Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and the risk of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients with femoral fracture, and to evaluate the potential influence of other risk factors, including age, gender, smoking status, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and multiple fractures of the lower extremities.

Methods:

A retrospective study was conducted on 1,083 patients with femoral fractures treated at Meizhou People's Hospital between November 2017 and April 2024. DVT was diagnosed using Doppler ultrasound. Data on clinical features, including age, gender, body mass index, history of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and multiple fractures of the lower extremities, were collected. Routine blood tests were performed at admission to calculate inflammatory indices, including PLR, NLR, and others. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent association of these factors with DVT.

Results:

Among the 1,083 patients, 218 (20.1%) developed DVT. Logistic regression analysis identified that PLR (OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.16–2.62, P = 0.008), age (OR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.21–3.30, P = 0.007), NLR (OR = 2.08, 95% CI:1.24–3.48, P = 0.005), gender (OR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.17–2.49=, P = 0.005), history of smoking (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.00–4.77, P = 0.05), and multiple fractures of the lower extremities (OR = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.32–3.11, P = 0.001) were independent risk factors for DVT.

Conclusions:

PLR is an independent risk factor for lower extremity DVT in patients with femoral fracture, with a modest predictive performance (AUC = 0.60) that slightly outperforms age and NLR in this cohort. While these findings suggest PLR may have potential as a supplementary biomarker for DVT risk stratification, its clinical utility requires further validation in larger, multicenter studies.

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a significant global health concern, with an annual incidence of 1–2 cases per 1,000 individuals and a high risk of life-threatening complications such as pulmonary embolism (1, 2). Despite advances in prophylaxis, DVT remains prevalent in high-risk populations, particularly patients with femoral fractures, where prolonged immobilization and systemic inflammation exacerbate thrombotic risk (3, 4). The pathogenesis of DVT is driven by Virchow's triad—venous stasis, hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury (5). Traditional risk factors include age, obesity, and diabetes (6, 7). Recent research has highlighted the potential of immune-inflammatory markers, including the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), as predictors of thrombotic risk (8, 9).

Among these biomarkers, PLR has emerged as particularly promising due to its unique ability to reflect both thrombotic (platelets) and inflammatory (lymphocytes) pathways (10, 11). Supporting this rationale, Çiçek et al. (12) recently demonstrated the diagnostic value of platelet-based ratios in acute limb embolism, reinforcing the biological plausibility of such indices in thromboembolic conditions. While NLR and SII have been extensively studied in other contexts (13, 14), PLR offers distinct advantages for DVT prediction in femoral fracture patients, including superior clinical performance (higher sensitivity and specificity) in preliminary studies (15, 16) and practical utility as it can be derived from routine complete blood counts (17).

This study specifically evaluates PLR as a predictor of preoperative DVT in femoral fracture patients, addressing a critical gap in the current literature (18, 19). By validating PLR's predictive value in this high-risk population, we aim to provide clinicians with a reliable, cost-effective tool for early DVT risk assessment. The findings could significantly impact clinical practice by improving risk stratification and guiding prophylactic strategies for this vulnerable patient group (20, 21).

Methods

Patients

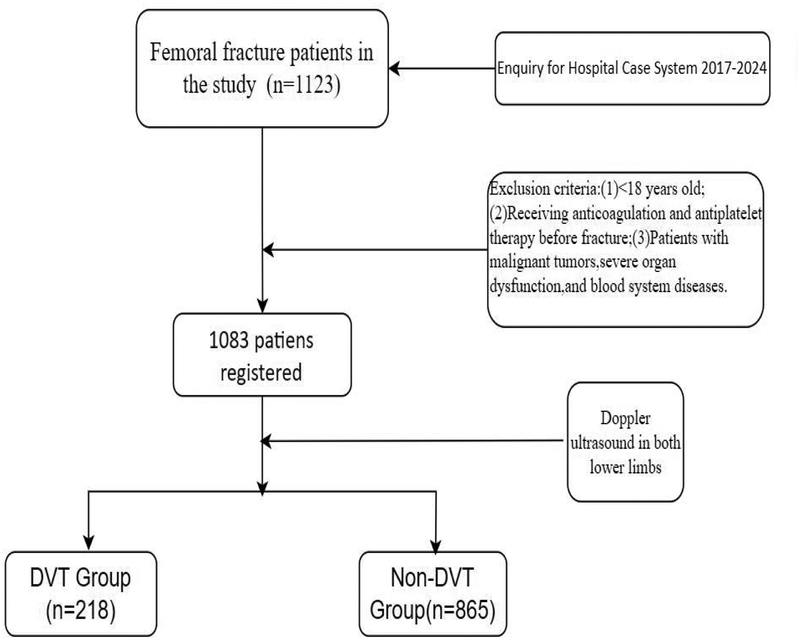

A total of 1,083 patients with femoral fractures receiving treatment at Meizhou People's Hospital were selected between November 2017 and April 2024. Vein thrombosis was diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound of both lower limbs. This standardized approach ensured universal screening regardless of clinical suspicion, minimizing selection bias. Ultrasound examinations were performed by trained vascular specialists within 48 h of admission, following a predefined institutional protocol mandating Doppler screening for all traumatic lower limb fracture patients. This protocol aligns with recent guidelines emphasizing early DVT detection in high-risk orthopedic populations (17). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) fresh femur fracture; (2) patients with fractures of all parts of femur; (3) patients ≥18 years; and (4) no pre-existing limb, motor, and sensory dysfunction prior to fracture. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients <18 years; (2) patients receiving anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy prior to fracture; and (3) patients with malignant tumors, severe organ dysfunction, or blood system diseases. This study was supported by the Ethics Committee of the Meizhou People's Hospital (2022-C-116) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The workflow of patients in our study. DVT, deep vein thrombosis.

Data collection

Clinical features of the patients were collected from the hospital’s medical records system, including gender, age, body mass index (BMI), history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, multiple fractures of lower extremities, and lower extremity vein thrombosis. Routine blood test data were collected at admission. A routine blood routine test was also conducted, which involved collecting 2 mL of the patient's blood sample in a test tube through via venipuncture of an antecubital vein. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was used as an anticoagulant and the sample was tested using a Sysmex XE-2100 hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Japan) according to standard operating procedures (SOP).

In this study, we employed a comprehensive approach to evaluate the relationship between inflammatory and immune markers and the risk of lower extremity vein thrombosis in patients with femoral fractures. The calculation of inflammation indices was based on previously validated methods (13, 14). All blood parameters (platelet, neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts) were measured in ×10⁹/L, as per standardized clinical laboratory protocols. In particular, we calculated the following indices using routine blood test parameters:

Systemic Immune-Inflammatory Index (SII):

SII = platelet count (×10⁹/L)×neutrophil count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)SII = platelet count (×10⁹/L) × neutrophil count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)

Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI):

SIRI = monocyte count (×10⁹/L)×neutrophil count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)SIRI = monocyte count (×10⁹/L)×neutrophil count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)

Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR):

NLR = neutrophil count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)NLR = neutrophil count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)

Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR):

PLR = platelet count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)PLR = platelet count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)

Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR):

MLR = monocyte count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)MLR = monocyte count (×10⁹/L)/lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L)

Systemic Immune-Inflammatory Index (SII): This index is a composite marker reflecting the interaction between platelets and leukocytes. It is calculated as SII = platelet × neutrophil/lymphocyte. The SII has been widely used to assess the inflammatory status in various diseases, including cancer and cardiovascular disorders (13).

Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI): This index incorporates monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes to reflect the overall inflammatory response. It is calculated as SIRI = monocyte × neutrophil/lymphocyte. SIRI has been shown to be a reliable marker for predicting disease severity and prognosis (13).

Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR): This ratio reflects the balance between pro-inflammatory neutrophils and anti-inflammatory lymphocytes. It is calculated as

NLR = neutrophil/lymphocyte. NLR has been extensively studied in various inflammatory and thrombotic conditions (15).

Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR): This ratio indicates the interaction between platelets and lymphocytes, which is crucial for understanding the thrombotic risk. It is calculated as PLR = platelet/lymphocyte. Elevated PLR has been associated with increased thrombotic events in several studies (10).

Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR): This ratio reflects the relative abundance of monocytes and lymphocytes, which may influence the inflammatory cascade. It is calculated as MLR = monocyte/lymphocyte. MLR has been reported to be a potential marker for inflammation and thrombosis (16).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Logistic regression analysis was employed to evaluate the independent association between inflammatory markers and the risk of vein thrombosis, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical features of patients with femoral fracture

Among the 1,083 patients with femoral fracture included in this study, 516 (47.6%) were male and 567 (52.4%) were female. The age distribution was as follows: 112 (10.3%) were <45 years, 166 (15.3%) were 45–59 years, and 805 (74.3%) were >59 years. Regarding BMI, 154 patients (14.8%) had a BMI <18.5 kg/m2, 560 (53.6%) had a BMI of 18.5–23.9 kg/m2, and 330 (31.6%) had a BMI ≥24.0 kg/m2. In addition, 62 patients (5.7%) had a history of smoking, 14 (1.3%) had a history of alcohol consumption, 294 (27.1%) had hypertension, and 162 (15.0%) had diabetes mellitus. Multiple fractures of the lower extremities were present in 215 (19.9%) patients, and 218 (20.1%) patients had vein thrombosis of the lower extremity. The mean levels of SII, SIRI, NLR, PLR, and MLR were 1,153.3 (IQR 774.8–1,772.8), 3.9 (IQR 2.2–6.6), 5.8 (IQR 3.9–8.9), 186.2 ± 111.8, and 0.5 (IQR 0.4–0.8), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variables | Total (n = 1,083) | Non-DVT (n = 865) | DVT (n = 218) | p | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.035 | 4.4 | |||

| Male, n (%) | 516 (47.6) | 426 (49.2) | 90 (41.3) | ||

| Female, n (%) | 567 (52.4) | 439 (50.8) | 128 (58.7) | ||

| BMI, n (%) | 0.138 | 4.0 | |||

| <18.5, n (%) | 154 (14.8) | 123 (14.2) | 31 (17.3) | ||

| 18.5–23.9, n (%) | 560 (53.6) | 476 (55) | 84 (46.9) | ||

| ≥24.0, n (%) | 330 (31.6) | 266 (30.8) | 64 (35.8) | ||

| Age, n (%) | <0.001 | 15.6 | |||

| <45, n (%) | 112 (10.3) | 100 (11.6) | 12 (5.5) | ||

| 45–59 | 153 (14.1) | 134 (15.5) | 19 (8.7) | ||

| >59, n (%) | 818 (75.5) | 631 (72.9) | 187 (85.8) | ||

| MLR, median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | <0.001 | 11.5 |

| PLR, mean ± SD | 186.2 ± 111.8 | 175.2 ± 86.7 | 229.9 ± 173.3 | <0.001 | 43.3 |

| NLR, median (IQR) | 5.8 (3.9, 8.9) | 5.7 (3.7, 8.4) | 6.5 (4.5, 11.1) | <0.001 | 18.6 |

| SIRI, median (IQR) | 3.9 (2.2, 6.6) | 3.7 (2.2, 6.4) | 4.3 (2.4, 7.8) | 0.005 | 8.0 |

| SII, median (IQR) | 1,153.3 (774.8, 1,772.8) | 1,114.2 (748.3, 1,658.7) | 1,347.7 (855.6, 2,343.1) | <0.001 | 17.3 |

| Multiple fractures of lower extremities | 0.142 | 2.2 | |||

| No, n (%) | 868 (80.1) | 701 (81) | 167 (76.6) | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 215 (19.9) | 164 (19) | 51 (23.4) | ||

| History of alcohol consumption | 0.498 | Fisher | |||

| No, n (%) | 1,069 (98.7) | 855 (98.8) | 214 (98.2) | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 14 (1.3) | 10 (1.2) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| History of smoking | 0.251 | 1.3 | |||

| No, n (%) | 1,021 (94.3) | 819 (94.7) | 202 (92.7) | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 62 (5.7) | 46 (5.3) | 16 (7.3) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.611 | 0.3 | |||

| No, n (%) | 921 (85.0) | 738 (85.3) | 183 (83.9) | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 162 (15.0) | 127 (14.7) | 35 (16.1) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.002 | 9.2 | |||

| No, n (%) | 789 (72.9) | 648 (74.9) | 141 (64.7) | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 294 (27.1) | 217 (25.1) | 77 (35.3) |

Clinical and demographic characteristics of femoral fracture patients with and without DVT.

BMI, body mass index; SII, systemic immune-inflammatory index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio. IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to measure the relationship between the associated factors and vein thrombosis of the lower extremity. The results of univariate analysis showed that gender, age, hypertension, SII, SIRI l, NLR, PLR, and MLR were significantly associated with vein thrombosis of the lower extremity. Multivariate regression logistic analysis identified that gender (OR =1.71,95% CI:1.171–2.49, P = 0.005), age (OR = 2.0,95% CI:1.21–3.30, P = 0.007), history of smoking (OR = 2.19, 95% CI:1.01–4.77, P = 0.048), multiple fractures of lower extremities (OR = 2.02,95% CI: 1.32–3.11, P = 0.001), NLR (OR = 2.08, 95% CI:1.24–3.48,P = 0.005), and PLR (OR = 1.74, 95% CI:1.16–2.62,P = 0.008) were independent risk factors for vein thrombosis of the lower extremity after femoral fracture (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p values | OR (95% CI) | p values | |

| Gender (female/male) | 1.380 (1.022–1.864) | 0.036 | 1.706 (1.171–2.486) | 0.005 |

| Age (≥60/<60, years old) | 2.126 (1.433–3.155) | <0.001 | 1.997 (1.209–3.299) | 0.007 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| 18.5–23.9 | 1.000 (reference) | – | 1.000 (reference) | – |

| <18.5 | 1.372 (0.866–2.176) | 0.178 | 1.213 (0.750–1.961) | 0.432 |

| ≥24.0 | 1.337 (0.935–1.913) | 0.112 | 1.456 (0.989–2.142) | 0.057 |

| History of smoking (yes/no) | 1.410 (0.782–2.542) | 0.253 | 2.191 (1.006–4.774) | 0.048 |

| History of alcoholism (yes/no) | 1.598 (0.496–5.145) | 0.432 | 1.061 (0.230–4.893) | 0.940 |

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 1.631 (1.187–2.240) | 0.003 | 1.462 (0.996–2.145) | 0.052 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes/no) | 1.111 (0.739–1.671) | 0.612 | 1.073 (0.671–1.716) | 0.768 |

| Multiple fractures of lower extremities (yes/no) | 1.305 (0.914–1.865) | 0.143 | 2.022 (1.316–3.107) | 0.001 |

| SII (≥1,294.2/<1,294.2) | 1.797 (1.333–2.424) | <0.001 | 0.870 (0.553–1.368) | 0.546 |

| SIRI (≥3.655/<3.655) | 1.571 (1.159–2.130) | 0.004 | 0.774 (0.468–1.278) | 0.317 |

| NLR (≥3.995/<3.995) | 2.305 (1.547–3.432) | <0.001 | 2.082 (1.244–3.485) | 0.005 |

| PLR (≥197.95/<197.95) | 2.063 (1.526–2.791) | <0.001 | 1.741 (1.157–2.621) | 0.008 |

| MLR (≥0.695/<0.695) | 1.880 (1.383–2.555) | <0.001 | 1.513 (0.948–2.415) | 0.082 |

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for lower extremity DVT.

BMI, body mass index; SII, systemic immune-inflammatory index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

ROC analysis indicated that PLR (AUC=0.60) and NLR (AUC=0.59) had comparable predictive performance (P = 0.714), with PLR offering higher sensitivity (69%) and NLR higher specificity (85%) at their optimal cutoffs.

The predictive performance of age, NLR, and PLR for lower extremity DVT was evaluated using ROC curve analysis, with results detailed in Table 3. The AUC values were 0.59 (95% CI: 0.56–0.62) for age, 0.58 (95% CI: 0.55–0.64) for NLR, and 0.60 (95% CI: 0.56–0.65) for PLR. Optimal cutoff values were identified as 79.5 years for age, 3.99 for NLR, and 198 for PLR, corresponding to sensitivity/specificity of 67%/48% for age, 29%/85% for NLR, and 69%/49% for PLR. All variables demonstrated statistically significant P-values <0.001.

Table 3

| Variables | AUC | 95% CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cutoff | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.58 | 0.60–0.66 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 79.5 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 0.59 | 0.55–0.64 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| PLR | 0.60 | 0.56–0.65 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 198.0 | <0.001 |

The predictive ability of Age, NLR, and PLR for lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Discussion

DVT, a disorder of venous return in the lower extremities, is a common complication in patients with lower extremity fractures after surgery. Pathologically, blood abnormally agglutinates and blocks vein lumen in deep veins under conditions of vascular wall injury and blood hypercoagulability. Clinically, diagnosis of vein thrombosis is challenging, as patients often present with local pain and edema, leading to the condition often being overlooked. Notably, thrombus shedding can lead to pulmonary embolism, a severe life-threatening development (22).

In line with previous studies, in this study, gender, age, history of smoking, and multiple fractures of lower extremities were independent risk factors for vein thrombosis of lower extremities in patients with femoral fractures. Consistent with our findings, Zhang et al. found that age >50 years, female sex, and cigarette smoking were independent risk factors for vein thrombosis in patients with traumatic fractures (18). Extending the evidence base, there have been several studies reported on risk factors for lower extremity vein thrombosis in patients with lower extremity fractures. Similarly, Chang et al. revealed that advanced age and diabetes mellitus were independent risk factors for lower extremity fractures complicated by deep vein thrombosis (19). Contrastingly, Zuo et al. found that obesity (BMI ≥ 24.0 kg/m2) was an independent factor for vein thrombosis of lower extremities after intertrochanteric fracture (15). Interestingly, male sex was a risk factor for vein thrombosis in ankle fractures (20) and tibial plateau fractures (11). Conversely, female sex was a risk factor for vein thrombosis in patients with traumatic fractures (18). In addition, obesity was associated with vein thrombosis in foot fractures (14). Supporting this, Chang et al. found that diabetes mellitus was a potential risk factor for vein thrombosis in patients with lower extremity fractures (19). Notably, diabetes mellitus was an independent risk factor for vein thrombosis in patients with femoral neck fractures (13). Collectively, some studies found that advanced age was found to be a risk factor for vein thrombosis in patients with lower extremity fractures (12, 19, 23–25). In particular, age ≥65 years was identified as a risk factor of vein thrombosis in closed patella fractures (26). Similarly, age ≥65 years was identified as a risk factor of vein thrombosis in lower extremities after hip fractures (27). Moreover, age ≥40 years was a risk factor of vein thrombosis in patients with tibial fractures (28). Importantly, patients with multiple injuries have a higher risk of deep vein thrombosis (29, 30). The results of those studies are consistent with the findings of the present study. Furthermore, Ma et al. found that alcohol consumption was associated with vein thrombosis in foot fractures (14). Hypertension was a risk factor for vein thrombosis of lower extremities in tibial plateau fractures. However, this study did not reach similar conclusions.

Mechanistically, in this study, high PLR (≥198), and high NLR (≥4.0) were identified as independent risk factors for vein thrombosis of lower extremities in patients with femoral fractures. Contextually, there are relatively few studies analyzing the relationship between inflammation and immune indexes and venous thrombosis after lower limb fractures. Fundamentally, neutrophil extracellular traps released by neutrophils are involved in the formation of vein thrombosis in patients with traumatic fractures (31). Luo et al. found that reduced lymphocyte count was independently associated with vein thrombosis in patients with ankle fractures (32). Contrastingly, Liu et al. revealed that the occurrence of vein thrombosis after tibial plateau fractures was independently related to the levels of platelets and neutrophils, but not NLR, PLR, MLR, and SII (13). Supporting our findings, Zeng et al. found that high NLR and SII were independent predictors of vein thrombosis among patients with intertrochanteric femoral fractures (33). In addition, high SII was a predictor of vein thrombosis in elderly patients with hip fractures (34).

Beyond cellular markers, Luo et al. identified that lower albumin levels, reduced lymphocyte counts, and elevated D-dimer levels were associated with vein thrombosis of the lower extremities following ankle fractures. Overall, platelet distribution width (PDW), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), serum sodium concentration, and D-dimer levels were associated with vein thrombosis following foot fractures (14). Zhang et al. proposed that an innovative fibrinolysis index [calculated by lysis potential (LP), lysis time (LT), blood cell counts, conventional coagulation tests, and tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor complex (tPAIC)] could be a biomarker for predicting vein thrombosis after traumatic lower extremity fractures (35). Consistently, some studies found that there was a significant difference in D-dimer levels between thrombus patients and non-thrombus patients after lower limb fractures (18, 25, 36, 37). Extending these findings, Zhu et al. found that alkaline phosphatase, sodium concentration, and D-dimer were associated with vein thrombosis of the lower extremities following tibial plateau fractures (11). Notably, abnormal lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), low serum sodium concentrations, and higher hematocrit levels were independently associated with vein thrombosis after hip fractures (38).

This study is one of the few to examine the relationship between levels of peripheral blood immune-inflammatory markers and the risk of vein thrombosis of lower extremities following femoral fractures. Methodologically, this study still has the following limitations: (1) This study is a single-center retrospective study, which inevitably has selection bias. The findings need to be confirmed in large, multicenter studies. (2) Given the limitations of vascular ultrasonography, the results of this study do not exclude the possibility of false positives and false negatives in the diagnosis of vein thrombosis of lower extremities. (3) As some patients did not undergo long-term follow-up after discharge, the clinical outcome of preoperative vein thrombosis was not evaluated in this study.

Building on recent advances, Çiçek et al. (12) demonstrated the diagnostic value of red blood cell distribution-to-platelet ratio (RPR) in acute leg embolism, providing a comparative context for our PLR findings. Furthermore, Songur et al. (39) established PLR's prognostic significance in arterial pathologies, suggesting its broader vascular relevance beyond venous thrombosis.

Conclusions

PLR is an independent risk factor for lower extremity DVT in patients with femoral fractures, with a modest predictive performance (AUC = 0.60) that slightly outperforms age and NLR in this cohort. Although these findings suggest that PLR may have potential as a supplementary biomarker for DVT risk stratification, its clinical utility requires further validation in larger, multicenter studies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Meizhou People's Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

KL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Project of Medical and Health Scientific Research of Meizhou City (Grant No.: 2023-B-25).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the colleagues of the Department of Traumatic Orthopedics, Meizhou People's Hospital, who were not listed in the authorship, for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Paydar S Sabetian G Khalili H Fallahi J Tahami M Ziaian B et al Management of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis in trauma patients. Bull Emerg Trauma. (2016) 4:1–7. 10.7508/beat-2016-0001

2.

Bhatt M Braun C Patel P Patel P Begum H Wiercioch W et al Diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:1250–64. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000960

3.

Chen K Liu Z Li Y Zhao X Zhang S Liu C et al Diagnosis and treatment strategies for intraoperative pulmonary embolism caused by renal tumor thrombus shedding. J Card Surg. (2022) 37:3973–83. 10.1111/jocs.16874

4.

Lee SH Kim HK Hwang JK Kim SD Park SC Kim JI et al Efficacy of retrievable inferior vena cava filter placement in the prevention of pulmonary embolism during catheter-directed thrombectomy for proximal lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg. (2016) 33:181–6. 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.10.034

5.

Saragas NP Ferrao PN Jacobson BF Saragas E Strydom A . The benefit of pharmacological venous thromboprophylaxis in foot and ankle surgery. S Afr Med J. (2017) 107:327–30. 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i4.10843

6.

Tang Y Wang K Shi Z Yang P Dang X Li H et al A RCT study of rivaroxaban, low-molecular-weight heparin, and sequential medication regimens for the prevention of venous thrombosis after internal fixation of hip fracture. Biomed Pharmacother. (2017) 92:982–8. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.107

7.

Trivedi NN Sivasundaram L Wang C Kim CY Buser Z Wang JC . Chemoprophylaxis for the hip fracture patient: a comparison of warfarin and low-molecular-weight heparin. J Orthop Trauma. (2019) 33:216–9. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001435

8.

Vazquez-Garza E Jerjes-Sanchez C . Venous thromboembolism: thrombosis, inflammation, and immunothrombosis for clinicians. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2017) 44:377–85. 10.1007/s11239-017-1528-7

9.

Saraiva SS Custódio IF Mazetto BM Collela MP de Paula EV Annichino-Bizzachi JM et al Recurrent thrombosis in antiphospholipid syndrome may be associated with cardiovascular risk factors and inflammatory response. Thromb Res. (2015) 136:1174–8. 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.10.029

10.

Yang W Liu Y . Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a novel marker in venous thromboembolism: a retrospective study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2019) 25:1076029619832805. 10.1177/1076029619832805

11.

Li S Ma H Zhang Y Wang X Liu J Chen Y . Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as predictors of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:703044. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.703044

12.

Çiçek ÖF Atalay A Çelik R Özdil M Boncuk F Ünlü A et al Assessing the diagnostic value of the red blood cell distribution-to-platelet ratio in acute leg embolism requiring emergent surgical intervention. Genel Tıp Derg. (2023) 33(5):608–13. 10.54005/geneltip.1354789

13.

Liu D Zhu Y Chen W Li J Zhao K Zhang J et al Relationship between the inflammation/immune indexes and deep venous thrombosis (DVT) incidence rate following tibial plateau fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. (2020) 15:241. 10.1186/s13018-020-01765-9

14.

Ahmad J Lynch MK Maltenfort M . Incidence and risk factors of venous thromboembolism after orthopaedic foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Spec. (2017) 10:449–54. 10.1177/1938640017704944

15.

Zuo J Hu Y . Admission deep venous thrombosis of lower extremity after intertrochanteric fracture in the elderly: a retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg Res. (2020) 15:549. 10.1186/s13018-020-02092-9

16.

Ren Z Yuan Y Qi W Li Y Wang P Zhang Y . The incidence and risk factors of deep venous thrombosis in lower extremities following surgically treated femoral shaft fracture: a retrospective case-control study. J Orthop Surg Res. (2021) 16:446. 10.1186/s13018-021-02595-z

17.

Xiang G Dong X Lin S Cai L Zhou F Luo P et al A nomogram for prediction of deep venous thrombosis risk in elderly femoral intertrochanteric fracture patients: a dual-center retrospective study. Front Surg. (2022) 9:1028859. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1028859.2022.1028859

18.

Zhang L Liu X Pang P Luo Z Cai W Li W et al Incidence and risk factors of admission deep vein thrombosis in patients with traumatic fracture: a multicenter retrospective study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2023) 29:10760296231167143. 10.1177/10760296231167143

19.

Chang W Wang B Li Q Zhang Y Xie W Li H . Study on the risk factors of preoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients with lower extremity fracture. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2021) 27:10760296211002900. 10.1177/10760296211002900

20.

Luo Z Chen W Li Y Wang X Zhang W Zhu Y . Preoperative incidence and locations of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of lower extremity following ankle fractures. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10266. 10.1038/s41598-020-67365-z

21.

Fu YH Liu P Xu X Wang PF Shang K Ke C et al Deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremities after femoral neck fracture: a retrospective observational study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong. (2020) 28:2309499019901172. 10.1177/2309499019901172

22.

Xiao S Geng X Zhao J Fu L . Risk factors for potential pulmonary embolism in the patients with deep venous thrombosis: a retrospective study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. (2020) 46:419–24. 10.1007/s00068-018-1039-z

23.

Qu SW Cong YX Wang PF Fei C Li Z Yang K et al Deep vein thrombosis in the uninjured lower extremity: a retrospective study of 1454 patients with lower extremity fractures. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2021) 27:1076029620986862. 10.1177/1076029620986862

24.

Zhang BF Wang PF Fei C . Perioperative deep vein thrombosis in patients with lower extremity fractures: an observational study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2020) 26:1076029620930272. 10.1177/1076029620930272

25.

Zhang W Huai Y Wang W Xue K Chen L Chen C et al A retrospective cohort study on the risk factors of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) for patients with traumatic fracture at honghui hospital. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e024247. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024247

26.

Tan Z Hu H Wang Z Wang Y Zhang Y . Prevalence and risk factors of preoperative deep venous thrombosis in closed patella fracture: a prospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg Res. (2021) 16:404. 10.1186/s13018-021-02558-4

27.

Zhang BF Wei X Huang H Wang PF Liu P Qu SW et al Deep vein thrombosis in bilateral lower extremities after hip fracture: a retrospective study of 463 patients. Clin Interv Aging. (2018) 13:681–9. 10.2147/CIA.S161191

28.

Cai X Wang Z Wang XL Xue HZ Li ZJ Jiang WQ . Correlation between the fracture line plane and perioperative deep vein thrombosis in patients with tibial fracture. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2021) 27:10760296211067258. 10.1177/10760296211067258

29.

Shi D Bao B Zheng X Wei H Zhu T Zhang Y . Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in patients with pelvic or lower-extremity fractures in the emergency intensive care unit. Front Surg. (2023) 10:1115920. 10.3389/fsurg.2023.1115920

30.

Zhu Y Meng H Ma J Zhang J Li J Zhao K et al Prevalence of preoperative lower extremity deep vein thrombosis in bilateral calcaneal fractures. J Foot Ankle Surg. (2021) 60:950–5. 10.1053/j.jfas.2021.04.002

31.

Liu L Zhang W Su Y Chen Y Cao X Wu J . The impact of neutrophil extracellular traps on deep venous thrombosis in patients with traumatic fractures. Clin Chim Acta. (2021) 519:231–8. 10.1016/j.cca.2021.04.021

32.

Luo Z Chen W Li Y Wang X Zhang W Zhu Y . Incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremity in patients undergoing surgeries for ankle fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. (2020) 15:294. 10.1186/s13018-020-01809-0

33.

Zeng G Li X Li W Wen Z Wang S Zheng S et al A nomogram model based on the combination of the systemic immune-inflammation index, body mass index, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio to predict the risk of preoperative deep venous thrombosis in elderly patients with intertrochanteric femoral fracture: a retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg Res. (2023) 18:561. 10.1186/s13018-023-03966-4

34.

Chen X Fan Y Tu H Chen J Li R . A nomogram model based on the systemic immune-inflammation index to predict the risk of venous thromboembolism in elderly patients after hip fracture: a retrospective cohort study. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e28389. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28389

35.

Zhang W Su Y Liu L Zhao H Wen M Zhao Y et al Fibrinolysis index as a new predictor of deep vein thrombosis after traumatic lower extremity fractures. Clin Chim Acta. (2020) 511:227–34. 10.1016/j.cca.2020.10.018

36.

Chen H Sun L Kong X . Risk assessment scales to predict risk of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis among multiple trauma patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. (2023) 23:144. 10.1186/s12873-023-00914-7

37.

Zhao X Ali SJ Sang X . Clinical study on the screening of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis by D-dimer combined with RAPT score among orthopedic trauma patients. Indian J Orthop. (2020) 54(Suppl 2):316–21. 10.1007/s43465-020-00268-3

38.

Ding K Wang H Jia Y Zhao Y Yang W Chen W et al Incidence and risk factors associated with preoperative deep venous thrombosis in the young and middle-aged patients after hip fracture. J Orthop Surg Res. (2022) 17:15. 10.1186/s13018-021-02902-8

39.

Songur M Simsek E Faruk O Kavasoğlu K Alagha S Karahan M . The platelet-lymphocyte ratio predict the risk of amputation in critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Med Surg. (2014) 2:1–4. 10.4172/2329-6925.1000158

Summary

Keywords

femoral fracture, vein thrombosis, lower extremity, inflammation and immune indexes platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

Citation

Li K, Li D and Sun J (2026) Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of preoperative venous thrombosis in femoral fracture patients: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1672545. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1672545

Received

24 July 2025

Revised

17 November 2025

Accepted

12 December 2025

Published

20 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Rodrigo Assar, University of Chile, Chile

Reviewed by

Ömer Faruk Çiçek, Selcuk University, Türkiye

Guowei Zeng, First People’s Hospital of Huizhou City, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Li, Li and Sun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Jianguang Sun sun830616@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.