Abstract

Background:

Early detection and diagnosis of venous thromboembolism are vital for effective treatment. To what extent methodological shortcomings exist in studies of diagnostic tests and whether this affects published test performance is unknown.

Objectives:

We aimed to assess the methodological quality of studies evaluating diagnostic tests for venous thromboembolic diseases and quantify the direction and impact of design characteristics on diagnostic performance.

Methods:

We conducted a literature search using Medline and Embase databases for systematic reviews summarizing diagnostic accuracy studies for five target disorders associated with venous thromboembolism. The following data were extracted for each primary study: methodological characteristics, the risk of bias scored by the QUADAS QUADAS-2 instrument, and numbers of true-positives, true-negatives, false-positives, and false-negatives. In a meta-analysis, we compared diagnostic accuracy measures from studies unlikely to be biased with those likely to be biased.

Results:

Eighty-five systematic reviews comprising 1’818 primary studies were included. Adequate quality assessment tools were used in 43 systematic reviews only (51%). The risk of bias was estimated to be low for all items in 23% of the primary studies. A high or unclear risk of bias in particular domains of the QUADAS/QUADAS-2 tool was associated with marked differences in the reported sensitivity and specificity.

Conclusions:

Significant limitations in the methodological quality of studies assessing diagnostic tests for venous thromboembolic disorders exist, and studies at risk of bias are unlikely to report valid estimates of test performance. Established guidelines for evaluation of diagnostic tests should be more systematically adopted.

Systematic Review Registration:

PROSPERO (CRD 42021264912).

Introduction

Treatment of venous thromboembolism can only be initiated once a diagnosis is established. The diagnostic workup is the first step in any medical encounter, and it is acknowledged that the quality of the diagnostic process determines the quality of care to a large amount (1). A delayed diagnosis of venous thromboembolic diseases such as pulmonary embolism or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia might result in severe damage, persistent sequelae, or even death (2, 3). Accordingly, false diagnosis and overtreatment might not only result in increased costs but also direct adverse events, the initiation of additional investigations, and withdrawal of treatments necessary for other diseases (4, 5). Key parts of the diagnostic work-up are medical tests such as laboratory assays or imaging studies (6). Thus, the effectiveness of the diagnostic process depends on the performance of respective tests (3). Suboptimal tests might lead to increased numbers of wrong diagnoses or unnecessary delays in securing a correct diagnosis (3, 4, 7). In addition, it has been recognized that sophisticated and expensive tests that are disseminated without suitable evaluations can have marginal clinical value and economic adversity (5).

Diagnostic accuracy studies evaluating the clinical performance of laboratory tests are an essential part of the implementation process (5). Using the diagnostic accuracy measures obtained in these studies, the post-test probability of a particular disease can be estimated in individual patients, thus clarifying the diagnostic utility of the test (8). However, methodological shortcomings and design-related bias of diagnostic accuracy studies can easily lead to biased study results and erroneous conclusions on the clinical value of medical tests (1). Well known historical examples and some empirical evidence illustrate how methodological shortcomings in diagnostic accuracy studies may lead to wrong conclusions and an unjustified subsequent implementation in clinical practice (9–14). A number of guidelines and tools for assessing and improving quality of studies evaluating diagnostic tests have been developed in the last decades to overcome these problems. In particular, the STARD guideline focuses on the accurate design and reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies and the QUADAS-2 tool assesses the methodological quality of studies to be used in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (15–17). From previous studies we know that non-adherence can generate bias (9–14). The question appears to what extent design-related deficiencies exist in studies of diagnostic tests for venous thromboembolism and whether these affect published test performance.

In this study we systematically assessed the methodological quality of studies evaluating diagnostic tests for venous thromboembolic diseases and quantified the direction and impact of studies at risk of bias on diagnostic performance.

Methods

Study design, search strategy, and data sources

A protocol was developed and submitted to the PROSPERO international register of systematic reviews (CRD 42021264912). A sensitive search strategy was developed to identify systematic reviews summarizing diagnostic accuracy studies for the tests used to diagnose venous thromboembolic diseases; the search strategy is given in the Supplementary Material. To get a comprehensive dataset, we included all disease entities in the search strategy that are associated with venous thromboembolism: venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, lower extremity deep vein thrombosis, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. We decided against antiphospholipid antibody syndrome because it is often associated with other clinical sequalae. The search strategy was tested in a set of 10 index publications. The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched without any restrictions regarding date or language. The database search was complemented by screening reference lists of included studies. The literature search was updated last time on the 20th of November 2020. The manuscript was prepared using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) (18).

Study eligibility

The literature search and selection of publications for full-text review was done by three authors (LB, TMR, LF). Full-text review and assessment for eligibility was done independently by two authors (LB, LF). Two reviewers (MN, LMB) arbitrated unclear cases. Inclusion criteria were (1) systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies, (2) evaluating one or more index tests used to identify one of the mentioned disease entities, and (4) sufficient details from included studies to generate 2 by 2 contingency tables.

Data extraction

All data were extracted in a standardized extraction form. The following data items were extracted from each included systematic review: number of studies, employment, and type of a quality assessment tool. The primary studies included in the systematic review were assessed to extract the following data: sample size, numbers of affected and unaffected patients, true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives. In addition, the QUADAS QUADAS-2 rating assigned to these studies by the authors of the systematic review were recorded: risk of bias and applicability concerns with regard to (a) patient selection, (b) index test, (c) reference standard test, and (d) flow and timing. Four reviewers (LB, MN, LF, LMB) independently did data extraction and disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Measures of methodological quality

We assessed the methodological quality of included primary studies in terms of precision and risk of bias. We first analyzed included primary studies in terms of sample size (19). We then evaluated whether an included systematic review had adequately applied a quality assessment tool. The methodological quality of the primary studies, as assessed by the review authors, was extracted, expressed as QUADAS/QUADAS-2 results. We decided to rely on the assessment of previous authors since the application of QUADAS-2 has to be done in the context of and adapted to the respective research question.

Statistical analysis

Index tests were categorized into (a) ultrasound techniques, (b) other imaging studies, (c) laboratory tests, and (d) other tests. To assess the effects of methodological deficiencies on the reported diagnostic test accuracy, various meta-regression analyses were performed. Bivariate models as described by Reitsma et al. and implemented in the “mada” package for “R” were fitted to the data of each test category (20–22). We decided against performing a meta-analysis for the studies that were categorized as “other tests” because this group only contained 6 studies and estimates would be unstable. The bivariate Reitsma model is a random-effects linear mixed model that pools the logit transformed sensitivities and false-positive rates together.

Each of the QUADAS-criteria (coded as “low risk of bias” or “not low risk of bias”) was separately entered into the meta-regression as the independent variable. The back-transformed regression coefficients and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were then displayed in a forest plot using the “forestplot” package (23). The same procedure was followed to also analyze the impact of adjudication as the reference standard. For this analysis, we assumed that the heterogeneity between studies is high since they comprise different tests and, therefore, a random-effects model was chosen. For the purposes of the primary analysis, the effects of methodological deficiencies were assumed to be similar across test categories. As a a sensitivity analysis, we conducted a multivariable meta-regression analysis of the diagnostic odds ratios (DOR) using the “meta” and “metafor” packages for R. This analysis included adjustments for the meta-analysis and all domains of the QUADAS-2 tool. A forest plot showing the relative diagnostic odds ratios comparing low risk of bias high applicability with not low risk of bias not high applicability was created.

Results

Study selection

After deduplication, we identified 876 potentially eligible articles (Figure 1). One-hundred and forty-three were selected for full-text screening. Out of these, we excluded 26 articles because of the publication type (no systematic review), 12 records because of a different scope, 15 articles because of insufficient data, and five more duplicates. Finally, we included 85 systematic reviews (8, 24–105), summarizing the results of 1'818 primary studies (Supplementary Table S1). For 308 primary studies, QUADAS/QUADAS-2 scores were available in 20 systematic reviews (8, 30, 31, 38, 46, 48–51, 53–55, 58, 67, 76, 81, 85, 93, 99, 104). These studies were included in our meta-analysis of design-related bias (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1

Flow of the studies.

Study characteristics and sample size

The characteristics of included systematic reviews are given in Supplementary Table S1. The included studies covered the whole spectrum of diagnostic problems associated with venous thromboembolism, and a wide range of diagnostic tests. The number of primary studies ranged from 3 to 108. QUADAS QUADAS-2 was used as a quality assessment tool in 43 systematic reviews (51%), and a self-constructed tool in 14 studies (16%). No formal quality assessment was done in 28 studies (33%). The systematic reviews were published between 1991 and 2020 (median 2014).

The characteristics of all primary studies included in the meta-analysis are reported in Supplementary Table S2. The number of patients ranged from 7 to 376 (median 159). The prevalence varied between 0% and 94% (median 23%). Laboratory tests were studied in 140 primary studies (46%), ultrasound techniques in 105 studies (34%), other imaging studies in 57 (18%), and other tests in 6 studies (2%).

Quality assessment

Among 308 primary studies with QUADAS QUADAS-2 ratings available, a low risk of bias in all domains was reported in 120 studies only (39%; Supplementary Table S2). The risk of bias was estimated to be “high” or “unclear” with regard to the patient selection in 101 studies (36%), the index test in 82 studies (28%), the reference test in 102 primary studies (35%), and the flow and timing in 104 studies (36%). Applicability concerns were high or unclear with regard to patient selection in 56 studies (30%), with regard to index test in 28 studies (16%), and with regard to the reference standard test in 30 studies (16%). No applicability concerns in all domains were reported in 126 studies (62%).

Design-related bias and published test performance

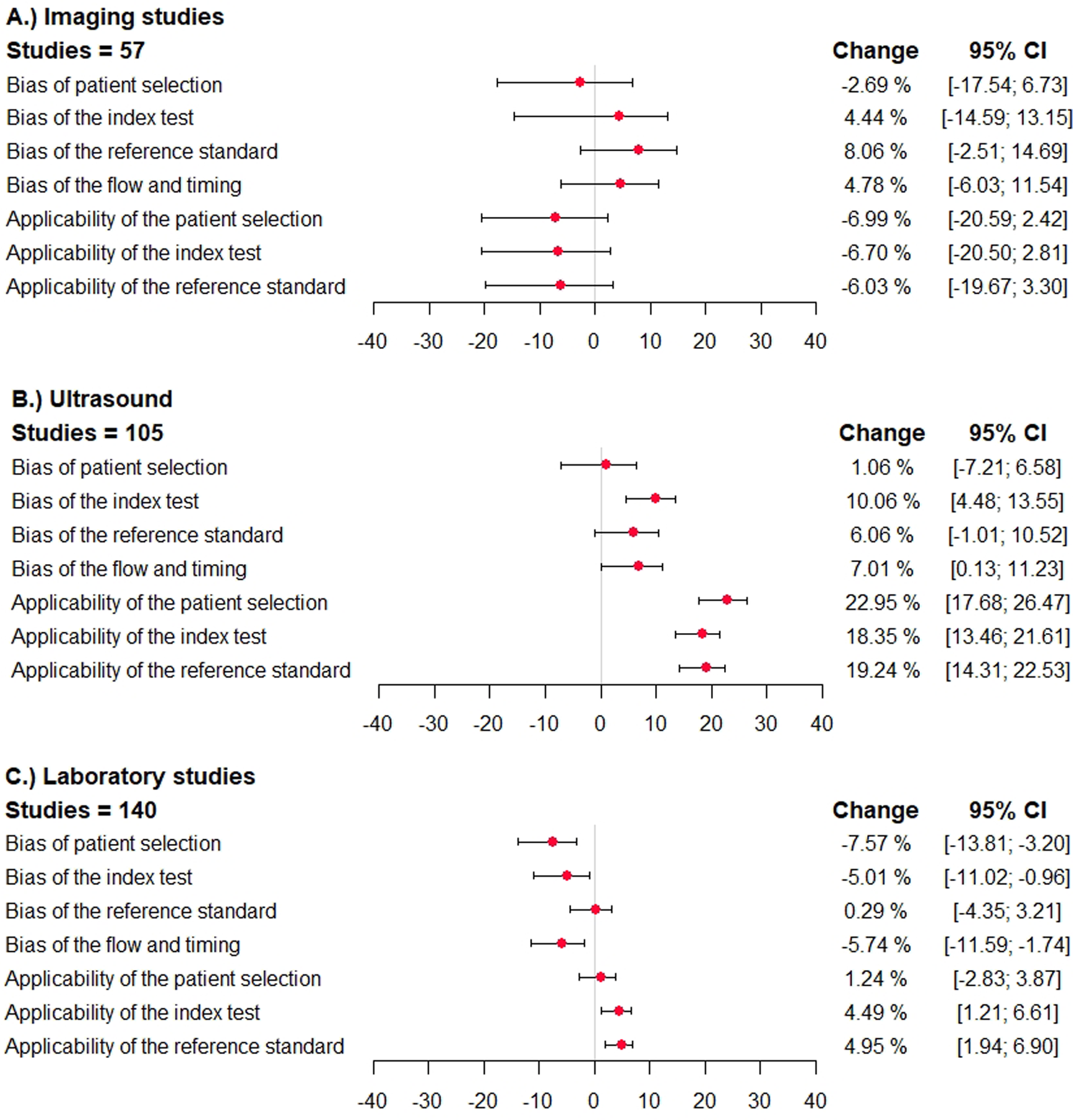

The direction and impact of methodological shortcomings on summary sensitivity are shown in Figure 2. The difference is shown per item of the QUADAS/QUADAS-2 tool in three index test categories (imaging studies, ultrasound studies, and laboratory studies).

Figure 2

Direction and impact of methodological bias on summary sensitivity in diagnostic accuracy studies for venous thromboembolism. The difference in sensitivity and the 95% confidence interval is shown (percentages) in studies reporting on ultrasound studies, other imaging studies, and laboratory tests. The different domains of the QUADAS/QUADAS-2 tool are given. A deviation to the right corresponds to an overestimation of sensitivity, and a deviation to the left corresponds to an underestimation. (A) imaging studies, (B) ultrasound studies, (C) laboratory studies.

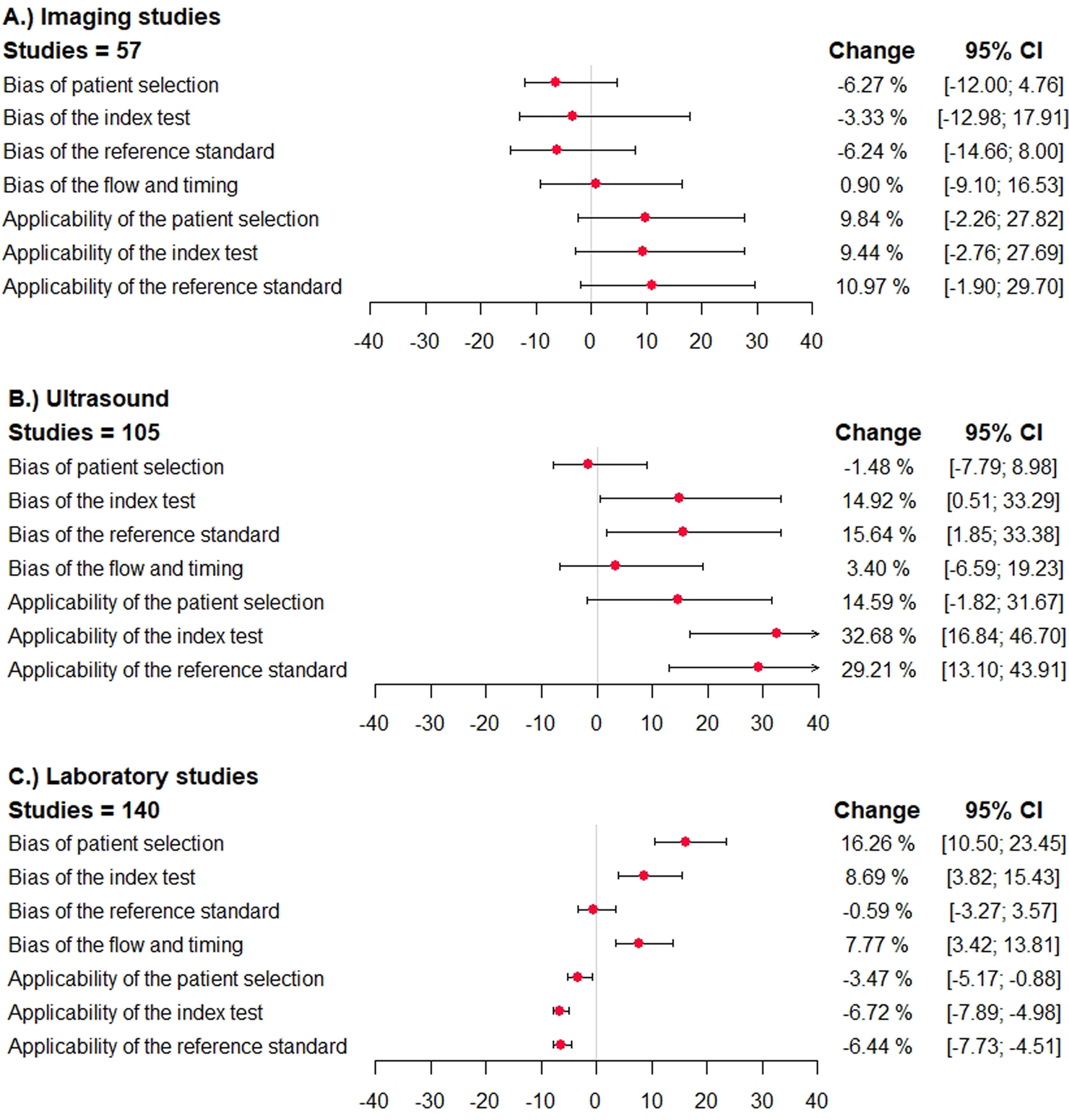

In primary studies categorized to have a high (or unclear) risk of bias with regard to patient selection, the summary sensitivity was lower in case of imaging studies [−2.7%; 95% confidence interval (−17.5; 6.7)], simila in case of ultrasound studies [1.1%; 95% confidence interval (−7.2; 6.6)], and significantly lower in laboratory tests [−7.6%; 95% confidence interval (−13.8; −3.2)]. The specificity was similar in case of imaging studies and ultrasound studies and significantly higher in studies assessing laboratory tests [16.3%; 95% confidence interval (10.5; 23.5)] (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Direction and impact of methodological bias on summary specificity in diagnostic accuracy studies for venous thromboembolism. The difference in specificity and the 95% confidence interval is shown (percentages) in studies reporting on ultrasound studies, other imaging studies, and laboratory tests. The different domains of the QUADAS/QUADAS-2 tool are given. A deviation to the right corresponds to an overestimation of specificity, and a deviation to the left corresponds to an underestimation. (A) imaging studies, (B) ultrasound studies, (C) laboratory studies.

In studies categorized to have a high risk of bias with regard to the index test, reference standard test, or flow and timing, the sensitivity was higher in case of imaging studies, ultrasound studies, and lower in laboratory tests (Figure 2). The specificity was mostly lower in imaging studies, and higher in ultrasound studies and laboratory tests (Figure 3).

In studies categorized to have applicability concerns, the sensitivity was lower in imaging studies, higher in case of ultrasound studies and laboratory studies. The specificity was higher in imaging studies and ultrasound studies, and significantly lower in laboratory tests.

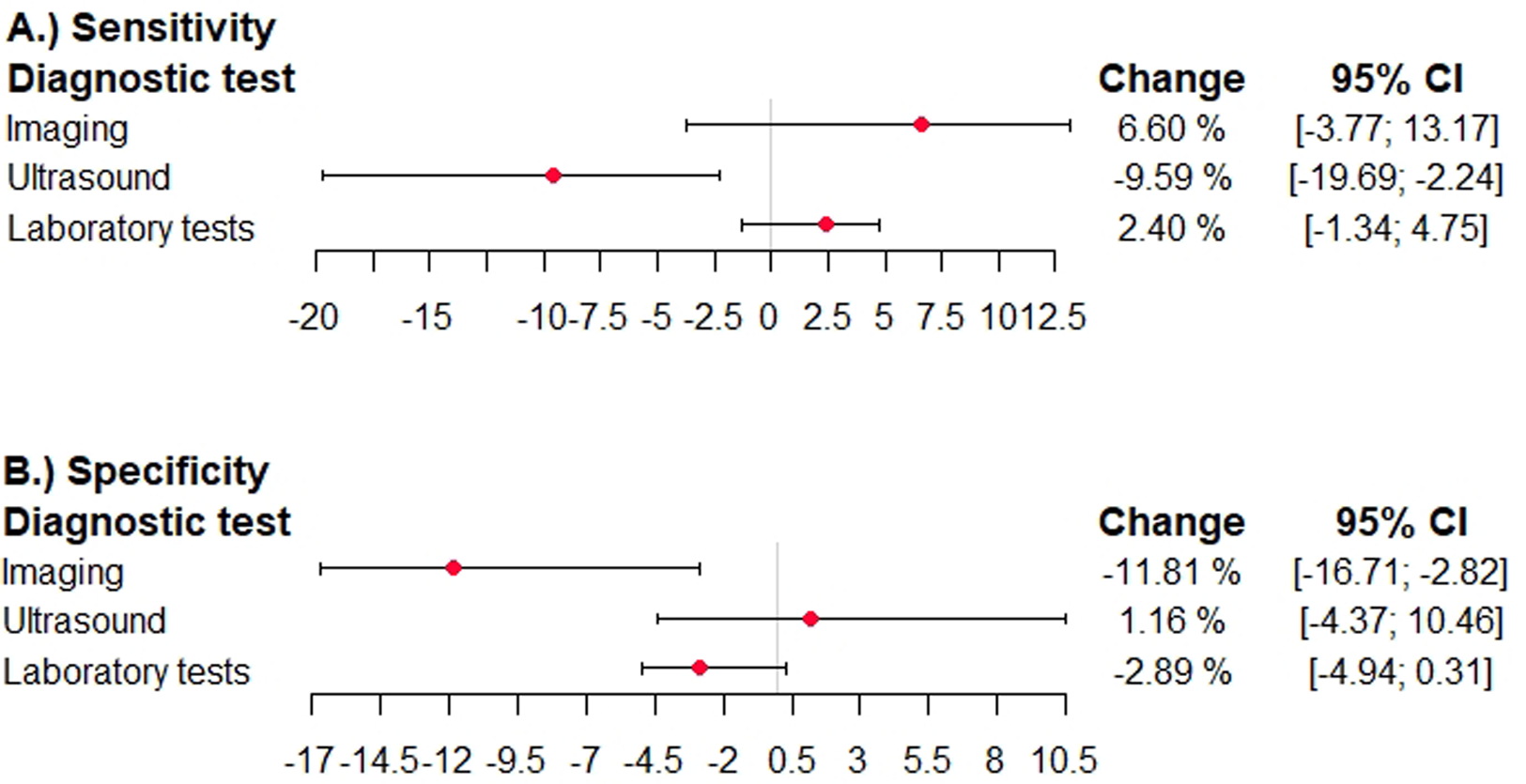

In studies using adjudication as the reference standard, the sensitivity was higher in imaging tests, significantly lower in ultrasound studies [−9.6%; 95% confidence interval (−19.7; −2.2)], and higher in laboratory tests (Figure 4). The specificity was significantly lower in imaging tests [−11.8%; 95% confidence interval (−16.7; −2.8)], higher in ultrasound studies and lower in laboratory tests (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Effects of expert adjudication as reference standard on summary test performance in diagnostic accuracy studies for venous thromboembolism. The difference in sensitivity and specficitiy and the 95% confidence interval is shown in studies reporting on ultrasound studies, other imaging studies, and laboratory tests. The different domains of the QUADAS QUADAS-2 tool are given. A deviation to the right corresponds to an overestimation, and a deviation to the left corresponds to an underestimation. (A) sensitivity diagnostic test, (B) specificity diagnostic test.

Sensitivity analysis

As a sensitivity analysis we performed a multivariable meta regression using DOR. When adjusting for the meta-analysis effects were attenuated and did not achieve statistical significance. Reported DOR were higher in studies with non-low risk of bias in the domains of the index test (RDOR 1.45; 95% CI 0.75, 2.84), reference standard (RDOR 1.22; 95% CI 0.62, 2.41), flow and timing (RDOR 1.21; 95% CI 0.72, 2.22) and non-high applicability of the reference standard (RDOR 1.94, 95% CI 0.72, 5.26). A lower reported DOR was present in studies with non-low risk of bias in the patient selection (RDOR 0.74; 95% CI 0.36, 1.51) and non-high applicability in the patient selection (RDOR 0.88; 95% CI 0.37, 2.09) and in the performance of the index test (RDOR 0.54; 95% CI 0.20, 1.46).

Discussion

In a comprehensive systematic review, we found significant shortcomings in the methodological quality of studies included in 85 systematic reviews of diagnostic tests used to diagnose venous thromboembolic disorders. Adequate quality assessment instruments were used in half of the systematic reviews only. Among 308 primary studies included in a meta-analysis, the number of patients was limited and a low risk of bias in all domains was reported in 120 studies only (39%). A high or unclear risk of bias in particular domains of the QUADAS/QUADAS-2 tool was associated with marked differences in the reported sensitivity and specificity.

We are unaware of previous studies investigating extent and effects of methodological shortcomings systematically in diagnostic accuracy studies for venous thromboembolic diseases. Our results are in-line with previous publications in general medical journals confirming that methodological shortcomings are common and the quality of reporting restricted (9, 12). Some evidence exists regarding a systematic bias due to methodological shortcomings. In 1999 Lijmer and colleagues reported on systematic overestimation of the diagnostic performance of a test in studies in which particular methodological requirements were not met (9). The issues they found to have a high risk correspond very well to the domains of the QUADAS-2 tool we identified as such: “patient selection” and “reference test”. Rutjes et al. also focused on a number of methodological factors associated with a risk of bias in diagnostic accuracy estimates (12). In agreement with our results, these authors identified issues associated with patient selection as particularly sensitive to bias. Our results are also in line with a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies investigating the accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting silicone breast implant ruptures (11). The authors identified patient selection procedure as particularly sensitive to bias. Other authors mentioned disease prevalence and details of data analysis as potential sources of bias (106). In contrast to these previous investigations, we observed a relationship between bias and quality status according to QUADAS-2. Boyer and colleagues studied diagnostic accuracy studies of carpal tunnel syndrome and concluded that these studies are unlikely to report results that are applicable to actual clinical practice (107). Fontela and colleagues found that quality and reporting was limited in diagnostic accuracy studies focused on TB, HIV and Malaria (108). Other studies in other domains found that the sample size in diagnostic accuracy studies was limited and a priori sample size calculations were rare (19, 109).

In this investigation, we studied methodological issues in a large number of studies investigating a broad range of diagnostic tests for detecting all important diseases associated with venous thromboembolism. Arguably our sample is a positive selection of the full body of evidence, since only studies included in systematic reviews were considered. Furthermore, there could also be a publication bias, since studies with negative results are less frequently published. Thus, the actual problem might be worse when considering the complete diagnostic literature on venous thromboembolic diseases. As another important limitation, we are not able to conduct sensitivity analyses with single diagnostic tests because of the numbers of diagnostic accuracy studies available. This reflects the general methodological problems and limitations in the validity of previous studies. The risk of bias is estimated by higher or lower measures of accuracy in the presence or absence of certain methodological limitations. In every analysis, a group of diagnostic tests is analyzed that is more or less heterogeneous. This introduces a potential confounder whose influence can hardly be accounted for. To directly measure the effect of methodological aspects on reported diagnostic accuracy, and thus the extent of bias, would require a large number of studies of different designs of the same diagnostic test. As these do not yet exist, the bias cannot be measured directly. As a further limitation, we chose a certain set of diseases with VTE, and we decided against the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (because it often has other clinical sequelae). We cannot completely rule out the possibility that the results of our study would have been different. Another limitation is that we cannot go back to the level of individual tests and indicate the extent of over- or underestimation. The main reason for this is that we do not know the “true” value. Another reason is that there are too few studies within each test and therefore too little variance in the quality variables. However, we have now uploaded the raw data as Excel files in the Supplementary Material. Interested readers can go back to the study or test level and look at the methodological quality and the reported diagnostic utility.

Using a comprehensive approach, we obtained empirical evidence for significant shortcomings in the methodological quality of studies assessing diagnostic tests for venous thromboembolic diseases. Although deviations can take on very different directions and extents depending on the type of methodological limitation and diagnostic test, aspects of applicability are significant. Interestingly, laboratory tests appear particularly prone to deviations. Moreover, the results of our meta-analysis suggest that these shortcomings can result in biased accuracy estimates. This observation calls for increased efforts to implement current guidelines for reporting and assessment of methodological quality (15, 17). Several authors have demanded a phased evaluation of medical tests, in parallel with the evaluation required for FDA-approval of new drugs (5, 7, 110–112). In a first phase, the analytical characteristics and the technical accuracy including reproducibility are evaluated. In a second phase, the diagnostic accuracy will be investigated in an adequate study design. These studies will be complemented by a phase three determining health outcomes (mortality and morbidity) of using the test. Afterwards, the cost-effectiveness must be evaluated, decision-making algorithms developed, and the organizational impact evaluated. The advantage of a phased evaluation is that further evaluation will be stopped after insufficient results at an early stage. Thus, significant harm to patients associated with a premature implementation of medical tests will be avoided. Furthermore, a relevant amount of costs that are associated with the use of tests with unclear value can be saved.

This comprehensive systematic review identified significant limitations in the methodological quality of studies assessing diagnostic tests used to diagnose venous thromboembolic disorders. Design-related shortcomings were associated with marked differences in the reported sensitivity and specificity. Our data suggest that studies at risk of bias because of methodological shortcomings are unlikely to report valid estimates of test performance.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LB: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HN: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HT: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WW: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was funded by the Research Fund Hematology Luzerner Kantonsspital. MN is supported by a research grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (215574). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

MN has received research grants, material support, or lecture fees from Siemens healthineers, Bühlmann laboratories, Pentapharm, Euroimmun, Technoclone, Werfen, Abbott, and Roche diagnostics. LF and LB is employed by Medignition Inc., WW has received research grants, lecture fees, and consultant fees from Roche Diagnostics, St. Jude Medical, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, MEDA Pharma, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and sanofi-avensis.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1420000/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Knottnerus JA Buntinx F . The Evidence Base of Clinical Diagnosis: Theory and Methods of Diagnostic Research. 2nd ednOxford; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Pub./BMJ Books (2009). p. 302.

2.

Ageno W Agnelli G Imberti D Moia M Palareti G Pistelli R et al Factors associated with the timing of diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: results from the MASTER registry. Thromb Res. (2008) 121:751–6. 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.08.009

3.

Lim W Le Gal G Bates SM Righini M Haramati LB Lang E et al American Society of hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. (2018) 2:3226–56. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024828

4.

Bounameaux H Perrier A Righini M . Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: an update. Vasc Med. (2010) 15:399–406. 10.1177/1358863X10378788

5.

Nagler M . Translating laboratory tests into clinical practice: a conceptual framework. Hamostaseologie. (2020) 40:420–9. 10.1055/a-1227-8008

6.

Wells PS Ihaddadene R Reilly A Forgie MA . Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: 20 years of progress. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 168:131–40. 10.7326/M17-0291

7.

Lijmer JG Leeflang M Bossuyt PMM . Proposals for a phased evaluation of medical tests. Med Decis Making. (2009) 29:E13–21. 10.1177/0272989X09336144

8.

Nagler M . BachmannLMten CateHten Cate-HoekA. Diagnostic value of immunoassays for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. (2016) 127:546–57. 10.1182/blood-2015-07-661215

9.

Lijmer JG . Empirical evidence of design-related bias in studies of diagnostic tests. JAMA. (1999) 282:1061. 10.1001/jama.282.11.1061

10.

Nierenberg AA . How to evaluate a diagnostic marker test. Lessons from the rise and fall of dexamethasone suppression test. JAMA. (1988) 259:1699–702. 10.1001/jama.1988.03720110061036

11.

Song JW Kim HM Bellfi LT Chung KC . The effect of study design biases on the diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging for detecting silicone breast implant ruptures: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. (2011) 127:1029–44. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182043630

12.

Rutjes AWS Reitsma JB Di Nisio M Smidt N van Rijn JC Bossuyt PMM . Evidence of bias and variation in diagnostic accuracy studies. CMAJ. (2006) 174:469–76. 10.1503/cmaj.050090

13.

Fletcher RH . Carcinoembryonic antigen. Ann Intern Med. (1986) 104:66–73. 10.7326/0003-4819-104-1-66

14.

Lensing AWA Hirsh J . 125I-Fibrinogen leg scanning: reassessment of its role for the diagnosis of venous thrombosis in post-operative patients. Thromb Haemost. (1993) 69:002–7. 10.1055/s-0038-1651177

15.

Bossuyt PM Reitsma JB Bruns DE Gatsonis CA Glasziou PP Irwig LM et al Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Ann Intern Med. (2003) 138(1):40–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00010

16.

Whiting P Rutjes AW Reitsma JB Bossuyt PM Kleijnen J . The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2003) 3:25. 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25

17.

Whiting PF . QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:529. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009

18.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

19.

Bachmann LM Puhan MA ter Riet G Bossuyt PM . Sample sizes of studies on diagnostic accuracy: literature survey. Br Med J. (2006) 332:1127–9. 10.1136/bmj.38793.637789.2F

20.

Reitsma JB Glas AS Rutjes AWS Scholten RJPM Bossuyt PM Zwinderman AH . Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. (2005) 58:982–90. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022

21.

Doebler P Holling H . Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy with mada.21.

22.

Core Team R . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2019).

23.

Gordon M Lumley T . forestplot: Advanced Forest Plot Using “grid” Graphics. (2021). Available online at:https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=forestplot (accessed November 20, 2020).

24.

Lysdahlgaard S Hess S Gerke O Weber Kusk M . A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of spectral CT compared to scintigraphy in the diagnosis of acute and chronic pulmonary embolisms. Eur Radiol. (2020) 30:3624–33. 10.1007/s00330-020-06735-7

25.

Kassaï B Boissel J-P Cucherat M Sonie S Shah NR Leizorovicz A . A systematic review of the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis in asymptomatic patients. Thromb Haemost. (2004) 91:655–66. 10.1160/TH03-11-0722

26.

Brown W Lunati M Maceroli M Ernst A Staley C Johnson R et al Ability of thromboelastography to detect hypercoagulability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. (2020) 34:278–86. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001714

27.

Pomero F Dentali F Borretta V Bonzini M Melchio R Douketis JD et al Accuracy of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography in the diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemostasis. (2013) 109:137–45. 10.1160/TH12-07-0473

28.

Wells PS Lensing AWA Davidson BL Prins MH Hirsh J . Accuracy of ultrasound for the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis in asymptomatic patients after orthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. (1995) 122:47–53. 10.7326/0003-4819-122-1-199501010-00008

29.

Castro AA De Lima FJC De Sousa-Rodrigues CF Barbosa FT . Accuracy of ultrasound to detect thrombosis in pregnancy: a systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras. (2017) 63:278–83. 10.1590/1806-9282.63.03.278

30.

Manara A D’Hoore W Thys F . Capnography as a diagnostic tool for pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. (2013) 62:584–91. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.04.010

31.

Jiang JJ Schipper ON Whyte N Koh JL Toolan BC . Comparison of perioperative complications and hospitalization outcomes after ankle arthrodesis versus total ankle arthroplasty from 2002 to 2011. Foot Ankle Int. (2015) 36:360–8. 10.1177/1071100714558511

32.

Rathbun SW Raskob GE Whitsett TL . Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2000) 132:227–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00009

33.

Quiroz R Kucher N Zou KH Kipfmueller F Costello P Goldhaber SZ et al Clinical validity of a negative computed tomography scan in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc. (2005) 293:2012–7. 10.1001/jama.293.16.2012

34.

Lee MJ Sayers AE Drake TM Singh P Bradburn M Wilson TR et al Malnutrition, nutritional interventions and clinical outcomes of patients with acute small bowel obstruction: results from a national, multicentre, prospective audit. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e029235. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029235

35.

Chen F Shen Y-H Zhu X-Q Zheng J Wu F-J . Comparison between CT and MRI in the assessment of pulmonary embolism. Medicine (Baltimore). (2017) 96:e8935. 10.1097/MD.0000000000008935

36.

Shen JH Chen HL Chen JR Xing JL Gu P Zhu BF . Comparison of the wells score with the revised Geneva score for assessing suspected pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2016) 41:482–92. 10.1007/s11239-015-1250-2

37.

Tromeur C van der Pol LM Le Roux PY Ende-Verhaar Y Salaun PY Leroyer C et al Computed tomography pulmonary angiography versus ventilation-perfusion lung scanning for diagnosing pulmonary embolism during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica. (2019) 104:176–88. 10.3324/haematol.2018.196121

38.

Schouten HJ Geersing GJ Koek HL Zuithoff NPA Janssen KJM Douma RA et al Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). (2013) 346:1–13. 10.1136/bmj.f2492

39.

Safriel Y Zinn H . CT Pulmonary angiography in the detection of pulmonary embol. A meta-analysis of sensitivities and specificities. Clin Imaging. (2002) 26:101–5. 10.1016/S0899-7071(01)00366-7

40.

Hogg K Brown G Dunning J Wright J Carley S Foex B et al Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with CT pulmonary angiography: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. (2006) 23:172–8. 10.1136/emj.2005.029397

41.

Stein PD Hull RD Patel KC Olson RE Ghali WA Brant R et al d-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. (2004) 140:589–602. 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00005

42.

Alons IME Jellema K Wermer MJH Algra A . D-dimer for the exclusion of cerebral venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis of low risk patients with isolated headache. BMC Neurol. (2015) 15:1–7. 10.1186/s12883-014-0245-5

43.

Lucassen W Geersing GJ Erkens PMG Reitsma JB Moons KGM Büller H et al Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:448–60. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00007

44.

Heim SW Schectman JM Siadaty MS Philbrick JT . D-dimer testing for deep venous thrombosis: a metaanalysis. Clin Chem. (2004) 50:1136–47. 10.1373/clinchem.2004.031765

45.

Dentali F Squizzato A Marchesi C Bonzini M Ferro JM Ageno W . D-dimer testing in the diagnosis of cerebral vein thrombosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of the literature. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2012) 10:582–9. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04637.x

46.

Yue K . Diagnosis efficiency for pulmonary embolism using magnetic resonance imaging method: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2015) 8:14416–23.

47.

Nijkeuter M Hovens MMC Davidson BL Huisman MV . Resolution of thromboemboli in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Chest. (2006) 129:192–7. 10.1378/chest.129.1.192

48.

Bhatt M Braun C Patel P Patel P Begum H Wiercioch W et al Diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:1250–64. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000960

49.

Patel P Patel P Bhatt M Braun C Begum H Wiercioch W et al Systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:4296–311. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001052

50.

Zhang D Li F Du X Zhang X Zhang Z Zhao W et al Diagnostic accuracy of biomarker D-dimer in patients after stroke suspected from venous thromboembolism: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. (2019) 63:126–34. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.09.011

51.

Kagima J Stolbrink M Masheti S Mbaiyani C Munubi A Joekes E et al Diagnostic accuracy of combined thoracic and cardiac sonography for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2020) 15:1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0235940

52.

Abdellatif W Ebada MA Alkanj S Negida A Murray N Khosa F et al Diagnostic accuracy of dual-energy CT in detection of acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Assoc Radiol J. (2021) 72:285–92. 10.1177/0846537120902062

53.

Husseinzadeh HD Gimotty PA Pishko AM Buckley M Warkentin TE Cuker A . Diagnostic accuracy of IgG-specific versus polyspecific enzyme-linked immunoassays in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2017) 15:1203–12. 10.1111/jth.13692

54.

Squizzato A Rancan E Dentali F Bonzini M Guasti L Steidl L et al Diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound for pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2013) 11:1269–78. 10.1111/jth.12232

55.

Squizzato A Pomero F Allione A Priotto R Riva N Huisman MV et al Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a bivariate meta-analysis. Thromb Res. (2017) 154:64–72. 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.03.027

56.

Singh B Parsaik AK Agarwal D Surana A Mascarenhas SS Chandra S . Diagnostic accuracy of pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. (2012) 59:517–520.e4. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.022

57.

Sun L Gimotty PA Lakshmanan S Cuker A . Diagnostic accuracy of rapid immunoassays for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemostasis. (2016) 115:1044–55. 10.1160/TH15-06-0523

58.

Kraaijpoel N Bleker SM Meyer G Mahé I Muñoz A Bertoletti L et al Treatment and long-term clinical outcomes of incidental pulmonary embolism in patients with cancer: an international prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:1713–20. 10.1200/JCO.18.01977

59.

Da Costa Rodrigues J Alzuphar S Combescure C Le Gal G Perrier A . Diagnostic characteristics of lower limb venous compression ultrasonography in suspected pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2016) 14:1765–72. 10.1111/jth.13407

60.

Laurentius A Ariani R . Diagnostic comparison of anterior leads T-wave inversion and McGinn-white sign in suspected acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hong Kong J Emergency Med. (2023) 30(1):54–60. 10.1177/1024907920966520

61.

Zhou M Hu Y Long X Liu D Liu L Dong C et al Diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance imaging for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2015) 13:1623–34. 10.1111/jth.13054

62.

Febra C Macedo A . Diagnostic role of mean-platelet volume in acute pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. (2020) 14. 10.1177/1179548420956365

63.

Kruip MJHA Leclercq MGL van der Heul C Prins MH Büller HR . Diagnostic strategies for excluding pulmonary embolism in clinical outcome studies. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2003) 138:941–51. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00005

64.

Thomas SM Goodacre SW Sampson FC van Beek EJR . Diagnostic value of CT for deep vein thrombosis: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Radiol. (2008) 63:299–304. 10.1016/j.crad.2007.09.010

65.

Geersing GJ Janssen KJM Oudega R Bax L Hoes AW Reitsma JB et al Excluding venous thromboembolism using point of care D-dimer tests in outpatients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ. (2009) 339:450. 10.1136/bmj.b2990

66.

Geersing GJ Zuithoff NPA Kearon C Anderson DR Ten Cate-Hoek AJ Elf JL et al Exclusion of deep vein thrombosis using the wells rule in clinically important subgroups: individual patient data meta-analysis. BMJ. (2014) 348:1–18. 10.1136/bmj.g1340

67.

Phillips JJ Straiton J Staff RT . Planar and SPECT ventilation/perfusion imaging and computed tomography for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature, and cost and dose comparison. Eur J Radiol. (2015) 84:1392–400. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.03.013

68.

Fabiá Valls MJ van der Hulle T den Exter PL Mos ICM Huisman MV Klok FA . Performance of a diagnostic algorithm based on a prediction rule, D-dimer and CT-scan for pulmonary embolism in patients with previous venous thromboembolism. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. (2015) 113:406–13. 10.1160/TH14-06-0488

69.

Hess S Frary EC Gerke O Werner T Alavi A Høilund-Carlsen PF . FDG-PET/CT in venous thromboembolism. Clin Transl Imaging. (2018) 6:369–78. 10.1007/s40336-018-0296-5

70.

Krishan S Panditaratne N Verma R Robertson R . Incremental value of CT venography combined with pulmonary CT angiography for the detection of thromboembolic disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenol. (2011) 196:1065–72. 10.2214/AJR.10.4745

71.

Van Der Hulle T Van Es N Den Exter PL Van Es J Mos ICM Douma RA et al Is a normal computed tomography pulmonary angiography safe to rule out acute pulmonary embolism in patients with a likely clinical probability? A patient-level meta-analysis. Thromb Haemostasis. (2017) 117:1622–9. 10.1160/TH17-02-0076

72.

van Beek EJ Brouwers EM Song B Bongaerts AH Oudkerk M . Lung scintigraphy and helical computed tomography for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2001) 7:87–92. 10.1177/107602960100700202

73.

Locker T Goodacre S Sampson F Webster A Sutton AJ . Meta-analysis of plethysmography and rheography in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Emerg Med J. (2006) 23:630–5. 10.1136/emj.2005.033381

74.

Novielli N Sutton AJ Cooper NJ . Meta-analysis of the accuracy of two diagnostic tests used in combination: application to the ddimer test and the wells score for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Value Health. (2013) 16:619–28. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.007

75.

Goodacre S Sampson F Thomas S van Beek E Sutton A . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis. BMC Med Imaging. (2005) 5:1–13. 10.1186/1471-2342-5-6

76.

Deng HY Li G Luo J Wang ZQ Yang XY Lin YD et al MicroRNAs are novel non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers for pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. (2016) 8:3580–7. 10.21037/jtd.2016.12.98

77.

Belzile D Jacquet S Bertoletti L Lacasse Y Lambert C Lega JC et al Outcomes following a negative computed tomography pulmonary angiography according to pulmonary embolism prevalence: a meta-analysis of the management outcome studies. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2018) 16:1107–20. 10.1111/jth.14021

78.

Van Es N Van Der Hulle T Van Es J Den Exter PL Douma RA Goekoop RJ et al Wells rule and d-dimer testing to rule out pulmonary embolism a systematic review and individual-patient data meta- analysis. Ann Intern Med. (2016) 165:253–61. 10.7326/M16-0031

79.

Singh B Mommer SK Erwin PJ Mascarenhas SS Parsaik AK . Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) in pulmonary embolism-revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. (2013) 30:701–6. 10.1136/emermed-2012-201730

80.

Barth BE Waligora G Gaddis GM . Rapid systematic review: age-adjusted D-dimer for ruling out pulmonary embolism. Journal of Emergency Medicine. (2018) 55:586–92. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.07.003

81.

Schols AMR Stakenborg JPG Dinant GJ Willemsen RTA Cals JWL . Point-of-care testing in primary care patients with acute cardiopulmonary symptoms: a systematic review. Fam Pract. (2018) 35:4–12. 10.1093/fampra/cmx066

82.

Mustafa BO Rathbun SW Whitsett TL Raskob GE . Sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. (2002) 162:401–4. 10.1001/archinte.162.4.401

83.

Hess S Frary EC Gerke O Madsen PH . State-of-the-art imaging in pulmonary embolism: ventilation/perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography versus computed tomography angiography—controversies, results, and recommendations from a systematic review. Semin Thromb Hemost. (2016) 42:833–45. 10.1055/s-0036-1593376

84.

Roy PM Colombet I Durieux P Chatellier G Sors H Meyer G . Systematic review and meta-analysis of strategies for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. Br Med J. (2005) 331:259–63. 10.1136/bmj.331.7511.259

85.

Patel P Braun C Patel P Bhatt M Begum H Wiercioch W et al Diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:2516–22. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001409

86.

Goodacre S Sampson FC Sutton AJ Mason S Morris F . Variation in the diagnostic performance of D-dimer for suspected deep vein thrombosis. QJM. (2005) 98:513–27. 10.1093/qjmed/hci085

87.

Siccama RN Janssen KJM Verheijden NAF Oudega R Bax L van Delden JJM et al Systematic review: diagnostic accuracy of clinical decision rules for venous thromboembolism in elderly. Ageing Res Rev. (2011) 10:304–13. 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.005

88.

Pinson AG Becker DM Philbrick JT Parekh JS . Technetium-99m-RBC venography in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity: a systematic review of the literature. J Nucl Med. (1991) 32:2324–8.

89.

Sampson FC Goodacre SW Thomas SM Beek EJR . The accuracy of MRI in diagnosis of suspected deep vein thrombosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. (2007) 17:175–81. 10.1007/s00330-006-0178-5

90.

Brown MD Rowe BH Reeves MJ Bermingham JM Goldhaber SZ . The accuracy of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay D-dimer test in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. (2002) 40:133–44. 10.1067/mem.2002.124755

91.

Kan Y Yuan L Meeks JK Li C Liu W Yang J . The accuracy of V/Q SPECT in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Acta Radiol. (2015) 56:565–72. 10.1177/0284185114533682

92.

Abdalla G Fawzi Matuk R Venugopal V Verde F Magnuson TH Schweitzer MA et al The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance venography in the detection of deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Radiol. (2015) 70:858–71. 10.1016/j.crad.2015.04.007

93.

Zhang C Wang Y Zhao X Liu L Wang C Li Z et al Clinical, imaging features and outcome in internal carotid artery versus middle cerebral artery disease. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0225906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225906

94.

Antonopoulos CN Sfyroeras GS Kakisis JD Moulakakis KG Liapis CD . The role of soluble P selectin in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. (2014) 133:17–24. 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.08.014

95.

Prentice D . 697: three capnography methods for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Crit Care Med. (2014) 42:A1528. 10.1097/01.ccm.0000458194.72927.ef

96.

Fields JM Davis J Girson L Au A Potts J Morgan CJ et al Transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2017) 30:714–723.e4. 10.1016/j.echo.2017.03.004

97.

Niemann T Egelhof T Bongartz G . Transthoracic sonography for the detection of pulmonary embolism—a meta-analysis. Ultraschall in der Medizin. (2009) 30:150–6. 10.1055/s-2008-1027856

98.

Goodacre S Sutton AJ Sampson FC . Meta-analysis: the value of clinical assessment in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. (2005) 143(2):129–39. 10.7326/0003-4819-143-2-200507190-00012

99.

Le Roux PY Robin P Tromeur C Davis A Robert-Ebadi H Carrier M et al Ventilation/perfusion SPECT for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2020) 18:2910–20. 10.1111/jth.15038

100.

Carrier M Le Gal G Cho R Tierney S Rodger M Lee AY . Dose escalation of low molecular weight heparin to manage recurrent venous thromboembolic events despite systemic anticoagulation in cancer patients. J Thromb Haemost. (2009) 7:760–5. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03326.x

101.

van Es N van der Hulle T van Es J den Exter PL Douma RA Goekoop RJ et al PO-07—excluding pulmonary embolism in cancer patients using the wells rule and age-adjusted D-dimer testing: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Thromb Res. (2016) 140:S179. 10.1016/S0049-3848(16)30140-2

102.

Ayaram D Bellolio MF Murad MH Laack TA Sadosty AT Erwin PJ et al Triple rule-out computed tomographic angiography for chest pain: a diagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. (2013) 20:861–71. 10.1111/acem.12210

103.

Carrier M Le Gal G Wells PS Rodger MA . Systematic review: case-fatality rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism and major bleeding events among patients treated for venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med. (2010) 152:578–89. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00008

104.

Di Nisio M Van Sluis GL Bossuyt PMM Büller HR Porreca E Rutjes AWS . Accuracy of diagnostic tests for clinically suspected upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2010) 8:684–92. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03771.x

105.

Al Lawati K Aljazeeri J Bates SM Chan W-S De Wit K . Ability of a single negative ultrasound to rule out deep vein thrombosis in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. (2020) 18:373–80. 10.1111/jth.14650

106.

Leeflang MMG Rutjes AWS Reitsma JB Hooft L Bossuyt PMM . Variation of a test’s sensitivity and specificity with disease prevalence. CMAJ. (2013) 185:E537–544. 10.1503/cmaj.121286

107.

Boyer K Wies J Turkelson CM . Effects of bias on the results of diagnostic studies of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. (2009) 34:1006–13. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.02.018

108.

Fontela PS Pant Pai N Schiller I Dendukuri N Ramsay A Pai M . Quality and reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies in TB, HIV and malaria: evaluation using QUADAS and STARD standards. PLoS One. (2009) 4:e7753. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007753

109.

Bochmann F Johnson Z Azuara-Blanco A . Sample size in studies on diagnostic accuracy in ophthalmology: a literature survey. Br J Ophthalmol. (2007) 91:898–900. 10.1136/bjo.2006.113290

110.

Price CP . Evidence-based laboratory medicine: supporting decision-making. Clin Chem. (2000) 46:1041–50. 10.1093/clinchem/46.8.1041

111.

Price CP Christenson RH . Evaluating new diagnostic technologies: perspectives in the UK and US. Clin Chem. (2008) 54:1421–3. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.108217

112.

Moons KGM . Criteria for scientific evaluation of novel markers: a perspective. Clin Chem. (2010) 56:537–41. 10.1373/clinchem.2009.134155

Summary

Keywords

diagnostic tests, sensitivity and specificity, meta-analysis, venous thromboembolism, venous thrombosis

Citation

Boschetti L, Nilius H, Ten Cate H, Wuillemin WA, Faes L, Bossuyt PM, Bachmann LM and Nagler M (2024) Design-related bias in studies investigating diagnostic tests for venous thromboembolic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1420000. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1420000

Received

19 April 2024

Accepted

18 November 2024

Published

29 November 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Peter Marschang, Azienda Sanitaria dell'Alto Adige ASDAA, Italy

Reviewed by

Larisa Anghel, Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, Romania

Martin Ellis, Meir Medical Center, Israel

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Boschetti, Nilius, Ten Cate, Wuillemin, Faes, Bossuyt, Bachmann and Nagler.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Michael Nagler michael.nagler@insel.ch

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.