Abstract

Critical care cardiology (CCC) in the modern era is shaped by a multitude of innovative treatment options and an increasingly complex, ageing patient population. Generating high-quality evidence for novel interventions and devices in an intensive care setting is exceptionally challenging. As a result, formulating the best possible therapeutic approach continues to rely predominantly on expert opinion and local standard operating procedures. Fostering the full potential of CCC and the maturation of the next generation of decision-makers in this field calls for an updated training concept, that encompasses the extensive knowledge and skills required to care for critically ill cardiac patients while remaining adaptable to the trainee’s individual career planning and existing educational programs. In the present manuscript, we suggest a standardized training phase in preparation of the first ICU rotation, propose a modular CCC core curriculum, and outline how training components could be conceptualized within three sub-specialization tracks for aspiring cardiac intensivists.

Introduction

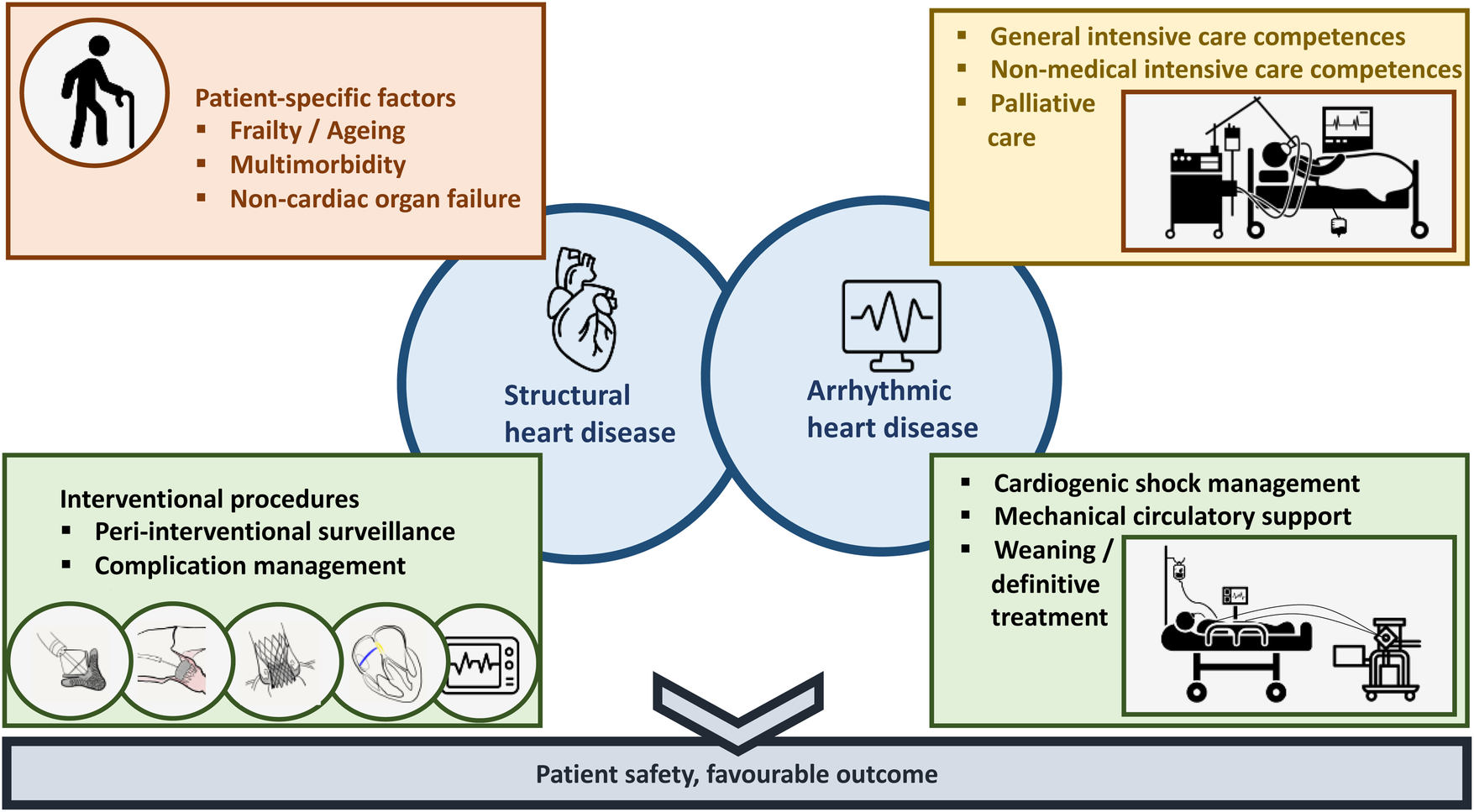

Critical care cardiology (CCC) in the modern era is shaped by a multitude of innovative treatment options and an increasingly complex, ageing patient population (Figure 1) (1–3). Generating high-quality evidence for novel interventions and devices in an intensive care setting is exceptionally challenging. As a result, formulating the best possible therapeutic approach continues to rely predominantly on expert opinion and local standard operating procedures. Fostering the full potential of CCC and the maturation of the next generation of decision-makers in this field calls for an updated training concept, that encompasses the extensive knowledge and skills required to care for critically ill cardiac patients while remaining adaptable to the trainee's individual career planning and existing educational programs (4–7). In the present manuscript, we suggest a standardized training phase in preparation of the first intensive care unit (ICU) rotation, propose a modular CCC core curriculum, and outline how training components could be conceptualized within three sub-specialization tracks for aspiring cardiac intensivists.

Figure 1

Challenges of contemporary critical care cardiology.

Preparation for critical care training

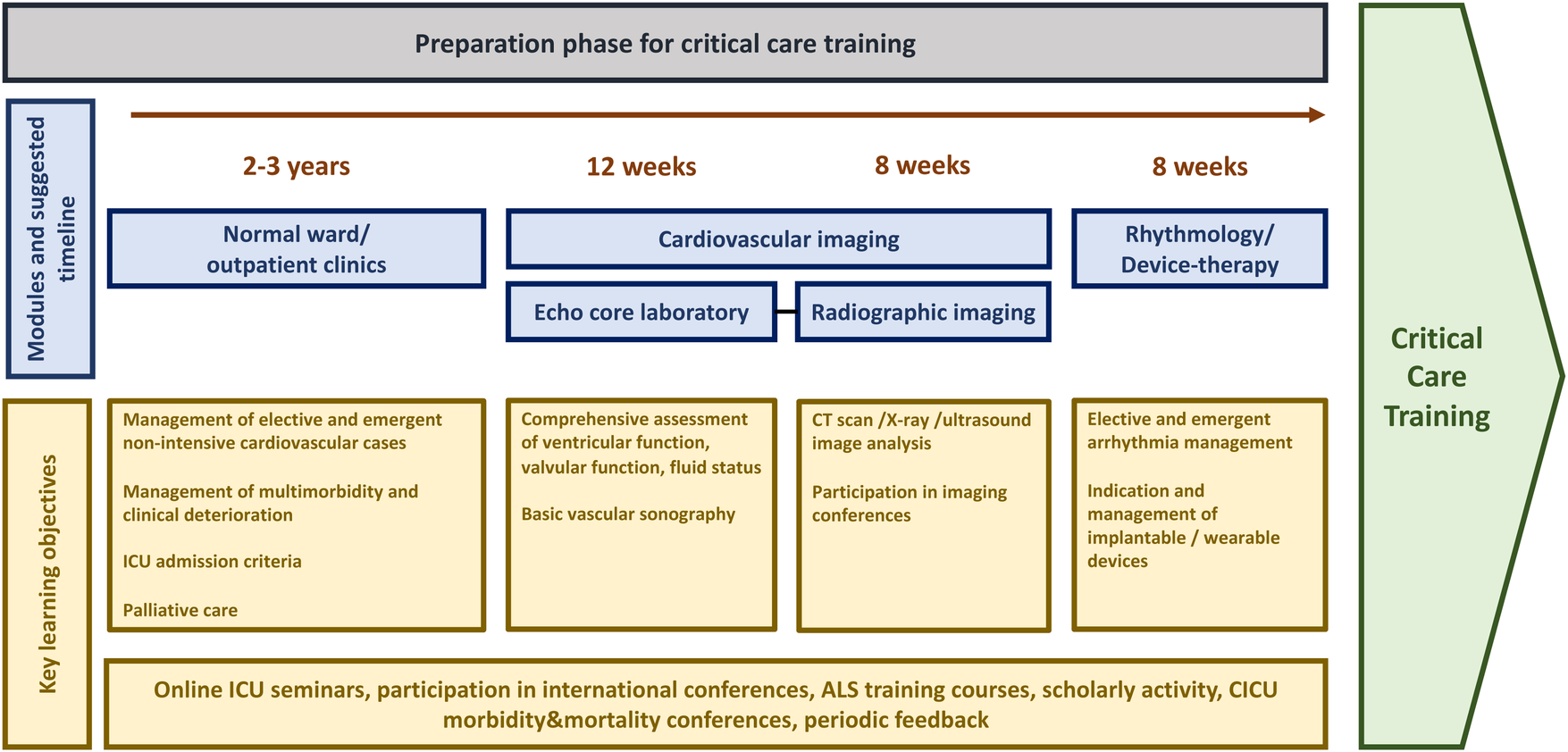

Cardiovascular fellows must be prepared for their first intensive care training phase in the best possible way during the preceding internal medicine/cardiovascular training program. Our exemplary proposal for a standardized pre-intensive care unit (pre-ICU) training comprises basic cardiovascular training elements with an intermediate period of focused practical skill acquisition and off-patient theoretical ICU preparation, leading up to the first supervised phases of intensive care training (Figure 2). Although many institutions may already have a pre-ICU training concept in place, we advocate for including standard prerequisites for a first ICU rotation into a comprehensive CCC training model.

Figure 2

Preparation for critical care training. ALS, advanced life support; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; CT, computed tomography; ICU, intensive care unit.

Trainees entering the internal medicine department usually spend 2–3 years primarily working in elective and emergency non-intensive care scenarios on a normal ward, outpatient clinic, or emergency department. Multimorbidity and clinical deterioration, however, may be encountered early on and offer learning opportunities in organ-specific disease management, patient selection for various procedures, ICU admission criteria, and palliative care. Thereafter, training programs should provide cardiovascular fellows scheduled for/interested in (cardiac) intensive care with the opportunity to train in a high-throughput echocardiography laboratory for at least twelve weeks. Valvular function analysis, comprehensive right and left ventricular assessment, and evaluation of fluid status and effusions should be trained extensively and under supervision of a senior clinician to allow for focussed investigation even in suboptimal conditions and emergency settings in the cardiac ICU. Crude assessment of peripheral vessels to exclude arterial occlusion, active access site bleeding or arteriovenous fistulas, as well as thromboembolic complications should be included within cardiovascular sonography training. Ideally, fellows gain additional experience in echocardiography for patients who underwent heart surgery, to increase their confidence in assessing surgically implanted valve and aortic prosthesis, left ventricular assist devices, and transplanted patients. Training in echocardiography today should be conceived within the broader field of cardiovascular imaging. Depending on the structure of imaging branches within the teaching institution, fellows should work with a cardiovascular imaging specialist for 8 weeks in full-time. Analysing computed tomography scans, x-ray images, and pulmonary ultrasound in conjunction with a concise thoracic imaging course and participation in clinical imaging conferences will enable fellows to understand basic algorithms of image reporting, scan for overt findings, and integrate these with information obtained by other imaging modalities.

Complementary time dedicated to electrophysiology and devices is highly recommended before the cardiac ICU rotation, as well. After an introduction into diagnostics and programming of pacemaker and implantable defibrillator systems by a senior fellow or specialized consultant, fellows should work on regular elective cases for at least 8 weeks. Ideally, their knowledge should be expanded by shadowing (internal and external) cardioversions, device implantations, and participating in consultations on the cardiac ICU, thereby progressing towards a deeper insight into emergency management of arrhythmias and prevention in high-risk settings. Furthermore, completion of an advanced life support (ALS) course (e.g., ALS course certified by the European Resuscitation Council or the American Heart Association) should be mandatory. Ideally, larger cardiac ICUs should qualify their own physician and non-physician advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) instructors and conduct multidisciplinary training courses for ACLS providers. For example, a 6-member course can consist of one interventional cardiologist, two cardiology fellows/trainees from cardiac ICU, two ICU nurses and one catheterization laboratory nurse. Such training can be extremely fruitful and important for team building in general and understanding of the roles taken by different team members/professions. Fellows should use this opportunity to refine their knowledge of emergency care algorithms and practice their leadership role in a protected environment with a benign feedback culture. This may already be expanded on by early participation in morbidity and mortality conferences, where potential pitfalls are discussed openly, and preventive measures are established.

An updated core curriculum for training in critical care cardiology

The 2015 COCATS 4 statement on Critical Care Cardiology Training (8) listed basic competences that should be acquired during a 3-year cardiovascular fellowship program (Level I training). In theory, fellows with a specific interest in CCC could satisfy optional training elements by extending their ICU exposure by 3–6 months during the standard fellowship period (Level II training). However, the definition of these elements remains vague owing to the limited experience with the suggested educational pathway. Advanced training modules for CCC sub-specialization are conceptualized within an additional 1-year fellowship program (Level III training). On behalf of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the 2014 Association for Acute CardioVascular Care (ACVC) Core Curriculum (9) also defined main objectives, knowledge, skills, and behaviours/attitudes across 20 key categories pertaining to acute cardiovascular diseases and other central didactic topics for CCC sub-specialization. To meet these training requirements, the ACVC stipulates at least month-long rotations in anaesthesia, respiratory medicine, and nephrology, in addition to a total of 18 months in a specialized cardiac ICU (6 months during cardiovascular fellowship and 12 months thereafter), as well as 3 months in a general medical ICU. While the curricula proposed by the ACVC, the international Competency Based Training programme in Intensive Care Medicine for Europe (CoBaTrICE) (10), and other committees, provide detailed prerequisites for independently managing (cardiac) ICU patients, there are no widely accepted, comprehensive standard curricula specifying how CCC training elements can be tailored to the various stages of a fellow's career.

In this chapter, we propose three sets of core training components (Tables 1–3), that have been compiled based on the abovementioned guideline recommendations, local training curricula at the authors respective institutions, and the collective opinion of CCC program directors, consultant critical care cardiologists, and cardiovascular fellows currently pursuing CCC training. While there is undoubtedly some overlap between the suggested categories, Tables 1–3 attempt to distinguish core elements of patient care, medical knowledge, practical skillset, competences in systems of care, and professionalism within basic level CCC training (Table 1), contrasting them with core competences in general intensive care medicine (Table 2), and advanced-level CCC training (Table 3).

Table 1

| Medical knowledge and skillset |

|---|

Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, and basic treatment options of cardiogenic shock and associated syndromes depending on different underlying aetiologies:

|

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, basic treatment options, and outcomes in patients with fulminant infective endocarditis |

Clinical pharmacology focussing on indications, contraindications, pharmacodynamics, and associated risks of:

|

Basic understanding of indications, contraindications, and associated risks of interventional and surgical cardiac procedures:

|

| Indication for heart transplantation, basic understanding of immunosuppressive treatment |

| Assessment and general management of post-operative patients |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, basic treatment options, and outcomes of acute neurologic disorders |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, basic treatment options, and outcomes of acute renal, acid-base, and electrolyte disorders |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, basic treatment options, and outcomes of acute gastrointestinal disorders |

| Detection and management of peripheral and abdominal compartment syndromes |

| Patient care |

| Structured assessment of medical history and physical examination in an intensive care setting |

| Basic assessment of hemodynamic instability and respiratory dysfunction |

| Performing advanced cardiac life support according to standard algorithms |

| Basic understanding of post-resuscitation care |

| Understanding of emergency antiarrhythmic treatment options |

| Indication and interpretation of non-invasive and invasive hemodynamic monitoring |

| Indication and interpretation of laboratory testing including blood gas analysis |

| Management of hypertensive emergency/urgency |

| Indication and interpretation of radiographic imaging in liaison with imaging specialists |

| Indication for and basic interpretation of diagnostic left/right heart catheterization |

| Sedation management, analgesia, and neuromonitoring |

| Comprehensive fluid management |

| Management of bleeding or thromboembolic events |

| Management of hyperthermia, infection, and sepsis in liaison with microbiology specialists |

| Management of acid-base disorders |

| Comprehensive management of nutrition |

| Basic understanding of indication, contraindication, and associated risks of pharmacological and mechanical circulatory support options |

| Indication, contraindication, and associated risks of non-invasive and invasive respiratory support, basic weaning algorithms, indication of tracheostomy |

| Diagnostic criteria and management of acute kidney injury, indications, contraindications, and associated risks of renal replacement therapy |

| Prophylaxis and basic management of bleeding and thromboembolic complications |

| Management of multimorbid and elderly patients |

| Understanding principles of palliative care |

| Procedural skills |

| Insertion of arterial and central venous lines including large-bore catheters for renal replacement therapy |

| Performing cardioversion, defibrillation, and ventricular overdrive pacing |

| Transvenous pacemaker insertion, performing transthoracic cardiac pacing |

| Performing point-of-care echocardiography |

| Echocardiographic assessment of ventricular function, valvular function, and pericardial effusion |

| Basic sonographic assessment of vascular access sites, lungs, pleura, abdominal organs, and free abdominal fluid |

| Safe administration of blood products according to standard algorithms |

| Performing endotracheal intubation |

| Performing thoracocentesis and paracentesis |

| Placement of nasogastric tube |

| Obtaining appropriate microbiological samples |

| Performing basic vascular ultrasound |

| Transportation of stable patients outside the cardiac ICU |

| System of care competences |

| Understanding ICU admission criteria |

| Working in a multidisciplinary environment |

| Participation in M&M conferences |

| Participation in quality of care and safety training |

| Participation in institutional infection control and isolation training |

| Professionalism |

| Respectful interaction with all ICU team members |

| Demonstrating commitment to high-quality care |

| Self-reflection regarding the limitations of own knowledge and skill |

| Prioritizing and organizing clinical responsibilities |

| Performing adequate documentation |

| Communicating goals of care to patient and family of different backgrounds |

| Sensitivity to patient's wishes and spiritual/cultural background, particularly in end-of-life decisions |

| Obtaining informed consent |

| Respecting the patient's privacy and autonomy |

| Addressing psychosocial issues of patients and families |

| Understanding ethical/legal implications of withdrawal of care |

| Engaging in continuous self-directed learning through seminars, web-based/simulation-based training programs, and teaching sessions embedded in scientific conferences |

Basic level core competences in critical care cardiology.

ICU, intensive care unit; M&M, morbidity and mortality; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 2

| Medical knowledge and skillset |

|---|

| Advanced assessment and management of post-operative patients |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, hemodynamic implications, differential diagnoses, treatment options, and outcomes of anaphylactic, septic, hypovolemic, haemorrhagic, and obstructive shock |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, treatment options, and outcomes of multi-organ dysfunction |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, treatment options, and outcomes of acute respiratory disorders; indications, contraindications, and associated risks of VV-ECMO therapy |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, treatment options, and outcomes of acute endocrine disorders |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, treatment options, and outcomes of acute intoxication |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, treatment options, and outcomes of acute peripartum complications |

| Assessment and general management of trauma patients |

| Patient care |

| Advanced management of resuscitation |

| Advanced circulatory management, optimization of preload and afterload using different medical options, balanced fluid management, diuretics, and renal replacement therapy |

| Interpretation of complex electrocardiography findings |

| Advanced management of respiratory support including different ventilation modalities and (prolonged) weaning algorithms |

| Advanced anti-microbial management, antibiotic stewardship, particularly in patients with intrinsic or acquired immunodeficiencies |

| Integrating multiple imaging modalities into clinical context |

| Management of high-volume fluid and blood transfusions and associated risks |

| Interpretation of brain death diagnostics, assessment of organ donation criteria |

| Participation in multidisciplinary withdrawal-of-care decisions |

| Advanced management and prevention of pain and psychological distress |

| Procedural skills |

| Performing advanced thoracic ultrasound |

| Performing advanced abdominal ultrasound |

| Performing lumbar puncture |

| Performing tracheotomy |

| Performing bedside fiberoptic laryngotracheobronchoscopy |

| System of care competences |

| Engaging in clinical consultation |

| Coordinating referrals and patient triage |

| Management of retrieval and transfer of ICU patients from other units/hospitals |

| Understanding ICU discharge criteria |

| Engaging in teaching activity for junior fellows |

| Critical application of (inter)national and local guidelines and protocols |

| Professionalism |

| Assuming a leadership role and striving for holistic patient care |

| Promoting effective multidisciplinary team-working |

| Communication of complex case summaries to team members and other health care professionals |

| Implementation of new guidelines and scientific papers into clinical practice |

| Identifying potential risks for ICU staff and promoting adequate safety measures |

| Giving structured feedback to ICU team members |

| Establishing a constructive culture of dealing with medical errors |

| Evaluating cost-effectiveness of advanced treatment options |

| Participation in international conferences |

Core competences in general intensive care medicine.

ICU, intensive care unit; VV-ECMO, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 3

| Medical knowledge and skillset |

|---|

| In-depth knowledge on pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, advanced treatment options, and outcomes of structural heart diseases and cardiomyopathies |

| In-depth knowledge on pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, advanced treatment options, and outcomes of primary arrhythmic disorders |

| In-depth knowledge on pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, advanced treatment options, and outcomes of left-ventricular, right-ventricular, and bi-ventricular cardiogenic shock, associated syndromes, and underlying aetiologies |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, treatment options, and outcomes of cardiogenic shock and other critical care scenarios in patients with inherited heart diseases (i.e. hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, Long-QT-syndrome) |

| Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, treatment options, and outcomes of cardiogenic shock and other critical care scenarios in special patient populations (i.e. HIV-positive patients, pregnant women, patients after heart transplantation, patients with left ventricular assist device, pulmonary hypertension, Takotsubo-cardiomyopathy, oncologic patients) |

| In-depth knowledge of indications, contraindications, and associated risks of the full spectrum of interventional cardiac treatment options in acute high-risk settings |

Indications, contraindications, and associated risks of mechanical circulatory support for patients in advanced/refractory cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest, i.e.:

|

| Indications, hemodynamic implications, contraindications, and associated risks of different LV-venting modalities during VA-ECMO therapy |

| Assessment and management of patients admitted to the cardiac ICU after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| Patient care |

| Assuming leadership role during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and integrating emergency diagnostics to formulate management plan |

| Management of patients receiving complex interventional procedures including coronary interventions, valvular interventions, and device implantation |

| Detection and management of multi-organ failure |

| Indication and interpretation of advanced hemodynamic monitoring (i.e. PICCO, thermodilution) |

| Indication for and comprehensive interpretation of diagnostic left- and right heart catheterization as well as various radiographic imaging modalities |

| Advanced management of patients receiving MCS devices including VA-ECMO, Tandem-Heart, IABP, Impella |

| Management of patients in advanced heart failure stages including eligibility criteria for left ventricular assist device implantation and high-urgency listing for heart transplantation |

| Emergency assessment, post-operative care, and complication management of patients with durable left ventricular devices |

| Advanced post-resuscitation care including targeted temperature management |

| Procedural skills |

| Performing advanced point-of-care echocardiography |

| Performing bedside transoesophageal echocardiography |

| Performing advanced vascular ultrasound |

| Performing pericardiocentesis |

| Comprehensive assessment of arrhythmias recorded by implantable cardiac devices, function assessment and adjustment of the settings of bradycardia pacemakers as well as anti-tachycardic function of implantable cardioverter defibrillators |

| Cannulation, setup, maintenance, and decannulation of VA-ECMO and Tandem-Heart devices |

| Insertion, maintenance, and explantation of IABP and Impella devices (excluding surgical implantation and explantation of Impella 5.0 and 5.5) |

| System of care competences |

| Coordinating and leading multidisciplinary daily rounds |

| Coordinating and supervising intra- and interhospital transfers of cardiac ICU patients |

| Initiating and moderating M&M conferences |

| Assessment of mortality and other relevant outcome variables using standard risk prediction models and (inter)national registries |

| Professionalism |

| Gradually assuming responsibility for the full spectrum of CCC patients |

| Promoting efficiency and effectiveness of patient care within the CCC team |

| Shared decision making with patients, families, and other health care professionals |

| Engaging in teaching and continued scholarly activity |

Advanced level core competences in critical care cardiology.

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; M&M, morbidity and mortality; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PICCO, pulse index continuous cardiac output; VA-ECMO, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 1 outlines competences that are needed for the trainee's first integration into a cardiac ICU team, representing the initial point of contact with critically ill cardiac patients. Irrespective of their chosen sub-specialty, these core CCC training elements are relevant to all cardiovascular fellows for gaining a full understanding of cardiac emergency care. Table 2 depicts a broader set of core competences in intensive care medicine, focussing on the management of a greater spectrum of acute medical illnesses, trauma, and post-operative care as well as a broader practical skillset and leadership qualities essential for assuming responsibility for patients in a general (surgical or medical) intensive care setting. Lastly, specific training elements for specialization in CCC are presented in Table 3. This set of core training components is incomplete by nature, and the allocation of individual elements warrants further discussion. Nevertheless, the suggested framework may function as a handrail for the development of CCC sub-specialization programs and for cardiovascular and intensive care medicine fellows aspiring to advance in this direction.

Structured assessment of the trainee's clinical performance is essential to boost compliance with educational benchmarks and ensure the highest standards of training and professional development. Personal evaluation should also consider scientific achievements and continued assessment of quality of care after specialization. Beyond that, the need for quality assessment extends to the specialization program itself. Intensive care societies and program supervisors should strive for establishing key performance indicators, such as the number of training positions per year, the number of graduates per year, dropout rate, and measures of flexibility, as well as indicators of institutional conditions, that help identify the need for structural optimization, and improve comparability and measurability of training outcomes on a national/international level.

Sub-specialization pathways and institutional preconditions

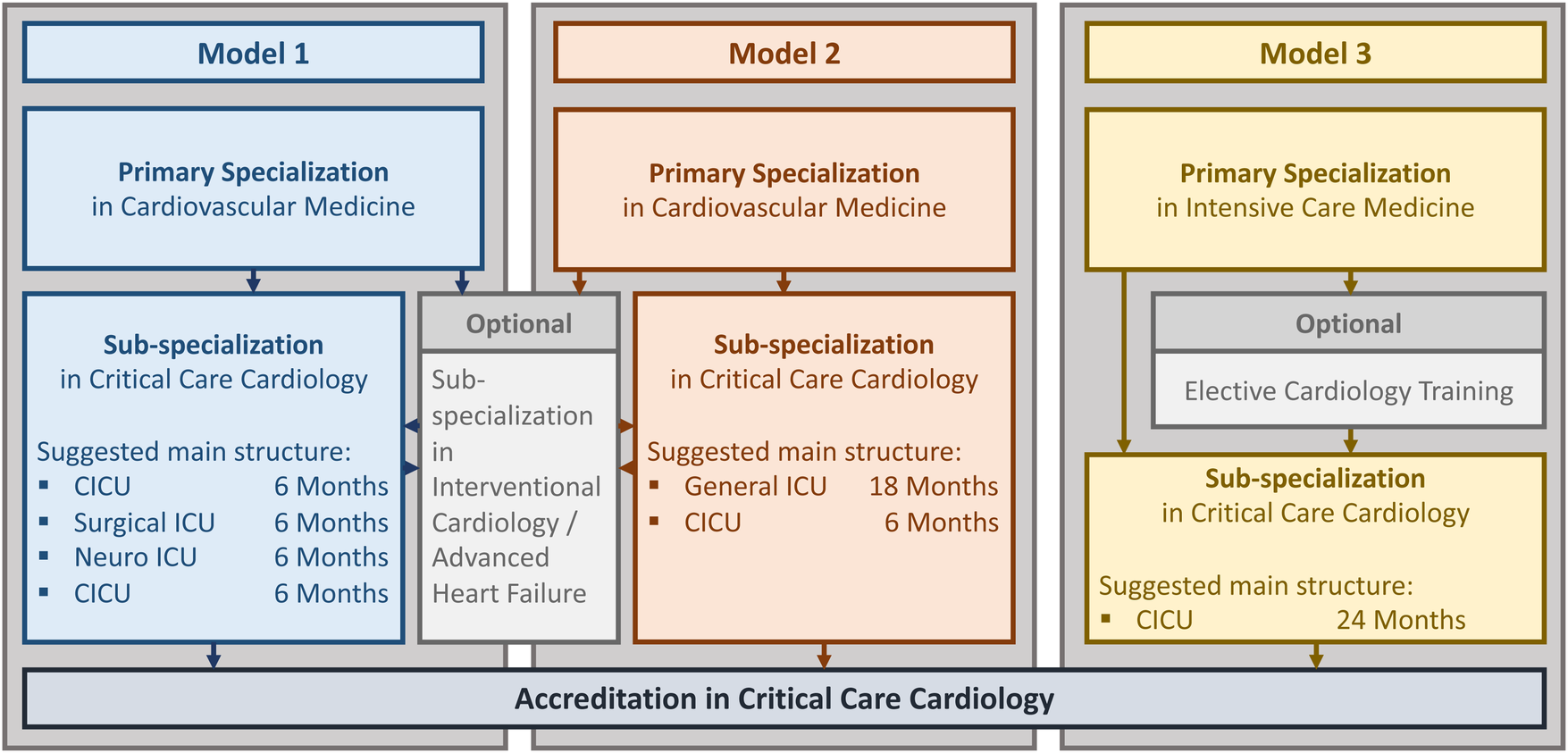

The challenge of defining training targets is not the only issue at hand. Educational guideline committees and program supervisors must also navigate the delicate balance between incorporating the evolving skillset and knowledge in CCC and minimizing specialization durations. Inspired by training pathways at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) hospital and other international accreditation tracks, we propose three adaptable models for sub-specialization in CCC (Figure 3) in the following section (6, 11–13).

Figure 3

Sub-specialization tracks in critical care cardiology. CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; ICU, intensive care unit.

Models 1 and 2 are based on completion of a fellowship in general cardiovascular medicine including at least 6 months of ICU training, which reflects the application requirements for CCC sub-specialization set forth by the ACVC. In conjunction with the knowledge acquired during rotations in cardiac imaging, electrophysiology, and to the catheterization laboratory, the content of Table 1 represents key milestones for the cardiovascular fellow's integration into the cardiac ICU roster as a junior team member. For example, trainees must gain a common understanding of cardiac interventions that enables them to systematically screen for and manage complications on a basic level (5, 14). Also, the hemodynamic principles of cardiogenic shock along with treatment concepts and underlying diseases, as well as general handling of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices are nowadays core elements of training in cardiovascular medicine (14). By contrast, the in-depth knowledge on indications and risks of interventional cardiac procedures, such as emergent coronary interventions, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), interventional mitral valve repair, mechanical thrombectomy, implantation of transcatheter closure devices, and ablation of ventricular tachycardias, that are required for decision-making in high-risk patients with hemodynamic instability go beyond what can be expected from early career fellows (15–20). Similarly, comprehensive management of cardiogenic shock patients including advanced understanding of hemodynamics and device-based treatment options requires a profound familiarity with current evidence on MCS and an advanced skillset for emergent troubleshooting in case of deterioration or device-associated complications (21–23). Models 1 and 2 envision the highest level of qualification (Table 3) to be acquired during an additional 12-month (Model 1) or 6-month (Model 2) cardiac ICU rotation as part of the CCC sub-specialization program. The concept of Model 1 further allows for a 6-month rotation in a surgical and neurologic ICU, respectively, to extend the trainee's general intensive care knowledge and skillset (Table 2). By contrast, formal training time in a general ICU according to Model 2 would be an 18-month period followed by 6 months of time dedicated to the cardiac ICU. When the 24-month sub-specialization program is completed successfully, trainees should have gained the knowledge and experience needed to act independently as a consultant cardiac intensivist and assume a leadership role within the multidisciplinary cardiac ICU team. In theory, programs adopting Models 1 or 2 could integrate advanced CCC training content (Table 3) with other advanced fellowship programs, e.g., interventional cardiology or heart failure (24). Compared to CCC, heart failure sub-specialization training typically covers additional aspects of long-term patient management, such as evaluation for heart transplantation or ventricular assist devices, and long-term follow-up. Combining training in CCC and heart failure could leverage the significant overlap in theoretical knowledge and practical skillset between these sub-specialities while strengthening the candidate's abilities to develop individual treatment concepts for the acute, intermediate, and chronic phase.

The structure of Model 3 differs from Models 1 and 2 regarding the basic clinical training that precedes sub-specialization in CCC. This pathway features a fellowship in general intensive care medicine, which is often designed in conjunction with training in anaesthesiology and pulmonary medicine, followed by 24 months of time dedicated to sub-specialization in CCC. For example, the current stage 1 postgraduate program in intensive care medicine in the United Kingdom spans a total of 4 years subdivided into training blocks in anaesthesiology, internal medicine, and emergency care (25). While this type of initial clinical exposure strengthens core qualifications in intensive care such as endotracheal intubation and ventilation management (Table 2, elements of Table 1), integrating the content of general cardiology training, which is indispensable for managing cardiac ICU patients, is more challenging. Within their internal medical rotations, trainees should focus on acquiring basic knowledge on the management of patients with structural heart disease and arrhythmias. Working in emergency care and in cardiac anaesthesiology provides learning opportunities about acute cardiovascular illnesses and treatment algorithms and could further improve the fellow's ability to assess arrhythmias and perform transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography. Program directors should encourage fellows interested in CCC to seek mentorship from within the cardiovascular department and engage in extra-curricular interdisciplinary seminars. Nonetheless, sub-specialization programs designed for candidates holding board certification in intensive care medicine must be adaptable to accommodate the trainee's individual level of experience in the field of cardiovascular medicine. Model 3 suggests a minimum of 24 months spent in the cardiac ICU, which may be complemented by rotations to the catheterization laboratory or heart failure unit. This approach could allow for a personalized roadmap leading to the acquisition of core competences in basic and advanced CCC (Table 3, elements of Table 1).

All three models provide a framework for integrating the extensive training content into personalized sub-specialization tracks, which potentially allow for interruption of training, rotations/transitions to non-tertiary institutions, and hybridization with other sub-specialization programs. Generally, many crucial aspects of training are contingent on team composition and organization of the CCC program established by the teaching institution. To ensure patient safety and efficacy of training, CCC sub-specialization programs should be situated in accredited tertiary hospitals and overseen by an experienced cardiac intensivist with the requisite national teaching qualification. Integrating specialists in interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery, electrophysiology, cardiac imaging, microbiology, and pharmacology into recurrent meetings and cardiac ICU rounds presents trainees with opportunities to gain a more comprehensive understanding of multidisciplinary treatment concepts and liaise with experts to enhance their skillset. By promoting scientific endeavours, institutions will contribute to academic progress and foster evidence-based medicine as well as life-long learning.

Conclusion

To keep pace with the rapidly changing field of CCC, intensive care societies should establish an updated training concept, that encompasses core training elements spanning all career stages, different educational pathways, and formal institutional standards. Harmonizing regional training models into a comprehensive educational framework can provide valuable guidance for program directors and help fulfilling the needs of future critical care cardiologists. Ultimately, the versatility and holistic nature of training will play a pivotal role in shaping the success of the next generation of experts in the field as they work toward enhancing patient safety and achieving favourable outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

All ethical standards were met in writing and submitting this article.

Author contributions

LB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DR: Writing – review & editing. IS: Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – review & editing. LS: Writing – review & editing. PS: Writing – review & editing. CS: Writing – review & editing. BS: Writing – review & editing. FH: Writing – review & editing. PS: Writing – review & editing. NM: Writing – review & editing. CA: Writing – review & editing. DH: Writing – review & editing. TG: Writing – review & editing. HB: Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – review & editing. RR: Writing – review & editing. WS: Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – review & editing. MP: Writing – review & editing. PL: Writing – review & editing. SZ: Writing – review & editing. DW: Writing – review & editing. UZ: Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – review & editing. HT: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

PL received speaker honoraria and consulting fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Pfizer, Edwards Lifesciences, and research honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences outside the submitted work.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Katz JN Minder M Olenchock B Price S Goldfarb M Washam JB et al The genesis, maturation, and future of critical care cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 68(1):67–79. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.036

2.

Bonnefoy-Cudraz E Bueno H Casella G De Maria E Fitzsimons D Halvorsen S et al Editor’s choice—acute cardiovascular care association position paper on intensive cardiovascular care units: an update on their definition, structure, organisation and function. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. (2018) 7:80–95. 10.1177/2048872617724269

3.

Morrow DA Fang JC Fintel DJ Granger CB Katz JN Kushner FG et al Evolution of critical care cardiology: transformation of the cardiovascular intensive care unit and the emerging need for new medical staffing and training models. Circulation. (2012) 126:1408–28. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826890b0

4.

Binzenhöfer L Thiele H Lüsebrink E . Training in critical care cardiology: making the case for a standardized core curriculum. Crit Care. (2023) 27:380. 10.1186/s13054-023-04649-6

5.

Lüsebrink E Kellnar A Scherer C Krieg K Orban M Petzold T et al New challenges in cardiac intensive care units. Clin Res Cardiol. (2021) 110:1369–79. 10.1007/s00392-021-01869-0

6.

Geller BJ Fleitman J Sinha SS . Critical care cardiology: implementing a training paradigm. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72:1171–5. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.024

7.

Panhwar MS Chatterjee S Kalra A . Training the critical care cardiologists of the future: an interventional cardiology critical care pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75:2984–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.010

8.

O’Gara PT Adams JE 3rd Drazner MH Indik JH Kirtane AJ Klarich KW et al COCATS 4 task force 13: training in critical care cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 65:1877–86. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.027

9.

Price S Heras M Barabes J Gevaert S Raake P Tio R et al Acute Cardiovascular Care Association Core Curriculum. Acute Cardiovascular Care Association of the ESC 2014; published online Nov.

10.

European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. CoBaTrICE Syllabus. Brussels: European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) (2021).

11.

Buerke M Janssens U Prondzinsky R Ebelt H Post F Giannitsis E et al Curriculum cardiovascular intensive care and emergency medicine (K-IN): working group and task force for cardiovascular intensive and emergency medicine of the German cardiac society. Kardiologe. (2021) 15:585–94. 10.1007/s12181-021-00505-5

12.

John S Riessen R Karagiannidis C Janssens U Busch HJ Kochanek M et al Core curriculum medical intensive care medicine of the German society of medical intensive care and emergency medicine (DGIIN). Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. (2021) 116(Suppl 1):1–45. 10.1007/s00063-020-00765-1

13.

Ramjee V . Cardiac intensivism: a view from a fellow-in-training. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64:949–52. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.019

14.

Tanner FC Brooks N Fox KF Gonçalves L Kearney P Michalis L et al ESC core curriculum for the cardiologist. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:3605–92. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa641

15.

Hochman JS Sleeper LA Webb JG Sanborn TA White HD Talley JD et al Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. (1999) 341:625–34. 10.1056/NEJM199908263410901

16.

Kolte D Khera S Vemulapalli S Dai D Heo S Goldsweig AM et al Outcomes following urgent/emergent transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11:1175–85. 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.03.002

17.

Kovach CP Bell S Kataruka A Reisman M Don C . Outcomes of urgent/emergent transcatheter mitral valve repair (MitraClip): a single center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 97(3):E402–10. 10.1002/ccd.29084

18.

Giri J Sista AK Weinberg I Kearon C Kumbhani DJ Desai ND et al Interventional therapies for acute pulmonary embolism: current status and principles for the development of novel evidence: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2019) 140(20):e774–e801. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000707

19.

Avgerinos ED Jaber W Lacomis J Markel K McDaniel M Rivera-Lebron BN et al Randomized trial comparing standard versus ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis for submassive pulmonary embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(12):1364–73. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.04.049. Erratum in: JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(19):2194. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC9057455

20.

Ballout JA Wazni OM Tarakji KG Saliba WI Kanj M Diab M et al Catheter ablation in patients with cardiogenic shock and refractory ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2020) 13(5):e007669. 10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007669

21.

Lüsebrink E Binzenhöfer L Kellnar A Müller C Scherer C Schrage B et al Venting during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Clin Res Cardiol. (2023) 112:464–505. 10.1007/s00392-022-02069-0

22.

Thiele H Zeymer U Akin I Behnes M Rassaf T Mahabadi AA et al Extracorporeal life support in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:1286–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa2307227

23.

Lüsebrink E Kellnar A Krieg K Binzenhöfer L Scherer C Zimmer S et al Percutaneous transvalvular microaxial flow pump support in cardiology. Circulation. (2022) 145:1254–84. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.058229

24.

Vallabhajosyula S Kapur NK Dunlay SM . Hybrid training in acute cardiovascular care: the next frontier for the care of Complex cardiac patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2020) 13:E006507. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006507

25.

The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Curriculum for a CCT in Intensive Care Medicine. London: The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Churchill House (2019).

Summary

Keywords

critical care cardiology, training concept, core curriculum, intensive care unit, cardiovascular fellows, fellows in training

Citation

Binzenhöfer L, Gade N, Roden D, Saleh I, Lanz H, Sierra LV, Seifert P, Scherer C, Schrage B, Haertel F, Spieth PM, Mangner N, Adler C, Hoyer D, Graf T, Billig H, Salem M, Rangel RH, Speidl WS, Hagl C, Hausleiter J, Massberg S, Preusch M, Meder B, Leistner DM, Luedike P, Rassaf T, Zimmer S, Westermann D, Zeymer U, Schäfer A, Thiele H and Lüsebrink E (2024) A contemporary training concept in critical care cardiology. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1351633. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1351633

Received

06 December 2023

Accepted

23 February 2024

Published

14 March 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Ruth Heying, University Hospital Leuven, Belgium

Reviewed by

Saraschandra Vallabhajosyula, Brown University, United States

David A. Baran, Cleveland Clinic Florida, United States

Connor O'Brien, University of California, San Francisco, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Binzenhöfer, Gade, Roden, Saleh, Lanz, Sierra, Seifert, Scherer, Schrage, Haertel, Spieth, Mangner, Adler, Hoyer, Graf, Billig, Salem, Rangel, Speidl, Hagl, Hausleiter, Massberg, Preusch, Meder, Leistner, Luedike, Rassaf, Zimmer, Westermann, Zeymer, Schäfer, Thiele and Lüsebrink.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Enzo Lüsebrink e.luesebrink@med.uni-muenchen.de

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.