Abstract

Background:

The role of dobutamine during septic shock resuscitation is still controversial.

Methods:

The aim of this prospective multicentre study was to comprehensively characterize the hemodynamic response of septic shock patients with systolic myocardial dysfunction to incremental doses of dobutamine (0, 5, 10, and 15 μg/kg/min).

Results:

Thirty two patients were included in three centers. Dobutamine significantly increased contractility indices of both ventricles [crude and afterload-adjusted left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction, global LV longitudinal peak systolic strain, tissue Doppler peak systolic wave at mitral and tricuspid lateral annulus, and tricuspid annular plane excursion) as well as global function indices (stroke volume and cardiac index) and diastolic function (increased e' and decreased E/e' ratio at lateral mitral annulus). Dobutamine also induced a significant decrease in arterial pressure and cardiac afterload indices (effective arterial elastance, systemic vascular resistance and diastolic shock index). Oxygen transport, oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production all increased with dobutamine, without change in the respiratory quotient or lactate. Dobutamine was discontinued for poor tolerance in a majority of patients (n = 21, 66%) at any dose and half of patients (n = 15, 47%) at low-dose (5 μg/kg/min). Poor tolerance to low-dose dobutamine was more frequent in case of acidosis, was associated with lower vasopressor-free days and survival at day-14.

Conclusion:

In patients with septic myocardial dysfunction, dobutamine induced an overall improvement of echocardiographic parameters of diastolic and systolic function, but was poorly tolerated in nearly two thirds of patients, with worsening vasoplegia. Patients with severe acidosis seemed to have a worse response to dobutamine.

Introduction

Circulatory failure is one of the hallmark alterations in septic shock and involves a variable combination of hypovolemia, vasoplegia and myocardial dysfunction. Septic myocardial dysfunction was first described by Parker et al. in 1984 (1). In recent studies using echocardiography, systolic dysfunction was observed in one third (when assessed by left ventricle ejection fraction, LVEF) and more than two-thirds (when assessed by speckle tracking-derived LV longitudinal peak systolic strain) of patients during septic shock (2). Diastolic dysfunction is also common and is a strong independent predictor of early mortality in septic shock (3).

The surviving sepsis campaign recommends the use of dobutamine in patients who show evidence of persistent hypoperfusion despite adequate fluid loading and the use of vasopressor agents (4). However, the role of dobutamine during septic shock resuscitation is still controversial since most clinical studies have been performed in an unselected population including patients with increased or decreased systolic function (5, 6). Dobutamine failed to improve sublingual microcirculatory and hepatosplanchnic peripheral perfusion parameters or lactate levels in a randomized placebo crossover study (7). In addition, dobutamine may worsen cardiac diastolic function (via its tachycardic effect) and hypotension (via its vasoplegic effect) during septic shock. We hypothesized that despite its beneficial effects on systolic function, dobutamine may alter diastolic function and worsen hypotension in patients with septic myocardial dysfunction.

The aim of this study was to comprehensively characterize the response of patients with septic myocardial dysfunction to incremental doses of dobutamine in terms of macrocirculation, cardiac function (including loading conditions, systolic and diastolic function), microcirculation (mottling), and tissue hypoxia (indirect calorimetry and lactatemia).

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients who met septic shock criteria (as defined according to the Sepsis-3 definition) (8), either from community-acquired or nosocomial infections, were prospectively screened in three intensive care units (ICU) of Greater Paris in France. Norepinephrine was the first-choice vasopressor therapy (used to target a mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg or more). Inclusion criteria were the presence of septic myocardial dysfunction [as defined by depressed LVEF (<45%) at echocardiography on the first or second day of septic shock onset] with ongoing signs of hypoperfusion despite adequate mean arterial pressure and correction of hypovolemia with absence of fluid responsiveness (see study procedure), mandating the introduction of dobutamine as per the physician decision, and in agreement with surviving sepsis campaign recommendations (9). Non-inclusion criteria were chronic heart failure (defined as a baseline LVEF below 45%), severe valvulopathy, moribund state, tachycardia with heart rate >130 bpm, patients already receiving an inotropic agent, hemodynamic instability with mean arterial pressure <65 mmHg despite norepinephrine infusion, and unavailability of trained operators or echocardiography system.

Patient's severity was evaluated by the Mac Cabe and Jackson score for underlying diseases (10), the SAPS II (Simplified Acute Physiologic Score) for acute illness at ICU admission (11), and the SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) score for organ dysfunction at septic shock onset (12).

Study procedure

Tests to predict fluid responsiveness included: i) a “clinical” variable (either pulse pressure or stroke volume variation with a threshold of 12%) (13) and an “echocardiographic” variable (either variation of inferior or superior vena cava diameter) (14); in case of discrepancy between the clinical and echocardiographic variable, the physician performed a fluid challenge: rapid infusion of 250–500 mL saline with fluid unresponsiveness defined as the lack of cardiac output increase (i.e., 10% increase), with fluid challenge, assessed by echocardiography) (15). Dobutamine was started only in patients with fluid unresponsiveness.

An infusion of dobutamine was started at a rate of 5 μg/kg/min, and was sequentially increased to 10 μg/kg/min and 15 μg/kg/min after 30 min intervals, in case of good tolerance. Poor tolerance of dobutamine was defined as one of the following: (i) worsening hypotension (mean arterial pressure <65 mmHg with a decrease of 10 mmHg or more as compared to baseline value or the need to increase norepinephrine infusion by at least 0.5 mg/hour to maintain a mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg); ii) severe tachycardia (new-onset atrial fibrillation or sinus tachycardia >130 beats per minutes with an increase of 10 beats per minute or more as compared to baseline value). Hemodynamic measurements were performed before dobutamine start and at the end of each step and included: arterial pressure and heart rate, diastolic shock index = (16), mottling score (17), echocardiography, arterial blood gases with lactate, and indirect calorimetry [using Carescape R860 (General Electric Healthcare, USA), to assess oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and energy expenditure] (18). Ventilatory settings, sedative and fluids infusions were kept constant throughout the dobutamine titration protocol, as well as vasopressor dose (unless poor tolerance). The dobutamine titration was discontinued in case of poor tolerance.

Echocardiography

Serial transthoracic echocardiographies were performed by trained operators (competence in advanced critical care echocardiography) with a standard procedure (19). In case of poor echogenicity, trans-esophageal echocardiography was performed (n = 6). All measures were averaged over a minimum of three cardiac cycles (five to ten in case of non-sinus rhythm).

Assessment of contractility and loading conditions

The primary outcome was the change in diastolic function, as assessed by tissue Doppler early (e') diastolic wave velocity at the lateral mitral valve annulus. LV filling pressures were also assessed using E/A and E/e ratios from pulsed-wave Doppler early (E) and late (A) and tissue Doppler early (e') wave velocities at the lateral mitral valve annulus (20, 21).

Afterload was assessed using the following indices: i) systolic arterial pressure (which is often used as a surrogate of LV afterload in clinical practice); (22) ii) systemic vascular resistance (the most commonly used measure of vascular tone) (23) iii) effective arterial elastance (to reflect the pulsatile component of peripheral load)(24) ;

LV systolic function was assessed using indices obtained by two-dimensional echocardiography (LVEF), tissue Doppler imaging (tissue Doppler peak systolic wave at the lateral mitral valve annulus), speckle tracking imaging (global longitudinal peak systolic strain of the LV, peak of systolic and early diastolic longitudinal strain rate) (2). An afterload-adjusted LVEF was assessed as recently proposed (25), using a simple nonlinear approach . Ventriculoarterial coupling was defined as the ratio of effective arterial elastance to left ventricular end-systolic elastance, which was estimated by using the single beat method of Chen et al. (26, 27).

We measured the velocity time integral in the LV outflow tract and the LVOT diameter, which allowed us to calculate LV stroke volume and cardiac index.

We also assessed i) Stroke work (SW) = 0.9*systolic arterial pressure (mmHg)*stroke volume (ml), ii) potential energy (PE) iii) LV pressure-volume area (PVA) = SW+PE iiii) Left ventricular work efficiency (which is the ratio of external work to total cardiac work during cardiac cycle) .

This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board (CPP Ile de France-V), as a component of standard care. Written and oral information about the study was given to the patients or families as per French law.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (Version 8.4.3) and IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 24). Normal distribution was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The global effect of dobutamine was assessed by the Friedman test (or mixed model analysis in case of missing data) followed by post-hoc paired Wilcoxon test with the Benjamini-Hochberg's correction. Continuous data were expressed as medians [25th−75th percentiles] or mean (± standard deviation), as appropriate, and were compared using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by pairwise Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables, expressed as percentages, were evaluated using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Two-tailed p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Using tissue Doppler early (e′) diastolic wave velocity at the lateral mitral valve annulus as the primary measure of outcome focused on diastolic function, we calculated that a sample size of at least 33 patients would have a 90% power to detect a 20% decline in that variable with dobutamine titration, considering a baseline e' of 8 cm.s−1 with a standard deviation of 2 cm.s−1 in our previous cohort (2). Twenty recordings (from twenty separate patients) were randomly selected from the study. The same sets of recordings were analyzed separately by two different ultrasonographers to assess inter-analyser reproducibility (28). The reproducibility was expressed as per the British Standards Institution coefficient (twice the standard deviation of the differences in repeated measurements) (29). This coefficient is directly related to the 95% limits of agreement. It is expressed in the measurement units and is the smallest significant difference between repeated measurements.

Results

Patient characteristics

From June 2015 to April 2019, among 57 patients screened for myocardial dysfunction during septic shock, 25 were excluded because of one of the following reasons: chronic heart failure (n = 1), already receiving an inotropic agent (levosimendan or adrenaline, n = 2), moribund state (n = 2), unavailability of trained operators or echocardiography system (n = 5), heart rate >130 bpm (n = 9), mean arterial pressure <65 mm Hg despite norepinephrine infusion (n = 1), and final diagnosis of cardiogenic shock without evidence of sepsis (n = 5). Thus, the present study comprises 32 patients (19 men and 13 women), with 28, three and one patient included in each center. Clinical characteristics, comorbidities and organ failures are shown in Table 1. Dobutamine titration was performed after a median of 1 [0-1] day of septic shock onset. The doses of 5, 10, and 15 μg/kg/min of dobutamine could be achieved in 32 (100%), 18 (56%), and 11 (34%) patients, respectively.

Table 1

| Clinical characteristics and comorbidities | Patients n = 32 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 67 [57–76] |

| Male gender | 19 (59%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23 [19–27] |

| SAPS II at ICU admission | 64 [50–76] |

| Hypertension | 4 (13%) |

| Cancer or hematological malignancy | 7 (22%) |

| Cirrhosis | 1 (3%) |

| Organ failures and hemodynamics | |

| SOFA score at ICU admission | 11 [10–14] |

| Norepinephrine treatment | 32 (100%) |

| Arterial blood lactate at admission, mmol/L | 3.9 [3–6.4] |

| Infection source Pulmonary | 18 (56%) |

| Nosocomial infection | 10 (31%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 31 (97%) |

| Tidal Volume, mL/kg predicted body weight | 6.0 [5.7–6.2] |

| Plateau pressure, cm H2O | 18 [16–22] |

| Positive end expiratory pressure, cm H2O | 8 [5–10] |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 25 (78%) |

| Fluid administration before dobutamine infusion, ml | 2750 [1,500–3,750] |

| Atrial fibrillation before dobutamine infusion | 4 (13%) |

| SOFA score at dobutamine initiation | 12 [10–14] |

| Delay between between admission and dobutamine infusion, hours | 34 [7–23] |

| Delay between shock onset and dobutamine initiation, hours | 29 [6–20] |

| Femoral central venous catheter | 21 (66%) |

| Femoral arterial catheter | 16 (50%) |

| Death in ICU | 15 (47%) |

Characteristics of patients with septic shock and myocardial dysfunction.

Data are number (percentage) or median [1st−3rd quartile].

SAPS, simplified acute physiologic score; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. Respiratory variables were collected just before dobutamine infusion.

Hemodynamics

Tables 2, 3 summarizes the hemodynamic, echocardiographic, calorimetric and arterial blood gas responses to dobutamine. Results of reproducibility of some echocardiographic variables are reported in Supplementary Table S4.

Table 2

| Dobutamine dose | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μg.kg−1.min−1 (n = 32) | 5 μg.kg−1.min−1 (n = 32) | Maximal dose§ (n = 32) | P-value§ | |

| Macrocirculation | ||||

| Dose of norepinephrine, μg.kg−1.min−1 | 1.3 [0.5;2.3] | 1.4 [0.6–2.4] | 1.4 [0.6–2.4] | 0.08 |

| Dose of norepinephrine, mg/h | 5.1 [1.6–9.0] | 5.1 [2.2–9.0] | 5.3 [2.4–9] | 0.08 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 101 [81–119] | 112 [88–122]* | 117 [95–126]* | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 73 [69–79] | 68 [59–74]* | 64 [56–74]* | <0.001 |

| Diastolic arterial pressure, mmHg | 58 [54–64] | 51 [44–60]* | 49 [44–59]* | <0.001 |

| Diastolic shock index, bpm. mmHg−1 | 1.7 [1.4- 2.0] | 2.1 [1.7-2.7]* | 2.1 [1.7-2.7]* | <0.001 |

| Afterload | ||||

| Systolic arterial pressure, mmHg | 109 [100–120] | 103 [90–114] | 100 [87–111]* | 0.03 |

| Effective arterial elastance mmHg.mL−1 | 2.6 [2.1–3.2] | 2.1 [1.6–2.9]* | 2.0 [1.5–2.7]* | <0.001 |

| Systemic vascular resistance, mmHg.L−1.min | 1,584 [1,320–2,125] | 1,087 [815–1,473]* | 999 [763–1,387]*† | <0.001 |

| Mottling score | 0 [0–2] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0.05 |

| Arterial blood gases | ||||

| pH | 7.26 [7.19–7.34] | 7.29 [7.20–7.34] | 7.29 [7.21–7.35] | 0.91 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 37 [30–44] | 37 [30–42] | 37 [31–41] | 0.99 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio, mmHg | 209 [122–324] | 209 [119–345] | 214 [119–331] | 0.56 |

| SaO2, % | 97 [94–98] | 97 [92–98] | 97 [94–98] | 0.56 |

| Lactates, mmol/L | 2.5 [1.5–3.7] | 2.2 [1.6–3.5] | 2.4 [1.6–3.5] | 0.62 |

| Oxygen metabolism | ||||

| TaO2, ml/ min−1.m−2 | 310 [270–396] | 393 [295–510]* | 438 [295–546]*† | <0.001 |

| VO2, ml/min | 243 [173–278] | 247 [193–304] | 265 [195–323] | 0.01 |

| VCO2, ml/min | 178 [134–188] | 176 [137–196] | 183 [141–206] | 0.04 |

| Respiratory quotient | 0.70 [0.66–0.74] | 0.70 [0.64–0.75] | 0.69 [0.62–0.75] | 0.66 |

| Energy expenditure, kcal/day | 1,572 [1,252–1,767] | 1,547 [1,346–1,896] | 1,602 [1,400–1,999] | 0.08 |

Hemodynamic and metabolic response during dobutamine titration in patients with shock and septic myocardial dysfunction.

Data are median [1st−3rd quartile] or mean (±standard deviation); §The maximal dose of dobutamine was 5, 10, and 15 μg.kg−1.min−1 in 32, 18, and 11 patients, respectively; §Friedman test or mixed model analysis;

*p < 0.05 as compared to baseline (0 μg.kg−1.min−1) by post-hoc Wilcoxon paired test with Benjamini-Hochberg's correction;†p < 0.05 as compared to dobutamine 5 μg.kg−1.min−1 by post hoc Wilcoxon paired test with Benjamini-Hochberg's correction; TaO2, oxygen transport, VO2 oxygen consumption determined by indirect calorimetry, VCO2: carbon dioxide production determined by indirect calorimetry; see text for definitions.

Table 3

| Dobutamine dose | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μg.kg−1.min−1 (n = 32) | 5 μg.kg−1.min−1 (n = 32) | Maximal dose§ (n = 32) | P-value§ | |

| Respiratory variation of inferior vena cava, % | 5 [0–11] | 2 [0–17] | 8 [0–20] | 0.34 |

| Diastolic function | ||||

| E/A ratio at mitral valve | 0.94 [0.70–1.13] | 0.84 [0.69–1.09] | 0.84 [0.71–1.12] | 0.15 |

| E-wave deceleration time, ms | 162 [115–233] | 151 [136–215] | 152 [128–340] | 0.96 |

| e' at lateral mitral annulus | 6.9 (±3.7) | 8.3 (±4.3)* | 8.3 (±4.5)* | 0.004 |

| E/e' ratio at lateral mitral annulus | 11.2 (±8.3) | 9.8 (±6.9)* | 9.9 (±6.6) | 0.008 |

| Peak of early diastolic longitudinal strain rate | 0.67 [0.57–0.78] | 0.87 [0.78–1.13]* | 0.93 [0.78–1.29]* | 0.005 |

| Contractility | ||||

| Global LV longitudinal peak systolic strain, % | −8.4 [−10.6 to −7.2] | −10.2 [−14.2 to −8.0] | −10.4 [−14.6 to −8.7]* | 0.01 |

| Peak of systolic longitudinal strain rate | −0.72 [−0.94 to −0.57] | −1.1 [−1.2 to −0.82]* | −1.2 [−1.4 to−0.88]* | 0.002 |

| s' at mitral lateral annulus, cm.s−1 | 8.0 [5.9–10.7] | 9.0 [7.0–12.5] | 10.0 [7.8–12.9]* | 0.002 |

| LVEF, % | 30 [25–40] | 40 [30–50]* | 45 [35–60]* | <0.001 |

| Adjusted LVEF, % | 41 [33–59] | 47 [37–63]* | 53 [42–67]* | 0.006 |

| LV end systolic elastance, mmHg.mL−1 | 1.5 [1.0–1.8] | 1.3 [1.0–1.8] | 1.3 [1.1–2.0] | 0.56 |

| RV function | ||||

| Tricuspid annular plane excursion, mm | 15 [13–17] | 17 [12–19] | 17 [14–22]* | 0.02 |

| s' at tricuspid lateral annulus, cm/s | 11.0 [8.0–12.0] | 12.8 [11.1–15.7]* | 15.0 [11.1–17.0]* | <0.001 |

| RV dilatation (RV/LV area ratio) | 0.6 [0.5–0.6] | 0.6 [0.5–0.6] | 0.6 [0.5–0.6] | 0.35 |

| Global function | ||||

| Stroke volume index, mL.m−2 | 22 [17–27] | 27 [19–30]* | 28 [19–30]* | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index, L.min−1.m−2 | 2.1 [1.7–2.7] | 2.9 [2.0–3.6]* | 3.1 [2.1–3.6]*† | <0.001 |

| Ventricular–arterial coupling | 1.8 [1.4–2.3] | 1.7 [1.1–2.4] | 1.5 [1.1–2.4] | 0.82 |

| Stroke work (mmHg mL) | 3,500 [2,915–4,908] | 3,905 [3022–5,250] | 4,010 [2,954–4,961] | 0.93 |

| Potential energy (mmHg mL) | 905 [463–1,486] | 1,239 [641–3408]* | 2,638 [1,255–5,749]*† | 0.02 |

| LV pressure-volume area (mmHg mL) | 4,528 [3,257–6,076] | 5,143 [3,975–8,566]* | 7,059 [4,450–11,103]*† | <0.001 |

| LV efficiency (%) | 82 [75-86] | 75 [67-82]* | 73 [50-73]*† | <0.001 |

Echocardiography parameters during dobutamine titration in patients with shock and septic myocardial dysfunction.

Data are median [1st−3rd quartile] or mean (±standard deviation); §The maximal dose of dobutamine was 5, 10, and 15 μg.kg−1.min−1 in 32, 18, and 11 patients, respectively; §Friedman test or mixed model analysis; *p < 0.05 as compared to baseline (0 μg.kg−1.min−1) by post-hoc Wilcoxon paired test with Benjamini-Hochberg's correction;†p < 0.05 as compared to dobutamine 5 μg.kg−1.min−1 by post hoc Wilcoxon paired test with Benjamini-Hochberg's correction; LV left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; RV, right ventricle; E, blood Doppler early diastolic wave; A, blood Doppler late diastolic wave; e', tissue Doppler early diastolic wave; s', tissue Doppler peak systolic wave.

Macrocirculation and cardiac function

Dobutamine induced a decrease in mean arterial pressure and an increase in heart rate. All contractility indices of both ventricles were increased with dobutamine (including crude LVEF, afterload-adjusted LVEF, global LV longitudinal peak systolic strain, longitudinal systolic strain rate, tissue Doppler peak systolic wave at mitral and tricuspid lateral annulus, and tricuspid annular plane excursion), while all afterload parameters were decreased (including systolic arterial pressure, effective arterial elastance, systemic vascular resistance). Dobutamine also improved diastolic function (with increased longitudinal diastolic strain rate, e' and decreased E/e' ratio at lateral mitral annulus) and global cardiac function (with increased cardiac index), but with non-significant change in ventricular–arterial coupling and decrease in LV efficiency.

Mottling and tissue hypoxia

There was a trend toward decreased mottling score with dobutamine titration, but few patients had significant mottling. Arterial blood gases and lactate levels did not change during dobutamine titration, whereas oxygen transport, oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production both increased, with a stable respiratory quotient. Energy expenditure increased with the maximal dose of dobutamine.

Clinical tolerance

During dobutamine titration, 21 (66%) patients had a poor tolerance leading to discontinuation in 15 patients at 5 μg/kg/min, four patients at 10 μg/kg/min, and two patients at 15 μg/kg/min. The reasons for discontinuation were worsening hypotension in the majority of patients (n = 18, including 14 at 5 μg/kg/min, two at 10 μg/kg/min and two at 15 μg/kg/min), severe sinus tachycardia in two patients (at 10 μg/kg/min), and worsening hypotension with new-onset atrial fibrillation in one patient (at 5 μg/kg/min).

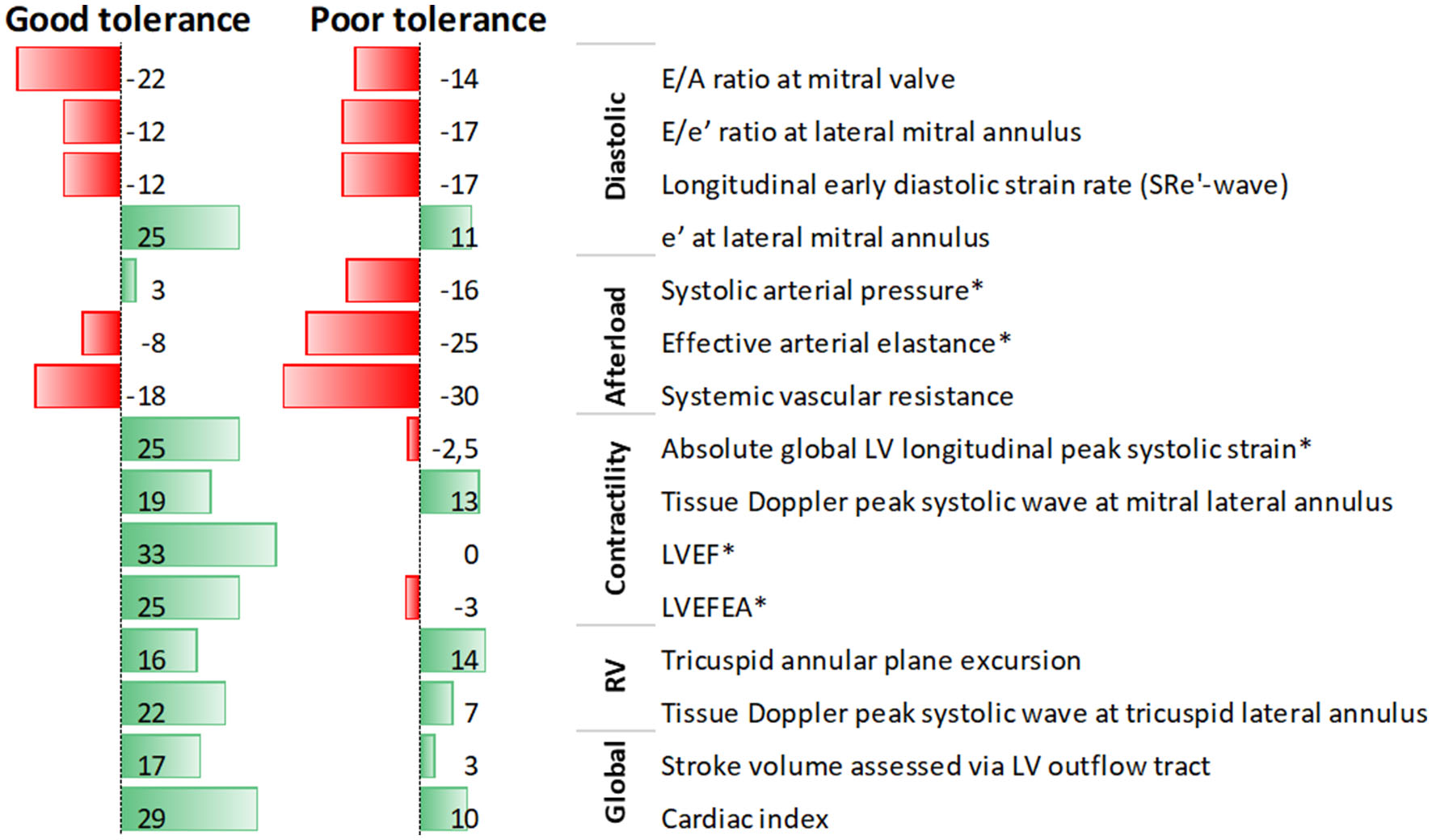

After titration, dobutamine was maintained during septic shock treatment by the attending intensivist for a median of 2.5 [1–3] days, and continuation after titration was more frequent in patients with a good tolerance to low-dose dobutamine (5 μg/kg/min) than in their counterparts with poor tolerance [14/17 (82%) vs. 7/15 (47%), p = 0.03]. Supplementary Tables S1, S2 compare patients with good or poor tolerance to low-dose dobutamine in terms of baseline characteristics or percent change of circulatory parameters after dobutamine infusion, respectively. Patients with a good tolerance to low-dose dobutamine had a greater improvement in contractility indices whereas those with poor tolerance had a more severe deterioration of afterload indices (Supplementary Table S1, Figure 1). At baseline, clinical characteristics, hemodynamics, and echocardiographic parameters did not differ between patients with good or poor tolerance to low-dose dobutamine, except for a lower arterial blood pH in patients with poor tolerance (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1

Data bars of median values of percent change in echocardiographic parameters after low-dose dobutamine infusion in septic shock patients with septic myocardial dysfunction, according to tolerance to dobutamine; *denotes significant difference between patients with good and poor tolerance.

Effect of acidosis

Patients with lesser acidosis (pH ≥ 7.28, i.e., the median value of the cohort) had more improvement in global LV longitudinal peak systolic strain, ventricular–arterial coupling, oxygen transport, and oxygen consumption with dobutamine whereas those with greater acidosis (pH <7.28) had a more severe deterioration of systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure with dobutamine (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Outcome

At day-14, patients with a good tolerance to low-dose dobutamine had more vasopressor-free days (11 [0–13] vs. 0 [0–8] days, p = 0.01) and a lower mortality [4 (24%) vs. 9 (60%), p = 0.04] than their counterparts. However, ICU mortality was not significantly different between groups [6 (35%) vs. 9 (60%), p = 0.16].

Discussion

In this study of patients having septic myocardial dysfunction and severe septic shock, we have evidenced the following findings: i) dobutamine improved echocardiographic parameters of diastolic and biventricular systolic function, while it decreased afterload; ii) nearly half and two thirds of patients had a poor tolerance to low-dose and to any dose of dobutamine, respectively; the inotropic effect was prominent in patients with good tolerance to low-dose dobutamine, while poor tolerance was enhanced by acidosis, and associated with deteriorated vasoplegic response and a worse short-term prognosis.

Systolic function

Dobutamine is a synthetic catecholamine that was developed as an inotrope for use in congestive heart failure. It consists of two composite enantiomers, which explains its mixed action on α1, α2, β1, and β2 receptors (30). Variability in LVEF during septic shock may mainly reflect the influence of loading conditions (2). Indeed, LVEF and other systolic indices reflect the ventriculo-arterial coupling between LV contractility and LV afterload. In our study, while dobutamine decreased systemic afterload, the improvement in LV contractility was not ascribable to the decrease in afterload. Indeed, among contractility parameters, global LV longitudinal peak systolic strain, longitudinal systolic strain rate, tissue Doppler peak systolic wave at the lateral mitral valve annulus (which are less dependent from loading conditions) increased after dobutamine infusion. Moreover, dobutamine induced a significant increase in the afterload-adjusted LVEF.

Diastolic function

Myocardial cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is increased by dobutamine's β-adrenoreceptors stimulation. Intracellular calcium increases secondary to elevated cAMP concentrations and could exacerbate diastolic dysfunction (31). The tachycardic response to dobutamine could also favor diastolic dysfunction. Indeed, sepsis impairs frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation, which normally maintains appropriate ventricular filling at high heart rates through the acceleration of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) activity (32). However, cAMP also mediate the effect of β-adrenergic receptor stimulation to cause myocardial relaxation (i.e., positive lusitropic effect) (33). Moreover, studies in muscle strips (34), isolated hearts (35), and intact animal (36), have demonstrated that β-adrenergic receptor stimulation accelerates myocardial relaxation. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that the net effect of dobutamine on diastolic function was an improved relaxation. These results are in accordance with those observed in patients with severe chronic heart failure (33).

Mottling and tissue hypoxia

Previous findings suggested beneficial effects of dobutamine on microcirculation (37). We only found a trend toward a reduction in mottling score, but our results may be affected by the limited sample size and the low values of mottling score at baseline in our cohort. Some patients with significant microcirculatory alterations cannot be identified by visual assessment (38). Moreover, both favorable and neutral effects of dobutamine on microcirculatory parameters have been reported (7, 37). Our results are in accordance with previous study with indirect calorimetry showing an increase in VO2 and VCO2 after dobutamine infusion, with stable respiratory quotient (39).

Dobutamine tolerance, acidosis, and outcome

In our study, dobutamine was discontinued because of worsening hypotension or tachycardia in nearly two-thirds of patients at any dose (5 to 15 μg/kg/min) and in nearly half of patients at low-dose (5 μg/kg/min). This result is in accordance with a previous monocenter study with dobutamine incremental doses (6). Patients with poor tolerance to low-dose dobutamine had a mitigated inotropic response and an enhanced vasoplegic response to dobutamine. Baseline characteristics were not different between patients with good or poor tolerance to low-dose dobutamine, except for more severe acidosis in the latter group. Acidosis has been shown to impair cardiac function. The drop in pH reduces the number of myocardial beta-adrenoreceptors (40), and decreases the affinity of catecholamine for the beta-adrenoreceptor (41). Acidosis also induce vascular smooth muscle relaxation via the opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels and vasodilatation secondary to overproduction of nitric oxide by inductible NO synthase (42, 43). Acidosis may therefore impair the inotropic response and worsen the vasoplegic response to dobutamine, altering its tolerance. The effect of acidosis correction on dobutamine response needs to be assessed.

In our study, a poor tolerance of dobutamine was associated with a worse outcome. A favorable response to dobutamine infusion (in terms of oxygen delivery to the tissues or whole body oxygen consumption) has been associated with a better outcome (44). A recent meta-analysis suggested that the combination of norepinephrine and dobutamine is associated with a reduction in mortality at day-28 in patients with septic shock and low cardiac output (45). Such results should be considered carefully since the heterogeneity of the studies included remains high. Randomized controlled trial are ongoing to assess dobutamine in septic shock patients with myocardial dysfunction and low cardiac output (46).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include its prospective and multicentre design, the careful selection of patients with septic myocardial dysfunction, the comprehensive hemodynamic phenotyping of cardiac function (with evaluation of preload, contractility and afterload with advanced tools including strain imaging).

Our study has several limitations. The sample size was rather small, we explored patients within a short period and most patients were included in one center. We cannot exclude that some patients had chronic heart failure and/or baseline diastolic dysfunction. We cannot exclude that the statistical power and/or intra or interobserver variability and/or the limited period of observation were insufficient to detect subtle differences in some variables. We cannot exclude that tolerance of dobutamine would have been better with a lower dose of dobutamine such as 2.5 μg/kg/min, especially in patients with severe acidosis. Although fluid responsiveness was assessed before starting dobutamine, we cannot exclude that some degree of hypovolemia may have worsened dobutamine tolerance (47). We could not assess PCO2 gap as a marker of cardiac output adequacy as many patients had the central venous catheter in femoral position. In our study, LV end systolic volume was not directly measured, but derived from ejection fraction and stroke volume, which may induce errors in LV efficiency assessment. Our finding of LV efficiency impairment with dobutamine warrants confirmation, as a previous small sample size study showed no effect of dobutamine on LV efficiency (48).

Conclusion

Dobutamine improved echocardiographic parameters of diastolic and biventricular systolic function, but further decreased LV afterload in human sepsis with myocardial dysfunction. Oxygen transport, oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production both increased, with a stable respiratory quotient. Dobutamine titration was poorly tolerated in a majority of patients, with worsening hypotension. Poor tolerance to low-dose dobutamine was enhanced by acidosis, mediated by worsened vasoplegic response and associated with lower vasopressor-free days and survival at day-14. These results may suggest that dobutamine should be infused at low dose, especially in patients with severe acidosis.

Funding

This trial was supported by French intensive care society (SRLF), for financial support of a fellow.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board (CPP Ile de France-V). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

KR had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. KR and AMD contributed to initial study design, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of the submitted article, critical revisions for intellectual content, and providing final approval of the version to be published. VL, LL, AB, GC, NP, FBo, and FBa contributed to study design and analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of the submitted article, critical revisions for intellectual content, and providing final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

Laurent Zieleskiewicz, Réanimation polyvalente et fédération de traumatology Département d'anesthésie-réanimation, Pôle MUSCA Hôpital Nord Marseille AP-HM.

Conflict of interest

Author VL receives advisory board fees from Amomed and grant from Leopharma, unrelated to the present study. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.951016/full#supplementary-material

- LVEF

left ventricle ejection fraction

- SAPS II

Simplified Acute Physiologic Score

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Abbreviations

References

1.

Parker MM Shelhamer JH Bacharach SL Green MV Natanson C Frederick TM et al . Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock. Ann Intern Med. (1984) 100:483–90. 10.7326/0003-4819-100-4-483

2.

Boissier F Razazi K Seemann A Bedet A Thille AW de Prost N et al . Left ventricular systolic dysfunction during septic shock: the role of loading conditions. Intensive Care Med. (2017) 43:633–42. 10.1007/s00134-017-4698-z

3.

Landesberg G Gilon D Meroz Y Georgieva M Levin PD Goodman S et al . Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. Eur Heart J. (2012) 33:895–903. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr351

4.

Evans L Rhodes A Alhazzani W Antonelli M Coopersmith CM French C et al . Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. (2021) 47:1181–247. 10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y

5.

Ospina-Tascón GA García Marin AF Echeverri GJ Bermudez WF Madriñán-Navia H Valencia JD et al . Effects of dobutamine on intestinal microvascular blood flow heterogeneity and O2 extraction during septic shock. J Appl Physiol Bethesda. (2017) 122:1406–17. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00886.2016

6.

Jellema WT Groeneveld ABJ Wesseling KH Thijs LG Westerhof N van Lieshout JJ . Heterogeneity and prediction of hemodynamic responses to dobutamine in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. (2006) 34:2392–8. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000233871.52553.CD

7.

Hernandez G Bruhn A Luengo C Regueira T Kattan E Fuentealba A et al . Effects of dobutamine on systemic, regional and microcirculatory perfusion parameters in septic shock: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Intensive Care Med. (2013) 39:1435–43. 10.1007/s00134-013-2982-0

8.

Singer M Deutschman CS Seymour CW Shankar-Hari M Annane D Bauer M et al . The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. (2016) 315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

9.

Dellinger RP Levy MM Rhodes A Annane D Gerlach H Opal SM et al . Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. (2013) 39:165–228. 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8

10.

McCABE WR JACKSON G . Gram-negative bacteremia: I. etiology and ecology. Arch Intern Med. (1962) 110(6):847–55. 10.1001/archinte.1962.03620240029006

11.

Le Gall JR Lemeshow S Saulnier F . A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. (1993) 270:2957–63. 10.1001/jama.1993.03510240069035

12.

Vincent JL de Mendonca A Cantraine F Moreno R Takala J Suter PMM et al . Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: Results of a multicenter, prospective study. Crit Care Med. (1998) 26:1793–800. 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016

13.

Michard F Boussat S Chemla D Anguel N Mercat A Lecarpentier Y et al . Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2000) 162:134–8. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9903035

14.

Vignon P Repessé X Bégot E Léger J Jacob C Bouferrache K et al . Comparison of echocardiographic indices used to predict fluid responsiveness in ventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 15 (2017) 195:1022–32. 10.1164/rccm.201604-0844OC

15.

Vincent JL Weil MH . Fluid challenge revisited. Crit Care Med. (2006) 34:1333–7. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214677.76535.A5

16.

Ospina-Tascón GA Teboul JL Hernandez G Alvarez I Sánchez-Ortiz AI Calderón-Tapia LE et al . Diastolic shock index and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock. Ann Intensive Care 16 avr. (2020) 10:41. 10.1186/s13613-020-00658-8

17.

Ait-Oufella H Lemoinne S Boelle PY Galbois A Baudel JL Lemant J et al . Mottling score predicts survival in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. (2011) 37:801–7. 10.1007/s00134-011-2163-y

18.

Panitchote A Thiangpak N Hongsprabhas P Hurst C . Energy expenditure in severe sepsis or septic shock in a Thai medical intensive care unit. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2017) 26:794–7. 10.6133/apjcn.072016.10

19.

Vieillard-Baron A Prin S Chergui K Dubourg O Jardin F . Hemodynamic instability in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2003) 168:1270–6. 10.1164/rccm.200306-816CC

20.

Nagueh SF Appleton CP Gillebert TC Marino PN Oh JK Smiseth OA et al . Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr Off Publ Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2009) 22:107–33. 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023

21.

Vieillard-Baron A Charron C Chergui K Peyrouset O Jardin F . Bedside echocardiographic evaluation of hemodynamics in sepsis: is a qualitative evaluation sufficient?Intensive Care Med. (2006) 32:1547–52. 10.1007/s00134-006-0274-7

22.

Chirinos JA Segers P . Noninvasive evaluation of left ventricular afterload: part 2: arterial pressure-flow and pressure-volume relations in humans. Hypertens Dallas Tex. (2010) 56:563–70. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.157339

23.

Greim CA Roewer N Schulte am Esch J . Assessment of changes in left ventricular wall stress from the end-systolic pressure-area product. Br J Anaesth. (1995) 75:583–7. 10.1093/bja/75.5.583

24.

Monge Garcia MI Jian Z Settels JJ Hatib F Cecconi M Pinsky MR . Reliability of effective arterial elastance using peripheral arterial pressure as surrogate for left ventricular end-systolic pressure. J Clin Monit Comput. (2019) 33:803–13. 10.1007/s10877-018-0236-y

25.

Monge García MI Jian Z Settels JJ Hunley C Cecconi M Hatib F et al . Determinants of left ventricular ejection fraction and a novel method to improve its assessment of myocardial contractility. Ann Intensive Care. (2019) 9:48. 10.1186/s13613-019-0526-7

26.

Pinsky MR . Guarracino F. How to assess ventriculoarterial coupling in sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care. (2020) 26:6. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000721

27.

Chen CH Fetics B Nevo E Rochitte CE Chiou KR Ding PA et al . Noninvasive single-beat determination of left ventricular end-systolic elastance in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2001) 38:2028–34. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01651-5

28.

Taylor BN Kuyatt CE . Guidelines for Evaluating and Expressing the Uncertainty of NIST Measurement Results NIST TN 1297: Appendix D1. Terminology. Natonal Inst Stand Technol. Available online at: https://www.nist.gov/pml/nist-technical-note-1297/nist-tn-1297-appendix-d1-terminology (accessed août 5, 2022).

29.

Bland JM Altman DG . Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet Lond Engl. (1986) 1:307–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8

30.

Ruffolo RR . The pharmacology of dobutamine. Am J Med Sci. 294:244–8. 10.1097/00000441-198710000-00005

31.

Katz AM . Cyclic adenosine monophosphate effects on the myocardium: a man who blows hot and cold with one breath. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1983) 2:143–9. 10.1016/S0735-1097(83)80387-8

32.

Joulin O Marechaux S Hassoun S Montaigne D Lancel S Neviere R . Cardiac force-frequency relationship and frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation are impaired in LPS-treated rats. Crit Care Lond Engl. (2009) 13:R14. 10.1186/cc7712

33.

Parker JD Landzberg JS Bittl JA Mirsky I Colucci WS . Effects of beta-adrenergic stimulation with dobutamine on isovolumic relaxation in the normal and failing human left ventricle. Circulation. (1991) 84:1040–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.84.3.1040

34.

Morad M Rolett EL . Relaxing effects of catecholamines on mammalian heart. J Physiol. (1972) 224:537–58. 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009912

35.

Weiss JL Frederiksen JW Weisfeldt ML . Hemodynamic determinants of the time-course of fall in canine left ventricular pressure. J Clin Invest. (1976) 58:751–60. 10.1172/JCI108522

36.

Karliner JS LeWinter MM Mahler F Engler R O'Rourke RA . Pharmacologic and hemodynamic influences on the rate of isovolumic left ventricular relaxation in the normal conscious dog. J Clin Invest. (1977) 60:511–21. 10.1172/JCI108803

37.

De Backer D Creteur J Dubois MJ Sakr Y Koch M Verdant C et al . The effects of dobutamine on microcirculatory alterations in patients with septic shock are independent of its systemic effects. Crit Care Med. (2006) 34:403–8. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000198107.61493.5A

38.

Kazune S Caica A Volceka K Suba O Rubins U Grabovskis A . Relationship of mottling score, skin microcirculatory perfusion indices and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction in patients with septic shock: an observational study. Crit Care. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6739999/. 10.1186/s13054-019-2589-0 (accessed avr 28, 2021).

39.

Schaffartzik W Sanft C Schaefer JH Spies C . Different dosages of dobutamine in septic shock patients: determining oxygen consumption with a metabolic monitor integrated in a ventilator. Intensive Care Med. (2000) 26:1740–6. 10.1007/s001340000635

40.

Marsh JD Margolis TI Kim D . Mechanism of diminished contractile response to catecholamines during acidosis. Am J Physiol janv. (1988) 254:H20–27. 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.1.H20

41.

Schotola H Toischer K Popov AF Renner A Schmitto JD Gummert J et al . Mild metabolic acidosis impairs the β-adrenergic response in isolated human failing myocardium. Crit Care Lond Engl. (2012) 16:R153. 10.1186/cc11468

42.

Kimmoun A Novy E Auchet T Ducrocq N Levy B . Hemodynamic consequences of severe lactic acidosis in shock states: from bench to bedside. Crit Care Lond Engl. (2015) 19:175. 10.1186/s13054-015-0896-7

43.

Pedoto A Caruso JE Nandi J Oler A Hoffmann SP Tassiopoulos AK et al . Acidosis stimulates nitric oxide production and lung damage in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (1999) 159:397–402. 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9802093

44.

Rhodes A Lamb FJ Malagon I Newman PJ Grounds RM Bennett ED . A prospective study of the use of a dobutamine stress test to identify outcome in patients with sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock. Crit Care Med. (1999) 27:2361–6. 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00007

45.

Cheng L Yan J Han S Chen Q Chen M Jiang H et al . Comparative efficacy of vasoactive medications in patients with septic shock: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Lond Engl. (2019) 23:168. 10.1186/s13054-019-2427-4

46.

University Hospital Limoges . Adjunctive DobutAmine in sePtic Cardiomyopathy With Tissue Hypoperfusion: a Randomized Controlled Multi-center Trial [Internet]. clinicaltrials. (2020) déc. Report No. NCT04166331. Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04166331 (accessed avr 22, 2021).

47.

Geerts BF Maas JJ Aarts LP Pinsky MR Jansen JR . Partitioning the resistances along the vascular tree: effects of dobutamine and hypovolemia in piglets with an intact circulation. J Clin Monit Comput. (2010) 24:377–84. 10.1007/s10877-010-9258-9

48.

Guarracino F Bertini P Pinsky MR . Cardiovascular determinants of resuscitation from sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Lond Engl. (2019) 23:118. 10.1186/s13054-019-2414-9

Summary

Keywords

septic shock, myocardial depression, dobutamine, mortality, echocardiography

Citation

Razazi K, Labbé V, Laine L, Bedet A, Carteaux G, de Prost N, Boissier F, Bagate F and Mekontso Dessap A (2022) Hemodynamic effects and tolerance of dobutamine for myocardial dysfunction during septic shock: An observational multicenter prospective echocardiographic study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:951016. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.951016

Received

23 May 2022

Accepted

12 August 2022

Published

09 September 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Xiaofeng Yang, Temple University, United States

Reviewed by

M. Ignacio Monge García, University Hospital of Jerez de la Frontera, Spain; Mathieu Jozwiak, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice, France

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Razazi, Labbé, Laine, Bedet, Carteaux, de Prost, Boissier, Bagate and Mekontso Dessap.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keyvan Razazi keyvan.razazi@aphp.fr

This article was submitted to Cardiovascular Therapeutics, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.