Abstract

Background:

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is an important biomarker in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). We aimed to explore changes in BNP and their relationship with long-term dynamics of left ventricular (LV) geometry.

Methods:

This was a single-center retrospective cohort. Inclusion criteria included LV ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40% measured by echocardiography, BNP ≥100 pg/mL at baseline, and a subsequent BNP measure within a year. Percent BNP change from baseline was computed and divided into tertiles. Percent change tertiles represented decreasing (min—max, −63.3 to −10.4), minimal changes (−10.4 to 2.8), and rising BNP levels (2.9 to 12.6). The study endpoint included LV internal dimension at end-systole (LVIDs), LV internal dimension at end-diastole (LVIDd), and LVEF. The secondary endpoint consisted of all-cause mortality.

Results:

A total of 887 patients were included. Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, baseline BNP, and LVEF, varied among tertiles (p < 0.05). When comparing to the rising BNP tertile, the decreasing BNP tertile showed decreased trends of LVIDs (p = 0.001), LVIDd (p = 0.006); and increased trends of LVEF (p = 0.008). All-cause mortality was higher in the rising BNP tertile (p < 0.05) compared to the decreasing tertile.

Conclusion:

In a real-world routine HFrEF cohort, this study demonstrates the time-dependent relationship between BNP changes, LV remodeling dynamics, and survival outcomes. Findings contribute to the literature supporting BNP as a dynamic marker for LV remodeling.

Introduction

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is an important clinical biomarker in heart failure (HF) (1). Elevated BNP levels are strongly indicative of HF, and are commonly utilized in clinical practice to guide management (2). The ventricular myocardium secretes this BNP in response to increased wall stress and pressure overload (3). It is a counter-regulatory hormone that promotes vasodilation, natriuresis, and diuresis (4).

A key pathophysiological process in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is left ventricular (LV) remodeling (5). The LV remodeling is marked by progressive dilation, wall thinning, and reduced contractile function (6). Importantly, LV remodeling correlates with adverse clinical outcomes (7, 8). Thus, LV remodeling is an important marker in HFrEF.

While the relationship between natriuretic peptides and LV remodeling exists, the relationship between changes in BNP and time-dependent LV remodeling has not been extensively studied in real-world settings (6, 9, 10). Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the association between changes in BNP and long term LV remodeling in real-world clinical data. We hypothesized that patients who experience greater reductions in BNP levels would demonstrate more favorable LV remodeling and survival outcomes.

Methods

Data source, study design, and inclusion criteria

We conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study using data collected from the University of California, Davis Medical Center. Data was collected through the institution's electronic health record data warehouse using a time frame between January 2014 to December 2022. Inclusion criteria for the HFrEF cohort consisted of adults aged ≥18 years, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) HF codes (ICD-9 or ICD-10), LVEF ≤40%, and BNP ≥100 pg/mL. Exclusion criteria included patients with ICD codes for cardiac transplant or left ventricular assist device implantation, those without follow-up LVEF values, and those with less than a one-year interval between their first and second BNP measurements. The cohort has been previously validated with a specificity of 0.96 and a sensitivity of 0.60 as compared with physician chart review (11).

Baseline definitions

The cohort index date was defined as the date of the first recorded LVEF ≤40%. Demographic variables included age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Baseline laboratory, echocardiogram, and electrocardiogram characteristics were defined as the first value within 90 days or the first available after the indexation date. Comorbidities were defined as diagnoses prior to the cohort index date, and validated comorbidity identification methodologies were used. For this study, we defined guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) utilization as the prescription of medications within 6 months prior to and within 3 months after the cohort indexation date. Medications included renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi), β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2). The RASi category comprised angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, and angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor. Patients were placed into one of three dosing categories based on their recorded prescription: either none, <50%, or ≥50% of GDMT target dosing.

Longitudinal data and cohort stratification

Longitudinal laboratory, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram variables were extracted, starting from the cohort indexation date until the last available LVEF measurement. After BNP log transformation, percent BNP changes from baseline at one-year were computed, then the cohort was stratified into low, middle, and high BNP change tertiles.

Study outcomes

The co-primary outcomes were LV internal dimension at end-systole (LVIDs), LV internal dimension at end-diastole (LVIDd), and LVEF, all measured by echocardiography. The secondary outcome included all-cause mortality. All-cause mortality data was retrieved from the institution's clinical data warehouse. However, cause-specific mortality was not available.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Between-group comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables or ANOVA, and chi-squared or Fisher exact test for categorical variables as appropriate.

For outcome analysis, linear mixed models were performed to assess changes between BNP change groups and the endpoints over time. An exploratory multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to explore GDMT association to BNP tertile changes adjusted for potential factors influencing GTMT use (age, sex, blood pressure, heart rate, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, creatinine and K+). A Cox regression model was constructed for survival analysis adjusting for relevant covariates known to influence BNP levels (age, sex, BMI, atrial fibrillation, baseline BNP, creatinine, and LVEF were included) (12). Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics

The university's Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all data used were de-identified before analysis.

Results

Cohort identification and BNP change tertile stratification

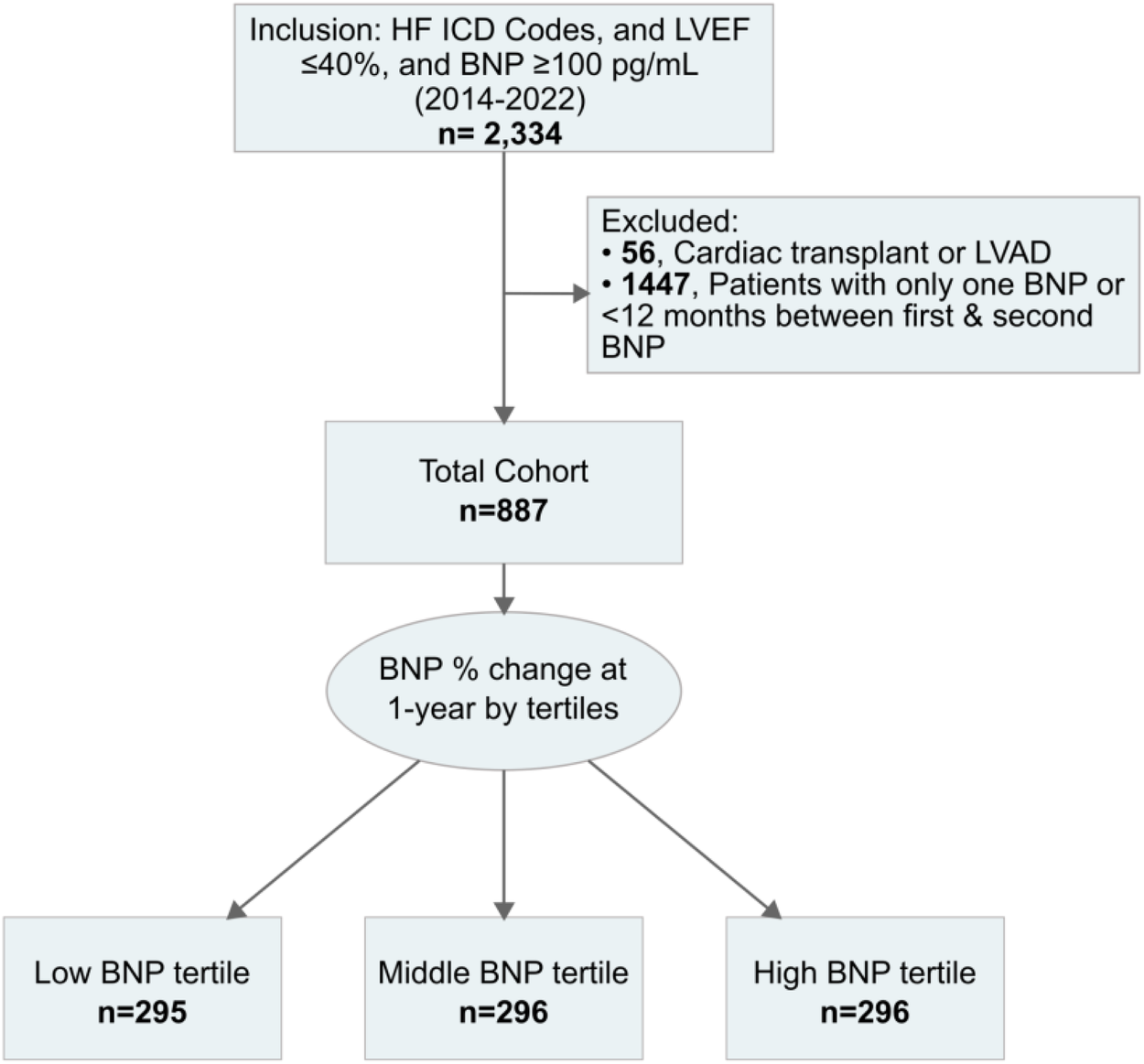

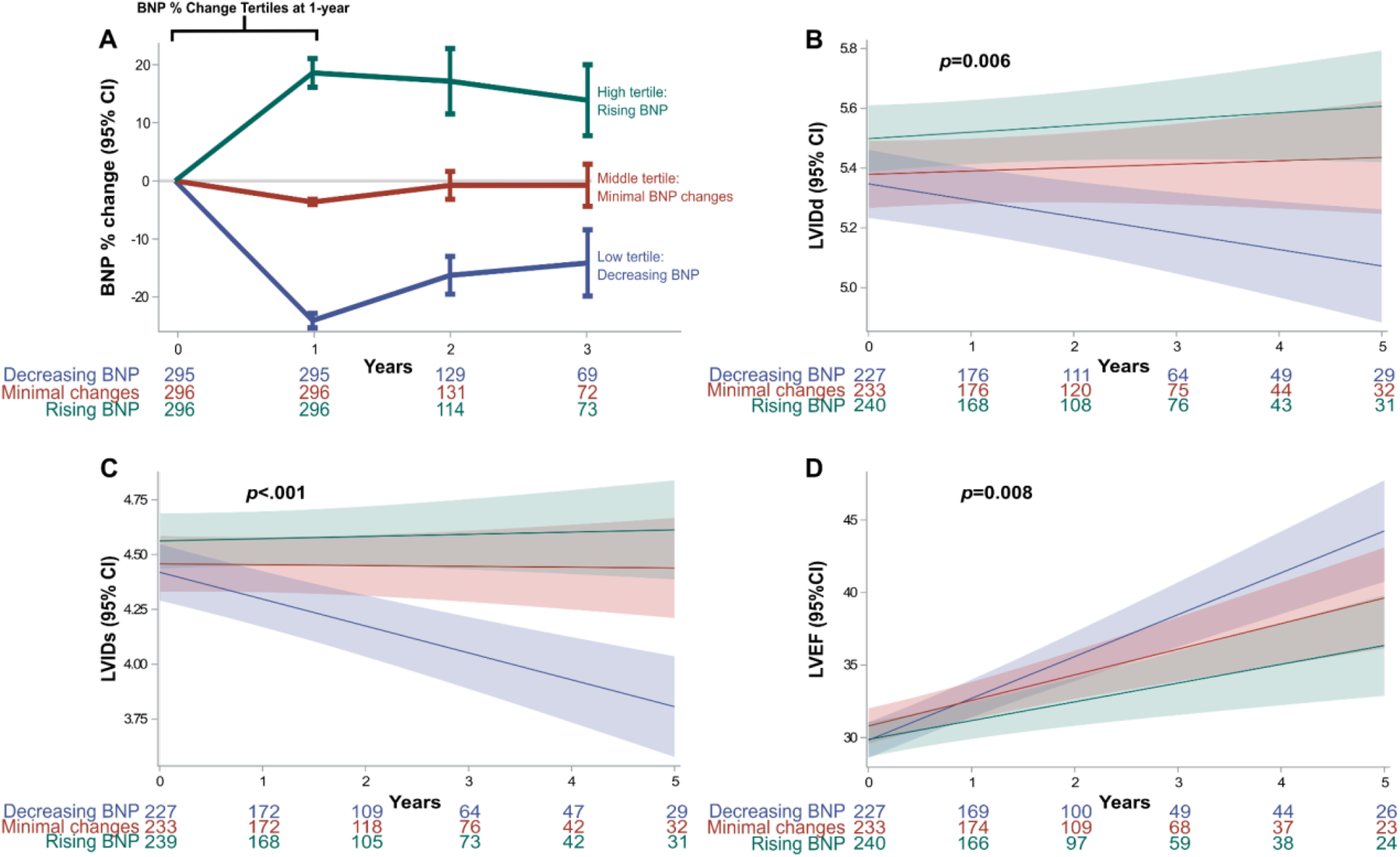

An initial 2,334 patients were included. However, in the final cohort, only 887 cases met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Percent changes in BNP at one-year were categorized into tertiles: low tertile (n = 295), middle tertile (n = 296), and high tertile (n = 296). Corresponding to decreasing, minimal changes, and worsening BNP levels (Figure 1). The decreasing BNP tertile had a mean BNP reduction of −24% (95% CI, −25% to −22%); the rising BNP group had a mean increase of 18% (95% CI, 16%–21%); the minimal BNP change tertile showed a decrease of −4% (95% CI, −4% to −3%), see Figure 2A.

Figure 1

Cohort identification workflow. BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; HF, heart failure; ICD Codes, international classification of diseases codes; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 2

BNP tertile changes and co-primary endpoints. (A) Absolute BNP percent change at one-year from baseline: The first year was used to categorize groups based on BNP percent change tertiles. (B–D) Co-primary outcomes assessing echocardiographic LV geometry and function showed long-term changes between the BNP change groups. Mixed linear model showed significant differences in LVIDs (p < 0.006), LVIDd (p < .001) and LVEF (p < 0.008). BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, LV internal dimension at end-diastole; LVIDs, LV internal dimension at end-systole.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics varied across BNP tertiles (Table 1). Patients in the decreasing BNP tertile were younger, a median age of 61 years (IQR 53.0–70.5), vs. a median of 65 years (IQR 56.0–77.0) in the rising BNP tertile (p < 0.001). Overall, the cohort was predominantly male (68.8%) with a higher male proportion in the minimal changes and rising tertiles groups (73.0% and 69.6%, respectively). Hispanic comprised a 21.4% of the decreasing BNP tertile (p < 0.001). Blood pressure and heart rate were elevated in the decreasing BNP tertile group (80.0 mmHg, p = 0.022; and 91.0 bpm, p = 0.004, respectively). The minimal BNP changes group presented the highest rates of atrial fibrillation patients (41.2%, p = 0.007).

Table 1

| Median (IQR) or No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Miss | Overall (n = 887) | Low tertile, decreasing BNP | Middle tertile, minimal BNP changes | High tertile, rising BNP | P * |

| Tertile min-max | −63.3 to −10.4 | −10.4 to 2.8 | 2.9 to 12.6 | |||

| (n = 295) | (n = 296) | (n = 296) | ||||

| Age, years | 0 | 64 (55–75) | 61 (53.0–70.5) | 65 (57–77) | 65 (56–77) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0 | 0.049 | ||||

| Male | 610 (68.8) | 188 (63.7) | 216 (73.0) | 206 (69.6) | ||

| Race | 0 | 0.075 | ||||

| White | 506 (57.0) | 148 (50.2) | 187 (63.2) | 171 (57.8) | ||

| Black | 159 (17.9) | 61 (20.7) | 46 (15.5) | 52 (17.6) | ||

| Asian | 46 (5.2) | 13 (4.4) | 14 (4.7) | 19 (6.4) | ||

| Hawaiian/Native American | 23 (2.6) | 7 (2.4) | 7 (2.4) | 9 (3.0) | ||

| Other | 146 (16.4) | 63 (21.3) | 40 (13.5) | 43 (14.5) | ||

| Unavailable | 7 (0.8) | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0 | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 761 (85.8) | 229 (77.6) | 271 (91.6) | 261 (88.2) | ||

| Hispanic | 120 (13.5) | 63 (21.4) | 24 (8.1) | 33 (11.1) | ||

| Unavailable | 6 (0.7) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Vitals/biometrics | ||||||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 3 | 125 (111–142) | 126 (110–143) | 121 (109–139) | 128 (113–143.8) | 0.100 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 3 | 77 (67–89) | 80 (68–92) | 76 (66–87) | 76 (68–88) | 0.022 |

| MAP, mmHg | 3 | 94 (82.7–105.3) | 96.7 (82.2–106.3) | 90.7 (81.8–103.7) | 94 (84.1–105.0) | 0.068 |

| Heart Rate, beats/min | 1 | 89 (77–102) | 91 (80–105) | 88 (76–102) | 86 (75–99.2) | 0.004 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 91 | 28.4 (24.6–33.4) | 28.2 (24.9–32.9) | 28.7 (24.8–32.8) | 28.2 (24.3–33.8) | 0.934 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Hypertension | 8 | 639 (72.7) | 215 (73.4) | 201 (69.1) | 223 (75.6) | 0.198 |

| Diabetes | 8 | 402 (45.7) | 130 (44.4) | 123 (42.3) | 149 (50.5) | 0.114 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8 | 390 (44.4) | 123 (42.0) | 125 (43.0) | 142 (48.1) | 0.271 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 8 | 325 (37.0) | 96 (32.8) | 118 (40.5) | 111 (37.6) | 0.144 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 8 | 301 (34.2) | 86 (29.4) | 120 (41.2) | 95 (32.2) | 0.007 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 8 | 244 (27.8) | 77 (26.3) | 77 (26.5) | 90 (30.5) | 0.432 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| BNP, pg/mL | 0 | 663 (298–1,305) | 837 (419–1,553) | 698 (362.5–1,344.5) | 433.5 (139.2–981.0) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 777 | 1,259.5 (353.8–2,896.2) | 922 (237–2,520) | 2,045.5 (952.5–3,485.0) | 874 (355.5–2,414.5) | 0.056 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 0 | 137 (135–139) | 137 (135–139) | 137 (135–139) | 137.5 (135–139) | 0.675 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 0 | 4 (3.7–4.4) | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 4.1 (3.7–4.4) | 4 (3.7–4.4) | 0.003 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.101 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 39 | 56 (45–60) | 57 (48–67) | 56 (43.5–60) | 55 (44–60) | 0.182 |

| Echocardiogram | ||||||

| LVEF, % | 0 | 30 (25–35) | 30 (20–35) | 30 (25–40) | 30 (25–35) | <0.001 |

| IVSd, cm | 1 | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 0.140 |

| LVIDd, cm | 2 | 5.7 (5.1–6.3) | 5.7 (5.1–6.3) | 5.6 (5.1–6.3) | 5.6 (5.1–6.2) | 0.376 |

| LVIDs, cm | 6 | 4.8 (4.1–5.5) | 4.9 (4.2–5.6) | 4.7 (4.1–5.5) | 4.7 (4.1–5.3) | 0.203 |

| PASP, mmhg | 56 | 41.8 (31.7–50.2) | 42.6 (31.8–50.1) | 42.5 (33.0–51.2) | 38.9 (29.7–49.4) | 0.113 |

| PW, cm | 2 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.195 |

| TAPSE, cm | 19 | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | 0.046 |

| Electrocardiogram | ||||||

| QTc, ms | 8 | 500 (474–531) | 497 (474.8–530.2) | 503 (476.0–534.8) | 499 (471–528) | 0.203 |

| GDMT & target doseΔ | ||||||

| RASiş | 147 | 0.022 | ||||

| none | 139 (18.8) | 47 (18.6) | 57 (22.5) | 35 (15.0) | ||

| <50% target | 309 (41.8) | 97 (38.3) | 116 (45.8) | 96 (41.0) | ||

| ≥50% target | 292 (39.5) | 109 (43.1) | 80 (31.6) | 103 (44.0) | ||

| β-Blocker | 147 | 0.061 | ||||

| none | 270 (36.5) | 85 (33.6) | 83 (32.8) | 102 (43.6) | ||

| <50% target | 247 (33.4) | 82 (32.4) | 93 (36.8) | 72 (30.8) | ||

| ≥50% target | 223 (30.1) | 86 (34.0) | 77 (30.4) | 60 (25.6) | ||

| MRA | 147 | 0.057 | ||||

| none | 455 (61.5) | 143 (56.5) | 155 (61.3) | 157 (67.1) | ||

| <50% target | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ≥50% target | 285 (38.5) | 110 (43.5) | 98 (38.7) | 77 (32.9) | ||

| SGLT2i | 147 | 62 (8.4) | 26 (10.3) | 21 (8.3) | 15 (6.4) | 0.306 |

| GDMT Triple therapy | 147 | 149 (20.1) | 60 (23.7) | 50 (19.8) | 39 (16.7) | 0.150 |

| GDMT Triple therapy, ≥50% target | 147 | 40 (5.4) | 21 (8.3) | 9 (3.6) | 10 (4.3) | 0.040 |

| Loop diuretics | 0 | 866 (97.6) | 290 (98.3) | 290 (98.0) | 286 (96.6) | 0.362 |

Patient baseline characteristics by tertile percent changes.

BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; IVSd, interventricular septum thickness at end-diastole; LVEDd, left ventricle end diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension at end -diastole; LVIDs, left internal dimension at end -systole; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal (NT)-pro hormone BNP; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PW, left ventricular posterior wall; QTc, QT corrected for heart rate; RASi, renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor; SGLT2i, sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

p-values comparing all BNP tertile groups using Chi-squared or Kruskal–Wallis.

Target doses of guideline directed medical therapy (GDMT) as recommended in treatment guidelines.

RASi consisted of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor.

Table 2

| GDMT | Percent change tertiles vs. minimal BNP changes (reference) | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASi | Decreasing BNP tertile vs. reference | 0.84 | 0.53–1.34 | 0.47 |

| Increasing BNP tertile vs. reference | 0.63 | 0.39–1.02 | 0.06 | |

| β-Blocker | Decreasing BNP tertile vs. reference | 1.16 | 0.78–1.73 | 0.47 |

| Increasing BNP tertile vs. reference | 1.68 | 1.13–2.49 | 0.01 | |

| MRA | Decreasing BNP tertile vs. reference | 0.83 | 0.57–1.22 | 0.35 |

| Increasing BNP tertile vs. reference | 1.27 | 0.86–1.88 | 0.23 |

GDMT use and tertile BNP tertile changes, multinomial logistic regression.

A multinomial logistic regression analysis was adjusted for potential factors influencing GTMT use included baseline age, sex, blood pressure, heart rate, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, creatinine and K+.

GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; RASi, renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; OR, odds ratio; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide.

The decreasing BNP group had elevated BNP levels, a median of 837.0 pg/mL (IQR 419.0–1,553.0) when compared to the other tertiles (p < 0.001). Potassium levels were elevated in the minimal changes and rising BNP tertiles (p = 0.003). Minimal changes and rising BNP tertiles had a higher LVEF. Baseline TAPSE (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion) was also higher in the rising BNP tertile (p = 0.046).

The use of GDMT analysis showed that RASi were prescribed more frequently in the rising BNP group. However, the decreasing BNP group had a higher use of GDMT triple therapy at ≥50% target doses (8.3%, p = 0.040). The exploratory multivariate analysis resulted in Beta-blocker and increasing BNP levels [odds ratio [OR] 1.68; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13–2.49, p = 0.01]. Less RASi use and increasing BNP group (OR 0.63, 95% CI: 0.39–1.02, p = 0.06). The MRA therapy use did not differ (OR: 0.86–1.88, p = 0.23).

Primary outcomes: changes in LV geometry and function

Linear mixed models for LVIDd different trajectories between tertiles (p = 0.006). The decreasing BNP group demonstrated a steady decrease in LVIDd, Figure 2B. Similarly, LVIDs steadily decreased in the decreasing BNP tertile (p < 0.001), Figure 2C. Finally, the decreasing BNP tertile exhibited an improvement in LVEF over time (p = 0.008), Figure 2D.

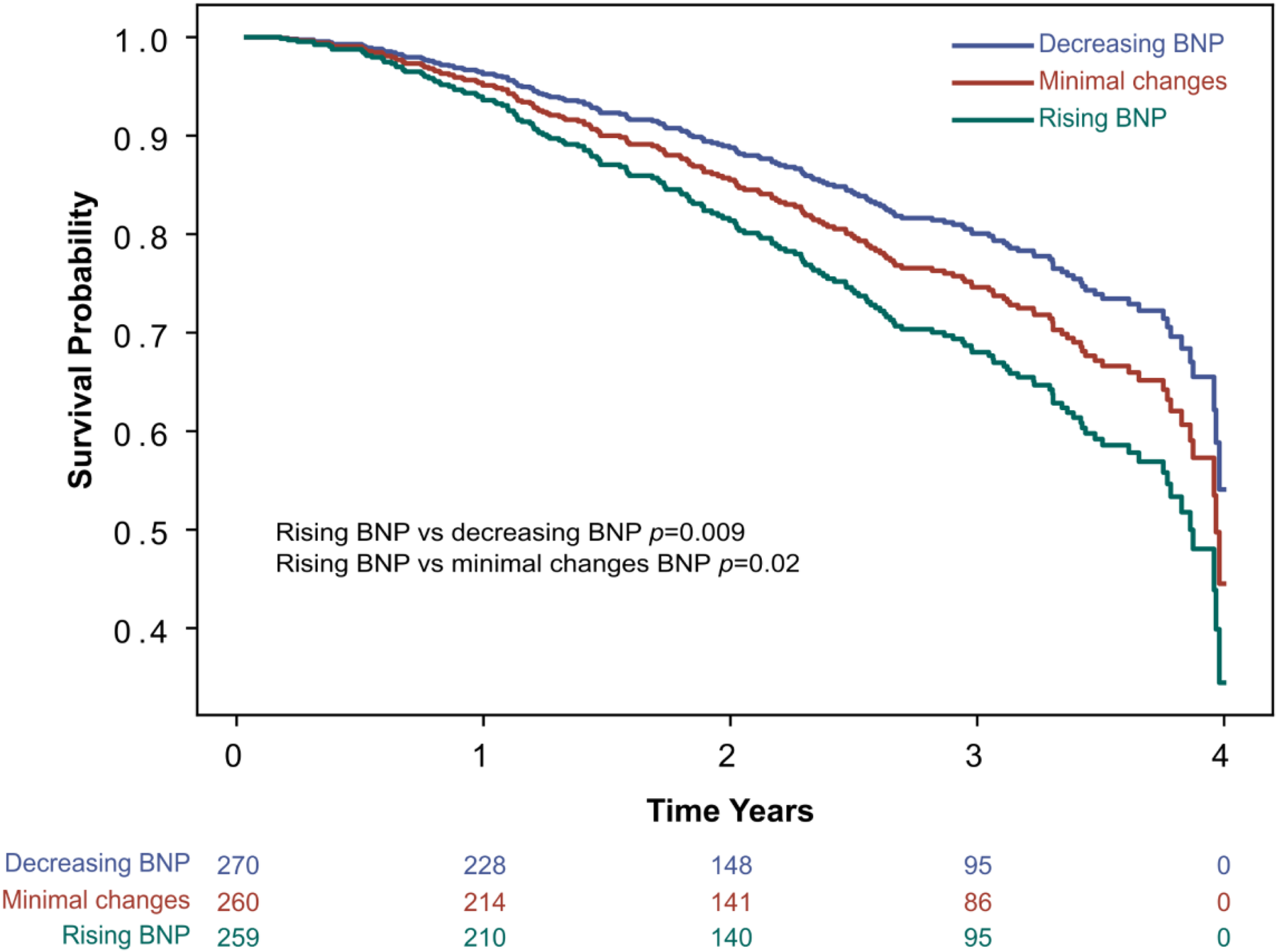

Secondary outcome: all-cause mortality

Cox regression analysis adjusted for clinically relevant covariates resulted in worse survival outcomes for the rising BNP tertile when compared to decreasing BNP (p = 0.009) and minimal BNP changes (p = 0.02), see Figure 3. Clinically relevant covariates included age, years, sex, BMI, heart rate, atrial fibrillation, baseline BNP, creatinine, and LVEF.

Figure 3

Secondary endpoint: all-cause mortality. Survival curve for all-cause mortality by BNP tertile change groups, adjusted for covariates in a Cox regression model. The Cox regression model was adjusted for potential clinically relevant covariates affecting BNP levels, including age in years, sex, BMI, atrial fibrillation, baseline BNP, creatinine, and LVEF. BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort, the results suggest an association between one-year changes in BNP levels and long-term LV remodeling in patients with HFrEF. Specifically, patients who experienced early reductions in BNP levels demonstrated favorable long-term LV remodeling and improved overall mortality outcomes. Findings underscore BNP changes as a dynamic marker for LV function.

Cohort characteristics and BNP tertile interpretation

Baseline characteristics in Table 1, provide insights into the varying profiles across BNP tertiles. Compared to other groups, the decreasing BNP group comprised younger, higher proportion of females, and Hispanics, and higher blood pressure and heart rate values. In addition, it presented the lowest atrial fibrillation rates. In terms of HF severity, the decreasing BNP tertile had higher BNP levels at baseline, worse LVEF, and lower TAPSE compared to other groups. Finally, the use of RASi and GDMT Triple therapy at ≥50% was higher in this group. Taken together, the decreasing BNP group is indicative of younger patients with more severe HF but a better compensatory state and/or greater responsiveness to treatment (13).

The multivariate regression comparing BNP change tertiles and GDMT was adjusted for known factors that may affect GDMT use (Table 2). Beta-blocker use was significantly associated with the increasing BNP tertile, possibly reflecting more severe disease or symptomatic disease requiring therapy. Less RASi use presented borderline association with increasing BNP, suggesting possible underuse in more advanced heart failure. The MRA therapy use did not differ across groups.

Interpretation of primary and secondary endpoints

The outcome analysis supports the hypothesis that BNP reductions at one-year is associated with favorable long-term LV remodeling and overall survival. The decreasing BNP tertile, characterized by substantial reductions in BNP from the indexation cohort date, showed significantly better LVIDd, LVIDs, and LVEF trajectories. This suggests that BNP changes may serve as an early predictive marker for long-term LV function. These findings are consistent with prior studies in myocardial infarction cohorts, where BNP has been shown to predict LV remodeling over time (6, 14).

BNP is a cardiac natriuretic peptide hormone primarily produced by ventricular myocytes. The primary stimulus for synthesis and secretion is myocyte stretch. The biological effects include diuresis, natriuresis, vasodilatation, inhibition of renin and aldosterone production, and regulation of cardiac and vascular myocyte growth (15). BNP acts as an endogenous brake on signaling pathways that drive the progression from LV hypertrophy through remodeling, heart failure, and death (16). Multiple studies have demonstrated BNP's anti-hypertrophic effects in both exogenous and endogenous experimental settings (17, 18).

Prior studies have shown that BNP levels can be valuable for prognosis. One study found that in a cohort of MI survivors over six months, patients with LV remodeling had higher levels of BNP on days 7, 90, and 180 compared to those without LV remodeling (19). Another study reported that in a cohort of MI survivors over one year, N-BNP levels were higher in patients with larger myocardial scars, which are identified as a major determinant of LV remodeling (20). While the relationship of LV remodeling and BNP is well established (6), long term longitudinal studies with serial imaging and biomarker data are limited due to the complexity and effort of longitudinal studies. Most relevant studies are short to mid term 6 to 12 months from secondary analyses (9, 21, 22). Our findings contribute to shading light on long term remodeling and BNP presenting 5 years of imaging and BNP relationships. HF is a dynamic disease, is important to characterize the dynamic changes and trajectories vs. as highlighted elsewhere (23–25).

Due to the mechanisms triggering BNP production and its biological effects, elevated BNP levels can reflect both LV systolic dysfunction and the body's compensatory response (26). These findings suggest that a BNP downtrend may be associated with improved systolic function, leading to a decrease in LV end-diastolic volume, reduced LV wall stress, and diminished BNP production. This can explain why patients with greater BNP reductions over the course of a year exhibited decreased LVIDs, lower LVIDd, and increased LVEF, which can be surrogate signs of LV remodeling improvement. Improved BNP and LV function directly translates into better survival outcomes.

Clinical implications

In this study, we demonstrated that patients in the low BNP tertile had reduced LVIDs and LVIDd and increased LVEF compared to those in the high BNP tertile. These findings suggest that BNP dynamic reduction is indicative of LV remodeling improvement in a time-dependent fashion. Therefore, contributing to the literature of the relationship of BNP and LV remodeling dynamics.

Study limitations

Limitations should be considered, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations due the single-center retrospective design. In addition, findings should be interpreted as associations rather than causal relationships. Cohort identification required follow-up BNP data, which may select more compliant or healthier patients, an inherent limitation of observational studies. While other factors during follow up can influence BNP or LV such as GDMT titration, adherence and device therapy, this was not explored. Limited NR-proBNP data available, due to system and provider causes most likely. Cause-specific mortality data was not collected in our institution, cause specific mortality analysis was not feasible.

Conclusion

In a real-world routine HFrEF cohort, his study suggests that BNP changes within one year are associated with LV remodeling dynamics in the long term. Greater BNP reductions were associated with more favorable LV function, structural remodeling, and better all-cause mortality. Findings contribute to the growing literature of BNP as a dynamic marker for LV remodeling.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: IRB approval was made for data collection analysis and publication, however, sharing data outside of the UC Davis team was not granted. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to MC, mcadeiras@ucdavis.edu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by This study was reviewed and approved by UC Davis IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from a by- product of routine care or industry. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ER: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by NIH HeartShare (NIH U01HL160274) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (grant 23SFRNPCS1064232, 23SFRNPCS1060482, and 23SFRNCCS1052478).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge important contributions from Daniel Mendoza-Quispe and Kafayat Omadevuae.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, international classification of diseases; LV, left ventricular; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole; LVIDs, left ventricular internal dimension at end-systole; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; RASi, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors; SGLT-2, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors.

References

1.

Chow SL Maisel AS Anand I Bozkurt B de Boer RA Felker GM et al Role of biomarkers for the prevention, assessment, and management of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2017) 135(22):e1054–91. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000490

2.

Heidenreich PA Bozkurt B Aguilar D Allen LA Byun JJ Colvin MM et al 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 79(17):e263–421. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012

3.

Ibrahim NE Januzzi JL . Established and emerging roles of biomarkers in heart failure. Circ Res. (2018) 123(5):614–29. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312706

4.

Kuwahara K . The natriuretic peptide system in heart failure: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 227:107863. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107863

5.

Frantz S Hundertmark MJ Schulz-Menger J Bengel FM Bauersachs J . Left ventricular remodelling post-myocardial infarction: pathophysiology, imaging, and novel therapies. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(27):2549–61. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac223

6.

Aimo A Gaggin HK Barison A Emdin M Januzzi JL . Imaging, biomarker, and clinical predictors of cardiac remodeling in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2019) 7(9):782–94. 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.06.004

7.

Xu L Pagano J Chow K Oudit GY Haykowsky MJ Mikami Y et al Cardiac remodelling predicts outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. (2021) 8(6):5352. 10.1002/ehf2.13626

8.

Lindman BR Asch FM Grayburn PA Mack MJ Bax JJ Gonzales H et al Ventricular remodeling and outcomes after mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair in heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2023) 16(10):1160–72. 10.1016/j.jcin.2023.02.031

9.

Daubert MA Adams K Yow E Barnhart HX Douglas PS Rimmer S et al NT-proBNP Goal achievement is associated with significant reverse remodeling and improved clinical outcomes in HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail. (2019) 7(2):158–68. 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.10.014

10.

Shiba M Kato T Morimoto T Yaku H Inuzuka Y Tamaki Y et al Changes in BNP levels from discharge to 6-month visit predict subsequent outcomes in patients with acute heart failure. PLoS One. (2022) 17(1):e0263165. 10.1371/journal.pone.0263165

11.

Romero E Baltodano AF Rocha P Sellers-Porter C Patel DJ Soroya S et al Clinical, echocardiographic, and longitudinal characteristics associated with heart failure with improved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. (2024) 211:143–52. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.10.086

12.

Tsutsui H Albert NM Coats AJS Anker SD Bayes-Genis A Butler J et al Natriuretic peptides: role in the diagnosis and management of heart failure: a scientific statement from the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology, heart failure society of America and Japanese heart failure society. Eur J Heart Fail. (2023) 25(5):616–31. 10.1002/ejhf.2848

13.

Regan JA Kitzman DW Leifer ES Kraus WE Fleg JL Forman DE et al Impact of age on comorbidities and outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2019) 7(12):1056–65. 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.09.004

14.

Bauters C Fertin M Pinet F . B-type natriuretic peptide for the prediction of left ventricular remodelling. Cardiovasc J Afr. (2014) 25(1):33–9.

15.

Hall C . Essential biochemistry and physiology of (NT-pro)BNP. Eur J Heart Fail. (2004) 6(3):257–60. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.12.015

16.

Ritchie RH Rosenkranz AC Kaye DM . B-type natriuretic peptide: endogenous regulator of myocardial structure, biomarker and therapeutic target. Curr Mol Med. (2009) 9(7):814–25. 10.2174/156652409789105499

17.

Sarzani R Allevi M Di Pentima C Schiavi P Spannella F Giulietti F . Role of cardiac natriuretic peptides in heart structure and function. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(22):14415. 10.3390/ijms232214415

18.

Sangaralingham SJ Kuhn M Cannone V Chen HH Burnett JC . Natriuretic peptide pathways in heart failure: further therapeutic possibilities. Cardiovasc Res. (2022) 118(18):3416–33. 10.1093/cvr/cvac125

19.

Hsu J-T Chung C-M Chu C-M Lin Y-S Pan K-L Chang J-J et al Predictors of left ventricle remodeling: combined plasma B-type natriuretic peptide decreasing ratio and peak creatine kinase-MB. Int J Med Sci. (2017) 14(1):75–85. 10.7150/ijms.17145

20.

Orn S Manhenke C Squire IB Ng L Anand I Dickstein K . Plasma MMP-2, MMP-9 and N-BNP in long-term survivors following complicated myocardial infarction: relation to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging measures of left ventricular structure and function. J Card Fail. (2007) 13(10):843–9. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.07.006

21.

Khan MS Felker GM Piña IL Camacho A Bapat D Ibrahim NE et al Reverse cardiac remodeling following initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure with and without diabetes. JACC Heart Fail. (2021) 9(2):137–45. 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.09.014

22.

Januzzi JL Jr Prescott MF Butler J Felker GM Maisel AS McCague K et al Association of change in N-terminal Pro–B-type natriuretic peptide following initiation of sacubitril-valsartan treatment with cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA. (2019) 322(11):1085–95. 10.1001/jama.2019.12821

23.

Pezzuto B Piepoli M Galotta A Sciomer S Zaffalon D Filomena D et al The importance of re-evaluating the risk score in heart failure patients: an analysis from the metabolic exercise cardiac kidney indexes (MECKI) score database. Int J Cardiol. (2023) 376:90–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.01.069

24.

Agostoni P Pluchinotta FR Salvioni E Mapelli M Galotta A Bonomi A et al Heart failure patients with improved ejection fraction: insights from the MECKI score database. Eur J Heart Fail. (2023) 25(11):1976–84. 10.1002/ejhf.3031

25.

Agostoni P Chiesa M Salvioni E Emdin M Piepoli M Sinagra G et al The chronic heart failure evolutions: different fates and routes. ESC Heart Fail. (2025) 12(1):418–33. 10.1002/ehf2.14966

26.

Goetze JP Bruneau BG Ramos HR Ogawa T de Bold MK de Bold AJ . Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2020) 17(11):698–717. 10.1038/s41569-020-0381-0

Summary

Keywords

BNP, HFrEF, LVEF, remodeling, longitudinal

Citation

Romero E, Kushnir Y, Shahzad A, Patel DJ, Heejung B, Sirish P, Chiamvimonvat N, Liem DA and Cadeiras M (2026) B-type natriuretic peptide changes and left ventricular remodeling dynamics in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1666067. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1666067

Received

15 July 2025

Revised

05 November 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

08 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Massimiliano Camilli, Agostino Gemelli University Polyclinic (IRCCS), Italy

Reviewed by

Massimo Mapelli, Monzino Cardiology Center (IRCCS), Italy

Lama A. Ammar, Mount Sinai Health System, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Romero, Kushnir, Shahzad, Patel, Heejung, Sirish, Chiamvimonvat, Liem and Cadeiras.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Martin Cadeiras mcadeiras@ucdavis.edu Erick Romero eromero@sbhny.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.