Abstract

Cardiac fibrosis is an important pathological manifestation of various cardiac diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and cardiomyopathy, and it is also a key link in heart failure. Previous studies have confirmed that exercise can enhance cardiac function and improve cardiac fibrosis, but the molecular target is still unclear. In this review, we introduce the important role of miR-126 in cardiac protection, and find that it can regulate TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway, inhibit cardiac fibroblasts transdifferentiation, and reduce the production of collagen fibers. Recent studies have shown that exosomes secreted by cells can play a specific role through intercellular communication through the microRNAs carried by exosomes. Cardiac endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes (EPC-Exos) carry miR-126, and exercise training can not only enhance the release of exosomes, but also up-regulate the expression of miR-126. Therefore, through derivation and analysis, it is believed that exercise can inhibit TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway by up-regulating the expression of miR-126 in EPC-Exos, thereby weakening the transdifferentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. This review summarizes the specific pathways of exercise to improve cardiac fibrosis by regulating exosomes, which provides new ideas for exercise to promote cardiovascular health.

1 Introduction

According to the “Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China 2022”, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among Chinese residents. Approximately 330 million individuals are afflicted with cardiovascular diseases, wherein hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia emerge as primary etiological factors (1). In recent years, the incidence, hospitalization rate and mortality of cardiac fibrosis in diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease and cardiomyopathy have shown an upward trend, causing tremendous pain and economic burden to patients and their families. Therefore, analyzing the pathological mechanism of cardiac fibrosis and exploring safe and effective prevention and treatment strategies are important research topics in the field of cardiovascular medicine.

Research indicates that exercise can augment cardiac function and enhance the quality of life for patients with cardiovascular disease (1), however, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. microRNAs have been implicated in crucial processes such as cardiomyocyte differentiation and transcription, playing a pivotal role in the regulation of cardiovascular disease (2, 3), notably, miR-126, miR-29, miR-24, and miR-21 exhibit close associations with cardiac fibrosis (4–7). Recent research indicates that physical exercise can enhance the release of exosomes and modulate the expression of miR-126 (8). We hypothesize that this phenomenon may be attributed to the potential of exercise in ameliorating cardiac fibrosis. This article systematically reviews the existing literature and summarizes the specific role of exosome-mediated microRNA-126 in the process of cardiac fibrosis. It also highlights the impact of exercise on the release of exosomes and the regulation of microRNA-126 expression. By synthesizing existing research findings, we hope to gain a deeper understanding of the specific molecular mechanisms underlying the improvement of cardiac fibrosis by exercise, thereby providing a more scientific theoretical basis and new ideas for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

2 Current status of treatment for cardiac fibrosis

Cardiac fibrosis denotes a pathological response characterized by persistent myocardial tissue damage, which triggers an excessive proliferation of fibroblasts, secretion of substantial amounts of collagen fibers, and subsequent excessive deposition (9). Furthermore, it can result in diminished cardiac compliance, necrosis of cardiomyocytes, and cardiac remodeling, ultimately leading to impaired myocardial contractility and cardiac dysfunction. These pathological changes serve as crucial links between hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and the development of heart failure (10–12). Cardiac fibroblasts represent the predominant population of mesenchymal cells within the cardiac tissue. Activation of profibrotic signaling pathways can induce their differentiation into myofibroblasts, leading to enhanced secretion of collagen fibers and subsequent scar formation. Notably, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) serves as a reliable marker for discerning activated cardiac fibroblasts (13, 14). The studies suggest that TGF-β in the cardiac interstitium performs multiple functions, including the promotion of α-SMA transcription in fibroblasts through activation of Smad3 signaling (15). Additionally, it facilitates fibroblasts transdifferentiation and regulates the ratio of Col1 to Col3, thereby promoting the initiation and progression of cardiac fibrosis (16).

Cardiac fibrosis is regulated by a variety of factors, so there are different antifibrotic drugs for different regulatory factors in clinical practice. The overactivation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is the main mechanism leading to heart failure and cardiac fibrosis. Therefore, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and aldosterone receptor antagonists have inhibitory effects on cardiac fibrosis. In addition, calcium ions promote fibroblasts proliferation, on this basis, calcium ion blockers are widely used in the treatment of fibrosis. Furthermore, pirfenidone is often used in clinical practice, and in addition to its antioxidant properties, it can also alleviate cardiac fibrosis by down-regulating TGF-β1 expression (17). Additionally, α1A-adrenergic receptor blockers have demonstrated the ability to attenuate the expression of TGF-β, p-Smad2, and p-Smad3 while effectively inhibiting excessive activation of cardiac fibroblasts (18). Furthermore, anti-inflammatory treatment has the potential to ameliorate cardiac fibrosis. For instance, colchicine exhibits anti-inflammatory properties while concurrently inhibiting fibrotic processes (19). The administration of Candesartan leads to a reduction in fibrosis through the downregulation of type III procollagen-N-peptide levels and inflammatory marker levels (20). In fact, some traditional Chinese medicines have also been shown to reduce the production of collagen fibers, such as “Shexiang Tongxin Drops” which can effectively inhibit the synthesis of α-SMA, Col1 and Col3 (21). However, most of the above methods involve exogenous administration of antagonists, anti-inflammatory drugs and other drugs to inhibit fibrosis, which leads to poor specificity, many adverse reactions, and unsatisfactory clinical effects. Therefore, it is imperative to clarify the pathological mechanism of cardiac fibrosis and explore direct targeted drugs to solve these challenges.

A number of therapeutic strategies targeting fibroblasts have emerged in recent studies. Such as cell reprogramming technology, it can directly induce fibroblasts into cardiac-like myocytes (iCLMs), which are expected to act as cardiomyocytes to directly enhance cardiac function (22). Besides, CAR-T immunotherapy has also been applied to the treatment of anti-fibrosis, using endogenous protein markers to directly target cardiac fibroblasts to optimize the therapeutic effect (23). Of course, cardiac repair through the activation of acute immune response by stem cells is also an important direction for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis and heart failure (24). In addition, recent studies have found that some drug results in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases have unexpected “off-target” effects on cardiac fibrosis, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and some lipid-lowering drugs (25).

In fact, microRNAs can be a good indicator of cardiac fibrosis. In the presence of fibrosis, there is a downregulation in miR-24 expression (5), while miR-21 expression is upregulated (26). Actually, The miR-21 plays a crucial role in the promotion of fibrosis, as its antagonist has been shown to mitigate the extent of fibrotic development (27). The expression of miR-21 in macrophages modulates intercellular communication between macrophages and fibroblasts, thereby facilitating fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and exacerbating cardiac fibrosis (28). In addition, delivery of cell or tissue-specific anti-miR-29 can effectively suppress Wnt signaling and enhance the occurrence and progression of cardiac fibrosis (29). miR-214-3p exerts an inhibitory effect on cardiac fibrosis through downregulation of NLRC5 gene expression and inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway (30). The miR-126-5p can serve as a highly sensitive biomarker for the identification of sudden cardiac death resulting from coronary artery disease (31). The overexpression of miR-126-3p suppresses TGF-β-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) and attenuates fibroblastogenesis, thereby ameliorating fibrosis (32). In summary, microRNAs can regulate the transdifferentiation of cardiac fibroblasts through intercellular signaling and transcription, which is expected to be a highly specific therapeutic target for cardiac fibrosis.

3 Exosome-borne miR-126 is a key factor in ameliorating cardiac fibrosis

3.1 Exosomes ameliorate cardiac fibrosis

Exosomes are widely distributed throughout the human body, present in almost all bodily fluids, and secreted by the majority of cells. They originate from the invagination of late endosomal membranes, resulting in the formation of numerous intraluminal vesicles that are subsequently released into the extracellular space through plasma membrane fusion. During this process, a multitude of proteins and primitive cell cytoplasm become encapsulated within these invaginated membranes to form intraluminal vesicles. Therefore, exosomes are believed to encompass primitive cellular proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (33). Several studies have identified the presence of mRNAs and microRNAs within exosomes, with certain exosomes exhibiting elevated levels of microRNAs expression compared to their parent cells. These RNAs molecules can be transferred between cells via exosomes, facilitating the regulation of protein synthesis in recipient cells through a process known as intercellular shuttling of exosomal RNAs (34, 35). Exosomes are typically internalized by recipient cells through endocytosis, fusion with the plasma membrane, or receptor-ligand interactions (36–39). Therefore, exosomes can function as mediators of intercellular communication and pathways for modulating the expression of diverse intracellular RNAs and proteins, thereby exerting precise biological effects.

Exosomes are generally classified according to their cell origin, and exosomes from different sources have different effects. Studies have shown that exosomes can exhibit molecular characteristics similar to those of the original cells (40). For example, cardiovascular endothelial cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-214, miR-10a, miR-144, and miR-126 promote endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis (41), inhibit inflammatory responses (42), protect the heart (43), and inhibit apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells (44). Rejuvenation of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells facilitated by miR-294-enriched exosomes derived from embryonic stem cells (45). Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes transport miR-182 for the regulation of inflammation (46). Exosomes derived from adipose stem cells carrying miR-126 exhibit a reduction in infarct size (47). Exosomes derived from cardiomyocytes, carrying miR-222 and miR-143, promote angiogenesis (48). Exosomes derived from macrophages, carrying miR-155 and miR-148a, exert inhibitory effects on fibroblasts proliferation and modulate immune responses (49, 50). mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) derived exosomes carrying miR-19a, miR-23a-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-29, and miR-24 inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis (51), attenuate myocardial injury (52), inhibit apoptosis, slow down the progression of myocardial infarction (53), reduce inflammation, and inhibit fibrosis (54). Exosomes derived from cardiomyosphere-derived cells carrying miR-181b mitigate infarct size (55). Exosomes derived from endothelial progenitor cells carrying miR-126 mitigate infarct size and apoptosis (56) (Table 1). Therefore, exosomes from different sources play their own roles in cell proliferation, angiogenesis and immune regulation, but sometimes exosomes from different sources can also play similar roles. As mentioned above, exosomes from cardiovascular endothelial cells, mesenchymal muscle cells and mesenchymal stem cells are related to inflammation, which means that in the face of the same pathological damage, exosomes from different sources can also play similar roles.

Table 1

| Cells | Exosome Contents |

Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

Endothelial cell |

miR-214 miR-10a miR-144 miR-126 |

Promote angiogenesis Inhibit apoptosis and inflammation Protect the heart |

(41) |

| (42) | |||

| (43) | |||

Embryonic stem cell |

miR-294 | Promotes survival of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells | (45) |

Mesenchymal stromal cells |

miR-182 | Regulate inflammation | (46) |

Fat stem cell |

miR-126 | Reduce infarct size | (47) |

Cardiomyocyte |

miR-222 miR-143 |

Stimulate angiogenesis | (48) |

Macrophage |

miR-155 miR-148a |

Regulate immune response and fibroblast proliferation | (49) |

| (50) | |||

Mesenchymal stem cells |

miR-19a miR-23a-3p miR-135-5p miR-29 miR-24 miR-126 |

Inhibit myocardial cell apoptosis Reduce myocardial injury Reduce inflammation Inhibit fibrosis |

(51) |

| (53) | |||

| (52) | |||

| (54) | |||

Cardiomyosphere-derived cells |

miR-181b | Reduce infarct size | (55) |

Endothelial progenitor cells |

miR-126 | Reduce cell apoptosis Reduce infarct size |

(56) |

Protective effects of different cell exosomes on the heart.

Endothelial cell-derived exosomes, carrying miR-214, miR-10a, miR-144 and miR-126 promote angiogenesis, inhibit apoptosis and inflammation, and protect the heart. Embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes, harboring miR-294, promote viability in both cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes carry miR-182 to regulate inflammation. Fat stem cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-126 reduce infarct size. Cardiomyocyte-derived exosomes carrying miR-222, miR-143 stimulate angiogenesis. Macrophage-derived exosomes carrying miR-155 and miR-148a regulate immune responses and fibroblast proliferation. MSC-derived exosomes, carrying miR-19a, miR-23a-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-29, and miR-24, inhibit myocardial cell apoptosis, reduce myocardial injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. Cardiomyosphere-derived cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-181b reduce infarct size. Endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes, carrying miR-126 reduce infarct size and apoptosis.

Recent research has found that the protective effect of exosomes on the heart is largely achieved through the microRNAs carried by it. Exosomes-derived circ_0001785 can reduce endothelial cell damage through miR-513a-5p/TGFBR3 ceRNA network mechanism, thereby delaying atherosclerosis (57), exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cells pretreated with tanshinone IIA (TSA) carrying miR-223-5p reduced monocyte infiltration and enhanced angiogenesis to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (58), mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-125a-5p can promote angiogenesis and attenuate fibroblasts proliferation and activation, thereby helping to improve cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammation (59). Therefore, exosomes can reduce inflammation and myocardial injury, inhibit the proliferation and activation of cardiac fibroblasts, and reduce the expression of collagen fibers by carrying microRNAs, thereby slowing down the occurrence and development of cardiac fibrosis.

3.2 miR-126 is a key factor in cardiac protection

The expression of miR-126 is predominantly observed in endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells (60). Conversely, miR-126-3p exhibits exclusive localization within the endothelial cells of the heart and kidney (32). Among the diverse repertoire of microRNAs, miR-126 plays a pivotal role in conferring cardioprotection. The miR-126 not only exerts pro-angiogenic effects, attenuates vascular inflammation, modulates autophagy, and mitigates endothelial cell apoptosis through targeted regulation of downstream proteins but also holds promise as a potential biomarker for prognostication and therapeutic monitoring in acute myocardial infarction (61, 62). Experimental evidence suggests that miR-126 derived from mesenchymal stem cells may enhance angiogenesis in infarcted myocardium through the AKT/ERK signaling pathway (63). Furthermore, miR-126 functions as a hypoxia-inducible target of HAT/HDAC, thereby facilitating cardioprotection through the selective activation of cell survival and proangiogenic pathways during ischemic conditions (64). Additionally, in vascular endothelial cells, miR-126 augments the VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) pathway, thereby facilitating angiogenesis through precise targeting and regulation of Spred1 and PI3KR2 genes (65). Additionally, the downregulation of miR-126 serves as a significant biomarker for the diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases. For instance, patients with coronary artery disease exhibit substantially reduced levels of miR-126 in their endothelial cells (66). Significantly reduced levels of plasma miR-126 and downregulation of serum miR-126-3p were observed in patients with myocardial infarction compared to healthy individuals (67, 68). Therefore, miR-126 plays a crucial role in maintaining normal cardiac function.

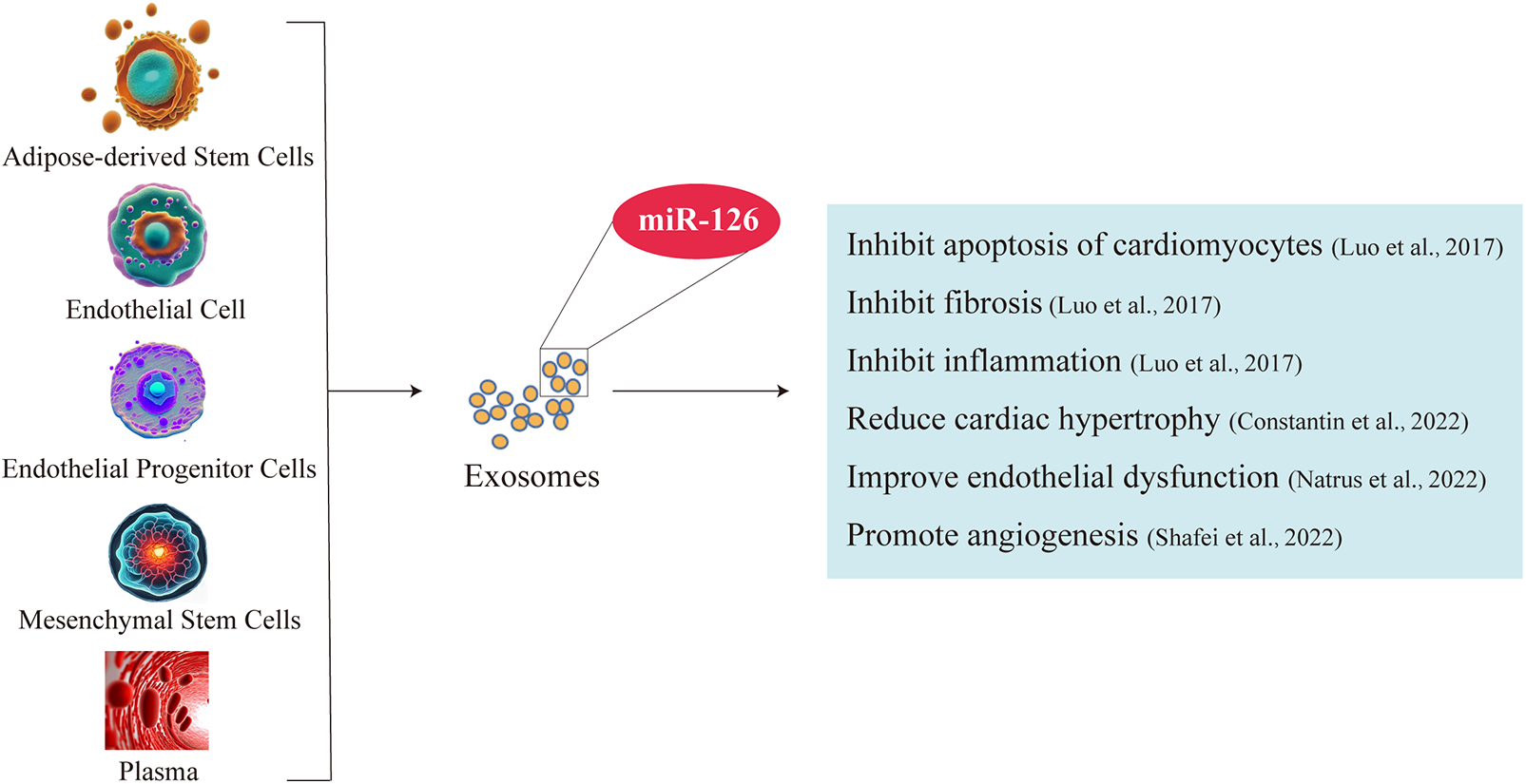

3.3 Exosomes are important carriers of miR-126 for cardiac protection

After overexpressing miR-126 in exosomes secreted by adipose-derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), immunofluorescence analysis revealed the transfer of the upregulated miR-126 between ADSCs and H9C2 cells. This intercellular transfer not only promoted cell proliferation but also conferred protection against apoptosis, thereby mitigating damage to H9C2 cardiomyocytes and attenuating infarct area fibrosis. The ADSC-secreted exosomes containing miR-126 effectively suppressed cardiac inflammation by inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory factors IL1-β, IL-6, and TNF-a (47). Furthermore, stem cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-126 exhibit the potential to mitigate cardiac hypertrophy by impeding the inflammatory processes associated with it (69). Enhancement of cellular paracrine secretion through overexpression of plasma-derived exosome-borne miR-126 mitigates endothelial dysfunction and congestive heart failure (70). Moreover, exosome-mediated delivery of miR-126 plays a pivotal role in promoting angiogenesis and maintaining vascular integrity, thereby exerting a crucial influence on the prevention of heart failure and modulation of cardiac function (44). This suggests that exosome-mediated miR-126 not only inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac inflammation, but also reduces fibrosis, alleviates endothelial dysfunction, and enhances angiogenesis. Therefore, exosomes are important carriers for miR-126 to play a cardiac protective role (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Exosomes are important carriers of miR-126 for its cardioprotective effects. Exosomes of fat stem cell, endothelial cell, endothelial progenitor cells, mesenchymal stem cells and plasma enriched in miR-126. Exosome-borne miR-126 inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac inflammation, ameliorates fibrosis and endothelial dysfunction, and promotes angiogenesis.

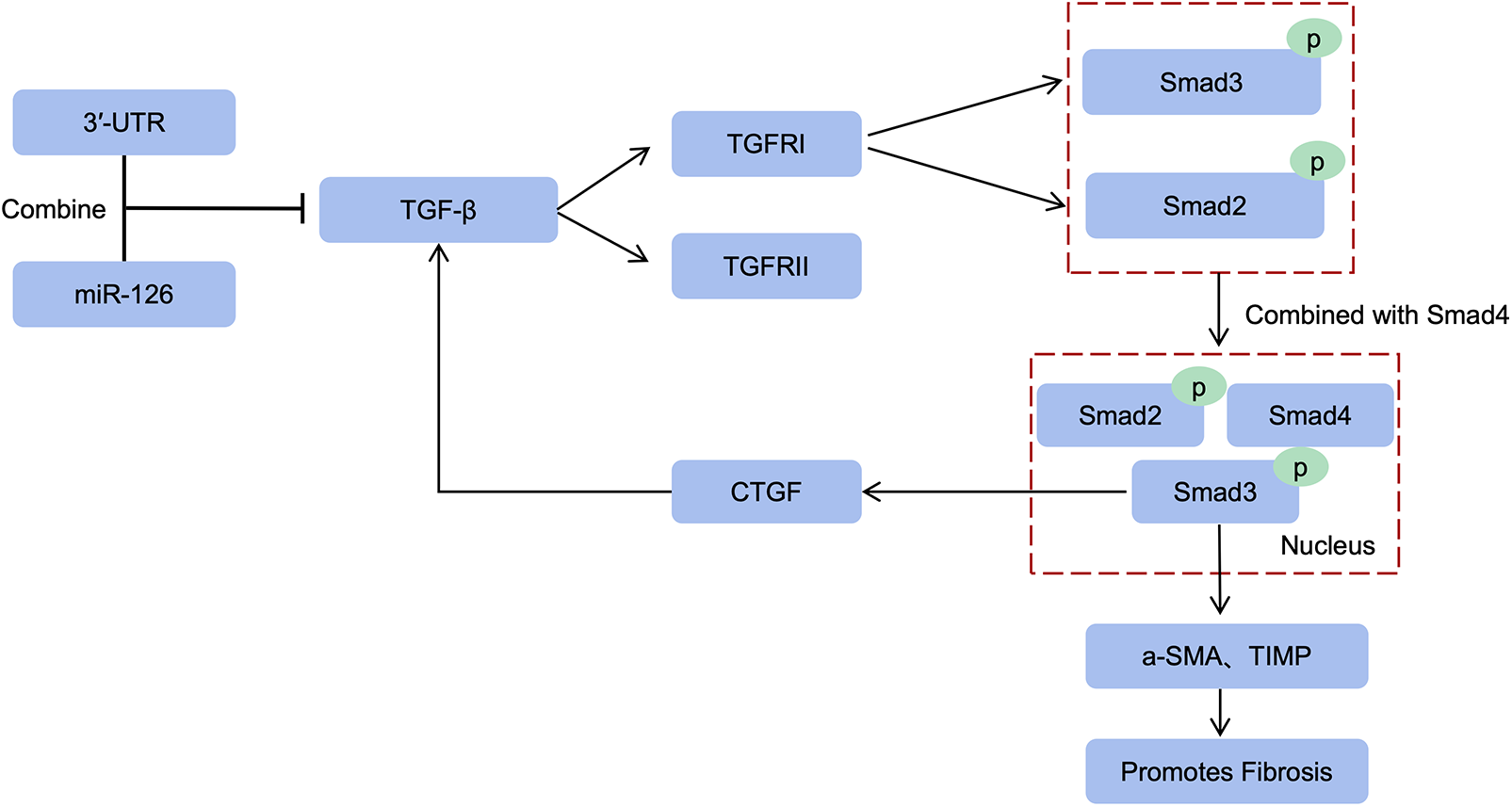

3.4 miR-126 regulates TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway to improve cardiac fibrosis

TGF-β serves as a pivotal regulator that orchestrates the transition from fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. This intricate process entails the binding of TGF-β to transmembrane receptor serine/threonine kinases (both type I and II), culminating in the formation of a complex. Subsequently, these complex triggers transphosphorylation of GS fragments within the type I receptor by the kinase activity of the type II receptor. Consequently, activation of the type I receptor ensues, leading to downstream phosphorylation events involving Smad2/3 (71). The phosphorylated molecules subsequently form a complex with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus, facilitating their transcriptional activity. Within this context, Smad3 within the complex stimulates the transcription of pro-fibrotic molecules such as α-SMA and TIMP, thereby significantly contributing to fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation (72). The myofibroblasts secrete a large amount of extracellular matrix, which forms scar tissue after excessive deposition. This process reduces the compliance of the ventricular wall and eventually leads to cardiac dysfunction.

It is noteworthy that miR-126 exerts translational inhibition on TGF-β by specifically binding to the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of TGF-β mRNA, thereby attenuating its expression and establishing TGF-β as a direct target of miR-126 (73). The levels of TGF-β are increased in cardiomyocytes with bidirectional knockout of miR-126 (74). Therefore, miR-126 not only reduced TGF-β expression, but also significantly downregulated the expression levels of TGF-β, Smad2 and Smad3, which resulted in a reduction in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inhibition of cardiac fibroblasts activation (75). Up-regulation of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression promotes TGF-β-induced fibrosis. In addition, Smad3 deficiency inhibits TGF-β-induced fibrosis by down-regulating the expression of connective tissue growth factor (76). Therefore, the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway plays a crucial role in fibrosis, and miR-126 effectively inhibits it to improve cardiac fibrosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2

miR-126 inhibits the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway. miR-126 inhibits TGF-β translation thereby reducing type I receptor activation, and downstream Smad2/3 phosphorylation is also inhibited. Smad3 of the complex induces α-SMA, TIMP transcription to promote fibrosis. In addition, upregulation of CTGF expression promotes TGF-β-induced fibrosis, and Smad3 deficiency reduces fibrosis by decreasing CTGF expression.

4 Exercise promotes exosome release to regulate cardiac function

Exercise exerts a profound positive impact on cardiovascular health. Experimental findings have demonstrated that during the post-infarction period, when ventricular contractility is reduced and cardiac function is compromised, eight weeks of continuous and intermittent exercise effectively enhance cardiac ejection fraction and overall function. Notably, the effect of intermittent exercise is particularly significant. This can be attributed to exercise's ability to enhance cardiac function by increasing blood delivery capacity to infarcted marginal zones (77). In comparison to aerobic exercise, “Hex” exercises (which encompass activities such as walking and gymnastics performed in warm water at temperatures ranging from 28 to 32 degrees Celsius) demonstrate a superior antihypertensive effect in individuals with persistent hypertension when conducted for 60 min, three times per week over a duration of 12 weeks (78). Moderate-intensity aerobic exercises, such as running, cycling, and dancing, have demonstrated efficacy in both the prevention and management of stage 1 hypertension. Furthermore, moderate dynamic resistance exercises like weightlifting can effectively reduce blood pressure to a significant extent (79). Long-term aerobic exercise effectively mitigates the risk of coronary heart disease by significantly reducing levels of apolipoprotein C3 and triglycerides (80).

Heart failure is a product of various cardiovascular diseases developed to the end stage, and exercise training can improve heart failure has been widely recognized (81). As an important pathological process of heart failure, can exercise have a good regulatory effect on cardiac fibrosis? We found that aerobic training plays an important role in attenuating cardiac fibrosis caused by vitamin D deficiency through its inhibitory effect on fibrotic factors and pathways (82), another study found that aerobic training combined with resistance exercise and vitamin D supplementation could reduce cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway and regulating collagen fiber expression (83), running training, the most maneuverable aerobic exercise, still has a good improvement effect on cardiac fibrosis, for example, Ang II-induced cardiac fibrosis was attenuated in mice trained by running for 6 weeks (84), in a rat model of arthritis, individualized running training not only reduced fibrosis, but also alleviated the severity of arthritis (85). Moreover, exercise training can modulates the fibroblasts FGF21 factor and TGF-β1-Smad2/3-MMP2/9 signaling pathway to attenuate collagen fiber production (86). Exercise can also inhibits the induction of physiologic hypertrophy and myocardium by regulating cardiac microRNAs, and prevents cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction (87). To sum up, exercise can not only play a positive role in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and coronary heart disease, but also better alleviate the pathological process of cardiac fibrosis. Aerobic exercise is often used as an example, which may be related to the significant effect of aerobic exercise on patients with heart failure. A meta-analysis has confirmed that aerobic training can reverse left ventricular remodeling in clinically stable heart failure patients (88). A comprehensive review suggests that a single bout of exercise can enhance exosome secretion, exhibiting variations in the metabolic kinetics of exosome production and clearance among individuals with different exercise intensities. Furthermore, prolonged and sustained exercise does not significantly affect the size and concentration of circulating exosomes, however, it selectively augments the release of exosomes from specific cellular sources. Moreover, long-term exercise exhibits a positive health-promoting effect by modulating both the type and quantity of produced exosomes, achieved through precise regulation of specific exosomal expression patterns (89). In conclusion, variations in exercise modes and intensities have been observed to influence the release of exosomes as well as their cargo of diverse microRNAs. Nonetheless, it is evident that exercise promotes exosome secretion, facilitating intercellular communication and regulation through microRNAs signaling. Moreover, exercise has the potential to modulate cardiovascular function via microRNAs encapsulated within exosomes (Table 2). For example, physical exercise enhances the levels of miR-126 in exosomes derived from circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs), thereby improving outcomes in mice with ischemic stroke (56). Exercise also promotes the release of plasma exosomes harboring miR-342, which effectively suppresses cardiomyocyte apoptosis and confers cardioprotection to the heart (97). Moreover, it effectively attenuates cardiac fibrosis by suppressing the MMP9 gene expression via exosomes derived from cardiomyocytes (98). Therefore, exosomes can carry microRNAs to play specific roles, and exercise can effectively stimulate the secretion and release of exosomes in cells, thus exerting their biological effects.

Table 2

| Exercise modalities | Source of exosomes | microRNAs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endurance exercise | Plasma | miR-181a-5p | (90) |

| Marathon | Plasma and urine | hsa-mir-582-3p hsa-mir-199a-3p | (91) |

| Inertial resistance training | Hematology | miR-206 miR-146a | (92) |

| Physical exercise | Muscle and plasma | miR-21-5p miR-134-3p miR-107 | (93) |

| Acute endurance exercise | Sweat cell | miR-21 | (94) |

| Acute resistance training | Plasma | miR-532 miR-133a | (95) |

| Two consecutive rounds of muscle damage exercise | Hematology | miR-1 miR-206 | (96) |

| Physical exercise | Endothelial progenitor cells | miR-126 | (8) |

| Permanent exercise | Plasma and endothelial cells | miR-342-5p | (97) |

Different exercise modalities promote the release of microRNAs from exosomes.

Endurance exercise promotes the release of miR-181a-5p from plasma exosomes. Marathon promotes the release of hsa-mir-582-3p, hsa-mir-199a-3p from plasma and urinary exosomes. Inertial resistance training promotes the release of miR-206, miR-46a from blood exosomes. Physical exercise promotes the release of miR-21-5p, miR-134-3p, and miR-107 from muscle and plasma exosomes. Acute endurance exercise promotes the release of miR-21 from exosomes in sweat cells. Acute resistance training promotes plasma exosomes release of miR-532, miR-133a. Two consecutive rounds of muscle-damaging exercise promoted the release of miR-1 and miR-206 from exosomes in the blood. Physical exercise promotes miR-126 release from exosomes in endothelial progenitor cells. Permanent exercise promotes exosomes release from plasma and endothelial cells miR-342-5p.

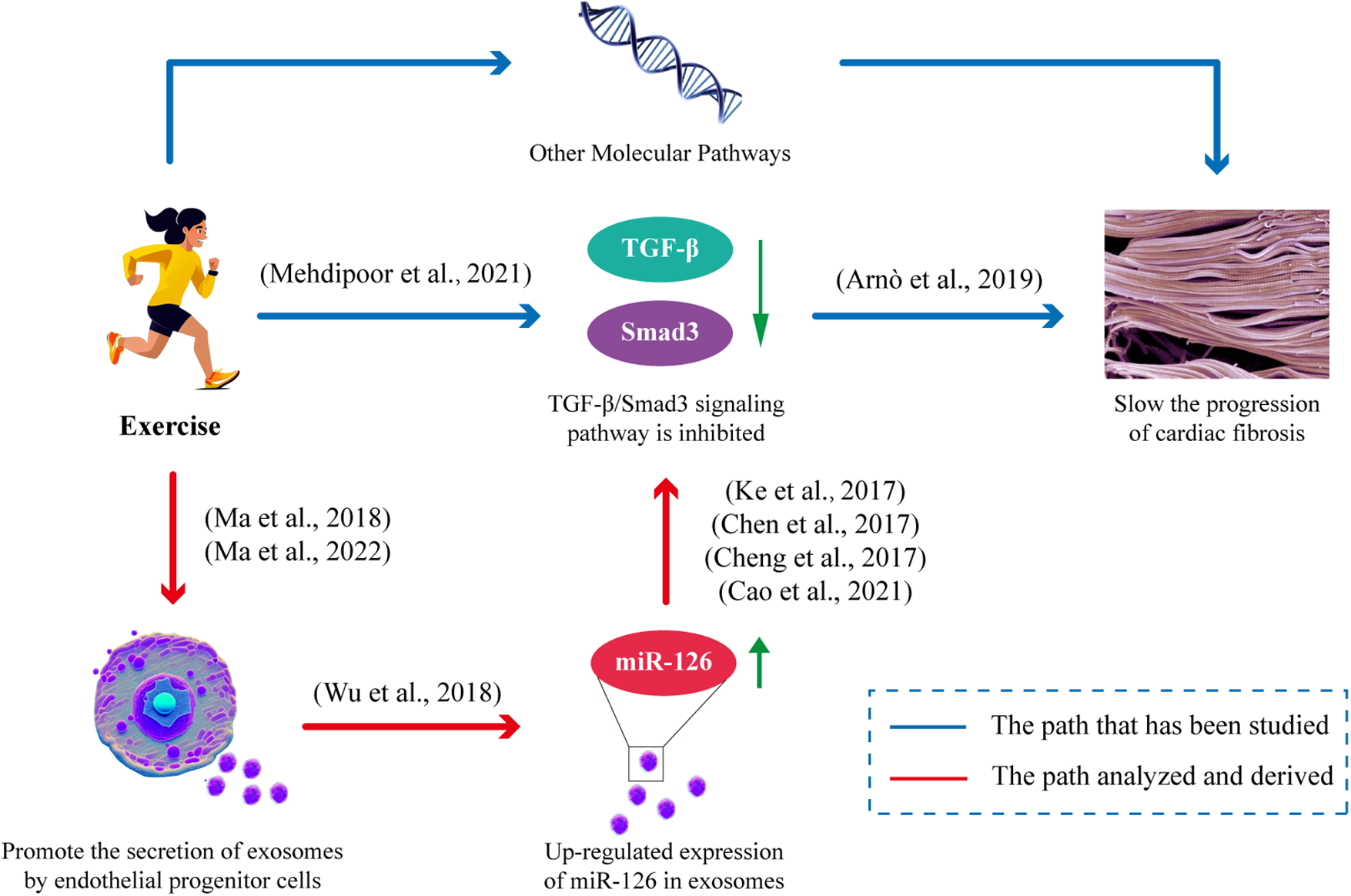

5 Exercise promotes endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes release and miR-126 upregulation to improve cardiac fibrosis

Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs) inherently possess robust repair and regeneration capabilities. In comparison to exosomes derived from alternative sources, EPC-derived exosomes offer distinct advantages due to their notable enrichment in miR-126, a pivotal factor in mitigating cardiac injury. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that moderate exercise can elevate the release of EPC-derived exosomes. Studies have demonstrated that endurance aerobic exercise can enhance the level of miR-126 in circulation and myocardium, augment EPCs, EPC-derived extracellular vesicles (EPC-Exos), and their cargo of miR-126 to exert a cardioprotective effect, with moderate intensity exercise being more efficacious than low intensity exercise (8, 62). Furthermore, the levels of miR-126 in EPC-derived exosomes (EPC-Exos) are positively influenced by exercise intensity, and these exosomes exhibit a comparable molecular signature to that of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (8, 40). Exercise not only enhances the expression of miR-126 within endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes (EPC-Exos), but also augments the migratory capacity of EPCs when miR-126 is overexpressed in exosomes (40), thereby facilitating their transportation to the heart and exerting protective effects. These exosomes secreted by EPCs exhibit cardioprotective effects by stimulating cardiac fibroblasts, upregulating the expression of endothelial cell-specific markers, and downregulating proteins associated with fibrosis (99). The exosomes secreted by endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) additionally enhance peri-infarct myocardial angiogenesis and improve hemodynamic function following infarction (100). Additionally, they provide cardiovascular protection through their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, as well as their ability to modulate apoptosis and gene expression (101–103), all while exhibiting high levels of miR-126-3p and miR-126-5p (104). Importantly, studies have confirmed that exosomes effectively reach the heart and are efficiently internalized by neighboring and distant cells, thereby facilitating the regulation of receptor cells (105, 106). Experimental evidence has demonstrated the substantial uptake capacity of exosomes by heart cells, which may occur through direct interaction between transmembrane proteins on the exosome and signaling receptors in cardiomyocytes, or via fusion of the exosome with the plasma membrane of the cardiomyocyte to facilitate cargo transport, such as miR-126, into the cardiomyocyte (107). The TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway has been identified as a pivotal mediator of the cardiac fibrotic response (108). miR-126 attenuates cardiac fibrosis by suppressing the protein expression of TGF-β, Smad2, and Smad3 (73–75) (Figure 3). In conclusion, exercise can stimulate the secretion and release of endothelial progenitor cell exosomes (EPC-Exos), and inhibit TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway by upregulating the expression of miR-126 in exosomes to slow down the level of cardiac fibrosis.

Figure 3

Exercise improves cardiac fibrosis mitigation by facilitating the release of EPC-Exos and modulating miR-126 expression. Exercise stimulates the secretion of EPC-Exos, thereby augmenting the levels of its constituent, miR-126. miR-126 effectively suppresses the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway, consequently impeding cardiac fibrosis progression.

6 Conclusions

miR-126 plays a key role in cardiac protection, and EPC-Exos also carry a large amount of miR-126. It was found that exercise can effectively stimulate the secretion and release of exosomes by EPCs, and up-regulate the expression of miR-126 in exosomes, which not only reduces the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes, but also improves cardiac fibrosis by targeting TGF-β. Therefore, miR-126 carried by EPC-Exos is expected to be a potential regulatory factor for the prevention and treatment of cardiac fibrosis. Exercise can play a protective role in the heart by regulating the release of exosomes and the expression of contents, which clarifies a new mechanism of exercise promoting cardiac rehabilitation. However, further investigation is warranted to elucidate the precise relationship between exercise intensity, duration, and exosome release quantity, as well as microRNAs expression. Continued research and study are necessary for the clinical application of anti-cardiac fibrosis methods such as exercise or exogenous exosome administration. The potential of exercise-mediated exosome therapy for cardiac fibrosis may emerge as a focus in future cardiovascular disease research.

Statements

Author contributions

GF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supported by Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department (21B0361), Research Fund of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Hunan Province, China (2021180), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82274412).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

The Writing Committee of the Report on Cardiovascular Health Diseases in China. Report on cardiovascular health and diseases in China 2022: an updated summary. Chin Circ J. (2023) 38:583–612.

2.

Van Rooij E Sutherland LB Qi X Richardson JA Hill J Olson EN . Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. (2007) 316:575–9. 10.1126/science.1139089

3.

Small EM Frost RJ Olson EN . MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation. (2010) 121:1022–32. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.889048

4.

Van Rooij E Sutherland LB Thatcher JE Dimaio JM Naseem RH Marshall WS et al Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2008) 105:13027–32. 10.1073/pnas.0805038105

5.

Wang J Huang W Xu R Nie Y Cao X Meng J et al MicroRNA-24 regulates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. (2012) 16:2150–60. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01523.x

6.

Qiang L Hong L Ningfu W Huaihong C Jing W . Expression of miR-126 and miR-508-5p in endothelial progenitor cells is associated with the prognosis of chronic heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168:2082–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.160

7.

Bang C Batkai S Dangwal S Gupta SK Foinquinos A Holzmann A et al Cardiac fibroblast-derived microRNA passenger strand-enriched exosomes mediate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. (2014) 124:2136–46. 10.1172/JCI70577

8.

Ma C Wang J Liu H Chen Y Ma X Chen S et al Moderate exercise enhances endothelial progenitor cell exosomes release and function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2018) 50:2024–32. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001672

9.

Cleutjens JP Verluyten MJ Smiths JF Daemen MJ . Collagen remodeling after myocardial infarction in the rat heart. Am J Pathol. (1995) 147:325–38.

10.

Qin W Cao L Massey IY . Role of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in cardiac fibrosis. Mol Cell Biochem. (2021) 476:4045–59. 10.1007/s11010-021-04219-w

11.

Nakamura K Miyoshi T Yoshida M Akagi S Saito Y Ejiri K et al Pathophysiology and treatment of diabetic cardiomyopathy and heart failure in patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:3587. 10.3390/ijms23073587

12.

Zhu L Wang W Ren C Wang Y Zhang G Liu J et al Cellular phenotypic transformation in heart failure caused by coronary heart disease and dilated cardiomyopathy: delineating at single-cell level. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:402. 10.3390/biomedicines10020402

13.

Tomasek JJ Gabbiani G Hinz B Chaponnier C Brown RA . Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2002) 3:349–63. 10.1038/nrm809

14.

Ramirez AM Shen Z Ritzenthaler JD Roman J . Myofibroblast transdifferentiation in obliterative bronchiolitis: TGF-beta signaling through Smad3-dependent and -independent pathways. Am J Transplant. (2006) 6:2080–8. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01430.x

15.

Chen X Xu J Jiang B Liu D . Bone morphogenetic protein-7 antagonizes myocardial fibrosis induced by atrial fibrillation by restraining transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/Smads signaling. Med Sci Monit. (2016) 22:3457–68. 10.12659/MSM.897560

16.

Zhou Y Zhao Y Du H Suo Y Chen H Li H et al Downregulation of CFTR is involved in the formation of hypertrophic scars. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:9526289. 10.1155/2020/9526289

17.

Li N Hang W Shu H Zhou N . Pirfenidone alleviates cardiac fibrosis induced by pressure overload via inhibiting TGF-β1/Smad3 signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. (2022c) 26:4548–55. 10.1111/jcmm.17478

18.

Alrasheed NM Alammari RB Alshammari TK Alamin MA Alharbi AO Alonazi AS et al A1a adrenoreceptor blockade attenuates myocardial infarction by modulating the integrin-linked kinase/TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2023) 23:153. 10.1186/s12872-023-03188-w

19.

Chen Y Shi J Zhang Y Miao J Zhao Z Jin X et al An injectable thermosensitive hydrogel loaded with an ancient natural drug colchicine for myocardial repair after infarction. J Mater Chem B. (2020) 8:980–92. 10.1039/C9TB02523E

20.

Kawamura M Ito H Onuki T Miyoshi F Watanabe N Asano T et al Candesartan decreases type III procollagen-N-peptide levels and inflammatory marker levels and maintains sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2010) 55:511–7. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181d70690

21.

Tan YF Fu YH Zhang MZ . Shexiang tongxin dropping pill allieviates heart failure via extracellula matrix-receptor interaction pathways based on RNA-seq transcriptomics and experimental studies. Chin J Integr Med. (2023) 29:600–7. 10.1007/s11655-023-3633-0

22.

Ieda M Fu JD Delgado-Olguin P Vedantham V Hayashi Y Bruneau BG et al Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. (2010) 142:375–86. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002

23.

Tran E Chinnasamy D Yu Z Morgan RA Lee CC Restifo NP et al Immune targeting of fibroblast activation protein triggers recognition of multipotent bone marrow stromal cells and cachexia. J Exp Med. (2013) 210:1125–35. 10.1084/jem.20130110

24.

Vagnozzi RJ Maillet M Sargent MA Khalil H Johansen AKZ Schwanekamp JA et al An acute immune response underlies the benefit of cardiac stem cell therapy. Nature. (2020) 577:405–9. 10.1038/s41586-019-1802-2

25.

Porter KE Turner NA . Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther. (2009) 123:255–78. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002

26.

Villar AV García R Merino D Llano M Cobo M Montalvo C et al Myocardial and circulating levels of microRNA-21 reflect left ventricular fibrosis in aortic stenosis patients. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 167:2875–81. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.07.021

27.

Cardin S Guasch E Luo X Naud P Le Quang K Shi Y et al Role for MicroRNA-21 in atrial profibrillatory fibrotic remodeling associated with experimental postinfarction heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2012) 5:1027–35. 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.973214

28.

Ramanujam D Schön AP Beck C Vaccarello P Felician G Dueck A et al MicroRNA-21-dependent macrophage-to-fibroblast signaling determines the cardiac response to pressure overload. Circulation. (2021) 143:1513–25. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050682

29.

Sassi Y Avramopoulos P Ramanujam D Grüter L Werfel S Giosele S et al Cardiac myocyte miR-29 promotes pathological remodeling of the heart by activating Wnt signaling. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:1614. 10.1038/s41467-017-01737-4

30.

Kun Y . MiR-214-3p regulates cardiac fibrosis via miR-214-3p/NLRC5 axis (master’s thesis). Zhejiang University (2019).

31.

Li L He X Liu M Yun L Cong B . Diagnostic value of cardiac miR-126-5p, miR-134-5p, and miR-499a-5p in coronary artery disease-induced sudden cardiac death. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022b) 9:944317. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.944317

32.

Jordan NP Tingle SJ Shuttleworth VG Cooke K Redgrave RE Singh E et al MiR-126-3p is dynamically regulated in endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition during fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:8629. 10.3390/ijms22168629

33.

Sahu R Kaushik S Clement CC Cannizzo ES Scharf B Follenzi A et al Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell. (2011) 20:131–9. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003

34.

Valadi H Ekström K Bossios A Sjöstrand M Lee JJ Lötvall JO . Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:654–9. 10.1038/ncb1596

35.

Huang X Yuan T Tschannen M Sun Z Jacob H Du M et al Characterization of human plasma-derived exosomal RNAs by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. (2013) 14:319. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-319

36.

Segura E Guérin C Hogg N Amigorena S Théry C . CD8 + dendritic cells use LFA-1 to capture MHC-peptide complexes from exosomes in vivo. J Immunol. (2007) 179:1489–96. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1489

37.

Parolini I Federici C Raggi C Lugini L Palleschi S De Milito A et al Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. (2009) 284:34211–22. 10.1074/jbc.M109.041152

38.

Fitzner D Schnaars M Van Rossum D Krishnamoorthy G Dibaj P Bakhti M et al Selective transfer of exosomes from oligodendrocytes to microglia by macropinocytosis. J Cell Sci. (2011) 124:447–58. 10.1242/jcs.074088

39.

O'loughlin AJ Woffindale CA Wood MJ . Exosomes and the emerging field of exosome-based gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. (2012) 12:262–74. 10.2174/156652312802083594

40.

Wu X Liu Z Hu L Gu W Zhu L . Exosomes derived from endothelial progenitor cells ameliorate acute lung injury by transferring miR-126. Exp Cell Res. (2018) 370:13–23. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.06.003

41.

Van Balkom BW De Jong OG Smits M Brummelman J Den Ouden K De Bree PM et al Endothelial cells require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood. (2013) 121:3997–4006. s3991–3915. 10.1182/blood-2013-02-478925

42.

Njock MS Cheng HS Dang LT Nazari-Jahantigh M Lau AC Boudreau E et al Endothelial cells suppress monocyte activation through secretion of extracellular vesicles containing antiinflammatory microRNAs. Blood. (2015) 125:3202–12. 10.1182/blood-2014-11-611046

43.

Li J Rohailla S Gelber N Rutka J Sabah N Gladstone RA et al MicroRNA-144 is a circulating effector of remote ischemic preconditioning. Basic Res Cardiol. (2014) 109:423. 10.1007/s00395-014-0423-z

44.

Shafei S Khanmohammadi M Ghanbari H Nooshabadi VT Tafti SHA Rabbani S et al Effectiveness of exosome mediated miR-126 and miR-146a delivery on cardiac tissue regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. (2022) 390:71–92. 10.1007/s00441-022-03663-4

45.

Khan M Nickoloff E Abramova T Johnson J Verma SK Krishnamurthy P et al Embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes promote endogenous repair mechanisms and enhance cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Circ Res. (2015) 117:52–64. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305990

46.

Zhao J Li X Hu J Chen F Qiao S Sun X et al Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury through miR-182-regulated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc Res. (2019) 115:1205–16. 10.1093/cvr/cvz040

47.

Luo Q Guo D Liu G Chen G Hang M Jin M . Exosomes from miR-126-overexpressing adscs are therapeutic in relieving acute myocardial ischaemic injury. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2017) 44:2105–16. 10.1159/000485949

48.

Ribeiro-Rodrigues TM Laundos TL Pereira-Carvalho R Batista-Almeida D Pereira R Coelho-Santos V et al Exosomes secreted by cardiomyocytes subjected to ischaemia promote cardiac angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. (2017) 113:1338–50. 10.1093/cvr/cvx118

49.

Dai Y Wang S Chang S Ren D Shali S Li C et al M2 macrophage-derived exosomes carry microRNA-148a to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting TXNIP and the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2020) 142:65–79. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.02.007

50.

Liu S Chen J Shi J Zhou W Wang L Fang W et al M1-like macrophage-derived exosomes suppress angiogenesis and exacerbate cardiac dysfunction in a myocardial infarction microenvironment. Basic Res Cardiol. (2020) 115:22. 10.1007/s00395-020-0781-7

51.

Ma Z Lan YH Liu ZW Yang MX Zhang H Ren JY . MiR-19a suppress apoptosis of myocardial cells in rats with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through PTEN/Akt/P-Akt signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2020) 24:3322–30. 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20700

52.

Song Y Wang B Zhu X Hu J Sun J Xuan J et al Human umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs exosome attenuate myocardial injury by inhibiting ferroptosis in acute myocardial infarction mice. Cell Biol Toxicol. (2021) 37:51–64. 10.1007/s10565-020-09530-8

53.

Mao Q Liang XL Zhang CL Pang YH Lu YX . LncRNA KLF3-AS1 in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorates pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction through miR-138-5p/Sirt1 axis. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2019) 10:393. 10.1186/s13287-019-1522-4

54.

Shao L Zhang Y Lan B Wang J Zhang Z Zhang L et al MiRNA-Sequence indicates that mesenchymal stem cells and exosomes have similar mechanism to enhance cardiac repair. Biomed Res Int. (2017) 2017:4150705. 10.1155/2017/4150705

55.

De Couto G Gallet R Cambier L Jaghatspanyan E Makkar N Dawkins JF et al Exosomal microRNA transfer into macrophages mediates cellular postconditioning. Circulation. (2017) 136:200–14. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024590

56.

Wang J Liu H Chen S Zhang W Chen Y Yang Y . Moderate exercise has beneficial effects on mouse ischemic stroke by enhancing the functions of circulating endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes. Exp Neurol. (2020) 330:113325. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113325

57.

Tong X Dang X Liu D Wang N Li M Han J et al Exosome-derived circ_0001785 delays atherogenesis through the ceRNA network mechanism of miR-513a-5p/TGFBR3. J Nanobiotechnology. (2023) 21:362. 10.1186/s12951-023-02076-x

58.

Li S Yang K Cao W Guo R Liu Z Zhang J et al Tanshinone IIA enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via up-regulating miR-223-5p. J Control Release. (2023) 358:13–26. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.04.014

59.

Gao L Qiu F Cao H Li H Dai G Ma T et al Therapeutic delivery of microRNA-125a-5p oligonucleotides improves recovery from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice and swine. Theranostics. (2023) 13:685–703. 10.7150/thno.73568

60.

Yan T Liu Y Cui K Hu B Wang F Zou L . MicroRNA-126 regulates EPCs function: implications for a role of miR-126 in preeclampsia. J Cell Biochem. (2013) 114:2148–59. 10.1002/jcb.24563

61.

He Y Zhong J Huang S Shui X Kong D Chen C et al Elevated circulating miR-126-3p expression in patients with acute myocardial infarction: its diagnostic value. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2017) 10:11051–6.

62.

Ma Y Liu H Wang Y Xuan J Gao X Ding H et al Roles of physical exercise-induced MiR-126 in cardiovascular health of type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. (2022) 14:169. 10.1186/s13098-022-00942-6

63.

Chen JJ Zhou SH . Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing MiR-126 enhance ischemic angiogenesis via the AKT/ERK-related pathway. Cardiol J. (2011) 18:675–81. 10.5603/CJ.2011.0032

64.

Shi H Chen L Wang H Zhu S Dong C Webster KA et al Synergistic induction of miR-126 by hypoxia and HDAC inhibitors in cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2013) 430:827–32. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.061

65.

Fei L Zhang J Niu H Yuan C Ma X . Effects of rosuvastatin and miR-126 on myocardial injury induced by acute myocardial infarction in rats: role of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A). Med Sci Monit. (2016) 22:2324–34. 10.12659/MSM.896983

66.

Fichtlscherer S De Rosa S Fox H Schwietz T Fischer A Liebetrau C et al Circulating microRNAs in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. (2010) 107:677–84. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215566

67.

Long G Wang F Duan Q Chen F Yang S Gong W et al Human circulating microRNA-1 and microRNA-126 as potential novel indicators for acute myocardial infarction. Int J Biol Sci. (2012) 8:811–8. 10.7150/ijbs.4439

68.

Hsu A Chen SJ Chang YS Chen HC Chu PH . Systemic approach to identify serum microRNAs as potential biomarkers for acute myocardial infarction. Biomed Res Int. (2014) 2014:418628. 10.1155/2014/418628

69.

Constantin A Comarița IK Alexandru N Filippi A Bojin F Gherghiceanu M et al Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles reduce the expression of molecules involved in cardiac hypertrophy-in a model of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:1003684. 10.3389/fphar.2022.1003684

70.

Natrus L Labudzynskyi D Muzychenko P Chernovol P Klys Y . Plasma-derived exosomes implement miR-126-associated regulation of cytokines secretion in PBMCs of CHF patients in vitro. Acta Biomed. (2022) 93:e2022066. 10.23750/abm.v93i3.12449

71.

Arnò B Galli F Roostalu U Aldeiri BM Miyake T Albertini A et al TNAP limits TGF-β-dependent cardiac and skeletal muscle fibrosis by inactivating the SMAD2/3 transcription factors. J Cell Sci. (2019) 132:jcs234948. 10.1242/jcs.234948

72.

Dees C Pötter S Zhang Y Bergmann C Zhou X Luber M et al TGF-β-induced epigenetic deregulation of SOCS3 facilitates STAT3 signaling to promote fibrosis. J Clin Invest. (2020) 130:2347–63. 10.1172/JCI122462

73.

Cheng XW Wan YF Zhou Q Wang Y Zhu HQ . MicroRNA-126 inhibits endothelial permeability and apoptosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice fed a high-fat diet. Mol Med Rep. (2017) 16:3061–8. 10.3892/mmr.2017.6952

74.

Chen J Cui C Yang X Xu J Venkat P Zacharek A et al MiR-126 affects brain-heart interaction after cerebral ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. (2017) 8:374–85. 10.1007/s12975-017-0520-z

75.

Cao J Xu X Zhang L Zhang D Guo J Wu W et al Influence of miR-126 on TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway in rats with myocardial infarction. Chin J Cardiovasc Rehabil Med. (2021) 30:557–62.

76.

Dobaczewski M Bujak M Li N Gonzalez-Quesada C Mendoza LH Wang XF et al Smad3 signaling critically regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ Res. (2010) 107:418–28. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216101

77.

Song W Tian Z Du S-J . Continuous and interval exercise intervention on the expression of myocardial miRNAs related to angiogenesis and activitation of EGFL7/miR126-PIK3R2/SPRED1 on protecting the hearts of MI rats. China Sport Sci. (2017) 37:57–65. 10.16469/j.css.201702006

78.

Lan L Li Z Qi Q Liu Y . A meta-analysis of the effect of exercise on blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension. Fujian Sports Sci Technol. (2023) 42:37–44.

79.

Gargallo P Casaña J Suso-Martí L Cuenca-Martínez F López-Bueno R Andersen LL et al Minimal dose of resistance exercise required to induce immediate hypotension effect in older adults with hypertension: randomized cross-over controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:14218. 10.3390/ijerph192114218

80.

Wang Y Shen L Xu D . Aerobic exercise reduces triglycerides by targeting apolipoprotein C3 in patients with coronary heart disease. Clin Cardiol. (2019) 42:56–61. 10.1002/clc.23104

81.

Bozkurt B Fonarow GC Goldberg LR Guglin M Josephson RA Forman DE et al Cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure: JACC expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:1454–69. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.030

82.

Cui X Wang K Zhang J Cao ZB . Aerobic exercise ameliorates myocardial fibrosis via affecting vitamin D receptor and transforming growth factor-β1 signaling in vitamin D-deficient mice. Nutrients. (2023) 15:741. 10.3390/nu15030741

83.

Mehdipoor M Damirchi A Razavi Tousi SMT Babaei P . Concurrent vitamin D supplementation and exercise training improve cardiac fibrosis via TGF-β/Smad signaling in myocardial infarction model of rats. J Physiol Biochem. (2021) 77:75–84. 10.1007/s13105-020-00778-6

84.

Feng N Yu H Wang Y Zhang Y Xiao H Gao W . Exercise training attenuates angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis by reducing POU2F1 expression. J Sport Health Sci. (2023) 12:464–76. 10.1016/j.jshs.2022.10.004

85.

Peyronnel C Kessler J Bobillier-Chaumont Devaux S Houdayer C Tournier M Chouk M et al A treadmill exercise reduced cardiac fibrosis, inflammation and vulnerability to ischemia-reperfusion in rat pristane-induced arthritis. Life Sci. (2024) 341:122503. 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122503

86.

Ma Y Kuang Y Bo W Liang Q Zhu W Cai M et al Exercise training alleviates cardiac fibrosis through increasing fibroblast growth factor 21 and regulating TGF-β1-Smad2/3-MMP2/9 signaling in mice with myocardial infarction. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:12341. 10.3390/ijms222212341

87.

Li H Trager LE Liu X Hastings MH Xiao C Guerra J et al lncExACT1 and DCHS2 regulate physiological and pathological cardiac growth. Circulation. (2022a) 145:1218–33. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056850

88.

Haykowsky MJ Liang Y Pechter D Jones LW Mcalister FA Clark AM . A meta-analysis of the effect of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling in heart failure patients: the benefit depends on the type of training performed. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2007) 49:2329–36. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.055

89.

Ma C Liu H Xiong X Yang Y . Exosomal miRNAs—new targets for exercise to promote cardiovascular health. China Sport Sci Technol. (2023) 59:64–71. 10.16470/j.csst.2021037

90.

Guescini M Canonico B Lucertini F Maggio S Annibalini G Barbieri E et al Muscle releases alpha-sarcoglycan positive extracellular vesicles carrying miRNAs in the bloodstream. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0125094. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125094

91.

Kuji T Sugasawa T Fujita SI Ono S Kawakami Y Takekoshi K . A pilot study of miRNA expression profile as a liquid biopsy for full-marathon participants. Sports. (2021) 9:134. 10.3390/sports9100134

92.

Annibalini G Contarelli S Lucertini F Guescini M Maggio S Ceccaroli P et al Muscle and systemic molecular responses to a single flywheel based iso-inertial training session in resistance-trained men. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:554. 10.3389/fphys.2019.00554

93.

D’souza RF Woodhead JST Zeng N Blenkiron C Merry TL Cameron-Smith D et al Circulatory exosomal miRNA following intense exercise is unrelated to muscle and plasma miRNA abundances. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2018) 315:E723–33. 10.1152/ajpendo.00138.2018

94.

Karvinen S Sievänen T Karppinen JE Hautasaari P Bart G Samoylenko A et al MicroRNAs in extracellular vesicles in sweat change in response to endurance exercise. Front Physiol. (2020) 11:676. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00676

95.

Cui S Sun B Yin X Guo X Chao D Zhang C et al Time-course responses of circulating microRNAs to three resistance training protocols in healthy young men. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:2203. 10.1038/s41598-017-02294-y

96.

Lovett JAC Durcan PJ Myburgh KH . Investigation of circulating extracellular vesicle MicroRNA following two consecutive bouts of muscle-damaging exercise. Front Physiol. (2018) 9:1149. 10.3389/fphys.2018.01149

97.

Hou Z Qin X Hu Y Zhang X Li G Wu J et al Longterm exercise-derived exosomal miR-342-5p: a novel exerkine for cardioprotection. Circ Res. (2019) 124:1386–400. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314635

98.

Chaturvedi P Kalani A Medina I Familtseva A Tyagi SC . Cardiosome mediated regulation of MMP9 in diabetic heart: role of mir29b and mir455 in exercise. J Cell Mol Med. (2015) 19:2153–61. 10.1111/jcmm.12589

99.

Ke X Yang D Liang J Wang X Wu S Wang X et al Human endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes increase proliferation and angiogenesis in cardiac fibroblasts by promoting the mesenchymal-endothelial transition and reducing high mobility group box 1 protein B1 expression. DNA Cell Biol. (2017) 36:1018–28. 10.1089/dna.2017.3836

100.

Chen CW Wang LL Zaman S Gordon J Arisi MF Venkataraman CM et al Sustained release of endothelial progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles from shear-thinning hydrogels improves angiogenesis and promotes function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. (2018) 114:1029–40. 10.1093/cvr/cvy067

101.

Burger D Viñas JL Akbari S Dehak H Knoll W Gutsol A et al Human endothelial colony-forming cells protect against acute kidney injury: role of exosomes. Am J Pathol. (2015) 185:2309–23. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.04.010

102.

Wu K Yang Y Zhong Y Ammar HM Zhang P Guo R et al The effects of microvesicles on endothelial progenitor cells are compromised in type 2 diabetic patients via downregulation of the miR-126/VEGFR2 pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2016) 310:E828–37. 10.1152/ajpendo.00056.2016

103.

Zhang C Wang J Ma X Wang W Zhao B Chen Y et al ACE2-EPC-EXs protect ageing ECs against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury through the miR-18a/Nox2/ROS pathway. J Cell Mol Med. (2018) 22:1873–82. 10.1111/jcmm.13471

104.

Zhou Y Li P Goodwin AJ Cook JA Halushka PV Chang E et al Exosomes from endothelial progenitor cells improve the outcome of a murine model of sepsis. Mol Ther. (2018) 26:1375–84. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.020

105.

Munich S Sobo-Vujanovic A Buchser WJ Beer-Stolz D Vujanovic NL . Dendritic cell exosomes directly kill tumor cells and activate natural killer cells via TNF superfamily ligands. Oncoimmunology. (2012) 1:1074–83. 10.4161/onci.20897

106.

Tian T Zhu YL Hu FH Wang YY Huang NP Xiao ZD . Dynamics of exosome internalization and trafficking. J Cell Physiol. (2013) 228:1487–95. 10.1002/jcp.24304

107.

Gu S Zhang W Chen J Ma R Xiao X Ma X et al EPC-derived microvesicles protect cardiomyocytes from ang II-induced hypertrophy and apoptosis. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e85396. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085396

108.

Khalil H Kanisicak O Prasad V Correll RN Fu X Schips T et al Fibroblast-specific TGF-β-Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:3770–83. 10.1172/JCI94753

Summary

Keywords

exercise, exosomes, miR-126, cardiac fibrosis, TGF-β/Smad3

Citation

Fu G, Wang Z and Hu S (2024) Exercise improves cardiac fibrosis by stimulating the release of endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes and upregulating miR-126 expression. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1323329. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1323329

Received

02 January 2024

Accepted

18 April 2024

Published

09 May 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Diana S. Nascimento, Universidade do Porto, Portugal

Reviewed by

Vaibhav Deshmukh, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Yi Yang, Wuhan Sports University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Fu, Wang and Hu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Siyuan Hu husiyuan@hnucm.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.