Abstract

Introduction:

The potential role of post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) quantitative flow ratio (QFR) and ultrasonic flow ratio (UFR) in predicting adverse outcomes in patients with successful rotational atherectomy (RA) and stent placement remains to be defined.

Methods:

A total of 68 patients with highly calcific lesions, who underwent both QFR and UFR measurements after PCI with both RA and stenting, were enrolled. The major adverse coronary events (MACE) of 62 patients who completed 12-month follow-up were analyzed. The clinical characteristics of 9 patients with MACE and 53 non-MACE patients were compared. The predictors of MACE were analyzed using LASSO regression combined with Cox regression analyses.

Results:

Patients with MACE had more lipid-rich and mixed plaques, less stent expansion and symmetry index, and lower post-PCI QFR and UFR compared with non-MACE patients. Cox regression analyses found that patients with lower post-PCI QFR (P < 0.05) or lower post-PCI UFR (P < 0.01) had a significantly higher risk of MACE. Lasso regression was performed to select the most important predictors, and the subsequent Cox multivariate regression analyses showed that post-PCI UFR, mixed plaque, and stent expansion index were independent predictors of MACE (all P < 0.05). Multivariate linear regression analyses also found that changes in UFR (P < 0.05) and post-PCI UFR at minimal stent area (P < 0.01) were significantly associated with post-PCI UFR results.

Conclusion:

Lower value of post-PCI UFR is an independent predictor of 12-month MACE after PCI with RA and stent implantation in patients with highly calcified lesions.

1 Introduction

The prevalence of coronary artery calcification is increasing with accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors and population aging (1). Coronary artery calcification remains a significant challenge to successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as it is more difficult to deliver stent and achieve optimal stent expansion. Rotational atherectomy (RA) was invented more than 30 years ago and was initially used to reduce plaque burden during the era of plain old balloon angioplasty and bare-metal stent (2). Then, RA was almost abandoned because it failed to improve major adverse coronary events (MACE) and target lesion revascularization during long-term follow-up (3). In the era of second-generation drug-eluting stents, adjunct RA has been used as a plaque modification technique in severely calcified lesions to facilitate balloon dilation and stent placement (4, 5). Clinical trials demonstrated that the use of adjunct high-speed RA yielded higher procedural success rate of PCI than standard balloon pre-dilatation in treating patients with heavily calcified lesions (6–8). However, it is controversial whether RA could decrease the development of MACE during follow-up, and the incidence rate of 12-month MACE following RA and stent placement can be more than 15% in average or even higher than 20% in some studies as reported (8–10). The mechanism of high MACE incidence with RA-assisted PCI is still not fully understood, but it may be due to the fact that sicker and at high-risk patients are treated with RA. The present study aimed to investigate potential predictors of 12-month MACE in patients who underwent successful RA and stent placement.

Coronary angiography (CAG) has limited ability in evaluating the results of PCI. Post-PCI physiology studies, i.e., the measurement of fractional flow reserve (FFR), have shown that around 20% of treated vessels had suboptimal physiology after angiographically successful PCI, which highlights the importance of coronary artery physiology assessments (11–13). Importantly, high post-PCI FFR values were associated with a reduced rate of MACE and a better clinical outcome after stent placement compared with low post-PCI FFR (14). FFR has been under-utilized because of the additional time and costs associated with the use of a pressure wire (15). Recently, quantitative flow ratio (QFR) which can be quickly computed based on CAG provides an accurate and useful alternative to FFR (16). Similar to the value of FFR, studies showed that lower values of QFR after successful stent placement also predict the development of MACE (17). However, the predictive value of post-PCI FFR or QFR in patients with RA remains elusive. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) image study is not required but highly recommended for anatomic and physiologic assessments before and after RA and PCI especially in highly calcified lesions (18, 19). Ultrasonic flow ratio (UFR) is a novel IVUS-derived modality which estimates FFR without pressure wire and adenosine. UFR not only provides an accurate anatomic assessment of stent dimensions but also evaluates coronary artery physiology (20, 21). Studies have shown that UFR is highly concordance with FFR in assessment of coronary artery stenosis and can integrate intravascular imaging and physiological assessment in clinical practice (22). However, the prognostic value of either QFR or UFR in patients who underwent RA and stent placement was unknown. The present study was designed to test the performance of post-PCI QFR and post-PCI UFR in predicting the development of 12-month MACE after successful RA and stent placement in patients with highly calcified plaques.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

This was a single-center, retrospective, and observational study. A total of 68 patients with coronary artery atherosclerotic and calcific lesions, who underwent both QFR and UFR measurements immediately after successful PCI including both RA and stent placement at Yanan Hospital Affiliated to Kunming Medical University, were enrolled in this study from January 2019 to January 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients were greater than 18 years old; (2) diagnosed atherosclerotic coronary artery disease with severely calcified de novo coronary lesions using both CAG and IVUS studies; (3) underwent successful PCI with both RA and stent placement; (4) and QFR and UFR were successfully measured after RA and stenting. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) chronic occlusive lesions that guidewires cannot pass through; (2) in-stent restenosis or graft stenosis; (3) without stent implantation following RA; (4) use of drug-coated balloon. All data, including demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging studies, procedural features, and follow-up of outcomes, were collected from the electronic medical records. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the institutional review board, and written informed consent was waived by the institutional review board because of the retrospective design of the study.

2.2 RA and stent placement procedures

All PCI procedures were performed by experienced and credentialed interventional cardiologists in our catheterization laboratories. All patients received pretreatment with aspirin and clopidogrel or ticagrelor. During the procedure, patients received unfractionated heparin to achieve an activated clotting time of 250–300 s. The decisions to perform RA and stent placement were made by the operator after CAG and IVUS imaging studies. RA procedures were performed based on standard recommendations using the RotablatorTM rotational atherectomy system (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) (18, 19). The burr size we selected was 1.25, 1.50, 1.75, or 2.0 mm. During RA, the burr catheter was irrigated with a cocktail flush fluid to avoid slow flow phenomenon. Completion of RA was defined as full debulking of the target lesion without premature termination of RA before proceeding to subsequent treatment. After RA, patients received a single or multiple drug-eluting stents (XIENCE PRIME stent system, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA; or Endeavor Resolute stent system, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Then, post-dilatation with a noncompliant balloon was applied to achieve optimal angiographic and ultrasonic results with minimal residual stenosis. After stent implantation, dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel or ticagrelor were continued for at least 12 months.

2.3 Measurement of QFR and UFR

Pre- and post-PCI QFR was computed offline by an independent analyst through a commercial software package (AngioPlus, Pulse Medical Imaging Technology, Shanghai, China) based on baseline CAG and repeated angiography performed immediately after RA and stent placement, respectively. Details of the computational method and underlying principle of QFR were reported in previous studies (23). IVUS imaging studies were performed using a commercially available system (iLab, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). The IVUS catheter was advanced 10 mm distal to the lesion, and images were recorded while pulling back the catheter to the coronary ostium. Coronary lesions were classified as fibrous, lipid-rich, and mixed plaques, and ring and nodular calcification was identified based on IVUS images. Lesion length, plaque burden, minimal lumen area, stenosis at minimal lumen area, and calcium score were calculated. Pre- and post-PCI UFR values were calculated by other analyst blinded to QFR results using a commercial software package (IvusPlus, Pulse Medical Imaging Technology, Shanghai, China) based on baseline and post-PCI IVUS, respectively.

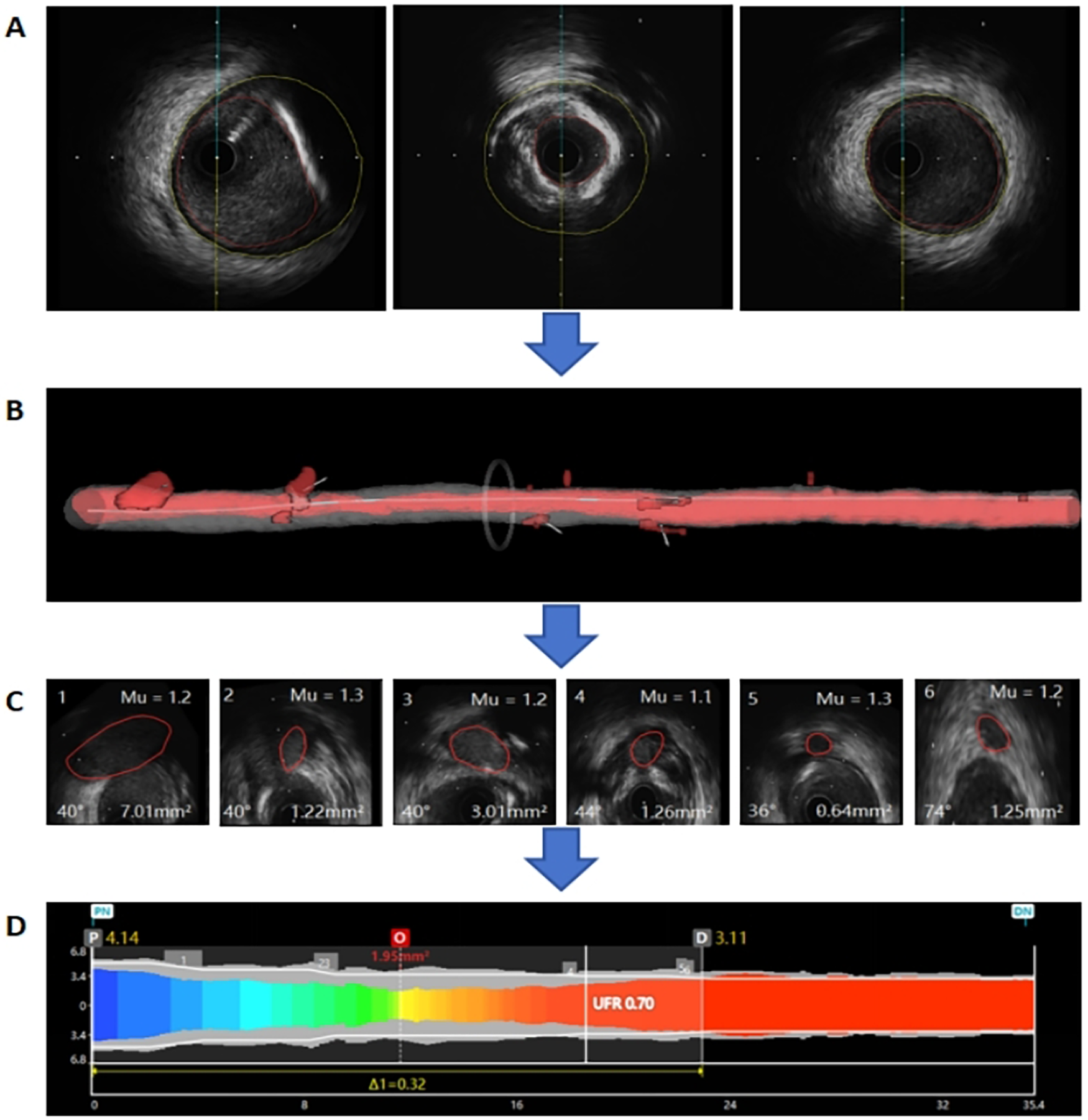

For UFR computation, firstly, lumen contours and external elastic lamina (EEL) were automatically delineated using a deep learning model on IVUS pullback images. Manual editing was allowed to correct any errors if the automatic delineated contours did not follow the lumen and EEL borders (Figure 1A). Then, a three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the coronary lumen was created (Figure 1B). Additionally, the software automatically reconstructed and quantified the ostia of side branches perpendicular to side branches centerlines. According to the bifurcation fractal laws, the reference lumen area was derived (Figure 1C). Then, the reference lumen area was multiplied by a fixed flow rate of 0.35 m/s to estimate the downstream perfusion flow. Finally, with a validated computational FFR method based on fluid dynamic equations, the pressure drop at each cross-section along the pullback was calculated and the UFR pullback was obtained (Figure 1D).

Figure 1

Example of the ultrasonic flow ratio (UFR) computation. (A) Lumen contours and external elastic lamina (EEL) were automatically delineated using a deep learning model. (B) The three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the coronary lumen was created. (C) The reference lumen area was derived. (D) The UFR pullback was obtained.

2.4 Follow-up of adverse outcomes

Follow-up was performed at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after the procedure. The development of MACE within 12 months after PCI was recorded. MACE outcomes were defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, stent thrombosis, and target vessel revascularization. The diagnosis of the MACE components was in accordance with the proposed definitions of 2014 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular Endpoint Events in Clinical Trials (24).

2.5 Statistical analyses

All continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard error, and categorical variables were presented as frequency. Unpaired t test or nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons of continuous variables, and categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. To analyze predictors of MACE, we first utilized univariate Cox proportional hazard regression to evaluate the performance of post-PCI QFR and post-PCI UFR in predicting 12-month MACE. Harrell's C index was calculated and compared to evaluate the predictive performance of post-PCI QFR and post-PCI UFR. Then, we performed LASSO regression analysis to shrink potential risk factors and to preliminarily select the strongest predictors of MACE. Subsequent univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed on the strongest risk factors selected by the LASSO regression analysis. univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed on independent predictors of post-PCI QFR and UFR. All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) or SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

3 Result

3.1 Patient characteristics

From January 2019 to January 2023, 68 patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and had both QFR and UFR measured immediately after successfully RA and stent implantation. With 6 patients lost to follow-up in12 months, the adverse outcomes of 62 patients were analyzed. 9 patients developed MACE within a follow-up of 12 months. We compared the baseline features of MACE and non-MACE patients and found that the demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, medical history, and clinical manifestation were comparable between MACE and non-MACE patients (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variables | MACE (n = 9) | Non-MACE (n = 53) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics parameters | |||

| Age, years | 69.7 ± 8.0 | 66.1 ± 8.6 | 0.24 |

| Males, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 31 (58.5) | 0.30 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 23.9 ± 2.2 | 0.72 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 6 (66.7) | 38 (71.7) | 0.76 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6 (66.7) | 26 (49.1) | 0.54 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 6 (66.7) | 30 (56.6) | 0.84 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 31 (58.5) | 0.30 |

| Medical history | |||

| CHF, n (%) | 5 (55.6) | 19 (35.8) | 0.45 |

| CKD, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.7) | 0.46 |

| CVA, n (%) | 2 (22.2) | 11 (20.7) | 0.92 |

| Prior MI, n (%) | 1 (11.1) | 7 (13.2) | 0.86 |

| PCI, n (%) | 1 (11.1) | 16 (30.2) | 0.43 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| SIHD, n (%) | 4 (44.4) | 19 (35.9) | 0.62 |

| UA, n (%) | 4 (44.4) | 30 (56.6) | 0.50 |

| NSTEMI, n (%) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (5.7) | 0.54 |

| STEMI, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 0.68 |

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Data are expressed as mean ± SE or number of cases (frequency). BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVA, cerebrovascular disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MI, myocardial infarction; SIHD, stable ischemic heart disease; UA, unstable angina; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

3.2 Angiographic, ultrasonic, and procedural characteristics

The results of baseline coronary angiographic analysis are shown in Table 2. Target-vessel characteristics, which included their distribution and severity of stenosis, were comparable between MACE and non-MACE patients (Table 2). The IVUS-measured minimal luminal area, lesion length, severity of stenosis, and plaque burden are similar between the two groups (Table 2). Lipid-rich plaque and mixed plaque occurred more frequently in MACE patients (both P < 0.01). Whereas the frequencies of ring or nodular calcification and the IVUS calcium score were similar between MACE and non-MACE patients (Table 2). Similar number of burrs per target vessel, maximal size of burrs, and size of stents were used between groups (Table 3). Patients with MACE needed two or more stents per target vessel, while nearly half of non-MACE patients received only one stent (Table 3). In addition, patients with MACE had less mean stent expansion, higher stent eccentricity index, and lower stent symmetry index (all P < 0.01) (Table 3). Lastly, the procedure-related complications were comparable between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 2

| Variables | MACE (n = 9) | Non-MACE (n = 53) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAG parameters | |||

| Target vessel distribution | |||

| LAD, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 39 (73.6) | 0.79 |

| LCX, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.3) | 0.29 |

| RCA, n (%) | 2 (22.2) | 8 (15.1) | 0.59 |

| Target vessel stenosis (%) | 90.0 ± 3.0 | 90.0 ± 8.0 | 0.35 |

| Triple vessel disease, n (%) | 8 (88.9) | 42 (79.2) | 0.50 |

| Bifurcation lesion, n (%) | 1 (11.1) | 12 (22.6) | 0.73 |

| LMCA lesion, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 23 (43.4) | 0.12 |

| IVUS parameters | |||

| Minimal lumen area, mm2 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 0.91 |

| Reference lumen area, mm2 | 11.5 ± 3.3 | 11.8 ± 3.2 | 0.78 |

| Plaque burden at MLA, % | 84.5 ± 10.0 | 78.1 ± 10.0 | 0.12 |

| Stenosis at MLA, % | 72.3 ± 14.2 | 70.7 ± 19.4 | 0.67 |

| IVUS total lesion length, mm | 63.6 ± 11.1 | 55.2 ± 19.2 | 0.21 |

| Fibrous plaque, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 35 (66.0) | 0.76 |

| Lipid-rich plaque, n (%) | 9 (100.0) | 22 (41.5) | <0.01 |

| Mixed plaque, n (%) | 8 (88.9) | 16 (30.2) | <0.01 |

| Ring calcification, n (%) | 8 (88.9) | 40 (75.5) | 0.65 |

| Nodular calcification, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 21 (39.6) | 0.72 |

| Calcified lesion length, mm | 8.5 ± 6.4 | 6.7 ± 5.3 | 0.35 |

| Calcified lesion CSA, mm2 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.42 |

| IVUS calcium score | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 0.27 |

Angiographic and intravascular ultrasonic characteristics of lesions.

Data are expressed as mean ± SE or number of cases (frequency). CAG, coronary angiography; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MLA, minimal lumen area; CSA, cross-sectional area.

Table 3

| Variables | MACE (n = 9) | Non-MACE (n = 53) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| RA parameters | |||

| No. of burrs per vessel | 0.75 | ||

| 1, n (%) | 8 (88.9) | 45 (84.9) | |

| 2, n (%) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (15.1) | |

| Maximal burr size, mm | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.13 |

| Highest speed (×104 rpm) | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 16.0 ± 3.0 | 0.07 |

| Stent parameters | |||

| No. of stents pre vessel | 0.02 | ||

| 1, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (45.3) | |

| 2, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 21 (39.6) | |

| 3, n (%) | 2 (22.2) | 8 (15.1) | |

| Total stent length, mm | 25.0 ± 12.0 | 32.0 ± 17.0 | 0.25 |

| Minimal stent diameter, mm | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.80 |

| Maximal stent diameter, mm | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.18 |

| Minimal stent area, mm2 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 0.72 |

| Mean stent expansion, % | 59.7 ± 12.6 | 74.0 ± 13.1 | <0.01 |

| Conventional stent expansion, % | 46.9 ± 6.1 | 50.2 ± 9.6 | 0.33 |

| Stent eccentricity index | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | <0.01 |

| Stent symmetry index | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | <0.01 |

| Complications | |||

| Hematoma at the puncture site, n (%) | 2 (22.2) | 13 (24.5) | 0.88 |

| Dissection, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 7 (13.2) | 0.30 |

| Hypotension, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 31 (58.5) | 0.47 |

| Bradycardia, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 15 (28.3) | 0.76 |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.4) | 0.77 |

| QFR and UFR parameters | |||

| Pre-PCI QFR | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 0.52 ± 0.23 | 0.72 |

| Post-PCI QFR | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.03 | <0.05 |

| Pre-PCI UFR | 0.51 ± 0.16 | 0.58 ± 0.18 | 0.27 |

| Post- PCI UFR | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Pre-PCI UFR at MLA | 0.72 ± 0.27 | 0.74 ± 0.27 | 0.50 |

| Post-PCI UFR at MSA | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.46 |

| Pre-PCI UFR at calcified ring | 0.78 ± 0.22 | 0.78 ± 0.17 | 0.50 |

| Post-PCI UFR at calcified ring | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 0.54 |

Procedural characteristics of rotational atherectomy and stent placement.

Data are expressed as mean ± SE or number of cases (frequency). RA, rotational atherectomy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; QFR, quantitative flow ratio; UFR, ultrasonic flow ratio; MLA, minimal lumen area; MSA, minimal stent area; Stent expansion index, MSA/Reference lumen area of distal stent; Conventional stent expansion index, MSA/Average of proximal and distal reference lumen area.

3.3 Pre- and post-PCI quantitative and ultrasonic flow ratio

The pre-PCI QFR and UFR, which were of the target vessel, at the minimal lumen area, and at calcified rings, were comparable between MACE and non-MACE patients (Table 3). Interestingly, the post-PCI QFR (0.91 ± 0.03 vs. 0.94 ± 0.03, P < 0.05) and post-PCI UFR (0.85 ± 0.03 vs. 0.90 ± 0.03, P < 0.01) measured immediately after successful RA with stent implantation were significantly lower in the MACE patients (Table 3).

3.4 Post-PCI QFR or UFR predicts 12-month MACE

Cox regression analyses found that patients with lower post-PCI QFR (B: −20.13, HR: 1.80 × 10−9, 95% CI: 3.80 × 10−18–0.86, P < 0.05) or lower post-PCI UFR (B: −42.30, HR: 4.24 × 10−19, 95% CI: 1.08 × 10−30–1.66 × 10−7, P < 0.01) had a significantly higher risk of MACE (Table 4). The accuracy of post-PCI UFR and post-PCI QFR was similar in predicting 12-month MACE (post-PCI UFR C-index: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.69–0.94 vs. post-PCI QFR C-index: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.56–0.91, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S1). Lasso regression was performed to select the most important predictor variables, and the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses revealed that post-PCI UFR (P < 0.01), mixed plaque (P < 0.05), and stent expansion index (P < 0.01) were predictors of MACE in post-PCI patients (Table 5).

Table 4

| Variables | B | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-PCI QFR | −20.13 | 1.80 × 10−9 | 3.80 × 10−18–0.86 | 0.04 |

| Post-PCI UFR | −42.30 | 4.24 × 10−19 | 1.08 × 10−30–1.66 × 10−7 | <0.01 |

Predictive value of post-PCI UFR and QFR on MACE.

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; QFR, quantitative flow ratio; UFR, ultrasonic flow ratio.

Table 5

| Variables | Univariate Cox regression | Multivariate Cox regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Post-PCI UFR | 4.24 × 10−19 | 1.08 × 10−30–1.66 × 10−7 | <0.01 | 3.12 × 10−14 | 7.86 × 10−25–0.01 | 0.01 |

| Mixed plaque | 14.91 | 1.86–119.40 | 0.01 | 10.82 | 1.30–89.99 | 0.03 |

| Stent expansion index | 0.93 | 0.88–0.97 | <0.01 | 0.94 | 0.89–1.00 | 0.04 |

Predictors of MACE following PCI.

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; QFR, quantitative flow ratio; UFR, ultrasonic flow ratio.

3.5 Factors associated with post-PCI QFR and post-PCI UFR

Considering that post-PCI QFR and UFR are valuable in predicting MACE, we performed linear regression analyses to identify factors associated with these two alternative measurements of FFR. Univariate linear regression analyses revealed that distal stent length and total stent length are associated with post-PCI QFR (both P < 0.01), however, multivariate linear regression analyses failed to confirm them as independent predictors (Table 6). Univariate linear regression analyses found that changes in UFR, post-PCI UFR at minimal stent area, total lesion length, and number of stents used for each vessel were associated with post-UFR (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01), and multivariate linear regression analyses confirmed that changes in UFR (P < 0.05) and post-PCI UFR at minimal stent area (P < 0.01) were independent predictors of post-PCI UFR (Table 7).

Table 6

| Variables | Univariate linear regression | Multivariate linear regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | P | B | SE | β | P | |

| Distal stent length | 2 × 10−3 | 4.82 × 10−6 | <0.01 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | 0.32 | 0.09 |

| Total stent length | 1 × 10−3 | 2.72 × 10−6 | <0.01 | 4.41 × 10−6 | 3.58 × 10−6 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

Factors associated with the post-PCI QFR value.

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; QFR, quantitative flow ratio.

Table 7

| Variables | Univariate linear regression | Multivariate linear regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | P | B | SE | β | P | |

| Changes in UFR | −0.93 | 0.03 | <0.01 | −0.89 | 0.04 | −0.92 | <0.01 |

| Post-PCI UFR at MSA | 0.32 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Total lesion length | −1 × 10−3 | 2.49 × 10−6 | 0.01 | −2.65 × 10−5 | 1.10 × 10−6 | −0.01 | 0.81 |

| No. of stents pre vessel | −0.02 | 0.01 | <0.01 | −1 × 10−3 | 3 × 10−3 | −0.03 | 0.66 |

Factors associated with the post-PCI UFR value.

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; UFR, ultrasonic flow ratio; MSA, minimal stent area.

4 Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the potential role of QFR and UFR, computing immediately after successful PCI with both RA and implantation, in the prediction of adverse events within 12 months. To minimize confounding factors, we only selected patients with highly calcified lesions and undergoing successful RA and revascularization. Moreover, QFR and UFR were computed offline by two independent analysts blinded to the study. The main findings are as follows. First, patients who developed 12-month MACE had more lipid-rich and mixed plaques, less stent expansion and symmetry index, and lower post-PCI QFR and UFR compared with non-MACE patients. Second, post-PCI QFR and post-PCI UFR had excellent and similar prognostic value for MACE in univariate Cox analysis, while LASSO regression and multivariate Cox analysis identified that only post-PCI UFR, mixed plaque, and stent expansion index were independent predictors of 12-month adverse events. Third, changes in UFR and post-PCI UFR at minimal stent area independently influenced post-PCI UFR measurements.

Post-PCI FFR and QFR have been used to predict adverse events in patients underwent stent implantation, however, to the best of our knowledge the present study is the first to investigate the prognostic value of post-PCI UFR in patients underwent both RA and stent implantation. FFR as the prototype and gold standard measurement of coronary flow reserve has been utilized to assess the physiology of coronary artery disease, which is superior to CAG that only anatomically assesses stenotic lesions (25). Post-PCI FFR detects residual coronary artery disease burden after revascularization by measuring flow reduction, and the outcomes of FFR-guided PCI are superior to angiography-guided management of coronary artery disease (26, 27). Importantly, post-PCI FFR serves as a reliable independent predictor of target vessel failure and adverse events (28–30). Unfortunately, post-PCI FFR is not routinely computed in most catheterization labs in daily clinical practice partially due to extra costs associated with pressure wires, prolonged procedure duration, and potential adverse effects of adenosine administration (15). QFR and UFR are adenosine-independent pressure indexes of coronary artery stenosis and have been developed as substitutes for FFR.

4.1 Clinical and procedural insights into QFR

QFR is a pressure wire-free assessment of coronary physiology based on CAG without the need of epicardial vasodilation by adenosine administration. QFR has a high correlation and agreement with FFR (31) and is used to optimize PCI of multivessel disease complying with the current guidelines (32). Post-PCI QFR was associated with the development of MACE (33), and lower values of QFR after successful revascularization by stent placement predicted subsequent adverse events (17). Moreover, a previous study showed that post-PCI QFR had a high predictive value for target lesion failure during a 3-year follow-up after RA and stent placement in patients with heavily calcified lesions (34). This finding is similar to the current study which showed that post-PCI QFR was an excellent predictor of 12-month MACE after RA and stent implantation in univariate Cox regression analysis. However, post-PCI QFR as a variable was excluded by LASSO regression which we performed to shrink potential risk factors and to preliminarily select the strongest predictors of MACE. It is possible that post-PCI QFR was highly correlated with post-PCI UFR, but the prognostic value of post-PCI QFR might be not as strong as post-PCI UFR (Supplementary Table S1), so it was abandoned in LASSO regression analysis. If RA and stent placement were not guided by IVUS or UFR was not available, post-PCI QFR would still be a valuable predictor of adverse events after RA. QFR has demonstrated good inter-core laboratory reproducibility in assessing the physiological significance of coronary stenosis (35). However, operator, angiographic quality, and the coronary artery stenosis severity and imaging system factors can influence its accuracy (36). Therefore, adherence to standardized imaging protocols and operator training is essential to ensure accuracy and consistency across different operators and systems.

4.2 Clinical and procedural insights into UFR

UFR is a novel FFR alternative modality that can be fast computed based on IVUS imagines. IVUS has been widely used to optimize PCI especially in patients with complex and severely calcified lesions. Clinical expert consensus documents recommend using IVUS before, during, and after RA to improve procedural success and safety (18, 19, 37), and the use of IVUS for complex and calcified lesions was associated with decreased risk of target vessel revascularization and mortality (20, 38). Therefore, UFR is readily available in most cases when RA is performed to modify calcified lesions. It has been proved that UFR has a strong correlation with FFR and can be used to accurately assess hemodynamic significance of coronary artery stenosis (21), and the diagnostic performance of UFR is non-inferior to QFR (22). In previous studies, UFR were confirmed to have a better performance in left main coronary artery diseases, multivessel diseases, bifurcation lesion diseases (21, 22, 39, 40). A previous study showed that lesion-specific UFR was an independent predictor of three-year MACE after PCI with stent placement (40), but UFR was not yet used to predict adverse outcome of calcific lesions following RA. The present study provides compelling evidence that post-PCI UFR is an independent predictor of 12-month MACE in addition to mixed plaque and stent expansion index. Combination of intravascular image study and coronary physiological assessment is recommended in PCI to enable optimal revascularization. UFR is a modality that combines morphological anatomical features and functional assessment without using extra devices. Post-PCI UFR values may be used to define the endpoint of PCI in order to optimize the results of PCI in the future. In the present study, lower post-PCI UFR was associated with longer total lesion length and more stents used in each target vessel. This finding suggests that diffuse long coronary artery lesions may require more efforts to achieve optimal revascularization as this type of lesions were notoriously associated with higher incidence of MACE and target vessel revascularization (41, 42). UFR can be readily integrated into routine clinical practice as it utilizes standard IVUS imaging, requiring no additional equipment, contrast agents, or hyperemic agents.

Compared with other diagnostic modalities, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and its based optical flow ratio (OFR), which is another novel FFR alternative modality, UFR provides distinct advantages. Firstly, UFR enables a one-step, streamlined assessment of coronary physiology and lesion morphology without requiring additional equipment, thereby enhancing procedural efficiency and reducing costs. Secondly, a meta-analysis demonstrated that UFR has superior sensitivity and specificity in identifying hemodynamically significant coronary stenosis compared to OFR (43). Probably, because IVUS has better tissue penetration, higher chances of covering the entire lesions and wider clinical penetration than OCT (21). Future comparative studies examining UFR and OFR within the same clinical settings could further elucidate their respective advantages and limitations. Near-infrared spectroscopy-intravascular ultrasound (NIRS-IVUS), a newer but not widely available modality, integrates two imaging technologies and is primarily used for identifying high-risk plaques (44). While NIRS-IVUS excels at characterizing plaque composition and structural assessment, UFR offers additional benefits by delivering a streamlined physiological assessment of coronary stenosis without requiring specialized dual-modality equipment. As emphasized in current guidelines for coronary artery revascularization (45), integrating multiple diagnostic tools and clinical judgment is essential for optimal PCI outcomes.

4.3 Clinical application of UFR and QFR

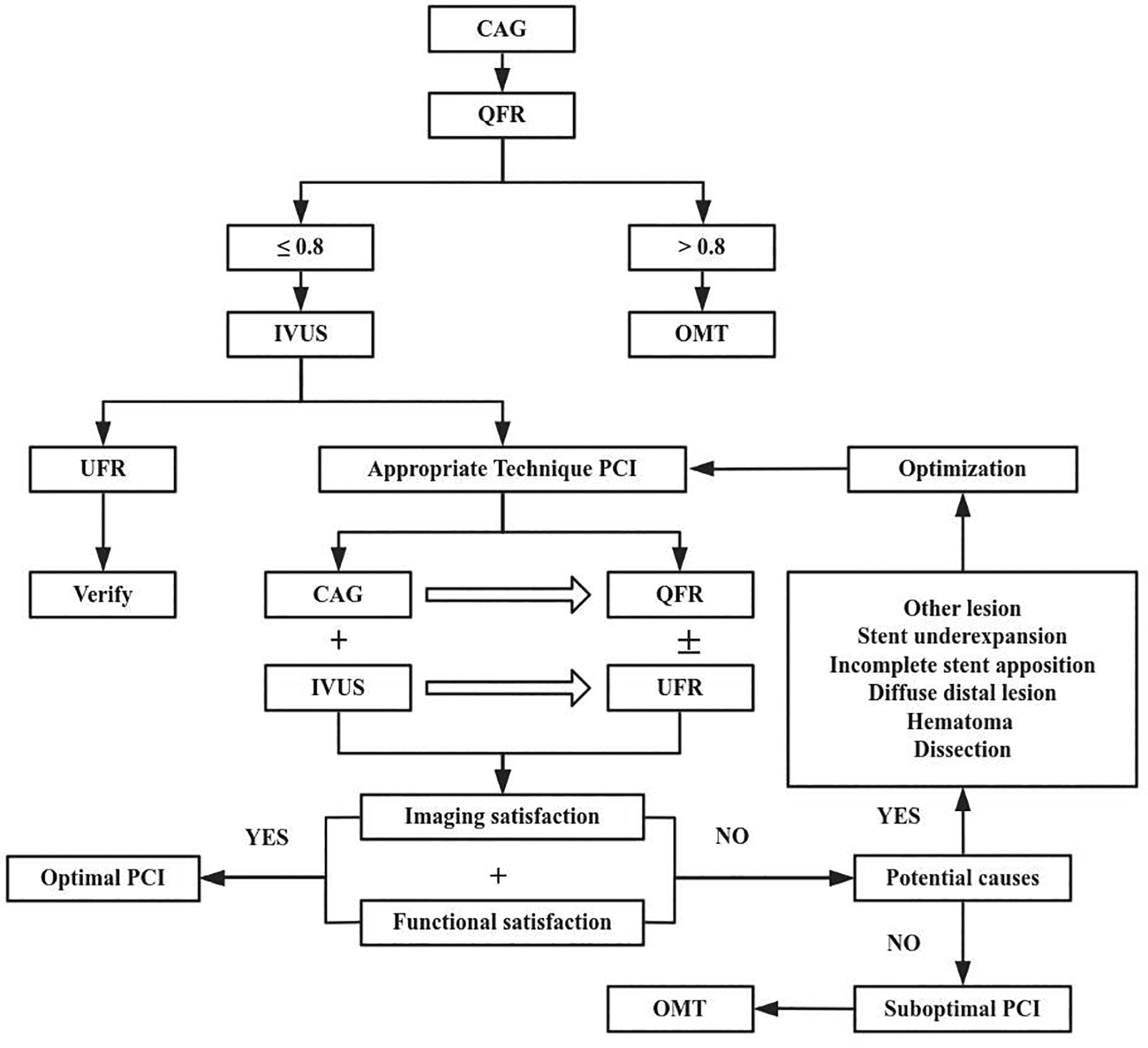

In practice, UFR could be complementary to QFR (Figure 2). QFR is well suited for diagnostic procedures, whereas the UFR supports complex PCI optimization. Although UFR based on IVUS with OptiCross catheters provides key physiological insights, OptiCross catheters crossing lesions in severe stenosis cases may be challenging before procedure. Although in-procedure QFR has been validated as feasible and safe with high diagnostic accuracy, in patients with complex coronary anatomy angiographic projections without vessel overlapping or significant foreshortening might be difficult to obtain. Therefore, in order to guiding optimal PCI to imaging satisfaction and functional satisfaction, we can combine QFR with UFR to assess lesion-specific ischemia but should be complemented by anatomical imaging tools, such as IVUS to evaluate plaque morphology and vessel structure. Additionally, patient-specific factors must guide decision-making to ensure tailored treatment strategies.

Figure 2

Process of optimal PCI with quantitative flow ratio (QFR) and ultrasonic flow ratio (UFR). CAG, coronary angiography; IVUS, Intravascular ultrasound; OMT, Optimal medical therapy.

RA was invented more than three decades ago, and the use of RA has waxed and waned a few times over the years (4). RA has been used to facilitate PCI and improve procedural success rates in the era of drug-eluting stents (46), while it is always questionable whether the use of RA can benefit long-term outcomes. The use of IVUS increases procedural success rate and the safety of RA (47, 48), but it is still unknow whether IVUS can improve long-term outcome after RA. It is challenging to compare the outcomes between RA combined with stenting vs. stenting alone because stent placement without RA could be impossible in certain complex and highly calcified plaques. However, it should be feasible to investigate whether the use of IVUS parameters or specifically UFR as a potential endpoint to guide revascularization can improve long-term outcome after PCI with RA.

To sum up, IVUS combined with CAG has been used to evaluate the indications and effect of RA to optimize PCI of the calcific lesions complying with the current guidelines. QFR and UFR, which are pressure wire-free assessments of coronary physiology based on CAG and IVUS, could do one-stop evaluation of structure and physiology of coronary artery lesions without extra facility. As well as, QFR and UFR may predict adverse outcome following RA. It's convenient to facilitate PCI and favorable to improve prognosis for patients with less expense. Whether both could additionally provide an alternative optimal algorithm for complex PCI in the light of the study deserves further study in the future (Figure 2).

5 Limitation

This study's limitations include its single-centre, retrospective design, relatively small sample size and short follow-up period, which inherently introduces potential selection bias. Coronary artery disease is multiple-etiology and chronic disease, so longer-term studies are necessary to assess the sustained efficacy and safety of the intervention, while the 12-month follow-up provides valuable insights into early outcomes. Future research with extended follow-up periods will be critical to better understand the long-term benefits and potential limitations of the approach. Then, despite the analysis being conducted by automatic artificial intelligence or two experienced operators, individual variability is inevitable in the process of TIMI frame or IVUS frame counting, thus introduces error to some degree, especially in those cases with relatively poor quality of image. Additionally, we would like to point out that the majority of our patients had acute coronary syndrome (ACS) instead of stable ischemic heart disease. The use of RA in patients with ACS is still controversial as the current revascularization guidelines and expert consensus documents only recommend applying RA to treat calcified lesions in patients with chronic coronary syndromes (18, 19, 37, 45, 49). Recent studies showed that RA is feasible in patients with ACS, resulting in comparable procedural outcomes but a higher long-term MACE rate compared to the use of RA in patients with chronic coronary syndromes. This should be considered when comparing the rate of MACE in the present study with the results of future studies.

6 Conclusion

Lower value of post-PCI UFR is an independent predictor of adverse events after PCI with both RA and stent implantation in patients with highly calcified coronary lesions. Post-PCI QFR may also have prognostic value if UFR is not available.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Name: Yan'an Hospital of Kunming City Ethical Committee. Affiliation: Yan'an Hospital of Kunming City. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QJ: Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. QC: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YS: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. PG: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. XG: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. QX: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Funds of Kunming Cardiovascular Interventional Imaging Institute [grant numbers 2023-SW-01]; the Funds of the China Scholarship Council [grant numbers 202108535042]; the Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Program Project-Biomedical Special Project [grant numbers 202102AA310003-25]. The funding source had no role in the design of the study and did not participate in study execution, analysis or interpretation of the data, or the decision to submit the results for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1418587/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Onnis C Virmani R Kawai K Nardi V Lerman A Cademartiri F et al Coronary artery calcification: current concepts and clinical implications. Circulation. (2024) 149(3):251–66. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065657

2.

Di Mario C Tomberli B Mattesini A . Resurrection of a new old technique. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11(11):e007421. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007421

3.

Dill T Dietz U Hamm CW Küchler R Rupprecht HJ Haude M et al A randomized comparison of balloon angioplasty versus rotational atherectomy in complex coronary lesions (COBRA study). Eur Heart J. (2000) 21(21):1759–66. 10.1053/euhj.2000.2242

4.

Serra A Jiménez M . Rotational atherectomy and the myth of Sisyphus. EuroIntervention. (2020) 16(4):e269–72. 10.4244/EIJV16I4A45

5.

Eftychiou C Barmby DS Wilson SJ Ubaid S Markwick AJ Makri L et al Cardiovascular outcomes following rotational atherectomy: a UK multicentre experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 88(4):546–53. 10.1002/ccd.26587

6.

Abdel-Wahab M Toelg R Byrne RA Geist V El-Mawardy M Allali A et al High-Speed rotational atherectomy versus modified balloons prior to drug-eluting stent implantation in severely calcified coronary lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11(10):e007415. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007415

7.

Mankerious N Richardt G Allali A Geist V Kastrati A El-Mawardy M et al Lower revascularization rates after high-speed rotational atherectomy compared to modified balloons in calcified coronary lesions: 5-year outcomes of the randomized PREPARE-CALC trial. Clin Res Cardiol. (2024) 113(7):1051–9. 10.1007/s00392-024-02434-1

8.

Abdelaziz A Elsayed H Hamdaalah A Atta K Mechi A Kadhim H et al Safety and feasibility of rotational atherectomy (RA) versus conventional stenting in patients with chronic total occlusion (CTO) lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2024) 24(1):4. 10.1186/s12872-023-03673-2

9.

Okamoto N Ueda H Bhatheja S Vengrenyuk Y Aquino M Rabiei S et al Procedural and one-year outcomes of patients treated with orbital and rotational atherectomy with mechanistic insights from optical coherence tomography. EuroIntervention. (2019) 14(17):1760–7. 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-01060

10.

Okai I Dohi T Okazaki S Jujo K Nakashima M Otsuki H et al Clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes of rotational atherectomy-J2T multicenter registry. Circ J. (2018) 82(2):369–75. 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0668

11.

Patel MR Jeremias A Maehara A Matsumura M Zhang Z Schneider J et al 1-Year Outcomes of blinded physiological assessment of residual ischemia after successful PCI: dEFINE PCI trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15(1):52–61. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.09.042

12.

Lee JM Koo BK . Clinical implications of physiologic assessment after stenting: practical tool beyond simple digits. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(3):e010592. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.010592

13.

Agarwal SK Kasula S Hacioglu Y Ahmed Z Uretsky BF Hakeem A . Utilizing post-intervention fractional flow reserve to optimize acute results and the relationship to long-term outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9(10):1022–31. 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.01.046

14.

Andersen BK Ding D Mogensen LJH Tu S Holm NR Westra J et al Predictive value of post-percutaneous coronary intervention fractional flow reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Q Care Clin Outcomes. (2023) 9(2):99–108. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac053

15.

GT G Johnson NP Wijns W Toth B Achim A Fournier S et al Revascularization decisions in patients with chronic coronary syndromes: results of the second international survey on interventional strategy (ISIS-2). Int J Cardiol. (2021) 336:38–44. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.05.005

16.

Mehta OH Hay M Lim RY Ihdayhid AR Michail M Zhang JM et al Comparison of diagnostic performance between quantitative flow ratio, non-hyperemic pressure indices and fractional flow reserve. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. (2020) 10(3):442–52. 10.21037/cdt-20-179

17.

Biscaglia S Tebaldi M Brugaletta S Cerrato E Erriquez A Passarini G et al Prognostic value of QFR measured immediately after successful stent implantation: the international multicenter prospective HAWKEYE study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2019) 12(20):2079–88. 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.06.003

18.

Sharma SK Tomey MI Teirstein PS Kini AS Reitman AB Lee AC et al North American expert review of rotational atherectomy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2019) 12(5):e007448. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007448

19.

Barbato E Carrie D Dardas P Fajadet J Gaul G Haude M et al European Expert consensus on rotational atherectomy. EuroIntervention. (2015) 11(1):30–6. 10.4244/EIJV11I1A6

20.

Hannan EL Zhong Y Reddy P Jacobs AK Ling FSK Iii K et al Percutaneous coronary intervention with and without intravascular ultrasound for patients with Complex lesions: utilization, mortality, and target vessel revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15(6):e011687. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011687

21.

Yu W Tanigaki T Ding D Wu P Du H Ling L et al Accuracy of intravascular ultrasound-based fractional flow reserve in identifying hemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(2):e009840. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.009840

22.

Yang C Sui YG Shen JY Guan CD Yu W Tu SX et al Diagnostic performance of ultrasonic flow ratio versus quantitative flow ratio for assessment of coronary stenosis. Int J Cardiol. (2024) 400:131765. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131765

23.

Xu B Tu S Qiao S Qu X Chen Y Yang J et al Diagnostic accuracy of angiography-based quantitative flow ratio measurements for online assessment of coronary stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 70(25):3077–87. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.035

24.

Hicks KA Tcheng JE Bozkurt B Chaitman BR Cutlip DE Farb A et al 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical data standards (writing committee to develop cardiovascular endpoints data standards). Circulation. (2015) 132(4):302–61. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.018

25.

Masdjedi K Tanaka N Van Belle E Porouchani S Linke A Woitek FJ et al Vessel fractional flow reserve (vFFR) for the assessment of stenosis severity: the FAST II study. EuroIntervention. (2022) 17(18):1498–505. 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00471

26.

Lee JM Kim HK Park KH Choo EH Kim CJ Lee SH et al Fractional flow reserve versus angiography-guided strategy in acute myocardial infarction with multivessel disease: a randomized trial. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(6):473–84. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac763

27.

Enezate T Omran J Al-Dadah AS Alpert M White CJ Abu-Fadel M et al Fractional flow reserve versus angiography guided percutaneous coronary intervention: an updated systematic review. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 92(1):18–27. 10.1002/ccd.27302

28.

Lee JM Hwang D Choi KH Rhee TM Park J Kim HY et al Prognostic implications of relative increase and final fractional flow reserve in patients with stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11(20):2099–109. 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.031

29.

Johnson NP Tóth GG Lai D Zhu H Açar G Agostoni P et al Prognostic value of fractional flow reserve: linking physiologic severity to clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64(16):1641–54. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.973

30.

Hwang D Koo BK Zhang J Park J Yang S Kim M et al Prognostic implications of fractional flow reserve after coronary stenting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5(9):e2232842. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.32842

31.

Hwang D Choi KH Lee JM Mejía-Rentería H Kim J Park J et al Diagnostic agreement of quantitative flow ratio with fractional flow reserve and instantaneous wave-free ratio. J Am Heart Assoc. (2019) 8(8):e011605. 10.1161/JAHA.118.011605

32.

Vrints C Andreotti F Koskinas KC Rossello X Adamo M Ainslie J et al 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(36):3415–537. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae177

33.

Erbay A Penzel L Abdelwahed YS Klotsche J Heuberger A Schatz AS et al Prognostic impact of pancoronary quantitative flow ratio assessment in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(12):e010698. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.010698

34.

You W Zhou Y Wu Z Meng P Pan D Yin D et al Post-PCI quantitative flow ratio predicts 3-year outcome after rotational atherectomy in patients with heavily calcified lesions. Clin Cardiol. (2022) 45(5):558–66. 10.1002/clc.23816

35.

Chang Y Chen L Westra J Sun Z Guan C Zhang Y et al Reproducibility of quantitative flow ratio: an inter-core laboratory variability study. Cardiol J. (2020) 27(3):230–7. 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0105

36.

Westra J Sejr-Hansen M Koltowski L Mejía-Rentería H Tu S Kochman J et al Reproducibility of quantitative flow ratio: the QREP study. EuroIntervention. (2022) 17(15):1252–9. 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00425

37.

Sakakura K Ito Y Shibata Y Okamura A Kashima Y Nakamura S et al Clinical expert consensus document on rotational atherectomy from the Japanese association of cardiovascular intervention and therapeutics: update 2023. Cardiovasc Intervention Ther. (2023) 38(2):141–62. 10.1007/s12928-022-00906-7

38.

Wongpraparut N Bakoh P Anusonadisai K Wongsawangkit N Tresukosol D Chotinaiwattarakul C et al Intravascular imaging guidance reduce 1-year MACE in patients undergoing rotablator atherectomy-assisted drug-eluting stent implantation. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:768313. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.768313

39.

Sui Y Yang M Xu Y Wu N Qian J . Diagnostic performance of intravascular ultrasound-based fractional flow reserve versus angiography-based quantitative flow ratio measurements for evaluating left main coronary artery stenosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 99(Suppl 1):1403–9. 10.1002/ccd.30078

40.

Seike F Mintz GS Matsumura M Ali ZA Liu M Jeremias A et al Impact of intravascular ultrasound-derived lesion-specific virtual fractional flow reserve predicts 3-year outcomes of untreated nonculprit lesions: the PROSPECT study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15(11):851–60. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011198

41.

Baranauskas A Peace A Kibarskis A Shannon J Abraitis V Bajoras V et al FFR Result post PCI is suboptimal in long diffuse coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. (2016) 12(12):1473–80. 10.4244/EIJ-D-15-00514

42.

Oh PC Han SH . Diffuse long coronary artery disease is still an obstacle for percutaneous coronary intervention in the second-generation drug-eluting stent era?Korean Circ J. (2019) 49(8):721–3. 10.4070/kcj.2019.0150

43.

Takahashi T Shin D Kuno T Lee JM Latib A Fearon WF et al Diagnostic performance of fractional flow reserve derived from coronary angiography, intravascular ultrasound, and optical coherence tomography; a meta-analysis. J Cardiol. (2022) 80(1):1–8. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2022.02.015

44.

Kuku KO Singh M Ozaki Y Dan K Chezar-Azerrad C Waksman R et al Near-Infrared spectroscopy intravascular ultrasound imaging: state of the art. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:107. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00107

45.

Lawton JS Tamis-Holland JE Bangalore S Bates ER Beckie TM Bischoff JM et al 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2022) 145(3):e4–e17. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001039

46.

Bouisset F Barbato E Reczuch K Dobrzycki S Meyer-Gessner M Bressollette E et al Clinical outcomes of PCI with rotational atherectomy: the European multicentre Euro4C registry. EuroIntervention. (2020) 16(4):e305–12. 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-01129

47.

Hu G Qi X Li B Ge T Li X Liu Z et al A single-center study using IVUS to guide rotational atherectomy for chronic renal disease’s calcified coronary artery. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2023) 16:1085–93. 10.2147/JMDH.S405174

48.

Sakakura K Yamamoto K Taniguchi Y Tsurumaki Y Momomura SI Fujita H . Intravascular ultrasound enhances the safety of rotational atherectomy. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. (2018) 19(3 Pt A):286–91. 10.1016/j.carrev.2017.09.012

49.

Iannaccone M Piazza F Boccuzzi GG D'Ascenzo F Latib A Pennacchi M et al ROTational AThErectomy in acute coronary syndrome: early and midterm outcomes from a multicentre registry. EuroIntervention. (2016) 12(12):1457–64. 10.4244/EIJ-D-15-00485

Summary

Keywords

rotational atherectomy, calcific coronary lesion, quantitative flow ratio, ultrasonic flow ratio, major adverse coronary events

Citation

Zhao T, Jin Q, Zhang X, He J, He G, Chen Q, Sun Y, Gan P, Zhang J, Guang X and Xue Q (2025) Ultrasonic flow ratio measured immediately after successful rotational atherectomy with stent implantation predicts major adverse cardiovascular events. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1418587. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1418587

Received

17 May 2024

Accepted

21 April 2025

Published

07 May 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Carlo Palombo, University of Pisa, Italy

Reviewed by

Dunpeng Cai, University of Missouri, United States

Amit Hooda, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhao, Jin, Zhang, He, He, Chen, Sun, Gan, Zhang, Guang and Xue.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Qiang Xue xueqiang3513@126.com Xuefeng Guang gxfkmyanan@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.