- 1Department of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Vascular and Interventional Professionals, LLC, Hinsdale, IL, United States

- 2Department of Pediatrics, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 3Department of General Internal Medicine, The Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, United States

- 4College of Osteopathic Medicine, Touro University California, Vallejo, CA, United States

- 5Center for Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

- 6Department of Psychology, Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Objective: Venous Origin Chronic Pelvic Pain (VO-CPP) causes pelvic pain in women, and is associated with other dysautonomia syndromes such as postural orthostasis and tachycardia syndrome (POTS), chronic fatigue, interstitial cystitis, and fibromyalgia. These conditions have been shown to have associations with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, migraine headache, irritable bowel syndrome, and brain fog. In this study, a multisyndromic patient was treated for VO-CPP. Pelvic pain, dysautonomia, and neuropsychiatric scores were tracked in this patient.

Methods: In a multisyndromic patient with VO-CPP, abnormal venous pooling was treated with endovascular stenting and sclerotherapy. Neuropsychiatric testing was performed before and after intervention.

Results: Along with improvement in scores for pelvic pain, POTS, interstitial cystitis, and migraines, repeat neuropsychiatric testing showed improvement in Memory Functioning Recall and Depression Inventory. The patient’s previous disability status was removed.

Conclusions: The patient's response to endovascular treatment supports a unifying concept of diminished venous return as a contributor to multiple syndromes that may be linked to a single phenotype.

Introduction

The chronic pelvic pain (CPP) condition known as “pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS)” (now commonly called Venous Origin Chronic Pelvic Pain, or “VO-CPP”) is responsible for causing up to 30% of chronic pelvic pain in women (1). Symptoms of VO-CPP typically include chronic positional pelvic pain and heaviness, vulvodynia, and dyspareunia. It can be safely and effectively treated by correcting pelvic venous drainage pathways to eliminate pelvic venous pooling. This treatment involves embolization of pelvic varices and/or stenting of compromised iliac vein outflow (2, 3). Recently, VO-CPP has been shown to be associated with other conditions of a pathophysiology of trapped blood volume below the waist, including “dysautonomia”-type symptoms such as postural orthostasis and tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and chronic fatigue syndrome (4, 5). Interstitial cystitis is also comorbid with dysautonomia and with pelvic varicosities (6). These conditions, in turn, are entwined with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS), migraine headache, and brain fog (5, 7–9).

A clinical challenge lies in considering a unifying concept of pathophysiology that spans multiple medical disciplines. In this study, we present a case of a complex multisystemic process in a woman referred for CPP and then treated for VO-CPP. Her response to treatment alleviated not only her CPP but also brain fog.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to an outpatient clinic with CPP. Her neurologist, who was treating her for migraine headaches, had noted symptoms of CPP. She suffered from a multitude of comorbidities as outlined below, involving not only gynecologic and neurologic systems, but also gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, endocrine, hematologic, and psychiatric systems.

Gynecologic: The patient was treated by gynecology for chronic vulvodynia and dyspareunia.

Neurologic: The patient was managed by neurology for chronic migraines as well as seizure disorder. She had numerous Emergency Department admissions for severe migraines requiring intravenous treatment, leading to opioid dependence. Her headache neurologist noted worsening confusion and ability to concentrate during clinic visits, and the clinician ordered neuropsychiatric testing (Supplementary Table 1). While her intelligence test result was in the Superior range, she was inattentive, and her short-term memory was placed in the 47th percentile. The impression was that she had attention deficit disorder (ADD), following which accommodations for college were advised. She was completely disabled; she dropped out of graduate school and was unable to drive due to severe disorientation. She was on multiple medications (Supplementary Table 2), but even after the list of medications was reduced, she reported limited ability to concentrate.

Gastrointestinal: History and records noted a long history of severe constipation and bloating, with a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A precipitous decline in her health status was marked by a spontaneous colon perforation 8 years prior. Ever since she suffered from this perforation, she underwent a total of 13 abdominal surgeries, including total colectomy. However, her surgeons noted “poor healing”.

Musculoskeletal: She was treated for back pain related to lumbar spondylosis and underwent several spine surgeries for this, as well as for a spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak.

Cardiovascular: She was seen by cardiology and neurology for POTS with frequent traumatic syncopal episodes.

Endocrine: She was also undergoing treatment by endocrinology for pituitary failure, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency.

Hematologic: She suffered a pulmonary embolus related to the thrombus around a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). The PICC was placed due to difficult venous access for her frequent intravenous migraine treatments.

Psychiatric: She was undergoing treatment for anxiety and depression.

She had no history of electrolyte imbalance, and her renal function was normal. Because of her extensive and multisystemic ailments, she had contacts of 60 doctors in her phone.

At consultation, she was noted to be a poor historian, and she demonstrated confusion and distraction. She reported daily migraine headaches, difficulty concentrating, as well as non-cyclic pelvic pain associated with upright posture for the past 8 years. She also reported vulvodynia and dyspareunia for the same time period. Questionnaire responses to the International Pelvic Pain Society (IPSS) Pelvic Pain Assessment Form documented chronic pelvic pain (International Pelvic Pain Society, 2007), and responses to the validated Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ) qualified as “moderate to extreme” orthostatic hypotension (10). A physical examination showed a tall and muscular woman who was anxious and confused. She often trailed off her speech and did not complete sentences. She had a Beighton score exceeding the score needed to diagnose generalized joint hypermobility (11, 12). An external pelvic examination showed exquisite vulvar tenderness and scattered vulvar varicose veins.

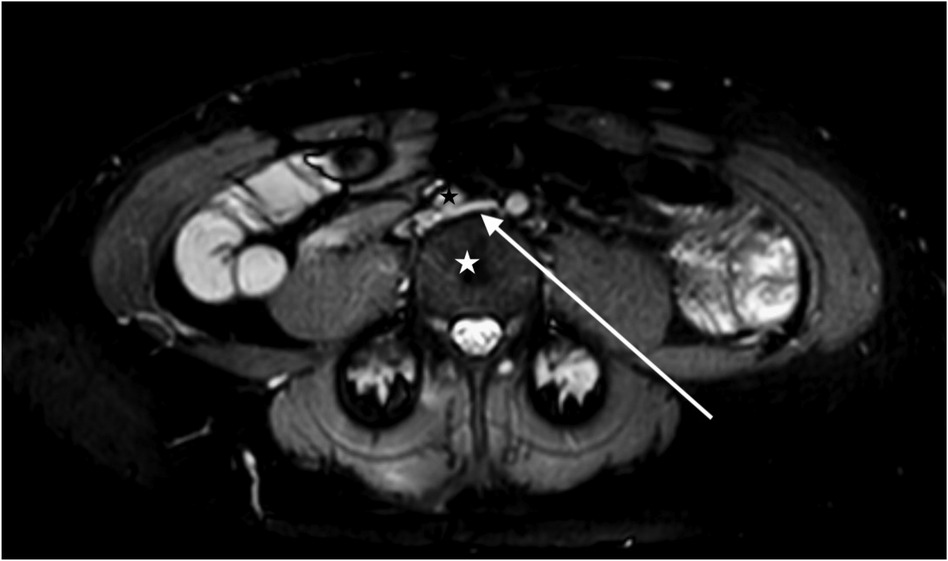

Cross-sectional imaging with magnetic resonance venography (Figure 1) revealed >50% diameter compression of the left common iliac vein between the right common iliac artery and the lumbar vertebral body.

Figure 1. A magnetic resonance venogram in the axial plane shows a compressed left common iliac vein (white arrow) between the lumbar 4 vertebral body (white star) and the right common iliac artery (black star).

The impressions from the consultation were as follows: (1) VO-CPP shown by her IPSS score, a history of >6 months non-cyclic pelvic pain, and an iliac vein stenosis of >50%; (2) orthostatic hypotension shown by her OHQ score; (3) refractory migraine headaches; (4) Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (generalized joint hypermobility subtype) related to her Beighton test and poor healing history, and (5) brain fog. Based on these clinical impressions and cross-sectional imaging findings, it was recommended that she undergo venography with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and possible iliac vein stenting.

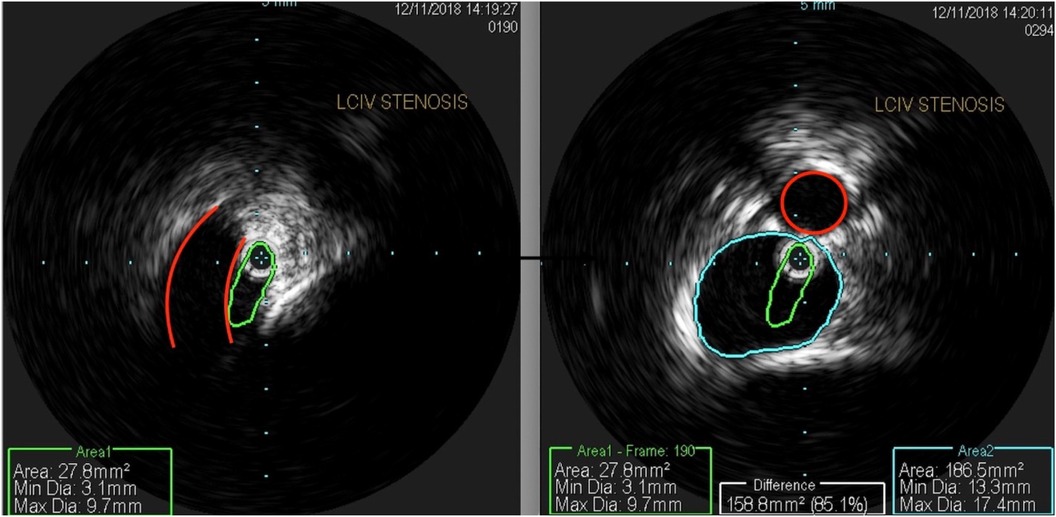

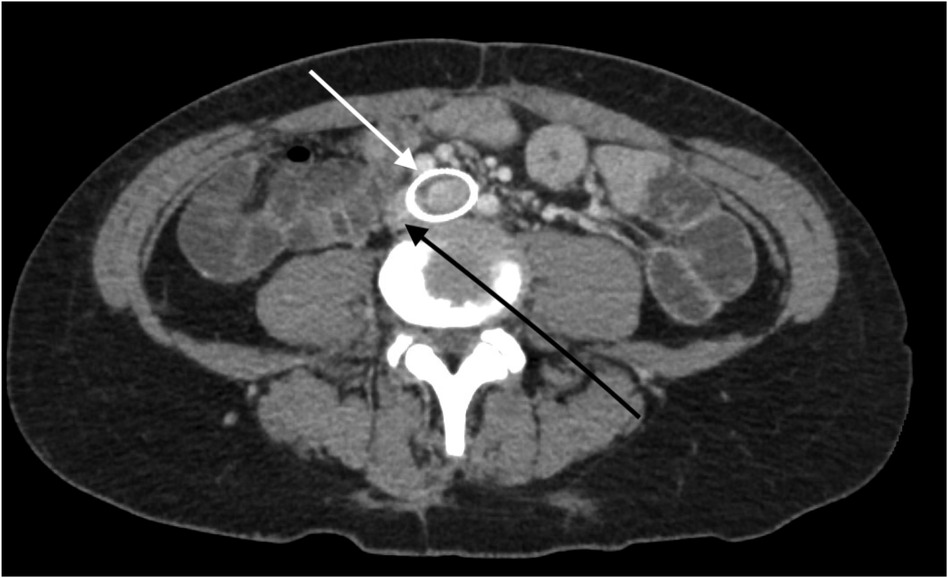

The patient underwent treatment at AMITA Hinsdale Hospital (Hinsdale, IL, USA). Under moderate sedation, the patient underwent traditional transcatheter venography (Figure 2). This, along with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), confirmed significant (25) left common iliac vein stenosis by an overlying common iliac artery of greater than 50% (25) (Figure 3). She was initially treated with placement of a left iliac vein stent. Post procedure, she was prescribed clopidogrel for 30 days. 30–40 mm Hg waist-high compression hose were ordered, and she was advised to hydrate daily with 100 oz of electrolyte drinks. She underwent a routine clinical and imaging follow-up at 1 and 6 months. Confusion and dizzy spells were reported as alleviated at 1 month, but still some diminished cognitive clarity persisted. At 6 months, she reported improvement in cognition to a point where she reenrolled in graduate studies and resumed driving. According to her neurologist, she was having significantly fewer headaches and fatigue was reported to be reduced. Slight dizziness persisted, and she was started on a short course of midodrine. Dyspareunia persisted. She was subsequently administered a percutaneous ultrasound-guided injection of the vaginal wall and vulvar varices with 0.5% sotradecol foam using the Tessari technique (13). There were no immediate procedural complications, and her dyspareunia resolved after 3 months. At 12 months after iliac vein stenting, repeat neuropsychiatric testing (with the same examiner) showed her memory at the 95th percentile. Her full-scale IQ increased modestly. The Beck Depression Inventory II score moved to the normal range. The overall impression was “normal exam” (Supplementary Table 1). At 18 months after stenting, her dizziness returned, and dyspareunia reappeared. An ultrasound suggested a developing right iliac vein stenosis. Subsequently, a CT venogram showed the left stent pressing upon an already partially compressed right common iliac vein (Figure 4). She then underwent placement of a right-sided iliac vein stent. She was again prescribed clopidogrel, but for only 3 months, and again advised to drink 100 oz electrolyte solution daily and wear waist-high compression hose.

Figure 2. Venographic images at the time of procedure from a left common femoral vein access show (left) an en-face widening of the central left common iliac vein (white arrow) and the stenotic left external iliac vein (black arrow). After stenting (right), the affected areas are covered by the self-expanding stents.

Figure 3. An intravascular ultrasound shows (left) a profile of a compressed left common iliac vein (green) by an overlying right common iliac artery (red). The right-sided image shows a composite of the normal portion of the left common iliac vein (blue) and a compressed central left common iliac vein (green), representing 85% area stenosis. The right common iliac artery is outlined in red.

Figure 4. A CT venogram in the axial plane shows a stented left common iliac vein (white arrow) and the adjacent compressed right common iliac vein (black arrow).

At 30-month follow-up after initial iliac vein stenting, she reported no dyspareunia and no vaginal pain. She experienced much-reduced migraine headaches, which were down to four per month from every day. She had no syncopal episodes ever since she underwent her procedures. After completing graduate school, she started her own business. Many of her preprocedural medications were discontinued (Supplementary Table 2). Upon an examination, she appeared more alert than her preprocedural condition. Her speech was spontaneous and she completed sentences. She had no vulvar tenderness or vulvar varicose veins. She was scheduled for an annual clinic and imaging follow-up.

Discussion

This patient case illustrates how pelvic venous obstruction or insufficiency may be related to other sometimes disabling syndromes of unknown cause. POTS and its resulting orthostatic hypotension can be disabling (8). While POTS certainly has multifactorial potential causes, in this patient, we propose that it responded to addressing impaired venous blood return to the heart, with resulting diminished cerebral blood flow. Physiologic studies have shown that patients subjected to orthostatic stress had decreased cardiac filling pressure and that female patients showed statistically significant drops in stroke volume and systolic blood pressure, and increased heart rate. It has also been shown that sympathetic response to orthostatic positional changes in terms of muscle sympathetic nerve activity and serum catecholamine measurements was not significantly different between males and females, supporting the conclusion that orthostatic intolerance in females is due to the cardiovascular components of decreased cardiac filling pressure and stroke volume, as opposed to a blunted sympathetic response (14). A study by Edgell et al. took this concept further and tied in the other concepts with cerebral perfusion. In this study, patients subjected to orthostatic stress in terms of moving from a supine to an upright position also showed significant increases in heart rate and decreases in stroke volume. Furthermore, the same patients were measured to have significant decreases in cardiac output, end-tidal CO2, and middle cerebral artery velocity with orthostatic stress (15).

In the patient presented in our study, we propose that her cognitive symptoms had at least some basis in decreased cerebral perfusion as described by Edgell et al. Prior to endovascular treatment, her imaging showed an obstruction of venous flow in the pelvis due to vascular compression. With the correction of this vascular compression, venous congestion of the pelvic structures diminished, cardiac venous return likely improved, and measured cognitive function improved. Future studies that could lend support to this hypothesis would involve controlled measurement of cardiac output and cerebral arterial flow both before and after endovascular treatment.

In our practice, we administer a survey of comorbid symptoms to all VO-CPP patients at each visit. Many of our patients have been found to qualify as having severe dysautonomia based on validated criteria. Symptoms of POTS and migraines have been alleviated significantly in many after vein treatment (5). A survey of the PCS online support group done in 2021 was positive for correlation with many of these related groups of comorbidities (POTS, IBS, migraine, interstitial cystitis, chronic fatigue, anxiety attacks) (16). An alternative term to consider for this constellation of symptoms and syndromes may be Orthostatic Flow Syndrome.

Patients with chronic fatigue, POTS, and fibromyalgia experience decreased blood flow to the brain (9, 11, 17, 18) and therefore vascularly linked. In addition, these patients often report the symptom of brain fog. Brain fog has been ill-defined in the past but is often described by patients as cloudiness of thought patterns, impaired memory, difficulty thinking and focusing, and/or difficulty communicating. These descriptors are altogether different from brain fog reports by patients with general fatigue, anxiety, or depression (i.e., thoughts moving too quickly, detached, lost, sleepy) (19), suggesting that the definition of brain fog symptoms is not translated across disorders. Cognitive function has been shown to decline following orthostatic stress in adults with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) (26). Furthermore, patients with POTS experience heightened cognitive impairment, specifically with working memory, accuracy, and information processing, when undergoing orthostatic stress (20). Patients with impaired cerebral blood flow perform poorly on cognitive challenges testing short-term memory and alertness when compared with healthy individuals (21). Decreased cerebral blood flow has been correlated with brain fog symptoms, and what has been regarded as autonomic nervous system dysfunction could relate to functional hypovolemia because of venous pooling in the pelvis leading to decreased cardiac venous return and resulting diminished cerebral perfusion as described by Edgell et al. (15).

In the literature, inattention/brain fog has sometimes been diagnosed as adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or has been reported as a characteristic of dysautonomia and EDS (22, 23). A recently published series found that among patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain, 76% of them also reported brain fog as a symptom in questionnaire responses. After venous intervention, repeat administration of the same questionnaires showed that their mean mean 0–10 brain fog scores decreased by 59% (5). Based on greater than 6-month symptom history and formal neuropsychiatric testing, the patient in this study would be categorized as adult ADHD, Predominantly Inattentive Subtype (24). Our impression was that she could have been suffering cognitively because of diminished cerebral blood flow.

Conclusion

In this study, a complex patient case was presented with the treatment of chronic pelvic pain using stents and sclerosis of the abnormal veins. The patient’s pelvic pain was relieved, as were disabling migraines, syncope, and brain fog, originally diagnosed as ADD. The patient's disability status was removed. While other factors such as reduced pain including reduced migraine headache frequency, reduced need for pain medication, improved sleep, and overall diminished polypharmacy could also be contributory to this patient's symptom alleviation, the potential relevance of compromised cardiac venous return in the setting of chronic venous disease is discussed in this report in this study. While a logical physiologic explanation was submitted for this patient's improved neuropsychiatric testing after correcting for impaired pelvic venous return, the single-case nature of this study and a lack of long-term follow-up beyond 30 months restrict our ability to draw generalizations. A further study using randomization techniques, quantitative venous flow measurement of cerebral perfusion, and serum catecholamine measurements before and after venous treatment may help solidify the concepts introduced here.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SS: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources. MS: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PR: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DK: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BC: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BS: Data curation, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. IS: Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

SS and MS were employed by Vascular and Interventional Professionals, LLC.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors, wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1574432/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Soysal ME, Soysal S, Vıcdan K, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of goserelin and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic congestion. Hum Reprod. (2001) 16(5):931–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.931

2. De Gregorio MA, Guirola JA, Alvarez-Arranz E, Sanchez-Ballestin M, Urbano J, Sierre S. Pelvic venous disorders in women due to pelvic varices: treatment by embolization: experience in 520 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. (2020) 31(10):1560–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2020.06.017

3. Satoshi RK, Lakhanpal S, Satwah V, Lakhanpal G, Malone M, Pappas PJ. Iliac vein stenosis is an underdiagnosed cause of pelvic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. (2018) 6(2):202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.09.007

4. Stewart JM, Taneja I, Medow MS. Reduced central blood volume and cardiac output and increased vascular resistance during static handgrip exercise in postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2007) 293(3):H1908–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00439.2007

5. Smith SJ, Sichlau MJ, Smith BH, Knight DR, Chen B, Rowe PC. Improvement in chronic pelvic pain, orthostatic intolerance and interstitial cystitis symptoms after treatment of pelvic vein insufficiency. Phlebology. (2023) 39(3):202–13. doi: 10.1177/02683555231219737

6. Kaufman MR, Chang-Kit L, Raj SR, Black BK, Milam DF, Reynolds WS, et al. Overactive bladder and autonomic dysfunction: lower urinary tract symptoms in females with postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. (2017) 36(3):610–3. doi: 10.1002/nau.22971

7. Mack KJ, Johnson JN, Rowe PC. Orthostatic intolerance and the headache patient. Semin Pediatr Neurol. (2010) 17(2): 109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2010.04.006

8. Roma M, Marden CL, De Wandele I, Francomano CA, Rowe PC. Postural tachycardia syndrome and other forms of orthostatic intolerance in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Auton Neurosci. (2018) 215:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.006

9. Ross AJ, Medow MS, Rowe PC, Stewart JM. What is brain fog? An evaluation of the symptom in postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. (2013) 23:305–11. doi: 10.1007/s10286-013-0212-z

10. Kaufmann H, Malamut R, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Rosa K, Freeman R. The Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ): validation of a novel symptom assessment scale. Clin Auton Res. (2012) 22(2):79–90. doi: 10.1007/s10286-011-0146-2

11. Beighton P, Paepe AD, Steinmann B, Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Am J Med Genet. (1998) 77(1):31–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980428)77:1%3C31::AID-AJMG8%3E3.0.CO;2-O

12. Castori M. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: an underdiagnosed hereditary connective tissue disorder with mucocutaneous, articular, and systemic manifestations. ISRN Dermatol. (2012) 2012:751768. doi: 10.5402/2012/751768

13. Tessari L, Cavezzi A, Frullini A. Preliminary experience with a new sclerosing foam in the treatment of varicose veins. Dermatol Surg. (2001) 27:58–60. doi: 10.1097/00042728-200101000-00017

14. Fu Q, Witkowski S, Okazaki K, Levine BD. Effects of gender and hypovolemia on sympathetic neural responses to orthostatic stress. Am J Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2005) 289:R109–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00013.2005

15. Edgell H, Robertson AD, Hughson RL. Hemodynamics and brain blood flow during posture change in younger women and postmenopausal women compared with age-matched men. J Appl Physiol. (2012) 112:1482–93. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01204.2011

16. Smith SJ, Sichlau M, Sewall LE, Smith BH, Chen B, Khurana N, et al. An online survey of pelvic congestion support group members regarding comorbid symptoms and syndromes. Phlebology. (2022) 37(8):596–601. doi: 10.1177/02683555221112567

17. Ocon AJ, Medow MS, Taneja I, Clarke D, Stewart JM. Decreased upright cerebral blood flow and cerebral autoregulation in normocapnic postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2009) 297(2):H664–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2009

18. Ibraheem W, Mckenzie S, Wilcox-Omubo V, Abdelaty M, Saji SE, Siby R, et al. Pathophysiology and clinical implications of cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Cureus. (2021) 13(10):e19123. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19123

19. DeLuca J, Johnson SK, Ellis SP, Natelson BH. Cognitive functioning is impaired in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome devoid of psychiatric disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1997) 62(2):151–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.2.151

20. Ocon AJ, Messer ZR, Medow MS, Stewart JM. Increasing orthostatic stress impairs neurocognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Sci. (2012) 122(5):227–38. doi: 10.1042/CS20110241

21. Wells R, Paterson F, Bacchi S, Page A, Baumert M, Lau DH. Brain fog in postural tachycardia syndrome: an objective cerebral blood flow and neurocognitive analysis. J Arrhythm. (2020) 36(3):549–52. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12325

22. Raj V, Haman KL, Raj SR, Byrne D, Blakely RD, Biaggioni I, et al. Psychiatric profile and attention deficits in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2009) 80(3):339–44. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.144360

23. Glans M, Thelin N, Humble MB, Elwin M, Bejerot S. Association between adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and generalised joint hypermobility: a cross-sectional case control comparison. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 143:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.07.006

24. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Vol. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (1994).

25. Gagne PJ, Gasparis A, Black S, Thorpe P, Passman M, Vedantham S, et al. Analysis of threshold stenosis by multiplanar venogram and intravascular ultra- sound examination for predicting clinical improvement after iliofemoral vein stenting in the VIDIO trial. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. (2018) 6(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.07.009

Keywords: academic self-concept, allostatic overload, cerebral blood flow, chronic pelvic pain, medical imaging, mental health outcomes

Citation: Smith SJ, Sichlau MJ, Rowe PC, Knight DRT, Chen B, Smith B.H and Sichlau IC (2026) Case Report: Neuropsychiatric improvement after treatment of pelvic venous disorder in a multisyndromic patient. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1574432. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1574432

Received: 10 February 2025; Revised: 10 December 2025;

Accepted: 16 December 2025;

Published: 12 January 2026.

Edited by:

Kevin M. Hellman, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, United StatesReviewed by:

Quentin Senechal, Centre Cardiologique du Nord, FranceNida Ali Safdar, Osmania University, India

Copyright: © 2026 Smith, Sichlau, Rowe, Knight, Chen, Smith and Sichlau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael J. Sichlau, bXNpY2hsYXVAdmlyY2hpY2Fnby5jb20=

Steven J. Smith1

Steven J. Smith1 Michael J. Sichlau

Michael J. Sichlau Peter C. Rowe

Peter C. Rowe Dacre R. T. Knight

Dacre R. T. Knight