microembolism, resulting in reduced cortical blood flow accompanied by hypoxia. Vascular endothelial dysfunction can lead to changes in the nervous system, resulting in neurological sequelae (41). The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study also revealed that migraine patients were more susceptible to retinopathy (retinal hemorrhage, macular oedema, retinal microvascular abnormalities, venous bleeding, etc.) than non-migraine patients, and retinopathy was more strongly associated with migraine in people without a history of diabetes or hypertension (42). Interestingly, we also discovered DEGs enrichment in retinopathy. Besides, previous animal-based experimental studies of the coronavirus infection reported retinal diseases such as retinal vasculitis and retinal degeneration. Moreover, blood-retinal barrier breakdown revealed the possibility of immune-privileged site infectivity by SARS-CoV-2 (43). We believe that SARS-CoV-2 causes vascular injury and may lead to retinal degeneration. Results also revealed different types of cancer, such as pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, breast carcinoma, stomach cancer, esophageal cancer, and ovarian cancer. In patients with COVID19, severe illness and mortality are closely related to cancer. SARS CoV 2 may promote tumor progression and stimulate metabolic switching in tumor cells to initiate tumor metabolic modes with higher production efficiency, such as glycolysis, for facilitating the replication of SARS CoV 2 (44). Meanwhile, we also established that muscular disease, such as myositis, is associated with COVID-19. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with dermatomyositis have three immunogenic linear epitopes with a high degree of sequence identity to the SARS-CoV-2 protein, so potential exposure to the coronavirus family may lead to the development of dermatomyositis (45). Effective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for dermatomyositis, including tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, and baricitinib, may provide new directions for COVID-19 treatment.

In conclusion, the study provides new insights for the common pathogenesis of COVID-19 and atherosclerosis by looking for common transcriptional features. The DEGs identified by bioinformatics data analysis, including C1QA, C1QB, C1QC, CD163, SIGLEC1, APOE, MS4A4A, VSIG4, CCR1, and STAB1, may be therapeutic targets for the atherosclerosis caused by COVID-19. However, more wet lab-based studies are required to validate the impact of COVID-19 severity on atherosclerosis. Studies on the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the effect of persistent endothelial dysfunction on atherosclerosis, and the role of preventive therapy are also needed.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

JZ performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript. LZ helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge GEO database for providing their platforms and contributors for uploading their meaningful datasets.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

WHO COVID-19 Dashboard (2020). Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed March 9, 2022).

2.

Callaway E . The race for coronavirus vaccines: a graphical guide. Nature. (2020) 580:576–7. 10.1038/d41586-020-01221-y

3.

Zheng Y Xu H Yang M Zeng Y Chen H Liu R et al . Epidemiological characteristics and clinical features of 32 critical and 67 noncritical cases of COVID-19 in Chengdu. J Clin Virol. (2020) 127:104366. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104366

4.

Huang C Wang Y Li X Ren L Zhao J Hu Y et al . Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England). (2020) 395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

5.

Gao YP Zhou W Huang PN Liu HY Bi XJ Zhu Y et al . Persistent Endothelial dysfunction in coronavirus diseasE−2019 survivors late after recovery. Front. Med. (2022) 9:809033. 10.3389/fmed.2022.809033

6.

Robson A . Preventing cardiac damage in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2021) 18:387. 10.1038/s41569-021-00550-3

7.

Mester A Benedek I Rat N Tolescu C Polexa SA Benedek T et al . Imaging cardiovascular inflammation in the COVID-19 era. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). (2021) 11:1114. 10.3390/diagnostics11061114

8.

Yu G Wang LG Yan GR He QY . DOSE: an R/Bioconductor package for disease ontology semantic and enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). (2015) 31:608–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu684

9.

Wu T Hu E Xu S Chen M Guo P Dai Z et al . clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (New York. NY). (2021) 2:100141. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141

10.

Butte AJ Kohane IS . Creation and implications of a phenomE–genome network. Nat Biotechnol. (2006) 24:55–62. 10.1038/nbt1150

11.

Lu JH Teh BK Wang LD Wang YN Tan YS Lai MC et al . The classical and regulatory functions of C1q in immunity and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. (2008) 5:9–21. 10.1038/cmi.2008.2

12.

Tenner AJ . C1q interactions with cell surface receptors. Behring Institute Mitteilungen. (1989) 84:220–9.

13.

Mortensen SA Sander B Jensen RK Pedersen JS Golas MM Jensenius JC et al . Structure and activation of C1, the complex initiating the classical pathway of the complement cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:986–91. 10.1073/pnas.1616998114

14.

Sjöberg AP Trouw LA Blom AM . Complement activation and inhibition: a delicate balance. Trends Immunol. (2009) 30:83–90. 10.1016/j.it.2008.11.003

15.

Cornell J Salinas S Huang HY Zhou M . Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Neural Regener Res. (2022) 17:705–16. 10.4103/1673-5374.322423

16.

Györffy BA Kun J Török G Bulyáki É Borhegyi Z Gulyássy P et al . Local apoptotic-like mechanisms underlie complement-mediated synaptic pruning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:6303–8. 10.1073/pnas.1722613115

17.

Martín-Jiménez P Muñoz-García MI Seoane D Roca-Rodríguez L García-Reyne A Lalueza A et al . Cognitive impairment is a common comorbidity in deceased covid-19 patients: a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2020) 78:1367–72. 10.3233/JAD-200937

18.

Stephan AH Barres BA Stevens B . The complement system: an unexpected role in synaptic pruning during development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:369–89. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113810

19.

Macor P Durigutto P Mangogna A Bussani R De Maso L D'Errico PL et al . MultiplE–organ complement deposition on vascular endothelium in COVID-19 patients. Biomedicines. (2021) 9:1003. 10.3390/biomedicines9081003

20.

Samstad EO Niyonzima N Nymo S Aune MH Ryan L Bakke SS et al . Cholesterol crystals induce complement-dependent inflammasome activation and cytokine release. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). (2014) 192:2837–45. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302484

21.

Hertle E Stehouwer CD van Greevenbroek MM . The complement system in human cardiometabolic disease. Mol Immunol. (2014) 61:135–48. 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.06.031

22.

Helmy KY Katschke KJ Gorgani NN Kljavin NM Elliott JM Diehl L et al . CRIg: a macrophage complement receptor required for phagocytosis of circulating pathogens. Cell. (2006) 124:915–27. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.039

23.

Zhao C Mo J Zheng X Wu Z Li Q Feng J et al . Identification of an alveolar macrophagE–related core gene set in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Inflamm Res. (2021) 14:2353–61. 10.2147/JIR.S306136

24.

Lee MY Kim WJ Kang YJ Jung YM Kang YM Suk K et al . Z39Ig is expressed on macrophages and may mediate inflammatory reactions in arthritis and atherosclerosis. J Leukoc Biol. (2006) 80:922–8. 10.1189/jlb.0306160

25.

Singh DK Aladyeva E Das S Singh B Esaulova E Swain A et al . Myeloid cell interferon responses correlate with clearance of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:679. 10.1038/s41467-022-28315-7

26.

Guo L Akahori H Harari E Smith SL Polavarapu R Karmali V et al . CD163+ macrophages promote angiogenesis and vascular permeability accompanied by inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:1106–24. 10.1172/JCI93025

27.

Weisgraber KH Rall SC Mahley RW . Human E apoprotein heterogeneity. CysteinE–arginine interchanges in the amino acid sequence of the apo-E isoforms. J Biol Chem. (1981) 256:9077–83. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52510-8

28.

Gordon EM Yao X Xu H Karkowsky W Kaler M Kalchiem-Dekel O et al . Apolipoprotein E is a concentration-dependent pulmonary danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β secretion by bronchoalveolar fluid macrophages from asthmatic subjects. J Allerg Clin Immunol. (2019) 144:426–441.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.02.027

29.

Kuo CL Pilling LC Atkins JL Masoli J Delgado J Kuchel GA et al . ApoE e4e4 genotype and mortality with COVID-19 in UK Biobank. J Gerontol Ser A, Biol Sci Med Sci. (2020) 75:1801–3. 10.1093/gerona/glaa169

30.

Vlasov I Panteleeva A Usenko T Nikolaev M Izumchenko A Gavrilova E et al . Transcriptomic profiles reveal downregulation of low-density lipoprotein particle receptor pathway activity in patients surviving severe COVID-19. Cells. (2021) 10:3495. 10.3390/cells10123495

31.

Brochériou I Maouche S Durand H Braunersreuther V Le Naour G Gratchev A et al . Antagonistic regulation of macrophage phenotype by M-CSF and GM-CSF: implication in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. (2011) 214:316–24. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.023

32.

Perez-Zsolt D Muñoz-Basagoiti J Rodon J Elosua-Bayes M Raïch-Regué D Risco C et al . SARS-CoV-2 interaction with Siglec-1 mediates trans-infection by dendritic cells. Cell Mol Immunol. (2021) 18:2676–8. 10.1038/s41423-021-00794-6

33.

Bedin AS Makinson A Picot MC Mennechet F Malergue F Pisoni A et al . Monocyte CD169 expression as a biomarker in the early diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect Dis. (2021) 223:562–7. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa724

34.

Xiong YS Wu AL Mu D Yu J Zeng P Sun Y et al . Inhibition of siglec-1 by lentivirus mediated small interfering RNA attenuates atherogenesis in apoE–deficient mice. Clin Immunol (Orlando, Fla). (2017) 174:32–40. 10.1016/j.clim.2016.11.005

35.

Stikker B Stik G Hendriks RW Stadhouders R . Severe COVID-19 associated variants linked to chemokine receptor gene control in monocytes and macrophages. bioRxiv : the preprint server for biology. (2021) 01, 22.427813. 10.1101/2021.01.22.427813

36.

Drechsler M Megens RT van Zandvoort M Weber C Soehnlein O . Hyperlipidemia-triggered neutrophilia promotes early atherosclerosis. Circulation. (2010) 122:1837–45. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.961714

37.

Huo Q Li Z Chen S Wang J Li J Xie N et al . VWCE as a potential biomarker associated with immune infiltrates in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. (2021) 21:272. 10.1186/s12935-021-01955-3

38.

Silva-Gomes R Mapelli SN Boutet MA Mattiola I Sironi M Grizzi F et al . Differential expression and regulation of MS4A family members in myeloid cells in physiological and pathological conditions. J leukocyte Biol. (2021) 111:817–36. 10.1002/JLB.2A0421-200R

39.

Pellinen J Holmes MG . Evaluation and treatment of seizures and epilepsy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2022) 1–7. 10.1007/s11910-022-01174-x

40.

Danoun OA Zillgitt A Hill C Zutshi D Harris D Osman G et al . Outcomes of seizures, status epilepticus, and EEG findings in critically ill patient with COVID-19. Epilepsy Behav: EandB. (2021) 118:107923. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107923

41.

Qin Y Wu J Chen T Li J Zhang G Wu D et al . Long-term microstructure and cerebral blood flow changes in patients recovered from COVID-19 without neurological manifestations. J Clin Invest. (2021) 131:e147329. 10.1172/JCI147329

42.

Rose KM Wong TY Carson AP Couper DJ Klein R Sharrett AR et al . Migraine and retinal microvascular abnormalities: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Neurology. (2007) 68:1694–700. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261916.42871.05

43.

Zhou X Zhou YN Ali A Liang C Ye Z Chen X et al . Case report: a rE–positive case of SARS-CoV-2 Associated With Glaucoma. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:701295. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.701295

44.

Li YS Ren HC Cao JH . Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 to cancer: Carcinogenic or anticancer? (Review). Int J Oncol. (2022) 60:42. 10.3892/ijo.2022.5332

45.

Megremis S Walker T He X Ollier W Chinoy H Hampson L et al . Antibodies against immunogenic epitopes with high sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with autoimmune dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2020) 79:1383–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217522

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, atherosclerosis, C1q, SARS-CoV-2, immune

Citation

Zhang J and Zhang L (2022) Bioinformatics approach to identify the influences of SARS-COV2 infections on atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:907665. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.907665

Received

30 March 2022

Accepted

11 July 2022

Published

18 August 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Mark Slevin, Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Sakir Ahmed, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences (KIMS), India; Erkan Cüre, Bagcilar Medilife Hospital, Turkey

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Zhang and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liming Zhang zlmlimingzz@163.com

This article was submitted to Atherosclerosis and Vascular Medicine, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.