Abstract

Introduction:

The manifestations of cardiac metastases are extremely variable depending on their location and extension.

Case presentation:

A 62-year-old man was admitted to the cardiac emergency department presenting with chest pain, worsening shortness of breath and palpitations. He had a history of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiotherapy, and he was not diagnosed with cardiovascular disease before. The electrocardiogram showed significant ST-segment elevations in leads II, III, and aVF. Initially, the patient was diagnosed with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A cardiac point-of-care ultrasound was performed immediately revealing two large heterogeneous masses in the left ventricular wall and the apex, which changed the diagnosis and the management strategy. There was no significant change in serial cardiac biomarkers in the setting of persistent STE. Thoracic computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance confirmed that the patient was suffering from cardiac and lung metastases.

Conclusion:

ECG findings of localized and prolonged STE without Q waves or changes in biomarkers may suggest myocardial tumor invasion, especially in the cancer setting. Cardiac point-of-care ultrasound is an effective, convenient, noninvasive imaging modality to guide real-time clinical decision-making.

Introduction

Cardiac metastases account for 95% to 99% of cardiac tumors (1, 2). The exact incidence of cardiac metastatic disease is unknown. A study of post-mortem examinations showed that the proportion of in-hospital deceased patients who had cardiac metastases was 9.1% which was highly variable depending on the types of primary tumors, from 1.0% in prostate carcinoma to 48.4% in mesothelioma (2). Clinical silence is prevalent in most cases (3). The manifestations of cardiac metastases are extremely variable depending on their location and extension (4, 5). We report a case of myocardial metastatic with ST-segment elevation (STE) on electrocardiogram (ECG) and intramyocardial masses noted on cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).

Case presentation

A 62-year-old man without cardiac history was admitted to the cardiac emergency department complaining of chest pain, worsening shortness of breath, and palpitations for 5–6 weeks. His medical history included esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) which was treated with chemoradiotherapy for 1.5 years. The treatment strategy was completed 6 months ago.

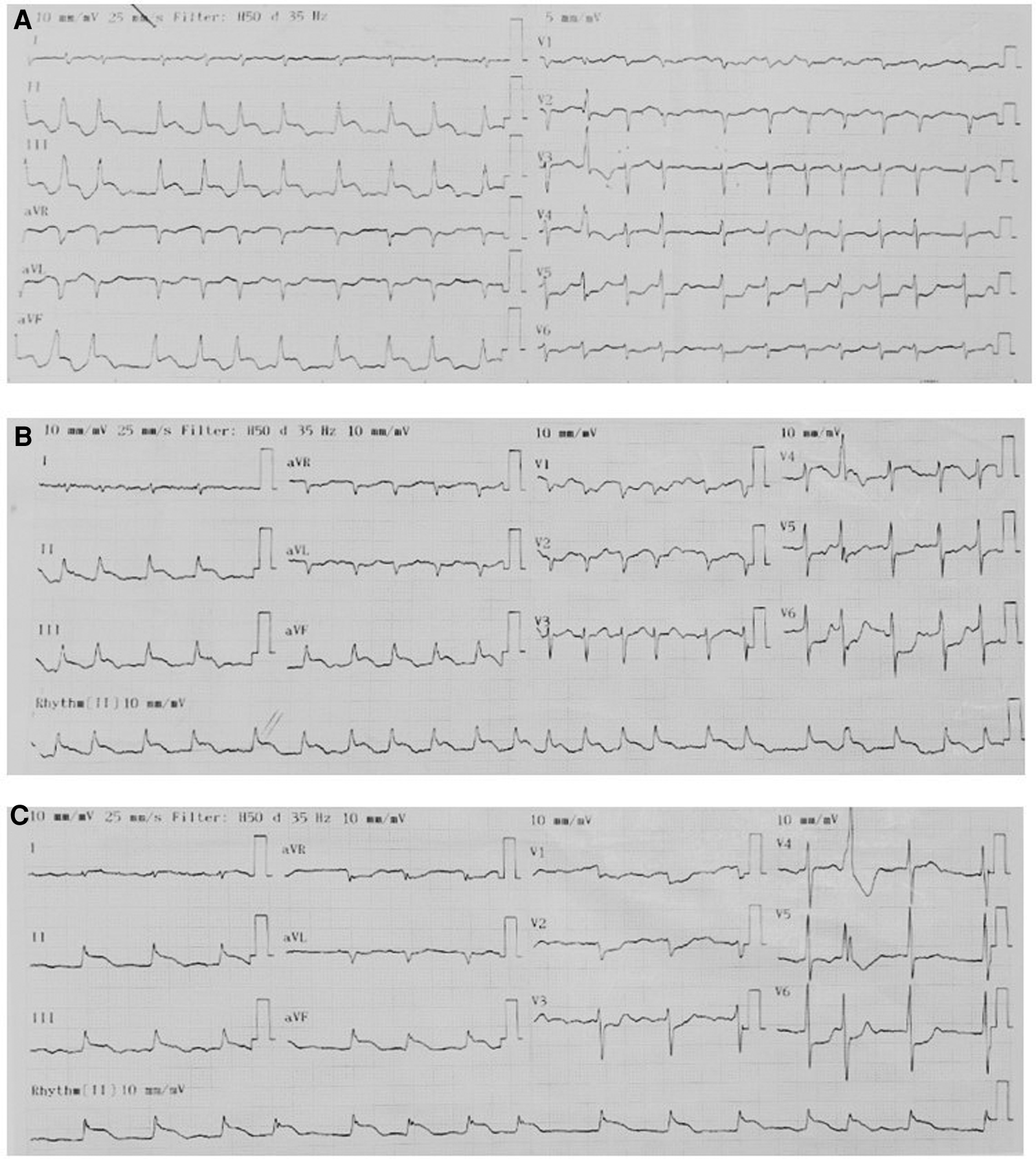

On admission, the physical examination revealed extreme frailty with a BMI of 16.2 kg/m2, heart failure signs including elevated jugular venous pressure, rales in the lungs, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and low blood pressure of 75/40 mmHg. Oxygen saturation was 89% while breathing ambient air. A 12-lead ECG showed rapid atrial fibrillation, and significant convex STE in leads II, III, and aVF with the presence of reciprocal ST depression in the precordial leads (Figure 1A). No prior ECG was available for comparison. Initially, the patient was diagnosed with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, because he had hemodynamic instability and had a history of ESCC, we decided to perform a cardiac POCUS immediately for a more comprehensive assessment before transferring the patient to the catheterization laboratory for urgent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The echocardiogram showed two large masses in the left ventricular wall and the apex. The left ventricular systolic function was low. Because of these echo findings, the PCI was deferred. Treatment was initiated with oxygen, dobutamine, furosemide, digitalis, and enoxaparin.

Figure 1

Serial ECGs. The pattern of ECGs was persistent, including atrial fibrillation, right axis deviation, poor R-wave progression, profound STE in leads II, III, and aVF with the presence of reciprocal ST depression in the precordial leads. (A) On admission. (B) 1 h later. (C) Before discharge.

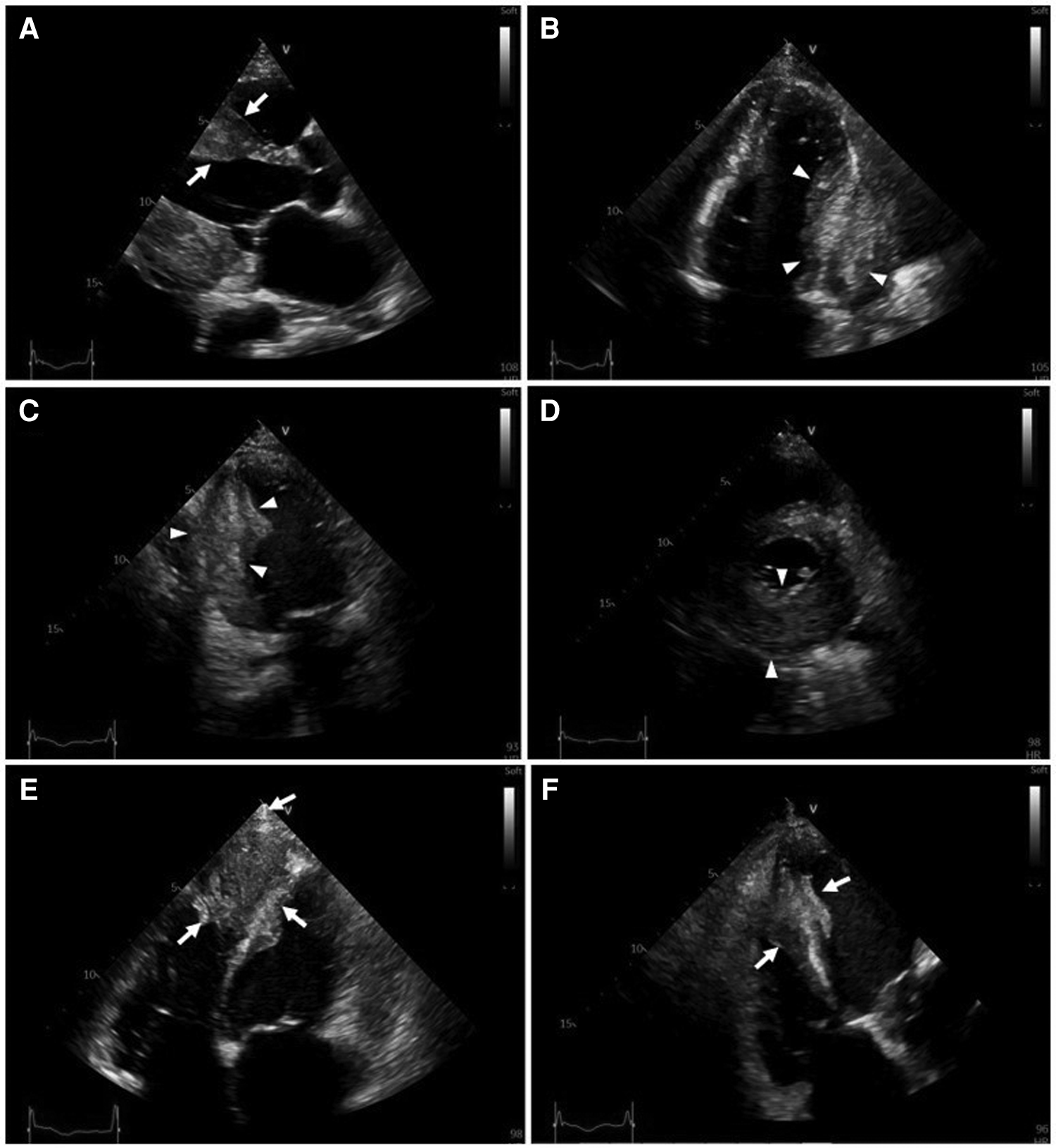

Serial hs-cTnT measurements and ECGs were obtained. A comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was performed on the following day. On serial ECGs, STE persisted and there was no development of pathological Q waves (Figures 1B, C). Laboratory studies showed that hs-cTnT stabilized at a high level: on admission 0 h 173.1 ng/L, 1 h 167.3 ng/L, 3 h 159 ng/L, on discharge 180 ng/L (<14 ng/L); elevated N-terminal pro-B-type brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) was 1391 pmol/L < 14.47 pmol/L). TTE unveiled two large heterogeneous masses, which were characterized by ill-defined borders: one involved the lateral, inferior and posterior portion of the left ventricular wall, and another involved the apex and ventricular septum portion (Figure 2). The involved ventricular walls were significantly thickened and akinetic, which did not correspond to coronary perfusion territories. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction (biplane left ventricular ejection fraction of 35%), and right ventricular systolic dysfunction (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion of 15 mm and fractional area change of 30%) were detected.

Figure 2

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography (2D-TTE). 2D-TTE reveals two large heterogeneous masses characterized by ill-defined borders: one involving the lateral, inferior and posterior portions of the left ventricular wall (white arrowheads), and another involving the apex and ventricular septum (white arrows). (A) Parasternal long-axis view. (B) Four-chamber view. (C) Two-chamber view. (D) Parasternal short-axis view at the papillary muscle level. (E) Modified four-chamber view. (F) RV-focused apical four-chamber view.

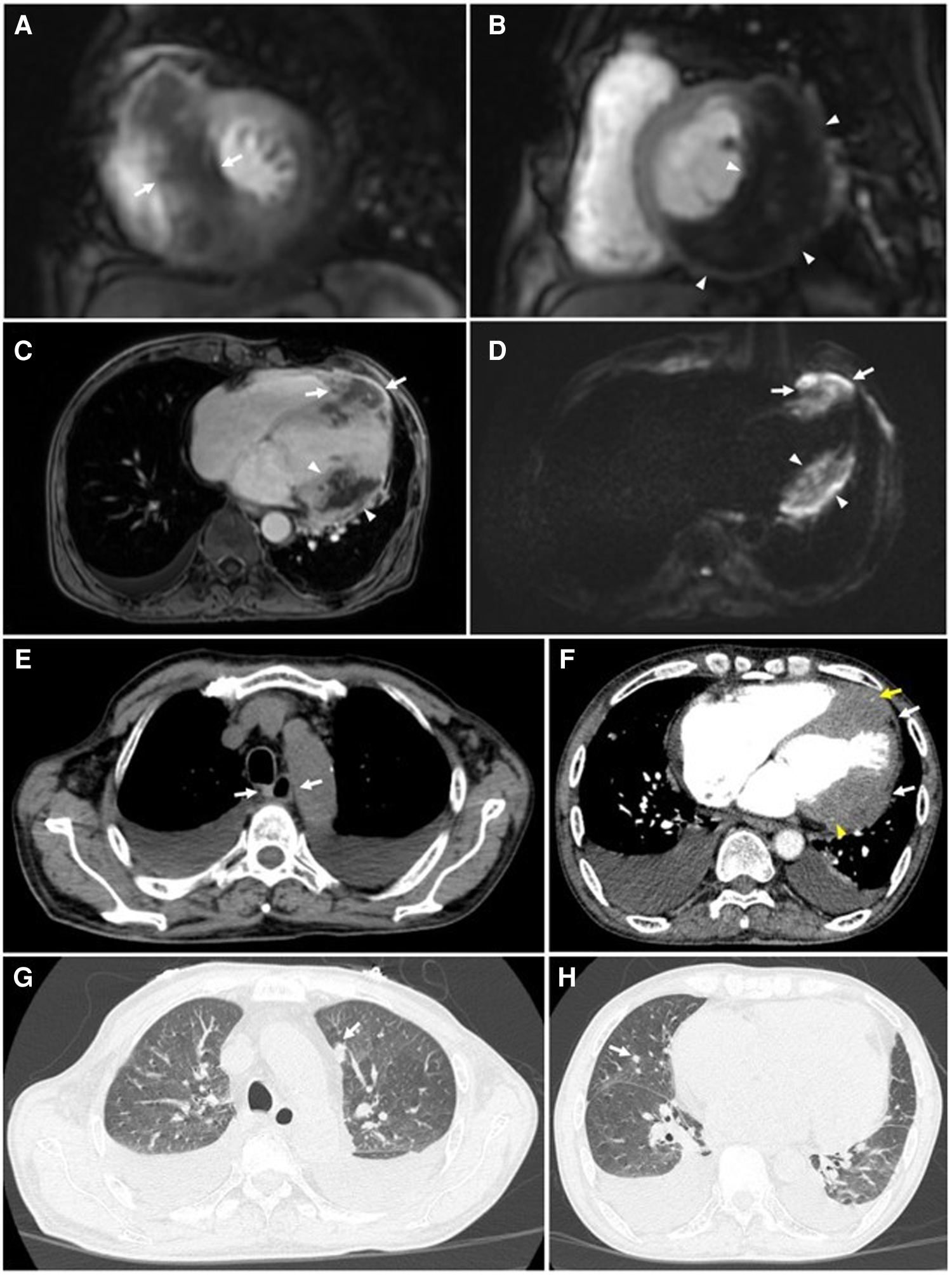

This patient was referred for a thoracic multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scan and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) for further evaluation of imaging characteristics of the cardiac masses, and other lesions.

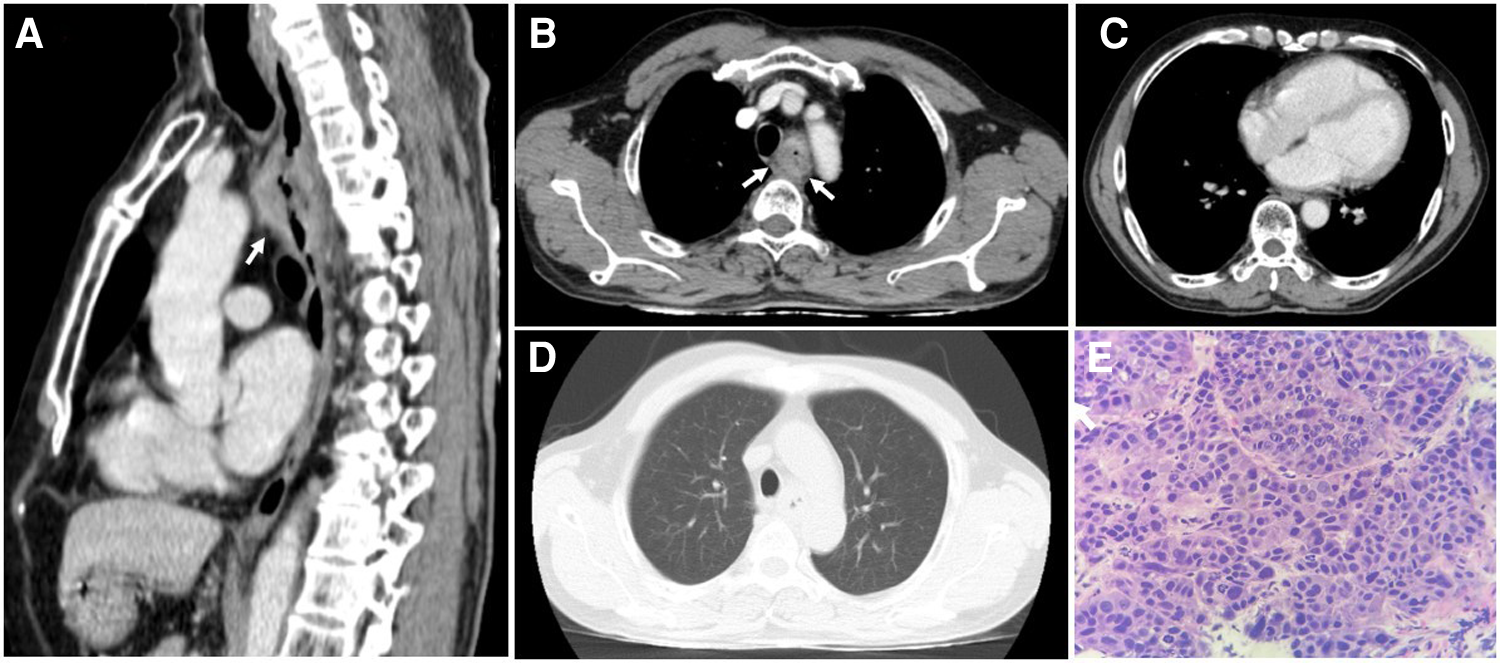

On thoracic MDCT, the mediastinal window showed infiltrative lesions causing abnormal wall thickening of the interventricular septum toward the apex, as well as of the inferior, posterior, and lateral walls of the left ventricle corresponding to the lesions observed on TTE. These lesions extended beyond the myocardium to the pericardial fat. The left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the left circumflex (LCx) artery were encased completely and compressed mildly. The adjacent pericardium was irregularly thickened (Figure 3F). These lesions were new in comparison with the pre-treatment film (Figure 4C). The ESCC was significantly diminished, and there was no longer abnormal esophageal wall thickening (Figures 4A, B; Figure 3E). On lung window, two new well-defined solid nodules in the left upper lobe and the right middle lobe were detected (Figures 3G, H) compared to before treatment (Figure 4D). On CMR, two tumors enhanced mildly on first pass perfusion images but had peripheral heterogeneous enhancement in post-contrast T1-weighted images with central necrosis. In addition, the tumors appeared to have restricted diffusion on the diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 3 A to D).

Figure 3

Cardiac magnetic resonance and thoracic computed tomography were obtained 6 months after completion of chemoradiotherapy. CMR: (A to D) Tumors of the interventricular septum (white arrows) and inferior-lateral left ventricular wall (white arrowheads) do not demonstrate enhancement on short-axis first-pass perfusion images (A & B) and axial post-contrast T1-weighted images (C) suggestive of necrosis. These lesions demonstrate restricted diffusion on the axial diffusion-weighted images (DWI) (D). (E) No abnormal thickening of the esophageal wall is seen on the mediastinal window (white arrows). (F) Tumors of the interventricular septum and inferior-lateral left ventricular wall invade the left anterior descending (LAD) artery (yellow arrows) and left circumflex (LCx) artery (yellow arrowheads), respectively. These lesions also extend to the pericardium (white arrows). (G & H) Metastatic nodules in the upper lobe of the left lung and the middle lobe of the right lung are seen on the lung window (white arrows).

Figure 4

The thoracic computed tomography and histopathology before treatment strategy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. (A & B) The sagittal and axial planes demonstrate that the upper esophageal tumor does not invade the surrounding structures (white arrows). (C) The mediastinal window demonstrates normal thickness and density of ventricular and atrial walls. (D) No parenchymal lesions are seen on the lung window. (E) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained esophageal tissue at 400 × magnification showed tumor cells that possess enlarged, hyperchromasia, coarse nucleus; visible nucleoli and large cytoplasm. The tumor cells demonstrate disarray and loss of polarity in the desmoplastic stroma.

Although the patient declined invasive coronary angiography and coronary computed tomography angiography, the unremarkable change in serial cardiac biomarkers in the setting of persistent STE strongly argued against STEMI. It was concluded that the patient suffered from cardiac and lung metastases from ESCC. The changes in ECGs were attributed to the patient's cardiac metastases. Given his disease progression and poor prognosis, the patient refused further diagnosis methods during this admission and wished to pursue palliative treatment. The patient was referred to the local hospital for palliative care. He passed away from multiple organ failure one month later.

Discussion

Cardiac metastases are usually diagnosed on imaging or autopsy incidentally (1, 2). Primary tumor can metastasize to the heart through four pathways, including hematogeneous, lymphatic, or transvenous spread, or direct invasion. Each metastatic pathway has a different target tissues (6). Pericardial involvement is the most common (69.4%), which may result in pericardial effusion and tamponade, followed by epicardial or myocardial metastases, at 34.2% and 31.8%, respectively (4). A mere 5% of cardiac metastasis involves the endocardium (4). The clinical manifestations of myocardial metastasis depend not only on the degree of metastatic infiltration but also on the location (4). Life-threatening complications include arrhythmias (complete atrioventricular block due to disruption of the cardiac conduction system by cardiac metastases, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular fibrillation, among others), and congestive heart failure (4, 5, 7). Rarely, myocardial metastases may result in cardiac rupture, cardiac tamponade, and sudden death (5). Endocardial and intracavitary lesions may occasionally lead to inflow and outflow obstruction of the heart chambers (4, 5). The coronary arteries may be injured by neoplasm-induced coronary embolism, perivascular compression of the coronary arteries, or invasion of the coronary arteries (4, 5).

Regarding ECG changes in cardiac metastasis, the most common abnormalities are ST-T changes (nonspecific ST-T changes, T wave inversion, ST-segment depression, STE) (8). Myocardial metastasis can result in conduction disturbances, atrial arrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias, which may be hard to control by antiarrhythmic medications (7–10). Low-voltage and electric alternans may indicate a pericardial effusion and tamponade (8).

STEMI is the most common cause of STE. However, STE can be found in a wide range of conditions, including normal variants, left bundle-branch block, acute pericarditis and myocarditis, electrolytes disturbances, the Brugada syndrome,arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, early repolarization, transient STE after transthoracic cardioversion, and Prinzmetal's angina (11, 12). STE in the setting of cancer can be seen in many situations, for example, myocardial metastasis, tumor emboli within a coronary artery (13), coronary artery invasion or compression by surrounding metastatic lesions (14) or cancer therapy-related cardiovascular toxicity (coronary vasospasm, accelerated atherosclerosis and plaque rupture, and coronary thrombosis and embolism (15–17).

Our patient presented with localized, persistent STE without development of pathological Q waves. Comprehensive assessment of coronary artery injuries in our patient was not possible because he refused to undergo either coronary computed tomography angiography or coronary angiography. Nevertheless, the stable hs-cTnT and ECG pattern strongly suggested the absence of STEMI.

Although STE related to myocardial metastasis is rare, it has been published in several case reports recently (18–23) and in a large series by Lestuzzi (24). Of note, evolutionary changes occurring in STEMI are not seen in patients with cardiac metastases mimicking STEMI (18, 19, 21–23). These ECGs features seem to be a sign of myocardial metastases. In patients with intracardiac, pericardial, or paracardiac neoplastic masses, 86% of patients with STE suffered from myocardial infiltration detected by two-dimensional echocardiography (24). In addition, the localization of STE reflects the location of the cardiac infiltration (18–24).

The mechanism of this phenomenon is the same as that of STE in STEMI. Malignant cardiac infiltration results in a change in the electrical properties of the myocardium, leading to the differences in the action potential between the involved and the normal myocardium. An injury current results, which manifests on the ECG as STE (21, 25).

Withholding reperfusion therapy in a patient suffering from STEMI for time consuming diagnostic testing is inadvisable as it results in a delay in therapy. Routine echocardiography before primary PCI is therefore not recommended. Emergency echocardiography is indicated in patients with cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, hemodynamic instability or suspected mechanical complications, and in cases in which the diagnosis of STEMI is uncertain (26). Clinical use of POCUS has been extensively described in medical literature since the early 2000s (27). One study found that POCUS confirmed a suspected clinical diagnosis in 50% of cases and changed the diagnosis in 23%, with a change in treatment plan in 53% (28). With the evolution of handheld ultrasound systems and the increasing evidence supporting in clinical practice, POCUS is considered as an effective and emerging tool for the frontline clinician. Recently, the use of cardiac POCUS has increased significantly and become standard in many emergency departments and critical care settings (29). The advantages of POCUS including low cost, time efficiency, ease of use, and accuracy are the backbone of its wide implementation in making diagnoses, clinical monitoring, and guiding procedures (30). In the literature, the number of cardiac POCUS publication has increased yearly. The proportion of emergency medicine and cardiology authors were 38.5% and 20.8%, respectively, decreased over the last decade, while those of anesthesiology and critical care have increased (31). In our patient cardiac POCUS changed the diagnosis and the management strategy. This case reinforces the importance of POCUS in real-time clinical decisions, especially in patients with complicated presentation.

Conclusion

Metastases to the myocardium and pericardium may mimic acute STEMI which requires timely diagnosis and emergent coronary revascularization. Investigating STEMI-mimicker in the right clinical setting can be important before committing patients to reperfusion strategies. ECG findings of localized and prolonged STE may suggest myocardial tumor invasion, especially in the cancer setting. Cardiac POCUS is a convenient, noninvasive imaging modality to guide real-time clinical decision-making.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Bach Mai Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HTTN, ANL, JNK devised the manuscript concept. AVN, ALN, HTTN belonged to patient's management team. HTTN, ANL performed cardiac point-of-care ultrasound and two-dimensional echocardiography. ANL contributed to clinical, imaging and pathological data collection. TNN, HTN interpreted the MDCT and CMR data. ANL wrote the manuscript in collaboration with HTTN, TNN, HTN. HTTN and JNK revised the manuscript. HTTN submitted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Vietnam National Heart Institute, Bach Mai hospital for providing us with the opportunity to conduct this case report.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1098154/full#supplementary-material.

References

1.

Lam KY Dickens P Chan AC . Tumors of the heart. A 20-year experience with a review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (1993) 117(10):1027–31. PMID:

2.

Butany J Leong SW Carmichael K Komeda M . A 30-year analysis of cardiac neoplasms at autopsy. Can J Cardiol. (2005) 21(8):675–80. PMID:

3.

Klatt EC Heitz DR . Cardiac metastases. Cancer. (1990) 65(6):1456–9. 10.1002/1097-0142(19900315)65:6%3C1456::AID-CNCR2820650634%3E3.0.CO;2-5

4.

Bussani R De-Giorgio F Abbate A Silvestri F . Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol. (2007) 60(1):27–34. 10.1136/jcp.2005.035105

5.

Reynen K Köckeritz U Strasser RH . Metastases to the heart. Ann Oncol. (2004) 15(3):375–81. 10.1093/annonc/mdh086

6.

Goldberg AD Blankstein R Padera RF . Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation. (2013) 128(16):1790–4. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

7.

Casella M Carbucicchio C Dello Russo A Tundo F Bartoletti S Monti L et al Radiofrequency catheter ablation of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias caused by left ventricular metastatic infiltration. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2011) 4(2):e7–10. 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.961193

8.

Cates CU Virmani R Vaughn WK Robertson RM . Electrocardiographic markers of cardiac metastasis. Am Heart J. (1986) 112(6):1297–303. 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90363-7

9.

Juan Ó Esteban E Sotillo J Alberola V . Atrial flutter and myocardial infarction-like ECG changes as manifestations of left ventricle involvement from lung carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. (2008) 10(2):125–7. 10.1007/s12094-008-0166-0

10.

Lestuzzi C Miolo G Tartuferi L Pecoraro R De Paoli A Dametto E et al Ventricular arrhythmias due to glomangiosarcoma cardiac metastases. JACC CardioOncology. (2021) 3(1):150–3. 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.11.015

11.

Wang K Asinger RW Marriott HJL . ST-Segment Elevation in conditions other than acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2003) 349(22):2128–35. 10.1056/NEJMra022580

12.

Merlo AC Pescetelli F Ameri P Porto I . Not every ST-segment elevation is a STEMI. JACC Case Rep. (2021) 3(2):283–5. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.11.019

13.

Aragon J . A rare noncardiac cause for acute myocardial infarction in a 13-year-old patient. Cardiol Rev. (2004) 12(1):31–6. 10.1097/01.crd.0000090895.81497.16

14.

Cook MA Sanchez EJ Lopez JJ Bloomfield DA . Acute myocardial infarction: a rare presentation of pancreatic carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. (1999) 28(3):271–2. 10.1097/00004836-199904000-00022

15.

Lyon AR López-Fernández T Couch LS Asteggiano R Aznar MC Bergler-Klein J et al 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European hematology association (EHA), the European society for therapeutic radiology and oncology (ESTRO) and the international cardio-oncology society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(41):4229–361. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac244

16.

Medepalli LC Mahmood TS Liberman H Medepalli AM Bagwell TW . Diagnosis and management of a patient with 5-fluorouracil-induced ST elevation and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia as a late presentation of cardiotoxicity and successful 5-fluorouracil rechallenge. Cureus. (2022) 14(10):e30489. 10.7759/cureus.30489

17.

Vošmik M Hodek M Buka D Sýkorová P Grepl J Paluska P et al Cardiotoxicity of radiation therapy in esophageal cancer. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. (2020) 25(3):318–22. 10.1016/j.rpor.2020.02.005

18.

Chen T . Persistent ST-segment elevation due to cardiac metastasis. BMJ Case Rep. (2017):bcr-2017-220621. 10.1136/bcr-2017-220621

19.

Hartman RB Clark PI Schulman P . Pronounced and prolonged ST segment elevation: a pathognomonic sign of tumor invasion of the heart. Arch Intern Med. (1982) 142(10):1917–9. 10.1001/archinte.1982.00340230165026

20.

Gard JJ Bader W Enriquez-Sarano M Frye RL Michelena HI . Uncommon cause of ST elevation. Circulation. (2011) 123(9):e259–61. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.002477

21.

Xu J Cui F Wang D Liu J Zhou R . Profound anterior ST-segment elevation in a patient with lung cancer and echocardiographic evidence of right ventricle metastasis. CASE. (2022) 6(2):59–62. 10.1016/j.case.2021.11.001

22.

Pan KL Wu LS Chung CM Chang ST Lin PC Hsu JT . Misdiagnosis: cardiac metastasis presented as a pseudo-infarction on electrocardiography. Int Heart J. (2007) 48(3):399–405. 10.1536/ihj.48.399

23.

Viscuse PV Foley TA Michelena HI . Persistent ST-segment elevation: a Pandora's Box. Circulation. (2018) 138(11):1166–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036584

24.

Lestuzzi C Nicolosi GL Biasi S Piotti P Zanuttini D . Sensitivity and specificity of electrocardiographic ST-T changes as markers of neoplastic myocardial infiltration. Chest. (1989) 95(5):980–5. 10.1378/chest.95.5.980

25.

Harris TR Copeland GD Brody DA . Progressive injury current with metastatic tumor of the heart. Am Heart J. (1965) 69(3):392–400. 10.1016/0002-8703(65)90277-2

26.

Ibanez B James S Agewall S Antunes MJ Bucciarelli-Ducci C Bueno H et al 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39(2):119–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

27.

Lee L DeCara JM . Point-of-Care ultrasound. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2020) 22(11):149. 10.1007/s11886-020-01394-y

28.

Baker DE Nolting L Brown HA . Impact of point-of-care ultrasound on the diagnosis and treatment of patients in rural Uganda. Trop Doct. (2021) 51(3):291–6. 10.1177/0049475520986425

29.

Kirkpatrick JN Grimm R Johri AM Kimura BJ Kort S Labovitz AJ et al Recommendations for echocardiography laboratories participating in cardiac point of care cardiac ultrasound (POCUS) and critical care echocardiography training: report from the American society of echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2020) 33(4):409–422.e4. 10.1016/j.echo.2020.01.008

30.

Díaz-Gómez JL Mayo PH Koenig SJ . Point-of-Care ultrasonography. Ingelfinger JR, editor. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385(17):1593–602. 10.1056/NEJMra1916062

31.

Pattock AM Kim MM Kersey CB Liu L Kirkpatrick JN Adedipe A et al Cardiac point-of-care ultrasound publication trends. Echocardiography. (2022) 39(2):240–7. 10.1111/echo.15297

Summary

Keywords

cardiac metastasis, ST-segmental elevation, point-of-care ultrasound, myocardial infarction, case report

Citation

Le AN, Nguyen AV, Nguyen TN, Kirkpatrick JN, Nguyen HT and Nguyen HTT (2023) Cardiac metastasis mimicking STEMI—impact of point-of-care ultrasound on clinical decision-making: A case report. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1098154. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1098154

Received

14 November 2022

Accepted

06 March 2023

Published

22 March 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Antonios Karanasos, Hippokration General Hospital, Greece

Reviewed by

Chiara Lestuzzi, Santa Maria degli Angeli Hospital Pordenone, Italy Goverdhan Puri, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Le, Nguyen, Nguyen, Kirkpatrick, Nguyen and Nguyen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Hoai Thi Thu Nguyen hoainguyen1973@gmail.com

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Cardiovascular Imaging, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.