Abstract

Objective:

Anticoagulation is crucial for patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to the high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). However, the optimal anticoagulation regimen needs further exploration. Therefore, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of diverse anticoagulation dosage dosages for COVID-19.

Methods:

An updated meta-analysis was performed to assess the effect of thromboprophylaxis (standard, intermediate, and therapeutic dose) on the incidence of VTE, mortality and major bleeding among COVID-19 patients. Literature was searched via PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for effect estimates.

Results:

Nineteen studies involving 25,289 participants without VTE history were included. The mean age of patients was 59.3 years old. About 50.96% were admitted to the intensive care unit. In the pooled analysis, both therapeutic-dose and intermediate-dose anticoagulation did not have a significant advantage in reducing VTE risk over standard dosage (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.58–2.02, and OR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.70–1.12, respectively). Similarly, all-cause mortality was not further decreased in either therapeutic-dose group (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 0.75–1.67) or intermediate-dose group (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 0.83–2.17). While the major bleeding risk was significantly elevated in the therapeutic-dose group (OR = 2.59, 95%CI: 1.87–3.57) as compared with the standard-dose regimen. Compared with intermediate dosage, therapeutic anticoagulation did not reduce consequent VTE risk (OR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.52–1.38) and all-cause mortality (OR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.60–1.17), but significantly increased major bleeding rate (OR = 2.42, 95% CI: 1.58–3.70). In subgroup analysis of patients older than 65 years, therapeutic anticoagulation significantly lowered the incidence of VTE in comparation comparison with standard thromboprophylaxis, however, at the cost of elevated risk of major bleeding.

Conclusion:

Our results indicated that for most hospitalized patients with COVID-19, standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation might be the optimal choice. For elderly patients at low risk of bleeding, therapeutic-dose anticoagulation could further reduce VTE risk and should be considered especially when there were other strong risk factors of VTE during hospital stay.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, identifier, CRD42023388429.

1 Introduction

Since December 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has led to large-scale human transmission and caused hundreds of thousands deaths around the world (1). Due to complexity and heterogenous severity of COVID-19, large difficulties and challenges in disease management have been brought by its complications during clinical practice, among which venous thromboembolism (VTE) deserves more attention being paid to because of potential fatal events, especially in early pandemic era (2). VTE includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). As is known, PE is caused by an obstruction of the pulmonary arteries, most often occluded by thrombus derived from DVT of the lower extremities, and its major symptoms include dyspnea, chest pain, syncope, hemoptysis, etc. (3) and dyspnea. In patients with COVID-19, significant abnormalities in coagulation function have been reported (4). In addition to this, vascular wall injuries, blood stream stasis, and hypercoagulable state in hospitalized COVID-19 patients increases the risk of VTE (5–7). Unpredictable deterioration and even sudden death may occur in some COVID-19 patients due to secondary VTE event during disease management (8). Thus, early recognition of risk factors and appropriate thromboprophylaxis of VTE in patients with COVID-19 are crucial for lowering in-hospital mortality and may to improve long-term prognosis.

Growing evidence has shown that prophylactic anticoagulation can effectively reduce the incidence of VTE and mortality rate in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with COVID-19, especially in critically ill patients, although at price of increased risk of bleeding (9–11). However, various dosages of prophylactic anticoagulation are used in practice to balance clinical benefit and bleeding risk. Still, no valid consensus has been reached regarding optimal anticoagulation dosage for VTE prevention in COVID-19 patients to achieve best efficacy and less hemorrhage event (12–16).

Although previous meta-analysis has addressed this issue, emerging new studies with diverse outcomes have been published later, and various virus strain of SARS-CoV-2 has evolved which may possess different impact on VTE risk.

Therefore, we conducted this updated meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of different prophylactic anticoagulation regimen (standard dose, intermediate dose, and therapeutic dose) on the incidence of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality, to obtain better and more detailed evidence on VTE prophylaxis for hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

Low molecular weight heparins are most frequently used for thromboprophylaxis in COVID-19. Therefore, in this meta-analysis, we assessed three conventional prophylactic anticoagulation regimen with low molecular weight heparins (shown in Table 1) on the incidence of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality among COVID-19 patients. This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (17) and the guidance from Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (18). The protocol of this study has been registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO) with registration number of CRD42023388429.

Table 1

| Prophylactic dose | Intermediate dose | Therapeutic dose | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrCl>30 ml/min | CrCl ≤30 ml/min | CrCl>30 ml/min | CrCl ≤30 ml/min | CrCl>30 ml/min | CrCl ≤30 ml/min | |

| Enoxaparin | 40 mg/24 h | 20 mg/24 h | 1 mg/kg/24 h >80 kg:60 mg/24 h | 0.5 mg/kg/24 h >80 kg:40 mg/24 h | 1.5 mg/kg/24 h or 1 mg/kg/12 h | 1 mg/kg/24 h |

| Tinzaparin | 4,500 IU/24 h | 4,500 IU/24 h | 75 IU/kg/24 h >90 kg:50 IU/kg/24 h | 75 IU/kg/24 h >90 kg:50 IU/kg/24 h | 175 IU/kg/24 h | 175 IU/kg/24 h |

| Bemiparin | 3,500 IU/24 h | 2,500 IU/24 h | 5,000 IU/24 h | 3,500 IU/24 h | 115 IU/kg/24 h | 85 IU/kg/24 h |

| Fondaparinux | 2.5 mg/24 h | 1.5 mg/24 h | 5 mg/24 h | 2.5 mg/24 h | <50 kg: 5 mg/24 h 51–100 kg: 7.5 mg/24 h >100 kg: 10 mg/24 h |

Not recommended |

Doses of low molecular weight heparin administered in the three anticoagulation regimens.

Mg, milligrams; IU, international units; kg, kilograms; h, hours; CrCl, calculated creatinine clearance rate.

2.2 Search strategy

We designed a high-sensitivity search strategy that combined the following search items: free-text and keyword synonyms of COVID-19 and VTE, and word clusters of prophylactic anticoagulation. Literature was searched through PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database. We further searched with the keywords “standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation”, “intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation”, and “therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation” on bioRxiv (http://www.biorxiv.org) server, medRxiv (http://www.biorxiv.org) server and Chinaxiv (http://biotech.chinaxiv.org) server, in order to identify potential pre-publication manuscripts that met the eligibility criteria. The search spanned from January 1, 2020to October 31, 2022. The reference lists of all included articles were also reviewed for potential eligible studies.

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers independently performed a two-step selection, screening by title and abstract, followed by a full-text review. Studies would be included if they met the following criteria: (1) they were randomized controlled trial, observational cohort, or case-control study; (2) they enrolled hospitalized COVID-19 patients without VTE at baseline who did not receive anticoagulation in the past six months; (3) outcomes of interest were compared among patients receiving standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation and therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation; (4) outcomes of interest included one of the followings: event of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) non-human studies; (2) non-comparative studies; (3) studies that did not recruit COVID-19 patients; (4) studies with no available data to extract; (5) certain type of studies like reviews, meta-analysis, or editorials.

Data extraction was conducted using standardized data extraction forms. The following information were collected from the retrieved literature: the first author's name, publication year, study design, research site, patient characteristics (including age, gender, and disease severity), follow-up period, incidence of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality rate. Discrepancies were solved by discussion.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Effects of 3 different dosing prophylactic anticoagulation on the incidence of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality of COVID-19 patients were presented or calculated as odds ratio (OR), relative risk (RR), or hazard ratio (HR), with 95% confidence interval (CI) from included studies. We pooled ORs across studies using inverse-variance weighted DerSimonian-Laird method to calculate effect estimate. RR and HR were considered as equivalent as OR during meta-analysis. Continuous variables were calculated as weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI. The median value and interquartile range (IQR) provided from original studies were converted to mean and standard deviation (SD) according to the method by Wan et al. (19). Between-study heterogeneity was tested by Cochrane Q and I2 statistic. I2 > 50% or P < 0.1 was considered as significant heterogeneity and random effects model was used to combine the results. Otherwise, fixed effects model was used (17). Funnel plots and sensitivity analysis were then conducted to examine the publication bias and stability of meta-analysis result, respectively. All statistical analysis process were conducted using Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and STATA 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, U.S).

2.5 Literature quality evaluation

The methodological quality of included articles was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), available at: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/CIinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. The total score of NOS rangeed from 0 to 9 stars, with more stars representing higher quality. Two authors independently went through this scoring process, and discrepancies were solved by discussion.

2.6 Network meta-analysis

So far, current studies mainly compared the efficacy and safety between intermediate-dose and standard-dose anticoagulation, or between therapeutic-dose and standard-dose anticoagulation for COVID-19 patients. Fewer studies [Jonmarker et al. (20) and Blondon et al. (21)] investigated the difference between intermediate-dose with therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, making it less convincing to perform traditional meta-analysis. Thus, we chose network meta-analysis and defined standard-dose anticoagulation as plan A (plan 1 in the rank), intermediate-dose anticoagulation as plan B (plan 2 in the rank), and therapeutic-dose anticoagulation as plan C (plan 3 in the rank). The network meta-analysis was conducted using “mvmeta” package and “network” package of STATA 14.0 software.

3 Results

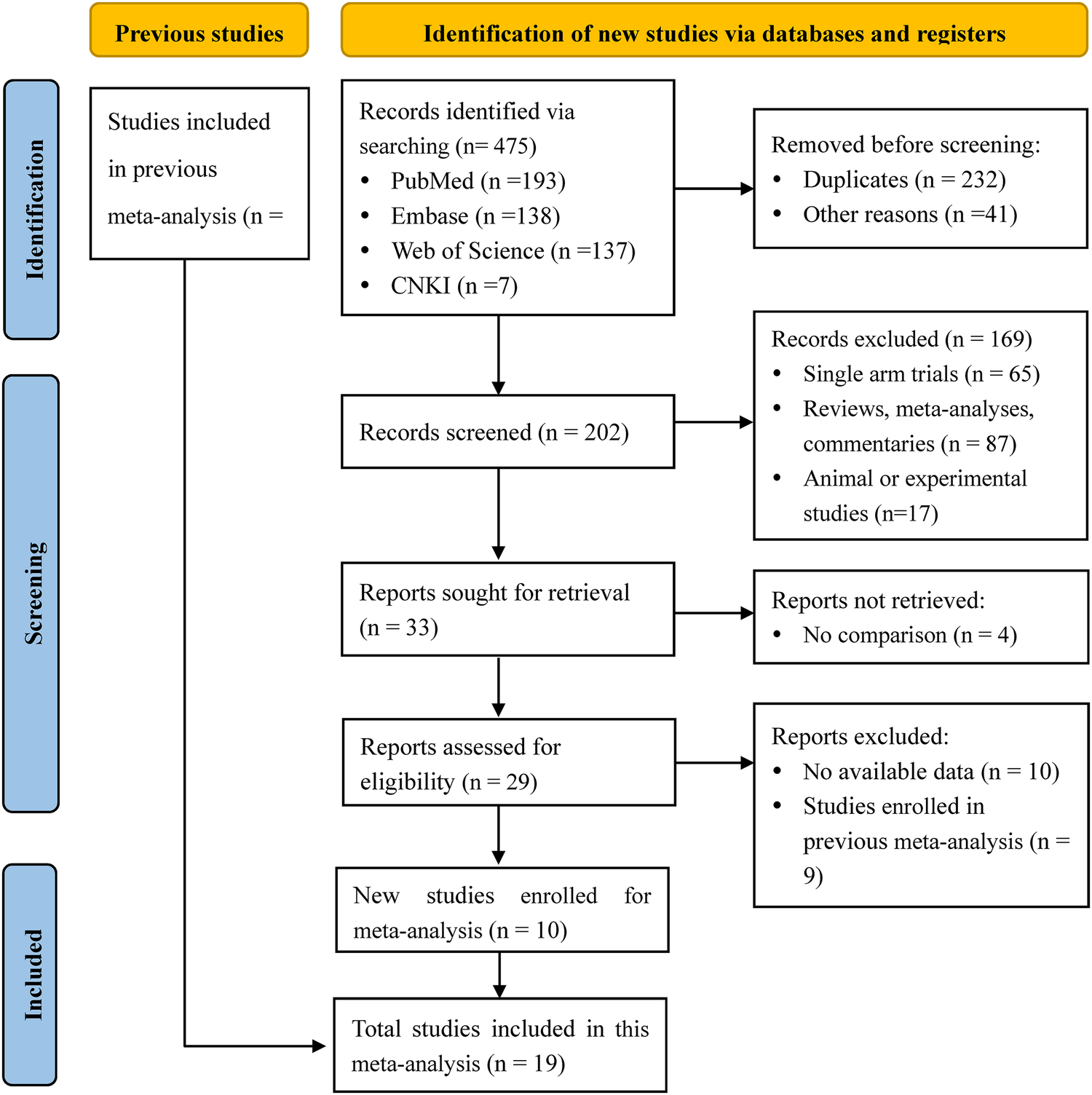

We searched 205 studies and screened 202 studies by title and abstract, and then obtained 33 eligible studies. There were 14 studies excluded after the full-text screening, and we finally included 19 works of literature (10, 12, 16, 22–37) for meta-analysis, containing 3 retrospective cohort studies and 16 randomized controlled trials. Study selection and characteristics were shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, separately. The synthesis results of the meta-analysis were the comprehensive impact of different doses (therapeutic-dose vs. standard-dose, intermediate-dose vs. standard-dose, therapeutic-dose vs. intermediate-dose) of prophylactic anticoagulation on the incidence of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality among COVID-19 patients without VTE at admission.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow chart of literature research and selection for updated meta-analysis.

Table 2

| Study | Country | Groups | Design | No of participants | Age, years, (median, mean ± SD or IQR) | Gender: male, % | Follow-up period | Severe case, % | VTE (event/total) | Major bleeding (event/total) | Mortality (event/total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spyropoulos et al. (16) | U.S. | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 253 | TD: 65.8 ± 13.9 | TD: 52.7 | 371 days | 32.81 | TD: 14/129 | TD: 6/129 | TD: 25/129 |

| SD: 67.7 ± 14.1 | SD: 54.8 | SD: 36/124 | SD: 2/124 | SD: 31/124 | |||||||

| Sadeghipour et al. (22) | Iran | ID vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 562 | ID: 62 (51.0, 70.7) | ID: 58.7 | 113 days | 100 | ID: 9/276 | ID: 7/276 | ID: 119/276 |

| SD: 61 (47.0, 71.0) | SD: 57.0 | SD: 10/286 | SD: 4/286 | SD:117/286 | |||||||

| Perepu et al. (23) | U.S. | ID vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 176 | ID: 65.0 (24.0, 86.0) | ID: 54.0 | 255 days | 60.80 | ID: 11/87 | ID: 2/87 | ID: 13/87 |

| SD: 63.5 (30.0, 85.0) | SD: 58.1 | SD: 6/86 | SD: 2/86 | SD: 2/86 | |||||||

| Alrashed et al. (24) | Saudi Arabian | TD vs. SD, ID vs. SD |

Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 551 | TD: 55.6 ± 13.12 | TD: 79.9 | 17 months | 100 | TD: 43/179 | TD: 18/179 | TD: 104/179 |

| ID: 56.4 ± 13.79 | ID: 78.3 | ID: 28/180 | ID: 6/180 | ID: 93/180 | |||||||

| SD: 59.2 ± 14.98 | SD: 68.2 | SD: 25/192 | SD: 6/192 | SD: 112/192 | |||||||

| Bikdeli et al. (25) | U.S. | ID vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 562 | ID: 62 (51.0, 70.7) | ID: 58.7 | 113 days | 100 | ID: 9/276 | ID: 7/276 | ID: 127/276 |

| SD: 61 (47.0, 71.0) | SD: 57.0 | SD: 10/286 | SD: 4/286 | SD: 123/286 | |||||||

| Lawler et al. (26) | 9 countries | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 2,231 | TD: 59.0 ± 14.1 | TD: 60.4 | 276 days | 2.02 | TD: 13/1,180 | TD: 22/1,180 | TD: 86/1,180 |

| SD: 58.8 ± 13.9 | SD: 56.9 | SD: 22/1,046 | SD: 9/1,047 | SD: 86/1,046 | |||||||

| Goligher et al. (27) | 3 international adaptive platform | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 1,103 | TD: 60.4 ± 13.1 | TD: 72.2 | 242 days | 100 | TD: 38/530 | TD: 20/529 | TD: 199/534 |

| SD: 61.7 ± 12.5 | SD: 67.9 | SD: 62/559 | SD: 13/562 | SD: 200/564 | |||||||

| Lemos et al. (28) | Brazil | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, single center | 20 | TD: 55.0 ± 10.0 | TD: 90.0 | 4 months | 100 | TD: 2/10 | TD: 0/10 | TD: 2/10 |

| SD: 58.0 ± 16.0 | SD: 70.0 | SD: 2/10 | SD: 0/10 | SD: 5/10 | |||||||

| Lopes et al. (29) | Brazil | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 615 | TD: 56.7 ± 14.1 | TD: 61.7 | 247 days | 6.50 | TD: 11/310 | TD: 10/310 | TD: 35/310 |

| D: 56.5 ± 14.5 | SD: 57.9 | SD: 18/304 | SD: 4/304 | SD: 23/304 | |||||||

| Sholzberg et al. (30) | 6 countries | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 465 | TD: 60.4 ± 14.1 | TD: 53.9 | 318 days | 16.13 | TD: 2/228 | TD: 2/228 | TD: 4/228 |

| SD: 59.6 ± 15.5 | SD: 59.5 | SD: 6/237 | SD: 4/237 | SD: 18/237 | |||||||

| Muñoz-Rivas et al. (31) | Spain | TD vs. SD, ID vs. SD |

Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 300 | TD: 58.5 ± 14.4 | TD: 60.2 | 241 days | 7.67 | TD: 2/103 | TD: 3/103 | TD: 2/103 |

| ID: 56.5 ± 14.1 | ID: 62.6 | ID: 2/91 | ID: 3/91 | ID: 3/91 | |||||||

| SD: 54.1 ± 15.0 | SD: 59.4 | SD: 4/106 | SD: 4/106 | SD: 2/106 | |||||||

| Matli et al. (32) | Lebanon | TD vs. SD | Retrospective cohort, single center | 82 | TD: 62.55 ± 15.80 | TD: 67.7 | 10 months | 20.73 | TD: 9/31 | TD: 2/31 | TD: 7/31 |

| SD: 59.69 ± 17.04 | SD: 58.8 | SD: 5/51 | SD: 5/51 | SD: 5/51 | |||||||

| Bohula et al. (33) | U.S. | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 382 | TD: 59 (50, 70) | TD: 61.8 | 574 days | 100 | TD: 18/191 | TD: 4/191 | TD: 1/191 |

| SD: 62 (51, 68) | SD: 56.5 | SD: 28/191 | SD: 1/191 | SD: 1/191 | |||||||

| Marcos-Jubilar et al. (34) | Spain | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 65 | TD: 63.0 ± 13.7 | TD: 53.1 | 8 months | 20.00 | TD: 0/32 | TD: 0/32 | TD: 2/32 |

| SD: 62.3 ± 12.2 | SD: 72.7 | SD: 2/33 | SD: 0/33 | SD: 1/33 | |||||||

| Sholzberg et al. (35) | U.S. | TD vs. SD | Randomized clinical trial, multicenter | 257 | 67 | 54 | 30 days | 33.07 | NA | TD: 6/130 | TD: 25/130 |

| SD: 2/127 | SD: 32/127 | ||||||||||

| Myers et al. (36) | U.S. | TD vs. SD, ID vs. SD |

Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 17,130 | TD: 62.4 ± 14.4 | TD: 65.3 | 305 days | 29.45 | TD: 56/1,721 | TD: 119/1,721 | TD: 453/1,721 |

| ID: 56.8 ± 14.7 | ID: 60.1 | ID: 58/6,754 | ID: 160/6,754 | ID: 649/6,754 | |||||||

| SD: 59.8 ± 16.0 | SD: 55.9 | SD: 99/8,655 | SD: 189/8,655 | SD:968/8,655 | |||||||

| Gabara et al. (10) | Spain | TD vs. SD, ID vs. SD |

Randomized clinical trial, single center | 201 | TD: 68.1 ± 9.6 | TD: 72.4 | 2 months | 100 | TD: 6/29 | TD: 9/29 | TD: 8/29 |

| ID: 62.4 ± 12.5 | ID: 69.1 | ID: 21/94 | ID: 14/94 | ID: 17/94 | |||||||

| SD: 59.5 ± 13.6 | SD: 71.8 | SD: 14/78 | SD: 4/78 | SD: 17/78 | |||||||

| Llitjos et al. (12) | France | TD vs. SD | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 26 | TD: 67.5 ± 5.7 | TD: 77.8 | 23 days | 100 | TD: 10/18 | NA | TD: 2/18 |

| SD: 68 ± 6.9 | SD: 75.0 | SD: 8/8 | SD: 1/8 | ||||||||

| Hoogenboom et al. (37) | U.S. | TD vs. SD | Retrospective cohort, single center | 311 | TD: 63.0 (53.0, 72.0) | TD: 71.9 | 144 days | 100 | TD: 12/153 | NA | TD: 73/153 |

| SD: 56.0 (48.0, 67.0) | SD: 66.5 | SD: 3/158 | SD: 44/158 |

Basic characteristics of the included studies.

NA, not available; VTE, venous thromboembolism; TD, therapeutic dose; ID, intermediate dose; SD, standard prophylactic dose. Severity case was defined as (i) need for intensive care unit admission (ii) need for mechanical ventilation with tracheal intubation (iii) CT showing severe lung invasion (iv) acute respiratory failure (v) death (vi) severe and or critical on the basis of the WHO novel grading of the severity of COVID-19. The presence of either of the above items was classified as severe case.

The 19 literature had a total of 25,289 COVID-19 patients, including 12,549 who received standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, 7,758 who received intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, and 4,982 received therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation. The total weighted mean age was 58.27 years. The weighted mean age of standard-dose, intermediate-dose, and therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was 59.84 years, 57.32 years, and 60.74 years, respectively. Males accounted for 59.58% of the total study population. The weighted proportion of males in standard-dose, intermediate-dose, and therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was 57.22%, 60.49%, and 64.09%, respectively. The ICU admission rate was 50.96%. There were 7 studies in the United States, 1 in Saudi Arabia, 1 in Iran, 2 in Brazil, 1 in France, 3 in Spain, 1 in Lebanon, and 3 in multinational cooperative program. The sample size ranged from 20 to 17,130, and the median or mean follow-up time ranged from 30 days to 12 months.

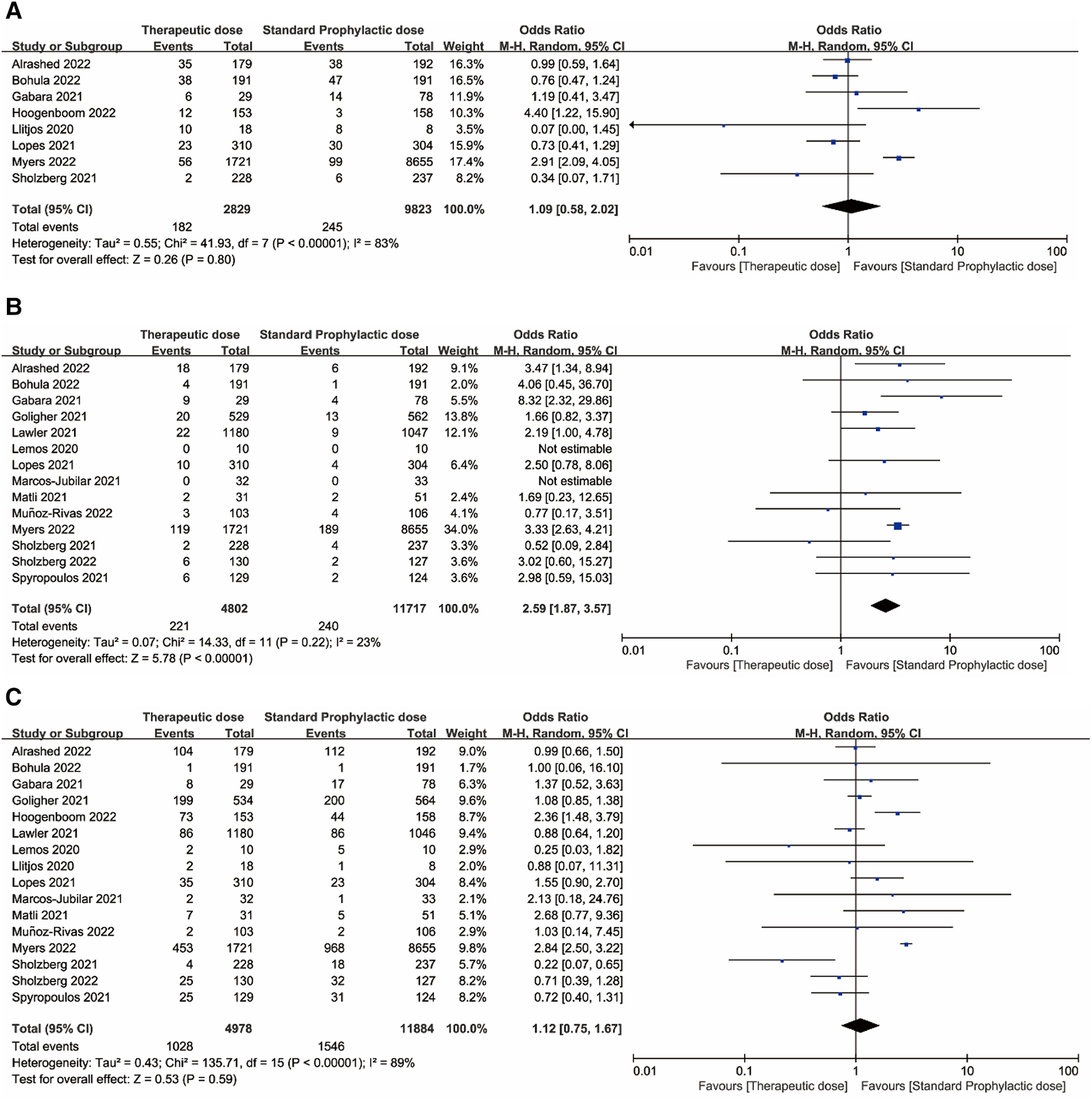

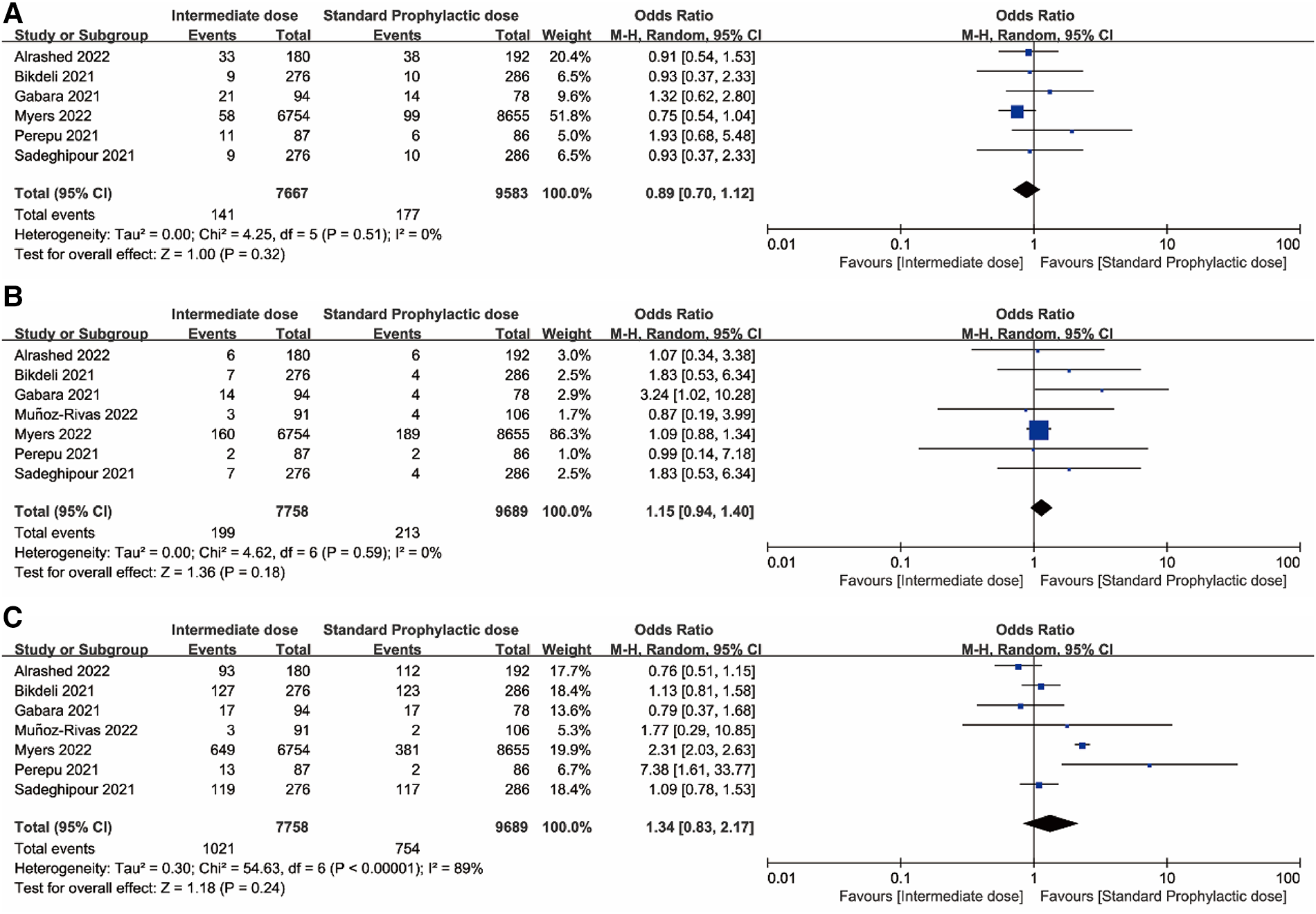

Figures 2, 3 displayed forest plots and the results were as follows. Compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, results of therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation were: (1) VTE: I2 = 83%, P = 0.80, OR = 1.09 (95% CI: 0.58, 2.02); (2) Major bleeding: I2 = 23%, P < 0.00001, OR = 2.59 (95% CI: 1.87, 3.57); (3) Mortality: I2 = 89%, P = 0.59, OR = 1.12 (95% CI: 0.75, 1.67). Compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, results of intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation were: (1) VTE: I2 = 0%, P = 0.32, OR = 0.89 (95% CI: 0.70, 1.12); (2) Major bleeding: I2 = 0%, P = 0.18, OR = 1.15 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.40); (3) Mortality: I2 = 89%, P = 0.24, OR = 1.34 (95% CI: 0.83, 2.17).

Figure 2

(A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality. Forest plots comparing effects of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation regimen.

Figure 3

(A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality. Forest plots comparing effects of intermediate-dose anticoagulation versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation regimen.

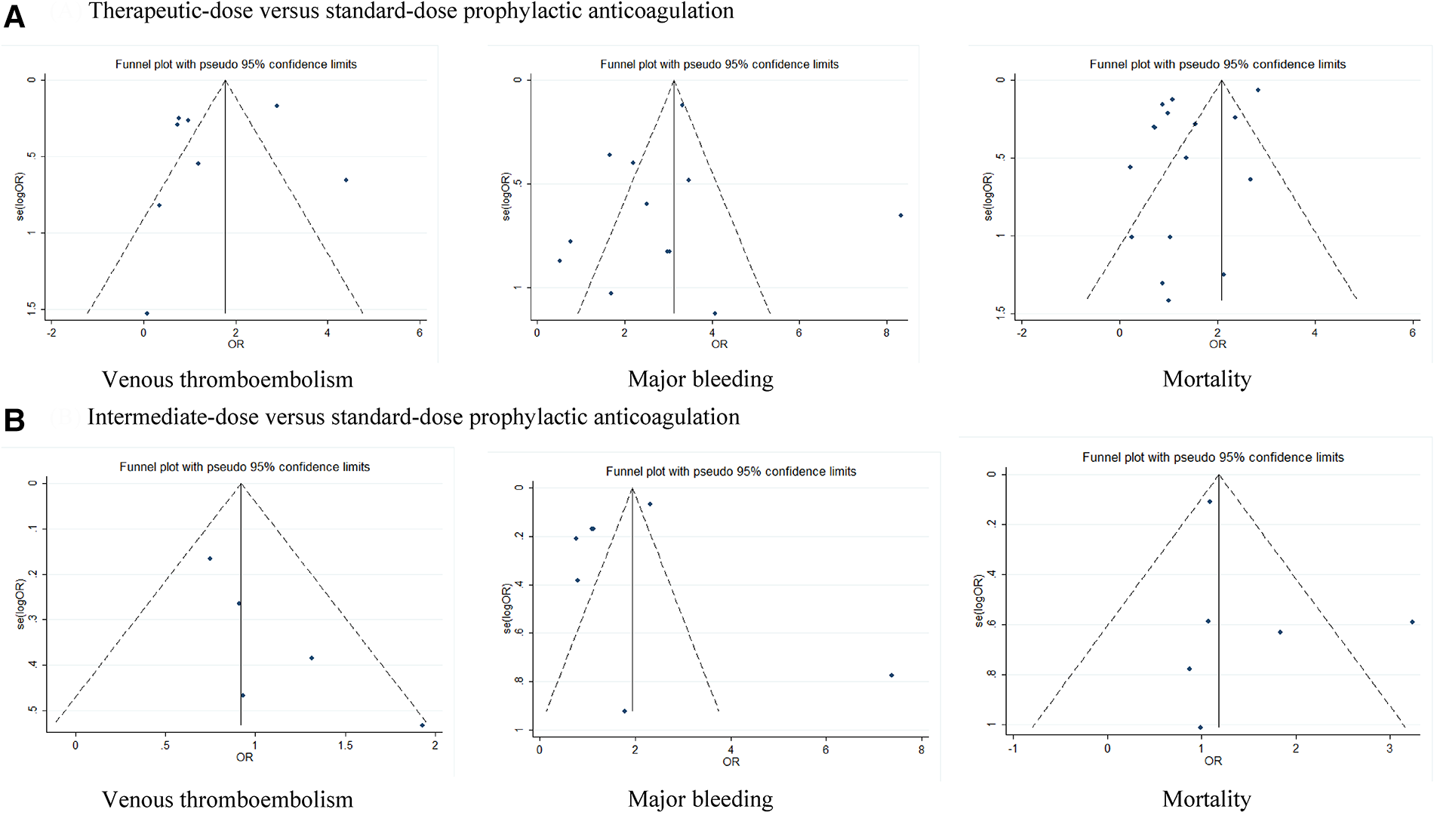

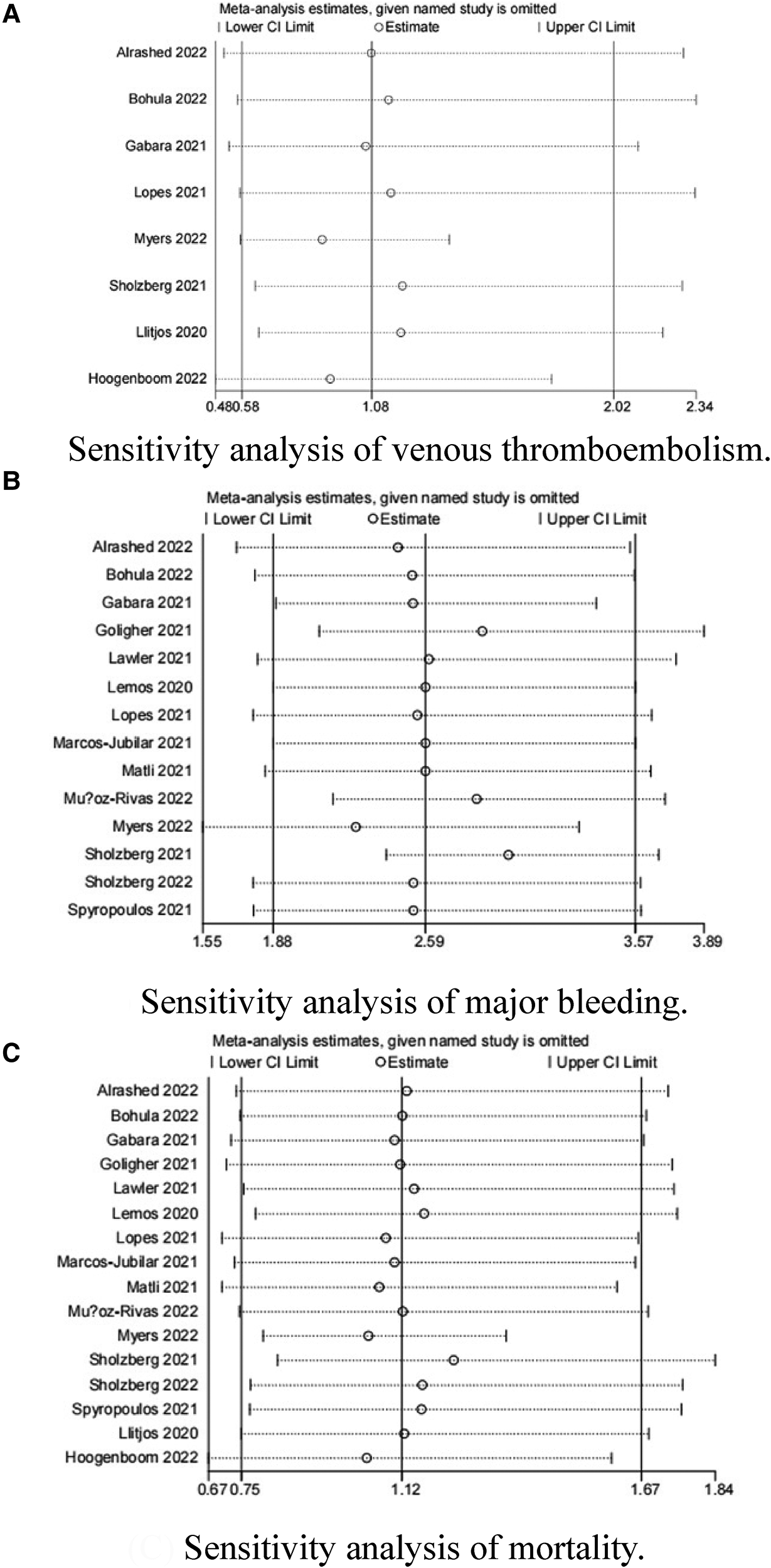

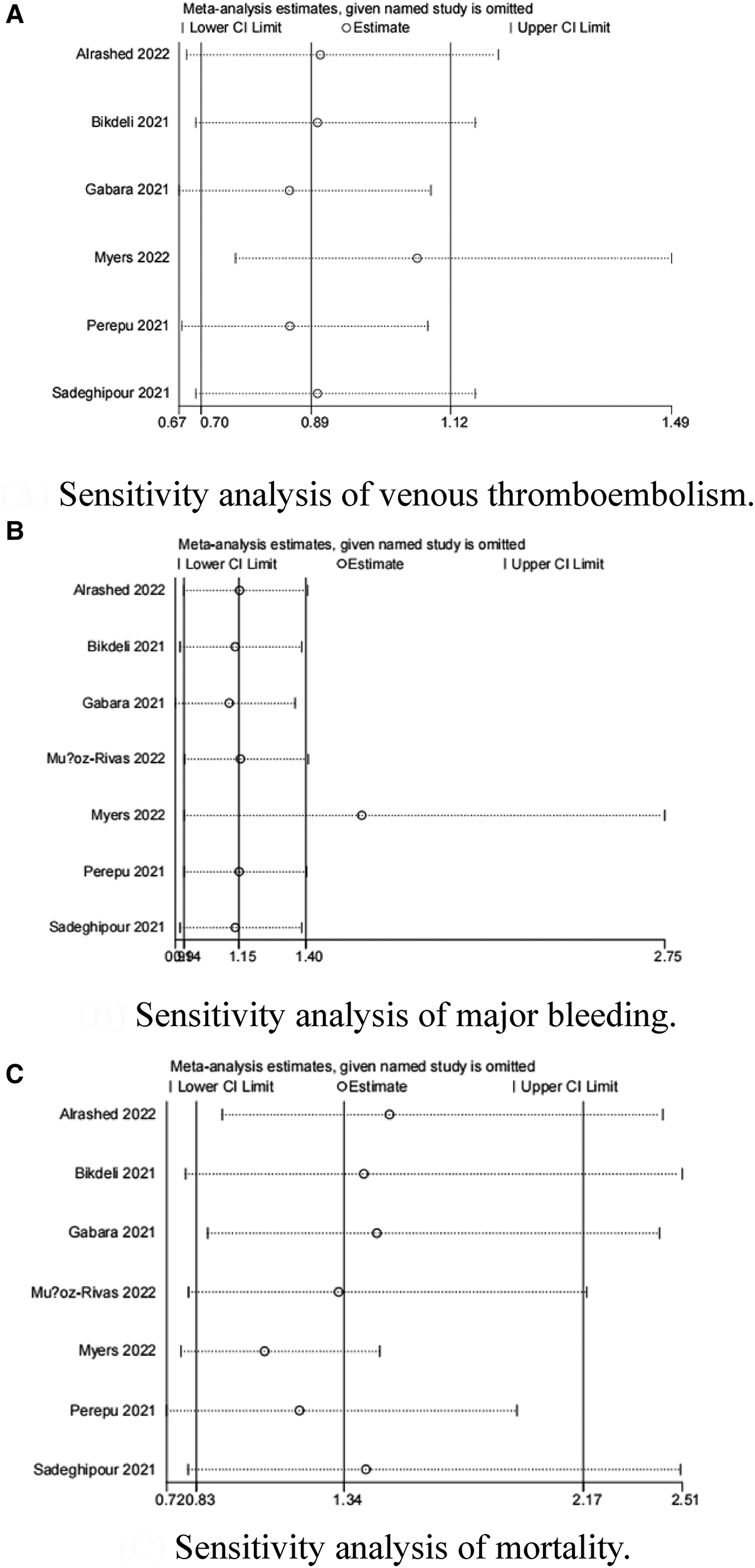

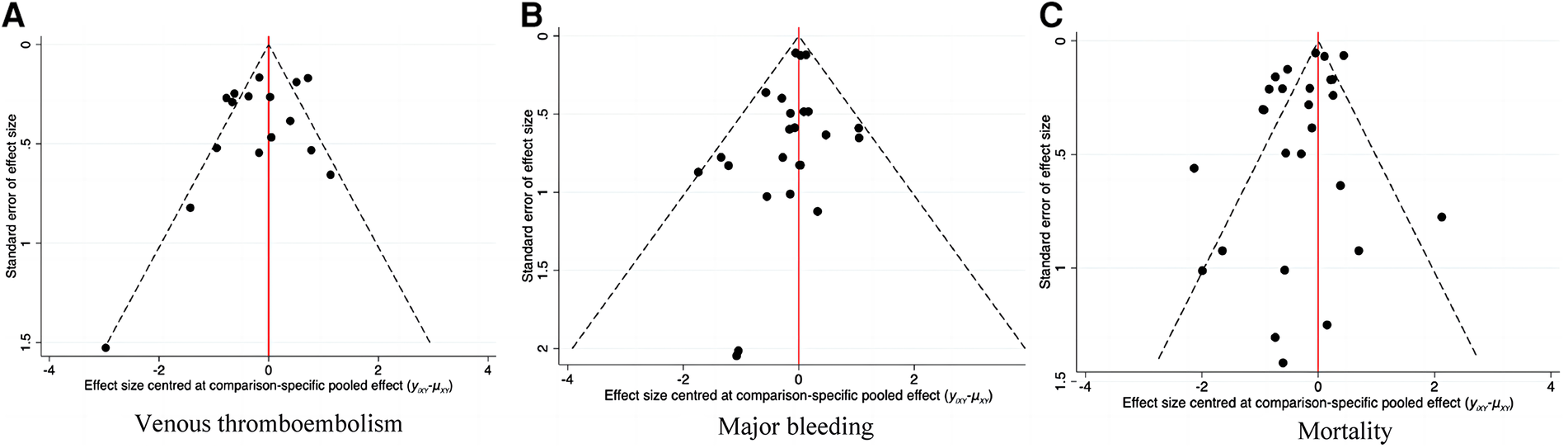

Because the I2 of some forest plots was greater than 50%, we continued to conduct funnel plots (Figure 4) and sensitivity analysis (Figures 5, 6). Results of pairwise comparison between therapeutic-dose and standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation were: (1) VTE: Bohula et al. (33), Gabara et al. (10), Lopes et al. (29), Llitjos et al. (12), and Sholzberg et al. (30) had factors that might affect the results; (2) Major bleeding: Bohula et al. (33), Lopes et al. (29), Matli et al. (32), Marcos-Jubilar et al. (34), Sholzberg et al. (30), Sholzberg et al. (35), and Spyropoulos et al. (16) had factors that might affect the results; (3) Mortality: Bohula et al. (33), Gabara et al. (10), Goligher et al. (27), Lawler et al. (26), Lemos et al. (28), Lopes et al. (29), Marcos-Jubilar et al. (34), Muñoz-Rivas et al. (31), Sholzberg et al. (35), and Spyropoulos et al. (16) had factors that might affect the results. Results of pairwise comparison between therapeutic-dose and standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation were: (1) VTE: combined with I2 = 0.0%, fewer factors might affect the results; (2) Major bleeding: combined with I2 = 0.0%, Gabara et al. (10) had factors that might affect the results; (3) Mortality: Bikdeli et al. (25), Gabara et al. (10), Muñoz-Rivas et al. (31), and Sadeghipour et al. (22) had factors that might affect the results.

Figure 4

Funnel plots: effects of therapeutic-dose, intermediate-dose anticoagulation versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation regimen. (A) Therapeutic-dose versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation. (B) Intermediate-dose versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation.

Figure 5

Sensitivity analysis: therapeutic-dose anticoagulation versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation regimen. (A) Sensitivity analysis of venous thromboembolism. (B) Sensitivity analysis of major bleeding. (C) Sensitivity analysis of mortality.

Figure 6

Sensitivity analysis: intermediate-dose anticoagulation versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation regimen. (A) Sensitivity analysis of venous thromboembolism. (B) Sensitivity analysis of major bleeding. (C) Sensitivity analysis of mortality.

In addition, we also developed NOS for the evaluation of literature quality (Table 3), indicating that the selected articles were of good quality.

Table 3

| Author (publication year) | Adequate definition of cases | Representativeness of the cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Control for important factor | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls | Non-response rate | score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spyropoulos et al. (16) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Sadeghipour et al. (22) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Perepu et al. (23) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Alrashed et al. (24) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Bikdeli et al. (25) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Lawler et al. (26) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Goligher et al. (27) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Lemos et al. (28) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Lopes et al. (29) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Sholzberg et al. (30) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 6 |

| Muñoz-Rivas et al. (31) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Matli et al. (32) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 6 |

| Bohula et al. (33) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Marcos-Jubilar et al. (34) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Sholzberg et al. (35) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Myers et al. (36) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 7 |

| Gabara et al. (10) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 6 |

| Llitjos et al. (12) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Hoogenboom et al. (37) | ★ | ☆ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 6 |

Literature quality assessment by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

★, Means one point; ☆, no point.

Based on the above analysis, we further con ducted a subgroup analysis to identify the source of heterogeneity in terms of elders (65 years), gender, study duration, study design, and ICU admission rate. See Table 4 for the results of the subgroup analysis.

Table 4

| No. of studies | Odds ratio | 95% Cl | p | I2 | Q statistic | P for subgroup | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic dose vs. standard dose | |||||||

| VTE | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age ≥65 years old | 2 | 0.41 | (0.03, 6.56) | 0.53 | 69% | 3.22 | 0.43 |

| Age <65 years old | 6 | 1.29 | (0.62, 2.70) | 0.49 | 85% | 34.44 | |

| ICU admission | |||||||

| ICU admission rate = 100% | 5 | 1.23 | (0.52, 2.91) | 0.63 | 75% | 15.79 | 0.75 |

| ICU admission rate ≠ 100% | 3 | 0.94 | (0.23, 3.88) | 0.94 | 90% | 19.76 | |

| Duration | |||||||

| Duration ≥180 days | 5 | 1.07 | (0.48, 2.39) | 0.86 | 88% | 32.70 | 0.94 |

| Duration <180 days | 3 | 1.15 | (0.22, 6.17) | 0.87 | 71% | 6.88 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male% ≥70% | 4 | 1.66 | (0.68, 4.07) | 0.27 | 58% | 7.17 | 0.36 |

| Male% <70% | 4 | 0.85 | (0.28, 2.59) | 0.77 | 91% | 32.36 | |

| Study type | |||||||

| Randomized clinical trials | 6 | 1.10 | (0.54, 2.23) | 0.79 | 85% | 33.16 | 0.83 |

| Retrospective cohort | 2 | 0.70 | (0.01, 43.89) | 0.87 | 85% | 6.52 | |

| Severity | |||||||

| Critical | 5 | 0.95 | (0.70, 1.30) | 0.76 | 57% | 9.29 | 0.22 |

| Non critical | 1 | 0.34 | (0.07, 1.71) | 0.19 | 54% | NA | |

| Major bleeding event | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age ≥65 years old | 3 | 4.73 | (2.02, 11.09) | <0.001 | 0% | 1.38 | 0.13 |

| Age <65 years old | 11 | 2.32 | (1.60, 3.35) | <0.001 | 32% | 11.76 | |

| ICU admission | |||||||

| ICU admission rate = 100% | 5 | 3.19 | (1.53, 6.63) | 0.002 | 42% | 5.19 | 0.52 |

| ICU admission rate ≠ 100% | 9 | 2.42 | (1.62, 3.60) | <0.001 | 23% | 9.07 | |

| Duration | |||||||

| Duration ≥180 days | 11 | 2.41 | (1.73, 3.36) | <0.001 | 23% | 11.76 | 0.11 |

| Duration <180 days | 3 | 5.65 | (2.07, 15.39) | <0.001 | 0% | 0.94 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male% ≥70% | 5 | 3.21 | (1.34, 7.71) | 0.01 | 61% | 5.07 | 0.67 |

| Male% <70% | 9 | 2.61 | (1.86, 3.65) | <0.001 | 12% | 9.13 | |

| Study type | |||||||

| Randomized clinical trials | 13 | 2.59 | (1.84. 3.65) | <0.001 | 29% | 14.03 | 0.68 |

| Retrospective cohort | 1 | 1.69 | (0.23, 12.65) | 0.61 | NA | NA | |

| Severity | |||||||

| Critical | 5 | 2.78 | (1.73, 4.47) | < 0.001 | 23% | 5.20 | 0.12 |

| Non critical | 5 | 1.49 | (0.81, 2.76) | 0.20 | 37% | 3.16 | |

| Mortality group | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age ≥65 years old | 4 | 0.79 | (0.54, 1.16) | 0.23 | 0% | 1.44 | 0.16 |

| Age <65 years old | 12 | 1.22 | (0.77, 1.93) | 0.40 | 90% | 114.33 | |

| ICU admission | |||||||

| ICU admission rate = 100% | 7 | 1.24 | (0.85, 1.79) | 0.26 | 50% | 12.03 | 0.72 |

| ICU admission rate ≠ 100% | 9 | 1.08 | (0.58, 2.01) | 0.80 | 92% | 96.64 | |

| Duration | |||||||

| Duration ≥180 days | 11 | 1.13 | (0.69, 1.84) | 0.64 | 92% | 119.84 | 0.94 |

| Duration <180 days | 5 | 1.09 | (0.51, 2.32) | 0.83 | 69% | 12.90 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male% ≥70% | 7 | 1.26 | (0.87, 1.82) | 0.23 | 51% | 12.23 | 0.62 |

| Male% <70% | 9 | 1.05 | (0.56,1.95) | 0.88 | 92% | 96.93 | |

| Study type | |||||||

| Randomized clinical trials | 13 | 0.98 | (0.62, 1.55) | 0.93 | 91% | 133.97 | 0.01 |

| Retrospective cohort | 3 | 2.33 | (1.51, 3.60) | <0.001 | 0% | 0.62 | |

| Severity | |||||||

| Critical | 7 | 1.16 | (0.97, 1.38) | 0.11 | 52% | 12.51 | 0.02 |

| Noncritical | 5 | 1.03 | (0.57, 1.01) | 0.06 | 49% | 7.77 | |

| Intermediate dose vs. standard dose | |||||||

| VTE | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age ≥65 years old | 2 | 1.50 | (0.81, 2.77) | 0.19 | 0% | 0.34 | 0.10 |

| Age <65 years old | 4 | 0.86 | (0.66, 1.11) | 0.70 | 5% | 2.21 | |

| ICU admission | |||||||

| ICU admission rate = 100% | 4 | 1.14 | (0.78, 1.66) | 0.50 | 0% | 0.58 | 0.87 |

| ICU admission rate ≠ 100% | 2 | 1.05 | (0.43, 2.56) | 0.91 | 65% | 2.89 | |

| Duration | |||||||

| Duration ≥180 days | 3 | 1.04 | (0.63, 1.72) | 0.88 | 54% | 4.39 | 0.92 |

| Duration <180 days | 3 | 1.08 | (0.66, 1.76) | 0.77 | 0% | 0.46 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male% ≥70% | 2 | 1.26 | (0.80, 2.00) | 0.32 | 0% | 0.02 | 0.70 |

| Male% <70% | 4 | 0.84 | (0.63, 1.11) | 0.22 | 1% | 3.02 | |

| Severity | |||||||

| Critical | 4 | 1.00 | (0.70, 1.42) | 0.98 | 0% | 0.68 | 0.24 |

| Noncritical | 1 | 1.07 | (0.77, 1.50) | 0.22 | NA | NA | |

| Major Bleeding group | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age ≥65 years old | 2 | 2.38 | (0.86, 6.60) | 0.10 | 3% | 1.03 | 0.15 |

| Age <65 years old | 5 | 1.11 | (0.91, 1.36) | 0.30 | 0% | 1.40 | |

| ICU admission | |||||||

| ICU admission rate = 100% | 4 | 1.85 | (1.02, 3.35) | 0.04 | 0% | 1.78 | 0.10 |

| ICU admission rate ≠ 100% | 3 | 1.08 | (0.88, 1.33) | 0.47 | 0% | 0.09 | |

| Duration | |||||||

| Duration ≥180 days | 4 | 1.08 | (0.88, 1.33) | 0.46 | 0% | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Duration <180 days | 3 | 2.26 | (1.12, 4.54) | 0.02 | 0% | 0.59 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male% ≥70% | 2 | 1.86 | (0.63, 5.52) | 0.26 | 44% | 1.78 | 0.36 |

| Male% <70% | 5 | 1.11 | (0.91, 1.36) | 0.31 | 0% | 1.41 | |

| Severity | |||||||

| Critical | 4 | 1.89 | (1.05, 3.39) | 0.03 | 0% | 1.78 | 0.29 |

| Noncritical | 2 | 0.91 | (0.27, 3.05) | 0.06 | 0% | 0.01 | |

| Mortality group | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Age ≥65 years old | 2 | 2.19 | (0.24, 20.16) | 0.49 | 85% | 6.90 | 0.64 |

| Age <65 years old | 5 | 1.27 | (0.75, 2.15) | 0.38 | 91% | 0.38 | |

| ICU admission | |||||||

| ICU admission rate = 100% | 4 | 1.00 | (0.82, 1.21) | 0.96 | 0% | 2.83 | <0.001 |

| ICU admission rate ≠ 100% | 3 | 2.49 | (1.59, 3.90) | <0.001 | 14% | 2.31 | |

| Duration | |||||||

| Duration ≥180 days | 4 | 1.87 | (0.79, 4.44) | 0.15 | 89% | 28.11 | 0.22 |

| Duration <180 days | 3 | 1.08 | (0.86, 1.35) | 0.51 | 0% | 0.73 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male% ≥70% | 2 | 0.77 | (0.54, 1.10) | 0.15 | 0% | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Male% <70% | 5 | 1.68 | (1.00, 2.83) | 0.05 | 87% | 31.08 | |

| Severity | |||||||

| Critical | 4 | 1.00 | (0.82, 1.21) | 0.96 | 0% | 2.83 | 0.01 |

| Noncritical | 2 | 4.51 | (1.48, 13.80) | 0.008 | 30% | 1.42 |

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes.

Bold values indicate significant p-values < 0.05.

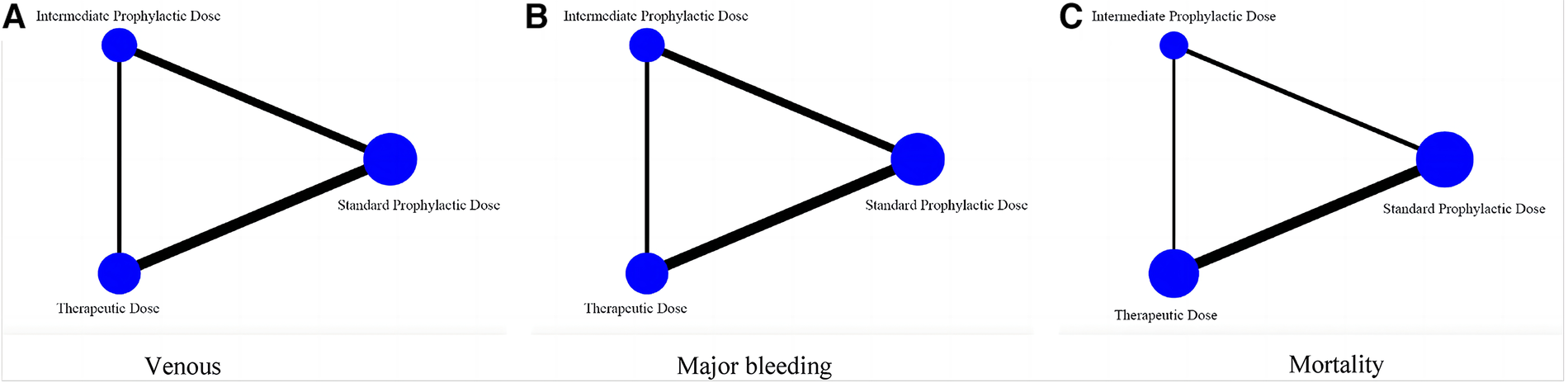

The main purpose of network meta-analysis was to compare the difference between therapeutic-dose and intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation. Further, ranking and surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) probabilities were performed to carry out the recommended order of the three doses after evaluation of the incidence of VTE, major bleeding and mortality.

As shown in Figure 7, this network meta-analysis had a closed-loop structure, so its results were to merge the direct and indirect comparisons and make decisions accordingly.

Figure 7

Network meta-analysis diagram comparing efficacy and safety of three prophylactic anticoagulation regimen for COVID-19 patients. (A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality.

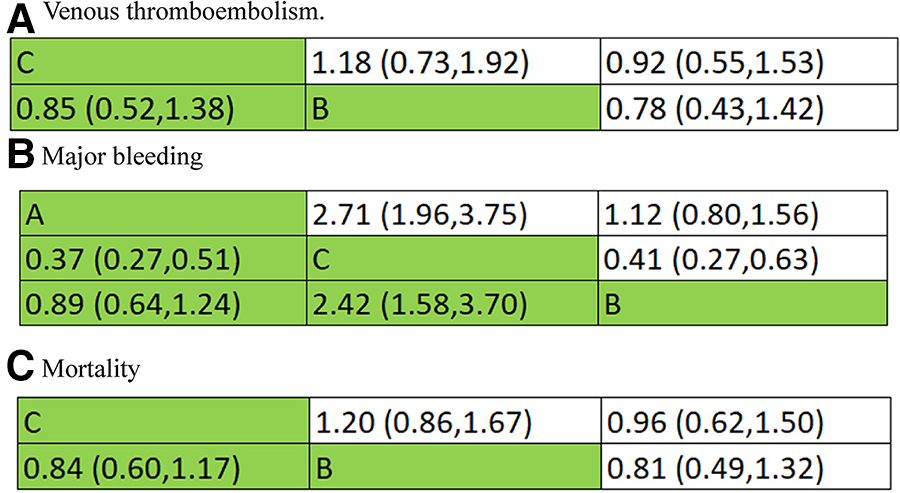

Combined with the inverted triangle plot (Figure 8), compared with intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, OR and 95%CI of VTE, major bleeding and mortality in therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.52, 1.38), 2.42 (95% CI: 1.58, 3.70) and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.60, 1.17).

Figure 8

Inverted triangle plot of network meta-analysis: therapeutic-dose versus intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation regimen. (A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality.

The adjusted funnel plot in Figure 9 pointed out no evidence of publication bias in our included articles.

Figure 9

Corrected funnel plot of network meta-analysis. (A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality.

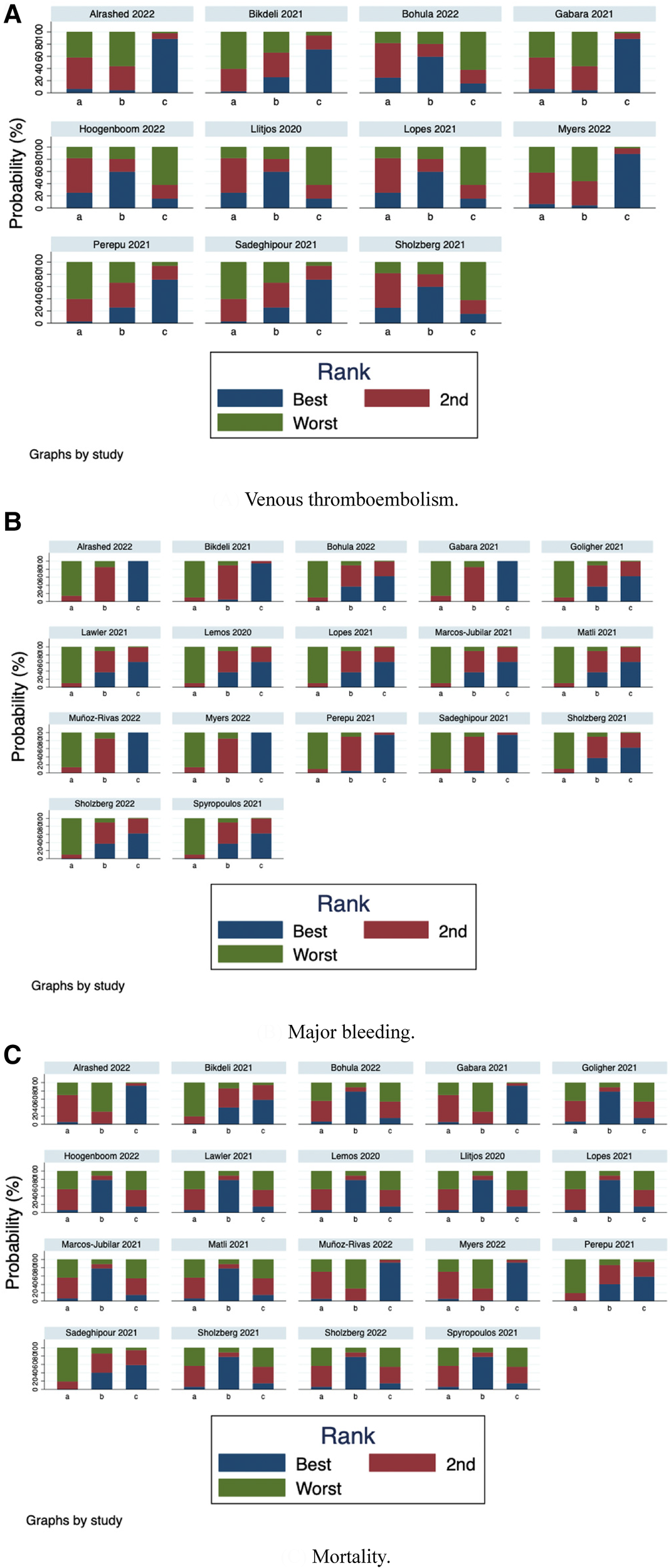

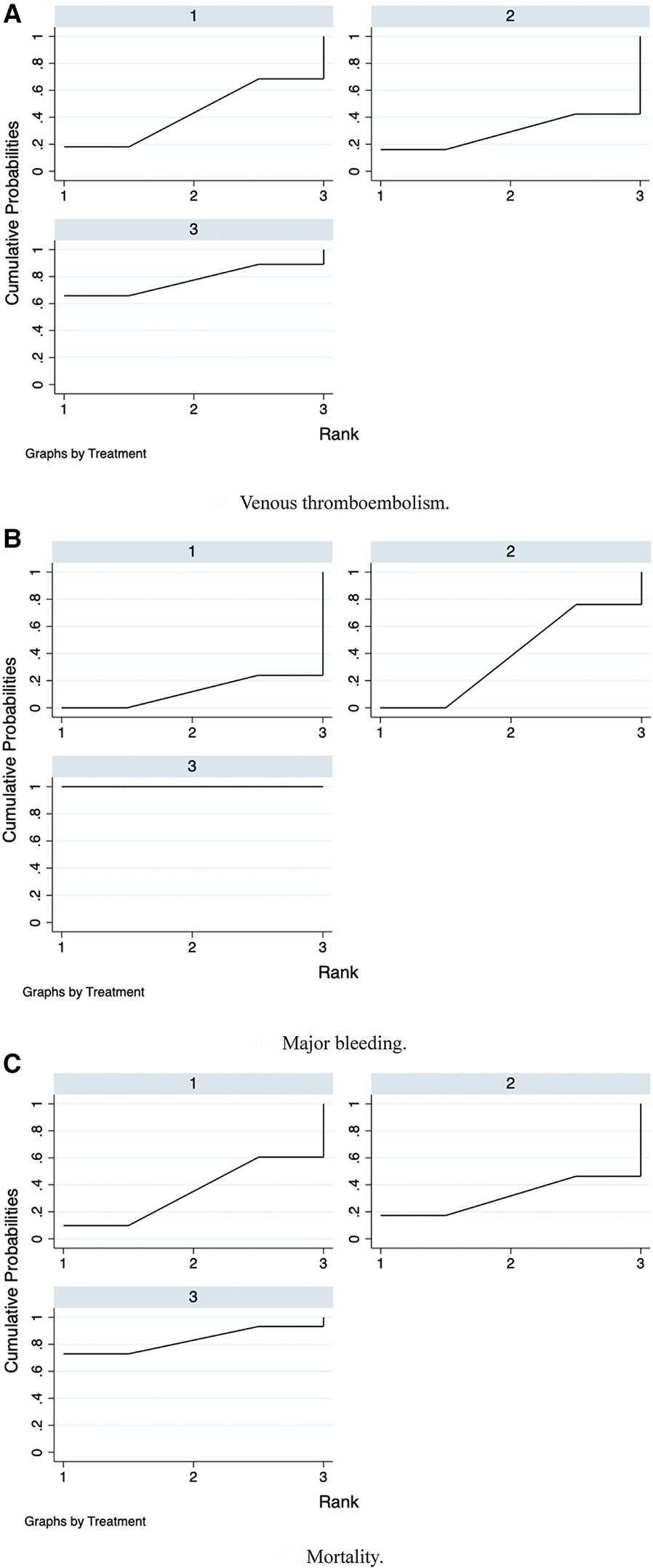

Furthermore, we ranked the impact of three doses of prophylactic anticoagulation on VTE, major bleeding, and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Ranking and SUCRA were shown in Figures 10, 11, separately.

Figure 10

Rank-order plot of network meta-analysis. (A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality.

Figure 11

SUCRA plots of network meta-analysis. (A) Venous thromboembolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Mortality.

4 Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 infection can not only cause multiple organ damage (38), but greatly increase the risk of VTE. As early as the begin ning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, studies from Wuhan, China, initially revealed that COVID-19 patients had a high risk of VTE (39), which was gradually confirmed with the outbreak all over the world. Marchandot et al. (40) summarized studies on hospitalized COVID-19 patients from different countries and found that the incidence of VTE in non-ICU and ICU patients was 3%–46% and 15%–85%, separately. Nopp et al. (41) conducted a meta-analysis of 66 clinical studies with 28,173 COVID-19 patients and indicated that the overall incidence of VTE was 14.1%. Among them, the incidence of VTE was 40.3% if lower extremity venous color Doppler ultrasound screening was used, and 9.5% if no ultrasound screening was used. Stals MAM et al. (42) analyzed 3 ho spitals in the Netherlands and reported that the incidence of VTE in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was 18.7%, while that in hospitalized patients with influenza from 2013 to 2018 was only 1.04%. Although the incidence of VTE varies from study to study, there is a consensus that the risk of VTE remains higher in COVID-19 patients, and the more severe the disease, the higher the risk (43).

On the other hand, the prognosis of COVID-19 patients tends to be worse if VTE occurs. A study (44) from Wuhan, China, enrolled 143 COVID-19 cases in the ICU and noted that compared with patients without DVT, the mortality of those who had comorbid DVT was significantly higher (34.8% vs.11.7%, P = 0.001). Kollias A et al. (45) developed a meta-analysis of more than 6,000 patients and revealed that the incidence of PE and DVT in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was 32% and 27%, respectively, and the risk of death was twice higher if VTE was accompanied. Even if VTE is not the direct cause of death, it may be an important cause. Lax et al. (46) from Australia analyzed an autopsy study on 11 patients who died of COVID-19 and proved that all patients had comorbid PE (46). Wichmann et al. (8) published an autopsy report on 12 patients who died of COVID-19, showing that 58% had DVT and 33% died of PE rather than COVID-19. Therefore, early scientific and reasonable prevention and treatment of VTE is essential to improve the prognosis of COVID-19. However, since VTE and COVID-19 share many vital signs and clinical symptoms, it becomes difficult to identify in the early stage, so prophylactic anticoagulation emerges as the times require. With the growing evidence on the association between prophylactic anticoagulation and lower mortality among COVID-19 patients, the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) (47) and American College of Clinical Pharma (ACCP) (48, 49) have issued relevant clinical guidelines or expert consensus and recommended standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation for all hospitalized COVID-19 patients if there is no contraindication. In clinical practice, however, VTE still occurs in some hospitalized cases receiving standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (12, 47, 50). Considering the high incidence of COVID-19 combined with VTE and the high mortality due to disease progression, prophylactic anticoagulation with higher doses than standard has been carried out in many hospitals (49, 51), which may place patients at higher risk for major bleeding (13, 15, 52). Controversy exists regarding which thromboprophylaxis treatment can achieve better clinical benefits in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Benefits from the use of standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 remain controversial. Almohareb et al. (9) and Gabara et al. (10) both supported standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients, the former confirmed that increasing dose over the standard was not associated with reduced mortality, and the latter implied that the use of intermediate-dose and therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation seemed to have a higher risk of bleeding in critical COVID-19 cases. Cohen et al. (11) identified that compared with treatment-dose anticoagulation, prophylactic-dose anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients could reduce VTE or mortality. On the contrary, Llitjos et al. (12) documented that the proportion of VTE was significantly higher in patients treated with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation than in other groups (i.e., intermediate-dose and therapeutic-dose).

The advantages of intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 have not reached an agreement. Hamilton et al. (53) expressed that compared with standard-dose, intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis in critical COVID-19 patients could have better levels of anti-FXa. A randomized clinical trial by Engelen et al. (14) displayed that in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, no additional symptomatic VTE occurred after the implementation of a systematic weight-adjusted thromboprophylaxis (prophylactic-dose in the general ward and intermediate-dose in ICU), and collateral DVT reduced. Al-Dorzi et al. (50) described the benefits of intermediate-dose enoxaparin in reducing VTE and mortality than standard-dose unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin in patients with severe COVID-19. However, the results of Aljuhani et al. (54) concluded that compared with the standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was not associated with thrombosis or mortality in critical COVID-19, but increased risk of minor bleeding. Al-Abani et al. (13) performed ultrasound on COVID-19 patients in ICU with intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation and illustrated that patients still had a high incidence of VTE and bleeding complications.

Consensus is needed regarding the efficacy of therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19. Spyropoulos et al. (16) initiated a randomized clinical trial on COVID-19 patients and showed that therapeutic-doses of low-molecular-weight heparin could reduce thromboembolism and death. However, a prospective observational study by Kumar et al. (55) interpreted that the use of therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 did not reduce the incidence of VTE, but was associated with higher in-hospital mortality. In a retrospective study of 1,121 patients in 33 hospitals, Parks et al. (15) proposed that compared with other anticoagulation regimens, the incidence of VTE and bleeding in COVID-19 patients receiving therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was three times and five times higher, separately.

This meta-analysis included 19 studies published between January 1, 2020, and October 31, 2022. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis conducting a p airwise comparison among three conventional prophylactic anticoagulations in the incidence of VTE, major bleeding, and mortality. This meta-analysis included 19 related studies with 25,289 COVID-19 patients, and the results showed that: (1) compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of VTE, major bleeding and mortality in therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was 1.09 (95% CI: 0.58, 2.02), 2.59 (95% CI: 1.87, 3.57) and 1.12 (95% CI: 0.75, 1.67), respectively; (2) compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, OR and 95%CI of VTE, major bleeding and mortality in intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.70, 1.12), 1.15 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.40) and 1.34 (95% CI: 0.83, 2.17), respectively; (3) compared with intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, OR and 95%CI of VTE, major bleeding and mortality in therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation was0.85 (95% CI: 0.52, 1.38), 2.42 (95% CI: 1.58, 3.70) and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.60, 1.17). The above results suggested that compared with COVID-19 patients receiving intermediate-dose or therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, those who underwent standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation had the lowest risk of bleeding events. In terms of VTE and mortality, no significant differences were found.

We further ranked the impact of the three doses of anticoagulation on VTE, major bleeding, and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Combining the results of ranking (Figure 10) and SUCRA (Figure 11), the order of probability of VTE events from high to low was: therapeutic-dose >> standard-dose > intermediate-dose. The order of probability of major bleeding events from high to low was: therapeutic-dose > intermediate-dose >> standard-dose. The order of probability of death events from high to low was: therapeutic-dose >> standard-dose > intermediate-dose. This ranking result further validated the previous results.

To verify the applicability of the above results, we conducted a subgroup analysis in terms of age, ICU admission rate, hospital stay, etc. It is worth noting that compared with the standard dose, although therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation increased the risk of major bleeding, it could significantly reduce VTE formation in patients over 65 years of age.

To sum up, consistent with ISTH guidelines and ACCP guidelines (49), we recommended a standard-dose rather than an above-standard dose (i.e., intermediate-dose or therapeutic-dose) for prophylactic anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients who received no anticoagulation therapy within 6 months before admission. Only for elderly COVID-19 patients with low bleeding risk and high VTE risk, we recommended therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation. In addition, the Caprini score is the most validated VTE risk assessment tool and has been used to evaluate the risk of VTE in approximately 5 million medical and surgical patients worldwide. Since COVID-19 patients are themselves at high risk for VTE, the revised Caprini Score has been tailored to the initial Caprini Score (2005 version), with the addition of a score for elevated D-dimer and a score for COVID-19 infections, specifically: asymptomatic infections are considered to be a 2-point score, symptomatic infections are considered to be a 3-point score, and symptomatic infections combined with elevated D-dimer are 5 points were considered (56). Based on this score, the risk of VTE in COVID-19 patients can be further evaluated and guide the application of clinical anticoagulation programs. Therefore, it is scientific and reasonable to provide standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation for all hospitalized patients in a timely manner, to increase the dose individually for elderly patients with a high risk of VTE or acceptable risk of bleeding, as well as to adjust the dose according to the patient's weight and the disease progression. It is expected that there will be a higher level of evidence to verify our conclusion in the future.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the prevalence of thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients was likely to be underestimated. The possible reason was that the incidence of thrombotic events (e.g., PE, DVT, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and other thromboembolism) diagnosed with routine clinical care was often less than that seen on computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Second, we could only obtain a preliminary conclusion from our included articles on the comparison between therapeutic-dose or intermediate-dose and standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, as well as the comparison between therapeutic-dose and intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation from the network meta-analysis. Meanwhile, considering the limited number of relevant clinical studies and the presence of heterogeneity, follow-up large-scale studies are required to further explore the safety and effectiveness of different treatments, so as to guide clinical practice and improve the disease status. Third, we encountered high statistical heterogeneity during the meta-analysis. Despite we conducted a prespecified sensitivity analysis, these failed to adequately explain such heterogeneity. This residual heterogeneity might derive from sources of variation between studies, most notably because of age, gender, race, lack of continuous registration, clinical measurements, nursing level, virus strains, and disease severity. Finally, most included studies were rated as having a moderate risk of bias, reflecting generally low methodological quality. The underlying explanations were the lack of control for confounders, inconsistent or unclear context in VTE evaluations, and possible selection bias due to the absence of continuous patient registration.

5 Conclusion

In terms of prevention and treatment of VTE, this study pointed out that COVID-19 patients in general could not benefit more from intermediate-dose or therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation than standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, while elderly COVID-19 patients with low bleeding risk and high VTE risk appeared to benefit more from therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation. Therefore, we suggested that individualized adjustment should be performed based on the standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation according to the specific conditions of COVID-19 patients. At the same time, this meta-analysis further supported the expert consensus of ACCP guidelines that patients with COVID-19 should still receive standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, while non-critically ill patients with low bleeding risk might benefit from therapeutic-dose prophylactic anticoagulation. In summary, this meta-analysis only provided a preliminary conclusion for reference due to the objective limitations of different health service levels, types of strains, types, and doses of vaccines, presence of thromboprophylaxis, and thromboprophylaxis regimens. Further studies will still have positive clinical implications for COVID-19 patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

XC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This study was supported by a grant from Fujian Provincial Health Scientific and Technological Guidance Projects (Project No. 2021Y0098).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Zhu N Zhang D Wang W Li X Yang B Song J et al A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382(8):727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

2.

Ortel TL Neumann I Ageno W Beyth R Clark NP Cuker A et al American society of hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. (2020) 4(19):4693–738. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001830

3.

Konstantinides SV Meyer G Becattini C Bueno H Geersing GJ Harjola VP et al 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European respiratory society (ERS). Eur Heart J. (2020) 41(4):543–603. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405

4.

Chen N Zhou M Dong X Qu J Gong F Han Y et al Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. (2020) 395(10223):507–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7

5.

Kyriakoulis KG Kollias A Kyriakoulis IG Kyprianou IA Papachrysostomou C Makaronis P et al Thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19: systematic review of national and international clinical guidance reports. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. (2022) 20(1):96–110. 10.2174/1570161119666210824160332

6.

Jiménez D García-Sanchez A Rali P Muriel A Bikdeli B Ruiz-Artacho P et al Incidence of VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. (2021) 159(3):1182–96. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.005

7.

Bikdeli B Madhavan MV Jimenez D Chuich T Dreyfus I Driggin E et al COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75(23):2950–73. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031

8.

Wichmann D Sperhake JP Lütgehetmann M Steurer S Edler C Heinemann A et al Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173(4):268–77. 10.7326/M20-2003

9.

Almohareb SN Al Yami MS Assiri AM Almohammed OA . Impact of thromboprophylaxis intensity on patients’ mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a propensity-score matched study. Clin Epidemiol. (2022) 14:361–8. 10.2147/CLEP.S359132

10.

Gabara C Solarat B Castro P Fernández S Badia JR Toapanta D et al Anticoagulation strategies and risk of bleeding events in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Medicina Intensiva. (2023) 47(1):1–8. 10.1016/j.medin.2021.07.004

11.

Cohen SL Gianos E Barish MA Chatterjee S Kohn N Lesser M et al Prevalence and predictors of venous thromboembolism or mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Thromb Haemostasis. (2021) 121(08):1043–53. 10.1055/a-1366-9656

12.

Llitjos JF Leclerc M Chochois C Monsallier JM Ramakers M Auvray M et al High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2020) 18(7):1743–6. 10.1111/jth.14869

13.

Al-Abani K Kilhamn N Maret E Mårtensson J . Thrombosis and bleeding after implementation of an intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation protocol in ICU patients with COVID-19: a multicenter screening study. J Intensive Care Med. (2022) 37(4):480–90. 10.1177/08850666211051960

14.

Engelen MM Vandenbriele C Spalart V Martens CP Vandenberk B Sinonquel P et al Thromboprophylaxis in COVID-19: weight and severity adjusted intensified dosing. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. (2022) 6(3):e12683. 10.1002/rth2.12683

15.

Parks AL Auerbach AD Schnipper JL Bertram A Jeon SY Boyle B et al Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention and diagnosis in COVID-19: practice patterns and outcomes at 33 hospitals. PLoS One. (2022) 17(5):e0266944. 10.1371/journal.pone.0266944

16.

Spyropoulos AC Goldin M Giannis D Diab W Wang J Khanijo S et al Efficacy and safety of therapeutic-dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the HEP-COVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. (2021) 181(12):1612. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6203

17.

Cumpston M Li T Page MJ Chandler J Welch VA Higgins JP et al Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 10(10):ED000142. 10.1002/14651858.ED000142

18.

Moher D Shamseer L Clarke M Ghersi D Liberati A Petticrew M et al Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. (2015) 4(1):1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

19.

Wan X Wang W Liu J Tong T . Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range, and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2014) 14(1):135. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

20.

Jonmarker S Hollenberg J Dahlberg M Stackelberg O Litorell J Everhov ÅH et al Dosing of thromboprophylaxis and mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Critical Care. (2020) 24:653. 10.1186/s13054-020-03375-7

21.

Blondon M Cereghetti S Pugin J Marti C Darbellay Farhoumand P Reny JL et al Therapeutic anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis, coagulopathy, and mortality in severe COVID-19: the Swiss COVID-HEP randomized clinical trial. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. (2022) 6(4):e12712. 10.1002/rth2.12712

22.

INSPIRATION Investigators . Durable functional limitation in patients with coronavirus disease-2019 admitted to intensive care and the effect of intermediate-dose vs standard-dose anticoagulation on functional outcomes. Eur J Intern Med. (2022) 103:76–83. 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.06.014

23.

Perepu US Chambers I Wahab A Ten Eyck P Wu C Dayal S et al Standard prophylactic versus intermediate dose enoxaparin in adults with severe COVID-19: a multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2021) 19(9):2225–34. 10.1111/jth.15450

24.

Alrashed A Cahusac P Mohzari YA Bamogaddam RF Alfaifi M Mathew M et al A comparison of three thromboprophylaxis regimens in critically ill COVID-19 patients: an analysis of real-world data. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:978420. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.978420

25.

Bikdeli B Talasaz AH Rashidi F Bakhshandeh H Rafiee F Rezaeifar P et al Intermediate-dose versus standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit: 90-day results from the INSPIRATION randomized trial. Thromb Haemostasis. (2022) 122(01):131–41. 10.1055/a-1485-2372

26.

The ATTACC, ACTIV-4a, REMAP-CAP Investigators. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385(9):790–802. 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911

27.

The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, ATTACC Investigators. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385(9):777–89. 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417

28.

Lemos ACB do Espírito Santo DA Salvetti MC Gilio RN Agra LB Pazin-Filho A et al Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for severe COVID-19: a randomized phase II clinical trial (HESACOVID). Thromb Res. (2020) 196:359–66. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.026

29.

Lopes RD de Barros E Silva PGM Furtado RHM Macedo AVS Bronhara B Damiani LP et al Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer concentration (ACTION): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. (2021) 397(10291):2253–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01203-4

30.

Sholzberg M Tang GH Rahhal H AlHamzah M Kreuziger LB Áinle FN et al Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospital: rAPID randomised clinical trial. Br Med J. (2021) 375:n2400. 10.1136/bmj.n2400

31.

Izumo T Awano N Kuse N Sakamoto K Takada K Muto Y et al Efficacy and safety of sotrovimab for vaccinated or unvaccinated patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in the omicron era. Drug Discov Ther. (2022) 16(3):124–7. 10.5582/ddt.2022.01036

32.

Matli K Chamoun N Fares A Zibara V Al-Osta S Nasrallah R et al Combined anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy is associated with an improved outcome in hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a propensity matched cohort study. Open Heart. (2021) 8(2):e001785. 10.1136/openhrt-2021-001785

33.

Bohula EA Berg DD Lopes MS Connors JM Babar I Barnett CF et al Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for prevention of venous and arterial thrombotic events in critically ill patients with COVID-19: cOVID-PACT. Circulation. (2022) 146(18):1344–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061533

34.

Marcos-Jubilar M Carmona-Torre F Vidal R Ruiz-Artacho P Filella D Carbonell C et al Therapeutic versus prophylactic bemiparin in hospitalized patients with nonsevere COVID-19 pneumonia (BEMICOP study): an open-label, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Thromb Haemostasis. (2022) 122(02):295–9. 10.1055/a-1667-7534

35.

Sholzberg M Tang GH Rahhal H AlHamzah M Kreuziger LB Ní Āinle F et al Heparin for moderately Ill patients with COVID-19. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2021). 10.1101/2021.07.08.21259351

36.

Myers LC Xu S Chen A Greene JD Creekmur B Bruxvoort K et al The intensity of anticoagulant dosing in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: an observational, comparative effectiveness study. J Hosp Med. (2023) 18(1):43–54. 10.1002/jhm.13007

37.

Hoogenboom WS Lu JQ Musheyev B Borg L Janowicz R Pamlayne S et al Prophylactic versus therapeutic dose anticoagulation effects on survival among critically ill patients with COVID-19. PLoS One. (2022) 17(1):e0262811. 10.1371/journal.pone.0262811

38.

Stein SR Ramelli SC Grazioli A Chung JY Singh M Yinda CK et al SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy. Nature. (2022):612. (7941): 758–63. 10.1038/s41586-022-05542-y

39.

Yu Y Tu J Lei B Shu H Zou X Li R et al Incidence and risk factors of deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2020) 26:107602962095321. 10.1177/1076029620953217

40.

Marchandot B Trimaille A Curtiaud A Matsushita K Jesel L Morel O . Thromboprophylaxis: balancing evidence and experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2020) 50(4):799–808. 10.1007/s11239-020-02231-3

41.

Nopp S Moik F Jilma B Pabinger I Ay C . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. (2020) 4(7):1178–91. 10.1002/rth2.12439

42.

Stals MAM Grootenboers MJJH van Guldener C Kaptein FHJ Braken SJE Chen Q et al Risk of thrombotic complications in influenza versus COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. (2021) 5(3):412–20. 10.1002/rth2.12496

43.

Helms J Tacquard C Severac F Leonard-Lorant I Ohana M Delabranche X et al High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46(6):1089–98. 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x

44.

Zhang L Sun W Zhang Y Wu C Li Y Xie M . Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Circulation. (2020) 142(2):114–28. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046702

45.

Kollias A Kyriakoulis KG Lagou S Kontopantelis E Stergiou GS Syrigos K . Venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Med. (2021) 26(4):415–25. 10.1177/1358863X21995566

46.

Lax SF Skok K Zechner PM Trauner M . Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 with fatal outcome: results from a prospective, single-center, clinicopathologic case series. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173(5):350–61. 10.7326/M20-2566

47.

Spyropoulos AC Levy JH Ageno W Connors JM Hunt BJ Iba T et al Scientific and standardization committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2020) 18(8):1859–65. 10.1111/jth.14929

48.

Moores LK Tritschler T Brosnahan S Carrier M Collen JF Doerschug K et al Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. (2020) 158(3):1143–63. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559

49.

Moores LK Tritschler T Brosnahan S Carrier M Collen JF Doerschug K et al Thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. Chest. (2022) 162(1):213–25. 10.1016/j.chest.2022.02.006

50.

Al-Dorzi HM Alqirnas MQ Hegazy MM Alghamdi AS Alotaibi MT Albogami MT et al Prevalence and risk factors of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 and the association between the dose of anticoagulants and outcomes. J Crit Care Med (Targu Mures). (2022) 8(4):249–58. 10.2478/jccm-2022-0023

51.

Burnett AE Mahan CE Vazquez SR Oertel LB Garcia DA Ansell J . Guidance for the practical management of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in VTE treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2016) 41(1):206–32. 10.1007/s11239-015-1310-7

52.

Parisi R Costanzo S Di Castelnuovo A de Gaetano G Donati MB Iacoviello L . Different anticoagulant regimens, mortality, and bleeding in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and an updated meta-analysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. (2021) 47(04):372–91. 10.1055/s-0041-1726034

53.

Hamilton DO Main-Ian A Tebbutt J Thrasher M Waite A Welters I . Standard- versus intermediate-dose enoxaparin for anti-factor Xa guided thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Thromb J. (2021) 19(1):87. 10.1186/s12959-021-00337-z

54.

Aljuhani O Al Sulaiman K Hafiz A Eljaaly K Alharbi A Algarni R et al Comparison between standard vs. Escalated dose venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a two centers, observational study. Saudi Pharm J. (2022) 30(4):398–406. 10.1016/j.jsps.2022.01.022

55.

Kumar G Patel D Odeh T Rojas E Sakhuja A Meersman M et al Incidence of venous thromboembolism and effect of anticoagulant dosing in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. J Hematol. (2021) 10(4):162–70. 10.14740/jh836

56.

Tsaplin S Schastlivtsev I Zhuravlev S Barinov V Lobastov K Caprini JA . The original and modified caprini score equally predicts venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. (2021) 9(6):1371–1381.4. 10.1016/j.jvsv.2021.02.018

Summary

Keywords

venous thromboembolism, COVID-19, thromboprophylaxis, anticoagulation, prevention and treatment

Citation

Chen X, Zhang S, Liu H, Zhang Q, Chen J, Zheng Q, Guo N, Cai Y, Luo Q, Xu Q, Yang S and Chen X (2024) Effect of anticoagulation on the incidence of venous thromboembolism, major bleeding, and mortality among hospitalized COVID-19 patients: an updated meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1381408. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1381408

Received

09 February 2024

Accepted

26 March 2024

Published

05 April 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Luca Spiezia, University of Padua, Italy

Reviewed by

Daniele Mengato, University Hospital of Padua, Italy

Francesco Poletto, University of Padua, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Chen, Zhang, Liu, Zhang, Chen, Zheng, Guo, Cai, Luo, Xu, Yang and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Qian Xu 674212726@qq.com Sheng Yang dryangxh2017@sina.com Xiangqi Chen drchxqtg@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.