Abstract

Combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cobalamin C (cblC) type, represents the most common inborn error of cobalamin metabolism, caused by pathogenic variants in the MMACHC gene. We report the case of a 27-year-old Chinese woman who presented with dilated cardiomyopathy and renal insufficiency. Blood amino acid and acylcarnitine profiling revealed elevated ratios of propionylcarnitine (C3) to acetylcarnitine (C2) and C3 to free carnitine (C0). Genetic testing identified compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in MMACHC—c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) and c.609G > A, p. (Trp203Ter)—confirming the diagnosis of cblC-type methylmalonic aciduria with homocystinuria. Despite administration of vitamin B12 and betaine, her heart function did not improve. The patient eventually succumbed to severe COVID-19 infection, which led to metabolic acidosis, renal failure, and multi-organ failure. This case underscores the challenging clinical course of late-onset cblC disorder and contributes to its expanding phenotypic spectrum.

Introduction

Combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cobalamin C (cblC) type, represents the most common inborn error of intracellular cobalamin metabolism. CblC disease can manifest at any age, with clinical presentations varying widely, depending on the age of onset, ranging from prenatal to adulthood (1). However, late-onset cblC disease is less common than the early-onset form. The most frequent clinical manifestations are neurological symptoms, although renal injury, pulmonary arterial hypertension, ocular abnormalities, and thrombotic complications have also been reported (2, 3). In late-onset cases, cognitive impairment and psychiatric disturbances are more prominent (4). Cardiovascular involvement, including cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, and arrhythmias, is rarely reported in MMA (5, 6). Progressive cardiomyopathy and heart failure related to cblC have previously been documented only in early onset disease (7). To our knowledge, dilated cardiomyopathy leading to heart failure as the initial presentation in an adult with late-onset MMA has not been reported. We present such a case of late-onset cblC deficiency in an adult who first presented with dilated cardiomyopathy.

Case presentation

A 27-year-old woman was hospitalized with a five-day history of progressive cough and chest tightness, which worsened in the supine position. She had no significant prior medical history, exhibited normal intelligence and vision, showed no evidence of maculopathy, and had no remarkable family history. She had previously given birth to a healthy boy before being diagnosed with cblC disease and had experienced one miscarriage approximately one year before this admission.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 102/63 mmHg, a pulse of 98 beats/min, and no lower limb edema. Scattered wet rales were audible bilaterally. No cardiac murmurs or gallop rhythms were detected. Cranial nerve examination showed no abnormalities, and muscle strength and tone were normal in all four extremities.

Relevant laboratory tests showed normal liver function, electrolytes, glucose, thyroid function, coagulation profile, platelet count, and myocardial injury markers (Table 1). Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was markedly elevated at 1735 pg/mL (reference 0–100 pg/mL). The D-dimer level exceeded the upper limit of the reference range (556 ng/mL, reference: 0–500 ng/mL). Serum creatinine was elevated (118 μmol/L, reference: 41–73 μmol/L), and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was reduced (54.6 mL/min/1.73m2, reference: >60 mL/min/1.73m2). Urinalysis indicated proteinuria (++), and 24-h urine microalbumin level was elevated (124.08 mg, reference: 0–30 mg/24 h). Homocysteine (HCY) was elevated at 213.8 μmol/L (reference: 0–15 μmol/L). Vitamin B12 levels were also elevated (1,088 pg/mL, reference: 180.00–914.00 pg/mL). Urinary methylmalonic acid was markedly elevated (0.1141, reference:<0.001), representing a 114-fold increase. Plasma amino acid and acylcarnitine analysis revealed an elevated propionylcarnitine (C3) level (4.249 μM, reference: 0.00–3.58 μM). The ratios of C3 to acetylcarnitine (C2) (0.335, normal: 0.01–0.24) and C3 to free carnitine (C0) (0.308, reference: 0.04–0.15) were also increased. Plasma amino acid methionine level was normal (9.611 μM, reference: 2.80–25.3 μM).

Table 1

| Test | Result | Reference value |

|---|---|---|

| AST | 15 | 13–40 U/L |

| ALT | 9 | 7–45 U/L |

| γ-GGT | 14 | 7–45 U/L |

| ALP | 47 | 35–135 U/L |

| GLU | 4.56 | 3.90–6.10 mmol/L |

| LDH | 232 | 120–250 U/L |

| Scr | 118 | 41–73 μmol/L |

| CysC | 1.57 | 0.55–1.20 mg/L |

| BUN | 6.62 | 2.6–7.5 mmol/L |

| K | 4.33 | 3.50–5.30 mmol/L |

| Na | 137 | 137–147 mmol/L |

| Cl | 104 | 99–110 mmol/L |

| Hs-cTnI | <0.01 | 0–0.03 ng/mL |

| BNP | 1,735 | 0–100 pg/mL |

| FT3 | 5.52 | 3.53–7.37 pmol/L |

| FT4 | 13.17 | 7.98–16.02 pmol/L |

| TSH | 1.65 | 0.560–5.910 pmol/L |

| PT | 12.2 | 8.80–13.80 s |

| APTT | 31.7 | 26.0–42.0 s |

| INR | 1.09 | 0.80–1.20 |

| FIB | 2.85 | 2.00–4.00 ng/mL |

| PLT | 221 | 125–350 × 109/L |

Laboratory tests of patient at first visit.

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; γ-GGT, γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GLU, glucose; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Scr, serum creatinine; CysC, cystatin C; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; PT, prothrombin time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio; FIB, fibrinogen; PLT, blood platelet.

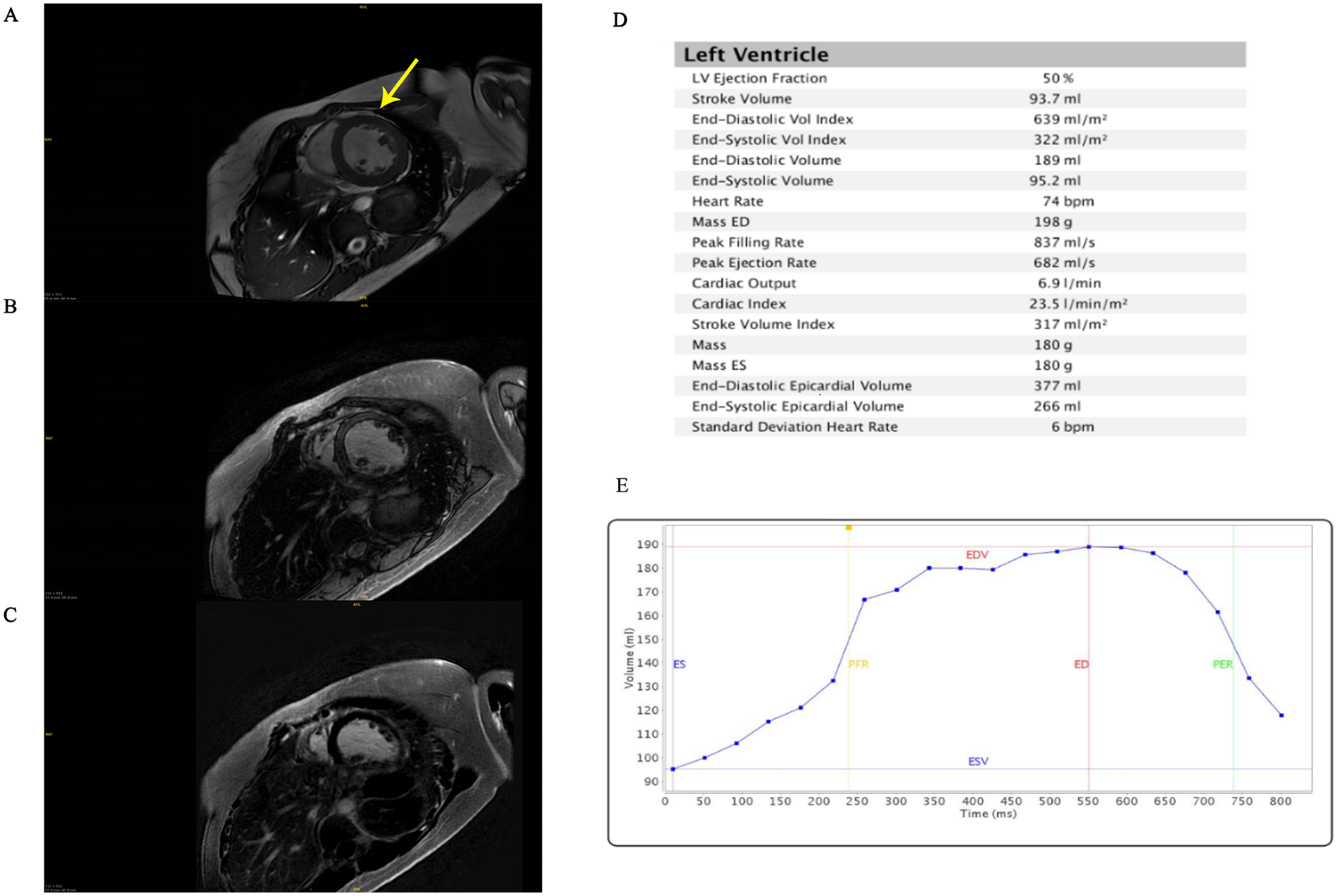

Echocardiography demonstrated a dilated left ventricle (left ventricular end diastolic diameter: 64 mm), left ventricular non-compaction, severe mitral regurgitation, mildly elevated pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (37 mmHg), and severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (34%). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed left ventricular dilatation and prominent apical trabeculation (Figure 1). However, the findings did not meet the criteria for left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) (8). Electrocardiography (ECG) showed no signs of myocardial ischemia.

Figure 1

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. (A) T1 mapping. The arrow points to the presence of abundant muscle trabeculae in the left ventricle. (B) Late gadolinium enhancement. (C) T2 fat saturation. (D) Left ventricular parameters. (E) Time-volume function. ES, end-systolic; ED, end-diastolic; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; PFR, peak filling rate; PER, peak rejection rate.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was unremarkable. Renal ultrasound revealed increased cortical echogenicity and loss of corticomedullary differentiation. No evidence of pulmonary inflammation was found on chest computed tomography.

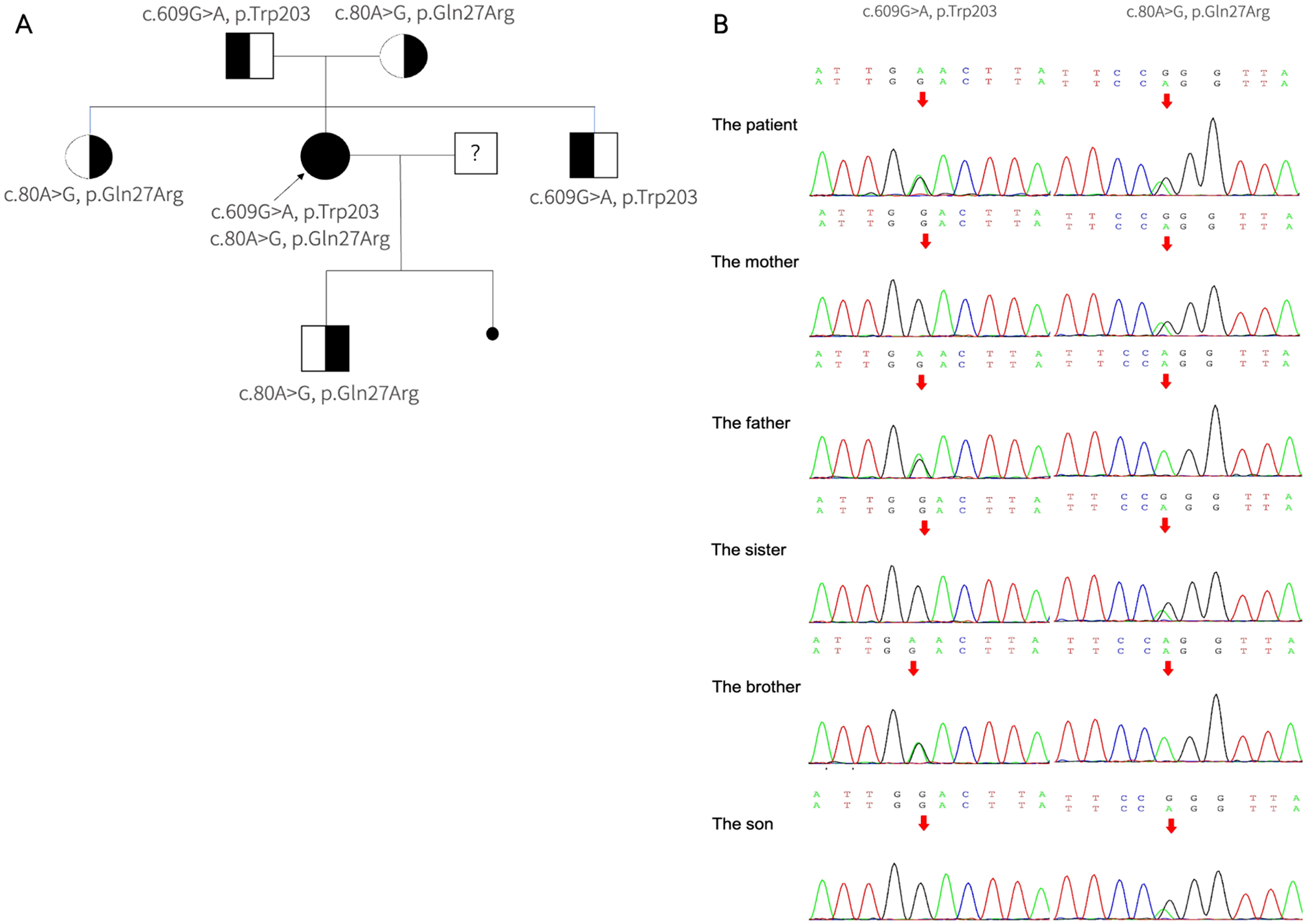

Genetic analysis identified compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in the MMACHC gene: c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) and c.609G > A, p. (Trp203*) (Figure 2). Cascade molecular testing of the parents confirmed that the variants were in an “in trans” configuration in the proband and revealed carrier status in additional family members. The MMACHC gene pathogenic variants were c.609G > A in her father and c.80A > G in her mother (Figure 2). Her child carried the c.80A > G heterozygous pathogenic variants in MMACHC gene. Whole-exome sequencing did not detect any other known cardiomyopathy-associated pathogenic variants. These findings suggest that the patient's myocardial injury may be related to congenital metabolic disorder. The final diagnosis was late-onset cblC disease accompanied by dilated cardiomyopathy.

Figure 2

The pathogenic variants detected in MMACHC. (A) The pedigree of the family with MMA. The arrows suggest the proband, her parents, brother, sister, and son have no signs of MMA. She has one miscarried child with unknown genotype. (B) Segregation analysis of the pathogenic variants within the family revealed that the proband is a compound heterozygote. The c.80A > G mutation was maternally inherited, identified in her mother, sister, and son. Conversely, the c.609G > A mutation was paternally inherited, found only in her father and brother.

The patient was initially treated with hydroxocobalamin (1 mg/day) and betaine (9 g/day). Furosemide (20 mg/day) was administered to alleviate symptoms of heart failure. In addition, sacubitril/valsartan (50 mg/day) and metoprolol (23.75 mg/qd) were also prescribed as anti-myocardial remodeling drugs. Following treatment, the patient's dyspnea resolved and NT-proBNP levels returned to normal, leading to her discharge from the hospital.

After 1 month of treatment, her urine methylmalonate acid level decreased significantly to 0.052 (reference range:<0.001) but remained above normal. Accordingly, the hydroxocobalamin dose was increased to 10 mg daily. However, due to a limited understanding of her illness, financial constraints, fatigue from frequent medical appointments, and a fear of blood draws, the patient often avoided regular follow-up. As a result, amino acid and acylcarnitine profiling was not performed.

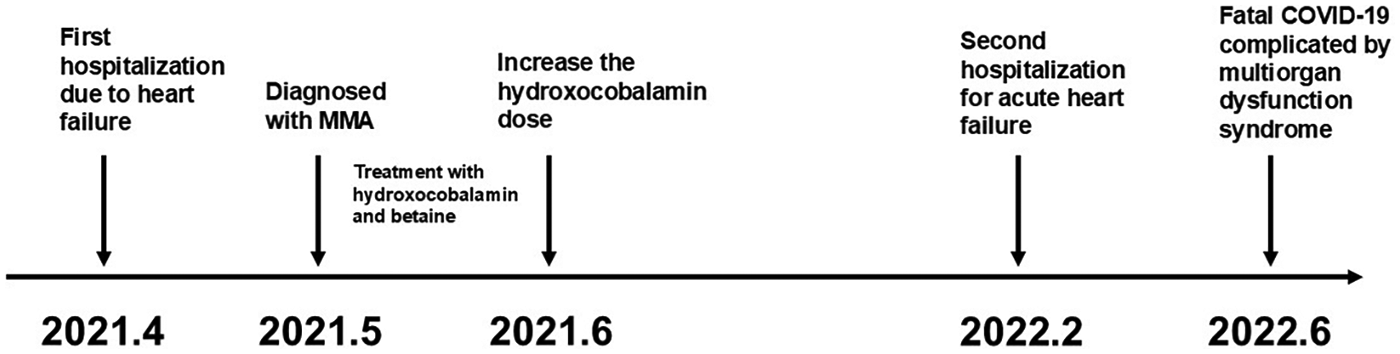

Renal and heart functions remained stable but persistently impaired over more than one year of follow-up (Table 2). Two years after the initial diagnosis, the patient contracted coronavirus disease 2,019 (COVID-19). Within two weeks, her cardiac and renal functions deteriorated rapidly, accompanied by significant elevations in D-dimer and HCY. She subsequently developed disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and multiorgan failure, ultimately leading to unsuccessful resuscitation and death. The overall clinical course is summarized in Figure 3.

Table 2

| Renal function | Cardiac function | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Creatinine (μmol/L) |

BUN (mmol/L) |

eGFR (N, 90–110 mL/min/1.73m2) |

Ejection fraction (EF) (N, 50–60%) |

Left ventricular end diastolic dimension (LVDd) (N, 35–50 mm) | Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) (N, 10–30 mmHg) |

| Admission | 118 | 6.62 | 54.6 | 34% | 64 mm | 37 |

| 1-month follow-up | 108 | 7.40 | 60.8 | 39% | 67 mm | – |

| 10-month follow-up | 122 | 10.7 | 48.3 | 39% | 66 mm | – |

Follow-up echocardiographic assessments and renal function tests.

Figure 3

Timeline of disease progression.

Discussion

We reported the case of a 27-year-old woman with late-onset cblC disease manifesting as dilated cardiomyopathy and renal dysfunction. The diagnosis was confirmed through comprehensive metabolic and genetic investigations, which revealed markedly elevated homocysteine levels (213.8 μmol/L), significantly increased methylmalonic acid (114-fold above normal), and compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in the MMACHC gene (c.80A > G and c.609G > A).

Methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) is the most common organic aciduria in China, with the combined methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinuria subtype accounting for 60%–80% of cases. Among these, the cblC type is predominant, comprising approximately 95% of all cases (9). CblC disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the MMACHC gene (located on chromosome 1p34.1). Clinical manifestations vary significantly depending on the age of onset. Based on this factor, the disease is categorized into early-onset and late-onset types. Patients who develop overt symptoms after 4 years of age have been defined as late-onset type. Early-onset patients typically present more severe symptoms within the first year with multisystem disease, including neurological, ocular, renal, cardiac, and pulmonary manifestations. In contrast, late-onset patients generally exhibit a milder clinical phenotype, primarily affecting the central nervous system (10).

Given its heterogeneous and non-specific symptoms, late-onset cblC is often under-recognized, leading to frequent misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. This case represents the first documented instance of late-onset cblC disease presenting with cardiomyopathy as the primary manifestation. This finding significantly expands the known clinical spectrum of cblC disease and highlights the importance of considering metabolic disorders in the differential diagnosis of adults presenting with unexplained cardiac symptom.

Cardiac complications are infrequently reported in MMA (11), with late-onset cblC patients typically exhibiting neurological symptoms. Although cardiomyopathy has been documented in some cobalamin metabolism disorders, including cblC deficiency, such cases have predominantly occurred in early-onset disease. Our literature review indicates that cardiovascular involvement in late-onset cblC is exceptionally rare and, in all previously documented cases, was accompanied by neurological manifestations (Table 3) (5, 6, 12–22). Here, we present the first reported case of late-onset cblC disease initially manifesting with dyspnea as the primary symptom and isolated dilated cardiomyopathy, in the absence of neurological involvement. This atypical presentation highlights diagnostic challenges, as the absence of neurological symptoms and late onset frequently lead to missed diagnoses.

Table 3

| NO (reference) |

Report year | Age at diagn | Clinical Manifestations | Types of heart disease | serum HCY(µmol/L) | MMA(mmol/ mol cr) | MMACHC m |

Treatment regimen | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (12) | 1999 | 5 months | Congenital malformations | Pulmonic stenosis | ↑ | ↑ | N/A | CBL | Improved |

| 2 (12) | 1999 | 2 months | Congenital malformations | VSD | ↑ | ↑ | N/A | CBL | Improved |

| 3 (13) | 2001 | 3 weeks | Feeding difficulties, failure to thrive | VSD | 282 | 1,914 (in urine) |

N/A | CBL, F, CYS,PR | Improved |

| 4 (14) | 2009 | Prenatal | Growth restriction | DCM, VSD | 236 | ↑ | N/A | CBL, PR, CAR, F, CYS | Improved |

| 5 (6) | 2009 | birth | Found during routine screening | ASD, LVEF decrease | 63 | 29 (in urine) |

568insT/568 | CBL, PR, CAR, F | Improved |

| 6 (6) | 2009 | 2 months | Found during routine screening | Mitral valve prolapse and Mild mi | 95 | 266 (in urine) |

271dupA/2 | CBL, PR, CYS, F | Improved |

| 7 (6) | 2009 | Prenatal | Found during routine screening | Focal LVNC | 107 | 196 (in urine) |

271dupA/2 | CBL, PR, CYS, F | Improved |

| 8 (6) | 2009 | 3 years | Found during routine screening | Normal structure, LVEF decrease | 99 | 57 (in urine) |

C666A/C666 | CBL, PR, CYS, ASA | Improved |

| 9 (6) | 2009 | 3 months | Found during routine screening | VSD | 69 | 74 (in urine) |

C481 T/C481 | CBL, PR, CYS, ASA | Improved |

| 10 (6) | 2009 | 2 months | Found during routine screening | Normal structure, LVEF decrease | 35 | 24 (in urine) |

G609A/G60 | CBL, PR, CYS, CAR, F | Improved |

| 11 (6) | 2009 | Birth | Found during routine screening | Normal structure, LVEF decrease | 32 | 35 (in urine) |

271dupA/2 | CBL, PR, CYS, F, M, C | Improved |

| 12 (6) | 2009 | Birth | Found during routine screening | ASD, focal LVNC | 64 | 31 (in urine) |

547–8delGT | CBL, PR, CYS, CAR, F | Improved |

| 13 (6) | 2009 | Birth | Found during routine screening | Normal structure, LVEF decrease | 30 | 34 (in urine) |

271dupA/2 | CBL, PR, CAR, F | Improved |

| 14 (6) | 2009 | Birth | Found during routine screening | Normal structure, LVEF decrease | 42 | 20 (in urine) |

G608A/G60 | CBL, PR, CAR, F | Improved |

| 15 (5) | 2013 | Prenatal | Found during routine prenatal ultrasound | LVNC | 180 | 330 (in urine) |

c.271dupA | CAR, CBL, F, CYS, PR, ASA | Improved |

| 16 (15) | 2013 | 2 years | Feeding difficulties, failure to thrive | PAH | 66.9 | 9.9μmol/L (in serum) |

c.271dupA/c.A389G | CYS,CBL,F | Died |

| 17 (16) | 2013 | 1.5 years | Tachydyspnea | PAH | N/A | N/A | c.276G.T/c.271dupA | CBL | Died |

| 18 (16) | 2013 | 2.5 years | Tachydyspnea | PAH | 123 | 14424 nmol/L (in serum) |

c.464G.A/c.464G.A | CBL | Died |

| 19 (16) | 2013 | 3 years | Fatigue | PAH | 185 | 1,546 nmol/L (in serum) |

c.276G.T/c.442_444delinsA | CBL | Died |

| 20 (16) | 2013 | 4 years | Fatigue | PAH | 142 | 8,602 nmol/L (in serum) |

c.276G.T/c.271dupA | CBL | N/A |

| 21 (16) | 2013 | 14 years | Fatigue | PAH | 147 | N/A | c.276G.A/c.14_24del11 | CBL | N/A |

| 22 (17) | 2017 | 21 months | Shortness of breath and fever | PAH, mild tricuspid and pulmonary valve regurgitation | ↑ | 0.218 mg/dL (in serum); 0.428 mg/dL (in urine) |

c.80A > G(p | CBL, CAR, CYS | Improved |

| 23 (17) | 2017 | 4 years | Cough, dyspnea | PAH, moderate tricuspid regurgitation and mild pulmonary valve regurgitation | >50.0 | 0.294 mg/dL (in serum); 0.354 mg/dL (in urine) |

N/A | CBL, CAR, CYS | Died |

| 24 (17) | 2017 | 7 years | Mild wet cough and shortness of breath | PAH | 193.76 | 0.383 mg/dL (in serum); 0.1034 mg/dL (in urine) |

c.80A > G(p | CBL, F, CAR, CYS | Improved |

| 25 (18) | 2018 | 2 years | Severe respiratory symptoms, palmoplantar edema | PAH | 74 | 138 (in serum); 919 (in urine) |

c.271dupA | CBL, CAR, CYS | Improved |

| 26 (19) | 2019 | 2 months | Pneumonia, anemia | Heart failure | 290 | 178.24 (in urine) |

c.80A > G; c | N/A | N/A |

| 27 (20) | 2021 | 3-months | Failure to thrive, hypotonia and pallor | DCM | 148 | 3482 (in urine) |

c.271dupA | CAR, CBL, F,CYS | Improved |

| 28 (21) | 2022 | 4 years | Pale complexion, brown urine, vomiting, and fatigue. | Coronary artery ectasia | 216.7 | 43.05 (in urine) |

c.80A > G, p.(Q27R) and c.609G > A (W203X) | CBL, CRE, CYS, F, ASA | Improved |

| 29 (22) | 2025 | 3 years | Vomiting, edema | Hypertension, left heart enlargement | 31.7 | 53.9 (in urine) |

c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) and c.609G > A, p. (Trp203*) | CAR, CBL, F, PR | Died |

| 30 (22) | 2025 | 6 years | Vomiting, shortness of breath, edema | Hypertension, left heart enlargement, non-compaction of ventricular myocardium | 212.9 | 20.5 (in urine) |

c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) and c.609G > A, p. (Trp203*) | CAR, CBL, F, PR | Improved |

| 31 (22) | 2025 | 12 years | Lethargy, cough | Hypertension, left heart enlargement | 136.6 | 44.3 (in urine) |

c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) and c.609G > A, p. (Trp203*) | CAR, CBL, F, PR | Improved |

| 32 (22) | 2025 | 6 years | Recurrent pneumonia | Enlarged heart, pulmonary hypertension | 136 | 64.7 (in urine) |

c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) and c.609G > A, p. (Trp203*) | CAR, CBL, F, PR | Improved |

Documented cases of patients with cblC defect who presented with cardiac disease.

CblC, cobalamin C deficiency; ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; LVNC, left ventricular non-compaction; VSD, ventricular septal defect; ↑, larger than the reference value; CAR, carnitine; CBL, hydroxocobalamin; F, folic acid/folate; CYS, cystadane/betaine; PR, protein restriction; ASA, aspirin; M, methioniine; CRE, creatine; N/A, not available.

To demonstrate the relationship between dilated cardiomyopathy and cblC, whole-exome sequencing for this patient was performed. The result revealed no related genes associated with cardiomyopathy in this patient. Therefore, the myocardial damage in this patient might be attributed to congenital metabolic disease. The pathological mechanisms of the impact of cblC disease on the cardiovascular system are not yet fully understood. Mmachc mouse models have been used to study the pathophysiology of combined methylmalonic acidemia, and these animals also present with cardiac abnormalities, displaying thin, hypertrabeculated ventricles and ventricular septum defects (23). In this case, the patient's genetic analysis revealed a compound heterozygous mutation in the MMACHC gene [c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) from her mother and c. 609G > A, p. (Trp203*) from her father]. These are the most commonly reported pathogenic variants in cblC deficiency in China (19, 22). This patient also presented with renal dysfunction, characterized by abnormal renal ultrasound findings and proteinuria. This renal impairment was an asymptomatic laboratory and imaging finding, discovered concurrently with the cardiac symptoms. The c.80A > G, p. (Gln27Arg) variant observed in this case has also been associated with prominent renal complications in Chinese cblC patients, with several cases of late-onset thrombotic microangiopathy/hemolytic uremic syndrome (24, 25). However, in this patient, a renal biopsy was not performed, precluding confirmation of thrombotic microangiopathy.

In the literature review of cblC, early-onset cases frequently presented with life-threatening cardiac involvement but typically demonstrated significant improvement with prompt vitamin B12 administration. Most cblC patients responded favorably to treatment, with resolution of both clinical symptoms and biochemical abnormalities. Although late-onset cases are generally associated with better long-term outcomes, data on patients with cardiac involvement remain limited. In the present case of MMA, while an optimal treatment regimen led to rapid normalization of BNP and resolution of wheezing symptoms, it did not reverse the existing myocardial remodeling. This suggests that the treatment was effective in managing acute hemodynamic stress but did not alter the chronic structural adaptation of the heart. The myocardial damage appeared irreversible and ultimately led to a poor outcome. The patient died from COVID-19-induced DIC and subsequent multi-organ failure. COVID-19 is known to damage multiple organs, including the heart and kidneys, through a common pathway of systemic dermatitis thrombotic microvascular disease. Renal failure (anuria, acidosis) and heart failure exacerbate each other, rapidly leading to a fatal crisis. Delayed diagnosis likely contributed to the progressive deterioration of cardiac function. Earlier intervention might have prevented irreversible organ injury. Our report suggests that although cblC disease is treatable when diagnosed early, delayed recognition and management can lead to irreversible consequences and even death. The later the onset, the worse the prognosis. Therefore, timely diagnosis and effective treatment are crucial to alleviate clinical symptoms and reduce mortality.

Although rare, late-onset combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria (cblC type) should be considered a cause of unexplained heart failure in adolescents or adults with markedly elevated homocysteine levels. When unexplained heart disease is present in adolescents or adults, cardiologists should consider inborn errors of metabolism in the differential diagnosis. Urine organic acid analysis and genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis of cblC disease.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee on Scientific Research of the Second Hospital of Shandong University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

DX: Writing – original draft. CZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LH: Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – original draft. AX: Writing – original draft. LY: Writing – original draft. WW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2021MH064).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Huemer M Scholl-Burgi S Hadaya K Kern I Beer R Seppi K et al Three new cases of late-onset cblC defect and review of the literature illustrating when to consider inborn errors of metabolism beyond infancy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2014) 9:161. 10.1186/s13023-014-0161-1

2.

Carrillo-Carrasco N Chandler RJ P C . Venditti: combined methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinuria, cblC type. I. Clinical presentations, diagnosis and management. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2012) 35(1):91–102. 10.1007/s10545-011-9364-y

3.

Grange S Bekri S Artaud-Macari E Francois A Girault C Poitou AL et al Adult-onset renal thrombotic microangiopathy and pulmonary arterial hypertension in cobalamin C deficiency. Lancet. (2015) 386(9997):1011–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00076-8

4.

Martinelli D Deodato F Dionisi-Vici C . Cobalamin C defect: natural history, pathophysiology, and treatment. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2011) 34(1):127–35. 10.1007/s10545-010-9161-z

5.

Tanpaiboon P Sloan JL Callahan PF McAreavey D Hart PS Lichter-Konecki U et al Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium and hydrops fetalis in cobalamin C disease. JIMD Rep. (2013) 10:33–8. 10.1007/8904_2012_197

6.

Profitlich LE Kirmse B Wasserstein MP Diaz GA Srivastava S . High prevalence of structural heart disease in children with cblC-type methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria. Mol Genet Metab. (2009) 98(4):344–8. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.07.017

7.

Hjalmarsson C Backelin C Thoren A Bergh N Sloan JL Manoli I et al Severe heart failure in a unique case of cobalamin-C-deficiency resolved with LVAD implantation and subsequent heart transplantation. Mol Genet Metab Rep. (2024) 39:101089. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2024.101089

8.

Jenni R Oechslin E Schneider J Attenhofer Jost C Kaufmann PA . Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: a step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart. (2001) 86(6):666–71. 10.1136/heart.86.6.666

9.

Zhang Y Song JQ Liu P Yan R Dong JH Yang YL et al [Clinical studies on fifty-seven Chinese patients with combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocysteinemia]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. (2007) 45(7):513–7.

10.

Ben-Omran TI Wong H Blaser S Feigenbaum A . Late-onset cobalamin-C disorder: a challenging diagnosis. Am J Med Genet A. (2007) 143A(9):979–84. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31671

11.

Liu Y Yang L Shuai R Huang S Zhang B Han L et al Different pattern of cardiovascular impairment in methylmalonic acidaemia subtypes. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:810495. 10.3389/fped.2022.810495

12.

Andersson HC Marble M Shapira E . Long-term outcome in treated combined methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinemia. Genet Med. (1999) 1(4):146–50. 10.1097/00125817-199905000-00006

13.

Tomaske M Bosk A Heinemann MK Sieverding L Baumgartner ER Fowler B et al Cblc/D defect combined with haemodynamically highly relevant VSD. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2001) 24(4):511–2. 10.1023/a:1010541932476

14.

De Bie I Nizard SD Mitchell GA . Fetal dilated cardiomyopathy: an unsuspected presentation of methylmalonic aciduria and hyperhomocystinuria, cblC type. Prenat Diagn. (2009) 29(3):266–70. 10.1002/pd.2218

15.

Iodice FG Chiara LD Boenzi S Aiello C Monti L Cogo P et al Cobalamin C defect presenting with isolated pulmonary hypertension. Pediatrics. (2013) 132(1):e248–51. 10.1542/peds.2012-1945

16.

Komhoff M Roofthooft MT Westra D Teertstra TK Losito A van de Kar NC et al Combined pulmonary hypertension and renal thrombotic microangiopathy in cobalamin C deficiency. Pediatrics. (2013) 132(2):e540–4. 10.1542/peds.2012-2581

17.

Liu J Peng Y Zhou N Liu X Meng Q Xu H et al Combined methylmalonic acidemia and homocysteinemia presenting predominantly with late-onset diffuse lung disease: a case series of four patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2017) 12(1):58. 10.1186/s13023-017-0610-8

18.

De Simone L Capirchio L Roperto RM Romagnani P Sacchini M Donati MA et al Favorable course of previously undiagnosed methylmalonic aciduria with homocystinuria (cblC type) presenting with pulmonary hypertension and aHUS in a young child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. (2018) 44(1):90. 10.1186/s13052-018-0530-9

19.

Wang C Li D Cai F Zhang X Xu X Liu X et al Mutation spectrum of MMACHC in Chinese pediatric patients with cobalamin C disease: a case series and literature review. Eur J Med Genet. (2019) 62(10):103713. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.103713

20.

Karava V Kondou A Dotis J Sotiriou G Gerou S Michelakakis H et al Hemolytic uremic syndrome due to methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinuria in an infant: a case report and literature review. Children (Basel). (2021) 8(2):112. 10.3390/children8020112

21.

Juan T Chao-Ying C Hua-Rong L Ling W . Rare cause of coronary artery ectasia in children: a case report of methylmalonic acidemia with hyperhomocysteinemia. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:917734. 10.3389/fped.2022.917734

22.

Zhao W Zhang Y Pi Y Li Y Zhang H . Clinical and molecular spectrum of patients with methylmalonic acidemia and homocysteinemia complicated by cardiovascular manifestations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2025) 20(1):443. 10.1186/s13023-025-03907-w

23.

Chern T Achilleos A Tong X Hsu CW Wong L Poche RA . Mouse models to study the pathophysiology of combined methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinuria, cblC type. Dev Biol. (2020) 468(1-2):1–13. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2020.09.005

24.

Liu X Xiao H Yao Y Wang S Zhang H Zhong X et al Prominent renal complications associated with MMACHC pathogenic variant c.80A > G in Chinese children with cobalamin C deficiency. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:1057594. 10.3389/fped.2022.1057594

25.

Bao D Yang H Yin Y Wang S Li Y Zhang X et al Late-onset renal TMA and tubular injury in cobalamin C disease: a report of three cases and literature review. BMC Nephrol. (2024) 25(1):340. 10.1186/s12882-024-03774-w

Summary

Keywords

dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure, late-onset cblC, methylmalonic acidemia, renal dysfunction

Citation

Xu D, Zhang C, Hao L, Bi S, Xue A, Yuan L and Wang W (2026) Case Report: Dilated cardiomyopathy as the initial presentation in an adult with late-onset CblC defect. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1610295. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1610295

Received

11 April 2025

Revised

27 December 2025

Accepted

31 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Michele Costanzo, University of Naples Federico II, Italy

Reviewed by

Shiwei Yang, Children's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, China

Amira Mobarak, Tanta University, Egypt

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xu, Zhang, Hao, Bi, Xue, Yuan and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Wenke Wang ke2986@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.