The figures were in the wrong order in the PDF and HTML version of this paper. Figure 2 should have been figure 3 and vice versa. The order has now been corrected.

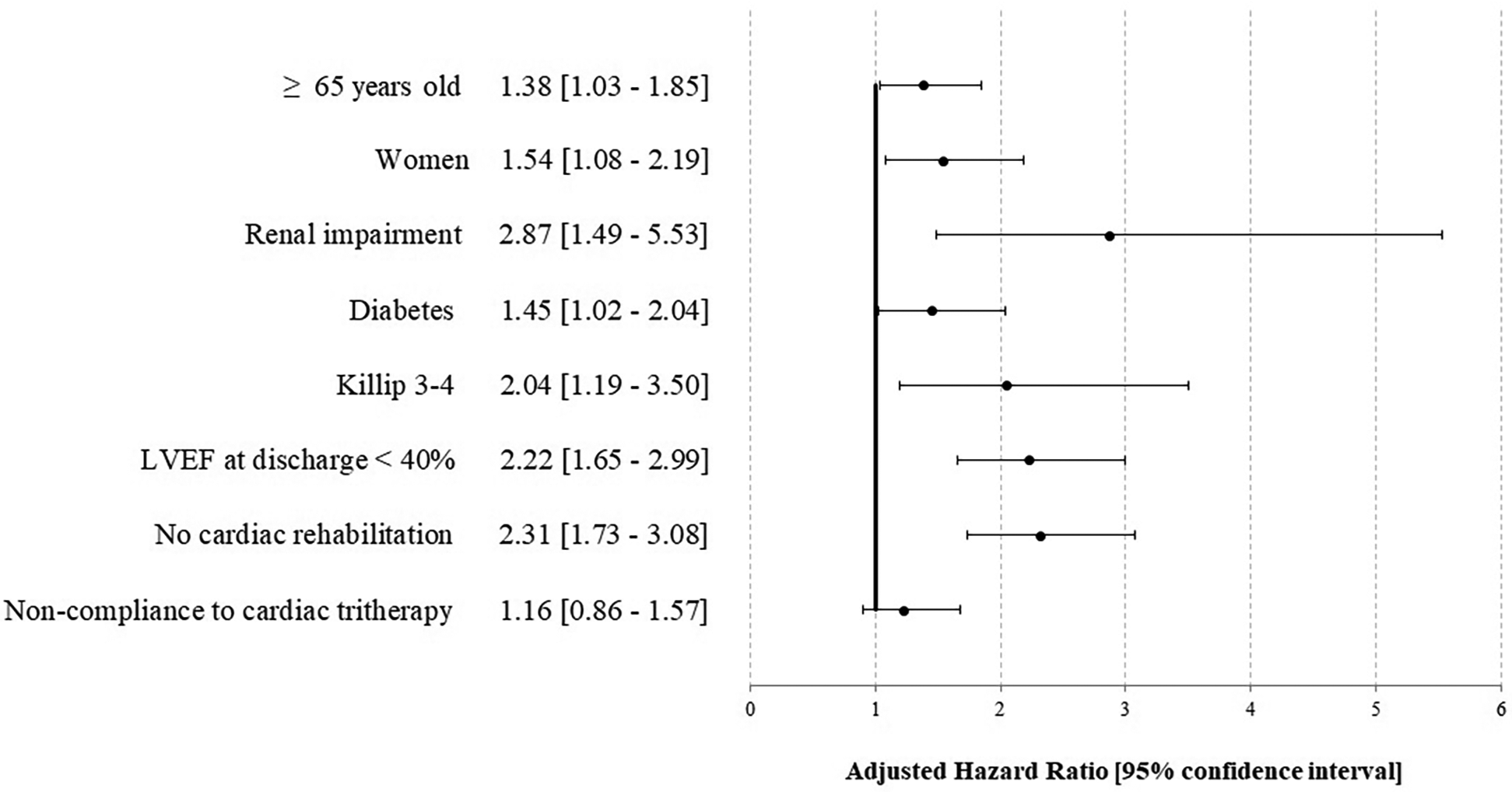

Figure 2

Factors associated with an ischemic complication and/or death at 1 year after STEMI—the STOP—SCA+ study. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

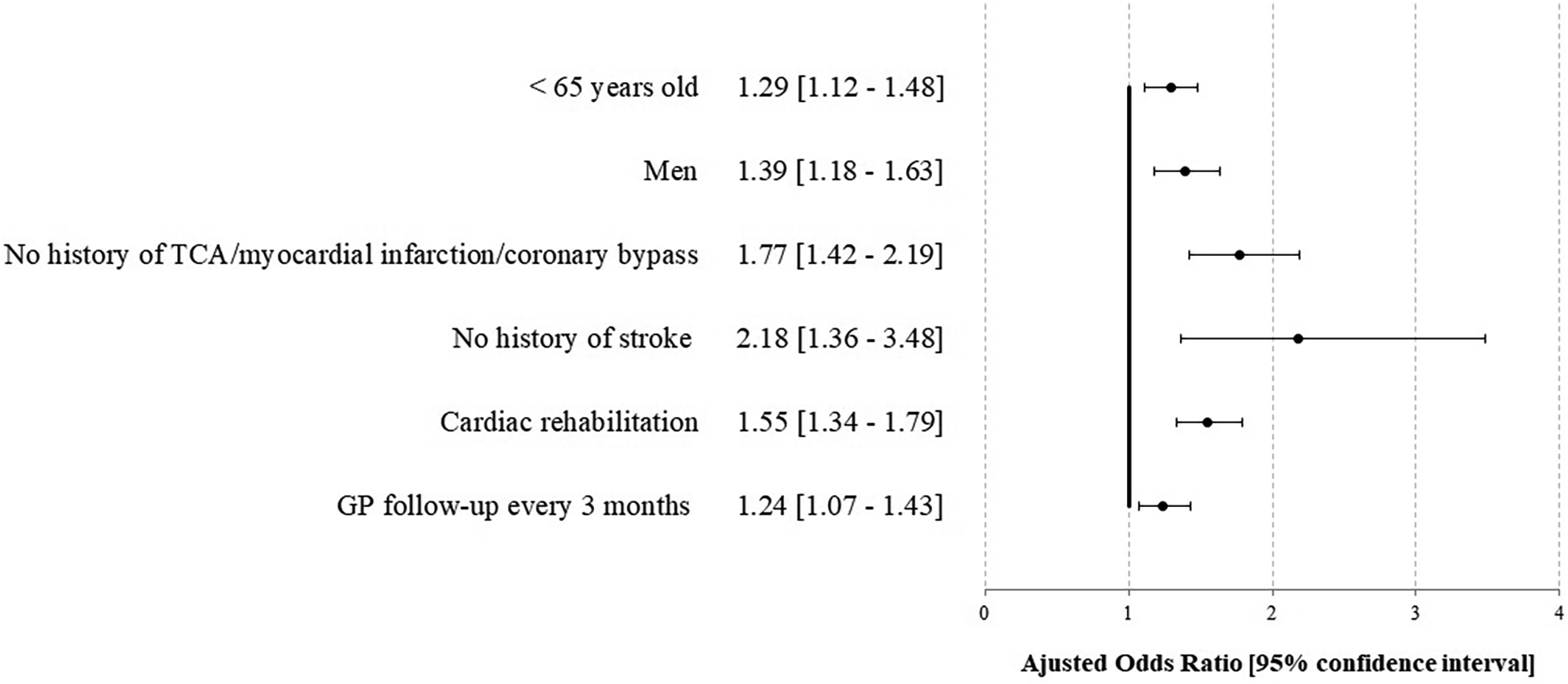

Figure 3

Factors associated with compliance for the cardiac tri-therapy (PDC ≥80%) at 1 year after STEMI-the STOP-SCA+ study. TCA, transluminal coronary angioplasty; GP, general practitioner.

The original version of this article has been updated.

Statements

Generative AI statement

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Summary

Keywords

myocardial infarction (MI), cardiac rehabilitation, compliance, outcome, probabilistic matching

Citation

Laurent E, Godillon L, Tassi M-F, Marcollet P, Chassaing S, Decomis M, Bezin J, Laure C, Angoulvant D, Range G and Grammatico-Guillon L (2025) Correction: Impact of cardiac rehabilitation and treatment compliance after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in France, the STOP SCA+ study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1656799. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1656799

Received

30 June 2025

Accepted

27 August 2025

Published

11 September 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited and reviewed by

Tommaso Gori, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Laurent, Godillon, Tassi, Marcollet, Chassaing, Decomis, Bezin, Laure, Angoulvant, Range and Grammatico-Guillon.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Lucile Godillon l.godillon@chu-tours.fr; leslie.guillon@univ-tours.fr

ORCID Lucile Godillon orcid.org/0000-0002-3852-2846

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.