Abstract

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a polymorphic myocardial disease occurring late during pregnancy or early after delivery. While reduced systolic function and heart failure (HF) symptoms have been widely described, there is still a lack of reports about the arrhythmic manifestations of the disease. Most importantly, a broad range of unidentified pre-existing conditions, which may be missed by general practitioners and gynecologists, must be considered in differential diagnosis. The issue is relevant since some arrhythmias are associated to sudden cardiac death occurring in young patients, and the overall risk does not cease during the early postpartum period. This is why multimodality diagnostic workup and multidisciplinary management are highly suggested for these patients. We reported a series of 16 patients diagnosed with PPCM following arrhythmic clinical presentation. Both inpatients and outpatients were identified retrospectively. We performed several tests to identify the arrhythmic phenomena, inflammation and fibrosis presence. Cardiomyopathies phenotypes were reclassified in compliance with the updated ESC guidelines recommendations. Arrhythmias were documented in all the patients during the first cardiological assessment. PVC were the most common recorder arrhythmias, followed by VF, NSVT, AF, CSD.

Introduction

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a rare myocardial disease occurring during late pregnancy or early postpartum period (1). Because of the frequent finding of reduced systolic dysfunction and heart failure (HF), PPCM is currently classified as a variant of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (2). Consistently, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) (3, 4) has adopted the revised version of the very earliest proposed diagnostic criteria (5, 6), namely: (1) development of HF from one month before delivery to the following five months—a narrow timeframe, which has been subsequently extended (1); (2) absence of an evident alternative cause other than pregnancy; (3) absence of known heart diseases diagnosed before the pregnancy; (4) LV ejection fraction (LVEF) < 45%, as defined by transthoracic echocardiogram.

While the DCM phenotype and associated mechanical manifestations are widely characterized in PPCM, to date the arrhythmic presentation of the disease is still under-investigated. In fact, although a broad range of tachy- and brady-arrhythmias have been described in patients with PPCM (1), most of the current knowledge relies on case reports and small-sized studies. The aim of the current review is: (1) to describe a series of patients evaluated for clinically-suspected PPCM following arrhythmic presentation; (2) to summarize the status of the art about the arrhythmic manifestations of PPCM.

Case series

Methods

We present a series of n = 16 consecutive patients evaluated for clinically-suspected PPCM at two centers specialized in arrhythmia management. Both inpatients and outpatients were identified retrospectively, based on the following screening criteria: 1) female sex in childbearing age (15 to 45 years); 2) first clinical presentation with arrhythmias (including bradyarrhythmias and either supraventricular or ventricular tachyarrhythmias), as documented either during pregnancy or in the 6 months after delivery; and: 3) lack of known cardiological history beforhead. In addition, in keeping with the local standard of care, multimodal diagnostic workup and multidisciplinary management were applied, respectively, to clarify the underlying diagnosis and enable patient-tailored treatment choices. In detail, on top of laboratory exams, transthoracic echocardiogram, 12-lead ECG and inhospital telemonitoring/outpatient Holter ECG monitoring, advanced diagnostic workup included one or more of the following exams: cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and additional sequences to investigate structural diseases (T2-weighted sequences, fat-sat sequences, parametric mapping whenever applicable); genetic test by next-generation sequencing to screen for cardiomyopathic gene variants (CGVs); histology exams, including hematoxylin-eosin and trichrome assays to detect myocardial inflammation and fibrosis, as well as immunohistochemistry analysis to further characterize the inflammatory infiltrates; 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan, to screen for cardiac sarcoidosis in suspected cases; and electroanatomical map (EAM), to characterize the arrhythmogenic substrates in patients with clinical indication to catheter ablation. Cardiomyopathic phenotypes were reclassified in compliance with the updated (2023) ESC guideline recommendations (7).

But for the restrictions applied for pregnancy and lactation timeframes, all patients were offered optimal guideline-based medical therapy. Implantation of cardiac devices, as well as catheter ablation of arrhythmias, were in keeping with the current recommendations. At both centers, regular follow-up took place at dedicated outpatient settings for cardiomyopathy. The content of this report is fully compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients signed informed consent to be enrolled in a research registry.

SPSS Version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as mean or median with standard deviation (SD) or range, depending on the distribution of data, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk's test. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages. Because of the small sample size and the absence of a prespecified study design, no statistical models were introduced for risk stratification, and no p-values were presented for comparison between groups.

Results: clinical presentation

The series includes 16 women (mean age 31 years, range 24–36; 88% Caucasian), of whom 14 (88%) presented with symptoms, and were managed as inpatients. In detail, their clinical presentation was: cardiocirculatory arrest (n = 1), syncope (n = 1), palpitation (n = 5), dyspnea (n = 4), asthenia (n = 2), and chest pain (n = 1). The first clinical manifestation occurred during the third trimester of pregnancy in n = 3 cases (19%), and after delivery (median 4, range 1–6 months) in the remaining 13 (81%).

The key clinical features of the case series are show in Table 1. Obstetric history was unremarkable, except for two cases of twin pregnancy (13%, including one case occurring following in-vitro fertilization). No other patients had infertility or history of radiation exposure. The cardiovascular risk profile of the sample was generally low: in particular, there were no diabetic patients, and hypertension with criteria for preeclampsia was found in one single case (6%). Also, only two patients (13%) reported family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD) or cardiomyopathy.

Table 1

| ID | Age (year) | Obstetric history | Presentation | Rhythm /conduction disorders | Phenotype | LVEF (%) | Diagnostic workup | Final diagnosis | Cardiac device | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | 35 | Uncomplicated VD | Dyspnea | PVC, AF, RBBB | DCM | 20 | HE, GT | Undefined—class 3 variant in VCL gene | ICD (primary prevention) | Losartan | HTx |

| P02 | 33 | Uncomplicated VD | Dyspnea | VT, incomplete RBBB, epsilon waves | DCM/ACM | 25 | GT | Genetic—class 5 variant in TTN gene | None (ICD refused) | None (refused) | SCD |

| P03 | 36 | Uncomplicated CD | Dyspnea | NSVT, PVC | DCM | 55 | CMR, HE | Systemic sclerosis | None | Ramipril, bisoprolol, prednisone, MMF | Uneventful |

| P04 | 24 | Uncomplicated VD | Chest pain | PVC | NDLVC | 65 | CMR, GT | Genetic—class 4 variant in DSP gene | ILR | Metoprolol | Uneventful |

| P05 | 30 | Uncomplicated VD | Palpitation | NSVT, PVC | NDLVC | 25 | CMR, HE, EAM | Inflammatory (lymphocytic, virus-negative) | None | Losartan, propafenone, anakinra | PVC catheter ablation, LVEF recovery up to 58% |

| P06 | 26 | Uncomplicated VD | Syncope | VT, NSVT, PVC, AF | DCM | 30 | CMR, EAM | Undefined (fibrotic) | ICD (secondary prevention) | ARNI, sotalol | AF catheter ablation, Mitraclip, LVEF recovery up to 48% |

| P07 | 33 | Uncomplicated VD | Dyspnea | PVC, LBBB | DCM | 32 | GT | Undefined—class 3 variant in FLNC gene | CRT-D (primary prevention) | Bisoprolol | Uneventful |

| P08 | 24 | Uncomplicated VD | Palpitation | PVC, WPW | Normal | 60 | CMR, EAM, GT | Arrhythmogenic mitral valve prolapse—class 3 variant in LAMA4 gene | ICD (VF induced by PVS) | Fecainide | WPW catheter ablation; ablation of trigger PVC |

| P09 | 29 | Twin pregnancy, UD | Asymptomatic | NSVT, PVC | NDLVC | 59 | CMR, HE, PET, EAM | Inflammatory (lymphocytic, virus-negative) | None | Sotalol, prednisone, azathioprine | PVC catheter ablation |

| P10 | 27 | UD, premature | Palpitation, chest pain | PVC | NDLVC | 59 | CMR, HE | Inflammatory (lymphocytic, low-dose parvovirus B19) | ILR | Ramipril, bisoprolol, prednisone, azathioprine | Uneventful |

| P11 | 29 | Twin pregnancy (ICSI), uncomplicated VD | Asymptomatic | NSVT, PVC | NDLVC | 44 | CMR, HE, EAM, GT | Undefined—class 3 variant in DSP gene | ICD (fast NSVT, extensive LGE, patient preference) | Metoprolol | ICD shock, VT catheter ablation, LVEF recovery up to 55% |

| P12 | 36 | Uncomplicated VD | Palpitation | NSVT, PVC | NDLVC | 60 | CMR, EAM, GT | Inflammatory—class 3 variants in DES, FLNC, and DMD genes | ICD (fast NSVT, extensive LGE, genetic test) | Metoprolol, spironolactone, bromocriptin | PVC catheter ablation |

| P13 | 32 | Uncomplicated CD | CCA | VF, PVC, WPW | Normal | 50 | EAM, GT | J-wave syndrome | Subcutaneous ICD (secondary preention) | Metoprolol, hydroquinidine | ICD shock for VF triggered by PVC; PVC and WPW catheter ablation |

| P14 | 36 | Uncomplicated CD | Extreme asthenia | PVC, LBBB | DCM | 40 | CMR, PET, HE | Inflammatory (lymphocytic, virus-negative) | None | Bisoprolol | LVEF recovery up to 48% |

| P15 | 36 | Uncomplicated CD | Asthenia | VT, PVC | NDLVC | 65 | CMR, EAM | Undefined (fibrotic, low-dose parvovirus B19) | ICD (secondary prevention) | Flecainide | Uneventful |

| P16 | 34 | Uncomplicated VD | Palpitation | NSVT, PVC | NDLVC | 57 | CMR, HE, GT | Undefined (fibrotic)—class 3 variants in DSP and RYR2 genes | ILR | Flecainide | Upgrade to ICD after fast NSVT causing syncope |

Key clinical features of the case series (n = 16).

Baseline clinical features, treatment and outcomes are shown for patients (n = 16) with the arrhythmic variant of PPCM.

ACM, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; AF, atrial fibrillation; CCA, cardiocirculatory arrest; CD, Cesarean delivery; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DES, desmin; DMD, Duchenne's muscle dystrophy; DSP, desmoplakin; EAM, electroanatomical map; FLNC, filamin C; GT, genetic test; HE, histology exam; HTx, heart transplant; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; ICSI, intra cytoplasmatic sperm injection; ILR, implantable loop recorder; LAMA4, laminin subunit alptha-4; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NDLVC, nondilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PET, positron emission tomography; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; PVC, premature ventricular complexes; PVS, programmed ventricular stimulation; RBBB, right bundle branch block; RYR2, ryanodine receptor-2; SCD, sudden cardiac death; TTN, titin; VCL, vinculin; VD, vaginal delivery; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; WPW, Wolff-Parkinson-White.

Arrhythmias were documented in all patients at the time of first cardiological assessment after clinical presentation. In detail, premature ventricular complexes (PVC) were the most commonly recorded arrhythmia (median daily burden 1,128, range 322–21,960; short-coupled in two cases only), and showed dominant right bundle branch block morphology suggesting LV origin in 11/16; cases (69%). Other arrhythmias included ventricular fibrillation (VF) causing out-of-hospital cardiocirculatory arrest (n = 1), sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT; n = 2), nonsustained ventricular tachycardias (NSVT; n = 7), atrial fibrillation (AF; n = 1), Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW; n = 2, incidental diagnosis), and conduction system disorders (CSD; n = 4). By the end of the baseline workup, most patients (88%) had more than one arrhythmia type documented.

Results: diagnostic workup and clinical management

At presentation, the mean LVEF was 47% (range 20%–65%), and phenotype was consistent with DCM in 6 patients (38%), non-dilated LV cardiomyopathy (NDLVC) in 8 (50%), and no criteria for structural disease in n = 2 (13%). Multimodality diagnostic workup included CMR (n = 13; 81%), genetic test (n = 9; 56%), histology (n = 8; 50%), FDG-PET scan (n = 2; 13%), and EAM (n = 8; 50%). Overall, a mean of 2.5 exams per patient on top of baseline echocardiogram were required to identify the final diagnosis, which was: defined genetic cardiomyopathy (n = 2), myocarditis (n = 5), systemic sclerosis (n = 1), arrhythmogenic mitral valve prolapse (n = 1), and J-wave syndrome (n = 1). Representative examples of the diagnostic workup are shown in Figure 1. The median time from clinical onset of final diagnosis was 18 (range 9–42) months, with no patients being diagnosed during pregnancy.

Figure 1

Representative examples of the diagnostic workup in the case series. The main results of diagnostic findings are shown. (A) 12-lead electrocardiogram in a patient (P02) with signs of arrhthmogenic cardiomyopathy, including negative T-waves in anterior precordial leads, and epsilon waves (arrows). (B) Strial of late gadolinium enhancement involving the basal segments of the inferolateral left ventricular wall (arrows), in a patient (P15) with nondilated phenotype. (C) Endomyocardial biopsy findings in a patient (03) with subsequent diagnosis of systemic sclerosis. Extensive areas of replacement fibrosis are shown (circles) on hematoxylin-eosin assay. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis on endomyocardial biopsy show >7/mm2 CD3-positive T-lymphocytes, meeting the diagnostic criteria for active-phase myocarditis in a patient (P09) with arrhythmic presentation. (E) 12-lead recording of polymorphic premature ventricular complexes in a patient (P04) with underlying mitral valve prolapse an nonischemic scar in the left ventricle. (F) High-density electroanatomical maps of the left ventricular epicardium (CARTO system, Biosense Webster; Octaray multielectrode catheter), including low-voltage areas (voltage map—on the left) and late potentials (activation map during sinus rhythm—on the right) involving the inferolateral wall, in a patient (P11) undergoing catheter ablation of a drug-refractory ventricular tachycardia.

On top of standard medical treatment, including betablockers and renin-angiontensin-aldosterone-inhibitors in the postpartum period, antiarrhythmic agents were used in 6 patients (38%). Out of 7 women choosing breastfeeding, 4 had medical treatment temporarily interrupted during lactation. One patient (6%) received bromocriptine, and 4 (25%) underwent immunosuppressive therapy to target myocardial inflammation. Before discharge, implantable devices were placed in 11 patients (69%), including cardioverter defibrillators (ICD; n = 6, of whom 1 subcutaneous) and loop recorders in (ILR; n = 5). As per local standard practice, no patients received wearable cardioverter defibrillators (WCD). Because of uncontrolled psychiatric comorbidity, one patient refused any kind of therapy, including ICD implant.

Results: outcomes

All patients had uncomplicated pregnancy, including n = 1 preterm (6%) and n = 4 caesarean deliveries (25%). No health issues were reported in children. By a median follow-up of 7 (range 2–34) years, n = 4 patients (25%) experienced major adverse outcomes including SCD from cardiocirculatory arrest (n = 1), appropriate ICD shocks (n = 2), and end-stage heart failure requiring heart transplantation (n = 1). In addition, 6 patients (38%) requires catheter ablation of arrhythmias (PVC, n = 4; VT, n = 1; AF, n = 1, WPW, n = 2). Follow-up was uneventful in the remaining patients, and was remarkable for left ventricular reverse remodelling (LVRR) with improvement in LVEF in four of the six cases with DCM (67%). Three patients (19%) subsequently underwent new uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery, without LVEF decrease. Four patients underwent exercise stress test late after delivery without complications.

The relationships between baseline features and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The variales showing better association with the occurrence of major adverse outcomes included clinical presentation with sustained VT or VF, and presence of notable ECG abnormalities as epsilon- and J-waves (incidence of major adverse outcomes: 2/2 vs. 2/14, p = 0.05, for both variables). To be noted that the adverse outcomes (VF for P08, ICD shock for P13, see Table 1) were not related to WPW, which was previously treated via catheter ablation. A weaker association (p < 0.30) was found with LVEF < 50%, CSD, supraventricular arrhythmias, and abnormal T-waves (Table 2). For other clinically-relevant variables, such as genotypes and LGE, any reliable association analyses were prevented by the very small sample size. It should be highlighted that no adverse events occurred in patients receiving either immunomodulatory or prolactin-inhibitory therapy (0/5 vs. 4/11, p = 0.24).

Table 2

| Feature | Prevalence, n (%) | Major adverse outcomesa | Need for ICD or ablation | LVRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 30 years | 9 (56) | 3/9 vs. 1/7 | 6/9 vs. 6/7 | 1/9 vs. 3/7 |

| African ethnicity | 2 (13) | 0/2 vs. 4/14 | 1/2 vs. 11/14 | 1/2 vs. 3/14 |

| Family history of SCD/CMP | 2 (13) | 1/2 vs. 3/14 | 2/2 vs. 10/14 | 0/2 vs. 4/14 |

| CVRF | 6 (38) | 1/6 vs. 3/10 | 5/6 vs. 7/10 | 2/6 vs. 2/10 |

| BMI > 25 kg/m2 | 5 (31) | 1/5 vs. 3/11 | 3/5 vs. 9/11 | 1/5 vs. 3/11 |

| Twin pregnancy | 2 (13) | 1/2 vs. 3/14 | 2/2 vs. 10/14 | 1/2 vs. 3/14 |

| Extracardiac comorbidity | 5 (31) | 2/5 vs.2/11 | 4/5 vs. 8/11 | 1/5 vs. 3/11 |

| Syncope | 2 (13) | 1/2 vs. 3/14 | 2/2 vs. 10/14 | 1/2 vs. 3/14 |

| Sustained VT or VF | 2 (13) | 2/2 vs. 2/14 | 2/2 vs. 10/14 | 0/2 vs. 4/14 |

| NSVT | 7 (44) | 1/7 vs. 3/9 | 6/7 vs. 6/9 | 3/7 vs. 1/9 |

| PVC > 1,000/24 h | 10 (63) | 2/10 vs. 2/6 | 7/10 vs. 5/6 | 2/10 vs. 2/6 |

| Left ventricular PVC | 13 (81) | 3/13 vs. 1/3 | 9/13 vs. 3/3 | 3/13 vs. 1/3 |

| Supraventricular arrhythmias | 4 (25) | 2/4 vs. 2/12 | 4/4 vs. 8/12 | 1/4 vs. 3/12 |

| CSD | 4 (25) | 2/4 vs. 2/12 | 3/4 vs. 9/12 | 1/4 vs. 3/12 |

| Epsilon/J-waves | 2 (13) | 2/2 vs. 2/14 | 2/2 vs. 10/14 | 0/2 vs. 4/14 |

| T-wave abnormalities | 10 (63) | 4/10 vs. 0/6 | 9/10 vs. 3/6 | 3/10 vs. 1/6 |

| High natriuretic peptides | 4 (25) | 1/4 vs. 3/12 | 2/4 vs. 10/12 | 1/4 vs. 3/12 |

| DCM | 6 (38) | 2/6 vs. 2/10 | 4/6 vs. 8/10 | 2/6 vs. 2/10 |

| NDLVC | 8 (50) | 1/8 vs. 3/8 | 6/8 vs. 6/8 | 2/8 vs. 2/8 |

| LVEF < 50% | 7 (44) | 3/7 vs. 1/9 | 6/7 vs. 6/9 | 4/7 vs. 0/9 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 2 (13) | 0/2 vs. 4/14 | 2/2 vs. 10/14 | 1/2 vs. 3/14 |

| LGE on CMR | 10/12 (83) | 1/10 vs. 0/2 | 6/10 vs. 2/2 | 3/10 vs. 1/2 |

| Myocardial inflammation | 7/12 (58) | 1/7 vs. 0/5 | 4/7 vs. 4/5 | 3/7 vs. 1/5 |

| Class 4/5 gene variants Class 3/4/5 gene variants |

2/9 (22) 8/9 (89) |

1/1 vs. 3/7 3/8 vs. 1/1 |

1/1 vs. 7/7 7/8 vs. 1/1 |

0/1 vs. 1/7 1/8 vs. 0/1 |

| Positive PVS | 2/4 (50) | 0/2 vs. 1/2 | 2/2 vs. 2/2 | 0/2 vs. 1/2 |

| RAAS-inhibitors | 5 (31) | 1/5 vs. 3/11 | 3/5 vs. 9/11 | 2/5 vs. 2/11 |

| Betablockers | 10 (63) | 2/10 vs. 2/6 | 6/10 vs. 6/6 | 3/10 vs. 1/6 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 7 (44) | 1/7 vs. 3/9 | 7/7 vs. 5/9 | 2/7 vs. 2/9 |

| PD-treatment | 5 (31) | 0/5 vs. 4/11 | 3/5 vs. 9/11 | 1/5 vs. 3/11 |

Relationships between clinical features and outcomes.

Relationships between baseline clinical features and outcomes are shown for PPCM patients.

BMI, body mass index; CMP, cardiomyopathy; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CSD, conduction system disorders; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factors; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVRR, left ventricular reverse remodelling; NDLVC, nondilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PD, pathophysiology-driven; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; PVC, programmed ventricular complexes; PVS, programmed ventricular stimulation; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Major adverse outcomes include cardiac death, hear transplant, or malignant ventricular arrhythmias (sustained VT/VF or appropriate ICD therapy).

Critical review of the literature

Epidemiology

The global incidence of PPCM is 1 in 1,000 worldwide, with peak values in northern Nigeria (1:100) and Haiti (1:300) (8). Recognized risk factors for PPCM include African American ethnicity, maternal age over 30 years, chronic hypertension, pregnancy-associated-hypertensive conditions as preeclampsia, anemia, and prolonged use of beta-agonist tocolytics during threatened preterm labor (2, 8, 9).

Our report was notable for including women with no prior cardiological history, the majority of whom being Caucasian (88%). In addition, we hereby provided extensive characterization of patients with arrhythmias recorded during baseline workup, either at clinical presentation or immediately after. Remarkably, DCM phenotype accounted for <50% of our cohort, so that an “arrhythmic variant” of PPCM was hereby described. In the largest study on a population of 9,841 patients with classically-defined PPCM, the overall prevalence of arrhythmias was 19% (10). Among them, ventricular arrhythmias were the most common ones (4% for VT, 1% for VF), followed by supraventricular arrhythmias (1.3% for AF, 0.5% each for atrial flutter and atrial tachycardia, 0.3% for paroxysmal reentry tachycardia including WPW) and 2.5% of CSD mainly including left bundle branch blocks (10, 11). No conflicting data emerged from our series, except for PVC, which was the most common arrhythmia in our experience (15/16) in contrast with the 0.1% prevalence reported so far for both atrial and ventricular ectopies (10, 11). In this setting, we attempt to bridge a knowledge gap (10, 11), by providing data about daily burden (widely variable in range 322–21,960), and morphology (mainly right bundle branch block, suggesting LV origin, as expected in PPCM).

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of arrhythmias in PPCM reflects the multifactorial nature of the disease, whose dominant mechanisms are summarized in Table 3. Briefly, hemodynamic changes, autonomic dysregulation, electrolyte imbalances, systemic inflammation, metabolic and hormonal effects have been described, either as a substrate or triggering events for HF and arrhythmias related to PPCM (2, 14, 15).

Table 3

| Mechanism class | Mechanism type | Effects on PPCM | Effects on heart rhythm | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamic changes | ↑ blood volume (+30%) | ↑ LVEDP, ↑ LVEDV | Sinus tachycardia, arrhythmias from volume/pressure overload | (8, 11, 12) |

| ↑ stroke volume (+25%) | ↑ LVEDP | |||

| ↑ vascular peripheral resistances | ↑ LEDVP, ↑ LVH | |||

| Autonomic dysregulation | ↑ adrenergic tone | ↓ CFR, ↑HR, ↑Heart work, ↑HF, ↑LVEDP. | Sinus tachycardia, ectopic beats, adrenergic VA, enhanced reentry if preexisting accessory pathways or dual atrioventricular node physiology | (2, 11, 13) |

| Electrolyte imbalance | Hypokalemia | ↑HR, ↑Heart work | Long QT, polymorphic VA | (13, 14) |

| Vascular abnormalities | Enhanced angiogenesis from ↑ serum PlGF, ↑ serum sFLt-1 | Preeclampsia, ↑ LVEDP | Unknown | (2, 8, 15) |

| Endothelial dysfunction | ↓ Tissue repair | Unknown | ||

| Coronary microvascular dysfunction | Ischemia | Arrhythmias from myocardial ischemia and scarring | ||

| Inflammation and immune dysregulation | ↑ circulating proinflammatory cytokines (CRP, TNF-alpha, IL-6) | ↓ dp/dt, ↑HF, ↑LVED P. |

VA and bradyarrhythmias | (8, 11, 13, 16) |

| Myocardial inflammation | DCM ↑Fibrosis, ↑HF, ↓Cardiac output |

Hot-phase, inflammation-dependent arrhythmias; Cold-phase, scar-related arrhythmias |

||

| Viral genomes (i.e. EBV, CMV, HHV6, PVB19) within cardiac myocytes | Chronic DCM and heart failure (+1/3), ↑ cardiac interstitial inflammatory process | ↑Vasodilatation, ↑LVP | ||

| Hormonal effects | ↑ prolactin secretion: reduction in STAT3 leads to prolactin cleavage in an antiangiogenic and proapoptotic isoform | ↓Angiogenesis,↑Vasoconstriction, ↑ Systemic resistances which lead to ↑HF. | Arrhythmias (from the most common to the less): AF, VT, VF | (9, 11, 13) |

| ↑ levels of estradiol and progesterone | ↑Vasodilatation, ↑LVEDP | Arrhythmias | ||

| Metabolic dysregulation | Increased MHR and LDL | LV adverse remodeling due to ↑ oxidative stress | Arrhythmias | (2, 8, 11, 13) |

| Increased adipogenesis | LV adverse remodeling due to ↑ oxidative stress | T-wave inversion, PVC, VT | ||

| Nutritional deficiencies | ↓ dp/dt, LV adverse remodeling | Unknown | ||

| Genetic background | Pathogenic or likely-pathogenic variants in cardiomyopathy-associated genes (TTN, DSP, MYH6, MYH7, TPM1, VCL, RBM20) | DCM, Myocardial inflammation | Ventricular arrhythmias: VT, VF | (16, 17) |

Pathophysiological mechanisms of PPCM.

The main pathophysiological mechanisms of PPCM are shown, including the relationships with arrhythmogenesis.

AF, atrial fibrillation; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CRP, C-reactive protein; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DSP, desmoplakin; dp/dt, contractility; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HF, heart failure; HR, heart rate; HV6, human herper virus-6; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LV, left ventricle; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MHR, monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio; MYH6, myosin heavy chain-6; MYH7, myosin heavy chain-7; PlGF, placental growth factor; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; PVB19, parvovirus B19; PVC, premature ventricular complexes; RBM20, RNA binding motif-20; sFLt-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1; STAT3, single transducer and activator of transcription-3; TNF-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; TPM1, tropomyosin-1; TTN, titin; VA, ventricular arrhythmias; VCL, vinculin; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

As an alternative to the multisystemic dysregulation hypothesis, it has been suggested that latent preexisting myocardial diseases, including but not limited to myocarditis and primary cardiomyopathies, may retain a primary role in the disease pathophysiology (2, 12). In this setting, the current definition of PPCM (2, 3) is challenging, since a preexisting undiagnosed disease may be simply unmasked during pregnancy or after delivery. In a study (9), almost one third of PPCM patients showed biopsy-proven cardiotropic viral genomes, suggesting that DCM and HF may occur as late manifestations of chronic myocarditis. An increased risk of preeclampsia has been reported also in association with COVID-19 infection (18). Autoimmune virus-negative myocarditis has also been described as a driver mechanism in PPCM (2), also because of the microchimerism from fetus-derived cells during the immune-suppressed pregnant state (19). As known, myocarditis may account for a broad range of arrhythmias, complicating both the inflammatory and the postinflammatory phases of the disease, even in the patients with preserved LVEF (20, 21). In our series, myocarditis was detected either by CMR or EMB in 7 of 16 patients (44%). As the only viral genome found in the myocardium, parvovirus B19 (load < 500 copies/mcg) was infrequently found (Table 1). While prior studies failed in demonstrating higher rates of EMB-proven myocarditis among PPCM cases (22, 23), the role of myocardial inflammation as an arrhythmogenic substrate is still to be investigated.

In turn, the genetic basis of PPCM has been recently revealed (16, 24). Historically, PPCM has been differentiated from primary DCM because of its idiopathic, non-familial, non-genetic substrate (3, 4, 9). For instance, distinct cellular pathways downstream prolactin have been described as cardiomyopathic susbstrate specific of PPCM (25). However, in a recent study on 172 women with PPCM (17), truncating variants in genes predisposing to DCM were identified in 26 cases (15%). In this setting, volume overload and other systemic changes associated with pregnancy, may act as accelerating factors in sensitive genotypes. The main reports involved genes encoding titin (TTN), desmoplakin (DSP), alpha myosin heavy chain protein (MYH6), tropomyosin (TPM1), vinculin (VCL) and lamin A/C (LMNA), which constitute key structural and functional components for the cytoskeleton organization (7, 17, 26). Consistently, we detected CGVs in 8 of the 9 gentoyped patients (89%). While two patients only (13%) carried CGVs with a compelling pathogenic role (class 4/5), the hemodynamic changes associated with physiological pregnancy may have unmasked a concealed cardiomyopathic substrate even in the remaining subjects. Similar effects have been described for women carrying TTN truncating variants, where pregnancy has been described as a “second hit” for the classic PPCM presentation (17). In this setting, the presence and type of arrhythmias may strongly depend on the genotype. For instance, cytoskeletal genes may predispose to maladaptive evolution towards DCM, whereas desmosomal genes towards ventricular arrhythmias and myocardial inflammation (17, 27). In turn, mutations in the LMNA gene may account for both brady- and tachyarrhythmias, much earlier than overt LV systolic dysfunction occurs (28). Preliminary evidence suggests that life-threatening arrhythmias in the peripartum may be associated even with Brugada syndrome or long QT syndrome (29–31). Dedicated studies are needed to add confirmatory evidence in this setting.

Multimodality diagnostic workup

In compliance with the current standards, PPCM should be suspected every time signs or symptoms of cardiac disease are found for the first time in a pregnant woman (2, 3). In the “classic” DCM phenotype, PPCM may be easily detected by routine transthoracic echocardiogram (8). In particular, a number of parameters may differentiate pregnancy-associated physiological findings from maladaptive PPCM changes by ultrasounds (32–35). However, diagnosis may be more challenging following clinical onset of arrhythmias: as noted above, many of the patients included in our report (63%) had either NDLVC or normal phenotype. While the finding of LVEF < 45% was uncommon, and the diagnosis of the classic variant of PPCM was subsequently not met, all patients in our series had documented arrhythmias with or without signs of associated muscle disease (Table 1). To be noted, only two patients in our series (13%) had relatives known for SCD or cardiomyopathy, in line with the 15% prevalence reported in a published German registry (36). While a number of arrhythmogenic conditions, such as WPW, were likely preexisting and simply unmasked by pregnancy, diagnostic assessment was challenging for most women. As a uniform tract, arrhythmias were documented, and diagnosed for the first time either during pregnancy or by 6 months after delivery, so that an “arrhythmic” variant of PPCM is hereby proposed. Importantly, arrhythmic manifestations occurred irrespectively of LVEF values (Table 1). In this context, the overlap with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, channelopathies and inflammatory heart diseases is more demanding as compared with DCM. As currently suggested for many arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies (7, 37), even in our experience a multimodality diagnostic approach was useful in characterizing the disease. Table 4 summarizes the spectrum of diagnostic techniques available to detect cardiomyopathic substrates in PPCM.

Table 4

| Exam | Pregnancy-associated findings | PPCM-associated findings | Caveats in pregnancy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECG and Holter ECG | Sinus tachycardia (30–40%) Leftward shift of the QRS axis |

T-wave inversion (70%) Long QT (44%) Brugada pattern (reports) ST-segment abnormalities (14%) AV blocks (reports) LBBB (1%) Atrial fibrillation (reports) Other paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias (reports) Ventricular arrhythmias (PVC, NSVT,VT) |

None | (10, 11, 14, 34) |

| Echocardiogram | Increased cardiac chambers volume. LV hypertrabeculation. Preserved systolic function | Systolic dysfunction, with LVEF < 45% LVEDD > 60mm–64mm LVFS < 16% LAVi > 30 ml/m2 LVGLS > 11%, LVGCS > 10% RVFAC < 31% Mitral regurgitation |

None | (32–35) |

| Blood exams | Normal natriuretic peptides and troponin | Natriuretic peptide elevation (NTproBNP > 300 pg/ml, BNP > 100 pg/ml), Troponin elevation (suggests myocarditis, spasm or SCAD) |

None | (4, 9, 33, 38, 39) |

| CMR | Increased LVEDV, RV size, LAVi. LV hypertrabeculation. Unchanged LVEF, RVEF. Absence of LGE and cardiomyopathy-associated tissue abnormalities |

LGE →DCM findings (presence of midwall septal stria) Mural thrombi T2-weighted abnormalities |

Avoid IV gadolinium administration if not necessary (however, both the diagnostic and prognostic values of the exam may be limited). Discontinue lactation for 24h after IV gadolinium administration | (3, 7, 40–43) |

| Coronary angiography, CT scan | Normal epicardial coronary arteries | ACS, spasm or SCAD | Radiation exposure, contrast toxicity, procedural risk | (7, 13, 14) |

| EMB | Normal cardiac myocytes. Absence of fibrosis, inflammation, storage diseases. Microvascular remodelling | Myocardial inflammation, LV/RV hypertrophy. Replacement, interstitial, perivascular fibrosis | Radiation exposure, procedural risk | (9, 22, 23) |

| FDG-PET | Normal FDG uptake | Possible sarcoidosis pattern | Radiation exposure | (7, 44, 45) |

| Electroanatomical mapping | Normal endocardial voltage. Absence of late potentials | Low-voltage areas Late potentials suggesting underlying cardiomyopathy |

Radiation exposure, contrast toxicity, procedural risk. Indication limited to patients with indication to catheter ablation of arrhythmias | (7, 46, 47) |

| Genetic testing | DCM shared background: pathogenic or likely-pathogenic variants, mainly in TTN, DSP, TPM1, MYH6, VCL, and LMNA genes | Counselling for risk and family screening | (3, 7, 17, 48) |

Diagnostic workup and findings in pregnancy and PPCM.

The main diagnostic findings expected in the arrhythmic variant of PPCM are shown.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AV, atrioventricular; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CT, computed tomography; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DSP, desmoplakin; ECG, electrocardiogram; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; FDG, fluprodeoxyglucose; IV, intravenous; LAV(i)=left atrial volume (indexed); LBBB, left bundle branch block; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LMNA, lamin A/C; LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening; LVGCS, left ventricular global circumferential strain; LVGLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; NTproNP, N-terminal brain natriuretic pepetide; PET, positron emission tomography; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; PVC, premature ventricular complexes; RV, right ventricular; RVFAC, right ventricular fractional area change; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; SCAD, spontaneous coronary artery dissection; TPM-1, tropomyosin-1; TTN, titin; VCL, vinculin; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

In classic PPCM, sinus rhythm ECG may reveal signs suggestive for PPCM, like T-wave inversion in up to 70% of patients (14, 49). Cardiac biomarkers, such as natriuretic peptides BNP and NT-proBNP, are frequently elevated (9, 38, 39). Beyond hypokynesis, echocardiogram may show extensive remodeling of cardiac chambers and diastolic dysfunction (3, 34, 50, 51). Not infrequently, LV hypertrabeculation exceeding the degree expected during pregnancy is observed (8, 52). While functional mitral valve regurgitation in classic PPCM may occur secondarily to LV dilation, thickened leaflets and specific signs should call for mitral valve prolapse as an alternative source of arrhythmias (53).

Among second-level imaging techniques, CMR is currently considered as the gold standard in cardiomyopathies (7), and it is proven safe in pregnancy (3). Although no specific diagnostic criteria for PPCM have been described at CMR, most patients with classic PPCM phenotype had no evidence of LGE (40, 41). As opposed, we documented nonischemic LGE in almost all women with the arrhythmic variant of PPCM (Table 2). In this setting, distinct patterns of LGE may also point to specific diagnoses, such as primary DCM in the presence of midwall septal stria (7), myocarditis in association with subepicardial involvement of the inferolateral wall (42), and distinct variants of NDLVC in the presence of a ring-like appearance (7, 43). In addition, abnormalities on T2-weighted sequences enforce the suspicion of myocardial inflammation (54), which frequently deserves confirmation and further etiological characterization by EMB, as recommended in patients with myocarditis (42). Histology may also reveal tissue remodeling, fibrosis, and associated viral genomes (9, 22, 23). As an alternative to histology, FDG-PET may be particularly useful whenever cardiac sarcoidosis is clinically suspected, or implantable device-related artifacts prevent the interpretation of CMR (7, 44–55). Finally, in patients with clinical indication to catheter ablation, EAM may help identifying low-voltage areas or electrogram abnormalities suggestive for a cardiomyopathic substrate (46, 47). Whenever familial disease is suspected, or upstream workup suggests signs of a genetic disease, wide-spectrum genetic test should be strongly considered (3, 7, 48). Even in the absence of macroscopic substrate abnormalities, long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, catecholamine-related VT syndromes may account for concealed arrhythmogenic substrates (56, 57). In such heterogeneous scenarios, genotyping may help in reaching a definite diagnosis. In partial agreement with the published literature (16, 17), 50% of patients in our report had CGVs detected by genetic test. Nonetheless, because of the frequent finding of variants of unknown significance, diagnosing a genetically-proven cardiomyopathy was challenging in the majority of cases.

It is worth noting that, in our series, the average number of the above-mentioned second level exams was 2.5 per patient, thus allowing to reach the diagnosis by a median follow-up of 18 months from clinical onset, i.e., late after delivery. Our data indicate that diagnostic characterization for clinically-suspected PPCM may be complex and lengthy, and relies on multimodality workup.

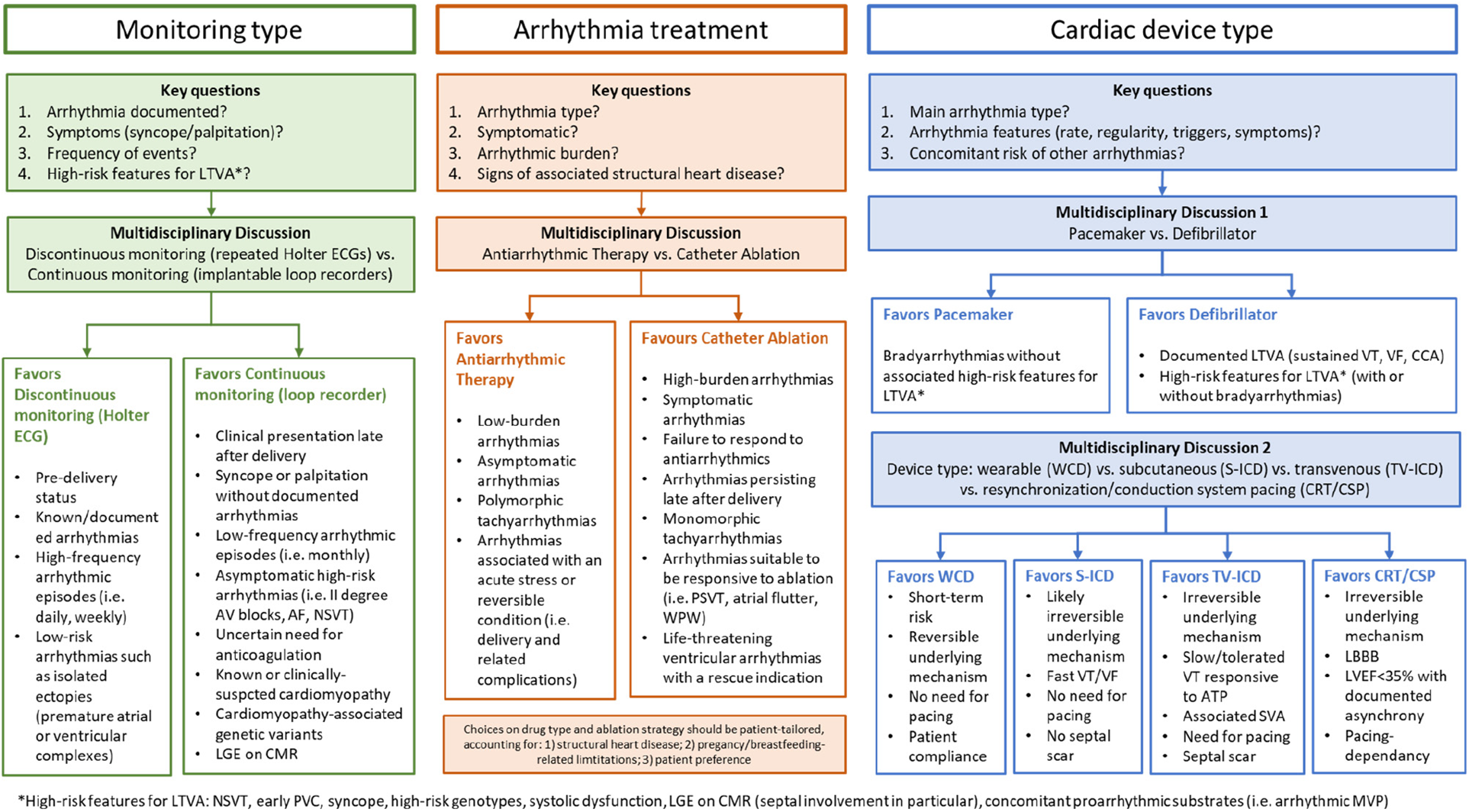

One last critical point concerns the detection of arrhythmic episodes. Since arrhythmias may arise suddenly, discontinuous monitoring by means of repeated Holter ECG of 24 or 48h registration, may result in significant underdetection of rhythm disorders (58). In our series, most patients had arrhythmias detected because of inhospital setting and continuous telemonitoring. For instance, NSVT episodes were detected in up to 7 of 16 patients (44%), in contrast to the 21% detected by Holter ECG in a published series (58). Given that continuous electrical monitoring techniques had demonstrated superiority to discontinuous monitoring in similar clinical scenarios (59), ILR may find application in selected cases considered at lower risk of SCD and no indication to ICD (60). In our series, one patient carrying ILR subsequently underwent upgrade to ICD because of fast NSVT episodes missed by Holter ECG. The proposed diagnostic algorithm for arrhythmia detection in PPCM is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Clinical scenarios in the arrhythmic variant of PPCM. The main clinical challenges for multidisciplinary heathcare teams to manage patients with clinically-suspected peripartum cardiomyopathy and either proven or suspected arrhythmias are shown. AF, atrial fibrillation; ATP, anti-tachycardia pacing; AV, atrioventricular; CCA, cardiocirculatory arrest; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CRT/CSP, cariac resynchronization therapy/conduction systema pacing; ECG, electrocardiogram; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (S, suubcutaneous; TV, transvenous); LBBB, left bundle branch block; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LTVA, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MVP, mitral valve prolapse, NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PSVT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia; SVA, supraventricular arrhythmias; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; WCD, wearable cardioverter defibrillator; WPW, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Risk stratification

PPCM has an increasing incidence (8), and has been reported as the leading cause of maternal cardiovascular death (61), with mortality rates ranging from 1.3% inhospital, to 16% at 7 years (62, 63). Overall, VA are the most threatening manifestations of classic PPCM, accounting for up to 1 out of 4 cases of SCDs (13). Mortality of PPCM-patients experiencing arrhythmia is 2.1%, three-fold higher than without arrhythmias (11).

Instead, bradyarrhythmias are reported benign and self-limited in most cases (10). In fact, unless accompanied by ventricular arrhythmias, underlying diseases with adverse prognostic significance such as sarcoidosis and LMNA cardiomyopathy are unlikely (60).

As for the mechanical manifestations of the disease, LV reverse remodeling and full recovery of LVEF have been described in many patients during the postpartum period, with LVEF normalization rates of up to 71% by 6 months after delivery (64). Also in our series, LVEF at presentation was associated with higher recovery rates (Table 2), confirming the published data (8). In classic PPCM, additional prognostic factors for heart failure include LVEF below 45%, increased LV end-diastolic diameter, reduced LV strain parameters, right ventricular or biventricular dysfunction, and increased left atrial volume (32, 33, 65, 66). Also, women whose LV ejection fraction failed to return within the normal range after their first episode of PPCM showed an increased risk of PPCM recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy (67, 68). In this setting, NT-proBNP values ≥900 pg/ml were found as negative predictors of LV reverse remodeling (38), whereas a BNP value <100 pg/ml was found accurate in ruling out adverse events related to PPCM (39).

Even in the absence of an overt DCM phenotype, the identification of LGE on CMR, especially with a septal distribution pattern, can be predictive of both for SCD and end-stage heart failure (60, 69, 70). Advanced myocardial imaging may also identify mitral annular disjunction and additional prognostic signs for arrhythmogenic mitral valve prolapse (71). In this setting, the genetic test has a major impact on patient prognosis: in fact, in compliance with the updated guideline recommendations (7), the identification of “high risk” genotypes may significantly contribute to both the arrhythmic risk stratification and the clinician's decision of ICD implant. In our experience, while both medical treatment and ICD were refused by the patient, the only case of SCD occurred in a patient with overt DCM who harbored a pathogenic TTN truncating mutation (as reported in Table 1).

Remarkably, prognostic evaluation by disease-specific risk factors cannot be applied in the absence of a specific etiology (7, 60). As far as no comprehensive risk score calculators become available for PPCM from large multicenter studies, a multimodal and patient-tailored arrhythmic risk stratification strategy is strongly advised.

Personalized treatment strategies

An evidence-based overview of the available treatment options to manage arrhythmias in PPCM is presented in Table 5. The traditional RAAS-inhibitors, as well as angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, are contraindicated during pregnancy and can be only used in the post-partum period (2–4, 73), as occurred in our cases. Episodes of acute HF are managed by oxygen administration, fluid restriction, loop diuretics, nitrates and vasodilators as hydralazine (8, 9, 72). In severe cases, inotropes and mechanical circulatory support are needed (2, 8). Anticoagulants can be administered according to the current recommendations in patients with LVEF < 30%–35% (76, 77), in particular in the presence of risk factors for thromboembolic events, as in AF or LV hypertrabeculation (52).

Table 5

| Therapy | Indication | First choice | Caveats in pregnancy/breastfeeding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure—DCM treatment | ||||

| ACE-inhibitors, ARB, ARNI, MRA | LV reverse remodeling | None (patient-tailored) | Contraindicated during pregnancy. Can be used only in postpartum | (3, 4) |

| Diuretics | Heart failure symptoms | Loop Diuretics | Avoid if hypertension/preeclampsia, for risk of reduced blood flow in the placenta | (8, 9, 72) |

| Vasodilators | Hypertension, acute heart failure | Hydralazine and nitrates | Adverse effect: SLE-like syndrome, fetal tachyarrhythmias | (8, 9, 72) |

| Inotropes | Acute heart failure | Dopamine and levosimendan | Only when the foreseen beneficial effects overweight risks | (72) |

| MCS | Acute heart failure refractory to inotropes | None (patient-tailored) | Only when the foreseen beneficial effects overweight risks | (2, 8, 72) |

| Arrhythmia management | ||||

| Betablockers | Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias, LQTS and other arrhythmogenic diseases | metoprolol, sotalol, propranolol | Avoid atenolol, bisoprolol | (60, 73) |

| Calcium channel antagonists | Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias | verapamil | Favor non-dihydropiridinic agents | (59, 73) |

| Other antiarrhythmic drugs | Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias | flecainide, digoxin | Avoid amiodarone and dronedarone (fetal hypothyroidism). Only when the foreseen beneficial effects overweight risks (teratogenic risk during the first trimester, abnormal growth development later) |

(73–75) |

| Anticoagulants | AF, LVNC, of intracardiac thrombi/systemic embolism | LMWH, VKA, UFH | Avoid vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester (embryopathy). Prefer LMWH in the first trimester |

(52, 76, 77) |

| Electrical cardioversion | Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias | None | Only for hemodynamic unstable tachyarrhythmias | (60, 73) |

| Pacemakers | Irreversible symptomatic bradycardia due to third-degree or second-degree Mobitz type II heart block or severe sinus node dysfunction, with syncope or presyncope | None (patient-tailored) | Safer when implanted with fetus beyond 8 weeks gestation. Rule-out high-risk features for ventricular arrhythmias. Favor near-zero fluoroscopy procedures. | (73, 78–80) |

| Defibrillators | LVEF < 35% without reversibility features (primary prevention). Sustained VT episodes during pregnancy (secondary prevention) | None (patient-tailored) | Give no contraindications for future pregnancies. Prefer WCD with a bridge-to-recovery or bridge-to-decision indication. Avoid S-ICD if need for pacing is foreseen. | (3, 4, 81, 82) |

| Catheter ablation | Drug-refractory and/or poorly tolerated tachycardias. | None | If possible defer to the 2nd trimester or after delivery due to radiation exposure. Favor near-zero fluoroscopy procedures. | (46, 47, 73) |

| Pathophysiology-guided treatment | ||||

| Bromocriptine | Reduced LVEF heart failure | None | To be considered in combination with heart failure therapy and anticoagulation therapy | (83, 84) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | Fulminant myocarditis. Chronic virus-negative inflammatory cardiomyopathy | IV methylprednisolone, IVIG | Systemic immunosuppressive agents are contraindicated during pregnancy. To be evaluated in the postpartum period, upon multidisciplinary team evaluation | (85, 86) |

Treatment options for PPCM and related arrhythmias.

Treatment options for patients with PPCM and related arrhythmias are shown.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors; IV, intravenous; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulins; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; LQTS, long QT syndrome; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVNC, left ventricular noncompaction; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; MRA, mineralcorticoid receptor antagonists; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; S-ICD, subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VKA, vitamin K antagonists; VT, ventricular tachycardia; WCD, wearable cardioverter defibrillator.

Among antiarrhythmic drugs, the use of amiodarone is restricted during pregnancy, since it can induce fetal hypothyroidism, growth retardation, and prematurity (73). Most betablockers, including sotalol, and central calcium-channel antagonists as verapamil, are well tolerated during pregnancy (60, 73). Instead, digoxin or flecainide should be used when benefits overwhelm risks (73–75), such as in the event of fetal arrhythmias (87). For unstable arrhythmias, electrical cardioversion is a suitable and safe option during pregnancy, but the presence of an obstetrician in advisable in light of the risk of increased intrauterine activity (11, 73). In our experience, betablocker and antiarrhythmic agents were employed in 63% and 44% of patients, respectively, without safety issues when used during pregnancy.

Among cardiac devices, pacemakers are indicated in case of severe bradycardia or CSD (78–80). Importantly, underlying arrhythmogenic diseases and/or risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias should be carefully ruled out, to ensure that ICD are not needed instead. A guide for the clinical decision making is summarized in Figure 2. Given the transitory nature of PPCM and associated arrhythmias, WCD constitute a reasonable approach to protect pregnant women from arrhythmias in the short term. Women with a severe systolic dysfunction, as in PPCM with a LVEF under 35%, are more likely to manifest SCD from malignant ventricular arrhythmias (2, 8). Remarkably, the incidence of appropriate ICD shocks in PPCM was as high as 37% over a mean 3-year follow-up (88), i.e., at a significant longer term as compared to the postpartum period. Therefore, to avoid unnecessary ICD implant in primary prevention, WCD may be used for a few months with a bridge-to-recovery indication (2, 81, 82). Similar considerations are applied in the context of secondary prevention of SCD in patients presenting their first VT episode in pregnancy (4, 60). In this setting, withdrawal of WCD may be more challenging since no temporal cutoffs are available to notify the end-of-risk timing. It should be noted that, reflecting the local standard practice, no patients in our series had WCD. Consistently, in a recent consensus document of the Heart Rhythm Society (73), it has been reported that the criteria for early ICD placement should be more stringent compared to other cardiac conditions. This particularly applies to patients presenting with LVEF below 30% in conjunction with a LV end-diastolic diameter equal to or exceeding 60 mm, because of the low likelihood of LVRR even in the long term (89). The ESC guidelines recommend that for women presenting with symptoms and severe LV dysfunction 6 months after initial presentation, despite optimal medical therapy and left bundle branch block-shaped QRS with duration greater than 120 ms, cardiac resynchronization therapy should be strongly considered, because of the reported beneficial effects in classic PPCM (90). While transvenous devices may be placed even during pregnancy in selected cases, delivery prior to device implantation is advised for most PPCM patients (11). In fact, although the current reaching the fetus is minimal, transient fetal arrhythmias after electrical resynchronization have been described (91). Efforts should be also made to minimize fetal radiation exposure by limiting fluoroscopy and using abdominal shielding. Successful ICD implantation using echocardiography without fluoroscopy is a desirable option (92). Of 16 patients, the clinical indication to ICD implant applied to up to 10 patients (64%) by the end of follow-up.

Catheter ablation is another key therapeutic weapon that applies to a range of arrhythmias in a number of clinical scenarios. In the acute setting, catheter ablation is reserved for women suffering from hemodynamically unstable arrhythmias (10), as well as for VT persisting in spite of antiarrhythmic therapy (46, 47). In our series all patients received ablation late after clinical onset. As for cardiac device implant, also catheter ablation is preferred after delivery or when a pregnancy is planned in case arrhythmias have been already diagnosed (4, 46). This particularly applies to non-life threatening arrhythmias such as AF, as well as for reentry circuits likely to be completely abolished by ablation, such as WPW (73). Before performing catheter ablation in a pregnant woman, risk and benefit of both mother and fetus must be considered, because consequences include fetal radiation exposure, maternal hemodynamic imbalance, impaired placental perfusion (33).

As a final remark, among pathophysiology-directed strategies, the inhibition of prolactin secretion by means of bromocriptine in addition to standard heart failure therapy has shown promising results in two clinical trials (83, 84), but evidence is still contradictory (2, 8, 12), and no data are available about antiarrhythmic effects. Concerns have been raised also about drug-associated maternal adverse vascular events (93). For classic PPCM, the ESC included a weak recommendation (class II b, level of evidence B) for the use of bromocriptine (4). In our series on arrhythmic PPCM, only one patient (6%) received bromocriptine, but despite association with metoprolol she still required catheter ablation of PVC (Table 1). In selected patients with PPCM secondary to myocarditis, intravenous immunoglobulin administration has shown an improvement in LVEF (85). While no role is currently recognized for other etiology-driven therapies, it should be noted that three patients with EMB-proven virus-negative lymphocytic myocarditis underwent safe immunosuppressive therapy (86) in the postpartum period. All of them had uneventful follow-up, except for the need of PVC ablation in a patient with residual monomorphic PVC: results are consistent with the pleiotropic beneficial effects of immunosuppression in arrhythmic myocarditis (94), but it should deserve dedicated investigation as pathophysiology-guided therapy in the PPCM population. Our experience showed that 6 patients were ablated in the postpartum (38%), including 50% (2 of 4) of those showing LVRR during follow-up (Table 1).

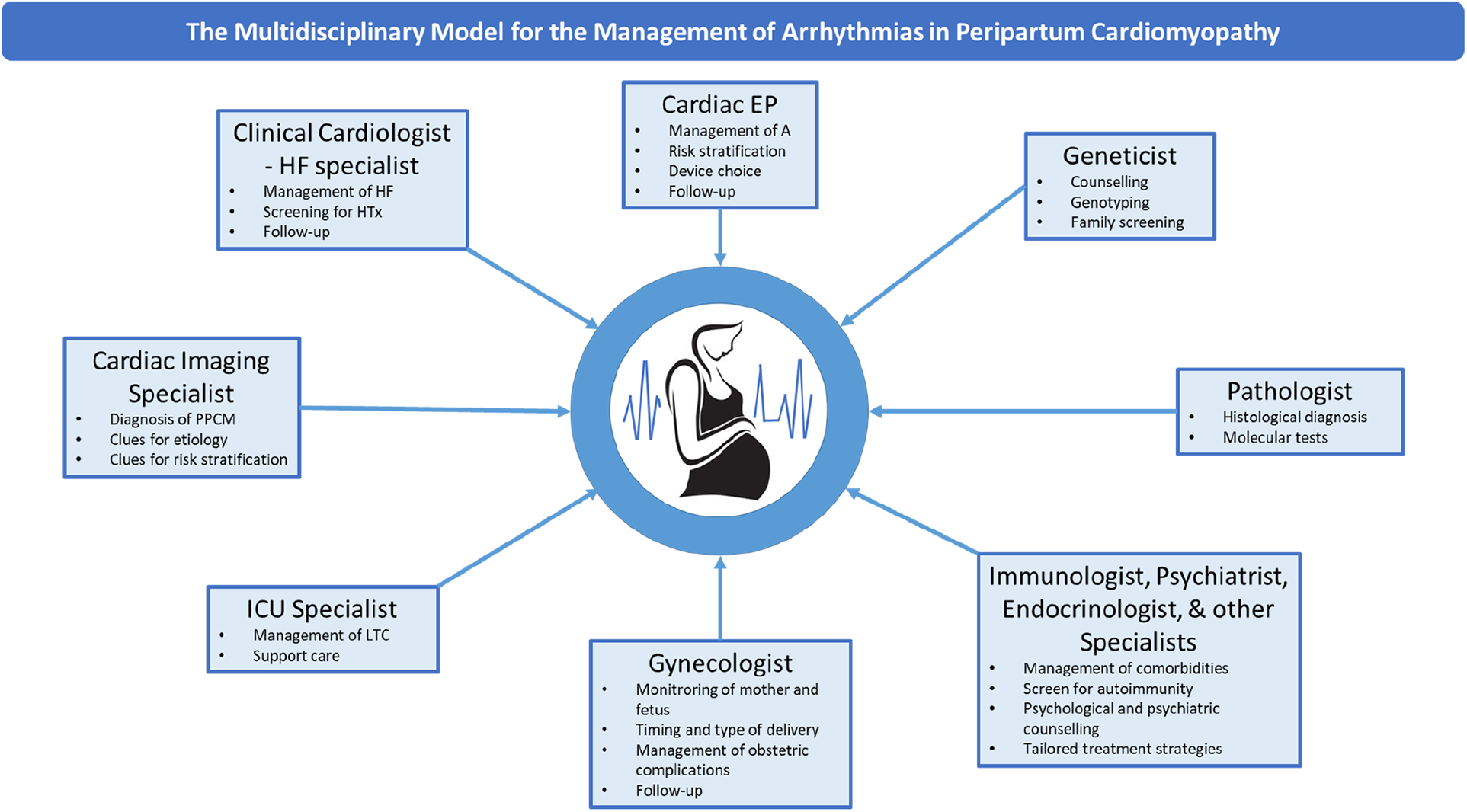

Given the complex and multifactorial nature of the disease, multidisciplinary healthcare teams should become the gold-standard model of care, in compliance with the current recommendations applying to all cardiomyopathies (7). Figure 3 summarizes the model proposed based on the literature review and our own experience. On top of HF specialists, cardiac electrophysiologists have a critical role in decision making about management of arrhythmias and the prevention of SCD, both in the short and in the long term. Geneticists have a key contribution in defining clinical indications to genetic tests and enabling family screening. Gynecologists retain a key role, also for defining the mode and optimal timing of delivery. Other specialists may provide relevant contributions, such as immunologists and endocrinologists for the administration of pathophysiology-driven therapies. Also, since one patient in our series underwent arrhythmic SCD after refusing ICD and therapies, psychiatrists should assist in managing either preexisting or peripartum-associated mental comorbidities.

Figure 3

The multidisciplinary model for the management of arrhythmias in PPCM. The main components of the multidisciplinary healthcare team for the management of PPCM and related arrhythmias are shown. EP, electrophysiologist; HF, heart failure; HTx, heart transplant; LTC, life-threatening conditions; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Conclusions

PPCM is a complex and multifactorial disease, whose arrhythmic manifestations are currently under-investigated. While treatment choices are strongly conditioned by the pregnancy status, an open-minded and patient-tailored diagnostic workup is strongly encouraged to allow optimal treatment options after differential diagnosis is solved.

Efforts are needed to describe and further characterize the “arrhythmic” variant of PPCM, which posed hard clinical challenges for SCD risk assessment, as compared to the classic DCM phenotype with heart failure manifestations. In fact, differentiating bystander vs. PPCM-triggered arrhythmias, as well as revealing a missed preexisting diagnosis are a major issue, as shown in our case series. In these settings, multimodality diagnostic workup and multidisciplinary care models should be promoted. Similarly, regular follow-up is required in the long term to clarify the underlying diagnosis and prevent complications.

Given the association between PPCM and arrhythmic phenomena, which can even result in SCD, efforts are needed to early identify the best candidates to undergo definitive implantation of ICD. Multicentre prospective studies on well selected populations of PPCM patients are advocated, to substantially advance our knowledge in such a hot topic of modern medicine.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by AINICM Protocol, IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

GP: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis. EM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. GC: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ML: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MC: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. AB: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. DL: Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LA: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. PC: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AC: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. PD: Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. CP: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This study was partially supported by Ricerca Corrente funding from Italian Ministry of Health to IRCCS Policlinico San Donato.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed during GP tenure as the Clinical Research Award in Honor of Mark Josephson and Hein Wellens Fellow of the Heart Rhythm Society.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Homans DC . Peripartum cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. (1985) 312(22):1432–7. 10.1056/NEJM198505303122206

2.

Davis MB Arany Z McNamara DM Goland S Elkayam U . Peripartum cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75(2):207–21. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.014

3.

Sliwa K Hilfiker-Kleiner D Petrie MC Mebazaa A Pieske B Buchmann E . Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement from the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology working group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. (2010) 12(8):767–78. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq120

4.

Regitz-Zagrosek V Roos-Hesselink JW Bauersachs J Blomström-Lundqvist C Cífková R De Bonis M . 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39(34):3165–241. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340

5.

Demakis JG Rahimtoola SH . Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. (1971) 44:964–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.44.5.964

6.

Pearson GD Veille JC Rahimtoola S Hsia J Oakley CM Hosenpud JD et al Peripartum cardiomyopathy: national heart, lung, and blood institute and office of rare diseases (national institutes of health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. (2000) 283(9):1183–8. 10.1001/jama.283.9.1183

7.

Arbelo E Protonotarios A Gimeno JR Arbustini E Barriales-Villa R Basso C . 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(37):3503–626. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194

8.

Arany Z Elkayam U . Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. (2016) 133(14):1397–409. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020491

9.

Shah T Ather S Bavishi C Bambhroliya A Ma T Bozkurt B . Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a contemporary review. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. (2013) 9(1):38–41. 10.14797/mdcj-9-1-38

10.

Lindley KJ Judge N . Arrhythmias in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 63(4):878–92. 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000567

11.

Honigberg MC Givertz MM . Arrhythmias in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Card Electrophysiol Clin. (2015) 7(2):309–17. 10.1016/j.ccep.2015.03.010

12.

Baris L Cornette J Johnson MR Sliwa K Roos-Hesselink JW . Peripartum cardiomyopathy: disease or syndrome? Heart. (2019) 105(5): 357–62. Published online February 12, 2019. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314252

13.

Hähnle L Hähnle J Sliwa K Viljoe C . Detection and management of arrhythmias in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. (2020) 10(2):325–35. 10.21037/cdt.2019.05.03

14.

Dunker D Pfeffer TJ Bauersachs J Veltmann C . ECG and arrhythmias in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Herzschr Elektrophys. (2021) 32:207–13. 10.1007/s00399-021-00760-9

15.

Mebazaa A Séronde M Gayat E Tibazarwa K Anumba D Akrout N . Imbalanced angiogenesis in peripartum cardiomyopathy- diagnostic value of placenta growth factor. Circ J. (2017) 81(11):1654–61. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1193

16.

Spracklen TF Chakafana G Schwartz PJ Kotta MC Shaboodien G Ntusi NAB . Genetics of peripartum cardiomyopathy: current knowledge, future directions and clinical implications. Genes (Basel). (2021) 12(1):103. Published online January 15, 2021. 10.3390/genes12010103

17.

Ware JS Li J Mazaika E Yasso CM DeSouza T Cappola TP . Shared genetic predisposition in peripartum and dilated cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:233–41. 10.1056/nejmoa1505517

18.

Papageorghiou AT Deruelle P Gunier RB Rauch S García-May PK Mhatre M . Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2021) 225(3):289.e1–e17. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.014

19.

Kinder JM Stelzer IA Arck PC Way SS . Immunological implications of pregnancy-induced microchimerism. Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17(8):483–94. 10.1038/nri.2017.38

20.

Peretto G Sala S Rizzo S De Luca G Campochiaro C Sartorelli S . Arrhythmias in myocarditis: state of the art. Heart Rhythm. (2019) 16(5):793–801. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.11.024

21.

Peretto G Sala S Rizzo S Palmisano A Esposito A De Cobelli F . Ventricular arrhythmias in myocarditis: characterization and relationships with myocardial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75(9):1046–57. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.036

22.

Bültmann BD Klingel K Näbauer M Wallwiener D Kandolf R . High prevalence of viral genomes and inflammation in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2005) 193:363–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.022

23.

Fett JD. Viral particles in endomyocardial biopsy tissue from peripartum cardiomyopathy patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2006) 195:330–1; author reply 331. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.810

24.

Goli R Li J Brandimarto J Levine LD Riis V McAfee Q . IMAC-2 and IPAC investigators genetic and phenotypic landscape of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. (2021) 143(19):1852–62. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052395

25.

Bollen IA Van Deel ED Kuster DWD Van Der Velden J . Peripartum cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy: different at heart. Front Physiol. (2015) 5:2–6. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00531

26.

Micaglio E Monasky MM Bernardini A Mecarocci V Borrelli V Ciconte G et al Clinical considerations for a family with dilated cardiomyopathy, sudden cardiac death, and a novel TTN frameshift mutation. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22(2):670. 10.3390/ijms22020670

27.

Peretto G Sommariva E Di Resta C Rabino M Villatore A Lazzeroni D . Myocardial inflammation as a manifestation of genetic cardiomyopathies: from bedside to the bench. Biomolecules. (2023) 13(4):646. 10.3390/biom13040646

28.

Peretto G Sala S Benedetti S Di Resta C Gigli L Ferrari M . Updated clinical overview on cardiac laminopathies: an electrical and mechanical disease. Nucleus. (2018) 9(1):380–91. 10.1080/19491034.2018.1489195

29.

Prochnau D Figulla HR Surber R . First clinical manifestation of brugada syndrome during pregnancy. Herzschrittmacherther Elektrophysiol. (2013) 24(3):194–6. 10.1007/s00399-013-0287-1

30.

Ambardekar AV Lewkowiez L Krantz MJ . Mastitis unmasks brugada syndrome. Int J Cardiol. (2009) 132(3):e94–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.154

31.

Nakatsukasa T Ishizu T Adachi T Hamada H Nogami A Ieda M . Long-QT syndrome with peripartum cardiomyopathy causing fatal ventricular arrhythmia after delivery. Int Heart J. (2023) 64(1):90–4. 10.1536/ihj.22-408

32.

Ravi Kiran G RajKumar C Chandrasekhar P . Clinical and echocardiographic predictors of outcomes in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy: a single centre, six month follow-up study. Indian Heart J. (2021) 73(3):319–24. 10.1016/j.ihj.2021.01.009

33.

Sanusi M Momin ES Mannan V Kashyap T Pervaiz MA Akram A . Using echocardiography and biomarkers to determine prognosis in peripartum cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Cureus. (2022) 14:5–7. 10.7759/cureus.26130

34.

Afari HA Davis EF Sarma AA . Echocardiography for the pregnant heart. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 23(8):55. 10.1007/s11936-021-00930-5

35.

Khaddash I Hawatmeh A Altheeb Z Hamdan A Shamoon F . An unusual cause of postpartum heart failure. Ann Card Anaesth. (2017) 20(1):102–3. 10.4103/0971-9784.197846

36.

Haghikia A Podewski E Libhaber E Labidi S Fischer D Roentgen P . Phenotyping and outcome on contemporary management in a German cohort of patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. (2013) 108(4):366. 10.1007/s00395-013-0366-9

37.

Peretto G De Luca G Villatore A Di Resta C Sala S Palmisano A . Multimodal detection and targeting of biopsy-proven myocardial inflammation in genetic cardiomyopathies: a pilot report. JACC Basic Transl Sci. (2023) 8(7):755–65. 10.1016/j.jacbts.2023.02.018

38.

Hoevelmann J Muller E Azibani F Kraus S Cirota J Briton O . Prognostic value of NT-proBNP for myocardial recovery in peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM). Clin Res Cardiol. (2021) 110(8):1259–69. 10.1007/s00392-021-01808-z

39.

Tanous D Siu SC Mason J Greutmann M Wald RM Parker JD et al B-type natriuretic peptide in pregnant women with heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2010) 56(15):1247–53. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.076

40.

Schelbert EB Elkayam U Cooper LT Givertz MM Alexis JD Briller J . Myocardial damage detected by late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance is uncommon in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. (2017) 6(4):e005472. 10.1161/JAHA.117.005472

41.

Ersbøll AS Bojer AS Hauge MG Johansen M Damm P Gustafsson F . Long-term cardiac function after peripartum cardiomyopathy and preeclampsia: a danish nationwide, clinical follow-up study using maximal exercise testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Heart Assoc. (2018) 7(20):e008991. 10.1161/JAHA.118.008991

42.

Caforio AL Pankuweit S Arbustini E Basso C Gimeno-Blanes J Felix SB . Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. (2013) 34:2636–48. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210

43.

Augusto JB Eiros R Nakou E Moura-Ferreira S Treibel TA Captur G . Dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic left ventricular cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive genotype-imaging phenotype study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2020) 21:326–36. 10.1093/ehjci/jez188

44.

Seballos RJ Mendel SG Mirmiran-Yazdy A Khoury W Marshall JB . Sarcoid cardiomyopathy precipitated by pregnancy with cocaine complications. Chest. (1994) 105(1):303–5. 10.1378/chest.105.1.303

45.

DeFilippis EM Beale A Martyn T Agarwal A Elkayam U Lam CSP . Heart failure subtypes and cardiomyopathies in women. Circ Res. (2022) 130(4):436–54. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319900

46.

Cronin EM Bogun FM Maury P Peichl P Chen M Namboodiri N . 2019 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias: executive summary. Europace. (2020) 22(3):450–95. 10.1093/europace/euz332

47.

Tokuda M Stevenson WG Nagashima K Rubin DA . Electrophysiological mapping and radiofrequency catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia in a patient with peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2013) 24(11):1299–301. 10.1111/jce.12250

48.

Richards S Aziz N Bale S Bick D Das S Gastier-Foster J . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17:405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30

49.

Mallikethi-Reddy S Akintoye E Trehan N Sharma S Briasoulis A Jagadeesh K . Burden of arrhythmias in peripartum cardiomyopathy: analysis of 9841 hospitalizations. Int J Cardiol. (2017) 235:114–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.084

50.

Ekizler FA Cay S . A novel marker of persistent left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy: monocyte count- to- HDL cholesterol ratio. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2019) 19:114. 10.1186/s12872-019-1100-9

51.

Fukumitsu A Muneuchi J Watanabe M Sugitani Y Kawakami T Ito K . Echocardiographic assessments for peripartum cardiac events in pregnant women with low-risk congenital heart disease. Int Heart J. (2021) 62:1062–8. 10.1536/ihj.20-807

52.

Vergani V Lazzeroni D Peretto G . Bridging the gap between hypertrabeculation phenotype, noncompaction phenotype and left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). (2020) 21(3):192–9. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000924

53.

Basso C Iliceto S Thiene G Perazzolo Marra M . Mitral valve prolapse, ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death. Circulation. (2019) 140(11):952–64. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034075

54.

Ferreira VM Schulz-Menger J Holmvang G Kramer CM Carbone I Sechtem U . Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72:3158–76. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.072

55.

Peretto G Busnardo E Ferro P Palmisano A Vignale D Esposito A . Clinical applications of FDG-PET scan in arrhythmic myocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2022) 15(10):1771–80. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.02.029

56.

Pappone C Santinelli V Mecarocci V Tondi L Ciconte G Manguso F . Brugada syndrome: new insights from cardiac magnetic resonance and electroanatomical imaging. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2021) 14(11):e010004. 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.010004

57.

Di Resta C Berg G Villatore A , Concealed substrates in Brugada syndrome: isolated channelopathy or associated cardiomyopathy?Genes (Basel). (2022) 13(10):1755. 10.3390/genes13101755

58.

Diao M Diop IB Kane A Camara S Kane A Sarr M et al Electrocardiographic recording of long duration (holter) of 24 h during idiopathic cardiomyopathy of the peripartum [in French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. (2004) 97:25–30.

59.

Peretto G Mazzone P Paglino G Marzi A Tsitsinakis G Rizzo S . Continuous electrical monitoring in patients with arrhythmic myocarditis: insights from a referral center. J Clin Med. (2021) 10(21):5142. 10.3390/jcm10215142

60.

Zeppenfeld K Tfelt-Hansen J de Riva M Gregers Winkel B Behr ER Blom NA . 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(40):3997–4126. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262

61.

Hameed AB Lawton ES McCain CL Morton CH Mitchell C Main EK . Pregnancy-related cardiovascular deaths in California: beyond peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2015) 213(3):379.e1–10. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.008

62.

Kolte D Khera S Aronow WS Palaniswamy C Mujib M Ahn C . Temporal trends in incidence and outcomes of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: a nationwide population-based study. J Am Heart Assoc. (2014) 3:e001056. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001056

63.

Harper MA Meyer RE Berg CJ . Peripartum cardiomyopathy: population-based birth prevalence and 7-year mortality. Obstet Gynecol. (2012) 120:1013–9. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826e46a1

64.

McNamara DM Elkayam U Alharethi R Damp J Hsich E Ewald G , IPAC Investigators. Clinical outcomes for peripartum cardiomyopathy in North America: results of the IPAC study (investigations of pregnancy-associated cardiomyopathy). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 66:905–14. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1309

65.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Presidential Task Force on Pregnancy and Heart Disease and Committee on Practice Bulletins —Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin No. 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. (2019) 133:e320–56. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003243

66.

Maish B Lamparter S Ristić A Pankuweit S . Pregnancy, and cardiomyopathies. Herz. (2003) 28:196–208. 10.1007/s00059-003-2468-x

67.

Elkayam U Tummala PP Rao K Akhter MW Karaalp IS Wani OR . Maternal and fetal outcomes of subsequent pregnancies in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. (2001) 344(21):1567–71. 10.1056/NEJM200105243442101

68.

Habli M O'Brien T Nowack E Khoury S Barton JR Sibai B . Peripartum cardiomyopathy: prognostic factors for long-term maternal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2008) 199(4):415.e1–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.087

69.

Peretto G Sala S Lazzeroni D Palmisano A Gigli L Esposito A . Septal late gadolinium enhancement and arrhythmic risk in genetic and acquired non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. Heart Lung Circ. (2019) 29(9):1356–65. 10.1016/j.hlc.2019.08.018

70.

Elkayam U . Clinical characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58(7):659–70. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.047

71.

Miller MA Dukkipati SR Turagam M Liao SL Adams DH Reddy VY . Arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse: jACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72(23 Pt A):2904–14. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.048

72.

Hilfiker-Kleiner D Westhoff-Bleck M Gunter HH von Kaisenberg CS Bohnhorst B Hoeltje M et al A management algorithm for acute heart failure in pregnancy. The hannover experience. Eur Heart J. (2015) 36:769–70. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv009

73.

Joglar JA Kapa S Saarel EV Dubin AM Gorenek B Hameed AB . 2023 HRS expert consensus statement on the management of arrhythmias during pregnancy. Heart Rhythm. (2023) 20(10):e175–264. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.05.017

74.

Li JM Nguyen C Joglar JA Hamdan MH Page RL . Frequency and outcome of arrhythmias complicating admission during pregnancy: experience from a high-volume and ethnically-diverse obstetric service. Clin Cardiol. (2008) 31:538–41. 10.1002/clc.20326

75.

Chang SH Kuo CF Chou IJ See LC Yu KH Luo SF . Outcomes associated with paroxysmal sup- raventricular tachycardia during pregnancy. Circulation. (2017) 135:616–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025064

76.

Bozkurt B Colvin M Cook J Cooper LT Deswal A Fonarow GC . Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for specific dilated cardiomyopathies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2016) 134(23):e579–646. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000455

77.