Abstract

Immunosuppressive medications are widely used to treat patients with neoplasms, autoimmune conditions and solid organ transplants. Key drug classes, namely calcineurin inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, and purine synthesis inhibitors, have direct effects on the structure and function of the heart and vascular system. In the heart, immunosuppressive agents modulate cardiac hypertrophy, mitochondrial function, and arrhythmia risk, while in vasculature, they influence vessel remodeling, circulating lipids, and blood pressure. The aim of this review is to present the preclinical and clinical literature examining the cardiovascular effects of immunosuppressive agents, with a specific focus on cyclosporine, tacrolimus, sirolimus, everolimus, mycophenolate, and azathioprine.

Introduction

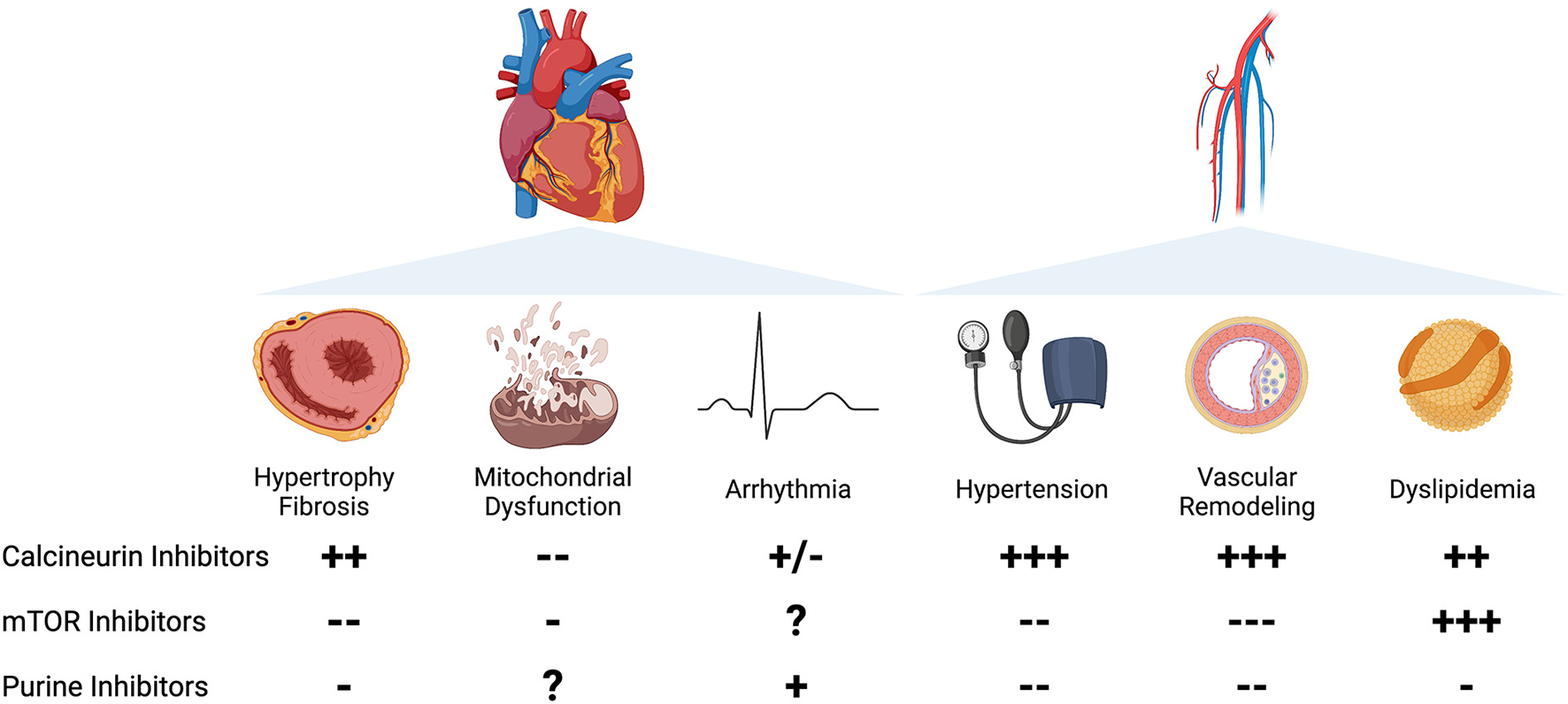

Medications that target and downregulate the immune system are utilized for the prevention and treatment of a variety of conditions, including neoplasms, autoimmune diseases, and acute rejection after solid organ transplantation (1). In a recent cohort, 2.8% of the adult population was treated with long-term immunosuppressive medications, consistent with prior self-reported estimates (2, 3). In addition to the well described increased risk of infection and malignancy in chronically immunosuppressed patients, many of these agents exhibit direct effects on the cardiovascular system including risk of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, arrhythmia, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary atherosclerosis (4). Herein, we focus on the cardiovascular effects and mechanistic underpinnings of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, and purine synthesis inhibitors (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Left Panel: Cardiac effects of immunosuppression. Column A: Calcineurin inhibitors are associated with increased hypertrophy in clinical studies, with mixed preclinical evidence. mTOR inhibitors are associated with a decrease in cardiac hypertrophy in patients and animal studies. Purine synthesis inhibitors prevent cardiac remodeling in limited evidence in preclinical studies. Column B: Calcineurin inhibitors, particularly CsA, prevent mitochondrial dysfunction and mPTP opening. mTOR inhibitors may prevent mitochondrial dysfunction in preclinical studies. The effects of purine synthesis inhibitors on mitochondrial function in the heart are unknown. Column C: Calcineurin inhibitors are associated with arrhythmia in limited clinical case reports, with mixed effects in animal studies. The effects of mTOR inhibitors on arrhythmia are unknown. Purine synthesis inhibitors, particularly azathioprine, are weakly associated with increased atrial arrhythmias in clinical case reports. Right Panel: Vascular effects of immunosuppression. Column A: Hypertension. Calcineurin inhibitors are strongly associated with an increased incidence of hypertension in preclinical and clinical studies. mTOR inhibitors and purine synthesis inhibitors have a vasodilatory effect in animal models and limited clinical studies. Column B: Vascular remodeling. Calcineurin inhibitors are strongly associated with proliferative vasculopathy and vascular inflammation. mTOR inhibitors protect against vascular damage in clinical studies and preclinical models. Purine synthesis inhibitors are associated with improvement in vascular remodeling in preclinical studies and limited clinical reports. Column C: Dyslipidemia. Calcineurin inhibitors are associated with increased total serum cholesterol and LDL. mTOR inhibitors, particularly sirolimus, are strongly associated with an increase in serum cholesterol and triglycerides. Purine synthesis inhibitors are weakly associated with improvement in serum lipids.

Hypertrophy and fibrosis

Cardiac hypertrophy is a feature of adverse cardiac remodeling that may be driven by genetic or acquired factors. Hypertrophy is frequently seen in association with diastolic dysfunction and represents an important marker for adverse remodeling (5, 6). Much of the focus on immunosuppression-induced cardiac remodeling has been on the effects on cardiac hypertrophy in native or transplanted hearts (7–9) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Agent | Species | Condition | Hypertrophy/Fibrosis | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsA | Rat, mouse | TAC | Attenuated LVH | (10–14) |

| Mouse | TAC | No effect | (7, 15, 16) | |

| Rat | SHR | No effect | (16–18) | |

| Mouse | Gαq | Attenuated LVH | (19) | |

| Rat | Cardiac fibroblasts | No effect | (20) | |

| Rat | Cardiac fibroblasts | Induced fibrosis | (21–23) | |

| Rat | Langendorff | Decreased scar | (24) | |

| Human | Transplant | Increased LVH | (25–28) | |

| Human | LVH, HCM, CAD | Attenuated LVH | (29) | |

| Human | STEMI | Decreased scar | (30) | |

| Human | STEMI | No effect | (31–34) | |

| Tacrolimus | Rat | SHR | Attenuated LVH | (35, 36) |

| Mouse | Genetic HCM | Exacerbated LVH | (37) | |

| Rat | SHR, TAC | No effect | (16) | |

| Human | Transplant | Increased LVH | (26, 27, 38–40) | |

| Sirolimus | Rat | Phenylephrine | Attenuated LVH | (41) |

| Mouse, Rat | TAC | Attenuated LVH | (42, 43) | |

| Rat | Adriamycin | Attenuated fibrosis | (44) | |

| Mouse | Leprdb diabetic | Prevented fibrosis | (45) | |

| Rat | Zucker obese | Prevented fibrosis | (46) | |

| Zucker lean | Increased fibrosis | |||

| Human | Transplant | Regressed LVH | (47–49) | |

| Everolimus | Human | Transplant | Attenuated LVH, fibrosis | (50, 51) |

| Human | Transplant | No effect on LVH | (52–55) | |

| Rat | Metabolic syndrome | Attenuated LVH, fibrosis | (56) | |

| MMF | Rat | Ischemia-reperfusion | Prevented apoptosis | (57) |

| Rat | Myocarditis | Prevented LV dysfunction | (58) |

Studies examining effects of immunosuppression on cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis.

TAC, Transverse Aortic Constriction; SHR, Spontaneously hypertensive rat; LVH, Left ventricular hypertrophy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; CAD, coronary artery disease; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Calcineurin inhibitors

Calcineurin, a calcium and calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, plays a pivotal role in cardiac hypertrophy by translocating to the nucleus and dephosphorylating NFAT, allowing it to transcribe genes to activate hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Cyclosporine (CsA) binds to cyclophilin A, forming a complex with high affinity for calcineurin, which in turn inhibits its nuclear translocation. This is hypothesized to inhibit activation of NFAT-mediated hypertrophy (59). Tacrolimus binds to FK506-binding protein (FKBP12) to inhibit calcineurin activity driving reduced NFAT-mediated transcription of hypertrophic genes.

In early animal experiments, CsA successfully prevented or attenuated cardiac hypertrophy in mice overexpressing contractile elements (10, 29), genetic predispositions to hypertrophy (19), and treatment with exogenous chemical signals promoting hypertrophy (11, 15, 60). However, these data were challenged by the failure of CsA to prevent hypertrophy in several models of hypertension or pressure overload (16, 35, 61). Tacrolimus has also yielded mixed results. In murine models of genetic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, tacrolimus exacerbated cardiac hypertrophy (37). In animal models of hypertrophy induced by phenylephrine stimulation, spontaneously hypertensive rats, or aortic banding, tacrolimus treatment had variable effects, with exacerbation or amelioration of the hypertrophic phenotype (16, 38, 61, 62).

Some hypothesized that the mixed results were driven by variability in hypertrophic signaling from genetic/sarcomeric-driven hypertrophic signaling vs. adaptive chemical or afterload-driven hypertrophy (37, 59). This hypothesis is somewhat weakened by mixed data for transverse aortic constriction rodent models.

Subsequent investigations suggested that CsA-induced effects on hypertrophic remodeling may be driven by increased fibrosis. Multiple studies have shown that CsA treatment led to increases in MMP2, MMP9, and Collagen I in dose dependent manner (20–22, 63). Rat hearts treated with CsA exhibited increased fibrosis/collagen content (64). Similar data of increased collagen deposition in response to tacrolimus treatment was observed in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac organoids treated with tacrolimus (65). The in vitro findings suggest that increased fibrosis is not a result of calcineurin-induced hypertension.

Notwithstanding some of the conflicting data in animal models, the data from humans have been fairly consistent as to the effects of CsA and tacrolimus on human hearts. Endomyocardial biopsies from heart or liver transplant patients treated with CsA showed structural distortion, increased fibrosis, and increased collagen levels (25, 26). Furthermore, patients treated with CsA and tacrolimus had hypertrophy or increased LV mass on autopsy or imaging (8, 26, 27, 39, 40). A clinical trial investigating the effect of CsA in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was initiated, but it is unclear if the study was completed and findings, if any, were not published (66).

Despite some earlier reports of amelioration of cardiac hypertrophy by CNI, there is no clear evidence in humans to corroborate this finding. Supported by in vitro and human data, a consistent signal of increased hypertrophy and fibrosis associated with CNI treatment is observed (23, 28). Cellular data highlight that the increase in LV mass may be driven primarily by CNI-induced increase in fibrosis and collagen deposition rather than cardiomyocyte remodeling.

mTOR inhibitors

mTOR inhibitors, such as sirolimus and everolimus, inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin complex I, thereby inhibiting downstream pathways driving cell growth, proliferation, and survival. There are notable differences between sirolimus and everolimus (67). Everolimus is the 40-O-(2-hydroxyethyl) derivative of sirolimus, and differs in its subcellular distribution, pharmacokinetics and binding affinity. Compared to sirolimus, everolimus has higher bioavailability and shorter half-life. Both drugs form a complex with FKBP-12, which binds mTOR. However, everolimus binding to FKBP-12 is ~3-fold weaker than that of sirolimus, leading to significant differences in inhibition of mTORC2 activation and downstream effects (68, 69). Clinically this has translated into differences in side effect profile and potency of each drug.

This class of drugs has garnered significant interest in solid organ transplantation owing to salutary effects on renal function, allograft vasculopathy and malignancy risk (70). Sirolimus has been shown to reduce cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in animal models of pressure overload, uremia, and adriamycin induced cardiomyopathy (42, 43, 71). In a rat model of myocardial infarction, everolimus improved post-infarct remodeling (72) although in the recently published CLEVER-ACS trial of patients with myocardial infarction, there everolimus treatment had no effect on myocardial remodeling (73). Cellular data suggest that attenuation of adverse cardiac remodeling by mTOR inhibitors may be related in part to reduced cardiac fibroblast proliferation and collagen secretion (65).

The favorable signal for sirolimus has been validated in human studies, which largely compared outcomes to subjects treated with CNI. Sirolimus has been associated with improvement in diastolic dysfunction and filling pressures, possibly through attenuation of fibrosis (47–49). In patients with heart transplantation, everolimus treatment was associated with less myocardial fibrosis than mycophenolate treatment by biopsy and imaging (50, 51). The data in kidney transplant patients has been more mixed with some suggesting less LV hypertrophy with the use of everolimus (74), while a number of randomized trials showed no difference in LV mass index after conversion from CsA to everolimus post-kidney transplant (52–55). The incidence of adverse cardiovascular events from these studies was mixed with the majority showing no differences in outcomes (75–77). This discordant signal may be related to the fact that kidney transplant recipients often have concomitant hypertension and activation of the renin-angiotensin system that may have already contributed to significant adverse cardiac remodeling prior to kidney transplant—making it less likely to observe differences following kidney transplantation (75, 78). Additionally, most of the studies may have been underpowered to detect differences in cardiovascular outcomes.

Purine synthesis inhibitors

Purine synthesis inhibitors block cell proliferation by preventing the synthesis of DNA and RNA during S phase of the cell-cycle. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) treatment has been shown to prevent or attenuate ischemic injury and autoimmune myocarditis in animal models, with reduced secretion of inflammatory markers such as TLR4, NFκB, BAX expression, and TNFα (57, 58). There are no human studies suggesting a link between cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis in association with MMF or azathioprine use.

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondria constitute a third of cardiomyocyte volume, and the heart, as a metabolically active organ, relies heavily on mitochondrial ATP production (79). Mitochondrial dysfunction is a feature of multiple types of cardiomyopathy, as it confers oxidative stress and changes in energetics to drive adverse cardiac remodeling. Immunosuppressive agents can exert direct effects on mitochondrial health to modulate cardiac remodeling and this has been subject of much investigation (Table 2).

Table 2

| Agent | Species | Condition | Mito function | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsA | Rat | Isolated Mito | Protected from Ca2+ overload, prevented mPTP opening | (80) |

| Rat | Hypothermia | Improved ATP levels | (81) | |

| Rat | IR injury | Prevented mito injury | (82, 83) | |

| Mouse | Mito DNA mutations | Prevented mito injury | (84) | |

| Pig, Rat | Cardioplegic arrest | Prevented mito injury | (85, 86) | |

| Pig | HFpEF | Attenuated mito dysfunction | (87) | |

| Mouse | Adriamycin | Prevented loss of mito membrane potential | (88) | |

| Feline | Endotoxemia | Normalized mito respiration | (89) | |

| Tacrolimus | Mouse | Adriamycin | Did not prevent loss of mito membrane potential | (88) |

| Feline | Endotoxemia | Normalized mito respiration | (89) | |

| Canine, Mouse | IR injury | Prevented loss of mito GSH and attenuated mito dysfunction | (90, 91) | |

| Sirolimus | Mouse | Injection | Inhibited mito respiration | (92) |

| Mouse | IR injury | Inhibited apoptosis, opened mito KATP channel | (93) |

Studies examining effects of immunosuppression on cardiac mitochondrial function.

Mito, Mitochondrial; IR, ischemia-reperfusion; HFpEF, Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Calcineurin inhibitors

Cyclophilin D is a protein in the inner mitochondrial matrix involved in opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) (94). mPTP opening results in mitochondrial calcium overload, release of cytochrome C, a process involved in apoptosis and implicated in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury (80). CsA interacts with cyclophilin D thereby preventing mPTP opening and protecting the mitochondria from calcium overload. Tacrolimus does not bind cyclophilin D and the effects of tacrolimus on mitochondrial function and mPTP opening are less defined. Multiple animal studies have sought to define the effect of both drugs on mitochondrial function.

CsA prevented mitochondrial-mediated injury and improved myocardial recovery in models of hypothermia, IR injury, and inborn errors of mitochondrial DNA polymerase (81–86, 95). In addition, CsA and/or tacrolimus have been associated with a favorable mitochondrial phenotype in the face of adriamycin treatment, hypoxia or endotoxemia (88–90).

Clinical data on the implications of these findings have been scant. In a single study of patients presenting with ST elevation myocardial infarction, CsA treatment decreased myocardial scar burden, which in combination with pre-clinical evidence provided promise for CsA as a “post-conditioning agent” during myocardial infarction (24, 30). However, follow-up studies failed to show any benefit to CsA treatment in regards to LV function, arrhythmia, or mortality (31–34). The discordance suggests that CsA protection from mitochondrial injury is largely a short term or acute benefit. No human studies to date have evaluated the effect of CNI on mitochondrial structure and function in light of associated cardiac remodeling.

mTOR inhibitors

Sirolimus has been associated with a reduction in respiration and cellular energetics in cardiomyocytes (92). This effect has been attributed to the observation that mTOR may activate AMP-activated protein kinase to regulate cellular bioenergetics (96). In a mouse model of cardiac IR injury, sirolimus inhibited apoptosis and improved cardiac performance via interaction with the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel (93) and appears to reduce ER stress and cytochrome C release (97). In brain, sirolimus enhances the distribution of CsA into mitochondria, accentuating its effects of decreasing mitochondrial metabolism, whereas everolimus appears to antagonize the effects of CsA in mitochondria to increase energy metabolism (67, 98). At therapeutically relevant concentrations, everolimus, but not sirolimus, distributes into brain mitochondria (99, 100). As cited above clinical studies have suggested a favorable effect for mTOR inhibitors on cardiac remodeling—but data examining mitochondrial function is lacking.

Purine synthesis inhibitors

There are no reports of direct effects of MMF and Azathioprine on mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes or heart tissue.

Arrhythmia

With described effects on myocardial structural remodeling and intracellular ion transporter function, immunosuppressive therapies may modulate the risk of arrhythmia. This poses significant short- and long-term risks, especially in patients with underlying structural heart disease and heart transplant recipients (Table 3).

Table 3

| Agent | Species | Condition | Arrhythmia | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsA | Rat | Injection | Sinus tachycardia, QT prolongation | (101) |

| Rat | Oxidant stressor | Failed to suppress ventricular arrhythmia | (102) | |

| Rabbit | Atrial myocyte | Prevented cardiac alternans, decreased AF | (103) | |

| Canine | Pacing-induced AF | Prevented downregulation of LT Ca2+ channel α-1c expression | (104) | |

| Canine | Chronic AV block | Prevented polymorphic ventricular tachycardia | (105) | |

| Mouse | Iron overload | Prevented arrhythmia | (106) | |

| Human | STEMI | No effect | (31–34) | |

| Human | Transplant | Case reports of increased arrhythmia | (107, 108) | |

| Tacrolimus | Guinea pig | Injection | Dose-dependent QT prolongation | (109, 110) |

| Pig, rat | Isolated myocytes | Increased Ca2+ transients, prolonged action potential | (111–114) | |

| Rat | IR injury | Decreased ventricular arrhythmias | (115) | |

| Human | Transplant | Case reports of arrhythmias | (116–118) | |

| Azathioprine | Human | Transplant | More atrial arrhythmias than MMF | (119) |

| Human | Ulcerative colitis, psoriasis | Case reports of atrial fibrillation | (120–123) |

Studies examining effects of immunosuppression on arrhythmia.

STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction AF, Atrial fibrillation; IR, Ischemia-reperfusion; AV, atrioventricular.

Calcineurin inhibitors

Calcineurin affects intracellular calcium transients in cardiomyocytes via modulation of the ryanodine receptor and activation of the NFAT pathway, which drives transcriptional changes in proteins regulating intracellular calcium (124). Calcineurin inhibitors in turn can play a role in mediating changes in calcium transients impacting the electrical phenotype of the heart.

Delineating the precise effect of CNI on calcium regulation in human cardiomyocytes has proven elusive. In some models CsA appeared to reduce sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium release and cytosolic levels of Ca2+ (106). However, other models showed that both CsA and tacrolimus result in increased Ca2+ release events and an increase in QT prolongation. A possible mechanism of QT prolongation may be an increase in the duration of Ca2+ transients due to blockade of Na2+/Ca2+ exchanger. It is possible that CsA and tacrolimus exert different electrical phenotypes owing to their differential role in mitochondrial Ca2+ regulation and mPTP opening. Nonetheless the results in animal models of both drugs have been equally mixed; in some animal models, the cellular phenotypes of CNI appeared to translate to a reduced propensity to arrhythmia (103, 105, 106), but not in other models (101, 102).

Clinically, in case reports, CsA and tacrolimus induced atrial fibrillation and tacrolimus induced QT prolongation and atrial arrhythmias (107, 116). However, neither signal was seen in clinical trials with either drug suggesting that the arrhythmic risk is low (125, 126).

mTOR inhibitors

There are no published reports of mTOR inhibitors modulating risk of arrhythmias. The recently published CLEVER-ACS trial showed no difference in atrial arrhythmias in patients treated with everolimus after myocardial infarction (73).

Purine synthesis inhibitors

Azathioprine use is associated with increased incidence of atrial arrhythmias. In a 3-year randomized controlled trial of azathioprine vs. MMF, heart transplant patients treated with azathioprine had a higher rate of atrial arrhythmias than those on MMF (119). The mechanism for this phenomenon is unknown. There are no published reports of MMF modulating arrhythmia risk.

Hypertension

Hypertension is a well described side effect of immunosuppressive medication use, particularly CNI, and is associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular events, renal dysfunction, and adverse cardiovascular remodeling (Table 4).

Table 4

| Agent | Species | Condition | Hypertension | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsA, Tacrolimus | Rat | Injection | Develop HTN prior to LVH | (101) |

| Rat | Isolated arteries | Enhanced vasoconstriction, endothelin-1 receptor activation, decrease in eNOS | (127–129) | |

| Human | Transplant | Increase in HTN after transplant, more in CsA than tacrolimus | (130–132) | |

| Sirolimus | Rat | Mineralocorticoid | Normalized systolic blood pressure | (133) |

| Bovine | Endothelial cells | Restored eNOS-mediated vasodilation | (134) | |

| Human, mouse | PAH | Alleviated hypoxia-induced exacerbation of PAH | (135) | |

| Everolimus | Human | Primary aldosteronism | Associated with improvement in blood pressure | (136) |

| Human | Transplant | Lower incidence of HTN compared to CNI | (137) | |

| Human | PAH | Improvement in pulmonary vascular resistance | (138) | |

| Human | Renal cell carcinoma | Increased incidence of HTN when used in conjunction with Lenvatinib | (139) | |

| MMF | Mouse | Systemic lupus erythematous | Lowered blood pressure | (140, 141) |

| Rat | Lead-induced HTN | Attenuated HTN | (142) | |

| Rat | Mineralocorticoid HTN | Prevented hypertension | (143, 144) | |

| Human | Psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis | Lowered blood pressure | (145) | |

| Azathioprine | Rat | Pregnancy-associated HTN | Attenuated hypertension | (146) |

| Human, Rat | PAH | Improved pulmonary vascular resistance | (147) | |

| Human | Transplant | Less likely to develop hypertension than CsA group | (148) |

Studies examining effects of immunosuppression on hypertension.

HTN, Hypertension; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Calcineurin inhibitors

CNI are known to cause hypertension, with 50–80% of patients reported to have hypertension with chronic use. CsA is associated with a higher incidence compared to tacrolimus (130). CNI are implicated in afferent arteriole vasoconstriction and activation of the renin-angiotensin system, promoting sodium retention and volume expansion (127, 149). Furthermore, CsA and tacrolimus are associated with promoting direct vasoconstriction by one or more of the following mechanisms: increased tone of vascular smooth muscle (128, 150, 151), reduced nitric oxide production (129), and activation of endothelin-1 receptor (129). In cultured murine endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, both CsA and tacrolimus were associated with production of proinflammatory cytokines and endothelial activation, with increased superoxide production and NF-kB regulated synthesis of proinflammatory factors, which were prevented by pharmacological inhibition of TLR4. This raises the possibility that a proinflammatory milieu drives chronic endothelial dysfunction, contributing to CNI-induced hypertension (152).

There is some controversy as to whether the clinical hypertrophic phenotype is related to direct myocardial effects or is in fact due an increase in the incidence of hypertension associated with CsA use. Observations that rats treated with CsA develop hypertension prior to myocardial hypertrophy (4, 101, 153–155) supported the notion that perhaps the clinical hypertrophic phenotype is purely related to CNI-induced hypertension rather than direct myocardial effects. While hypertension may be a contributor to the hypertrophic phenotype observed, multiple animal and cellular models have supported a direct effect of CNI on myocardial remodeling.

mTOR inhibitors

mTOR inhibitors have been associated with a lower risk of hypertension compared to calcineurin inhibitors when used in solid organ transplant recipients (137, 156). The difference between effects of CNI and mTOR inhibitors is likely driven by multiple mechanisms with an overall vasodilatory effect of mTOR inhibitors (157, 158). Sirolimus and everolimus appear to increase nitric oxide production preventing endothelial hyperplasia and dysfunction (133, 134). This promising anti-hypertensive profile has led to the consideration of mTOR inhibitors as a primary therapy for specialized difficult-to-treat populations with hypertension including pulmonary arterial hypertension and primary hyperaldosteronism (138, 139).

Purine synthesis inhibitors

Purine synthesis inhibitors are not associated with hypertension and may in fact have an antihypertensive effect. In comparison to patients treated with CsA after heart transplantation, those treated with azathioprine were less likely to develop hypertension (148). Lower blood pressures have been reported in patients taking MMF for psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis (145). Possible mechanisms for the favorable hypertensive profile include: lower pro-inflammatory signaling that drives endothelial dysfunction and hyperplasia, decreased circulating levels of endothelin-1, and reduced sodium reabsorption and neuro-hormonal activation leading to hypertension (142–144). Taken together, these data suggest that purine synthesis inhibitors carry a lower risk of systemic hypertension, and may in fact contribute to favorable mechanisms to reduce hypertension in pulmonary hypertension and renal dysfunction-associated hypertension.

Vascular remodeling

In addition to effects on hypertension, immunosuppressive agents may directly contribute to abnormal vascular remodeling to drive cardiovascular adverse events, independent of hypertension or dyslipidemia. Defining this risk and the contributing mechanisms for each drug is important in order to ensure appropriate follow up and identify potential actionable targets to modify the risk profile (Table 5).

Table 5

| Agent | Species | Condition | Vascular remodeling | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsA | Mouse | Endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells | Increased endothelial cell activation, cytokines | (152) |

| Rat | Isolated arteries | Increased endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, smooth muscle proliferation | (128, 159–162) | |

| Human | Transplant | Associated with proliferative coronary vasculopathy | (163–165) | |

| Tacrolimus | Human Rat | Norepinephrine Acetylcholine |

Increased endothelial toxicity, impaired smooth muscle relaxation | (166) |

| Human | Transplant | Less vasculopathy than CsA | (167–169) | |

| Sirolimus | Rat | Mineralocorticoid, allografts, shear stress | Inhibited ROS, inflammation, intimal proliferation | (133, 170, 171) |

| Pig Rat Human | Smooth muscle | Inhibited cell migration, proliferation | (172–174) | |

| Human | Transplant | Slowed coronary vasculopathy progression | (175, 176) | |

| Human | Transplant | Lowered PWV, arterial stiffness | (177, 178) | |

| Human | Coronary stenting | Prevented intimal proliferation | (179) | |

| Everolimus | Rabbit | Carotid arteries | Improved vascular inflammation, thickening | (180) |

| Mouse | LDL-receptor knockout | Prevented atherosclerosis | (181, 182) | |

| Human | PAH | Improved pulmonary vascular resistance | (138) | |

| Human | Transplant | Reduced CAV incidence/severity | (183, 184) | |

| Human | Transplant | No effect on pulse wave velocity | (75) | |

| MMF | Rat | Lead-induced HTN | Decreased inflammation, intimal thickening | (142) |

| Human | Transplant | Decrease in atherosclerosis, CAV | (119, 185, 186) | |

| Human | HUVEC + CNI | Prevented ROS production | (187) | |

| AZA | Rat | Pregnancy-associated HTN | Attenuated endothelial cell dysfunction | (146) |

| Rat | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Attenuated vasospasm, reduced endothelin-1 | (188) | |

| Mouse | Transgenic atherosclerosis | Inhibited atherosclerosis, decreased endothelial monocyte adhesion | (189) | |

| Human | HUVEC | Decreased cell proliferation | (190) |

Studies examining effects of immunosuppression on vascular remodeling.

ROS, reactive oxygen species; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; AZA, azathioprine; PWV, pulse wave velocity.

Calcineurin inhibitors

CNI, particularly tacrolimus, have been associated with increased risk of allograft vasculopathy (167–169, 191). This notable complication of transplanted hearts represents a major driver of graft dysfunction and has significant implications for quality of life and longevity of heart transplant recipients (163–165). This has been replicated in animal models using both tacrolimus and CsA with adverse remodeling features of vascular stiffness, thickening, inflammation and fibrosis noted in treated animals (159, 160). The mechanisms for these include: decreased fibrinolytic activity in vessel walls, increased oxidative stress in endothelial cells, and possibly increased intracellular calcium in vascular smooth muscle cells (161, 162, 192).

mTOR inhibitors

Both sirolimus and everolimus have been associated with a more favorable vascular profile and their clinical efficacy in reducing the rate of progression of cardiac allograft vasculopathy has led to widespread use in heart transplant recipients (175, 176, 183). In addition to reducing signaling associated with endothelial dysfunction, mTOR inhibitors have been shown to reduce vascular smooth muscle proliferation, intimal hyperplasia, and infiltration by inflammatory cells (170–173, 193, 194). Everolimus, in particular, was shown to reduce pro-inflammatory signaling by decreasing IL-9, VEGF release, and TNFα induced adhesion of endothelial cells (184). These effects have led to wide adoption of everolimus- and sirolimus-eluting stents in the treatment of coronary artery disease (179, 195, 196).

In several trials of kidney transplant patients, a switch from CsA to mTOR inhibitor was associated with stabilization or improvement in parameters of arterial stiffness, including pulse wave velocity (PWV), carotid systolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, and augmentation index (177, 178). One notable exception was a secondary analysis of the ELEVATE trial, where no difference in PWV was found with switch from CsA to everolimus, which was attributed to significant variation in baseline PWV in the study population (75).

In addition to reducing allograft vasculopathy, the anti-vascular proliferation signal conferred by mTOR inhibitors has made the drug class of substantial interest in oncology to suppress tumor neovascularization. Nonetheless, while this anti-proliferation profile offers a substantial benefit, it carries some drawbacks; Namely, both mTOR inhibitor drugs are associated with an increased incidence of lymphedema, which is thought to be driven by inhibition of lymphatic endothelial cell proliferation (197, 198). The incidence of such side effects must be considered in oncologic therapy, where drug dosage is typically higher than that used in transplant immunosuppression (199).

Purine synthesis inhibitors

Purine synthesis inhibitors appear to confer a beneficial vascular remodeling profile. MMF has been associated with reduced atherosclerosis progression and CAV in patients and animal models (119, 142, 185). Animal models point to a signal of decreased vascular oxidative stress and inflammation as the driving mechanism of that benefit (187, 200, 201). Reduced endothelial and smooth muscle proliferation in association with MMF have also been proposed as a possible mechanism, although the evidence is more limited than for mTOR inhibitors (190).

Dyslipidemia

Immunosuppressive medications are associated with dyslipidemia. Each drug class is associated with individual variations in affected lipid particles and more importantly in the conferred risk of atherosclerosis (Table 6).

Table 6

| Agent | Species | Condition | Dyslipidemia | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsA | Human | Transplant | Increased total cholesterol, LDL, decreased HDL | (202, 203) |

| Human | Transplant | Increased cholesteryl ester transfer protein, lipoprotein lipase activity, decreased lipolysis | (204, 205) | |

| Human | Transplant | Pro-oxidant effect on LDL | (206, 207) | |

| Tacrolimus | Mouse | High vs low dose | High dose developed hypercholesterolemia, low dose did not | (208) |

| Human | Transplant | Less significant increase in LDL, total cholesterol than CsA | (130, 209–213) | |

| Human | Transplant | Less pro-oxidant effect on LDL than CsA | (206, 207) | |

| Human Mouse | HUVEC, diabetic mice | Decreases oxidized LDL uptake to endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells | (214–216) | |

| Mouse | Pcsk9 knockout | Increased PCSK9 expression, leading to decreased LDL receptor expression, increased LDL | (217) | |

| Human | Transplant | Increase in cholesterol, triglycerides | (70, 218) | |

| Human | Transplant | Increased apolipoprotein C-III, lipoprotein lipase | (204, 219) | |

| Everolimus | Mouse | LDL-receptor knockout | Increased VLDL/LDL, inhibited atherosclerosis | (181, 182) |

| Human | Transplant | No additive increase in total cholesterol and triglycerides | (220) | |

| Human | Transplant | Similar dyslipidemia to sirolimus | (221) | |

| Human | Transplant | Decreased oxidized LDL | (222) | |

| Human | Transplant | No change in lipids, increase in PCSK9 | (223, 224) | |

| MMF | Rabbit | High-cholesterol diet | No effect on LDL, HDL, or triglyceride levels | (225) |

| Human | Transplant | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity unchanged with MMF | (131, 204, 226) | |

| Azathioprine | Human | Transplant | Conversion from CsA decreased total cholesterol, LDL, triglycerides, improved LDL oxidation | (227) |

| Human | Transplant | Did not alter serum lipids in comparison to MMF | (228) |

Studies examining effects of immunosuppression on dyslipidemia.

Calcineurin inhibitors

CsA use is associated with a dose-dependent increase in total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, a decrease in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and an increase in serum triglycerides (202, 203). These changes are driven by a decrease in lipoprotein lipase and an increase in activity of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (204, 229). Additionally, CsA may reduce expression of the LDL receptor, thereby impairing LDL clearance (230–232). Tacrolimus is associated with a similar, but milder, dyslipidemia profile compared to CsA (130, 209–212). CsA appears to be associated with an increase in oxidized LDL, which confers a higher risk of atherosclerosis, while the data for tacrolimus effect on LDL oxidation are mixed (206–208).

mTOR inhibitors

Sirolimus is a stronger inducer of hyperlipidemia than CNI, associated clinically with an increase in serum LDL and triglyceride levels (70, 218, 233). The mechanism remains unclear, although it may be due to a combination of reduced catabolism, an increase in the free fatty acid pool, increased hepatic production of triglycerides, and secretion of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) (204, 217). In addition, sirolimus is associated with an increase in serum PCSK9 levels, which acts as a post-transcriptional regulator of LDL receptor expression (234). Clinical data on the risk of dyslipidemia associated with everolimus has been mixed. In clinical studies, everolimus was not associated with an increased risk of dyslipidemia compared to CNI (220, 222, 223, 235–237). However, a meta-analysis comparing mTOR inhibitors to CNI adverse events has noted no difference between sirolimus and everolimus in the incidence of dyslipidemia (238). This suggests that everolimus may contribute to dyslipidemia, but at an intensity that is between CNI and sirolimus.

Interestingly, despite the increase in serum lipids, mTOR inhibitors are associated with an overall lower risk of atherosclerosis (195). Sirolimus reduces oxidized-LDL adhesion and uptake to endothelial cells, and can promote its autophagic degradation (214, 215). Additionally, sirolimus reduces intracellular lipid accumulation in vascular smooth muscle cells, and increases cholesterol efflux via increased expression of the ATP binding cassette protein ABCA1 (216). Similarly everolimus treatment in LDL receptor knockout mice, everolimus increased VLDL/LDL levels but reduced the rate of atherosclerosis. Thus, regardless of dyslipidemia profile, mTOR inhibitors appear to result in a net reduction in the rate of atherosclerosis, which may explain the overall clinical benefit observed.

Purine synthesis inhibitors

Both MMF and azathioprine appear to have a neutral effect on lipids with no significant changes observed in lipid profile in clinical studies (131, 226–228). In vitro studies suggest that MMF increases cholesterol efflux, but another study demonstrated inhibition of lipoprotein lipase activity—the opposing effects may explain the net neutral profile conferred by the drug.

Drug exposure and bioavailability

It is important to note that the bioavailability and exposure levels of the immunosuppression drugs have varied tremendously across clinic and scientific studies in the field. This may explain the differences observed between pre-clinical and clinical studies or even discrepancies between different clinical studies. Part of this variation is not simply investigator mediated, but is driven by variability in clinical practice by geographic area and changes in clinical practice over time. Early CsA trough concentrations in kidney transplant patients ranged 200–500 μg/ml, whereas in Europe, they were typically lower (100–200 μg/ml). Similarly, tacrolimus trough levels ranged 12–20 ηg/ml in the US, and lower in Europe (8–15 ηg/ml). There were also variations in sirolimus and everolimus levels when used in combination with CNI. MMF was previously prescribed at higher doses than is typically used now (2–3 g twice daily to 1 g twice daily) (12, 55, 107, 131).

Conclusions

Immunosuppressive agents exert significant effects on the heart and vasculature. Mechanistic studies point toward immunosuppression drug-specific influences on changes in cell proliferation, mitochondrial function, inflammatory cytokines, and altered calcium handling as potential mediators of these phenotypes. Calcineurin inhibitors promote cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and vascular remodeling, while mTOR inhibitors have an anti-proliferative effect with attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy and vascular remodeling despite promoting dyslipidemia. Purine synthesis inhibitor are less well studied, but may have a neutral to mildly positive effect on hypertension and vascular remodeling. These phenotypes are associated with significant morbidity in patients taking immunosuppressive medications, carrying increased risks of heart failure, cardiovascular disease, and kidney dysfunction. While preclinical studies have provided invaluable insight into mechanisms of cardiovascular remodeling, the discordance with clinical data, such as in the case of CNI and hypertrophy, highlights the importance of caution in generalizing the results of cell-based and animal models. Further translational research is needed to identify actionable targets to treat associated cardiovascular side effects of immunosuppression drugs.

Funding

NIH T32 HL09427411A1 (AE), NIH K08 HL135343 (KS), and American Heart Association and Enduring Hearts Grant # 924127/Sallam and Hollander/2022 (KS).

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AE, RD, and KS contributed to the writing and figures presented in the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

Figures were created using Biorender.com.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Goldraich LA Leitão SAT Scolari FL Marcondes-Braga FG Bonatto MG Munyal D et al . A comprehensive and contemporary review on immunosuppression therapy for heart transplantation. Curr Pharm Des. (2020) 26:3351–84. 10.2174/1381612826666200603130232

2.

Wallace BI Kenney B Malani PN Clauw DJ Nallamothu BK Waljee AK . Prevalence of immunosuppressive drug use among commercially insured US adults, 2018-2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e214920. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4920

3.

Harpaz R Dahl RM Dooling KL . Prevalence of immunosuppression among US adults. JAMA. (2016) 316:2547–8. 10.1001/jama.2016.16477

4.

Miller LW . Cardiovascular toxicities of immunosuppressive agents. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. (2002) 2:807–18. 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20902.x

5.

Levy D Garrison RJ Savage DD Kannel WB Castelli WP . Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. (1990) 322:1561–6. 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203

6.

Mottram PM Marwick TH . Assessment of diastolic function: what the general cardiologist needs to know. Heart Br Card Soc. (2005) 91:681–95. 10.1136/hrt.2003.029413

7.

Luo Z Shyu KG Gualberto A Walsh K . Calcineurin inhibitors and cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. (1998) 4:1092–3. 10.1038/2578

8.

Nakata Y Yoshibayashi M Yonemura T Uemoto S Inomata Y Tanaka K et al . Tacrolimus and myocardial hypertrophy. Transplantation. (2000) 69:1960–2. 10.1097/00007890-200005150-00039

9.

Paoletti E . mTOR inhibition and cardiovascular diseases: cardiac hypertrophy. Transplantation. (2018) 102:S41. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001691

10.

Sussman MA Lim HW Gude N Taigen T Olson EN Robbins J et al . Prevention of cardiac hypertrophy in mice by calcineurin inhibition. Science. (1998) 281:1690–3. 10.1126/science.281.5383.1690

11.

Meguro T Hong C Asai K Takagi G McKinsey TA Olson EN et al . Cyclosporine attenuates pressure-overload hypertrophy in mice while enhancing susceptibility to decompensation and heart failure. Circ Res. (1999) 84:735–40. 10.1161/01.RES.84.6.735

12.

Eto Y Yonekura K Sonoda M Arai N Sata M Sugiura S et al . Calcineurin is activated in rat hearts with physiological left ventricular hypertrophy induced by voluntary exercise training. Circulation. (2000) 101:2134–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.18.2134

13.

Lim HW De Windt LJ Steinberg L Taigen T Witt SA Kimball TR et al . Calcineurin expression, activation, and function in cardiac pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation. (2000) 101:2431–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.20.2431

14.

Hill JA Karimi M Kutschke W Davisson RL Zimmerman K Wang Z et al . Cardiac hypertrophy is not a required compensatory response to short-term pressure overload. Circulation. (2000) 101:2863–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.24.2863

15.

Ding B Price RL Borg TK Weinberg EO Halloran PF Lorell BH . Pressure overload induces severe hypertrophy in mice treated with cyclosporine, an inhibitor of calcineurin. Circ Res. (1999) 84:729–34. 10.1161/01.RES.84.6.729

16.

Zhang W Kowal RC Rusnak F Sikkink RA Olson EN Victor RG . Failure of calcineurin inhibitors to prevent pressure-overload left ventricular hypertrophy in rats. Circ Res. (1999) 84:722–8. 10.1161/01.RES.84.6.722

17.

Mervaala E Müller DN Park JK Dechend R Schmidt F Fiebeler A et al . Cyclosporin A protects against angiotensin II-induced end-organ damage in double transgenic rats harboring human renin and angiotensinogen genes. Hypertens Dallas Tex. (2000) 35:360–6. 10.1161/01.HYP.35.1.360

18.

Lassila M Finckenberg P Pere AK Krogerus L Ahonen J Vapaatalo H et al . Comparison of enalapril and valsartan in cyclosporine A-induced hypertension and nephrotoxicity in spontaneously hypertensive rats on high-sodium diet. Br J Pharmacol. (2000) 130:1339–47. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703422

19.

Mende U Kagen A Cohen A Aramburu J Schoen FJ Neer EJ . Transient cardiac expression of constitutively active Galphaq leads to hypertrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy by calcineurin-dependent and independent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1998) 95:13893–8. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13893

20.

Eleftheriades EG Ferguson AG Samarel AM . Cyclosporine A has no direct effect on collagen metabolism by cardiac fibroblasts in vitro. Circulation. (1993) 87:1368–77. 10.1161/01.CIR.87.4.1368

21.

Chi J Wang L Zhang X Fu Y Liu Y Chen W et al . Cyclosporin A induces autophagy in cardiac fibroblasts through the NRP-2/WDFY-1 axis. Biochimie. (2018) 148:55–62. 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.02.017

22.

Rezzani R Angoscini P Rodella L Bianchi R . Alterations induced by cyclosporine A in myocardial fibers and extracellular matrix in rat. Histol Histopathol. (2002) 17:761–6. 10.14670/HH-17.761

23.

Kolár F Papousek F MacNaughton C Pelouch V Milerová M Korecky B . Myocardial fibrosis and right ventricular function of heterotopically transplanted hearts in rats treated with cyclosporin. Mol Cell Biochem. (1996) 163–164:253–60. 10.1007/BF00408666

24.

Minners J van den Bos EJ Yellon DM Schwalb H Opie LH Sack MN . Dinitrophenol, cyclosporin A, and trimetazidine modulate preconditioning in the isolated rat heart: support for a mitochondrial role in cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. (2000) 47:68–73. 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00069-9

25.

Stovin PG English TA . Effects of cyclosporine on the transplanted human heart. J Heart Transplant. (1987) 6:180–5.

26.

Roberts CA Stern DL Radio SJ . Asymmetric cardiac hypertrophy at autopsy in patients who received FK506 (tacrolimus) or cyclosporine A after liver transplant. Transplantation. (2002) 74:817–21. 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00015

27.

Espino G Denney J Furlong T Fitzsimmons W Nash RA . Assessment of myocardial hypertrophy by echocardiography in adult patients receiving tacrolimus or cyclosporine therapy for prevention of acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2001) 28:1097–103. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703304

28.

Karch SB Billingham ME . Cyclosporine induced myocardial fibrosis: a unique controlled case report. J Heart Transplant. (1985) 4:210–2.

29.

Choudhary R Sastry BKS Subramanyam C . Positive correlations between serum calcineurin activity and left ventricular hypertrophy. Int J Cardiol. (2005) 105:327–31. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.04.006

30.

Piot C Croisille P Staat P Thibault H Rioufol G Mewton N et al . Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:473–81. 10.1056/NEJMoa071142

31.

Ghaffari S Kazemi B Toluey M Sepehrvand N . The effect of prethrombolytic cyclosporine-A injection on clinical outcome of acute anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Ther. (2013) 31:e34–39. 10.1111/1755-5922.12010

32.

Cung TT Morel O Cayla G Rioufol G Garcia-Dorado D Angoulvant D et al . Cyclosporine before PCI in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2015) 373:1021–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505489

33.

Ottani F Latini R Staszewsky L La VL Locuratolo N Sicuro M et al . Cyclosporine A in reperfused myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 67:365–74. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.081

34.

Chen -Scarabelli Carol Scarabelli TM . Cyclosporine a prior to primary PCI in STEMI patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 67:375–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.024

35.

Sakata Y Masuyama T Yamamoto K Nishikawa N Yamamoto H Kondo H et al . Calcineurin inhibitor attenuates left ventricular hypertrophy, leading to prevention of heart failure in hypertensive rats. Circulation. (2000) 102:2269–75. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.18.2269

36.

Shimoyama M Hayashi D Zou Y Takimoto E Mizukami M Monzen K et al . [Calcineurin inhibitor attenuates the development and induces the regression of cardiac hypertrophy in rats with salt-sensitive hypertension]. J Cardiol. (2001) 37:114–8.

37.

Fatkin D McConnell BK Mudd JO Semsarian C Moskowitz IG Schoen FJ et al . An abnormal Ca(2+) response in mutant sarcomere protein-mediated familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. (2000) 106:1351–9. 10.1172/JCI11093

38.

Kanazawa K Iwai-Takano M Kimura S Ohira T . Blood concentration of tacrolimus and age predict tacrolimus-induced left ventricular dysfunction after bone marrow transplantation in adults. J Med Ultrason. (2001) 47:97–105. 10.1007/s10396-019-00990-y

39.

Atkison P Joubert G Barron A Grant D Paradis K Seidman E et al . Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with tacrolimus in paediatric transplant patients. Lancet Lond Engl. (1995) 345:894–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90011-X

40.

Mano A Nakatani T Yahata Y Kato T Hashimoto S Wada K et al . Reversible myocardial hypertrophy induced by tacrolimus in a pediatric heart transplant recipient: case report. Transplant Proc. (2009) 41:3831–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.040

41.

Boluyt MO Zheng JS Younes A Long X O'Neill L Silverman H et al . Rapamycin Inhibits α1-Adrenergic Receptor–Stimulated Cardiac Myocyte Hypertrophy but Not Activation of Hypertrophy-Associated Genes. Circ Res. (1997) 81:176–86. 10.1161/01.RES.81.2.176

42.

Gao XM Wong G Wang B Kiriazis H Moore XL Su YD et al . Inhibition of mTOR reduces chronic pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Hypertens. (2006) 24:1663–70. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000239304.01496.83

43.

Gu J Hu W Song ZP Chen YG Zhang DD Wang CQ . Rapamycin Inhibits Cardiac Hypertrophy by Promoting Autophagy via the MEK/ERK/Beclin-1 Pathway. Front Physiol [Internet]. (2016). Available online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphys.2016.0010410.3389/fphys.2016.00104 (accessed April 28, 2022).

44.

Yu SY Liu L Li P Li J . Rapamycin inhibits the mTOR/p70S6K pathway and attenuates cardiac fibrosis in adriamycin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2013) 61:223–8. 10.1055/s-0032-1311548

45.

Reifsnyder PC Ryzhov S Flurkey K Anunciado-Koza RP Mills I Harrison DE et al . Cardioprotective effects of dietary rapamycin on adult female C57BLKS/J-Leprdb mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2018) 1418:106–17. 10.1111/nyas.13557

46.

Luck C DeMarco VG Mahmood A Gavini MP Pulakat L . Differential Regulation of Cardiac Function and Intracardiac Cytokines by Rapamycin in Healthy and Diabetic Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2017) 2017:5724046. 10.1155/2017/5724046

47.

Raichlin E Chandrasekaran K Kremers WK Frantz RP Clavell AL Pereira NL et al . Sirolimus as primary immunosuppressant reduces left ventricular mass and improves diastolic function of the cardiac allograft. Transplantation. (2008) 86:1395–400. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318189049a

48.

Alnsasra H Asleh R Oh JK Maleszewski JJ Lerman A Toya T et al . Impact of sirolimus as a primary immunosuppressant on myocardial fibrosis and diastolic function following heart transplantation. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10:e018186. 10.1161/JAHA.120.018186

49.

Kushwaha SS Raichlin E Sheinin Y Kremers WK Chandrasekaran K Brunn GJ et al . Sirolimus affects cardiomyocytes to reduce left ventricular mass in heart transplant recipients. Eur Heart J. (2008) 29:2742–50. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn407

50.

Anthony C Imran M Pouliopoulos J Emmanuel S Iliff JW Moffat KJ et al . Everolimus for the prevention of calcineurin-inhibitor-induced left ventricular hypertrophy after heart transplantation (RADTAC Study). JACC Heart Fail. (2021) 9:301–13. 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.01.007

51.

Imamura T Kinugawa K Nitta D Kinoshita O Nawata K Ono M . Everolimus attenuates myocardial hypertrophy and improves diastolic function in heart transplant recipients. Int Heart J. (2016) 57:204–10. 10.1536/ihj.15-320

52.

Krishnan A Teixeira-Pinto A Chan D Chakera A Dogra G Boudville N et al . Impact of early conversion from cyclosporin to everolimus on left ventricular mass index: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Transplant. (2017) 31:10. 10.1111/ctr.13043

53.

Murbraech K Holdaas H Massey R Undset LH Aakhus S . Cardiac response to early conversion from calcineurin inhibitor to everolimus in renal transplant recipients: an echocardiographic substudy of the randomized controlled CENTRAL trial. Transplantation. (2014) 97:184–8. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182a92728

54.

Murbraech K Massey R Undset LH Midtvedt K Holdaas H Aakhus S . Cardiac response to early conversion from calcineurin inhibitor to everolimus in renal transplant recipients–a three-yr serial echocardiographic substudy of the randomized controlled CENTRAL trial. Clin Transplant. (2015) 29:678–84. 10.1111/ctr.12565

55.

de Fijter JW Holdaas H Øyen O Sanders JS Sundar S Bemelman FJ et al . Early conversion from Calcineurin inhibitor- to Everolimus-based therapy following kidney transplantation: results of the randomized ELEVATE trial. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. (2017) 17:1853–67. 10.1111/ajt.14186

56.

Uchinaka A Yoneda M Yamada Y Murohara T Nagata K . Effects of mTOR inhibition on cardiac and adipose tissue pathology and glucose metabolism in rats with metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Res Perspect. (2017) 5:4. 10.1002/prp2.331

57.

Li T Yu J Chen R Wu J Fei J Bo Q et al . Mycophenolate mofetil attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via regulation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Pharm. (2014) 69:850–5. 10.1691/ph.2014.4598

58.

Kamiyoshi Y Takahashi M Yokoseki O Yazaki Y Hirose SI Morimoto H et al . Mycophenolate mofetil prevents the development of experimental autoimmune myocarditis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2005) 39:467–77. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.04.004

59.

Molkentin JD . Calcineurin and beyond: cardiac hypertrophic signaling. Circ Res. (2000) 87:731–8. 10.1161/01.RES.87.9.731

60.

Zhu W Zou Y Shiojima I Kudoh S Aikawa R Hayashi D et al . Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II and calcineurin play critical roles in endothelin-1-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. (2000) 275:15239–45. 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15239

61.

Zhang W . Old and new tools to dissect calcineurin's role in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. (2002) 53:294–303. 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00451-5

62.

Taigen T De Windt LJ Lim HW Molkentin JD . Targeted inhibition of calcineurin prevents agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2000) 97:1196–201. 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1196

63.

Pan B Li J Parajuli N Tian Z Wu P Lewno MT et al . The calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway mediates the activation of cardiac macroautophagy by proteasomal malfunction. Circ Res. (2020) 127:502–18. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316007

64.

Nayler WG Gu XH Casley DJ Panagiotopoulos S Liu J Mottram PL . Cyclosporine increases endothelin-1 binding site density in cardiac cell membranes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (1989) 163:1270–4. 10.1016/0006-291X(89)91115-7

65.

Sallam K Thomas D Gaddam S Lopez N Beck A Beach L et al . Modeling effects of immunosuppressive drugs on human hearts using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac organoids and single-cell RNA sequencing. Circulation. (2022) 145:1367–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054317

66.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) . Double Blind Placebo Controlled Study of Cyclosporin A in Patients With Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Caused by Sarcomeric Gene Mutations [Internet]. clinicaltrials. (2008). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00001965 (accessed May 16, 2022).

67.

Klawitter J Nashan B Christians U . Everolimus and sirolimus in transplantation-related but different. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2015) 14:1055–70. 10.1517/14740338.2015.1040388

68.

Mabasa VH Ensom MHH . The role of therapeutic monitoring of everolimus in solid organ transplantation. Ther Drug Monit. (2005) 27:666–76. 10.1097/01.ftd.0000175911.70172.2e

69.

Stenton SB Partovi N Ensom MHH . Sirolimus: the evidence for clinical pharmacokinetic monitoring. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2005) 44:769–86. 10.2165/00003088-200544080-00001

70.

Kahan BD Podbielski J Napoli KL Katz SM Meier-Kriesche HU Van Buren CT . Immunosuppressive effects and safety of a sirolimus/cyclosporine combination regimen for renal transplantation. Transplantation. (1998) 66:1040–6. 10.1097/00007890-199810270-00013

71.

Haller ST Yan Y Drummond CA Xie J Tian J Kennedy DJ et al . Rapamycin Attenuates Cardiac Fibrosis in Experimental Uremic Cardiomyopathy by Reducing Marinobufagenin Levels and Inhibiting Downstream Pro-Fibrotic Signaling. J Am Heart Assoc. (2016) 5:e004106. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004106

72.

Buss SJ Muenz S Riffel JH Malekar P Hagenmueller M Weiss CS et al . Beneficial effects of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2009) 54:2435–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.031

73.

Klingenberg R Stähli BE Heg D Denegri A Manka R Kapos I et al . Controlled-Level EVERolimus in Acute Coronary Syndrome (CLEVER-ACS)—A phase II, randomized, double-blind, multi-center, placebo-controlled trial. Am Heart J. (2022) 247:33–41. 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.01.010

74.

Pascual J . Everolimus in clinical practice—renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2006) 21:iii18–23. 10.1093/ndt/gfl300

75.

Holdaas H de Fijter JW Cruzado JM Massari P Nashan B Kanellis J et al . Cardiovascular parameters to 2 years after kidney transplantation following early switch to Everolimus without Calcineurin inhibitor therapy: an analysis of the randomized ELEVATE study. Transplantation. (2017) 101:2612–20. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001739

76.

Pipeleers L Abramowicz D Broeders N Lemoine A Peeters P Van Laecke S et al . 5-Year outcomes of the prospective and randomized CISTCERT study comparing steroid withdrawal to replacement of cyclosporine with everolimus in de novo kidney transplant patients. Transpl Int. (2021) 34:313–26. 10.1111/tri.13798

77.

van Dijk M van Roon AM Said MY Bemelman FJ Homan van der Heide JJ de Fijter HW et al . Long-term cardiovascular outcome of renal transplant recipients after early conversion to everolimus compared to calcineurin inhibition: results from the randomized controlled MECANO trial. Transpl Int Off J Eur Soc Organ Transplant. (2018) 31:1380–90. 10.1111/tri.13322

78.

Jennings DL Taber DJ . Use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors within the first eight to twelve weeks after renal transplantation. Ann Pharmacother. (2008) 42:116–20. 10.1345/aph.1K471

79.

Gustafsson AB Gottlieb RA . Heart mitochondria: gates of life and death. Cardiovasc Res. (2008) 77:334–43. 10.1093/cvr/cvm005

80.

Yarana C Sripetchwandee J Sanit J Chattipakorn S Chattipakorn N . Calcium-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction is predominantly mediated by cyclosporine A-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Arch Med Res. (2012) 43:333–8. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.06.010

81.

Rajesh KG Sasaguri S Ryoko S Maeda H . Mitochondrial permeability transition-pore inhibition enhances functional recovery after long-time hypothermic heart preservation. Transplantation. (2003) 76:1314–20. 10.1097/01.TP.0000085660.93090.79

82.

Xie JR Yu LN . Cardioprotective effects of cyclosporine A in an in vivo model of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2007) 51:909–13. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01342.x

83.

Griffiths EJ Halestrap AP . Protection by Cyclosporin A of ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage in isolated rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (1993) 25:1461–9. 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1162

84.

Mott JL Zhang D Freeman JC Mikolajczak P Chang SW Zassenhaus HP . Cardiac disease due to random mitochondrial DNA mutations is prevented by cyclosporin A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2004) 319:1210–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.104

85.

Nathan M Friehs I Choi YH Cowan DB Cao-Danh H McGowan FX et al . Cyclosporin a but not FK-506 protects against dopamine-induced apoptosis in the stunned heart. Ann Thorac Surg. (2005) 79:1620–6. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.10.030

86.

Gao L Hicks M Villanueva JE Doyle A Chew HC Qui MR et al . Cyclosporine A as a cardioprotective agent during donor heart retrieval, storage, or transportation: benefits and limitations. Transplantation. (2019) 103:1140–51. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002629

87.

Hiemstra JA Gutiérrez-Aguilar M Marshall KD McCommis KS Zgoda PJ Cruz-Rivera N et al . A new twist on an old idea part 2: cyclosporine preserves normal mitochondrial but not cardiomyocyte function in mini-swine with compensated heart failure. Physiol Rep. (2014) 2:e12050. 10.14814/phy2.12050

88.

Marechal X Montaigne D Marciniak C Marchetti P Hassoun SM Beauvillain JC et al . Doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction is attenuated by ciclosporin treatment in mice through improvements in mitochondrial bioenergetics. Clin Sci. (2011) 121:405–13. 10.1042/CS20110069

89.

Joshi MS Julian MW Huff JE Bauer JA Xia Y Crouser ED . Calcineurin regulates myocardial function during acute endotoxemia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2006) 173:999–1007. 10.1164/rccm.200411-1507OC

90.

Nishinaka Y Sugiyama S Yokota M Saito H Ozawa T . Protective effect of FK506 on ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial damage in canine heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (1993) 21:448–54. 10.1097/00005344-199303000-00015

91.

Sharp WW Fang YH Han M Zhang HJ Hong Z Banathy A et al . Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)-mediated diastolic dysfunction in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic benefits of Drp1 inhibition to reduce mitochondrial fission. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. (2014) 28:316–26. 10.1096/fj.12-226225

92.

Albawardi A Almarzooqi S Saraswathiamma D Abdul-Kader HM Souid AK Alfazari AS . The mTOR inhibitor sirolimus suppresses renal, hepatic, and cardiac tissue cellular respiration. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. (2015) 7:54–60.

93.

Khan S Salloum F Das A Xi LW Vetrovec G Cukreja R . Rapamycin confers preconditioning-like protection against ischemia–reperfusion injury in isolated mouse heart and cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2006) 41:256–64. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.014

94.

Johnson N Khan A Virji S Ward JM Crompton M . Import and processing of heart mitochondrial cyclophilin D. Eur J Biochem. (1999) 263:353–9. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00490.x

95.

Hausenloy DJ Boston-Griffiths EA Yellon DM . Cyclosporin A and cardioprotection: from investigative tool to therapeutic agent. Br J Pharmacol. (2012) 165:1235–45. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01700.x

96.

Tennant DA Durán RV Gottlieb E . Targeting metabolic transformation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2010) 10:267–77. 10.1038/nrc2817

97.

Zhu J Hua X Li D Zhang J Xia Q . Rapamycin attenuates mouse liver ischemia and reperfusion injury by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Transplant Proc. (2015) 47:1646–52. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.05.013

98.

Klawitter J Gottschalk S Hainz C Leibfritz D Christians U Serkova NJ . Immunosuppressant neurotoxicity in rat brain models: oxidative stress and cellular metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. (2010) 23:608–19. 10.1021/tx900351q

99.

Serkova N Christians U . Transplantation: toxicokinetics and mechanisms of toxicity of cyclosporine and macrolides. Curr Opin Investig Drugs Lond Engl. (2003) 4:1287–96.

100.

Serkova N Jacobsen W Niemann CU Litt L Benet LZ Leibfritz D et al . Sirolimus, but not the structurally related RAD (everolimus), enhances the negative effects of cyclosporine on mitochondrial metabolism in the rat brain. Br J Pharmacol. (2001) 133:875–85. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704142

101.

Tavares P Reis F Ribeiro CAF Teixeira F . Cardiovascular effects of cyclosporin treatment in an experimental model. Rev Port Cardiol Orgao Of Soc Port Cardiol Port J Cardiol Off J Port Soc Cardiol. (2002) 21:141–55.

102.

Biary N Xie C Kauffman J Akar FG . Biophysical properties and functional consequences of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release in intact myocardium. J Physiol. (2011) 589:5167–79. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214239

103.

Oropeza-Almazán Y Blatter LA . Mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex activation protects against calcium alternans in atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2020) 319:H873–81. 10.1152/ajpheart.00375.2020

104.

Huang Y Lu CY Yan W Gao L Chen Q Zhang YJ . [Influence of cyclosporine A on atrial L-type calcium channel alpha1c subunit in a canine model of atrial fibrillation]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. (2009) 37:112–4.

105.

Schreiner KD Kelemen K Zehelein J Becker R Senges JC Bauer A et al . Biventricular hypertrophy in dogs with chronic AV block: effects of cyclosporin A on morphology and electrophysiology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2004) 287:H2891–2898. 10.1152/ajpheart.01051.2003

106.

Gordan R Fefelova N Gwathmey JK Xie LH . Iron overload, oxidative stress and calcium mishandling in cardiomyocytes: role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Antioxidants. (2020) 9:758. 10.3390/antiox9080758

107.

Ko WJ Lin FL Wang SS Chu SH . Hypomagnesia and arrhythmia corrected by replacing cyclosporine with FK506 in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant Off Publ Int Soc Heart Transplant. (1997) 16:980–2.

108.

Mayer AD Dmitrewski J Squifflet JP Besse T Grabensee B Klein B et al . Multicenter randomized trial comparing tacrolimus (FK506) and cyclosporine in the prevention of renal allograft rejection: a report of the European Tacrolimus Multicenter Renal Study Group. Transplantation. (1997) 64:436–43. 10.1097/00007890-199708150-00012

109.

Minematsu T Ohtani H Sato H Iga T . Sustained QT prolongation induced by tacrolimus in guinea pigs. Life Sci. (1999) 65:PL197–202. 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00396-3

110.

Minematsu T Ohtani H Yamada Y Sawada Y Sato H Iga T . Quantitative relationship between myocardial concentration of tacrolimus and QT prolongation in guinea pigs: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model incorporating a site of adverse effect. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. (2001) 28:533–54.

111.

McCall E Li L Satoh H Shannon TR Blatter LA Bers DM . Effects of FK-506 on contraction and Ca2+ transients in rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. (1996) 79:1110–21. 10.1161/01.RES.79.6.1110

112.

DuBell WH Wright PA Lederer WJ Rogers TB . Effect of the immunosupressant FK506 on excitation—contraction coupling and outward K+ currents in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. (1997) 501:509–16. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.509bm.x

113.

Bell WH Gaa ST . Lederer WJ, Rogers TB. Independent inhibition of calcineurin and K+ currents by the immunosuppressant FK-506 in rat ventricle. Am J Physiol. (1998) 275:H2041–2052. 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2041

114.

Katanosaka Y Iwata Y Kobayashi Y Shibasaki F Wakabayashi S Shigekawa M . Calcineurin inhibits Na+/Ca2+ exchange in phenylephrine-treated hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:5764–72. 10.1074/jbc.M410240200

115.

Li X Bilali A Qiao R Paerhati T Yang Y . Association of the PPARγ/PI3K/Akt pathway with the cardioprotective effects of tacrolimus in myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury. Mol Med Rep. (2018) 17:6759–67.

116.

Hodak SP Moubarak JB Rodriguez I Gelfand MC Alijani MR Tracy CM et al . prolongation and near fatal cardiac arrhythmia after intravenous tacrolimus administration: a case report. Transplantation. (1998) 66:535–7. 10.1097/00007890-199808270-00021

117.

Kim BR Shin HS Jung YS Rim H . A case of tacrolimus-induced supraventricular arrhythmia after kidney transplantation. Sáo Paulo Med J Rev Paul Med. (2013) 131:205–7. 10.1590/1516-3180.2013.1313472

118.

Nishimura M Kim K Uchiyama A Fujino Y Nishimura S Taenaka N et al . Tacrolimus-induced life-threatening arrhythmia in a pediatric liver-transplant patient. Intensive Care Med. (2002) 28:1683–4. 10.1007/s00134-002-1479-z

119.

Eisen HJ Kobashigawa J Keogh A Bourge R Renlund D Mentzer R et al . Three-year results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of mycophenolate mofetil vs. azathioprine in cardiac transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant Off Publ Int Soc Heart Transplant. (2005) 24:517–25. 10.1016/j.healun.2005.02.002

120.

Cassinotti A Massari A Ferrara E Greco S Bosani M Ardizzone S et al . New onset of atrial fibrillation after introduction of azathioprine in ulcerative colitis: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2007) 63:875–8. 10.1007/s00228-007-0328-y

121.

Riccioni G Bucciarelli V Di Ilio E Scotti L Aceto A D'Orazio N et al . Recurrent atrial fibrillation in a patient with ulcerative colitis treated with azathioprine: case report and review of the literature. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. (2011) 24:247–9. 10.1177/039463201102400131

122.

Dodd HJ Tatnall FM Sarkany I . Fast atrial fibrillation induced by treatment of psoriasis with azathioprine. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. (1985) 291:706. 10.1136/bmj.291.6497.706

123.

Murphy G Fulton RA Keegan DJ . Fast atrial fibrillation induced by azathioprine. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. (1985) 291:1049–1049. 10.1136/bmj.291.6501.1049-a

124.

Saygili E Rana OR Günzel C Rackauskas G Saygili E Noor-Ebad F et al . Rate and irregularity of electrical activation during atrial fibrillation affect myocardial NGF expression via different signalling routes. Cell Signal. (2012) 24:99–105. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.007

125.

Sommerer C Suwelack B Dragun D Schenker P Hauser IA Witzke O et al . An open-label, randomized trial indicates that everolimus with tacrolimus or cyclosporine is comparable to standard immunosuppression in de novo kidney transplant patients. Kidney Int. (2019) 96:231–44. 10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.041

126.

U.S. Multicenter FK506 Liver Study Group . A comparison of tacrolimus (FK 506) and cyclosporine for immunosuppression in liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. (1994) 331:1110–5. 10.1056/NEJM199410273311702

127.

Hošková L Málek I Kautzner J Honsová E van Dokkum RPE Husková Z et al . Tacrolimus-induced hypertension and nephrotoxicity in Fawn-Hooded rats are attenuated by dual inhibition of renin–angiotensin system. Hypertens Res. (2014) 37:724–32. 10.1038/hr.2014.79

128.

Grześk E Malinowski B Wiciński M Szadujkis-Szadurska K Sinjab TA Manysiak S et al . Cyclosporine-A, but not tacrolimus significantly increases reactivity of vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Rep PR. (2016) 68:201–5. 10.1016/j.pharep.2015.08.012

129.

Tekes E Soydan G Tuncer M . The role of endothelin in FK506-induced vascular reactivity changes in rat perfused kidney. Eur J Pharmacol. (2005) 517:92–6. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.05.029

130.

Taylor DO Barr ML Radovancevic B Renlund DG Mentzer RM Smart FW et al . A randomized, multicenter comparison of tacrolimus and cyclosporine immunosuppressive regimens in cardiac transplantation: decreased hyperlipidemia and hypertension with tacrolimus. J Heart Lung Transplant Off Publ Int Soc Heart Transplant. (1999) 18:336–45. 10.1016/S1053-2498(98)00060-6

131.

Stegall MD Wachs ME Everson G Steinberg T Bilir B Shrestha R et al . Prednisone withdrawal 14 days after liver transplantation with mycophenolate: a prospective trial of cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Transplantation. (1997) 64:1755–60. 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00023

132.

Canzanello VJ Schwartz L Taler SJ Textor SC Wiesner RH Porayko MK et al . Evolution of cardiovascular risk after liver transplantation: a comparison of cyclosporine A and tacrolimus (FK506). Liver Transplant Surg Off Publ Am Assoc Study Liver Dis Int Liver Transplant Soc. (1997) 3:1–9. 10.1002/lt.500030101

133.

Temiz-Resitoglu M Guden DS Senol SP Vezir O Sucu N Kibar D et al . Pharmacological inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin attenuates deoxycorticosterone acetate salt–induced hypertension and related pathophysiology: regulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular hypertrophy in male rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2022) 79:355–67. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000001187

134.

Kim JA Jang HJ Martinez-Lemus LA Sowers JR . Activation of mTOR/p70S6 kinase by ANG II inhibits insulin-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 302:E201–208. 10.1152/ajpendo.00497.2011

135.

He Y Zuo C Jia D Bai P Kong D Chen D et al . Loss of DP1 aggravates vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension via mTORC1 signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2020) 201:1263–76. 10.1164/rccm.201911-2137OC

136.

Trinh B Burkard T . The mTOR-inhibitor everolimus reduces hypervolemia in patients with primary aldosteronism. Minerva Endocrinol. (2021) 20:1. 10.23736/S2724-6507.21.03382-0

137.

Andreassen AK Broch K Eiskjær H Karason K Gude E Mølbak D et al . Blood Pressure in De Novo Heart Transplant Recipients Treated With Everolimus Compared With a Cyclosporine-based Regimen: Results From the Randomized SCHEDULE Trial. Transplantation. (2019) 103:781–8. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002445

138.

Seyfarth HJ Hammerschmidt S Halank M Neuhaus P Wirtz HR . Everolimus in patients with severe pulmonary hypertension: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Pulm Circ. (2013) 3:632–8. 10.1086/674311

139.

Bendtsen MAF Grimm D Bauer J Wehland M Wise P Magnusson NE et al . Hypertension Caused by Lenvatinib and everolimus in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:1736. 10.3390/ijms18081736

140.

Lewis MJ D'Cruz D . Adhesion molecules, mycophenolate mofetil and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. (2005) 14 Suppl1:s17–26. 10.1177/096120330501400105

141.

Taylor EB Ryan MJ . Immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil attenuates hypertension in an experimental model of autoimmune disease. J Am Heart Assoc. (2017) 6:e005394. 10.1161/JAHA.116.005394

142.

Bravo Y Quiroz Y Ferrebuz A Vaziri ND Rodríguez-Iturbe B . Mycophenolate mofetil administration reduces renal inflammation, oxidative stress, and arterial pressure in rats with lead-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2007) 293:F616–623. 10.1152/ajprenal.00507.2006

143.

Moes AD Severs D Verdonk K van der Lubbe N Zietse R Danser AHJ et al . Mycophenolate mofetil attenuates DOCA-salt hypertension: effects on vascular tone. Front Physiol. (2018) 9:578. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00578

144.

Quiroz Y Pons H Gordon KL Rincón J Chávez M Parra G et al . Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from nitric oxide synthesis inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2001) 281:F38–47. 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F38

145.

Herrera J Ferrebuz A MacGregor EG Rodriguez-Iturbe B . Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. (2006) 17:S218–225. 10.1681/ASN.2006080918

146.

Tinsley JH Chiasson VL South S Mahajan A Mitchell BM . Immunosuppression improves blood pressure and endothelial function in a rat model of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens. (2009) 22:1107–14. 10.1038/ajh.2009.125

147.

Botros L Szulcek R Jansen SMA Kurakula K Goumans MJTH van Kuilenburg ABP et al . The effects of mercaptopurine on pulmonary vascular resistance and BMPR2 expression in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2020) 202:296–9. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0473LE

148.

Thompson ME Shapiro AP Johnsen AM Itzkoff JM Hardesty RL Griffith BP et al . The contrasting effects of cyclosporin-A and azathioprine on arterial blood pressure and renal function following cardiac transplantation. Int J Cardiol. (1986) 11:219–29. 10.1016/0167-5273(86)90181-6

149.

Ventura HO Mehra MR Stapleton DD Smart FW . Cyclosporine-induced hypertension in cardiac transplantation. Med Clin North Am. (1997) 81:1347–57. 10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70587-3

150.