Abstract

Reverse left ventricular (LV) remodeling after aortic valve replacement (AVR), in patients with aortic stenosis, is well-documented as an important prognostic factor. With this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to characterize the response of the unloaded LV after AVR. We searched on MEDLINE/PubMed and Web of Science for studies reporting echocardiographic findings before and at least 1 month after AVR for the treatment of aortic stenosis. In total, 1,836 studies were identified and 1,098 were screened for inclusion. The main factors of interest were structural and dynamic measures of the LV and aortic valve. We performed a random-effects meta-analysis to compute standardized mean differences (SMD) between follow-up and baseline values for each outcome. Twenty-seven studies met the eligibility criteria, yielding 11,751 patients. AVR resulted in reduced mean aortic gradient (SMD: mmHg, 95% CI: to , ), LV mass (SMD: g, 95% CI: to , ), end-diastolic LV diameter (SMD: mm, 95% CI: to , ), end-diastolic LV volume (SMD: ml, 95% CI: to 3.51, ), increased effective aortic valve area (SMD: 1.10 cm2, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.20, ), and LV ejection fraction (SMD: 2.35%, 95% CI: 1.31 to 3.40%, ). Our results characterize the extent to which reverse remodeling is expected to occur after AVR. Notably, in our study, reverse remodeling was documented as soon as 1 month after AVR.

1 Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common acquired valvopathy in the Western world (1). Its incidence increases with age, and its prevalence is expected to rise in the future (2).

AS is not an isolated valve disease but a more complex and broad pathology involving the myocardium. AS progression is associated with left ventricular (LV) remodeling, which is the myocardial response to increased afterload (2). Initially, LV remodeling is a compensatory response to a persistent obstacle to systolic ejection. The sustained increased pressure and hemodynamic load lead to the classical development of LV hypertrophy. This initial adaptation allows for a reduction in wall stress and maintenance of cardiac output. After this stage, persistent obstruction leads to maladaptive LV remodeling, causing gradual deterioration of diastolic and systolic functions (1). Clinically, this process can translate into various symptoms, including death due to heart failure or arrhythmic events (2). In other words, maladaptive LV response negatively impacts the prognosis of AS patients regarding survival and cardiovascular events (3).

The only effective treatment for severe AS is aortic valve replacement (AVR), which can be performed either surgically (SAVR) or percutaneously via transcatheter AV implantation (TAVI). AVR aims to eliminate the LV obstruction and ultimately revert this inadequate LV response (2). After AVR, the extension of the achieved reverse LV remodeling is a major determinant of symptoms and outcomes (2). Its prognostic importance has been reported in several randomized trials (2, 4, 5). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the gold standard method to characterize AS severity, LV remodeling, and LV reverse remodeling after AVR. These LV adaptations comprise several changes in echocardiographic parameters, such as LV mass, cavity dimensions and volumes, wall thicknesses, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (1). Unfortunately, data to predict LV response after AVR are lacking.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aim to assess the extent of left ventricular remodeling at pre-determined time points post-procedure in patients with aortic stenosis who underwent AVR. The measured variables of interest included effective aortic valve area (AVA), mean aortic gradient (MAG), left ventricular mass (LVM), LVEF, and end-diastolic left ventricular diameter (EDLVD) and volume (EDLVV).

2 Methods

2.1 Eligibility and search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement (6).

The literature search was conducted on 15 March 2022 in two electronic databases: MEDLINE (through PubMed) and Web of Science. The search was conducted with no restrictions on language or year of publication. Full details of the search are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| ISI Web of Knowledge | (TS (“ventricular mass”) OR TS (“LV mass”) OR TS (“septum thickness”) OR TS (“posterior wall thickness”) OR TS (“mass regression”) OR TS (“end diastolic diameter”) OR TS (“end systolic diameter”) OR TS (“end diastolic volume”) OR TS (“end systolic volume”) OR TS (“remodeling”) OR TS (“remodelling”) OR TS (“LVEDD”) OR TS (“LVESD”) |

| AND | |

| TS (“TAVI”) OR TS (“TAVR”) OR TS (“aortic valve replacement”) OR TS (“aortic valve implantation”) OR TS (“AVR”) OR TS (“prosthesis implantation”) | |

| AND | |

| TS (“patients”) OR TS (“patient”) OR TS (“subjects”)) | |

| NOT | |

| (TI (“aortic insufficiency”) OR TI (“aortic regurgitation”) OR TS (“magnetic resonance”) OR TS (“computed tomography”) | |

| OR | |

| DT (Editorial Material) OR DT (Review)) | |

| MEDLINE/PubMed | ((“TAVI”[Title/Abstract] OR “TAVR”[Title/Abstract] OR “aortic valve replacement”[Title/Abstract] OR “aortic valve implantation”[Title/Abstract] OR “AVR”[Title/Abstract] OR “prosthesis implantation”[Title/Abstract]) |

| AND | |

| (“ventricular mass”[Title/Abstract] OR “LV mass”[Title/Abstract] OR “septum thickness”[Title/Abstract] OR “posterior wall thickness”[Title/Abstract] OR “mass regression”[Title/Abstract] OR “end diastolic diameter”[Title/Abstract] OR “end systolic diameter”[Title/Abstract] OR “end diastolic volume”[Title/Abstract] OR “end systolic volume”[Title/Abstract] OR “remodeling”[Title/Abstract] OR “remodelling”[Title/Abstract] OR “LVEDD”[Title/Abstract] OR “LVESD”[Title/Abstract]) | |

| AND | |

| (“patients”[Title/Abstract] OR “patient”[Title/Abstract] OR “subjects”[Title/Abstract])) | |

| NOT | |

| (“editorial”[Publication Type] OR “review”[Publication Type] OR “systematic review”[Publication Type] OR “Case Reports”[Publication Type] OR “aortic insufficiency”[Title] OR “aortic regurgitation”[Title] OR “magnetic resonance”[Title/Abstract] OR “computed tomography”[Title/Abstract]) |

Keywords used to perform the query in the two databases used in this study (date of search: 15 March 2022).

Studies were included if they reported echocardiographic findings before and at least 1 month after SAVR or TAVI for the treatment of AS. This time interval was chosen to allow acute changes after the procedure to resolve and for reverse remodeling to occur (7). Furthermore, patient evaluation had to be performed at pre-determined time points post-procedure, i.e., at either 1, 3, 6, or 12 months.

Studies also needed to report at least one outcome variable of interest for the measurement of the left ventricle reverse remodeling to be included, namely, left ventricular dimensions or ejection fraction.

We excluded all non-human studies, case–control studies, case reports, and reviews. Studies without a predefined follow-up period and with fewer than 100 patients were also excluded.

2.2 Study selection, data collection process, and study outcomes

Two investigators (FSN and CAM) independently reviewed each study by title and abstract and then by full-text reading. Discordant decisions were managed by consensus. Authors of primary studies were contacted for clarification if relevant data were missing. For each primary study, two investigators (FSN and CAM) independently performed data extraction. We extracted the following information: study design (clinical setting, duration of follow-up, and number of patients included), Baseline characteristics of the population (Table 2) [eligibility criteria; age; gender; New York Heart Association (NYHA) class; body surface area (BSA); and frequency of hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease, and other comorbidities], intervention (details on SAVR or TAVI procedures), and outcome data of interest. The latter included effective AVA, MAG, EDLVD, EDLVV, LVM, and LVEF.

Table 2

| Cohort (if applicable) | Female sex (%) | Agea (years) | NYHA III/IV (%) | HTN (%) | Diabetes (%) | CAD (%) | BSA (m2)b | Initial LVEF (Y/N) | Follow-up (months) | Evaluation dates | Valve | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campos et al. (8) | 47.6 | 70.9 7.5 | 60.9 | NR | NR | 22.4 | NR | NR | 6 | 1993–2004 | Biological | |

| Gegenava et al. (9) | 50 | 80 7 | 57 | 76 | 26 | 60 | NR | NR | 12 | NR | Biological | |

| Ngo et al. (10) | 43.3 | 79 5 | 50.4 | 72 | 17.6 | 4.2 | 1.9 (0.2) | NR | 3 and 12 | 2009–2014 | Biological | |

| Gelsomino et al. (11) | 50.4 | 71.3 6.4 | 93.6 | NR | NR | 30.4 | 1.7 (0.1) | NR | 6 and 12 | 1993–2000 | Biological | |

| Vizzardi et al. (12) | 48 | 83 7 | 55 | 68 | 47 | 25 | 1.7 (0.17) | NR | 6 | NR | Biological | |

| Pibarot et al. (13) | TAVI | 32.5 | 73.3 5.8 | 31.3 | 85 | 31.3 | 27.7 | 2 (0.2) | NR | 1 and 12 | 2016–2017 | Biological |

| SAVR | 28.9 | 73.6 6.1 | 23.8 | 85.9 | 30.2 | 28 | 2 (0.2) | NR | 1 and 12 | 2016–2017 | Biological | |

| Izumi et al. (14) | 53 | 70 9 | 19 | 43 | 17 | 11 | 1.52 (0.17) | NR | 12 | 2000–2006 | Both | |

| Harrington et al. (15) | 45.6 | 81 9 | NR | 91 | 28 | 64 | 1.9 (0.3) | NR | 12 | 2011–2017 | Biological | |

| Merdler et al. (16) | 54.5 | 82 6.1 | 85.6 | 86.1 | 37.7 | 50.1 | NR | NR | 12 | 2009–2018 | Biological | |

| Martinovic et al. (17) | 57 | 72.8 3 | 81 | 65 | 22 | 45 | NR | NR | 12 | 1996–2004 | Biological | |

| Al-Rashid et al. (18) | 52.3 | 82 4 | 91.3 | 85.3 | 31.3 | NR | NR | NR | 3 | 2016–2017 | Biological | |

| Thomson (19) | 46.5 | 74 6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 | 1992–1997 | Biological | |

| Ewe et al. (20) | 60.7 | 81.1 6.2 | 83 | 75.5 | 17 | NR | 1.73 (0.18) | NR | 6 | NR | Biological | |

| Douglas et al. (21) | 55.2 | 83.2 8.9 | NR | 86.6 | 31.5 | 69.9 | NR | NR | 1 | 2007–2010 | Biological | |

| Ledwoch et al. (22) | 39 | 79 8 | 63 | 90 | 22 | 68 | NR | NR | 12 | 2015–2020 | Biological | |

| Al-Hijji et al. (23) | 47.8 | 82.5 7.7 | 86.1 | 88.7 | 38.3 | NR | NR | NR | 1 | 2012–2016 | Biological | |

| Weber et al. (24) | 37 | NR | 54 | 81 | 26 | 45 | NR | NR | 3 | 2015–2016 | Biological | |

| Fuster et al. (25) | 36.2 | 63 9 | 70 | 39.5 | 16.2 | NR | 1.7 (0.2) | NR | 1 | 1994–2001 | Both | |

| Theron et al. (26) | 31.3 | 76.8 6.2 | 35.3 | 99.3 | 27.3 | NR | NR | NR | 1 and 12 | 2012–2015 | Biological | |

| Chau et al. (27) | 53 | 84 7 | NR | 94 | 36 | 77 | 1.81 (0.24) | NR | 1 and 12 | 2007–2020 | Biological | |

| Ochiai et al. (28) | RAS | 70.1 | 84.2 5 | 46.6 | 83.8 | 27.8 | 41.5 | 1.44 (0.16) | NR | 6 | 2013–2016 | Biological |

| No RAS | 75.7 | 84.8 5 | 54.5 | 61.4 | 24.3 | 33.9 | 1.39 (0.17) | NR | 6 | 2013–2016 | Biological | |

| Little et al. (29) | TAVI | 47 | 83.2 7.1 | 85.7 | NR | NR | 75.3 | 1.8 (0.2) | NR | 12 | 2010–2014 | Biological |

| SAVR | 48.2 | 83.3 6.4 | 87 | NR | NR | 75.6 | 1.9 (0.2) | NR | 12 | 2010–2014 | Biological | |

| Ninomiya et al. (30) | 58 | 83.2 5 | NR | NR | 43 | 40 | 1.5 (0.2) | NR | 3 | 2013–2018 | Biological | |

| Iliopoulos et al. (31) | 50 | 75.8 5.1 | 25.7 | 93 | 35.9 | 64.8 | 1.7 (0.2) | NR | 3, 6 and 12 | 2006–2010 | Biological | |

| Beholz et al. (32) | 55 | 76.5 6.4 | 63 | 73 | 24 | NR | NR | NR | 1 and 12 | 2004–2006 | Biological | |

| Fischlein et al. (33) | 64.4 | 78.3 5.6 | 63.7 | 83.7 | 29 | NR | 1.8 (0.2) | NR | 12 | 2010–2013 | Biological | |

| Medvedofsky et al. (34) | 100 | 83 8 | 84 | 94 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 2007–2014 | Biological |

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

BSA, body surface area; CAD, coronary artery disease; HTN, hypertension; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association (NYHA) Classification; NR, not reported; RAS, renin angiotensin system therapy; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

amean standard deviation (SD).

bmedian (interquartile range).

2.3 Risk of bias assessment

We used the Study Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort Studies from the National Institutes of Health to categorize several domains for all the eligible studies. The overall risk of bias was independently assigned to each study by two investigators (FSN, CAM) and classified into “good,” “fair,” and “poor”, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3

| Criteria | Campos et al. (8) | Gegenava et al. (9) | Ngo et al. (10) | Gelsomino et al. (11) | Vizzardi et al. (12) | Pibarot et al. (13) | Izumi et al. (14) | Harrington et al. (15) | Merdler et al. (16) | Martinovic et al. (17) | Al-Rashid et al. (18) | Thomson (19) | Ewe et al. (20) | Douglas et al. (21) | Ledwoch et al. (22) | Al-Hijji et al. (23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | NA | NA | NR | NA | NA | NR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NR | NA | NA |

| 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | NR | No | No |

| 6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NR | NR | Yes | NR | Yes | NR | Yes | NR |

| 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Overall risk of bias | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Criteria | Weber et al. (24) | Fuster et al. (25) | Theron et al. (26) | Chau et al. (27) | Ochiai et al. (28) | Little et al. (29) | Ninomiya et al. (30) | Iliopoulos et al. (31) | Beholz et al. (32) | Fischlein et al. (33) | Medvedofsky et al. (34) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | NA | NA | NA | NR | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | No |

| 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? | No | No | No | NR | NR | NR | No | No | No | No | No |

| 6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | Yes | No | Yes | NR | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Overall risk of bias | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

Risk of bias assessment of the included studies.

NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

2.4 Statistical analysis

We performed a random-effects meta-analysis using the restricted maximum likelihood approach to compute pooled mean differences (MD) or standardized mean differences (SMD) between post-follow-up and baseline values for each outcome. Heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochran Q statistic -value and the statistic: a -value <0.10 and an >50% were considered to represent substantial heterogeneity. Sources of heterogeneity were explored using univariable meta-regression models, with tested covariates including the publication year, mean age of the participants, percentage of females, average BSA, percentage of patients in NYHA classes III/IV, and percentage of patients with other comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. In addition, we performed subgroup analyses for the follow-up period and the initial LVEF (classes were categorized into two groups: lower than 50% and higher than 50%). All statistical analyses were performed using the meta package of R software (35, 36).

3 Results

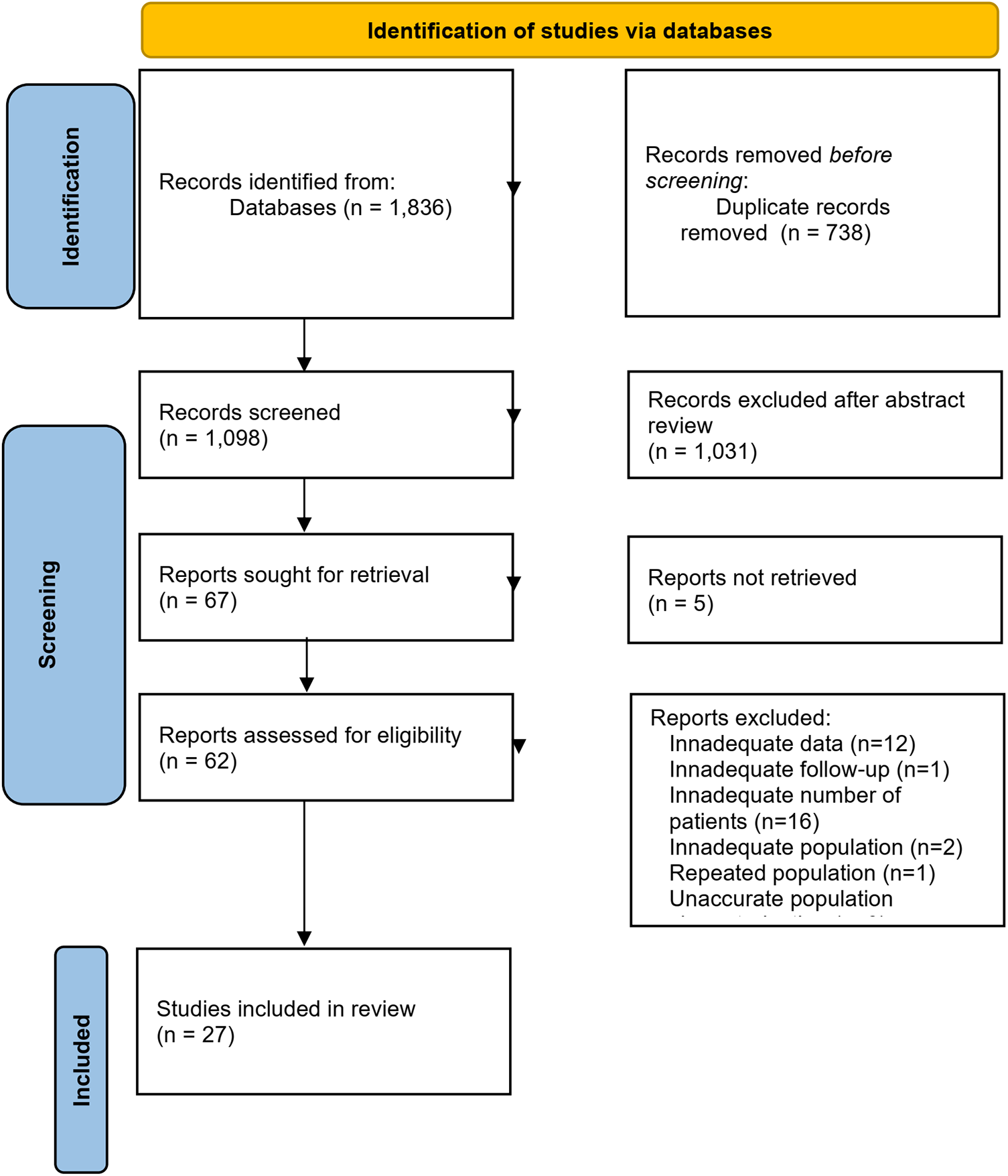

In total, 1,836 publications were identified through our search of MEDLINE/PubMed (944 records) and Web of Science (892 records) databases. After removing the duplicates, 1,098 records remained. Following the title and abstract screening, we selected 67 articles for full-text review. After excluding articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, we ended up with 27 primary studies (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram and Table 4 for a summary table of the included studies) (8–34).

Figure 1

Flowchart for the study selection process. From: (37).

Table 4

| Number of patients | Key inclusion criteria | Key exclusion criteria | Procedure | Outcomes | Type of study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campos et al. (8) | 188 | Receiving a Cryolife O’Brien prosthesis (stentless bioprosthesis) in the aortic position. | Sinotubular dilation; extensive calcification of the aortic root; unfavorable position of coronary ostia. | SAVR | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVM, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Gegenava et al. (9) | 210 | Severe AS. | Absence of non-contrast-enhanced CT of the aortic valve; lack of complete echocardiographic follow-up. | TAVI | AVA, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF | Single-center, RCT |

| Ngo et al. (10) | 113 | Symptomatic severe AS or left ventricular hypertrophy, decreased LVEF, or atrial fibrillation; >70 years. | Isolated AR; other significant valve diseases requiring intervention; CAD requiring revascularization; previous open-heart surgery; AMI or PCI within the last year; stroke or TIA within the last 30 days; renal insufficiency requiring hemodialysis; pulmonary insufficiency; active infectious disease requiring antibiotics; emergency intervention; unstable pre-interventional condition requiring inotropic support or mechanical heart assistance. | TAVI | AVA, AVAI, LVM, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, EDLVV, ESLVV, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, retrospective cohort |

| Gelsomino et al. (11) | 119 | AVR with a CLOB stentless valve. | Contraindications for stentless valve implantation: extensive calcification of the sinus aortic wall and root; annulus diameter more than 30 mm that precluded the use of a 29-mm valve; extremely thin aortic wall. | SAVR | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Vizzardi et al. (12) | 135 | Symptomatic critical AS, with or without AR; age years; logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation score ; age years and one or more of the following: cirrhosis (Child class A or B), pulmonary insufficiency, pulmonary hypertension, previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery or valvular surgery, porcelain aorta, recurrent pulmonary emboli, right ventricular insufficiency, contraindication to open-chest surgery, cachexia (BMI kg/m2). | AMI in the preceding 30 days; PCI days before implantation or scheduled during or within 30 days after TAVI; uncontrolled atrial fibrillation; history of AVR; stroke within the previous month; symptomatic carotid or vertebral artery disease ( stenosis); abdominal aortic aneurysm; bleeding diathesis or coagulopathy; eGFR ml/m; life expectancy <1 year. | TAVI | AVAI, MAG, LVM, LVMI, EDLVV, ESLVV, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Pibarot et al. (13) | 948 | Severe AS and NYHA Functional Class 2, limited exercise capacity, abnormal BP response, or arrhythmia; severe AS with LVEF %; Heart Team agreement of a low operative mortality risk and an STS . | Anatomical contraindications for TAVI; AMI month; unicuspid, bicuspid, or non-calcified aortic valve; severe AR; severe MR; moderate MS; pre-existing mechanical or bioprosthetic valve in any position; complex CAD; unprotected left main coronary artery; syntax score (in the absence of prior revascularization); symptomatic carotid or vertebral artery disease or successful treatment of carotid stenosis within 30,days of randomization; leukopenia (WBC cells/ml); anemia (Hgb g/dl); thrombocytopenia (Plt cells/ml); history of bleeding diathesis, coagulopathy, or hypercoagulable state; hemodynamic or respiratory instability requiring inotropic support, mechanical ventilation or mechanical heart assistance within 30 days of randomization; HCM with obstruction; LVEF ; intracardiac mass, thrombus or vegetation; stroke or TIA within 90 days of randomization; renal insufficiency (eGFR ml/min) and/or renal replacement therapy at the time of screening; active bacterial endocarditis within 180 days of randomization; severe lung disease or currently on home oxygen; severe pulmonary hypertension; cirrhosis or any active liver disease; significant frailty as determined by the Heart Team; BMI kg/m2; estimated life expectancy <24 months. | SAVR TAVI | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF | Multi-center, RCT |

| Izumi et al. (14) | 269 | AVR for chronic aortic valve disease. | Concomitant mitral valve replacement; acute AR due to aortic dissection or infective endocarditis. | SAVR | LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF | Multi-center, retrospective registry |

| Harrington et al. (15) | 156 | Severe AS submitted to TAVI; echocardiogram at least 1 day prior to TAVI and up to 1-year after the procedure. | NR | TAVI | MAG, LVM, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, EDLVV, ESLVV, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, retrospective cohort |

| Merdler et al. (16) | 224 | TAVI for symptomatic severe AS with intermediate or high-risk for surgery. | AR or MR; patients with missing data. | TAVI | EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF | Single-center, retrospective cohort |

| Martinovic et al. (17) | 189 | AVR with the CryoLife-O’Brien model 300 (stentless aortic porcine bioprosthesis). | Excessive calcification of the aortic root; aortic root aneurysm. | SAVR | AVA, MAG, LVMI | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Al-Rashid et al. (18) | 145 | Severe symptomatic AS submitted to transfemoral TAVI; STS score or considered excessive surgical risk due to comorbidities and other risk factors not reflected by the STS score. | Patients treated with a TAVI for the management of mitral valve pathology; pure non-calcific AR; previous or concomitant replacement of another valve; insufficient acoustic window preventing a complete echocardiographic study; hemodynamic instability. | TAVI | AVA, MAG, LVMI, EDLVV, ESLVV, LVEF | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Thomson (19) | 142 | >59 years; predominant AS; AVR between December 1992 and February 1997 with either the CLOB or C-E xenografts or the ATS mechanical prosthesis. | Concomitant myomyectomy. | SAVR | AVA, LVM | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Ewe et al. (20) | 135 | Symptomatic severe AS with high operative risk or the presence of contraindications to conventional aortic valve surgery. | Previous aortic or mitral prostheses; unsuccessful TAVI; echocardiographic follow-up months. | TAVI | AVAI, MAG, LVMI, LVEF | Multi-center, prospective cohort |

| Douglas et al. (21) | 143 | Severe symptomatic AS. | AMI month; unicuspid, bicuspid, or non-calcified aortic valve; mixed aortic valve disease; any therapeutic invasive cardiac procedure performed within 3 days of the index procedure; pre-existing prosthetic valve in any position; prosthetic ring; severe mitral annular calcification; severe MR; blood dyscrasias: leukopenia (WBC mm3), acute anemia (Hgb mg/dl), thrombocytopenia (platelet count cells/mm3), history of bleeding diathesis or coagulopathy; untreated CAD requiring revascularization; hemodynamic instability requiring inotropic therapy or mechanical hemodynamic support devices; need for emergency surgery; HCM; LVEF ; intracardiac mass, thrombus or vegetation; active peptic ulcer or upper GI bleeding within the prior 3 months; recent stroke or TIA; renal insufficiency (creatinine mg/dl) and/or ESRD requiring chronic dialysis; life expectancy <12 months; active bacterial endocarditis or other active infections; bulky calcified aortic valve leaflets in close proximity to coronary ostia; anatomical contraindications for TAVI. | TAVI | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVM, LVMI, EDLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Multi-center, RCT |

| Ledwoch et al. (22) | 118 | Severe symptomatic AS. | 1-year follow-up not reached; death; no transthoracic echocardiogram at follow-up. | TAVI | AVA, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Al-Hijji et al. (23) | 101 | Balloon-expandable TAVI using a Sapien valve. | Self-expanding CoreValve patients excluded from the transfemoral arm. | TAVI | AVAI, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, LVEF | Single-center, retrospective cohort |

| Weber et al. (24) | 149 | Moderate to severe AS. | Relevant disease of other valves; AMI (<30 days); peripheral artery disease (>Fontaine stage IIb); LVEF < ; thrombotic embolism (<6 months); autoimmune disorders; renal failure (liable to dialysis); previous cardiac surgery; AR and dilatation of the ascending aorta receiving additional aortic surgery; TAVI or no surgical AVR decision. | SAVR | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVM, LVMI, EDLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Fuster et al. (25) | 204 | Pure or predominant AS. | Significant AR; coronary artery bypass surgery and other valve or aortic surgical procedures; emergent operations; infectious endocarditis; absence of preoperative echocardiography; previous AVR. | SAVR | AVA, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, retrospective cohort |

| Theron et al. (26) | 149 | Severe AS. | NA | SAVR | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVM, EDLVV, ESLVV, LVEF, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Chau et al. (27) | 1434 | Symptomatic severe AS. | Exclusion criteria of the PARTNER 1A, 2A, and S3 trials and registries; missing LVMi data at 1 year. | TAVI | AVAI, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Multi-center, RCT, registries |

| Ochiai et al. (28) | 560 | Symptomatic severe AS. | Death within 6 months of the procedure; lack of data from the 6-month follow-up; only one prescription of ACE inhibitors or ARBs during the follow-up (cross-over). | TAVI | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVMI, EDLVV, ESLVV, LVEF | Multi-center, prospective cohort |

| Little et al. (29) | 742 | Symptomatic severe AS with increased risk for SAVR. | AMI 30 days; PCI or peripheral intervention performed within 30 days prior to the procedure; blood dyscrasias; CAD requiring revascularization; cardiogenic shock; need for emergency surgery; LVEF ; recent cerebrovascular accident or TIA; ESRD requiring chronic dialysis; eGFR ml/min; GI bleeding within the last 3 months; ongoing sepsis; life expectancy <1 year; symptomatic carotid or vertebral artery disease; known hypersensitivity or contraindication to some drugs; participation in other trials; native aortic annulus size >29/<18 mm; pre-existing prosthetic valve in any position; bicuspid or unicuspid valve; mixed aortic valve disease; moderate to severe MR or tricuspid regurgitation; moderate to severe MS; obstructive HCM; intracardiac mass, thrombus or vegetation; severe basal septal hypertrophy with outflow gradient; specific anatomical contraindications. | TAVI and SAVR | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVM, LVMI, EDLVV, ESLVV, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Multi-center, RCT |

| Ninomiya et al. (30) | 100 | Severe AS. | Death within 3 months after TAVI of causes unrelated to the procedure; absence of the 3-month follow-up echocardiogram. | TAVI | AVAI, MAG, LVMI, EDLVD, ESLVD, EDLVVI, ESLVVI, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Iliopoulos et al. (31) | 121 | AS or AR or mixed lesions (6.3% of patients with severe AR; 39.8% with mixed pathology). | Annuloaortic ectasia. | SAVR | MAG, EDLVD, ESLVD, IVST | Single-center, prospective cohort |

| Beholz et al. (32) | 194 | SAVR of the affected native or prosthetic aortic valve (6% for AR; 22% for AS AR). | eGFR ml/min; disorder of calcium metabolism; collagen autoimmune disease; active endocarditis; bicuspid aortic valve; coronary ostia and sinuses of Valsalva asymmetry; participation in other studies; additional valve replacement; previously implanted prosthetic valve other than aortic, which is to be replaced; intravenous drug abuse; HIV-positive; life expectancy <3 years; HCM. | SAVR | AVA, AVAI, MAG, LVM, EDLVD, ESLVD, LVEF, PWT, IVST | Multi-center, prospective cohort |

| Fischlein et al. (33) | 137 | AS or AS AR (34.3%); age years. | Participation in other studies; previously implanted Perceval prosthesis requiring replacement; previous implantation of valve prostheses or annuloplasty ring not being replaced by the study valve; need of simultaneous cardiac procedures (except septal myectomy, coronary artery bypass grafting, or both); need for multiple valve replacement or repair that would be replaced with a non-Perceval valve or repaired; ascending aorta dissection or aneurysm; non-elective intervention; active endocarditis or myocarditis; bicuspid aortic valve; aortic root enlargement; AMI within 90 days before the planned surgery; hypersensitivity to nickel alloys; life expectancy <1 year; unacceptably high surgical risk; renal dialysis; chronic renal failure with hyperparathyroidism; acute preoperative neurological deficit; AMI or cardiac event that has not returned to baseline or stabilized at least 30 days before the valve surgery. | SAVR | AVA, MAG, LVMI | Multi-center, prospective cohort |

| Medvedofsky et al. (34) | 123 | Severe symptomatic AS. | Presence of a pacemaker; poor-quality image; atrial fibrillation. | TAVI | EDLVVI, ESLVVI, LVEF | Multi-center, prospective cohort |

General characteristics of the included studies.

ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AR, aortic regurgitation; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AS, aortic stenosis; AVA, aortic valve area; AVAI, aortic valve area index; AVR, aortic valve replacement; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; CT, computed tomography; EDLVD, end-diastolic left ventricular diameter; EDLVVI, end-diastolic left ventricular volume index; EDLVV, end-diastolic left ventricular volume; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESLVD, end-systolic left ventricular diameter; ESLVVI, end-systolic left ventricular volume index; ESLVV, end-systolic left ventricular volume; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GI, gastrointestinal; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; Hgb, hemoglobin; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; LVM, left ventricular mass; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MAG, mean aortic gradient; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; NR, not reported; NYHA, New York Heart Association (NYHA) Classification; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Plt, platelet; PWT, posterior wall thickness; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; STS Score, Society of Thoracic Surgery Score; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; WBC, white blood cell.

Since some studies contained more than one distinct population, the search yielded 39 independent patient cohorts. The studies were published between 1998 and 2020, assessing 11,751 patients who completed echocardiographic assessment before and at least 1 month post-AVR.

3.1 Effective aortic valve area and mean aortic gradient

While this work is related to left ventricular remodeling after AVR, we chose to start by reporting measures related to AVR, such as aortic valve area and gradient. This ensures that the studies assessed comparable conditions and demonstrated similar improvements after valve obstruction is resolved. By doing so, we aimed to establish a consistent baseline for analyzing left ventricular remodeling parameters.

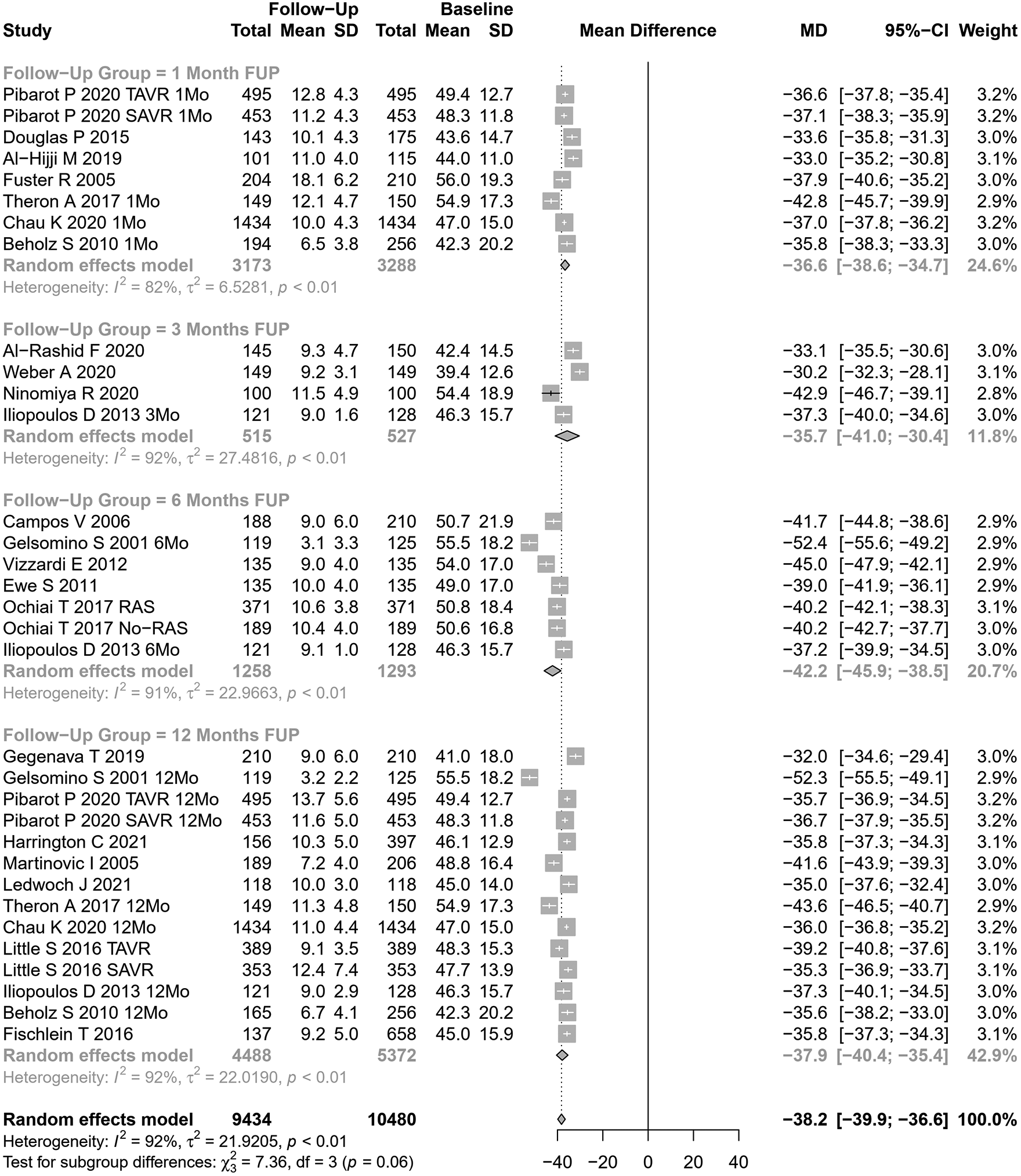

Our meta-analytical results indicate that, after AVR, there was an increase in the effective aortic valve area and a decrease in the mean aortic gradient. Based on 26 cohorts ( at baseline, Figure 2), the pooled SMD for effective aortic valve area was 1.10 cm2 (95% CI: 1.01–1.20, , , Cochran’s Q -value ), corresponding to a significant increase after AVR, albeit with substantial heterogeneity.Univariate meta-regression identified publication year, age, hypertension, NYHA class III or IV, DM, type of AVR, and EF >50% as potential moderators of heterogeneity (see Supplementary Table S1 for subgroup and heterogeneity analysis and Supplementary Table S2 for meta-regression).

Figure 2

SMD post-AVR vs. pre-AVR for the aortic valve area.

In studies assessing SAVR (15 cohorts), AVA increased by 1.19 cm2 (95% CI: 1.05– 1.33), while in TAVI patients (11 cohorts), AVA increased by 0.99 cm2 (95% CI: 0.91– 1.06). The results were significantly different between SAVR and TAVI patients (). No significant differences were observed when our results were stratified according to the follow-up period (Figure 2).

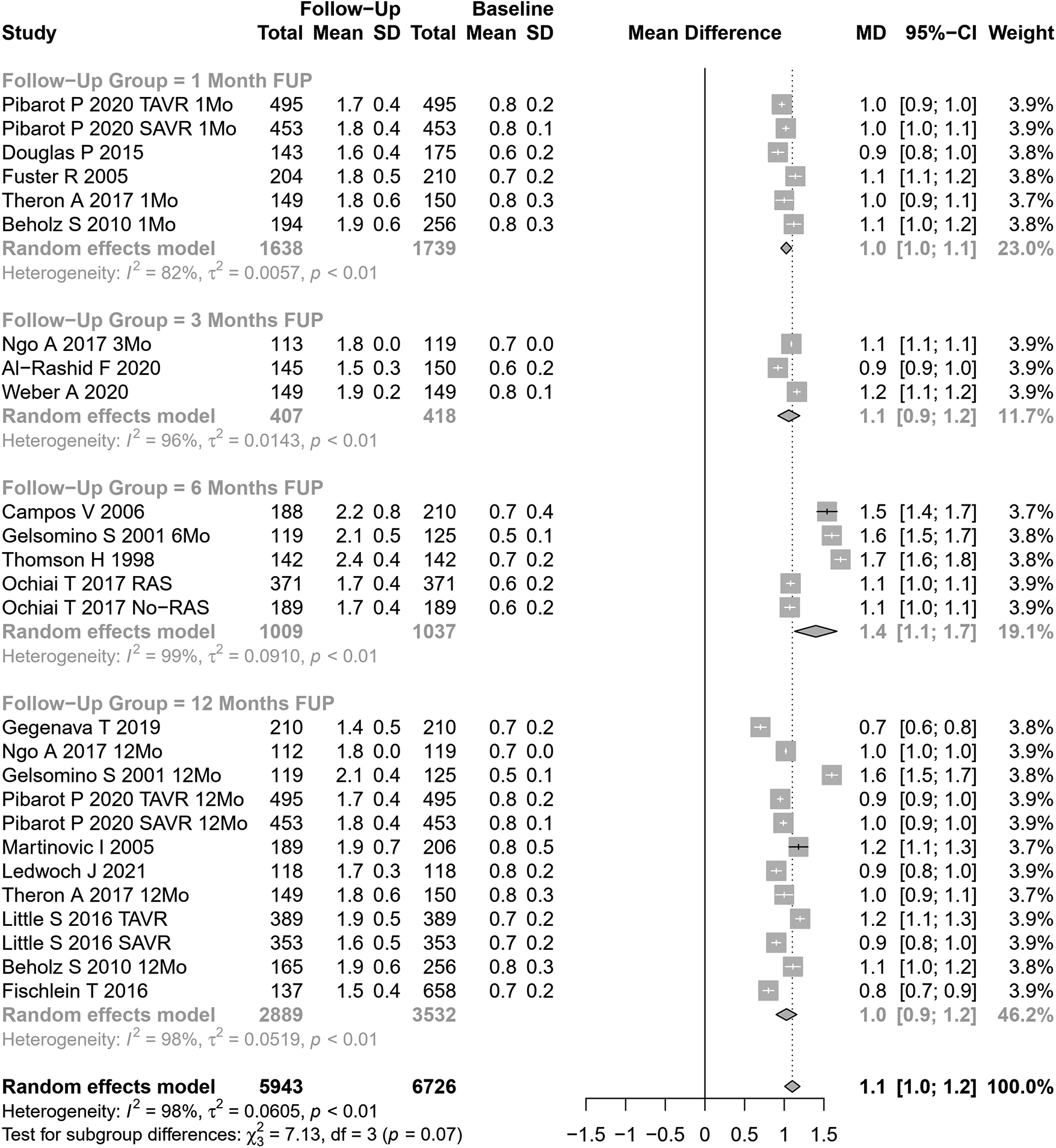

The mean aortic gradient was assessed in 33 cohorts ( patients at baseline, Figure 3). The pooled SMD for mean aortic gradient was mmHg (95% CI: to mmHg, , , Cochran’s Q -value ), indicating a significant decrease after AVR, but with substantial heterogeneity. Univariate meta-regression identified publication year and coronary artery disease as potential moderators of heterogeneity (see Supplementary Table S1 for subgroup and heterogeneity analysis and Supplementary Table S2 for meta-regression). Subgroup analyses showed a trend for differences according to follow-up periods (; Figure 3) but not according to the type of AVR ().

Figure 3

SMD post-SAVR vs. pre-SAVR for MAG.

3.2 Parameters on left ventricular reverse remodeling

3.2.1 Left ventricular mass

LVM change after AVR was analyzed in 14 cohorts (Figure 4). The pooled SMD for LVM was g (95% CI: to , ; , Cochran’s Q -value ), indicating a significant decrease after AVR, albeit with substantial heterogeneity.

Figure 4

SMD post-AVR vs. pre-AVR for LVM.

Performing subgroup analysis according to follow-up periods, significant differences were observed (). However, the values involved were relatively small (and may represent different samples evaluated at various time points and not a cohort evaluated prospectively through time): LVM reduction of 27 g at 1 month, 16 g at 3 months, 70 g at 6 months, and 34 g at 12 months. Performing subgroup analysis according to the type of AVR, no significant differences were observed ().

Univariate meta-regression identified publication year and DM as potential moderators of heterogeneity (see Supplementary Table S1 for subgroup and heterogeneity analysis and Supplementary Table S2 for meta-regression).

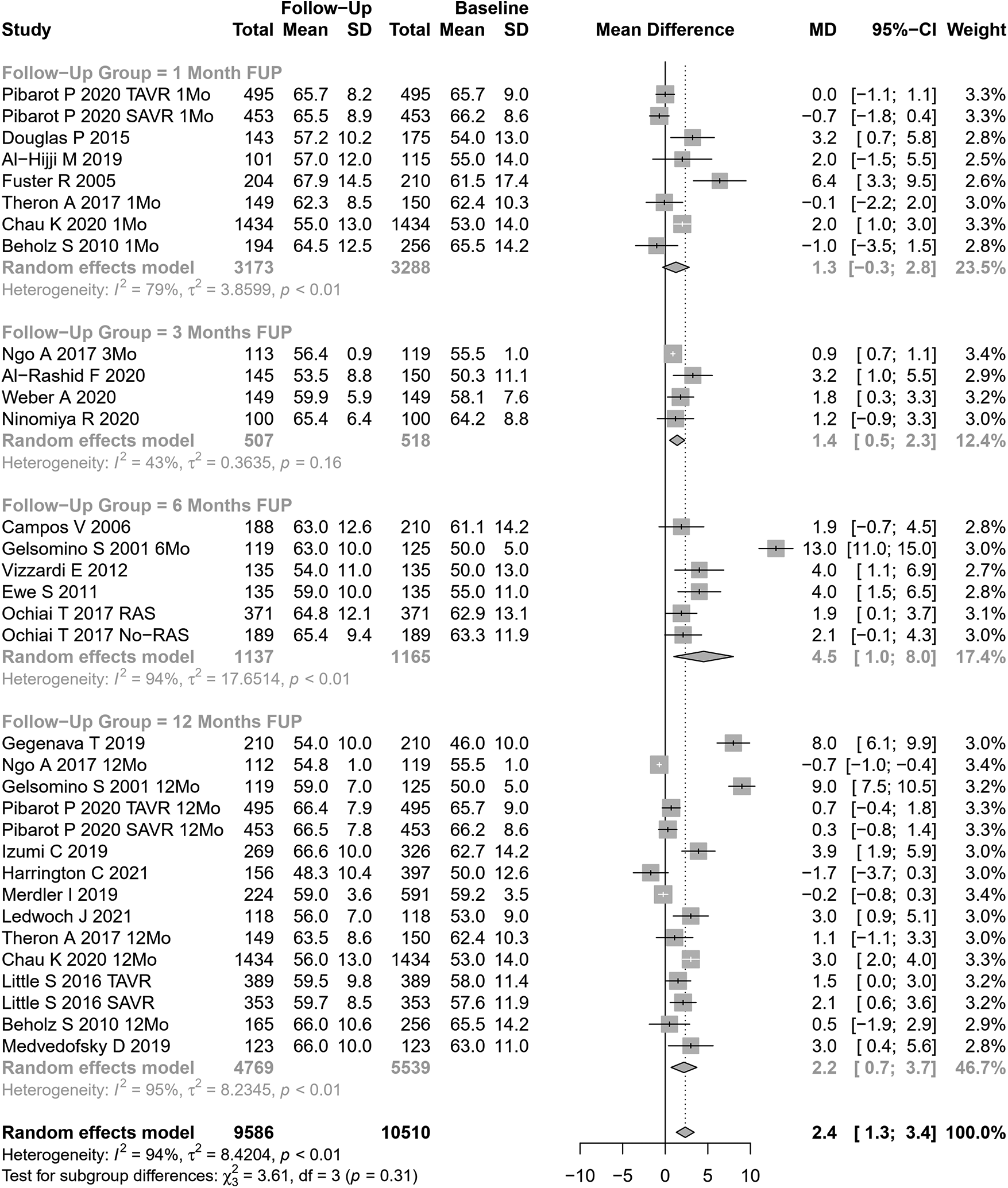

3.2.2 Left ventricular ejection fraction

LVEF change after AVR was assessed in 33 cohorts ( participants at baseline, Figure 5). The pooled SMD for LVEF was 2.35% (95% CI: 1.31%–3.40%, ; , Cochran’s Q -value ), indicating a significant increase after AVR, although with substantial heterogeneity. Performing subgroup analysis according to follow-up periods or the type of AVR, no significant differences were observed ( and , respectively).

Figure 5

SMD post-AVR vs. pre-AVR for LVEF.

Univariate meta-regression identified publication year and NYHA classification III or IV as potential moderators of heterogeneity (Supplementary Table S1 for subgroup and heterogeneity analysis and Supplementary Table S2 for meta-regression).

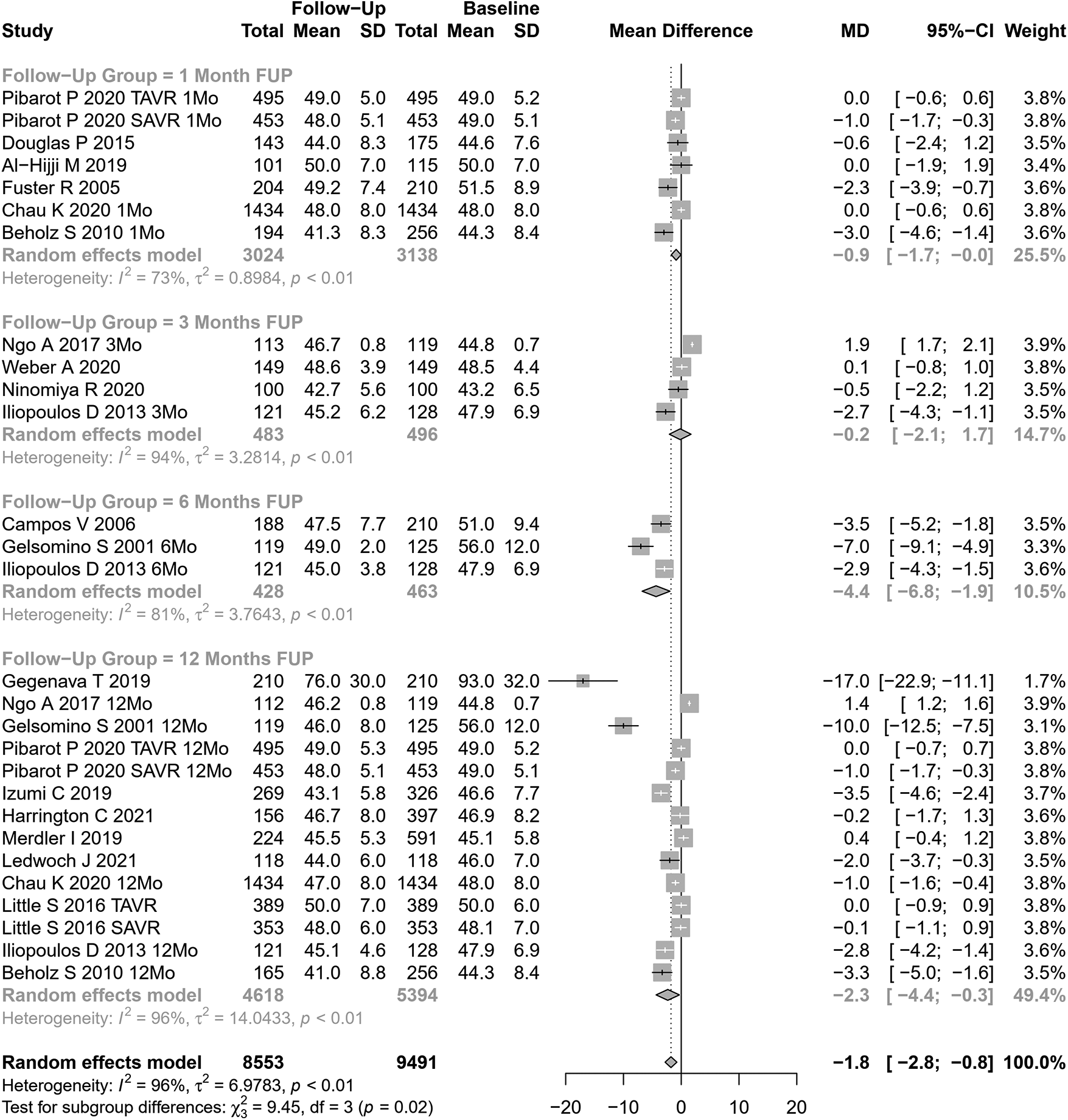

3.2.3 End-diastolic left ventricular diameter and volume

EDLVD change after AVR was assessed in 28 cohorts ( participants at baseline, Figure 6). The pooled SMD for EDLVD was mm (95% CI: to , ; , Cochran’s Q -value ), indicating a significant decrease after AVR, although with substantial heterogeneity.

Figure 6

SMD post-AVR vs. pre-AVR for EDLVD.

Stratifying our results according to follow-up periods, significant differences were observed (). However, the values involved were relatively small (and may represent different samples evaluated at various time points, rather than a cohort evaluated prospectively through time): EDLVD decreased by 0.88 mm at 1 month, 0.18 mm at 3 months, 6.77 mm at 6 months, and 2.33 mm at 12 months.

Significant differences were also observed in performing subgroup analysis according to the type of AVR (). In studies assessing SAVR (14 cohorts), EDLVD decreased by 2.92 mm (95% CI: to ) vs 0.16 mm in TAVI patients (14 cohorts; 95% CI: to ). Univariable meta-regression identified publication year, age, and coronary artery disease as potential moderators of heterogeneity (see Supplementary Table S1 for subgroup and heterogeneity analysis and Supplementary Table S2 for meta-regression).

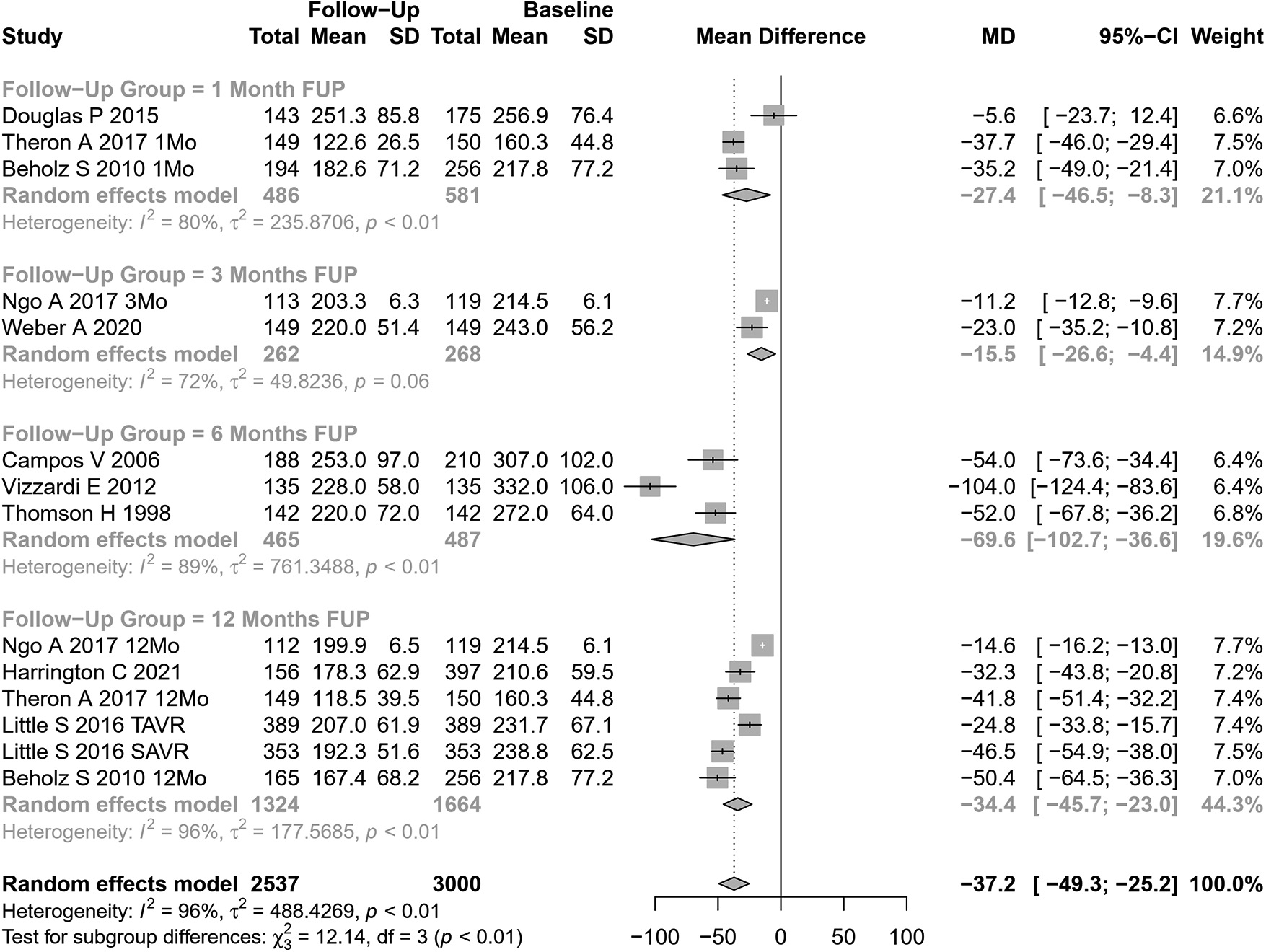

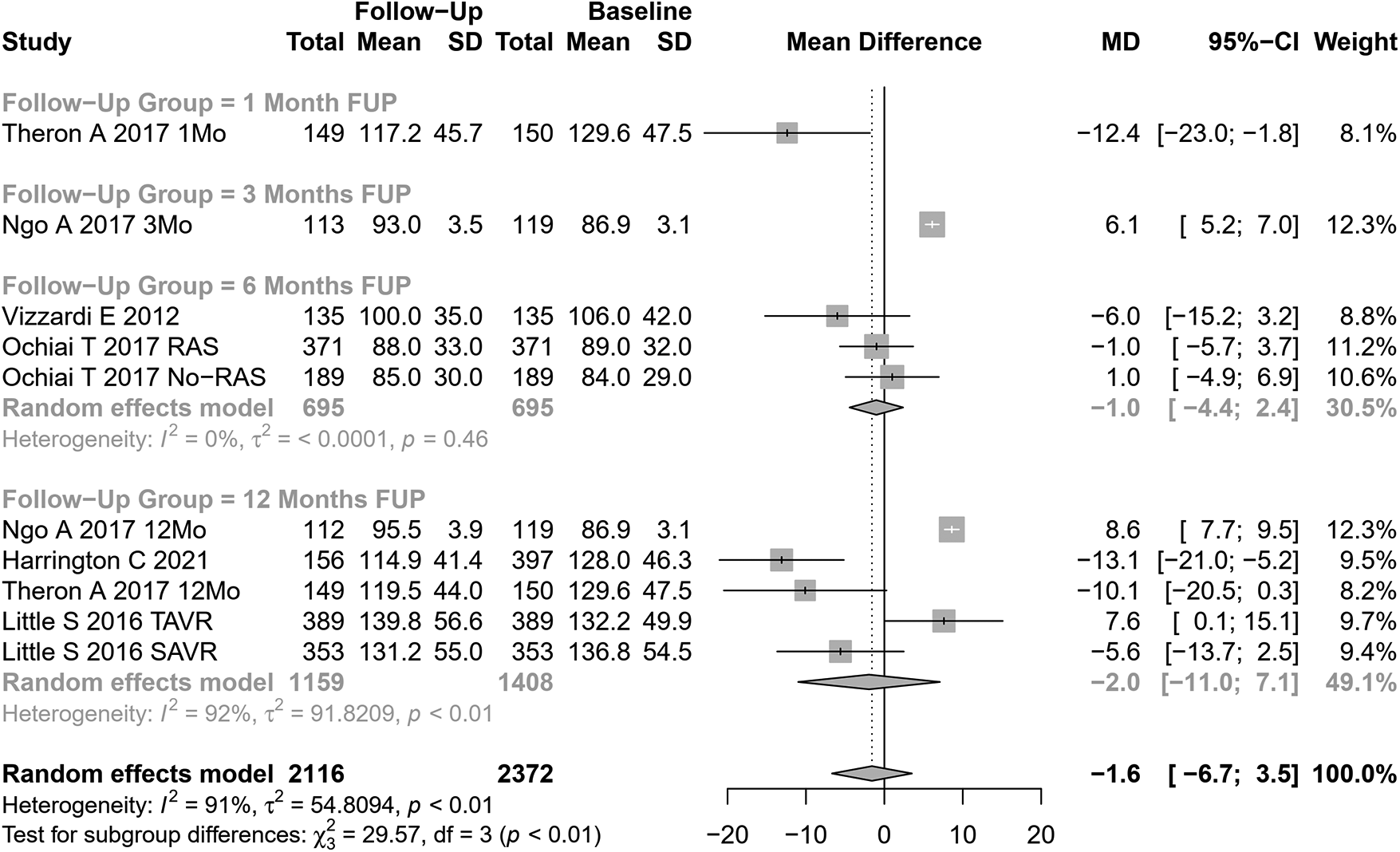

EDLVV change after AVR was assessed in 10 cohorts ( participants at baseline, Figure 7). The pooled SMD for EDLVV was ml (95% CI: to 3.51, ; , Cochran’s Q -value ), indicating a non-significant decrease after AVR.

Figure 7

SMD post-SAVR vs. pre-SAVR for EDLVV.

Univariate meta-regression identified the type of AVR, coronary artery disease, and hypertension as potential moderators of heterogeneity (see Supplementary Table S1 for subgroup and heterogeneity analysis and Supplementary Table S2 for meta-regression).

4 Discussion

In this study, we assessed the echocardiographic parameters of the unloaded LV after AVR. Notably, LV reverse remodeling was evident at the earliest time point evaluated (1 month after AVR). Several of the evaluated parameters were consistent with reverse remodeling, namely, the significant reduction observed in LVM and EDLVD, and LVEF improvement. A trend for EDLVV reduction was also observed. Our results are consistent with those from Mehdipoor et al. (38), who reported indexed LVM reduction and increased LVEF within 6–15 months after TAVI on 10 primary studies involving 305 patients.

Patient follow-up after AVR typically focusses on monitoring valve hemodynamics over time, specifically the evolution of the effective aortic valve area, gradient, and left ventricular function. Reverse left ventricular remodeling is not commonly assessed in routine clinical practice post-AVR. This is partly due to the lack of established norms for what constitutes “normal” left ventricular remodeling after AVR. This study aimed to establish a framework for the expected changes in certain parameters following AVR.

Finally, it is important to note that, despite its infrequent use, the extent of left ventricular remodeling has significant prognostic implications post-AVR. Patients who do not exhibit improvements in LVEF and reductions in left ventricular mass and dimensions after AVR are at a higher risk for increased cardiovascular events (14, 39). In our opinion, further attention should be paid to the predictors of inadequate left ventricular remodeling after AVR, as this may aid in defining other criteria for AVR other than the severity of obstruction and left ventricular function.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the most extensive systematic review and meta-analysis conducted to assess the reverse LV remodeling profile in patients who underwent AVR. We excluded studies without a predefined follow-up period to obtain the most robust results possible. We performed meta-regression and subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity, identifying several variables in this context. To minimize publication and information bias, we searched different electronic bibliographic databases without applying exclusion criteria based on the date or language of publication and contacted authors whenever relevant information was missing.

Limitations of this meta-analysis are related to three main factors: the inherent source of variability regarding to measurements performed by echocardiography, the incomplete characterization of patients in some of the included studies, and the significant heterogeneity observed in our results.

First, a significant source of variability may be related to the fact that primary studies used TTE as the imaging LV assessment method, which is affected by inter-observer and intra-observer variability that can be a source of heterogeneity. For example, the non-significant reduction in LV volume compared to a significant reduction in LV diameter likely reflects the higher variability in echocardiographic measurements of three-dimensional parameters like LV volume, which tend to have a higher standard deviation compared to two-dimensional measurements like LV diameter. This variability could obscure significant findings. An analysis based on studies using CMR to evaluate LV could possibly reduce the heterogeneity across studies. However, it would be an undoubtedly less clinically useful analysis (40–42). Finally, another possible source of heterogeneity is the presence of prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM), which could influence the results by leading to worse hemodynamic function and LV reverse remodeling. Our study did not analyze PPM because it was not reported in most studies.

Second, other non-evaluated factors may influence the extent of left ventricular remodeling after AVR. In this work, we showed that LV reverse remodeling may differ according to several patient characteristics, namely, age, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and NYHA classification. However, the data available for analysis were sparse on information regarding the severity and duration of aortic stenosis, pre-existing LV remodeling, the presence of atrial fibrillation, associated valvular heart diseases, diastolic function, and patient–prosthesis mismatch that may also contribute to the extent of reverse remodeling. Furthermore, by using a summary or aggregate data from study publications, our meta-analysis may fail to identify patient characteristics that might be significant predictors of adequate LV remodeling. For example, previous works have shown that women have a more favorable LV remodeling after AVR than men (43). However, the available aggregate data were insufficient to characterize the impact of gender on LV reverse remodeling after AVR.

Finally, significant heterogeneity among studies was observed. Even though meta-regression and subgroup analysis were performed to identify possible variables that differed between studies and could explain the differences between primary studies, it must be noted that the included studies were mainly observational studies and included patients based on convenient criteria (i.e., patients who underwent AVR at a given institution), which added significant heterogeneity that cannot be controlled using regression techniques.

5 Conclusion

This is the most extensive systematic review and meta-analysis assessing reverse LV remodeling after AVR. Echocardiography demonstrates reverse LV remodeling as soon as 1 month after AVR, with reductions in MAG, LVM, and EDLVD, and improvement in AVA and LVEF.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FSN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CAM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AIP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BS-P: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JRS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL-M: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CS is supported by a grant from Bolsas de Doutoramento em Medicina from José de Mello Saúde, Portugal.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1407566/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Abecasis J Pinto DG Ramos S Masci PG Cardim N Gil V , et al. Left ventricular remodeling in degenerative aortic valve stenosis. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2021) 46:100801. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2021.100801

2.

Treibel TA Badiani S Lloyd G Moon JC . Multimodality imaging markers of adverse myocardial remodeling in aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2019) 12:1532–48. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.034

3.

Jin XY Petrou M Hu JT Nicol ED Pepper JR . Challenges and opportunities in improving left ventricular remodelling and clinical outcome following surgical and trans-catheter aortic valve replacement. Front Med. (2021) 15(3):416–37. 10.1007/s11684-021-0852-7

4.

Gavina C Falcao-Pires I Pinho P Manso MC Goncalves A Rocha-Goncalves F , et al. Relevance of residual left ventricular hypertrophy after surgery for isolated aortic stenosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2016) 49:952–9. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv240

5.

Ikonomidis I Tsoukas A Parthenakis F Gournizakis A Kassimatis A Rallidis L , et al. Four year follow up of aortic valve replacement for isolated aortic stenosis: a link between reduction in pressure overload, regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, and diastolic function. Heart. (2001) 86:309–16. 10.1136/heart.86.3.309

6.

Liberati A Altman DG Tetzlaff J Mulrow C Gøtzsche PC Ioannidis JPA , et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

7.

Dobson LE Musa TA Uddin A Fairbairn TA Swoboda PP Erhayiem B , et al. Acute reverse remodelling after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a link between myocardial fibrosis and left ventricular mass regression. Can J Cardiol. (2016) 32:1411–8. 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.04.009

8.

Campos V Adrio B Estévez F Mosquera VX Pérez J Cuenca JJ , et al. Aortic valve replacement with a Cryolife O’Brien stentless bioprosthesis. Rev Esp Cardiol. (2007) 60:45–50. 10.1157/13097925

9.

Gegenava T Vollema EM van Rosendael A Abou R Goedemans L van der Kley F , et al. Changes in left ventricular global longitudinal strain after transcatheter aortic valve implantation according to calcification burden of the thoracic aorta. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2019) 32:1058–66. 10.1016/j.echo.2019.05.011

10.

Ngo A Hassager C Thyregod HGH Søndergaard L Olsen PS Steinbrüchel D , et al. Differences in left ventricular remodelling in patients with aortic stenosis treated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement with CoreValve prostheses compared to surgery with porcine or bovine biological prostheses. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2018) 19:39–46. 10.1093/ehjci/jew321

11.

Gelsomino S Frassani R Porreca L Morocutti G Morelli A Livi U . Early and midterm results of model 300 Cryolife O’Brien stentless porcine aortic bioprosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg. (2001) 71:S297–301. 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02526-7

12.

Vizzardi E D’Aloia A Fiorina C Bugatti S Parrinello G Carlo MD , et al. Early regression of left ventricular mass associated with diastolic improvement after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2012) 25:1091–8. 10.1016/j.echo.2012.06.010

13.

Pibarot P Salaun E Dahou A Avenatti E Guzzetti E Annabi MS , et al. Echocardiographic results of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients. Circulation. (2020) 141:1527–37. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044574

14.

Izumi C Kitai T Kume T Onishi T Yuda S Hirata K , et al. Effect of left ventricular reverse remodeling on long-term outcomes after aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. (2019) 124:105–12. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.04.010

15.

Harrington CM Sorour N Gottbrecht M Nagy A Kovell LC Truong V , et al. Effect of transaortic valve intervention for aortic stenosis on myocardial mechanics. Am J Cardiol. (2021) 146:56–61. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.01.021

16.

Merdler I Loewenstein I Hochstadt A Morgan S Schwarzbard S Sadeh B , et al. Effectiveness and safety of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with aortic stenosis and variable ejection fractions (, 40%–49%, and ). Am J Cardiol. (2020) 125:583–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.10.059

17.

Martinovic I Farah I Everlien M Lindemann S Knez I Wittlinger T , et al. Eight-year results after aortic valve replacement with the Cryolife-O’Brien stentless aortic porcine bioprosthesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2005) 130:777–82. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.05.011

18.

Al-Rashid F Totzeck M Saur N Jánosi RA Lind A Mahabadi AA , et al. Global longitudinal strain is associated with better outcomes in transcatheter aortic valve replacement. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2020) 20:267. 10.1186/s12872-020-01556-4

19.

Thomson H . Haemodynamics and left ventricular mass regression: a comparison of the stentless, stented and mechanical aortic valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (1998) 13:572–5. 10.1016/S1010-7940(98)00058-X

20.

Ewe SH Muratori M Delgado V Pepi M Tamborini G Fusini L , et al. Hemodynamic and clinical impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58:1910–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.027

21.

Douglas PS Hahn RT Pibarot P Weissman NJ Stewart WJ Xu K , et al. Hemodynamic outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement and medical management in severe, inoperable aortic stenosis: a longitudinal echocardiographic study of cohort B of the PARTNER trial. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2015) 28:210–7. 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.009

22.

Ledwoch J Fröhlich C Olbrich I Poch F Thalmann R Fellner C , et al. Impact of sinus rhythm versus atrial fibrillation on left ventricular remodeling after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Clin Res Cardiol. (2021) 110:689–98. 10.1007/s00392-021-01810-5

23.

Al-Hijji MA Zack CJ Nkomo VT Pislaru SV Pellikka PA Reeder GS , et al. Left ventricular remodeling and function after transapical versus transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2019) 94:738–44. 10.1002/ccd.28074

24.

Weber A Büttner AL Rellecke P Petrov G Albert A Sixt SU , et al. Osteopontin as novel biomarker for reversibility of pressure overload induced left ventricular hypertrophy. Biomark Med. (2020) 14:513–23. 10.2217/bmm-2019-0410

25.

Fuster RG Argudo JAM Albarova OG Sos FH López SC Codoñer MB , et al. Patient-prosthesis mismatch in aortic valve replacement: really tolerable?Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2005) 27:441–9. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.11.022

26.

Theron A Ravis E Grisoli D Jaussaud N Morera P Candolfi P , et al. Rapid-deployment aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis: 1-year outcomes in 150 patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2017) 25:68–74. 10.1093/icvts/ivx050

27.

Chau KH Douglas PS Pibarot P Hahn RT Khalique OK Jaber WA , et al. Regression of left ventricular mass after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75:2446–58. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.042

28.

Ochiai T Saito S Yamanaka F Shishido K Tanaka Y Yamabe T , et al. Renin–angiotensin system blockade therapy after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Heart. (2018) 104:644–51. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311738

29.

Little SH Oh JK Gillam L Sengupta PP Orsinelli DA Cavalcante JL , et al. Self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical valve replacement in patients at high risk for surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9(6):e003426. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003426

30.

Ninomiya R Orii M Fujiwara J Yoshizawa M Nakajima Y Ishikawa Y , et al. Sex-related differences in cardiac remodeling and reverse remodeling after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis in a Japanese population. Int Heart J. (2020) 61:961–9. 10.1536/ihj.20-154

31.

Iliopoulos DC Deveja AR Androutsopoulou V Filias V Kastelanos E Satratzemis V , et al. Single-center experience using the Freedom SOLO aortic bioprosthesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2013) 146:96–102. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.06.041

32.

Beholz S Repossini A Livi U Schepens M Gabry ME Matschke K , et al. The Freedom SOLO valve for aortic valve replacement: clinical and hemodynamic results from a prospective multicenter trial. J Heart Valve Dis. (2010) 19:115–23. WE—Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI). .

33.

Fischlein T Meuris B Hakim-Meibodi K Misfeld M Carrel T Zembala M , et al. The sutureless aortic valve at 1 year: a large multicenter cohort study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2016) 151:1617–26. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.12.064

34.

Medvedofsky D Koifman E Miyoshi T Rogers T Wang Z Goldstein SA , et al. Usefulness of longitudinal strain to assess remodeling of right and left cardiac chambers following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. (2019) 124:253–61. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.04.029

35.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2023).

36.

Balduzzi S Rücker G Schwarzer G . How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. (2019) 22:153–60. 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

37.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD , et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

38.

Mehdipoor G Chen S Chatterjee S Torkian P Ben-Yehuda O Leon MB , et al. Cardiac structural changes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular magnetic resonance studies. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. (2020) 22:41. 10.1186/s12968-020-00629-9

39.

Wilde NG Mauri V Piayda K Al-Kassou B Shamekhi J Maier O , et al. Left ventricular reverse remodeling after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis. Hellenic J Cardiol. (2023) 74:1–7. 10.1016/j.hjc.2023.04.009

40.

Rigolli M Anandabaskaran S Christiansen JP Whalley GA . Bias associated with left ventricular quantification by multimodality imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. (2016) 3:e000388. 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000388

41.

Malik SB Chen N . Transthoracic echocardiography: pitfalls and limitations as delineated at cardiac CT and MR imaging. Radiographics. (2017) 37:383–406. 10.1148/rg.2017160105

42.

Aurich M André F Keller M Greiner S Hess A Buss SJ , et al. Assessment of left ventricular volumes with echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: real-life evaluation of standard versus new semiautomatic methods. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2014) 27:1017–24. 10.1016/j.echo.2014.07.006

43.

Iribarren AC AlBadri A Wei J Nelson MD Li D Makkar R , et al. Sex differences in aortic stenosis: identification of knowledge gaps for sex-specific personalized medicine. Am Heart J Plus Cardiol Res Pract. (2022) 21:100197. 10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100197

Summary

Keywords

aortic stenosis, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), reverse left ventricle remodeling, echocardiography

Citation

Sousa Nunes F, Amaral Marques C, Isabel Pinho A, Sousa-Pinto B, Beco A, Ricardo Silva J, Saraiva F, Macedo F, Leite-Moreira A and Sousa C (2024) Reverse left ventricular remodeling after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1407566. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1407566

Received

26 March 2024

Accepted

06 June 2024

Published

04 July 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Giulia Elena Mandoli, University of Siena, Italy

Reviewed by

Yohann Bohbot, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) d’Amiens, France

Maria Martin Fernandez, Central University Hospital of Asturias, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Sousa Nunes, Amaral Marques, Isabel Pinho, Sousa-Pinto, Beco, Ricardo Silva, Saraiva, Macedo, Leite-Moreira and Sousa.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: C. Amaral Marques catmarques@med.up.pt

These authors share co-first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.