Abstract

Introduction:

Two predominant pathways contribute to ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) following donation after circulatory death (DCD): mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opening and Calpain-1 (CPN1) activation. Each pathway has established inhibitors; Cyclosporine A (CyA) and MDL-28170 (MDL), respectively, which are effective in modulating IRI in a DCD heart with 25 min of warm ischemia time (WIT). We studied the effect of co-administering CyA and MDL during reperfusion on infarct size and graft function in DCD rat hearts with extended WIT of 35 min.

Methods:

Male rats were exposed to 35 min of warm ischemia followed by 90 min of reperfusion. During reperfusion, hearts were given either 0.5 mM of CyA, 10 mM of MDL, or mixed CyA and MDL. Cardiac function and coronary flow rates were monitored throughout reperfusion and infarct size at the end of reperfusion.

Results:

Infarct size in hearts treated with mixed CyA + MDL (31.59 ± 7.1%) was less than that of MDL-treated hearts (33.26 ± 4.3%) but larger than CyA-treated hearts (25.49 ± 5.9%). Graft function and coronary flow rates were variable amongst groups. CyA-treated hearts had more profound infarct size reduction when compared to MDL, and no additional synergistic effect was seen with combination treatment.

Discussion:

Our results indicate that MPTP opening contributes significantly to the development of IRI in DCD hearts.

1 Introduction

Heart transplantation remains the “gold standard” treatment for patients with advanced, medically refractory heart failure. There is a persistent shortage of suitable hearts for transplantation. In 2022, the total number of patients awaiting transplantation was 7,519. This represents a 28% increase from 5,869 patients in 2011 (1). Donation after circulatory death (DCD) donor hearts have been increasingly used in the past decade, but the obligatory ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) that occurs with the DCD donation process, resulted in primary graft dysfunction in up to 45% of recipients (2). Concerns surrounding PGD have limited the warm ischemia time (WIT) to <30 min, thus only 19.7% of consented DCD hearts for transplantation were utilized (3–6). Since IRI is proportional to the duration of WIT, prolonged WIT (>30 min) was cited as the most common reasons for organ refusal.

While the mechanisms behind IRI are multi-factorial, two key pathways exist. The first is the activation of calcium-activated cysteine proteases, known as Calpains, found within the mitochondria and cytosol of cells (7). Calpain 1 (CPN1) and Calpain 2 (CPN2) are the two predominant isoforms and, when activated, they cleave both cytosolic and mitochondrial proteins. This leads to profound mitochondrial dysfunction through the generation of reactive oxygen species, reduction in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, and the release of proapoptotic proteins, ultimately resulting in cardiomyocyte cell death (8–10).

The second major pathway involves opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP). The MPTP is a non-selective pore found within the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and is typically closed, even during periods of ischemia (11). Upon reperfusion high concentrations of intracellular Ca2+ and the rapid normalization of cellular pH, results in the MPTP opening leading to the electron transport chain (ETC) uncoupling, mitochondrial swelling, and massive ionic shifts resulting in cell rupture. In addition, proapoptotic Cytochrome c, which activates Caspase-3 and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) are released ultimately leading to cell death (12–14).

Both CPN1/CPN2 and MPTP opening have known inhibitors; MDL-28170 (MDL) and Cyclosporine A (CyA), respectively. Previous work done by our lab has shown that at a dose of 10 μM MDL significantly reduced calpain activity compared to vehicle or 3 μM MDL (15). Furthermore, in a DCD rat heart, the administration of 10 μM of MDL, given throughout a period of ex-vivo reperfusion, significantly limited calpain activation, reduced infarct size and improved mitochondrial function, both oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and calcium retention capacity (CRC) (8, 16). Similarly we also demonstrate that 0.5 μM of CyA, administered for the first 15 min of a 90 min reperfusion period, reduced infarct size in DCD hearts and also resulted in significant improvement in OXPHOS and CRC function (17, 18). Our work on DCD hearts with CyA added to the already large body of work supporting the use of CyA to mitigate ISI in cardiomyocytes (19).

Our prior work on DCD heart IRI modulation was done with WIT of 25 min, simulating current clinical DCD heart transplantation practice. Given the promising results of using CyA and MDL individually to limit IRI in DCD hearts with 25 min of WIT, we explored whether administering CyA and MDL would have a synergistic response in a DCD heart with prolonged WIT. Our objective is to study the modulation of IRI with combination of CyA and MDL in a DCD heart with WIT of 35 min.

2 Materials and methods

All experimental animals were cared for in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (20). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University (protocol number AD10002961) and the Central Virginia VA Health Care System (protocol number 02253). Animals were obtained through Envigo (Inotiv, Inc) and were housed two per cage within a temperature and humidity-controlled vivarium with alternating 12-h light and dark cycles. The animals had continuous access to water and food (Inotiv Teklad LM-485 rat diet).

2.1 Preparation of rat hearts for ischemia and reperfusion

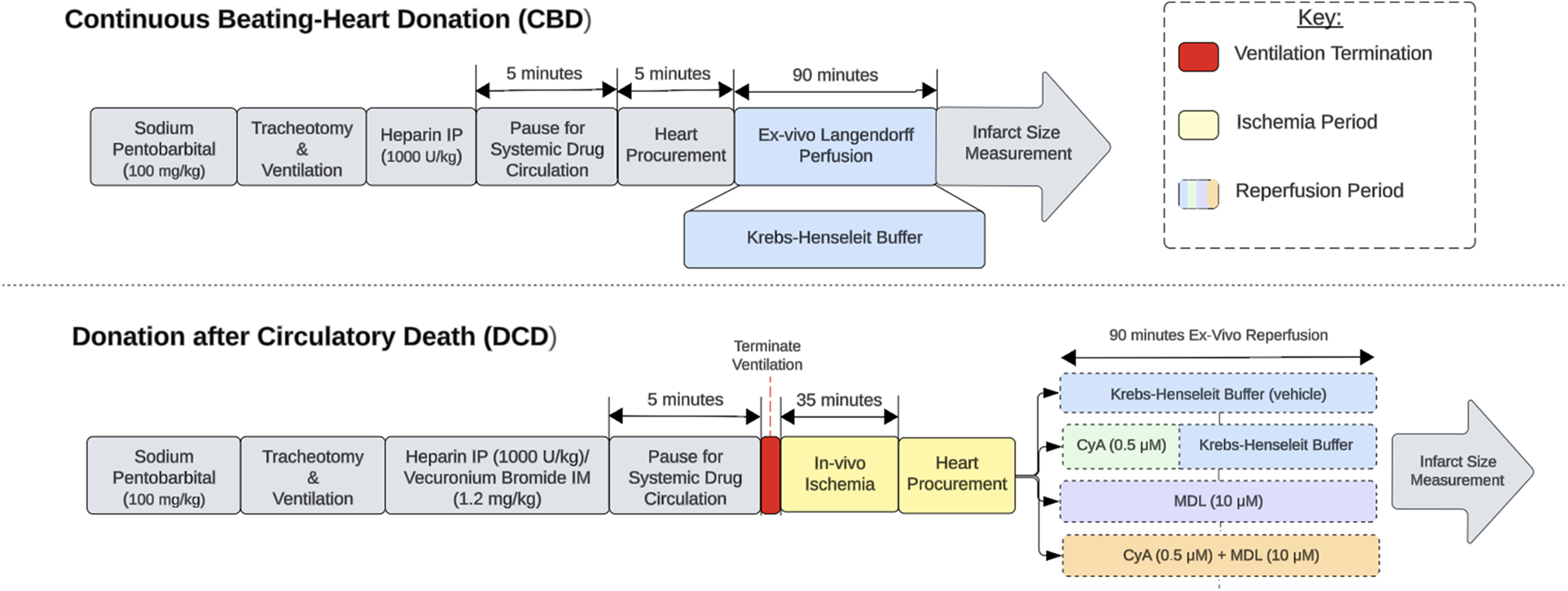

Male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing approximately 350–370 g, were separated into one of five groups based on their allotted ischemia time and treatment protocol (Table 1). Donor rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) (Sagent Pharmaceuticals, #0676-20). Once fully anesthetized, the neck was incised to expose the trachea. A small tracheotomy was made and a 14 g angio-catheter was inserted into the tracheal opening. This was connected to a small animal ventilator (RoVent® Advanced Small Animal Ventilator, Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT, USA) set to deliver a tidal volume of 2.65 mL at 70 breaths per minute. Next, electrocardiogram electrodes (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) were placed to continuously monitor the animals heart rate using an ADI Bio Amp and LabChart software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Next, intraperitoneal heparin (1,000 U/kg) (Fresenius Kabi, #403577) and intramuscular vecuronium bromide (1.2 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich, #76904) were administered for systemic anticoagulation and muscle paralysis, respectively. After 5-min ventilator support was terminated, thereby marking the start of the 35-min of warm ischemia period. The time from ventilatory termination to cardiac arrest was typically between 9 and 12 min, consistent with our previously published data (21). At approximately 33 min of ischemia time, the heart procurement process was started to allow enough time for placement of the heart on the Langendorff apparatus. Hearts from continuous beating-heart donors (CBD) were procured without ventilator termination or ischemia and served as a control (Figure 1).

Table 1

| Groups | Experimental protocol | Sample size |

|---|---|---|

| CBD | Without in vivo ischemia, hearts received 90 min of continuous K-H buffer perfusion from 2 L reservoir | N = 10 |

| DCD + Vehicle | After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts received 90 min of continuous K-H buffer perfusion from 2 L reservoir | N = 7 |

| DCD + CyA only | After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts received 15 min of 0.5 μM CyA in K-H buffer from 500 mL reservoir, followed by 75 min of perfusion with K-H buffer alone from 1,500 mL reservoir | N = 10 |

| DCD + MDL only | After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts were perfused with 10 μM MDL in K-H buffer for 90 min from 2 L reservoir | N = 8 |

| DCD + CyA + MDL mixed | After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts received a mixture of 0.5 μM CyA and 10 μM MDL mixed in 500 mL K-H buffer for the initial 15 min, followed by perfusion with 10 μM MDL alone in 1,500 mL K-H buffer for an additional 75 min, making a total MDL perfusion time of 90 min | N = 8 |

Experimental groups.

CBD, continue beating-heart donation; DCD, donation after circulatory death; Min, minute; N represents individual animals; CyA, cyclosporine A.

Figure 1

Experimental design. Experimental design comparing continuous beating-heart donation (CBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD) procedures. The red section indicates ventilator termination, which initiates the ischemic period. The yellow sections represent in-vivo ischemia periods, while the blue sections represent ex-vivo reperfusion on the Langendorff apparatus. The reperfusion period for DCD hearts is divided into 5 categories based on the treatment paradigm used.

2.2 Procedure for heart reperfusion and treatment

Once procured, hearts were mounted on a Langendorff apparatus and perfused at a constant pressure of 73 mmHg for 90 min. A small incision was made in the left atrium to insert a balloon catheter into the left ventricle. The catheter was connected to a physiological pressure transducer (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) to continuously record left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) using LabChart software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Hearts were perfused with modified Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) buffer [115 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.1 mM MgSO4, 0.9 mM KH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, and 5 IU/L regular insulin (Novo Nordisk Inc, #1833-11)] at 37 °C. The buffer was continuously oxygenated with 95% O2% and 5% CO2 to maintain a pH of 7.4. The experimental protocols for each group of animals are as follows:

CBD hearts: Without in vivo ischemia, hearts received 90 min of continuous K-H buffer perfusion from 2 L reservoir.

Vehicle hearts: After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts received 90 min of continuous K-H buffer perfusion from 2 L reservoir.

CyA (Sigma-Aldrich, #C3662): After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts received 15 min of 0.5 μM CyA in K-H buffer from 500 mL reservoir, followed by 75 min of perfusion with K-H buffer alone from 1,500 mL reservoir.

MDL (Sigma-Aldrich, #M6690): After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts were perfused with 10 μM MDL in K-H buffer for 90 min from 2 L reservoir.

CyA + MDL mixed: After 35 min of in vivo ischemia, hearts received a mixture of 0.5 μM CyA and 10 μM MDL mixed in 500 mL K-H buffer for the initial 15 min, followed by perfusion with 10 μM MDL alone in 1,500 mL K-H buffer for an additional 75 min, making a total MDL perfusion time of 90 min.

Heart rate and LVDP were recorded at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min of reperfusion. At the same time points, coronary effluent was collected to measure volume, and aliquots were stored at −80 °C for enzyme activity analysis. At the end of the 90-min reperfusion period, hearts were removed from the Langendorff apparatus, wrapped in foil, and stored at −20 °C for infarct size measurement.

2.3 Procedure for infarct size measurement

Frozen hearts were carefully sectioned along the long axis into four pieces, each approximately 2–3 mm thick. Sections were incubated in the 1% TTC solution at 37 °C for 20 min, then transferred to 10% formalin at 4 °C for ∼24 h to enhance tissue fixation. After formalin fixation, sections were dried, individually weighed, and placed between two clear plastic sheets for digital scanning. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to determine the percentage of infarcted tissue by weight.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10 Software (Boston, MA, USA). Normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Comparisons of means for infarct size and functional data between groups were made using a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Bonferroni correction if data passed the normality and equal distribution test. Data that failed the test of normality or equal distribution test were compared using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks followed by Dunn's analysis for multiple groups. A significance level of α < 0.05 was established a priori to analysis and all data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3 Results

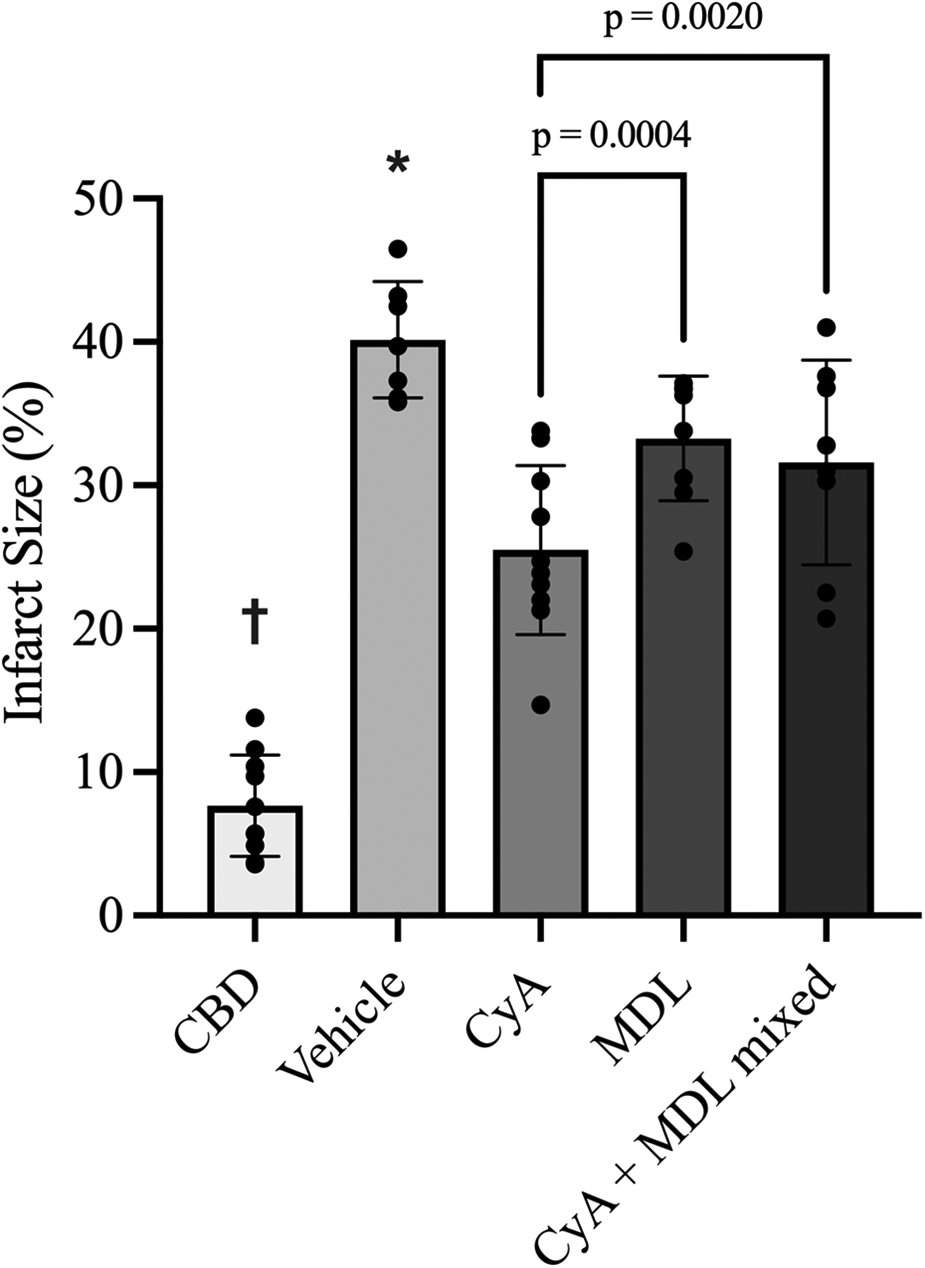

3.1 Infarct size reduction is more with CyA compared to MDL

TTC staining showed that CBD hearts without ischemia had the smallest infarct size (7.67 ± 3.53%), whereas vehicle treated hearts subjected to 35 min of ischemia had the largest infarct size (40.16 ± 4.06%). Compared to the vehicle group, infarct size was significantly reduced by CyA (25.49 ± 5.90%), MDL (33.26 ± 4.35%) and combination CyA + MDL (31.59 ± 7.14%) treatments. Moreover, infarct size in CyA-treated hearts was significantly lower than in MDL-treated hearts (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Infarct size measurements across experimental groups as measured using triphenyL–tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining and digital planimetry. Effects of MDL-28170 (MDL), cyclosporine A (CyA) and combination treatment on infarct size in DCD rat hearts following 35 min of ischemia. Infarct size in DCD hearts treated with CyA (25.49 ± 5.90%), MDL (33.26 ± 4.35%) and combination CyA + MDL (31.59 ± 7.14%) were significantly lower than vehicle hearts (40.16 ± 4.06%). Infarct size in hearts treated with mixed CyA + MDL was lower than that of MDL alone, but no statistically significant difference was noted. Furthermore, combination treatment did not exceed the infarct size reduction produced by CyA treatment alone. One-way analysis of variance used for statistical analysis. All data expressed as mean ± SD. † Represents statistical significance (p < 0.05) between CBD hearts and all other groups. * Represents statistical significance (p < 0.05) between vehicle hearts and all other groups.

3.2 CyA and MDL combination had marginal improvement in infarct size reduction

Infarct size in the CyA + MDL group (31.59 ± 7.14%) was significantly smaller than in vehicle hearts (40.16 ± 4.06%). However, the combination treatment did not reduce infarct size beyond that observed with CyA alone (Figure 2).

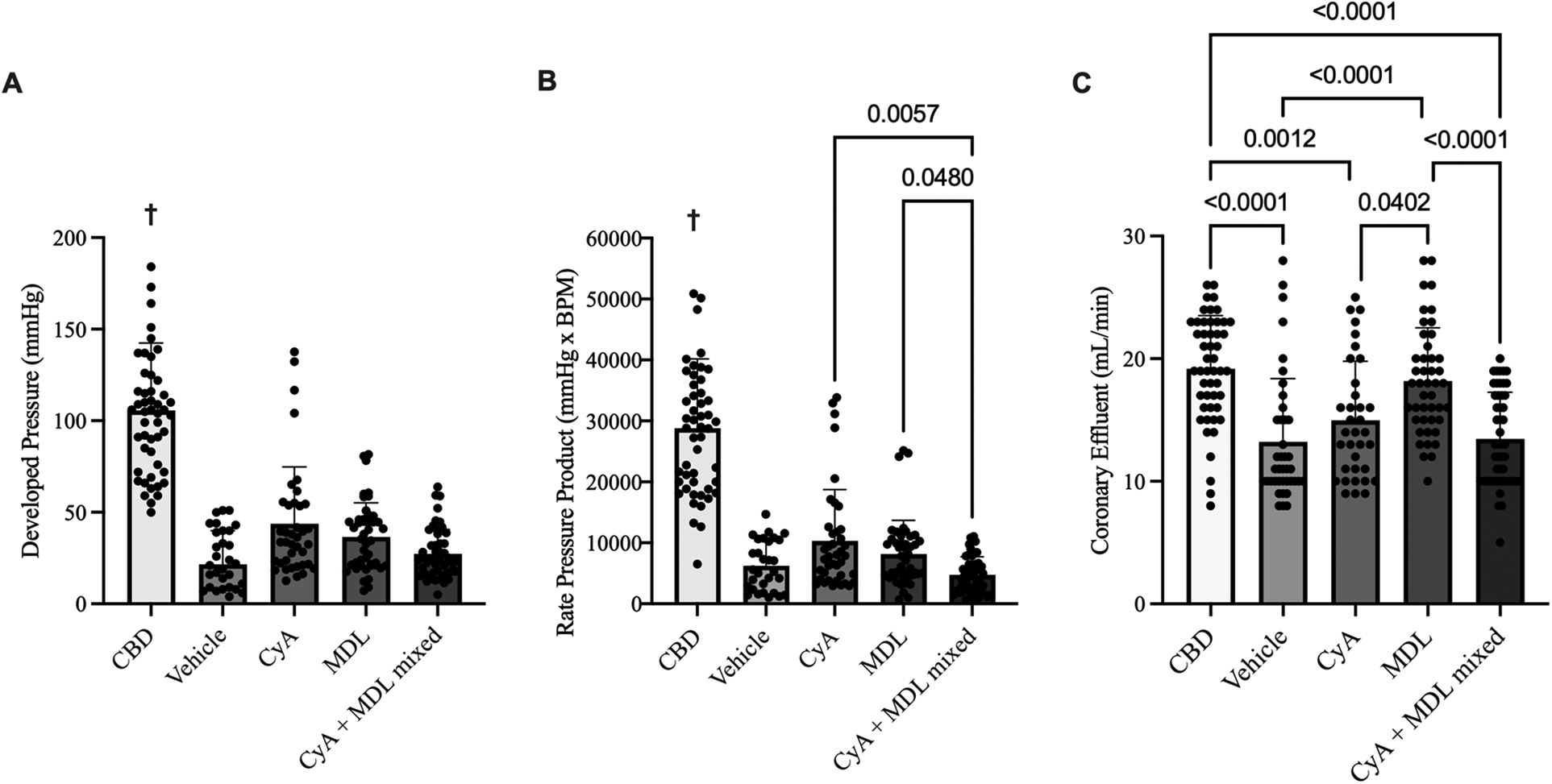

3.3 Limited synergistic effect of CyA and MDL combination on improving DCD heart function

Heart function was recorded continuously throughout reperfusion, with measurements taken at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min. These values were averaged for each group to generate aggregate LVDP and RPP. Overall, LVDP was highest in CBD hearts (105.60 ± 36.83 mmHg) and lowest in vehicle hearts (24.73 ± 15.49 mmHg). Among the treated hearts, LVDP was highest in the CyA group (43.71 ± 31.05 mmHg), followed by the MDL group (36.52 ± 18.61 mmHg), and the mixed CyA + MDL group (27.22 ± 13.45 mmHg) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3

Comparison of aggregated left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) (A), rate pressure product (RPP) (B), and coronary effluent (C) across experimental groups. A balloon catheter connected to a pressure transducer was placed into the left ventricle to record LVDP and RPP throughout the 90 min of reperfusion. Of the treated hearts, LVDP was highest in the CyA group (43.71 ± 4.97 mmHg) and lowest in the mixed CyA + MDL group (27.22 ± 13.45 mmHg). No differences were noted between the mixed CyA + MDL group and CyA-treated (43.71 ± 31.05 mmHg) or MDL treated (36.52 ± 18.61 mmHg) hearts. Of the treated hearts, RPP was highest in the CyA-treated hearts (10,332 ± 8,417 mmHg*BPM) and lowest in the mixed CyA + MDL group (4,747 ± 2,965 mmHg*BPM). Coronary effluent was collected for 1 min at 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min of reperfusion. Flow rates varied between groups, with the highest rate in the MDL-treated hearts (18.18 ± 4.35 mL/min) and lowest in the mixed CyA + MDL group (13.46 ± 3.81 mL/min). One-way analysis of variance used for statistical analysis. All data expressed as mean ± SD. † Represents statistical significance (p < 0.05) between CBD hearts and all other groups.

Across all groups, RPP (mmHg·BPM) was highest in CBD hearts (28,816 ± 11,348) and lowest in vehicle hearts (6,245 ± 4,045). Among the treatment groups, RPP was highest in CyA-treated hearts (10,332 ± 8,417), followed by the MDL group (8,174 ± 5,507), and the CyA + MDL group (4,747 ± 2,965) (Figure 3B).

Coronary effluent was collected for 1 min at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min of reperfusion to determine flow rate, and the values were averaged for each group. Flow rate was highest in CBD hearts (19.18 ± 4.35 mL/min) and lowest in vehicle hearts (13.23 ± 5.15 mL/min). Among the treated hearts, flow rate was highest in the MDL group (19.18 ± 4.35 mL/min), followed by the CyA group (14.97 ± 4.81 mL/min), and the mixed CyA + MDL group (13.46 ± 3.81 mL/min). Significant differences were observed between CyA- and MDL-treated hearts, as well as between MDL-treated and combination-treated hearts (Figure 3C).

4 Discussion

The first human heart transplant, performed by Christiaan Barnard in 1967, was done using a DCD donor. Over the ensuing five decades, the practice of DCD transplantation had largely been replaced by DBD donation. Unfortunately, the rate of DBD hearts made available for donation has not met the growing demand (22). To help alleviate this shortage, the use of DCD donor hearts resumed in 2014. Early data indicated no difference in operative mortality or survival when using DCD hearts compared to DBD hearts (23, 24).

One of the major factors limiting the use of DCD hearts is the requisite ischemic period compounded by injury that occurs at the time of reperfusion. It has been previously demonstrated through large animal and limited human heart experiments that DCD hearts are recoverable with WITs of up to 30 min (25, 26). As such, over 80% of donated DCD hearts with WIT longer than 30 min are typically unused for the fear of primary graft dysfunction, thereby contributing to the deficiency of hearts for transplant. Previous work by our group has established that beyond 25 min of WIT, DCD rat hearts sustain significant injury and are unable to regain acceptable levels of function following reperfusion (27). Our lab has also studied that administration of CyA or MDL, at the time of reperfusion, significantly reduces infarct size in DCD rat hearts with 25 min of WIT. The present study explores whether co-administration of both CyA and MDL would have synergistic benefit on DCD heart with prolonged WIT (35 min).

DCD hearts sustain injury during both the ischemic period as well as at the time of reperfusion. In addition, it has been established that IRI is proportional to the duration of ischemia. In fact, reperfusion injury can account for up to 50% of the injury sustained by these hearts (11). This is important to note as per the DCD organ procurement stipulations, the reperfusion period is the only time during which interventions may be applied. Much of the injury following reperfusion occurs secondary to mitochondrial damage, specifically the damaged electron transport chain (ETC) as well as degradation of mitochondrial structural proteins (28, 29). While the exact mechanisms behind these events are multifactorial, MPTP opening and CPN1/CPN2 activation are key mediators and each have well-established inhibitors; CyA and MDL, respectively (9, 30, 31).

Our results demonstrate several findings related to the use of CyA and MDL in limiting IRI in DCD rat hearts. First, while the use of CyA or MDL reduced infarct size in rat hearts following 35 min of ischemia compared to untreated hearts, the reduction was more profound in the CyA-treated hearts. CyA reduces cardiac injury by inhibiting MPTP, whereas MDL mitigates injury by protecting structural proteins through inhibition of ubiquitous calpains. We therefore sought to extend this work by combining CyA and MDL to determine whether a synergistic effect could be achieved by targeting different mechanisms. A modest reduction in infarct size was observed in hearts treated with the combination of CyA and MDL compared to MDL alone. It is well established that there is a unique interplay between CyA and its target, Cyclophilin-D (CyP-D), to inhibit MPTP opening at the time of reperfusion (32, 33). In addition, it has been shown that administration of MDL can also decrease MPTP opening in mouse hearts, despite this not being its primary mechanism of action (28). Perhaps sharing the common pathway on MPTP could have negated the synergistic benefits of combined treatment.

What is less known is how these compounds interact with other key mediators of MPTP opening, such as the adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) and phosphate carrier (PiC). While CyP-D plays a key role in MPTP opening, previous work has shown that even in the absence of CyP-D, or in the presence of CyA, the MPTP can continue to remain open, specifically in environments with higher concentrations of Ca2+ or reactive oxygen species (ROS) (34–36), as would be seen in these experiments with prolonged WIT. In these situations, mediators such as ANT or PiC may play a more dominant role even if not essential for MPTP opening and more research into their interactions with CyA and MDL are needed to potentially better understand these observations.

Similar to infarct size, both CyA- and MDL-treated hearts showed improvements in LVDP and RPP compared to untreated controls. Interestingly, hearts treated with the combination of CyA and MDL exhibited the poorest functional performance among all treatment groups. Cardiac function can be influenced by both the extent of myocardial infarction and myocardial stunning, particularly during the acute reperfusion phase. This phenomenon was first reported by Hendrick et al., who demonstrated that reperfused myocardial tissue exhibited diminished contraction following a 15-min period of ischemia, even in the absence of significant infarction. They further noted that the tissue was able to recover function after 48 h (37). Previous work from our lab corroborates these findings, showing that CyA-treated DCD hearts exhibited discordant functional data relative to their reduction in infarct size but were able to recover function 48 h after heterotopic transplantation (17). Given the prolonged WIT used in this study combined with a 90-min reperfusion period, it is reasonable to suggest that these conditions contributed to the observed functional outcomes, and that longer reperfusion periods might allow many of the trends reported to reach statistical significance.

The present study has several limitations. While Langendorff reperfusion is a well-established and widely used method for ex vivo reperfusion, it does not impose afterload on the heart as a working heart model would, which could affect the interpretation of functional data. Additionally, although K-H buffer is commonly used as a perfusate for ex vivo reperfusion, it does not replicate the chemistry of whole blood, particularly its oxygen-carrying capacity, which may influence infarct size measurements. We also acknowledge that, although this study focuses on the augmentation of MPTP opening and calpain activation, cardiomyocyte injury is a multifactorial process, and other pathways of cell death, such as ferroptosis, should be considered. Future studies investigating the interplay between these pathways and their contribution to cardiac injury would enhance our understanding of ischemia–reperfusion injury. Furthermore, the optimal dose and timing of both CyA and MDL remain unclear. Different dose combinations or variations in the timing of administration could potentially yield more pronounced reductions in infarct size. Finally, while myocardial stunning is a plausible explanation for the discordance between significant infarct size reductions and the lack of proportionate improvements in functional data, this would need to be confirmed using imaging techniques such as MRI or PET, which could be pursued in future studies involving heterotopic transplantation.

5 Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that both CyA and MDL, given at the time of reperfusion, significantly reduce infarct size in DCD rat hearts following 35 min of ischemia. In addition, the reduction in infarct size is more profound in CyA-treated hearts compared to MDL-treated hearts. No significant synergistic effect in reducing infarct size was seen with CyA and MDL combination. While not conclusive, these results suggest that MPTP opening may have a more prominent role in the development of IRI over CPN1/CPN2 activation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Protocol Number AD10002961. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. QC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MQ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by: Veterans Administration Merit Review grant (grant ID CARA-015-17S, award no. I01 BX003859) awarded to MQ. VETAR Surgery Department Fund, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond VA, awarded to MQ. The Thoracic Surgery Foundation resident research fellowship award, awarded to ZK.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author QC declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Colvin MM Smith JM Ahn YS Handarova DK Martinez AC Lindblad KA et al OPTN/SRTR 2022 annual data report: heart. Am J Transplant. (2024) 24:S305–93. 10.1016/j.ajt.2024.01.016

2.

Messer S Rushton S Simmonds L Macklam D Husain M Jothidasan A et al A national pilot of donation after circulatory death (DCD) heart transplantation within the United Kingdom. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2023) 42:1120–30. 10.1016/j.healun.2023.03.006

3.

Chew HC Iyer A Connellan M Scheuer S Villanueva J Gao L et al Outcomes of donation after circulatory death heart transplantation in Australia. J Am Coll Cardiol (2019) 73:1447–59. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.067

4.

Jennings RB Sommers HM Smyth GA Flack HA Linn H . Myocardial necrosis induced by temporary occlusion of a coronary artery in the dog. Arch Pathol. (1960) 70:68–78.

5.

Schroder JN Scheuer S Catarino P Caplan A Silvestry SC Jeevanandam V et al The American association for thoracic surgery 2023 expert consensus document: adult cardiac transplantation utilizing donors after circulatory death. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2023) 166:856–69.e5. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2023.03.014

6.

Dann TM Spencer BL Wilhelm SK Drake SK Bartlett RH Rojas-Pena A et al Donor heart refusal after circulatory death: an analysis of united network for organ sharing refusal codes. JTCVS Open. (2024) 18:91–103. 10.1016/j.xjon.2024.02.010

7.

Chen Q Lesnefsky EJ . Heart mitochondria and calpain 1: location, function, and targets. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2015) 1852:2372–8. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.08.004

8.

Chen Q Paillard M Gomez L Ross T Hu Y Xu A et al Activation of mitochondrial μ-calpain increases AIF cleavage in cardiac mitochondria during ischemia–reperfusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2011) 415:533–8. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.037

9.

Chen Q Thompson J Hu Y Dean J Lesnefsky EJ . Inhibition of the ubiquitous calpains protects complex I activity and enables improved mitophagy in the heart following ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol. (2019) 317:C910–21. 10.1152/ajpcell.00190.2019

10.

Cao T Fan S Zheng D Wang G Yu Y Chen R et al Increased calpain-1 in mitochondria induces dilated heart failure in mice: role of mitochondrial superoxide anion. Basic Res Cardiol. (2019) 114:17. 10.1007/s00395-019-0726-1

11.

Yellon DM Hausenloy DJ . Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. (2007) 357:1121–35. 10.1056/NEJMra071667

12.

Hunter DR Haworth RA . The Ca2+-induced membrane transition in mitochondria. I. The protective mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys. (1979) 195:453–9. 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90371-0

13.

Haworth RA Hunter DR . The Ca2+-induced membrane transition in mitochondria. II. Nature of the Ca2 + Trigger site. Arch Biochem Biophys. (1979) 195:460–7. 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90372-2

14.

Hunter DR Haworth RA . The Ca2+-induced membrane transition in mitochondria. III. Transitional Ca2 + Release. Arch Biochem Biophys. (1979) 195:468–77. 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90373-4

15.

Thompson J Hu Y Lesnefsky EJ Chen Q . Activation of mitochondrial calpain and increased cardiac injury: beyond AIF release. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2016) 310:H376–84. 10.1152/ajpheart.00748.2015

16.

Chen Q Kiernan Z Labate GM Quader M . Abstract 4142203: reducing reperfusion injury in circulatory death hearts with calpain inhibitor. Circulation. (2024) 150. 10.1161/circ.150.suppl_1.4142203

17.

Quader M Akande O Cholyway R Lesnefsky EJ Toldo S Chen Q . Infarct size with incremental global myocardial ischemia times: cyclosporine A in donation after circulatory death rat hearts. Transplant Proc. (2023) 55:1495–503. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2023.03.088

18.

Kiernan Z Labate G Chen Q Lesnefsky EJ Quader M . Infarct size reduction with cyclosporine A in circulatory death rat hearts: reducing effective ischemia time with therapy during reperfusion. Circ Heart Fail. (2024) 17:e011846. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.124.011846

19.

Hefler J Marfil-Garza BA Campbell S Freed DH Shapiro AMJ . Preclinical systematic review & meta-analysis of cyclosporine for the treatment of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Transl Med. (2022) 10:954. 10.21037/atm-22-618

20.

National Research Council (U.S.), Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (U.S.), National Academies Press (U.S.). Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2011).

21.

Quader M Akande O Toldo S Cholyway R Kang L Lesnefsky EJ et al The commonalities and differences in mitochondrial dysfunction between ex vivo and in vivo myocardial global ischemia rat heart models: implications for donation after circulatory death research. Front Physiol. (2020) 11:681. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00681

22.

Klassen DK Edwards LB Stewart DE Glazier AK Orlowski JP Berg CL . The OPTN deceased donor potential study: implications for policy and practice. Am J Transplant. (2016) 16:1707–14. 10.1111/ajt.13731

23.

Messer S Page A Axell R Berman M Hernández-Sánchez J Colah S et al Outcome after heart transplantation from donation after circulatory-determined death donors. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2017) 36:1311–8. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.10.021

24.

Messer S Cernic S Page A Berman M Kaul P Colah S et al A 5-year single-center early experience of heart transplantation from donation after circulatory-determined death donors. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2020) 39:1463–75. 10.1016/j.healun.2020.10.001

25.

Ali AA White P Xiang B Lin H-Y Tsui SS Ashley E et al Hearts from DCD donors display acceptable biventricular function after heart transplantation in pigs. Am J Transplant. (2011) 11:1621–32. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03622.x

26.

White CW Messer SJ Large SR Conway J Kim DH Kutsogiannis DJ et al Transplantation of hearts donated after circulatory death. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2018) 5:8. 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00008

27.

Akande O Chen Q Toldo S Lesnefsky EJ Quader M . Ischemia and reperfusion injury to mitochondria and cardiac function in donation after circulatory death hearts- an experimental study. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0243504. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243504

28.

Lesnefsky EJ Chen Q Hoppel CL . Mitochondrial metabolism in aging heart. Circ Res. (2016) 118:1593–611. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307505

29.

Lesnefsky EJ Chen Q Tandler B Hoppel CL . Mitochondrial dysfunction and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion: implications for novel therapies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. (2017) 57:535–65. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103335

30.

Griffiths EJ Halestrap AP . Protection by cyclosporin A of ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage in isolated rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (1993) 25:1461–9. 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1162

31.

Griffiths EJ Halestrap AP . Further evidence that cyclosporin A protects mitochondria from calcium overload by inhibiting a matrix peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase. Implications for the immunosuppressive and toxic effects of cyclosporin. Biochem J. (1991) 274 (Pt 2):611–4. 10.1042/bj2740611

32.

Connern CP Halestrap AP . Purification and N-terminal sequencing of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase from rat liver mitochondrial matrix reveals the existence of a distinct mitochondrial cyclophilin. Biochem J. (1992) 284 (Pt 2):381–5. 10.1042/bj2840381

33.

Halestrap AP Richardson AP . The mitochondrial permeability transition: a current perspective on its identity and role in ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2015) 78:129–41. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.018

34.

Baines CP Kaiser RA Purcell NH Blair NS Osinska H Hambleton MA et al Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature. (2005) 434:658–62. 10.1038/nature03434

35.

Nakagawa T Shimizu S Watanabe T Yamaguchi O Otsu K Yamagata H et al Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature. (2005) 434:652–8. 10.1038/nature03317

36.

Basso E Fante L Fowlkes J Petronilli V Forte MA Bernardi P . Properties of the permeability transition pore in mitochondria devoid of cyclophilin D. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:18558–61. 10.1074/jbc.C500089200

37.

Heyndrickx GR Baig H Nellens P Leusen I Fishbein MC Vatner SF . Depression of regional blood flow and wall thickening after brief coronary occlusions. Am J Physiol. (1978) 234:H653–9. 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.6.H653

Summary

Keywords

cyclosporine A, donation after circulatory death, heart failure, MDL-28170, MPTP

Citation

Kiernan Z, Labate G, Chen Q and Quader M (2026) Reducing mitochondrial dysfunction through combination therapy to limit ischemia-reperfusion injury in male DCD rats. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1625385. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1625385

Received

09 May 2025

Revised

12 December 2025

Accepted

30 December 2025

Published

21 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Hendrik Tevaearai Stahel, University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Antonietta Franco, Humanitas University, Italy

Yu Liu, First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kiernan, Labate, Chen and Quader.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mohammed Quader mohammed.quader@vcuhealth.org

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.