- 1Department of Cardiology, Shanghai East Hospital, Shanghai, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of General Medicine, Beicai Community Health Service Center of Pudong New District, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Ultrasonography, Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Background: Relationship between systemic inflammation and aortic valve stenosis (AVS) has been well demonstrated. This investigation aimed to evaluate the link between various inflammation hematological ratios and patients with AVS.

Methods: Patients with AVS (n = 229) and control (n = 1716) were identified. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed with the proportion of 1:1 using logistic regression based on the variables of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, creatinine (Cr) and glutamate transpeptidase (γ-GT). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to estimate the performance of inflammation hematological ratios for distinguishing AVS. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to identify the independent risk factors of AVS. In addition, restricted cubic splines (RCS) regression analysis revealed the non-linear correlation between inflammation hematological ratios and AVS.

Results: After PSM, 392 patients (196:196) were included. Univariate analysis showed monocyte/high density lipoprotein ratio (MHR) and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were significantly higher in AVS group (MHR, 0.49 ± 0.23 vs 0.32 ± 0.20, p < 0.001, NLR, 3.52 ± 2.52 vs 2.87 ± 1.89, p < 0.001) while lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (LMR) was significantly lower (3.27 ± 1.72 vs 4.08 ± 1.76, p < 0.001). But the level of platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation index (SII) (PLR, 146.27 ± 82.68 vs 143.27 ± 66.95, p = 0.927, SII, 690.22 ± 602.69 vs 610.58 ± 403.33, p = 0.100) did not differ significantly between the two groups. However, in multivariate logistic regression models, only MHR remained to be an independent risk factor of AVS (OR 2.010 with 95%CI 1.040-3.887, p = 0.038). Besides MHR, atrial fibrillation (AF), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG) and hemoglobin (Hgb) were also performed to be independent risk factors of AVS. ROC analysis showed that the cut-off value of MHR (0.2750) indicated AVS with 85.2% sensitivity and 51.5% specificity [95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.691–0.788, the area under the curve [AUC] = 0.740, P < 0.001]. Further, RCS revealed the non-linear correlation between MHR and AVS (p for non-linearity <0.001).

Conclusions: Elevated MHR was independently associated with the presence of AVS. MHR demonstrated stronger associational strength with AVS compared to other inflammatory hematological ratios such as SII, NLR, PLR and LMR.

Introduction

Aortic valve stenosis (AVS) is one of the most common cardiovascular diseases with considerable impact on morbidity and mortality. AVS is progressive with age and present in 2%–5% of patients aged over 65 years (1–3). Still, recent data indicate that chronic inflammation and lipid metabolism disorders play pivotal roles in fibrosis formation and leaflet thickening, which results in severe AVS (4–7).

Over the past decades, close interaction of inflammation and immune system-related cells such as neutrophils, platelets and lymphocyte with the pathogenesis of AVS has attracted great attention (8–12). Accordingly, various inflammation hematological ratios have been developed from the count of these cells in diverse combinations in order to predict the progression and prognosis of AVS (8, 10, 11, 13). Among them, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (LMR) were well-defined inflammation biomarkers that were found to be associated with the severity of AVS in previous studies (10, 11, 14). Systemic inflammation index (SII) was also a novel marker that brought together these peripheral cell counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets, and was demonstrated to predict severe calcific AVS (9). In a recent study, monocyte/high density lipoprotein ratio (MHR) was determined as a significant independent predictor for the speed of progression and diagnosis of severe bicuspid AVS (15). However, there is debate about which of the above inflammatory hematological ratios has the best predictive performance for AVS risk.

This study sought to investigate the association between various inflammatory hematological ratios and AVS.

Methods

Study population

This was a retrospective, observational study. We screened consecutive patients who underwent transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) at the Heart Center of Shanghai East Hospital between September 2019 and September 2023. Patients were included based on the availability of complete laboratory blood tests and echocardiographic data. Exclusion criteria were: no echocardiographic evaluation, white blood cells >11 × 109/L, creatinine (Cr) >707 µmol/L, history of aortic valve replacement surgery, infective endocarditis, acute myocardial infarction, history of immune system disease, and severe aortic valve regurgitation. All patients were evaluated by TTE and categorized into the aortic valve stenosis group (AVS group) or the control group (Non-AVS group). Patients in the control group were further excluded if they had any structural or functional cardiac abnormalities. All data were retrospectively collected from the electronic medical record system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A flow chart of the patient enrollment. AVS, aortic valve stenosis group; non-AVS, control group; γ-GT, glutamate transpeptidase; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Cr, creatinine.

Laboratory measurements

Laboratory data were retrieved retrospectively from the electronic medical records.Total complete blood count test (Sysmex K-1000; Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) and blood chemistry parameters (Modular Systems; Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan) were carried out at the biochemistry laboratory during their prior hospital visits between September 2019 and September 2023.

Inflammation hematological ratios were calculated using the following formulas: MHR (monocyte/high density lipoprotein ratio) = monocyte count ÷ HDL-cholesterol value. LMR (lymphocyte/monocyte ratio) = lymphocyte count÷ monocyte count. NLR (neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio) = neutrophil count ÷ lymphocyte count; PLR (platelet/lymphocyte ratio) = platelet count ÷ lymphocyte count; SII (systemic inflammation index) = neutrophil count × platelet count ÷ lymphocyte count.

Echocardiographic examination

Echocardiographic data were obtained retrospectively from stored examinations performed during routine clinical care. Echocardiographic evaluation was obtained using a Philips Epiq7C machine (Phillips, IE) at the Department of Ultrasound in Shanghai East Hospital. The echocardiographers were blind to clinical information. Standard Doppler parameters including ejection fraction, left ventricular end diastolic diameter, aortic maximal jet velocity, and aortic valve maximum pressure gradient were recorded. The diagnosis for AVS met the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association standards (16). AVS was defined as leaflet calcification and a transaortic peak velocity >2.5 m/s by continuous-wave Doppler.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were tested normal distribution by one sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Normally distributed continuous variables were tested by independent-sample t test while abnormally distributed continuous variables were tested by Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared by the Chi-square test.

We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to estimate the performance of inflammation hematological ratios for distinguishing AVS. The optimal cut-off value was calculated based on the highest Youden index (sensitivity + specificity—1). Two logistic regression models were performed to analysis the association between AVS and inflammation hematological ratios. The variables which were considered to be significantly different in univariate analysis were included in Model 2 to adjust the performance of inflammation hematological ratios. Restricted cubic splines (RCS) regression analysis was used to explore the non-linear correlation between inflammation hematological ratios and AVS. Four knots at the 5th, 35th, 65th and 95th percentiles were placed in RCS regression analysis.

P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant in all of the tests. All the statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) and R, Version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Propensity score matching analysis

Two hundred and twenty-nine AVS patients and 1,716 Non-AVS patients were enrolled in this study. Due to the differences of baseline and sample size between the AVS group and control group, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed with the proportion of 1:1. The propensity score was evaluated using logistic regression based on the variables of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, creatinine (Cr) and glutamate transpeptidase (γ-GT). The Match Tolerance was set to 0.02. Absolute standard differences were used to assess the ability of the matching. The matched patients were included in the following analysis.

Results

Characteristics and echocardiographic parameters

After PSM, 196 patients with AVS and 196 patients without AVS were included. Figure 2 showed all the measured covariates before and after PSM, absolute standardized differences for all measured covariates were <10% after matching. Age, sex, hypertension' diabetes, Cr and '-GT were similar in the matched group (p > 0.05, Table 1).

Figure 2. Love plots for baseline covariates between AVS and control group, before and after propensity score matching. GGT, glutamate transpeptidase; Cr, creatinine.

Table 1 showed the characteristics of the matched groups. Compared with the control group, the AVS group had a higher level of neutrophils (Neu), monocytes (Mon), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG) while a lower level of lymphocyte (Lym), hemoglobin (Hgb) and blood platelet (PLT) (p < 0.05). In addition, the two groups differed significantly with the echocardiographic parameters and the proportion of atrial fibrillation (AF) (p < 0.001). White blood cell (WBC), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbAlc), and fast blood glucose didn't differ significantly between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Inflammation hematological ratios in AVS and non-AVS

Figure 3 showed the differences of inflammation hematological ratios between the two groups. MHR and NLR were significantly higher in AVS group (MHR, 0.49 ± 0.23 vs 0.32 ± 0.20, p < 0.001, NLR, 3.52 ± 2.52 vs 2.87 ± 1.89, p < 0.001). LMR in AVS patients was significantly lower than the Non-AVS group (3.27 ± 1.72 vs 4.08 ± 1.76, p < 0.001). The two groups had the similar level of PLR and SII (PLR, 146.27 ± 82.68 vs 143.27 ± 66.95, p = 0.927, SII, 690.22 ± 602.69 vs 610.58 ± 403.33, p = 0.100). The cut-off value of MHR (0.2750) indicated AVS with 85.2% sensitivity, 51.5% specificity, [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.691–0.788, AUC=0.740, p < 0.001]. DeLong tests showed MHR's AUC was significantly higher than LMR and NLR (MHR vs LMR, p < 0.001; MHR vs NLR, p < 0.001; LMR vs NLR, p < 0.001). Details of ROC analysis were displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Roc curves and cut-off of MHR, NLR and LMR for AVS. MHR, monocyte/high density lipoprotein ratio; LMR: lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; AUC, area under curve.

Multivariate analysis of inflammation hematological ratios with AVS

Table 2 displayed the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis validating factors associated with AVS. Models 1 demonstrated MHR (OR 5.870 with 95%CI 3.585–9.612, p < 0.001) was an independent risk factor of AVS. After adjusting for other risk factors in model 2, MHR (OR 2.010 with 95%CI 1.040–3.887, p = 0.038) was still found to be significant as the independent risk factor of AVS. Besides MHR, AF, LDL-C, TG and Hgb were performed to be independent risk factors of AVS in model 2. LMR and NLR were evaluated but not selected in the final model.

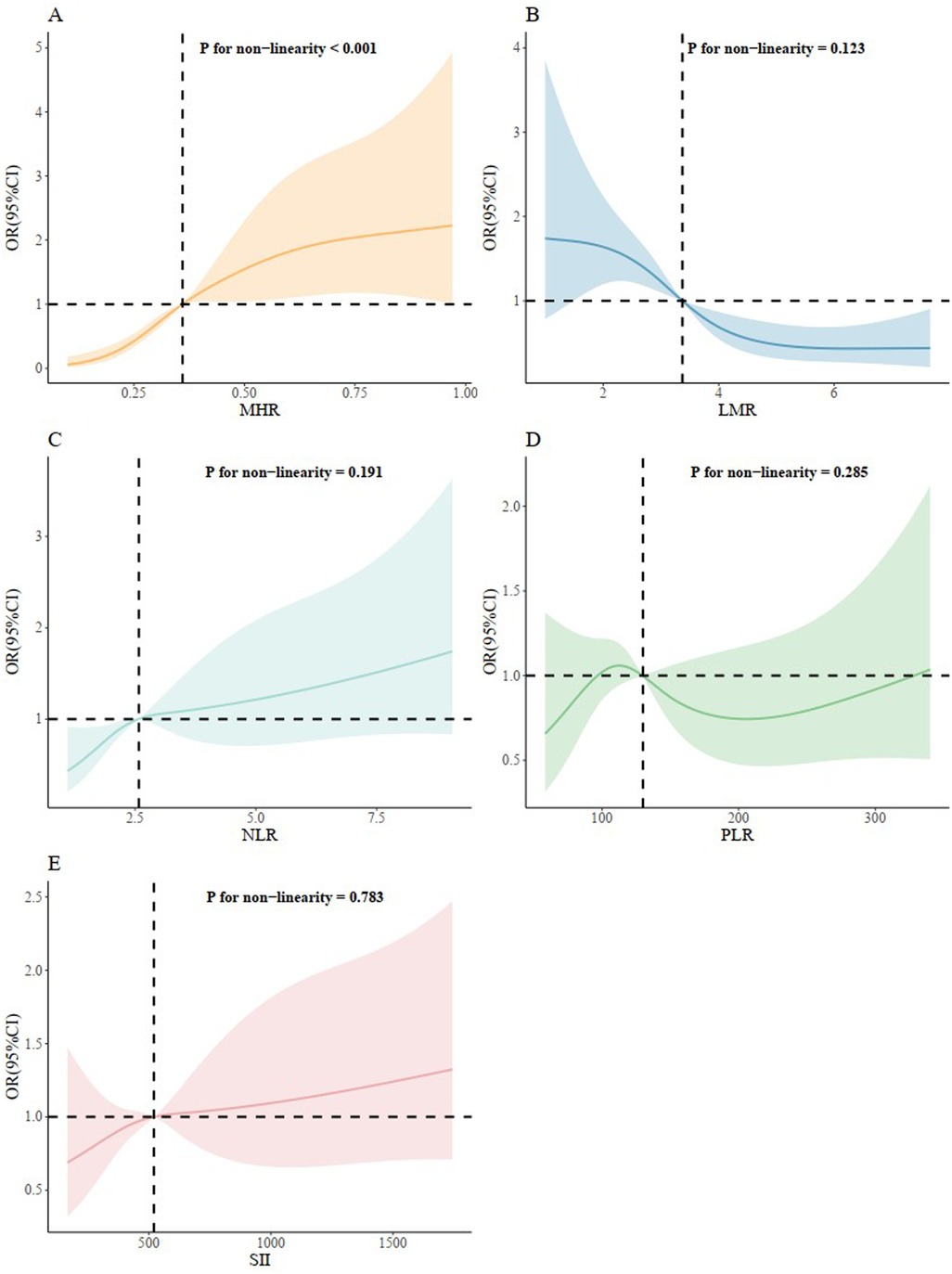

RCS of inflammation hematological ratios with AVS

We further conducted the RCS to evaluated the correlation between inflammation hematological ratios and the risk of AVS (Figure 5). A nonlinear and S-shaped association was showed between MHR and AVS (p for non-linearity <0.001) in the model. Segmented regression identified two breakpoints at 0.33 and 0.83, while the OR = 1 reference corresponded to MHR = 0.36. There was no nonlinear association between LMR, NLR, PLR, SII and AVS.

Figure 5. Restricted cubic splines regression analysis of inflammation hematological ratios with AVS. (A) for MHR; (B) for LMR; (C) for NLR; (D) for PLR; (E) for SII. MHR, monocyte/high density lipoprotein ratio; LMR, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic inflammation index.

Discussion

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, we demonstrated that MHR level was significantly increased in AVS patients compared to patients without AVS, indicating MHR was significantly associated with the presence of AVS. Furthermore, multivariable analysis revealed a stronger independent association between MHR and the presence of AVS compared to established inflammatory ratios such as SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR. To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to comprehensively compare multiple inflammatory hematological ratios, including MHR, SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR, in relation to AVS using PSM to control for confounding factors. Our findings highlight the superior association of MHR with AVS compared to other established ratios.

AVS is a progressive valvular disease in the population that resembles atherosclerosis with activation of calcification, lipoprotein deposition and chronic inflammation (17–20). The endothelial damage resulting from increased mechanical stress and reduced shear stress may allow lipids to penetrate the valvular endothelium, and subsequently, lipid deposition and oxidation occur in valvular endothelium. Afterward, complex inflammatory pathways are activated with the contribution of inflammatory and immune system-related cells such as monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes (21, 22). Biomarkers derived from the counts of the cell types have been widely investigated in recent years due to the fact that they are affordable and available. Among them, PLR, NLR and LMR were shown to possess predictive and prognostic roles in AVS (8, 10, 14). A previous study demonstrated that NLR was related to the severity of calcific AVS and LV systolic dysfunction in patients with severe calcific AVS (23–25). Likewise, PLR was shown to been independently associated with the presence of AVS (11, 25). Other studies have also proven that increased PLR was linked with the severity of degenerative AVS, and PLR should be used to monitor patients' inflammatory responses and the efficacy of treatment (25, 26). SII, which include the peripheral counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets, was recently found to be better than NLR and PLR in predicting severe calcific AVS (9, 27). However, it is not clear which indicator has the most excellent correlation with AVS. In our study, we included MHR, a novel inflammatory marker, and focused on the comparison on AVS association ability among diverse inflammatory hematological ratios. The results highlighted that MHR emerged stronger associational strength with AVS compared to other inflammatory hematological ratios such as SII, NLR, PLR and LMR. More importantly, compared to previous studies, we used propensity score matching analysis to balance the baseline confounding factors that may affect the incidence of AVS, including age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, Cr and γ-GT, partly minimizing the impact of selection bias on the results.

Consistent with the results of our study, a significant association between MHR levels and inflammation was demonstrated by the study of Acikgoz et al. (28). Monocytes are pivotal immune cells and molecules that associate with endothelial cells, attending to aggravation of inflammatory pathways. Since macrophages originate from circulating monocytes, the number of circulating monocytes and monocyte subsets with different properties has attracted attention in both atherosclerosis lesions and valvular disease studies (15, 29, 30). Moreover, HDL-cholesterol is well-known as an anti-inflammatory indicator. HDL protects endothelial cells from inflammation and oxidative stress by preventing the displacement of macrophages and oxidation of low-density lipoprotein molecules, and also by controlling monocyte progenitor cell proliferation and monocyte activation (31–33). Therefore, it is reasonable to use MHR as a single marker by integrating monocyte and HDL-C. The advantage of MHR is that it provides more reliable information than either monocyte or lipoprotein alone for predicting inflammatory and cholesterol burden. Recently, MHR has been reported to be a novel marker for valvular heart disease (34–38). Ozcan et al. reported that MHR is strongly associated with mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and might be a prognostic factor for patients with MVP (34). In our study, ROC analysis and further DeLong tests showed that MHR indicated AVS with a higher sensitivity than LMR and NLR. Most notably, among the five inflammation hematological ratios evaluated, only MHR was positively associated with AVS after adjusting for the confounding factors. Furthermore, in comparison to previous studies, a nonlinear and S-shaped association was firstly revealed between MHR and AVS using RCS analysis while no nonlinear association were shown between other inflammation hematological ratios and AVS, providing more meaningful evidence for the close relationship between MHR and AVS. RCS analysis showed risk accelerated once MHR exceeded 0.33 and plateaus after 0.83, supporting 0.33 as an early-intervention threshold and 0.83 as a high-risk ceiling in clinical practice.

The precise role of the MHR in the pathogenesis of AVS has yet to be fully elucidated. Monocytes and their differentiated descendants, macrophages, play a central role in the initiation and progression of aortic valve calcification (39). In the early stages of AVS, mechanical stress and endothelial dysfunction facilitate the infiltration of lipids and circulating monocytes into the valvular subendothelium. Once localized, monocytes differentiate into macrophages, which phagocytose oxidized lipids and transform into foam cells—a key feature of early valve lesions. These activated macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and promote the expression of osteogenic mediators such as bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and alkaline phosphatase, thereby driving the transition from inflammation to active calcification (40, 41). HDL cholesterol exerts atheroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects that counter these processes. Functionally intact HDL facilitates reverse cholesterol transport from macrophage foam cells, reduces lipid peroxidation, and inhibits the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, thereby limiting further monocyte recruitment (42). Moreover, HDL-associated enzymes like paraoxonase-1 attenuate oxidative stress, while HDL modulates monocyte activation and macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory phenotypes (43). In AVS, however, HDL may become dysfunctional—losing its protective capacity—due to oxidative modification or systemic inflammation, thereby exacerbating valvular injury and calcification (15). The MHR thus integrates both the pro-inflammatory burden (monocyte activation) and the anti-inflammatory capacity (HDL function), offering a composite biomarker that reflects the net inflammatory–lipid imbalance driving valvular calcification.

TG and LDL are also identified as associated factors of AVS in addition to MHR in multivariate logistic regression analysis. The pathophysiology of AVS was consisted of both an initiation phase including lipid infiltration, oxidation and inflammation, and a propagation phase characterized by fibrosis and calcification. Emerging studies revealed lifelong exposure to high cholesterol increases the risk of symptomatic AVS (19, 44, 45). Additionally, the prevalence of AF in patients with AVS is high and AF is associated with poor prognosis in AVS (46–48). Age-related changes in heart structure (left atrial dilation, left ventricular hypertrophy and increased fibrosis) in conjunction with chronic pressure or volume overload induced by the valvular obstacle may explain this over-representation of AF in AVS.

Our study has important clinical relevance. In this study, we confirmed a statistically significant correlation between increased MHR and AVS. These results are consistent with the previous evidence that inflammation and cholesterol play essential roles in the pathology of AVS. Accordingly, modulation of inflammation with the anti-inflammatory therapies combined with statin may slow the progression of AVS. Furthermore, MHR can be calculated easily from the routine blood parameters, and also MHR should be considered as an early associated factor of patients who have a high inflammatory risk and a high rate of progression to severe AVS.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this study is a retrospective and observational study with a relatively limited number of patients. We did not collect longitudinal follow-up information on AVS progression in this cohort, and thus cannot assess the predictive or monitoring value of these inflammatory ratios for disease progression over time. Secondly, other inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 were not evaluated in this study. Thirdly, we measured inflammation hematological ratios only at baseline rather than investigation of temporal variations. Finally, although we carefully controlled for the major known confounders, unknown factors may still have interfered inflammation parameters. A large number of large-scale, multicenter prospective studies with serial measurements are still needed in the future to further illustrate the predictive value of MHR in patients with AVS and evaluate their role in tracking AVS progression.

Conclusions

The present study suggested that elevated MHR level was significantly associated with the presence of AVS for the first time in the literature. MHR showed the best associational strength in AVS than other inflammation hematological ratios such as SII, NLR, PLR and LMR.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the hospital ethics committee of Shanghai East Hospital and carried out according to the principles of the declaration of Helsinki. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from primarily isolated as part of your previous study for which ethical approval was obtained. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XG: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MW: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. LW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. SH: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft. BH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TC: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. LX: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. WW: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. QZ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JH: Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JX: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by grants from the Key Disciplines Group Construction Project of Shanghai Pudong New Area Health Commission (PWZxq2022-02), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72204187) and the Science Foundation of Shanghai Pudong Municipal Health Commission (PW2022A-06).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all who took part in the investigation.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Harris AW, Pibarot P, Otto CM. Aortic stenosis: guidelines and evidence gaps. Cardiol Clin. (2020) 38(1):55–63.31753177

2. Zheng KH, Tzolos E, Dweck MR. Pathophysiology of aortic stenosis and future perspectives for medical therapy. Cardiol Clin. (2020) 38(1):1–12.31753168

3. Kanwar A, Thaden JJ, Nkomo VT. Management of patients with aortic valve stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc. (2018) 93(4):488–508. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.01.020

4. Henning RJ. The current diagnosis and treatment of patients with aortic valve stenosis. Future Cardiol. (2021) 17(6):1143–60. doi: 10.2217/fca-2020-0140

5. Yu Chen H, Dina C, Small AM, Shaffer CM, Levinson RT, Helgadóttir A, et al. Dyslipidemia, inflammation, calcification, and adiposity in aortic stenosis: a genome-wide study. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(21):1927–39. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad142

6. Lau D, Giugliano RP. Lipoprotein(a) and its significance in cardiovascular disease: a review. JAMA Cardiol. (2022) 7(7):760–9. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0987

7. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Lipoprotein(a) is linked to atherothrombosis and aortic valve stenosis independent of C-reactive protein. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(16):1449–60. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad055

8. Akdag S, Akyol A, Asker M, Duz R, Gumrukcuoglu HA. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio may predict the severity of calcific aortic stenosis. Med Sci Monit. (2015) 21:3395–400. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894774

9. Erdoğan M, Öztürk S, Kardeşler B, Yiğitbaşı M, Kasapkara HA, Baştuğ S, et al. The relationship between calcific severe aortic stenosis and systemic immune-inflammation index. Echocardiography. (2021) 38(5):737–44. doi: 10.1111/echo.15044

10. Shahim B, Redfors B, Lindman BR, Chen S, Dahlen T, Nazif T, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement: the PARTNER trials and registries. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11(11):e024091. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024091

11. Yayla Ç, Açikgöz SK, Yayla KG, Açikgöz E, Canpolat U, Kirbaş Ö, et al. The association between platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and inflammatory markers with the severity of aortic stenosis. Biomark Med. (2016) 10(4):367–73. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2015-0016

12. Natorska J, Undas A. Blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in aortic valve stenosis: links with inflammation and calcification. Thromb Haemost. (2015) 114(2):217–27. doi: 10.1160/TH14-10-0861

13. Schiattarella GG, Perrino C. Inflammation in aortic stenosis: shaping the biomarkers network. Int J Cardiol. (2019) 274:279–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.07.026

14. Ma X, Ma H, Yun Y, Chen S, Zhang X, Zhao D, et al. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in predicting the calcific aortic valve stenosis in a Chinese case-control study. Biomark Med. (2020) 14(14):1329–39. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2020-0228

15. Duran Karaduman B, Ayhan H, Keleş T, Bozkurt E. Association between monocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and bicuspid aortic valve degeneration. Turk J Med Sci. (2020) 50(5):1307–13. doi: 10.3906/sag-2006-60

16. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, de Leon AC, Faxon J, Freed DP, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease): developed in collaboration with the society of cardiovascular anesthesiologists: endorsed by the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions and the society of thoracic surgeons. Circulation. (2006) 114(5):e84–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857

17. Cho KI, Sakuma I, Sohn IS, Jo SH, Koh KK. Inflammatory and metabolic mechanisms underlying the calcific aortic valve disease. Atherosclerosis. (2018) 277:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.029

18. Conte M, Petraglia L, Campana P, Gerundo G, Caruso A, Grimaldi MG, et al. The role of inflammation and metabolic risk factors in the pathogenesis of calcific aortic valve stenosis. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2021) 33(7):1765–70. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01681-2

19. Parisi V, Leosco D, Ferro G, Bevilacqua A, Pagano G, de Lucia C, et al. The lipid theory in the pathogenesis of calcific aortic stenosis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2015) 25(6):519–25. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.02.001

20. Shvartz V, Sokolskaya M, Ispiryan A, Basieva M, Kazanova P, Shvartz E, et al. The role of «novel» biomarkers of systemic inflammation in the development of early hospital events after aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. Life (Basel). (2023) 13(6):1395. doi: 10.3390/life13061395

21. Alzubi J, Pressman GS. Aortic stenosis: new insights into predicting disease progression. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2023) 24(9):1154–5. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jead132

22. Willner N, Prosperi-Porta G, Lau L, Nam Fu AY, Boczar K, Poulin A, et al. Aortic stenosis progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2023) 16(3):314–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.10.009

23. Song J, Zheng Q, Ma X, Zhang Q, Xu Z, Zou C, et al. Predictive roles of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein in patients with calcific aortic valve disease. Int Heart J. (2019) 60(2):345–51. doi: 10.1536/ihj.18-196

24. Avci A, Elnur A, Göksel A, Serdar F, Servet I, Atilla K, et al. The relationship between neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and calcific aortic stenosis. Echocardiography. (2014) 31(9):1031–5. doi: 10.1111/echo.12534

25. Condado JF, Junpaparp P, Binongo JN, Lasanajak Y, Witzke-Sanz CF, Devireddy C, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) can risk stratify patients in transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR). Int J Cardiol. (2016) 223:444–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.260

26. Edem E, Reyhanoğlu H, Küçükukur M, Kırdök AH, Kınay AO, Tekin Ü, et al. Predictive value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in severe degenerative aortic valve stenosis. J Res Med Sci. (2016) 21:93. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.192509

27. Tosu AR, Kalyoncuoglu M, Biter H, Cakal S, Selcuk M, Çinar T, et al. Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index for major adverse cardiac events and mortality in severe aortic stenosis patients after TAVI. Medicina (Kaunas). (2021) 57(6):588. doi: 10.3390/medicina57060588

28. Acikgoz N, Kurtoğlu E, Yagmur J, Kapicioglu Y, Cansel M, Ermis N. Elevated monocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and endothelial dysfunction in Behçet disease. Angiology. (2018) 69(1):65–70. doi: 10.1177/0003319717704748

29. Li Y, Chen D, Sun L, Chen Z, Quan W. Monocyte/high-density lipoprotein ratio predicts the prognosis of large artery atherosclerosis ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:769217. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.769217

30. Zhou Y, Wang L, Jia L, Lu B, Gu G, Bai L, et al. The monocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in the prediction for atherosclerosis: a retrospective study in adult Chinese participants. Lipids. (2021) 56(1):69–80. doi: 10.1002/lipd.12276

31. Tudurachi BS, Anghel L, Tudurachi A, Sascău RA, Stătescu C. Assessment of inflammatory hematological ratios (NLR, PLR, MLR, LMR and monocyte/HDL-cholesterol ratio) in acute myocardial infarction and particularities in young patients. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24(18):14378. doi: 10.3390/ijms241814378

32. Liu Z, Fan Q, Wu S, Wan Y, Lei Y. Compared with the monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio (MHR) and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), the neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein ratio (NHR) is more valuable for assessing the inflammatory process in Parkinson’s disease. Lipids Health Dis. (2021) 20(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01462-4

33. Guo X, Ma L. Inflammation in coronary artery disease-clinical implications of novel HDL-cholesterol-related inflammatory parameters as predictors. Coron Artery Dis. (2023) 34(1):66–77. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000001198

34. Abacioglu OO. Monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio: a prognostic factor for mitral valve prolapse? Bratisl Lek Listy. (2020) 121(2):151–3. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2020_021

35. Karahan S, Okuyan E. Monocyte-to-high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as a predictor of mortality in patients with transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2021) 25(16):5153–62. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202108_26529

36. Yalim Z, Ersoy İ. Evaluation of inflammation markers in mitral valve prolapse. Arch Cardiol Mex. (2022) 92(2):181–8. doi: 10.24875/ACM.21000127

37. Jiang M, Yang J, Zou H, Li M, Sun W, Kong X. Monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ratio (MHR) and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide cohort study in the United States. Lipids Health Dis. (2022) 21(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12944-022-01638-6

38. Xi J, Men S, Nan J, Yang Q, Dong J. The blood monocyte to high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (MHR) is a possible marker of carotid artery plaque. Lipids Health Dis. (2022) 21(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12944-022-01741-8

39. Bartoli-Leonard F, Zimmer J, Aikawa E. Innate and adaptive immunity: the understudied driving force of heart valve disease. Cardiovasc Res. (2021) 117(13):2506–24. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvab273

40. Mathieu P, Bouchareb R, Boulanger MC. Innate and adaptive immunity in calcific aortic valve disease. J Immunol Res. (2015) 2015:851945. doi: 10.1155/2015/851945

41. Hjortnaes J, Butcher J, Figueiredo JL, Riccio M, Kohler RH, Kozloff KM, et al. Arterial and aortic valve calcification inversely correlates with osteoporotic bone remodelling: a role for inflammation. Eur Heart J. (2010) 31(16):1975–84. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq237

42. Torres N, Guevara-Cruz M, Velázquez-Villegas LA, Tovar AR. Nutrition and atherosclerosis. Arch Med Res. (2015) 46(5):408–26. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.05.010

43. Soran H, Schofield JD, Durrington PN. Antioxidant properties of HDL. Front Pharmacol. (2015) 6:222. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00222

44. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, Ference BA, Arsenault BJ, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European atherosclerosis society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(39):3925–46. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac361

45. Nazarzadeh M, Pinho-Gomes AC, Bidel Z, Dehghan A, Canoy D, Hassaine A, et al. Plasma lipids and risk of aortic valve stenosis: a Mendelian randomization study. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41(40):3913–20. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa070

46. Iung B, Algalarrondo V. Atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis: complex interactions between 2 diseases. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13(18):2134–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.06.028

47. Matsuda S, Kato T, Morimoto T, Taniguchi T, Minamino-Muta E, Matsuda M, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Cardiol. (2023) 81(2):144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2022.08.006

Keywords: aortic valve stenosis, cholesterol, inflammation hematological ratios, monocyte/high density lipoprotein ratio, propensity score matching analysis

Citation: Gong X, Wang M, Wang L, Huang S, Huang B, Chen T, Xia L, Wei W, Zhang Q, Hu J and Xu J (2026) Association between inflammatory hematological ratios and aortic valve stenosis: a propensity-matched analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1482313. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1482313

Received: 18 August 2024; Revised: 22 December 2025;

Accepted: 22 December 2025;

Published: 12 January 2026.

Edited by:

Stephanie Sellers, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, CanadaReviewed by:

Uğur Canpolat, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, TürkiyeGloria Santangelo, IRCCS Ca ‘Granda Foundation Maggiore Policlinico Hospital, Italy

Copyright: © 2026 Gong, Wang, Wang, Huang, Huang, Chen, Xia, Wei, Zhang, Hu and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Xu, MTM5MTY0OTg5MDRAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Jianqiang Hu, aHVqcTE2M0AxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Xin Gong

Xin Gong Min Wang2,†

Min Wang2,† Liang Wang

Liang Wang Qi Zhang

Qi Zhang Jing Xu

Jing Xu