Abstract

Objective:

To compare the efficacy of different types of exercise modalities such as Tai Chi, Baduanjin, and Aerobic exercise in the treatment of hypertension.

Methods:

This article retrieved randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the establishment of databases such as CNKI, WanFang, VIP, CBM, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library to December 9, 2024. After assessing the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, a network meta-analysis was performed using Rev Man 5.4 and Stata 15 software. The primary outcome indicator of this article is Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement (ABPM), which includes 24-h average systolic blood pressure (SBP) and 24-h average diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Results:

A total of 63 RCTs meeting the criteria were included, involving 5,663 patients. The network meta-analysis results showed that compared with the control group, Light-intensity continuous training (LIAE)+antihypertensive medication [WMD = −1.82, 95%CI(−2.93, −0.71)] was the most effective intervention for lowering SBP. For lowering DBP, Wuqinxi + antihypertensive medication [WMD = −2.78, 95% CI (−4.1,−1.45)] was the most effective intervention. And the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Exercise therapy combined with antihypertensive drugs may achieve a more significant blood pressure-lowering effect, and LICT, Wuqinxi, and Liuzijue may be higher priority options.

Systematic Review Registration:

http://wwwcrdyork.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, PROSPERO CRD42024626332.

1 Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most significant health issues globally. It has a high prevalence rate and is highly predisposed to giving rise to complications such as cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney diseases. It is also one of the major factors contributing to the reduction of the average lifespan (1, 2). Currently, the prevalence of hypertension continues to increase, and the overall prevalence rates of hypertension in males and females are relatively similar (1). In a global epidemiological survey, high systolic blood pressure (SBP) was identified as the primary risk factor for mortality (accounting for 10.4 million deaths) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (amounting to 218 million) (3). Hypertension is a condition that can potentially be reversed. The traditional treatment mainly relies on pharmacotherapy, yet it is associated with multiple adverse effects and often fails to achieve satisfactory blood pressure control (4, 5). With the advancement of concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, lifestyle interventions such as health education, dietary modification, weight management, and stress alleviation have gradually gained popularity (6). In recent years, lifestyle intervention using exercise therapy as an auxiliary method to control blood pressure has gradually gained attention and been recommended by multiple guidelines. On the basis of basic drug treatment, selecting an appropriate exercise therapy for intervention can reduce the side effects of drugs and achieve a better blood pressure control effect (7).

As a component of physical therapy, exercise therapy refers to a lifestyle that involves regular engagement in various forms of physical exercise—an approach that can also serve as a preventive measure against diseases. Notably, this therapy holds value across all stages of hypertension management, as physical exercise can be utilized for the prevention, treatment, and ongoing control of the condition (8). Beyond conventional exercise modalities like aerobic exercise, resistance training, and high-intensity interval training (HIIT), traditional Chinese exercises—including Tai Chi (TC), Baduanjin (BDJ), and Wuqinxi (WQX)—also form key components of exercise therapy. What makes this therapy particularly practical is its inherent advantages: it is easy to implement, low in cost, and associated with minimal adverse effects. These traits have allowed it to be widely applied in the prevention and treatment of a variety of diseases, with its most extensive use seen in the adjuvant treatment of cardiovascular diseases (6, 9).

Currently, numerous studies on the treatment of hypertension with exercise have demonstrated that exercise therapy is highly effective in reducing blood pressure in patients with hypertension (10, 11). However, there is a lack of studies comparing the therapeutic effects of different types of exercise, including aerobic exercises of varying intensities, resistance exercises, yoga, and Traditional China exercises. Moreover, in previous research, the comparison between traditional qigong exercises and conventional exercise therapy has often been overlooked. This article aims to compare the therapeutic effects of different types of exercise on patients with hypertension, with the expectation of providing a reference for the clinical management of hypertension.

2 Methods

The method used to conduct this systematic review has been previously published in a registered protocol [PROSPERO registration: CRD42024626332] (Available from: http://wwwcrdyork.ac.uk/PROSPERO/). The content of the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Material 2).

2.1 Databases and retrieval strategy

In this article, a systematic search was conducted in databases such as CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), Wanfang Data, VIP (Chongqing VIP Information), Sinomed, Embase, Web of Science, PubMed, and Cochrane Library. The search time range was from the establishment of these databases to December 9, 2024. The search strategy combined MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and free terms, and was adjusted according to the search rules of different databases. The specific Chinese search terms included “exercise therapy”, “Baduanjin”, “Taijiquan”, “Wuqinxi”, “Yoga”, “High-Intensity Interval Training”, “High-Intensity Continuous Training”, “traditional qigong exercises”, “hypertension”, etc.; the English search terms included “Hypertension”, “TaiJi”, “Baduanjin”, “Wuqinxi”, “Qigong”, “kinesitherapy”, “High-Intensity Interval Training”, “resistance training”, etc. Taking CNKI and PubMed as examples, the search formulas are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Query | Search term |

|---|---|

| #1 | Hypertension [Mesh] |

| #2 | ((((((Hypertension[MeSH Terms]) OR (Hypertension[Title/Abstract])) OR (Hypertension[Title/Abstract])) OR (Hypertension[Title/Abstract])) OR (High Blood Pressure[Title/Abstract])) OR (High Blood Pressures[Title/Abstract])) |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #4 | (Tai Ji[Mesh]) OR (Qigong[MeSH]) OR (Exercise Therapy[MeSH]) OR (High-Intensity Interval Training[MeSH]) OR (resistance training[MeSH]) OR (Water Sports[MeSH]) OR (yoga[MeSH]) |

| #5 | (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((Tai Ji[Title/Abstract]) OR (Tai Ji[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tai Chi[Title/Abstract])) OR (Chi, Tai[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tai Chi Chuan[Title/Abstract])) OR (Taiji[Title/Abstract])) OR (Taijiquan[Title/Abstract])) OR (T'ai Chi[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tai Ji Quan[Title/Abstract])) OR (Ji Quan, Tai[Title/Abstract])) OR (Quan, Tai Ji[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tai Ji[MeSH Terms])) OR (baduanjin[Title/Abstract])) OR (wuqinxi[Title/Abstract])) OR (liuzijue[Title/Abstract])) OR (Ch'i Kung[Title/Abstract])) OR (Qi Gong[Title/Abstract])) OR (Qigong[Title/Abstract])) OR (Qigong[MeSH Terms])) OR (daoyin[Title/Abstract])) OR (kinesitherapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Traditional exercises[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise Therapy[MeSH Terms])) OR (Exercise Therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Rehabilitation Exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise, Rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercises, Rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (Rehabilitation Exercises[Title/Abstract])) OR (Therapy, Exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise Therapies[Title/Abstract])) OR (Therapies, Exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (Remedial Exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise, Remedial[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise, Remedial[Title/Abstract])) OR (Remedial Exercises[Title/Abstract])) OR (Cardiopulmonary rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (High-Intensity Interval Training[MeSH Terms])) OR (High-Intensity Interval Training[Title/Abstract])) OR (High Intensity Interval Training[Title/Abstract])) OR (High-Intensity Interval Trainings[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interval Training, High-Intensity[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interval Trainings, High-Intensity[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interval Trainings, High-Intensity[Title/Abstract])) OR (Trainings, High-Intensity Interval[Title/Abstract])) OR (High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercises, High-Intensity Intermittent[Title/Abstract])) OR (High-Intensity Intermittent Exercises[Title/Abstract])) OR (Sprint Interval Training[Title/Abstract])) OR (Sprint Interval Training[Title/Abstract])) OR (high intensity continuous training[Title/Abstract])) OR (resistance training[Title/Abstract])) OR (resistance training[MeSH Terms])) OR (resistance training[Title/Abstract])) OR (Strength Training[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight-Lifting Strengthening Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight-Lifting Strengthening Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Strengthening Programs, Weight-Lifting[Title/Abstract])) OR (Strengthening Program, Weight-Lifting[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight Lifting Strengthening Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight-Lifting Exercise Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise Program, Weight-Lifting[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight Lifting Exercise Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight-Lifting Exercise Programs[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight-Bearing Strengthening Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Strengthening Programs, Weight-Bearing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Strengthening Programs, Weight-Bearing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Weight-Bearing Exercise Program[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise Programs, Weight-Bearing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Exercise Programs, Weight-Bearing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Water Sports[MeSH Terms])) OR (Water Sports[Title/Abstract])) OR (Water Sports[Title/Abstract])) OR (Water Sports[Title/Abstract])) OR (Kayaking[Title/Abstract])) OR (Kayaking[Title/Abstract])) OR (Canoeing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Water Polo[Title/Abstract])) OR (Surfboarding[Title/Abstract])) OR (Boating[Title/Abstract])) OR (Wave Surfing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Rowing[Title/Abstract])) OR (Skiing, Water[Title/Abstract])) OR (yoga[Title/Abstract])) OR (yoga[MeSH Terms])) |

| #6 | #4 OR #5 |

| #7 | #3 AND #6 |

| 中国知网数据库检索策略 | |

| #1 | 高血压+原发性高血压(主题词) |

| #2 | 太极拳+太极拳运动+太极拳练习+24式太极拳+陈式太极拳+杨式太极拳(主题词) |

| #3 | 运动疗法+运动疗法干预+运动疗法训练+运动疗法康复+‘运动疗法/方法'(主题词) |

| #4 | 传统功法+传统功法治疗+传统功法训练(主题词) |

| #5 | 八段锦+八段锦锻炼+八段锦运动+八段锦训练+八段锦干预+八段锦练习(主题词) |

| #6 | 气功+气功疗法+气功锻炼+中国气功+传统气功+导引(主题词) |

| #7 | 运动康复+运动康复训练+运动康复治疗+运动康复干预+运动康复疗法(主题词) |

| #8 | 心肺康复+心肺康复训练+心肺康复治疗+心肺康复运动+心肺康复训练指导(主题词) |

| #9 | 五禽戏+五禽戏锻炼+五禽戏运动(主题词) |

| #10 | 六字诀+六字诀呼吸操+六字诀功法+六字诀训练+六字诀呼吸吐纳功+六字诀养气功(主题词) |

| #11 | HIIT+hiit训练+hiit+hiit干预+‘hiit(高强度间歇训练)’+‘高强度间歇训练(hiit)'(主题词) |

| #12 | 高强度持续训练+抗阻训练+水上运动+瑜伽(主题词) |

| #13 | #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 |

| #14 | #1 AND #13 |

Search strategy for the PubMed database.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria of this study strictly followed the PICOS framework, and the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Study type: Published randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (2) Patients: Patients with a clear diagnosis of essential hypertension. There were no specific requirements for the patients' age, gender, etiology, and severity, etc. The diagnostic criteria only needed to meet any one of the domestic and international clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, such as the “Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension” (12). The specific diagnostic criteria included SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg (1 mmHg≈0.133 kPa) and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 80 mmHg, etc.

2.3 Intervention measures

This article aims to study the therapeutic effects of different exercise therapies on patients with essential hypertension. Therefore, studies in which different exercise therapies or a combination of exercise therapy and conventional medications were used for intervention in the observation group were included. Exercise therapy can be used alone as a blank control; alternatively, conventional drug treatment can be selected for the control group, and the observation group can receive exercise therapy intervention on the basis of the treatment in the control group.

2.4 Efficacy indicators

Main Observation Indicators: Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement (ABPM), including 24-h average systolic blood pressure and 24-h average diastolic blood pressure (They will be referred to as SBP and DBP hereinafter).

2.5 Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria are as follows:(1) Studies that are not randomized controlled trials; (2) Studies involving combined interventions of multiple types of exercises; (3) Articles that are repeatedly published or have been retracted; (4) Literatures for which the full text cannot be downloaded; (5) Literatures with incomplete data of the study subjects and without descriptions of the efficacy indicators; (6) Studies related to secondary hypertension.

2.6 Literature screening and data extraction

Two authors (Liu Longcheng and Wang Jiale from Peking Union Medical College) separately completed the screening and extraction of the literatures. Firstly, the literatures that were obviously irrelevant to this article were excluded by reading the titles and abstracts. Then, the literatures that did not meet the conditions of this study were excluded after downloading the full texts and reading them carefully. After the data extraction was completed, the results were compared. In case of any discrepancies, a third researcher was invited to discuss and make a decision together. Finally, the Excel software was used for data extraction. The extracted data included information such as the authors, publication time, study subjects, sample size, intervention measures, treatment course, and efficacy indicators.

2.7 Risk of bias assessment

In this article, the bias risk tool described in Cochrane Handbook 5.1.0 was used to assess the methodological quality of the included RCTs. The evaluation mainly covered the following aspects: random allocation method, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessment, data completeness, selective reporting, and other biases. For each item, the risk was respectively determined as “unclear bias risk”, “low bias risk”, or “high bias risk”.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this article is 24-h average blood pressure. To ensure the accuracy of the results, this article calculates the differences between the BP and BP at the study baseline and the endpoint as the research data. The standard deviation of the differences is calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient related to the blood pressure before and after the intervention. The calculation formula is as follows (13):In this article, software such as Stata 15.0 and Rev Man 5.4 were used for data analysis in the Network analysis. For the measurement data in this article, the weighted mean difference (WMD) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were used for analysis. When there are loops in the Network map, the node—splitting method is used for the inconsistency test. When P > 0.05, it is considered that there is no heterogeneity. The Stata 15.0 software is used to conduct the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) curve ranking to obtain the optimal intervention measure. Meta-regression and sensitivity analysis were performed using Stata 15.0. The Stata 15.0 software is used to conduct Begg's test. If P > 0.05, it proves that there is no publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening

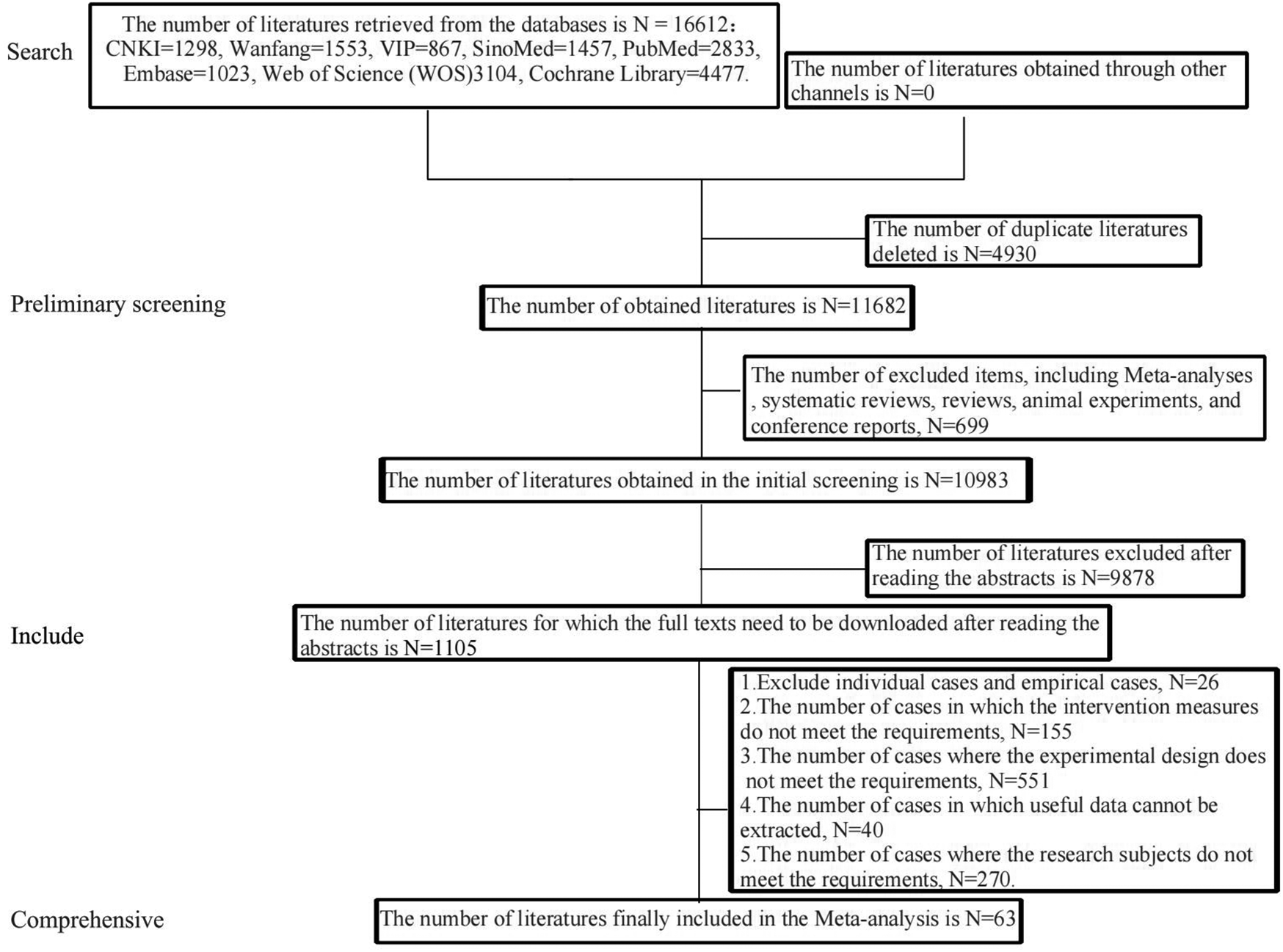

A total of 16,612 literatures were initially retrieved. After removing the duplicate and incorrect literatures, 11,682 literatures remained. Then, 699 literatures, including Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, animal experiments, and conference reports, were excluded. After reading the titles and abstracts, 9,878 literatures were excluded. Finally, 63 literatures were included after reading the full texts. The intervention measures involved a total of 12 types of exercise therapies, namely TC, BDJ, WQX, low-intensity aerobic exercise(LIAE), moderate-intensity aerobic exercise(MIAE), Liuzijue(LZJ), Isometric exercise(IE), Isometric grip strength(IGS), HIIT, Qigong(QG), Resistance training(RT), and Yoga. The process of inclusion and exclusion is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The process of literature inclusion and exclusion.

3.2 Basic characteristics of the included literature

A total of 63 RCTs (14–76) were finally included, among which (14–27, 29–67, 69–70, 72–76) were two-arm trials and 3 trials (28, 68, 71) were three-arm trials. The total sample size was 5,663 cases, including 2,826 cases in the experimental group and 2,837 cases in the control group. The shortest course of treatment in the observation group was 6 weeks, and the longest was 12 months. The most common practice frequency was 1–2 times a day, and the duration of each practice mostly remained around 2 h. The baseline data of the patients were all comparable. The basic characteristics of the included literature are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Number | Included literature | Samplesize/cases | Male/female/example | Average age/years | Intervening measure | Course of treatment | Outcome indicator | Weekly intervention time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | T | C | T | C | T | C | |||||

| 1 | Chunling and Zhang (14) | 30 | 30 | – | – | – | – | BDJ + CON | CON | 2M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 2 | Qinghua et al. (15) | 15 | 15 | – | – | 54 ± 6 | 53 ± 8 | TC + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 3–5 h |

| 3 | Huan (16) | 30 | 30 | 17/13 | 18/12 | 38.07 ± 8.09 | 37.63 ± 9.09 | TC + CT | CT | 2M | BP | 2–3 h |

| 4 | Xiaobin and Luping (17) | 50 | 50 | 20/30 | 22/28 | 66.6 ± 4.5 | 66.4 ± 4.2 | TC + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 2–3 h |

| 5 | Lijuan et al. (18) | 36 | 37 | 19/17 | 14/23 | 66.33 ± 4.74 | 67.51 ± 4.09 | TC + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3 h |

| 6 | Yujie (19) | 40 | 40 | 25/15 | 22/18 | 67.98 ± 4.87 | 67.14 ± 5.01 | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 3–4 h |

| 7 | Fang and He (20) | 27 | 28 | 14/13 | 12/16 | 61.26 ± 3.74 | 62.03 ± 3.51 | BDJ + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 7 h |

| 8 | Hongyu et al. (21) | 30 | 30 | 17/13 | 16/14 | 68.1 ± 10.1 | 70.5 ± 10.2 | BDJ + CT | CT | 3M | BP | – |

| 9 | Hui and Yana (22) | 40 | 40 | 25/15 | 23/17 | 59 ± 6 | 60 ± 5 | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 10 | Chen (23) | 112 | 114 | 68/44 | 70/44 | 60.89 ± 9.70 | 61.33 ± 8.23 | BDJ + CON | CON | 12M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 11 | Liwei et al. (24) | 30 | 30 | 13/14 | 16/12 | 69.23 ± 3.72 | 70.06 ± 3.51 | BDJ + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 2–3 h |

| 12 | Yunhua et al. (25) | 30 | 30 | 10/20 | 18/12 | 54.8 ± 7.6 | 55.7 ± 8.8 | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 2–3 h |

| 13 | Zhanmei et al. (26) | 77 | 77 | – | – | – | BDJ + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 4–5 h | |

| 14 | Yakang (27) | 42 | 42 | 24/18 | 22/20 | 6O.2 ± 4.6 | 60.5 + 4.9 | BDJ + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 15 | Jingyuan (28) | 32 | 32 | 16/16 | 17/15 | 71.5 ± 9.5 | 73.5 ± 10.5 | MIAE + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3 h |

| 32 | 32 | 18/14 | 17/15 | 72 ± 9 | 73.5 ± 10.5 | RT + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3 h | ||

| 16 | Chunli (29) | 50 | 50 | 28/22 | 26/24 | 68.4 ± 2.3 | 69.7 ± 2.8 | LIAE + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 1–2 h |

| 17 | Peiqin (30) | 30 | 30 | 18/12 | 19/11 | 71.65 ± 2.73 | 71.59 ± 2.68 | LIAE + CON | CON | 6M | BP | 1–2 h |

| 18 | Yingxian (31) | 48 | 48 | 29/19 | 27/21 | 68.72 ± 4.03 | 68.43 ± 3.96 | LIAE + CON | CON | 1M | BP | 3–5 h |

| 19 | Linghua et al. (32) | 42 | 42 | 22/20 | 21/21 | 52.52 ± 2.47 | 52.25 ± 2.30 | HIIT + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 20 | Lei et al. (33) | 50 | 50 | 32/28 | 30/30 | – | – | MIAE + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3–5 h |

| 21 | Lixun and Jianquan (34) | 55 | 55 | 25/30 | 24/31 | 64.10 ± 7.03 | 64.21 ± 6.12 | TC + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 22 | Qiu (35) | 58 | 58 | – | – | – | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 4–5 h | |

| 23 | Jian (36) | 18 | 18 | 11/7 | 13/5 | 49.6 ± 7.1 | 46.8 ± 6.4 | RT + CT | CT | 4M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 24 | Na (37) | 75 | 18 | 40/35 | 39/36 | 55.1 ± 3.1 | 54.3 ± 2.8 | RT + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 3–5 h |

| 25 | Xue (38) | 42 | 42 | 22/20 | 23/19 | 68.51 ± 2.97 | 69.24 ± 2.45 | BDJ + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 2–3 h |

| 26 | Xiaoduo et al. (39) | 50 | 50 | 15/35 | 17/33 | 57.5 ± 10.16 | 58 ± 10.03 | LZJ + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 27 | Sun et al. (40) | 136 | 130 | – | – | – | BDJ + CON | CON | 12M | BP | 4–5 h | |

| 28 | Haolei and Jiajia (41) | 27 | 27 | – | – | – | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 4–5 h | |

| 29 | Yamei et al. (42) | 40 | 40 | 29/19 | 22/18 | 66.98 ± 5.48 | 67.02 ± 5.46 | BDJ + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 30 | Hua (43) | 44 | 40 | 24/20 | 21/19 | 44.74 ± 12.10 | 44.86土13.05 | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 31 | Tao et al. (44) | 35 | 35 | 18/17 | 19/16 | 62.4 ± 2.4 | 63.1 ± 2.1 | BDJ + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 32 | Wen et al. (45) | 30 | 30 | – | – | – | WQX + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 2–3 h | |

| 33 | Huihui (46) | 43 | 43 | 21/22 | 20/23 | 46 | 45 | WQX + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3–4 h |

| 34 | Jiangqin and Yujie (47) | 50 | 50 | 28/22 | 29/21 | 72.35 ± 2.31 | 73.02 ± 2.35 | TC + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 35 | Yong et al. (48) | 27 | 31 | – | 39 ± 3.32 | 42 ± 2.86 | BDJ + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 1–2 h | |

| 36 | Yi (49) | 60 | 60 | 39/21 | 38/22 | 69.40 ± 6.33 | 69.33 ± 5.12 | MIAE + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 3–5 h |

| 37 | Yanli (50) | 70 | 66 | 41/29 | 39/27 | 53 | 53.5 | MIAE + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 38 | Tianming (51) | 36 | 40 | 19/17 | 18/22 | 63.9 ± 3.8 | 64.5 ± 3.2 | MIAE + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 39 | Suo Mengmeng (52) | 52 | 52 | 32/20 | 31/21 | 53.1士5.1 | 52.5士4.9 | MIAE + CT | CT | - | BP | 5 h |

| 40 | Xiaofang and Yongxin (53) | 36 | 39 | 24/12 | 22/17 | 39—68 | 41—72 | MIAE + CT | CT | 6M | BP | 5 h |

| 41 | Minfang (54) | 36 | 36 | 20/16 | 21/15 | 52.8 ± 15.8 | 53.8 ± 14.7 | MIAE + CT | CT | 1M | BP | 1–2 h |

| 42 | Xiuling (55) | 75 | 36 | 37/38 | 39/36 | 58.7 ± 10.2 | 59.1 ± 10.5 | MIAE + CT | CT | 8W | BP | 2 h |

| 43 | Qing and Ping (56) | 33 | 36 | – | – | – | MIAE + CT | CT | 7W | BP | 2 h | |

| 44 | Yulong (57) | 34 36 | 36 | 20/14 | 21/13 | 68.5 ± 2.4 | 68.6 ± 2.3 | MIAE + CT | CT | 7W | BP | 2 h |

| 45 | Chan et al. (58) | 82 | 82 | 32/50 | 38/44 | 64.70 ± 7.59 | 65.13 ± 10.22 | TC + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 2 h |

| 46 | Hou et al. (59) | 44 | 43 | 15/29 | 15/28 | 68.84 ± 4,45 | 67.44 ± 4.94 | MIAE + CON | CON | 4M | BP | 3 h |

| 47 | Maruf et al. (60) | 60 | 60 | 13/47 | 22/38 | 50.8 ± 8.31 | 54.75 ± 8.56 | MIAE + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 48 | Ping and Zhong (61) | 60 | 60 | 32/28 | 34/26 | 62.74 ± 3.06 | 62.15 ± 3.66 | TC + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3 h |

| 49 | Kaiyong (62) | 30 | 30 | 25/5 | 23/7 | 63.58 ± 4.20 | 63.46 ± 4.13 | MIAE + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 2 h |

| 50 | Cooper et al. (63) | 48 | 42 | 39/9 | 33/9 | 46.2 ± 9.7 | 49.4 ± 8.9 | MIAE + CON | CON | 6W | BP | 2–3 h |

| 51 | Cramer et al. (64) | 25 | 25 | – | – | – | Yoga + CON | CON | 7M | BP | 1.5 h | |

| 52 | Cohen et al. (65) | 46 | 32 | 23/23 | 16/16 | 48.2 ± 1.6 | 48.3 ± 2.4 | Yoga + CON | CON | 3M | BP | – |

| 53 | Anjana et al. (66) | 34 | 31 | 15/19 | 14/17 | 49.13 ± 8.106 | 43.90 ± 9.24 | Yoga + CT | CT | 2M | BP | 4–5 h |

| 54 | Molmen-Hansen et al. (67) | 28 | 29 | 16/12 | 17/12 | 53.6 ± 6.5 | 51.3 ± 9.2 | MIAE + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 3 h |

| 55 | Gorostegi-Anduaga et al. (68) | 42 | 45 | 28/14 | 30/15 | 54.7 ± 7.6 | 53.1 ± 8.3 | MIAE + CT | CT | 4M | BP | 2–3 h |

| 44 | 45 | 32/12 | 30/15 | 53.5 ± 9.1 | 53.1 ± 8.3 | HIIT + CT | CT | 4M | BP | 2–3 h | ||

| 56 | Chen (69) | 30 | 30 | – | – | – | QG + CON | CON | 4M | BP | 4–5 h | |

| 57 | Xiao et al. (70) | 24 | – | – | – | BDJ + CON | CON | 6M | BP | 4–5 h | ||

| 58 | Cohen et al. (71) | 28 | 22 | – | – | – | IGS + CON | CON | 3M | BP | – | |

| 27 | 22 | – | – | – | IE + CON | CON | 3M | BP | – | |||

| 59 | Wolff et al. (72) | 96 | 95 | 44/52 | 48/47 | 64.7 ± 9.2 | 64.8 ± 7.6 | Yoga + CT | CT | 3M | BP | 3–4 h |

| 60 | Punia et al. (73) | 20 | 20 | – | – | – | – | IGS + CT | CT | 8W | BP | 1–2 h |

| 61 | Izadi et al. (74) | 15 | 15 | 7/7 | 9/6 | – | – | HIIT + CT | CT | 6W | BP | 3–4 h |

| 62 | Shou et al. (75) | 98 | 100 | 48/50 | 55/45 | – | – | TC + CON | CON | 3M | BP | 5–7 h |

| 63 | McCaffrey et al. (76) | 27 | 27 | 10/17 | 9/18 | 56.7 | 56.2 | Yoga + CON | CON | 8W | BP | 2–3 h |

Basic characteristics of the literature.

T, experimental group; C, control group—not reported; CT: standard medication; CON: untreated control; BP:24-h average blood pressure; TC, TiChi; BDJ: Baduanjin; WQX, Wuqinxi; LIAE, low-intensity aerobic training; MIAE, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise; LZJ, Liuzijue; IE, isometric exercise training; IGS, isometric grip strength training; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; QG, Qigong; RT, resistance training; BP, blood pressure; W, weeks; M, months.

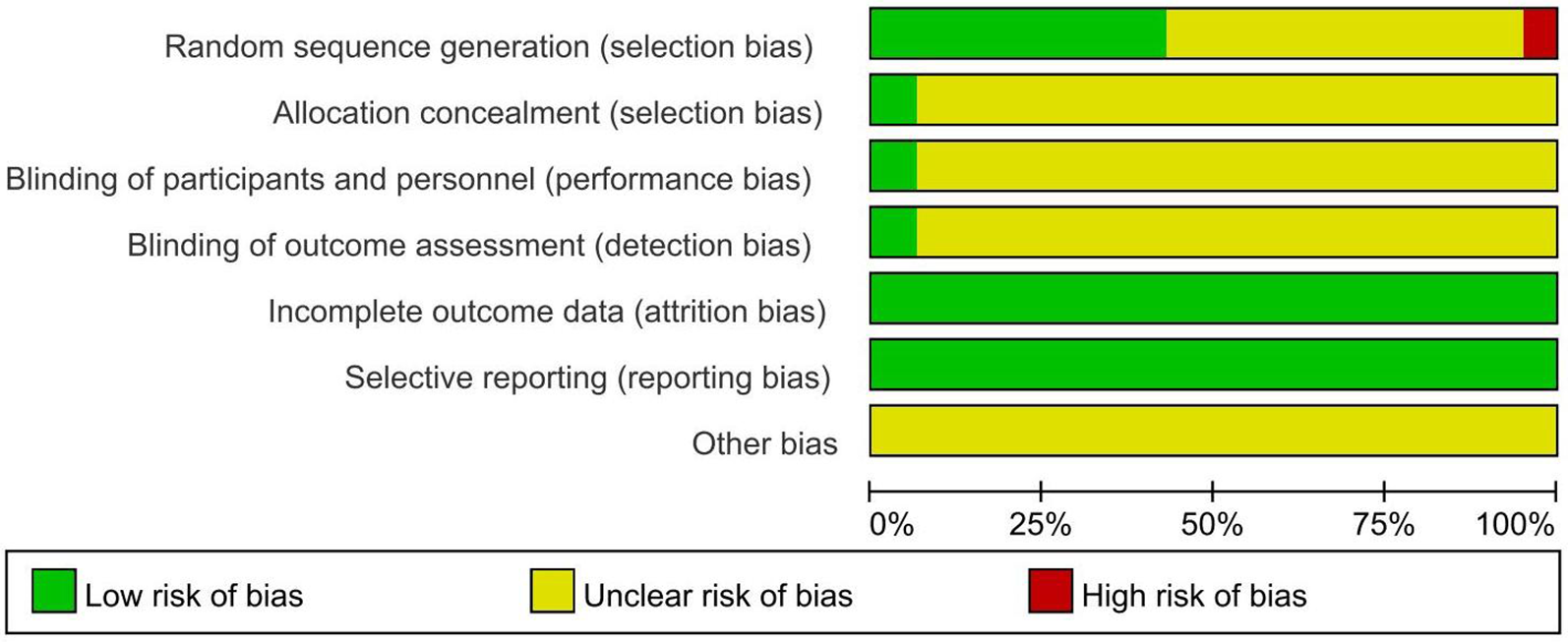

3.3 Assessment of bias risk

Using the RoB scale recommended by Cochrane as the evaluation tool, and the risk bias graph was drawn by the Revman software. A total of 38 RCTs (19, 21–23, 26, 28–30, 36, 37, 40, 41, 43, 45, 46, 49, 50, 52, 53, 55, 61, 63, 65–71, 73–76) mentioned randomization, but did not describe the specific method, and were rated as “unclear bias risk”; 23 RCTs (14, 16–18, 20, 25, 27, 31–34, 37–39, 42, 44, 47, 48, 54, 56, 57, 62, 64) used the random number table method, and 4 RCTs (58–60, 72) used computer randomization, all of which were rated as “low bias risk”. 2 RCTs (24, 51) used the odd-even method and convenience sampling method, and were rated as “high bias risk”. All the literatures did not mention allocation concealment and other sources of bias, and were all rated as “unclear bias risk”. In terms of the implementation of blinding, 4 RCTs (64, 66, 72, 73) adopted double blinding and were rated as “low bias risk”; the rest did not mention blinding and were all rated as “unclear bias risk”. In terms of data integrity assessment, most of the articles had no dropped cases and were rated as “low bias risk”, and a small number of articles that mentioned dropped cases all gave reasons and were all rated as “unclear bias risk”. All the articles had no selective reporting bias and were all rated as “low bias risk”, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Risk of bias assessment of included studies.

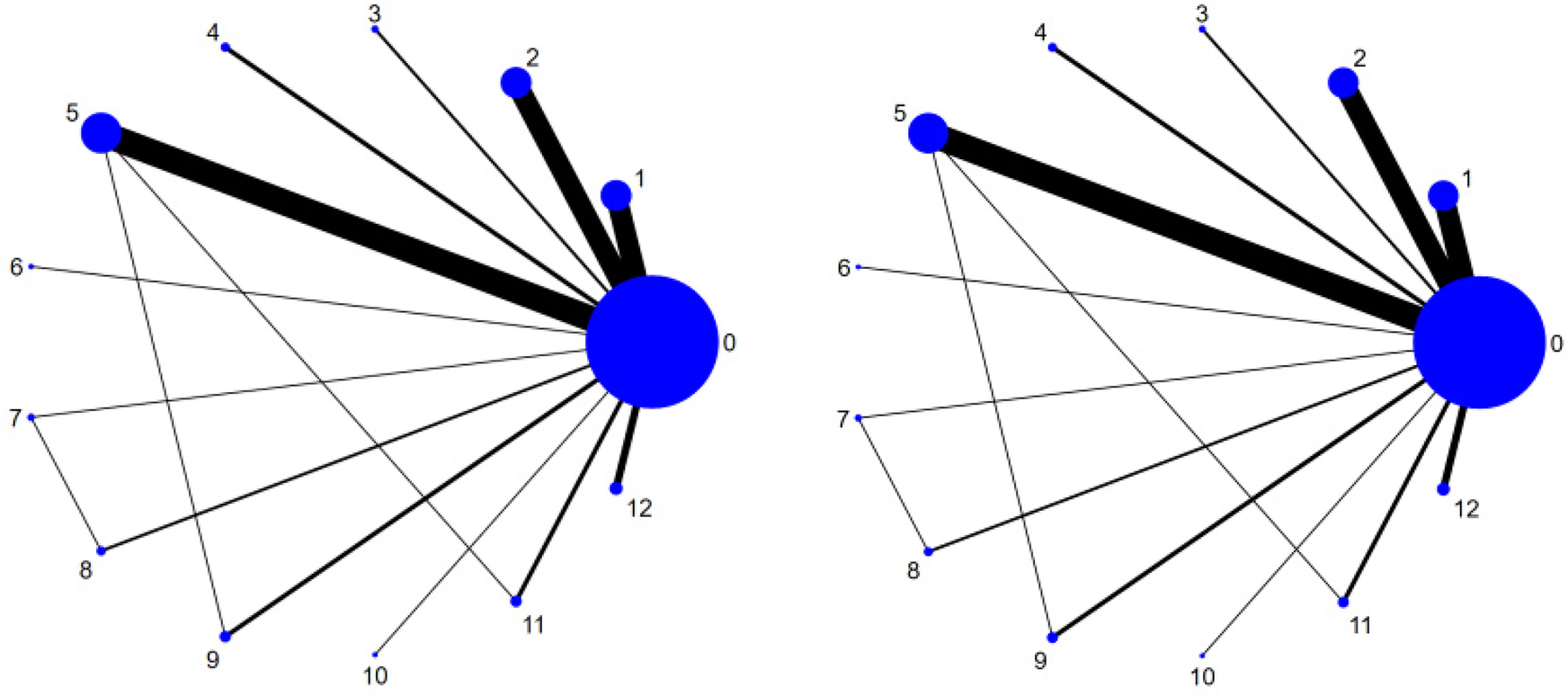

3.4 Evidence network

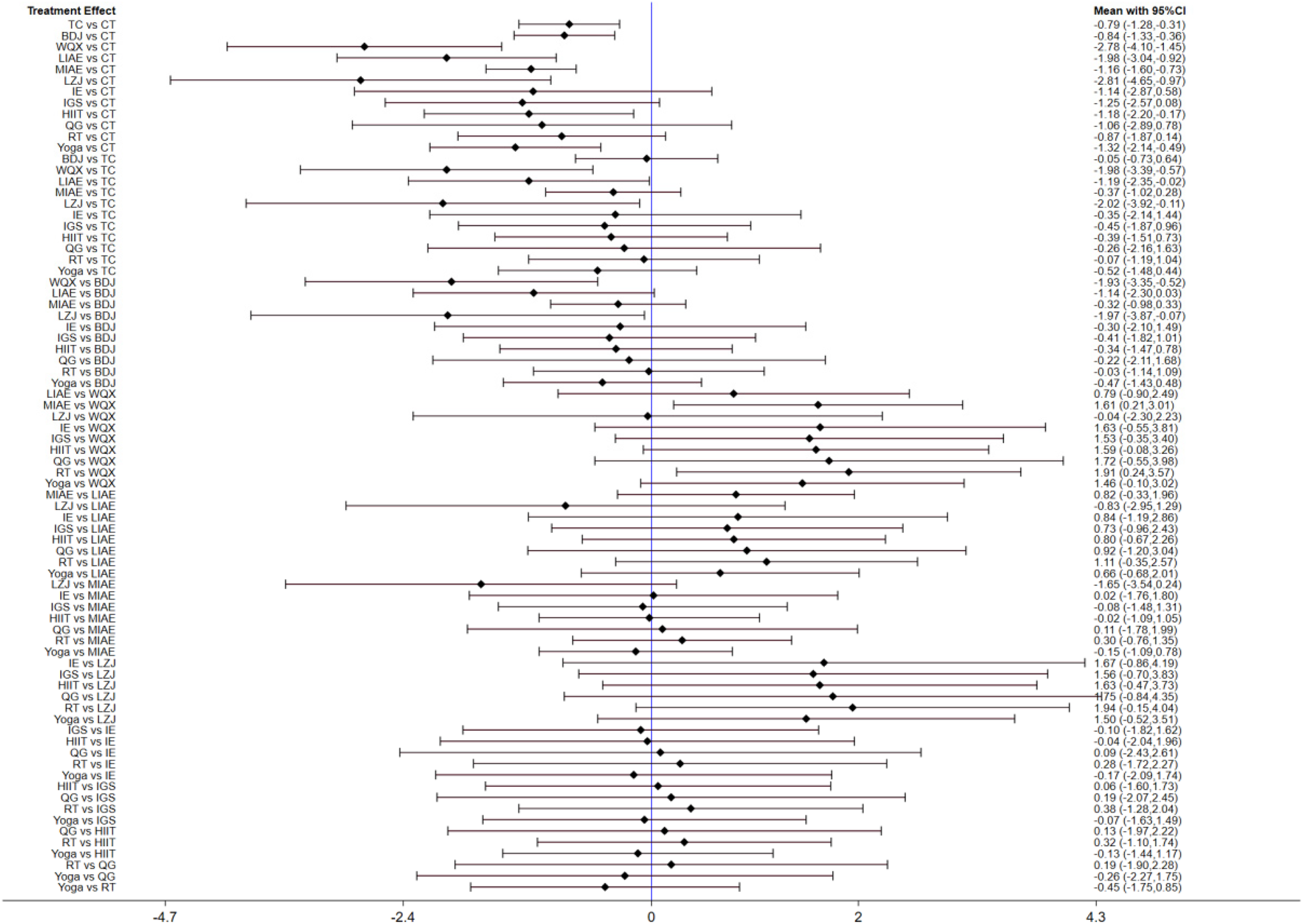

A total of 63 studies (14–76) and 12 intervention measures were included in the network meta-analysis. The network diagram is shown as follows. The inconsistency test indicates good consistency (p > 0.05), and the consistency test model was adopted for statistical analysis. In the figure, the circles represent the intervention measures, and the diameter is positively correlated with the included sample size; the connecting lines represent that there is a direct comparison between the two intervention measures. The thicker the straight line between the two points, the larger the number of relevant RCTs, as shown in Figure 3. The visualization forest plot is shown in Figures 4, 5.

Figure 3

Network map.

Figure 4

SBP forest plot. The left image is the Network Map of SBP, and the right image is the Network Map of DBP. The corresponding labels are: (0) CT; (1) TC; (2) BDJ; (3) WQX; (4) LIAE; (5) MIAE; (6) LZJ; (7) IE; (8) IGS; (9) HIIT; (10) QG; (11) RT; (12) Yoga.

Figure 5

DBP forest plot.

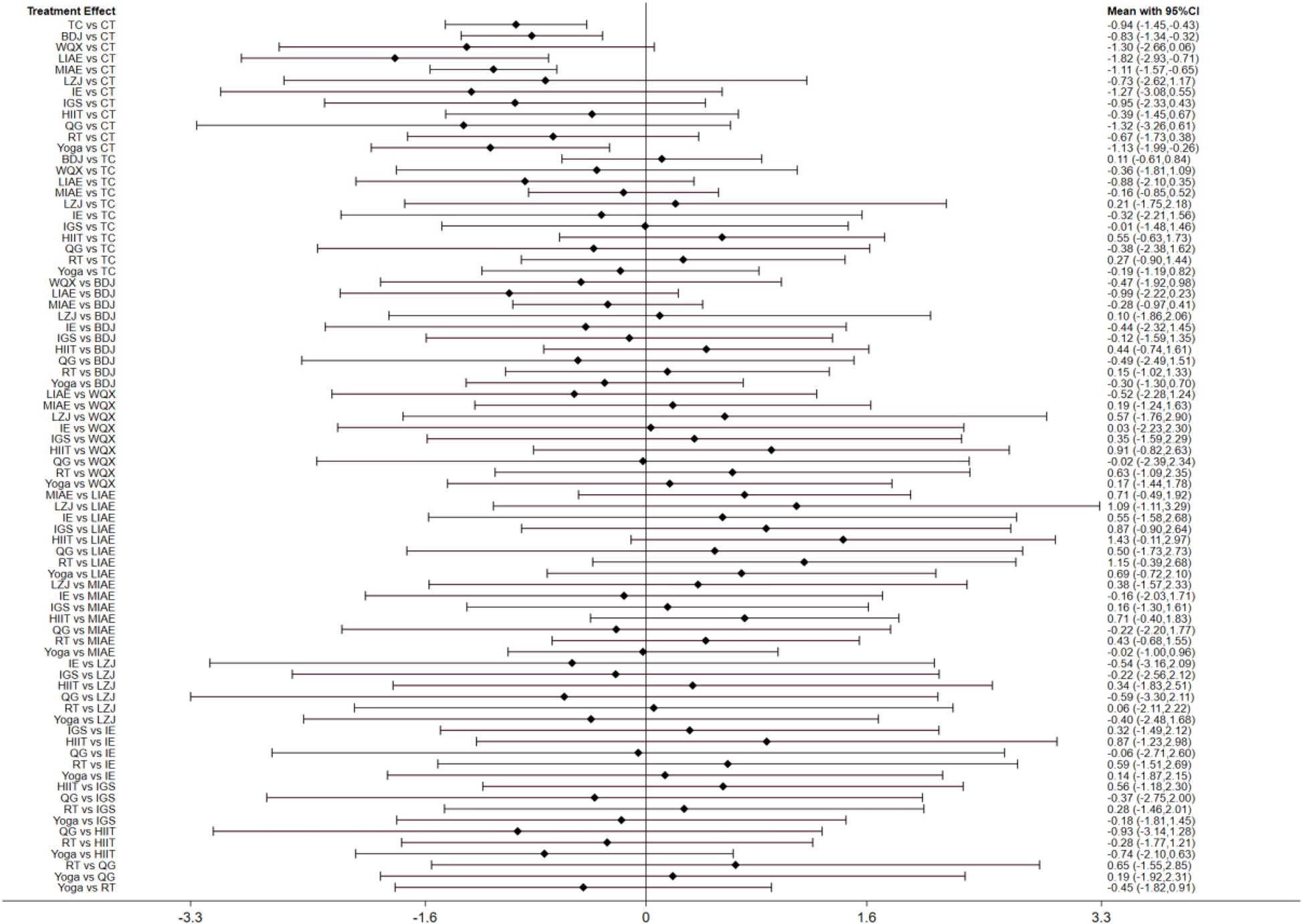

3.5 Network meta-analysis

3.5.1 SBP

A total of 63 studies (14–76) reported the results of SBP. Through network meta-analysis, CT + TC [weighted mean difference (WMD) = −0.94, 95%CI (−1.45, −0.43)], CT + BDJ [WMD = −0.83, 95% CI(−1.34, −0.32)], CT + LIAE [WMD = −1.82, 95% CI(−2.93, −0.71)], CT + MIAE [WMD = −1.11, 95% CI(−1.57, −0.65)], CT + Yoga [WMD = −1.13, 95% CI(−1.99, −0.26)] were significantly superior to the control group which only used antihypertensive drugs or nursing measures to reduce SBP. However, as shown in Table 3, there was no statistical significance among other intervention measures.

Table 3

| Intervention measures | MD [95%CI] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | TC | BDJ | WQX | LIAE | MIAE | LZJ | IE | IGS | HIIT | QG | RT | Yoga | |

| CON | 0 | ||||||||||||

| TC | −0.94 [−1.45, −0.43] | 0 | |||||||||||

| BDJ | −0.83 [−1.34, −0.32] | 0.11 [−0.61, 0.84] | 0 | ||||||||||

| WQX | −1.3[−2.66, 0.06] | −0.36 [−1.81, 1.09] | −0.47 [−1.92, 0.98] | 0 | |||||||||

| LIAE | −1.82 [−2.93, −0.71] | −0.88 [−2.1,0.35] | −0.99 [−2.22, 0.23] | −0.52 [−2.28, 1.24] | 0 | ||||||||

| MIAE | −1.11 [−1.57 , −0.65] | −0.16 [−0.85, 0.52] | −0.28 [−0.97, 0.41] | 0.19 [−1.24, 1.63] | 0.71 [−0.49, 1.92] | 0 | |||||||

| LZJ | −0.73 [−2.62, 1.17] | 0.21 [−1.75, 2.18] | 0.1 [−1.86, 2.06] | 0.57 [−1.76, 2.9] | 1.09 [−1.11, 3.29] | 0.38 [−1.57, 2.33] | 0 | ||||||

| IE | −1.27 [−3.08, 0.55] | −0.32 [−2.21, 1.56] | −0.44 [−2.32, 1.45] | 0.03 [−2.23, 2.3] | 0.55 [−1.58, 2.68] | −0.16 [−2.03, 1.71] | −0.54 [−3.16,2.09] | 0 | |||||

| IGS | −0.95 [−2.33, 0.43] | −0.01 [−1.48, 1.46] | −0.12 [−1.59, 1.35] | 0.35[−1.59, 2.29] | 0.87 [−0.9, 2.64] | 0.16 [−1.3, 1.61] | −0.22 [−2.56, 2.12] | 0.32 [−1.49, 2.12] | 0 | ||||

| HIIT | −0.39 [−1.45, 0.67] | 0.55 [−0.63, 1.73] | 0.44 [−0.74, 1.61] | 0.91 [−0.82, 2.63] | 1.43 [−0.11 ,2.97] | 0.71 [−0.4, 1.83] | 0.34 [−1.83, 2.51] | 0.87 [−1.23, 2.98] | 0.56 [−1.18, 2.3] | 0 | |||

| QG | −1.32 [−3.26, 0.61] | −0.38 [−2.38, 1.62] | −0.49 [−2.49, 1.51] | −0.02 [−2.39, 2.34] | 0.5 [−1.73, 2.73] | −0.22 [−2.2, 1.77] | −0.59 [−3.3, 2.11] | −0.06 [−2.71, 2.6] | −0.37 [−2.75, 2] | −0.93 [−3.14, 1.28] | 0 | ||

| RT | −0.67 [−1.73, 0.38] | 0.27 [−0.9, 1.44] | 0.15 [−1.02, 1.33] | 0.63 [−1.09, 2.35] | 1.15 [−0.39, 2.68] | 0.43 [−0.68, 1.55] | 0.06 [−2.11, 2.22] | 0.59 [−1.51, 2.69] | 0.28 [−1.46, 2.01] | −0.28 [−1 .77, 1.21] | 0.65 [−1.55, 2.85] | 0 | |

| Yoga | −1.13 [−1.99, −0.26] | −0.19 [−1.19, 0.82] | −0.3 [−1.3, 0.7] | 0.17 [−1.44, 1.78] | 0.69 [−0.72, 2.1] | −0.02 [−1, 0.96] | −0.4 [−2.48, 1.68] | 0.14 [−1.87, 2.15] | −0.18 [−1.81, 1.45] | −0.74 [−2.1, 0.63] | 0.19 [−1.92, 2.31] | −0.45 [−1.82, 0.91] | 0 |

Shows the comparison results of different types of exercise therapies in reducing SBP.

The results in bold black font indicate that the pairwise comparison results are statistically significant.

3.5.2 DBP

A total of 63 studies (14–76) reported the results of DBP. Through network meta-analysis, compared with traditional antihypertensive drugs and nursing education, etc., CT + TC [WMD = −0.79, 95%CI (−1.28, −0.31)], CT + BDJ [WMD = −0.84, 95% CI(−1.33, −0.36)], CT + WQX [WMD = −2.78, 95% CI(−4.1, −1.45)], CT + LIAE [WMD = −1.98, 95% CI(−3.04, −0.92)], CT + MIAE [WMD = −1.16, 95% CI(−1.6, −0.73)], CT + HIIT [WMD = −1.18, 95% CI(−2.2, −0.17)], CT + Yoga [WMD = −1.32, 95% CI(−2.14, −0.49)] could more significantly reduce DBP. As shown in Table 4, there was no statistical difference between other intervention methods and the control group.

Table 4

| Intervention measures | MD[95%CI] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | TC | BDJ | WQX | LIAE | MIAE | LZJ | IE | IGS | HIIT | QG | RT | Yoga | |

| CON | 0 | ||||||||||||

| TC | −0.79 [−1.28, −0.31 ] | 0 | |||||||||||

| BDJ | −0.84 [−1.33, −0.36] | −0.05 [−0.73, 0.64] | 0 | ||||||||||

| WQX | −2.78 [−4.1, −1.45] | −1.98 [−3.39, −0.57] | −1.93 [−3.35, −0.52] | 0 | |||||||||

| LIAE | −1.98 [−3.04, −0.92] | −1.19 [−2.35, −0.02] | −1.14 [−2.3, 0.03] | 0.79 [−0.9, 2.49] | 0 | ||||||||

| MIAE | −1.16 [−1.6, −0.73] | −0.37 [−1.02, 0.28] | −0.32 [−0.98, 0.33] | 1.61 [0.21, 3.01] | 0.82 [−0.33, 1.96] | 0 | |||||||

| LZJ | −2.81[−4.65, −0.97] | −2.02 [−3.92, −0.11] | −1.97 [−3.87, −0.07] | −0.04 [−2.3, 2.23] | −0.83 [−2.95, 1.29] | −1.65 [−3.54, 0.24] | 0 | ||||||

| IE | −1.14 [−2.87, 0.58] | −0.35 [−2.14, 1.44] | −0.3 [−2.1, 1.49] | 1.63 [−0.55, 3.81] | 0.84 [−1.19, 2.86] | 0.02 [−1.76, 1.8] | 1.67 [−0.86, 4.19] | 0 | |||||

| IGS | −1.25 [−2.57, 0.08] | −0.45 [−1.87, 0.96] | −0.41 [−1.82, 1.01] | 1.53[−0.35, 3.4] | 0.73 [−0.96, 2.43] | −0.08 [−1.48, 1.31] | 1.56 [−0.7, 3.83] | −0.1 [−1.82, 1.62] | 0 | ||||

| HIIT | −1.18 [−2.2, −0.17] | −0.39 [−1.51, 0.73] | −0.34 [−1.47, 0.78] | 1.59 [−0.08, 3.26] | 0.8 [−0.67, 2.26] | −0.02 [−1.09, 1.05] | 1.63 [−0.47, 3.73] | −0.04 [−2.04, 1.96] | 0.06 [−1.6, 1.73] | 0 | |||

| QG | −1.06 [−2.89, 0.78] | −0.26 [−2.16, 1.63] | −0.22 [−2.11, 1.68] | 1.72 [−0.55, 3.98] | 0.92 [−1.2, 3.04] | 0.11 [−1.78, 1.99] | 1.75 [−0.84, 4.35] | 0.09 [−2.43, 2.61] | 0.19 [−2.07, 2.45] | 0.13 [−1.97, 2.22] | 0 | ||

| RT | −0.87 [−1.87, 0.14] | −0.07 [−1.19, 1.04] | −0.03 [−1.14, 1.09] | 1.91 [0.24, 3.57] | 1.11 [−0.35, 2.57] | 0.3 [−0.76, 1.35] | 1.94 [−0.15, 4.04] | 0.28 [−1.72, 2.27] | 0.38 [−1.28, 2.04] | 0.32 [−1.1, 1.74] | 0.19 [−1.9, 2.28] | 0 | |

| Yoga | −1.32[−2.14, −0.49] | −0.52 [−1.48, 0.44] | −0.47 [−1.43, 0.48] | 1.46 [−0.1, 3.02] | 0.66 [−0.68, 2.01] | −0.15 [−1.09, 0.78] | 1.5 [−0.52,3.51] | −0.17 [−2.09, 1.74] | −0.07 [−1.63, 1.49] | −0.13 [−1.44, 1.17] | −0.26 [−2.27, 1.75] | −0.45 [−1.75, 0.85] | 0 |

Shows the comparison results of different types of exercise therapies in reducing DBP.

The results in bold black font indicate that the pairwise comparison results are statistically significant.

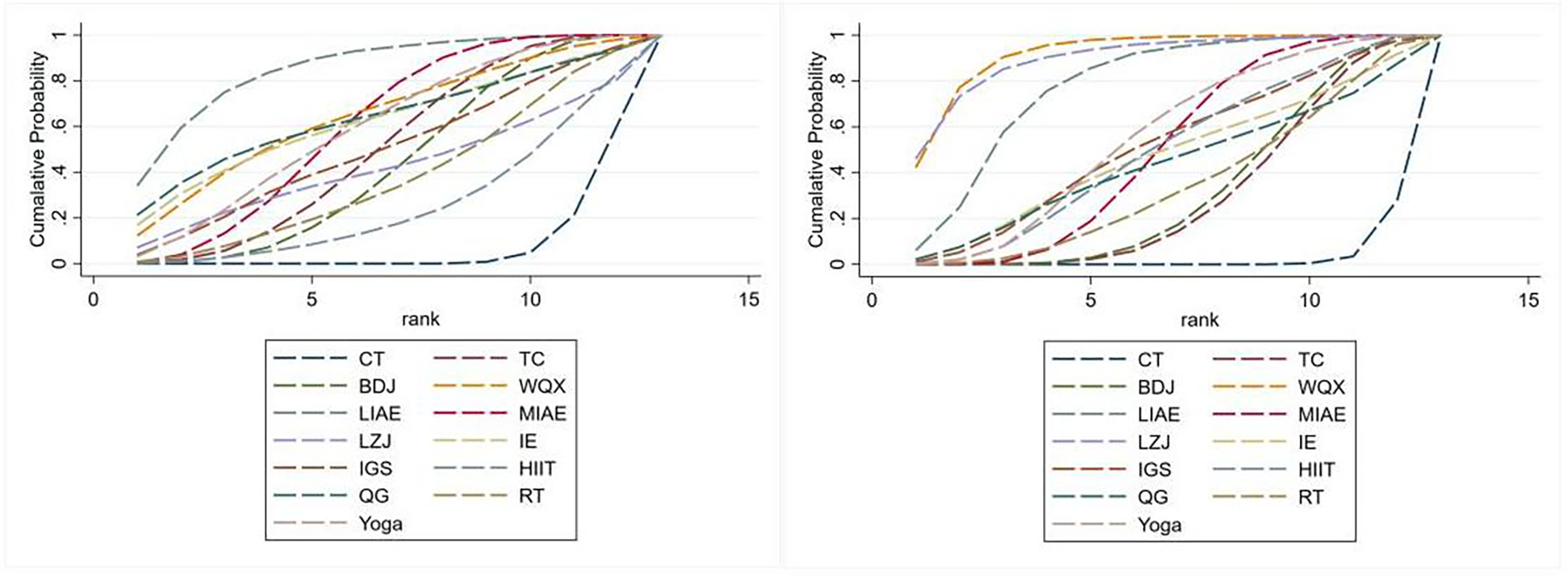

3.5.3 SUCRA ranking

We ranked different exercise therapies according to the results calculated by SUCRA. The SUCRA probability ranking results of different intervention measures in reducing SBP showed that in terms of reducing SBP, LIAE + CT (SUCRA = 85.3%)>MIAE + CT(SUCRA = 60%)>Yoga + CT(SUCRA = 59.6%)>TC + CT(SUCRA = 50.1%)>BDJ + CT(SUCRA = 43.4%)>CT (SUCRA = 7.3%), and other intervention measures had no statistical significance; in terms of reducing DBP, WQX + CT(SUCRA = 91.8%)>LZJ + CT(SUCRA = 89.8%)>LIAE + CT(SUCRA = 77.6%)> Yoga + CT(SUCRA = 54.8%)>MIAE + CT(SUCRA = 49.3%)>HIIT + CT (SUCRA = 48.8%)>BDJ + CT(SUCRA = 31.4%)>TC + CT(SUCRA = 29.4%)>CT (SUCRA = 2.7%), and other intervention measures had no statistical significance See Figure 6 for details.

Figure 6

SUCRA ranking.

3.6 Meta-regression

Considering the differences in the types of control groups among the included studies, we conducted a meta-regression analysis to assess their potential impact on the blood pressure-lowering effect. The results of the meta-regression analysis showed that different control types did not affect the systolic blood pressure-lowering effect (P = 0.892 > 0.05); nor did different control types affect the diastolic blood pressure-lowering effect (P = 0.675 > 0.05).

3.7 Sensitivity analysis

To explore the source of heterogeneity, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding individual studies one by one, and the results are detailed in Supplementary Material 1. Consistent with the results of the initial analysis, excluding a single study had little impact on the combined results, which indicates that the combined effect size results of this study are more stable.

3.8 Inconsistency test

Both the network diagrams of SBP and DBP have closed loops. Therefore, a local inconsistency test is required. The results showed that there was no significant difference between the direct and indirect analyses of the network analysis for both SBP and DBP (P > 0.05), indicating good consistency.

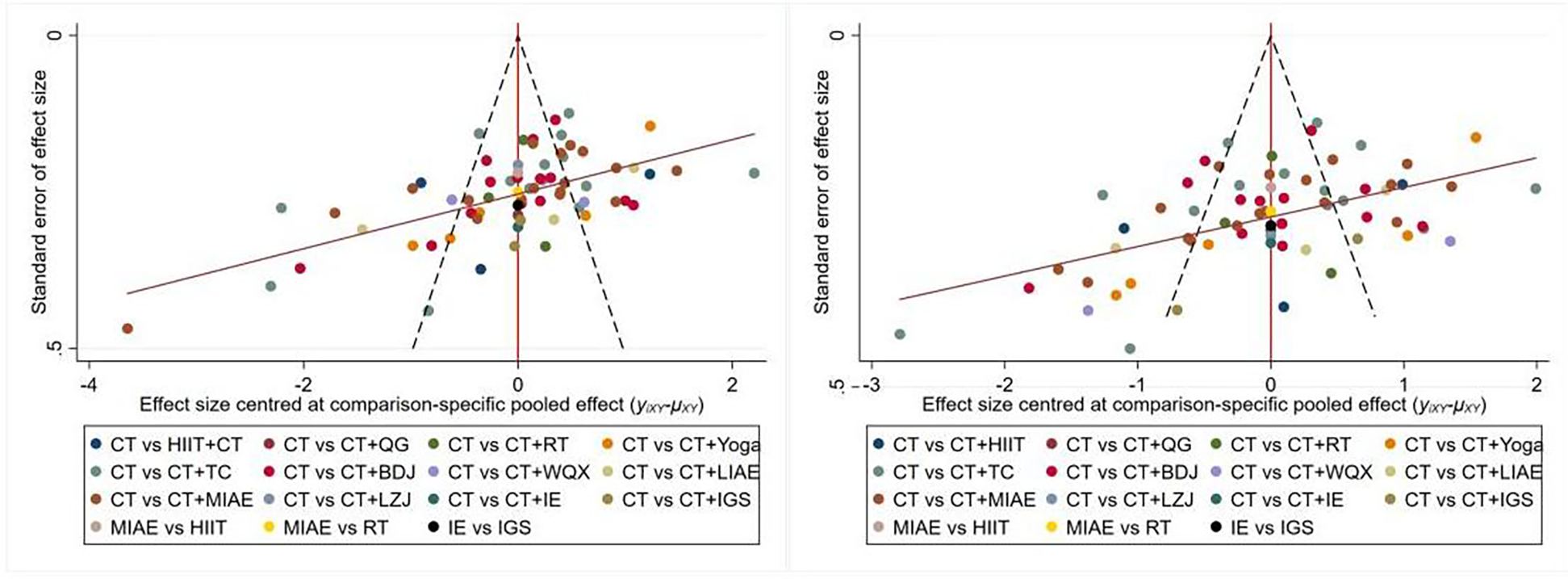

3.9 Publication bias

The Stata15.0 software was used to draw the comparison-corrected funnel plots for different outcome indicators, as shown in Figure 7. The results showed that the scatter distributions of each comparison group in the figure were different. Most of the scatter points were distributed on both sides of the vertical line of X = 0, but there were differences in the degree of symmetry, and many literatures deviated from the axis. The results of Egger's test showed that (for SBP, P < 0.05; for DBP, P < 0.05), indicating that there was a certain publication bias in the included literatures.

Figure 7

Bias-specific pooled effect.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary

In recent years, numerous epidemiological studies have linked hypertension to higher risks of stroke, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure (13). Meanwhile, hypertension prevalence in China has risen annually, with a more notable upward trend among young people and in rural areas. Though awareness of hypertension has improved among Chinese patients, it remains relatively low overall (12). Studies confirm active exercise intervention effectively maintains and lowers blood pressure. Thus, the latest hypertension guidelines widely recommend exercise therapies—primarily aerobic and resistance exercise—for hypertension prevention and treatment (7, 12). Specifically, aerobic exercise can reduce adult blood pressure by 5–7 mmHg, while resistance training has an even better blood pressure-lowering effect (10). Aerobic exercise of all intensities works, but many struggle to stick with it long-term due to poor baseline fitness, overly long training sessions, or environmental factors (77).

Currently, traditional exercises (Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Wuqinxi, Liuzijue) are widely used in hypertension management, with clinical studies verifying their good blood pressure-lowering effects (78). This article compares the efficacy of different exercise therapies (aerobic, resistance, yoga, traditional exercises) in hypertension patients. It included 63 RCTs (total sample: 5,663 cases; 2,826 in experimental group, 2,837 in control group) and evaluated 12 exercise therapies. Results showed combinations like TC + CT, BDJ + CT, LIAE + CT, MIAE + CT, WQX + CT, LZJ + CT, HIIT + CT, and Yoga + CT had the best effects—LIAE + CT was most effective for SBP reduction, and WQX + CT for DBP reduction.

In this article, various types of exercise therapies are mentioned. Among them, common types such as low-intensity aerobic exercise are characterized by low exercise intensity, with the heart rate being approximately 60%–70% of the maximum heart rate. It mainly relies on aerobic metabolism for energy supply, has a long duration, and is highly safe. Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise has the characteristics of moderate intensity, with the heart rate reaching 70%–85% of the maximum heart rate. It is supplied with energy through a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism and poses a certain challenge. Resistance exercise, through means such as equipment, elastic bands, or one's own body weight, resists resistance. It can increase muscle mass, enhance strength, and improve metabolism, etc. In addition to these more well-known exercises, some traditional exercises have gradually been widely applied in clinical diagnosis and treatment. Among them, Wuqinxi was created by Hua Tuo, a famous traditional Chinese medicine doctor in China. Its movements are derived from tigers, deer, bears, apes, and birds in nature. Practicing Wuqinxi can mobilize the muscles and bones, dredge the qi and blood, prevent and treat diseases. The strength, speed, and other aspects of its choreographed movements conform to the characteristics of aerobic exercise, but attention also needs to be paid to the regulation of form, spirit, intention, and qi, etc. (79). Tai Chi, as one of the most widely spread traditional exercises, is not a single type of exercise. Instead, it combines the rotation and movement of the human body, following the law of “force originates from the ground and strength is generated from the root”. It can exercise the heart and lungs, move the joints, and is helpful for the control of blood pressure (80, 81).

4.2 Prospects

Studies have shown that exercise therapy has a wide range of applicable populations and no toxic or side effects. Notably, it acts on multiple systems simultaneously—including the cardiovascular, metabolic, nervous, and musculoskeletal systems—meaning it not only delays the progression of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and arteriosclerosis, but also reduces the risk of cardiovascular events (9, 11, 82).

Building on this understanding of its benefits, the currently known specific mechanisms linking exercise therapy to hypertension prevention and treatment include: promoting the release of nitric oxide (NO), reducing endothelin-1 (ET-1) concentration to improve vascular function; inhibiting sympathetic nerve activity and regulating the renin-angiotensin system; reducing body weight and improving metabolism; and alleviating inflammatory responses (78, 84). However, the specific and complex microscopic mechanisms behind its blood pressure-lowering effect remain unclear. For instance, the differential ways in which different exercise types (such as traditional Chinese exercises and high-intensity interval training) regulate vascular endothelial function and neuroendocrine pathways, as well as the quantitative correlation between exercise intensity, duration, and blood pressure-lowering effect, have yet to form a systematic conclusion.

To address this gap, future research should proceed across three key dimensions. First, in clinical trials, researchers need to further verify the blood pressure-lowering effects of different exercise therapies through randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods. Crucially, a quantitative model should be established by linking quantifiable indicators—such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing results, inflammatory factors, and vascular endothelial factors—to blood pressure-lowering effects. This model will help analyze the exercise prescription thresholds for patients with different types of hypertension. Second, in basic research, animal and cell experiments can be used to explore the microscopic mechanisms of exercise intervention in lowering blood pressure. Specifically, these experiments can analyze the molecular regulatory networks through which exercise acts on vascular smooth muscle cells and myocardial cells, filling the current gap in microscopic mechanism research. Finally, in future clinical applications, promoting the popularization of heart rate monitoring devices (such as smart bracelets) will enable precise regulation of exercise programs. At the same time, it is necessary to explore the optimal combined programs of exercise therapy with other lifestyle interventions (such as diet adjustment) to further improve patient compliance. Collectively, these future prospects will not only refine the basic theoretical system of exercise therapy but also provide more operable clinical strategies for hypertension prevention and treatment—ultimately reducing the social burden of the disease.

4.3 Advantages and limitations of the study

In previous related studies, researchers often focused on comparing exercise modes with different intensities or different training methods, or only focused on traditional Chinese exercises while ignoring the overall concept of exercise therapy. For the first time, this article adopts the overall perspective of exercise therapy to conduct a comprehensive and systematic summary and comparison of various exercise therapies, including aerobic exercise of different intensities, resistance training, yoga, and traditional Chinese exercises. A total of 63 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the study, and for the first time, studies related to low-intensity aerobic exercise were incorporated, aiming to provide a basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment. On the other hand, the primary outcome indicator of this article is ABPM, which can assess the changing trends and short-term variability of patients' blood pressure under different environments, body positions, and emotional states (83). The ESC Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension points out that ABPM is capable of diagnosing special hypertension phenotypes such as nocturnal hypertension, transient hypotension, and post-exercise hypertension, as well as identifying white-coat hypertension and masked hypertension (7). Compared with office blood pressure, ABPM has higher specificity and can predict cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events and mortality more accurately (83). Finally, strict screening was carried out for the included literatures in this article, ensuring the quality of the included literatures and enhancing the credibility of the article.

The limitations of this article are as follows. First, publication bias is relatively obvious: all included studies show positive results, but unpublished negative results cannot be ruled out, which may affect the study's reliability. Second, some exercise types have relatively few studies and small sample sizes, requiring further verification. Third, double blinding is difficult to achieve in exercise therapy-related RCTs; inconsistencies in included studies (such as hypertension levels and medication use) have also affected the reliability and accuracy of results to some extent. Fourth, the primary outcome indicator is ABPM. Compared with office blood pressure measurement, ABPM is more costly and may disrupt patients' sleep quality, reducing compliance. Finally, this article did not include studies on combined exercises or direct comparisons of different exercises, which may have impacted the results.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, network analysis results confirm that exercise therapy can significantly reduce 24-hour average blood pressure. Notably, both conventional exercise training (such as aerobic exercise of different intensities, resistance training, etc.) and traditional Chinese exercises (such as Tai Chi, Baduanjin, etc.) exhibit good blood pressure-lowering effects for hypertension patients. Crucially, the conclusions of this study hold practical reference value for clinical application: medical workers can formulate individualized exercise prescriptions based on patients’ specific conditions. For instance, low-intensity aerobic exercise or Tai Chi may be selected for elderly patients or those with poor baseline physical fitness; moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or resistance training can be adopted for young patients or those with good physical fitness; and for patients with other comorbid basic diseases (such as obesity), fat reduction training can be incorporated and combined with lifestyle interventions like dietary adjustment. Through this tailored approach, long-term individualized exercise prescription management for hypertension patients can be effectively ensured. It is worth noting, however, that due to the limitations in the quality and quantity of the included studies, these conclusions still require further verification through high-quality clinical trials.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SY: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors of this article declare that this article is supported by two funds: “Project of the National Key Research and Development Program: Technologies for Patient Discharge Assessment and Continuous Out-of-Hospital Care, 2021ZD0111003” and “Project for the Construction of “Flagship” Department of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine in Beijing, PM202405280003”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1604112/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Kearney PM Whelton M Reynolds K Muntner P Whelton PK He J . Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. (2005) 365(9455):217–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1

2.

Mills KT Bundy JD Kelly TN Reed JE Kearney PM Reynolds K et al Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. (2016) 134(6):441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912

3.

GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392(10159):1923–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6

4.

Reinhart M Puil L Salzwedel DM Wright JM . First-line diuretics versus other classes of antihypertensive drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2023) 7(7):CD008161. 10.1002/14651858.CD008161.pub3

5.

Messerli FH Williams B Ritz E . Essential hypertension. Lancet. (2007) 370(9587):591–603. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61299-9

6.

Fletcher GF Landolfo C Niebauer J Ozemek C Arena R Lavie CJ . Promoting physical activity and exercise: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72(14):1622–39. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2141

7.

McEvoy JW McCarthy CP Bruno RM Brouwers S Canavan MD Ceconi C et al 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(38):3912–4018. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae178. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2025 46(14):1300. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf031.

8.

Cornelissen VA Fagard RH . Effects of endurance training on blood pressure, blood pressure-regulating mechanisms, and cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension. (2005) 46(4):667–75. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000184225.05629.51

9.

Lavie CJ Ozemek C Carbone S Katzmarzyk PT Blair SN . Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. (2019) 124(5):799–815. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312669

10.

MacDonald HV Johnson BT Huedo-Medina TB Livingston J Forsyth KC Kraemer WJ et al Dynamic resistance training as stand-alone antihypertensive lifestyle therapy: a meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. (2016) 5(10):e003231. 10.1161/JAHA.116.003231

11.

Dai L Jiang Y Wang P Chen K . Effects of three traditional Chinese fitness exercises combined with antihypertensive drugs on patients with essential hypertension: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2021) 2021:2570472. 10.1155/2021/2570472

12.

Revision Committee of Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension, Hypertension League (China), Hypertension Branch of China International Exchange and Promotion Association for Medical and Healthcare, etc.Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of hypertension (2024 revised edition). Chin J Hypertens. (2024) 32(07):603–700.

13.

Lewington S Clarke R Qizilbash N Peto R Collins R , Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. (2002) 360(9349):1903–13. 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8

14.

Chunling D Yali Z . Application of “blood pressure lowering baduanjin” in blood pressure control of middle-aged patients with grade I essential hypertension. Mil Nurs. (2016) 33(20):32–5. CNKI:SUN:JFHL.0.2016-20-011

15.

Qinghua H Youling Q Xiaoli L Huan Z Jiewen X . Effects and mechanism of 12-week tai chi exercise on microvascular reactivity in middle-aged and elderly patients with mild hypertension. Chin J Appl Physiol. (2021) 37(6):683–7.

16.

Huan X . Effects of the 24-style simplified tai chi on blood pressure and quality of life of patients with hypertension. Hubei J Trad Chin Med. (2016) 38(7):38–9. CNKI:SUN:HBZZ.0.2016-07-018

17.

Xiaobin W Luping Y . Influence of the 24-style simplified tai chi on elderly patients with essential hypertension complicated with mild anxiety state. Fujian J Trad Chin Med. (2019) 50(4):73–5. 10.13260/j.cnki.jfjtcm.011881

18.

Lijuan F Li G Dailiang Z Zhongchen L Mengxiao L Rongjiang J et al Clinical evaluation of the antihypertensive effect and blood lipid level of the 24-style tai chi in elderly patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Convale Med. (2018) 27(10):1009–13. 10.13517/j.cnki.ccm.2018.10.001

19.

Yujie Z . Influence of baduanjin exercise on blood pressure control, psychological state and sleep quality of elderly patients with hypertension. China Sci Technol J Database Med. (2023) 5:1–4.

20.

Fang L Qiongxia H . Efficacy observation of baduanjin exercise in the treatment of grade 1 hypertension in the elderly. Chi J Geriatr Care. (2014) 3:25–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-4860.2014.03.009

21.

Hongyu L Chuyan H Dianhong L . Effects of baduanjin on blood pressure and quality of life of patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Rehabil Trad Chin Med. (2016) 7(16):12–4, 15.

22.

Hui C Yana Z . Effects of baduanjin on blood pressure and Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Rehabil Med. (2012) 27(2):178–9. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2012.02.023

23.

Chen C . Effect analysis of baduanjin combined with health education intervention on middle-aged and elderly patients with hypertension. Jiangxi J Trad Chin Med. (2021) 52(12):40–1, 60.

24.

Liwei Z Qingyue C Feng C Lijuan M Jianxing Z . Effects of baduanjin exercise on vascular endothelial function of elderly patients with grade 1 hypertension. Chin J Rehabil Med. (2014) 29(3):223–7.

25.

Yunhua L Seqing L Chunlei H Hong W Ying P . Effects of baduanjin exercise intervention on blood pressure and blood lipids of patients with essential hypertension. Henan Trad Chin Med. (2014) 34(12):2380–1. 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2014.12.102

26.

Zhanmei H Xia W Linhong Z Suyun H Dan P Ziyu Z . Observation on the application effect of baduanjin in the health management of patients with grade 1 hypertension. Jiangxi J Trad Chin Med. (2021) 52(11):34–7. CNKI:SUN:JXZY.0.2021-11-013

27.

Yakang X . Effects of the eight-style taijiquan exercise on blood pressure level, vascular endothelial function and quality of life of patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Gerontol. (2018) 38(10):2403–5. CNKI:SUN:ZLXZ.0.2018-10-043

28.

Jingyuan L . Comparative analysis of the therapeutic effects of different exercise methods on elderly patients with essential hypertension. Guide China Med. (2019) 17(12):141–2. 10.15912/j.cnki.gocm.2019.12.107

29.

Chunli Y . Effects of low-intensity exercise therapy combined with health education on the quality of life and blood pressure of elderly patients with hypertension. Chin Gen Pract Nurs. (2015) 13(17):1591–3. CNKI:SUN:JTHS.0.2015-17-005

30.

Peijing H . Evaluation of the effects of low-intensity exercise therapy combined with health education on the quality of life and blood pressure of elderly patients with hypertension. Prevent Treat Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 10(17):59–61. CNKI:SUN:XUGB.0.2020-17-020

31.

Yingxian Z . Effects of low-intensity exercise therapy combined with health education on the blood pressure self-control level and quality of life of elderly patients with essential hypertension. J Mod Med Health. (2020) 36(3):433–5. CNKI:SUN:XYWS.0.2020-03-038

32.

Linghua S Ting J Fang M Xiaohua T . Application analysis of high-intensity interval training combined with progressive relaxation training in patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Trauma Disabil Med. (2024) 32(17):139–42. 10.13214/j.cnki.cjotadm.2024.017.037

33.

Lei G Lin P Mingming Z Yanjuan F . Study on the therapeutic effect of personalized exercise rehabilitation prescription on patients with grade 1 hypertension. Chin J Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 27(4):361–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-5410.2022.04.010

34.

Lixun H Jianquan Y . Effects of brisk walking combined with taijiquan on blood pressure, blood glucose and blood lipids of elderly patients with hypertension. Hainan Med J. (2015) 14:2053–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2015.14.0742

35.

Qiu L Xinghui Y . Promoting effect of the fitness baduanjin on the rehabilitation of elderly patients with hypertension. Chin J Gerontol. (2017) 37(12):3024–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2017.12.075

36.

Jian C . Effects of resistance training on the autonomic nervous function of patients with hypertension. Shandong Sports Sci Technol. (2014) 36(5):83–6. 10.14105/j.cnki.1009-9840.2014.05.020

37.

Na Z . Effects of resistance training on blood pressure and lipid metabolism of patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Cardiovasc Rehabil Med. (2018) 27(5):498–501. CNKI:SUN:XXGK.0.2018-05-002

38.

Xue H . Rehabilitation efficacy of baduanjin exercise for elderly patients with hypertension. Chin J Cardiovasc Rehabil Med. (2015) 24(3):252–4.

39.

Xiaoduo Z Bin D Zhijian P . Clinical observation of the six-character chanting breathing method in the treatment of hypertension complicated with anxiety and depression. Chin Med Mod Distance Educ China. (2022) 20(23):37–40. CNKI:SUN:ZZYY.0.2022-23-016

40.

Sun J Buys N Yichen Q . Effects of community-based mind-body meditative taijiquan training on blood pressure, body weight, renal function, blood lipids and quality of life of Chinese patients with hypertension. Chin J Hypertens. (2016) 24(1):87–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.012

41.

Haolei J Jiajia P . Effects of taijiquan on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and vascular endothelial function of patients with grade 1 essential hypertension. Chin J Sports Med. (2016) 35(3):224–7.

42.

Yamei C Rong M Xuyan Z Qiaoyan W Fei W Jingjing W et al Application research of taijiquan techniques in the clinical treatment of elderly patients with essential hypertension. Hebei J Trad Chin Med. (2024) 46(1):69–72. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-2619.2024.01.016

43.

Hua L . Clinical study on the treatment of essential hypertension with taijiquan combined with medication. China Med Herald. (2006) 3(33):43–4.

44.

Tao L Qidong H Weizhong L . Effects of taijiquan exercise on blood pressure, hemorheology and long-term quality of life of elderly patients with hypertension. Chin J Gerontol. (2018) 38(6):1396–8.

45.

Wen L Hui L Hairong L . Intervention study on the effects of the five-animal exercises on blood pressure and obesity of elderly patients with hypertension. Med Inf. (2015) 9:48–9. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2015.09.062

46.

Huihui Z . Effects of the five-animal exercises on patients with essential hypertension. Med Diet Health. (2022) 20(11):186–8, 192.

47.

Jiangqin X Yujie S . Study on the influence of the five elements music therapy combined with taijiquan exercise on the blood pressure variability of elderly patients with essential hypertension. Cap Med. (2024) 31(4):122–4.

48.

Yong C Haiyan C Fu Z . Exercise intervention in the treatment of grade 1 hypertension in young and middle-aged people. Fujian J Trad Chin Med. (2016) 47(5):56–7.

49.

Yi Z . Observation on the application effect of exercise rehabilitation training in elderly patients with hypertension. Pract Clin J IntegrTrad Chin West Med. (2023) 23(01):50–3. 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2023.01.015

50.

Yanli Y . Influence of exercise therapy on patients with hypertension: a 2-year follow-up observation. Chin J Clin Rehabil. (2002) 6(21):3276–7. CNKI:SUN:XDKF.0.2002-21-122

51.

Tianming D . Evaluation of the effect of exercise therapy on ventricular remodeling in patients with hypertension. J Mod Clin Med. (2017) 43(5):335–6, 339.

52.

Mengmeng S . Influence of exercise therapy on the therapeutic effect of hypertension. J Shandong Med Coll. (2019) 41(6):475–6.

53.

Xiaofang L Yongxin Z . Efficacy observation of exercise therapy in the treatment of hypertension. Chin J Rehabil Med. (2005) 20(11):823. CNKI:SUN:ZGKF.0.2005-11-006

54.

Minfang W . Discussion on the application of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise rehabilitation therapy in patients with essential hypertension. Prevent Treat Cardiovasc Dis. (2019) 0(17):8–10. CNKI:SUN:XUGB.0.2019-17-004

55.

Xiuling H . Application of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise as a rehabilitation treatment in patients with essential hypertension. Electron J Clin Med Lit. (2019) 6(7):72, 74. 10.16281/j.cnki.jocml.2019.07.065

56.

Qing M Ping Z . Application research of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise as a rehabilitation treatment in patients with essential hypertension. Cardiovasc Dis J Integr Trad Chin West Med. (2017) 5(26):57. 10.16282/j.cnki.cn11-9336/r.2017.26.041

57.

Yulong G . Application of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise as a rehabilitation treatment in patients with essential hypertension. Cardiovasc Dis J Integr Trad Chin West Med. (2016) 4(11):17–8. 10.16282/j.cnki.cn11-9336/r.2016.11.012

58.

Chan AWK Chair SY Lee DTF Leung DYP Sit JWH Cheng HY et al Tai chi exercise is more effective than brisk walking in reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors among adults with hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2018) 88:44–52. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.009

59.

Hou HY Chen J Hai L Wang P Zhang JX Li HJ . Effects of exergame and bicycle exercise intervention on blood pressure and executive function in older adults with hypertension: a three-group randomized controlled study. Exp Gerontol. (2023) 173:112099. 10.1016/j.exger.2023.112099

60.

Maruf FA Akinpelu AO Salako BL Akinyemi JO . Effects of aerobic dance training on blood pressure in individuals with uncontrolled hypertension on two antihypertensive drugs: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Hypertens. (2016) 10(4):336–45. 10.1016/j.jash.2016.02.002

61.

Ping W Qingling Z . Effects of taijiquan exercise on blood pressure, hemorheology and quality of life of elderly patients with hypertension. Healthy Women. (2023) 18:170–2.

62.

Kaiyong N . Application research of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise as a rehabilitation treatment for patients with essential hypertension. Longevity. (2024) 12:7–9.

63.

Cooper AR Moore LA McKenna J Riddoch CJ . What is the magnitude of blood pressure response to a programme of moderate intensity exercise? Randomised controlled trial among sedentary adults with unmedicated hypertension. Br J Gen Pract. (2000) 50(461):958–62.

64.

Cramer H Sellin C Schumann D Dobos G . Yoga in arterial hypertension. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2018) 115(50):833–9. 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0833

65.

Cohen DL Bloedon LT Rothman RL Farrar JT Galantino ML Volger S et al Iyengar yoga versus enhanced usual care on blood pressure in patients with prehypertension to stage I hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2011) 2011:546428. 10.1093/ecam/nep130

66.

Anjana K Archana R Mukkadan JK . Effect of om chanting and yoga nidra on blood pressure and lipid profile in hypertension—a randomized controlled trial. J Ayurveda Integr Med. (2022) 13(4):100657. 10.1016/j.jaim.2022.100657

67.

Molmen-Hansen HE Stolen T Tjonna AE Aamot IL Ekeberg IS Tyldum GA et al Aerobic interval training reduces blood pressure and improves myocardial function in hypertensive patients. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2012) 19(2):151–60. 10.1177/1741826711400512

68.

Gorostegi-Anduaga I Corres P MartinezAguirre-Betolaza A Pérez-Asenjo J Aispuru GR Fryer SM et al Effects of different aerobic exercise programmes with nutritional intervention in sedentary adults with overweight/obesity and hypertension: EXERDIET-HTA study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2018) 25(4):343–53. 10.1177/2047487317749956

69.

Chen D . Effect of health qigong mawangdui daoyinshu on blood pressure of individuals with essential hypertension. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2016) 64(7):1513–5. 10.1111/jgs.14218

70.

Xiao C Yang Y Zhuang Y . Effect of health qigong ba duan jin on blood pressure of individuals with essential hypertension. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2016) 64(1):211–3. 10.1111/jgs.13913

71.

Cohen DD Aroca-Martinez G Carreño-Robayo J Castañeda-Hernández A Herazo-Beltran Y Camacho PA et al Reductions in systolic blood pressure achieved by hypertensives with three isometric training sessions per week are maintained with a single session per week. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). (2023) 25(4):380–7. 10.1111/jch.14621

72.

Wolff M Rogers K Erdal B Chalmers JP Sundquist K Midlöv P . Impact of a short home-based yoga programme on blood pressure in patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial in primary care. J Hum Hypertens. (2016) 30(10):599–605. 10.1038/jhh.2015.123

73.

Punia S Kulandaivelan S . Home-based isometric handgrip training on RBP in hypertensive adults-partial preliminary findings from RCT. Physiother Res Int. (2020) 25(1):e1806. 10.1002/pri.1806

74.

Izadi MR Ghardashi Afousi A Asvadi Fard M Babaee Bigi MA . High-intensity interval training lowers blood pressure and improves apelin and NOx plasma levels in older treated hypertensive individuals. J Physiol Biochem. (2018) 74(1):47–55. 10.1007/s13105-017-0602-0

75.

Shou XL Wang L Jin XQ Zhu LY Ren AH Wang QN . Effect of t'ai chi exercise on hypertension in young and middle-aged in-service staff. J Altern Complement Med. (2019) 25(1):73–8. 10.1089/acm.2018.0011

76.

McCaffrey R Ruknui P Hatthakit U Kasetsomboon P . The effects of yoga on hypertensive persons in Thailand. Holist Nurs Pract. (2005) 19(4):173–80. 10.1097/00004650-200507000-00009

77.

Lopes S Félix G Mesquita-Bastos J Figueiredo D Oliveira J Ribeiro F . Determinants of exercise adherence and maintenance among patients with hypertension: a narrative review. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 22(4):1271–8. 10.31083/j.rcm2204134

78.

Zhang Q Xu X Wu Q Zhang J Huang S Wu L et al Effects of different traditional Chinese exercise in the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1300319. 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1300319

79.

Aiming S Yan W Jiajia H . Study on the reduction of the incidence of cardiovascular diseases by practicing the five-animal exercises. Sports Sci Res. (2015) 19(06):38–40. 10.19715/j.tiyukexueyanjiu.2015.06.008

80.

Alsubiheen A Petrofsky J Yu W Lee H . Effect of tai chi combined with mental imagery on cutaneous microcirculatory function and blood pressure in a diabetic and elderly population. Healthcare (Basel). (2020) 8(3):342. 10.3390/healthcare8030342

81.

Wehner C Blank C Arvandi M Wehner C Schobersberger W . Effect of tai chi on muscle strength, physical endurance, postural balance and flexibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. (2021) 7(1):e000817. 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000817

82.

Bull FC Al-Ansari SS Biddle S Borodulin K Buman MP Cardon G et al World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54(24):1451–62. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

83.

Writing Group of the 2020 Chinese Hypertension League Guidelines on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. 2020 Chinese guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Chin Circ J. (2021) 36(04):313–28. CNKI:SUN:ZGXH.0.2021-04-001

84.

Lin B Jin Q Liu C Zhao W Ji R . Effect and mechanism of tai chi on blood pressure of patients with essential hypertension: a randomized controlled study. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. (2022) 62(9):1272–7. 10.23736/S0022-4707.21.13394-8

Summary

Keywords

aerobic exercise, Baduanjin, hypertension, Tai Chi, traditional Chinese exercise

Citation

Liu L, Wang J, Ji X, Wang A, Yang S, Chi X, Hu L, Zhang B and Ma L (2025) Comparing the efficacy of different types of exercise therapy in patients with essential hypertension: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1604112. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1604112

Received

01 April 2025

Accepted

24 September 2025

Published

20 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Marco Alfonso Perrone, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Reviewed by

Sophie Møller, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Daniel Craighead, University of Minnesota, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Liu, Wang, Ji, Wang, Yang, Chi, Hu, Zhang and Ma.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Lihong Ma mlh8168@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.