Abstract

Background:

The association of stent length and number with the risk of in-stent restenosis (ISR) following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) has been widely reported, yet findings remain inconsistent across studies. To clarify this relationship, we conducted a meta-analysis of observational studies evaluating the impact of stent length and number on ISR risk after PCI in CAD patients.

Methods:

Case-control studies addressing stent length, stent number, and ISR after PCI in CAD patients were systematically searched in electronic databases including VIP, Wanfang, CNKI, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, PubMed, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library from inception until June 2025. The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used to assess study quality. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random-effects model. All analyses were performed with Review Manager version 5.4.

Results:

Eighteen studies involving 6,585 participants were included. Meta-analyses indicated that both stent length [OR = 1.05, 95% CI (1.04, 1.07), P < 0.00001] and stent number [OR = 3.01, 95% CI (1.97, 4.59), P < 0.00001] were significant risk factors for ISR after PCI in CAD patients.

Conclusion:

This meta-analysis supports the conclusion that stent length and number are associated with an increased risk of ISR after PCI in CAD patients. However, given the limited number and moderate quality of the included studies, these findings should be interpreted with caution and validated by further high-quality research.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) has become one of the leading causes of death worldwide (1–3). Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a key treatment for CAD, enables rapid vascular reperfusion by dilating the coronary lumen, preserves myocardial tissue, and significantly reduces patient mortality (4). However, PCI is often associated with various complications, among which in-stent restenosis (ISR) accounts for approximately 10% of cases (5). ISR can lead to symptom recurrence and increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular events (6), adversely affecting patients’ quality of life and often necessitating repeat interventions.

Currently, drug-eluting stents (DES) and drug-coated balloons (DCB) are recommended for treating ISR (7, 8). Among available options—including plain balloon angioplasty, bare-metal stents (BMS), DES, DCB, and cutting balloons—the cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent (EES) has been shown to be the most effective strategy for ISR management (8). Nevertheless, the search for optimal ISR therapies continues. Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS), which offer a “leave-nothing-behind” approach, have attracted attention in this context. BVS provide short- to mid-term radial strength comparable to BMS and DES, while eventually being fully absorbed in the body (9). Theoretically, this allows restoration of native vessel elasticity and endothelial function, reduces late stent malapposition, and prevents very late stent thrombosis caused by incomplete endothelialization of metallic stents (10). However, some studies indicate that biodegradable scaffolds may be associated with higher rates of adverse cardiovascular events compared with BMS, particularly target vessel myocardial infarction and scaffold thrombosis (11, 12). Therefore, understanding the risk factors, mechanisms, treatment, and prevention of coronary ISR remains critically important.

The mechanism of ISR is not yet fully elucidated. Studies suggest that neointimal hyperplasia within 3–6 months after PCI is a major contributor to ISR (13). Other research indicates that the severity of ISR is closely associated with biochemical markers such as serum lipoproteins, uric acid, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, with dyslipidemia also playing a potential role (4, 14, 15). In recent years, risk factors for ISR after PCI in CAD patients have been widely investigated (16–21). However, evidence regarding the impact of stent length and number on ISR remains inconsistent and warrants further clarification. Thus, this study conducted a meta-analysis of published studies evaluating the association of stent length and number with ISR risk after PCI, aiming to provide more robust evidence for clinical decision-making.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Case-control studies investigating the association of stent length and number with ISR after PCI in patients with CAD were retrieved via computerized searches of the following databases: VIP, Wanfang, CNKI, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, PubMed, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. The search period spanned from the inception of each database to June 2025. A combination of subject headings and free-text terms was employed, with adjustments made according to the specific features of each database. References of included studies were also manually screened to identify additional relevant publications. Search keywords included: “coronary artery disease”, “in stent restenosis”, “percutaneous coronary intervention”, “risk factor”, etc. The detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

- 1.

Participant: CAD patients who underwent PCI, with the case group defined as those who developed ISR and the control group as those without ISR;

- 2.

Exposure: Stent number and/or stent length;

- 3.

Outcomes: ISR defined as ≥50% diameter stenosis on coronary angiography within the stent or within 5 mm of its proximal or distal edge, as referenced to the adjacent normal vessel segment (22);

- 4.

Study design: Case-control studies.

Exclusion criteria included:

- 1.

Case reports, reviews, or animal studies;

- 2.

Studies with incomplete data and where authors could not be contacted for additional information;

- 3.

Duplicate publications.

Data extraction

Two evaluators independently screened literature, extracted data and cross-checked the results. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consultation with a third reviewer. When necessary, corresponding authors were contacted to obtain missing data. The following information was extracted:

① Basic study characteristics: first author, publication year, country, etc.; ② baseline characteristics of the study population; ③ key elements related to risk of bias assessment; ④ outcome measures and relevant effect estimates.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the included observational studies was evaluated independently by two reviewers using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. The assessment covered seven domains: bias due to confounding, participant selection, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting. Each domain was judged as “low risk,” “moderate risk,” “high risk,”, “critical risk”, and as “no information.”

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan version 5.4 software. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the χ2 test (significance level set at α = 0.10) and quantified with the I2 statistic. An I2 < 50% and P > 0.10 indicated acceptable heterogeneity, in which case a fixed-effects model was applied; otherwise, a random-effects model was used. Given expected variations in study populations, treatment protocols, and follow-up durations, a random-effects model was preferred for its ability to account for clinical and methodological diversity and to provide more generalized estimates (23). Sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially excluding each study to test the robustness of the results. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, Begg's Test and Egger's test.

Results

Search results

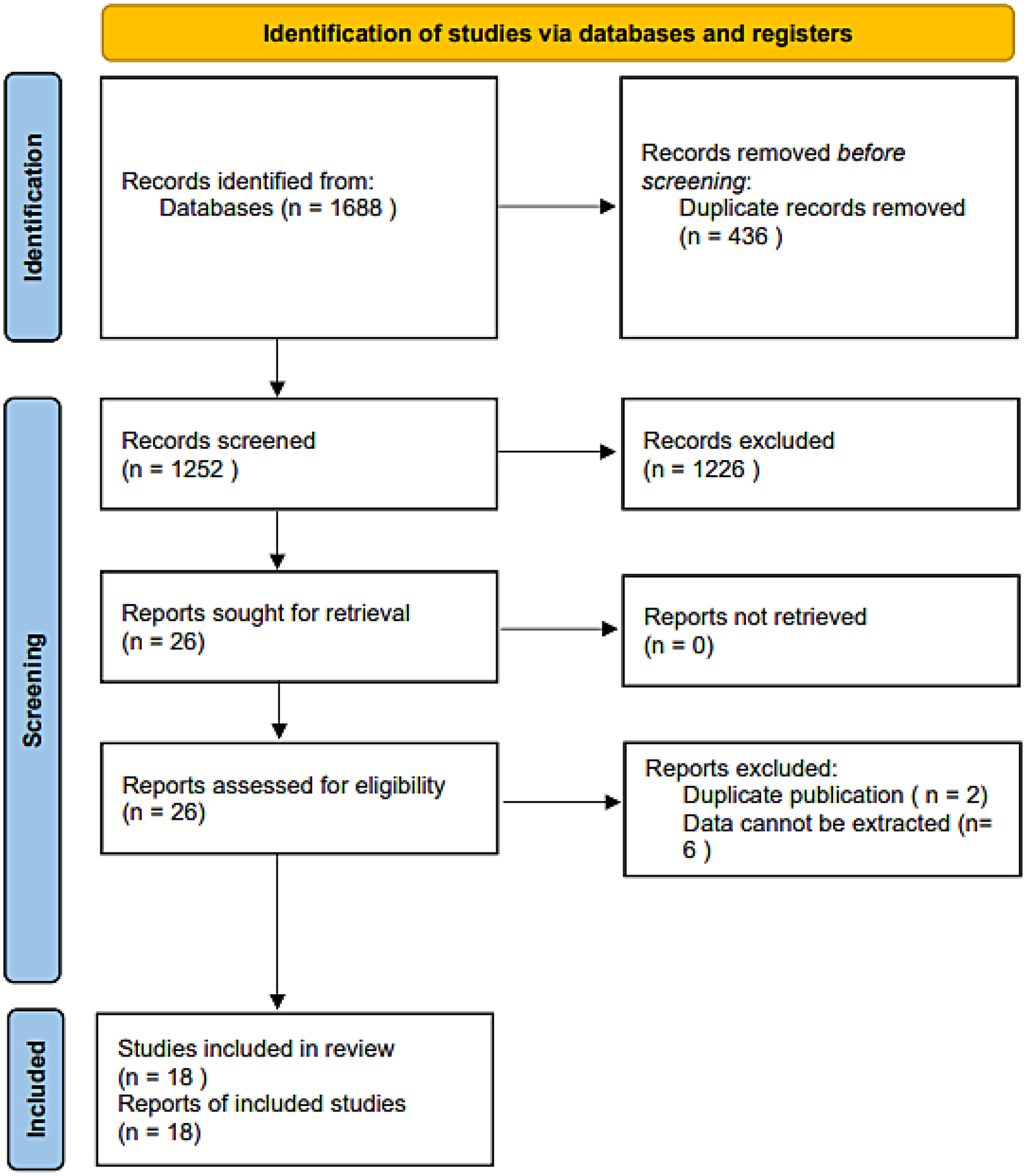

The initial database search identified 1,688 relevant records. After removing 436 duplicates, 1,226 records were excluded based on title and abstract screening. Following a full-text review of the remaining articles, eight were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria. Ultimately, 18 studies (17–19, 24–38) were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow diagram for the eligible study selection process.

Characteristics of the eligible studies

All 18 included studies (17–19, 24–38) were case-control designs, involving a total of 6,585 patients (1,431 cases with ISR and 5,154 controls). Two risk factors were examined across these studies: stent length was reported in twelve articles (17, 19, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33–35, 38), and stent number was analyzed in ten articles (17–19, 26, 28, 29, 32, 36–38). The basic characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Based on the ROBINS-I tool, the risk of bias assessment indicated that thirteen studies had a moderate risk of bias, while five studies were judged to have a low risk of bias (Table 2).

Table 1

| Study | Study design | Region | Age (Years) | Sample size (n) | Risk factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | ||||

| Li et al. (17) | Case-control study | China | 66.71 ± 9.65 | 65.63 ± 11.15 | 62 | 279 | ①② |

| Xu et al. (18) | Case-control study | China | 62.3 ± 9.1 | 60.4 ± 10.3 | 95 | 517 | ② |

| Yildiz et al. (24) | Case-control study | Turkey | 61.9 ± 11.0 | 61.3 ± 10.7 | 131 | 138 | ① |

| Zhang et al. (45) | Case-control study | China | 68.23 ± 8.67 | 69.15 ± 9.04 | 138 | 212 | ①② |

| Liu et al. (28) | Case-control study | China | — | — | 47 | 76 | ①② |

| Tang et al. (31) | Case-control study | China | 59.23 ± 11.52 | 58.94 ± 14.62 | 36 | 138 | ① |

| Zhang et al. (34) | Case-control study | China | 58.98 ± 7.89 | 59.32 ± 9.21 | 51 | 442 | ① |

| Zhang et al. (35) | Case-control study | China | 69.14 ± 8.57 | 66.35 ± 9.21 | 38 | 82 | ① |

| Zhu et al. (38) | Case-control study | China | — | — | 145 | 1,013 | ①② |

| Li et al. (27) | Case-control study | China | — | — | 90 | 110 | ① |

| Yang (33) | Case-control study | China | 60.90 ± 6.91 | 60.33 ± 9.31 | 63 | 70 | ① |

| Pan (30) | Case-control study | China | 66 ± 9 | 65 ± 10 | 258 | 262 | ① |

| Zhao and Zhang (36) | Case-control study | China | 57.31 ± 8.45 | 57.31 ± 8.45 | 45 | 200 | ② |

| Deng et al. (25) | Case-control study | China | 63.53 ± 11.81 | 62.21 ± 11.06 | 89 | 1,253 | ① |

| Zheng et al. (37) | Case-control study | China | 59.4 ± 9.4 | 59.1 ± 9.0 | 21 | 105 | ② |

| Lu et al. (29) | Case-control study | China | 60.17 ± 9.47 | 58.27 ± 10.43 | 87 | 68 | ② |

| Wei et al. (32) | Case-control study | China | 68.1 ± 16.6 | 70.1 ± 17.5 | 4 | 46 | ② |

| Li et al. (26) | Case-control study | China | 60.7 ± 11.5 | 61.9 ± 11.6 | 31 | 143 | ② |

Characteristics of the studies included in meta analysis.

①Stent length; ②Stent number.

Table 2

| Study | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. (17) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Xu et al. (18) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Yildiz et al. (24) | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Zhang et al. (45) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Liu et al. (28) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Tang et al. (31) | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Zhang et al. (34) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zhang et al. (35) | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Zhu et al. (38) | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Li et al. (27) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Yang (33) | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Pan (30) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zhao and Zhang (36) | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Deng et al. (25) | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Zheng et al. (37) | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Lu et al. (29) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wei et al. (32) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Li et al. (26) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

ROBINS-I assessment of study bias for included studies.

Domains:

D1: Bias due to confounding.

D2: Bias in selection of participants.

D3: Bias in classification of exposures.

D4: Bias due to deviations from intended exposures.

D5: Bias due to missing data.

D6: Bias in measurement of outcomes.

D7: Bias in selection of the reported result.

Meta-analysis results

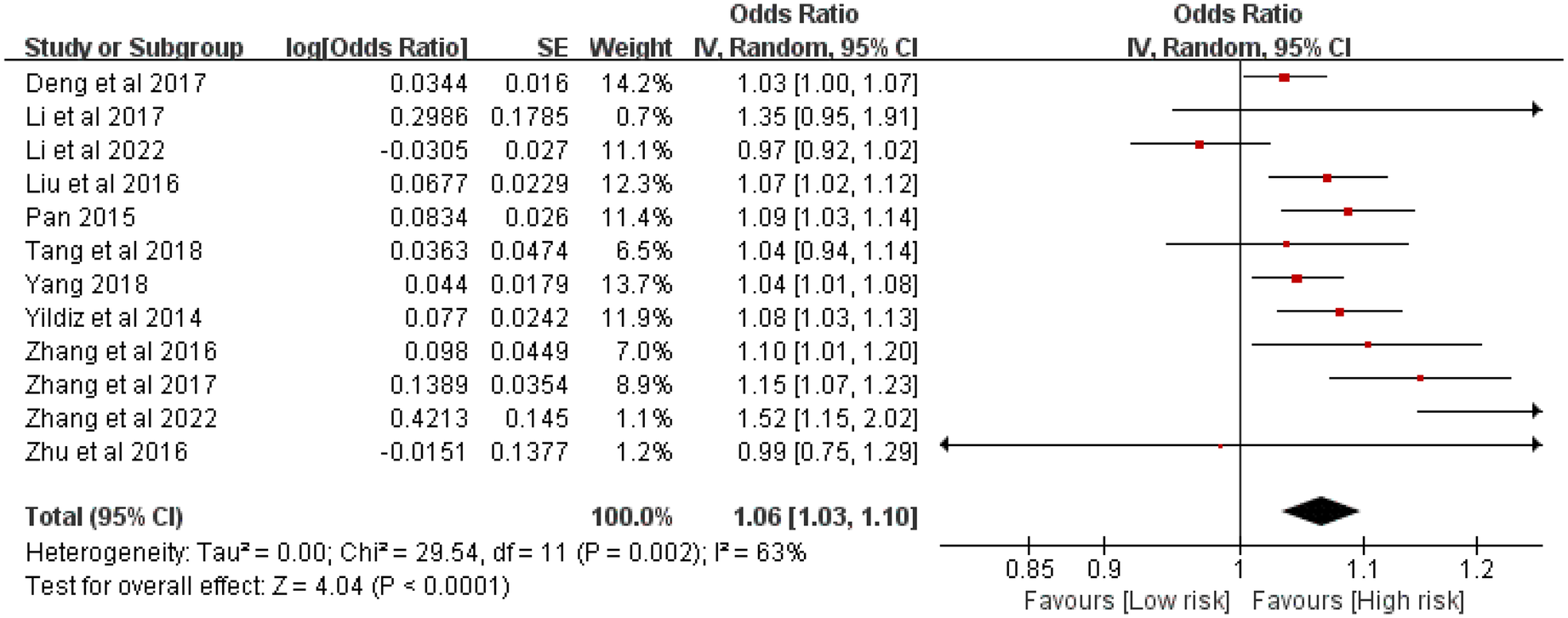

Twelve studies involving 5,223 patients evaluated the association between stent length and ISR risk after PCI in CAD patients. Heterogeneity was significant (P = 0.002, I2 = 63%). The random-effects meta-analysis showed that longer stent length was significantly associated with an increased risk of ISR [OR = 1.05, 95% CI (1.04, 1.07), P < 0.00001] (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Forest plot of the association between stent length and the risk of in stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention.

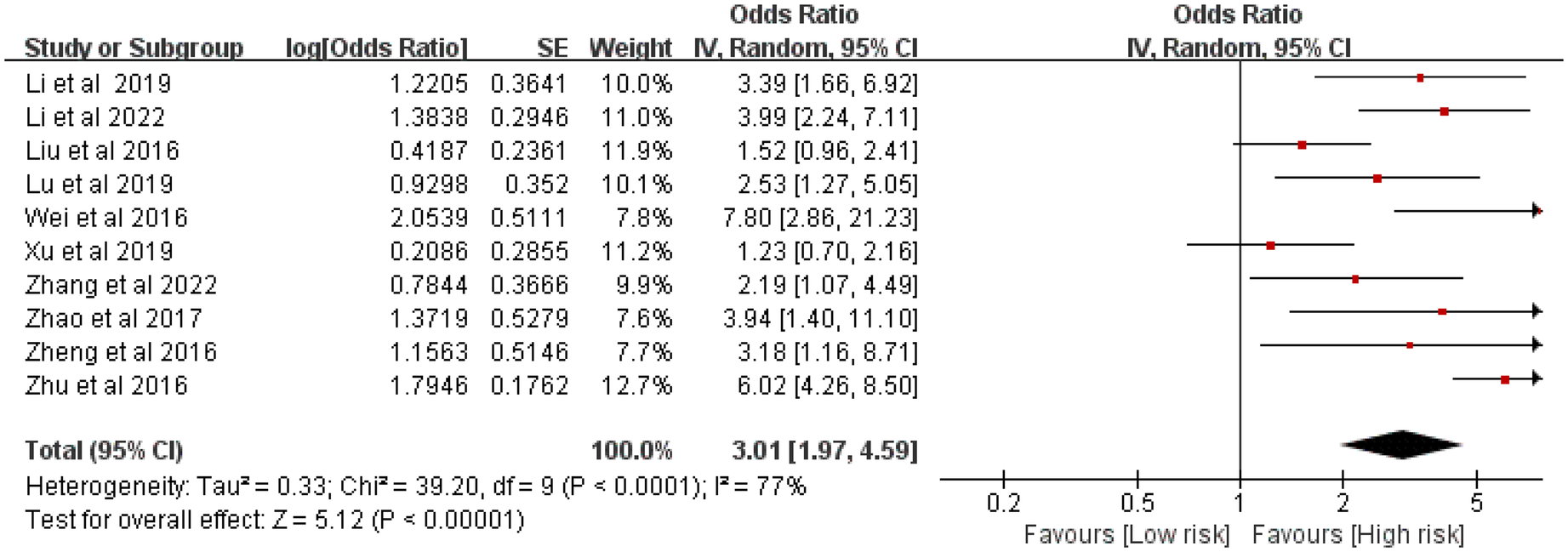

Ten studies comprising 3,334 patients examined the relationship between the number of stents and ISR risk. Considerable heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.0001, I2 = 77%). The meta-analysis indicated that a greater number of stents significantly elevated the risk of ISR [OR = 3.01, 95% CI (1.97, 4.59), P < 0.00001] (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Forest plot of the association between stent number and the risk of in stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention.

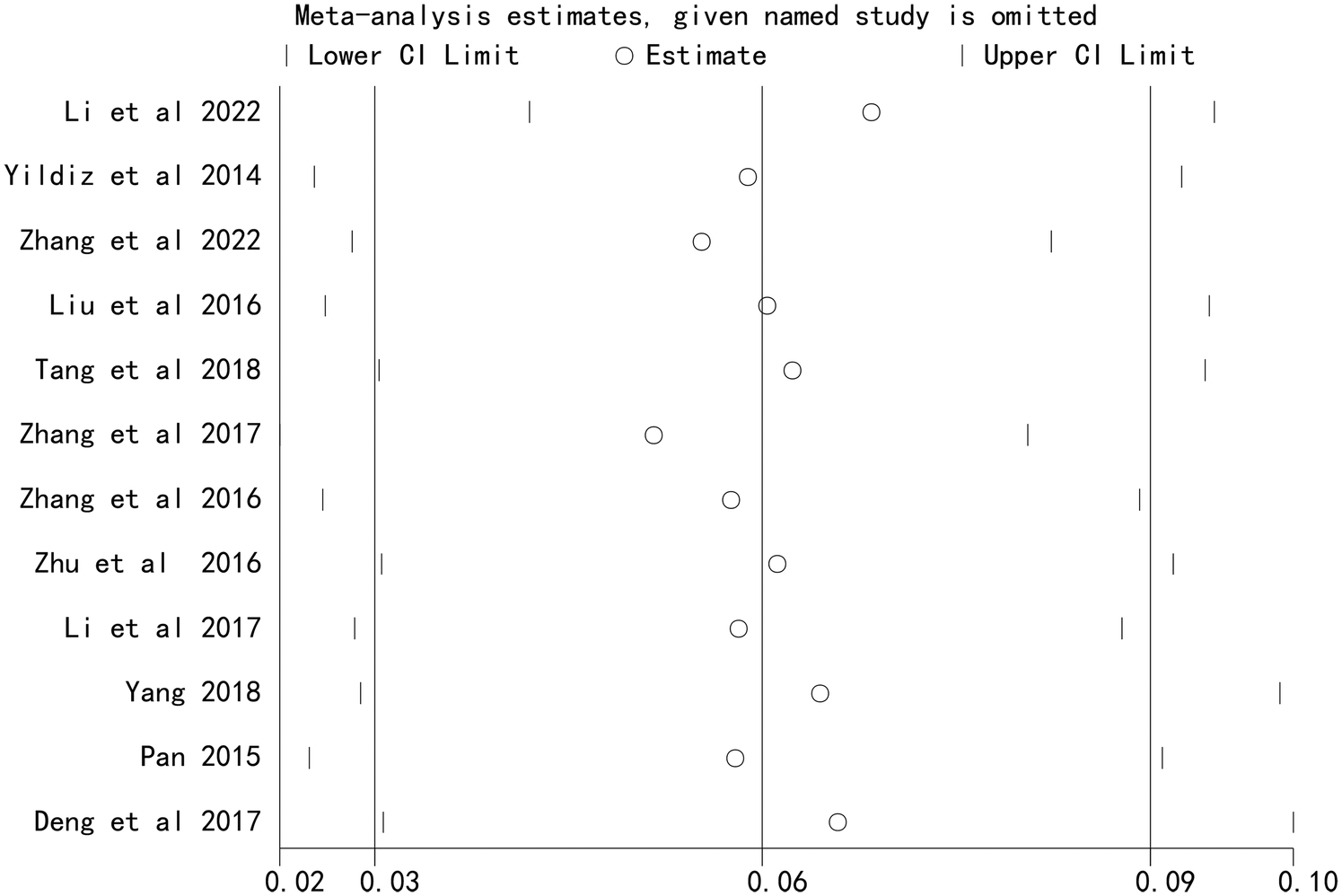

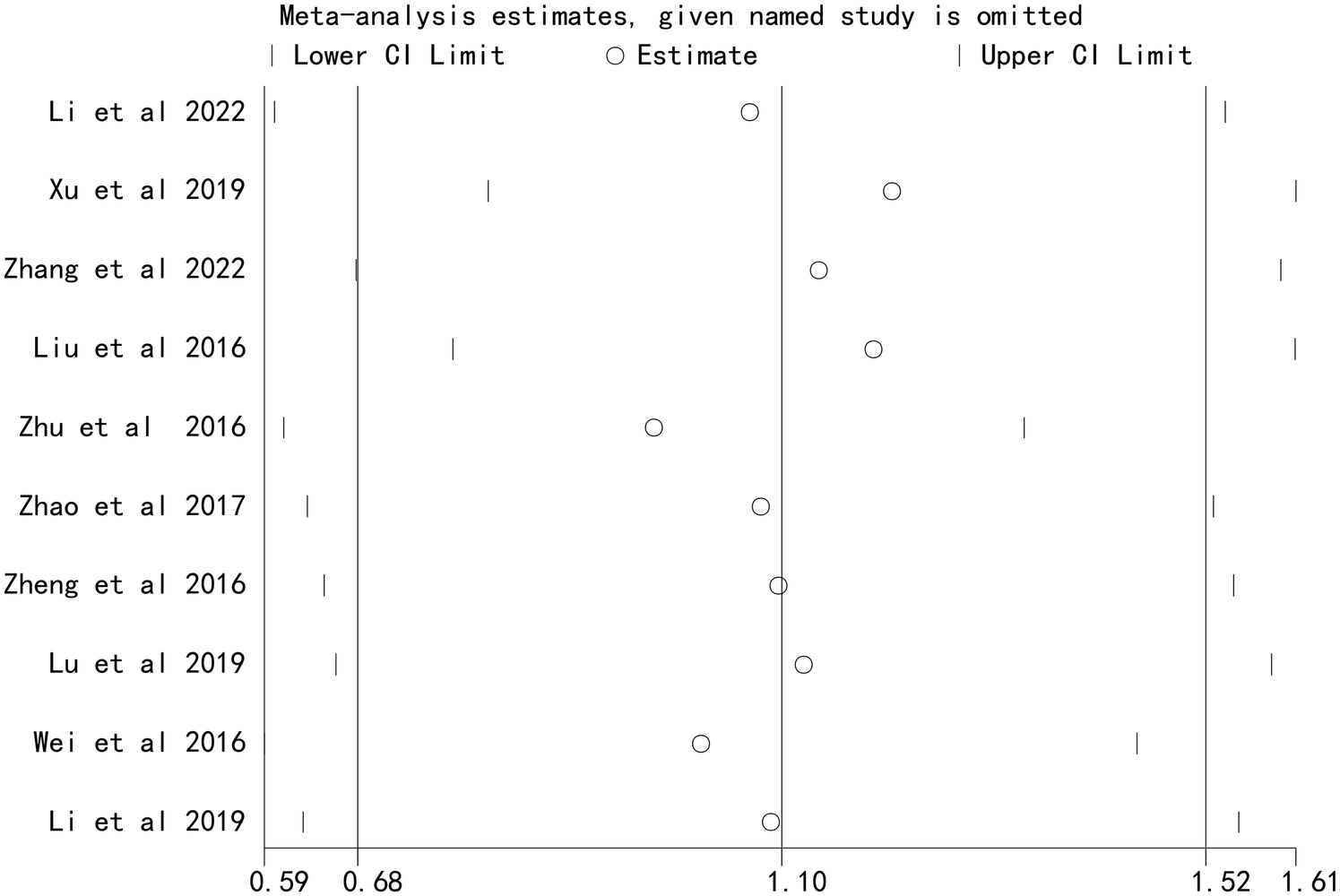

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis, performed by sequentially excluding each study, demonstrated that the overall effect estimates remained stable, indicating that the results were not driven by any single study (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4

Sensitivity analysis of the association between stent length and the risk of in stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 5

Sensitivity analysis of the association between stent number and the risk of in stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention.

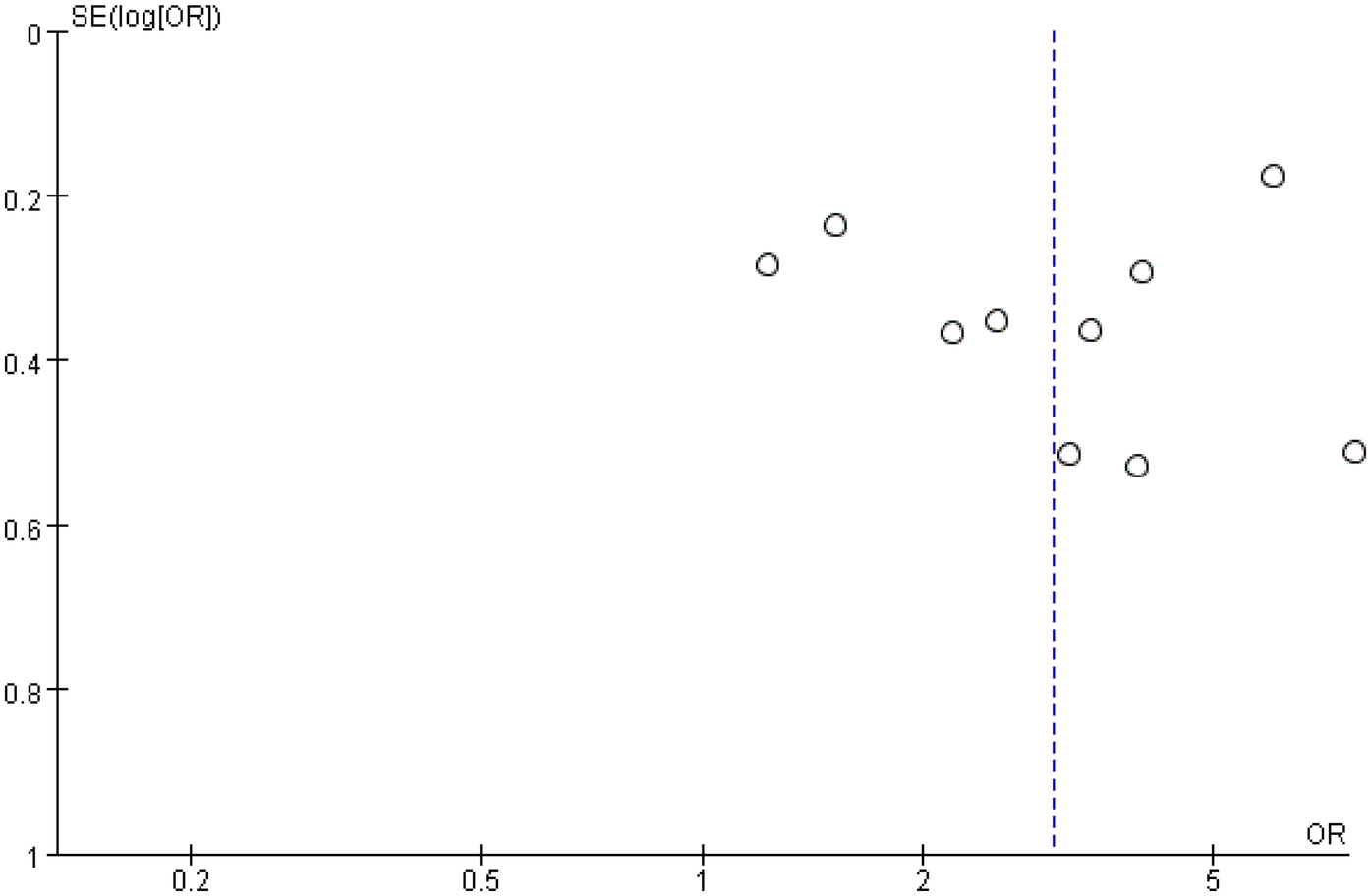

Publication bias

Funnel plots for stent length and stent number were generally symmetrical, suggesting a low likelihood of publication bias (Figures 6 and 7). This was further supported by Begg's Test and Egger's test, which showed no significant evidence of publication bias (Table 3).

Figure 6

![Funnel plot displaying the standard error of log odds ratio (SE(log[OR])) against the odds ratio (OR). Points are scattered with a slight asymmetry around the vertical dashed line at OR equals 1.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1673698/xml-images/fcvm-12-1673698-g006.webp)

Funnel plot of sensitivity analysis of the association between stent length and the risk of in stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 7

Funnel plot of the association between stent number and the risk of in stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 3

| Outcomes | Begg's test (P-value) | Egger's test (P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Stent length | 0.386 | 0.543 |

| Stent number | 0.174 | 0.065 |

Publication bias analysis.

Discussion

We conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the association of stent length and number with the risk of ISR after PCI in CAD patients. Based on a comprehensive analysis of eighteen observational studies, we found that both longer stent length and a greater number of stents were significantly associated with an increased risk of ISR, with stent number showing a particularly strong effect. These results underscore the importance of stent characteristics in determining ISR risk after PCI.

The pathogenesis of ISR involves a complex pathological process, including smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, sustained inflammatory responses, and the development of in-stent neoatherosclerosis (ISNA) (39–41). During PCI, stent length and number are selected based on lesion morphology, angulation, and side-branch involvement (42, 43). Longer stents can increase procedural complexity, require more balloon inflations, and exacerbate vascular injury and inflammation, thereby elevating ISR risk (4, 44). In practice, to ensure complete coverage of dissections or diseased segments and maintain lumen patency, stents are typically extended several millimeters beyond the angiographic margins of the lesion (45). However, longer stents may cause more extensive vascular damage and induce unfavorable hemodynamic changes, creating conditions conducive to ISR (46, 47). Hong et al. (48) identified stent length ≥40 mm as an independent risk factor for ISR after PCI in CAD patients. Extended stent length may intensify endothelial injury, while also negatively affecting the natural healing process of blood vessels, thereby promoting the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells and ultimately leading to the occurrence of restenosis (49, 50). Therefore, in clinical practice, selecting an appropriate stent length is critical, particularly in high-risk patients.

An increased number of stents was also strongly associated with ISR risk, likely due to the amplified biological response following multiple stent implantations (16). The presence of multiple stents introduces more foreign material and may alter local hemodynamics, delaying the healing and regeneration process of the blood vessels (43). Moreover, the contact surface of multiple stents is enlarged, which may enhance inflammatory activation and neointimal hyperplasia (51, 52). Li et al. (17) reported that patients with ISR received more stents than those without ISR. Overlapping stents can cause geometric interference, disturb laminar flow, and promote abnormal endothelial growth (53). In addition, implanting multiple stents increases vascular resistance and requires higher deployment pressures, which may aggravate endothelial injury and trigger platelet adhesion, contributing to ISR (36, 54). This risk is particularly pronounced in small-vessel PCI, where stent placement is more likely to cause intimal damage and subsequent restenosis (30, 35). Thus, minimizing the number of stents represents an important clinical strategy during PCI.

The development and progression of ISR are influenced by multiple factors, including stent type, diabetes mellitus, vessel diameter, clinical presentation (acute vs. chronic), bifurcation lesions, and lesion complexity. A deeper understanding of their interactions is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies for ISR. Diabetes, bifurcation lesions, small vessel diameter, and complex lesions significantly increase ISR risk (55). In diabetic patients, upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines may intensify vascular inflammation and promote restenosis (56, 57). Longer lesion length is also associated with higher ISR risk; for every 10 mm increase in lesion length, the percent diameter stenosis rises by an absolute 7.7% (46). Vessel diameter is another key anatomical factor and a strong predictor of ISR after both bare-metal stent (BMS) and drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation (58). ISR risk was significantly higher with BMS than with DES (55). The incidence of coronary ISR in early balloon angioplasty exceeded 50%. The application of BMS reduced it to 20%–30%, and DES further lowered it to 5%–15% (59). Second-generation DES, with improved polymer coatings and drug-release kinetics, have achieved even lower restenosis rates (60). The studies included in our analysis span a considerable period, covering the evolution from BMS to first- and second-generation DES. This technological progress has substantially altered the mechanisms and incidence of restenosis. Second-generation DES, featuring enhanced stent platforms, biocompatible polymers, and antiproliferative drugs, significantly reduce ISR risk compared with BMS and first-generation DES. Advances in implantation techniques—such as routine intravascular imaging for optimal sizing and expansion, high-pressure post-dilation, and improved perioperative medication—have also contributed to lowering restenosis risk. As the included studies cover different eras, they naturally reflect this technological progression. Future studies should consider stratifying analyses by stent generation (especially comparing first- vs. second-generation DES) to better reflect contemporary practice. Patients undergoing complex PCI (long stents/multiple stents) may benefit from intensified antithrombotic regimens to reduce thrombotic events, though bleeding risks must be balanced. Oliva et al. (61) reported that P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy offered improved safety regarding major bleeding compared with standard dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in complex PCI patients, without increasing ischemic events. In fact, P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy was associated with a lower risk of myocardial infarction than DAPT. Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) avoid long-term foreign-body reactions but carry a higher risk of early scaffold thrombosis, partly due to vascular recoil and delayed endothelial healing. Biodegradable stents have potential advantages in reducing ISR (62). These stents can provide the necessary support and drug release, and then gradually degrade while promoting the self-repair ability of blood vessels. However, although biodegradable stents show promise in preventing ISR, further long-term follow-up studies are still needed to verify their safety and durability (63). Future research should aim to elucidate the interplay of these multifactorial processes to improve clinical management of ISR and enhance patient quality of life.

Limitations of this study

Our meta-analysis offers robust evidence supporting the association of stent length and number with the risk of ISR. However, several limitations should be considered. First, the number of available studies was limited, particularly from certain geographical regions and diverse populations, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. Second, although no significant publication bias was detected, the potential influence of unpublished negative results cannot be entirely ruled out. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis, which may be attributed to variations in reported stent length and number, as well as differences in sample sizes across studies. These factors could affect the reliability of the conclusions.

Conclusion

In summary, our meta-analysis confirms that stent length and number are significant risk factors for ISR after PCI in patients with CAD. These findings offer valuable insights for clinicians in stent selection and provide a basis for further research on stent design and treatment strategy optimization. Given the limitations related to sample size, study design, and heterogeneity, future high-quality studies are warranted to validate these results.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

CC: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Resources, Conceptualization, Visualization. LL: Validation, Project administration, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. XJ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization, Resources. ZS: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by the Wenzhou Scientific Research project (N0.Y20240297).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1673698/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Collet JP Thiele H Barbato E Barthélémy O Bauersachs J Bhatt DL et al 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(14):1289–367. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575

2.

Virani SS Alonso A Benjamin EJ Bittencourt MS Callaway CW Carson AP et al Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2020) 141(9):e139–596. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757

3.

Liu Y Li Z Wang X Ni T Ma M He Y et al Effects of adjuvant Chinese patent medicine therapy on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease angina pectoris: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Acupunct Herbal Med. (2022) 2(2):109–17. 10.1097/HM9.0000000000000028

4.

Yang S Yang S Geng C Gao F . Research progress of stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Chin J Integr Med Cardio Cerebrovasc Dis. (2023) 21(20):3754–60. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-5062.2023.04.004

5.

Yang X Feng H Gao L . Recurrent in-stent restenosis. Adv Cardiovasc Dis. (2022) 43(08):677–679+683. 10.16806/j.cnki.issn.1004-3934.2022.08.002

6.

Xu K Zheng X Yang X Zhang W Shen L He B . Prognostic value of computed tomography-derived coronary artery calcium score on in-stent restenosis in patients receiving drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77(18):1322. 10.1016/S0735-1097(21)02680-2

7.

Neumann FJ Sousa-Uva M Ahlsson A Alfonso F Banning AP Benedetto U et al 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40(2):87–165. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

8.

Giacoppo D Gargiulo G Aruta P Capranzano P Tamburino C Capodanno D . Treatment strategies for coronary in-stent restenosis: systematic review and hierarchical Bayesian network meta-analysis of 24 randomised trials and 4880 patients. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). (2015) 351:h5392. 10.1136/bmj.h5392

9.

Polimeni A Weissner M Schochlow K Ullrich H Indolfi C Dijkstra J et al Incidence, clinical presentation, and predictors of clinical restenosis in coronary bioresorbable scaffolds. JACC Cardiovasc Interven. (2017) 10(18):1819–27. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.07.034

10.

Verheye S Ormiston JA Stewart J Webster M Sanidas E Costa R et al A next-generation bioresorbable coronary scaffold system: from bench to first clinical evaluation: 6- and 12-month clinical and multimodality imaging results. JACC Cardiovasc Interven. (2014) 7(1):89–99. 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.07.007

11.

Kereiakes DJ Ellis SG Metzger C Caputo RP Rizik DG Teirstein PS et al 3-Year Clinical Outcomes With Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Coronary Scaffolds: The ABSORB III Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 70(23):2852–62. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.010

12.

Polimeni A Anadol R Münzel T Indolfi C De Rosa S Gori T . Long-term outcome of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds for the treatment of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of RCTs. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2017) 17(1):147. 10.1186/s12872-017-0586-2

13.

Yang Q Wang Y Cao F . Review of coronary in-stent restenosis and its risk factors. Chin J Mult Organ Dis Elderly. (2021) 20(09):697–701. 10.11915/j.issn.1671-5403.2021.009.146

14.

Chen HJ Mo N Zhang YF Su GZ Wu HD Pei F . Role of gene polymorphisms/haplotypes and plasma level of TGF-β1 in susceptibility to in-stent restenosis following coronary implantation of bare metal stent in Chinese han patients. Int Heart J. (2018) 59(1):161–9. 10.1536/ihj.17-190

15.

Duan Y Li D Liu C Yan P Cheng J . Risk factors of in-stent restenosis in patients with coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiovasc Pulmon Dis. (2023) 42(04):309–13. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-5062.2023.04.004

16.

Alexandrescu DM Mitu O Costache II Macovei L Mitu I Alexandrescu A et al Risk factors associated with intra-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Exp Ther Med. (2021) 22(4):1141. 10.3892/etm.2021.10575

17.

Li M Hou J Gu X Weng R Zhong Z Liu S . Incidence and risk factors of in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients from southern China. Eur J Med Res. (2022) 27(1):12. 10.1186/s40001-022-00640-z

18.

Xu X Pandit RU Han L Li Y Guo X . Remnant lipoprotein cholesterol independently associates with in-stent restenosis after drug-eluting stenting for coronary artery disease. Angiology. (2019) 70(9):853–9. 10.1177/0003319719854296

19.

Zhang J Zhang Q Zhao K Bian YJ Liu Y Xue YT . Risk factors for in-stent restenosis after coronary stent implantation in patients with coronary artery disease: a retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). (2022) 101(47):e31707. 10.1097/MD.0000000000031707

20.

Wang J Wu Q Liu L Han X Dong C Yu J . Risk factors and predictive models for intrastent restenosis in patients with coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Shandong Med J. (2024) 64(06):57–60. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2024.06.013

21.

Zhu C Lv Z Zhu F Wang Y Huang J Wang T et al Study on risk factors and development of a predictive model for recurrent in-stent restenosis in patients with coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Chin Circ J. (2024) 39(05):456–63. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2024.05.005

22.

Kang SJ Mintz GS Park DW Lee S-W Kim Y-H Whan Lee C et al Mechanisms of in-stent restenosis after drug-eluting stent implantation: intravascular ultrasound analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interven. (2011) 4(1):9–14. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.940320

23.

Nikolakopoulou A Mavridis D Salanti G . How to interpret meta-analysis models: fixed effect and random effects meta-analyses. Evid Based Ment Health. (2014) 17(2):64. 10.1136/eb-2014-101794

24.

Yildiz A Tekiner F Karakurt A Sirin G Duman D . Preprocedural red blood cell distribution width predicts bare metal stent restenosis. Coron Artery Dis. (2014) 25(6):469–73. 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000105

25.

Deng C Deng W Xu G Wang Z Gu N Yu F et al Analysis of related factors of in-stent restenosis in patients with coronary heart disease after PCI. Chin J Arterioscler. (2017) 25(3):278–83. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-3949.2017.03.012

26.

Li J Long J Li M Guo K Fu Y Guo Z . Effect of Lp(a) on in-stent restenosis and non-target coronary lesions in CAD patients with drug-eluting stents. Med J Chin People’s Liber Army. (2019) 44(10):851–6. 10.11855/j.issn.0577-7402.2019.10.07

27.

Li H Chen M Zhu L Guo Z Wu Y . Analysis of factors related to intrastent restenosis after coronary artery stenting. China Pharmaceut. (2017) 26(A02):131–2. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4931.2017.Z2.091

28.

Liu Z Xia H Yang Y Li J . Risk factors of in-stent restenosis in coronary artery disease patients with CYP2C19. J Pract Med. (2016) 32(07):1088–92. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5725.2016.07.017

29.

Lu Z Jiang J Feng X . Correlation between serum HMGB2 and in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Chin J Evid Based Cardiovasc Med. (2019) 11(01):38–40 + 47. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2019.01.09

30.

Pan C . The clinical study on relationship of CTRP5 with restenosis aftercoronary drug-eluting stent implantation (Master). Yinchuan City: Ningxia Medical University (2015).

31.

Tang X Li F Qin L . Correlation between endothelin-1 and in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary heart disease. Chin J Evid-Based Cardiovasc Med. (2018) 10(02):227–9. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2018.02.28

32.

Wei Y Wang A . Analysis of related factors and corresponding prevention and treatment of coronary restenosis after implantation of drug-eluting stents. Mod J Integr Trad Chin West Med. (2016) 25(10):1118–20. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2016.10.033

33.

Yang K . Correlation research between CTRP3 and in-stent restenosis after coronary drug-eluting stent implantation (Master). Yan'an City: Yan'an University (2018).

34.

Zhang D Li Z Zhang J Yin C Chen X Sun J . Correlation between red blood cell distribution width and in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary heart disease after PCI. Clin Med China. (2017) 33(12):1084–8. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-6315.2017.12.007

35.

Zhang Y Lu X . Cox regression analysis of related risk factors for in-stent restenosis after coronary artery stent implanting. Chin J Front Med Sci. (2016) 8(7):4. 10.2016-07-021

36.

Zhao H Zhang J . Analysis of causes to in-stent restenosis one year after PCI. Med J Natl Def Forces Southwest China. (2017) 27(4):329–32. 10.3969/j.issn.1004-0188.2017.04.003

37.

Zheng W Wang X Zhang S Zhao L . Relationship between H-type hypertension and intrastent restenosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction after emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. J Pract Med. (2016) 32(01):88–90. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5725.2016.01.027

38.

Zhu C Qian G Ren Y . Analysis of factors related to intrastent restenosis after coronary interventional therapy. People’s Military Surgeon. (2016) 59(11):1147–1149+ 1152. CNKI:SUN:RMJZ.0.2016-11-033

39.

Kang SJ Mintz GS Akasaka T Park D-W Lee J-Y Kim W-J et al Optical coherence tomographic analysis of in-stent neoatherosclerosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. (2011) 123(25):2954–63. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.988436

40.

Yonetsu T Kato K Kim SJ Xing L Jia H McNulty I et al Predictors for neoatherosclerosis: a retrospective observational study from the optical coherence tomography registry. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. (2012) 5(5):660–6. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.976167

41.

Fallatah R Elasfar A Amoudi O Ajaz M AlHarbi I Abuelatta R . Endovascular repair of severe aortic coarctation, transcatheter aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis, and percutaneous coronary intervention in an elderly patient with long term follow-up. J Saudi Heart Assoc. (2018) 30(3):271–5. 10.1016/j.jsha.2018.01.003

42.

Lu X Yang Y Zhang J Chen X . Hemodynamic study progress of coronary bifurcation lesions and stent restenosis. World Latest Med Inf. (2017) 17(61):11–2. 10.19613/j.cnki.1671-3141.2017.61.006

43.

Giustino G Colombo A Camaj A Yasumura K Mehran R Stone GW et al Coronary in-stent restenosis: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 80(4):348–72. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.017

44.

Cheng G Chang FJ Wang Y You P-H Chen H-C Han W-Q et al Factors influencing stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary heart disease: a clinical trial based on 1-year follow-up. Med Sci Monit. (2019) 25:240–7. 10.12659/MSM.908692

45.

Zhang K Li Y . Research progress in risk factors of in-stent restenosis in patients with coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Med Recapitul. (2022) 28(01):105–11. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2084.2022.01.019

46.

Mauri L O'Malley AJ Cutlip DE Ho KKL Popma JJ Chauhan MS et al Effects of stent length and lesion length on coronary restenosis. Am J Cardiol. (2004) 93(11):1340–6; a1345. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.027

47.

Zhao Q . Risk factors of stent restenosis in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention [Master]. Yan'an City: Yan'an University (2023).

48.

Hong MK Mintz GS Lee CW Park DW Choi BR Park KH et al Intravascular ultrasound predictors of angiographic restenosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. (2006) 27(11):1305–10. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi882

49.

Fu Q Liu J Zhang X Zheng Q Huang X . Relationship between stent length and in-stent restenosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome after stent implantation. Sichuan Med J. (2024) 45(07):744–8. 10.16252/j.cnki.issn1004-0501-2024.07.009

50.

Xi Y Huang Y Du R Wang Y Wang G Yin T . Endothelial injury and its repair strategies after intravascular stents implantation. J Biomed Eng. (2018) 35(02):307–13. 10.7507/1001-5515.201612008

51.

Wang P Qiao H Wang R Hou R Guo J . The characteristics and risk factors of in-stent restenosis in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: what can we do. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2020) 20(1):510. 10.1186/s12872-020-01798-2

52.

Tang L Cui QW Liu DP Fu YY . The number of stents was an independent risk of stent restenosis in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98(50):e18312. 10.1097/MD.0000000000018312

53.

Eyüboğlu M . In stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Anatol J Cardiol. (2016) 16(1):73. 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2015.6775

54.

Yang L Wang L . Correlational factors analysis of coronary artery in-stent restenosis. Chin J Arterioscler. (2013) 21(05):449–53. 10.20039/j.cnki.1007-3949.2013.05.014

55.

Wu C Zheng Y Zhang T Liu M Xian L Xu Y . Incidence and influencing factors of in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2025) 106(3):1682–99. 10.1002/ccd.31711

56.

Jakubiak GK Pawlas N Cieślar G Stanek A . Pathogenesis and clinical significance of in-stent restenosis in patients with diabetes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(22):11970. 10.3390/ijerph182211970

57.

Bacigalupi E Pelliccia F Zimarino M . Diabetes mellitus and in-stent restenosis: a direct link or something more?Int J Cardiol. (2024) 404:131922. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131922

58.

Camaj A Giustino G Claessen BE Baber U Power DA Sartori S et al Effect of stent diameter in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with early- and new-generation drug-eluting stents: from the WIN-DES collaboration. Int J Cardiol. (2019) 287:59–61. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.03.034

59.

Sakamoto A Sato Y Kawakami R Cornelissen A Mori M Kawai K et al Risk prediction of in-stent restenosis among patients with coronary drug-eluting stents: current clinical approaches and challenges. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. (2021) 19(9):801–16. 10.1080/14779072.2021.1856657

60.

Bai H Zhang B Sun Y Wang X Luan B Zhang X . Research advances in the etiology of in-stent restenosis of coronary arteries. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 12:1585102. 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1585102

61.

Oliva A Castiello DS Franzone A Condorelli G Colombo A Esposito G et al P2y12 inhibitors monotherapy in patients undergoing Complex vs non-Complex percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. (2023) 255:71–81. 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.10.006

62.

Li M Deng D Chen Z Liu W Zhao G Zhang Y et al Magnetic nanoparticle loaded biodegradable vascular stents for magnetic resonance imaging and long-term visualization. J Mater Chem B. (2023) 11(16):3669–78. 10.1039/D3TB00185G

63.

Zong J He Q Liu Y Qiu M Wu J Hu B . Advances in the development of biodegradable coronary stents: a translational perspective. Mater Today Bio. (2022) 16:100368. 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100368

Summary

Keywords

stent length, stent number, stent restenosis, percutaneous coronary intervention, meta-analysis, coronary artery disease

Citation

Cai C, Lu L, Ji X and Shi Z (2025) Association between stent length and number and the risk of in-stent restenosis in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1673698. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1673698

Received

17 August 2025

Accepted

26 September 2025

Published

09 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Alberto Polimeni, University of Magna Graecia, Italy

Reviewed by

Domenico Simone Castiello, Federico II University Hospital, Italy

Rossella Quarta, University of Calabria, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cai, Lu, Ji and Shi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Zhongping Shi szphello1981@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.