Abstract

Objective:

Rivaroxaban and dabigatran are approved to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF). However, the clinical benefits of rivaroxaban and dabigatran in people with high bleeding risk are unclear.

Methods:

A retrospective study was conducted on NVAF patients admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University from May 31, 2016 to May 31, 2019. These patients had a high risk of bleeding and were taking at least one study medication. The aim of the study was to evaluate clinical benefits by comparing the efficacy and safety risks of these two medications

Results:

A total of 1,301 patients with high bleeding risk were enrolled, including 787 patients in the rivaroxaban group and 514 patients in the dabigatran group. Results of the primary efficacy benefit endpoint were obtained from 104 patients (13.21%) in the rivaroxaban group and 81 (15.76%) patients in the dabigatran group [hazard ratio (HR): 0.860; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.637–1.162; P = 0.327], this indicates that there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in preventing stroke and systemic embolism in patients with high bleeding risk NVAF. The principal safety end points were observed in 49 (6.23%) patients in the rivaroxaban group and in 36 (7.00%) patients in the dabigatran group (HR: 0.801 in the rivaroxaban group; 95% CI: 0.512–1.255; P = 0.333), this indicates that there was no a significant difference in reducing fatal bleeding and critical organ bleeding. With respect to secondary efficacy and benefit endpoints, 28 (3.56%) patients in the rivaroxaban group and 26 (5.06%) patients in the dabigatran group died, with an HR of 0.725 (95% CI: 0.425–1.238; P = 0.239); 32 (4.07%) patients in the rivaroxaban group; and 31 (6.03%) patients in the dabigatran group had myocardial infarction (MI), with an HR of 0.668 (95% CI: 0.405–1.102, P = 0.114) in the rivaroxaban group, this indicates that there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in preventing all-cause death and MI.

Conclusions:

In NVAF patients with high bleeding risk, there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in preventing stroke and systemic embolism. There was also no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in reducing fatal and critical organ bleeding.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Chinese Clinical Trials Registry, identifier ChiCTR2100052454.

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a prevalent cardiac arrhythmia characterized by the loss of regular, organized electrical activity in the heart, replaced by rapid and irregular fibrillation waves. It represents a significant disruption in normal cardiac electrical activity (1, 2). The estimated global prevalence was 50 million in 2020 (3, 4). AF is associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of death (5, 6). In meta-analyses, AF is also associated with increased risk of multiple adverse outcomes, including a 2.4-fold risk of stroke (6), 1.5-fold risk of myocardial infarction (MI) (7), and 1.3-fold risk of peripheral artery disease (6). NVAF refers to atrial fibrillation that occurs aside from cases involving mechanical prosthetic heart valves or those typically associated with moderate to severe mitral stenosis caused by rheumatic heart disease (8). For patients with concomitant valvular disease, the use of warfarin for anticoagulation is recommended. For patients with NVAF, professional guidelines suggest oral anticoagulant therapy for those at increased risk of thromboembolism (9, 10). Past use of warfarin has significantly reduced the risk of stroke in patients with AF (11). Furthermore, warfarin treatment has a narrow therapeutic range, interacts with food and other drugs, and requires regular international normalized ratio monitoring and frequent dose adjustments (12, 13). In recent years, rivaroxaban and dabigatran has been approved for stroke prevention in AF in randomized controlled trials, owing to its noninferiority in both efficacy and safety when compared to warfarin (14, 15).

The most worrisome complication of anticoagulation is bleeding, especially for patients with NVAF with high bleeding risk. In 2010, The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the treatment of AF introduced for the first time the HAS-BLED bleeding risk assessment program. Patients with a HAS-BLED score of ≥3 are considered to be at high bleeding risk (16). Many studies have confirmed that being patients with NVAF with high bleeding risk does not necessarily contraindicate the use of anticoagulant medications (17, 18). Moreover, several studies have comparatively analyzed the clinical benefits of rivaroxaban and warfarin (14, 15, 19–21). In clinical practice, there are many populations receiving oral anticoagulant therapy with rivaroxaban and dabigatran. However, there is limited comparative analysis between rivaroxaban and dabigatran, and these studies have not specifically investigated the East Asian population with high bleeding risk. In clinical settings, patients on Asian with AF with multiple complications tend to have high bleeding risk. Clinicians often lack guidance for medication management in this population. This study specifically conducts a comparative analysis of NVAF patients of East Asian with high bleeding risk, comparing the efficacy and safety risks of rivaroxaban and dabigatran. The findings aim to provide hypothesis generation for further studies.

2 Methods

Patients admitted to the Cardiology Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, He Hospital District, and Zhengdong Hospital District from May 31, 2016 to May 31, 2019 were screened through the medical records system. Eleven wards were included (including 2 CCUs) based on the following criteria: (1) Inclusion criteria: (1.1) Diagnosis of AF based on routine electrocardiogram or dynamic electrocardiogram findings; (1.2) Valvular diseases ruled out by echocardiography; (1.3) High risk of bleeding defined as HAS-BLED score ≥3; (1.4) Requiring anticoagulant therapy with rivaroxaban or dabigatran (based on CHADS2-VASc score ≥1); (1.5) Age ≥18 years old. (2) Exclusion criteria: (2.1) Discontinuation of medication without medical advice or failure to adhere to the standard dosage regimen of the study drugs; (2.2) Loss to follow-up during telephone follow-up; (2.3) Switching to other types of oral anticoagulants during the follow-up period.

The study was divided into two groups: the rivaroxaban group and the dabigatran group. (i) Rivaroxaban group, rivaroxaban (Bayer Healthcare Co., LTD., National drug approval J20180077) was used for anticoagulant therapy. The oral dose varied based on the patient's age, weight and creatinine clearance. The standard dosage is 20 mg per day. For patients with low body weight(body mass index less than 18.5), age over 75 years, creatinine clearance between 15 and 49 ml/min or concurrent acute coronary syndrome, adjust the dosage to 15 mg per day. For patients with creatinine clearance between 15 and 49 ml/min and concurrent acute coronary syndrome, adjust the dosage to 10 mg per day, taken once daily at fixed time intervals, with 1 tablet per dose. (ii) Dabigatran group: Anticoagulant therapy was implemented using dabigatran (Boehringer Ingelheim, approval number J20171035, 110 mg × 10 tablets, 150 mg × 10 tablets). The dosage, based bleeding risk, was a fixed oral dose of 110 mg, taken once in the morning and once in the evening, with 1 tablet per dose.

From May 31, 2016 to May 31, 2019, a total of 1,423 NVAF patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled. Each patient was followed up for 730 days from the start of medication, except in the case of all-cause mortality. After excluding those who were lost to follow-up, did not adhere to medication as per the physician's instructions, or switched to other types of anticoagulants, a total of 1,301 eligible NVAF patients with high bleeding risk remained. Among them, there were 787 cases in the rivaroxaban group, 514 cases in the dabigatran group.

2.1 Study endpoints

This retrospective study's primary efficacy endpoint was defined as a composite endpoint including stroke and systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was defined as a composite endpoint including fatal or critical organ bleeding. and the secondary efficacy benefit end point was defined as all-cause death and MI. Specifically: Fatal bleeding: Defined as transfusion of whole blood or concentrated red blood cells ≥2 units, or causing a decrease in hemoglobin of ≥2 g/dl. Critical organ bleeding: Defined as bleeding occurring in critical organ sites such as intracranial, spinal, ocular, pericardial, articular, retroperitoneal, or compartment syndrome.

2.2 Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 statistical software. Normally distributed continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), and between-group comparisons were made using the t-test. Skewed distributed continuous data were represented as [M (P25, P75)], and between-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Comparison of rates was performed using the chi-square test. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare two groups of ordinal data. Hazard ratios (HR), confidence intervals (CIs), and P-values were calculated using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival analysis was conducted using the log-rank test. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

The main clinical characteristics of the patients included in the analysis are shown in Table 1. To compare baseline data between the two groups, appropriate statistical methods were employed. Since most clinical characteristics of the two groups were similar.

Table 1

| Characteristic | Rivaroxaban (n = 787) |

Dabigatran (n = 514) |

T-test or chi-square test |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 71.23 ± 7.73 | 70.91 ± 8.05 | 0.723 | 0.470 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 461 (58.58) | 311 (60.51) | 0.480 | 0.489 |

| f CHADS2-VASc score (n%) | ||||

| 1 | 105 (13.34) | 71 (13.81) | ||

| 2 | 170 (21.60) | 112 (21.79) | ||

| 3 | 203 (25.79) | 129 (25.10) | ||

| 4 | 188 (23.89) | 104 (20.23) | ||

| 5 | 73 (9.28) | 58 (11.28) | 0.331 | 0.740 |

| 6 | 38 (4.83) | 29 (5.64) | ||

| 7 | 10 (1.27) | 8 (1.56) | ||

| 8 | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.39) | ||

| 9 | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.19) | ||

| g HAS-BLED score (n%) | ||||

| 3 | 690 (87.67) | 442 (86.00) | ||

| 4 | 86 (10.93) | 62 (12.06) | ||

| 5 | 10 (1.27) | 10 (1.95) | 0.903 | 0.367 |

| 6 | 1 (0.13) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Current baseline characteristics, Mean ± SD | ||||

| d EF | 56.68 ± 9.95 | 56.20 ± 10.19 | 0.836 | 0.403 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 162.33 ± 30.63 | 161.00 ± 25.10 | 0.812 | 0.417 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 93.03 ± 18.69 | 91.89 ± 15.44 | 1.146 | 0.252 |

| Hemoglobin | 132.59 ± 18.49 | 132.02 ± 17.06 | 0.698 | 0.485 |

| INR | 1.53 ± 6.58 | 1.37 ± 0.80 | 0.547 | 0.584 |

| M(P25,P75) | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase | 20.00 (13.00, 32.00) | 13.00 (13.00, 28.00) | 1.972 | 0.049 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 21.00 (17.00, 29.00) | 20.00 (17.00, 25.00) | 3.493 | 0.001* |

| Direct bilirubin | 5.50 (3.90, 8.00) | 6.20 (4.70, 8.23) | 3.802 | 0.001* |

| Indirect bilirubin | 5.70 (3.70, 8.50) | 7.30 (5.10, 10.30) | 7.403 | 0.001* |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 74.00 (61.00, 91.00) | 71.00 (59.00, 82.00) | 3.503 | 0.001* |

| Creatinine | 76.00 (65.00, 92.00) | 89.30 (75.58, 105.00) | 9.002 | 0.001* |

| c BNP | 1,274.00 (639.70, 2,637.24) | 1,185.35 (721.91, 2,305.23) | 0.723 | 0.470 |

| Medical history (n%) | ||||

| Heart failure | 245 (31.13) | 140 (27.24) | 2.262 | 1.133 |

| Diabetes | 153 (19.44) | 109 (21.21) | 0.602 | 0.438 |

| Hypertension | 583 (74.08) | 357 (69.46) | 3.315 | 0.069 |

| Stroke | 138 (17.53) | 100 (19.46) | 0.767 | 0.381 |

| Thromboembolisma | 21 (2.7) | 13 (2.8) | 0.029 | 0.864 |

| e TIA | 35 (4.45) | 20 (3.89) | 0.238 | 0.626 |

| Vascular diseaseb | 37 (4.70) | 237 (5.25) | 0.202 | 0.653 |

| History of nonsteroidal drug use | 397 (50.44) | 2,146 (47.86) | 0.831 | 0.362 |

| Smoking | 245 (31.13) | 158 (30.74) | 0.022 | 0.881 |

| Alcohol | 379 (48.16) | 275 (53.50) | 3.552 | 0.059 |

Baseline characteristics of the study population (N = 1,246).

Thromboembolism includes pulmonary embolism, organ embolism, and lower limb embolism.

Vascular disease includes peripheral artery disease, MI, and complex aortic plaques.

BNP, brain natriuretic peptide.

EF, ejection fraction.

TIA, transient ischemic attack.

CHADS2-VASc, congestive, heart, failure, hypertension, age ≥75 (doubled), diabetes mellitus, stroke (doubled)-vascular disease, age 65–74 and sex category(female).

HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, stroke, bleeding, labile INRs, elderly, drugs and alcohol.

*Significant value.

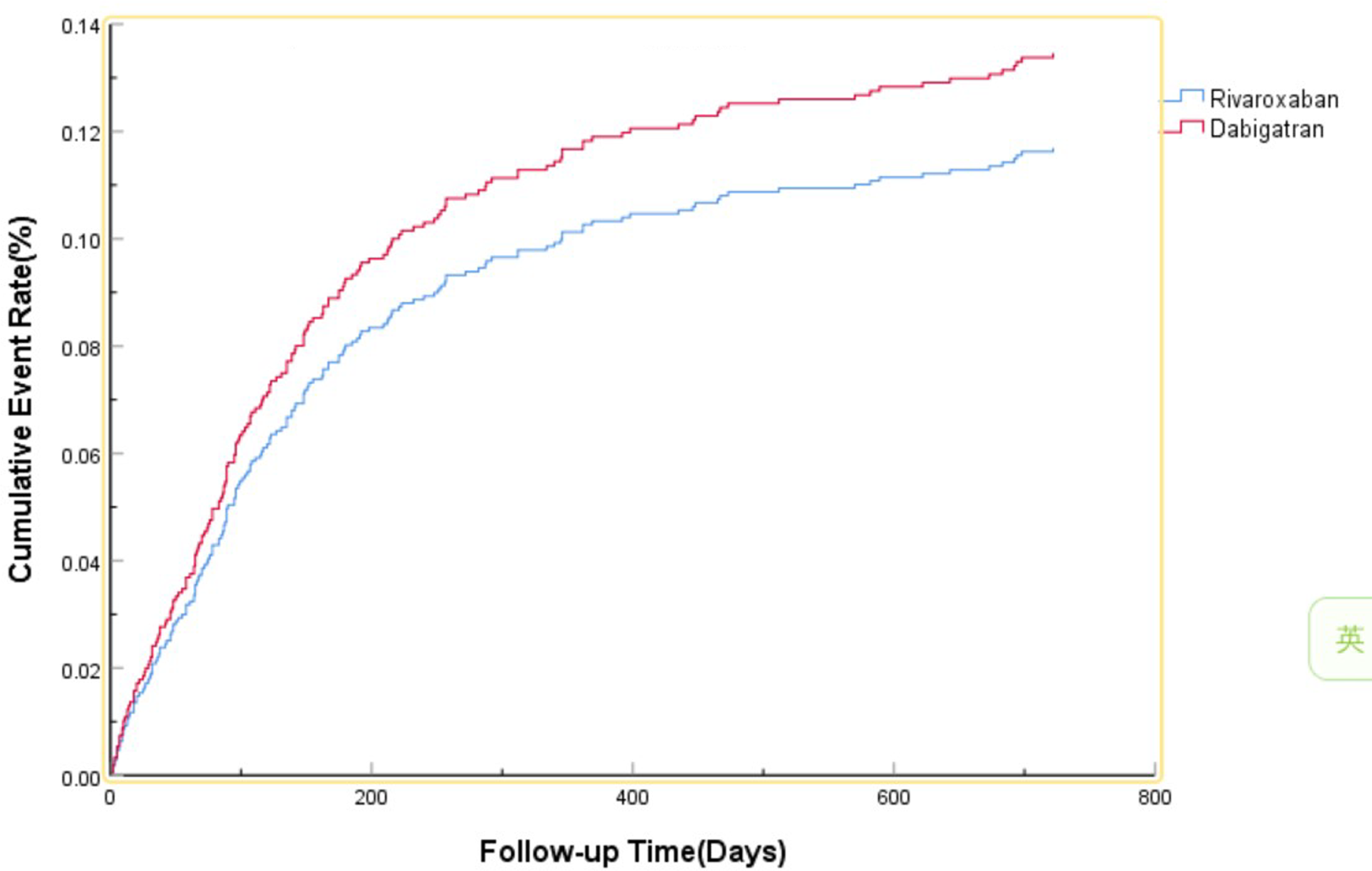

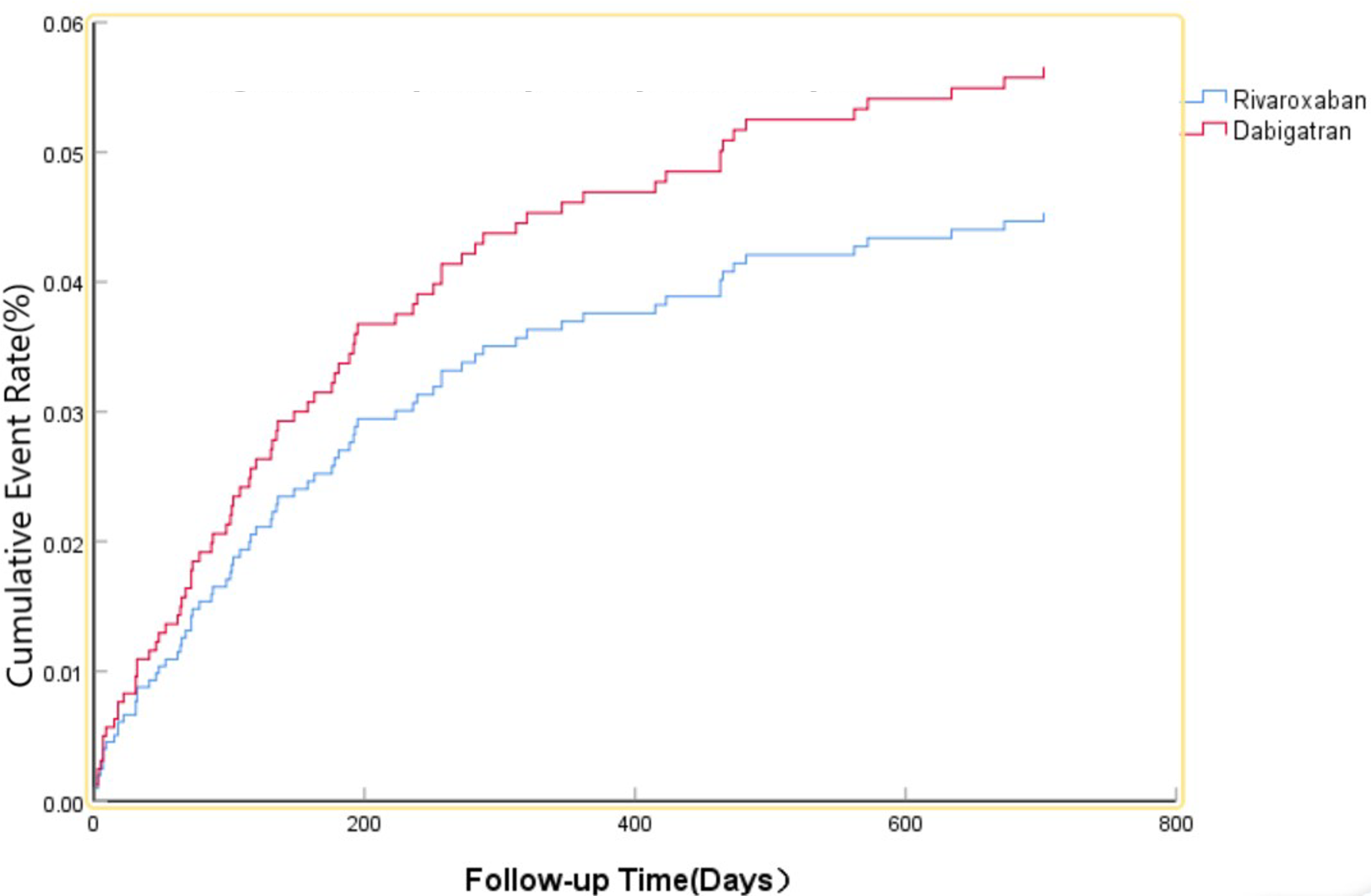

The efficacy benefit and safety end points in this study are shown in Table 2. The primary efficacy endpoint occurred in 81 cases (15.76%) in the dabigatran group and 104 cases (13.21%) in the rivaroxaban group, with an HR of 0.860 (95% CI: 0.637–1.162; P = 0.327) for the rivaroxaban group. The principal safety end points occurred in 36 cases (7.00%) in the dabigatran group and 49 cases (6.23%) in the rivaroxaban group, with an HR of 0.801 (95% CI: 0.512–1.255; P = 0.333) for the rivaroxaban group. This indicates that there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in preventing stroke and systemic embolism in patients with high bleeding risk NVAF, as shown in Figure 1, nor was there a significant difference in reducing fatal bleeding and critical organ bleeding, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 2

| Clinical outcome | All (N = 1,301, n%) | Rivaroxaban (n = 787) | Dabigatran (n = 514) | Multivariable adjustment OR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The primary efficacy endpoint | 185 (14.22) | 104 (13.21) | 81 (15.76) | 0.860 (0.637–1.162) | 0.327 |

| Strokea | 98 (7.53) | 57 (7.24) | 41 (7.98) | 0.909 (0.608–1.135) | 0.642 |

| MIb | 63 (4.84) | 32 (4.07) | 31 (6.03) | 0.668 (0.405–1.102) | 0.114 |

| PTEc | 17 (1.31) | 10 (1.27) | 7 (1.36) | 0.988 (0.375–2.606) | 0.981 |

| Lower-extremity thrombosis | 29 (2.23) | 16 (2.03) | 13 (2.52) | 1.005 (0.490–2.149) | 0.990 |

| All-cause death | 64 (4.92) | 28 (3.56) | 26 (5.06) | 0.725 (0.425–1.238) | 0.239 |

| Primary safety endpoint | 85 (6.53) | 49 (6.23) | 36 (7.00) | 0.801 (0.512–1.255) | 0.333 |

| Fatal bleedingd | 39 (3.00) | 21 (2.67) | 18 (3.50) | 0.729 (0.382–1.393) | 0.339 |

| Critical organ bleedinge | 47 (3.61) | 28 (3.56) | 19 (3.70) | 0.886 (0.492–0.1.594) | 0.685 |

| ICHf | 30 (2.31) | 18 (2.29) | 12 (2.33) | 0.872 (0.412–1.845) | 0.720 |

Comparison of end point events in the rivaroxaban and dabigatran groups.

Both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

Myocardial infarction.

Pulmonary thromboembolism.

Whole blood transfusion or erythrocyte concentration ≥2 units or hemoglobin reduction ≥2 g/dl.

Bleeding from any of the following anatomical sites: intracranial, spinal, eye, pericardium, joint, retroperitoneal, or muscular compartment syndrome.

Intracranial hemorrhage.

Figure 1

The primary efficacy benefit end point.

Figure 2

The primary safety risk end point.

Secondary efficacy and benefit endpoints: there were 26 cases (5.06%) of all-cause death in the dabigatran group and 28 cases (3.56%) in the rivaroxaban group, with an HR of 0.725 (95% CI: 0.425–1.238; P = 0.239) for the rivaroxaban group. There were 31 cases (6.03%) of MI in the dabigatran group and 32 cases (4.07%) in the rivaroxaban group, with an HR of 0.668 (95% CI: 0.405–1.102; P = 0.114) for the rivaroxaban group. This indicates that there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in preventing all-cause death and MI.

4 Discussion

We compared fixed-dose dabigatran and rivaroxaban for patients with NVAF and a risk of stroke. In terms of primary efficacy endpoints, there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in treating stroke and systemic embolism. In the RELY study (14), the 150 mg dose of dabigatran was superior to warfarin in treating stroke or non-central embolism, and the 110 mg dose was superior to warfarin in terms of major bleeding. In the ROCKET-AF study (15), rivaroxaban was non-inferior to warfarin in preventing stroke and systemic embolism. In the ARISTOPHANES study (20), both dabigatran and rivaroxaban were associated with lower rates of stroke and systemic embolism compared to warfarin, but there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban. In our study, dabigatran and rivaroxaban also showed no significant difference, indicating similar therapeutic effects in populations with high bleeding risk. This is also broadly similar to the results of studies involving catheter ablation in patients with AF (22–25). The most concerning complication of anticoagulant therapy is the risk of bleeding, especially fatal and critical organ bleeding. In previous studies (14, 15, 20), it has been demonstrated that Rates of intracranial bleeding and critical organ bleeding were higher with warfarin than with either dabigatran or rivaroxaban. Dabigatran has a lower incidence of major bleeding compared to rivaroxaban (20). However, in this study, there was no significant difference observed between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in reducing fatal and critical organ bleeding. One possible explanation is that the majority of the population included in this study had a high risk of bleeding, prompting clinicians to administer medication with greater caution, often opting for lower doses compared to previous studies. Additionally, the unique genetic makeup of the Asian population may also play a role (26–28), which warrants further evidence-based medical research for validation. The final possible explanation is that the little number of events in the population may necessitate further studies with a large sample size.

The primary secondary efficacy endpoint of all-cause death and MI also showed no significant difference between the two groups. However, a phenomenon was observed during the Phase III clinical trials of dabigatran, where a slight increase in the incidence of MI was noted among patients taking the medication (14). Guidelines also recommend against prioritizing dabigatran for patients at higher risk of coronary artery disease or MI (29). This aspect requires further research for confirmation.

The study population comprised hospitalized patients receiving treatment at the hospital, and all data were derived from the hospital's case system and patient follow-up processes. Compared to previous real-world studies, both rivaroxaban and dabigatran are equally effective, with dabigatran showing an advantage in reducing major bleeding (30–32). However, in this study, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of reducing major bleeding. This could be related to the fact that all participants in this study had high bleeding risk, differences in drug dosing, and possibly the number of participants included. This closely mirrors real-world clinical treatment scenarios, providing valuable insights for actual clinical medication practices.

This retrospective observational study has several limitations. Firstly, due to the inherent limitations of retrospective studies, only statistical associations can be inferred, not causal relationships. Secondly, our data were obtained from hospitalized patients in the Department of Cardiology at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, so the conclusions may be most representative for the Chinese population in East Asia. Finally, given the large number of statistical tests, especially interaction tests, we cannot rule out the possibility of type I errors.

5 Conclusion

Overall, In NVAF patients with high bleeding risk, there was no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in preventing stroke and systemic embolism. There was also no significant difference between dabigatran and rivaroxaban in reducing fatal and critical organ bleeding.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PL: Funding acquisition, Software, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Science and Technology Plan of Henan Province (No. 182102310160), Medical Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province (2018020118).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Fei He of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University for their help, and we thank the patients who participated in this study and their families.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Baman JR Passman RS . Atrial fibrillation. JAMA. (2021) 325(21):2218. 10.1001/jama.2020.23700

2.

Brundel B Ai X Hills MT Kuipers MF Lip GYH De Groot NMS . Atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2022) 8(1):21. 10.1038/s41572-022-00347-9

3.

Colilla S Crow A Petkun W Singer DE Simon T Liu X . Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol. (2013) 112(8):1142–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.063

4.

Mou L Norby FL Chen LY O’neal WT Lewis TT Loehr LR et al Lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation by race and socioeconomic Status: ARIC study (atherosclerosis risk in communities). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2018) 11(7):e006350. 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006350

5.

Emdin CA Wong CX Hsiao AJ Altman DG Peters SA Woodward M et al Atrial fibrillation as risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in women compared with men: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br Med J. (2016) 532:h7013. 10.1136/bmj.h7013

6.

Odutayo A Wong CX Hsiao AJ Hopewell S Altman DG Emdin CA . Atrial fibrillation and risks of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J. (2016) 354:i4482. 10.1136/bmj.i4482

7.

Frederiksen TC Dahm CC Preis SR Lin H Trinquart L Benjamin EJ et al The bidirectional association between atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2023) 20(9):631–44. 10.1038/s41569-023-00857-3

8.

Steffel J Verhamme P Potpara TS Albaladejo P Antz M Desteghe L et al The 2018 European heart rhythm association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39(16):1330–93. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy136

9.

Corrigendum to: 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association of cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(5):546–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa945

10.

Joglar JA Chung MK Armbruster AL Benjamin EJ Chyou JY Cronin EM et al 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2024) 149(1):e1–156. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

11.

Hart RG Pearce LA Aguilar MI . Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. (2007) 146(12):857–67. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007

12.

De Caterina R Husted S Wallentin L Andreotti F Arnesen H Bachmann F et al Vitamin K antagonists in heart disease: current status and perspectives (section III). position paper of the ESC working group on thrombosis–task force on anticoagulants in heart disease. Thromb Haemost. (2013) 110(6):1087–107. 10.1160/TH13-06-0443

13.

Ageno W Gallus AS Wittkowsky A Crowther M Hylek EM Palareti G . Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. (2012) 141(2 Suppl):e44S–88. 10.1378/chest.11-2292

14.

Connolly SJ Ezekowitz MD Yusuf S Eikelboom J Oldgren J Parekh A et al Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2009) 361(12):1139–51. 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561

15.

Patel MR Mahaffey KW Garg J Pan G Singer DE Hacke W et al Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365(10):883–91. 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638

16.

Camm AJ Kirchhof P Lip GY Schotten U Savelieva I Ernst S et al Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. (2010) 31(19):2369–429. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278

17.

Okumura K Yamashita T Akao M Atarashi H Ikeda T Koretsune Y et al Oral anticoagulants in very elderly nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients with high bleeding risks: ANAFIE registry. JACC Asia. (2022) 2(6):720–33. 10.1016/j.jacasi.2022.07.008

18.

Lee KH Chen YF Yeh WY Yeh JT Yang TH Chou CY et al Optimal stroke preventive strategy for patients aged 80 years or older with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review with traditional and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing. (2022) 51(12):1–10.afac292. 10.1093/ageing/afac292. Erratum in: Age Ageing. (2023) 52(1):afad002. 10.1093/ageing/afad002

19.

Ruff CT Giugliano RP Braunwald E Hoffman EB Deenadayalu N Ezekowitz MD et al Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. (2014) 383(9921):955–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

20.

Lip GYH Keshishian A Li X Hamilton M Masseria C Gupta K et al Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Stroke. (2018) 49(12):2933–44. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.020232

21.

Lee SR Choi EK Kwon S Han KD Jung JH Cha MJ et al Effectiveness and safety of contemporary oral anticoagulants among Asians with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke. (2019) 50(8):2245–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025536

22.

Calkins H Willems S Gerstenfeld EP Verma A Schilling R Hohnloser SH et al Uninterrupted dabigatran versus warfarin for ablation in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376(17):1627–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701005

23.

Aryal MR Ukaigwe A Pandit A Karmacharya P Pradhan R Mainali NR et al Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin or dabigatran in patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. (2014) 114(4):577–82. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.038

24.

Lavalle C Pierucci N Mariani MV Piro A Borrelli A Grimaldi M et al Italian registry in the setting of atrial fibrillation ablation with rivaroxaban—IRIS. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. (2024) 116. 10.23736/S2724-5683.24.06546-3

25.

Dong Z Hou X Du X He L Dong J Ma C . Effectiveness and safety of DOACs in atrial fibrillation patients undergoing catheter ablation: results from the China atrial fibrillation (China-AF) registry. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2022) 28:10760296221123306. 10.1177/10760296221123306

26.

Yoon CH Park YK Kim SJ Lee MJ Ryoo S Kim GM et al Eligibility and preference of new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: comparison between patients with versus without stroke. Stroke. (2014) 45(10):2983–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005599

27.

Shen AY Yao JF Brar SS Jorgensen MB Chen W . Racial/ethnic differences in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2007) 50(4):309–15. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.098

28.

Gaikwad T Ghosh K Shetty S . VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genotype distribution in Asian countries. Thromb Res. (2014) 134(3):537–44. 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.05.028

29.

Kirchhof P Benussi S Kotecha D Ahlsson A Atar D Casadei B et al 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37(38):2893–962. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210

30.

Bai Y Deng H Shantsila A Lip GY . Rivaroxaban versus dabigatran or warfarin in real-world studies of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. (2017) 48(4):970–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016275

31.

Mitsuntisuk P Nathisuwan S Junpanichjaroen A Wongcharoen W Phrommintikul A Wattanaruengchai P et al Real-world comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants vs. Warfarin in a developing country. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 109(5):1282–92. 10.1002/cpt.2090

32.

Menichelli D Del Sole F Di Rocco A Farcomeni A Vestri A Violi F et al Real-world safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 605 771 patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. (2021) 7(Fi1):f11–9. 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvab002

Summary

Keywords

rivaroxaban, dabigatran, nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, high bleeding risk, clinical benefits

Citation

Liu P (2024) A comparative study of the clinical benefits of rivaroxaban and dabigatran in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with high bleeding risk. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11:1445970. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1445970

Received

08 June 2024

Accepted

26 August 2024

Published

17 September 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Danilo Menichelli, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Reviewed by

Carlo Lavalle, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Francesco Del Sole, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Penghui Liu 528529000@qq.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.