Abstract

Objective:

Heart transplantation (HT) is the ultimate treatment option for patients with end-stage heart failure, and its prognostic evaluation has consistently been a focal point in clinical research. This article primarily explores the impact of the pre-operative Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and its derivative scoring systems on the prognosis of HT patients.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis was conducted on the data of patients who underwent HT at Shanghai Changhai Hospital from January 2018 to January 2024. All included patients were scored using the MELD and its upgraded versions (MELD-XI, MELD-albumin). Initially, the preoperative baseline of survival group and non-survival group were compared. Subsequently, the association between various MELD scores and patient prognosis was analyzed using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Based on the higher Area Under the Curve (AUC), MELD-albumin was selected as the research indicator. Patients were then divided into high-score group and low-score group according to its optimal cutoff value, and the perioperative data of the two groups were compared.

Results:

A total of 170 patients were included in this study, with 159 patients (93.5%) in survival group and 11 patients (6.5%) in non-survival group. Comparison of preoperative and intraoperative baseline data between the two groups revealed that the non-survival group had a lower preoperative platelet count, higher preoperative creatinine levels and BNP levels, a lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and higher scores in MELD, MELD-XI, and MELD-albumin compared to the survival group. ROC analysis demonstrated that the AUC values for preoperative MELD scores in predicting in-hospital mortality were 0.806, 0.842 for MELD-XI, and 0.843 for MELD-albumin. MELD-albumin was selected as the primary indicator. Based on the optimal cutoff value of 8.4, patients were divided into low-score group (MELD-albumin ≤8.4, 128 cases) and high-score group (MELD-albumin >8.4, 42 cases) to explore its relationship with perioperative prognosis in HT. The results showed statistical differences between the two groups in preoperative white blood cell count, platelet count, monocyte count, bilirubin, creatinine, BNP, international normalized ratio (INR), and procalcitonin levels, while no statistical differences were observed in intraoperative data. Regarding prognosis, the high-score group had a higher mortality rate (19% vs. 2.3%, P = 0.0004) and a higher proportion of patients suffering postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) (38% vs. 18.7%, P = 0.023) and receiving continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) (14.3% vs. 4.7%, P = 0.039).

Conclusion:

This study confirms that the preoperative MELD-albumin score is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in HT patients, and its optimal cutoff value of 8.4 can effectively distinguish between high-risk and low-risk populations.

1 Introduction

Heart transplantation (HT) serves as the ultimate therapeutic option for patients with end-stage heart failure (1), and its prognostic evaluation has consistently been a focal point of clinical research. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) primarily encompasses objective laboratory parameters, including the international normalized ratio (INR), serum bilirubin, and creatinine (2). Currently, it has emerged as the primary scoring tool for prioritizing patients awaiting liver transplantation (3). In recent years, the application of MELD and its derivative scoring systems in the field of cardiovascular surgery has gradually garnered attention (4, 5). Among them, MELD-Albumin (a modified model that replaces INR with albumin) has become an important predictive tool due to its ability to integrate hepatic and renal function with nutritional status. The traditional MELD model evaluates hepatic and renal function through three indicators: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. However, INR is susceptible to interference from non-hepatic disease factors, leading to potential scoring biases. MELD-Albumin innovatively substitutes serum albumin for INR, considering that hypoalbuminemia is a significant marker of liver dysfunction, malnutrition, and acute-phase responses. By incorporating albumin, the new scoring model can better predict short-term mortality in liver transplantation patients (6). This article primarily explores the impact of the preoperative MELD-Albumin scoring model on the prognosis of HT patients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study subjects

A retrospective analysis was conducted on the data of patients who underwent HT at department of Cardiovascular surgery, Shanghai Changhai Hospital, The Naval Medical University from January 2018 to January 2024.

2.2 Study methods

For all selected study subjects, variable data were cleaned, encoded, and preprocessed to ensure data accuracy and completeness. Patients were then scored using the MELD and its upgraded versions (MELD-XI, MELD-albumin). Initially, based on the patients’ perioperative prognosis (28-day mortality), they were divided into survival group and non-survival group. The preoperative baseline data of the two groups were compared, with particular attention to the correlation between various MELD scores and prognosis. Subsequently, ROC analysis was performed to assess the association between these MELD scores and patient prognosis. Given the higher AUC values, MELD-albumin was selected as the research indicator. Patients were grouped into high-score group and low-score group based on its optimal cutoff value, and the perioperative data of the two groups were compared.

2.3 Calculation formulas for study indicators

-

MELD = 3.78 × ln(total bilirubin) + 11.2 × ln(INR) + 9.57 × ln(serum creatinine) + 6.43 × (etiological correction factor);

-

MELD-XI = 5.11 × ln(total bilirubin) + 11.76 × ln(serum creatinine);

-

MELD-albumin = 3.78 × ln(total bilirubin) + 9.57 × ln(serum creatinine) + 5.1 × ln(albumin) + 6.43 × (etiological correction factor).

2.4 Informed consent and ethical statement

This study is a retrospective observational case-control study that does not involve active intervention or additional data collection from subjects. All patients provided informed consent and signed informed consent forms. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University after review, with the approval number: CHEC2025-398.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software. For measurement data that conformed to a normal distribution and met the assumption of homogeneity of variance, they were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s), and comparisons between two groups were made using independent samples t-tests. Otherwise, data were expressed as median (lower quartile, upper quartile), and comparisons between two groups were made using non-parametric rank-sum tests. Categorical data were expressed as counts and percentages, and comparisons between two groups were made using the χ2 test. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

A total of 170 patients were included in this study, with 159 patients (93.5%) in the survival group and 11 patients (6.5%) in the non-survival group. Comparison of preoperative and intraoperative baseline data between the two groups revealed that the non-survival group had a lower preoperative platelet count [140.00 (83.00, 187.00) vs. 171.00 (136.00, 207.00), P = 0.033], higher preoperative creatinine levels [1.93 (1.24, 3.63) vs. 0.97 (0.69, 1.21), P < 0.001], higher preoperative BNP levels [4,663.53 (1,275.91, 5,000.00) vs. 1,275.91 (638.51, 2,852.98), P = 0.007], lower LVEF [19.00 (15.00, 22.00) vs. 24.00 (20.00, 32.00), P = 0.006], and higher scores in MELD [11.29 (8.15, 18.39) vs. 7.74 (5.48, 9.25), P < 0.001], MELD-XI [14.26 (12.02, 16.15) vs. 9.83 (7.77, 11.41), P < 0.001], and MELD-albumin [10.48 (8.43, 11.62) vs. 6.68 (5.01, 7.98), P < 0.001]. No statistically significant differences were observed in intraoperative conditions (Table 1).

Table 1

| In-hospital death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall N = 170a | Survival N = 159a | Non-survival N = 11a | p-valueb |

| Preoperative data | ||||

| Gender (Male, %) | 132 (78%) | 122 (77%) | 10 (91%) | 0.46 |

| Age | 52.00 (39.00, 60.00) | 52.00 (38.00, 59.00) | 52.00 (43.00, 63.00) | 0.67 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 137 (81%) | 129 (81%) | 8 (73%) | 0.45 |

| T2DM | 23 (14%) | 22 (14%) | 1 (9.1%) | >0.99 |

| Hypertension | 41 (24%) | 39 (25%) | 2 (18%) | >0.99 |

| Coronary artery disease | 22 (13%) | 19 (12%) | 3 (27%) | 0.16 |

| Heart valve disease | 50 (29%) | 47 (30%) | 3 (27%) | >0.99 |

| COPD | 3 (1.8%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 |

| WBC count (109 /L) | 7.67 (5.91, 9.97) | 7.57 (5.81, 9.88) | 8.33 (7.46, 18.35) | 0.11 |

| Platelet count (109 /L) | 171.00 (133.00, 207.00) | 171.00 (136.00, 207.00) | 140.00 (83.00, 187.00) | 0.033 |

| Monocyte count (109 /L) | 0.69 (0.52, 1.09) | 0.68 (0.50, 1.09) | 0.88 (0.57, 4.60) | 0.37 |

| Lymphocyte count (109 /L) | 1.73 (1.09, 2.80) | 1.75 (1.12, 2.80) | 1.10 (0.48, 2.84) | 0.085 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL)) | 1.41 (0.87, 2.05) | 1.35 (0.87, 2.05) | 1.71 (1.22, 3.62) | 0.11 |

| Serum creatinine(mg/dL) | 0.98 (0.71, 1.27) | 0.97 (0.69, 1.21) | 1.93 (1.24, 3.63) | <0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 26.00 (19.00, 52.00) | 26.00 (19.00, 48.00) | 24.00 (21.00, 275.00) | 0.37 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.00 (19.00, 50.00) | 25.00 (19.00, 50.00) | 32.00 (13.00, 189.00) | 0.90 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.00 (37.00, 43.00) | 40.00 (37.00, 44.00) | 38.00 (34.00, 41.00) | 0.16 |

| BNP (ng/L) | 1,275.91 (701.00, 3,038.00) | 1,275.91 (638.51, 2,852.98) | 4,663.53 (1,275.91, 5,000.00) | 0.007 |

| INR | 1.17 (1.05, 1.40) | 1.17 (1.05, 1.38) | 1.40 (1.16, 2.04) | 0.071 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.58 (0.58, 0.59) | 0.58 (0.58, 0.58) | 0.58 (0.58, 1.97) | 0.13 |

| LVEF (%) | 24.00 (19.00, 31.00) | 24.00 (20.00, 32.00) | 19.00 (15.00, 22.00) | 0.006 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 24.00 (21.00, 29.00) | 24.00 (21.00, 28.00) | 31.00 (24.00, 36.00) | 0.11 |

| MELD | 7.81 (5.65, 9.53) | 7.74 (5.48, 9.25) | 11.29 (8.15, 18.39) | <0.001 |

| MELD-XI | 9.96 (7.85, 12.02) | 9.83 (7.77, 11.41) | 14.26 (12.02, 16.15) | <0.001 |

| MELD-albumin | 6.79 (5.14, 8.39) | 6.68 (5.01, 7.98) | 10.48 (8.43, 11.62) | <0.001 |

| Operative data | ||||

| CPB time (min) | 149.00 (120.00, 173.00) | 148.00 (117.00, 172.00) | 168.00 (125.00, 181.00) | 0.17 |

| Aortic cross clamp time (min) | 45.00 (38.00, 53.00) | 45.00 (38.00, 53.00) | 45.00 (40.00, 56.00) | 0.35 |

| Ischemia time (min) | 188.00 (72.00, 348.00) | 190.00 (78.00, 350.00) | 132.00 (63.00, 315.00) | 0.25 |

| Assist circulation time (min) | 95.00 (58.00, 115.00) | 95.00 (58.00, 113.00) | 99.00 (57.00, 121.00) | 0.70 |

Patient characteristics by in-hospital death.

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; WBC, white blood cell; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; INR, international normalized ratio; PCT, Procalcitonin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Median (Q1, Q3) or Frequency (%).

Fisher's exact test; Wilcoxon rank sum test.

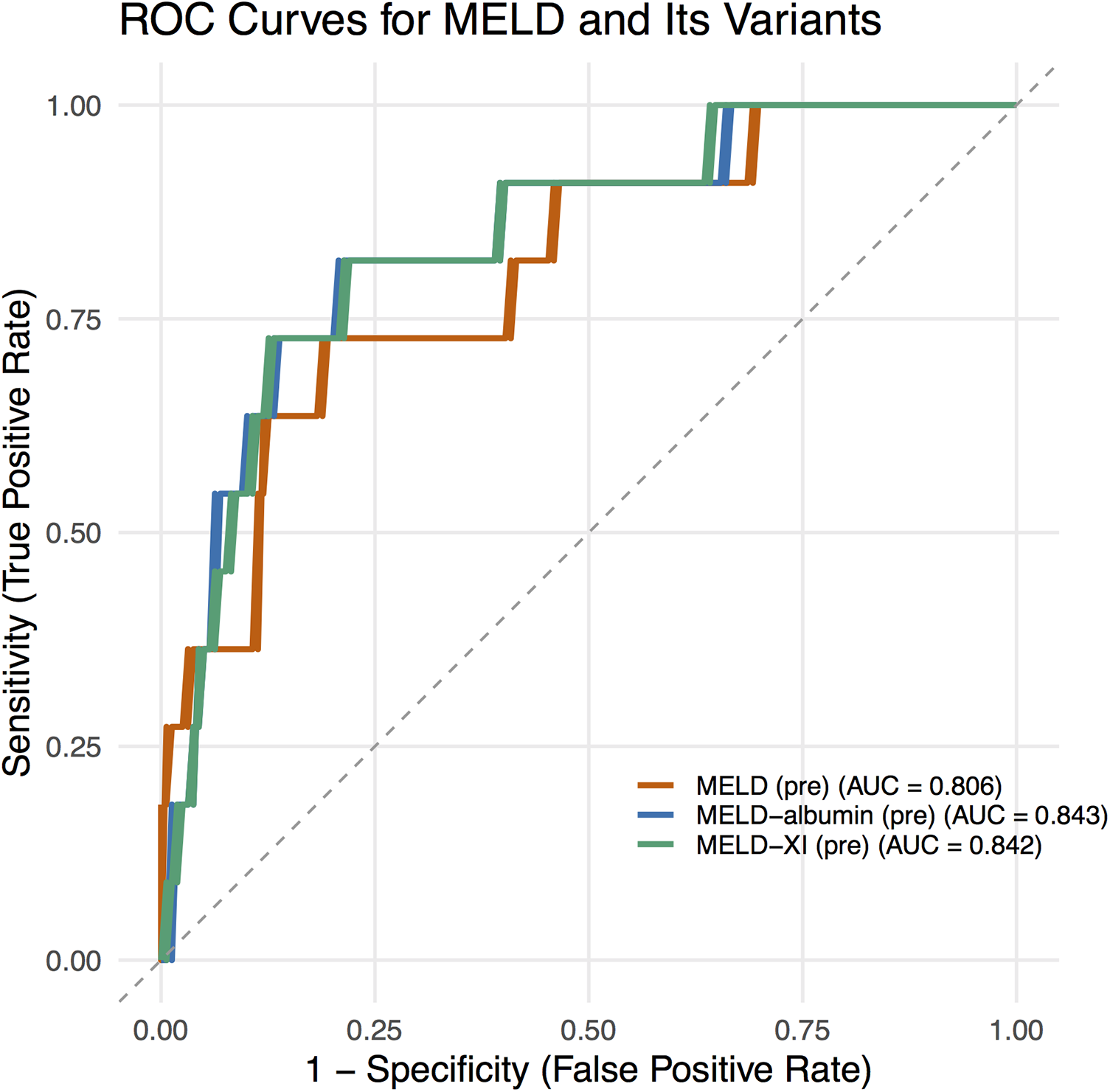

ROC analysis demonstrated that the AUC values for preoperative MELD scores in predicting in-hospital mortality were 0.806 for MELD, 0.842 for MELD-XI, and 0.843 for MELD-albumin (Figure 1), all indicating good predictive value.

Figure 1

ROC curves for MELD scores.

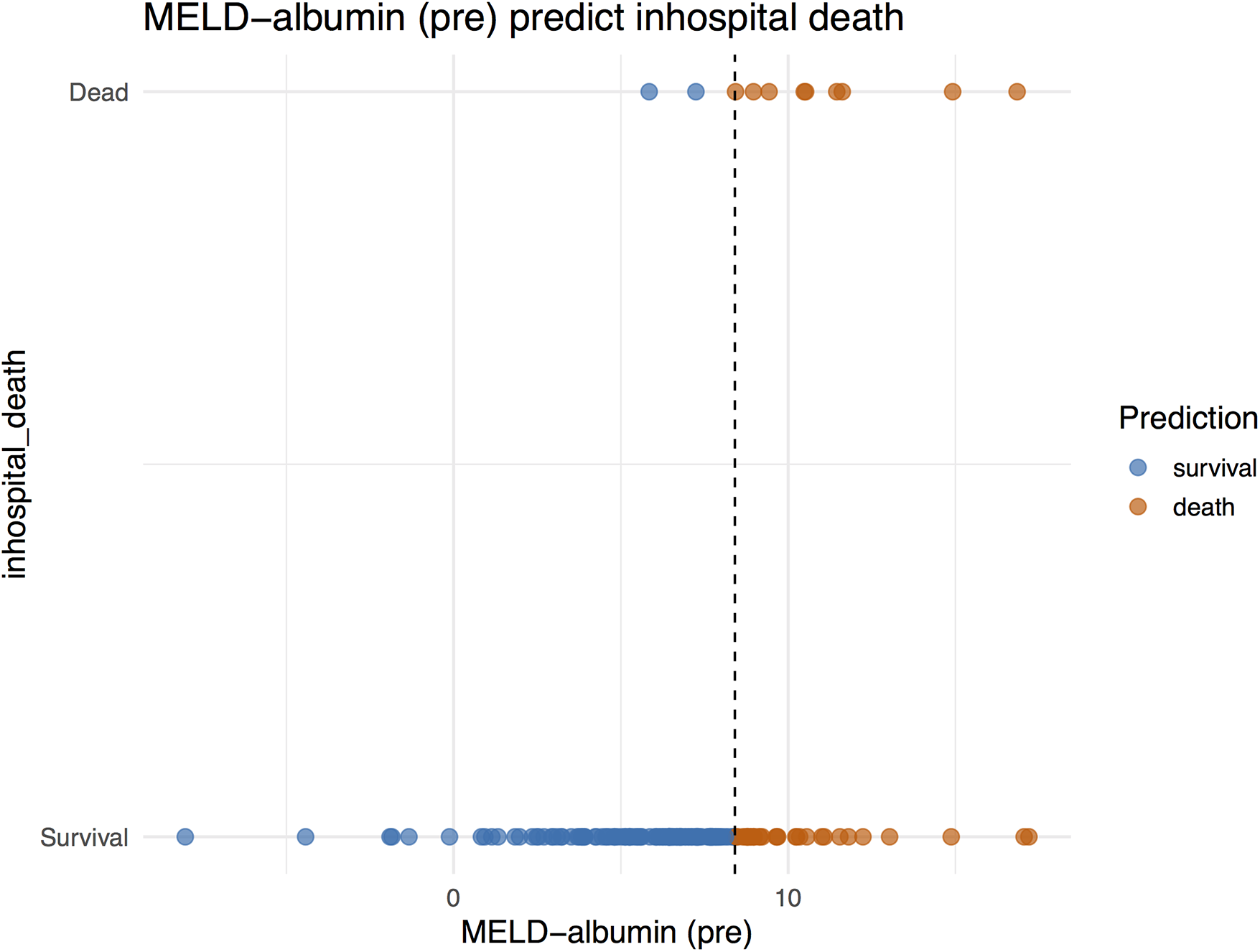

Decision analysis plots were simultaneously generated to illustrate the ability of the MELD−albumin (pre) scoring system to predict the risk of in-hospital mortality. These plots visually presented the predictive effect of MELD−albumin (pre) on patient prognosis. As the score increased, the patients’ risk of mortality also rose. At lower scores, the prediction line approached the survival zone, indicating a lower risk of mortality for patients; conversely, as scores increased, the prediction line approached the mortality zone, indicating a higher risk of mortality for patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2

MELD−albumin predict in-hospital death.

Based on the superior AUC, MELD-albumin was selected as the primary indicator. Patients were divided into low-score group (MELD-albumin ≤8.4, 128 patients) and high-score group (MELD-albumin >8.4, 42 patients) according to the optimal cutoff value of 8.4, to explore the relationship between MELD-albumin and perioperative prognosis in HT. The results showed statistically significant differences between the two groups in preoperative white blood cell count, preoperative platelet count, preoperative monocyte count, preoperative bilirubin, preoperative creatinine, preoperative BNP, preoperative INR, and preoperative procalcitonin levels. No statistically significant differences were observed in intraoperative data. In terms of prognosis, the high-score group had a higher mortality rate (19% vs. 2.3%, P = 0.0004) and a higher proportion of patients suffering postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) (38% vs. 18.7%, P = 0.023) and receiving continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) (14.3% vs. 4.7%, P = 0.039) (Table 2).

Table 2

| MELD–albumin (pre) group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall N = 170a |

Low group (≤8.4) N = 1,28a |

High group (>8.4) N = 42a |

p-valueb |

| Preoperative data | ||||

| Gender (Male, %) | 132 (78%) | 95 (74%) | 37 (88%) | 0.061 |

| Age | 52.00 (39.00, 60.00) | 52.50 (38.50, 59.00) | 52.00 (39.00, 62.00) | 0.66 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 137 (81%) | 104 (81%) | 33 (79%) | 0.70 |

| T2DM | 23 (14%) | 19 (15%) | 4 (9.5%) | 0.38 |

| Hypertension | 41 (24%) | 32 (25%) | 9 (21%) | 0.64 |

| Coronary artery disease | 22 (13%) | 15 (12%) | 7 (17%) | 0.41 |

| Heart valve disease | 50 (29%) | 37 (29%) | 13 (31%) | 0.80 |

| COPD | 3 (1.8%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 |

| WBC count (109 /L) | 7.67 (5.91, 9.97) | 7.35 (5.68, 9.66) | 8.45 (7.46, 10.90) | 0.004 |

| Platelet count (109 /L) | 171.00 (133.00, 207.00) | 180.50 (144.50, 210.00) | 143.50 (108.00, 181.00) | 0.001 |

| Monocyte count (109 /L) | 0.69 (0.52, 1.09) | 0.67 (0.49, 0.96) | 0.85 (0.60, 4.50) | 0.025 |

| Lymphocyte count(109 /L) | 1.73 (1.09, 2.80) | 1.74 (1.17, 2.82) | 1.70 (0.60, 2.45) | 0.30 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL)) | 1.41 (0.87, 2.05) | 1.16 (0.84, 1.77) | 2.37 (1.85, 3.63) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine(mg/dL)) | 0.98 (0.71, 1.27) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.05) | 1.49 (1.27, 2.48) | <0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 26.00 (19.00, 52.00) | 26.00 (19.00, 41.00) | 24.00 (18.00, 104.00) | 0.45 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.00 (19.00, 50.00) | 24.00 (19.00, 46.00) | 31.00 (19.00, 69.00) | 0.23 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.00 (37.00, 43.00) | 40.00 (36.00, 43.50) | 39.00 (37.00, 43.00) | 0.52 |

| BNP (ng/L) | 1,275.91 (701.00, 3,038.00) | 1,156.75 (549.34, 2,656.28) | 1,895.00 (1,060.12, 4,712.00) | 0.002 |

| INR | 1.17 (1.05, 1.40) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.31) | 1.31 (1.17, 1.60) | 0.002 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.58 (0.58, 0.59) | 0.58 (0.35, 0.58) | 0.58 (0.58, 1.31) | 0.018 |

| LVEF (%) | 24.00 (19.00, 31.00) | 24.00 (19.50, 31.00) | 24.50 (19.00, 29.00) | 0.85 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 24.00 (21.00, 29.00) | 24.00 (20.00, 26.00) | 24.00 (24.00, 31.00) | 0.049 |

| Operative data | ||||

| CPB time (min) | 149.00 (120.00, 173.00) | 150.00 (120.50, 172.00) | 140.50 (110.00, 180.00) | 0.75 |

| Aortic cross clamp time (min) | 45.00 (38.00, 53.00) | 45.00 (38.00, 52.50) | 45.00 (40.00, 58.00) | 0.35 |

| Ischemia time (min) | 188.00 (72.00, 348.00) | 251.50 (104.00, 350.00) | 106.00 (63.00, 338.00) | 0.055 |

| Assist circulation time (min) | 95.00 (58.00, 115.00) | 97.00 (62.50, 115.50) | 83.00 (48.00, 113.00) | 0.11 |

| Postoperative data | ||||

| Mechanical assist | 36 (21%) | 26 (20%) | 10 (24%) | 0.63 |

| IABP (n, %) | 24 (14%) | 18 (14%) | 6 (14%) | 0.82 |

| ECMO (n, %) | 12 (7.1%) | 8 (6%) | 4 (5%) | 0.51 |

| ARF (n, %) | 22 (12.9%) | 14 (10.9%) | 8 (19%) | 0.17 |

| AKI (n, %) | 40 (23.5%) | 24 (18.7%) | 16 (38%) | 0.023 |

| CRRT (n, %) | 12 (5.9%) | 6 (4.7%) | 6 (14.3%) | 0.039 |

| Mortality (n, %) | 11(6.5%) | 3(2.3%) | 8(19%) | 0.0004 |

Patient characteristics by MELD–albumin (pre) group.

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; WBC, white blood cell; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; INR, international normalized ratio; PCT, procalcitonin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ARF, acute respiratory failure; AKI, acute kidney injury; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy.

Median (Q1, Q3) or Frequency (%).

Pearson's Chi-squared test; Fisher's exact test; Wilcoxon rank sum test.

4 Discussion

For the preoperative assessment of HT recipients, previous efforts have primarily focused on evaluating patients’ cardiopulmonary function, utilizing methods such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing (7, 8) and invasive hemodynamic monitoring via right heart catheterization. These approaches aim to assess the severity of heart failure, guide optimized medical treatment, and evaluate the presence of pulmonary hypertension to assess its impact on post-transplant right heart failure and survival (9–11). Additionally, various prognostic scoring systems have been developed for risk stratification in patients with heart failure (12). The Heart Failure Survival Score (HFSS), Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM), Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC) score, and Metabolic Exercise Test Data combined with Cardiac and Kidney Indexes (MECKI) score were specifically developed for patients with chronic heart failure (13–15). It should be noted that all scoring systems have inherent limitations, with most performing poorly when applied to individual patients (as opposed to populations), particularly due to the lack of assessment models for organ function in HT recipients. In this study, we innovatively applied the MELD-Albumin scoring model to HT recipients to validate its effectiveness as a preoperative assessment tool.

To our knowledge, MELD score originally developed for sequence of liver assessment and liver transplantation, with the progress of heart-related research helping to diagnose more subtle heart abnormalities, especially those overlooked in patients with liver cirrhosis, an increasing amount of data shows that heart dysfunction precedes the prediction of liver and kidney function development in patients (16). Patients with heart failure are prone to malnutrition and blood dilution, which may aggravate their liver function (17). Clinically, non-invasive imaging examinations such as abdominal ultrasound showing signs of liver congestion (dilation of the superior hepatic vein and inferior vena cava) can provide support (18). Rapid and transient increases in other laboratory tests such as aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase levels are typical manifestations of liver function impairment (19, 20). In particular, a serum ALT/LDH ratio less than 1.5 in the early stage is a characteristic of cardiogenic injury (21). Our findings revealed that patients with a preoperative MELD-Albumin score ≥8.4 had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality rate and required a higher proportion of CRRT for organ support postoperatively. These results confirm the critical role of the MELD-Albumin score in predicting postoperative outcomes in HT.

Notably, patients in the non-survival group exhibited lower preoperative platelet counts, elevated creatinine and BNP levels, and reduced LVEF. These findings suggest that renal dysfunction, poorer preoperative cardiac systolic function, and coagulation disorders are high-risk factors for mortality in HT patients. During preoperative assessment, it is crucial to place sufficient emphasis on evaluating organ function. The MELD-Albumin score, by integrating creatinine (reflecting renal function), bilirubin (reflecting hepatic function), and albumin (reflecting nutritional status and inflammatory response), comprehensively quantifies the degree of multi-organ dysfunction in patients, thereby enabling accurate prediction of postoperative mortality risk.

In our study, ROC analysis demonstrated that the AUC value of MELD-Albumin reached 0.843, outperforming both MELD (0.806) and MELD-XI (0.842). This indicates that the integration of albumin into the scoring system further enhances its prognostic predictive capability. Albumin is not only a core component in maintaining plasma colloid osmotic pressure but also possesses multiple biological functions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and endotoxin-binding properties. Hypoalbuminemia can arise from various causes, such as liver damage during the acute phase of inflammatory processes, increased renal excretion, malnutrition, heightened catabolism, intestinal losses, severe volume overload, and escape into the interstitial space (22). It serves as a robust, reliable, and dependent prognostic indicator in patients with conditions including coronary artery disease (CAD) and heart failure (23), and is particularly prevalent among those with end-stage heart failure. A retrospective review of 1,726 patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (aged 52 ± 13 years, LVEF 23 ± 7%) revealed that 25% of patients had hypoalbuminemia (≤3.4 g/dL), with a 1-year survival rate of 66% among those with hypoalbuminemia compared to 83% in those without (p < 0.0001) (24). Serum albumin is a potent predictor of death or heart failure hospitalization (25) and is an easily overlooked prognostic indicator (26). Given its reliable predictive value, serum albumin is routinely tested in all hospitalized patients. Its inclusion in the MELD score significantly enhances its prognostic value, especially in the preoperative assessment of heart failure recipients awaiting HT.

The optimal cutoff value for MELD-Albumin in predicting the prognosis of HT patients identified in this study was 8.4, which slightly differs from previously reported optimal cutoff values in other cardiovascular diseases. For instance, a study evaluating 152 patients undergoing isolated tricuspid valve replacement (ITVR) found that the MELD-albumin score was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality, with an optimal cutoff value of 8.58 determined by maximally selected log-rank statistics (27). This discrepancy may stem from several factors: First, differences in population characteristics: patients included in this study may have comprised more HT recipients without a cirrhosis background (e.g., those with dilated cardiomyopathy or ischemic cardiomyopathy), who exhibited more severe liver and kidney dysfunction. Second, limitations in sample size: the relatively small sample size in this study may have led to estimation bias in the cutoff value. Future research should involve multi-center, large-sample studies to establish a unified cutoff value, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the MELD-Albumin score.

5 Limitations

Our study also has several limitations. As a single-center retrospective design, due to the limited sample size, it may be susceptible to selection bias and information bias. Additionally, the lack of long-term follow-up data on 1-year or 5-year survival rates and the analysis of only 28-day mortality rates may impose limits the analysis to in-hospital mortality. Finally, we did not incorporate biomarkers such as inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6) or myocardial injury markers (e.g., TnI), which may have omitted critical prognostic information.

6 Conclusion

Our study confirms that the preoperative MELD-Albumin score serves as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in HT patients. With an optimal cutoff value of 8.4, it effectively distinguishes between high-risk and low-risk populations, thereby demonstrating its potential as a valuable tool for preoperative organ function assessment in HT recipients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. LX-b: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XZ-y: . HL: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. ZF: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. LB-l: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by National Key R & D Program of China (2024YFC3505700). New Technology Cultivation Project of Naval Medical University (ZXJS2024B16).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Peled Y Ducharme A Kittleson M Bansal N Stehlik J Amdani S et al International society for heart and lung transplantation guidelines for the evaluation and care of cardiac transplant candidates-2024. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2024) 43(10):1529–1628.e54. 10.1016/j.healun.2024.05.010

2.

Malinchoc M Kamath PS Gordon FD Peine CJ Rank J ter Borg PC . A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. (2000) 31(4):864–71. 10.1053/he.2000.5852

3.

Freeman RB Jr Wiesner RH Harper A McDiarmid SV Lake J Edwards E et al The new liver allocation system: moving toward evidence-based transplantation policy. Liver Transpl. (2002) 8(9):851–8. 10.1053/jlts.2002.35927

4.

Zhou W Wang G Liu Y Tao Y Tang Y Qiao F et al Outcome and risk factors of postoperative hepatic dysfunction in patients undergoing acute type A aortic dissection surgery. J Thorac Dis. (2019) 11(8):3225–33. 10.21037/jtd.2019.08.72

5.

Zhou W Liu X Lv X Shen T Ma S Zhu F . Application of model for end-stage liver disease as disease classification in cardiac valve surgery: a retrospective study based on the INSPIRE database. J Thorac Dis. (2024) 16(7):4495–503. 10.21037/jtd-24-242

6.

Myers RP Shaheen AA Faris P Aspinall AI Burak KW . Revision of MELD to include serum albumin improves prediction of mortality on the liver transplant waiting list. PLoS One. (2013) 8(1):e51926. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051926

7.

Garcia Brás P Gonçalves AV Reis JF Moreira RI Pereira-da-Silva T Rio P et al Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with heart failure: impact of gender in predictive value for heart transplantation listing. Life (Basel). (2023) 13(10):1985. 10.3390/life13101985

8.

Guazzi M Arena R Myers J . Comparison of the prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing between male and female patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. (2006) 113(3):395–400. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.11.105

9.

Hsich EM Blackstone EH Thuita L McNamara DM Rogers JG Ishwaran H et al Sex differences in mortality based on united network for organ sharing Status while awaiting heart transplantation. Circ Heart Fail. (2017) 10(6):e003635. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003635

10.

Hsich EM Thuita L McNamara DM Rogers JG Valapour M Goldberg LR et al Variables of importance in the scientific registry of transplant recipients database predictive of heart transplant waitlist mortality. Am J Transplant. (2019) 19(7):2067–76. 10.1111/ajt.15265

11.

Baudry G Coutance G Dorent R Bauer F Blanchart K Boignard A et al Prognosis value of forrester’s classification in advanced heart failure patients awaiting heart transplantation. ESC Heart Fail. (2022) 9(5):3287–97. 10.1002/ehf2.14037

12.

Rahimi K Bennett D Conrad N Williams TM Basu J Dwight J et al Risk prediction in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and analysis. JACC Heart Fail. (2014) 2(5):440–6. 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.04.008

13.

Pocock SJ Ariti CA McMurray JJ Maggioni A Køber L Squire IB et al Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J. (2013) 34(19):1404–13. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs337

14.

Levy WC Mozaffarian D Linker DT Sutradhar SC Anker SD Cropp AB et al The Seattle heart failure model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. (2006) 113(11):1424–33. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102

15.

Aaronson KD Schwartz JS Chen TM Wong KL Goin JE Mancini DM . Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. (1997) 95(12):2660–7. 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2660

16.

Koratala A Verbrugge F Kazory A . Hepato-cardio-renal syndrome. Adv Kidney Dis Health. (2024) 31(2):127–32. 10.1053/j.akdh.2023.07.002

17.

Fuhrmann V Jäger B Zubkova A Drolz A . Hypoxic hepatitis—epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical management. Wien Klin Wochenschr. (2010) 122:129–39. 10.1007/s00508-010-1357-6

18.

Denis C De Kerguennec C Bernuau J Beauvais F Cohen Solal A . Acute hypoxic hepatitis (‘liver shock’): still a frequently overlooked cardiological diagnosis. Eur J Heart Fail. (2004) 6:561–5. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.12.008

19.

Giallourakis CC Rosenberg PM Friedman LS . The liver in heart failure. Clin Liver Dis. (2002) 6:947–67. 10.1016/S1089-3261(02)00056-9

20.

Giannini EG Testa R Savarino V . Liver enzyme alteration: a guide for clinicians. Can Med Assoc J. (2005) 172:367–79. 10.1503/cmaj.1040752

21.

Cassidy WM Reynolds TB . Serum lactic dehydrogenase in the differential diagnosis of acute hepatocellular injury. J Clin Gastroenterol. (1994) 19:118–21. 10.1097/00004836-199409000-00008

22.

Levitt DG Levitt MD . Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at the roles of synthesis, catabolism, renal and gastrointestinal excretion, and the clinical value of serum albumin measurements. Int J Gen Med. (2016) 9:229–55. 10.2147/IJGM.S102819

23.

Arques S . Serum albumin and cardiovascular disease: state-of-the-art review. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). (2020) 69:192–200. 10.1016/j.ancard.2020.07.012

24.

Horwich TB Kalantar-Zadeh K MacLellan RW Fonarow GC . Albumin levels predict survival in patients with systolic heart failure. Am Heart J. (2008) 155:883–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.043

25.

Prenner SB Pillutla R Yenigalla S Gaddam S Lee J Obeid MJ et al Serum albumin is a marker of myocardial brosis, adverse pulsatile aortic hemodynamics, and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. (2020) 9:e014716. 10.1161/JAHA.119.014716

26.

Manolis AA Manolis TA Melita H Mikhailidis DP Manolis AS . Low serum albumin: a neglected predictor in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur J Intern Med. (2022) 102:24–39. 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.05.004

27.

Xu H Wang H Chen S Chen Q Xu T Xu Z et al Prognostic value of modified model for end-stage liver disease score in patients undergoing isolated tricuspid valve replacement. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:932142. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.932142

Summary

Keywords

association, heart transplantation, MELD-Albumin score, model for end-stage liver disease score, prognosis

Citation

Wei Z, Xiao-bin L, Zhi-yun X, Lin H, Feng Z and Bai-ling L (2026) Prognostic value of preoperative MELD-albumin score in patients undergoing heart transplant. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1675714. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1675714

Received

29 July 2025

Revised

02 November 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Kenichi Hongo, Jikei University School of Medicine, Japan

Reviewed by

Tahir Yagdi, EGE University Department of Cardivascular Surgery, Türkiye

Erman Pektok, Bursa Uludağ University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wei, Xiao-bin, Zhi-yun, Lin, Feng and Bai-ling.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Zhu Feng alexzhujunchi@hotmail.com Li Bai-ling smmu_libailing@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.