Abstract

Background:

Myocardial bridging (MB), once considered benign, is increasingly recognized for its role in myocardial ischemia, especially when coexisting with proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery stenosis. Optimal revascularization strategies remain uncertain for such dual pathology. This study assessed whether a fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)-optimized percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach improves outcomes in this population.

Methods:

In this retrospective single-center study, 238 patients with moderate MB and proximal intermediate LAD stenosis were enrolled. Patients were stratified based on FFR measurements: those with FFR > 0.80 received medical therapy alone (n = 96), while patients with FFR ≤ 0.80 underwent IVUS-guided PCI (n = 142). Baseline characteristics, procedural data, and two-year follow-up outcomes were compared. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were recorded, and multivariate regression analysis identified predictors of poor outcomes.

Results:

Patients undergoing PCI (FFR ≤ 0.80) had significantly lower MACE rates than those managed conservatively (7.7% vs. 18.8%, p = 0.019), mainly due to reduced angina-related rehospitalization. PCI was an independent protective factor (Hazard Ratio = 0.526, p = 0.034). Among PCI patients, stent extension into the MB segment was linked with higher MACE incidence (18.6% vs. 3.0%, p = 0.001). IVUS revealed that stent extension correlated with severe MB compression, shorter distance between lesions, and more frequent dissections. Two anatomical factors—short MB-proximal lesion distance and MB dissection—were predictive of poor outcomes post-MB stenting.

Conclusions:

An FFR-guided, IVUS-supported PCI strategy improves clinical outcomes in patients with MB and proximal LAD stenosis, particularly when avoiding stent placement in dynamically compressed MB segments. Procedural planning using IVUS and careful lesion assessment is essential. Functional evaluation alone may underestimate ischemia in MB; integration of anatomical and diastolic functional indices is recommended.

1 Introduction

Although coronary angiography (CAG) has historically served as the gold standard for evaluating coronary artery stenosis, accumulating evidence highlights a frequent discordance between angiographic severity and the actual presence of functional ischemia (1). As a result, there is an increasing emphasis on integrating both anatomical and physiological data to improve the accuracy of revascularization decision-making (2). Fractional flow reserve (FFR), an invasive physiologic metric, provides a quantitative assessment of the hemodynamic relevance of coronary stenoses. Multiple large-scale randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guided by FFR significantly decreases adverse clinical events compared to strategies based solely on angiography or medical therapy (3, 4). Reflecting this evidence, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines now advocate the use of FFR in evaluating intermediate coronary lesions and shaping interventional strategies (5).

Beyond physiologic assessment, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) plays a pivotal role in optimizing PCI procedures. By offering high-resolution visualization of vessel morphology, plaque composition, and stent-related parameters such as expansion and apposition, IVUS enhances procedural precision (6). Several clinical trials have indicated that IVUS-guided PCI yields superior outcomes compared to angiographic guidance alone (7, 8). Nevertheless, IVUS has conventionally been regarded as an adjunct imaging tool rather than a primary determinant in revascularization strategy formulation.

Myocardial bridging (MB), a congenital coronary anomaly characterized by an intramyocardial course of a coronary segment rather than the typical epicardial trajectory, has gained renewed attention (9). Once considered benign, MB is now recognized to be linked with a spectrum of clinical manifestations, including myocardial ischemia (10), coronary vasospasm (11), acute coronary syndrome(ACS) (12), exercise-induced arrhythmias (13), myocardial stunning (14), syncope, and even sudden cardiac death (15). Notably, MB is frequently accompanied by atherosclerotic plaque accumulation in the proximal segment of the tunneled artery. These plaques are often unstable and susceptible to rupture, thereby elevating the risk of thrombosis and acute coronary events (16).

Interventionally treating MB with stent implantation has produced suboptimal long-term outcomes, primarily due to elevated risks of in-stent restenosis, thrombosis, and mechanical complications such as stent fracture (9). Although surgical interventions such as myotomy or coronary artery bypass grafting are available, their associated procedural risks remain high (17). Consequently, medical management is generally preferred for most MB cases. However, in patients with concurrent MB and proximal intermediate coronary stenosis, the resultant hemodynamic interplay may mimic the effects of serial lesions, significantly impairing myocardial perfusion. MB has been shown to delay diastolic coronary flow, particularly in individuals with diastolic dysfunction (18). This temporal overlap during the cardiac cycle can intensify ischemic burden, suggesting the need for a more proactive therapeutic approach. Nonetheless, data on optimal revascularization strategies in such scenarios remain sparse.

This study aims to evaluate the clinical value of FFR in guiding therapy for patients with moderate MB and proximal intermediate coronary stenosis with documented ischemia. An integrated approach combining CAG, FFR, and IVUS is applied, with PCI performed under IVUS guidance in patients with FFR ≤ 0.80.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study participants

This retrospective, single-center observational study was carried out in the Department of Cardiology at Xiangtan Central Hospital. Patients consecutively admitted between June 2017 and December 2022 for elective PCI, with symptoms of severe exertional angina, confirmed myocardial ischemia, or non-emergent ACS, were screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria required CAG confirmation of isolated moderate MB in the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) artery—characterized by systolic compression between 50% and 70%—in conjunction with proximal intermediate coronary stenosis. A total of 238 patients met the selection criteria and provided informed consent. Participants were categorized into two groups based on FFR outcomes: those with FFR > 0.80 (n = 96) received optimal medical therapy alone, while patients with FFR ≤ 0.80 (n = 142) underwent IVUS-guided PCI with implantation of at least one drug-eluting stent (DES) in the proximal lesion, followed by routine medical management. Clinical demographics, comorbidities, laboratory parameters, imaging findings from CAG and IVUS, procedural details, and follow-up outcomes were retrospectively retrieved from the institutional electronic records and imaging archive. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) and was approved by the Xiangtan Central Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. X2019432). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants; verbal consent was documented per institutional protocols when written consent could not be acquired.

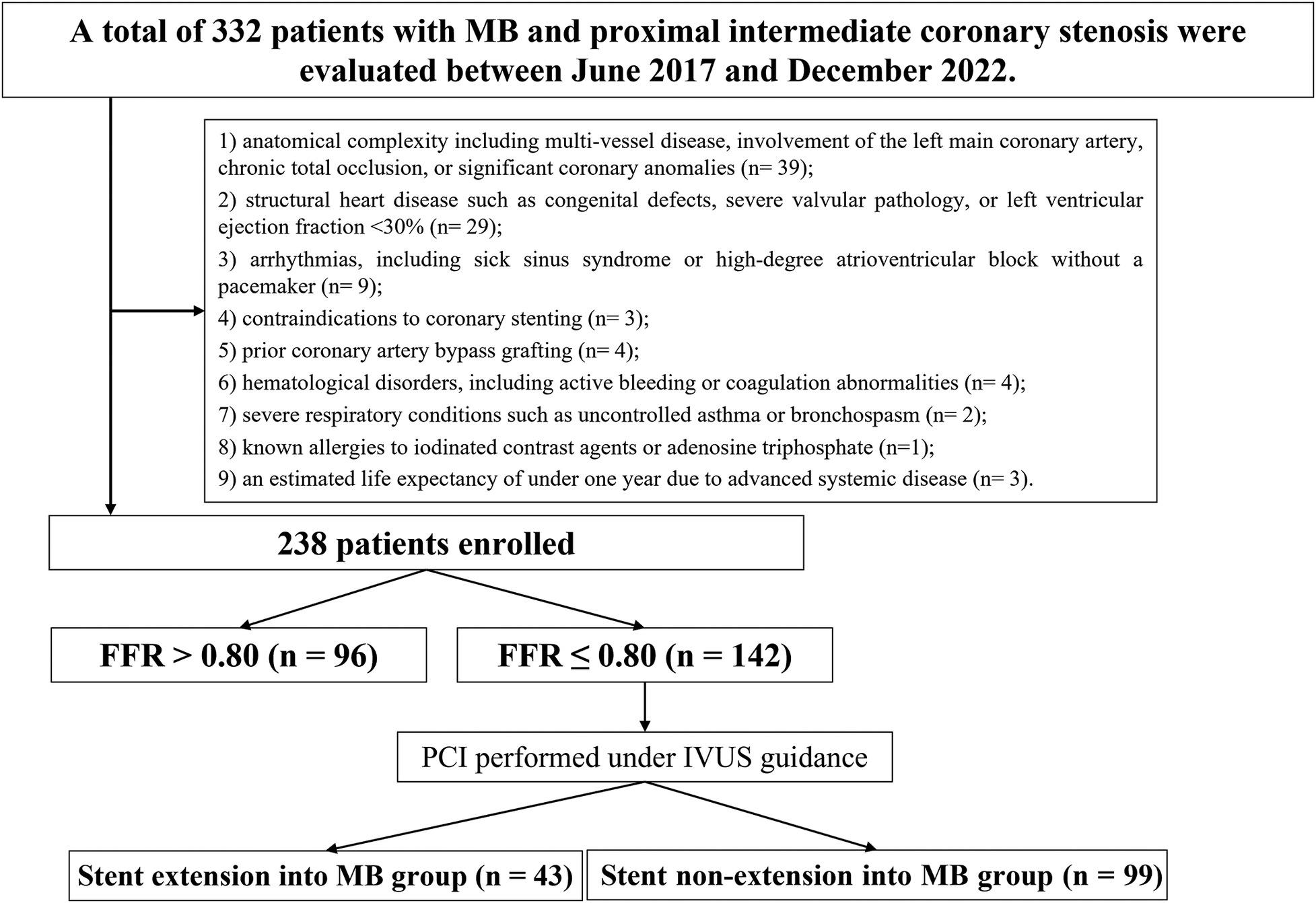

Eligibility was based on diagnostic standards set by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) for unstable angina (UA), non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), or stable coronary artery disease (CAD) with objective ischemia, and all participants were scheduled for elective PCI (19). Additional criteria included: (1) angiographic evidence of moderate MB, defined as transient systolic narrowing of 50%–70% in multiple views with diastolic luminal recovery (i.e., the classical “milking effect”) (20); (2) proximal intermediate coronary stenosis, defined as 50%–70% luminal narrowing within 10 mm upstream of the bridged segment (21); and (3) single-vessel disease, with all other lesions either showing <20% stenosis or having undergone previous revascularization. Myocardial ischemia was confirmed by at least one of the following: transient ST-segment depression during angina episodes; a positive treadmill test accompanied by typical symptoms and ≥2 min ST-segment depression; echocardiographic evidence of regional wall motion abnormalities; or abnormal perfusion results on stress nuclear myocardial imaging (22). Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) anatomical complexity including multi-vessel disease, involvement of the left main coronary artery, chronic total occlusion, or significant coronary anomalies; (2) structural heart disease such as congenital defects, severe valvular pathology, or left ventricular ejection fraction <30%; (3) arrhythmias, including sick sinus syndrome or high-degree atrioventricular block without a pacemaker; (4) contraindications to coronary stenting; (5) prior coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG); (6) hematological disorders, including active bleeding or coagulation abnormalities; (7) severe respiratory conditions such as uncontrolled asthma or bronchospasm; (8) known allergies to iodinated contrast agents or adenosine triphosphate (ATP); and (9) an estimated life expectancy of under one year due to advanced systemic disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study flowchart. MB, myocardial bridging; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; FFR, fractional flow reserve.

2.2 FFR measurement

FFR was measured using a standard protocol with a PressureWire™ Certus™ pressure guidewire (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) connected to a dedicated analyzer system. The pressure wire was advanced 3–5 cm distal to the MB segment after intracoronary nitroglycerin administration (200 μg). Maximal hyperemia was induced with intravenous adenosine triphosphate (ATP, 140 μg/kg·min), and FFR was calculated as the ratio of mean distal coronary pressure (Pd) to aortic pressure (Pa) during stable hyperemia. PCI was performed for FFR ≤ 0.80 and deferred otherwise. Care was taken to avoid wire contact with the vessel wall and to ensure proper alignment distal to the MB (23).

2.3 PCI procedures

All PCI procedures were performed by experienced interventional cardiologists, with procedural plans tailored according to the operator's clinical judgment. IVUS was routinely utilized to characterize lesion morphology and to identify appropriate stent landing zones. When indicated, lesion preparation techniques were employed prior to stent deployment. Stents were implanted in reference segments where the plaque burden, as assessed by IVUS, was less than 50%. In situations where the MB segment was located distal to the target lesion, stent deployment within the bridged segment was generally avoided. Nonetheless, when significant dissection extended into the MB or when severe atherosclerotic involvement was present directly adjacent to the MB, stent extension into the bridged region was permitted at the operator's discretion. Technical success was defined by achieving restored antegrade coronary flow corresponding to Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade 3, along with a residual diameter stenosis of less than 30% in the treated segment. Total procedural duration was measured from the time of vascular access to the final withdrawal of the guiding catheter.

2.4 Periprocedural pharmacotherapy

All patients were administered standard dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), comprising aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) for at least seven days prior to the procedure. In preparation for the intervention, a loading dose was given 24 h in advance, consisting of aspirin (300 mg) and either clopidogrel (300 mg) or ticagrelor (180 mg), selected according to the treating physician's clinical judgment. Post-PCI, DAPT was continued for 12 months using aspirin (100 mg/day) in combination with clopidogrel (75 mg/day). Additional pharmacologic therapies—including statins, beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and nitrates—were prescribed individually based on each patient's clinical status and comorbid conditions.

2.5 IVUS imaging and analysis

As per institutional standard practice, IVUS imaging was systematically performed in all patients undergoing PCI (FFR ≤ 0.80 group) prior to stent implantation. No patient in the PCI group was excluded for not receiving IVUS. After guidewire placement, 100–200 μg of intracoronary nitroglycerin was administered to reduce vasospasm and improve image quality. The IVUS catheter was advanced distal to the target lesion and withdrawn proximally under fluoroscopic guidance at a controlled rate of 0.5–1.0 mm/s. All imaging sequences were recorded and archived for offline analysis. Quantitative measurements were conducted using QIvus® software (Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands) by two independent observers blinded to clinical data. Discrepancies were resolved by a senior adjudicator. Standardized acquisition and analysis protocols were applied throughout to ensure consistency. MB was defined as an intramyocardial segment of an epicardial artery showing systolic compression and encasement by echolucent muscular tissue on IVUS (24). The following parameters were assessed: minimum lumen area (MLA) at maximal narrowing, plaque burden at the MLA site, maximum MB thickness, total MB length, and diastolic vessel restriction, calculated as (1−diastolic vessel area/interpolated reference area) (18). IVUS guidance was used to ensure stent placement within segments with <50% plaque burden. Stent expansion was assessed as the ratio of the minimum stent area (MSA) to the average reference lumen area of adjacent segments. Stent extension into the MB segment was generally avoided unless clinically necessary, such as in cases of extensive proximal dissection. All IVUS measurements were obtained during presumed end-diastole to ensure consistency. Final anatomical assessments, incorporating both IVUS and angiographic data, were independently reviewed by two experienced interventional cardiologists (X.W. and H.H.) blinded to treatment allocation. Inter- and intra-observer agreement was high, with κ values of 0.89 and 0.92, respectively.

2.6 Follow-up and clinical outcomes

Patients underwent scheduled follow-up evaluations at 1, 6, and 12 months post-discharge, and annually thereafter. Follow-up information was collected through a combination of outpatient clinic visits, electronic hospital records, and structured telephone interviews. When necessary, additional verification was conducted via communication with referring physicians or by consulting national mortality registries. The primary study endpoint was the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as a composite outcome including cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (MI), clinically indicated target lesion revascularization (TLR), rehospitalization for recurrent anginal symptoms, definite or probable in-stent thrombosis (IST), acute heart failure, or life-threatening arrhythmias. These events were classified according to standardized criteria established by the Academic Research Consortium (25).

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to evaluate the normality of distribution for continuous variables. Data with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using independent-samples t-tests. For variables not following a normal distribution, data were expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR) and analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, with comparisons made using Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, depending on data characteristics. To determine independent predictors of MACE, variables that reached statistical significance in univariate analysis were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model employing backward stepwise elimination. Time-to-event outcomes were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, and differences between groups were evaluated by the log-rank test. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Additionally, among patients with FFR ≤ 0.80 who underwent PCI, a predefined subgroup analysis was performed to compare clinical outcomes between those who received stent extension into the MB segment and those who did not.

3 Results

A total of 238 patients were enrolled, with 96 in the FFR > 0.80 group and 142 in the FFR ≤ 0.80 group. Baseline demographic and clinical features were generally well balanced between the two cohorts. No significant differences were observed in age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors (including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia), or background pharmacological treatment (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variables | All (n = 238) | FFR > 0.80 (n = 96) | FFR ≤ 0.80 (n = 142) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.06 (60.45, 66.02) | 62.94 (60.41, 65.82) | 63.32 (60.47, 66.14) | 0.487 |

| Male, n % | 143 (60.1%) | 57 (59.4%) | 86 (60.6%) | 0.961 |

| Prior hypertension, n % | 114 (47.9%) | 44 (45.8%) | 70 (49.3%) | 0.694 |

| Prior hyperlipidemia, n % | 89 (37.4%) | 33 (34.4%) | 56 (39.4%) | 0.512 |

| Prior diabetes mellitus, n % | 66 (27.7%) | 30 (31.2%) | 36 (25.4%) | 0.395 |

| Prior stroke, n % | 13 (5.5%) | 6 (6.2%) | 7 (4.9%) | 0.881 |

| Smoking, n % | 114 (47.9%) | 48 (50.0%) | 66 (46.5%) | 0.688 |

| Chronic kidney diseaseaa, n % | 12 (5.0%) | 7 (7.3%) | 5 (3.5%) | 0.316 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n % | 30 (12.6%) | 13 (13.5%) | 17 (12.0%) | 0.873 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n % | 68 (28.6%) | 24 (25.0%) | 44 (31.0%) | 0.391 |

| Prior PCI, n % | 29 (12.2%) | 10 (10.4%) | 19 (13.4%) | 0.628 |

| Laboratory biomarkers | ||||

| Platelet count, 109 /L | 249.80 (233.41, 264.70) | 248.08 (231.41, 264.82) | 251.41 (234.41, 264.70) | 0.626 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.88 (1.68, 2.02) | 1.83 (1.67, 1.99) | 1.91 (1.71, 2.04) | 0.113 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.32 (5.16, 5.53) | 5.31 (5.19, 5.52) | 5.33 (5.16, 5.54) | 0.857 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.26 (1.16, 1.37) | 1.28 (1.18, 1.36) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.38) | 0.742 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 3.36 (3.21, 3.50) | 3.36 (3.15, 3.50) | 3.35 (3.24, 3.50) | 0.428 |

| Lp(a), mg/L | 197.80 (171.03, 224.06) | 197.68 (164.96, 217.10) | 199.03 (173.23, 226.02) | 0.301 |

| AST, U/L | 113.30 (98.57, 130.96) | 113.30 (101.54, 129.07) | 113.27 (97.54, 133.45) | 0.922 |

| ALT, U/L | 48.84 (40.33, 56.08) | 48.66 (39.58, 54.40) | 49.71 (40.75, 56.89) | 0.507 |

| TBIL, umol/L | 16.48 (15.11, 17.83) | 16.48 (14.57, 17.44) | 16.48 (15.31, 18.03) | 0.073 |

| Uric acid, umol/L | 475.31 (438.44, 517.02) | 471.94 (437.88, 513.18) | 475.86 (442.11, 518.33) | 0.358 |

| Scr, umol/L | 88.92 (85.62, 92.83) | 89.81 (86.18, 94.26) | 88.72 (85.44, 92.69) | 0.212 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.732 m2 | 99.56 (92.65, 108.89) | 99.15 (90.79, 106.66) | 99.71 (93.39, 110.28) | 0.366 |

| Pharmacologic therapy | ||||

| DAPT, n % | 238 (100.0%) | 96 (100.0%) | 142 (100.0%) | 1.000 |

| Statins, n % | 221 (92.9%) | 92 (95.8%) | 129 (90.8%) | 0.226 |

| ACEI or ARB, n % | 140 (58.8%) | 59 (61.5%) | 81 (57.0%) | 0.585 |

| Beta-blockers, n % | 194 (81.5%) | 74 (77.1%) | 120 (84.5%) | 0.307 |

| Aldosterone antagonists, n % | 40 (16.8%) | 15 (15.6%) | 25 (17.6%) | 0.822 |

| Nitrates, n % | 9 (3.8%) | 3 (3.1%) | 6 (4.2%) | 0.927 |

| Calcium channel blockers, n % | 29 (12.2%) | 10 (10.4%) | 19 (13.4%) | 0.628 |

Baseline characteristics.

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

FFR, fractional flow reserve; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TBIL, total bilirubin; Scr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics were also comparable across groups. Parameters such as proximal stenosis severity, MB segment length, degree of systolic compression, and the distance from the proximal stenosis to the MB did not differ significantly. As expected, the FFR ≤ 0.80 group exhibited a significantly lower baseline FFR value (0.71 ± 0.03 vs. 0.88 ± 0.03, P < 0.001). Within this group, 43 patients (30.3%) underwent stent extension into the MB segment (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | All (n = 238) | FFR > 0.80 (n = 96) | FFR ≤ 0.80 (n = 142) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-PCI FFR | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Proximal stenosis severity, % | 66.19 ± 6.16 | 65.81 ± 6.41 | 66.45 ± 5.95 | 0.357 |

| Lesion length >20 mm, n % | 68 (28.6%) | 26 (27.1%) | 42 (29.6%) | 0.785 |

| Lesion length, mm | 36.24 ± 3.60 | 35.92 ± 3.66 | 36.45 ± 3.54 | 0.298 |

| MB length, mm | 11.04 ± 4.04 | 10.56 ± 4.83 | 11.36 ± 3.35 | 0.170 |

| Systolic compression severity of the bridged segment, % | 63.95 ± 7.08 | 63.28 ± 7.07 | 64.41 ± 7.02 | 0.175 |

| Distance from proximal stenosis to the MB, mm | 14.75 ± 3.05 | 15.20 ± 3.18 | 14.44 ± 2.90 | 0.090 |

| Calcification, n % | 23 (9.7%) | 10 (10.4%) | 13 (9.2%) | 0.920 |

| Calcium length, mm | 10.04 ± 0.54 | 10.06 ± 0.53 | 10.02 ± 0.55 | 0.769 |

| Lesion bend, n % | 25 (10.5%) | 9 (9.4%) | 16 (11.3%) | 0.801 |

| Post-PCI in-segmenta | ||||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | – | – | 3.22 ± 0.53 | – |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | – | – | 2.58 ± 0.19 | – |

| Diameter stenosis, % | – | – | 22.23 ± 3.30 | – |

| Post-PCI distal vessel | ||||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | – | – | 1.95 ± 1.03 | – |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | – | – | 1.17 ± 0.31 | – |

| Diameter stenosis, % | – | – | 29.29 ± 3.73 | – |

| Procedural findings | ||||

| Total stent length, mm | – | – | 39.30 ± 5.93 | – |

| Post-PCI FFR | – | – | 0.89 ± 0.04 | – |

| Stent extension into MB | – | – | 43 (30.3) | – |

| Maximum device diameter, mm | – | – | 3.28 ± 2.46 | – |

| Maximum balloon inflation pressure, atm | – | – | 18.58 ± 3.00 | – |

| Procedure time, min | – | – | 45.99 ± 6.94 | – |

| Radiation exposure dose, Gy | – | – | 1.97 ± 0.30 | – |

| Contrast media volume, ml | – | – | 271.11 ± 15.43 | – |

Angiographic and procedural findings.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

FFR, fractional flow reserve; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MB, myocardial bridging.

In-segment includes stent and 5 mm proximal and distal reference from each stent edge.

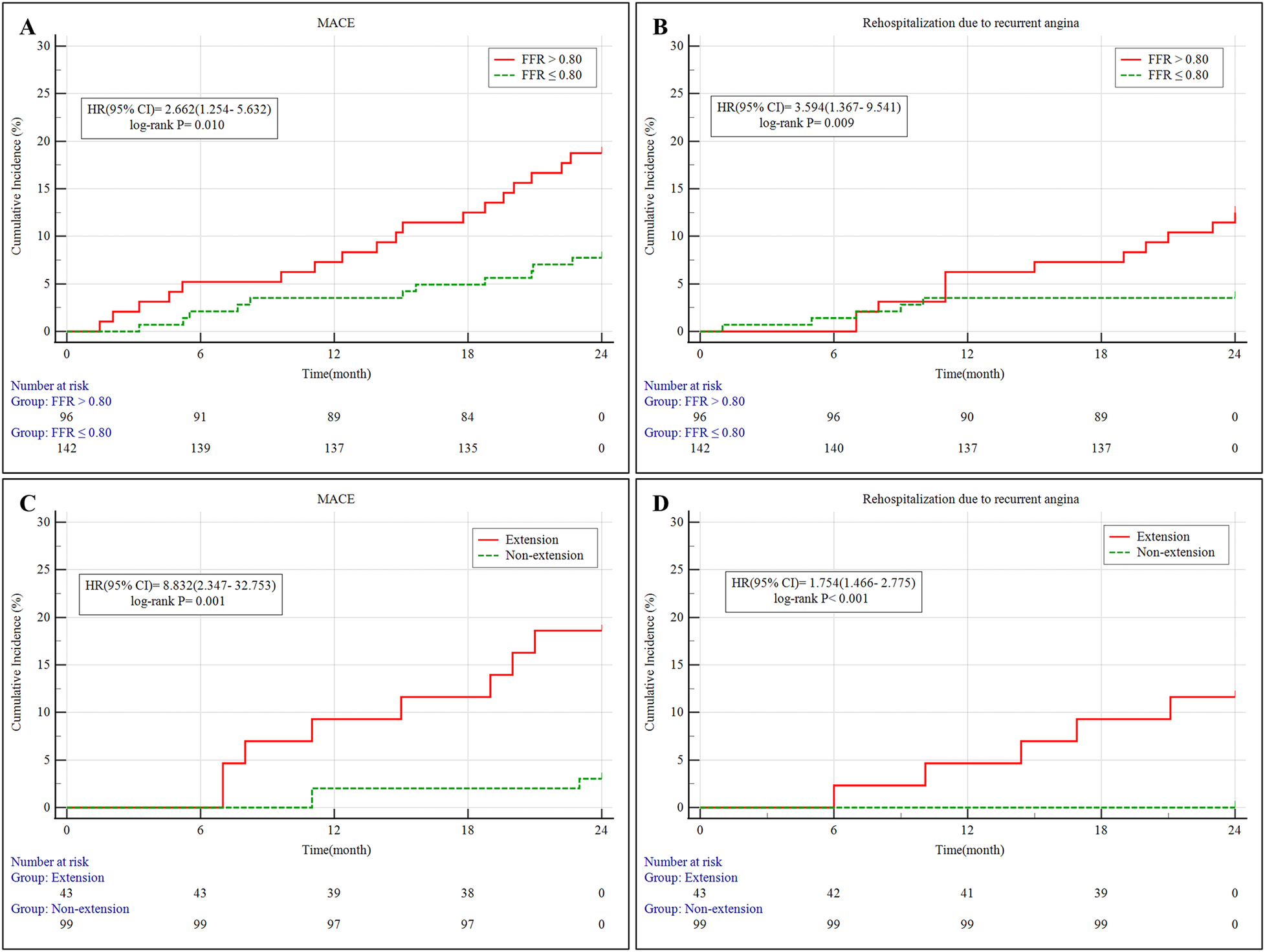

At two-year follow-up, the FFR > 0.80 group experienced a higher rate of MACE (18.8% vs. 7.7%, P = 0.019), primarily driven by increased rehospitalization for recurrent angina (12.5% vs. 3.5%, P = 0.017), compared to those in the FFR ≤ 0.80 group. Other individual endpoints, including cardiac mortality, MI, TLR, acute heart failure, and malignant arrhythmias, showed no statistically significant differences (Table 3; Figures 2A,B).

Table 3

| Variables | All (n = 238) | FFR > 0.80 (n = 96) | FFR ≤ 0.80 (n = 142) | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE, n % | 29 (12.2%) | 18 (18.8%) | 11 (7.7%) | 2.742 | 1.233–6.121 | 0.019 |

| Cardiac death, n % | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (2.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | 3.154 | 0.268–13.557 | 0.731 |

| Target vessel MI, n % | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (3.1%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2.256 | 0.370–9.773 | 0.656 |

| Clinically driven TLR, n % | 8 (3.4%) | 6 (6.2%) | 2 (1.4%) | 4.661 | 0.921–8.630 | 0.095 |

| Rehospitalization due to recurrent angina, n % | 17 (7.1%) | 12 (12.5%) | 5 (3.5%) | 3.914 | 1.331–11.504 | 0.017 |

| In-stent thrombosis, n % | – | – | 1 (0.7%) | – | – | – |

| Acute heart failure, n % | 6 (2.5%) | 4 (4.2%) | 2 (1.4%) | 3.043 | 0.546–16.956 | 0.362 |

| Malignant arrhythmias, n % | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (2.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2.532 | 0.268–5.175 | 0.731 |

2-year clinical outcomes.

Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

FFR, fractional flow reserve; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularizatio; OR, odds ratios; CI, confidence interval;.

Figure 2

(A,B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of MACE and rehospitalization due to recurrent angina in patients stratified by FFR for 2 years. (C,D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of MACE and rehospitalization due to recurrent angina in the PCI subgroup (FFR ≤ 0.80) stratified by stent extension into MB for 2 years. MB, myocardial bridging; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; FFR, fractional flow reserve;.

Multivariate Cox regression identified PCI as an independent protective factor against MACE [hazard ratio [HR] = 0.526, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.247–0.969, P = 0.034]. Conversely, stent extension into the MB was independently associated with a higher risk of MACE (HR = 2.632, 95% CI: 1.778–3.674, P = 0.016). Other variables, such as diabetes status, degree of proximal stenosis, and MB compression severity, were not independently predictive (Table 4).

Table 4

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.185 | 0.903–1.553 | 0.227 | |||

| Male sex | 1.154 | 0.702–1.725 | 0.656 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.252 | 0.825–1.899 | 0.315 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.652 | 1.054–2.586 | 0.033 | 1.383 | 0.848–2.156 | 0.121 |

| Proximal stenosis severity (%) | 1.034 | 1.014–1.126 | 0.026 | 1.122 | 0.623–2.012 | 0.704 |

| Systolic compression of MB (%) | 1.043 | 1.015–1.074 | 0.013 | 1.175 | 0.543–2.435 | 0.701 |

| MB length (mm) | 1.023 | 0.948–1.078 | 0.115 | |||

| FFR ≤ 0.80 | 1.645 | 0.328–2.649 | 0.853 | |||

| PCI performed | 0.484 | 0.244–0.953 | 0.035 | 0.526 | 0.247–0.969 | 0.034 |

| Stent extension into MB | 1.483 | 1.401–2.174 | 0.043 | 2.632 | 1.778–3.674 | 0.016 |

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses showing independent predictors of MACE.

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; HR, hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; MB, myocardial bridging; FFR, fractional flow reserve.

Within the PCI-treated subgroup (n = 142), patients were further divided based on whether the stent extended into the MB. The MB-stent group comprised 43 patients (30.3%), while 99 patients (69.7%) received stents without crossing the MB. Baseline variables were generally similar between the two groups (Table 5). Although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward fewer male patients (48.8% vs. 65.7%, P = 0.059), and a lower prevalence of hypertension (37.2% vs. 54.5%, P = 0.057) and hyperlipidemia (27.9% vs. 44.4%, P = 0.063) in the MB-stent group.

Table 5

| Variables | All (n = 142) | Stent extension into MB group (n = 43) | Stent non-extension group (n = 99) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.03 (61.30, 64.73) | 62.82 (61.24, 64.53) | 63.10 (61.38, 64.85) | 0.732 |

| Male, n % | 86 (60.6%) | 21 (48.8%) | 65 (65.7%) | 0.059 |

| Prior hypertension, n % | 70 (49.3%) | 16 (37.2%) | 54 (54.5%) | 0.057 |

| Prior hyperlipidemia, n % | 56 (39.4%) | 12 (27.9%) | 44 (44.4%) | 0.063 |

| Prior diabetes mellitus, n % | 36 (25.4%) | 7 (16.3%) | 29 (29.3%) | 0.101 |

| Prior stroke, n % | 7 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (7.1%) | 0.073 |

| Smoking, n % | 66 (46.5%) | 15 (34.9%) | 51 (51.5%) | 0.067 |

| Chronic kidney diseaseaa, n % | 5 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (5.1%) | 0.133 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n % | 17 (12.0%) | 2 (4.7%) | 15 (15.2%) | 0.076 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n % | 44 (31.0%) | 9 (20.9%) | 35 (35.4%) | 0.087 |

| Prior PCI, n % | 19 (13.4%) | 3 (7.0%) | 16 (16.2%) | 0.139 |

| Laboratory biomarkers | ||||

| Platelet count, 109/L | 251.41 (234.41, 264.70) | 252.27 (241.54, 262.68) | 250.45 (234.06, 266.26) | 0.911 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.91 (1.71, 2.04) | 1.93 (1.76, 2.08) | 1.87 (1.71, 2.01) | 0.257 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.33 (5.16, 5.54) | 5.37 (5.16, 5.48) | 5.33 (5.15, 5.56) | 0.657 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.26 (1.16, 1.38) | 1.29 (1.18, 1.38) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.38) | 0.374 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 3.35 (3.24, 3.50) | 3.34 (3.22, 3.46) | 3.38 (3.25, 3.50) | 0.505 |

| Lp(a), mg/L | 199.03 (173.23, 226.02) | 200.82 (186.67, 230.84) | 197.42 (169.72, 225.09) | 0.152 |

| AST, U/L | 113.27 (97.54, 133.45) | 117.85 (103.13, 130.67) | 112.77 (96.76, 134.95) | 0.715 |

| ALT, U/L | 49.71 (40.75, 56.89) | 50.06 (40.44, 55.06) | 49.43 (41.52, 56.96) | 0.834 |

| TBIL, umol/L | 16.48 (15.31, 18.03) | 16.44 (15.36, 18.03) | 16.50 (15.28, 18.03) | 0.862 |

| Uric acid, umol/L | 475.86 (442.11, 518.33) | 473.81 (437.92, 516.80) | 477.21 (445.24, 519.76) | 0.622 |

| Scr, umol/L | 88.72 (85.44, 92.69) | 88.74 (86.42, 93.79) | 88.71 (84.05, 92.36) | 0.282 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.732 m2 | 99.71 (93.39, 110.28) | 99.40 (93.33, 107.80) | 100.11 (93.57, 111.10) | 0.569 |

| Pharmacologic therapy | ||||

| DAPT, n % | 142 (100.0%) | 43 (100.0%) | 99 (100.0%) | 1.000 |

| Statins, n % | 129 (90.8%) | 41 (95.3%) | 88 (88.9%) | 0.223 |

| ACEI or ARB, n % | 81 (57.0%) | 24 (55.8%) | 57 (57.6%) | 0.848 |

| Beta-blockers, n % | 120 (84.5%) | 40 (93.0%) | 80 (80.8%) | 0.103 |

| Aldosterone antagonists, n % | 25 (17.6%) | 8 (18.6%) | 17 (17.2%) | 0.840 |

| Nitrates, n % | 6 (4.2%) | 2 (4.7%) | 4 (4.0%) | 0.919 |

| Calcium channel blockers, n % | 19 (13.4%) | 6 (14.0%) | 13 (13.1%) | 0.898 |

Baseline characteristics in the PCI subgroup (FFR ≤ 0.80) stratified by stent extension into MB.

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

FFR, fractional flow reserve; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TBIL, total bilirubin; Scr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MB, myocardial bridging.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation.

As presented in Table 6, patients receiving MB stenting had longer lesion lengths (37.35 ± 3.24 mm vs. 36.06 ± 3.58 mm, P = 0.038), longer MB segments (12.26 ± 3.37 mm vs. 10.96 ± 3.27 mm, P = 0.036), and more severe systolic compression (67.71 ± 5.60% vs. 62.90 ± 7.01%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the distance from the proximal lesion to the MB was significantly shorter in the MB-stent group (13.63 ± 2.88 mm vs. 14.79 ± 2.84 mm, P = 0.030).

Table 6

| Variables | All (n = 142) | Stent extension into MB group (n = 43) | Stent non-extension group (n = 99) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-PCI FFR | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | 0.057 |

| Proximal stenosis severity, % | 66.45 ± 5.95 | 66.87 ± 5.88 | 66.27 ± 5.97 | 0.587 |

| Lesion length >20 mm, n % | 42 (29.6%) | 20 (46.5%) | 22 (22.2%) | 0.006 |

| Lesion length, mm | 36.45 ± 3.54 | 37.35 ± 3.24 | 36.06 ± 3.58 | 0.038 |

| MB length, mm | 11.36 ± 3.35 | 12.26 ± 3.37 | 10.96 ± 3.27 | 0.036 |

| Systolic compression severity of the bridged segment, % | 64.41 ± 7.02 | 67.71 ± 5.60 | 62.90 ± 7.01 | <0.001 |

| Distance from proximal stenosis to the MB, mm | 14.44 ± 2.90 | 13.63 ± 2.88 | 14.79 ± 2.84 | 0.030 |

| Calcification, n % | 13 (9.2%) | 3 (7.0%) | 10 (10.1%) | 0.782 |

| Calcium length, mm | 10.02 ± 0.55 | 9.94 ± 0.48 | 10.05 ± 0.58 | 0.252 |

| Lesion bend, n % | 16 (11.3%) | 5 (11.6%) | 11 (11.1%) | 1.000 |

| Post-PCI in-segmenta | ||||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 3.22 ± 0.53 | 3.26 ± 0.59 | 3.20 ± 0.50 | 0.542 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 2.58 ± 0.19 | 2.58 ± 0.19 | 2.58 ± 0.19 | 0.933 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 22.23 ± 3.30 | 22.29 ± 2.95 | 22.20 ± 3.46 | 0.885 |

| Post-PCI distal vessel | ||||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 1.95 ± 1.03 | 2.03 ± 1.14 | 1.91 ± 0.98 | 0.542 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 1.17 ± 0.31 | 1.18 ± 0.32 | 1.17 ± 0.30 | 0.933 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 29.29 ± 3.73 | 29.35 ± 3.34 | 29.26 ± 3.90 | 0.875 |

| Procedural findings | ||||

| Total stent length, mm | 39.30 ± 5.93 | 40.95 ± 6.25 | 38.58 ± 5.66 | 0.027 |

| Post-PCI FFR | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.107 |

| Maximum device diameter, mm | 3.28 ± 2.46 | 3.01 ± 2.55 | 3.39 ± 2.42 | 0.395 |

| Maximum balloon inflation pressure, atm | 18.58 ± 3.00 | 18.21 ± 3.24 | 18.74 ± 2.89 | 0.340 |

| Procedure time, min | 45.99 ± 6.94 | 46.53 ± 7.72 | 45.76 ± 6.60 | 0.542 |

| Radiation exposure dose, Gy | 1.97 ± 0.30 | 1.98 ± 0.31 | 1.97 ± 0.29 | 0.933 |

| Contrast media volume, ml | 271.11 ± 15.43 | 271.39 ± 13.80 | 270.98 ± 16.15 | 0.885 |

Angiographic and procedural findings in the PCI subgroup (FFR ≤ 0.80) stratified by stent extension into MB.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

FFR, fractional flow reserve; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MB, myocardial bridging.

In-segment includes stent and 5 mm proximal and distal reference from each stent edge.

Post-PCI IVUS assessments (Table 7) revealed a higher incidence of dissection (44.2% vs. 19.2%, P = 0.003) and dissection extension into the MB (34.9% vs. 9.1%, P < 0.001) in the MB-stent group. Other IVUS parameters, including plaque burden, calcification, and stent expansion, were similar between groups.

Table 7

| Variables | All (n = 142) | Stent extension into MB group (n = 43) | Stent non-extension group (n = 99) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion length, mm | 38.74 ± 5.65 | 39.75 ± 6.25 | 38.30 ± 5.35 | 0.160 |

| Maximum plaque burden, % | 83.78 ± 5.24 | 83.84 ± 5.43 | 83.76 ± 5.18 | 0.933 |

| Calcification in lesion, n % | 33 (23.2%) | 11 (25.6%) | 22 (22.2%) | 0.826 |

| Maximum arc of calcium,° | 123.58 ± 20.74 | 123.97 ± 18.55 | 123.42 ± 21.72 | 0.885 |

| Dissection, n % | 38 (26.8%) | 19 (44.2%) | 19 (19.2%) | 0.003 |

| Dissection extended into an MB, n % | 24 (16.9%) | 15 (34.9%) | 9 (9.1%) | <0.001 |

| Reference minimum lumen area, mm2 | 3.68 ± 1.35 | 3.82 ± 1.50 | 3.62 ± 1.29 | 0.417 |

| Reference maximum plaque burden, % | 58.05 ± 3.37 | 58.48 ± 3.30 | 57.86 ± 3.39 | 0.313 |

| MB segment | ||||

| Distance from LAD ostium to MB, mm | 34.15 ± 6.91 | 34.77 ± 7.27 | 33.88 ± 6.78 | 0.485 |

| Total MB length, mm | 10.83 ± 2.43 | 12.21 ± 2.40 | 10.23 ± 2.19 | <0.001 |

| Maximum thickness of MB, mm | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.433 |

| Diastolic vessel area at max compression site, mm2 | 4.34 ± 0.61 | 4.32 ± 0.53 | 4.35 ± 0.64 | 0.792 |

| Diastolic vessel restriction, % | 19.57 ± 4.29 | 18.60 ± 4.48 | 19.99 ± 4.17 | 0.077 |

| Minimum lumen area, mm2 | 2.41 ± 0.60 | 2.39 ± 0.67 | 2.41 ± 0.57 | 0.828 |

| Plaque burden at minimum lumen area site, % | 41.15 ± 4.05 | 41.44 ± 4.04 | 41.02 ± 4.07 | 0.569 |

| Postprocedure findings | ||||

| MSA, mm2 | 5.43 ± 3.22 | 5.21 ± 2.57 | 5.53 ± 3.48 | 0.588 |

| Stent expansion, % | 70.36 ± 3.24 | 70.60 ± 2.71 | 70.26 ± 3.45 | 0.565 |

| Rate of MSA in the MB, when stented, n % | 71 (50.0%) | 21 (48.8%) | 50 (50.5%) | 0.856 |

Intravascular ultrasound findings in the PCI subgroup (FFR ≤ 0.80) stratified by stent extension into MB.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

MB, myocardial bridging; MSA, minimum stent area; LAD, left anterior descending artery; FFR, fractional flow reserve; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention;.

During the 2-year follow-up, MACE occurred significantly more often in patients with MB stent extension (18.6% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.001), mainly due to a markedly higher rate of angina-related rehospitalization (11.6% vs. 0%, P < 0.001) (Table 8; Figures 2C,D). No significant differences were observed in cardiac death, target vessel MI, or TLR between the subgroups.

Table 8

| Variables | All (n = 142) | Stent extension into MB group (n = 43) | Stent non-extension group (n = 99) | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE, n % | 11 (7.7%) | 8 (18.6%) | 3 (3.0%) | 1.717 | 1.105–4.240 | 0.001 |

| Cardiac death, n % | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.877 | 0.686–2.122 | 0.508 |

| Target vessel MI, n % | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.944 | 0.839–1.061 | 0.541 |

| Clinically driven TLR, n % | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1.000 | 0.684–1.463 | 0.541 |

| Rehospitalization due to recurrent angina, n % | 5 (3.5%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.026 | 1.004–2.049 | <0.001 |

| In-stent thrombosis, n % | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.981 | 0.925–1.040 | 0.127 |

| Acute heart failure, n % | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0.996 | 0.976–1.016 | 0.347 |

| Malignant arrhythmias, n % | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.019 | 0.982–1.056 | 0.127 |

2-year clinical outcomes in the PCI subgroup (FFR ≤ 0.80) stratified by stent extension into MB.

Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage).

FFR, fractional flow reserve; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularizatio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MB, myocardial bridging; OR, odds ratios; CI, confidence interval;.

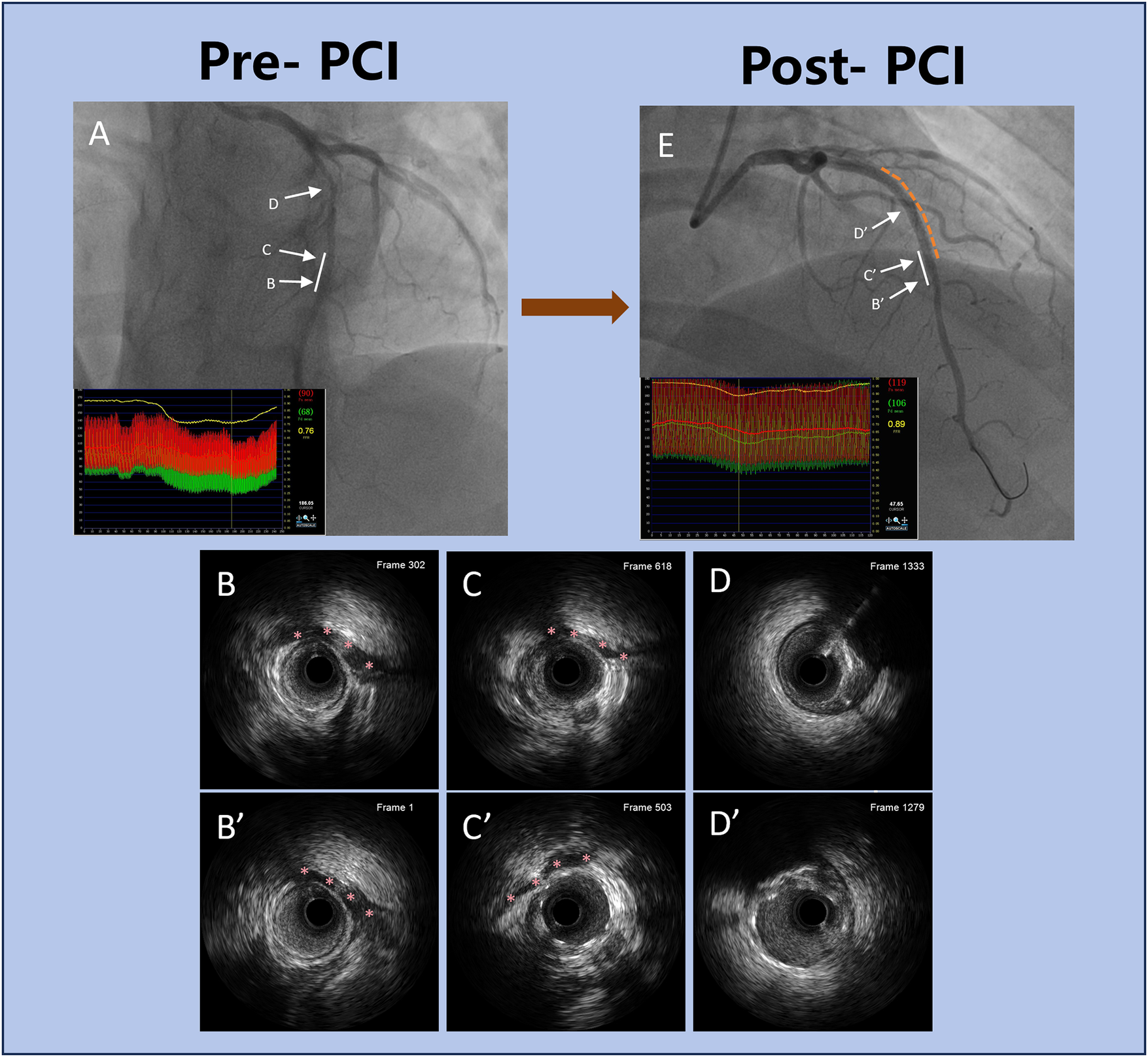

Multivariate logistic regression (Table 9) identified two independent predictors of stent extension into the MB segment: a shorter distance from the proximal lesion to the MB [odds ratio (OR) = 1.774, 95% CI: 1.542–2.145, P = 0.019], and the presence of dissection extending into the MB (OR = 2.435, 95% CI: 2.045–2.745, P = 0.041). A representative case of proximal LAD stenosis involving the MB, evaluated by CAG, IVUS, and FFR before and after PCI, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 9

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Lesion length >20 mm | 1.753 | 1.363–2.431 | 0.028 | 0.862 | 0.653–1.057 | 0.792 |

| Lesion length, mm | 0.853 | 0.535–1.066 | 0.827 | |||

| MB length, mm | 0.942 | 0.537–1.164 | 0.516 | |||

| Systolic compression severity of the bridged segment, % | 0.923 | 0.743–1.263 | 0.452 | |||

| Distance from proximal stenosis to the MB, mm | 1.413 | 1.137–1.652 | 0.018 | 1.774 | 1.542–2.145 | 0.019 |

| Total stent length, mm | 0.833 | 0.424–1.262 | 0.746 | |||

| Dissection | 0.862 | 0.653–1.074 | 0.792 | |||

| Dissection extended into an MB | 1.963 | 1.725–2.356 | 0.036 | 2.435 | 2.045–2.745 | 0.041 |

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses showing independent predictors of stent extension into MB in the PCI subgroup (FFR ≤ 0.80).

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; OR, odds ratios; CI, confidence interval; MB, myocardial bridging; FFR, fractional flow reserve; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention;.

Figure 3

Representative clinical case of PCI in a patient with proximal LAD stenosis and MB. (A) Pre-PCI coronary angiography showing moderate proximal LAD stenosis adjacent to a MB. The white solid line indicates the MB segment. The co-registered FFR tracing reveals a nadir value of 0.76 distal to the MB, indicating functionally significant ischemia. (B–D) Corresponding pre-PCI IVUS images at levels (B–D). Red asterisks in (B,C) mark the MB segment identified on IVUS, showing systolic compression and plaque burden. (E) Post-PCI coronary angiography after DES deployment. The white solid line again marks the MB segment, and the yellow dashed line outlines the stented portion of the vessel. FFR improved to 0.89, confirming successful revascularization with improved coronary physiology. (B’–D’) Post-PCI IVUS images at corresponding levels B’–D’. Red asterisks in B’ and C’ indicate the MB segment, showing adequate stent expansion and apposition outside the bridged area, with no evidence of malapposition or dissection. This case highlights the integration of anatomical imaging (angiography, IVUS) and FFR to guide optimal PCI strategy, particularly in lesions involving MB. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; LAD, left anterior descending artery; MB, myocardial bridging; FFR, fractional flow reserve; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; DES, drug-eluting stent.

4 Discussion

This study demonstrated that an FFR-guided revascularization strategy was associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in patients presenting with moderate MB and concomitant proximal intermediate coronary stenosis. Notably, patients with FFR ≤ 0.80 who underwent PCI experienced significantly lower rates of MACE and rehospitalizations for recurrent angina compared to those managed conservatively with medical therapy alone. Multivariate regression confirmed PCI as an independent protective factor against MACE, while stent extension into the MB segment was identified as an independent risk factor. Within the PCI-treated subgroup, patients who received stents extending into the MB region showed a markedly higher incidence of both MACE and angina-related readmissions compared to those whose stents did not involve the bridged segment. Further analysis revealed two independent predictors of elevated MACE risk in this subgroup: a shorter anatomical distance between the proximal stenosis and the MB, and the presence of dissection extending into the bridged segment.

4.1 FFR-guided management of moderate myocardial bridging with proximal stenosis

4.1.1 Role of FFR in the functional assessment of MB-related stenosis

Anatomical stenosis does not always reflect the presence or severity of functional ischemia, particularly in dynamic lesions such as MB. This mismatch between anatomical narrowing and physiological impact complicates visual assessment and highlights the necessity of objective functional evaluation. In line with this, the 2018 ESC guidelines recommend FFR as a Class I, Level A tool for assessing intermediate coronary stenoses (5). While FFR is well established in evaluating coronary physiology, its use in MB presents notable challenges. MB causes systolic compression that predominantly impairs diastolic perfusion, yet conventional FFR—derived from mean pressure ratios over the entire cardiac cycle during hyperemia—may fail to capture this diastolic dysfunction. In particular, systolic compression can distort the average gradient without fully reflecting the true ischemic burden. Recent studies suggest that diastolic-specific indices, such as diastolic FFR (dFFR) obtained under dobutamine stress, may more accurately detect MB-related ischemia, with diagnostic thresholds typically set at ≤0.76 (26, 27).

Our findings support this physiological limitation. Patients with FFR > 0.80 who did not undergo PCI demonstrated a higher numerical rate of MACE than those revascularized with FFR ≤ 0.80. This counterintuitive pattern may reflect residual ischemia due to diastolic flow restriction not captured by traditional FFR, especially in cases with coexisting proximal LAD atherosclerosis. Thus, exclusive reliance on conventional FFR in MB-associated disease may lead to undertreatment. These observations underscore the importance of integrating anatomic imaging and phase-specific functional assessment. Tools such as IVUS for structural evaluation, and dFFR or instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) for capturing diastolic flow impairment, can provide a more comprehensive assessment. A tailored, anatomy-function integrated strategy may enhance diagnostic precision, improve therapeutic targeting, and ultimately lead to better outcomes in patients with proximal LAD stenosis complicated by MB.

4.1.2 Reconsidering the safety of deferring PCI in FFR > 0.80

PCI deferral in patients with FFR > 0.80 is generally considered safe and aligns with current international guidelines (5). However, in our cohort, patients managed conservatively based on this threshold demonstrated a higher numerical incidence of MACE and angina-related rehospitalizations compared to those who underwent PCI with FFR ≤ 0.80. This paradox challenges the sufficiency of FFR as a standalone tool in guiding therapy for this subset.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms may explain this discrepancy. First, MB introduces dynamic coronary flow alterations via phasic systolic compression and retrograde flow, which can impair diastolic perfusion. Traditional FFR, as a cycle-averaged metric, may overlook these transient disturbances (28, 29). Second, atherosclerotic plaques commonly develop proximal to the MB segment and may remain hemodynamically silent on FFR but still pose a risk for progression or rupture (9, 28). Third, factors such as sympathetic activation or elevated heart rate can further reduce diastolic time, exacerbating ischemia—particularly when proximal lesions are left untreated (28, 29).

Given these complexities, reliance solely on preserved FFR (>0.80) may underestimate true ischemic burden in MB-associated lesions. A more nuanced diagnostic approach is warranted—one that incorporates anatomical imaging with IVUS and phase-specific physiologic assessment using indices such as iFR or dFFR. This is especially important in patients with persistent symptoms or inconclusive clinical findings.

4.1.3 Implications of PCI in FFR ≤ 0.80 group

In contrast, revascularization conferred clear clinical benefit in patients with functionally significant lesions, as indicated by an FFR ≤ 0.80. These patients experienced significantly lower rates of MACE and angina-related rehospitalizations. Multivariate analysis confirmed PCI as an independent protective factor, reinforcing its therapeutic value in addressing hemodynamically relevant proximal lesions—even when complicated by MB.

Our results further suggest that when the FFR falls below 0.80, the combined ischemic burden from proximal atherosclerotic narrowing and MB-induced compression becomes clinically significant and warrants intervention. In this context, DES implantation can restore antegrade flow, stabilize vulnerable plaque, and improve long-term outcomes. Crucially, these data also emphasize the importance of procedural precision in MB-associated lesions. While a reduced FFR supports revascularization, operators must account for the contractile behavior of MB segments. Careful delineation of stent landing zones is essential to avoid complications arising from stent placement within dynamically compressed arterial regions.

4.2 PCI in proximal LAD stenosis involving myocardial bridging

4.2.1 Risks associated with stent extension into MB segment

Our analysis demonstrated that patients receiving stent implantation extending into the MB segment exhibited a significantly higher incidence of MACE, with recurrent angina being the most prominent contributor. This observation is consistent with earlier studies reporting the mechanical and biological challenges of deploying stents within segments subject to dynamic systolic compression (30–33). The systolic narrowing characteristic of MB generates oscillatory shear forces and repetitive endothelial injury, which are known to trigger neointimal proliferation and increase the risk of in-stent restenosis (32, 33). Additionally, sustained extrinsic compression may impair endothelial healing, stimulate smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation, and compromise long-term stent integrity (33). Notably, in our cohort, several patients with no angiographic evidence of restenosis continued to experience exertional angina during follow-up. This suggests that residual dynamic compression within the MB segment may persist even after technically successful stent deployment, leading to ongoing ischemic symptoms despite the absence of fixed luminal narrowing (33).

4.2.2 Anatomical predictors of poor outcomes after MB stenting

Subgroup analysis identified two critical anatomical factors associated with adverse outcomes in patients who received stents extending into the MB segment. First, a shorter spatial interval between the proximal stenosis and the bridged segment significantly increased the risk of MACE. This is likely attributable to the technical challenge of achieving precise stent deployment without encroaching on the MB region (9). Prior studies have indicated that when this distance is less than 10 mm, the likelihood of unintended stent protrusion into the MB segment rises substantially, thereby elevating the risk of mechanical complications (34). Second, the unique anatomical environment of MB—where the coronary artery is enveloped by contracting myocardium—renders it particularly susceptible to poor outcomes if a dissection extends into this region. Ongoing systolic compression within the bridged segment can intensify local shear forces and impede the natural resolution of dissections, potentially resulting in stent malapposition, thrombotic events, or in-stent restenosis (27, 32, 33). These findings highlight the essential role of IVUS in procedural planning. Beyond detecting otherwise unrecognized dissections, IVUS is instrumental in accurately delineating optimal proximal and distal landing zones, thereby reducing the likelihood of stent-related complications and enhancing procedural safety (32, 33).

4.2.3 Recommendations for stenting strategy in LAD-MB lesions

In light of the elevated risk of complications associated with stent implantation within MB segments, accumulating evidence favors a “no-stent zone” approach—deliberately avoiding stent deployment in dynamically compressed coronary segments (32, 33). Abdalwahab et al. proposed that extending the stent at least 3–5 mm beyond both the proximal and distal margins of the MB segment may reduce mechanical strain on the stent structure and enhance clinical outcomes (32). This technique minimizes the adverse effects of recurrent systolic compression, which can otherwise cause cyclic mechanical injury, impair endothelial healing, and promote neointimal hyperplasia—mechanisms central to restenosis and late stent failure (27, 33). In their study, the application of second-generation DES under IVUS guidance, combined with deliberate avoidance of the bridged segment, resulted in an absence of stent fractures or restenosis during long-term follow-up. In contrast, findings from our cohort revealed that direct stenting within the MB—without such anatomical consideration—was associated with significantly higher rates of MACE.

To improve procedural outcomes in this anatomically complex subset, a dual-modality strategy is advisable. Integration of IVUS for structural assessment with advanced physiologic evaluation—such as dFFR or dobutamine-stress FFR—facilitates both accurate lesion characterization and ischemia confirmation (9, 32). This comprehensive pre-intervention framework supports optimal landing zone selection and reduces the likelihood of inadvertently covering high-risk bridged segments. A systematic planning protocol that incorporates IVUS-defined MB morphology and dFFR-derived ischemic mapping may allow for tailored stent placement strategies, minimize procedural hazards, and align interventions with individual patient vascular physiology (9, 32).

4.3 Limitations

This study has several limitations. It was a retrospective, single-center study conducted in a Chinese population, which may introduce selection bias and significantly limit the generalizability of the findings to other ethnicities, regions, or healthcare systems. The sample size—especially in the MB-stent subgroup—was relatively small, potentially underpowering the detection of rare events. Although IVUS was routinely used, advanced functional indices such as such as dFFR, hyperemic iFR, or dobutamine stress testing were not consistently applied or available. This may have led to an underestimation of ischemia in borderline or discordant FFR cases, particularly in the context of MB, where dynamic systolic compression can impair diastolic flow that is not captured by conventional cycle-averaged FFR. This may have led to an underestimation of ischemia in borderline or discordant FFR cases, particularly in the context of MB, where dynamic systolic compression can impair diastolic flow that is not captured by conventional cycle-averaged FFR. Additionally, only mid-LAD myocardial bridges were evaluated, which may not reflect other anatomical variants such as proximal or distal MBs, further limiting the extrapolation of our findings to the broader MB population. Moreover, certain anatomical parameters such as MB depth were not routinely quantified from IVUS due to the absence of standardized definitions and technical challenges in reliable measurement. This limitation may have restricted our ability to assess additional structural predictors of clinical outcomes. Furthermore, no formal correction for multiple testing was applied in subgroup analyses, as only a single predefined stratification (stent extension into MB) was conducted. However, the results should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating, and the potential risk of type I error is acknowledged. In addition, further subgroup analyses comparing deferred patients with and without stent extension into the MB were not performed due to sample size constraints and the exploratory nature of the study. Finally, the follow-up period, while adequate for intermediate outcomes, may not capture late complications such as very late stent thrombosis or vessel remodeling. A randomized controlled trial (although challenging in this clinical setting) would be useful to further validate these findings.

5 Conclusion

In patients with moderate MB and proximal LAD stenosis, an FFR-guided strategy combined with IVUS optimization was associated with improved clinical outcomes. PCI was beneficial when FFR ≤ 0.80, but stent extension into the MB segment led to significantly worse prognosis, particularly when anatomical risk factors were present. Interestingly, patients with FFR > 0.80 managed conservatively experienced a higher incidence of MACE, suggesting that conventional FFR may underestimate ischemia in the context of MB. This likely reflects the limitations of cycle-averaged FFR in detecting diastolic flow impairment caused by dynamic systolic compression. These results underscore the importance of integrating functional assessment with precise anatomical imaging to guide intervention. Avoiding stent coverage of dynamically compressed segments and tailoring landing zones with IVUS may reduce complications. A multimodal, physiology-anatomy–based approach is therefore essential in this complex lesion subset, where reliance on FFR alone may be insufficient.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Xiangtan Central Hospital (The Affiliated Hospital of Hunan University). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

XW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. MW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HaH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HeH: Data curation, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Open Fund of the National Innovation Center for High Performance Medical Devices (Grant No. NMED2025KF-02-011).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Lee JM Koo BK Shin ES Nam CW Doh JH Hwang D et al Clinical implications of three-vessel fractional flow reserve measurement in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39(11):945–51. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx458

2.

Lee JM Kim H Hong D Hwang D Zhang J Hu X et al Clinical outcomes of deferred lesions by IVUS versus FFR-guided treatment decision. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2023) 16(12):e013308. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.123.013308

3.

Xaplanteris P Fournier S Pijls NHJ Fearon WF Barbato E Tonino PAL et al Five-year outcomes with PCI guided by fractional flow reserve. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379(3):250–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803538

4.

De Bruyne B Pijls NH Kalesan B Barbato E Tonino PA Piroth Z et al Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367(11):991–1001. 10.1056/NEJMoa1205361

5.

Neumann FJ Sousa-Uva M Ahlsson A Alfonso F Banning AP Benedetto U et al 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40(2):87–165. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

6.

Mintz GS Guagliumi G . Intravascular imaging in coronary artery disease. Lancet (London, England). (2017) 390(10096):793–809. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31957-8

7.

Buccheri S Franchina G Romano S Puglisi S Venuti G D'Arrigo P et al Clinical outcomes following intravascular imaging-guided versus coronary angiography-guided percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of 31 studies and 17,882 patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2017) 10(24):2488–98. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.051

8.

Lee JM Choi KH Song YB Lee JY Lee SJ Lee SY et al Intravascular imaging-guided or angiography-guided complex PCI. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388(18):1668–79. 10.1056/NEJMoa2216607

9.

Sternheim D Power DA Samtani R Kini A Fuster V Sharma S . Myocardial bridging: diagnosis, functional assessment, and management: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 78(22):2196–212. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.859

10.

Berry JF von Mering GO Schmalfuss C Hill JA Kerensky RA . Systolic compression of the left anterior descending coronary artery: a case series, review of the literature, and therapeutic options including stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2002) 56(1):58–63. 10.1002/ccd.10151

11.

Kodama K Morioka N Hara Y Shigematsu Y Hamada M Hiwada K . Coronary vasospasm at the site of myocardial bridge–report of two cases. Angiology. (1998) 49(8):659–63. 10.1177/000331979804900812

12.

Ural E Bildirici U Celikyurt U Kilic T Sahin T Acar E et al Long-term prognosis of non-interventionally followed patients with isolated myocardial bridge and severe systolic compression of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Clin Cardiol. (2009) 32(8):454–7. 10.1002/clc.20570

13.

Feld H Guadanino V Hollander G Greengart A Lichstein E Shani J . Exercise-induced ventricular tachycardia in association with a myocardial bridge. Chest. (1991) 99(5):1295–6. 10.1378/chest.99.5.1295

14.

Marchionni N Chechi T Falai M Margheri M Fumagalli S . Myocardial stunning associated with a myocardial bridge. Int J Cardiol. (2002) 82(1):65–7. 10.1016/S0167-5273(01)00580-0

15.

Tio RA Van Gelder IC Boonstra PW Crijns HJ . Myocardial bridging in a survivor of sudden cardiac near-death: role of intracoronary doppler flow measurements and angiography during dobutamine stress in the clinical evaluation. Heart (British Cardiac Society). (1997) 77(3):280–2. 10.1136/hrt.77.3.280

16.

Lee CH Kim U Park JS Kim YJ . Impact of myocardial bridging on the long-term clinical outcomes of patients with left anterior descending coronary artery disease treated with a drug-eluting stent. Heart Lung Circ. (2014) 23(8):758–63. 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.021

17.

Bockeria LA Sukhanov SG Orekhova EN Shatakhyan MP Korotayev DA Sternik L . Results of coronary artery bypass grafting in myocardial bridging of left anterior descending artery. J Card Surg. (2013) 28(3):218–21. 10.1111/jocs.12101

18.

Hashikata T Honda Y Wang H Pargaonkar VS Nishi T Hollak MB et al Impact of diastolic vessel restriction on quality of life in symptomatic myocardial bridging patients treated with surgical unroofing: preoperative assessments with intravascular ultrasound and coronary computed tomography angiography. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(10):e011062. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011062

19.

Anderson JL Adams CD Antman EM Bridges CR Califf RM Casey DE Jr et al ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (writing committee to revise the 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction) developed in collaboration with the American college of emergency physicians, the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, and the society of thoracic surgeons endorsed by the American association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation and the society for academic emergency medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2007) 50(7):e1–e157. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013

20.

Amplatz K Anderson R . Angiographic appearance of myocardial bridging of the coronary artery. Invest Radiol. (1968) 3(3):213–5. 10.1097/00004424-196805000-00009

21.

Nakanishi R Rajani R Ishikawa Y Ishii T Berman DS . Myocardial bridging on coronary CTA: an innocent bystander or a culprit in myocardial infarction?J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. (2012) 6(1):3–13. 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.10.015

22.

Fihn SD Gardin JM Abrams J Berra K Blankenship JC Dallas AP et al 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American college of physicians, American association for thoracic surgery, preventive cardiovascular nurses association, society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, and society of thoracic surgeons. Circulation. (2012) 126(25):e354–471. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318277d6a0

23.

Qi X Fan G Zhu D Ma W Yang C . Comprehensive assessment of coronary fractional flow reserve. Arch Med Sci. (2015) 11(3):483–93. 10.5114/aoms.2015.52351

24.

Tsujita K Maehara A Mintz GS Doi H Kubo T Castellanos C et al Comparison of angiographic and intravascular ultrasonic detection of myocardial bridging of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Am J Cardiol. (2008) 102(12):1608–13. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.054

25.

Cutlip DE Windecker S Mehran R Boam A Cohen DJ van Es GA et al Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. (2007) 115(17):2344–51. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313

26.

Pargaonkar VS Kimura T Kameda R Tanaka S Yamada R Schwartz JG et al Invasive assessment of myocardial bridging in patients with angina and no obstructive coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. (2021) 16(13):1070–8. 10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00779

27.

Tarantini G Barioli A Nai Fovino L Fraccaro C Masiero G Iliceto S et al Unmasking myocardial bridge-related ischemia by intracoronary functional evaluation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11(6):e006247. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.006247

28.

Darabont RO Vișoiu IS Magda SL Stoicescu C Vintilă VD Udroiu C et al Implications of myocardial bridge on coronary atherosclerosis and survival. Diagnostics (Basel). (2022) 12(4):948. 10.3390/diagnostics12040948

29.

Ge J Jeremias A Rupp A Abels M Baumgart D Liu F et al New signs characteristic of myocardial bridging demonstrated by intracoronary ultrasound and doppler. Eur Heart J. (1999) 20(23):1707–16. 10.1053/euhj.1999.1661

30.

Kunamneni PB Rajdev S Krishnan P Moreno PR Kim MC Sharma SK et al Outcome of intracoronary stenting after failed maximal medical therapy in patients with symptomatic myocardial bridge. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2008) 71(2):185–90. 10.1002/ccd.21358

31.

Matta A Canitrot R Nader V Blanco S Campelo-Parada F Bouisset F et al Left anterior descending myocardial bridge: angiographic prevalence and its association to atherosclerosis. Indian Heart J. (2021) 73(4):429–33. 10.1016/j.ihj.2021.01.018

32.

Abdalwahab A Ghobrial M Farag M Salim T Stone GW Egred M . Percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting for the treatment of myocardial muscle bridges: a consecutive case series. J Invasive Cardiol. (2023) 35:E169–e78. 10.25270/jic/22.00342

33.

Hao Z Xinwei J Ahmed Z Huanjun P Zhanqi W Yanfei W et al The outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention for significant atherosclerotic lesions in segment proximal to myocardial bridge at left anterior descending coronary artery. Int Heart J. (2018) 59(3):467–73. 10.1536/ihj.17-179

34.

Alegria JR Herrmann J Holmes DR Jr Lerman A Rihal CS . Myocardial bridging. Eur Heart J. (2005) 26(12):1159–68. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi203

Summary

Keywords

myocardial bridging, fractional flow reserve, intravascular ultrasound, percutaneous coronary intervention, left anterior descending

Citation

Wu X, Wu M, Huang H, Liu Z, Huang H and Wang L (2026) Clinical outcomes of FFR and IVUS-guided PCI in patients with myocardial bridging and proximal LAD stenosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1648221. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1648221

Received

16 June 2025

Revised

10 November 2025

Accepted

09 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Panagiotis Xaplanteris, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Reviewed by

Andreas Mitsis, Nicosia General Hospital, Cyprus

Niya Mileva, Aleksandrovska University Hospital, Bulgaria

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wu, Wu, Huang, Liu, Huang and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Haobo Huang hearthhb@yeah.net Lei Wang heartwl@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.