Abstract

Introduction:

Although low-dose aspirin effectively reduces atherothrombosis occurrence in individuals diagnosed with cardiovascular disease (CVD) or in those with high-risk factors, it is significantly associated with increased bleeding. No evidence has been established for a lower dose of aspirin.

Methods:

The Lower-dose Aspirin for Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly (LAPIS) is a multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study, which compared the benefits and risks in adults aged 60 years and older taking aspirin 50 or 100 mg/day for primary and secondary CVD prevention in a propensity score-matched population. The efficacy outcome was a composite of the first occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The safety outcome was the first occurrence of any hemorrhagic events.

Results:

In this interim analysis of LAPIS, 7,021 participants were followed up for a median of 183 (95% CI 169–197) days (primary prevention cohort, 2,070; secondary prevention cohort, 4,951). After adjusting for baseline characteristics using propensity score matching, the MACE incidence did not differ significantly between the two dosage groups in either cohort. However, in the primary prevention cohort, the incidence of any bleeding [8.89 vs. 3.45 events/100 patient-years, hazard ratio (HR) 2.917, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.719–4.952, P < 0.001] and gastrointestinal events (8.30 vs. 5.04 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.745, 95% CI 1.047–2.907, P = 0.037) was higher in the 100 mg/day group. In the secondary prevention cohort, the 100 mg/day group showed higher rates of any bleeding (9.19 vs. 6.37 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.473, 95% CI 1.087–1.998, P = 0.015), minor bleeding (9.10 vs. 6.06 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.541, 95% CI 1.116–2.127, P = 0.009), and gastrointestinal adverse events (7.10 vs. 3.53 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.943, 95% CI 1.291–2.925, P = 0.002).

Conclusion:

Aspirin 50 mg/day was associated with lower hemorrhage and gastrointestinal adverse event risks, with similar cardiovascular benefits, compared with aspirin 100 mg/day, and may be preferred to balance efficacy and safety for older Chinese adults in primary and secondary CVD prevention.

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the Chinese population, causing over four million deaths annually and representing more than 40% of total mortality. The aging of the population in China exacerbates the burden of CVD, with both incidence and mortality rising dramatically. This growing demographic challenge underscores the urgent need to optimize management strategies, particularly for elderly individuals with CVD or at an elevated risk.

Aspirin, a platelet aggregation inhibitor that leads to long-lasting suppression of thromboxane A2 production by acetylated cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), has been recommended as a strategy for secondary prevention in the past decade owing to its demonstrated net benefit. Studies have convincingly demonstrated that low-dose aspirin (75–100 mg/day) significantly reduces the occurrence of stroke and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (1–4). However, the role of low-dose aspirin in primary prevention remains debatable. In primary prevention trials assessing older adults, the benefits are often offset by the risk of hemorrhagic events (5–11). Compared with Western populations, East Asian populations using low-dose aspirin (75–100 mg/day) have an increased risk of bleeding (3, 9, 12, 13), especially in patients with severe renal impairment, as well as polypharmacy, including concomitant use of other antithrombotic or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), frailty, and other complicated comorbidities (14).

Aspirin dose is associated with bleeding risk. Therefore, optimizing the aspirin dosage to preserve its efficacy while minimizing the risk of bleeding is crucial (15, 16). It has been reported that doses of aspirin as low as 30 mg/day for a week could completely block the effects of COX-1 (17), and the effective aspirin dose ranges between 50 and 100 mg/day based on randomized controlled trials in both acute coronary syndrome and stable patients with CVD (18). Based on our previous findings (19, 20), we hypothesized that lower-dose aspirin (50 mg/day) would be non-inferior to 100 mg/day for both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and that it might be associated with a lower incidence of adverse events in older Chinese patients. Further studies involving larger multicenter populations are needed to confirm these hypotheses.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study design and participants

The Lower-dose Aspirin for Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly (LAPIS) study (chictr.org.cn, ChiCTR1900021980) is a prospective multicenter observational cohort study performed at 80 sites covering 22 central cities in mainland China. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee [Peking University First Hospital, approval number 2018(248)], and the rationale and design of the study have been previously published (21). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients aged 60 years and older who required long-term aspirin therapy for primary or secondary prevention based on clinical assessment were included. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of aspirin-sensitive asthma or allergies to aspirin, salicylic acid, or NSAIDs; (2) life expectancy of ≤3 years. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Variable definition and data collection

Data at baseline enrollment and follow-up were systematically collected into electronic case report forms using an electronic data capture system according to standard procedures. All essential information was recorded in detail and managed by independent clinical research coordinators of the Shanghai Ashermed Healthcare Communications Ltd. Demographic information included age, sex, smoking history, and alcohol intake. Medical history included previous history of coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), unstable angina, vascular diseases requiring surgical/interventional revascularization, nonfatal stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), hemorrhagic events, gastrointestinal disease, and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia). Laboratory indication included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C), serum lipids (triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol), and high-sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP). Prescription information included the status of aspirin intake, concomitant use of other antiplatelets and anticoagulants, β-blockers, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), aldosterone receptor antagonists (MRAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs). Patients without a history of coronary heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral artery disease were defined as taking aspirin for primary prevention. Hemorrhage history was defined as bleeding at any site and the severity of bleeding events. The timing of prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was not collected in the electronic case report forms, therefore, patients with recent PCI were not specifically identified.

2.3 Follow-up and outcomes

The LAPIS procedures did not interfere with the aspirin therapy strategy administered to the patients. Physicians determined the aspirin dosage and treatment duration based on the patient's clinical condition. Follow-ups were conducted by physicians during face-to-face visits or through telephone calls and online contact. Routine follow-ups were performed at the 1st month and 3rd month and every 6 months thereafter until the end of the LAPIS (at least nine times). An independent group of physicians examined and verified all events at each visit. The efficacy outcome was a composite of the first occurrence of MACE, including unstable angina, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, arteriosclerotic diseases requiring surgery or intervention, cardiovascular death (excluding intracranial hemorrhage), and TIA. The safety outcome was the first occurrence of hemorrhagic events, defined as a composite of fatal bleeding (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium, BARC, type 5), major bleeding (BARC, type 3–4), and minor bleeding (BARC, type 1–2) (22). In addition, data on adverse gastrointestinal events associated with aspirin, including new-onset gastroduodenal ulcer, reflux esophagitis, erosive gastritis, stomach or abdominal discomfort, pain, pressure, heartburn, and nausea, were collected for safety analyses. The time to the event was defined as the number of days from the date of enrollment to the date of confirmation of the event. Participants who did not experience the event of interest were censored at the time of loss to follow-up or at the end of the study period. For analyses in which cardiovascular death was the event of interest, cardiovascular death was treated as the event, whereas deaths from other causes were treated as censoring events.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 27.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All analyses were conducted on populations taking aspirin for primary or secondary prevention. Continuous variables at baseline are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) and were compared using an independent samples t-test or the Mann‒Whitney U-test, whereas categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages and were compared using Pearson's χ2-test or Fisher's exact test when expected counts were <5 in any cell. To reduce potential confounding between the aspirin 50 and 100 mg/day groups, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed at a 1:1 ratio using propensity scores estimated from multivariable logistic regression, with aspirin dose as the dependent variable. Covariates included in the propensity score models were selected a priori based on clinical relevance and their potential to confound the association between aspirin dose and outcomes. Separate propensity score models were constructed for the primary and secondary prevention cohorts. For the primary prevention cohort, covariates included age, sex, current smoking status, current alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus, concomitant use of other antiplatelet agents, ACEIs, ARBs, MRAs, and statins, as well as laboratory parameters including total cholesterol (TCHO), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and eGFR. For the secondary prevention cohort, covariates included age, sex, current smoking status, current alcohol consumption, medical history [coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris, PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), stroke, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and history of hemorrhage], concomitant use of other antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, PPI/H2RA, and statins, as well as laboratory parameters including eGFR, TCHO, LDL-C, and HbA1c. After matching, baseline characteristics between the two aspirin dose groups were compared to assess covariate balance, and all subsequent analyses were conducted in the matched cohorts. Median follow-up time was estimated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. Events were presented as both raw incidence proportions (patients with events/number of treated patients) and incidence rates (patients with events per 100 patient-years). Time-to-event data were depicted using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, and the differences between the curves were assessed using the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were developed to identify the independent predictors of bleeding events after adjusting for variables known to be strongly associated with the risk of bleeding events or differed significantly on univariable analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Statistical significance was defined for all analyses as a two-sided P-value of less than 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Participants and follow-up

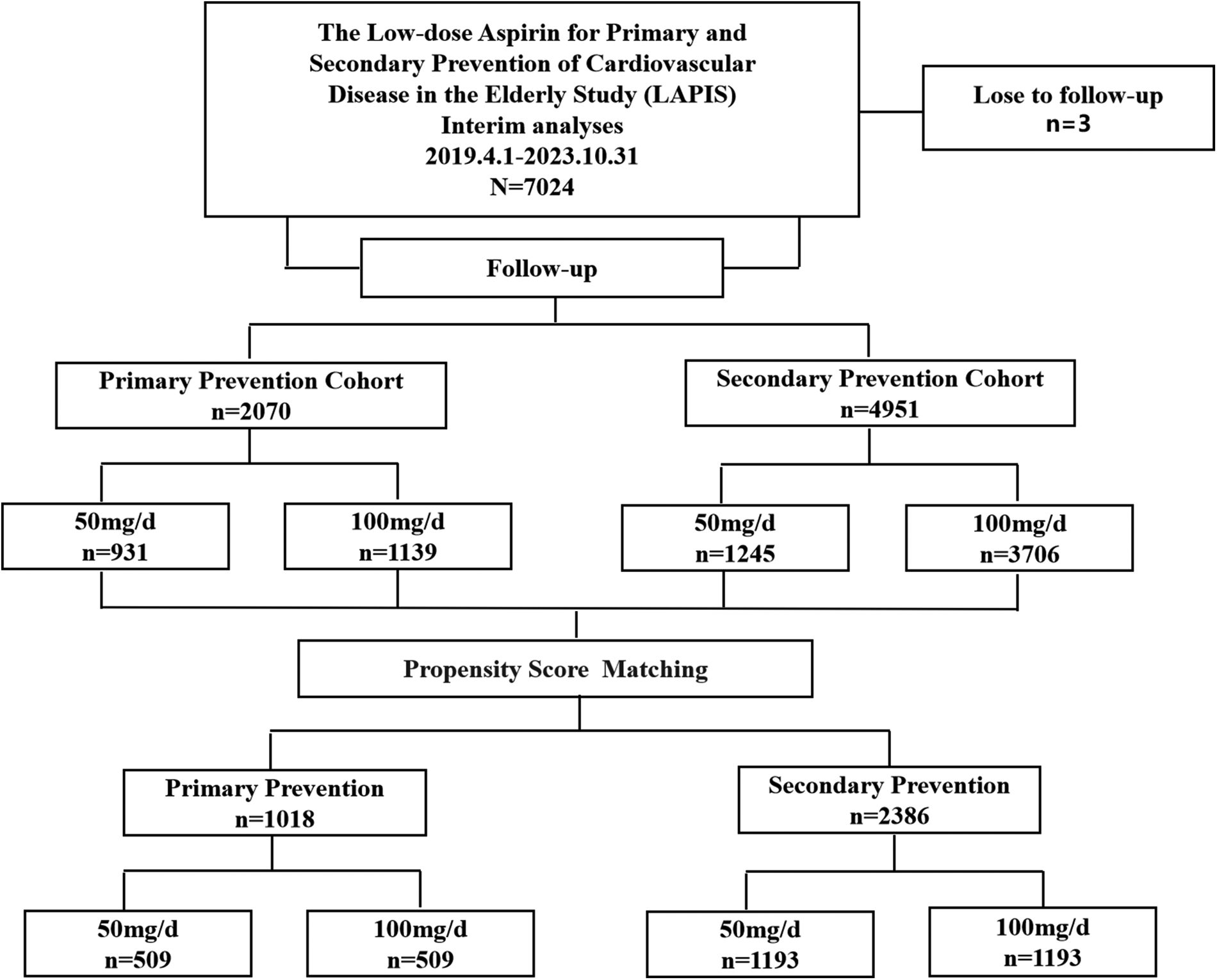

After excluding patients lost to follow-up, 7,021 participants were enrolled in the LAPIS, with a median follow-up of 183 (95% CI 169–197) days, from April 1, 2019, to October 31, 2023. In total, 2,070 and 4,951 participants were included in the primary and secondary prevention cohorts, respectively (Figure 1). Of these, 2,176 patients (30.99%) received aspirin 50 mg/day, and 4,845 (69.01%) patients received aspirin 100 mg/day. New-onset MACE occurred in 145 patients (2.07%), bleeding events occurred in 554 patients (7.89%), and gastrointestinal adverse events occurred in 468 patients (6.67%). There were 96 deaths (1.37%).

Figure 1

Flow diagram.

3.2 Primary prevention

3.2.1 Baseline characteristics

After propensity score matching, the aspirin 50 and 100 mg/day groups were well balanced with respect to baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. No statistically significant differences in baseline variables were observed between the two groups after matching. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants at baseline are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristic | Before PSM adjustment | After PSM adjustment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin 50 mg/day | Aspirin 100 mg/day | P | Aspirin 50 mg/day | Aspirin 100 mg/day | P | |

| Number of patients | 931 | 1,139 | 509 | 509 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years | 68.59 ± 6.74 | 69.38 ± 6.51 | 0.007* | 69.11 ± 7.14 | 69.41 ± 6.70 | 0.491 |

| ≥75, n (%) | 173 (18.6%) | 247 (21.7%) | 0.081 | 107 (21.0%) | 113 (22.2%) | 0.648 |

| Male, n (%) | 424 (45.50%) | 571 (50.1%) | 0.038* | 253 (49.7%) | 261 (51.3%) | 0.616 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 97 (10.4%) | 238 (20.9%) | <0.001* | 66 (13.0%) | 65 (12.8%) | 0.925 |

| Current drinking, n (%) | 113 (12.1%) | 295 (25.9%) | <0.001* | 82 (16.1%) | 85 (16.7%) | 0.800 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 596 (64.0%) | 733 (64.4%) | 0.873 | 315 (61.9%) | 337 (66.2%) | 0.151 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 196 (21.1%) | 312 (27.4%) | <0.001* | 115 (22.6%) | 115 (22.6%) | 1.000 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 131 (14.1%) | 162 (14.2%) | 0.921 | 70 (13.8%) | 57 (11.2%) | 0.218 |

| Gastrointestinal disease, n (%) | 75 (8.1%) | 94 (8.3%) | 0.871 | 49 (9.6%) | 46 (9.0%) | 0.747 |

| Hemorrhage history, n (%) | 10 (1.1%) | 16 (1.4%) | 0.502 | 7 (1.4%) | 4 (0.8%) | 0.547 |

| Concomitant medication | ||||||

| Concomitant use of other antiplatelets, n (%) | 26 (2.8%) | 163 (14.3%) | <0.001* | 21 (4.1%) | 19 (3.7%) | 0.747 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 25 (2.7%) | 157 (13.8%) | <0.001* | 21 (4.1%) | 19 (3.7%) | 0.747 |

| Ticagrelor, n (%) | 0 | 4 (0.4%) | 0.132 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Cilostazol, n (%) | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1.000 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Concomitant use of anticoagulants, n (%) | 9 (1.0%) | 6 (0.5%) | 0.240 | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1.000 |

| Rivaroxaban, n (%) | 4 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.181 | 2 (0.4%) | 0 | 0.500 |

| Dabigatran, n (%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 0.450 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Warfarin n (%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1.000 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Low molecular weight heparin, n (%) | 3 (0.3%) | 4 (0.4%) | 1.000 | 0 | 2 (0.4%) | 0.500 |

| β-blocker, n (%) | 124 (13.3%) | 140 (12.3%) | 0.486 | 77 (15.1%) | 72 (14.1%) | 0.658 |

| ACEI/ARB/MRA, n (%) | 107 (11.5%) | 214 (18.8%) | <0.001* | 84 (16.5%) | 80 (15.7%) | 0.733 |

| Statin, n (%) | 518 (55.6%) | 776 (68.1%) | <0.001* | 340 (66.8%) | 322 (63.3%) | 0.237 |

| PPI/H2RA, n (%) | 76 (8.2%) | 69 (6.1%) | 0.062 | 55 (10.8%) | 42 (8.3%) | 0.165 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 95.81 ± 24.70 | 98.57 ± 33.34 | 0.046* | 95.69 ± 24.34 | 97.91 ± 26.67 | 0.179 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.53 ± 0.93 | 1.59 ± 1.03 | 0.247 | 1.44 ± 0.86 | 1.46 ± 0.92 | 0.747 |

| TCHO (mmol/L) | 4.76 ± 1.17 | 4.58 ± 1.17 | 0.001* | 4.22 ± 0.82 | 4.21 ± 0.85 | 0.886 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.45 ± 0.59 | 2.29 ± 0.63 | <0.001* | 2.38 ± 0.60 | 2.36 ± 0.63 | 0.506 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.33 | 1.24 ± 0.31 | 0.721 | 1.21 ± 0.33 | 1.21 ± 0.30 | 0.856 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.10 (5.70, 7.00) | 6.20 (5.70, 7.11) | 0.403 | 6.00 (5.70, 6.80) | 6.10 (5.60, 7.00) | 0.659 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 1.17 (0.50, 3.75) | 1.20 (0.50, 2.70) | 0.508 | 0.97 (0.50, 3.60) | 1.15 (0.50, 2.35) | 0.777 |

Baseline characteristics for 50 and 100 mg/day aspirin in primary prevention.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and percentage (%) for categorical variables. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; H2RA, histamine 2 receptor antagonist; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; MRA, aldosterone receptor antagonist; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; PSM, propensity score matching; TCHO, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

P-value <0.05 was considered nominally statistically significant.

3.2.2 Efficacy and safety outcomes

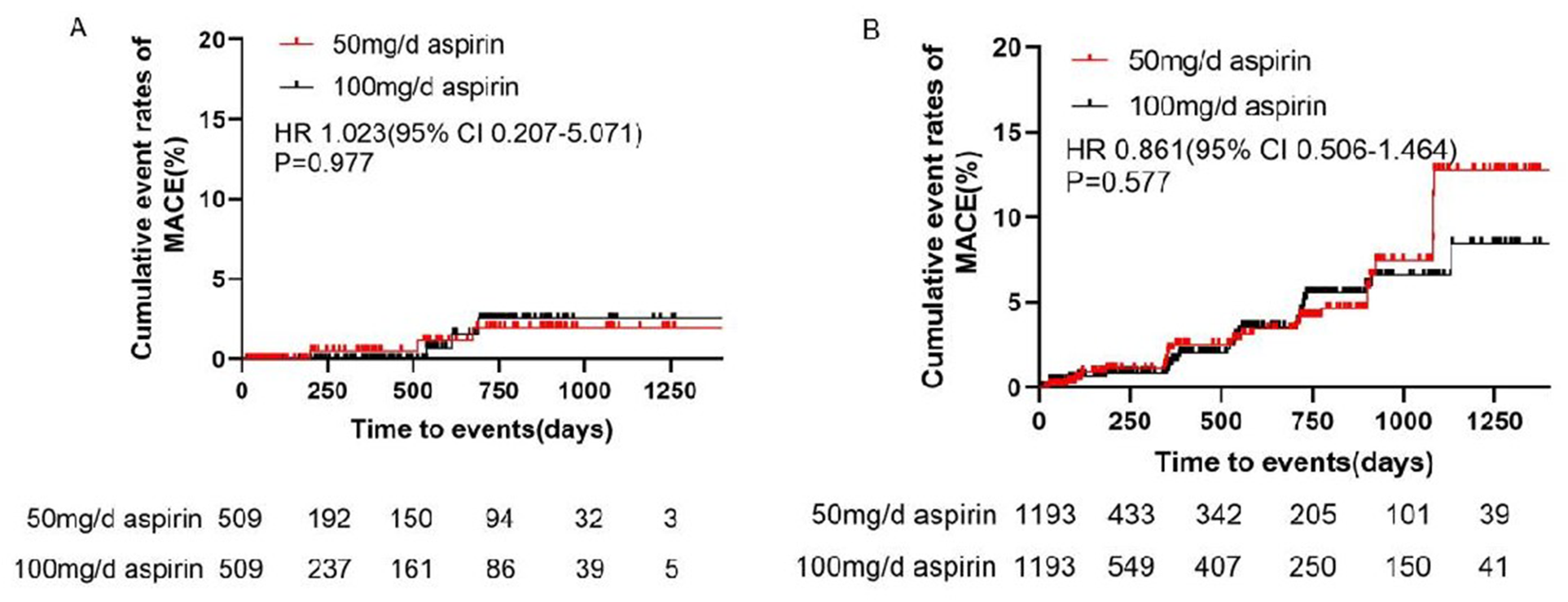

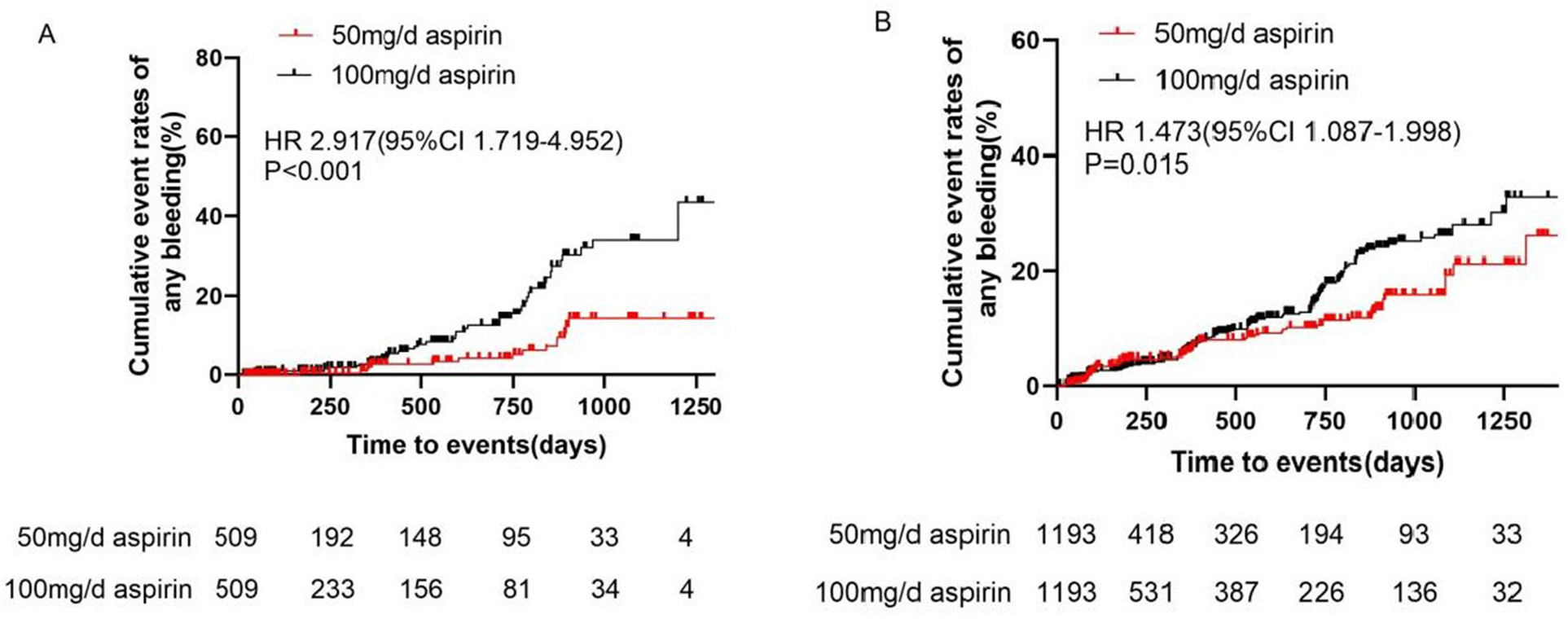

After adjustment, the incidence of MACE did not differ significantly between the 100 and 50 mg/day groups (0.65 vs. 0.70 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.023, 95% CI 0.207–5.071, P = 0.977) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Bleeding events occurred in 18 (1.93%) patients in the 50 mg group and 107 (9.39%) patients in the 100 mg group. After adjustment, the incidence rates of any bleeding events, minor bleeding events (8.89 vs. 3.45 events/100 patient-years, HR 2.917, 95% CI 1.719–4.952, P < 0.001), and gastrointestinal adverse events (8.30 vs. 5.04 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.745, 95% CI 1.047–2.907, P = 0.037) were higher in the 100 mg group than in the 50 mg group (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Table 2

| Outcome | Before PSM adjustment | After PSM adjustment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients with event/No. of treated patients (Incidence rate, events/100 patient-years) | HR (95% CI) 100 vs. 50 mg/day | P | No. of patients with event/No. of treated patients (Incidence rate, events/100 patient-years) | HR (95% CI) 100 vs. 50 mg/day | P | |||

| Aspirin 50 mg/day (n = 931) | Aspirin 100 mg/day (n = 1,139) | Aspirin 50 mg/day (n = 509) | Aspirin 100 mg/day (n = 509) | |||||

| Efficacy outcomes | ||||||||

| MACE | 5/931 (0.63) | 9/1,139 (0.82) | 1.197 (0.390–3.671) | 0.753 | 3/509 (0.70) | 3/509 (0.65) | 1.023 (0.207–5.071) | 0.977 |

| UA | 1/931 (0.13) | 2/1,139 (0.18) | 0.717 (0.045–11.471) | 0.814 | 1/509 (0.23) | 1/509 (0.02) | 0.894 (0.056–14.333) | 0.937 |

| Nonfatal MI | 0 | 0 | - | - | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Nonfatal stroke | 2/931 (0.25) | 2/1,139 (0.18) | 0.715 (0.099–5.171) | 0.740 | 2/509 (0.46) | 1/509 (0.02) | 0.536 (0.048–5.926) | 0.611 |

| Arteriosclerotic diseases requiring surgery or intervention | 2/931 (0.25) | 1/1,139 (0.09) | 0.393 (0.036–4.336) | 0.446 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Cardiovascular death | 0 | 3/1,139 (0.27) | - | - | 0 | 1/509 (0.02) | - | - |

| TIA | 0 | 1/1,139 (0.09) | - | - | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Safety outcomes | ||||||||

| Any bleeding | 18/931 (2.27) | 107/1,139 (9.90) | 4.487 (2.721–7.400) | <0.001* | 15/509 (3.45) | 40/509 (8.89) | 2.917 (1.719–4.952) | <0.001* |

| Minor bleeding (BARC 1–2) | 18/931 (2.27) | 106/1,139 (9.81) | 4.445 (2.695–7.333) | <0.001* | 15/509 (3.45) | 40/509 (8.89) | 2.917 (1.719–4.952) | <0.001* |

| Major bleeding (BARC 3–4) | 0 | 1/1,139 (0.09) | - | - | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Fatal bleeding (BARC 5) | 0 | 0 | - | - | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal adverse events | 26/931 (3.35) | 125/1,139 (11.61) | 3.483 (2.282–5.318) | <0.001* | 21/509 (5.04) | 38/509 (8.30) | 1.745 (1.047–2.907) | 0.037* |

Efficacy and safety outcomes for 50 and 100 mg/day aspirin in primary prevention.

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; PSM, propensity score matching; TIA, transient ischemic attacks; UA, unstable angina pectoris.

P-value <0.05 was considered nominally statistically significant.

Figure 2

Cumulative event rates of MACE in (A) primary prevention and (B) secondary prevention. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major cardiovascular events.

Figure 3

Cumulative event rates of bleeding events in (A) primary prevention and (B) secondary prevention. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

3.3 Secondary prevention

3.3.1 Baseline characteristics

After propensity score matching, the aspirin 50 and 100 mg/day groups were well balanced with respect to baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. No statistically significant differences in baseline variables were observed between the two groups after matching. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants at baseline are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Characteristic | Before PSM adjustment | After PSM adjustment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin 50 mg/day | Aspirin 100 mg/day | P | Aspirin 50 mg/day | Aspirin 100 mg/day | P | |

| Number of patients | 1,245 | 3,706 | 1,193 | 1,193 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years | 71.27 ± 8.13 | 70.26 ± 6.98 | <0.001* | 71.15 ± 8.06 | 71.17 ± 7.41 | 0.962 |

| ≥75, n (%) | 386 (31.0%) | 970 (26.2%) | <0.001* | 362 (30.3%) | 371 (31.1%) | 0.690 |

| Male, n (%) | 571 (45.9%) | 2,152 (58.1%) | <0.001* | 549 (46.0%) | 574 (48.1%) | 0.305 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 134 (10.8%) | 776 (20.9%) | <0.001* | 132 (11.1%) | 137 (11.5%) | 0.746 |

| Current drinking, n (%) | 121 (9.7%) | 788 (21.3%) | <0.001* | 121 (10.1%) | 130 (10.9%) | 0.548 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 1,102 (88.5%) | 3,092 (83.4%) | <0.001* | 1,050 (88.0%) | 1,045 (87.6%) | 0.754 |

| MI history, n (%) | 101 (8.1%) | 668 (18.0%) | <0.001* | 101 (8.5%) | 98 (8.2%) | 0.824 |

| UA, n (%) | 323 (25.9%) | 1,434 (38.7%) | <0.001* | 322 (27.0%) | 325 (27.2%) | 0.890 |

| PCI/CABG history, n (%) | 156 (12.5%) | 1,027 (27.7%) | <0.001* | 155 (13.0%) | 154 (12.9%) | 0.951 |

| Stroke history, n (%) | 223 (17.9%) | 1,030 (27.8%) | <0.001* | 222 (18.6%) | 227 (19.0%) | 0.793 |

| TIA history, n (%) | 55 (4.4%) | 140 (3.8%) | 0.315 | 54 (4.5%) | 64 (5.4%) | 0.345 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 849 (68.2%) | 2,700 (72.9%) | 0.002* | 822 (68.9%) | 802 (67.2%) | 0.380 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 327 (26.3%) | 1,258 (33.9%) | <0.001* | 319 (26.7%) | 320 (26.8%) | 0.963 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 291 (23.4%) | 910 (24.6%) | 0.400 | 284 (23.8%) | 269 (22.5%) | 0.467 |

| Gastrointestinal disease, n (%) | 220 (17.7%) | 600 (16.2%) | 0.224 | 211 (17.7%) | 213 (17.9%) | 0.915 |

| Hemorrhage history, n (%) | 73 (5.9%) | 117 (3.2%) | <0.001* | 67 (5.6%) | 61 (5.1%) | 0.586 |

| Concomitant medication | ||||||

| Concomitant use of other antiplatelets, n (%) | 216 (17.3%) | 1,673 (45.1%) | <0.001* | 216 (18.1%) | 245 (20.5%) | 0.133 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 170 (12.7%) | 1,227 (33.1%) | <0.001* | 170 (14.2%) | 186 (15.6%) | 0.358 |

| Ticagrelor, n (%) | 44 (3.5%) | 442 (11.9%) | <0.001* | 44 (3.7%) | 58 (4.9%) | 0.157 |

| Cilostazol, n (%) | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 1.000 | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1.000 |

| Concomitant use of anticoagulants, n (%) | 62 (5.0%) | 79 (2.1%) | <0.001* | 52 (4.4%) | 50 (4.2%) | 0.840 |

| Rivaroxaban, n (%) | 40 (3.2%) | 47 (1.3%) | <0.001* | 33 (2.8%) | 27 (2.3%) | 0.433 |

| Dabigatran, n (%) | 8 (0.6%) | 3 (0.1%) | 0.001* | 8 (0.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0.109 |

| Warfarin n (%) | 3 (0.2%) | 6 (0.2%) | 0.700 | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.4%) | 0.452 |

| Low molecular weight heparin, n (%) | 11 (0.9%) | 23 (0.6%) | 0.427 | 9 (0.8%) | 16 (1.3%) | 0.159 |

| β-blocker, n (%) | 501 (40.2%) | 1,567 (42.3%) | 0.206 | 488 (40.9%) | 442 (37.0%) | 0.053 |

| ACEI/ARB/MRA, n (%) | 352 (28.3%) | 1,145 (30.9%) | 0.081 | 332 (27.8%) | 318 (26.7%) | 0.520 |

| Statin, n (%) | 952 (76.5%) | 3,202 (86.4%) | <0.001* | 937 (78.5%) | 916 (76.8%) | 0.302 |

| PPI/H2RA, n (%) | 337 (27.1%) | 1,167 (31.5%) | 0.003* | 322 (27.0%) | 334 (28.0%) | 0.582 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 88.23 ± 23.50 | 91.02 ± 21.50 | <0.001* | 88.36 ± 23.09 | 90.26 ± 21.82 | 0.051 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.56 ± 1.14 | 1.55 ± 1.10 | 0.801 | 1.56 ± 1.15 | 1.54 ± 1.05 | 0.666 |

| TCHO (mmol/L) | 4.35 ± 1.14 | 4.19 ± 1.15 | <0.001* | 4.34 ± 1.15 | 4.29 ± 1.19 | 0.316 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.29 ± 0.63 | 2.17 ± 0.65 | <0.001* | 2.27 ± 0.63 | 2.21 ± 0.66 | 0.066 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.17 ± 0.31 | 1.17 ± 0.31 | 0.513 | 1.18 ± 0.31 | 1.20 ± 0.31 | 0.058 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.10 (5.70, 7.00) | 6.30 (5.80, 7.30) | 0.022* | 6.10 (5.70, 7.00) | 6.10 (5.70, 7.00) | 0.890 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 1.35 (0.63, 3.34) | 1.20 (0.51, 3.30) | 0.139 | 1.32 (0.63, 3.33) | 1.19 (0.50, 3.02) | 0.075 |

Baseline characteristics for 50 and 100 mg/day aspirin in secondary prevention.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and percentage (%) for categorical variables. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; H2RA, histamine 2 receptor antagonist; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, aldosterone receptor antagonist; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; PSM, propensity score matching; TCHO, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; TIA, transient ischemic attacks; UA, unstable angina pectoris.

P-value <0.05 was considered nominally statistically significant.

3.3.2 Efficacy and safety outcomes

After adjustment, the incidence of MACE did not differ significantly between the 100 and 50 mg/day groups (2.31 vs. 2.71 events/100 patient-years, HR 0.861, 95% CI 0.506–1.464, P = 0.577). Additionally, there were no differences in the incidences of unstable angina pectoris, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, arteriosclerotic diseases requiring surgery or intervention, cardiovascular death, or TIA between the two groups (Table 4 and Figure 2). Bleeding events occurred in 63 (5.06%) patients in the 50 mg group and 366 (9.88%) patients in the 100 mg group. After adjustment, the incidence rates of any bleeding events (9.19 vs. 6.37 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.473, 95% CI 1.087–1.998, P = 0.015), minor bleeding events (9.10 vs. 6.06 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.541, 95% CI 1.116–2.127, P = 0.009), and gastrointestinal adverse events (7.10 vs. 3.53 events/100 patient-years, HR 1.943, 95% CI 1.291–2.925, P = 0.002) were higher in the 100 mg group than in the 50 mg group (Table 4 and Figure 3).

Table 4

| Outcome | Before PSM adjustment | After PSM adjustment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients with event/No. of treated patients (Incidence rate, events/100 patient-years) | HR (95% CI) 100 vs. 50 mg/day | P | No. of patients with event/No. of treated patients (Incidence rate, events/100 patient-years) | HR (95% CI) 100 vs. 50 mg/day | P | |||

| Aspirin 50 mg/day (n = 1,245) | Aspirin 100 mg/day (n = 3,706) | Aspirin 50 mg/day (n = 1,193) | Aspirin 100 mg/day (n = 1,193) | |||||

| Efficacy outcomes | ||||||||

| MACE | 28/1,245 (2.75) | 103/3,706 (2.73) | 1.017 (0.669–1.545) | 0.939 | 27/1,193 (2.71) | 28/1,193 (2.31) | 0.861 (0.506–1.464) | 0.577 |

| UA | 12/1,245 (1.18) | 44/3,706 (1.17) | 1.008 (0.532–1.910) | 0.980 | 12/1,193 (1.20) | 12/1,193 (0.99) | 0.800 (0.359–1.781) | 0.584 |

| Nonfatal MI | 4/1,245 (0.39) | 10/3,706 (0.27) | 0.680 (0.213–2.170) | 0.515 | 4/1,193 (0.40) | 3/1,193 (0.25) | 0.637 (0.143–2.848) | 0.555 |

| Nonfatal stroke | 5/1,245 (0.49) | 25/3,706 (0.66) | 1.347 (0.515–3.519) | 0.544 | 4/1,193 (0.40) | 5/1,193 (0.41) | 1.036 (0.278–3.862) | 0.957 |

| Arteriosclerotic diseases requiring surgery or intervention | 3/1,245 (0.29) | 12/3,706 (0.32) | 1.137 (0.320–4.036) | 0.842 | 3/1,193 (0.30) | 3/1,193 (0.25) | 0.879 (0.177–4.359) | 0.875 |

| Cardiovascular death | 2/1,245 (0.20) | 9/3,706 (0.24) | 1.174 (0.253–5.435) | 0.838 | 2/1,193 (0.20) | 3/1,193 (0.25) | 1.197 (0.200–7.175) | 0.844 |

| TIA | 2/1,245 (0.20) | 3/3,706 (0.08) | 0.520 (0.081–3.323) | 0.489 | 2/1,193 (0.20) | 2/1,193 (0.17) | 0.959 (0.129–7.103) | 0.967 |

| Safety outcomes | ||||||||

| Any bleeding | 63/1,245 (6.45) | 366/3,706 (10.12) | 1.598 (1.221–2.092) | <0.001* | 61/1,193 (6.37) | 106/1,193 (9.19) | 1.473 (1.087–1.998) | 0.015* |

| Minor bleeding (BARC 1–2) | 60/1,245 (6.15) | 363/3,706 (10.04) | 1.664 (1.263–2.191) | <0.001* | 58/1,193 (6.06) | 105/1,193 (9.10) | 1.541 (1.116–2.127) | 0.009* |

| Major bleeding (BARC 3–4) | 3/1,245 (0.31) | 2/3,706 (0.05) | 0.194 (0.032–1.163) | 0.073 | 3/1,193 (0.31) | 0 | - | - |

| Fatal bleeding (BARC 5) | 0 | 1/3,706 (0.03) | - | - | 0 | 1/1,193 (0.09) | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal adverse events | 41/1,245 (3.65) | 276/3,706 (8.37) | 2.386 (1.713–3.325) | <0.001* | 39/1,193 (3.53) | 76/1,193 (7.10) | 1.943 (1.291–2.925) | 0.002* |

Efficacy and safety outcomes for 50 and 100 mg/day aspirin in secondary prevention.

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; PSM, propensity score matching; TIA, transient ischemic attacks; UA, unstable angina pectoris.

P-value <0.05 was considered nominally statistically significant.

3.4 Analyses of risk factors for hemorrhagic events

The results from the univariable Cox regression analysis were as follows: aspirin dose, secondary prevention, current smoking, alcohol consumption, history of dyslipidemia, gastrointestinal diseases, and hemorrhage, and concomitant use of other antiplatelets, anticoagulants, β-blockers, ACEI/ARB/MRA, statins, and PPI/H2RA were associated with increased bleeding risk. In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, we found that aspirin dose (100 vs. 50 mg/day, HR 1.714, 95% CI 1.214–2.422, P = 0.002), history of dyslipidemia (HR 2.151; 95% CI 1.626–2.846, P < 0.001) and hemorrhage (HR 1.605; 95% CI 1.075–2.397, P = 0.021), and concomitant use of other antiplatelet (HR 1.613, 95% CI 1.202–2.165, P = 0.001) and anticoagulant drugs (HR 2.310, 95% CI 1.407–3.792, P < 0.001) were independent risk factors for bleeding (Table 5).

Table 5

| Characteristic | Univariable Cox analysis | Multivariable Cox analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.874 (0.737–1.035) | 0.119 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.287 (0.995–1.018) | 1.006 | ||

| Aspirin dose (100 vs. 50 mg/day) | 2.303 (1.738–2.793) | <0.001* | 1.714 (1.214–2.422) | 0.002* |

| Prevention level (secondary vs. primary) | 1.327 (1.086–1.621) | 0.006* | 0.818 (0.566–1.182) | 0.285 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | 0.845 (0.702–1.015) | 0.072 | ||

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | 1.707 (0.868–3.355) | 0.121 | ||

| Dyslipidemia (yes vs. no) | 1.655 (1.387–1.974) | <0.001* | 2.151 (1.626–2.846) | <0.001* |

| Gastrointestinal disease (yes vs. no) | 1.542 (1.273–1.868) | <0.001* | 1.107 (0.826–1.483) | 0.497 |

| Hemorrhage history (yes vs. no) | 2.236 (1.697–2.945) | <0.001* | 1.605 (1.075–2.397) | 0.021* |

| Current smoking (yes vs. no) | 3.002 (2.530–3.561) | <0.001* | 1.341 (0.961–1.871) | 0.085 |

| Current drinking (yes vs. no) | 2.742 (2.319–3.242) | <0.001* | 1.261 (0.936–1.698) | 0.128 |

| β-blocker (yes vs. no) | 1.338 (1.127–1.588) | <0.001* | 1.243 (0.940–1.645) | 0.127 |

| ACEI/ARB/MRA (yes vs. no) | 1.233 (1.026–1.481) | 0.025* | 1.147 (0.883–1.490) | 0.305 |

| Statin (yes vs. no) | 1.906 (1.487–2.443) | <0.001* | 0.757 (0.530–1.083) | 0.128 |

| PPI/H2RA (yes vs. no) | 1.311 (1.084–1.586) | 0.005* | 1.240 (0.925–1.663) | 0.150 |

| Concomitant use of other antiplatelets (yes vs. no) | 1.570 (1.320–1.867) | <0.001* | 1.613 (1.202–2.165) | 0.001* |

| Concomitant use of anticoagulants (yes vs. no) | 2.267 (1.537–3.344) | <0.001* | 2.310 (1.407–3.792) | <0.001* |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.984 (0.902–1.074) | 0.722 | ||

| TCHO (mmol/L) | 0.965 (0.894–1.041) | 0.354 | ||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.888 (0.769–1.025) | 0.105 | ||

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.882 (0.664–1.172) | 0.386 | ||

| eGFR (mL/min.1.73 m2) | 0.999 (0.996–1.003) | 0.610 | ||

| HbA1C (>6% vs. ≤6%) | 0.837 (0.654–1.071) | 0.158 | ||

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 1.001 (0.991–1.011) | 0.823 | ||

Features associated with bleeding events by univariable and multivariable Cox analysis.

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; H2RA, histamine 2 receptor antagonist; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HR, hazard ratio; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; MRA, aldosterone receptor antagonist; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; TCHO, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

P-value <0.05 was considered nominally statistically significant.

4 Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the LAPIS is the first nationwide, large-scale, multicenter, prospective observational cohort study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of different doses of aspirin for the primary and secondary prevention of CVD in older Chinese individuals. In this interim analysis of LAPIS, we found that aspirin 50 mg/day leads to similar cardiovascular benefits but fewer bleeding events than aspirin 100 mg/day in Chinese individuals aged 60 years and older.

In clinical applications, an increasing number of physicians tend to prescribe aspirin at lower dosages than recommended because of concerns about bleeding. The obtained data reflected the real-world decision-making tendency of clinicians to use aspirin for antiplatelet therapy in older adults. Lower-dose aspirin (50 mg/day) is used more frequently for older patients at a high risk of bleeding to balance the efficacy and safety of antithrombotic therapy, including for patients aged 75 years and older, women, patients with a history of bleeding, and those who require concomitant use of anticoagulant therapy. As stated above, the lowest effective dose of aspirin for long-term antiplatelet prophylaxis ranges between 50 and 100 mg/day, consistent with the saturability of platelet COX-1 inactivation at low doses (17), which was based on indirect comparisons of randomized controlled trials employing different aspirin dosing regimens (23), as well as on head-to-head randomized comparisons of different aspirin doses in patients with acute coronary syndromes and stable CVD (15, 24). Our study further contributed evidence supporting the efficacy of 50 mg aspirin in the older Chinese population, in either the primary or secondary prevention cohorts, which was consistent with previous findings (20). However, considering the insufficient median follow-up duration, this estimate requires a longer follow-up period.

Moreover, we examined the risks of bleeding and adverse gastrointestinal events associated with aspirin use. Aspirin is associated with an increased risk of bleeding and gastrointestinal lesions, such as mucosal erosions and ulcers (25); the gastrointestinal toxicity of aspirin is primarily attributed to the inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2 in the gastrointestinal mucosa, which impairs the physiological role of prostanoids in mucosal cytoprotection and tissue repair. Epidemiological studies and meta-analyses revealed that low-dose aspirin (≤100 mg/day) significantly increased the risk of major bleeding in East Asians compared with that in Caucasians (12, 26), especially in older individuals with complex medical conditions and multiple comorbidities, which is the focus of clinical attention. We found that aspirin 50 mg/day significantly decreased the incidence of bleeding and gastrointestinal adverse events compared with aspirin 100 mg/day, which suggests that older Chinese individuals and those at a high risk of bleeding or gastrointestinal events may benefit from aspirin 50 mg/day, in both primary and secondary prevention. In multivariable Cox regression analysis, we found that aspirin dose (100 vs. 50 mg/day), history of dyslipidemia and hemorrhage, and concomitant use of other antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs were independent risk factors for bleeding events. Elevated levels of circulating lipoproteins have been shown to increase the sensitivity of platelets to aggregation agonists, resulting in an increased tendency toward platelet activation and thrombus formation (27). In vitro studies have suggested that statins enhance the antiplatelet effects of aspirin; other studies have suggested that statins could have a direct antiplatelet effect, which constitutes part of their “pleiotropic” effects, which may explain the correlation between dyslipidemia and hemorrhage related to aspirin. However, the underlying biological mechanisms are not yet completely understood. Although currently available results may assist physicians in making individual clinical judgments regarding long-term aspirin use, they are insufficient to guide routine aspirin use in the general older population. Further long-term follow-up is needed to obtain reliable evidence.

4.1 Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations in our study. First, this was an interim analysis of the LAPIS with a relatively short follow-up period, and selection bias could not be excluded. Regarding the endpoint analysis, approximately 20% of the cohort completed the 24-month follow-up period (median follow-up of 183 days). Notably, half of the individuals were in the initial follow-up period, which might diminish the long-term effect estimates (28, 29); the limited follow-up time was inadequate to observe the bleeding and cardiovascular events of interest. Therefore, the findings of the interim analysis support the continuation of long-term follow-up studies to determine the effects and risks of aspirin. Second, most bleeding events were minor, and only 6 (0.09%) and 1 (0.01%) of 7,021 patients had major and fatal bleeding events during follow-up, respectively, precluding the assessment of associations between severe clinical hemorrhage and aspirin dose. Third, we used PSM to control for baseline differences between the aspirin 50 and 100 mg/day groups, which may have resulted in the loss of some samples and endpoint events. Even after adjusting for potential confounders, controlling for all factors influencing the outcomes remains challenging. Fourth, we did not assess the effects on outcomes between long-term aspirin users and aspirin-naïve individuals, as the cardiovascular benefits of aspirin may continue to provide additional clinical advantages beyond the current median duration. Fifth, it was inconvenient for some patients to visit the hospital for face-to-face interviews because of coronavirus disease 2019, and follow-up via phone or WeChat may have influenced the reporting of endpoint events. Additional data from long-term follow-up of the LAPIS are required to validate our findings. Furthermore, although PCI history was recorded, the precise timing of PCI (recent vs. remote PCI) was not collected, limiting our ability to assess potential differences related to recent PCI. Finally, information regarding the specific dosages of concomitant antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents was not available in our database. Consequently, we were unable to evaluate whether the doses of these agents differed between the groups or influenced the outcomes.

Conclusively, among older adults diagnosed with CVD or cardiovascular risk factors, there was no significant difference in the risk of major cardiovascular events between daily doses of aspirin (50 or 100 mg). Furthermore, aspirin 50 mg/day was associated with a lower risk of bleeding and gastrointestinal events than aspirin 100 mg/day. The estimated effect of optimal aspirin dosage for primary and secondary prevention requires long-term follow-up data.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Peking University First Hospital, approval number 2018(248). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XW: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization, Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology. HQ: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Data curation. YW: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation, Validation. HC: Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PH: Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation. YoL: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Data curation. ZY: Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. AJ: Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YH: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation. NH: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration, Validation. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration, Validation. YS: Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XQ: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation. KL: Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. HZ: Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LL: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Project administration. ZhengxZ: Validation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. YiL: Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PD: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Project administration. SX: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration. HL: Project administration, Validation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JY: Validation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. JHu: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Validation, Project administration. ZX: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. BL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration. HJ: Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XY: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation, Data curation. WM: Project administration, Validation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HG: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation. LZ: Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration. TT: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XS: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration. JHe: Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XC: Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ZW: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration, Validation. ZhenghZ: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Project administration. QL: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation. JW: Validation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ML: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Software, Investigation, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The low-dose aspirin for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in the elderly study (LAPIS) was supported by the Chinese Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics Medicine, Project 2019BD019 supported by PKUBaidu Fund and Project 2023HQ04 supported by Peking University First Hospital. The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and was responsible for the decision to submit it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the investigators of LAPIS, Shandong Xinhua Pharmaceutical Group Co. LTD., and Shanghai Ashermed Healthcare Communications LTD. for their administrative coordination and technical assistance to the LAPIS study. We would also like to acknowledge the participants and their families participating in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CIs, confidence intervals; COX-1, cyclooxygenase-1; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; H2RAs, histamine 2 receptor antagonists; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HRs, hazard ratios; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; MRAs, aldosterone receptor antagonists; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs); PSM, propensity score matching; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; SD, standard deviation; TCHO, total lipoprotein cholesterol; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

References

1.

Visseren FLJ Mach F Smulders YM Carballo D Koskinas KC Bäck M et al 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(34):3227–337. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484

2.

Virani SS Newby LK Arnold SV Bittner V Brewer LC Demeter SH et al 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2023) 148(9):e9–119. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168

3.

Atherosclerosis and Coronary Heart Disease Working Group of Chinese Society of Cardiology, Interventional Cardiology Working Group of Chinese Society of Cardiology Specialty Committee on Prevention and Treatment of Thrombosis of Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians Specialty Committee on Coronary Artery Disease and Atherosclerosis of Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Chinese Society of Cardiology and Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians expert consensus statement on dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Chin J Cardiol Dis. (2021) 49(05):432–54. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20210125-00088

4.

Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration, BaigentCBlackwellLCollinsREmbersonJGodwinJ. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. (2009) 373(9678):1849–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1

5.

McNeil JJ Wolfe R Woods RL Tonkin AM Donnan GA Nelson MR et al Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379(16):1509–18. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805819

6.

Arnett DK Blumenthal RS Albert MA Buroker AB Goldberger ZD Hahn EJ et al 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2019) 140(11):e596–646. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

7.

US Preventive Services Task Force, DavidsonKWBarryMJMangioneCMCabanaMChelmowDet alAspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. J Am Med Assoc. (2022) 327(16):1577–84. 10.1001/jama.2022.5207

8.

McNeil JJ Nelson MR Woods RL Lockery JE Wolfe R Reid CM et al Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379(16):1519–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955

9.

Ikeda Y Shimada K Teramoto T Uchiyama S Yamazaki T Oikawa S et al Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. (2014) 312:2510–20. 10.1001/jama.2014.15690

10.

Gaziano JM Brotons C Coppolecchia R Cricelli C Darius H Gorelick PB et al Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. (2018) 392:1036–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31924-X

11.

ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, BowmanLMafhamMWallendszusKStevensWBuckGet alEffects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:1529–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988

12.

Kim RB Li A Park KS Kang Y-S Navarese EP Gorog DA et al Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events comparing east Asians with westerners: a meta-analysis. JACC Asia. (2023) 3(6):846–62. 10.1016/j.jacasi.2023.07.008

13.

Kim HK Tantry US Smith SC Jr Jeong MH Park SJ Kim MH et al The east Asian paradox: an updated position statement on the challenges to the current antithrombotic strategy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemostasis. (2021) 121(4):422–32. 10.1055/s-0040-1718729

14.

Wang X Li L Cui J Cheng M Liu M . Myopenic obesity determined by fat mass percentage predicts risk of aspirin-induced bleeding in Chinese older adults. Clin Interv Aging. (2023) 18:585–95. 10.2147/CIA.S405559

15.

Jones WS Mulder H Wruck LM Pencina MJ Kripalani S Muñoz D et al Comparative effectiveness of aspirin dosing in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384(21):1981–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa2102137

16.

Fengchun Y Yanyan Q Bing G XueHong W FengLi Z et al Safety and efficacy of 50 mg enteric sustained-release aspirin tablet in secondary prevention of mild ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack. Chin J Stroke. (2021) 2021(07):657–63.

17.

Patrono C García Rodríguez LA Landolfi R Baigent C . Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. (2005) 353:2373–83. 10.1056/NEJMra052717

18.

Patrono C . Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(27):2362–76. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae324

19.

Chen XH Liu ML Qin MF Sun YM Tian T Li JQ et al Anti-aggregation effect and short-term safety evaluation of low-dose aspirin therapy in the elderly Chinese population: a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Chin Circ J. (2018) 33:457–62. 10.16439/j.cnki.1673-7245.2019.09.027

20.

Wang X Wang H Zheng Q Geng H Zhang J Fan Y et al Outcomes associated with 50 mg/d and 100 mg/d aspirin for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in Chinese elderly: single-center interim analysis of a multicenter, prospective, observational study. Int J Gen Med. (2022) 15:7089–100. 10.2147/IJGM.S384375

21.

Wang X Chen X Liu W Liang W Liu M . Rationale and design of LAPIS: a multicenter prospective cohort study to investigate the efficacy and safety of low-dose aspirin in elderly Chinese patients. Int J Gen Med. (2022) 15:8333–41. 10.2147/IJGM.S391259

22.

Mehran R Rao SV Bhatt DL Gibson CM Caixeta A Eikelboom J et al Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation. (2011) 123(23):2736–47. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449

23.

Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high-risk patients. Br Med J. (2002) 324:71–86. 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71

24.

CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators, MehtaSRBassandJPChrolaviciusSDiazREikelboomJWet alDose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. (2010) 363:930–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909475

25.

Andreotti F Geisler T Collet JP Gigante B Gorog DA Halvorsen S et al Acute, periprocedural and longterm antithrombotic therapy in older adults: 2022 update by the ESC working group on thrombosis. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(4):262–79. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac515

26.

Zhu Y Wang Y Shrikant B Tse LA Zhao Y Liu Z et al Socioeconomic disparity in mortality and the burden of cardiovascular disease: analysis of the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE)-China cohort study. Lancet Public Health. (2023) 8(12):e968–77. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00244-X

27.

Giordano S Franchi F Rollini F Al Saleh T Uzunoglu E Costa F et al Effect of lipid-lowering therapy on platelet reactivity in patients treated with and without antiplatelet therapy. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. (2024) 72(5):489–505. 10.23736/S2724-5683.23.06411-6

28.

Cofer LB Barrett TJ Berger JS . Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: time for a platelet-guided approach. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2022) 42(10):1207–16. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.318020

29.

Rothwell PM Price JF Fowkes FG Zanchetti A Roncaglioni MC Tognoni G et al Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: analysis of the time course of risks and benefits in 51 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. (2012) 379(9826):1602–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61720-0

Summary

Keywords

cardiovascular diseases, elderly, lower-dose aspirin, primary prevention, secondary prevention

Citation

Wang X, Qi H, Wu Y, Cong H, Hao P, Liu X, Liu Y, Yao Z, Jin A, Hou Y, He N, Zhao Y, Sun Y, Qian X, Liang K, Zhang H, Liu L, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Dou P, Xia S, Li H, Yang J, Hu J, Xia Z, Liu B, Jin H, Yan X, Miao W, Guo H, Zhao L, Zhang Q, Tian T, Sun X, He J, Chen X, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Liu Q, Wang J, Zhu S and Liu M (2026) The efficacy and safety of lower-dose aspirin for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in the elderly: an interim analysis of a multicenter, prospective, observational study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1615074. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1615074

Received

29 April 2025

Revised

14 December 2025

Accepted

24 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Pietro Enea Lazzerini, University of Siena, Italy

Reviewed by

Jonathan Shpigelman, SIU School of Medicine, Springfield, United States

Nischal Hegde, Bangalore Hospitals, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Qi, Wu, Cong, Hao, Liu, Liu, Yao, Jin, Hou, He, Zhao, Sun, Qian, Liang, Zhang, Liu, Zhang, Liu, Dou, Xia, Li, Yang, Hu, Xia, Liu, Jin, Yan, Miao, Guo, Zhao, Zhang, Tian, Sun, He, Chen, Wang, Zhang, Liu, Wang, Zhu and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Meilin Liu liumeilin@pku.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.