Abstract

Introduction:

Arrhythmias in non-human animals offer insights into human electrophysiology, yet physicians may be unaware of their occurrence and significance. This paper presents selected examples of arrhythmias in dogs, horses, and birds— as an invitation to human cardiologists to explore how animal models can illuminate mechanisms, genetics, and therapeutic approaches relevant to human electrophysiology.

Methods:

Leading veterinary cardiologists compiled overviews of common arrhythmias in dogs, cats, horses and birds. Genetic predisposition, natural history, therapeutic approaches, and epidemiology were compared across these species and humans, highlighting translational opportunities.

Results:

Common human arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, ventricular tachycardia, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy occur naturally in dogs, cats, horses, and birds. Cross-species differences in disease expression provide unique insights into mechanisms of arrhythmia vulnerability and resistance. Dogs develop similar inherited arrhythmogenic diseases but with distinct phenotypes. Horses experience atrial fibrillation without thromboembolic complications, revealing potential protective pathways. They also demonstrate extreme exercise-induced arrhythmia susceptibility, isolating exercise as an arrhythmogenic trigger. Avian species exhibit remarkable adaptation to cardiac loading conditions that would be pathological in mammals. These comparative observations across species highlight novel mechanisms underlying both susceptibility and resistance to arrhythmias and conduction disorders, offering unexplored therapeutic targets for human patients.

Discussion:

Cross-species knowledge offers direct translational value for human electrophysiology—from genetic markers in Labrador Retrievers with supraventricular tachycardia to cardiac loading paradigms in broiler chickens. Breaking down disciplinary barriers through shared research initiatives and integrated training represents an essential, underutilized strategy for advancing arrhythmia diagnosis, treatment, and prevention in human patients.

1 Introduction

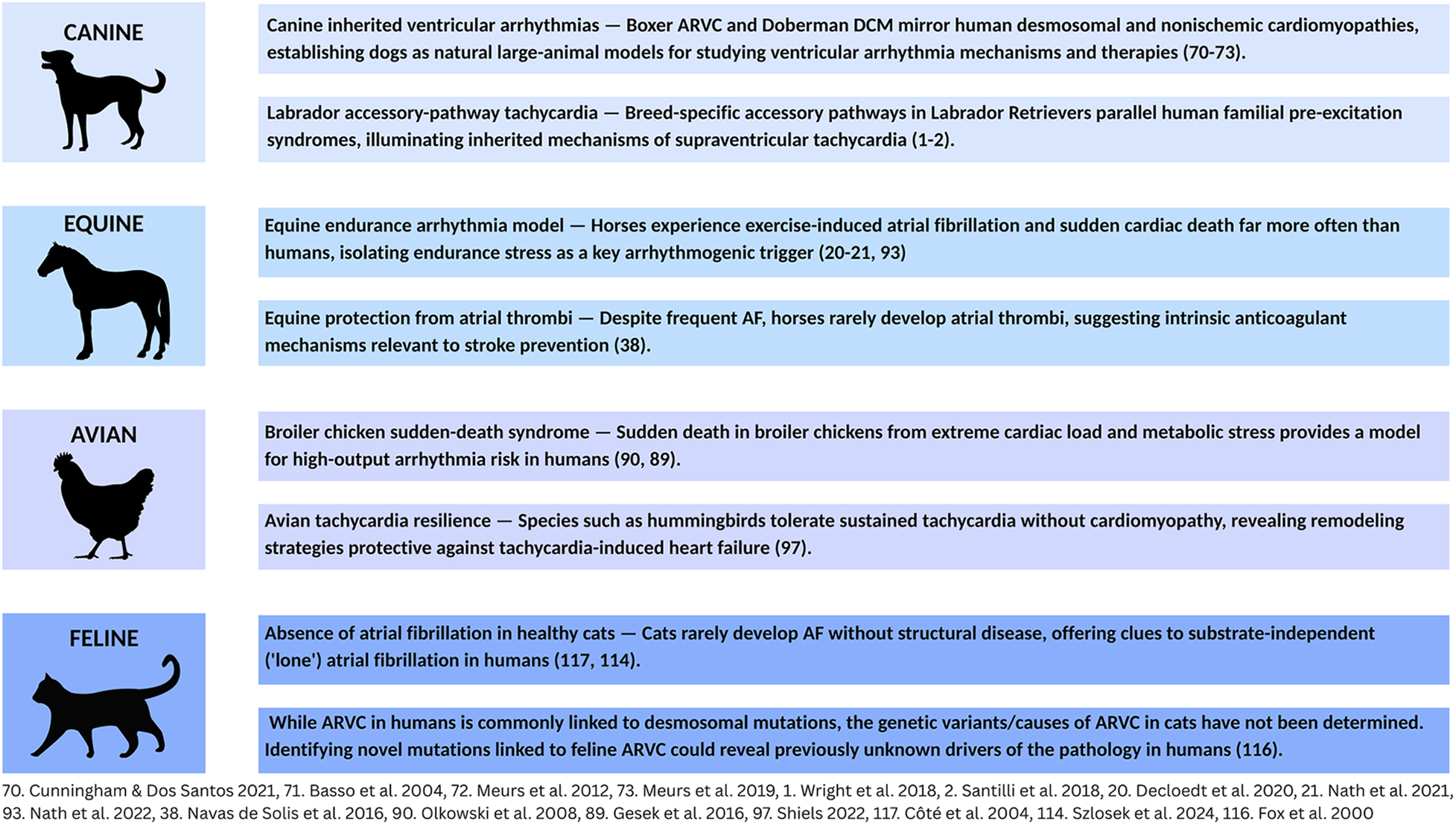

Many human electrophysiologic disorders also occur in other species. Veterinary cardiologists have extensive experience diagnosing, managing, and preventing these pathologies. Their insights can strengthen our understanding of human arrhythmias. Unfortunately, human cardiovascular training rarely includes exposure to these veterinary challenges. This paper seeks to bridge this gap by presenting a collection of clinically significant arrhythmias in dogs, horses, and birds along with human translational insights emerging from this comparative knowledge (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Arrhythmias in animals: a source of translational insights for human EP. Common clinical arrhythmias in dogs, horses, birds, and cats offer unique insights into challenges in human electrophysiology.

Most scientific literature on animal arrhythmias focuses on taxa under human care and oversight, although arrhythmia and conduction abnormalities exist across all vertebrate taxa. Much of the veterinary literature is focused on companion animals with breed-specific risks for electrophysiologic disorders, equine athletes, particularly Standardbred and Thoroughbred horses and agricultural birds (1–3).

2 Atrial fibrillation

2.1 AF in dogs

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common canine arrhythmia, diagnosed in 6.3–10.5% of dogs presenting with clinical heart disease and representing approximately one third of all pathologic arrhythmias (4, 5). Genetic factors and breed type play significant roles in susceptibility to AF (6). In Irish Wolfhounds, for example, AF incidence may exceed 10% while likelihood of AF in Miniature Poodles is as low as.04% (7, 8). Breed and size are linked, a factor influencing the nearly 6-fold increased risk of developing AF in large dogs (>20 kg) vs. smaller individuals (9). Atrial enlargement, left ventricular dimension and body weight are major risk factors associated with risk of developing AF (10–12).

In dogs, AF develops most often in association with structural heart disease (SHD). Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and advanced myxomatous mitral valve degeneration (MMVD) are the two most common underlying structural abnormalities linked to AF (13, 14). MMVD more commonly affects smaller dogs and DCM most commonly occurs in larger dogs. Primary AF (AF in the absence of SHD) is generally diagnosed in giant breed dogs. Since multiple reentrant circuits are needed to maintain AF, it may be that larger breeds are at increased risk compared to smaller breeds because they have sufficiently large atrial surfaces to support these electrophysiologic mechanisms (9). Age and sex may be predictors of AF in dogs; however, the strength of these associations has recently been challenged (12, 15). Severe MMVD commonly affects small to medium size dogs; however, even within the MMVD population, larger breed dogs with advanced disease and concurrent congestive heart failure (CHF) are especially at risk of developing AF (14, 16). Dogs with accessory atrioventricular pathways (AVPs) are predisposed to AF. In some cases, ablation of the AVP can eliminate or markedly reduce AF (1, 17). The goal of pharmacological treatment of AF in dogs is not cardioversion to sinus rhythm but maintenance of a ventricular rate no more than 120–125 bpm (18, 19).

2.2 AF in horses

In horses, AF prevalence ranges from 0.3% to 2.5% (20), reaching 4.9% in thoroughbreds (21). In equine athletes, AF is the most common arrhythmia causing poor performance (22), with racehorses and other athletes at higher risk due to intense cardiac demands (23). Large breed horses are more susceptible because greater atrial size may provide the critical mass needed to sustain arrhythmia (20, 24), which may explain its rarity in smaller horses, ponies, and foals (25).

SHD, including congenital abnormalities and valvular insufficiencies, can predispose horses to AF (26, 27), however, most cases occur in apparently normal hearts. This condition may be triggered by vigorous exercise, electrolyte imbalance, or genetic predisposition. Sustained AF (48 h or more is considered persistent) may be treated with pharmacological or electrical cardioversion. Success depends on specific characteristics of the horse and the AF itself (28). Many horses can be successfully converted to normal rhythm, though some remain in permanent AF.

2.3 AF in birds

The translational insights for human AF from avian species is less straightforward than in dogs and horses. A significant difference is that unlike mammals, birds have a single pulmonary vein entering the left atrium. They may therefore lack the complex, arrhythmogenic pulmonary venous anatomy that often serves as the origin of AF in humans and other mammals (29).

2.4 Comparison of AF to humans

In both humans and dogs, AF is strongly linked to underlying SHD such as left atrial enlargement (10–12, 30). Larger overall body size also appears to increase risk in humans and dogs (11, 12). While age is a strong predictor of AF in humans, a similar association in dogs is not definitively established (11, 12, 15, 31). The natural history of AF in dogs and humans also differs with respect to thrombogenicity. A major risk associated with AF in humans is left atrial thrombosis and thromboembolic events (32, 33). By contrast, AF in dogs, even with left atrial enlargement, is rarely not associated with thrombosis or embolic events (34–36). Differences in atrial remodeling between the species with AF may underlie this variation between species (37).

A similar “resistance” to left atrial thrombus with AF is also found in equine patients. In horses, even longstanding AF does not appear to increase the risk of left atrial thrombus or clinical embolic events (38). Equine athletes also provide valuable comparative insights into AF. In both humans and horses, endurance and high-intensity athletes have a higher incidence of the arrhythmia. This points to a shared, atrial stress mechanism during strenuous exercise that may underlie AF initiation. A genetic component is present in both, and breed-linked AF in horses offers insights into specific genetic pathways relevant to human AF (39, 40). Approach to treatment is similar between the species, including the use of both pharmacological or electrical cardioversion when warranted (28).

3 Supraventricular tachycardia

3.1 SVT in dogs

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) secondary to accessory pathways (APs) has been identified in at least 37 dog breeds. Males account for about two-thirds of all cases (1, 2). Labrador Retrievers are especially vulnerable, comprising nearly half of North American and over a third of European dogs with confirmed APs, suggesting a strong genetic risk (1, 2). While breed predispositions exist for APs, none have been identified for focal atrial tachycardias (FATs) (41). Canine APs at electrophysiologic study (EPS) have unique features, with about 93% of canine APs located on the tricuspid annulus - a significant difference to humans, where they are most often on the mitral annulus (1, 2, 41). FATs, by contrast, originate from a single point in the atria (42).

Definitive diagnosis of SVT in dogs requires EPS under general anesthesia, making some types of SVT harder to detect (43). Once diagnosed, radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA), a procedure that uses heat to destroy the abnormal electrical tissue, is a common and effective treatment (1).

3.2 SVT in horses

Atrial tachycardia (AT) is the most common SVT in horses. One common mechanism is a macroreentrant circuit near the myocardial sleeves of the caudal vena cava (44), although FATs may also originate from a single atrial focus. Although “AT” is often used as a general term encompassing both focal and reentrant atrial tachycardias, it is important to distinguish these from other types of SVT such as atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) (45). Most cases are diagnosed in sport or performance horses undergoing cardiac evaluation. Recent advances, such as three-dimensional electro-anatomical mapping, have allowed precise localization of arrhythmia electrical activity. A consequence has been successful treatment of macroreentrant AT and AVPs (46–48). RFCA can eliminate the abnormal tissue and holds promise as a definitive therapy, despite the horse's large size and thick atrial walls (10–20 mm in the left atrium) (47).

3.3 SVT in birds

SVT has been diagnosed in birds in a variety of clinical contexts (49–51). Abnormal heart development have been documented to lead to the persistence of APs in a chick embryo model (52). Infection with avian influenza virus has been linked to AT in chickens and supraventricular premature complexes in other species (49). Arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy is also diagnosed in birds; clinical presentation includes left ventricular enlargement and poor cardiac function (51).

3.4 Comparison of SVT to humans

In both humans and dogs, APs and reentrant circuits are common mechanisms linked to SVT (53–56). Differences can be found in the location of the AP; in dogs 93% occur along the tricuspid annulus (1, 2, 41), while in humans 50%–60% are along the mitral annulus. Ventricular preexcitation linked to Wolff-Parkinson-White in humans is significantly less common in dogs (57). Genetics plays a central role in vulnerability. Specific breeds are at elevated risk. For example, Labrador Retrievers comprise up to 46% of dogs (North American study) with confirmed APs (1). This parallels the central role of genetics in human SVTs; ion channel gene variants are commonly implicated in our species (58).

Both human and equine athletes who participate in intense exercise may develop changes known as “athlete's heart” (59, 60). Athletes of both species are at increased risk of SVT; however, the specific causes and the anatomical locations of the arrhythmias differ significantly between the two species. In human athletes, SVT often arises from an AP (like in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome) or a reentrant circuit within the AV node (AVNRT), usually located in the left atrium (61). Sympathetic activation and higher heart rates enhance accessory conduction and facilitate reentry. In contrast, SVT in horses is more frequently associated with macroreentrant circuits (44), commonly involving the caudal vena cava where myocardial sleeves can become a site for arrhythmogenesis, creating a reentrant circuit. This AT mechanism is rarely documented in humans.

In both humans and birds, sustained SVT may lead to cardiomyocyte damage and arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy where a persistent tachycardia weakens the heart muscle over time (52). While APs are a common cause of SVT in humans, the persistence of these pathways in birds is linked to normal developmental processes (49, 52, 61, 62). Viral infection has been linked to SVT in avian species, but is not a typical cause in humans (49).

4 Ventricular tachycardia

4.1 VT in dogs

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) in dogs is often due to inherited heart diseases (63–68). Primary causes and characteristics of VT vary across vulnerable breeds including Boxers, Doberman Pinschers, and German Shepherds (GSD) (69).

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC) occurs most commonly in Boxers and English Bulldogs, though other breeds may also be affected (70). It is associated with sudden cardiac death and high cardiovascular morbidity (71) with average age (6 years) at presentation in Boxers (70). VT is a leading cause of sudden death in Doberman Pinschers with inherited DCM (72, 73). Females have increased risk of VT, while males tend to show earlier echocardiographic changes (74, 75). Rapid, sustained VT may require intravenous antiarrhythmic drugs or emergent direct current cardioversion. RFCA has been successfully performed in limited cases (76, 77).

A juvenile form of VT affects primarily GSDs although it occurs less commonly in Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Leonbergers and other breeds (63, 78, 79). Affected GSDs develop polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) around 12 weeks of age. Sudden cardiac death (SCD) may be the presenting event (63). These ventricular arrhythmias originate from triggered activity in the left ventricular Purkinje fibers (80) (not related to QT prolongation) and resolve spontaneously if the dog survives past two years of age (69). Treatment includes the use of antiarrhythmic drugs.

4.2 VT in horses

VAs are relatively common in horses, particularly athletes. Several studies report a high prevalence of premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) in clinically healthy, well-performing sport horses (81–83). VT is a serious condition and may cause poor performance, weakness, collapse or SCD (84). Horses at highest risk are athletes, racehorses and sport horses, experiencing significant cardiac stress while undergoing intense training (84). VT often emerges during or immediately following strenuous exercise, although it is sometimes detected at rest (3).

Although the cause of VT in horses often cannot be determined, it can be seen in association with underlying cardiac disorders such as myocarditis or systemic illness, colic and electrolyte imbalance (85). These conditions may promote electrical instability in the ventricles, predisposing the patient to VT. When life-threatening or symptomatic, treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs is required (85).

4.3 VT in birds

VAs are most frequently identified in avian species that maintain high basal heart rates and experience extreme cardiac loading due to a high metabolic rate due to rapid growth and/or acute physiological stress (86). Broilers have been bred to develop significant muscle mass (87). For broiler chickens in the rapid growth phase, high cardiac demand may lead to acute heart failure, with VAs and SCD being a risk in this setting (88, 89). VAs may emerge in the setting of systemic illnesses, exposure to toxins such as ingestion of heavy metals, or as a consequence of primary myocardial diseases such as myocarditis, or cardiomyopathy (62, 90).

4.4 Comparison of VT to humans

VT in dogs offers a naturally occurring large-animal model with significant translational value for human electrophysiology. Canine diseases closely mirror human conditions: Boxers develop VT associated with ARVC while Dobermans show VT linked to DCM, directly modeling human ARVC and DCM natural history and structural characteristics (69, 72, 73). Juvenile VT in GSDs exhibit a rare phenotype that may help electrophysiologists understand non-structural, triggered activity-based mechanisms in humans (91). This juvenile arrhythmia is a self-resolving, pause-dependent polymorphic VT (63), likely originating from left ventricular Purkinje fibers rather than scar tissue. This model is valuable for testing Purkinje-targeted interventions and improving risk stratification in genetically predisposed human populations.

Horses provide distinct comparative models for human VT and SCD. Cardiovascular causes are presumed when necropsy reveals no other explanation for equine sudden death (92). Unlike humans, horses rarely develop inherited cardiomyopathies – perhaps due to performance selection – yet, exercise-related SCD occurs 200 times more often in horses than humans (93). Racing's extreme physiologic demand creates challenging electrical environments: heart rate ranges from 28 bpm at rest to 240 bpm maximally, causing heterogeneous refractory dispersal post-exercise (3). While human VT usually arises from coronary disease and post-infarction scarring establishing re-entrant circuits, horses rarely develop coronary disease; their VT links to intense training, AF, systemic illness, or electrolyte disturbances (84, 85, 94, 95). Clinically, equine VT may manifest as poor performance, whereas humans most often experience syncope or cardiac arrest (84, 96).

Studying exercise-related arrhythmias in horses, including possible ion channelopathies, offers insights into repolarization instability elevating SCD risk in human athletes. Translational insights come from SCD in broiler chickens with load-associated pathology. Rapid growth creates high cardiac output demands and excessive cardiac afterload causing left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure (86). Avian SCD provides a natural model relevant for ventricular arrhythmias in high-load human cardiomyopathy (86). Birds may also model tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy resistance; hummingbirds sustain flight heart rates over 600 bpm without the cardiomyopathic changes seen in humans (97, 98). Examining avian susceptibility and resistance to arrhythmias may provide novel insights for preventing and managing cardiomyopathy and sudden death risk in vulnerable human populations.

5 Bradyarrhythmias

5.1 Bradyarrhythmias in dogs

The most common bradyarrhythmia in dogs is sinus arrhythmia, a non-pathological condition. Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) and high-grade atrioventricular (AV) blocks are the most clinically significant bradyarrhythmias (99, 100). These typically are NOT linked to underlying SHD, but are degenerative processes that have breed predilections. High vagal tone in resting or sedated dogs can accentuate the underlying EP abnormality (100, 101). Genetics affects susceptibility; Miniature Schnauzers and Cocker Spaniels more commonly present with SSS, while larger breeds are prone to AV block (102, 103). Symptomatic dogs present with lethargy, exercise intolerance, weakness, and syncope, with severe cases exhibiting sudden death (104, 105).

5.2 Bradyarrhythmias in horses

The most frequent bradyarrhythmias in horses are second-degree AV block and sinus bradycardia (106, 107). Second-degree AV block can be normal in well-conditioned athletes (108), but can also indicate myocarditis, electrolyte disturbances, or systemic illnesses (107, 109–112). In equine athletes, second-degree AV block is often asymptomatic (106) although advanced second-degree AV block may result in poor athletic performance, exercise intolerance, or collapse (107).

5.3 Comparison of bradyarrhythmias to humans

Dogs and humans have similar sinoatrial node structure and function. In both species, SSS is a common clinical indication for pacemaker treatment (113). Vulnerable breeds like Miniature Schnauzers offer a valuable model for understanding genetic bases and mechanisms of SSS. Developing therapies and pacemaker technology for smaller dogs may directly inform strategies for treating bradyarrhythmias for smaller adults and pediatric patients.

In equine athletes, bradycardias - especially second-degree AV block - may be normal, related to high vagal tone and cardiac efficiency (106, 108). Equine cardiac function across extreme heart rates can strengthen our ability to distinguish benign from pathological second-degree AV block and other bradyarrhythmias in athletic humans.

6 The feline model

Arrhythmias are less common in cats than dogs, typically occurring with systemic illness or underlying SHD in both species. The most frequent feline arrhythmias in a recent 9,000+ cat study were PVCs, though cats also presented with premature atrial contractions (PACs), SVT, AT, AF and AV blocks (114).

Ventricular arrhythmias emerge primarily in the setting of systemic illness or underlying SHD. In cats, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common serious cardiovascular disease (115). In HCM, myofibrillar disarray disrupts conduction tissue causing arrhythmias. ARVC occurs far less commonly than HCM; however, fatty and fibrous replacement of normal tissue, especially in the right ventricle, may be arrhythmogenic (116).

Unlike dogs, cats rarely develop arrhythmias in structurally normal hearts. Their smaller cardiac dimensions—especially a normal left atrial diameter of roughly 12 mm—limit the atrial surface area required to sustain reentrant arrhythmias such as AF (117). This anatomic constraint parallels observations in small and medium-sized dogs, which also do not develop AF without marked atrial dilation.

AF, when it does occur, is therefore almost always secondary to advanced SHD with significant atrial enlargement (117, 118). Importantly, atrial dilation in cats carries a high risk of left atrial thrombus formation and systemic thromboembolism, including aortic “saddle” thrombus, which can cause acute limb ischemia. This propensity contrasts sharply with the relative thromboresistance seen in dogs and horses with AF, and more closely resembles human AF pathophysiology.

The heightened feline thrombotic risk likely reflects species-specific differences in coagulation and endocardial response to stasis, as well as the compact geometry of the feline left atrium, which promotes blood stasis once dilation occurs (117; 38). Recognizing this distinction provides a valuable comparative model for understanding atrial thrombogenesis in humans.

6.1 Comparison of feline arrhythmias to humans

Cats, unlike humans, rarely develop AF without severe underlying heart disease (118). This may provide insight into lone AF vulnerability in humans. Moreover, while feline AF almost invariably leads to thromboembolism, human and feline AF share similar hemodynamic and prothrombotic mechanisms, making cats an important natural model for AF-associated stroke risk. Differences between human and feline ARVC and HCM—shared sarcomeric mutations in HCM but absent desmosomal mutations in feline ARVC—offer valuable insights for human patients (119, 120).

7 Conclusion

A comparative survey of arrhythmia across species reveals potential models for human electrophysiology. Examples with translational potential for humans include resistance to AF-associated thromboembolic events in horses and dogs, canine breed-specific arrhythmia predispositions, and a sudden death syndrome linked to acute heart failure in broiler chickens. In contrast, cats provide a unique natural model of thromboembolic vulnerability, highlighting how small atrial size and species-specific coagulation profiles can amplify embolic risk once AF develops—a finding that strengthens the translational value of feline cardiomyopathy research for human stroke prevention.

Statements

Author contributions

BN-H: Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. GV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. AD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. AG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. XC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. XC is supported, in part, by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Mentored Career Development Award [HL168147].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Basil Baccouche, Julia Cho, Meagan Martin, and Amelia Reynolds for their assistance in preparing the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. All of the paper's content is original as are its interpretations and conclusions, which are those of the authors. AI was used to streamline background research and editing tasks such as grammar and formatting.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AF, atrial fibrillation; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; MMVD, myxomatous mitral valve disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; AVPs, atrioventricular pathways; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; APs, accessory pathways; FATs, focal atrial tachycardias; MRATs, macroreentrant atrial tachycardias; EPS, electrophysiologic study; RFCA, radiofrequency catheter ablation; AT, atrial tachycardia; AVRT, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; VT, ventricular tachycardia; GSD, german shepherd dogs; ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; VAs, ventricular arrhythmias; SCD, sudden cardiac death; PVC, premature ventricular complexes; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; AV, atrioventricular; PACs, premature atrial contractions; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

References

1.

Wright KN Connor CE Irvin HI Knilans TK Weber D Kass PH . Atrioventricular accessory pathways in 89 dogs: clinical features and outcomes after radiofrequency catheter ablation. J Vet Intern Med. (2018) 32:1517–29. 10.1111/jvim.15248

2.

Santilli RA Mateos Pañero M Porteiro Vázquez DM Perini A Perego M . Radiofrequency catheter ablation of accessory pathways in the dog: the Italian experience (2008–2016). J Vet Cardiol. (2018) 20(5):384–97. 10.1016/j.jvc.2018.07.006

3.

Marr CM Bowen IM . Cardiology of the Horse. Edinburgh: Saunders (2010).

4.

Noszczyk-Nowak A Michalek M Kaluza E Cepiel A Paslawska U . Prevalence of arrhythmias in dogs examined between 2008 and 2014. J Vet Res. (2017) 61:103–10. 10.1515/jvetres-2017-0013

5.

Pedro B Fontes-Sousa AP Gelzer AR . Canine atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology, epidemiology, and classification. Vet J. (2020) 265:105548. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2020.105548

6.

Fousse SL Tyrrell WD Dentino ME Abrams FL Rosenthal SL Stern JA . Pedigree analysis of atrial fibrillation in Irish wolfhounds supports a high heritability with a dominant mode of inheritance. Canine Genet Epidemiol. (2019) 6:11. 10.1186/s40575-019-0079-y

7.

Westling J Westling W Pyle L . Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the dog. Int J Appl Res Vet Med. (2008) 6:151–4.

8.

Tyrrell WD Jr Abbott JA Rosenthal SL Dentino M Abrams F . Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic evaluation of north American Irish wolfhounds. J Vet Intern Med. (2020) 34(2):581–90. 10.1111/jvim.15709

9.

Borgarelli M Zini E D'Agnolo G Tarducci A Santillini RA Chiavegato D et al Comparison of primary mitral valve disease in German shepherd dogs and in small breeds. J Vet Cardiol. (2004) 6(2):27–34. 10.1016/S1760-2734(06)70055-8

10.

Guglielmini C Chetboul V Pietra M Pouchelon JL Capucci A Cipone M . Influence of left atrial enlargement and body weight on the development of atrial fibrillation: retrospective study on 205 dogs. Vet J. (2000) 160(3):235–41. 10.1053/tvjl.2000.0506

11.

Guglielmini C Goncalves Sousa M Baron Toaldo M Valente C Bentivoglio V Mazzoldi C et al Prevalence and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. (2020) 34(6):2223–31. 10.1111/jvim.15927

12.

Guglielmini C Valente C Romito G Mazzoldi C Baron Toaldo M Goncalves Sousa M et al Risk factors for atrial fibrillation in dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy. Front. Vet. Sci. (2023) 10:1183689. 10.3389/fvets.2023.1183689

13.

Martin MWS Stafford-Johnson MA Strehlau G King JN . Canine dilated cardiomyopathy: a retrospective study of prognostic findings in 367 clinical cases. J Small Anim Pract. (2010) 51:428–36. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00966.x

14.

Ward J Ware WA Viall A . Association between atrial fibrillation and right-sided manifestations of congestive heart failure in dogs with degenerative mitral valve disease or dilated cardiomyopathy. J Vet Cardiol. (2019) 21:18–27. 10.1016/j.jvc.2018.10.006

15.

Arcuri G Valente C Perini C Guglielmini C . Risk factors for atrial fibrillation in the dog: a systematic review. Vet. Sci. (2024) 11(1):47. 10.3390/vetsci11010047

16.

Jung SW Griffiths LG Kittleson MD . Atrial fibrillation as a prognostic indicator in medium to large-sized dogs with myxomatous mitral valvular degeneration and congestive heart failure. J Vet Intern Med. (2017) 30:51–7. 10.1111/jvim.13800

17.

Centurión OA Shimizu A Isimoto S Konoe A . Mechanisms for the genesis of atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: intrinsic atrial muscle vulnerability versus electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway. Europace. (2008) 10:292–302. 10.1093/europace/eun031

18.

Pedro B Mavropoulou A Oyama MA Linney C Neves J Dukes-McEwan J et al Optimal rate control in dogs with atrial fibrillation–ORCA study–multicenter prospective observational study: prognostic impact and predictors of rate control. J Vet Intern Med. (2023) 37(3):887–99. 10.1111/jvim.16666

19.

Pedro B Dukes-McEwan J Oyama MA Kraus MS Gelzer AR . Retrospective evaluation of the effect of heart rate on survival in dogs with atrial fibrillation. J Vet Intern Med. (2018) 32(1):86–92. 10.1111/jvim.14896

20.

Decloedt A Van Steenkiste G Vera L Buhl R van Loon G . Atrial fibrillation in horses part 1: pathophysiology. Vet J. (2020) 263:105521. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2020.105521

21.

Nath LC Elliott AD Weir J Curl P Rosanowski SM Franklin S . Incidence, recurrence, and outcome of postrace atrial fibrillation in thoroughbred horses. J Vet Intern Med. (2021) 35(2):1111–20. 10.1111/jvim.16063

22.

Reef VB Bonagura J Buhl R McGurrin MKJ Schwarzwald CC van Loon G et al Recommendations for management of equine athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Vet Intern Med. (2014) 28:749–61. 10.1111/jvim.12340

23.

Kjeldsen ST Nissen SD Buhl R Hopster-Iversen C . Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in horses: pathophysiology, diagnostics and clinical aspects. Animals (Basel). (2022) 12(6):698. 10.3390/ani12060698

24.

Premont A Balthes S Marr CM Jeevaratnam K . Fundamentals of arrhythmogenic mechanisms and treatment strategies for equine atrial fibrillation. Equine Vet J. (2022) 54(2):262–82. 10.1111/evj.13518

25.

McGurrin MKJ . The diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation in the horse. Vet Med Res Rep. (2015) 6:83–90. 10.2147/VMRR.S46304

26.

Trachsel DS Schwarzwald CC Bitschnau C Grenacher B Weishaupt MA . Atrial natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I concentrations in healthy warmblood horses and in warmblood horses with mitral regurgitation at rest and after exercise. J Vet Cardiol. (2013) 15:105–21. 10.1016/j.jvc.2012.12.003

27.

Reef VB Bain FT Spencer PA . Severe mitral regurgitation in horses: clinical, echocardiographic and pathological findings. Equine Vet J. (1998) 30:18–27. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1998.tb04084.x

28.

Vernemmen I Van Steenkiste G Dufourni A Decloedt A van Loon G . Transvenous electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation in horses: horse and procedural factors correlated with success and recurrence. J Vet Intern Med. (2022) 36(2):758–69. 10.1111/jvim.16395

29.

Abdalla MA King AS . The functional anatomy of the pulmonary circulation of the domestic fowl. Respir Physiol. (1975) 23(3):267–90. 10.1016/0034-5687(75)90078-x

30.

van de Vegte YG Siland JE Rienstra M van der Harst P . Atrial fibrillation and left atrial size and function: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:8431. 10.1038/s41598-021-87859-8

31.

Yang M Chao K Wang Z Xue R Zhang X Wang D . Accelerated biological aging and risk of atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Heart Rhythm. (2025) 22(10):2507–14. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.11.017

32.

Hjalmarsson C Lindgren M Bergh N Hornestam B Smith G Adiels M et al Atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, and risk of pulmonary hypertension: a Swedish nationwide register study. J Am Heart Assoc. (2025) 14(9):e037418. 10.1161/JAHA.124.037418

33.

Pastori D Gazzaniga G Farcomeni A Bucci T Menichelli D Franchino G et al Venous thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4,170,027 patients. JACC Adv. (2023) 2(7):100555. 10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100555

34.

Pedro B Fontes-Sousa AP Gelzer AR . Diagnosis and management of canine atrial fibrillation. Vet J. (2020) 265:105549. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2020.105549

35.

Usechak PJ Bright JM Day TK . Thrombotic complications associated with atrial fibrillation in three dogs. J Vet Cardiol. (2012) 14(3):453–8. 10.1016/j.jvc.2012.04.003

36.

Chow B French A . Conversion of atrial fibrillation after levothyroxine in a dog with hypothyroidism and arterial thromboembolism. J Small Anim Pract. (2014) 55(5):278–82. 10.1111/jsap.12184

37.

Nishida K Chiba K Iwasaki YK Katsouras G Shi YF Blostein MD et al Atrial fibrillation-associated remodeling does not promote atrial thrombus formation in canine models. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2012) 5(6):1168–75. 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.974410

38.

Navas de Solis C Reef VB Slack J Jose-Cunilleras E . Evaluation of coagulation and fibrinolysis in horses with atrial fibrillation. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2016) 248:201–6. 10.2460/javma.248.2.201

39.

Kraus M Physick-Sheard P Brito LF Sargolzaei M Schenkel FS . Marginal ancestral contributions to atrial fibrillation in the standardbred racehorse: comparison of cases and controls. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0197137. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197137

40.

Kraus M Physick-Sheard PW Brito LF Schenkel FS . Estimates of heritability of atrial fibrillation in the standardbred racehorse. Equine Vet J. (2017) 49:718–22. 10.1111/evj.12687

41.

Issa ZF Miller JM Zipes DP . Typical Atrioventricular Bypass Tracts. Clinical Arrhythmology and Electrophysiology: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier (2019). p. 599–675. 10.1016/B978-0-323-52356-1.00018-9

42.

Santilli RA Perego M Perini A Moretti P Spadacini G . Electrophysiologic characteristics and topographic distribution of focal atrial tachycardia in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. (2010) 24(3):539–45. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0490.x

43.

Battaia S Perego M Cavallini D Santilli R . Localization and characterization of atrial depolarization waves on the surface electrocardiogram in dogs with rapid supraventricular tachycardia. J Vet Intern Med. (2023) 37(6):1992–2002. 10.1111/jvim.16845

44.

Van Steenkiste G Boussy T Duytschaever M Vernemmen I Schauvlieghe S Decloedt A et al Detection of the origin of atrial tachycardia by 3D electro-anatomical mapping and treatment by radiofrequency catheter ablation in horses. J Vet Intern Med. (2022) 36(4):1481–90. 10.1111/jvim.16473

45.

Van Steenkiste G De Clercq D Vera L Decloedt A van Loon G . Sustained atrial tachycardia in horses and treatment by transvenous electrical cardioversion. Equine Vet J. (2019) 51:634–40. 10.1111/evj.13073

46.

Buschmann E Van Steenkiste G Boussy T Vernemmen I Schauvliege S Decloedt A et al Three-dimensional electro-anatomical mapping and radiofrequency ablation as a novel treatment for atrioventricular accessory pathway in a horse: a case report. J Vet Intern Med. (2023) 37(2):728–34. 10.1111/jvim.16668

47.

Buschmann E Van Steenkiste G Duytschaever M Boussy T Vernemmen I Ibrahim L et al Successful caudal vena cava and pulmonary vein isolation in healthy horses using 3D electro-anatomical mapping and a contact force-guided ablation system. Equine Vet J. (2023) 56(5):1068–1076. 10.1111/evj.14037

48.

Buschman E Easton-Jones C Van Steenkiste G De Wilde H Roberts V Durando M et al Orthodromic atrioventricular reentry bradycardia and tachycardia caused by an accessory pathway in horses. J Vet Intern Med. (2025) 39(4):e70175. 10.1111/jvim.70175

49.

Zandvliet MMJM . Electrocardiography in psittacine birds and ferrets. Semin Avian Exot Pet Med. (2005) 14(1):34–51. 10.1053/j.saep.2005.12.008

50.

Einzig S Detloff BL Borgwardt BK Staley NA Noren GR Benditt DG . Cellular electrophysiological changes in “round heart disease” of turkeys: a potential basis for dysrhythmias in myopathic ventricles. Cardiovasc Res. (1981) 15(11):643–51. 10.1093/cvr/15.11.643

51.

Oster SC Jung SW Moon R . Resolution of supraventricular arrhythmia using sotalol in an adult golden eagle (Aquila Chrysaetos) with presumed atherosclerosis. J Exot Pet Med. (2019) 29:136–41. 10.1053/j.jepm.2018.10.004

52.

Vicente Steijn R Sedmera D Blom NA Jongbloed M Kvasilova A Nanka O . Apoptosis and epicardial contributions act as complementary factors in remodeling of the atrioventricular canal myocardium and atrioventricular conduction patterns in the embryonic chick heart. Dev Dyn. (2018) 247(9):1033–42. 10.1002/dvdy.24642

53.

Gilbert CJ . Common supraventricular tachycardias: mechanisms and management. AACN Adv Crit Care. (2001) 36(3):100–13. 10.1097/00044067-200102000-00011

54.

Chen YJ Chen SA Chang MS Lin CI . Arrhythmogenic activity of cardiac muscle in pulmonary veins of the dog: implication for the genesis of atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. (2000) 48(2):265–73. 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00179-6

55.

Hocini M Ho SY Kawara T Linnenbank AC Potse M Shah D et al Electrical conduction in canine pulmonary veins: electrophysiological and anatomic correlation. Circulation. (2002) 105(20):2442–8. 10.1161/01.cir.0000016062.80020.11

56.

Haïssaguerre M Jaïs P Shah DC Takahashi A Hocini M Quiniou G et al Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. (1998) 339(10):659–66. 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003

57.

Maffei A Perego M Cavallini D Santilli R . Atrial depolarization electrocardiographic features during orthodromic atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia mediated by right-sided accessory pathway in the dog. J Vet Cardiol. (2025) 61:10–9. 10.1016/j.jvc.2025.06.001

58.

Weng LC Khurshid S Hall AW Nauffal V Morrill VN Sun YV et al Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies reveals genetic mechanisms of supraventricular arrhythmias. Circ Genom Precis Med. (2024) 17(3):e004320. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.123.004320

59.

Uberoi A Stein R Perez MV Freeman J Wheeler M Dewey F et al Interpretation of the electrocardiogram of young athletes. Circulation. (2011) 124(6):746–57. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.013078

60.

Massie SL Bezugley RJ McDonald KJ Leguillette R . Prevalence of cardiac arrhythmias and R-R interval variation in healthy thoroughbred horses during official chuckwagon races and recovery. Vet J. (2021) 267:105583. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2020.105583

61.

Colucci RA Silver MJ Shubrook J . Common types of supraventricular tachycardia: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. (2010) 82(8):942–52. Available online at:https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2010/1015/p942.html(Accessed September 20, 2025).

62.

Strunk A Wilson GH . Avian cardiology. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. (2003) 6(1):1–28. 10.1016/S1094-9194(02)00031-2

63.

Moise NS Meyers-Wallen V Flahive WJ Valentine BA Scarlett JM Brown CA et al Inherited ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in German shepherd dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1994) 24:233–43. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90568-1

64.

Moise NS Dugger DA Brittain D Flahive WJ Jr Riccio ML Ernst S et al Relationship of ventricular tachycardia to sleep/wakefulness in a model of sudden cardiac death. Pediatr Res. (1996) 40:344–50. 10.1203/00006450-199608000-00025

65.

Moise NS Gilmour RF Jr Riccio ML . An animal model of spontaneous arrhythmic death. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. (1997) 8:98–103. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1997.tb00614.x

66.

Moise NS Moon PF Flahive WJ Brittain D Pride HP Lewis BA et al Phenylephrine-induced ventricular arrhythmias in dogs with inherited sudden death. J. Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (1996) 7:217–30. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00519.x

67.

Moise NS Gilmour RF Jr Riccio ML Flahive WF Jr . Diagnosis of inherited ventricular tachycardia in German SHephard dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (1997) 210(3):403–10. 10.2460/javma.1997.210.03.403

68.

Moise NS Riccio ML Kornreich B Flahive WJ Jr Golmour RF Jr . Age dependence of the development of ventricular arrhythmias in a canine model of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res. (1997) 34(3):483–92. 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00078-3

69.

Moise NS . Inherited arrhythmias in the dog: potential experimental models of cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res. (1999) 44:37–46. 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00198-4

70.

Cunningham SM Dos Santos L . Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in dogs. J Vet Cardiol. (2021) S1760-2734(21):00083–7. 10.1016/j.jvc.2021.07.001

71.

Basso C Fox PR Meurs KM Towbin JA Spier AW Calabrese F et al Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy causing sudden cardiac death in boxer dogs: a new animal model of human disease. Circulation. (2004) 109(9):1180–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118494.07530.65

72.

Meurs KM Lahmers S Keene BW White SN Oyama MA Mauceli E et al A splice site mutation in a gene encoding for PDK4, a mitochondrial protein, is associated with the development of dilated cardiomyopathy in the doberman pinscher. Hum Genet. (2012) 131:1319–25. 10.1007/s00439-012-1158-2

73.

Meurs KM Friedenberg SG Kolb J Saripalli C Tonino P Woodruff K et al A missense variant in the titin gene in doberman pinscher dogs with familial dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death. Hum Genet. (2019) 138:515–24. 10.1007/s00439-019-01973-2

74.

Calvert CA Pickus CW Jacobs GJ Brown J . Signalment, survival, and prognostic factors in doberman pinschers with end-stage cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. (1997) 11:323–6. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1997.tb00474.x

75.

Calvert CA Hall G Jacobs G . Clinical and pathologic findings in doberman pinschers with occult cardiomyopathy that died suddenly or developed congestive heart failure: 54 cases (1984–1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc. (1997) 210:501–11.

76.

Santilli RA Bontempi LV Perego M . Ventricular tachycardia in English bulldogs with localized right ventricular outflow tract enlargement. J Small Anim Pract. (2011) 52:574–80. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01109.x

77.

Crooks AV Hsue W Tschabrunn CA Gelzer AR . Feasibility of electroanatomic mapping and radiofrequency catheter ablation in boxer dogs with symptomatic ventricular tachycardia. J Vet Intern Med. (2022) 36:886–96. 10.1111/jvim.16412

78.

Meurs KM Weidman JA Rosenthal S Lahmers KK Friedenberg SG . Ventricular arrhythmias in rhodesian ridgebacks with a family history of sudden death and results of a pedigree analysis for potential inheritance patterns. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2016) 248:1135–8. 10.2460/javma.248.10.1135

79.

Santilli RA Bontempi LV Perego M . Ventricular tachycardia in English bulldogs with localized right ventricular outflow tract enlargement. J Small Anim Pract. (2011) 52:574–80. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01109.x

80.

Gilmour RF Moise NS . Triggered activity as a mechanism for inherited ventricular arrhythmias in German shepherd dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1996) 27:1526–33. 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00618-4

81.

Physick-Sheard PW McGurrin MK . Ventricular arrhythmias during race recovery in standardbred racehorses and associations with autonomic activity. J Vet Intern Med. (2010) 24(5):1158–66. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0553.x

82.

Slack J Stefanovski D Madsen TF Fjordbakk CT Strand E Fintl C . Cardiac arrhythmias in poorly performing standardbred and Norwegian-Swedish coldblooded trotters undergoing high-speed treadmill testing. Vet J. (2021) 267:105574. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2020.105574

83.

Massie SL Bezugley RJ McDonald KJ Léguillette R . Training vs. Racing: a comparison of arrhythmias and the repeatability of findings in thoroughbred chuckwagon racehorses. Vet J. (2023) 300-2:106040. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2023.106040

84.

Navas de Solis C Althaus F Basieux N Burger D . Sudden death in sport and riding horses during and immediately after exercise: a case series. Equine Vet J. (2018) 50(5):644–8. 10.1111/evj.12803

85.

Mitchell KJ . Practical considerations for diagnosis and treatment of ventricular tachycardia in horses. Equine Vet Educ. (2016) 29:670–6. 10.1111/eve.12588

86.

Korte SM Sgoifo A Ruesink W Kwakernaak C van Voorst S Scheele CW et al High carbon dioxide tension (PCO2) and the incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in rapidly growing broiler chickens. Vet Rec. (1999) 145(2):40–3. 10.1136/vr.145.2.40

87.

Chen CY Lin HY Chen YW Ko YJ Liu YJ Chen YH et al Obesity-associated cardiac pathogenesis in broiler breeder hens: pathological adaption of cardiac hypertrophy. Poult Sci. (2017) 96(7):2428–37. 10.3382/ps/pex015

88.

Olkowski AA Nain S Wojnarowicz C Laarveld B Alcorn J Ling BB . Comparative study of myocardial high energy phosphate substrate content in slow and fast growing chicken and in chickens with heart failure and ascites. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. (2007) 148(1):230–8. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.04.015

89.

Gesek M Otrocka-Domagała I SokóŁ R Paździor-Czapula K Lambert BD Wiśniewska AM et al Histopathological studies of the heart in three lines of broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci. (2016) 57(2):219–26. 10.1080/00071668.2016.1154505

90.

Olkowski AA Wojnarowicz C Nain S Ling B Alcorn JM Laarveld B . A study on pathogenesis of sudden death syndrome in broiler chickens. Poultry Sci. (2008) 85(1):131–40. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.08.006

91.

Haïssaguerre M Duchateau J Dubois R Hocini M Cheniti G Sacher F et al Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation: role of purkinje system and microstructural myocardial abnormalities. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2020) 6(6):591–608. 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.03.010

92.

Lyle CH Blissitt KJ Kennedy RN Mc Gorum BC Newton JR Parkin TDH et al Risk factors for race-associated sudden death in thoroughbred racehorses in the UK (2000-2007). Equine Vet J. (2012) 44(4):459–65. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00496.x

93.

Nath L Stent A Elliott A La Gerche A Franklin S . Risk factors for exercise-associated sudden cardiac death in thoroughbred racehorses. Animals (Basel). (2022) 12(10):1297. 10.3390/ani12101297

94.

Verheyen T Decloedt A van der Vekens N Sys S De Clercq D van Loon G . Ventricular response during lungeing exercise in horses with lone atrial fibrillation. Equine Vet J. (2013) 45(3):309–14. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00653.x

95.

Benito B Josephson ME . Ventricular tachycardia in coronary artery disease. Med Clin Barc. (2012) 65(10):939–55. 10.1016/j.recesp.2012.03.027

96.

Koplan BA Stevenson WG . Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. Mayo Clin Proc. (2009) 84(3):289–97. 10.4065/84.3.289

97.

Shiels HA . Avian cardiomyocyte architecture and what it reveals about the evolution of the vertebrate heart. J Exp Biol. (2022) 377(1864):20210332. 10.1098/rstb.2021.0332

98.

Kim DY Kim SH Ryu KH . Tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy. Korean Circ J. (2019) 49(9):808–17. 10.4070/kcj.2019.0199

99.

Ward JL DeFrancesco TC Tou SP Atkins CE Griffith EH Keene BW . Outcome and survival in canine sick sinus syndrome and sinus node dysfunction: 93 cases (2002–2014). J Vet Cardiol. (2016) 18(3):199–212. 10.1016/j.jvc.2016.04.004

100.

Santilli RA Porteiro Vazquez DM Vezzosi T Perego M . Long-term intrinsic rhythm evaluation in dogs with atrioventricular block. J Vet Intern Med. (2015) 30:58–62. 10.1111/jvim.13661

101.

Ohmori T Matsumura Y Yoshimura A Morita S Hasegawa H Hirao D et al Efficacy of cilostazol in canine bradyarrhythmia. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:954295. 10.3389/fvets.2022.954295

102.

Burrage H . Sick sinus syndrome in a dog: treatment with dual-chambered pacemaker implantation. Can Vet J. (2012) 53(5):565–8. Available online at:https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3327600/(Accessed October 1, 2025).

103.

Schrope DP Kelch WJ . Signalment, clinical signs, and prognostic indicators associated with high-grade second- or third-degree atrioventricular block in dogs: 124 cases (January 1, 1997-December 31, 1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2006) 228(11):1710–7. 10.2460/javma.228.11.1710

104.

Noszczyk-Nowak A Michalek M Kapturska K Cepiel A Janiszewski A Paslawski R et al Retrospective analysis of indications and complications related to implantation of permanent pacemaker: 25 years of experience in 31 dogs. J Vet Res. (2019) 63(1):133–40. 10.2478/jvetres-2019-0016

105.

Oyama MA Sisson DD Lehmkuhl LB . Practices and outcome of artificial cardiac pacing in 154 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. (2001) 15(3):229–39. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2001.tb02316.x

106.

Nissen SD Saljic A Kjeldsen ST Jespersen T Hopster-Iversen C Buhl R . Cartilaginous intrusion of the atrioventricular node in a quarter horse with a high burden of second-degree AV block and collapse: a case report. Animals (Basel). (2022) 12(21):2915. 10.3390/ani12212915

107.

Keen JA . Pathological bradyarrhythmia in horses. Vet J. (2020) 259-260:105463. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2020.105463

108.

Nissen SD Weis R Krag-Andersen EK Hesselkilde EM Isaksen JL Carstensen H . Electrocardiographic characteristics of trained and untrained standardbred racehorses. J Vet Intern Med. (2022) 36(3):1119–30. 10.1111/jvim.16427

109.

Nissen SD Saljic A Carstensen H Braunstein TH Hesselkilde EM Kjeldsen ST et al Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors M2 are upregulated in the atrioventricular nodal tract in horses with a high burden of second-degree atrioventricular block. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1102164. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1102164

110.

Ryan A Gurney M Steinbacher R . Suspected vagal reflex and hyperkalaemia inducing asystole in an anaesthetised horse. Equine Vet J. (2022) 54(5):927–33. 10.1111/evj.13535

111.

Luethy D Slack J Kraus MS Gelzer AR Habecker P Johnson AL . Third-degree atrioventricular block and collapse associated with eosinophilic myocarditis in a horse. J Vet Intern Med. (2017) 31(3):884–9. 10.1111/jvim.14682

112.

Hesselkilde EZ Almond ME Petersen J Flethoj M Praestegaard KF Buhl R . Cardiac arrhythmias and electrolyte disturbances in colic horses. Acta Vet Scand. (2014) 56(58). 10.1186/s13028-014-0058-y

113.

Machida N Hirakawa A . The anatomical substrate for sick Sinus syndrome in dogs. J Comp Pathol. (2021) 189:125–34. 10.1016/j.jcpa.2021.10.007

114.

Szlosek DA Castaneda EL Grimaldi DA Spake AK Estrada AH Gentile-Solomon J . Frequency of arrhythmias detected in 9440 feline electrocardiograms by breed, age and sex. J Vet Cardiol. (2024) 51:116–23. 10.1016/j.jvc.2023.11.004

115.

Kittleson MD Cote E . The feline cardiomyopathies: 1. General Concepts. J Feline Med Surg. (2021) 23(11):1009–27. 10.1177/1098612X211021819

116.

Fox PR Maron BJ Basso C Liu SK Thiene G . Spontaneously occurring arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in the domestic cat: a new animal model similar to the human disease. Circulation. (2000) 102(15):1863–70. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.15.1863

117.

Cote E Harpster NK Laste NJ MacDonald KA Kittleson MD Bond BR et al Atrial fibrillation in cats: 50 cases (1979–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2004) 225(2):256–60. 10.2460/javma.2004.225.256

118.

Greet V Sargent J Brannick M Fuentes VL . Supraventricular tachycardia in 23 cats; comparison with 21 cats with atrial fibrillation (2004–2014). J Vet Cardiol. (2020) 30:7–16. 10.1016/j.jvc.2020.04.007

119.

Meurs KM Norgard MM Kuan M Haggstrom J Kittleson M . Analysis of 8 sarcomeric candidate genes for feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. (2009) 23(4):840–3. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0341.x

120.

Kettleson MD Cote E . The feline cardiomyopathy: 3. Cardiomyopathies other than HCM. J Feline Med Surg. (2021) 23(11):1053–67. 10.1177/1098612X211030218

Summary

Keywords

comparative electrophysiology, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, veterinary cardiology, translational medicine, breed-specific arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, cross-species thromboresistance

Citation

Natterson-Horowitz B, Wright K, Van Steenkiste G, Decloedt A, Gagnon AL, Cai X and Mazmanian A (2026) Arrhythmias across the tree of life: comparative insights for human electrophysiology. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1652591. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1652591

Received

23 June 2025

Revised

18 November 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

06 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

DeLisa Fairweather, Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, United States

Reviewed by

Carlo Guglielmini, University Hospital of Padua, Italy

Szymon Graczyk, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Natterson-Horowitz, Wright, Van Steenkiste, Decloedt, Gagnon, Cai and Mazmanian.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Barbara Natterson-Horowitz natterson-horowitz@fas.harvard.edu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.